Abstract

The relationship between intelligence and creativity has remained a focus of research for nearly 75 years. The primary objective of this study was to examine the current state of research on creativity in the context of giftedness and to identify prevailing trends. This study employed a bibliometric analysis of scholarly articles on the subject in English. The findings offer a comprehensive overview of the performance metrics, intellectual structure, and emerging trends within the literature on creativity in giftedness. Prominent journals, articles, institutions, countries, and authors were identified. Moreover, trends and network structures related to research topics were revealed. One of the most striking findings regarding the performance analysis of the studies was that the US is the most successful country in many areas such as citation frequency, institutional contributions, and author productivity. A significant insight from the trend analysis was the noticeable absence of technology-related topics such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, despite their growing relevance in educational research. That is why these areas are recommended for future investigation.

1. Introduction

The relationship between both variables has been a hot topic that has attracted the attention of scientists since the 1960s (for example, Solomon, 1967; Şahin, 2015a, 2022). The number of publications on the subject is increasing day by day. The definition of giftedness is a subject of ongoing debate, reflecting diverse viewpoints within the field (McBee & Makel, 2019). The lack of single, universally accepted definitions of creativity and giftedness is a common problem in the field. Both concepts have multi-layered and -faceted natures. This study evaluates both variables as cognitive features. The literature on creativity and intelligence consists of studies covering a wide range of topics focused on the cognitive skills constituting both structures, the limits and content of cognitive skills, and the capacity of cognitive skills, their evaluation, their developmental nature and their interaction with other cognitive abilities. In this study, in the first stage, certain main theories and models that consider the terms creativity and giftedness together such as Gagne’s (2005) Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT) will be discussed to gain an overview of the topic. Then, the subject will be examined within the scope of prominent empirical study examples.

1.1. Creativity and Intelligence: Theoretical Lens

Theoretically, the relationship between creativity and giftedness can emerge in four different ways. The complex relationship between creativity and intelligence is generally conceptualized through four fundamental positions in the literature. The first posits that creativity is a subcomponent of intelligence, suggesting that creative abilities are encompassed within the broader cognitive capacity of intelligence. Conversely, a second view argues that intelligence is a subcomponent of creativity, treating intelligence as a specific aspect of a more comprehensive creative process. The third hypothesis maintains that the two are independent constructs, demanding separate psychological and psychometric investigation. Finally, the fourth perspective offers a nuanced view, suggesting that intelligence and creativity share some features while differing in others; thus, while certain core mental skills may be shared, each set possesses unique, non-overlapping abilities. Within the scope of the fourth possibility, very different subset combinations can emerge depending on the features of the selected skills. It is implied that certain major theories in the literature aiming to explain the relationship between giftedness and/or creativity conceptualize the relationship between both variables within the scope of these theoretical possibilities.

In some theoretical studies, which can also be considered classical intelligence theories, creativity was considered to be a sub-component of intelligence. The emergence of this perspective was influenced by the pioneering views of Galton and Terman that creativity was a necessary skill for high-level intelligencee (Simonton, 2000). Spearman (1904), one of the early researchers, considered creative thinking skills to be a component of intelligence in his unidimensional theories of intelligence. Alfred Binet, who was highly influenced by Spearman, used tasks involving divergent thinking tasks closely related to creative thinking (Runco, 2007) in his early studies on measuring intelligence. This perspective was also followed in subsequent multiple-dimensional theories of intelligence. In his study, called Structure of the Intelligence, Guilford (1967) initially defined divergent production as consisting of four thinking sub-skills. They consisted of fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration. Contemporary researchers prefer the more explicit term “divergent thinking” to explain what they mean by divergent production (Kaufman et al., 2011).

In addition to that, pioneering researchers Horn and Cattell (1966) discussed the concepts of creativity and intelligence without separating them. The researchers discussed cognitive skills under two different types of intelligence called crystallized intelligence (gC) and fluid intelligence (gF). In this intelligence model, skills such as general fluency (S), ideational fluency (Fa), word fluency (Fw), associational fluency (Fi), figural adaptive flexibility (DFT), and flexibility of closure (Cf), which may be related to creative thinking, were considered as sub-skills forming gF and gC. Cattell–Horn’s gC and gF theory and Carroll’s (1993) three-stratum theory were later combined and named the Cattell–Horn–Carroll (CHC) theory (K. H. Kim et al., 2010). Through this theoretical lens, “Long term storage and retrieval skills” under stratum II include some skills, such as ideational fluency, associated fluency, originality, expressional fluency, word fluency, and figural fluency/flexibility, related to creativity thinking.

Creative thinking has also been included in theories developed towards the end of the 20th century that focus on explaining giftedness. For instance, in Gagne’s (2005) DMGT, creativity is one of the natural capacities that is effective in the emergence of giftedness. In the Munich Model of Giftedness, creative abilities are one of the seven predictors that are effective in the transformation of talent factors into performance (Heller et al., 2005). In addition, in his Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Gardner (1983) conceptualizes creativity as a high-level function within these various intelligence.

According to the Investment Theory, which was put forward by Sternberg and Lubart (1991), intelligence is considered a subcomponent of creativity. In this theory, intelligence is considered as one of the characteristics, such as thinking style, personal characteristics, motivation, and environment, that play a role in the emergence of creativity. In the following theoretical perspectives, creativity ability and its independence from other abilities are described more clearly. In Thurstone’s (1938) Multiple Factor Theory, creative thinking skill is defined as one of the seven independent abilities in the theory. In the sub-ability area called “Word fluency”, the researcher gives test takers the task of creating as many words as possible related to a given letter. In Sternberg’s (1984, 2005) Triarchic Theory of Intelligence, creativity is identified as a distinct type of intelligence, namely “creative intelligence”. In Renzulli’s Tree Ring Conception, creativity is one of the three rings (factors) that constitute giftedness (Renzulli, 2005).

1.2. Creativity and Intelligence: Empirical Evidence

Horn and Blankson (2016) state that what is known about cognitive skills emerges based on structural and/or developmental research results. One of the perspectives that attempts to explain the relationship between intelligence and creativity is the threshold effect. Accordingly, it is assumed that there is a relationship between both variables. However, the correlation is not linear across different levels of intelligence (Jauk et al., 2013). The strongest relationships between both variables are expected to occur around an IQ of 120. As IQ score increases (120>), the relationship between both variables loses its significance. In the literature, it is possible to find studies supporting this theory (Cho et al., 2010; Getzels & Jackson, 1962; Fuchs-Beauchamp et al., 1993; Şahin, 2014b), as well as other studies objecting to it (K. H. Kim, 2005; Runco & Albert, 1986; Runco et al., 2010; Preckel et al., 2006; Sligh et al., 2005). In other words, it can be said that there is a non-linear relationship between the two variables.

In studies examining the relationship between two variables without taking the threshold effect into account, contradictory results were reached. In a group of studies, significant relationships were found between both variables. For example, Silvia (2008) re-analyzed the data that Wallach and Kogan used in 1965. According to the original data, a small and significant relationship was reported, but the re-analyzed data revealed that creativity scores significantly predicted a latent intelligence factor. Plucker (2010) re-analyzed Torrance’s data (between 1958 and 2010; participant average IQ score, 121) and he found that divergent thinking scores include originality, fluency, flexibility, and elaboration predicted intelligence scores. There are also studies that did not find significant relationships between both variables. For example, Richmond (1966) did not find a significant relationship between intelligence and creativity scores in students with monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Moreover, Solomon’s (1967) and Furnham and Bachtiar’s (2008) studies have parallel results with Richmond’s (1966), as they also did not find a correlation between intelligence and creativity. A group of studies examined the relationship between intelligence and creativity according to intelligence score types. For example, Batey et al. (2010) found that gF and creativity index scores were positively and significantly related, but creativity index scores and gC were not significantly related. Moreover, Batey et al. (2009) found that DT fluency was significantly and positively related to gF and to general IQ.

The relationship has also been explored using factor analysis. In this context, the literature search yielded only two studies addressing this specific methodological line of inquiry. Wallbrown and Huelsman (1975) examined the construct validity of creativity scores measured with the Wallach–Kogan creativity test and intelligence test scores measured with the WISC test using hierarchical factor analysis. Şahin (2015a) tested the distribution of TTCT (fluency, originality, and elaboration) and WISC scores (information, similarities, arithmetic, vocabulary, comprehension, picture completion, picture arrangement, block design, object assembly, and coding) using confirmatory factor analysis for construct validity. The analytical results in both studies revealed that scores related to both variables were clustered under separate constructs. In other words, significantly, both studies indicated that creativity and intelligence are independent constructs (factors).

There is also a wide range of studies in the literature examining socio-demographic (age, gender, family, etc.), biological (medical records, birth order, etc.), and behavioral (educational interventions, diagnosis, etc.) variables that affect the creativity of gifted students. To illustrate, in an intervention study using an experimental design in which the effect of mentoring strategy on the development of creative thinking skills in gifted students was examined in comparison with normal students, it was determined that the creativity scores of both groups with mentors differed significantly. The scores of gifted students with mentors were significantly higher than their peers with mentors (Şahin, 2014a). In another qualitative study, it was reported that mentoring-supported classroom adaptations supported the creative thinking skills of gifted students (Şahin, 2015b). Another example study on the subject can be given by K. H. Kim et al. (2010). The researchers determined that an inquiry-based instructional approach had direct, indirect, and total effects on student’s creativity.

1.3. Problem Statement

Since Guilford’s famous speech at the American Psychological Association in 1950, in which he defined divergent and convergent thinking skills, studies in the field of creativity have expanded and gained momentum. Creativity, which continues to attract the attention of many disciplines for different reasons, was found to already have 101 different generally accepted definitions in the literature by the end of the 20th century (Aleinikov et al., 2000). This diversity of concepts is equally true for the term giftedness. No single generally accepted definition has been reached in the literature for either concept (Sak, 2009). In this study, the article was structured considering that both concepts can be defined as cognitive features.

Almost 75 years after Guilford’s seminal speech (15 May 2025) in which thinking skills were first categorized into divergent and convergent thinking, a search with the keywords creative and gifted yielded 97,405 and 39,233 results in all fields on the Web of Science, and 1,200,000 and 366,000,000 results on the Google search engine. The general search results indicate that there may be extensive studies on the subject. It has been seen that contradictory results have been reached in the studies on creativity and intelligence, which are discussed under two subheadings in the Introduction. However, it can be argued that we have limited information about past and current trends in creativity research in which gifted people are the subject of the study. The most cited studies on the subject, their researchers, institutions, countries, and past and current dynamics of the examined subjects have not been examined holistically. Furthermore, considering that creativity in giftedness research has been a hot topic since the 1960s, there is a need to determine the scope of studies on this subject and the trends and research areas related to the subject. There is an ongoing discussion about whether these concepts have been exhaustively studied or if significant conceptual gaps persist, necessitating further research. Based on this need, to fill these gaps in the literature, the researcher examined publications on creativity in gifted individuals using the bibliometric analysis technique.

Recent review studies reveal that publications about giftedness have increased significantly (Baccassino & Pinnelli, 2023; Şakar & Tan, 2025). Bibliometric analysis, which is a kind of quantitative analysis by nature, allows for the easy classification and analysis of many publications according to specific parameters. It can evaluate the status and impact of scientific research on the topics examined (Ellegaard & Wallin, 2015) and help to determine the topics that need to be researched (Donthu et al., 2021). Bibliometric analysis allows for an analytical review of the literature on a topic. Interest in this method has increased with the development of software such as R 4.4.2 version, which allows researchers to work with big data, or interface programs such as VOSviewer or Biblioshiny, which help to scientifically map large amounts of data in databases such as Web of Science with low effort. Bibliometric analysis can be used for purposes such as determining the performance of articles, journals, institutions, and countries, revealing trends in research components and revealing the intellectual structure of a specified field in the literature (Donthu et al., 2021).

Upon reviewing the records of journals with a rigorous peer-review system, a limited number of studies involving gifted students were examined using the bibliometric analysis technique. These studies were prepared with the aim of determining the current status of and trends in research in the field of gifted education (Hernández-Torrano & Kuzhabekova, 2020), investigating the impact of data obtained from four field journals on other research areas (Hodges et al., 2021), analyzing the main trends in publications on the underachievement of gifted students (Cornejo-Araya et al., 2021), determining the current status of and findings in studies on mathematical giftedness (Özdemir et al., 2024), and examining the scope and impact of academic research in the field of gifted education in Australia (Jolly et al., 2024). This study will contribute a general perspective on research conducted on creativity in gifted students. The general aim of this article is to present the status of, and investigate main trends in, studies on creativity in gifted students. In this regard, the following questions were asked in this study:

- What are the key articles, journals, citations, countries, and institutions in creativity in giftedness research?

- What key topics were investigated in the literature from 1976 to 2025?

2. Methods

The term bibliometrics was first introduced by Otlet in 1934 (Rousseau, 2014). Bibliometric analysis (also known as bibliometrics) is used to refer to the application of mathematical and statistical methods to distinguish patterns in bibliographic data to provide useful information about documents, especially publications, citations, and authorship (Pritchard, 1969). The assessment is carried out to examine the literature according to predetermined criteria and to reveal research patterns that constitute the literature (Donthu et al., 2021; Lim & Kumar, 2024). In this study, the performance of articles on the subject of creativity in giftedness is evaluated, the general picture of collaborations between authors, institutions, and countries is determined, and trends on the subject are revealed.

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

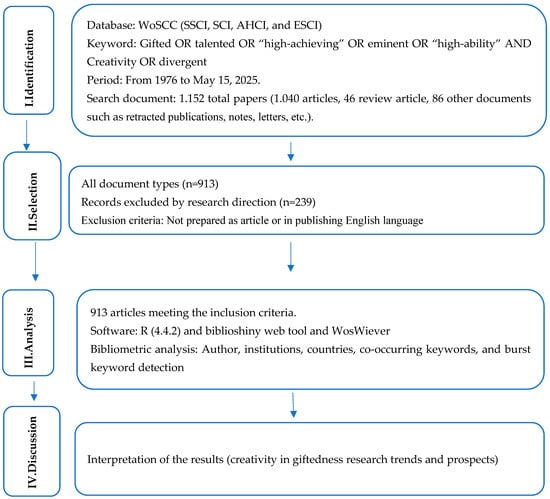

This research was conducted with studies included in the Web of Science’s (WoS) SSCI, SCI, AHCI, and ESCI collections. Data was collected on 15 May 2025. No date restrictions were imposed in this study, and accessible studies were included in this study (from 1976 to 2025). In the research, searches were conducted in two different groups with the following keywords: (i) Creativity OR divergent, and (ii) gifted OR talented OR “high-achieving” OR eminent OR “high-ability”. The term “And” was added between the data in both groups in the search and the searches were conducted in the “Topic” section. Five basic criteria were determined as inclusion criteria in this study: (i) archived in WoS SSCI, SCI, AHCI, or ESCI collections, (ii) related to gifted individuals, (iii) related to the subject of creativity, (iv) published as an article, and (v) prepared in English. Exclusion criteria were identified as a source type such as book chapters, editorial materials, proceeding papers, early access papers, retracted publications, meeting abstracts, book reviews, and notes or publishing languages that did not include the English language. In the identification phase, after scanning the data in the first phase, the publications were listed in an Excel file (n = 1152). In the selection phase, according to the exclusion criteria, only peer-reviewed journal articles written in English were retained for final review; all other publication types and languages were eliminated (n = 913).

2.2. Data Analysis Tools

In preparation for the analyses, a data file containing the information in WoS was prepared to perform bibliometric analyses in R and VOSviewer programs. While preparing the file, the articles that met the inclusion criteria of the study were exported as “Plan Text file” by selecting the “Full record and cited references” option. Data analysis was performed using the open-source R-based (Version: 4.4.2) bibliometrix tool (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017), the biblioshiny web user interface (Moral-Muñoz et al., 2020), and VOSviewer software. A scientific mapping technique was used to create answers to research questions. Scientific mapping is a powerful method for analyzing documents by visualizing them. Bibliometric analysis is one of the tools for performing this method (Kuzhabekova et al., 2015).

2.3. Data Analysis

The following evaluations were made within the scope of the first research question by examining the values of (i) annual publication frequency, (ii) mean total citations per article (MTCA), (iii) mean total citations per year (MTCY), (iv) most local cited authors (MLCA), (v) article fractionalized ratio (AFR), (vi) most relevant countries and affiliations, (vii) average article citations, and (viii) corresponding author (single-country publication [SCP] or multiple-country publication [MCP]). Within the scope of the first research question, the current status of citations to journals was evaluated through (i) global citations (GCs), (ii) local citations (LCs), (iii) normalized local citations (NLCs), and (iv) normalized global citations (NGCs).

To address the second research question, the dynamics of keywords were thoroughly investigated using advanced techniques, which included word tree analysis, word cloud analysis, hot topic analysis, keyword thematic analysis, and keyword network analysis. In all keyword analyses performed within the scope of the second research question, the author’s keywords were preferred. In the thematic analysis, to keep the selectivity high in transitions between themes, the minimum cluster frequency (per thousand docs) was determined as 10 and the number of words as 250. InfoMap was preferentially used in the clustering algorithm. “Keyword network analysis” was performed using the VOSviever program, setting the minimum number of occurrences of a keyword to 5 parameters. In this context, 56 of the total 2587 keywords were included in the analyses in this study. Keyword occurrence ranged from 5 to 260; total link strength ranged from 3 to 316. A total of 7 clusters were determined for 56 keywords that met these conditions. The stages of this study are given below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the research from identification to discussion phases.

3. Results and Discussion

Figure 1 illustrates the literature screening process and research framework. When the general situation regarding publications examining creativity in gifted individuals was examined, the annual growth rate between 1976 and 2025 was determined as 6.4%. The average citation per document was 19.27. A total of 38,503 references were used in the publications, and the publications were prepared with the contribution of a total of 1928 authors, 323 of whom were single authors. The international co-author ratio was 14.59%.

3.1. Performance Analysis

3.1.1. Analysis of Publication and Citation Status

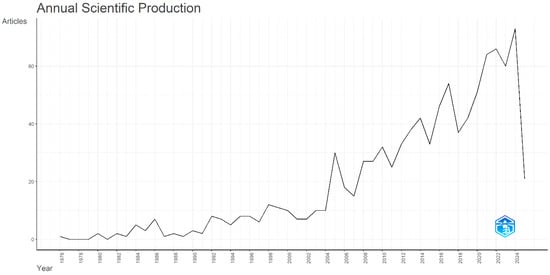

The analyses were conducted on 913 studies that met the inclusion criteria. When the frequency of publications was examined on a yearly basis, the highest number of articles was published in 2024 (n = 73, 7.50%) (Figure 2). This was followed by 66 (6.78%) in 2022, 64 (6.58%) in 2021, 60 (6.17%) in 2023, 54 (5.55%) in 2017, 51 (5.24%) in 2020, 46 (4.73%) in 2016, 42 (4.32%) in 2014 and 2019, and 38 (3.91%) in 2013. Although there were fluctuations in the number of studies published on an annual basis, the general trend was to increase. A total of 513 of the publications (51.18%) were published in 2014 or later. This data can be interpreted as demonstrating that creativity continues to be one of the hot topics in giftedness research. The observed downward trend for 2025 was likely due to the timing of this study (15 May). A significant number of publications intended for the latter half of this year have likely not yet been released and, consequently, are not reflected in the graph.

Figure 2.

Annual scientific production (1976–2025).

In this study, the top five MTCA, MTCY, and MLCA values were also calculated. According to the MTCA values, the highest citation rate was 84.10 in 2003. This was followed by 69.00 in 1985, 67.00 in 1988, 65.89 in 2006, and 62.40 in 1994. Also, according to the MTCY values, the highest citation rate was determined as 3.66 in 2003. This was followed by 3.58 in 2009, 3.29 in 2006, 2.73 in 2011, and 2.20 in 2007. When the MLCA rate was examined, Lubinski D.’s study had been cited at the highest level with 149 citations. It was followed by Benbow C. P. with 142, Runco M. A. with 81, Kaufman J. C. with 71, and Park G. with 61 citations. To determine the top 5 researchers who made the most influential and significant contributions to the field of creativity in giftedness, the “Most relevant authors” and AFR parameters were examined. In this context, in the examination made according to article numbers, Runco M. A. ranked first with 22/13.60 (article number/AFR). In other words, Runco M. A. was the researcher who had published the most about creativity in giftedness and had the highest AFR. Runco was followed by Lubinski D. with 15/5.53, Sternberg R. J. with 14/12.17, Kaufman J. C. with 13/5.37, and Benbow C. P. with 13/4.03.

3.1.2. Analysis of Institutions and Countries

It was determined that the publications were prepared by employees of 928 different institutions. Among the institutions with the most publications, the University of California (32, 3.45%) was in first place. It was followed by Yale University (23, 2.48%), California State University and North Texas University (21, 2.26%), Ohio University and Vanderbilt University (20, 2.16%), the University of Georgia (17, 1.83%), and the University of Connecticut and the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (16, 1.72%).

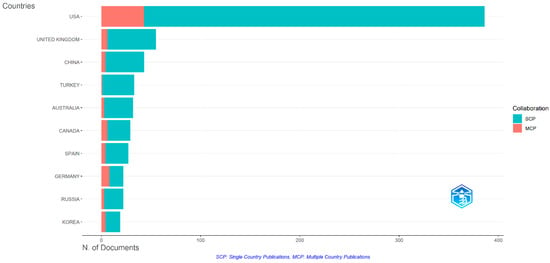

Country performances were examined according to the number of citations (total citations/average article citations per year) in publications related to the subject. The USA (11.477, 29.70) ranked first. In other words, it can be argued that the most effective country in this regard was the USA. This was followed by the UK (1045, 19.00), Canada (858, 29.60), Germany (601, 27.30), China (525, 12.20), Israel (359, 22.40), Australia (349, 10.90), Ukraine (261, 23.70), Spain (233, 8.60), and Türkiye (229, 6.90), respectively. The corresponding authors’ distribution was also calculated within the scope of country performances (Figure 3). The distribution of corresponding authors by country statistics were analyzed within the scope of SCP, MCP, total publications, which were the sum of SCP and MCP, and the ratio obtained by dividing the number of total publications by MCP. Countries are listed according to their total article number ranking. The USA is in the first place (accordingly, its number of total articles is 386; the ratio of the USA’s articles to the total article number is 39.70%; its SCP number is 343, its MCP number is 43, and the total article number/MCP ratio is 11.1%). This is followed by the UK (55 and 5.7%; 49 and 6; 10.09%), China (43 and 4.4%; 39 and 4; 9.3%), Türkiye (33 and 3.4%; 32 and 1; 3.0%), Australia (32 and 3.3%; 29 and 3; 9.4%), Canada (29 and 3.0%; 23 and 6; 20.7%), Spain (27 and 2.8%; 23 and 6; 20.7%), Germany (22 and 2.3%; 14 and 8; 36.4%), Russia (22 and 2.3%; 19 and 3; 13.6%), and Korea (19 and 2.0%; 15 and 5; 21.1%).

Figure 3.

Corresponding author’s countries (SCP: Single-country publication, MCP: Multiple-country publication).

Countries are expected to use their human resources, infrastructure, etc., at an optimum level to conduct scientific studies. Wuchty et al. (2007) states that working groups can generally publish more effective research compared to individual studies and that collaborations between different countries, institutions, and authors are an important tool in reflecting scientific sharing. The MCP ratio is one of the parameters used to measure the wide reach and more effective use of knowledge produced by enabling different cultural and academic perspectives to be used together. While the USA ranks first according to the SCP rate (39.7%), Germany ranks first according to the MCP rate (36.4%). It can be interpreted that Germany has the potential to produce relatively more effective studies compared to other countries. Although it ranks fourth according to the total article rate, Türkiye has the lowest MCP rate. This data can be interpreted as indicating that scientists in Türkiye should make more efforts to establish collaborations with researchers from other countries (3.0%).

3.1.3. Analysis of Journals and Their Citations

Journal analysis can help find the main journals and articles in this field (Brookes, 1969; Desai et al., 2018). The analysis found that 529 journals published research on creativity in the gifted. Gifted Child Quarterly was the most relevant journal (n = 53, 10.02%). This was followed by Roeper Review (n = 51, 9.64%), Creativity Research Journal (n = 28, 5.29%), Thinking Skills and Creativity (n = 22, 4.16%), and High Ability Studies (n = 21, 3.97%). To provide a general perspective on journals and to determine the articles that contributed to the literature at the highest level, the top 10 articles according to local citation level were also determined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Publications by citation status.

The article with the highest LC value of the studies in Table 1 was published by Subotnik et al. (2011) in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest. In this study, an evaluation of the current situation in the education of gifted children was made; suggestions were developed regarding intelligence development, talent development, public opportunities, psychosocial variables, and educational goals. The LC value of the study in question was determined as 45, while GC was 560, NGC was 13.67, and NLC was 15.85. On the other hand, NGCs are considered a stronger parameter to predict the impact level of a researcher, as it can provide a fairer evaluation of the citation performance of an article compared to other articles published in a certain year and field (Haunschild & Bornmann, 2024). Kaufman and Beghetto’s (2009) study, titled “Beyond big and little: the Four C Model of creativity”, was the study with the highest NGC, GC, and NLC values. In this study, it is emphasized that creativity can be discussed according to a model called Four C in which it is evaluated at four innovative levels (LC, 29; GC, 1146; NGC, 18.81; NLC, 15.98).

3.2. Current Situation and Trend Analysis

3.2.1. Word Tree Analysis

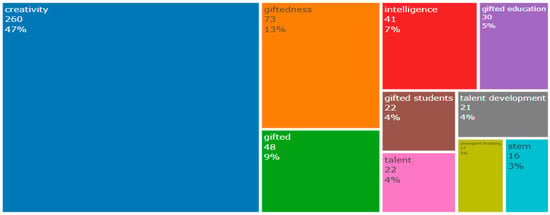

Word trees are used as an analysis technique based on graphing the frequency and percentage of keywords used in articles (Keathley-Herring et al., 2016). Our word tree was limited to the top 10 most frequent keywords. The most frequently used keyword was creativity (n = 260, 47%). This was followed by giftedness (n = 73, 13%), gifted (n = 48, 9%), intelligence (n = 41, 7%), gifted students and talent (n = 22, 4%), gifted education (n = 30, 5%), talent development (n = 21, 4%), divergent thinking (n = 17, 3%), and STEM (n = 16, 3%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Word tree.

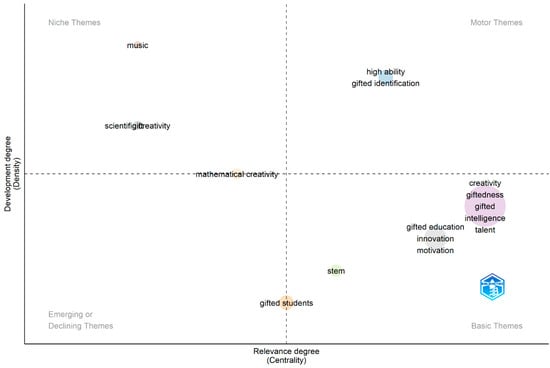

3.2.2. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted to reveal the current status of studies on creativity in giftedness and to determine the general picture of developmental trends. The network clusters that emerged in the thematic mapping analysis of the keywords used in the studies can be interpreted based on the position of the bubbles in the graph, their density, and the keywords that come together (Callon et al., 1991). When the graph is evaluated cross-sectionally, movement to the upper right indicates an increasing trend, while a decreasing path to the lower left indicates a decreasing trend. In addition, the X-axis shows the network cluster centrality or the degree of interaction with other graphic clusters and indicates the importance of a study theme. The Y-axis represents density, which is a measure of the internal strength of a cluster network and the growth of the theme (Cobo et al., 2015).

When the thematic analysis that emerged in this study was interpreted according to the explanations of Callon et al. (1991) and Cobo et al. (2015), “high ability”, and “gifted identification” attract attention as keywords in motor themes (upper right corner). This theme represents areas where a certain topic or area is widely discussed and examined in depth (Cobo et al., 2015). The cluster network has medium centrality and density, which indicates that the themes are developing and are among topics that are intensively studied.

The keyword groups “music” and “scientific creativity” are among the niche themes (upper left corner), while “mathematical creativity” is among the niche and emerging or declining themes (lower left corner). The topics under niche themes are more isolated and specific topics (Cobo et al., 2015). The clusters are far from each other, which means they can be interpreted as three different theme groups with limited relevance. The topics represented by the music and scientific creativity keywords indicate a rising trend, while “mathematical creativity” indicates a relatively low trend. The bubble size of the clusters formed by the keywords in the three clusters is small. This situation can be interpreted as the keywords in this cluster being topics studied at a lower level compared to the “creativity, giftedness, gifted, intelligence, and talent” keyword cluster. On the other hand, the “mathematical creativity” and “gifted students” clusters are topics that are more open to interaction with studies in other fields. In other words, the topics represented by these word groups stem mostly from interdisciplinary studies.

Emerging or declining themes are topics that have not yet fully developed or have lost their importance over time (Cobo et al., 2015). In the literature, no clear topic emerged under this theme. Accordingly, one of the reasons for this may be that the topic has been studied almost since the 1960s. The keyword groups “creativity, …”, “gifted education, innovation, and motivation”, and “STEM” are among the basic themes (lower right corner). These themes represent core topics. The keywords in “creativity …” have high centrality and relatively high density (large bubble). The keywords “gifted education, innovation, and motivation” and “STEM” have relatively higher centrality but low density. In other words, they can be interpreted as relatively underdeveloped topics (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Thematic analysis.

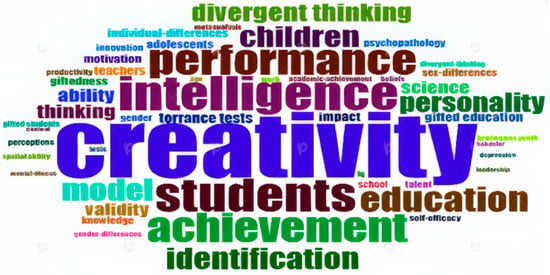

3.2.3. Word Cloud Analysis

Word cloud is used as a technique that visualizes word frequency. According to this analysis, the frequency of use of a term is directly proportional to the image size and its central position (Atenstaedt, 2012). In addition, smaller words indicate potential study directions (Mulay et al., 2020). In other words, font size is positively correlated with the frequency of the word. According to Figure 6, when the first 10 most frequently used keywords were examined, creativity ranked first. This was followed by intelligence, student, performance, achievement, education, model, children, identification, and personality. When the analysis results were interpreted according to Atenstaedt (2012), it can be stated that topics such as spatial abilities, talent, and gifted students were among the potential study directions.

Figure 6.

Keyword cloud analysis.

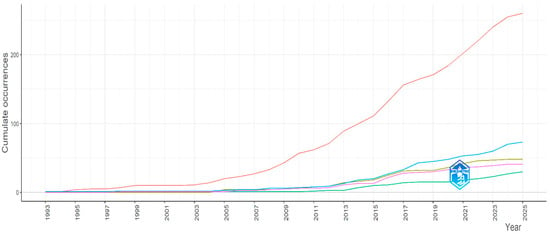

3.2.4. Word Hot Topic Analysis

Word hot topic analysis displays changes in keywords over time as a line graph and is a technique that helps explain the change in a topic under study over time. The graph, which reflects the change in the frequency of use of the keyword under study over a certain period, helps researchers select appropriate words for literature review and decide on a new research topic (Alkhammash, 2023). In this study, this analysis was limited to the first five most frequently used author’s keywords to keep the visual selectivity high. According to Figure 7, it can be seen that creativity became increasingly differentiated from other topics (gifted, gifted education, giftedness, and students) and became a relatively more commonly studied topic after 2005. One of the reasons for this is that creativity is an indispensable component of certain gifted programs (e.g., school-wide enrichment model, Purdue three-stage enrichment model, etc.) which stands out in the literature (Şahin, 2022). In addition, while giftedness is a subject on which discipline-specific studies are carried out, creativity is also a priority in interdisciplinary studies such as STEM studies (Altan & Tan, 2020). For these reasons, more studies may have been conducted on creative thinking in recent years.

Figure 7.

The most frequent words in research titles (red: creative, yellow: gifted, green: gifted education, blue: giftedness, pink: students).

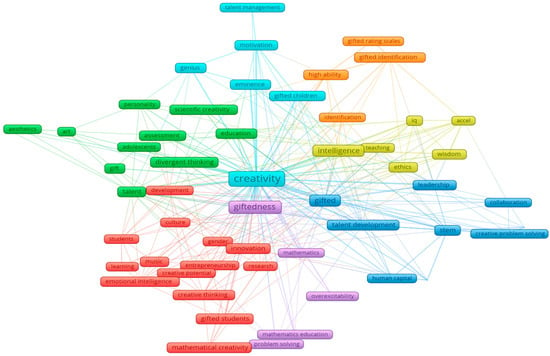

3.2.5. Keyword Network Analysis

Keyword analysis studies reveal hot topics. In this analysis, the keyword(s) that are associated are assumed to be connected. A clustering formation, along with a set of keywords, forms a network structure that represents the conceptual structure of a scientific field (Choi et al., 2011). The importance attributed to a term is directly proportional to node, density, diameter average, and centrality (Atenstaedt, 2012). When viewed through this lens, it can be concluded that creativity is a prioritized term (occurrence value: 260). It is followed by giftedness (72), gifted (48), and intelligence (41) at a lower level. According to Mulay et al. (2020), keywords that are written in smaller letters and are further from the center reflect potential study directions. For example, creativity and problem-solving or giftedness and art can be considered as related topics and potential study areas. There may be direct relationships between terms at the center and the periphery, or an indirect effect may occur through another term acting as a bridge (Choi et al., 2011). That is, while there is a direct relationship between creativity and collaboration, it also acts as a bridge in the relationship between creativity and creative problem-solving (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Creativity in giftedness keyword network analysis.

4. Conclusions

This study was conducted to reveal the status of studies on creativity in giftedness, to determine general trends, and to help predict possible new research topics. This study provided comprehensive insights into the intellectual structure of the existing literature on creativity in giftedness. In this context, prominent journals, articles, countries, authors, institutions, and researchers in the literature were identified, and trends in the literature were revealed. The analysis included 913 studies published between 1976 and 2025.

Perhaps the most striking results in the analyses emerged based on the literature performance analysis. The findings revealed that there has been a significant increase in the number of publications on this subject, especially in the last 10 years (513, 51.18%), with the highest number of publications occurring in 2024 (66, 6.78%). Another significant result regarding the performance analysis emerged in terms of author, institution, country, citation, and publication data. According to values related to the performance of institutions and countries, the five most relevant authors, nine of the top ten institutions with the most publications, and two of the five the most relevant journals were from the USA. In addition, the country with the highest values in terms of citation, publication, and corresponding author numbers was the USA. These indicators reflect the striking success of the USA on this subject. The reasons for this may be that the USA has a long history of studies on the subject (Hernández-Torrano & Kuzhabekova, 2020) and that gifted education is perceived as elitist in some countries (Subotnik et al., 2011). Another reason may be the financial support mechanisms that provide extrinsic motivation for scientific studies (Amabile, 1996). In this context, it can be seen that an annual budget of USD 13.2 million was allocated to the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Program in the USA between 2015 and 2024 (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). When this amount is considered together with other resources such as local funds, sponsorships, and in-kind aid, it is highly probable that a budget higher than this figure was used for research on giftedness in the USA. Therefore, the USA’s success in more than one area (citations, publications, etc.) can be interpreted as an expected situation.

One of the most eye-catching results in the status and trend analyses in this study is that the keyword creativity is a relatively more frequently studied topic than others. After the 2010s, creativity started to become a more studied topic compared to other topics in the field of giftedness. These findings are a significant result in the sense that they show that interest in the subject has been alive since Guilford’s (1966) speech at the American Psychological Association, when creativity was defined within the scope of a cognitive feature. Other trend analysis results (word tree, word cloud, etc.) support this, since creativity appears as a primary and central topic. These findings are parallel to the results of a study in which topics and trends in the gifted education literature were examined with a structural model (Şakar & Tan, 2025). Additionally, creativity theories developed based on empirical knowledge accumulated since 2000, such as the Minimal Creativity Ability Theory (Stevenson et al., 2021) and the 5A Creativity Framework (Glăveanu, 2013), can be considered another compelling piece of evidence, albeit indirect, demonstrating the development of the field. Currently, creativity is one of the top research topics in the field of gifted education.

Another salient result of this study is that seven clusters that are relatively different from each other emerged because of the network analysis. Accordingly, this situation is a reflection of the scatteredness as well as the richness of the literature and the need for interdisciplinary work.

5. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

This study was conducted on a trending topic in the literature. Specifically, it represents the first systematic investigation designed to offer a comprehensive insight into the performance and trends of prior research in this domain. Furthermore, the bibliometric analysis revealed an increase in research volume, hot topics, key trends, actors, and clusters. The obtained results will support predictions of research gaps and decisions on future research topics and identify powerful actors in future collaborations.

In this study, noteworthy results and findings were obtained from the analyses. When interpreting these findings and results, it is necessary to keep in mind the limitations arising from the nature of bibliometric analyses. In bibliometric analyses, the values of prominent studies are calculated based on factors such as displayed citations or references. However, this approach may not always produce completely accurate results in every study. Current studies that receive fewer citations may lose relative value depending on the methodological approach in bibliometric analysis. However, citations may depend not only on the scientific quality of a study but also on factors such as visibility. For example, when preparing a study, researchers may access and cite a study on a similar topic instead of articles that are not accessible in full text. In later periods, they may access and cite a study that was not previously accessible in full text. Therefore, it would be appropriate to repeat the bibliometric analysis every five years to obtain information about the current status of studies.

In addition, the results obtained in this study are limited to articles published in English in databases such as WoS that include journals that apply a rigorous evaluation system. In another study, by including journals included in Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and similar databases or all databases included in WoS and other types of studies (studies published in languages other than English, conference papers, etc.), a more general perspective can be provided compared to the results presented in this study. Another limitation of this study is that, in bibliometric analyses, the selected keyword analyses may differ depending on the parameters used. Furthermore, author keywords were used in this study. The results may differ according to the keywords or other parameters considered as references in the analyses. In another study, the analyses can be repeated according to other parameters which are not used in this study, and the networks and structures that emerge according to different parameters can be discussed comparatively. What is more, bibliometric analyses in this study were performed with the help of two different programs (VOSviewer and the R biblioshiny packet program). Each program has its own strengths as well as limitations. For instance, while R biblioshiny stands out for its user-friendliness, such as offering open-source access, and for its strengths in information-structure-based analyses like co-word or co-citation analyses or performance analyses; VOSviewer boasts a rich variety of types of graphical presentation of data. Crucially, a current limitation of both tools is the absence of integrated machine learning features for enhanced user guidance and experience. In another study, a deeper perspective on the subject can be developed by using programs such as SciMAT or CitNetExplorer, which have advanced machine-learning experiences. One of the most striking results in the trend analyses was that, although they are among current study areas in the discipline of education, technology-based topics related to subjects such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, augmented reality, and virtual reality were not addressed. Thus, it can be concluded that these issues, which are emerging in the foreground of studies, are topics that need to be examined in the future.

In summary, this study concludes by providing a much-needed, holistic perspective on the intersection of creativity and giftedness. To further expand this viewpoint, future research should incorporate diverse metrics beyond those considered and alternative bibliometric programs. This methodological diversification supports systematically addressing existing theoretical and practical gaps, as well as methodological, gifted population-specific, and historical gaps.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the continuous support and mentorship of Seokhee CHO, who welcomed me as a visiting scholar at St. John’s University under the TUBITAK project, numbered 1059B192300776. I am deeply grateful for her constructive feedback and the intellectual freedom she gave me to explore this topic. Her expertise and thoughtful critiques significantly shaped the direction and quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aleinikov, A., Kackmeister, S., & Koenig, R. (Eds.). (2000). Creating creativity: 101 definitions. Alden B Dow Creativity Center Pr. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhammash, R. (2023). Bibliometric, network, and thematic mapping analyses of metaphor and discourse in COVID-19 publications from 2020 to 2022. Frontiers Psychology, 13, 1062943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altan, E. A., & Tan, S. (2020). Concepts of creativity in design based learning in STEM education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 31, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atenstaedt, R. (2012). Word cloud analysis of the BJGP. The British Journal of General Practice, 62(596), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccassino, F., & Pinnelli, S. (2023). Giftedness and gifted education: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1073007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2009). Intelligence and personality as predictors of divergent thinking: The role of general, fluid and crystallised intelligence. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M., Furnham, A., & Safiullina, X. (2010). Intelligence, general knowledge and personality as predictors of creativity. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 532−535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, B. C. (1969). Bradford’s law and the bibliography of science. Nature, 224(5223), 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., & Laville, F. (1991). Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics, 22(3), 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. H., Nijenhuis, J. T., VanVianen, A. E., Kim, H. B., & Lee, K. H. (2010). The relationship between diverse components of intelligence and creativity. The Journal of Creative Behaviour, 44(2), 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Yi, S., & Lee, K. C. (2011). Analysis of keyword networks in MIS research and implications for predicting knowledge evolution. Information & Management, 48, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., Martinez, M. A., Gutierrez-Salcedo, M., Fujita, H., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2015). 25 years at knowledge-based systems: A bibliometric analysis. Knowledge-Based Systems, 80, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Araya, C. A., Gómez-Araya, C. A., Muñoz-Huerta, Y. P., & Reyes-Vergara, C. P. (2021). What do we know about giftedness and underachievement? A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 7(2), 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N., Veras, L., & Gosain, A. (2018). Using Bradfor’s law of scattering to identify the core journals of pediatric surgery. The Journal of Surgical Research, 229, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O., & Wallin, J. A. (2015). The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs-Beauchamp, K. D., Karnes, M. B., & Johnson, L. J. (1993). Creativity and intelligence in preschoolers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 37(3), 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., & Bachtiar, V. (2008). Personality and intelligence as predictors of creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, F. (2005). From gifts to talents the DMGT as a developmental model. In R. J. Sternberg, & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 98–119). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Getzels, J. W., & Jackson, P. W. (1962). Creativity and intelligence: Explorations with gifted students. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2013). Rewriting the language of creativity: The Five A’s framework. Review of General Psychology, 17(1), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1966). Measurement and creativity. Theory into Practice, 5(4), 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Haunschild, R., & Bornmann, L. (2024). The use of OpenAlex to produce meaningful bibliometric global overlay maps of science on the individual, institutional, and national levels. PLoS ONE, 19(12), e0308041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, K. H., Perleth, C., & Lim, T. K. (2005). The Munich model of giftedness designed to identify and promote gifted students. In R. J. Sternberg, & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 327–342). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Torrano, D., & Kuzhabekova, A. (2020). The state and development of research in the field of gifted education over 60 years: A bibliometric study of four gifted education journals (1957–2017). High Ability Studies, 31(2), 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, J., Mun, R. U. E., Oveross, M. K., & Ottwein, J. (2021). Assessing the scholarly reach of Terman’s work. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(1), 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J. L., & Blankson, A. N. (2016). Foundations for better understanding of cognitive abilities. In D. P. Flanagan, & P. L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (3rd ed., pp. 73–98). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, J. L., & Cattell, R. B. (1966). Refinement and test of the theory of fluid and crystallized general intelligences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 57(5), 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E., Benedek, M., Dunst, B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2013). The relationship between intelligence and creativity: New support for the threshold hypothesis by mean of empirical breakpoints detection. Intelligence, 41(4), 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, J. L., Hodges, J., & Vlaamster, T. (2024). Australian gifted education scholarship: A bibliometric analysis. High Abilities Studies, 35(2), 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Kaufman, S. B., & Lichtenberg, E. O. (2011). Finding creative potential on intelligence tests via divergent production. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 26(2), 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keathley-Herring, H., Van Aken, E., Gonzalez-Aleu, F., Deschamps, F., Letens, G., & Orlandini, P. C. (2016). Assessing the maturity of a research area: Bibliometric review and proposed framework. Scientometrics, 109, 927–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H. (2005). Can only intelligent people be creative? A meta-analysis. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H., Cramond, B., & VanTassel-Baska, J. (2010). The relationship between creativity and intelligence. In J. C. Kaufman, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 395–412). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzhabekova, A., Hendel, D. D., & Chapman, D. W. (2015). Mapping global research on international higher education. Research in Higher Education, 56(8), 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., & Kumar, S. (2024). Guidelines for interpreting the results of bibliometric analysis: A sensemaking approach. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(2), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBee, M. T., & Makel, M. C. (2019). The quantitative implications of definitions of giftedness. AERA Open, 5(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J. A., Herrera-Viedma, E., Santisteban-Espejo, A., & Cobo, M. J. (2020). Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. El Profesional de la Información, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulay, P., Joshi, R., & Chaudhari, A. (2020). Distributed incremental clustering algorithms: A bibliometric and word-cloud review analysis. Science & Technology Libraries, 39(3), 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, A., Sipahi, Y., & Bahar, K. A. (2024). The past, present, and future of research on mathematical giftedness: A bibliometric analysis. Gifted Child Quarterly, 68(3), 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucker, J. A. (2010). Is the proof in the pudding? Reanalyses of Torrance’s (1958 to Present) longitudinal data. Creativity Research Journal, 12(2), 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preckel, F., Holling, H., & Wiese, M. (2006). Relationship of intelligence and creativity in gifted and non-gifted students: An investigation of threshold theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. (1969). Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation, 25(4), 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Renzulli, J. S. (2005). The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for promoting creative productivity. In R. J. Sternberg, & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 246–279). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, B. O. (1966). Creativity in monozygotic and dyzygotic’ twins (ERIC Number: ED109580). University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, R. (2014). Library science: Forgotten founder of bibliometrics. Nature, 510(7504), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A. (2007). Creativity theories and themes: Research, development, and practice. Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Runco, M. A., & Albert, R. S. (1986). The threshold theory regarding creativity and intelligence: An empirical test with gifted and nongifted children. The Creative Child and Adult Quarterly, 11(4), 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Runco, M. A., Millar, G., Acar, S., & Cramond, B. (2010). Torrance tests of creative thinking as predictors of personal and public achievement: A fifty-year follow-up. Creativity Research Journal, 22(4), 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, U. (2009). Gifted education programs (Üstün yetenekliler eğitim programları). Maya Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, P. L. (2008). Creativity and intelligence revisited: A latent variable analysis of Wallach and Kogan (1965). Creativity Research Journal, 20(1), 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D. K. (2000). Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55(1), 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sligh, A. C., Conners, F. A., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, B. (2005). Relation of creativity to fluid and crystallized intelligence. Journal of Creative Behavior, 39(2), 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A. O. (1967). A comparative analysis of creative and intelligent behavior of elementary school children with different socio-economic backgrounds. Final progress report (ERIC Number: ED017022). The American University. [Google Scholar]

- Spearman, C. (1904). General intelligence. Objectively determined and measured. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 201–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (1984). What should intelligence tests test? Implications of a triarchic theory of intelligence for intelligence testing. American Educational Research Association, 13(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (2005). The WICS model of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Definitions and conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 327–342). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1991). An investment theory of creativity and its development. Human Development, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, C., Baas, M., & van der Maas, H. (2021). A Minimal theory of creative ability. Journal of Intelligence, 9(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F. (2014a). The effectiveness of mentoring strategy for developing the creative potential of the gifted and non-gifted students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 14, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F. (2014b). Yaratıcılık–zeka ilişkisi: Yeni deliller. İlkogretim Online, 13(4), 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F. (2015a). A research on the structure of intelligence and creativity, and creativity style. Turkish Journal of Giftedness and Education, 5(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, F. (2015b). Curriculum differentiation of gifted students in general educational classes: Mentorship as an implementable strategy. The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies, 33, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F. (2022). Kuramdan uygulamaya zeka ve üstün zeka. Nobel Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Şakar, S., & Tan, S. (2025). Research topics and trends in gifted education: A structural topic model. Gifted Child Quarterly, 69(1), 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L. L. (1938). Primary mental abilities. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Jacob K. Javits gifted and talented students education program. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/javits/index.html (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Wallbrown, F. H., & Huelsman, C. B. (1975). The validity of the Wallace-Kogan creativity operations for inner-city children in two areas of visual art. Journal of Personality, 43(1), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316(5827), 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).