Abstract

This paper emphasizes the importance of introducing sustainable design principles to primary school children and explores educational methods that foster awareness of the built environment. Through a literature review and three case studies, the research compares different pedagogical approaches used to engage children in sustainability-focused design activities. The case studies examine methods such as STEAM-based analytical problem-solving, storytelling for conceptual understanding, and artistic installations for experiential learning. Findings highlight that tailored pedagogical strategies enhance children’s engagement, while involving university students as facilitators creates reciprocal learning benefits. The study also underscores the role of community engagement by linking local sustainability challenges to classroom learning, thereby encouraging students to apply concepts to real-world issues. Additionally, it suggests that incorporating digital and hybrid models can increase the scalability and accessibility of such programs. Overall, this research identifies best practices, strengths, and weaknesses of various approaches and proposes guiding principles for effective sustainable design education. The outcomes demonstrate the potential of university-led initiatives and collaborative frameworks to build impactful, adaptable educational models. By integrating sustainability into early education, schools and policymakers can foster environmentally conscious citizens equipped to address future challenges.

1. Introduction

Sustainable design education has gained momentum in recent years as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the () emphasize the role of education as a key enabler of all the other SDGs. () focuses on equipping learners with essential knowledge, skills, and values necessary for shaping a sustainable future. It encompasses a broad range of topics, including environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic viability. Empowering educators with the necessary knowledge, skills, and values, promoting youth participation and community-wide action are all considered priority action areas for ESD ().

In this context, the current research compares three methodological approaches for engaging children in the design of their environment through sustainable design principles. Its purpose is to examine how university-led initiatives can effectively introduce these principles to primary school students using diverse pedagogical models. By analyzing three case studies—STEAM-based learning, storytelling, and artistic installations—the study identifies best practices, highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, and proposes a set of guiding principles for educators. These guidelines aim to support teachers in fostering a holistic understanding of sustainable design and cultivating the mindset necessary for meaningful change. In the following sections, key methodologies for teaching sustainable design to children through student-led initiatives and participatory learning are reviewed. Three university-led workshops—collectively titled “Children Designing Sustainable Public Spaces and Neighborhoods”, organized by the University of West Attica (Uni.W.A.), are presented. These initiatives engage primary school children in learning sustainable design principles while promoting community participation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a holistic understanding of sustainable practices across different educational levels.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Design Education

According to the pertinent literature, high-quality sustainability education initiatives require both direct experiences in nature, as well as structured learning that addresses environmental issues, resource management, and social responsibility (; ). Educating children about sustainability in the context of the built environment is key to developing environmentally conscious individuals who can contribute to a more sustainable future (; ; ; ). To this end, educators can use a variety of strategies tailored to young learners, but it is important to understand that sustainability requires a holistic approach and a systems thinking perspective for teaching to be effective ().

The () identifies 12 interlinked competences necessary for sustainable development that are grouped under four areas: ‘embodying sustainability values’, ‘embracing complexity in sustainability’, ‘envisioning sustainable futures’ and ‘acting for sustainability’. () identified, respectively, five key competences necessary for new curricula: systems thinking, futures thinking, action-oriented, values thinking and collaboration competence. In a systematic review of sustainability competences in primary school education, () propose that collaboration between children and adults is at the heart of primary school students’ learning of sustainability competencies, as children’s interactions are more effective when supported by adults. While systems thinking and collaboration are well established, they are less transformative than other competencies. Researchers emphasize empowering children to develop futures thinking through art-based, interdisciplinary approaches that merge the arts and sciences. Such creative, student-led methods—like drawing or drama—encourage imagination, reflection, and transformative learning ().

Action competence is actually emphasized by many different scholars for all levels of education (; ; ), while action-oriented pedagogy is underlined as a key approach for climate change education in the recent report of (). Problem-based, experiential, and project-based learning that connects students with fieldwork in the community for issues that are personally relevant to them are among the methods found to be most effective.

Design Thinking is an instructional model that can fruitfully support problem-based learning for transformative sustainability education (). Originating from the industry, it is widely used in education, usually connected with STEAM projects (; ). Design Thinking encourages a more in-depth examination of the problem, facilitating a broader understanding from multiple perspectives. Consequently, this approach enables the creation of solutions that address all pertinent aspects of the problem and are appropriate for any given context, client, or user. In (), the authors identify seven common educational models that progress from exploration and idea generation to testing and refinement. These frameworks have been effectively applied in sustainable co-design projects with children. () and () argue that they lead to greater “environmental awareness and action as well as heightening their appreciation and perception of architecture and the built environment” (), as the focus is not only on the outcome but also on the process. () have identified three different formats for such projects, that differ in terms of goals, duration, activities, and tools used: Design Jams, Workshops, and School Programs, with the latter being the lengthiest and offering a holistic approach to existing didactic programs, eventually contributing to a whole-school approach (; ).

As mentioned earlier, community involvement is considered an effective way to reinforce sustainability education and can be combined with design-based disciplines like architecture, promoting ownership of authentic projects (; ). Engaging children in community environmental initiatives, such as neighborhood clean-ups or tree planting, fosters their understanding that collective action can positively influence the built environment (). By showing how these activities contribute to a healthier planet, educators and parents can inspire children to become active citizens in building a more sustainable world and practicing environmental stewardship. Student engagement through clubs, projects, and campaigns promotes active participation in sustainability initiatives, reinforcing the importance of individual contributions across all age groups ().

2.2. Children’s Participation

There are numerous models that outline how to interact with children in a respectful and democratic way. () was the first to identify that children’s participation is not always genuine and that there are eight rungs ranging from manipulation to child-initiated projects and shared decisions with adults. The Lundy Model explicitly lays out four requirements that must be met in order to enable participation in accordance with Article 12 of the (). The four key elements of creating a safe and inclusive “space”, supporting children’s “voice”, providing an “audience”, and giving them the opportunity to “influence” and have their views acted upon are essential for children’s participation in decision-making to be effective, meaningful, and in line with their rights. The process itself will be compromised and the result will be affected if any of the components are omitted.

() underscore that effective and meaningful child participation in decision-making relies on four key elements: a safe and inclusive space, support for children’s voices, a receptive audience, and genuine opportunities to influence outcomes. Omitting any of these components weakens both the process and its results.

() expand on this strategy and propose a new pedagogical model that involves primary school children and architecture students as “design partners”, with the university students acting as recorders and enablers of children’s creativity through a range of design activities such as storytelling, discussion, sketching, and model making. () also stress the importance of planning with children in a proactive way, with adults facilitating children and sharing a strong vision of how children’s ideas and work can produce substantive changes to the built environment. However, the study by () focuses on the factors influencing enhanced student active participation in activities both at school and the local community, highlighting the underlying perceptions of both students and teachers, some of the features of the learning processes, and how the current school culture determines the outcome.

2.3. University Design Students Partnering with Primary School Students

University students can play a pivotal role in advancing primary school pupils’ understanding of sustainable design principles through mentorship and knowledge exchange. Such collaborations promote sustainability awareness while fostering creativity, design thinking, and critical problem-solving skills related to environmental challenges (; ). They also encourage teamwork and collaborative learning for both primary and university students, thus fostering a new generation of environmentally conscious thinkers and innovators.

Engaging with children enhances university students’ leadership, communication, and teaching skills, deepens their commitment to sustainability, and strengthens empathy and interpersonal competence. Interpersonal competency is actually emphasized by the () reference framework on competencies for sustainability programs at universities and colleges around the world. It is perceived as a key competency that helps students “to apply the concepts and methods of each competency not merely as ‘technical skills,’ but in ways that truly engage and motivate diverse stakeholders and to empathically work with collaborators’ and citizens’ different ways of knowing and communication”.

The Islands Diversity for Science Education—IDiverSE—was an educational project, co-funded by the Erasmus+ Agency of the European Union from 2017 to 2020. In this project, the Design Thinking approach was introduced to students as a new methodology. The approach was employed as a potent instrument to advance an open school philosophy, wherein the students’ learning experience was directly correlated with the issues prevalent in their community (; ). The students were required to follow a series of four steps through which they were able to establish connections between the knowledge they had acquired at school and their everyday context. This ultimately led them to the creation of a community development strategy, the aim of which was to increase awareness and mitigate problems. Design Thinking guided students through an iterative process of understanding, imagining, creating, and sharing solutions to sustainability challenges. Through this approach, university students engaged primary school learners in sustainability concepts and design thinking practices, fostering creativity and collaborative problem-solving across multiple educational settings (; ).

The school environment is a very important place for students as they spend most of their time there. Therefore, the participation of students in the design of the school and its yard has been a topic of discussion and activities several times ().

Through cooperative learning in small groups of students, children sharpen their ability to solve problems and respect the thinking of others, but also to communicate their own thinking (). Collaboration, knowledge sharing, and co-construction of ideas enhance the learning process and contribute to the final proposal. In addition, students can contribute differently to the group by assigning roles in cooperative learning and promoting positive interdependence among group members.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Outline

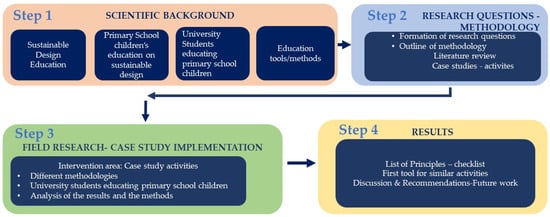

Considering the relevant literature, the primary objective of this paper is to underscore the significance of introducing sustainable design principles to children early on as well as to present a general methodological framework for further application. The paper explores diverse educational methods and tools that can effectively engage children in comprehending the built environment and its various aspects of sustainable design. To be more specific, the study examines three different methodological approaches aimed at involving primary school children in designing their environment using sustainable design principles. The comparison among these approaches forms a comprehensive set of guiding principles that incorporates the essential aspects of the subject, serving as a valuable resource for educators in their instructional practices. The methodology is outlined in Figure 1. Step 1 includes the scientific background in the following fields: sustainable design education, primary school children’s education on sustainable design, university students educating primary school students, and identification of educational tools and methods. Step 2 focuses on the identification of the research question and formation of the methodology. Step 3 includes the fieldwork, mainly the three workshops that took place, each with different methodological tools. Finally, Step 4 includes the results and discussion regarding the research questions identified.

Figure 1.

Methodological outline.

The research questions can be specifically summarized as follows:

- RQ1: How can university-led initiatives effectively introduce sustainable design principles to primary school students?

- RQ2: What are the strengths and weaknesses of different educational methodologies (STEAM, storytelling and crafts, artistic installations) in teaching sustainable design?

- RQ3: How does participation in sustainable design activities impact children’s understanding of environmental responsibility and urban planning?

- RQ4: What role do university students play in facilitating sustainability education, and what are the mutual learning benefits?

Despite growing awareness of the importance of sustainability in education, there remains a noticeable gap in well-structured methodologies designed to effectively engage primary school children in sustainable design. Ensuring that young learners develop an early understanding of sustainability concepts is crucial for fostering long-term environmental responsibility. From this point of view, this study seeks to address this gap by examining university-led initiatives that introduce sustainable design principles to children. By analyzing various approaches, the research aims to identify effective strategies that can enhance children’s learning experiences and encourage their active participation in sustainability-focused activities.

3.2. Case Studies

3.2.1. Case Study 1: STEM Education Methodology: Designing the Schoolyard of Our Dreams Activity” (Case Study in Piraeus)

The first method followed the STEAM and Design Thinking education methodology, and the subject matter focused on ‘Designing the schoolyard of our dreams’ at the 9th School of Piraeus. The following steps were introduced during the process: think, propose, design, construct, and present (Figure 1). This interdisciplinary approach keeps students engaged and motivated, showing the real-world relevance of their studies (). It helps them develop a broad set of skills essential for addressing sustainability challenges, fostering a generation of problem-solvers and innovators. In the context of the research project ProGIreg and its collaboration with Politecnico di Milano, the course of Sustainable Urban Design of the MSc in Interior Architecture: Sustainable and Social Design, of the Department of Interior Architecture of the University of West Attica (Uni.W.A.), on Friday 20 May 2022, organized in collaboration with the 9th Primary School of Piraeus the action “Participatory Design—Architecture for Children”.

The students were in the 5th grade of the 9th Primary School of Piraeus and were separated into groups of five or six. Each of the groups was assisted by one university student, and overall, the course professor and director managed the whole scheme. The workshop took place in the schoolyard of the school (Figure 2), where desks were arranged in order for each group to sit around and work together, and the duration was one morning.

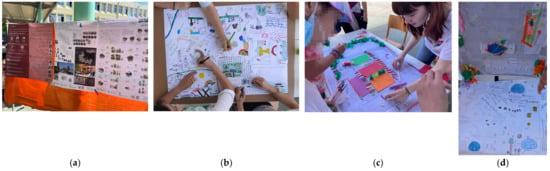

Figure 2.

The methodological framework of case study 1. Step 1: Think and Propose (a), Step 2: Design (b), Step 3: Construct (c), Step 4: Present—evaluate (d).

Step 1: Think and Propose

Educational material posters with a similar theme, that is, sustainable design strategies in outdoor spaces, were presented to the primary students in the schoolyard in order for them to obtain ideas during the brainstorming. The first two steps included thinking and proposing and were implemented on a white piece of paper where all the students could freely express their ideas with markers and colors.

Step 2: Design

After the group agreed on one of the ideas as being the most appropriate for the design of their schoolyard on another paper, which had the plan of the schoolyard printed, they drew their design using different materials available. The groups proposed different solutions based on a central idea that they agreed upon.

Step 3: Construct

The final design was a 3D model constructed with simple materials. The model making was assisted by the student, who was responsible for the group.

Step 4: Present

The final step was the presentation of their design and the documentation of the different aspects that were included in it. The presentation was a significant step since it allowed the students to understand more deeply what they had created and express it using terms and concepts that were taught during the process.

The different requirements of the project steps help students to develop their individual skills, which they may not usually test during the lesson, such as creating a three-dimensional model of a thought or not being given enough space and time to develop their ideas orally or by sketching. This way, in each group, all students can participate in each step according to their own ability ().

The university students that participated were K.T. (MA student), K.B. (MA student), A.K. (BA student), M.Z. (BA student), L.Z. (BA student), K.K. (BA student), K.L. (BA student), and the ERASMUS student T.M. (MA student), and the activity was organized and supervised by Prof. Dr Maro Sinou (co-author), Professor, School of Interior Design, University of West Attica. After the workshop a newsletter poster was created and disseminated (Figure 3). The workshop was supervised by the principal of the school.

Figure 3.

Newsletter from the workshop.

Children engaged in the design and construction of their surroundings, including educational institutions, experience a heightened sense of empowerment. This active participation facilitates their understanding of sustainability principles and cultivates a profound sense of ownership regarding their environments.

3.2.2. Case Study 2: Storytelling and Crafts Methodology. Greening the City by Planting the Buildings in Our Neighborhood—Green Infrastructure

The second initiative, entitled “Greening the City by Integrating Plants into Neighborhood Buildings,” was executed as part of the proceedings of the Two-Day Conference on Sustainable Architectural and Spatial Planning, held in Athens in June 2023. This conference was organized by the Director of the postgraduate program in “Sustainable Design of Architectural Space” within the Department of Interior Architecture at the University of West Attica. The workshop was designed to be suitable for children aged 6 to 8 years old. The group of educators comprised a faculty member of the department of Interior Architecture (PhD Architect), a young architect with post-graduate studies in sustainable design (PhD candidate), and two undergraduate interior architecture students with a background in performing and fine arts (MA Fine Arts, MA in Performing Arts). The University students that participated were K.T. (co-author) (MA student), LT. (BA student), K.V. (BA student) and the activity was organized and supervised by Dr. Evgenia Tousi (co-author), Adjunct Lecturer, School of Interior Design, University of West Attica.

The initiative aimed to increase awareness regarding the potential transformations of ordinary urban buildings to enhance the microclimate and overall aesthetic of the city. By engaging primary school students in this process, the initiative sought not only to educate them about the environmental impact of urban architecture but also to inspire a sense of stewardship for their surroundings. Through hands-on activities and discussions, participants were encouraged to explore innovative strategies for improving urban spaces, ultimately fostering a deeper understanding of the importance of sustainable design practices and their role in creating a more environmentally conscious community.

The workshop utilized storytelling and 2D craft creation to deliver well-designed and engaging content. Craft modeling in sustainability education offers substantial benefits. In general, it keeps students motivated and cultivates practical skills like problem-solving and critical thinking (). Hands-on projects provide a deep understanding of sustainability, being associated with various environmental and socio-cultural issues. Ultimately, craft modeling transforms sustainability education into an interactive experience, empowering students to actively contribute to a sustainable future. Combined with storytelling, it enables educators to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable, improving comprehension and retention ().

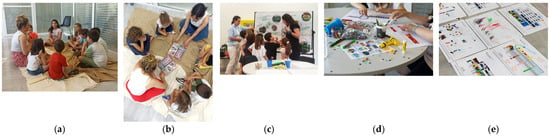

The methodological framework of this workshop included six stages. The analysis of each stage is provided below (Figure 4).

- Step 1: Introduction and team-building activities: Introduction and team-building activities, followed by a brief discussion about our city’s strengths and weaknesses. Particular attention was placed on the city’s scarcity of green spaces. At that stage, a seamless transition was made into the interactive storytelling session.

- Step 2: Storytelling session: For the purposes of the interactive storytelling session, educators have chosen the “Balcony,” a wordless picture book by (). The book exemplifies the power of visual storytelling. Through intricate illustrations, the narrative follows a young girl who transforms a barren balcony into a vibrant garden. The book effectively employs color, texture, and composition to convey themes of adaptation, connection to nature, and personal growth without text. This silent format invites readers to actively interpret the imagery, fostering deeper engagement with the story and encouraging multiple interpretations.

- Step 3: In-depth Exploration: How can urban greenery be integrated into building structures? This investigation utilizes explanatory posters measuring 70 × 100 cm to illustrate various strategies and design concepts for incorporating green elements, such as vertical gardens, green roofs, and plant walls, into urban architecture. The aim is to highlight the ecological, aesthetic, and social benefits of integrating greenery into the urban landscape, thereby enhancing biodiversity, improving air quality, and fostering community engagement.

- Step 4: Creative Construction: This concept encompasses the innovative design and building of structures that merge artistic expression with functionality. It involves utilizing diverse materials and techniques to create unique, practical solutions to architectural challenges, while also promoting sustainability and ecological principles in the design process.

- Step 5: Photographic Documentation and Evaluation of the Activity: Photographic documentation of the creative constructions is conducted to visually capture the outcomes of the project. This process aims to showcase the various designs and techniques employed by participants, providing a visual record that can be used for analysis and presentation. Following the documentation, a comprehensive evaluation of the activity took place. This evaluation assessed the effectiveness of the creative process, the participant engagement, and the overall impact of the constructions on the intended objectives. The goal is to gain insights into the successes and challenges encountered during the project, which will contribute to future improvements and developments.

Figure 4.

Methodology outline of case study 2. Step 1: Introduction and Team-Building Activities (a), Step 2: Sto-ry-telling Session (b), Step 3: In-depth Exploration (c), Step 4: Creative Construction (d), Step 5: Photographic Documenta-tion and Evaluation of the Activity (e).

3.2.3. Case Study 3: Artistic Inspiration for an Installation. “Where to Find Energy and How to Use It” Urban Art Installation with Reused Materials

The theme of the third action is ‘Where to find energy and how to use it’, focusing on the scale of the building and the contribution of renewable energy sources to the ecological footprint of cities. In this educational cycle, children learned basic concepts about renewable energy sources and their integration into the city and the building through appropriate activities and creative construction. By incorporating concepts of energy conservation into the curriculum, students develop an awareness of the importance of efficient energy use and learn practical strategies to reduce consumption, which contributes to a more sustainable future (). With an effort to combine art and sustainability, this workshop is targeted at raising awareness on sustainable practices (). The action is intended to promote sustainable management of the urban landscape with the contribution of artists and architects, and to develop proposals for the city and neighborhoods with the participation of the community and children.

During the activity organized at the Serafion Cultural and Sports Center of the Municipality of Athens in June 2023, the children who participated had the chance to experience what it is like to be an active, rather than merely passive, citizen of our city. For kids ages 8 to 12, the workshop provided a special setting for teamwork and artistic expression. The participants used a range of materials and investigated the value of reuse by creating a “clothing” for the public area. This process not only promoted collaboration between the children, but also inspired them to think about how they can transform waste into artistic and functional objects. This experience strengthened the children’s awareness of sustainability and the value of creative recycling. The university students that participated are N.K. (MA student), V.P. (BA student), and E.F. (BA student), and the activity was designed and supervised by Prof. Dr Nikos Kourniatis, Associate Professor, School of Civil Engineering, University of West Attica.

The action consisted of four distinct steps:

- Step 1: Team-building activities and inspiration on the first day of the workshop; the children participated in a number of activities designed to help them get to know each other and introduce them to the project’s fundamental ideas. Children were given the chance to introduce themselves and discuss their opinions on public space and the value of community during the first meeting. The conversation then turned to the city’s contemporary rhythms, which frequently cause estrangement. Participants were urged to consider ways to design gathering places that would foster conversation and engagement. In addition, the work of an artist was selected as inspiration.

- Step 2: Discuss and design the clothing for the city

- Step 3: Construct an installation created by the children

- Step 4: Present and evaluate a presentation of the installation and evaluation of its broader impact

During the 1st day, the work of artist Cristal Wagner was discussed; through her artistic creations that adorn buildings, she disrupts the urban fabric and provides fresh insights into how people interact with their surroundings. The materials that would be utilized to create the “clothing” of the public area were shown at the end of the day, along with an overview of the mesh that would serve as the creation’s canvas and how it would be woven and arranged. Children were ready to put their ideas into action on the second day thanks to this procedure.

A number of activities centered on the development and application of the concepts created the day before were part of the workshop’s second day’s activities. Initially, a new set of kids assembled at the location that the prior group had established. They began by talking about energy sources, primarily the sun and water, and how people may use the environment to generate energy. The children were inspired to consider the value of sustainability and material reuse by this conversation. The artwork of artist Olafur Eliasson, who incorporates energy and natural elements into his pieces, was then shown. The kids were inspired by this presentation as they spoke about how artists employ materials symbolically. The kids were then asked to incorporate references to energy collection, storage, and distribution into their imaginative building materials. After reviewing the previous day, the kids used sponges, colored gels, and threads to change the public space’s “clothing” and give it practical meaning beyond its aesthetic and environmental relevance. Taking into consideration the larger outside movement space, the grid/canvas was placed in a specific spot within the Serafion Cultural and Sports Center to finish the process. By arranging the vibrant materials on the grid, the kids created the “clothing” of the space, which served as a barrier for guests to congregate and interact. The children’s discussion and presentation of the finished creation marked the end of the day, encouraging cooperation and creativity. Children developed the following traits as a result of the activity:

- Being cognizant of their place in the social and ecological totality (ecological consciousness);

- Being eager to engage in society (active citizens);

- To rethink how they interact with common place items (reuse, recycling, and zero waste);

- The application of imagination, creativity, and inventiveness in real-world situations (innovation).

In terms of methodology, both groups tackled the workshop’s topic by first contacting art (becoming familiar with the conceptual background and work of a modern visual artist) and then creating art (Figure 5). With the aid of the image, the teaching team’s use of art in the classroom sought to give children a more direct absorption of information. As a result, while an image in art can and does provide knowledge about human culture as a whole, it also gives each child the chance to create a point of reference, or to visualize the information that is presented to him. Information is absorbed more naturally and in the form of a game through this interaction with the artwork, giving the child greater flexibility to integrate what he already knows and subsequently be able to remember it more readily (). As a result, while learning occurs more independently, it can also occur in a group setting.

Figure 5.

Methodology outline of case study 3. Step 1: Think and Propose—Artist inspiration (a), Step 2: Design the clothing for the city (b), Step 3: Construct (c), Step 4: Pre-sent—evaluate (d).

It is also important to note that the groups participating in the session changed every day. The first day’s participants were aware that they would leave something for the following group, and the second day’s participants were aware that they needed to handle their own proposal based on a pre-existing basis. Even though it was not explicitly explained to the children, this introduced them to the idea of being accountable for what they leave for the next group. On the second day, however, the kids were faced with the challenge of creating something by using what already existed.

Lastly, the most immersive aspect of the program was the group project, or “clothing” for the public space, which was finished in two days and installed in the Serafio surrounding area. The children used the materials (such as the sponge that would absorb moisture and water from the air or the threads that allowed the work to interact with its surroundings) to tell stories about what they saw, heard, and then shared with the teaching team.

The narrative built out of the resources utilized the following:

- Glasses (containers) and sponges are examples of environmental water collection equipment.

- The gathering of solar thermal energy is referred to by the knitted surfaces of bags and gels.

- The threads on the construction represented the movement of energy from the site of collecting to other points, the interaction of the work with its surroundings, and changes in the materials, such as the intense temperature (melting).

- The kids also independently wrote messages about the environment and pinned them to the grid.

The strengths and weaknesses of the above methodologies and practices are summarized in the following table, showing that all three methods have strong advantages and can be utilized in different conditions. Weaknesses identified were mostly related to practical issues (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strengths and weaknesses identified amongst the three methods.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Different Methods

High-quality sustainability education initiatives combine direct experiences in nature, as well as structured learning in the fields of environmentalism, effective resource management, and social Responsibility. Community and children’s workshops serve to enhance awareness of sustainable practices and encourage participation among residents of all ages.

It is evident that university students can play a pivotal role in fostering primary school students’ comprehension of sustainable design tenets. This could be achieved by sharing knowledge, offering guidance and support, and encouraging younger learners. The utilization of cooperative learning in small groups of students facilitates the enhancement of children’s problem-solving capacity, helps them demonstrate respect for the perspectives of others, and helps them communicate their own ideas ().

The process of collaboration, knowledge sharing, and co-construction of ideas serves to enhance the learning process and contribute to the final proposal. Furthermore, students have the option of assigning roles in cooperative learning and promoting positive interdependence among group members, thus allowing for a greater diversity of contributions from each student.

This paper examines a range of educational methods and tools that can effectively engage children in comprehending the built environment and its various aspects of sustainable design. In particular, it considers three different methodological approaches that are designed to involve primary school children in designing their environment using sustainable design principles. The comparison of these approaches provides a comprehensive set of guiding principles that incorporates the essential aspects of the subject, offering valuable insights for educators in their instructional practices.

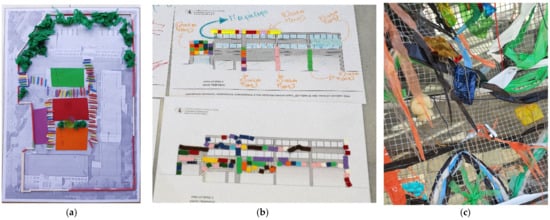

The first method followed the STEAM and Design Thinking education methodology, and the subject matter focused on ‘Designing the schoolyard of our dreams’ at the 9th and 11th Schools of Piraeus. The second action is based on the theme ‘Greening the city by planting the buildings in our neighborhood’. The third action was centered on the exploration of energy sources and their utilization, with a specific emphasis on the role of renewable energy in mitigating the ecological footprint of urban settlements (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The three methods’ case study results: (a) Case Study 1; (b) Case Study 2; (c) Case Study 3.

The table shows (Table 2) different aspects—criteria of the proposed methods that have been introduced and evaluated for all three case studies. The parameters include Introduction tools, Inspiration tool, Representation method, Participants, Expected design results, and General results. The study, based on the analysis of the methods employed and the outcomes of the workshops, indicates that these criteria are the most significant and should be addressed in all cases.

Table 2.

Different aspects—criteria of the proposed methods that have been introduced and evaluated for all three case studies.

4.2. Feedback: Impact from the Educators on Students

The questionnaires and the monitoring process provided valuable qualitative and quantitative insights into the effectiveness of the workshops. Eight educators and university facilitators completed structured questionnaires created in Microsoft Forms, assessing student engagement, comprehension, collaboration, creativity, and overall learning impact. Monitoring was conducted throughout all three case studies by the supervisor and academic advisor of each action, who oversaw implementation, conducted participatory observation during the process, and ensured consistency in data collection. Documentation included direct observation, photographic records, and short debrief discussions after each session.

Responses revealed that over 90% of participants demonstrated sustained interest and active involvement, while educators reported notable improvements in teamwork, spatial awareness, and the ability to connect sustainability concepts to everyday life. Feedback also emphasized the importance of collaboration and the adequacy of creative stimuli in inspiring meaningful solutions. Spontaneous peer cooperation and reflective dialogue among the children were also recorded, indicating genuine understanding rather than rote participation. The qualitative analysis highlighted the workshops’ strengths—engagement, creativity, and applied learning—while also identifying opportunities for improvement, such as extended duration and enhanced peer interaction. The questionnaire focused on key areas including the adequacy of learning stimuli, collaboration among participants, workshop design, and the overall learning environment. The educators were asked if they could suggest other ways to introduce students to the issue of sustainable design and help them understand its benefits in their daily lives. They emphasized the importance of introducing the concept of circularity and that repeated actions on the theme of sustainable design with different stimuli and new deliverables should be introduced in this age group. Initiatives should involve the school community and families, and students would manage and control the project, making it their own. Also, becoming familiar with existing examples and case studies in similar areas, such as other schools and residential settings, provides a smaller scale for a more direct understanding. Students could take on the roles from a story they read and create another short story. Repeated sustainability-themed activities, school-community involvement, and exposure to real-world examples helped reinforce students’ understanding of the concepts.

In terms of the importance of students getting to know each other before the activity, and the level of collaboration among them, they emphasized that collaboration among students was essential for enhancing engagement, with cooperative activities fostering enthusiasm and teamwork. Instructors observed that collaborative storytelling and project-based tasks allowed students to explore creativity while developing interpersonal skills, although additional time for collaboration could strengthen these interactions. In the case study at the schoolyard, classmates formed small groups on their own, knew each other quite well and wanted to work together. This helped encourage the students to feel comfortable communicating their ideas directly without worrying about being accepted. They had to work together to use the available materials, but the good thing was that they were on their own when it came to discussing their ideas. In general, the students exchanged ideas and shared materials, stationery, and other supplies during the activity.

Workshop design also played a crucial role in student participation. Some instructors suggested that dedicated sessions for children alone would better facilitate creative expression and exhibitions of completed work, providing a sense of accomplishment. The physical setting, such as school grounds and activity spaces, further inspired creativity, while diverse media formats enriched the learning experience. Instructors described their roles as dynamic, ranging from direct teaching to mentorship, which helped create a supportive atmosphere for students to explore ideas. Many observed that this approach led to increased creativity, emotional growth, and a deeper appreciation for sustainable design and problem-solving. The initiative’s interactive nature allowed students to see the real-world impact of their ideas.

Another question focused on the subject matter of the process and whether any activities could have been performed at a different time or in a different way to have a greater impact. The instructors thought that more time would be needed for the activity and its presentation; a two-day project could be more efficient and create better results. This would give the children time to absorb the new knowledge and information and then propose their ideas. Otherwise, an additional activity could be added, like a game, to help the children understand the general concepts and strategies and connect them to their daily lives. It would also be helpful if the presentations were made in front of other groups of students to encourage discussion and evaluation of each other’s proposals.

According to the instructors, the children benefited most from the discussions, through which they learned the importance of nature’s elements in our daily lives and in private and public spaces. They also learned about minimal energy consumption through modern technological achievements and circularity, which were explained to them in simple yet scientific terms. The instructors emphasized that the benefit was preparing a scientific presentation, trying to retain the most interesting and important information, and explaining it in the simplest and most understandable way. The participants seemed concerned about the composition and use of materials, as well as the second life they could acquire. The activity initiated creative thinking on issues related to the city, sustainability, and food. After the activity ended, children asked for materials to work on at home and inquired about when a similar activity would take place again.

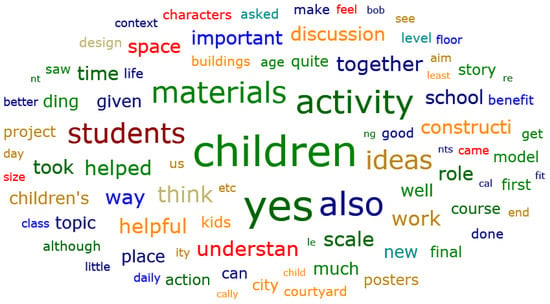

Overall, the feedback confirms that these creative educational initiatives offer significant benefits, fostering engagement, sustainability awareness, and critical thinking. While some adjustments in structure could enhance their effectiveness, the programs’ positive impact is evident in the enthusiasm and creativity of the students. Future improvements could include more student-led exploration and further refinement of workshop designs based on instructor insights (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Concept Cloud, derived from the analysis of instructors’ responses using Atlas.ti software, developed by the authors.

5. Discussion

To provide a clearer understanding of the three methodologies employed, a comparative framework summarizing key aspects of each case study is presented in Table 3. The methodologies—STEAM and Design Thinking, Storytelling and Crafts, and Artistic Installation—were chosen for their demonstrated effectiveness in engaging young learners with sustainability concepts. Each approach offers distinct tools, inspiration sources, representation methods, and expected outcomes. STEAM and Design Thinking emphasize analytical and creative problem solving, storytelling enhances comprehension and imagination, and artistic installations provide immersive, hands-on learning experiences.

Table 3.

Comparative framework of the 3 methodologies.

Qualitative feedback from primary school students, university participants, and educators highlighted the strengths and challenges of each approach. Students expressed enthusiasm for hands-on activities, particularly 3D modeling and urban installation tasks, with many reporting an increased awareness of how sustainability applies to their daily lives. University participants noted improvements in their communication and mentoring skills, emphasizing how teaching sustainability concepts deepened their own understanding. Educators observed higher engagement during activities involving tangible outputs, reinforcing the value of experiential learning. Despite these successes, certain challenges emerged, including varying levels of student engagement, time constraints, and logistical barriers such as material availability. In Case Study 1, some students found 3D modeling challenging without prior experience. Case Study 2 revealed the need for dynamic facilitation to sustain attention during storytelling activities. In Case Study 3, ensuring equitable participation in the final installation required structured team coordination. Acknowledging these challenges allows educators to refine and adapt their approaches for future applications, maximizing the effectiveness of sustainability education initiatives.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that university-led initiatives can successfully introduce sustainable design principles to primary school students through participatory, creative, and community-based learning approaches (RQ1). It establishes a comprehensive pedagogical framework that connects higher and primary education, fostering mutual learning, environmental awareness, and design thinking skills. Each educational method presented distinct advantages (RQ2): the STEAM and Design Thinking approach enhanced analytical reasoning and collaboration; storytelling and crafts nurtured imagination and conceptual understanding; and artistic installations promoted creativity, ecological awareness, and community engagement. The limitations observed were mainly practical—such as time constraints, outdoor conditions, and unfamiliar group dynamics—rather than pedagogical (RQ2). Participation in these activities significantly strengthened children’s sense of environmental responsibility and ownership of public spaces, helping them value reuse, resource efficiency, and their role in shaping sustainable communities (RQ3). Through design making and reflection, children translated abstract sustainability principles into tangible, real-world applications, developing early civic awareness and ecological empathy. At the same time, university students acted as facilitators and co-learners, refining their communication, empathy, and leadership skills while deepening their own understanding of sustainability through teaching practice (RQ4). Findings from post-workshop questionnaires and monitoring confirmed high engagement and understanding among participants. Educators observed enhanced creativity, collaboration, and problem-solving abilities in children, while university mentors gained confidence and pedagogical competence. Overall, the results affirm that experiential, interdisciplinary, and art-based strategies are effective tools for advancing environmental responsibility and sustainable design thinking across educational levels. The key takeaways of this research are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key takeaways from the study.

In conclusion, this research provides a multidisciplinary and participatory educational model that connects theory and practice, empowering learners at all levels to contribute to sustainable community development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and E.T.; methodology, M.S., E.T., N.K. and D.K.; validation, M.S., E.T., N.K., L.M. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., E.T., N.K., Z.K. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, M.S., E.T., N.K., Z.K. L.M. K.T. and D.K.; visualization, L.M. and Z.K.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APCs have been partially funded by the Special Account for Research Grants, University of West Attica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The survey does not contain personal and sensitive personal information, therefore The University Ethics Committee did not request-acquire application for approval for the particular survey.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement has been obtained from all subjects participating in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like acknowledge the University of West Attica for partially covering the APCs for this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the 9th Primary School of Piraeus for the support in the organization of the case study 1 workshop as well as the Serafio Municipality of Athens Building for providing the space for the case study 2 and case study 3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alali, R., & Yousef, W. (2024). Enhancing student motivation and achievement in science classrooms through STEM education. STEM Education, 4, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, S., & Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M. (2021). Investigating possibilities of developing self-directed learning in architecture students using design thinking. Sustainability, 13(8), 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M. G., & Namukasa, I. K. (2022). A pedagogical model for STEAM education. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 16(2), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosevska, J., & Kriewaldt, J. (2019). Fostering a whole-school approach to sustainability: Learning from one school’s journey towards sustainable education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(1), 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M., Stevenson, M., Forbes, A., Falloon, G., & Hatzigianni, M. (2020). Makerspaces pedagogy–supports and constraints during 3D design and 3D printing activities in primary schools. Educational Media International, 57(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G., Cohen, M., Diaz, L., Doucette-Remington, S., Dripps, W., Habron, G., Harré, N., Jarchow, M., Losch, K., Michel, J., Mochizuki, Y., Rieckmann, M., Parnell, R., Walker, P., & Zint, M. (2021). Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustainability Science, 16(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillón, M. (2019). The balcony (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culén, A. L., & Gasparini, A. A. (2019). STEAM education: Why learn design thinking? In Z. Babaci-Wilhite (Ed.), Promoting language and STEAM as human rights in education: Science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics (pp. 91–108). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, P., Tsourlidaki, E., Mentxaka, I., Vicente, T., Gomes, M., & Doran, R. (2021). Thinking in STEAM education: A legacy from the islands diversity for science education project. Ellinogermaniki Agogi. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, J., & Burcak, F. (2019). Young children’s contributions to sustainability: The influence of nature play on curiosity, executive function skills, creative thinking, and resilience. Sustainability, 11(15), 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2022). GreenComp: The European sustainability competence framework. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/greencomp-european-sustainability-competence-framework_en (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Francis, M., & Lorenzo, R. (2002). Seven realms of children’s participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1), 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geitz, G., & de Geus, J. (2019). Design-based education, sustainable teaching, and learning. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1647919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M., & Somerville, M. (2015). Sustainability education: Researching practice in primary schools. Environmental Education Research, 21(6), 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. A. (2013). Children’s participation: The theory and practice of involving young citizens in community development and environmental care. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman-Bergholm, M. (2022). Storytelling as an educational tool in sustainable education. Sustainability, 14(5), 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, M., & Roche, J. (2023). RISING strong: Sustainability through art, science, and collective community action. Sustainability, 15(20), 14800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadpanahi, P., Xu, L., Elkadi, H., & Ang, S. (2012, September 8–20). ‘Kids in Design’: Designing creative schools with children. The 2nd International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2012), Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Katsenou, C., Flogaitis, E., & Liarakou, G. (2013). Exploring pupil participation within a sustainable school. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2), 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinaki, K., & Georgiadou, Z. (2024). Children as the designers of their everyday life. Integrating design thinking in primary education. European Journal of Education Studies, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, I.-M., & Paloniemi, R. (2023). Learning and agency for sustainability transformations: Building on Bandura’s theory of human agency. Environmental Education Research, 29(1), 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkeli, S., Manolas, E., Ioannou, K., & Tsantopoulos, G. (2018). Socio-cultural impact of energy saving: Studying the behaviour of elementary school students in Greece. Sustainability, 10(3), 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovska, M., & Xu, L. (2013). Children and university architecture students working together: A pedagogical model of children’s participation in architectural design. CoDesign, 9(4), 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising article 12 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, V., Rombach, M., Dean, D., & Rennie, H. G. (2022). A design thinking approach to teaching sustainability. Journal of Marketing Education, 44(3), 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N. (2010). The analysis of classroom talk: Methods and methodologies. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Million, A., Parnell, R., & Coelen, T. (2018). Editorial: Policy, practice and research in built environment education. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers—Urban Design and Planning, 171(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlacci, J. L. (2020). The role of built environment education programs in environmental education [Master’s thesis, Royal Roads University (Canada)]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A., Ekung, S., Kugblenu, G., & Mushtaha, E. S. N. (2024). Chapter 10: Education for sustainable development, the built environment, and the sustainable development goals. In The Elgar companion to the built environment and the sustainable development goals. Edward Elgar Publishing. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781035300037/book-part-9781035300037-19.xml (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Perales, F. J., & Aróstegui, J. L. (2024). The STEAM approach: Implementation and educational, social and economic consequences. Arts Education Policy Review, 125(2), 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierandrei, F., & Marengoni, E. (2017). Design culture in school. Experiences of design workshops with children. The Design Journal, 20(Suppl. S1), S915–S926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, M., Marinić, I., Stanisavljević, A., & Dika, I. R. (2024). Environmental education on sustainable principles in kindergartens—A foundation or an option? Sustainability, 16(7), 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöllänen, S. H. (2011). Beyond craft and art: A pedagogical model for craft as self-expression. International Journal of Education Through Art, 7(2), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punzalan, C. H., & Balanac, L. M. (2020). Students’ participation in tree planting activity: Promoting the 21st century environmental education. Journal of Sustainability Education, 24. Available online: https://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/students-participation-in-tree-planting-activity-promoting-the-21st-century-environmental-education_2020_12/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ramani, G. B., & Brownell, C. A. (2014). Preschoolers’ cooperative problem solving: Integrating play and problem solving. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 12(1), 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. (2012). A greener future: The active role of place in enhancing ecoliteracy in children. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 29(3), 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, W., Pauw, J. B., Olsson, D., Gericke, N., De Maeyer, S., & Van Petegem, P. (2020). Redefining action competence: The case of sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(4), 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridi, S. (2015). The role of interactive visual art learning in development of young children’s creativity. Creative Education, 6(21), 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A., & Kumar, A. (2024). Community engagement and education for eco-conscious health. In P. K. Prabhakar, & W. Leal Filho (Eds.), Preserving health, preserving earth: The path to sustainable healthcare (pp. 81–102). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsdottir, A. E., Olsson, D., Sinnes, A. T., & Wals, A. (2024). The relationship between student participation and students’ self-perceived action competence for sustainability in a whole school approach. Environmental Education Research, 30(8), 1308–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (n.d.). Education for sustainable development. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. UNESCO Bibliothèque Numérique. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=fr (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- UNESCO & MECCE. (2024). Education and climate change: Learning to act for people and planet. UNESCO & Monitoring and Sustainability Education Research Institute. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000389801 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- UNESCO Digital Library. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Vesterinen, M., & Ratinen, I. (2024). Sustainability competences in primary school education—A systematic literature review. Environmental Education Research, 30(1), 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, S. J. (2011, November 17–19). Using principles of education to drive practice in sustainable architectural co-design with children. ANZAScA. 45th Annual Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Sydney, Australia. Available online: https://archscience.org/paper/using-principles-of-education-to-drive-practice-in-sustainable-architectural-co-design-with-children/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Wake, S. J., & Eames, C. (2013). Developing an ‘ecology of learning’ within a school sustainability co-design project with children in New Zealand. Local Environment, 18(3), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., & Izadpanahi, P. (2016). Creative architectural design with children: A collaborative design project informed by Rhodes’s theory. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 4(3–4), 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariou, A., & Symeou, L. (2009). The local community as a means for promoting education for sustainable development. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 7(4), 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).