Abstract

Teacher wellbeing is a matter of social justice since burnout syndrome disproportionately affects those working in under-resourced and diverse educational contexts by limiting their ability to foster inclusive and equitable learning. To this situation, art museums respond as pedagogical spaces for wellbeing while contributing to socially just and sustainable arts education. School teachers are offered new opportunities for ongoing professional development tailored to their well-being needs, such as burnout prevention. A two-round international Delphi study with experts from universities, schools, museums, and arts-and-wellbeing organizations (n = 26 1st round, n = 17 2nd round)—rather than focusing on teachers’ personal accounts—develops consensus on a pedagogical framework for art-based programs designed to prevent teacher burnout and enhance wellbeing. The findings identify nine pedagogical guidelines highlighting participatory approaches—audience, objectives, content, methodology, scheduling, facilitators, activities, evaluation, and program adherence. By positioning art museums as democratic, inclusive, and relational spaces, the framework advances the role of the arts in addressing systemic challenges in education, such as supporting teachers’ wellbeing. This research contributes to the international debate on socially just arts education by demonstrating how teacher wellbeing can be fostered through innovative, evidence-based museum practices aligned with SDG 4.

Keywords:

arts education; teacher wellbeing; social justice; equitable access; museums; SDG 4; Delphi study 1. Introduction

There is a recognized and ongoing problem concerning the relationship between school teachers and their profession, as evidenced by the prevalence of burnout syndrome (Zhang et al., 2024)—a psychological syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment, which occurs in response to chronic work-related stress (Maslach, 1982, 1993). Over the years, numerous statistics and reports have highlighted the international phenomenon of teachers leaving the profession (Xipell-Font et al., 2024; notably during the Great Resignation of mid-2020). In Spain, for instance, Europa Press reported on 8 July 2013 that a study from the University of Murcia (Spain) indicated that 65% of elementary, secondary, and high school teachers suffer from burnout. On 25 November 2018, Las Provincias published a column about the Cisneros Report, which highlighted classroom conflicts caused by undisciplined and aggressive students, leading one in ten teachers to consider leaving the profession. Moreover, on 4 December 2019, La Voz de Asturias reported statements from a teacher describing symptoms of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of professional fulfilment. In particular, contemporary scholars have underscored depersonalization as a pervasive issue in Western societies (Han, 2015). Beyond its psychological consequences, teacher burnout has profound implications for equity and social justice in education. Overburdened and emotionally exhausted, teachers are less able to sustain inclusive practices, support diverse learners, and engage with socially just pedagogies. Teacher wellbeing can no longer be addressed as an individual matter; instead, it requires structural conditions for advancing equitable and sustainable educational systems, as highlighted in the UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 on quality education (SDG 4).

While the issue of teacher burnout is often explored through teachers’ own narratives, this study instead approaches the topic from the standpoint of experts working across education and the arts, with the aim of developing a framework that can later inform teachers’ practice and wellbeing. Given the growing recognition of creativity’s importance in education—as famously highlighted by Sir Ken Robinson in his talk Do Schools Kill Creativity? (TED, 2009) and more recently by the inclusion of creative thinking in PISA 2022, the development of creative competences through aesthetic experiences and their influence on professional wellbeing has also become an emerging area of research (Mughal et al., 2022).

On the one hand, artistic creativity allows for the expression and representation of a personal world, displaying vulnerability and sharing fragility (Anderson et al., 2022). On the other hand, when it is an experience intimately connected with the deeper self, it becomes an essential mediator in the relationship with others (Karkou & Glasman, 2004; Mosavarzadeh & Ding, 2022). It is within this possibility of a relationship with the other that the connection between creativity and burnout finds meaning, where the latter is understood as a state of chronic stress in which the individual lacks the necessary resources to effectively manage the situation. Hence, allowing oneself to appear vulnerable and sharing one’s exhaustion with someone else becomes meaningful (Alavinia & Pashazadeh, 2018).

Previous research done by the authors of this paper shows a correlation between creative competence and teacher burnout, with the former serving as a protective factor against the latter (Urpí et al., 2025). Teacher creative competence serves personal wellbeing, but mostly enhances the capacity to open up inclusive, democratic, and culturally responsive classroom environments. In this sense, creativity enables teacher agency by allowing educators to act autonomously and meaningfully within their professional contexts, transforming constraints into opportunities for pedagogical innovation. Creative agency thus functions as a bridge between individual wellbeing and collective or social transformation, since it empowers teachers to translate personal growth into educational practices that foster equity and justice (Anderson et al., 2022). Creativity becomes a form of agency that allows teachers to challenge deficit models of education, to engage with diverse narratives, and to sustain socially just pedagogical practices.

Extensive research has shown that the arts—as the ultimate creative possibility—generate dynamics of connection as a preventive measure for individual and interpersonal health, as well as reciprocal dynamics of mutuality, based on empathy, a sense of closeness, and responsibility among individuals (Anderson et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2018). The potential of the arts can be found in the creative and timeless spaces where individuals find opportunities for personal healing, health improvement, and well-being (Musaio, 2013; Basanta & Urpí, 2024). This is possible because the arts can offer teachers an alternative space to the dichotomies of good/bad or valuable/not valuable, where ambiguity, uncertainty, the limits of consciousness, and independent thought emerge as inevitable, akin to life itself beyond the school (Sellman & Cunliffe, 2012).

While training programs for creativity and well-being are crucial for developing preventive practices for mental health and self-care, they must be carefully implemented (Falk, 2025). From a pedagogical perspective, the context of the teacher training programs seems the most appropriate setting to provide a response (based on the principles inherent to pedagogy) to the prevention of burnout and its symptoms. Since the beginning of the century, many cultural and arts-related institutions, such as the art museum, have been exploring how personal creativity developed through the arts is a transformative resource for regeneration and creative empowerment, with an undeniable reference to the development of one’s personality and bio-psychosocial growth (Falk, 2022; Fancourt & Finn, 2019; Mughal et al., 2022).

The ICOM (2022) presents the museum as a civic and intrinsically pedagogical space where access to arts education expands beyond the classroom. For example, by designing formative experiences for reflection, cultural dialogue and creative participation, museums help school teachers to thrive (Šveb Dragija & Jelinčić, 2022) while also contributing to socially just forms of arts education. The art museum might facilitate finding a creative, sustainable, and non-restrictive space for the re-personalization of educational tasks, emotional rest, or reflecting on professional fulfilment. Educators are already subjects of participation in art museum programs but most of them involve the integration of artistic content into school curricula (Basanta & Urpí, 2024). However, just as the art museum is making efforts to integrate minorities into its well-being initiatives, there may be an opportunity to do something similar for teachers. This study focuses on the perspectives of experts with direct professional experience in the intersection of arts education and teacher wellbeing. These experts include school teachers, museum educators, academics, and professionals from arts-and-wellbeing organizations. The aim is not to capture individual teachers’ lived experiences directly, but to develop expert consensus on how arts-based museum programs can best support teacher wellbeing and prevent burnout. Insights from this Delphi study will serve as a foundation for future research centered on teachers’ own perspectives and experiences at the art museum.

This study therefore situates the challenge of teacher burnout within the broader debate on socially just arts education in the museum context. It asks: What pedagogical elements should be considered when designing an arts-based proposal aimed at promoting teacher well-being? How should the objectives, content, methodology, scheduling, activities, and evaluation be designed? What elements will facilitate teachers’ adherence to such programs, and what qualifications should facilitators possess to achieve these aims? By developing a pedagogical framework for museum-based programs that foster teacher well-being, this research contributes to ongoing efforts to ensure that arts education promotes not only individual growth but also equitable, inclusive, and sustainable educational communities, where creative agency serves as a mediating mechanism connecting personal wellbeing with socially transformative educational practices.

2. Design

The authors have previously conducted research on the relationship between creativity and burnout prevention. In order to compare the findings of this research with elements identified in a review of best practices in art museums aimed at promoting teacher well-being (Basanta & Urpí, 2024), a study is proposed here to reach consensus on a pedagogical framework for designing arts-based initiatives focused on burnout prevention. Towards this end, a questionnaire was designed based on the Delphi method and sent to professional and academic experts in the fields of academia, school education, and museums.

These experts were invited to participate in two rounds to gather their views on nine pedagogical guidelines that might constitute a pedagogical framework, namely a targeted audience, objectives, content, methodology, scheduling, facilitators, activities, evaluation, and program adherence. The collective judgment obtained through a Delphi procedure aggregates and surpasses the limitations of individual judgments.

2.1. Research Questions and Objective

Using the Delphi method, this study aims to establish consensus on the pedagogical guidelines for a framework to design art-based programs that creatively foster teacher well-being and burnout prevention.

2.2. Methodology

The decision to use the Delphi consensus method was driven by several factors, including that (a) relevant experts were geographically dispersed, making face-to-face interviews impractical, while the questionnaire format allows for flexible participation. Likewise, the anonymity of the process is intended to prevent dominant viewpoints, which can lead to a lack of accountability for expressed opinions and hasty decision-making; (b) the method’s practical approach encourages the involvement of practitioners who may be sceptical of research. Furthermore, the iterative nature of the process allows for the exchange, confirmation or revision of opinions and positions; and (c) at least two main row-controlled feedback reports accompanied by the statistical aggregation of group responses and a final questionnaire to confirm the main issues, enables the gathering of high-level expertise in a relatively short time frame.

2.3. Phases and Research Timeline

The study had seven phases (Table 1). The formulation of the research problem and the formulation of tasks to be carried out were completed during 2022 and 2023, whereas the execution of the research itself followed a specific timeline between October 2023 to May 2024 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Delphi phases and timeline 1.

Table 2.

Delphi timeline 2.

2.4. Sample Panellists

The snowballing technique was considered the most appropriate approach given the exploratory and consensus-oriented nature of the Delphi method, where professional recognition and expertise are key. It was used to build the expert database, which was segmented into five professional groups: (1) Arts and well-being institutions, charities or foundations; (2) Schools; (3) Universities or research institutes; (4) Art museums; and (5) Artists, creatives or architects. Also, as some authors recommend working on the database according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Hasson et al., 2000), the expert selection was based on those who met at least one of the following criteria: (a) To have more than 5 years of professional experience; and (b) To have expertise in, at least, one of the following areas: creativity and arts, well-being and burnout, school teaching, university teaching or art education.

The snowballing process with an extensive manual search took place over several months, which included consulting museum websites, university education department directories, and databases of arts and wellbeing organizations, as well as drawing on findings from a previous scoping review (Urpí et al., 2025). This iterative process not only helped broaden the reach of the expert pool but also reflects the perseverance and systematic effort undertaken by the research team to ensure the panel’s diversity and credibility. According to Cabero (2014) and Jünger et al. (2017), background (publications, cites, years of experience, occupied jobs, etc.), experience and willingness to participate demonstrated within two weeks are the essential qualities of the panellists.

Regarding the number of participants, the heterogeneous nature of this database of experts led to efforts to ensure a minimum number of participants sufficient for result validity, which should be no fewer than a dozen (Martínez Piñeiro, 2003; Powell, 2003). The 135 potential participant panellists were geographically dispersed among Ireland, Australia, Finland, Canada, the United States, Spain, the UK, Italy, and France. Twelve experts declined the invitation, citing lack of time as the primary reason in their email response. Twenty-eight participants responded positively and courteously via email to complete the questionnaire. A total of 26 experts answered the first round, of which 17 remained for the second round (Table 3).

Table 3.

Profile of the experts participating in the first round 3.

2.5. Questionnaire and Rounds

According to the literature on Delphi, the first round is usually qualitative in nature through open-ended questions developed from previous literature review (Urpí et al., 2025), and should last no longer than 30 min to achieve a 70% response rate (Rowe & Wright, 1999). The second round is usually presented in a Likert scale format that recaptures the qualitative comments made in the previous round (Iqbal & Pipon-Young, 2009). However, if the problem is precisely defined from the beginning, the open-ended questionnaire would be omitted, and one would proceed directly to the closed-ended questions, which is what happened in this study. Thus, the two quantitative rounds provided blank spaces for comment or disagreement regarding each question or item.

An email was sent in February 2024 to each of the 135 experts with an invitation to participate. As attachments to the email, the information sheet was included describing the research objectives, the duration of each round, and how the data derived from their participation would be handled; the informed consent form; and the first round questionnaire. A Google Forms document was used for the questionnaire, written in both English and Spanish, allowing the experts to choose whichever language they felt most comfortable with. It incorporated the set of premises from which the study originates. Twenty-six experts participated in the first round. No new panellists were added to the first round, in which 17 participants from the first round continued.

The first round was conducted in April 2024, and due to the saturation of responses observed in the minimal variation between the first and second rounds, coupled with the risk of expert fatigue, the study was concluded one week after sending a reminder email to those who had not yet completed the second round. In the first round, each expert received a table showing the values of their previous rating together with the group’s rating, and the comments collected in the first round. Experts were asked to re-rate their original scores and modify or adjust their responses based on the overall scores if they deemed it necessary.

Their answers were divided into two groups. The first group consists of those working in universities and research Institutes, referred to as academics (AC). The second group comprises professionals working in arts and wellbeing institutions, charities or foundations, museums and schools (PROF). This distinction is important to clarify that the study does not aim to represent teachers’ personal testimonies, but to gather interdisciplinary expert consensus to inform future practical applications with teachers.

2.6. Data Analysis

In spite of the fact that the process for reaching consensus might consist of differing views being expressed, and given the exploratory nature of the study, the stability of the response in both rounds serves as a reliable indicator of consensus (Hasson et al., 2000). According to Rowe and Wright (1999), the convergence of the responses is mainly attributable to conformity. Throughout the two iterations, constructive disagreements are also highlighted.

After each round, quantitative data from Likert questions is analyzed with R version 3.6.1. in RStudio version 1.2.x. to obtain the mean, mode and standard deviation. Subjective analysis is used to explore qualitative data extracted from comments. These comments are sent to the experts in the first round and help them clarify concepts or refine their answers.

3. Results

This section presents and discusses the results obtained in the second round. The results are based on eight pedagogical guidelines for the art-based programs design aimed at teacher burnout prevention and well-being promotion, namely, the objectives, content, methodology, scheduling, facilitators, activities, evaluation, and program adherence. Additionally, Section 4 addresses the type of targeted audience, a matter that recurs throughout the experts’ comments on the open-ended questions. According to Hasson et al. (2000), there is no consistent method for reporting findings in Delphi technique research. Therefore, both graphical and textual representations are used to show the outcomes divided into professionals (PROF) and academics (AC) groups.

3.1. Objectives

The experts were asked to rate the accuracy of the objective design according to four characteristics: generalizable, centered on needs, focused on creative competences and focused on well-being or self-care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Consensus on objectives design.

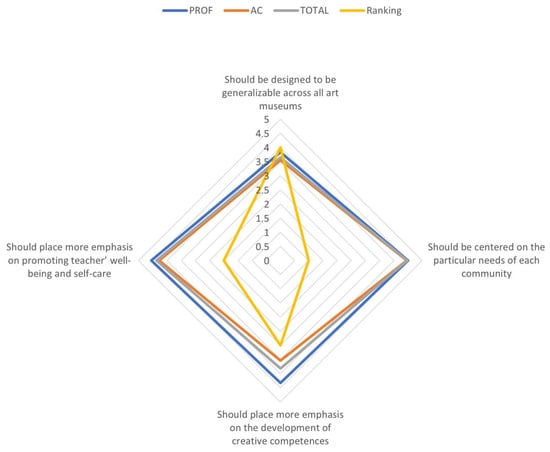

The highest score was given to the importance of grounding the objectives in the needs of the community. The professionals also assigned higher scores to the objective directly related to promoting well-being and self-care, which made it the second highest in the ranking (Figure 1). Academics, however, place more importance on objectives centered on the particular needs of each community and they emphasize the importance of avoiding direct sample collection from schools to exclude those not intrinsically motivated to participate. Furthermore, they find it interesting to start from the possibilities of the audience itself rather than their needs. Skepticism is shown regarding the possibility of a single proposal being applicable to different museums (with varying sizes, types of staff, funding, etc.) when its objectives are generalizable. This suggests less focus on serving social needs and more on defining them.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of consensus on design of objectives.

The question about creative competences generates different opinions from the outset. In general terms, professionals readily accept the inclusion of the concept and five specific aspects of this competency: research, intuition, inspiration, imagination, and innovation. Academics are more reluctant to acknowledge that the relationship between creativity and personal or professional growth is mediated by the term competence. Possibly due to their background in pedagogy, which tends to adopt a critical stance toward the more competitive or productivity-focused dimension proposed by the competency-based learning paradigm.

The least favoured issue was the generalization of the program. A program for all art museums is not envisioned; instead, the focus is on developing a framework that is relevant to any museum.

3.2. Content

Regarding the content, the experts were asked to rate the accuracy of twelve possibilities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Consensus on content design.

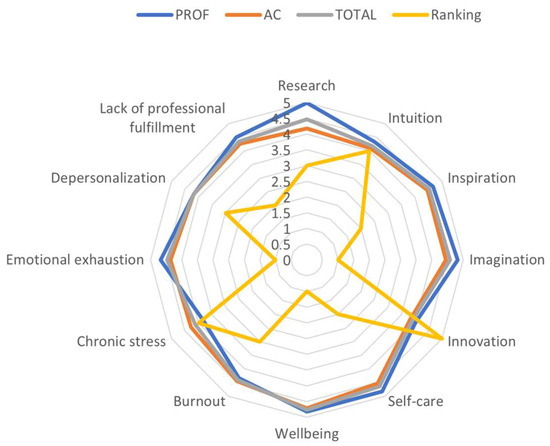

A subcategory of these concepts includes creative competences, which obtained the following order of relevance: imagination, inspiration, research, intuition, and innovation (Figure 2). The art museum serves as an ideal space for their development. Academics argue that these competences can be applied broadly in various aspects of life. While research is crucial, its necessity should be critically evaluated due to potential problems. Educators should rely on informed and thoughtful intuition. They argue that although inspiration is invaluable, it is very complex and difficult to predict and control. Innovation should be balanced with conservation, as the new is not always inherently better. Two professional experts propose experimenting with music and dance, in addition to visual arts for this objective accomplishment.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of consensus on content design.

Three experts emphasize the importance of activities that allow for reflection and argue that it is crucial that the facilitator promotes this through conversations and open questions. They proposed that beginning with preliminary explanations could help unlock participants’ creativity if this is an impediment to their adherence. This way, participants themselves could recognize their inherent creative capacity and their potential to develop it.

All experts seem to agree that art museums can address societal issues to connect meaningfully with their audiences. At the same time, they are aware that they are not standalone remedies for issues such as burnout. Content related to well-being and self-care is prioritized over burnout itself and chronic stress, with participants asserting their belief that self-care should not overburden individuals with systemic problems. Yet, they felt that raising awareness of burnout is fundamental for support. Among the symptoms of burnout, emotional exhaustion is considered the most significant in a program of these characteristics (Figure 2). When speaking openly on the programs about burnout, they agree that the person should not be stigmatized, as it is essential to understand that it is a common and temporary phase. All of these well-being-related concepts need more precision and they should not be understood solely in individualistic terms. Also, the program’s participants need to clarify whether the focus is on prevention or on supporting those already experiencing emotional exhaustion and related challenges.

3.3. Methodological Guidelines

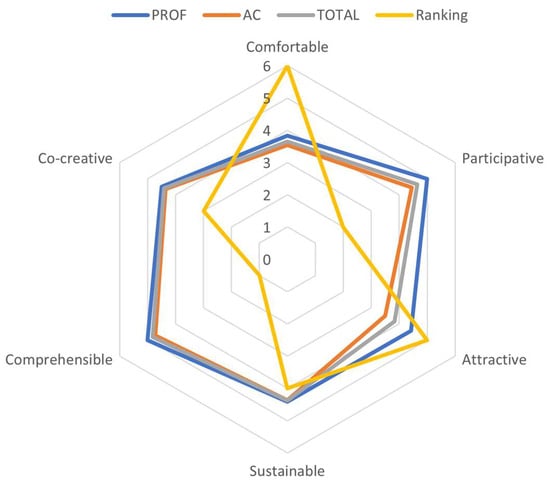

Regarding the methodological guidelines outlined, the three that are rated as the most relevant are comprehensible, participative and co-creative. Professionals placed the most value on the participative dimension of the possible art-based program, while academics thought that the co-creative dimension (Table 6) was the most valuable.

Table 6.

Consensus on methodological guidelines.

The least valued were comfort for professionals and attractiveness for academics (Figure 3). It remains to be defined what type of participation would be possible for each art museum. Some experts refer not only to the act of participating but also to the importance of receiving something. Comfort has not been a major concern for any of the groups, which can be attributed to the misconception they wanted to avoid that the arts can inherently provide this state of pleasure, since artistic expressions are not always pleasant and sometimes may evoke discomfort. Similarly, the attractiveness of the proposal needs to go beyond superficial considerations and the resultant low-level engagement. These methodological guidelines should not exclude the possibility of not fully comprehending the art. The goal should be to maintain hope rather than to seek inherent meaning. Academics believe that for a program to be both interesting and productive, it must challenge individuals beyond their comfort zones, without necessarily being uncomfortable.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of consensus on methodology design.

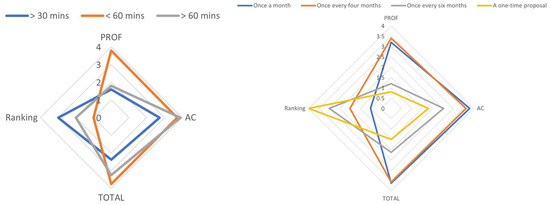

3.4. Scheduling

Regarding the art-based program schedule, academics find it more appropriate to implement it once a month whereas the most favored option among professionals (who usually work on-site where these proposals take place) is once every four months. The average scores indicate that the preferred option is once a month. Regarding the length of each session, there is consensus that programs of less than 60 min would be the most suitable (Table 7). Experts emphasize the importance of avoiding the pathologization of psychological factors when designing the program, recommending a minimum of 3 to 6 sessions to assess their impact.

Table 7.

Consensus on scheduling design.

Professionals agree that a proposal for a program has greater potential if multiple sessions are conducted. At the same time, they agree that conducting frequent activities may hinder participant recruitment and/or their effective attendance at all sessions. Academics do not find issue with the possibility of the one-time and significant proposal. Last, the scheduling of a proposed program, could be evaluated among facilitators and participants so that its design is participatory from the outset (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of consensus on scheduling design.

Regarding the use of time, half of the experts think that it is better to first provide an explanation followed by free activity time. One of them believes that reversing the process is better, and two think that it would not be necessary to follow a specific order as long as the time is organised well. Two experts believe it can be done either way, or vice versa, while two others felt that the sequence depends on the program objectives.

3.5. Facilitators

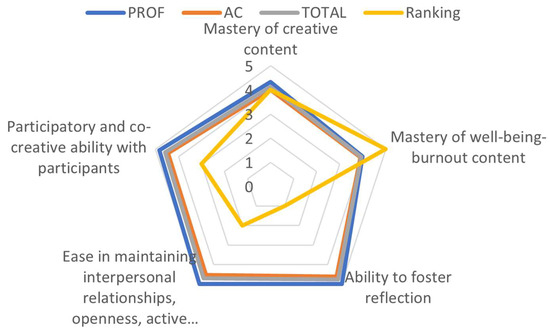

Regarding the competences of the workshop facilitators, the ability to foster reflection has been given the highest importance. This is directly related to the ability to foster interpersonal relationships based on openness and active listening. Thirdly, in connection with the participative methodological principle, the competence of being able to be open to collaborate with participants is also crucial for facilitators (Table 8).

Table 8.

Consensus on facilitators professional competences.

Although most experts believe that the facilitator’s ability to connect with people would have the most impact, some indicated that facilitators need to work with orientation, with attention to the situation, and with inventiveness; which goes beyond just possessing a list of competences This brings to light that there are issues within education that transcend technical boundaries. Thus, facilitators may be experts in well-being, arts, or educational methodologies, but the Delphi participants believe that there are also immeasurable qualities that enable the participant of an activity (in this case, the teacher) to connect with the person leading the activity, with themselves, or with the art itself (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of consensus on facilitators’ professional competences.

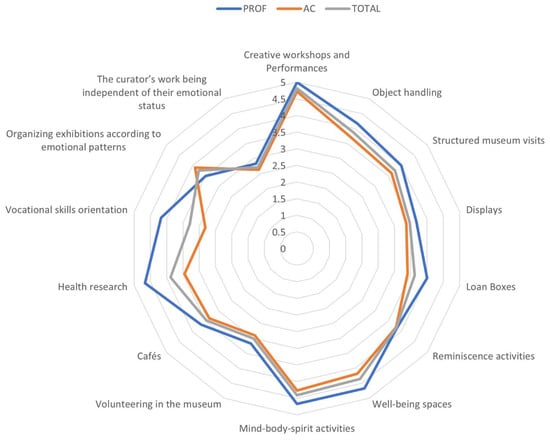

3.6. Activities

The activities of creative workshops and performances, mind–body–spirit activities, and well-being spaces have been the most highly valued for their potential impact on teacher well-being and burnout prevention (Table 9). Some experts, however, caution against mind–body–spirit activities and argue that art should be taken seriously and not merely seen as an excuse to address well-being. Well-being spaces, if viewed as places where one could simply stop by for a coffee or a snack, must be spaces where this sharing goes beyond merely capitalizing on rest, and they must have a design that fosters the connection between people and art (Figure 6).

Table 9.

Consensus on activities design.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of consensus on activities design.

A reflection that has emerged as controversial is how the work of other art museum professionals, such as curators, can facilitate art-based programs. It was agreed that integrating the curator’s work within the educational design is fundamental because educational and curatorial aspects cannot follow divergent paths. However, experts were reluctant to assign a score higher than 4 to the possibility of arranging artworks according to emotional patterns. Two reasons are suggested for this position: first, the risk of instrumentalizing the artwork, which could place a psychological agenda in the driving seat, and second, the concern that it would preclude other kinds of emotional responses in interpreting the artwork.

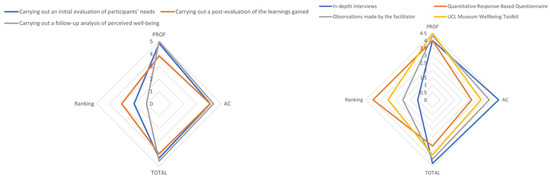

3.7. Evaluation

Conducting an evaluation of the perceived well-being benefits is not always straightforward. Among academics, the tool that has been most highly regarded is in-depth interviews, while among professionals, the use of the UCL Toolkit is preferred. Academics, however, are highly critical of the latter, citing the risk of psychologizing emotions and reducing them to a one-dimensional state. In terms of overall scores, in-depth interviews are the top choice, followed by observations made by the facilitator (Table 10). Regarding the latter, it is emphasized that sufficient time is not always available for in-depth interviews, and the value of observations lies in the subsequent conversations the facilitator has with the participants (Figure 7).

Table 10.

Consensus on evaluation design.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of consensus on evaluation design.

All experts agree that not everything received in an educational program can always be expressed in words. Having spaces where this is taken into account will lead to a view of the participant not as a subject of measurement but as a subject of possibility and hope.

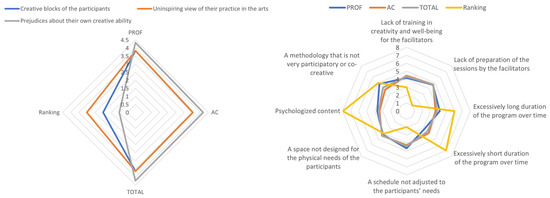

3.8. Adherence to the Program

The adherence of the teacher to the museum’s art-based program can be motivated by various factors. Experts have valued predictable elements that should be taken into account in advance, such as the lack of session preparation by the facilitators, a schedule not tailored to participant needs, and the lack of training in facilitators on creativity and well-being. The predictable element they see as having less impact on program adherence is psychologically oriented content (Table 11).

Table 11.

Consensus on elements for adherence to the program.

Regarding unforeseeable variables that may hinder program adherence, bias about one’s own creativity is the one that has been considered to have the greatest influence. Also, creative blocks are identified as aspects to consider that may hinder not only a good adherence to the program by the participants but also impede an openness to possibility, change, dialogue, or being affected by the artworks (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of consensus on elements for the adherence to the program.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study helped us understand that consensus should not always be pursued at all costs, but rather that one must learn to manage disagreement and understand why different perspectives on the same reality might exist. Likewise, it can be observed that the contributions made by the experts are driven by a genuine concern to offer new perspectives on the challenges that teachers face in fulfilling their tasks at schools. It was also found that if consensus exists, it does not necessarily imply that the correct answer, even through the convergence of opinions and judgements, has been found. For the professionals, their motivation arises because they have observed the effects of a burned-out teacher in practice or because they have seen the growth opportunities offered by spaces such as art museums. Similarly, for the academics, their motivation stems from participating in research guided by a pressing issue in education, namely the promotion of well-being among educators. In both cases, a genuine interest in participating and providing feedback on each element of the framework to be designed has not gone unnoticed.

As Hasson et al. (2000) state, there is no evidence of the reliability of applying the Delphi technique. By reliability, they mean that it is not clear that consistently repeating the same procedure and conditions will produce similar results. This is where the immeasurable value of creativity comes into play. This study aims to serve as a pedagogical framework for professionals working in art museums to refer to or consult when designing proposals for promoting teacher well-being and preventing burnout.

Yet, the Delphi method underscores the critical importance of aligning the pedagogical objectives of the art museum community’s needs while also prioritizing the promotion of teachers’ well-being. Of similar or even greater importance, the objectives must also align with their potential for learning, creation, and interaction. This highlights the pedagogical dimension to prevent burnout through art-based programs. Despite concerns about the applicability of a singular proposal across diverse museum institutions, establishing generalizable objectives appears promising in overcoming this challenge.

In a previous study conducted by the authors, primary school teachers were questioned about their perceptions of their own creative competences and their impact on their well-being. In contexts marked by inequality, professional fatigue, and cultural marginalization, strengthening teachers’ creative agency redounds in social justice as it enables educators to open classroom spaces for democratic participation. Creativity operates as a protective factor against burnout while becoming a driver of resilience within arts education. These teachers considered inspiration and innovation to be of great pedagogical value because of the emotional bonds these two competences facilitate to overcome professional difficulties. In this study, the agreed-upon content includes imagination, inspiration, research, well-being and self-care and emotional exhaustion. The creative competences emerge as a pivotal tool for personal and professional growth, though their integration faces some skepticism, particularly regarding how competences are generally understood. Beyond their individual benefit, the creative competences identified—imagination, inspiration, and research—can be considered as powerful tools of agency for teachers to resist systemic pressures and sustain inclusive pedagogical practices.

The descriptors understandable, participatory, and co-creative are highlighted as methodological guidelines. While the temporal scheduling of sessions remains contentious, there is consensus on the necessity of multiple sessions to optimise impact. This places further importance on reaching an agreement between museum educators and teachers participating in art-based programs regarding their duration. Moreover, this refers to the idea of starting from possibility instead of absence. In other words, the aesthetic experience is framed by what the person already possesses rather than by what they lack. This makes the approach to the proposals more positive and augments audience participation and adherence.

Regarding the activities, it is important to note that creative workshops and performances, mind–body–spirit activities, and well-being spaces are selected as the type of activities that could enhance a holistic or eudaimonic well-being for teachers as participants (as the study of Šveb Dragija et al., 2024).

The facilitator competences in fostering reflection and interpersonal relationships are identified as paramount, emphasizing the relational aspect of arts-based interventions such as their capacity to foster reflection and facilitate connection between participants. Therefore, activities such as performances, mind–body activities, and spaces dedicated to well-being are agreed as those that would best facilitate this type of methodology. In addition, it makes sense that the types of evaluation that would best fit, according to the experts, are in-depth interviews, observations, and subsequent conversations with participants about the valuable aspects of the experience. The role of museums in this framework also extends beyond individual well-being. Positioning teacher well-being within museum-based initiatives goes beyond professional care; it encompasses the creation of equitable opportunities for teachers to thrive and, in turn, to cultivate inclusive and culturally responsive learning environments for their students.

Finally, the assessment of program adherence speaks to the importance of addressing predictable factors such as session preparation and participant-tailored scheduling, while also recognizing unforeseeable obstacles like biases and creative blocks. The results emphasize the need for holistic approaches that not only prioritize well-being and creativity but also foster meaningful connections between the program participants and the artworks within the art museum.

The strengths of this study might be acknowledged by having first-hand insight into the opinions of a group of experts regarding a pedagogical area that has the potential for future growth. Similarly, another noteworthy strength has been the ability to maintain a 70% participation rate in the second round, with panellists expressing a high level of commitment to the study in their email correspondence, through their willingness to clarify responses, provide additional information if necessary, and most importantly, their interest in learning the final results of the research. The time-intensive and iterative nature of the snowballing technique recruitment process also highlights the researchers’ commitment to inclusivity and methodological rigour, turning one of the potential challenges of snowballing into a demonstration of persistence and transparency in expert selection.

The limitations of this study might be characterised by the absence of participants who do not hold a Western perspective. Although invitations were extended to potential experts from non-Western contexts, no responses were received, which further reflects the structural barriers to achieving a more global representation in Delphi studies. The selection of experts was therefore significantly influenced by the convenience of participation provided by the snowball sampling technique, as well as the expert recommendations identified through a previous literature review (Urpí et al., 2025).

Another limitation was not including a checkbox for responses such as DK (Don’t Know) in the first round, which was subsequently included in the second round. It is worth considering to what extent the same results would have been obtained if different experts had been consulted. The criterion of validity, in this case, has been guided by the assumption of safety in numbers (essentially, the idea that a group is less likely to make an incorrect decision). Accordingly, the validity of the results presented here relies on the response rates.

Future research aims to actively incorporate decolonial, Indigenous, or non-Western perspectives in order to broaden the validity of the framework and align more closely with global debates. It also might focus on studying why primary school teachers questioned in previous research would choose inspiration and innovation as creative competences content, while the experts participating in the Delphi would prioritize imagination and research for well-being promotion. This study therefore offers a theoretically grounded and expert-informed framework, rather than empirical data from teachers’ lived experiences, which will be explored in subsequent research phases.

Furthermore, it will be interesting to include within the art-based program content related to the personal freedom exercised during teaching and in relation to others. This could help teachers participating in the program to move from the realm of technique to living out their teaching task as a space for improvisation and creation. The development of this expressiveness will allow the development of a personal teaching style that can allow him/her to endure moments of vulnerability, fragility, depersonalization, or professional exhaustion. Additionally, a toolkit that could visually help museum educators or practitioners in the cultural field to design programs for teacher burnout prevention will be developed.

Lastly, it seems necessary to conduct a pilot test of the pedagogical framework within the art museum context with teachers as the main participants. The connection established between the researchers and the expert panellists during the Delphi rounds will serve to offer those working in the field the opportunity to work collaboratively with the authors in order to test the framework. In particular, previous collaborations between the School of Education and Psychology at the University of Navarra and the Museo Universidad de Navarra could be leveraged for the implementation of the first pilot test. The application of the framework in more than one museum will be necessary to verify the validity and generality of the elements that it consists of. Positive comments were also received from participating professionals regarding their willingness to test the framework in the museums where they work.

The conclusions of this study are firmly grounded in the Delphi results, which identified consensus across nine pedagogical guidelines—objectives, content, methodology, scheduling, facilitators, activities, evaluation, and program adherence. These findings substantiate the theoretical claim that creativity and wellbeing are interrelated constructs that can be fostered through participatory, co-creative, and reflective museum-based practices. Moreover, the experts’ perspectives directly support the argument that teacher wellbeing is not an individual matter but a social and pedagogical responsibility, aligning with frameworks of social justice and SDG 4. The proposed pedagogical framework thus emerges not from abstract theorization but from the empirical insights and professional wisdom shared by the expert panel, ensuring that the study’s conclusions are both evidence-based and practically applicable. This study tried to focus on the educational challenge of teacher well-being in order to raise awareness among academics and professionals in the educational field regarding the need for evidence-based programs for this matter.

5. Conclusions

- The study highlights that consensus is not always the ultimate goal in Delphi processes; rather, managing disagreement and embracing diverse perspectives, grounded in creativity, is crucial for designing effective pedagogical frameworks.

- Experts emphasized that creativity, imagination, and inspiration are key competences to strengthen teachers’ agency, resilience, and professional growth, positioning art museums as valuable partners in preventing burnout and promoting inclusive, well-being-oriented practices.

- The research contributes a pedagogical framework co-designed with experts, acknowledging both its strengths (expert commitment, interdisciplinary input) and limitations (Western-centered perspectives), while setting the basis for future pilot testing and broader applications in museum contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B. and C.U.; methodology, C.B. and C.U.; software, C.B.; validation, C.B.; formal analysis, C.B.; investigation, C.B. and C.U.; resources, C.B. and C.U.; data curation, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and C.U.; visualization, C.B.; supervision, C.U.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.B. acknowledges financial support from a predoctoral grant of the Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UNIVERSIDAD DE NAVARRA (protocol code 2022.182 Tesis approved on 3 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank all the experts who participated in the Delphi study for their valuable time, insights, and contributions. C.B. gratefully acknowledges the financial support received through a predoctoral grant from the Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra. The authors also wish to thank Herman Hubert Cloete Bergsteedt, from the Institute of Languages at the University of Navarra, for his careful review and corrections of the English language in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alavinia, P., & Pashazadeh, F. (2018). Probing teacher creativity in the light of motivation, self-efficacy and burnout. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies, 6(4), 58–68. Available online: https://eltsjournal.org/archive/value6%20issue4/8-6-4-18.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Anderson, R. C., Katz-Buonincontro, J., Livie, M., Land, J., Beard, N., Bousselot, T., & Schuhe, G. (2022). Reinvigorating the desire to teach: Teacher professional development for creativity, agency, stress reduction, and wellbeing. Frontiers in Education, 7, 848005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basanta, C. M., & Urpí, C. (2024). The art museum as a catalyst context for teacher well-being and burnout prevention: An international review of best practices. Journal of Health Care Education in Practice, 6(2), 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero, J. (2014). Formación del profesorado universitario en TIC. Aplicación del método Delphi para la selección de los contenidos formativos. Educación, 17(1), 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. H. (2022). The value of museums: Enhancing societal well-being. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J. H. (2025). Leaning into value: Becoming a user-focused museum. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review (Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report 67). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.-C. (2015). The burnout society. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICOM. (2022, August 24). Presentation of the proposal for a new definition of ‘museum’. Extraordinary General Assembly, Prague Congress Centre, Prague, Czech Republic. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EN_EGA2022_MuseumDefinition_WDoc_Final-2.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Iqbal, S., & Pipon-Young, L. (2009). The Delphi method. The Psychologist, 22(7), 598–601. [Google Scholar]

- Jünger, S., Payne, S. A., Brine, J., Radbruch, L., & Brearley, S. G. (2017). Guidance on conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 31(8), 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkou, V., & Glasman, J. (2004). Arts, education and society. The role of the arts in promoting the emotional wellbeing and social inclusion of young people. Support for Learning, 19(2), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L., Oepen, R., Bauer, K., Nottensteiner, A., Mergheim, K., Gruber, H., & Koch, S. C. (2018). Creative arts interventions for stress management and prevention—A systematic review. Behavioral Science, 8(2), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Piñeiro, E. (2003). La Técnica Delphi como estrategia de consulta a los implicados en la evaluación de programas. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 21(2), 449–463. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 19–32). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mosavarzadeh, M., & Ding, P. (2022). Hold me: Togetherness as an aesthetic experience. International Journal of Art & Design, 41(1), 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, R., Polley, M., Sabey, A., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2022). How arts, heritage and culture can support health and wellbeing through social prescribing. National Academy of Social Prescribing. Available online: https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/media/5xhnkfwh/how-arts-heritage-and-culture-can-support-health-and-wellbeing-through-social-prescribing.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Musaio, M. (2013). Pedagogía de lo bello. Eunsa. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, C. (2003). The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41(4), 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, G., & Wright, G. (1999). The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool. International Journal of Forecasting, 15(4), 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellman, E., & Cunliffe, A. (2012). Working with artists to promote mental health and wellbeing in schools: An evaluation of processes and outcomes at four schools. In T. Stickley (Ed.), Qualitative research in arts and mental health: Contexts, meanings and evidence (pp. 140–169). PCCS Books. [Google Scholar]

- Šveb Dragija, M., & Jelinčić, D. A. (2022). Can museums help visitors thrive? Review of studies on psychological wellbeing in museums. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šveb Dragija, M., van Zomeren, M., & Hansen, N. (2024). Designing museum experiences for eudaimonic or hedonic well-being: Insights from interviews with museum visitors. Museum Management and Curatorship, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TED. (2009, June 24). Ken Robinson says schools kill creativity [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iG9CE55wbtY (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Urpí, C., Basanta, C., & Musaio, M. (2025). Arts and creativity in the fostering of teacher well-being for burnout prevention: A scoping review (2010–2023). In Transforming Educational Research Realizing Equity and Social Justice Worldwide (Vol. 2025, pp. 116–139). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xipell-Font, P., Guillén-Parra, M., & Méndiz-Noguero, A. (2024). El sentido del trabajo en los docentes, y su relación con la implicación laboral y la intención de abandono. Estudios sobre Educación, 46, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Chen, J., Li, X., & Zhan, Y. (2024). A scope review of the teacher well-being research between 1968 and 2021. The Asia-Pacific Education Research, 33, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, C. C., Haba, C. C., Florit, M. E. F., Julián, B. F., & Denia, A. P. (2009). ¿Hacia dónde se dirige la función de calidad?: La visión de expertos en un estudio Delphi. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 18(2), 13–38. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).