Abstract

The widespread adoption of virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the integration of Learning Management Systems (LMSs) into Higher Education, positioning them as essential tools in blended learning environments. LMSs provide teachers with a wide range of tools and functionalities, generating heterogeneous teaching strategies and providing many useful indicators for analysis. However, the complexity of log data combined with the intricacies of hybrid environments presents a significant challenge. This paper presents a quantitative approach to analysing LMS log data in Higher Education, with a specific focus on identifying and characterising teaching strategies implemented in the post-pandemic context. It seeks to examine the extent to which virtual classrooms have been effectively integrated into teaching practices and to assess how different techno-pedagogical approaches influence students’ academic performance. Moreover, we try to develop and define a comprehensive methodology for data treatment, including selection of analytical variables, the identification and clustering of usage profiles based on LMS interactions, and a comparative interpretative analysis of the findings. Our results suggest that the techno-pedagogical strategies are not uniformly effective across all areas of knowledge. This highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of how these strategies interact with disciplinary traditions, pedagogical practices, and student profiles.

1. Introduction

Understanding how digital technologies are integrated into university teaching practices remains a central concern in current research on Higher Education. While the adoption of Learning Management Systems (LMSs) has become nearly ubiquitous, there is still limited empirical evidence on how instructors actually use these platforms and whether different patterns of use are associated with varying academic outcomes. This article presents an observational study that analyses LMS log data to identify distinct techno-pedagogical approaches and examine their relationship with student performance indicators. In doing so, it contributes to the ongoing efforts to develop evidence-based frameworks for interpreting digital teaching practices and assessing their impact in diverse disciplinary contexts.

1.1. Background: LMS Integration and the Rise of Data-Driven Education

Learning analytics and educational data mining are significantly transforming the methods and tools used to understand educational processes, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic. The generalised adoption of virtual classrooms during this period significantly accelerated the integration of LMSs into Higher Education, positioning them as essential tools in blended learning environments (Quesada et al., 2023). Teachers can use the LMSs in different ways, establishing different blended teaching strategies that can define varied techno-pedagogical approaches. The increased use of LMSs, combined with other technological innovations related to Internet, mobile devices and big data, has generated an unprecedented volume and variety of educational data and contributed to the emergence of data-driven approaches in education (Sghir et al., 2023).

In parallel with the widespread integration of LMSs into Higher Education, there is a significant and increasing interest in exploring methods to understand and explain these techno-based teaching strategies and proving their effectiveness (Regueras et al., 2019; Ross et al., 2025). The effectiveness of learning processes can be assessed through different indicators, with the students’ academic performance being one of the most widely used. At the institutional level, academic performance can be defined as the extent to which educational goals are achieved, and it is usually measured through students’ grades (Al-Tameemi et al., 2023; York et al., 2015). Furthermore, low academic performance is one of the factors that influence student dropout, which is a crucial problem for both Higher Education institutions and society at large (Llauró et al., 2024; Nurmalitasari et al., 2023).

Knowing which techno-pedagogical strategies lead to better academic performance is therefore of considerable interest to academic authorities and the teaching community. However, automatically identifying the technology-based teaching strategies implemented by instructors from LMS usage data remains a complex and unresolved challenge. Moreover, there is a broader research gap regarding frameworks and methodologies that allow for the systematic capture, representation, and analysis of learning design in digital environments. As Mangaroska and Giannakos (2019) point out, despite increasing interest in linking learning design with analytics, few operational models have been established to trace pedagogical intentions through platform log data. Similarly, Lockyer et al. (2013) emphasise the need to develop “design-aligned” analytics that go beyond behavioural metrics to consider pedagogical dimensions. Without such frameworks, the interpretation of LMS usage remains largely superficial and disconnected from the underlying instructional rationale. Consequently, there is a growing demand for methods that bridge the gap between platform use and pedagogical intent, allowing researchers and institutions to better evaluate the effectiveness of digital teaching strategies.

1.2. Towards Interpretable and Instructor-Centred Learning Analytics

This paper aims to address the following research question: Are there significant differences between the effectiveness of different techno-pedagogical approaches on students’ academic performance? Specifically, it examines whether certain techno-pedagogical approaches–particularly those that promote meaningful interaction, provide effective feedback, and enable systematic monitoring of learning–could be positively correlated with better academic outcomes. In this sense, previous studies have highlighted that maintaining student engagement is a persistent challenge, and that the implementation of effective strategies, such as the inclusion of interactive elements, is essential for enhancing both engagement and performance (Akpen et al., 2024). However, when integrating technology into teaching, student performance may also be influenced by multiple additional factors, including instructors’ confidence and digital competence, as well as the specific academic discipline or area of knowledge (Torstrick & Finke, 2025). In this regard, Tinjić and Nordén (2024) show that digitalization impacts students’ performance and that the effect varies across disciplines. They find that digitalization negatively impacts practical disciplines, such as Health and Social Work, in contrast to theoretical disciplines, such as Business Administration and Mathematics. There are other more specific studies that analyse this issue in hybrid scenarios. For example, Whitelock-Wainwright et al. (2020) analyse data from a sample of 6040 courses and show that differences depending on discipline are particularly noted in blended learning.

As an additional contribution to the field of academic analytics, this paper proposes an innovative methodology for LMS data treatment, which could contribute to fill the existing gap in frameworks for capturing and systematising learning design data (Mangaroska & Giannakos, 2019). The proposed methodology incorporates an interpretative and qualitative analysis of instructor behaviours and course configurations within the LMS. This aspect is particularly relevant, as some studies suggest that the limited interpretability of machine learning models constitutes a barrier to the effective implementation of learning analytics and educational data mining in educational environments (Salem & Shaalan, 2025). Furthermore, the lack of continuous digital traces in face-to-face courses represents another major challenge for the application of learning analytics (Rodríguez-Ortiz et al., 2025). The methodology is based on the abstraction of a set of concrete actions performed in a broad educational context and emphasises data pre-processing as a critical step in data-driven research. At this stage, feature selection emerges as one of the most widely used techniques in learning analytics, particularly when dealing with the large volumes of information generated from LMS logs (Sghir et al., 2023).

While most methodologies for analysing LMS logs rely on data from student interactions (Chytas et al., 2022; Manhiça et al., 2022), this study takes a different approach by focusing on teacher interaction with the LMS. By examining the techno-pedagogical design implemented by instructors, the proposed methodology offers a novel perspective that contrasts with the predominant emphasis in learning analytics on student behaviour and predictive modelling (Avello Martínez et al., 2023; Marticorena-Sánchez et al., 2022; Sghir et al., 2023). Despite the increasing adoption of digital tools in Higher Education, previous studies in learning analytics have paid relatively little attention to instructors’ pedagogical intentions and the design decisions behind the use of LMS tools. As Lockyer et al. (2013) and Persico and Pozzi (2015) point out, the interpretative dimension of learning design–how teachers structure and orchestrate activities within LMS environments–has often been overlooked, despite its potential to inform pedagogical action and support reflective teaching.

Moreover, most teacher-focused interventions in the field are limited to the development of dashboards, and more empirical studies are needed to support instructors in making informed pedagogical decisions that enhance student learning (Pan et al., 2024). In line with this, Viberg et al. (2018) emphasise that the field still lacks conceptual clarity and methodological consistency in connecting teaching strategies with learning analytics indicators. Romero and Ventura (2020) also highlight the need to move beyond predictive approaches and explore the pedagogical meaning of data patterns–especially in blended or face-to-face contexts where digital traces may be incomplete or fragmented. From this perspective, this teacher-centred approach aligns more closely with academic analytics, which adopts a broader institutional view compared to learning analytics and works with academic datasets at the system level. However, unlike other studies that also explore educational data from the perspective of teacher interactions (Alamoudi & Allinjawi, 2025; Nakamura et al., 2023), the proposed methodology incorporates some student interactions into the analysis to better understand how teachers use LMS elements in blended learning contexts. Some empirical studies have shown that even limited student log data can be meaningfully interpreted when analysed in relation to teachers’ instructional purposes–even in blended learning contexts (Ochukut et al., 2024).

1.3. From Data to Interpretation: Study Structure

This study therefore begins with a detailed analysis of the input data. It also includes a proposal for data analysis techniques to select the most significant data for further analysis. Starting from pre-processed data, clustering techniques are applied to identify different groups of teaching strategies. At this stage, expert-based subjective criteria are combined with standardised methods to account for the complexity of blended learning environments and to obtain interpretable results. Finally, the analysis of the impact on students’ academic performance, as well as the interpretative examination of results, is based on the area of knowledge as a key variable.

All these actions are detailed in the following sections, which describe the methodology applied and present the main findings of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

This study proposes a comprehensive methodology for data treatment, including the obtention and selection of analytical variables, the identification and clustering of usage profiles based on LMS interactions, and a comparative, interpretative analysis of the findings.

2.1. Methods

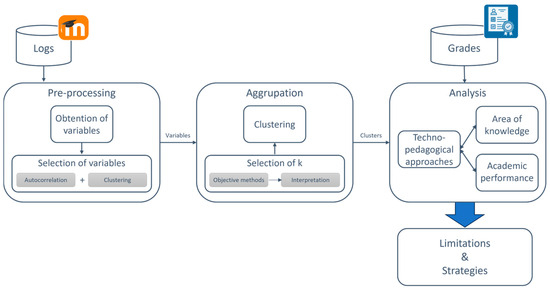

The methodology followed in this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology.

In the first step, the Moodle logs were collected and pre-processed, selecting the variables of interest, since there was a very large amount of data. From the logs, data related to the course design implemented by instructors—specifically, the structure and context of each course—was obtained for the different resources and activities available in Moodle. Additionally, some data on student interactions were collected for the analysis, particularly those relating to active use of the forums, such as initiation of discussion threads and posting of messages by students. Forums in Moodle can be used for a variety of purposes: structured or free-style discussions, communication between students and instructors, peer interactions, question-answer dynamics, or intervention-response exchanges (Ouariach et al., 2024). The way students engage in forum activities may reflect the pedagogical intention of the instructor when designing forum-based activities.

The study incorporates logs from Moodle version 3.6. However, it is important to note that the structure of Moodle’s database has remained highly stable across different versions of the platform, which ensures that the proposed methodology can be directly applied to both earlier and subsequent versions. Furthermore, some of the variables used in the analysis aggregate different types of Moodle activities, thereby mitigating the potential variability introduced by the diversity of plugins installed. This strategy also enhances the study’s applicability across universities with differing plugin ecosystems.

Selected logs were exported to CSV files, and summary tables for each Moodle element were generated using Python 3.11. In total, 22 tables were initially created, containing aggregated information on the various LMS resources and activities used (assign, feedback, folder, etc.). Elements that appeared in less than 1% of the courses–such as badge, book, database and SCORM–were excluded from the analysis. As a result, 18 summary tables were retained, with information corresponding to different Moodle resources and activities (see Table 1, which specifies the percentage of courses in which each Moodle element is used).

Table 1.

Summary tables including structure and context indicators for each Moodle element.

Subsequently, and separately for each of these tables, a data analysis to identify the most relevant variables was conducted. Selecting appropriate variables for clustering is essential to eliminate those that do not provide meaningful information, ensure that the selected variables effectively influence data classification, and facilitate the interpretability of the clustering results. To this end, autocorrelation techniques were applied to detect highly correlated variables and to select non-redundant features, while clustering techniques were used to determine which attributes best define the formation of clusters and to discard irrelevant ones. The combination of both methods—autocorrelation and clustering techniques—enabled the reduction of each dimensionality to one or two variables, which represent the different patterns of use of each Moodle element. The selected variables, along with their description, are presented in Table 2. In most cases, the number of items was the only relevant variable for characterising techno-pedagogical teaching strategies.

Table 2.

Variables selected for each Moodle element.

Once the variables were selected, clustering techniques were applied to define the different groups. Before building the clusters, it was necessary to determine the optimal number of classes. Since there is no universally accepted solution to this problem, a combination of objective methods (such as Elbow, Silhouette or Gap statistic) and subjective methods (based on the interpretability of the resulting clusters) was used. The objective methods did not provide a single optimal value but rather suggested several possible solutions depending on the indicator used. These outcomes were then evaluated using expert-based subjective analysis to identify the solution that offered the most meaningful interpretation. A very low value of k generated cluster, with limited interpretability and practical use, whereas a larger number of clusters resulted in a more detailed classification of courses based on different uses of virtual classrooms. Therefore, this combined approach allowed for the selection of a number of clusters that were both internally homogeneous and conceptually interpretable, thus enabling a more accurate definition of different techno-pedagogical teaching strategies.

The final step was to interpret and label the resulting clusters and analyse the results according to their impact on academic performance across the different areas of knowledge. These performance data were obtained from the Academic Management System database (called SIGMA), which includes course-related administrative information and students’ grades for each course. Academic performance was measured for each course according to different indicators: average grade, dropout rate (percentage of non-presented students), performance rate (percentage of students who passed the course), and success rate (percentage of presented students who passed).

For the data analysis, we used Python 3.11 to generate the summary tables for each Moodle element, and several functions from R 4.2.1. Specifically, k-means was used as the clustering method; fviz_nbclust() and NbClust() were employed to objectively determine the optimal number of clusters; clusterboot() assessed the stability of the resulting clusters; and the Kruskal.test() was used to assess whether the differences between samples were statistically significant.

2.2. Population and Sample

The study was conducted at the University of Valladolid, a public institution of Higher Education in Spain. This institution offers more than 5000 face-to-face undergraduate and postgraduate courses in different knowledge fields. For this study, three broad areas of knowledge were considered: Social Sciences & Humanities, Health Sciences, and Science & Engineering. It employs more than 2000 teachers and enrols approximately 32,000 students each academic year. The university has its own virtual campus, based on the Moodle platform, which has been used to support face-to-face classes since 2009. Every course offered at the University of Valladolid has its corresponding Moodle course, in which both instructors and students are automatically enrolled.

Data for this study were collected from two main sources during the 2021–2022 academic year—the first full academic year after the COVID-19 pandemic—for all undergraduate and postgraduate courses offered at the university: (1) the Virtual Campus (Moodle logs), and (2) the academic management system (student performance data). Specifically, after excluding those courses that did not use the Virtual Campus, a total of 5246 courses were included in the analysis. Of these, 3029 courses belong to Social Sciences & Humanities (57.74%), 486 to Health Sciences (9.26%), and 1731 to Science & Engineering (33.00%).

2.3. Research Ethics

In the field of learning and academic analytics, one of the main ethical challenges concerns data ownership and privacy. In this study, after combining the two databases (Moodle and academic management system) using course identifiers, these identifiers were encoded to minimise potential ethical issues. The anonymity of both students and instructors was strictly preserved by removing all personal identifiers from the dataset. Moreover, no sensitive information, such as racial or ethnic origin, religious beliefs or health-related data, was collected (in accordance with the Spanish Personal Data Protection Act).

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the data and methods described above.

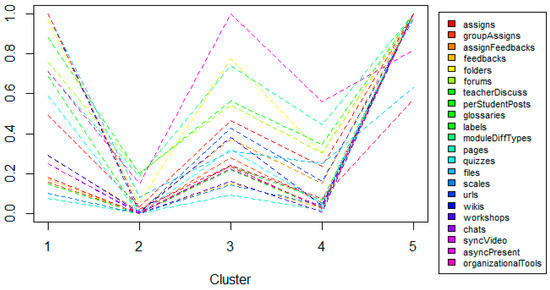

K-means clustering, an unsupervised learning method, was applied to the pre-processed dataset to identify distinct clusters. Based on a combination of objective and subjective criteria for determining the optimal number of clusters, five clusters were ultimately selected. Objective methods indicated two (NbClust and Silhouette method) and four (Elbow method) as better potential values for k. When analysing the data with k = 2, the model simply distinguished between courses that used Moodle and those that did not. With k = 4, more nuanced differences emerged, primarily related to the intensity or level of use of various Moodle modules. For this reason, the use of k = 5 was also explored, which allowed for a more qualitative differentiation between clusters (Regueras Santos et al., 2025). To validate the robustness of the clusters, their stability was assessed being how consistent the clusters are under different conditions. The resulting five clusters demonstrated moderate to high stability, with average stability values exceeding 0.8 according to clusterboot(). This five-cluster solution offered the most interpretable and pedagogically relevant classification, based on the distinct characteristics that defined each group (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Description of the main characteristics of the five clusters identified.

Cluster 1—Balanced and moderated use of virtual classrooms, with a predominant focus on videoconferences, static resources (files, links and asynchronous presentations) and forums, although with limited students’ participation. These courses often featured a high presence of asynchronous video presentations, suggesting that classes recorded during the pandemic were retained and reused. In some cases, these materials may have been repurposed to support flipped classroom approaches.

Cluster 2—Minimal use of virtual classrooms. These courses reflect a lack of pedagogical innovation supported by technology and a continued reliance on traditional, face-to-face teaching models.

Cluster 3—Moderated use of virtual classrooms, characterised by a greater number of group assignments and, above all, increased student participation in forums (second only to cluster 5). These courses suggest a traditional structure supported by the virtual classrooms but incorporating elements of participative practices.

Cluster 4—Limited use of virtual classrooms, primarily as a notice board, repository and platform for submitting and receiving feedback on assignments, but without any group-based assignments. These courses reflect a digital shift from paper-based practices to the use of technology as a repository and/or as a document exchange system for teachers and students.

Cluster 5—Comprehensive and balanced use of virtual classrooms, including both instructional and organisational elements. These courses reflect innovative techno-pedagogical approaches that integrate a variety of Moodle tools in a coherent way, suggesting intentional instructional design supported by digital technologies.

Table 3 presents the definition and relative size of each of the five clusters identified.

Table 3.

Definition of the five clusters.

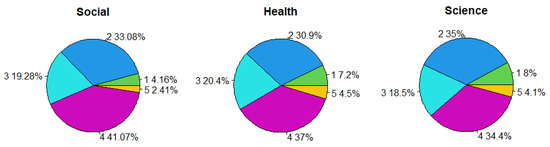

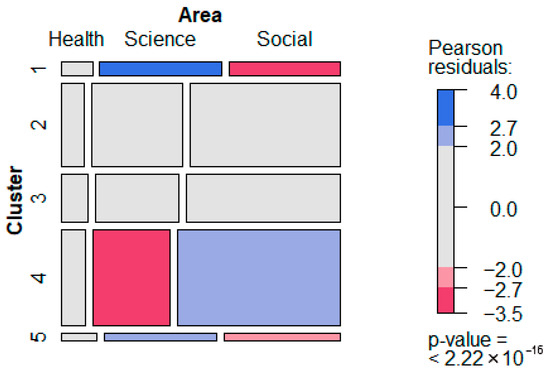

The resulting clusters indicate that the use of LMS did not imply a substantive transformation of teaching strategies but rather, in many cases, a mere digitalization of traditional learning models. Furthermore, preliminary findings showed that the two clusters representing the most innovative uses (clusters 1 and 5) were associated with lower academic performance compared to those less intensive clusters (Sosa Alonso et al., 2025). However, this finding requires further investigation, since the distribution of clusters varies significantly across different areas of knowledge (see Figure 3). In fact, a chi-square test confirmed a significant association between cluster and area of knowledge (X2 = 59.37, p < 0.001). As illustrated in Figure 4, the more innovative clusters are predominantly used in the knowledge fields of Science & Engineering, which have traditionally shown lower performance indicators than other areas of knowledge. Thus, it is necessary to conduct analyses that control for the influence of the academic discipline. By dividing the courses by area of knowledge, it is possible to examine in greater depth whether the use of different techno-pedagogical strategies affects student performance and, thus, address the research question initially posed.

Figure 3.

Distribution of clusters by area of knowledge.

Figure 4.

Correlation mosaic between clusters and area of knowledge.

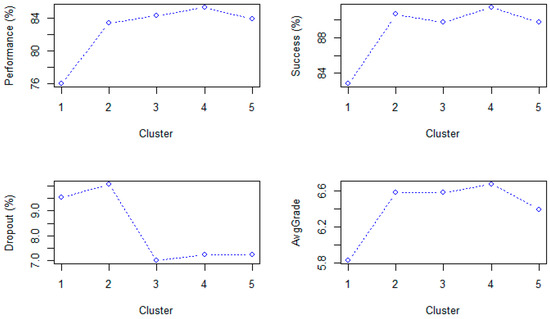

In the case of Social Sciences & Humanities (see Figure 5), cluster 1 showed the lowest performance across almost all indicators, except for dropout rate. Interestingly, cluster 2 recorded the highest dropout rate, which was substantially higher than the others, despite achieving strong results on the remaining indicators. In contrast, cluster 4 demonstrated the best overall performance, except in dropout rate, where cluster 3 performed slightly better. Once these differences were identified, we assessed their statistical significance using the Kruskal–Wallis test, as the data did not follow a normal distribution (according to Shapiro–Wilk test with p < 0.001). The test results indicated statistically significant differences across the five clusters for all four indicators: performance rate (H = 29.097, p < 0.001), success rate (H = 69.57, p < 0.001), dropout rate (H = 10.352, p < 0.001), and average grade (H = 32.007, p < 0.001). These findings show that the techno-pedagogical strategies represented by each cluster are significantly associated with variations in student academic outcomes.

Figure 5.

Indicators of academic performance for Social Sciences & Humanities.

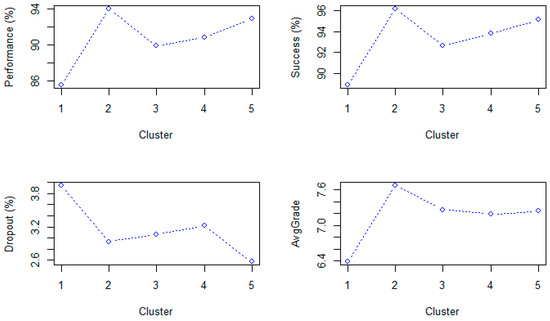

Regarding Health Sciences (see Figure 6), cluster 1 presented the poorest results across all indicators. Cluster 2, by contrast, achieved the highest performance, except in the dropout rate, which was considerably lower in cluster 5. To assess whether these differences were statistically significant, a Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted, as the data did not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.001). The results showed significant differences among the five clusters for all four indicators: performance rate (H = 33.532, p < 0.001), success rate (H = 28.659, p < 0.001), dropout rate (H = 15.869, p < 0.001), and average grade (H = 27.000, p < 0.001). These results confirm once again that different techno-pedagogical strategies are associated with significant variations in academic outcomes.

Figure 6.

Indicators of academic performance for Health Sciences.

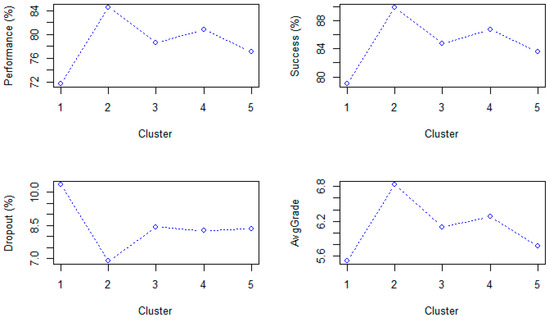

Finally, within the field of Science & Engineering (see Figure 7), cluster 1 again presented the worst values across all indicators, while cluster 2 achieved the highest performance. As observed in the other areas of knowledge, the Kruskal–Wallis test (used for non-normally distributed data, p < 0.001 in Shapiro–Wilk test) indicated statistically significant differences among the five clusters for all four indicators: performance rate (H = 61.983, p < 0.001), success rate (H = 78.604, p < 0.001), dropout rate (H = 29.154, p < 0.001), and average grade (H = 86.554, p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Indicators of academic performance for Science & Engineering.

In general, cluster 1 showed the poorest results across all areas of knowledge, except for the dropout rate in Social Sciences & Humanities, where cluster 2 recorded the worst outcome. On the contrary, cluster 2 achieved the best results in Health Sciences and Science & Engineering, while cluster 4 presented the best performance indicators in Social Sciences & Humanities. Clusters 3 and 5 exhibited similar values across the different indicators.

These findings suggest that the techno-pedagogical strategies associated with each cluster are not uniformly effective across all areas of knowledge. While certain patterns–such as the consistently low performance of cluster 1–appear across disciplines, the effectiveness of more innovative or intensive uses of the LMS (as seen in clusters 1 and 5) seems to vary depending on the academic context. This highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of how technology-supported teaching strategies interact with disciplinary traditions, pedagogical practices, and student profiles.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that the implementation of techno-pedagogical strategies in Higher Education is highly heterogeneous and often does not entail a substantive transformation of teaching practices. This observation aligns with previous research indicating that the widespread adoption of LMSs does not necessarily lead to pedagogical innovation but frequently results in the digital replication of traditional models (Albuquerque et al., 2025; Rapanta et al., 2020; Bond et al., 2021). Our analysis indicates that, contrary to expectations, courses classified as more innovative–particularly those relying on audiovisual materials or flipped classroom formats–do not consistently produce better academic results. These findings contrast with studies such as Sailer et al. (2024), which suggest that active and technology-enhanced strategies can improve learning outcomes when carefully implemented and supported. In particular, traditional models with minimal use of technological tools were associated with better academic indicators in Health Sciences and in Science & Engineering. Similarly, in Social Sciences & Humanities, courses using the LMS mainly as a content repository showed relatively higher performance. While these patterns may reflect a better alignment between teaching approaches and disciplinary expectations, they should be interpreted with caution, as unmeasured variables–such as prior student knowledge, motivation, or course design quality–may also be influencing the results.

Particularly interesting is the dropout rate in Social Sciences, where courses with low LMS engagement tend to show poorer outcomes. These results suggest that techno-pedagogical strategies must be contextually adapted to each discipline, as echoed by Viberg et al. (2018), who highlight that pedagogical effectiveness is closely tied to the instructional culture and demands of each field.

Our findings align with those of Llauró et al. (2024), who note that in technical degrees, self-regulation and study habits play a key role in academic performance and dropout risk. This could explain why, in Health Sciences and Science & Engineering, cluster 1 shows, by far, the highest dropout rates. Cluster 1 includes teaching strategies that rely heavily on recorded audiovisual materials. It is possible that students become overly reliant on having recorded classes available and postpone their study efforts until the period immediately prior to the exams, potentially increasing dropout risk or lowering performance. This hypothesis, however, requires further investigation. What does seem evident is that new technology-based teaching strategies, such as flipped classroom (also included in cluster 1), must be supported by further research, adequate resources and targeted training to help instructors make effective use of these models and ultimately improve student performance, as also suggested by Brewer and Movahedazarhouligh (2018). Moreover, the significant variability in academic outcomes across clusters and disciplines also points to the need for institutional policies that go beyond simply promoting the use of technology and instead focus on aligning digital strategies with pedagogical goals and disciplinary norms (Persico & Pozzi, 2015; Lockyer et al., 2013).

In the field of Social Sciences & Humanities, the data suggest that even a moderate use of the LMS—primarily as a repository of resources—is associated with better academic outcomes. This indicates that, in less technically demanding disciplines, flexible access to materials may be sufficient to support student learning, particularly when combined with traditional teaching approaches. These results are consistent with the findings of Whitelock-Wainwright et al. (2020), who argue that non-STEM disciplines benefit more from online support than STEM disciplines in blended scenarios. Interestingly, the highest dropout rate in this area was observed in the cluster with the lowest engagement with digital tools, highlighting the potential risk of insufficient integration of technology in supporting student retention.

Institutional context plays a critical role in interpreting these results. It is worth noting that at the University of Valladolid, as mentioned above, every course (subject) is automatically assigned its corresponding Moodle course, regardless of instructors’ willingness or readiness to use it. This may explain the presence of courses with very limited Moodle use, since instructors are neither obliged to utilise the platform nor subject to any form of supervision or quality assurance. In this context, it could be of interest to implement some system to verify if online courses comply with an established quality rubric, such as those of the Quality Matters framework used in other institutions (Gregory et al., 2020; Lowenthal & Hodges, 2015). However, defining and applying such quality criteria becomes considerably more challenging when e-learning platforms serve only as a support of face-to-face classes. To address this limitation, another potential solution would be for academic institutions to implement automated mechanisms that certify instructors’ use of the LMS, in order to recognise their work, suggest best practices, and establish institutional policies (Regueras et al., 2019).

Another important consideration concerns the training received by instructors. While the University of Valladolid offers regular, voluntary training sessions on the use and pedagogical integration of Moodle, participation is not mandatory, nor is it systematically tracked. Similarly, no formal training in educational design is required for instructors, and access to pedagogical support services may vary across departments and disciplines. This variability may partially explain the differences observed between subject areas in the present study. For example, disparities in digital competence, support structures, or teaching cultures could influence the adoption of more or less innovative techno-pedagogical strategies. Recent literature confirms that digital competence among Higher Education instructors is still highly uneven, and training opportunities are often voluntary, fragmented, and lack institutional coordination (Basantes-Andrade et al., 2022; Garzón Artacho et al., 2020). Unfortunately, we did not have access to data on training or design review practices at the instructor level, which constitutes a limitation of the study.

In terms of methodological limitations, the study relied exclusively on quantitative indicators of academic performance—average grade, dropout rate, success rate, and performance rate. While these are commonly used in educational data mining and learning analytics (Tempelaar et al., 2015), they only offer a partial view of the learning process. These metrics do not capture important qualitative dimensions such as students’ engagement, depth of understanding, critical thinking, or satisfaction with the learning experience (Long & Siemens, 2011). Future research should adopt mixed-method approaches that integrate student feedback, self-regulated learning measures, and direct evidence of competence development to better assess the impact of techno-pedagogical strategies.

Blended contexts are also an important limitation for analysis of teaching strategies, since we only have partial digital traces of learning interactions (Rodríguez-Ortiz et al., 2025). For example, face-to-face interactions reduce the participative use of LMS, limiting the representativeness of log data as a proxy for overall student engagement (Alamoudi & Allinjawi, 2025). Consequently, certain pedagogical practices–such as in-class discussions, group collaborative dynamics, or paper-based tasks–remain invisible in the digital record, despite their potential influence on academic outcomes. Future studies should, then, consider integrating multimodal data sources (e.g., classroom observation, teacher interviews, student self-reports) to provide a more holistic view of teaching strategies in blended learning environments.

Finally, the data correspond to the 2021–2022 academic year—the first full year after the COVID-19 pandemic—when teaching practices were still transitioning to hybrid models. This transitional context, marked by institutional urgency and limited digital preparedness, may have influenced both instructional strategies and student behaviour. Therefore, the findings may reflect temporary adaptations rather than stable, long-term trends in technology use (Bond et al., 2021; Rapanta et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

Considering the results and the limitations identified, this study highlights the complexity of assessing the effectiveness of techno-pedagogical strategies in blended learning environments. The partial visibility of learning interactions in LMS data, the influence of academic disciplines on teaching models and performance indicators, and the transitional context of the post-pandemic academic year all constrain the applicability of the findings to broader educational settings. However, beyond summarising empirical patterns, the analysis offers several conceptual, methodological, and practical contributions that advance current discussions in the field.

First, the study shows that the relationship between techno-pedagogical strategies and academic performance is far from linear. More technologically “innovative” approaches do not necessarily produce better results, while low-tech or traditional models may be comparatively effective in certain disciplinary contexts. This finding aligns with previous work questioning deterministic assumptions about technology-enhanced learning and reinforces the need for discipline-sensitive frameworks that account for epistemological, cultural and organisational characteristics of each field.

Second, the results indicate that the effective implementation of techno-pedagogical strategies may be influenced by a combination of factors beyond the technological tools themselves, such as the quality of instructional design, students’ self-regulation skills, and the broader institutional ecosystem. The disciplinary differences observed suggest that future research should move beyond measuring technology adoption and focus more on understanding pedagogical intentions and the conditions under which certain strategies are more likely to be effective.

Third, the study makes a methodological contribution by proposing a clustering-based approach focused on instructors’ LMS interactions, rather than exclusively on student behaviour. This offers a novel angle for analysing teaching strategies in blended environments and provides a replicable procedure for institutions seeking to understand patterns in instructional design at scale.

From a practical perspective, the findings have implications for institutional policy and faculty development. The heterogeneity observed across courses suggests the need for more structured support systems, including training in educational design, enhanced digital competence pathways, and quality assurance mechanisms—quality rubrics—adapted to blended learning contexts.

Finally, while the study offers relevant insights, its observational nature limits the extent to which causal claims can be made. Academic performance is shaped by multiple latent factors—such as students’ prior knowledge, engagement, or motivation—that were not captured in the dataset. Future research should therefore adopt mixed-method approaches and integrate additional data sources, such as student feedback, multimodal classroom observations, or pedagogical configurations. Research conducted in more stable post-pandemic contexts will also be necessary to evaluate whether the patterns identified here reflect longer-term tendencies or transitional behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; methodology, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; software, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; validation, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; formal analysis, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; investigation, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; resources, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; data curation, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; writing—review and editing, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; visualization, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á.; supervision, L.M.R., M.J.V., J.P.d.C. and S.Á.-Á. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (TED2021-130743B-I00).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Secretary General of the University of Valladolid (approval code: LJA1/vXJxRIHrb2NODImhQ==), following a favourable report issued by its Data Protection Officer (26 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation is not required as per ethical approval and local authorization granted by the University of Valladolid.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this article is not readily available because it cannot be shared with third parties in accordance with the ethical approval obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akpen, C. N., Asaolu, S., Atobatele, S., Okagbue, H., & Sampson, S. (2024). Impact of online learning on student’s performance and engagement: A systematic review. Discover Education 3, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, M. A., & Allinjawi, A. A. (2025). Determining patterns of instructors’ usage of blackboard features using a clustering technique. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Computing and Information Technology Sciences, 14(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, J., Rienties, B., & Divjak, B. (2025, March 3–7). Decoding learning design decisions: A cluster analysis of 12,749 teaching and learning activities. 15th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (LAK ‘25) (pp. 407–417), Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tameemi, R. A. N., Johnson, C., Gitay, R., Abdel-Salam, A.-S. G., Hazaa, K. A., BenSaid, A., & Romanowski, M. H. (2023). Determinants of poor academic performance among undergraduate students—A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 4, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avello Martínez, R., Fernández-Álvarez, D., & Gómez Rodríguez, V. G. (2023). Moodle logs analytics: An open web application to monitor student activity. Universidad y Sociedad, 15(4), 715–721. Available online: https://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus/article/view/4030 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Basantes-Andrade, A., Casillas-Martín, S., Cabezas-González, M., Naranjo-Toro, M., & Guerra-Reyes, F. (2022). Standards of teacher digital competence in higher education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 14(21), 13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M., Bedenlier, S., Marín, V. I., & Händel, M. (2021). Emergency remote teaching in higher education: Mapping the first global online semester. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R., & Movahedazarhouligh, S. (2018). Successful stories and conflicts: A literature review on the effectiveness of flipped learning in higher education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(4), 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytas, K., Tsolakidis, A., Triperina, E., & Skourlas, C. (2022). Educational data mining in the academic setting: Employing the data produced by blended learning to ameliorate the learning process. Data Technologies and Applications, 57(3), 366–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón Artacho, E., Martínez, T. S., Ortega Martín, J. L., Marín Marín, J. A., & Gómez García, G. (2020). Teacher training in lifelong learning—The importance of digital competence in the encouragement of teaching innovation. Sustainability, 12(7), 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R. L., Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J., & Cook, V. S. (2020). Community college faculty perceptions of the quality MattersTM rubric. Online Learning, 24(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llauró, A., Fonseca, D., Villegas, E., Aláez, M., & Romero, S. (2024). Improvement of academic analytics processes through the identification of the main variables affecting early dropout of first-year students in technical degrees. A case study. International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 9(1), 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing pedagogical action: Aligning learning analytics with learning design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P., & Siemens, G. (2011). Penetrating the fog: Analytics in learning and education. EDUCAUSE Review, 46(5), 30–40. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2011/9/penetrating-the-fog-analytics-in-learning-and-education (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Lowenthal, P., & Hodges, C. (2015). In search of quality: Using quality matters to analyze the quality of massive, open, online courses (MOOCs). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaroska, K., & Giannakos, M. (2019). Learning analytics for learning design: A systematic literature review of analytics-driven design to enhance learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 12(4), 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhiça, R., Santos, A., & Cravino, J. (2022, June 22–25). The use of artificial intelligence in learning management systems in the context of higher education: Systematic literature review. 17th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI) (pp. 1–6), Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marticorena-Sánchez, R., López-Nozal, C., Ji, Y. P., Pardo-Aguilar, C., & Arnaiz-González, Á. (2022). UBUMonitor: An open-source desktop application for visual e-learning analysis with moodle. Electronics, 11(6), 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K., Horikoshi, I., Majumdar, R., & Ogata, H. (2023, December 4–8). Visualization of instructional patterns from daily teaching log data. International Conference on Computers in Education, Matsue, Japan. Available online: https://library.apsce.net/index.php/ICCE/article/view/4733 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Nurmalitasari, Awang Long, Z., & Faizuddin Mohd Noor, M. (2023). Factors influencing dropout students in higher education. Education Research International, 2023(1), 7704142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochukut, S., Hernedez-Leo, D., Oboko, R. O., & Miriti, E. K. (2024). Alignment of learning design with learning analytics: Case of MOODLE blended learning course in higher education. In Lecture notes in networks and systems (Vol. 1171, pp. 201–210). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouariach, F. Z., Nejjari, A., Ouariach, S., & Khaldi, M. (2024). Place of forums in online communication through an LMS platform. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 11(1), 096–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z., Biegley, L., Taylor, A., & Zheng, H. (2024). A systematic review of learning analytics: Incorporated instructional interventions on learning management systems. Journal of Learning Analytics, 11(2), 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, D., & Pozzi, F. (2015). Learning analytics to support teachers’ decision-making. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1170–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, B. V., Zarco, C., & Cordón, O. (2023). Mapping the situation of educational technologies in the spanish university system using social network analysis and visualization. International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 8(2), 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueras, L. M., Verdú, M. J., Castro, J. D., & Verdú, E. (2019). Clustering analysis for automatic certification of LMS strategies in a university virtual campus. IEEE Access, 7, 137680–137690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueras Santos, L. M., Verdú Pérez, M. J., & Castellanos Nieves, D. (2025). Analíticas académicas y análisis de aulas virtuales. Un estudio en los tiempos post-Covid19. In M. Area-Moreira, J. Valverde-Berrocoso, & B. Rubia-Avi (Eds.), Transformación digital de la enseñanza universitaria. Analíticas académicas y escenarios de futuro (pp. 99–115). Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ortiz, M. Á., Santana-Mancilla, P. C., & Anido-Rifón, L. E. (2025). Machine learning and generative ai in learning analytics for higher education: A systematic review of models, trends, and challenges. Applied Sciences, 15(15), 8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C., & Ventura, S. (2020). Educational data mining and learning analytics: An updated survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 10(3), e1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T., Sondergaard, R., Ives, C., Han, A., & Graf, S. (2025). Enhancing access to educational data for educators and learning designers: Staged evaluation of the academic analytics tool. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 30, 1371–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M., Maier, R., Berger, S., Kastorff, T., & Stegmann, K. (2024). Learning activities in technology-enhanced learning: A systematic review of meta-analyses and second-order meta-analysis in higher education. Learning and Individual Differences, 112, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M., & Shaalan, K. (2025). Unlocking the power of machine learning in E-learning: A comprehensive review of predictive models for student performance and engagement. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 19027–19050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghir, N., Adadi, A., & Lahmer, M. (2023). Recent advances in predictive learning analytics: A decade systematic review (2012–2022). Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 8299–8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa Alonso, J. J., de Castro Fernández, J. P., & Regueras Santos, L. M. (2025). Configuraciones tecnopedagógicas en aulas virtuales y rendimiento académico: Un análisis comparativo a partir de analíticas de aprendizaje. In M. Area-Moreira, J. Valverde-Berrocoso, & B. Rubia-Avi (Eds.), Transformación digital de la enseñanza universitaria. Analíticas académicas y escenarios de futuro (pp. 117–142). Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Tempelaar, D. T., Rienties, B., & Giesbers, B. (2015). In search for the most informative data for feedback generation: Learning analytics in a data-rich context. Computers in Human Behavior, 47, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinjić, D., & Nordén, A. (2024). Crisis-driven digitalization and academic success across disciplines. PLoS ONE, 19(2), e0293588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torstrick, R., & Finke, J. (2025). Using technology to support success: Assessing value using strategic academic research and development. Education Sciences, 15(5), 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberg, O., Hatakka, M., Bälter, O., & Mavroudi, A. (2018). The current landscape of learning analytics in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock-Wainwright, A., Tsai, Y.-S., Lyons, K., Kaliff, S., Bryant, M., Ryan, K., & Gaševic, D. (2020, March 23–27). Disciplinary differences in blended learning design: A network analytic study. 10th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (LAK ‘20) (pp. 579–588), Frankfurt, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, T. T., Gibson, C., & Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and measuring academic success. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 20(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).