Abstract

This study quantitatively examines the coeducation of television series and films between 1986 and 2023. This analysis has been facilitated by applying bibliometric analysis to scientific production using a relevant Web of Science (WoS) database. Analyses of 190 documents were conducted using quantitative and descriptive methods. These results present a multifaceted analysis of scientific production, evaluating historical development, the productivity of countries and institutions, authors’ productivity, and sources’ productivity. The study indicates that scientific production has grown exponentially in the last decade; this coincides with the emergence of video-on-demand platforms, multiscreen consumption, and equality policies. The conclusions must emphasize the significant role played by fiction series and film productions as socializing agents and their educational potential.

Keywords:

coeducation; bibliometrics; television production; cinema; edutainment; leisure; education 1. Introduction

Progress has been made in equality in recent years, in line with other societal developments; however, inequalities between men and women continue to exist. In this context, recent studies have demonstrated the role of how movies and fictional series transmit stereotypes, archetypes, and gender roles. From a pedagogical and coeducational perspective, new productions emerge that encourage reflection, including plots, conflicts, and even the subversion of stereotypes. Consequently, this presents an opportunity to promote informal learning in coeducation and enrich the formal educational objectives [1].

As a coeducational process, it entails an equal educational process for both sexes with equal rights and opportunities [2], i.e., it is synonymous with “equality in education”. Consequently, it aims to deconstruct the stereotypes and gender roles of an androcentric culture, which promotes social change [3], which is one of the most fundamental pillars of educational innovation [4]. Coeducation presents the challenge of identifying gender discriminatory behavior from a critical perspective [5] in order to eradicate sexism, gender inequality, and violence against women [4]. Among the first references to education inequality is made by Wollstonecraft (1792) in “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” with pedagogical proposals and a dialogical discussion with Rousseau’s work, Sophia’s Education. During the later centuries, gender-segregated education would lead to mixed education, considering the school a tool of cultural integration and neutrality. As a result of this situation, a coeducational school was established even though the educational model shared space and content. However, it stressed the male model as a universal model while making the female model invisible. “Coeducation” was initially conceived as teaching people together, regardless of race or gender, in the context of the American countercultural revolution of the 1970s [6]. Accordingly, the concept has frequently been used as a synonym for mixed education instead of segregated education [6]. Accordingly, the concept has frequently been used as a synonym for mixed education, as opposed to segregated education [6]. It is important to note that the first studies on coeducation took place in Anglo-Saxon countries in the 1970s. However, they developed rapidly in Spanish educational settings [3]. Nowadays, coeducation is recognized as a fundamental concept that transcends the context of the school environment. It may be encountered in both formal and informal educational contexts, including the media [4,7]. In this co-educational framework, crucial aspects such as roles, gender stereotypes and archetypes, the representation of women in audiovisual fiction, and emerging masculinities are also explored [8]. In this sense, it is essential to “co-educate the view” towards these contents in order to promote a more just and equitable society [7,9,10]. Media plays the role of socializing agents, influencing citizens’ worldviews, and transmitting attitudes, social norms, behaviors, beliefs, and cultural symbols to citizens [9,11,12,13].

The expansion of fiction series driven by the rise of Video On Demand (VOD) platforms and digital technologies has generated quality productions and provocative themes in social debates [14]. Numerous research studies highlight the importance of audiovisual fiction as an educational tool [1,15], thus promoting the concept of edutainment to foster social and individual transformation [16]. As a result of this shift in consumption, media convergence, and multiscreen consumption have been projected, resulting in synchronous and asynchronous dialogues about audiovisual products, particularly on social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter [8,17], highlighting the importance of transmedia strategies and active audience participation, particularly among teenagers.

The emergence of content platforms has contributed to the emergence of audiovisual fiction, which has resulted in a greater variety of thematic offerings for audiences. This phenomenon is framed within a context of increasing awareness of societal equality, the influence of feminist movements, and the emergence of a more egalitarian youth culture [18]. As a result, women are more often represented behind and in front of the camera, leading to significant changes in production [19]. According to contemporary research, fiction films and series depict some of society’s advances and achievements in terms of equality [20]; nevertheless, non-egalitarian gender roles, archetypes, and stereotypes continue to persist [7,10]. The same ability to influence the perpetuation of certain androcentric aspects allows for the construction of new egalitarian social imaginaries, which promote social transformation by challenging stereotypes and promoting reflection on gender equality and other social injustices [4]. Analyzing these productions in formal and informal educational settings provides opportunities for dialogue and reflection, encouraging critical thinking in the face of inequality and sexism. As a resource for coeducation, these productions can enrich educational contexts [1].

This article presents a bibliometric analysis of the production, distribution, and use of scientific information from publications using the Web of Science (WoS) platform [21]. Scientific production refers to researchers and scientists creating and disseminating innovative and original knowledge. A search equation was constructed based on a coeducational perspective on fiction series and films. A total of 190 documents were selected by analyzing their abstracts and selecting relevant sources for bibliometric analysis. This study aims to answer the following questions: What is the historical evolution of academic interest in coeducation related to fiction series and films? How does scientific production in the field of coeducation relate to fiction series and films, focusing on the production by country and institution as well as the contributions by authors and researchers? In light of this context, the main objective of this study is to describe a comprehensive vision of the scientific panorama related to coeducation and serial and film formats, highlighting the most influential authors, institutions, and countries and identifying the evolution of scientific production in this field. The specific objectives are:

- Examine a variety of scientific publications using the method of identification and examination.

- Investigate the evolution of scientific production on coeducation and its relationship with audiovisual media.

- Recognize relevant authorships and co-citation relationships.

- Determine which journals, institutions, and countries produce more noteworthy scientific work in this field.

- Visualizing the thematic trends prevailing in the research conducted.

Our research has a four-part structure. We exhaustively review the literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of coeducation and its relation to audiovisual production. In addition, we outline the methodology used and the pre-eminent results, concluding with a discussion and conclusions. By conducting a bibliometric analysis, we have identified emerging research areas, assessed the impact of publications, and identified crucial aspects for further investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

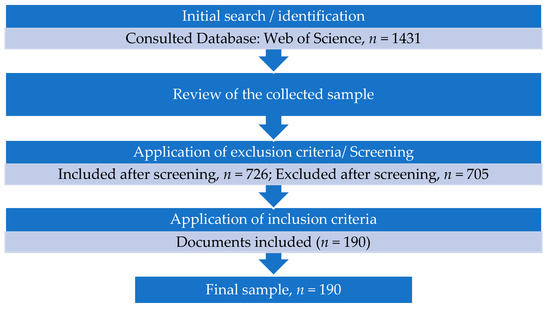

In recent years, there has been an increase in research on audiovisual fiction and coeducation due to the proliferation of television series and films. This study used a descriptive, retrospective, and quantitative analysis of scientific production about coeducation and its relationship to audiovisual productions between 1986 and 2023. According to the scientometric paradigm, a bibliometric approach is ideal for examining the quantitative aspects of scientific literature. This approach provides an objective and systematic vision of the multiple dimensions that appear in the scientific field, serving as a fundamental tool for understanding the field of study, providing information about a country or area of knowledge, and supporting the analysis of production and scientific performance [21]. A bibliometric design is appropriate for analyzing scientific production, detecting co-citation and coauthorship networks, and investigating evolutionary oscillations in the production process. Two phases comprise the research process. The first step of the study is to undertake a scientific mapping through a study of scientific publications obtained from one of the top scientific databases, the Web of Science Collection. For this purpose, the search equation in Table 1 was used, setting the date of the search until 5 October 2023, in 1431 publications. In the second step, we selected scientific texts according to predetermined exclusion and inclusion criteria, resulting in 190 documents for the final sample, as shown in a flow chart (see Figure 1). This is followed by an analysis of scientific evolution, which identifies four stages based on oscillations or variations (1986–2010, 2011–2015, 2016–2020, and 2021–2023). As a result, the publications have been reviewed in depth, delving into titles, summaries, and keywords and examining the content of the most important papers. The study’s second phase will involve an evaluative analysis of the scientific network and an analysis of the behavior of bibliometric indicators [22] to understand the relationship between countries, institutions, authorship, publications and sources, and the scientific production in each country. Moreover, we examine the networks of coauthorships, institutions, and co-citations of the most cited individuals.

Table 1.

Web of Science Search Equation (1986–2023). Note: Own elaboration.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of WoS sample sequencing. Own elaboration.

The VOSviewer 1.6.20 software helped export records in plain text format (txt), allowing the analysis, mapping, and visualization of scientific networks based on the normalization technique. Using this technique, the strength of association between nodes is determined by comparing the number of links from one node aij with the expected number of connections for all nodes in the network eij [23].

In bibliometric maps, authors, concepts, and areas of a scientific reality are graphically represented [24]. By interpreting these maps, we can identify clusters, notable nodes, and the connections between them, which provides a visual representation of the dynamics of our study object [25]. Clustering is the process of grouping the nodes in a scientific map so that we can determine the types of relationships between them (word, term, or document). Furthermore, the data were exported to CitNetExplorer, which allows the grouping of publications according to the linking of citations, enabling visualization of citation networks over time.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Scientific Production on Coeducation and Audiovisual Productions: A Chronological Analysis

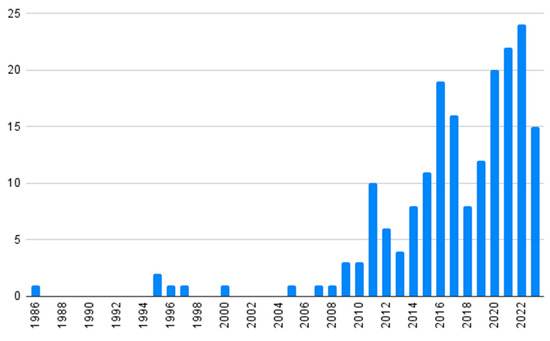

According to the analysis, scientific production increased continuously between 1986 and 2023, with 190 documents examined. In the period 1986 to 2005, only seven publications related to the subject of study were published. The data contrasts with subsequent years and later periods (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evolution of published scientific production (1986–2023). Own elaboration.

From 2006 to 2010, researchers added eight publications, but from 2011 to the present, they have exponentially increased their output, reaching 175 publications. They published the most in 2022, with 24 publications, followed by 2021 and 2020, with 22 and 20 publications, respectively. Considering the trends in publication and evaluation of scientific production and the approach to research on coeducation and audiovisual fiction, four distinct stages can be distinguished. Distinct characteristics emerge at each stage in response to changes in the socio-cultural and technological environment. The four periods of scientific production are 1986–2010 (15 documents), 2011 and 2015 (39 documents), 2016–2020 (75 documents), and 2021 and 2023 (61 documents). The evolution and influence of feminist movements, video-on-demand platforms, multiscreen technology, the 2030 Agenda, and the COVID-19 pandemic influenced scientific production during these periods.

In the first stage, between 1986 and 2010 (n = 15), only 15 publications were identified, indicating a lack of interest and awareness of coeducational perspectives. The emergence of the Fourth Feminist Wave in 2006 subtly increased scientific production. First, studies of a sociological nature examined the representation of women in serial and animated formats and the perception of equality in both areas. The first publication in the sample is Zemach and Cohen’s [26] “Perception of Gender Equality in Television and Social Reality”, which analyzes the perception of differences between social and symbolic reality on television. Furthermore, Thompson and Zerbinos [27] analyzed gender roles in 41 cartoons from the 1970s, demonstrating both a gradual improvement and persistent stereotyping. Several retrospective studies have examined the evaluation of equality in television formats, such as the representation of women scientists and their role in family and work situations [28]. In Galán-Fajardo [29] and Belmonte and Guillamón [7], the authors explore gender representation in Spanish fiction, emphasizing the importance of applying audiovisual coeducation to construct identity within the fiction context. Several subsequent studies have cited both articles as references.

The second stage from 2011 to 2015 (n = 39) is characterized by the emergence of VOD platforms as well as the increase in co-educational fiction literature. The most cited publication is “Female adolescents, sexual empowerment and desire: A missing discourse of gender inequity” (n = 139), by Tolman [30]. The author emphasizes the importance of empowerment in the area of sexual health among adolescents, proposing alternatives to formal education in this area. García-Muñoz and Fedele [31] conducted a study on teen series, i.e., series starring teenagers for a young audience, focusing on the content analysis of the series Dawson’s Creek, investigating the plots of its narrative. According to the authors, adolescent series are essential during identity construction. In addition to this study, we highlight a study by the same authors [32], which examines the labor roles of Spanish fiction in the 2009/2010 season. In terms of gender, the results show improvements, but the roles of men and women remain unequal in the workplace. Several investigations were influenced by these studies, including those by Menéndez [33] and Alvarez-Hernández et al. [34] The former examines the series “Con dos tacones y Mujeres” (TVE), whereas the latter examines the representation of women in Spanish films intended for teenage audiences. Through the visualization of different scenarios, Jarvis and Burr [35] demonstrate the transformative power of Buffy the Vampire Slayer as a means of stimulating critical learning by placing the viewer in an emotional and reflective experience regarding different moral circumstances. According to Chow-White et al. [36], fictional narratives themselves can facilitate debates about society through narrative critical reflections on power and gender inequality.

In the third stage (n = 75), feminist movements such as #MeToo and #Time’sUp are notable for denouncing harassment and sexist attitudes [18], and implementing the Sustainable Development Goals [15]. VOD platforms would gain momentum in 2016 with the creation of Netflix studios and the expansion of Netflix globally [37]. As a result, with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of subscribers on the various VOD platforms is expected to increase significantly [38]. The most cited studies highlight the gap between formal and informal education [39], as well as the importance of media literacy in sexual education, particularly in light of pornography and the objectification of women [40]. Researchers identify studies analyzing female representation in productions, emphasizing progress and highlighting persistent challenges, such as female under-representation or the hypersexualization of female roles [41]. On the other hand, Orthia and Morgain [42] analyze the Doctor Who series, confirming that the scientific staff shows a representative diversity, although stereotypes based on androcentrism are evident. Studies examine new masculinities, illustrating a transformation of roles and stereotypes, challenging hegemonic masculinity based on the absence of care and conceptual projection regarding romantic love [43,44]. In different studies, the coeducational potential of fiction series has been examined. Bonavitta and De Garay [45] and Morejón-Llamas [46] examine gender representation in fiction such as La Casa de Papel, Rita, Gossip Girl and Get Even, highlighting its influence on adolescent identity construction. Gil-Quintana and Gil-Tévar [8] analyze the coeducational potential of the Las del Hockey series, examining issues such as consent, women’s sports, and sexual abuse. Gavilán et al. [47], examine the perception of females of different generations regarding the evolutionary changes in fiction series, demonstrating a reduction in gender stereotypes and the increasing visibility of social problems (harassment, reconciliation, and family diversity). Children’s identity is shaped by Disney films, with the transmission of values influenced by them, according to Osuna-Acedo, Gil-Quintana, and Cantillo-Valero [48]. In this regard, the concept of “transcultural fiction” emerges, which refers to productions that communicate cultural diversity, create debates and reflections, and facilitate the creation of a more equitable social imagination. A study conducted by Chang and Ren [49] investigated Knallerfrauen’s impact on Chinese women and its contribution to the empowerment of women.

In the fourth stage, from 2021 to 2023 (n = 61), there is an increase in scientific production, particularly the works of Marcos-Ramos and González-De Garay [50] as well as Garrido and Zaptsi [18]. It focuses on the representation of women on screen, analyzing stereotypes, archetypes, gender roles, and their impact on education. Research in this area highlights the conquest of different areas of female representation, such as STEAM education, identifying positive changes in female roles played in films such as Chernóbil [51]. Several studies have examined the lack of ambition and female representation in the characters [52]. Other analyses have discussed the coeducational aspects of television series, such as La Otra Mirada [53]. Studies have examined series such as Sex Education as educational tools to assist adolescents in constructing their sexual identities through viewing and discussion [20,54], as well as audience reactions to sexual consent in the series Las del Hockey [17]. Researchers examine productions about the construction of social imaginaries, exploring the cross-cultural influences of narrative frames in India and the implementation of egalitarian discourses in conservative settings [55]. In addition, Chinese television drama is examined critically from the perspective of globalized beauty standards [56]. In addition to innovative proposals for coeducational analysis, we also found proposals for evaluating Sustainable Development Goals in adolescent fiction [15], designing a coeducational analysis table [20], and integrating Artificial Intelligence in series to address gender inequality and stereotypes [57,58].

3.2. Scientific Production of Countries and Institutions

Analyzing the scientific productivity by nation (see Table 2), Spain, the United States, and Australia lead in the number of publications relating to the topic of study. Spanish publications receive the highest number of citations in our analysis. A total of 45 countries are included in the sample, 15 of which are members of the European Union, highlighting the influence of Anglo-Saxon studies and the equality policies established in Western countries.

Table 2.

Top ten countries in document production. Own elaboration with WoS (2023).

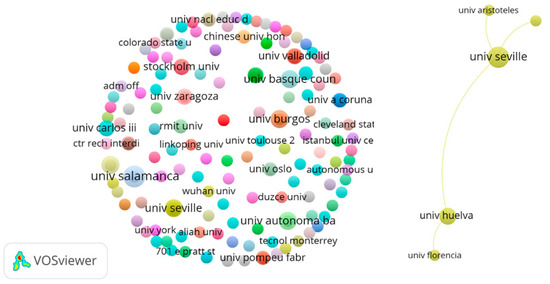

Regarding institutions with the most publications and citations (see Table 3), we have 195 institutions, including universities, institutes, and public organizations. The University of Salamanca has been the most prolific (n = 8). The Autonomous University of Barcelona follows with four publications, followed by the University of Seville, the University of Valencia, the University of Burgos, and the University of the Basque Country. The most cited institution is the University of Salamanca (n = 99), followed by Amsterdam University (n = 71).

Table 3.

Top ten Institutions with the most publications and citations. Own elaboration with WoS (2023).

The co-authorship network analysis reveals that 195 organizations linked to the study are involved. There are 130 clusters, of which 126 are made up of institutions that have no links with the others, as can be seen on the left side of Figure 3. On the other hand, there are 4 clusters with 5 connected institutions: the University of Huelva, the University of Florence, the University of Seville, the University of Thessaloniki, and the University of Cadiz (right side of Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Institutional network relating to co-authorship. Prepared by the authors using VOSviewer (2023).

3.3. Authored Scientific Production

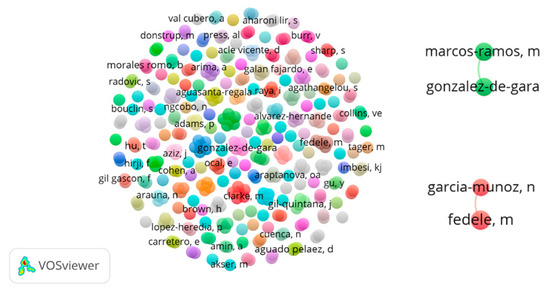

Regarding producing the most publications in the extracted sample (Table 4), Fedele leads the ranking with three publications. Media literacy and diversity are significant focuses in their research on audiovisual media and society. According to their research, we can identify two archetypes of love and gender in adolescent series Por 13 razones, Élite and Sex Education. Then, we find two people with two publications, including doctors González-de Garay and Marcos-Ramos, both co-authors of numerous studies. Finally, we quote Lacalle, director of the Observatory of Spanish Fiction and New Technologies. There is no correlation between the authors with the most publications and the most cited authors. Tolman’s article “Female adolescents, sexual empowerment and desire: A missing discourse of gender inequality” received 135 citations. Following her is Filiol (n = 90), from the University of Minho.

Table 4.

Author with the most publications and citations. Own elaboration with WoS (2023).

Coauthorship analysis allows us to identify research collaborations (see Figure 4). Among the 328 people with publications, the analysis identifies only seven coauthorship clusters with two or more publications. The two largest clusters (n = 2) are Marcos-Ramos and González-de Garay of the Audiovisual Content Observatory and Fedele and García-Muñoz from the University of Barcelona.

Figure 4.

General co-authorship network and more prominent co-authorship networks. The authors prepared this figure using VOSviewer (2023).

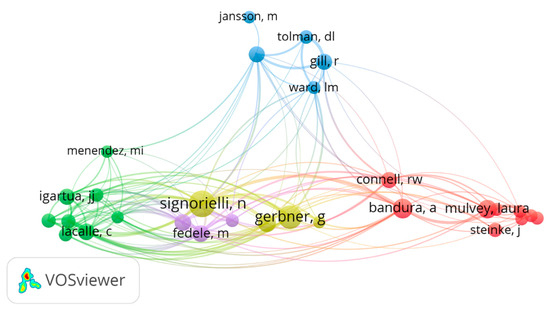

Using the co-citation analysis (Figure 5), we identify the authors most frequently cited by the research in our sample, thus supporting the theoretical foundation for our study. The analysis identified 5703 references, with 29 having nine or more co-citations. Using the VOSviewer program, the analysis grouped these references into five clusters and assigned each cluster a color (red, yellow, blue, green, purple). A network led by a red cluster, composed of nine individuals, has been identified, highlighting Mulvey (n = 20) and Steinke (n = 12), key figures in women’s cinema and media literacy. We also find Foucault (n = 22), one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, and Bandura, the father of the “social learning theory”. In the second largest cluster (n = 8), in green, We find that one of the most prominent references in audiovisual fiction and coeducation is Belmonte (n = 11) from the University of Barcelona. Carlos III University’s Galán-Fajardo (n = 12) is also a leading authority in gender construction, adolescents, and audiovisual fiction. Additionally, we find Igartua (n = 15), head of the Audiovisual Content Observatory, and Lacalle (n = 16), director of the Spanish Fiction and New Technologies Observatory. As a result of the analysis of the five clusters, yellow dominates the center of the research (n = 4), highlighting references from sociology and gender studies. Additionally, we identify Gerbner and Signorielli, the proponents of the “cultivation theory”; and we contact Lauzen, the director of the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film. The size of the nodes of the four individuals mentioned suggests that they have the highest degree of citations and connections. A blue cluster (n = 5), located at the top of the map, is devoted to feminism and sociology research. In terms of equality education, McRobbie, Tolman, Jansson, and Gill are experts in these fields. The last cluster (purple), with three authors, is closely related to the yellow and green clusters. We observed authors in the field of audiovisual coeducation, including Fedele (n = 16) and Masanet (n = 16).

Figure 5.

Co-citation network for authorship. Prepared by the authors using VOSviewer (2023).

3.4. Scientific Production of the Most Cited Publications

Nineteen publications with more than 16 citations have been identified (Table 5). The paper with the highest number of citations is “Female Adolescents, Sexual Empowerment and Desire: A Missing Discourse of Gender Inequity” [30] (n = 135) by Dr. Tolman (City University of New York), published in the journal Sex Roles. This study examines sexual education for adolescents and offers suggestions for media activism. The second most cited publication is “Gender-roles in animated cartoons. Has picture changed in 20 years” by Thompson and Zerbinos [27] concerning gender representation in 41 cartoons. The third most cited publication is the study by Pereira et al. [38], which examines the educational impact of media and audiovisuals on adolescents. Among the 69 citations, we find Vandenbosh and Van Oosten [40] who examine possibilities for media education about pornography.

Table 5.

Most cited publication. Own elaboration with WoS (2023).

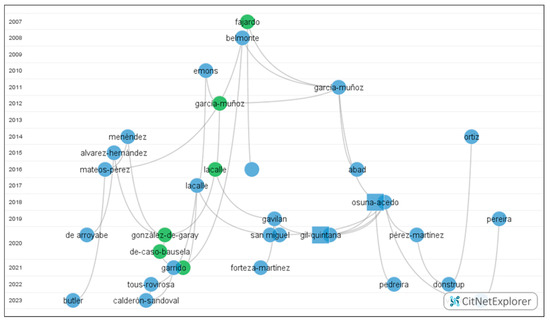

One of this study’s findings is the influence of Belmonte and Guillamón [7] and Galán-Fajardo [29] on Spanish studies, the most influential research in audiovisual coeducation. The impact of both articles can be noted in the cluster of influence shown in Figure 6, highlighting studies that concern gender representation and content analysis.

Figure 6.

Cluster of influence. Own elaboration with CitNetExplorer (2023).

3.5. Scientific Production of Sources

The sample consists of 190 scientific productions. One hundred eighty-eight journals are included in the study, making up 98.94% of the sample. The remaining two publications are book chapters. As shown in Table 6, the sources with the most significant number of documents have high H indexes (measuring the impact of publications in a journal) and a high journal quartile (indicating that a journal is critical within its respective field of study). Among the journals, Feminist Media Studies (n = 13) stands out, focusing on feminist and media studies with a particular emphasis on film and new technologies. The Spanish journal Comunicar, specializing in education and communication, is ranked second. In addition to the ranking, we find Sex Roles (n = 7), with an H-index of 135 that complements the ranking. It is an open access journal that publishes articles on beliefs, bonds, and representations from a gender perspective. Three of the journals mentioned above rank in the first quartile (Q1), i.e., they are among the top 25% of journals in terms of impact factor. There is a predominance of British journals in the ranking, along with a few Spanish journals and one American publication.

Table 6.

Publication of scientific publications. Own elaboration with WoS (2023).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings from this research provide a more profound and evolutionary perspective on scientific production related to coeducation about audiovisual fiction, marking a milestone as the first study in bibliometric analysis of this subject. In the study, we examined 190 documents signed by 331 individuals from 195 institutions in 45 countries. A significant aspect of the research is the predominant usage of magazines classified in the upper quartiles (Q1), which reveals two relevant findings: Firstly, impact magazines are interested in examining fiction series and films from a coeducational perspective, and secondly, they adhere to quality standards in conducting these investigations. According to the findings of this study, there has been an exponential change in scientific production over the period 2016–2023, with up to 64.88 percent of documents analyzed in this study. Despite the quantitative increase in production in topics related to audiovisual coeducation as a potential educational resource, there is a lack of specific studies that specifically address education with audiovisual fiction from a literal perspective of «coeducation».

Several factors have contributed to this increase, including promoting and expanding streaming platforms [37], spreading audiovisual fiction, and implementing policies to enhance equality [63].

The rise of VOD platforms has significantly increased the scientific interest in topics related to coeducation in audiovisual fiction [14]. These platforms have played a crucial role in broadening access to a diverse range of content, thereby enhancing the dissemination of productions that cover coeducation-related topics such as feminism, character representation, gender roles, and stereotypes, as well as social imaginaries and stereotypes [50]. The diversity of narratives available on these platforms presents an opportunity to use them as a teaching tool in both formal and informal education. Moreover, the global reach of these platforms amplifies the impact of the topics addressed and promotes critical reflection on roles and stereotypes [8,9].

The majority of publications focus on fiction series as a result of their exponential growth on digital platforms. A coeducational view of production is made possible by the thematic diversity and the rupture of traditional discourses [45,63]. There is increasing interest in programs focused on adolescents and children’s animation, underscoring the importance of incorporating a coeducational perspective into various educational levels and niches [9]. Further, “new masculinities” have been discussed to redefine traditional masculinity roles, challenge entrenched stereotypes, and encourage alternative forms of masculinity [43,64]. A variety of studies have also been observed from the teaching and research praxis, proposing the importance of media literacy to emancipating a critical perspective on gender roles, stereotypes, and archetypes [8], taking advantage of the educational opportunity for reflection and critical thinking that exists at different educational stages [10,12,65].

As part of broader sociocultural transformations, the implementation of equality policies has sparked scientific interest, the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals, and increased awareness of the importance of fair representation in the media [15,66].

Consequently, since 2016, the number of publications related to coeducation has increased by feminism movements such as #MeToo and Time’s Up [18]. These movements have played a crucial role in making gender issues visible in television series and films and creating an ideal environment for analyzing gender representation in audiovisual works. Particularly in the fourth-wave feminism movement, media representation has been emphasized as an essential issue [53,67]. As society has become increasingly concerned about gender inequalities, scientific production has increased that explores the use of audiovisual fiction as a coeducational resource. This interest has led researchers to conduct additional studies on how audiovisual narratives perpetuate or challenge gender stereotypes and roles, aiming to reconfigure social imaginaries and promote more egalitarian representations [45,48].

After identifying and analyzing the scientific mapping of the topic, conclusions have been drawn based on thematic trends supported by numerous publications relating to female representation, both in prominence and presence in audiovisual fiction. However, women continue to play secondary roles in a large proportion of the series, even though the more significant presence of women may not necessarily guarantee an egalitarian representation with a coeducational perspective [67]. A content analysis of audiovisual fiction based on stereotypes, archetypes, and gender roles allows us to consider coeducation from a critical perspective on personal, work, and relational dimensions. These studies highlight the need to identify and address inequalities [10]. The integration of feminist perspectives in edutainment has strengthened the importance of coeducating as a means to promote gender equality in both formal and non-formal learning environments [1,8,15,66].

Regarding scientific distribution, the leading countries are primarily European and Anglo-Saxon, reflecting greater awareness of the subject. Studies published by Spanish universities stand out, in line with the ramifications, influence, and continuity of Galán-Fajardo [29] and Belmonte and Guillamón [7] studies on gender representations in Spanish fiction and the potential of this literature for coeducation. Meanwhile, emerging countries like India or China are exploring new social imaginaries and the influence of Western culture. Contemporary authors from Spanish universities, such as Fedele, Lacalle and Masanet, stand out in the exhibition. The work of leading authors in sociology, feminist film studies, feminism, media literacy, and education forms the theoretical background for the publications.

From a coeducational perspective, this research has revealed the situation of audiovisual fiction, contributing to knowledge of this field, which has been little studied until now, and urging future reflection by the scientific and educational communities to continue with research from an egalitarian perspective.

5. Recommendations and Limitations

We propose several recommendations for researchers and institutions based on the issues raised during the discussion and the conclusions reached.

Firstly, exploring scientific literature in additional databases to WoS, along with interdisciplinary approaches, enables us to examine a wider variety of research and perspectives from multiple fields of study, enabling us to gain a more global and interdisciplinary perspective. A crucial aspect of the research process is identifying research or studies published in journals ranked in the lower quartiles. Furthermore, it is essential to stimulate collaboration between researchers and universities in different countries to enrich perspectives and methodologies, thus facilitating the creation of a more diverse and solid network of co-authorships.

A second line of recommended research is analyzing the influence of policies on the production and representation of gender in audiovisual fiction. Research on educational policies will provide valuable information to the researcher regarding their effectiveness and areas for improvement. Consequently, conducting a thorough analysis of the European context is important.

From a coeducational perspective, it is essential to design and evaluate media literacy programs that utilize audiovisual fiction as a means of promoting critical thinking and reflection about roles, archetypes, gender stereotypes, etc. The implementation of these programs must take place at different educational levels, promoting inclusive and equitable education from an early age, particularly in the context of childhood and adolescence.

Our study is limited because we used samples from a single database, Web of Science (WoS), which may have limited its diversity and scope. Furthermore, we observed limited cooperation between authors from different universities or institutions represented in the sample. By using other databases, an expanded network of co-authorships and collaborations on this topic can have been explored, providing a broader perspective on the topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.T. and J.G.Q.; methodology, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and J.J.H.R.; software, S.G.T., J.J.H.R. and E.G.B.; validation, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and J.J.H.R.; formal analysis, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and J.J.H.R.; investigation, S.G.T. and J.G.Q.; resources, S.G.T., J.G.Q., J.J.H.R. and E.G.B.; data curation, S.G.T., J.G.Q., J.J.H.R. and E.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and E.G.B.; writing—review and editing, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and E.G.B.; visualization, S.G.T., J.G.Q., J.J.H.R. and E.G.B.; supervision, S.G.T., J.G.Q. and J.J.H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The research is part of Simon Gil Tévar’s doctoral student process at the UNED International Doctoral School (EIDUNED).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santaella, E.; de Pinedo, C.; Martínez-Heredia, N. Analysis of the presence of older women in Spanish television series. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, A.; Ruíz, P.J. Educational treatment of coeducation and gender equality in the school context and in space in Physical Education. Aula Abierta 2009, 37, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, M. Coeducation, Commitment to Freedom, 2nd ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Llaneza, M. Coeducar es innovar. Particip. Educ. 2020, 7, 62–75. Available online: https://bit.ly/43ZYUco (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Sánchez-Torrejón, B. Coeducación en la formación del profesorado: Herramienta para la prevención de la violencia de género. Aula Encuentro 2021, 22, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.L. Fair and Tender Ladies versus Jim Crow: The Politics of Co-Education. Am. Educ. Hist. J. 2010, 37, 407–417. Available online: https://bit.ly/3NM6MIs (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Belmonte, J.; Guillamón, S. Co-educate the gaze against gender stereotypes on TV. Rev. Comun. 2008, 31, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Quintana, J.; Gil-Tévar, S. Fiction series as a means of co-education for adolescents. Case study: The Hockey Girls. Fonseca J. Commun. 2020, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida, R.; Heras, T. Gender analysis of children’s animated films as a resource for a co-educational school. Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2021, 21, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneleuterio-Temporal, E.; Soler-Campo, S. Gender stereotypes in audiovisual productions: Design and validation of the analysis table EG_5x4. Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2022, 64, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacalle, C. Gender and spectator experience. Reception analysis. In Television Viewer and Audiovisual Reception in Spain, 2nd ed.; Duran, J., Carandell, Z., Eds.; Éditions Orbis Tertius: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, B.; Morales, N. Hollywood romantic cinema of the first decade of the 20th century XXI: Analysis from the gender perspective. Fonseca J. Commun. 2020, 20, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-del Castillo, A.; Arregi-Orue, J.I. Girls don’t want to be princesses anymore! Informal education, toy advertising and the construction of gender in childhood. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2023, 42, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla-Martínez, B.; Mondelo-Martínez, E. Serial teenagers. Young protagonists in television fiction. Fonseca J. Commun. 2020, 21, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Monreal, S.; Lozano Delmar, J.; Araque-Padilla, R.A. Evaluating the presence of sustainable development goals in digital teen series: An analytical proposal. Systems 2020, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.; Vega-Casanova, J. Identification with characters, elaboration, and counterarguing in entertainment-education interventions through audiovisual fiction. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Sandoval, O.; Villegas-Simón, I.; Medina-Bravo, P. Debate over sexual consent in the seen The Hockey Girls: Reactions from Instagram audiences. Educ. Sex. Soc. Sex. Learn. 2023, 24, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, R.; Zepsi, A. Archetypes, Me Too, Time’s Up and the representation of diverse women on TV. Comun. Rev. Científica Iberoam. Com. Educ. 2021, 68, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous-Rovirosa, A.; Meso, K.; Simelio, N. The representations of woman’s roles in Television Series in Spain. Analysis of the basque and catalan cases. Commun. Soc. 2013, 20, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donstrup, M.T. Feminism in Amazon Prime fiction series. Géneros Rev. Multidiscip. Estud. Género 2022, 68, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Górriz, V.; Tomás-Casterá, V. Bibliometrics in the evaluation of scientific activity. Hosp. Home 2018, 2, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skute, I. Opening the black box of academic entrepreneurship: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2019, 120, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, A.M.; Romero-Riaño, E. The role of gamification in environmental awareness: A bibliometric review. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2020, 30, 161–185. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3764 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Gúzman, M.V.; Trujillo, J.L. Bibliometric maps or maps of science: A useful tool for developing metric studies of information. Biblioteca Univ. 2013, 16, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemach, T.; Cohen, A. Perception of gender equality on television and in social reality. J. Broadcast. Elect. Media 1986, 30, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.L.; Zerbinos, E. Gender roles in animated cartoons: Has the picture changed in 20 years? Sex Roles 1995, 32, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J.; Long, M. A lab of her own? Portrayals of female characters on children’s educational science programs. Sci. Commun. 1996, 18, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Fajardo, E. Construction of gender and television fiction in Spain. Comun. Rev. Cient. Com. Educ. 2007, 14, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, D.L. Female adolescents, sexual empowerment and desire: A missing discourse of gender inequity. Sex Roles 2012, 66, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, N.; Fedele, M. Youth television series: Plots and conflicts in a “teen series”. Comun. Rev. Cient. Com. Educ. 2011, 19, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, N.; Fedele, M.; Gómez-Díaz, X. The occupational roles of television fiction cha-racters in Spain: Distinguishing traits in gender representation. Commun. Soc. 2012, 25, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, M.I. Put a woman in your life: Self-produced fiction on TVE (2005–2006). Área Abierta 2014, 14, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Hernández, C.; de Garay-Domínguez, B.G.; Frutos-Esteban, F.J. Gender representation in contemporary Spanish teen films (2009–2014). Rev. Lat. Commun. Soc. 2015, 70, 934–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C.; Burr, V. The transformative potential of popular television: The case of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. J. Transform. Educ. 2011, 9, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow-White, P.A.; Deveau, D.; Adams, P. Media encoding in science fiction television: Battlestar Galactica as a site of critical cultural production. Media Cult. Soc. 2015, 37, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Telang, R. Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strange-Reséndiz, I.L. The uncertainty of movie theaters and the growth of streaming in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sintaxis 2020, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Fillol, J.; Moura, P. Young people’s learning with digital media outside of school. From informal to formal. Comun. Rev. Cient. Iberoam. Com. Educ. 2019, 58, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbosch, L.; Van Oosten, J.M. The relationship between online pornography and the sexual objectification of women: The attenuating role of porn literacy education. J. Commun. 2017, 67, 1015–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, C.; Anastasio, P. Fewer, younger, but increasingly powerful: How portrayals of women, age, and power have changed from 2002 to 2016 in the 50 top-grossing US films. Sex Roles 2019, 80, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthia, L.A.; Morgain, R. The gendered culture of scientific competence: A study of scientist characters in Doctor Who 1963–2013. Sex Roles 2016, 75, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Click, M.A.; Miller, B.; Behm-Morawitz, E.; Aubrey, J.S. Twi-dudes and Twi-guys: How Twilight’s male fans interpret and engage with a feminized text. Men Masculinities 2016, 19, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araüna, N.; Tortajada, I.; Willem, C. Portrayals of Caring Masculinities in Fiction Film: The Male Caregiver in Still Mine, Intouchables and Nebraska. Masculinidades Cambio Soc. 2018, 7, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavitta, P.; De Garay, J. ‘La casa de papel’, ‘Rita’ and ‘Merlí’: Between new narratives and old patriarchies. Investig. Fem. 2019, 10, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrejón-Llamas, N. Gender stereotypes and cyberbullying in teen fiction series: A comparative analysis of Gossip Girl, Pretty Little Liars, and Get Even. Fonseca J. Commun. 2020, 21, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, D.; Martínez-Navarro, G.; Ayestarán, R. Women in fiction series: Women’s point of view. Investig. Fem. 2019, 10, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Acedo, S.; Gil-Quintana, J.; Cantillo-Valero, C. The construction of children’s identity in the Disney World. Rev. Lat. Commun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1284–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Ren, H. Empowerment through craziness: The German TV series Knallerfrauen and its female viewers in China. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2016, 19, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Ramos, M.; Gonzalez-De-Garay, B. New Feminist Studies in audiovisual industries: Gender representation in subscription Video-On-Demand Spanish TV series. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tunç, A. A woman scientist in pursuit of truth: A rising trend of representation with Chernobyl. J. Pop. TV 2021, 9, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caso, E.; González-de Garay, B.; Marcos-Ramos, M. Gender representation in general Spanish television series broadcast in prime time (2017–2018). Prof. Info 2020, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forteza-Martínez, A.; Conde, M.A. Education and women in educational series: The other view as a case study. Investig. Fem. 2021, 12, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, C.; El-Khoury, J. Local absence, global supply: Lebanese youth, sexual education, and a Netflix series. Sex Educ. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangam, D.; Vaidya, G.R.; Subramanian, G.; Velusamy, K.; Selvi-Govindarajan, K.; Park, J.Y. The Portrayal of Women’s Empowerment in Select Indian Movies. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 81, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gu, Y. Television, women, and self-objectification: Examining the relationship between the consumption of female TV dramas and sexism, the internalization of beauty ideals, and body surveillance in China. Glob. Media China 2023, 8, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digeon, L.; Amin, A. Transnational TV series adaptations: What Artificial Intelligence can tell us about gender inequality in France and the US. Media Lit. Acad. Res. 2021, 4, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Upreti, A.; Kurtaran, M.; Ginter, F.; Lafond, S.; Azimi, S. Identifying gender bias in blockbuster movies through the lens of machine learning. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieler, M.; Kohlbacher, F.; Hagiwara, S.; Arima, A. Gender Representation of Older People in Japanese Television Advertisements. Sex Roles 2011, 64, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Using film in teaching and learning about changing societies. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2011, 30, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-Bravo, I.; Sánchez-Labella, I.; Durán, V. The construction of the teenager profile on Netflix Tv Shows, 13 Reasons Why and Atypical. Commun. Medios 2018, 37, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacalle, M.R. Representación de Workingwomen en Spanish Television Fiction. Comun. Rev. Cient. Com. Educ. 2016, 24, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado-Ruiz, C. The other view: The critical review of Spanish series and research from gender studies (2000–2021). In Analysis of Spanish Television Fiction, 1st ed.; Cascajosa, C.J., Meteos-Pérez, J., Eds.; Éditorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cascajosa, C.; Mateos-Pérez, J. Introduction. Research on Spanish television series. In Analysis of Spanish Television Fiction, 1st ed.; Cascajosa, C.J., Meteos-Pérez, J., Eds.; Éditorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zashikhina, I. Cinema feminist agenda as a source for gender studies. Media Educ. Mediaobrazovanie 2022, 18, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junguitu-Angulo, L.; Osuna-Acedo, S. She, her Fostering gender equality (SDG 5) through audiovisual fiction. Int. Vis. Cult. Rev. 2024, 16, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, C.; Cortés-Quesada, J.A. Feminist narratives on streaming content platforms: Content analysis of Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+. Hist. Commun. Soc. 2022, 27, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).