Abstract

The rapid advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies is driving a profound transformation in higher education, shifting traditional learning toward digital, remote, and AI-mediated environments. This shift—accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic—has made computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) a central pedagogical model for engaging students in virtual, interactive, and peer-based learning. However, while these environments enhance access and flexibility, they also introduce new emotional, social, and intercultural challenges that students must navigate without the benefit of face-to-face interaction. In this evolving context, Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) has become increasingly essential—not only for supporting student well-being but also for fostering the self-efficacy, adaptability, and interpersonal competencies required for success in AI-enhanced academic settings. Despite its importance, the role of SEL in higher education—particularly within CSCL frameworks—remains underexplored. This study investigates how SEL, and specifically cultural empathy, influences students’ learning experiences in multicultural CSCL environments. Grounded in Bandura’s social cognitive theory and Allport’s Contact Theory, this study builds on theoretical insights that position emotional stability, social competence, and cultural empathy as critical SEL dimensions for promoting equity, collaboration, and effective participation in diverse, AI-supported learning settings. A quantitative study was conducted with 258 bachelor’s and master’s students on a multicultural campus. Using the Multicultural Social and Emotional Learning (SEL CASTLE) model, the research examined the relationships among SEL competencies and self-efficacy in CSCL environments. Findings reveal that cultural empathy plays a mediating role between emotional and social competencies and academic self-efficacy, emphasizing its importance in enhancing collaborative learning experiences within AI-driven environments. The results highlight the urgent need to cultivate cultural empathy to support inclusive, effective digital learning across diverse educational settings. This study contributes to the fields of intercultural education and digital pedagogy by presenting the SEL CASTLE model and demonstrating the significance of integrating SEL into AI-supported collaborative learning. Strengthening these competencies is essential for preparing students to thrive in a globally interconnected academic and professional landscape.

1. Introduction

This article examines the role of multicultural Social–Emotional Learning (SEL) as a key enabler of higher education in the era of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As global education systems adapt to rapid technological advancements, particularly during disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic, institutions have increasingly relied on remote learning models (Strielkowski et al., 2024). The rise of AI and digital technologies has intensified the need for higher education to support students not only cognitively but also socially and emotionally in diverse, technology-mediated environments.

Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) plays a vital role in the AI era by fostering collaborative, interactive, and adaptive learning environments that help students navigate complex, technology-driven educational landscapes while cultivating essential social–emotional and intercultural competencies. It has become central to ensuring educational continuity during times of crisis, offering platforms for remote interaction, knowledge exchange, and collaborative learning (Kirschner et al., 2004; Tedla & Chen, 2024). While CSCL has been shown to effectively promote cognitive engagement, scholars have increasingly noted that it does not always adequately address the socio-emotional and intercultural challenges students face in digital, multicultural learning settings (Won et al., 2024).

These limitations become even more salient in AI-enhanced environments, where the integration of generative and predictive tools reshapes how learners negotiate identity, belonging, and collaboration. For example, Hsu (2025), in an autoethnographic account of ESL academic writing, demonstrates that ChatGPT not only supports cognitive processes but also intersects with students’ stress, belonging, and self-esteem, highlighting the psychological complexity of AI-mediated learning. Similarly, Singh et al. (2025), in a large-scale study of higher education students in India, show that while AI use and AI self-efficacy significantly enhance collaboration and learning performance, students also report discomfort and anxiety when adapting to these technologies. Taken together, these perspectives suggest that cultural empathy must be understood not only as a social competence for engaging with peers across cultural differences, but also as a psychological resource that enables students to manage the affective demands of AI-supported learning.

Grounded in Allport’s Contact Theory, this study positions cultural empathy as a foundational construct for equitable learning in diverse, digitally mediated academic settings. In parallel, SEL competencies—particularly emotional stability and social competence—are identified as critical enablers of student self-efficacy in AI-supported collaborative learning environments. Drawing on Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1982, 1997), self-efficacy for CSCL develops through the interplay of emotional regulation, social interaction, and perceived competence—all of which are cultivated through effective SEL.

The development of SEL competencies—particularly emotional stability, cultural empathy, and social competence—has become increasingly important for fostering effective participation, collaboration, and academic self-efficacy in CSCL environments (Sethi & Jain, 2024). These skills are especially critical in multicultural settings, yet they are frequently overlooked in higher education strategies. In response, this study advances the field by developing the SEL CASTLE model—an empirically grounded mediating framework designed to enhance CSCL in multicultural contexts. The model integrates key SEL dimensions: cultural empathy, emotional stability, social competence, and self-efficacy, with the goal of enhancing learning engagement. In doing so, it builds on and deepens existing SEL and transformative SEL approaches by introducing cultural empathy as a new mediating variable that links socio-emotional competencies to self-efficacy in AI-mediated collaboration. Moreover, the study clarifies the role of AI as a pedagogical agent within CSCL, illustrating how it actively shapes students’ interactions, learning processes, and socio-emotional experiences rather than serving only as a technological backdrop. It aims to strengthen students’ capacity to thrive in AI-driven, collaborative learning environments by addressing both cognitive and affective dimensions of learning. By embedding SEL within CSCL frameworks, the study contributes to more inclusive, adaptive, and resilient approaches to higher education in a rapidly evolving global landscape.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. AI-Driven Transformation in Higher Education: Advancing Learning Through SEL

Pedagogical approaches and learning processes in higher education have undergone significant transformation due to advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), increasingly relying on digital and computer-based learning—a shift that was markedly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Gribble & Beckmann, 2023). As universities rapidly transitioned to remote and technologically enhanced instruction, students were required to develop a new form of academic self-efficacy—one rooted in their ability to engage with digital tools, manage independent learning tasks, and adapt to computer-mediated environments (De Backer et al., 2022; Muñoz-Carril et al., 2021). In this context, Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) emerged as a key pedagogical model, not only promoting active participation but also demanding confidence in using technology to support learning (Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019).

Collaborative digital environments such as CSCL require students to activate both academic and technological self-efficacy, often yielding better academic outcomes than traditional instructional methods (Ma et al., 2023). A strong belief in one’s technological capabilities contributes significantly to academic success (Jan, 2015; Zheng & Xiao, 2024). By emphasizing technology-mediated learning processes, CSCL aligns closely with the principles of academic self-efficacy (Lipponen, 2023; Francescato et al., 2006). Furthermore, students with prior exposure to online learning and developed digital skills tend to report higher satisfaction and perceive greater instructional effectiveness in CSCL settings (Alqurashi, 2016; Won et al., 2024).

As digital fluency becomes a key determinant of academic achievement (Kamei & Harriott, 2021), the transition to computer-based and digitally mediated learning environments has required not only technical proficiency but also a significant shift in students’ learning skills and competencies. To successfully adapt to this new landscape, students must develop capabilities that go beyond cognitive functions. In particular, the ability to manage emotions, maintain motivation, and interact effectively in virtual settings has become essential. These competencies—social efficacy, emotional stability, and interpersonal regulation—form the core of SEL. The development of such SEL skills and competencies enables learners to sustain engagement, cope with uncertainty, and navigate the independent and sometimes isolating nature of digital learning. Accordingly, research is increasingly focusing on these emotional and social dimensions of learning (Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos et al., 2022), recognizing their central role in fostering academic self-efficacy. Building on this foundation, the following sections explore the contribution of specific SEL components—such as emotional stability and social competence—to learning success in collaborative, technology-enhanced environments.

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1982, 1997), self-efficacy—one’s belief in their ability to succeed in specific tasks—develops through the dynamic interplay of personal, behavioral, and environmental factors. Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) supports this development by cultivating emotional regulation, interpersonal skills, and self-awareness, which are essential for building and sustaining students’ academic self-efficacy, particularly in complex and technology-enhanced learning environments (CASEL, 2022). In digitally mediated and AI-integrated learning settings, the importance of SEL becomes even more pronounced, as effective interpersonal interaction must be intentionally facilitated and maintained (Henriksen et al., 2025; Sethi & Jain, 2024). Consequently, current SEL frameworks need to evolve to accommodate the emotional and social demands of digital higher education (Schonert-Reichl & Weissberg, 2023; Simion, 2023). Key Social Emotional Competencies (SECs)—including emotional stability and social competence—play a vital role in promoting student well-being and meaningful collaboration (Eriksen & Bru, 2023; Schoon, 2021; Serebryakova et al., 2016). Yet, these competencies remain insufficiently studied in the context of higher education, particularly within CSCL environments and Middle Eastern academic settings.

Within this evolving landscape, Transformative Social and Emotional Learning (tSEL) provides an important framework for guiding SEL development in diverse university contexts. Expanding upon traditional SEL, tSEL incorporates elements of empathy, emotional awareness, and social justice—framing emotional and social growth as essential for fostering equity and inclusion among students from varied linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Warren et al., 2022). In diverse higher education environments, where students bring different experiences, identities, and access to digital tools, tSEL supports the development of competencies that enable mutual respect, equal participation, and culturally responsive engagement—all of which are crucial for meaningful and effective learning in digitally mediated academic settings. When applied to AI-supported environments, tSEL becomes particularly relevant for addressing the psychological and socio-emotional challenges students face, such as anxiety, identity negotiation, and feelings of exclusion when interacting through algorithm-driven platforms. By emphasizing cultural empathy, tSEL provides a pathway for helping students navigate these challenges, ensuring that socio-emotional growth is integrated with the demands of AI-mediated collaboration in higher education.

2.2. Promoting Equity and Intercultural Understanding Through Allport’s Contact Theory in AI-Mediated Learning Environments

tSEL provides a powerful foundation for promoting equity in higher education by integrating social justice, emotional awareness, and empathy into the development of students’ emotional and social competencies (Warren et al., 2022). Among these competencies, cultural empathy—defined as the capacity to recognize, understand, and respond appropriately to cultural differences in values, communication, and behavior (Corradi & Levrau, 2021; Grant & Hill, 2020)—is particularly critical in academic environments marked by diversity. In higher education, where students frequently differ in language, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background, the cultivation of cultural empathy enables respectful and effective peer engagement. This is especially important in AI-mediated and digitally collaborative learning contexts, where interpersonal cues are limited and cultural misunderstandings can easily arise. To examine how such empathy can be fostered through purposeful educational design, we draw on Allport’s Contact Theory (Allport, 1954), which outlines the circumstances under which structured intergroup contact can reduce prejudice and foster inclusion—making it an essential lens for understanding equitable learning in diverse higher education settings.

In the context of diverse higher education, and especially within CSCL environments, the development of cultural empathy becomes essential. Cultural empathy supports learners in navigating differences in worldviews, behaviors, and communication styles, thereby reducing friction and promoting deeper understanding among peers. To foster this capacity, it is important to consider the foundational ideas of Allport’s Contact Theory. Originally developed in the context of race relations, Allport (1954) argued that Intergroup contact can reduce prejudice when four specific circumstances are met: (1) equal status between groups, (2) shared goals, (3) cooperative interaction, and (4) institutional support. These circumstances create a context in which individuals are more likely to move beyond stereotypes and develop mutual respect. Within CSCL environments, these principles translate into digital group learning structures that promote equality in participation, clear collaborative objectives, guided cooperation, and instructional or institutional scaffolding. When these circumstances are met, CSCL not only facilitates academic outcomes but also becomes a space where cultural empathy can thrive—allowing students to better understand one another’s experiences, challenge their assumptions, and build inclusive learning relationships across differences.

Allport’s Contact Theory offers a compelling framework for understanding how digital, multicultural learning environments can be transformed into inclusive spaces that support both academic and interpersonal growth. To realize this potential, institutional support is critical. Through inclusive curriculum design, culturally responsive pedagogy, instructor modeling, and equitable access to digital tools, institutions create the structural foundation necessary for positive intergroup interaction. Educators who intentionally design learning environments where students from diverse backgrounds feel safe to express themselves, share experiences, and collaborate meaningfully help translate the principles of Contact Theory into practice. This is particularly important in AI-integrated and digitally mediated educational contexts, where communication often lacks nonverbal cues, and misunderstandings may arise more easily. In such settings, proactive scaffolding of empathy, clarity, and mutual accountability is essential to ensuring that all learners can participate equitably and productively.

Building on Allport’s Contact Theory, the success of intergroup contact in higher education is not determined by structural circumstances alone, but also by the emotional and interpersonal competencies that students bring to collaborative settings. SECs—especially emotional stability and social competence—support students in navigating the complexities of diverse peer interaction (Eriksen & Bru, 2023; Schoon, 2021). In AI-mediated and digitally supported learning environments, where communication is often asynchronous or depersonalized, students’ ability to engage constructively becomes even more essential. Emotionally stable learners are better equipped to regulate stress, remain open to difference, and manage uncertainty in virtual collaborations (Cain et al., 2023). Socially competent students demonstrate skills such as perspective-taking, empathy, and effective communication, which are indispensable for creating inclusive and respectful dialogue in CSCL environments. These competencies align with the core aims of tSEL, which frames emotional and social development as essential for advancing equity and inclusion in technology-enhanced academic spaces (Warren et al., 2022). In this way, SEL not only enhances students’ self-efficacy but also strengthens their capacity to fulfill the interpersonal demands embedded in Allport’s framework for prejudice reduction and inclusive learning.

To summarize, the integration of AI into higher education requires not only technological adaptation but also a renewed focus on the emotional and interpersonal dimensions of learning. SECs—particularly emotional stability and social competence—are essential for enabling students to navigate the demands of digital, collaborative environments. At the same time, Allport’s Contact Theory offers a valuable framework for promoting cultural empathy and reducing bias through structured, supportive intergroup engagement. When applied to AI-mediated and culturally diverse academic settings, these complementary perspectives highlight the importance of designing learning environments that foster both self-efficacy and inclusive collaboration. This theoretical synthesis provides a foundation for examining how equity-oriented, emotionally responsive pedagogy can enhance learning outcomes and social cohesion in technology-enhanced higher education.

2.3. Purpose of Study and Hypotheses

This study investigates how key SEL competencies—social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy—relate to students’ self-efficacy for CSCL in higher education environments shaped by AI. Grounded in Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994, 1997) and Allport’s contact theory (Allport, 1954), the study explores how socio-emotional factors contribute to students’ academic self-beliefs in multicultural, digitally mediated learning contexts.

According to Bandura’s theory, self-efficacy develops through the continuous interplay of individual capabilities, social contexts, and behavioral experiences. In the context of CSCL, students’ abilities to collaborate effectively, regulate their emotions, and demonstrate intercultural empathy play a central role in building their academic confidence. In parallel, Allport’s contact theory emphasizes that meaningful intergroup interactions—rooted in empathy and collaborative effort—enhance group cohesion and educational outcomes. This principle holds particular relevance in culturally diverse, AI-supported learning environments, where structured, empathetic engagement can significantly improve collaborative learning experiences.

Recent research supports these connections: social competence aids negotiation and teamwork (Tseng et al., 2019; Hofer et al., 2021); emotional stability supports resilience (Burr et al., 2021); and cultural empathy fosters cross-cultural engagement (Corradi & Levrau, 2021; Grant & Hill, 2020). Self-efficacy itself is a strong predictor of success in digital learning environments (Alqurashi, 2016; Zheng & Xiao, 2024). These associations were further validated in earlier research (Soffer-Vital & Finkelstein, 2024).

2.4. Research Questions

- (a)

- How are the SEL competencies—social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy—related to self-efficacy for CSCL?

- (b)

- Does cultural empathy mediate the relationship between social competence, emotional stability, and self-efficacy for CSCL?

To address these questions, the following hypotheses are proposed:

2.4.1. Hypothesis 1

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), self-efficacy develops through reciprocal interactions between personal competencies and environmental demands. In digital environments, students with greater social competence and emotional stability are more confident in their collaborative abilities (Hofer et al., 2021; Junge et al., 2020). These competencies also foster cultural empathy, essential for engaging across diverse, tech-enhanced contexts (Grant & Hill, 2020).

H1:

Social competence and emotional stability are positively associated with both self-efficacy for CSCL and cultural empathy among students in higher education.

2.4.2. Hypothesis 2

SEL frameworks and Bandura’s theory highlight the interdependence of social and emotional competencies. Social competence enhances emotional regulation, while emotional stability enables effective interaction (Hofer et al., 2021; Junge et al., 2020; Eriksen & Bru, 2023).

H2:

Social competence is positively associated with emotional stability among students in higher education.

2.4.3. Hypothesis 3

Allport’s contact theory (Allport, 1954) suggests that cultural empathy promotes cross-cultural collaboration and academic self-efficacy. It may also mediate links between SEL traits and learning outcomes (Castro Olivo et al., 2021).

H3:

Cultural empathy is positively associated with self-efficacy for CSCL among students in higher education. Furthermore, cultural empathy mediates the associations between social competence and self-efficacy, and between emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL.

3. Method

This research includes a non-interventional study (anonymous questionnaires). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Board of Ethics, Central Research Ethics Committee (#202124).

3.1. Participants

Students from a multicultural Israeli college campus, studying toward either bachelor’s or master’s degrees, were invited to participate in the study. The campus includes Jewish and Muslim male and female students from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds. This composition reflects the broader higher education population in Israel, making the sample representative of students currently engaged in academic studies across the country. The sample included both traditional students and adult learners—some of whom returned to higher education later in life—which explains the wide age range of 18 to 64 years (M = 32.83, SD = 10.62). Recruitment was voluntary and carried out through institutional emails and social media, targeting all degree levels. In total, 258 students completed all sections of the questionnaire, providing full demographic and contextual data for analysis.

Most participants were women (86%), and the main disciplines were education and social studies (65%). Approximately half of the participants were studying for a bachelor’s degree (51%). Approximately 63% of the students were Muslim, and 36% were Jewish. Approximately one-third of the participants (31%) defined themselves as religiously traditional and 38% as religious. Most participants reported coming from a middle socioeconomic background (76%). The great majority of participants were born in Israel (98%). Approximately 63% of the participants were native Arabic speakers, and 35% were native Hebrew speakers.

Most participants reported no disabilities (88%), and among those who did report disabilities, the most common was learning difficulties (7%). Most participants were permanently employed (62%) and were not in an executive position (71%). Approximately 67% of those employed worked in the education or care sector. The years of employment ranged between 1 and 32 years (mean = 9.46, SD = 8.52). Most of the students (97%) reported that they expected to be able to complete their studies within the given timeframe of the college (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the students (N = 258).

3.2. Instruments and Procedures

We administered online questionnaires divided into four distinct sections, as outlined below. To minimize potential order effects, the sequence of all sections—excluding the demographic section—was randomized, and the items within each block were also presented in a random order.

- Demographic Questionnaire: This section gathered background information, including gender, age, religion, sector (Jews/Arabs), academic institution, field of study, academic degree, family socioeconomic status, country of birth, presence of disabilities, type of employment (temporary or permanent), executive role (yes/no/other), and number of years in the workforce.

- The self-efficacy for CSCL questionnaire (Mor, 2001; Salomon, 2002) is grounded in theoretical frameworks developed by Bandura (1986), Schunck (1990), and Pintrich and De Groot (1990).We adapted this instrument for the university context to assess students’ beliefs about their capabilities to engage in academic tasks, regulate their learning processes in peer settings, manage study organization, seek support within collaborative teams, and identify effective strategies for enhancing learning outcomes. Academic self-efficacy in CSCL was measured using 24 items, each targeting skills necessary for successful participation in computer-supported collaborative learning environments.The instrument differentiates between three core components of academic self-efficacy in CSCL:

- (a)

- Academic learning (e.g., “I am sure that I can do an excellent job in the academic task assigned to me”);

- (b)

- Computer-based learning (e.g., “The computer is my best learning partner”);

- (c)

- Collaborative learning (e.g., “Learning in a team promotes my learning because I am known to work in a team and activate my colleagues”).

The questionnaire underwent expert validation by three academic reviewers, who confirmed that it accurately captured self-efficacy for learning and successfully distinguished among the three sub-dimensions of self-efficacy—academic, collaborative, and computer-based. The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (α = 0.79); see Table 2. Table 2. Descriptive statistics of CSCL dimensions (N = 258).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of CSCL dimensions (N = 258). - Two subscales of the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) were used in this study:

- Cultural Empathy (18 items; α = 0.89): Content validity checks yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90. Sample items include: “Finds it hard to empathize with others,” “Enjoys other people’s stories,” and “Able to voice other people’s thoughts from different cultural backgrounds.”

- Emotional Stability (20 items; α = 0.82): Our content validation showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77. Sample items include: “Considers problems solvable,” “Suffers from conflicts with others,” and “Is not easily hurt.”

These subscales are part of the broader Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000), a 91-item instrument assessing five personality factors. Respondents rate their agreement with statements using the prompt “To what extent do the following statements apply to you?” on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = totally not applicable, 5 = completely applicable). The reliability and validity of this full version have been rigorously tested and confirmed (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000).The MPQ was translated into Hebrew and validated by Lacher Edenburg (2019), yielding an overall Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.83. Content validity was established through expert reviews and focus group sessions, which concluded that no items required rewording. In the context of AI-supported CSCL, the MPQ subscales of cultural empathy and emotional stability are especially relevant because technology-mediated collaboration often reduces access to non-verbal cues, increases the likelihood of misunderstandings, and heightens stress when negotiating across cultural differences. Measuring these constructs allows us to assess students’ capacity to regulate emotions and empathize with peers in digital environments, thereby capturing critical factors that directly influence the quality of AI-mediated collaboration. - The Social Competence Questionnaire (Valkenburg & Peter, 2008) is a 19-item self-report measure designed to assess social competence across four distinct dimensions: initiation of (offline) relationships or interactions, supportiveness, assertiveness, and the ability to self-disclose. These four predefined dimensions were empirically validated through exploratory factor analysis. To determine whether these dimensions were components of a broader construct, a second-order confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, confirming that a single overarching social competence factor underpinned the four subscales.Participants were asked to reflect on how they had managed various interpersonal situations over the previous six months. Each subscale is illustrated below with example items and internal consistency coefficients:

- Initiation (α = 0.86): e.g., “Start a conversation with someone you did not know very well.”

- Supportiveness (α = 0.83): e.g., “Listen carefully to someone who told you about a problem they were experiencing.”

- Self-disclosure (α = 0.83): e.g., “Express your feelings to someone else.”

- Assertiveness (α = 0.86): e.g., “Stand up for your rights when someone wronged you.” In AI-mediated CSCL, the SCQ provides a robust measure of students’ ability to initiate and sustain relationships, offer support, assert themselves, and disclose appropriately in environments where communication is technology-driven and face-to-face interaction is limited. These competencies are particularly critical for collaborative platforms where cues such as tone, body language, and immediacy are often absent, making explicit social competence a key determinant of effective teamwork and digital collaboration.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS version 21. First, we examined the reliability of the questionnaires by Cronbach’s alpha. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the normal distribution of the main variables. In addition, regression assumptions were tested prior to the analyses: variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern, normality was supported by the distribution tests, and effect sizes were reported to provide information on the magnitude of relationships. For summarization and analysis of the data, we used frequency distribution for categorical variables and means and SD for quantitative variables. Pearson correlation was used to analyze the relations between the main SEL research variables. To examine the relations between the socio-demographic variables and the main research variables, we used Pearson/Spearman correlation analysis. Hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to predict SEL. Socio-demographic variables were used in the first step of the model, followed by the other independent variables. Baron and Kenny’s (1986) regression model was used for mediation analysis. Cultural empathy was conceptualized as a mediator rather than a moderator because the theoretical assumption was that socio-emotional competencies (such as emotional stability and social competence) influence self-efficacy indirectly through the development of intercultural understanding. In other words, cultural empathy functions as a process variable that transmits the effect of socio-emotional competencies onto self-efficacy, rather than as a boundary condition that would alter the strength of those relationships.

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

Initially, we used Spearman correlation to test the relations between the study variables. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Spearman Correlation Coefficients Between the Main Study Variables (N = 258).

According to the data presented in Table 3, a significant positive correlation was found between social competence and self-efficacy for CSCL (rs = 0.47, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher social competence have higher self-efficacy for CSCL. A significant positive correlation was also found between emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL (rs = 0.47, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher emotional stability have higher academic self-efficacy for CSCL. A significant positive correlation was found between social competence and cultural empathy (rs = 0.49, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher social competence have higher cultural empathy. A significant positive correlation was also found between emotional stability and cultural empathy (rs = 0.33, p < 0.01) as well, indicating that students with higher emotional stability also have higher cultural empathy. These findings support the first hypothesis that social competence and emotional stability are positively associated with self-efficacy for CSCL and cultural empathy.

We also found a significant positive correlation between social competence and emotional stability (rs = 0.43, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher social competence also have higher emotional stability. This finding supports the second hypothesis that social competence is positively associated with emotional stability.

We found a significant positive correlation between cultural empathy and self-efficacy for CSCL (rs = 0.48, p < 0.01), indicating that students with higher cultural empathy have higher self-efficacy for CSCL. The relation between these two variables was tested by two-tailed correlation; therefore, students with higher cultural empathy possess a higher academic self-efficacy for CSCL. We also found that cultural empathy was significantly and positively correlated with computer-based learning (rs = 0.28, p < 0.01) and collaborative learning (rs = 0.31, p < 0.01), and academic learning (rs = 0.49, p < 0.01). Students with higher cultural empathy were thus better at computer-based learning, academic learning and collaborative learning. Because the test is bidirectional, higher computer-based learning and collaborative learning abilities are also associated with higher cultural empathy. This finding supports the third hypothesis that cultural empathy is positively associated with self-efficacy for CSCL. These coefficients suggest that students with higher levels of cultural empathy are more capable of transforming emotional and social competencies into effective collaboration, particularly when working across linguistic or cultural divides in AI-mediated environments.

4.2. A Prediction Model for Self-Efficacy for CSCL

We used a hierarchical linear regression model to predict self-efficacy for CSCL. In the first step, the model included background demographics related to self-efficacy for CSCL and the three subcategories (computer-based learning, academic learning and collaborative learning) as simple effects. In the second step, the predictive variables (social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy) were added to the model. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Predicting Self-Efficacy for CSCL from Demographic Variables and from the Main Study Variables.

Self-efficacy for CSCL (total scale): The regression model for the prediction of self-efficacy for CSCL was statistically significant (F(9, 255)) = 18.36, p < 0.01). The predictive variables explained 40% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL. As indicated by the regression coefficients in the first step, the variables degree, attention to emotional and social issues in the academic institutions, and a sense of belonging contributed significantly to the prediction of self-efficacy for CSCL. Studying for a higher academic degree, greater attention to emotional and social issues in the educational institutions, and a higher sense of belonging were associated with higher self-efficacy for learning. These predictive variables explained 17% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL. In the second step, the predictive variables of social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy contributed significantly to the prediction of self-efficacy for CSCL. Higher social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy were associated with higher self-efficacy for learning. These predictive variables explained an additional 23% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL.

Self-efficacy for CSCL (total scale): The regression model predicting self-efficacy in CSCL was statistically significant (F(9, 255) = 18.36, p < 0.01), accounting for 40% of the total variance. In the first step of the analysis, three variables—academic degree level, institutional emphasis on emotional and social aspects, and students’ sense of belonging—emerged as significant predictors of self-efficacy for CSCL. Specifically, pursuing an advanced academic degree, experiencing greater institutional attention to social–emotional dimensions, and reporting a stronger sense of belonging were all positively associated with higher levels of self-efficacy for collaborative digital learning. Collectively, these variables explained 17% of the variance. In the second step, three additional predictors—social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy—contributed significantly to the model. Students who demonstrated higher levels of these social–emotional competencies also reported greater self-efficacy in CSCL environments. These variables accounted for an additional 23% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL.

Academic learning: The regression model for the prediction of academic learning was statistically significant (F(5, 256)) = 40.74, p < 0.01). The predictive variables explained 43% of the variance in academic learning. In the first step, the background variables of age and a sense of belonging to the academic institute contributed significantly to the prediction of academic learning. Older age and a higher sense of belonging to the educational institute were associated with higher ability for academic learning. These predictive variables explained 14% of the variance in academic learning. In the second step, the predictive variables of social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy contributed significantly to the prediction of academic learning. Higher social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy were associated with higher academic learning. These predictive variables explained a further 29% of the variance in computer-based learning.

Computer-based learning: The regression model for the prediction of computer-based learning was statistically significant (F(5, 256)) = 7.08, p < 0.01). The predictive variables explained 12% of the variance in computer-based learning. In the first step, the background variables of degree and a sense of belonging to the academic institute contributed significantly to the prediction of computer-based learning. Studying for a higher academic degree and a higher sense of belonging to the educational institute were associated with higher ability for computer-based learning. These predictive variables explained 5% of the variance in computer-based learning. In the second step, only the cultural empathy variable contributed significantly to the model. Higher cultural empathy was associated with higher ability for computer-based learning. This predictive variable explained a further 7% of the variance in computer-based learning.

Collaborative learning: The regression model for the prediction of collaborative learning was statistically significant (F(5, 256)) = 8.37, p < 0.01). The predictive variables explained 14% of the variance in collaborative learning. In the first step, the background variables of degree and attention to emotional and social issues in the educational institution contributed significantly to the prediction of collaborative learning. Studying for a higher academic degree and greater attention to emotional and social issues in the academic institution were associated with higher collaborative learning. These predictive variables explained 9% of the variance in collaborative learning. In the second step, only the social competence variable contributed significantly to the model. Higher social competence was associated with higher collaborative learning. This predictive variable explained further 5% of the variance in collaborative learning.

4.3. Mediation Analysis

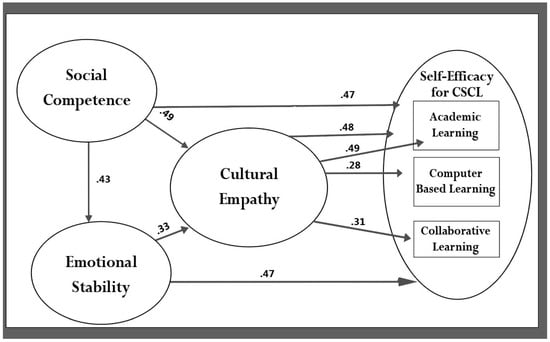

We employed a mediation model to examine whether cultural empathy mediates the relationships between social competence and self-efficacy, and between emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL, following the mediation analysis steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). Prior research has identified positive associations between empathy and both socio-emotional functioning and social competence. In this context, a partial mediator implies a reduction—but not elimination—of the direct relationship between the independent and dependent variables, whereas a full mediator entirely accounts for the association. The findings are detailed in Table 5 and Figure 1.

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients for Predicting Self-Efficacy for CSCL from Social Competence and Cultural Empathy.

Figure 1.

The Empirical SEL CASTLE Model. The model indicates a r = 0.31 correlation between cultural empathy and self-efficacy for collaborative learning within CSCL (p < 0.05), which includes computer-based learning, collaborative learning, and academic learning. Spearman coefficients are indicated, p < 0.01 for all correlations.

As shown in Table 5, the regression model for the prediction of self-efficacy for CSCL was statistically significant (F(2, 257) = 63.81, p < 0.01) (third model). The predictive variables explained 33% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL. In the first model, there was a statistically significant positive association between social competence (independent variable) and self-efficacy for CSCL (dependent variable). In the second model, there was a statistically significant positive association between social competence (independent variable) and cultural empathy (mediator). In the third model, there was a statistically significant positive association between cultural empathy (mediator) and self-efficacy for CSCL (dependent variable). In addition, the association between social competence and self-efficacy for CSCL was reduced when cultural empathy was included in the model as a mediator variable. These results indicate that, according to Baron & Kenny’s mediation conditions, cultural empathy partially mediates the association between social competence and self-efficacy for CSCL. Given that the standardized coefficients in this model ranged from β = 0.31 to β = 0.49, these effects are conventionally interpreted as moderate. This suggests that cultural empathy provides a practically meaningful pathway through which social competence enhances collaborative efficacy in AI-mediated environments.

As shown in Table 6, the regression model for the prediction of self-efficacy for CSCL was statistically significant (F(2, 257) = 64.81, p < 0.01) (third model). The predictive variables explained 33% of the variance in self-efficacy for CSCL. In the first model, there was a statistically significant positive association between emotional stability (independent variable) and self-efficacy for CSCL (dependent variable). In the second model, there was a statistically significant positive association between emotional stability (independent variable) and cultural empathy (mediator variable). In the third model, there was a statistically significant positive association between cultural empathy (mediator variable) and self-efficacy for CSCL (dependent variable). In addition, the association between emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL was reduced when cultural empathy was included in the model as a mediator variable. These results indicate that, according to Baron & Kenny’s mediation conditions, cultural empathy partially mediates the association between emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL. These results indicate that cultural empathy mediates the association between both SEL parameters of social competence and emotional stability and self-efficacy for CSCL. The standardized coefficients in this model ranged from β = 0.29 to β = 0.43, also in the moderate range. This reinforces that cultural empathy is not only statistically significant but pedagogically meaningful as a mediating factor, helping students translate emotional stability into higher self-efficacy in digital collaborative learning.

Table 6.

Regression Coefficients for Predicting self-efficacy for CSCL from Emotional Stability and Cultural Empathy.

We also found a significant positive correlation between emotional stability and computer-based learning (rs = 0.26, p < 0.01), collaborative learning (rs = 0.22, p < 0.01), and academic learning (rs = 0.48, p < 0.01).

Students with higher emotional stability had higher computer-based learning, academic learning and collaborative learning. Because the test is bidirectional, higher computer-based learning and collaborative learning are associated with higher emotional stability. We found a significant positive correlation between social competence and computer-based learning (rs = 0.29, p < 0.01) and collaborative learning (rs = 0.22, p < 0.01), and academic learning (rs = 0.54, p < 0.01).

The empirical SEL CASTLE model, based on our findings, is presented in Figure 1. The SEL CASTLE model presents all the direct and indirect paths involving the interacting variables that were validated in this research. The model illustrates significant interaction specifically between social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy. Of particular interest is the central role that cultural empathy plays as a mediating factor between social competence, emotional stability and academic self-efficacy for CSCL. As the research model shows, social competence and emotional stability are positively associated with both academic self-efficacy for CSCL and cultural empathy, while cultural empathy is itself positively associated with academic self-efficacy for CSCL. Higher social competence was also associated with higher collaborative learning. The model also suggests that cultural empathy, emotional stability and social competence are positively associated with computer-based, academic, and collaborative learning (Figure 1 and Table 6). For clarity, Figure 1 has been updated to display standardized coefficients for each path, allowing readers to assess the relative strength of direct and mediated effects.

The SEL CASTLE model contributes beyond transformative SEL by explicitly integrating cultural empathy and adaptive collaboration as central dimensions, thereby addressing gaps in how SEL frameworks support intercultural learning in AI-mediated contexts. To clarify this distinctiveness, we provide a conceptual figure that visually contrasts CASTLE with existing SEL and tSEL models, highlighting its unique contributions. Figure 1 depicts the interactions and the degrees of influence of social competence and emotional stability on cultural empathy and these three SEL parameters’ effects on and the latter’s mediation of self-efficacy for CSCL.

5. Discussion

This study introduces the SEL CASTLE Model, which empirically demonstrates how cultural empathy mediates the relationship between social competence, emotional stability, and self-efficacy for CSCL. The findings are significant in the context of the AI era, where the rapid shift to CSCL-based pedagogy has been driven by global challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical crises. As higher education increasingly adopts AI-driven platforms and virtual environments, addressing the social and emotional dimensions of learning is crucial.

The SEL CASTLE Model highlights the interaction between social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy, showing how these factors collectively enhance self-efficacy for CSCL. Our findings demonstrate that students with higher social competence and emotional stability exhibit greater cultural empathy, which, in turn, improves their self-efficacy in collaborative learning environments. This mediating role of cultural empathy confirms our hypotheses: social competence and emotional stability are positively associated with cultural empathy and self-efficacy for CSCL (H1), social competence is positively associated with emotional stability (H2), and cultural empathy mediates these relationships (H3). For example, in digital teamwork settings, cultural empathy may help students interpret ambiguous messages, manage misunderstandings, and maintain group cohesion despite the absence of non-verbal cues. Our mediation analysis further demonstrated that the indirect effects of cultural empathy were moderate in size (β = 0.29–0.49), underscoring its role as both a statistically robust and pedagogically meaningful construct. These findings suggest that strengthening cultural empathy can produce tangible improvements in students’ collaborative self-efficacy, particularly when navigating AI-mediated and multicultural learning environments. This highlights the importance of embedding SEL practices within CSCL design to foster not only cognitive but also socio-emotional and intercultural growth.

Cultural empathy plays a central role in facilitating meaningful connections and collaboration, as it involves understanding, appreciating, and respecting diverse perspectives. This competency is critical for collaboration and effective communication in multicultural settings. It fosters constructive dialogue, mutual respect, and cross-cultural understanding, essential for teamwork and problem-solving in diverse groups (Corradi & Levrau, 2021; Grant & Hill, 2020). In AI-driven learning environments, cultural empathy allows students to engage empathetically with peers from diverse cultural contexts, enhancing virtual collaboration and interaction (Sethi & Jain, 2024). For example, in AI-mediated CSCL projects, cultural empathy can reduce socio-emotional strain by helping students manage miscommunication or conflict in online teamwork, while also fostering greater confidence in intercultural exchanges that rely heavily on digital platforms.

Self-efficacy for CSCL is closely tied to students’ ability to adapt to digital learning environments. Students with high self-efficacy are better equipped to manage online platforms, balance tasks, and maintain motivation (Kamei & Harriott, 2021). Cultural empathy strengthens these abilities by fostering trust and collaboration within diverse groups, aligning with existing research on enhancing teamwork and academic performance in multicultural contexts (Jones & Doolittle, 2017; Jones & Kahn, 2017).

The SEL CASTLE Model offers a valuable framework for understanding how SEL competencies interact to shape self-efficacy for CSCL. By promoting cultural empathy, higher education institutions can foster inclusivity and equity, supporting students from diverse backgrounds. The integration of SEL principles into CSCL frameworks is essential to ensure technology enhances, rather than hinders, social and emotional development in digital learning environments. These findings suggest that AI should not be viewed merely as a neutral backdrop but as an active pedagogical agent that shapes students’ intercultural and emotional experiences. As shown by Singh et al. (2025) and Hsu (2025), AI tools can simultaneously enhance collaboration and self-efficacy while also generating stress, discomfort, and identity-related challenges. Within the SEL CASTLE model, cultural empathy mediates these psychological demands by turning potential strain into opportunities for resilience, confidence, and meaningful engagement in AI-mediated CSCL. This study extends Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994, 1997) by showing that social competence and emotional stability positively influence cultural empathy and self-efficacy in CSCL contexts. Moreover, it builds on Allport’s contact theory (Allport, 1954), confirming that cultural empathy mediates the relationship between personal competencies and self-efficacy, supporting inclusive collaboration in multicultural digital learning spaces.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Our study focuses on bachelor’s and master’s students, highlighting the need for longitudinal research across additional educational levels. The limited research on SEL interventions in culturally diverse populations further underscores the importance of broader exploration to enhance academic success and well-being. Future studies should integrate SEL into curricula and advocate for SECs in educational policies. Another limitation is the exclusive reliance on self-report measures, which may introduce social desirability bias, particularly in multicultural contexts where empathy and social competence are highly valued. Self-report data also cannot fully capture the complex dynamics of intercultural collaboration; therefore, future studies should adopt mixed-method approaches, such as discourse-based analyses of CSCL interactions or autoethnographic accounts (e.g., Hsu, 2025), to provide richer and more triangulated evidence for the socio-emotional and intercultural claims advanced in this study. Finally, the study did not test subgroup differences (e.g., bachelor’s vs. master’s, or domestic vs. international students). Although the sample was diverse, subgroup sizes were too small for robust multi-group mediation. This limitation highlights an important agenda for future research: examining whether the mediating role of cultural empathy varies across student backgrounds. Such analyses—distinguishing, for example, between degree levels or cultural contexts—will be essential for advancing inclusive and equitable designs of AI-supported collaborative learning environments.

7. Conclusions

As higher education becomes increasingly multicultural, cultivating cultural empathy is essential in the AI era, equipping students to collaborate effectively in a globally connected world. This study highlights the critical role of inclusive Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) in enriching diverse learners’ experiences, aligning with the OECD’s call for holistic student development (OECD, 2021, p. 151). The SEL CASTLE Model presents a novel framework showing how social competence and emotional stability foster cultural empathy, which in turn enhances self-efficacy in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL). As AI-driven learning environments expand, cultural empathy strengthens both individual adaptability and group cohesion. Emphasizing it as a core SEL competency supports inclusive, emotionally intelligent collaboration. Ultimately, the SEL CASTLE Model provides a roadmap for integrating social, emotional, and cultural dimensions into CSCL frameworks, ensuring that technological advances in education serve human connection and understanding in an age of digital transformation.

8. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study advances understanding of SEL in CSCL by showing how social competence, emotional stability, and cultural empathy jointly shape students’ self-efficacy in digital learning. Grounded in Bandura’s social cognitive theory and Allport’s contact theory, our findings demonstrate that cultural empathy mediates the effects of socio-emotional competencies on self-efficacy, highlighting the value of emotional regulation and intercultural responsiveness. We propose the SEL CASTLE Model—a novel framework that positions cultural empathy as central to SEL-CSCL integration. This model contributes to both theories by emphasizing how cultural empathy fosters meaningful collaboration in diverse, AI-enhanced higher educational settings.

Practically, the findings call for embedding SEL competencies into curricula and pedagogy to create inclusive, culturally responsive learning environments. By promoting cultural empathy and belonging, especially for marginalized students, institutions can strengthen engagement and collaboration, preparing learners for success in global, multicultural, and digitally mediated academic contexts. Beyond general integration, these competencies can be advanced through concrete strategies such as AI-supported peer feedback tasks, which provide students with personalized guidance on inclusivity, and structured intercultural reflection activities, which prompt learners to critically examine cultural assumptions and emotional responses in collaborative settings. In AI-supported platforms, these implications can be operationalized through pedagogical designs that deliberately address students’ different levels of cultural empathy.

Adaptive collaboration tools can group learners with complementary empathy profiles, ensuring balanced participation while providing scaffolds for those with less intercultural experience. AI-mediated feedback, delivered through reflective journaling or curated peer commentary, can be personalized—offering structured guidance on inclusivity and emotional cues for beginners, while prompting more advanced students to reflect on subtle cultural assumptions and biases. Scenario-based simulations can also be tailored in complexity, ranging from straightforward intercultural misunderstandings for novices to multifaceted dilemmas for more empathetic students, thereby ensuring meaningful engagement for all. Finally, guided reflection activities help consolidate learning by encouraging deeper awareness of emotional regulation and intercultural differences, promoting growth across the full spectrum of cultural empathy. Aligned with the SEL CASTLE model, these practices map directly onto its core dimensions: adaptive collaboration fosters social competence, AI-mediated feedback reinforces emotional stability and cultural empathy, simulations immerse learners in intercultural problem-solving to deepen empathy, and guided reflections integrate these skills to build self-efficacy. Importantly, these applications demonstrate that the model is not only theoretical but also actionable, offering a framework for designing AI-mediated learning environments that directly foster inclusivity and empathy. By translating the SEL CASTLE model into pedagogical strategies, educators can create scalable practices that respond to diverse learners’ cultural and emotional needs in ways that traditional methods often overlook.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Methodology, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Validation, I.F., and S.S.-V.; Formal Analysis, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Data Curation, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Writing—Original Draft, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Writing—Review & Editing, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Supervision, I.F. and S.S.-V.; Project Administration, I.F. and S.S.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ono Academic College Central Research Ethics Committee (protocol code 202124ono, date of approval 16 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and anonymity considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Alqurashi, E. (2016). Self-efficacy in online learning environments: A literature review. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), 9(1), 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos, V., Matarranz, M., Casado-Aranda, L. A., & Otto, A. (2022). Teachers’ digital competencies in higher education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, D. A., Castrellon, J. J., Zald, D. H., & Samanez-Larkin, G. R. (2021). Emotion dynamics across adulthood in everyday life: Older adults are more emotionally stable and better at regulating desires. Emotion, 21(3), 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, M., Campbell, C., & Coleman, K. (2023). ‘Kindness and empathy beyond all else’: Challenges to professional identities of higher education teachers during COVID-19 times. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(4), 1233–1251. [Google Scholar]

- CASEL [Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning]. (2022). Introduction to SEL. What is SEL? Available online: http://casel.org/why-it-matters/what-is-sel/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Castro Olivo, S. M., Ura, S., & dAbreu, A. (2021). The effects of a culturally adapted program on ELL students’ core SEL competencies as measured by a modified version of the BERS-2. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 38(4), 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, D., & Levrau, F. (2021). Social adjustment and dynamics of segregation in higher education–Scrutinising the role of open-mindedness and empathy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 84, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- De Backer, L., Van Keer, H., De Smedt, F., Merchie, E., & Valcke, M. (2022). Identifying regulation profiles during computer-supported collaborative learning and examining their relation with students’ performance, motivation, and self-efficacy for learning. Computers & Education, 179, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, E. V., & Bru, E. (2023). Investigating the links of social emotional competencies: Emotional wellbeing and academic engagement among adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(3), 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francescato, D., Porcelli, R., Mebane, M., Cuddetta, M., Klobas, J., & Renzi, P. (2006). Evaluation of the efficacy of collaborative learning in face-to-face and computer-supported university contexts. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(2), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D. E., Jr., & Hill, J. B. (2020). Activating culturally empathic motivation in diverse students. Journal of Education and Learning, 9(5), 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, L., & Beckmann, E. A. (2023). The 4 Cs strategy for disseminating innovations in university teaching: Classroom, corridors, campus, community. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(1), 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, D., Creely, E., Gruber, N., & Leahy, S. (2025). Social-emotional learning and generative AI: A critical literature review and framework for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 76(3), 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sellés, N., Muñoz-Carril, P. C., & González-Sanmamed, M. (2019). Computer-supported collaborative learning: An analysis of the relationship between interaction, emotional support and online collaborative tools. Computers & Education, 138, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S. I., Nistor, N., & Scheibenzuber, C. (2021). Online teaching and learning in higher education: Lessons learned in crisis situations. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. P. (2025). An autoethnographic study of ESL academic writing with ChatGPT: From psychological insights to the SUPER framework. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2543113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S. K. (2015). The relationships between academic self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, prior experience, and satisfaction with online learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 29(1), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. M., & Doolittle, E. J. (2017). Social and emotional learning: Introducing the issue. The Future of Children, 27(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. M., & Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence base for how we learn: Supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development. In Consensus statements of evidence from the council of distinguished scientists. Aspen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Junge, C., Valkenburg, P. M., Deković, M., & Branje, S. (2020). The building blocks of social competence: Contributions of the Consortium of Individual Development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 45, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, A., & Harriott, W. (2021). Social emotional learning in virtual settings: Intervention strategies. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 13(3), 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P. A., Martens, R. L., & Strijbos, J. W. (2004). CSCL in higher education? In What we know about CSCL. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher Edenburg, L. (2019). Examining the relationship between social network participation and social competence and loneliness among people with an intellectual disability [Master’s thesis, Haifa University]. [Google Scholar]

- Lipponen, L. (2023). Exploring foundations for computer-supported collaborative learning. In Computer support for collaborative learning (pp. 72–81). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X., Liu, J., Liang, J., & Fan, C. (2023). An empirical study on the effect of group awareness in CSCL environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(1), 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, N. (2001). Changes in the conception of learning as a function of experiencing novel learning environments [Doctoral dissertation, Haifa University]. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Carril, P. C., Hernández-Sellés, N., Fuentes-Abeledo, E. J., & González-Sanmamed, M. (2021). Factors influencing students’ perceived impact of learning and satisfaction in computer supported collaborative learning. Computers & Education, 174, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Beyond academic learning: First results from the survey of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, G. (2002). Technology and pedagogy: Why don’t we see the promised revolution? Educational Technology, 42(2), 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2023). Social and emotional learning. In International encyclopedia of education-perspectives on learning: Theory and methods (4th ed.). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon, I. (2021). Towards an integrative taxonomy of social-emotional competences. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 515313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunck, H. D. (1990). Introduction to the special section on motivation and efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryakova, T. Y. A., Morozova, L. B., Kochneva, E. M., Zharova, D. V., Kostyleva, E. A., & Kolarkova, O. G. (2016). Emotional stability as a condition of students’ adaptation to studying in a higher educational institution. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(15), 7486–7494. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S. S., & Jain, K. (2024). AI technologies for social emotional learning: Recent research and future directions. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 17(2), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, A. (2023). The impact of socio-emotional learning (SEL) on academic evaluation in higher education. Educatia, 21(24), 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Singh, S. K., & Mishra, N. (2025). Factors influencing student learning performance and continuous use of artificial intelligence in online higher education. Discover Education, 4, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer-Vital, S., & Finkelstein, I. (2024). Empowering teachers: Multicultural social and emotional learning (MSEL) among Arab minority teachers. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 11, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W., Grebennikova, V., Lisovskiy, A., Rakhimova, G., & Vasileva, T. (2024). AI-driven adaptive learning for sustainable educational transformation. Sustainable Development, 33(2), 1921–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedla, Y. G., & Chen, H. L. (2024). The impacts of computer-supported collaborative learning on students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 1487–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H., Yi, X., & Yeh, H. T. (2019). Learning-related soft skills among online business students in higher education: Grade level and managerial role differences in self-regulation, motivation, and social skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2008). Adolescents’ identity experiments on the internet: Consequences for social competence and selfconcept unity. Communication Research, 35(2), 208–231. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee, K. I., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2000). The multicultural personality questionnaire: Reliability and validity of self and other ratings of multicultural effectiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(3), 278–288. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, C. A., Presberry, C., & Louis, L. (2022). Examining teacher dispositions for evidence of (transformative) social and emotional competencies with Black boys: The case of three urban high school teachers. Urban Education, 57(2), 251–277. [Google Scholar]

- Won, S., Kapil, M. E., Drake, B. J., & Paular, R. A. (2024). Investigating the role of academic, social, and emotional self-efficacy in online learning. The Journal of Experimental Education, 92(3), 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., & Xiao, A. (2024). A structural equation model of online learning: Investigating self-efficacy, informal digital learning, self-regulated learning, and course satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1276266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).