Abstract

This study examined the impact of a targeted educational intervention on enhancing grit and critical thinking skills among 10-year-old primary school students in rural Chile. The intervention, involving 153 students from six public schools, used a language classroom model with structured reading activities. Grit and critical thinking were measured pre- and post-intervention. Results showed improvements in the intervention group. The intervention’s effectiveness was consistent across genders. The findings suggest that structured, student-centered educational strategies can enhance grit and critical thinking in primary students. Further research is needed to generalize the results to different settings and age groups.

1. Introduction

The skills needed for today’s students to succeed in their future working lives are known as 21st-century skills. These are essential for tackling real-life problems and adapting to a rapidly changing world, leading to improved living conditions [1]. Educational systems are increasingly emphasizing these skills to prepare individuals for contemporary challenges. Teachers play a crucial role in promoting these skills in the classroom, reflecting the demands of globalization [2]. Therefore, it is essential to train teachers in models and methods that effectively cultivate 21st-century skills [3]. Enhancing these skills is vital for improving students’ competencies across various domains and achieving global competitiveness [4]. These skills enable individuals to apply their knowledge practically, fostering flexibility and achievement in today’s environment [5].

Critical thinking is a crucial 21st-century skill. According to the American Philosophical Association, an ideal “critical thinker” is curious, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded, and knowledgeable, capable of understanding multiple viewpoints [6,7]. People with strong critical thinking skills are more likely to correct flaws in their cognitive processes or decision-making [8]. In the digital age, with abundant information and rapidly developing technology, it is vital to critically assess and analyze content [9]. For students, critical thinking is essential for developing skills needed for future societal progress [10]. As online technological advancements continue, the importance of critical thinking will grow, requiring individuals to adapt to job automation and evolving work methods [11].

Critical thinking is essential for adapting and learning in educational settings [12]. It involves examining and assessing information and is positively associated with educational achievements [13], problem-solving ability [14], and academic performance [15]. Additionally, critical thinking is linked to metacognitive skills [16], reflective thinking [17], and scientific literacy [18]. Developing critical thinking skills enhances students’ overall cognitive abilities, enabling them to navigate complex learning environments more effectively [19].

Critical thinking is widely recognized as an essential skill in education and should be nurtured in young individuals during their developmental years [20]. Educators play a crucial role in developing students’ critical thinking abilities. Key factors in teaching critical thinking to elementary students include enhancing educators’ professional expertise and using pedagogical approaches that cultivate these skills [21]. Additionally, creating a classroom environment that encourages questioning and open discussion can further support the development of critical thinking [22].

Grit, defined as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals” [23,24] has become increasingly recognized as a critical attribute for success in the 21st century [25]. This trait is vital for adapting to new environments and thriving in various aspects of life, including education and personal development. In the realm of academic achievement, grit plays a fundamental role by fostering the development of essential skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving [26]. These capabilities are indispensable for navigating the challenges of modern educational settings and beyond.

Grit enhances students’ ability to engage positively with their academic work, leading to better emotional outcomes and the development of advanced computational thinking skills [27]. It also promotes well-being and contentment, even in the face of adversity, by supporting individuals to persevere and maintain focus on their long-term objectives [28]. Additionally, by cultivating grit, educators can significantly bolster students’ resilience and motivation, which are key drivers of educational success and overall personal achievement [29]. Thus, grit is not merely beneficial but essential in helping students achieve their full potential and prepare for future challenges.

Students with higher levels of grit are more likely to maintain consistent effort over time, leading to better academic performance [30]. Gritty students are also more engaged and motivated, fostering deep learning and a willingness to tackle difficult tasks [31]. Grit helps students overcome obstacles and recover from failures, enabling persistence through challenging coursework and exams [29]. Research consistently shows a positive correlation between grit and academic achievement across various educational levels, emphasizing the importance of non-cognitive factors [32]. This correlation underscores the significance of fostering perseverance in students to enhance academic outcomes [33].

When examining the relationship between grit and critical thinking, it is essential to recognize that grit is primarily associated with sustained effort and enduring interest, rather than inherent cognitive ability [34]. This distinction highlights that grit complements critical thinking by fostering perseverance and passion in the face of challenges, thereby supporting the consistent application of critical thinking skills over time [35]. Grit encourages students to tackle complex problems persistently and patiently, even when solutions are not immediately apparent, which is crucial for mastering higher-order thinking skills [36].

Understanding how experiential learning—where learners gain knowledge through their own experiences—interacts with grit can help educators devise strategies that boost students’ cognitive skills while also strengthening their resilience and determination. Grit, characterized by perseverance, plays a crucial role in the learning process and can be a key factor in enhancing educational success among learners [37].

Additionally, creating an educational setting that equally values persistence and performance can motivate students to view challenges as opportunities for growth rather than threats to their self-esteem or signs of failure. This perspective encourages them to see their abilities as expandable through effort and perseverance, potentially leading to heightened motivation and a greater chance of success in complex cognitive tasks [38]. Such programs can equip students with the skills to plan for the long term, manage their emotions and reactions to setbacks, and consistently apply critical thinking skills even in the face of initial difficulties.

Creative and critical thinking are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Critical thinking focuses on analyzing, evaluating, and refining ideas, while creative thinking is dedicated to generating new, innovative ideas and approaches. The problem-solving process typically initiates with creative thinking, during which a variety of ideas and solutions are brainstormed. This phase is succeeded by critical thinking, where these ideas are methodically evaluated for their practicality and relevance [39]. In educational settings, it is essential to instruct students on how to effectively balance both creative and critical thinking. Creative thinking encourages students to explore and innovate, and critical thinking provides them with the tools to refine their ideas and make informed decisions [40].

Rural educational settings often face unique challenges, such as limited access to resources, less exposure to diverse educational opportunities, and higher rates of economic disadvantage. However, fostering grit and critical thinking skills can significantly enhance academic performance in these environments.

While grit and critical thinking are essential for all students, their development is highly significant in rural educational settings. Students in rural areas often face unique challenges stemming from limited resources and opportunities compared to their urban counterparts [41]. Grit is especially crucial for rural students striving to succeed academically despite these obstacles [42]. Developing critical thinking skills further enhances their ability to analyze and solve problems effectively, which is vital for overcoming the constraints imposed by their environment. Additionally, fostering a supportive community and providing access to diverse educational resources can help mitigate these challenges and promote the holistic development of rural students [43].

Moreover, fostering critical thinking skills equips rural students with the ability to analyze information, solve problems, and make informed decisions within their resource-constrained environments [21]. It is relevant to create student-centered models to nurture critical thinking in rural classrooms, further supporting the development of these essential skills [44]. Educational initiatives that implement interventions that target the development of grit and critical thinking can contribute to narrowing the persistent gap in elementary education quality between urban and rural areas [45]. Therefore, exploring strategies for effectively cultivating these vital non-cognitive and cognitive skills among students in rural contexts is imperative.

The present study aims to investigate the impact of a targeted intervention on enhancing grit and critical thinking levels among primary school students in rural settings. Focusing on this underserved population can yield insights into tailoring educational approaches to their unique needs and equipping them with the resilience and higher-order thinking abilities necessary for overcoming challenges and realizing their full potential.

Given the importance of grit and critical thinking, particularly in rural settings, this article seeks to address the research question: To what extent does a targeted educational intervention affect the development of grit and critical thinking in rural elementary school students?

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

This study adopted a quasi-experimental design to assess the impact of a specific class methodology on students’ grit and critical thinking skills. A quasi-experimental approach was necessary as it was impractical to randomly assign students to different groups due to the established structure of classroom groups. Instead of random assignment, students were grouped based on age and school level.

The research employed a pre-test–post-test design to evaluate the effectiveness of the educational intervention on grit and critical thinking levels among 10-year-old students in a rural area of Chile. The pre-test was conducted prior to the intervention and the post-test followed its completion, allowing for a comparison of outcomes before and after the methodology was implemented.

2.2. Participants

In the experimental group, the study involved 153 students in the fifth year of primary school in Chile. The students belonged to six public schools in the rural area of the Elqui Valley.

We chose this age range because 10-year-old children are located in the concrete operational stage [46], which is characterized by the presence of logical reasoning, deductive thinking, the ability to reverse actions, understanding cause-and-effect relationships, the capacity for classification, transitive reasoning, and the absence of egocentrism [47].

In the control group, the study involved 93 students from a public school in the same Chilean rural area (see Table 1). These students shared similar social and cultural traits with those in the experimental group, and their ages were also comparable to those in the experimental group.

Table 1.

Participant demographics: control group, experimental group, and teachers.

2.3. Intervention

The intervention consisted of implementing a language classroom model methodology that promotes critical thinking and grit. The teachers were provided with the necessary resources to adhere to the suggested model for conducting these classes.

The primary activity of the model involves reading texts during class time (a 90-min class module). The model, which encourages grit and critical thinking, is grounded on [48]. It adheres to the following steps:

- (1)

- Build interest into passion: Students read a text, and each text is selected and edited especially for the age and interests of the students. The readings are about characters who set goals for themselves and show the paths they must take to achieve them. The stories show both protagonists who achieve the goals they set for themselves and others who do not, thus exposing the children to the fact that both outcomes are part of life. It is evident in the readings how the characters transform their diverse interests into their passions.

- (2)

- Identify with a purpose in order to persevere: Students answer three questions. Each question is designed to develop inference, analysis, and argumentation.

The questions address three aspects, the purpose being to motivate them beyond the content itself, and so develop grit [49]:

- -

- Rational aspect: the aim is that the student fully understands the text and feel interested in it.

- -

- Cultural aspect: the text should be close to the student’s reality, so that they can contextualize to similar circumstances in their reality.

- -

- Emotional aspect: the students should feel the story on their own and build an emotional connection with the text.

- (3)

- Give support and feedback: In the last step, the teacher makes a final one-minute reflection, with two questions to the class that encourage metacognition. The first question is always the same: What did you learn today? The second question varies according to the corresponding text. In this final part, the teacher gives general feedback on the work done during the class, highlighting the good aspects and the aspects that need improvement. Both students and educators see this one-minute feedback as a positive and effective learning tool [50].

Students verbally present their responses, leading to a discussion facilitated by the teacher. This approach enhances the exposure to diverse perspectives. Oral expression is crucial in advanced cognitive processes such as inference, adopting different viewpoints, and self-regulation, all of which are essential for successful reading comprehension [51].

Following the questions, a “challenge” is conducted. This involves an engaging activity such as sketching or composing a message. Such playful activities not only render the learning process fun but also boost children’s language growth and holistic educational journey [52].

The contents of our exercise were based on the Chilean fifth-grade curriculum for language and communication. The specific objective, maintained in all classes, was: “To develop a love of reading-by-reading various texts regularly.” Children were exposed to various texts such as letters, poems, stories, and news reports.

Teachers were provided with the necessary classroom materials to implement the above-mentioned model:

- (a)

- Teaching guide, containing the curriculum objective for each class, the explanation of the critical thinking skill to be developed in each question, and the expected answers.

- (b)

- The class PPT, with the students’ reading and activities.

- (c)

- A printable work guide in which students can write the answers and do the activities.

2.4. Implementation

The language instructors for each class underwent training on the materials they would be provided for conducting a weekly class. Subsequently, these instructors were responsible for utilizing the supplied materials to execute the classroom model.

After each working session with the students, the teachers gave feedback on the class to the research team.

2.5. Procedure

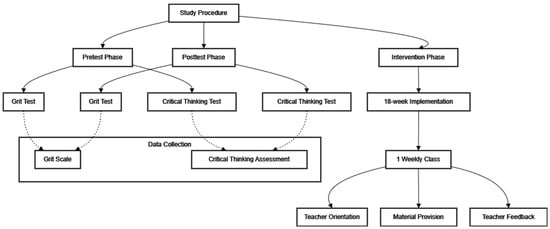

As seen in Figure 1, the study was conducted in three phases: pre-test, intervention, and post-test.

Figure 1.

Procedure of the study.

Pre-test: all students completed a grit test and a critical thinking test two weeks before the intervention began to establish baseline grit and critical thinking skills.

Intervention: the 18-week class model methodology was implemented following the pre-test.

Post-test: the grit and critical thinking tests were administered again one week after the intervention ended to measure improvements.

2.6. Tools

Data were gathered through validated assessments that evaluated both critical thinking and grit in the pre-test and post-test phases.

2.6.1. Grit Test

The tool used to measure grit is the Spanish version and adaptation of the triarchic model of the grit scale [53]. This scale includes 14 items with a Likert scale (ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree) that assesses grit across three dimensions: perseverance of effort, consistency of interests, and adaptability to situations. After corrections, the scores were standardized on a scale from 0 to 100.

2.6.2. Critical Thinking Test

Critical thinking was measured using the instrument defined and validated in [54]. The test was designed for students in grades 3–5 and consists of 29 questions that measure 42 items according to various achievement indicators.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The ethics committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile approved this study, confirming adherence to ethical standards such as those specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. Teacher participants received comprehensive information about the study’s objectives, methods, potential risks, and benefits, and provided written consent after having the opportunity to ask questions. They were also informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Student participants gave their informed assent, and their parents also provided informed consent. All collected data were anonymized to prevent identification in the research findings. Additionally, the data were securely stored and access was limited to the research team, ensuring confidentiality and integrity throughout the research process.

3. Statistical Analysis

This study aimed to examine the relationships between pre-test performance, intervention, gender, and their effects on post-test performance in both grit and critical thinking. The pre-test and post-test scores represent participants’ performance levels, while the intervention refers to the class model being evaluated and is designated as the group variable. It was hypothesized that higher pre-test performance is associated with higher post-test performance and that participants receiving the intervention would show greater improvements in post-test performance compared to the control group. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess these relationships [55].

The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R-squared), which indicates the proportion of variance explained by the independent variables. Additionally, the effect size (f2) measures the magnitude of the relationships, with [56] classification into small (f2 ≥ 0.02), medium (f2 ≥ 0.15), and large (f2 ≥ 0.35).

To explore the relationships between grit and critical thinking, additional cross-prediction analyses were conducted, specifically whether pre-test and post-test critical thinking scores can predict post-test grit scores, and whether pre-test and post-test grit scores can predict post-test critical thinking scores. These analyses aimed to provide insights into the interplay between these constructs, their influence on each other’s development, and the impact of the intervention on these relationships.

By conducting these analyses, a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between grit, critical thinking, and the potential impact of the intervention on these constructs in rural primary school students could be achieved.

4. Results

Building on the statistical analyses outlined in the previous section, this section presents the findings from the multiple linear regression models, focusing on grit post-test scores and critical thinking post-test scores.

For the grit post-test outcomes, the regression model included grit pre-test scores, group (intervention or control), and gender as predictors. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression for grit post-test outcomes.

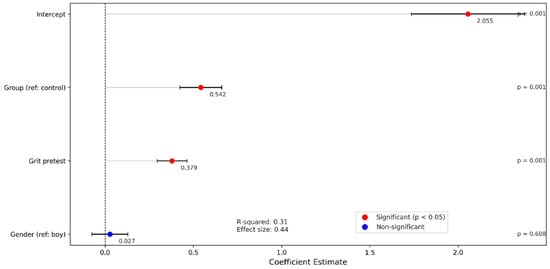

The R-squared value of 0.31 indicates that the model explains 31% of the variance in grit post-test scores. The effect size of 0.44 is considered a large effect according to Cohen’s guidelines, suggesting a practical significance in the relationships between the predictors and the grit post-test outcomes. Figure 2 shows coefficient plot for grit post-test.

Figure 2.

Coefficient plot for grit post-test regression. Note: red points indicate statistically significant coefficients (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors.

- The intercept value of 2.055 represents the predicted grit post-test score when all other predictors are zero.

- The coefficient for grit pre-test scores was positive and significant (β = 0.379, p < 0.05), indicating that for every one-unit increase in grit pre-test scores, the grit post-test scores increased by 0.379 units, holding all other variables constant.

- The coefficient for the group variable (intervention group compared to the control group) was positive and significant (β = 0.542, p < 0.05), indicating that, on average, students in the intervention group scored 0.542 units higher on the grit post-test than those in the control group, after accounting for the effects of grit pre-test scores and gender.

- The coefficient for gender was small and not statistically significant (β = 0.027, p = 0.608), suggesting no significant difference in grit post-test scores between boys and girls when controlling for the other predictors in the model.

For the critical thinking post-test outcome, the multiple regression model included critical thinking pre-test scores, group (intervention or control), and gender as predictors. The model results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression for critical thinking post-test outcomes.

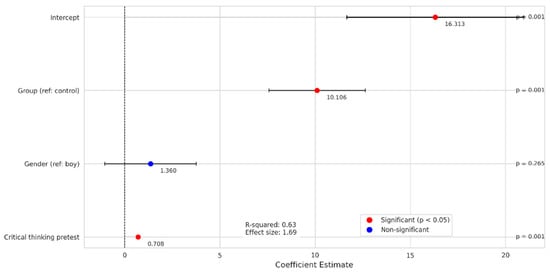

The R-squared value of 0.63 indicates that the model explains 63% of the variance in critical thinking post-test scores, which represents a good model fit. The effect size of 1.69 is considered a large effect according to Cohen’s guidelines, suggesting a practically significant relationship between the predictors and the critical thinking post-test outcomes. Figure 3 shows coefficient plot for critical thinking post-test.

Figure 3.

Coefficient plot for critical thinking post-test regression. Note: red points indicate statistically significant coefficients (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors.

- The intercept value of 16.313 represents the predicted critical thinking post-test score when all other predictors are zero.

- The coefficient for critical thinking pre-test scores was positive and significant (β = 0.708, p < 0.05), indicating that for every one-unit increase in critical thinking pre-test scores, the critical thinking post-test scores increased by 0.708 units, holding all other variables constant.

- The coefficient for the group variable (intervention group compared to the control group) was positive and significant (β = 10.106, p < 0.05), indicating that, on average, students in the intervention group scored 10.106 units higher on the critical thinking post-test than those in the control group, after accounting for the effects of critical thinking pre-test scores and gender.

- The coefficient for gender was not statistically significant (β = 1.360, p = 0.265), suggesting no significant difference in critical thinking post-test scores between boys and girls when controlling for the other predictors in the model.

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine potential cross-predictive relationships between grit and critical thinking scores. Specifically, models included critical thinking pre-test and post-test scores as predictors for grit post-test outcomes, and grit pre-test and post-test scores as predictors for critical thinking post-test outcomes. However, these models did not show improvement, with R-squared values of 0.31 for the grit post-test models and 0.63 for the critical thinking post-test models. Additionally, the coefficients for the added predictors were not statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05). These findings suggest that, in our sample, cross-predictive relationships between grit and critical thinking scores did not significantly impact the respective post-test outcomes. Detailed results from these additional models are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

5. Discussion

The results indicate that the intervention group scored significantly higher on the critical thinking post-test than the control group, demonstrating the intervention’s effectiveness. These findings underscore the importance of targeted interventions for enhancing critical thinking skills. Structured opportunities for critical thinking exercises can lead to substantial improvements, which are crucial for academic success and lifelong learning [57].

As noted in Section 2.3, each question was designed to enhance students’ skills in inference, analysis, and argumentation. In the final stage of the activity, the teacher conducts a one-minute reflection, posing two questions aimed at fostering metacognitive thinking among the students. Our findings are consistent with those of [19], who demonstrated that decision-based learning activities effectively leverage students’ abilities to develop critical thinking skills. Our results indicate that students are indeed capable of developing skills in inference, analysis, argumentation, and metacognition to varying degrees. Further research is needed to explore these findings in greater depth.

The intervention consisted of implementing a language classroom model methodology that promotes critical thinking and grit. Our goal was to build interest into passion. The observed increase in grit and critical thinking showed the students’ cognitive engagement, i.e., interest in their learning, motivation to learn, and perception of the relevance of learning, among others [58]. Cognitive engagement is essential because it influences students’ academic and behavioral engagement. Students who are more cognitively engaged are more likely to attend school regularly, which is especially relevant in rural schools [59].

Moreover, these results imply that initial critical thinking capabilities can act as a base for additional growth. Students with more advanced initial skills might be better equipped to gain from interventions, possibly due to their pre-existing understanding of critical thinking procedures. This highlights the importance of initiating and consistently fostering the development of critical thinking skills throughout a student’s academic path [60].

Regarding grit, initial grit levels and participation in the intervention significantly predicted post-test grit scores. Students with higher initial grit tended to maintain or improve over time. Students who possess higher levels of grit continue to persevere, even when faced with challenging tasks that may not be immediately enjoyable [61]. Furthermore, research indicates that critical thinking is also closely related to a student’s disposition; at this advanced level of thinking, it is crucial for students to make sense of the tasks they are engaging in, as merely following instructions or completing tasks is insufficient [62].

Research on the relationship between grit and critical thinking is limited. Grit significantly moderates the relationship between critical thinking and creativity [63]. However, our results did not reveal significant cross-predictive relationships between grit and critical thinking scores. Further research using different measurement tools or longitudinal designs is needed to explore these relationships in more depth.

While some studies suggest gender differences in grit among age groups [64], the prevailing view is that overall grit does not exhibit significant gender differences [65,66]. This study supports that perspective, showing improved grit performance with intervention, regardless of gender.

Similarly, the relationship between critical thinking and gender is complex. Some studies suggest gender differences due to different thinking patterns and learning habits [67] while others find no significant effect of gender on critical thinking [68]. Our findings align with the latter, showing similar intervention effectiveness between boys and girls.

Our results can also be explained by the rural aspect of our research. Studies suggest that rural environments can cultivate a strong sense of community and self-reliance, which contribute to the development of grit [69]. Although rural schools may lack access to the same level of technology and diverse educational materials available in urban schools, potentially limiting opportunities for critical thinking development [70], the resourcefulness and innovative aspects of this project positively impacted students’ critical thinking abilities.

An important consideration in evaluating the intervention is the feedback from teachers regarding the provided materials. These materials offer a structured framework aligned with the defined objectives [71]. Using varied resources such as visual aids and interactive activities engages students more effectively and enhances learning outcomes [72]. Teachers found the materials well suited and relevant, as they were tailored to students’ lived experiences rather than using a broad, generalized approach. This positive feedback results from the intentional effort to address rational, cultural, and emotional dimensions, as outlined in the methodology section. Teaching materials should consider students’ culture and background, with language being an inseparable part of culture [73,74].

6. Conclusions

The research question guiding this study was: To what extent does a targeted educational intervention affect the development of grit and critical thinking in rural elementary school students? To address this, a classroom model that promotes critical thinking and grit was implemented among 10-year-old students in a Chilean rural area. Teachers were provided with the necessary resources to follow the suggested model for conducting these classes.

The findings highlight the importance of contextually relevant and culturally resonant pedagogical materials in fostering critical thinking and grit. The study advocates for inclusive approaches that benefit all students, regardless of gender, and emphasizes building on students’ initial abilities to maximize educational impact. The intervention significantly enhanced both critical thinking and grit, with the intervention group outperforming the control group consistently across genders. The success of the intervention was largely due to its personalized, student-centered approach, which addressed rational, cultural, and emotional aspects. This approach helped create content that fostered understanding, reflected lived realities, and cultivated emotional investment. Teacher feedback highlighted the relevance and resonance of these tailored materials.

This research has important implications for educational theory and practice, particularly in rural settings where resources and specialized programs are often scarce. It demonstrates that targeted interventions focused on critical thinking and grit can be exceptionally effective. The success of the intervention can be attributed to its reliance on culturally resonant and contextually appropriate materials, which not only engaged students more effectively but also significantly improved critical thinking. Such culturally tailored approaches are particularly advantageous in rural contexts. Furthermore, the study’s personalized, student-centered approach, which incorporated rational, cultural, and emotional learning dimensions, indicates that these strategies can cultivate a more comprehensive educational experience. The results advocate for policy changes to facilitate the development and widespread implementation of similar interventions in other rural areas.

This study has two main limitations. First, its generalizability is restricted. We focused on rural schools in a valley in northern Chile, which may not reflect rural contexts elsewhere. Further research is needed to determine if these findings are applicable to other rural settings. Second, while it is crucial to examine the relationship between grit, critical thinking, and learning performance, we were unable to measure learning outcomes accurately.

Our research design included national language tests as pre- and post-tests. However, only 45% of the children participated in the pre-test, and 43% participated in the post-test, resulting in an insufficient sample size for analysis. Research shows that rural children often participate less in national standardized tests than their urban counterparts. The disparities between rural and urban areas regarding educational access and academic performance can contribute to lower participation rates in standardized tests among rural students compared to urban areas [75].

Rural communities often have unique cultural practices and educational needs that differ significantly from urban settings. This makes it essential for policymakers to consider cultural contexts when designing educational interventions [76]. These cultural differences can influence the relevance and effectiveness of such interventions. To address this, we conducted a comprehensive contextual analysis and engaged with local stakeholders to ensure the cultural appropriateness of our intervention. We adapted the study’s methods and materials to align with local norms and values, recognizing that cultural factors could impact the study’s outcomes.

Given the positive results of the intervention, the materials should be tested with students in other rural areas as a future project. Similar interventions could also be implemented at different educational levels, utilizing the methodological strategies developed in this study. While a causal inference analysis, suggested by Hernán & Robins [77], would be valuable for exploring the relationship between grit and critical thinking in our context, several crucial assumptions for such an analysis are not fulfilled in our current study design. Firstly, the assignment of students to intervention and control groups was not fully randomized. Although we selected a specific age range, we had to work with pre-existing class groups in rural areas. This quasi-experimental setup, though practical, introduces potential selection bias, which undermines the exchangeability assumption essential for causal inference. Secondly, our data collection did not include potential confounding variables such as socioeconomic status or previous academic performance. This omission makes it challenging to satisfy the assumption of no unmeasured confounding, which is pivotal for causal inference methods. Thirdly, although our intervention and control groups were physically separated, reducing the risk of interference, the implementation of our class model varied depending on individual teachers. This variation affects the consistency assumption, which requires the intervention to be uniformly applied across all participants. Additionally, while we used validated instruments to measure grit and critical thinking, the inherent complexity of these constructs poses challenges in completely eliminating measurement errors, another critical assumption for causal inference. Lastly, our study’s duration from March to November, encompassing an academic year, may not be long enough to observe all relevant causal mechanisms, especially for traits like grit that may develop over longer periods. Given these limitations, while a causal inference analysis would significantly enhance our understanding of the interactions between grit, critical thinking, and our educational intervention, our current study design and data collection do not entirely meet the necessary assumptions for such robust analysis. Future research could be structured with these causal inference requirements in mind, potentially facilitating a more comprehensive exploration of causal relationships. For now, our analysis using multiple regression offers valuable insights into the associations between these variables, laying a solid groundwork for future research that might utilize causal inference methods to delve deeper into these relationships.

Finally, given that personalized approaches can improve the acceptability, implementation, and effectiveness of interventions, more research is needed to design interventions that address both cognitive and non-cognitive skill development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci14091009/s1, Supplementary Material 1: Additional Exploratory Analysis, Supplementary Material 2: Teaching guide, Supplementary Material 3: Printable worksheet, Supplementary Material 4: Types of texts during the intervention, Supplementary Material 5: Grit test, Supplementary Material 6: class PPT, Supplementary Material 7: Critical thinking test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.G.-E. and M.N.; Methodology: C.G.-E.; Formal analysis: D.A., M.P. and C.G.-E.; Investigation: C.G.-E. and M.N.; Resources: C.G.-E. and M.P.; Data curation: D.A. and C.G.-E.; Writing original draft preparation: C.G.-E.; Review and editing: M.N. and C.A.-H.; Supervision: M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work also received partial support from grants PID2023-146692OB-C31 (GENIE Learn project) and PID2020-112584RB-C31 (H2O Learn project) funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF, EU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Institutional Review Board, to ensure the ethical treatment of participants in accordance with institutional guidelines. All participants were provided with detailed information regarding the study´s purpose, procedures, risks and benefits, and were given the opportunity to ask questions. Informed consent and assent were obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The IRB approval number is: 210310004, granted on 2 August 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and assent were obtained from all individuals in this study. All participants voluntarily agreed to participate and signed consents and assents forms. The confidentiality and privacy of the participants were ensured throughout the research process, and their personal information has been anonymized in the published work.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Material section. For further inquiries or to request access to data, please contact the corresponding author at cogallardo@uc.cl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Motallebzadeh, K.; Ahmadi, F.; Hosseinnia, M. Relationship between 21st Century Skills, Speaking and Writing Skills: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmadewi, N.N.; Artini, L.P.; Jayanta, I.N.L. Teachers’ Readiness in Promoting 21st Century Skills in Teaching Students at a Bilingual Primary School; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.K.; Körtesi, P.; Guncaga, J.; Szabo, D.; Neag, R. Examples of Problem-Solving Strategies in Mathematics Education Supporting the Sustainability of 21st-Century Skills. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawana, I.R.; Setiani, R. Validity of Teaching Modules with Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Model Assisted by E-Book to Improve Problem-Solving Skills on Renewable Energy Material and Implementation of Independent Learning Curriculum. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2623, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, W.S.; Safitri, G. The Practicality of the Physics Module Based on the PjBL Model with a Portfolio Assessment to Improve Students’ Critical Thinking Skills. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2582, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill-Miller, B.; Camarda, A.; Mercier, M.; Burkhardt, J.-M.; Morisseau, T.; Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Vinchon, F.; El Hayek, S.; Augereau-Landais, M.; Mourey, F.; et al. Creativity, Critical Thinking, Communication, and Collaboration: Assessment, Certification, and Promotion of 21st Century Skills for the Future of Work and Education. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, P.A. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction; Research Findings and Recommendations: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tamam, B.; Corebima, A.D.; Zubaidah, S.; Suarsini, E.E. An Investigation of Rural-Urban Students’ Critical Thinking in Biology Across Gender. Pedagogika 2021, 142, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, E.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M.; de Haan, J. Determinants of 21st-Century Skills and 21st-Century Digital Skills for Workers: A Systematic Literature Review. Sage Open 2020, 10, 215824401990017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Xu, X. A case study of interdisciplinary thematic learning curriculum to cultivate “4C skills”. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 20231080811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, D.; Halpern, D.F. Critical Thinking: Creating Job-Proof Skills for the Future of Work. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarniati, N.W.; Hidayah, N.; Handarini, M.D. The Development of Learning Tools to Improve Students’ Critical Thinking Skills in Vocational High School. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 175, 012095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhan, L.A.; Nasrudin, H. The Correlation Analysis Between Critical Thinking Skills And Learning Outcomes through Implementation of Guided Inquiry Learning Models. J. Pendidik. SAINS 2021, 9, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Jang, G.J. Grit and Problem-solving Ability in Nursing Students: The Mediating Role of Distress Tolerance and Self-directedness. J. Health Inform. Stat. 2022, 47, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permana, T.I.; Hindun, I.; Rofi’ah, N.L.; Azizah, A.S.N. Critical thinking skills: The academic ability, mastering concepts, and analytical skill of undergraduate students. JPBI 2019, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.M.; Corebima, A.D.; Zubaidah, S.; Mahanal, S. The Correlation between Metacognitive Skills and Critical Thinking Skills at the Implementation of Four Different Learning Strategies in Animal Physiology Lectures. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 9, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogus, A.; Göğüş, N.G.; Bahadir, E. Eleştirel Düşünme Becerileri ve Problem Çözmeye Yönelik Yansıtıcı Düşünme Becerileri Arasındaki İlişkiler. Pamukkale Univ. J. Educ. 2020, 49, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridzal, D.A.; Haswan, H. Analysis of the correlation between science literacy and critical thinking of grade eight students in the circulatory system. J. Pijar Mipa 2023, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, K.J.; Kebritchi, M.; Leary, H.M.; Halverson, D.M. Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills through Decision-Based Learning. Innov. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, L.; Bucheerei, J.; Issah, M. Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of Barriers to Promoting Critical Thinking Skills in the Classroom. Sage Open 2021, 11, 215824402110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.H.; Hue, A.N.; Kim, A.T.T.; Hong, H.B. Factors Influencing the Teaching of Critical Thinking to Primary School Students by Primary School Teachers in the Mountainous Region of Northern Vietnam. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 2023, 6, 2282–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiers, J.; Crawford, M. Academic Conversations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, C.; Gracely, E.; Alnouri, G.; Rose, B.; Sataloff, R.T. Efficacy of the Grit Scale Score in Predicting Voice Therapy Adherence and Outcomes. J. Voice 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADuckworth, L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.K.; Brower, H.; Brunsting, N.C. Adjust or crumble while studying abroad. Study Abroad Res. Second Lang. Acquis. Int. Educ. 2024, 9, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldi, D.R.; Nurhayati, E.; Fatimah, Z. The Correlation of Digital Literation and STEM Integration to Improve Indonesian Students’ Skills in 21st Century. Int. J. Asian Educ. 2020, 1, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabacioglu, T. Scratch, computational thinking, and grit: At the beginning, during, and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Öğretim Teknol. Ve Hayat Boyu Öğrenme Derg. Instr. Technol. Lifelong Learn. 2024, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y. The relationship between COVID-19 blues, grit, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction of the University Students in Tourism-Related Departments. Korean Career Entrep. Bus. Assoc. 2024, 8, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón-Salas, P.; Fernández-Martín, F.D.; Arco-Tirado, J.L. Grit as a predictor of self-regulated learning in students at risk of social exclusion. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13365–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, G.; Vaizman, T.; Yaffe, Y. University students’ academic grit and academic achievements predicted by subjective well-being, coping resources, and self-cultivation characteristics. High. Educ. Q. 2024, 78, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, Y. An Analysis of the Impact of L2 Grit on the Intercultural Competence of Chinese EFL Students with Willingness to Communicate Digitally as the Mediator. SHS Web Conf. 2024, 190, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelner, W.C.; Hunter, H.; McClain, C.M.; Elledge, L.C. Dimensions of grit as a buffer on the relationship between environmental stressors and psychological and behavioral health. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 9709–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, N.; Temel, S.; Kansu, C.Ç.V. Examination of the Relationship between Academic Grit and Their Academic Success Fourth Grade Students in Primary School. Int. Online J. Prim. Educ. 2023, 12, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.; Gross, J.J. Self-Control and Grit: Related but Separable Determinants of Success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallahi, O. Critical Thinking Skills, Academic Resilience, Grit and Argumentative Writing Performance of Iranian EFL Learners. J. Mod. Res. Engl. Lang. Stud. 2023, 11, 100–130. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, G. A model of teacher enthusiasm, teacher self-efficacy, grit, and teacher well-being among English as a foreign language teachers. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1169824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Y. The Role of Grit on Students’ Academic Success in Experiential Learning Context. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 774149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.M.; Koorn, P.; de Koning, B.; Skuballa, I.T.; Lin, L.; Henderikx, M.; Marsh, H.W.; Sweller, J.; Paas, F. A growth mindset lowers perceived cognitive load and improves learning: Integrating motivation to cognitive load. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerton, P.; Kelly, R. Creativity and Critical Thinking. In Education in the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Lancrin, S. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking in Science Education. In Education in the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, R. Grit and Academic Success in a Small Rural School: An Ex Post Facto Study; Grand Canyon University: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Britto, D.R.; Rizvana, A.M.S.; George, N.; Subramaniyan, D.; Narayanan, D.; Mani, D.K.R.; Annadurai, E.; Prakas, E.J. Guts, Resilience, Integrity, and Tenacity (GRIT) Among Mid Adolescent School Students in a District of South India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 45, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Shimizu, K.; Sharmin, H.; Widiyatmoko, A. Comparing critical thinking skills between rural and urban students in secondary level education of Bangladesh: A focus on environmental education. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2023; p. 020035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswirna, P.; Roza, M.; Aldania, R. Application of Lkpd Based on Guided Inquiry Model Assisted by Phet Simulation to Learners’ Critical Thinking Skills. J. Learn. Technol. Phys. 2024, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Wang, S.; Lin, W. Nonlinear Effect of Urbanization on the Gap between Urban and Rural Elementary Education in China. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7025433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabillas, A.R.; Kilag, O.K.; Cañete, N.A.; Trazona, M.S.; Calope Mery Lou, L.; Kilag, J.N. Elementary Math Learning Through Piaget’s Cognitive Development Stages. Excell. Int. Multi-Discip. J. Educ. 2023, 1, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, F.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, S.; Kamran, M. Maleeha Exploring the Characteristics of Concrete Operational Stage among Primary School Students. Qlantic J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 5, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rementilla, V. Invisible Teacher: How Might Digital Leisure Games Foster Critical Thinking and Grit? OCAD University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, C. Beyond rational choice: How teacher engagement with technology is mediated by culture and emotions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Banchik, L. Inclusive Assessment of Class Participation: Students’ Takeaways as a One-Minute Paper. PS Polit Sci. Polit. 2022, 55, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Burkhauser, M.A.; Relyea, J.E.; Gilbert, J.B.; Scherer, E.; Fitzgerald, J.; Mosher, D.; McIntyre, J. A longitudinal randomized trial of a sustained content literacy intervention from first to second grade: Transfer effects on students’ reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 115, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirmani, P.; Sumardi, M.S.; Putri, R. Native English teachers (NETs) strategies in teaching English to non-native learners. J. Res. Engl. Lang. Learn. 2023, 4, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Yuen, M.; Chen, G. Development and validation of the Triarchic Model of Grit Scale (TMGS): Evidence from Filipino undergraduate students. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 114, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelerstein, D.; del Río, R.; Nussbaum, M.; Chiuminatto, P.; López, X. Designing and implementing a test for measuring critical thinking in primary school. Think. Ski. Creat. 2016, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, T.; Ayish, N. Correlation between Critical Thinking and Lifelong Learning Skills of Freshman Students. Bartin Univ. J. Educ. Fac. 2017, 6, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pohl, A.J. Strategies and Interventions for Promoting Cognitive Engagement. In Student Engagement; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.C.; Mauldin, C.; Marciano, J.E.; Kintz, T. Culturally responsive-sustaining education and student engagement: A call to integrate two fields for educational change. J. Educ. Chang. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSpector, M.; Ma, S. Inquiry and critical thinking skills for the next generation: From artificial intelligence back to human intelligence. Smart Learn. Environ. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.J.; Kim, Y.W. A clash of constructs? Re-examining grit in light of academic buoyancy and future time perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreucci-Annunziata, P.; Riedemann, A.; Cortés, S.; Mellado, A.; del Río, M.T.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Conceptualizations and instructional strategies on critical thinking in higher education: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1141686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.H.; Lee, H. The Moderating Effect of Grit on the Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Creativity. New Educ. Rev. 2023, 71, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsson, H.; Haga, M.; Elnes, M.; Dybendal, B.H.; Hermundsdottir, F. Motivational Factors Are Varying across Age Groups and Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, W.; Xinyi, W.; Tao, X. Reliability and validity of simple Chinese version of grit scale for elementary school students. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, Y.; Tahmouresi, S.; Tabandeh, F. The Interplay of Mindsets, Aptitude, Grit, and Language Achievement: What Role Does Gender Play? Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumala, F.N.; Yasa, A.D.; Jait, A.B.H.; Wibawa, A.P.; Hidayah, L. Patterns of Computational Thinking Skills for Elementary Prospectives Teacher in Science Learning: Gender Analysis Studies. Int. J. Elem. Educ. 2023, 7, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, E.; Bozan, M.A.; Akçay, A.O.; Akçay, İ.M. An Investigation of Primary School Students’ Critical Thinking Dispositions and Decision-Making Skills. Int. J. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 8, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.R.; Ysasi, N.A.; Harley, D.A.; Bishop, M.L. Resilience and Strengths of Rural Communities. In Disability and Vocational Rehabilitation in Rural Settings: Challenges to Service Delivery; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, E.; Wisdom, K. Rural Schools and the Digital Divide. Theory Pract. Rural Educ. 2021, 11, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R.J. The Art and Science of Teaching: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Instruction; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, S. Education Policy, 1997–2000: The effects on top, bottom and middle England. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2001, 11, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahardika, I.G.N.A.W. Incorporating Local Culture in English Teaching Material for Undergraduate Students. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 42, 00080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pan, R.; Yang, M.; Duan, L. Research on the Paths of Cultural Education in College English Teaching. In Proceedings of the 4th International Seminar on Education Research and Social Science (ISERSS 2021), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–26 December 2021; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. Accessibility and Effectiveness of Online Learning in China’s Vocational Education System: A Comparative Study between Urban and Rural Areas. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 2518–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, P.N.; Sanders, S.R.; Cope, M.R.; Muirbrook, K.A.; Ward, C. New Perspectives on the Community Impact of Rural Education Deserts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHernán, A.; Robins, J.M. Causal Inference: What if; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).