Theorising Universal Design for Learning to Create More Inclusive Outdoor Play Spaces: A Preliminary Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context

2.1. Universal Design for Learning

2.2. Outdoor Play

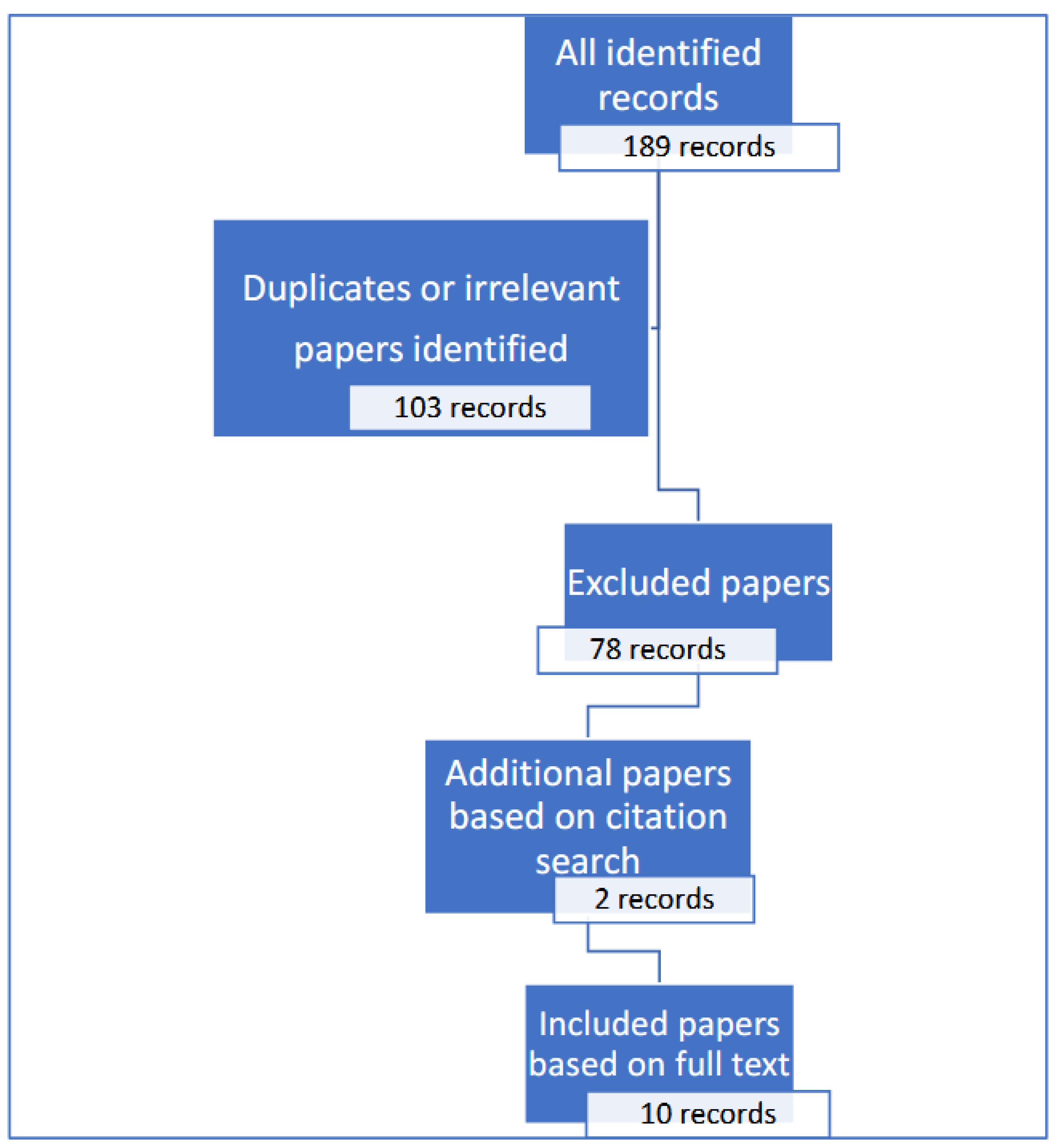

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Findings

5.1. The Importance of Including All Children in Outdoor Play

5.2. The Potential of UDL to Support Inclusion

5.3. The Need for Specific UDL Resources Tailored to Outdoor Play

6. Discussion

7. Limitations of the Study

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamson, G. S., Rouse, E., & Emmett, S. (2021). Recalling childhood: Transformative learning about the value of play through active participation. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 42(4), 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeqdad, Q. I., Alodat, A. M., Alquraan, M. F., Mohaidat, M. A., & Al-Makhzoomy, A. K. (2023). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2218191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, T., & Mitten, D. (2022). Celebrating diversity and inclusion in the outdoors. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. T., Le Courtois, S., & Eberhart, J. (2023). Making space for children’s agency with playful learning. International Journal of Early Years Education, 31(2), 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, P. (2024). Identifying and removing barriers to accessibility in environmental education and outdoor recreation (School of Education and Leadership Student Capstone Projects, 1025). Hamline University School of Education. Available online: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_cp/1025 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Boysen, G. A. (2021). Lessons (not) learned: The troublng similarities between learning styles and universal design for learning. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 10(2), 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M., Han, C. S., Lin, Y., Jacob, J., Munday, F., Zeni, M., Walters, M., & Oberle, E. (2022). Evaluation of the web-based Outside Play-ECE intervention to influence early childhood educators’ attitudes and supportive behaviors toward outdoor play: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(6), e36826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C., Bolbos, A., & Schneider, S. (2019). Do poorer children have poorer playgrounds? A geographically weighted analysis of attractiveness, cleanliness, and safety of playgrounds in affluent and deprived urban neighborhoods. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 16(6), 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capp, M. (2016). Is your planning inclusive? The Universal Design for Learning framework for an Australian context. Australian Educational Leader, 38(4), 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). (2024). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Chen, H., Evans, D., & Luu, B. (2023). Moving towards inclusive education: Secondary school teacher attitudes towards Universal Design for Learning in Australia. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 47(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, L., Standal, O. F., & Moe, V. F. (2018). Norwegian teachers’ safety strategies for Friluftsliv excursions: Implications for inclusive education. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(3), 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalki, T. (2023). Increasing access to outdoor play for families of children with disabilities [Doctoral thesis, St Catherine University]. CORE. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/works/148972548/?t=307ff5f030c4ef78360ad8866682621b-148972548 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Dankiw, K. A., Kumar, S., Baldock, K. L., & Tsiros, M. D. (2024). Do children play differently in nature play compared to manufactured play spaces? A quantitative descriptive study. International Journal of Early Childhood, 56(3), 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danniels, E., & Pyle, A. (2023). Teacher perspectives and approaches toward promoting inclusion in play-based learning for children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 21(3), 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chavez, A. C., Seims, A. L., Dickerson, J., Dharni, N., & McEachan, R. R. (2024). Unlocking the forest: An ethnographic evaluation of Forest Schools on developmental outcomes for 3-year-olds unaccustomed to woodland spaces. Welcome Open Research, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2003). Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eager, D., Gray, T., Little, H., Robbe, F., & Sharwood, L. (2025). Risky play isn’t a dirty word: A tool to measure benefit-risk in outdoor playgrounds and educational settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsherif, M. M., Middleton, S. L., Phan, J. M., Azevedo, F., Iley, B., Grose-Hodge, M., Tyler, S. L., Kapp, S. K., Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A., Grafton-Clarke, D., Yeung, S. K., Shaw, J. J., Hartmann, H., & Dokovova, M. (2025). Bridging neurodiversity and open scholarship: How shared values can guide best practices for research integrity, social justice, and principled education. [Unpublished manuscript]. [CrossRef]

- Frances, L., Quinn, F., Elliott, S., & Bird, J. (2024). Outdoor learning across the early years in Australia: Inconsistencies, challenges, and recommendations. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(5), 2141–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S., Gibson, J., Jones, C., & Hughes, C. (2022). “A new adventure”: A case study of autistic children at Forest School. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 24(2), 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronzek, M. (2023). “It was like that they were more equal outside.” Teachers’ perception of experiences, benefits and challenges of inclusive outdoor education [Master’s thesis, Linköping University]. DiVA portal. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1787111&dswid=-640 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Gray, P. (2017). What exactly is play, and why is it such a powerful vehicle for learning? Topics in Language Disorders, 37(3), 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P. (2020). Risky play: Why children love and need it. In J. Loebach, S. Little, A. Cox, & P. Eubanks Owens (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of designing public spaces for young people (pp. 39–51). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, T. (2018). Outdoor learning: Not new, just newly important. Curriculum Perspectives, 38(2), 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T., Dallat, C., & Jackson, P. (2025a). Pendulum swings: Developing a healthy risk appetite for outdoor play, adventurous learning, and child brain development. In T. Gray, M. Sturges, & J. Barnes (Eds.), Risk and outdoor play: Listening and responding to international voices: Part 1 (pp. 37–56). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T., Sturges, M., & Barnes, J. (Eds.). (2025b). Outdoor risky play: A wildly successful and growing movement across the globe. In Risk and outdoor play: Listening and responding to international voices: Part 1 (pp. 1–19). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, T., Sturges, M., & Barnes, J. (Eds.). (2025c). Risk and outdoor play: Listening and responding to international voices: Part 1. Springer Nature. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/9789819654543 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Grenier, M., Fitch, N., & Young, J. C. (2018). Using the climbing wall to promote full access through Universal Design. Palaestra, 32(4), 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, M., Miller, N., & Black, K. (2017). Applying Universal Design for Learning and the inclusion of spectrum for students with severe disabilities in general physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(6), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte, H. A. (2013). Universal design and outdoor learning. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 41(3), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, K. (2019). Bringing the benefits of nature to all children. The Active Learner, Highscope’s Journal for Early Educators, Spring, 12–13. Available online: https://highscope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HSActiveLearner_2019Spring_sample.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Hopper, R. (2017). Special educational needs and disability and learning outside the classroom. In S. Waite (Ed.), Children learning outside the classroom from birth to eleven (2nd ed., pp. 118–130). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J. (2015). Implementing the three block model of Universal Design for Learning: Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy, stress, and job satisfaction in inclusive classrooms K-12. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O., Buckley, K., Lieberman, L. J., & Arndt, K. (2022). Universal Design for Learning—A framework for inclusion in outdoor learning. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 25(1), 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O., Whelan, J., & Coulter, M. (2025). A pedagogy of outdoor learning in the primary school—Insights from outdoor educators in Ireland (pp. 1–19). Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomsi, K., Bouzghiba, H., Mendyl, A., Al-Delaimy, A. K., Dahri, A., Saad-Hussein, A., Balaw, G., El Marouani, I., Sekmoudi, I., Adarbaz, M., Khanjani, N., & Abbas, N. (2024). Bridging research policy gaps: An integrated approach. Environmental Epidemiology, 8(1), e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Sears, M. E., Stefanidis, A., Evmenova, A. S., Rao, K., Mergen, R. L., Owen, L. S., & Strimel, M. (2023). Achievement of learners receiving UDL instruction: A meta-analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 122, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L. J. (2017). The need for Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(3), 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L. J., & Grenier, M. (2019). Infusing Universal Design for Learning into physical education professional preparation programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 90(6), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L. J., Grenier, M., Brian, A., & Arndt, K. (2020). Universal Design for Learning in physical education. Human Kinetics, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H., & Stapleton, M. (2023). Exploring toddlers’ rituals of “belonging” through risky play in the outdoor environment. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 24(3), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H., & Wyver, S. (2008). Outdoor play: Does avoiding the risks reduce the benefits? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 33(2), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A. (2018). Outdoor learning in primary schools: Predominately female ground. In T. Gray, & D. Mitten (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of women and outdoor learning (pp. 637–648). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J., Sanches, M., Jaffe, J., & Elton-Marshall, T. (2021). Paving the way for outdoor play: Examining socio-environmental barriers to community-based outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, T. A. (2024). Universal Design as a framework to increase diversity, inclusion, equity and belonging in Canadian outdoor learning. In S. Priest, S. Ritchie, & D. Scott (Eds.), Outdoor learning in Canada. Laurentian University. Available online: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/olic/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Lynch, H., Moore, A., & Prellwitz, M. (2018). From policy to play provision: Universal Design and the challenges of inclusive play. Children, Youth and Environments, 28(2), 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, F., Boldemann, C., Söderström, M., Blennow, M., Englund, J. E., & Grahn, P. (2009). Outdoor environmental assessment of attention promoting settings for preschool children. Health & Place, 15(4), 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarrigle, L., Beamish, W., & Hay, S. (2023). Measuring teacher efficacy to build capacity for implementing inclusive practices in an Australian primary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(7), 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerts-Brandsma, L., Sibthorp, J., & Rochelle, S. (2020). Using transformative learning theory to understand outdoor adventure education. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(4), 81–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D. M. (2025). Research opportunities to contribute to increased justice using a transformative approach. Methods in Psychology, 12, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A., Boyle, B., & Lynch, H. (2023). Designing for inclusion in public playgrounds: A scoping review of definitions, and utilization of universal design. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 18(8), 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. C. (2023). “Sowing the seed”: A bio-ecological exploratory case study of the forest school approach to learning and teaching in the Irish primary school curriculum [Doctoral thesis, Mary Immaculate College]. MIRR—Mary Immaculate Research Repository. Available online: https://www.dspace.mic.ul.ie/handle/10395/3124 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Pikus, A. E., Etchison, H. M., Gerde, H. K., & Bingham, G. E. (2024). Nature for all: Utilizing the Universal Design framework to incorporate nature-based learning within an early childhood inclusive classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children, 57(5), 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, J., van der Wilt, F., van Santen, S., van der Veen, C., & Hovinga, D. (2022). The importance of play in natural environments for children’s language development: An explorative study in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Years Education, 31(2), 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A. (2023). Australian families—How we play. RCH Child National Health Poll (Poll report, Poll 28). Available online: https://rchpoll.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/NCHP28-Poll-report-A4_FA.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Roski, M., Walkowiak, M., & Nehring, A. (2021). Universal Design for Learning: The more, the better? Education Sciences, 11(4), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffino, A. G., Mistrett, S. G., Tomita, M., & Hajare, P. (2006). The universal design for play tool: Establishing validity and reliability. Journal of Special Education Technology, 21(4), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, L., & Squillaci, M. (2023). Effects of a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) training course on the development of teachers’ competences: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 13(5), 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlberg, P., & Doyle, W. (2019). Let the children play. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A., Kazmi, A. B., & Javed, M. A. F. (2024). From research to reality: Implementing transformative learning in inclusive education. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 5(4), 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracho, O. N. (2023). Theories of child development and their impact on early childhood education and care. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(1), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, A., Kennett, A., & Pugh, V. (2022). Universal Design for Learning as a theory of inclusive practice for use by educational psychologists. Educational Psychology in Practice, 38(4), 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, M., Boldemann, C., Sahlin, U., Mårtensson, F., Raustorp, A., & Blennow, M. (2013). The quality of the outdoor environment influences children’s health: A cross-sectional study of preschools. Acta Paediatrica, 102(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, M. (in press). “You can see lots of good things in the climbing tree”: Listening to children’s views of their outdoor space. In T. Gray, M. Sturges, & J. Barnes (Eds.), Risk and outdoor play: Listening and responding to collective voices part 2. Springer Nature.

- Sturges, M., Gray, T., Barnes, J., & Lloyd, A. (2023). Parents and caregivers’ perspectives on the benefits of a high-risk outdoor play space. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 26(3), 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunton, S. A., Brian, A., & True, L. (2017). Universally designed motor skill intervention for children with and without disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29(6), 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. (2009). How to do your research project. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Trapasso, E., Knowles, Z., Boddy, L., Newson, L., Sayers, J., & Austin, C. (2018). Exploring gender differences within forest schools as a physical activity intervention. Children, 5(10), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (1989). Conventions on the rights of the child. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- United Nations. (2021). Goal 4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- van Engelen, L., Ebbers, M., Boonzaaijer, M., Bolster, E. A. M., van der Put, E. A. H., & Bloemen, M. A. T. (2021). Barriers, facilitators and solutions for active inclusive play for children with a physical disability in the Netherlands: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatrics, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S., Husain, F., Scandone, B., Forsyth, E., & Piggott, H. (2023). “It’s not for people like (them)”: Structural and cultural barriers to children and young people engaging with nature outside schooling. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 23(1), 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. (2013). Playing and learning outdoors: Making provision for high quality experiences in the outdoor environment with children 3–7. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., Subban, P., & Hitches, E. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: Rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., McNeely, E., Cedeno-Laurent, J., Pan, W., Adamkiewicz, G., Dominici, F., & Spengler, J. (2014). Linking student performance in Massachusetts elementary schools with the “greenness” of school surroundings using remote sensing. PLoS ONE, 9(10), 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Carter, R. A., Jr., Greene, J. A., & Bernacki, M. (2024). Unraveling challenges with the implementation of Universal Design for Learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 36(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Key words were included | No key words |

| Written in English | Not written in English |

| Published after 2010 | Published prior to 2010 |

| Explored outdoor play and UDL | Focused on playground design or indoor play |

| Grey literature |

| Year | Author | Type of Literature | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | Bonnin | Thesis | Survey |

| 2023 | Dalki | Thesis | Survey |

| 2023 | Danniels & Pyle | Research | Interviews |

| 2023 | Fronzek | Thesis | Interviews |

| 2013 | Harte | Discussion paper | Research-to-practice information |

| 2019 | Haugen | Discussion paper | Research-to-practice information |

| 2022 | Kelly et al. | Review paper | Review |

| 2023 | Murphy | Thesis | Review |

| 2024 | Pikus et al. | Discussion paper | Research-to-practice information |

| Design Options | Multiple Means of Engagement | Multiple Means of Representation | Multiple Means of Action and Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Welcoming interests and identities: Natural environments provide a variety of ways to engage through the senses, and educators can offer choices in materials and experiences. Example: water-based and leaf-based pouring activities | Perception: Natural environments provide information in a number of ways. Example: pointing out the way the skies show the weather or the trees show the seasons | Interaction: Natural environments can allow for a variation in responses to sensory experiences. Example: honouring different perceptions of the temperature, textures, and colours in natural settings |

| Support | Sustaining effort and persistence: Ensuring physical access to different areas and experiences, as well as appropriate risk, increases the sense of challenge. Example: bush paths that are flat for those using mobility equipment but include side-by-side logs for those ready for balancing | Language and symbols: Using a range of languages to increase understanding. Example: using home languages and Indigenous languages where appropriate in songs and stories | Expression and communication: Natural environments can encourage responses by provoking wonder and joy. Example: providing alternative ways for children to react to beautiful flowers through pointing, verbalising, or using visual supports |

| Executive Function | Emotional capacity: Offering activities that are a mix of individual, side-by-side, and group challenges. Example: a choice of using manual drills on a large log or individual branches | Building knowledge: Traditional and modern knowledge about the landscape can be shared through stories, art, and song. Example: singing traditional songs about birds and animals | Strategy development: Meaningful goals added to activities in natural environments. Example: any form of communicative intent may be a goal, whether it be glances or words |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sturges, M.; Gray, T.; Galbraith, C. Theorising Universal Design for Learning to Create More Inclusive Outdoor Play Spaces: A Preliminary Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121623

Sturges M, Gray T, Galbraith C. Theorising Universal Design for Learning to Create More Inclusive Outdoor Play Spaces: A Preliminary Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121623

Chicago/Turabian StyleSturges, Marion, Tonia Gray, and Carolyn Galbraith. 2025. "Theorising Universal Design for Learning to Create More Inclusive Outdoor Play Spaces: A Preliminary Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121623

APA StyleSturges, M., Gray, T., & Galbraith, C. (2025). Theorising Universal Design for Learning to Create More Inclusive Outdoor Play Spaces: A Preliminary Review. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121623