Abstract

Vocabulary is paramount to the successful learning of a foreign language; however, students’ self-efficacy in learning vocabulary has been given scarce attention. This article reports the process of the development and validation of the Questionnaire of English Vocabulary Learning Self-Efficacy (SEVL) for Chinese English as a foreign language (EFL) learners. Data were collected from 439 senior secondary students. Evidence for the psychometric properties of the SEVL is presented. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ensured the internal consistency of the students’ responses to the SEVL model. Then, four aspects of construct validity were identified, including the content, structural, external, and generalizability aspects. The SEVL can serve as an evaluation tool to capture EFL learners’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy and as a research tool to gauge the associations between vocabulary learning self-efficacy and other achievement-related outcomes.

1. Introduction

Vocabulary plays an essential role in language learning; however, vocabulary knowledge is a complex and multidimensional construct that involves multifaceted types of word knowledge, including word form, meaning, and use [1]. Affected by the highly competitive atmosphere and the large amount of vocabulary required by the curriculum and English tests, many English as a foreign language (EFL) learners struggle with memorizing “endless” wordlists. Some of them view language learning as an obstacle, and sometimes self-doubt their capabilities in learning vocabulary [2,3,4,5]. Given that the arduous vocabulary learning process requires learners to spend much time and energy, researchers advocate that it is critical to “step outside the purely lexical issues” and address the motivational factors (e.g., self-efficacy) that affect the outcome of vocabulary learning [6] (p. 358).

Self-efficacy is one of the most influential factors in foreign language learning, and its predictive power on vocabulary learning has been documented [7]. Notwithstanding that a growing number of questionnaires have been made available to investigate EFL learners’ psychological factors in vocabulary learning such as motivation [8,9], vocabulary learning strategies [10], and self-regulating capacity in vocabulary learning [11,12], there is a dearth of questionnaires to specifically diagnose Chinese EFL learners’ self-efficacy in vocabulary learning.

To address these gaps, the current study reports the development process of an instrument (i.e., Questionnaire of English Vocabulary Learning Self-Efficacy or SEVL) to measure Chinese EFL learners’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy and examines the psychometric properties of the SEVL.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy in Language Learning

Self-efficacy is an attribute to the overall construct of student agency [13,14,15]. It is a task-specific, context-specific, and domain-specific psychological concept and is defined as one’s judgment about how well one can complete a specific task based on the self-assessment of one’s capabilities [16]. It is not the belief about whether one is competent in doing something; rather, it is a self-judgment of how strongly a person believes that he/she can accomplish a task in a certain context [17]. As a key concept of social cognitive theory, self-efficacy influences an individual’s thoughts, affect, and behaviors [16,18]. Self-efficacy in language learning pertains to self-efficacy in performing language learning tasks. Research has documented that self-efficacy in language learning affects learners’ use of language learning strategies [19,20,21], perseverance in the face of obstacles [22], emotions during the process of goal-pursuing [8,23], and finally, the accomplishments they realize [24,25].

2.2. Self-Efficacy in EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Learning

Extending self-efficacy to the domain of vocabulary learning, vocabulary learning self-efficacy is the self-judgment of abilities to complete tasks related to vocabulary learning. Vocabulary learning self-efficacy has been a topic of increasing interest in recent years. The research includes (a) studies that investigated the impact of vocabulary learning self-efficacy on language learning outcomes [7,26]; (b) studies that explored the relationship between vocabulary learning self-efficacy and other psychological constructs, such as motivation, anxiety, and use of vocabulary learning strategies [27]; and (c) studies that examined factors associated with EFL learners’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy [28,29]. Nonetheless, the instruments used by the previous studies are bested by certain shortcomings, such as using too general items and confusing items with similar concepts. There is a call for a questionnaire that specifically captures Chinese EFL learners’ self-efficacy in vocabulary learning.

2.3. The Need for a Questionnaire to Measure Chinese EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Learning Self-Efficacy

We highlighted the necessity of a vocabulary learning questionnaire for Chinese EFL learners from the following three perspectives. On the one hand, some existing items are often inappropriate or misrepresented due to the confusion of similar concepts [29]. For example, Tseng and Schmitt [6] developed a motivated vocabulary learning model. Among the six latent variables, vocabulary learning self-efficacy (10 items) is one indicator of the initial appraisal of the vocabulary learning experience subscale. Items such as “I feel I can memorize words faster than other people” and “I feel my vocabulary is larger than others” confused the definition of self-efficacy with self-esteem. Self-efficacy is the self-assessment of one’s abilities to finish a certain task, which does not involve the process of comparing with others. According to Bandura [30], comparing with others pertains to vicarious experiences, which is just one of four sources of self-efficacy rather than self-efficacy per se. Moreover, some items measuring vocabulary self-efficacy were too general and not operationalized into specific tasks, reducing the construct’s explanatory power [31,32]. For example, general items such as “I know the basic vocabulary to some extent” were devised to measure the vocabulary learning self-efficacy of students [26,29]. Such ambiguous items might lead to misunderstandings among students. On the other hand, due to the domain- and context-specific nature of self-efficacy, an instrument specifically targeting EFL learners’ vocabulary learning is needed. Measurements for reading, listening, speaking, and writing self-efficacy cannot be applied to gauge vocabulary learning self-efficacy. For example, an item measuring writing self-efficacy may spotlight the self-judgment of whether one could write a letter in English which does not apply to vocabulary learning self-efficacy. To conclude, given the limitations of previous instruments and characteristics of self-efficacy, there is a need to develop and validate an instrument for EFL learners’ vocabulary learning.

2.4. Framework for Developing SEVL

A sound instrument for self-efficacy relies on “a good conceptual analysis of the relevant domain of functioning” [30] (p. 310). Based on Nation’s [1] taxonomy of word knowledge, we conceptualized the model of vocabulary learning self-efficacy into three indispensable aspects: word form, meaning, and use. There are three components in each aspect. His list of word knowledge is the most comprehensive one up to date, which has been widely referred to by most current vocabulary researchers [33,34]. Spoken knowledge, written knowledge, and word parts are three components of word form knowledge. Mastering spoken knowledge refers to recognizing words when they are heard, pronouncing words with correct intonation, and locating the stressed syllable correctly. Written knowledge is characterized by learners’ spelling knowledge, which includes meaning recognition and production of text. Word parts knowledge involves knowing affixes and stems and knowing how they can be used to build word patterns in the target language.

Word meaning covers three components: form and meaning, concept and referents, and associations. As for the knowledge of form and meaning, learners need to be able to connect the word form and its meaning. Learners have mastered the form and meaning connection when they can use the word [35,36,37], recall or explain the meanings, and recall the word form. Concept refers to the word meaning as an isolated word, while referents are the knowledge about the inferential meanings when learners comprehend a word in context. Mastering the concept and referents of a word includes knowing its homonyms, homographs, and homophones [1], their inherent meaning, and other inferred meanings based on the surrounding context [38]. Associations are semantic relationships between a great number of words. Nouns, adjectives, and adverbs as well as verbs, all have their characteristics and associations. Synonymy is the most common one.

Word use involves understanding grammatical functions, collocations, and constraints on word use. Grammatical functions knowledge is characterized by knowing: (a) the parts of speech of words and (b) grammatical patterns [1]. Collocational knowledge is about patterns of multiword units, in other words, knowing what words typically occur with other words in the target language. There are two kinds of collocations: grammatical collocations and lexical collocations [39]. Mastering the knowledge of constraints on word use refers to knowing when and where certain words can be used in certain contexts. For example, sociocultural background influences word choice based on cultural norms, values, and social contexts [1]. Sociocultural background, frequency of a word, and registers are all constraints on word use [1].

2.5. Construct Validation: Sources of Validity Evidence

A premise of interpreting the results of the investigation and making inferences from the findings is to provide evidence to support the validity of the instrument which is described as whether the instrument measures what it intends to measure [40]. Moving beyond traditional notions of validity [41], Messick [40] suggested that validity should be viewed comprehensively by taking both how the measure is used and how it is interpreted into account. Messick’s validity framework is one of the most extensively used and classical frameworks for understanding the validity evidence of instruments [42,43]. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing by the American Educational Research Association et al. [44] were informed by this notion. Messick’s [40] validity framework involves six distinguishable aspects of construct validity, including content, structural, external, substantive, generalizability, and consequential aspects. The content aspect of construct validity is normally supported by evidence of content representativeness and relevance, which can be realized by seeking help from experts. The structural aspect of construct validity can be ensured by the appraisal of the fidelity of the scoring system to the construct structure. This can be achieved by conducting an exploratory factor analysis or confirmatory factor analysis. The external aspect of construct validity is supported by the relations with other theoretically related constructs. For example, Pearson’s correlational coefficients and regression analysis can be used to reveal the correlations among variables. The substantive aspect of construct validity emphasizes the theoretical basis of respondents’ item response consistency and engagement in assessment tasks. The generalizability aspect of construct validity concerns whether the scores can be generalized to other contexts, population groups, and tasks. The consequential aspect of construct validity is the actual and potential consequences of the test use and score interpretation.

3. The Current Study

This study attempts to address the research gap by developing a new instrument (i.e., SEVL) to measure Chinese EFL learners’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy. As reliability and validity evidence is central to evaluating a newly developed scale, we also endeavor to assess whether the SEVL possesses reliability and validity properties. Accordingly, two research questions were put forward:

- (1)

- What is the evidence of the reliability of the responses to the SEVL?

- (2)

- What is the evidence of content, structural, external, and generalizability aspects of the construct validity of responses to the SEVL?

4. Methodology

4.1. Development of the SEVL

Guided by Nation’s [1] taxonomy of word knowledge, the initial version of the SEVL consisted of 32 items (10 for word form, 12 for word meaning, and 10 for word use).

Next, a committee board was organized, which consisted of three members: an educational psychology researcher, a researcher with expertise in EFL vocabulary learning, and a senior secondary school English teacher. They engaged in the item translation, editing, and sorting phase. The following improvements were made based on the suggestions provided by the committee members. Some ambiguous expressions were replaced or deleted. For instance, “I can tell antonyms of an English word” was rephrased into “I can give antonyms of an English word”. In addition, the item “I can use appropriate attitude words to express my feelings” and “I can use appropriate English words to justify my reasoning” were deleted, since three committee members reached a consensus that these expressions are vague and could hardly be understood by students. Similarly, an individual cannot justify reasoning only by using English words. The committee members were also asked to classify 30 items into three categories to make sure items represent the target dimension rather than other dimensions. One item that failed to be assigned by two of three committee members was deleted from the item pool.

Finally, thirty students in another senior secondary school, who are representative of the target population, were asked to rate the clarity of items. Results showed that most items could be easily understood. One item was removed because 30% of the students reported that the item was not clear. Thus, 28 items were retained as the final version of the SEVL.

4.2. Participants

All ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Board of the University of Macau before conducting the study. Then, we received the consent form from the participating school, guardians, and students. The convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants. Our participants were from a public senior secondary school located in the northwest of China. In total, 439 students participated in the study, of which 230 were male and 209 were female. Their age ranged from 15 to 18 years (M = 16.07, SD = 0.70). On average, at the time of the study, participants had been studying English for nearly a decade (M = 9.94, SD = 2.14). We also collected the highest educational level of their parents: junior secondary school and below (n = 59, 13.4%), senior secondary school (n = 142; 45.8%), undergraduate (n = 196; 44.6%), and graduate or above (n = 42; 9.6%).

4.3. Instruments

SEVL

SEVL starts with collecting participants’ demographic and background information (i.e., gender, age, and time spent on vocabulary learning every week). Following this, participants were asked to reflect on and make judgments about how well they could complete certain tasks regarding word form, meaning, and use, respectively, with 28 items. They were asked to rate their capabilities in vocabulary learning by using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (I cannot do it at all) to 7 (I can do it well). The items in this section were divided into three parts, according to the categorization by Nation [1]: self-efficacy in word form (item 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25), self-efficacy in word meaning (item 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 28), and self-efficacy in word use (item 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27).

- Measures to Validate the SEVL

Motivation in Vocabulary Learning Questionnaire

To gauge students’ motivation in vocabulary learning, we used the Vocabulary Learning Motivation Questionnaire by Li et al. [8]. There were four subscales, including intrinsic motivation (e.g., I like learning English vocabulary), identified regulation (e.g., Learning English vocabulary is beneficial), introjected regulation (e.g., I’d feel ashamed if my classmates think that I am incapable of vocabulary learning), and external regulation (e.g., I do not want to get bad grades). Each subscale consisted of five items. Students rated on a 6-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 6 representing “strongly agree”. The internal consistency of students’ responses was 0.88 for the overall scale and ranged from 0.71 to 0.85 for the subscales. The scale’s construct validity showed adequate fit to the data (χ2/df = 2.65, RMESA = 0.06 [0.05, 0.07], SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90).

TOEFL Junior Standard Test

A practice version of the TOEFL Junior Standard Test was used to measure students’ vocabulary proficiency in the current study, which was developed by the English Teaching Service (ETS) center for 11–15-year-old students. It measures participants’ English proficiency in language form and meaning, listening comprehension, and reading comprehension. Although the suggested age range for the TOEFL Junior Standard Test does not match our sample, we decided to use it after consulting several frontline teachers. They deemed the test appropriate for capturing the vocabulary proficiency in our sample. We purposely selected the language form and meaning section in the present study to capture students’ knowledge of vocabulary form and meaning, which corresponds to their vocabulary learning self-efficacy. Language forms such as verbs, clauses, and collocations, as well as language meanings, were assessed by students’ responses to five reading passages. They were asked to fill in the blanks by choosing the most appropriate expression among four choices within the context of the passage in 25 min. There are 42 items, each correctly answered item was scored 1, and there was no penalty for wrong answers.

5. Data Analytical Procedure

The percentage of missing values was low, ranging from 0% to 1.4%. Missing values were completely missing at random, according to Little’s [45] test (p > 0.05). Full information maximum likelihood estimation was employed to deal with missing data. This method is superior to other methods such as listwise deletion and mean substitution, leading to unbiased parameter estimates [46,47].

The structure aspect of construct validity was evidenced by the internal consistencies of students’ responses to the SEVL and the results of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were employed to check the internal consistency of students’ responses to the SEVL model. CFA was employed to assess the fit of this measurement model to participants’ responses. The parameters of the models were estimated with a maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus 8.3 [48]. CFAs were performed for two competing models, including a unidimensional model and a one-level three-factor model. A large number of the goodness-of-fit indices, including χ2 statistics, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were computed. Acceptable model fit criteria were set as RMSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.08; meanwhile, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90 [49].

Then, Pearson correlational analyses and hierarchical linear regression were carried out to provide evidence for the external aspects of construct validity of responses to the SEVL. The Pearson correlational coefficients indicate the extent to which vocabulary learning self-efficacy, i.e., self-efficacy in word form, meaning, and use, correlates with vocabulary learning motivation and student performance in the TOEFL Junior Standard test. In addition, the unique contributions of dimensions of vocabulary learning self-efficacy to the variance in motivation and academic achievement were explored using two hierarchical linear regression models. The models were run with demographics and self-efficacy as predictors and motivation and academic achievement as outcomes. In the first step, we entered the demographics, including age, gender, and time spent on vocabulary learning every week. Then, three dimensions of vocabulary learning self-efficacy were entered in the second step. R2 values of 0.01, 0.09, and 0.25 were treated as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively [50].

Finally, to verify the generalizability aspect of the construct validity of the SEVL, measurement invariance across gender groups was tested. This is critical because a valid and reliable scale with cross-gender applicability is crucial for understanding the heterogeneity of vocabulary learning self-efficacy [51]. Hence, the configural invariance (invariance of the overall structure), metric invariance (invariance of the overall structure and factor loadings), and scalar invariance (invariance of the overall structure, factor loadings, and intercepts) models were tested by adding constraints in sequence. The model can be viewed as invariant across genders when there is no change larger than 0.01 in CFI [52].

6. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the students’ overall vocabulary learning self-efficacy, three subscales of vocabulary learning self-efficacy, and test scores on the word form and meaning part of the TOEFL Junior Standard test. It suggests that the students’ overall vocabulary learning self-efficacy was at the medium level (M = 4.25, SD = 0.80), between 4 (maybe I can do it) and 5 (I basically can do it). Self-efficacy beliefs were 4.25 (SD = 0.96) in word form, 4.26 (SD = 0.95) in word meaning, and 4.25 (SD = 0.98) in word use. The mean of the students’ performance was 31.27 (SD = 5.06). Given the skewness and kurtosis were within ±2, the distributional properties of each item approximate a normal distribution [53].

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlation Coefficients.

6.1. Reliability of Responses to the SEVL

The internal consistencies of participants’ responses to SEVL were a = 0.97 for all items, a = 0.91 for self-efficacy in word form, a = 0.92 for self-efficacy in word meaning, and a = 0.92 for self-efficacy in word use, respectively. These results suggest that responses to SEVL are reliable.

6.1.1. Content Aspect of Construct Validity

Three steps were undertaken to ensure the content aspect of construct validity. First of all, all expressions of the items (Table 2) in the SEVL were drawn upon the activity-aspect definition of the nine aspects of Nation’s word knowledge taxonomy. For instance, Nation [1] (p. 65) claimed that “knowing the spoken form of a word includes being able to recognize the word when it is heard”. Thus, the item was expressed as “I can recognize the form of an English word when I hear its pronunciation”.

Table 2.

Item-Level Descriptive Statistics.

Secondly, a committee review approach was used in the translating, editing, and sorting phases. All changes were made only when they were agreed upon by three committee members. The educational psychology researcher was mainly in charge of evaluating the appropriateness and clarity of the item descriptions. He also provided suggestions for the structure of the scale. The researcher with expertise in EFL vocabulary learning was invited to evaluate whether the expressions aligned with Nation’s [1] framework and to check the correspondence between the Chinese and English versions. Moreover, suggestions for wording revisions were provided by a senior secondary English teacher who had taught English for over 30 years. She evaluated whether the wording of those items was appropriate and understandable for senior secondary students. These three experts were also asked to classify items into three categories to make sure they represented the target dimension, rather than other dimensions.

Thirdly, after the expert evaluation phase, 30 students from another school, who are representative of the target population, were asked to rate the clarity of items. This can also act as one source of content aspect of construct validity. The clarity of items was satisfactory, with only one item reported as unclear by 30% of the students. It was removed. All other items were reported clear by 98% of the students.

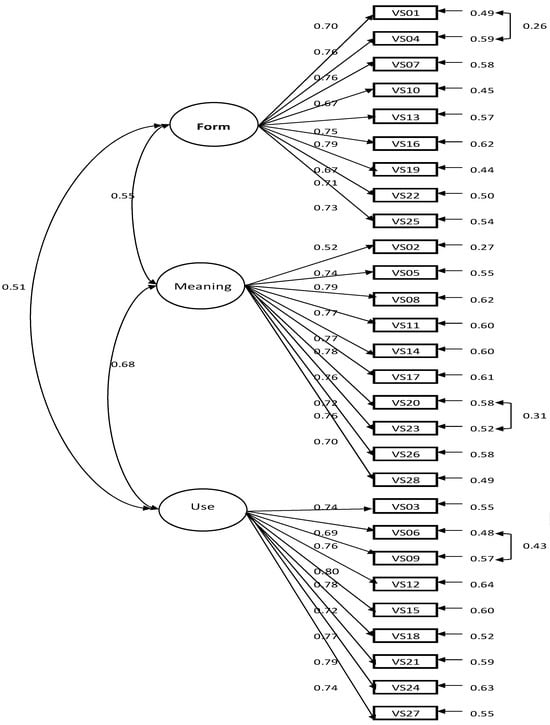

6.1.2. Structural Aspect of Construct Validity

The results of CFA confirmed the factor structure of the SEVL, which contains three dimensions: word form, word meaning, and word use (Figure 1). The goodness-of-fit indices were satisfactory: χ2/df = 2.81, RMESA = 0.06 [0.06, 0.07], SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91. Though the unidimensional model also showed a good model-data fit (χ2/df = 2.81, RMESA = 0.06 [0.06, 0.07], SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91), we chose the three-factor model, given the following two reasons. Theoretically, the three-dimension model was based on the word-knowledge taxonomy [1] and was consistent with the claim that self-efficacy measures should involve more than one dimension [54]. Practically, the three-factor model could provide a more comprehensive understanding of vocabulary learning self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Internal Structure of the SEVL. Note: All factor loadings were significant at p < 0.001.

The factor loadings were all within the acceptable range, between 0.52 and 0.81 [49]. All standard errors were small and ranged from 0.27 to 0.62. However, modification indices (MI) suggested that the chi-square value would decrease greatly by correlating VS06 and VS09. This suggests that VS06 “I can add an English word into a sentence in the correct position” and VS09 “I can tell what other words or types of words can occur with an English word” are closely correlated. These two expressions were derived from the subscale “collocations” in Nation’s [1] word-knowledge taxonomy. If students believe they can tell what other words or types of words can link with a new English word, then they are also likely to believe that they can add an English word into a sentence in the correct position.

For the same reason, we correlated VS20 and VS23. VS20 “I can use alternative expressions to describe an English word when others cannot understand that word” and VS23 “I can replace an English word with its synonym in a sentence” are similar in that they both ask students to make judgments about whether they can tell the synonyms of a word. Understandably, students who can replace a word with its synonym are more likely to use alternative expressions to describe the word.

Similarly, VS01 and VS04 were made to covary. VS01 “I can recognize the form of an English word when I hear its pronunciation” and VS04 “I can correctly pronounce an English word” are related to the mastery of the spoken form of a word. VS01 is the receptive knowledge of spoken form, while VS04 is the productive knowledge of spoken form.

After linking the items with high MI values, we obtained better goodness-of-fit indices, χ2/df = 2.44, RMESA = 0.06 [0.05, 0.06], SRMR = 0.04, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93.

6.1.3. External Aspect of Construct Validity

The external aspect of construct validity was tested with correlations between vocabulary learning self-efficacy, students’ motivation, and performance in the form and meaning part of the TOEFL Junior Standard Test. Pearson correlation coefficients (Table 1) suggested a statistically significant positive relationship between self-efficacy in vocabulary learning and students’ motivation (r = 0.23, p < 0.001 for the relationship between self-efficacy in word form and motivation, to r = 0.28, p < 0.001 for the relationship between self-efficacy in word meaning and motivation). Moreover, a positive relationship was observed regarding the correlation between SEVL and students’ performance in the form and meaning part of the TOEFL standard test (r = 0.43, p < 0.001). Each of the three categories of SEVL was also significantly correlated with test scores, with word meaning having the highest correlational coefficient (r = 0.40, p < 0.001) and word form having the lowest correlational coefficient (r = 0.31, p < 0.001). In addition, the relationship between self-efficacy in word form and self-efficacy in word meaning were both statistically significant, with overall self-efficacy in vocabulary learning r ranging from 0.79 to 0.87.

Results of the hierarchical regression analyses in Table 3 demonstrated that the demographics accounted for 3% and 5% of the variance in motivation and academic achievement, respectively. Self-efficacy in word form, meaning, and use significantly improved the prediction of both motivation and academic achievement. More specifically, 8% of the variance in motivation was explained by the three dimensions of vocabulary learning self-efficacy (adjusted R2 = 0.11), F (3, 432) = 9.72 (p < 0.001). Moreover, an additional 17% of the variance in students’ academic achievement was explained by the three dimensions of vocabulary learning self-efficacy (Adjusted R2 = 0.21), F (3, 432) = 19.96 (p < 0.001). We interpreted these as medium effect sizes [50].

Table 3.

Results of the Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analyses.

6.1.4. Generalizability Aspect of Construct Validity

Results of the configural invariance test demonstrated the generalizability aspect of construct validity, indicating that males and females conceptualized vocabulary learning self-efficacy in the same way. The configural model fitted data well (CFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.062 [0.056, 0.067], SRMR = 0.03). Then, an additional constraint to the invariance of the factor loadings was added. Results showed that the metric model also fitted the data well (CFI = 0.926, TLI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.060 [0.055, 0.066], SRMR = 0.058, ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.002). Compared with the configural model, ΔCFI was less than the benchmark suggested by Cheung and Rensvold [42]. This represents that males and females had no differences in interpreting items in the SEVL. Finally, a more strictly constrained model, where the overall structure, factor loadings, and intercepts were equal, was tested. Results showed that the scalar model was also supported (CFI = 0.926, TLI = 0.924, RMSEA = 0.059 [0.054, 0.065], SRMR = 0.059). No significant changes occurred when compared with the metric model, ΔCFI = 0.000, ΔRMSEA = 0.001. This means that the two gender groups similarly responded to the SEVL. Overall, it is safe to conclude that the SEVL did not function differentially across gender.

7. Discussion

This study not only provided evidence of the detailed development procedures and reliability information for the SEVL in measuring EFL learners’ self-efficacy in vocabulary learning but also presented detailed information about the content aspect, structural aspect, external aspect, and generalizability aspect of the construct validity of the SEVL.

The first purpose of the current study was to investigate the internal consistencies of students’ responses to the SEVL (Research Question 1). High internal consistency for the responses to SEVL in the context of Chinese senior secondary was reported, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.97, and no factor value below 0.90.

The second purpose of the current study was to provide evidence for the content, structural, external, and generalizability aspects of the construct validity of the responses to the SEVL (Research Question 2). The content aspect of construct validity was ensured by drawing items from a reliable source and using a committee approach, and the structural aspect of the construct validity of the SEVL was established by adopting the CFA. Multiple goodness-of-fit indices provided evidence for the structure of the one-level three-factor model. The external aspect of the construct validity of the SEVL was established by the positive relationship between students’ responses to SEVL and vocabulary learning motivation scale and students’ test scores on the TOEFL Standard test in a Chinese EFL context. This result parallels some previous studies that demonstrated that self-efficacy, motivation, and students’ academic performance were closely related [7,8,26,55]. Interestingly, self-efficacy in word meaning appears to be more strongly correlated with motivation towards vocabulary learning and vocabulary proficiency compared to self-efficacy in word form and use. One possible explanation might be that tangible reinforcements and rewards, such as reading comprehension and language proficiency, are largely contingent on the acquisition of word meaning [56,57]. Hence, when students have high levels of self-efficacy in word meaning, they are more likely to be motivated and to achieve better vocabulary proficiency. This finding extends previous research by emphasizing the importance of word meaning relative to word form and use.

In terms of the generalizability aspect of construct validity, results of the gender-invariance test showed that males and females interpret SEVL in the same way. Taking all the evidence together, the current study indicates that the SEVL can adequately assess EFL learners’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy.

As for the pedagogical implications of this study in the vocabulary learning realm, this empirically validated questionnaire can serve as a diagnostic measure to assist teachers in understanding and identifying students’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy in terms of three aspects of word knowledge. In addition, the questionnaire can be used as a guide in cultivating students’ three aspects of vocabulary learning self-efficacy more efficiently and accurately. The items of the SEVL were clearly written and translated abstract concepts (e.g., word knowledge) into concrete, replicable, and measurable terms. In this regard, teachers are recommended to organize diverse vocabulary learning activities and provide more practice opportunities for various types of word knowledge.

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

First, the interpretation of the results of this study may be subject to its limited sample size. It is important to clarify that our questionnaire was only tested in a particular senior secondary school in mainland China. Thus, the extent to which the results and implications hold across diverse backgrounds deserve further investigation. Moreover, investigating the extent to which the SEVL applies to students with different proficiency levels could further enhance the scale’s utility. Future studies are recommended to involve a larger sample size from diverse backgrounds and proficiency levels to test the generalizability of findings in this study. Second, this study provides only limited insight into vocabulary learning self-efficacy. Since only word form and meaning were tested, it is suggested that future researchers include word use tests in their study if possible. Then, a more detailed picture of students’ vocabulary learning self-efficacy can be provided. Third, only the TOEFL junior standard test and motivation in vocabulary learning questionnaires were employed to provide evidence for the external aspect of construct validity, hence, we advocate future researchers integrate more questionnaires of related constructs to flesh out the evidence.

9. Conclusions

This study presented the detailed procedures for developing and validating the SEVL and provided evidence for its psychometric properties. The study contributes to the literature on EFL learning self-efficacy in the following perspectives. On the one hand, a reliable and valid tool specifically for diagnosing Chinese EFL learners’ self-efficacy was provided and a template for rigorously developing and validating a questionnaire was offered. On the other hand, our study highlights the potential of facilitating students’ self-efficacy in vocabulary learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and C.W.; methodology J.L. and C.W.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Macau (SSHRE21-APP009-FED-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Nation, I.S. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.J.; Lin, H. Mobile-Assisted ESL/EFL Vocabulary Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 878–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L. “Gruelling to Read”: Swedish University Students’ Perceptions of and Attitudes towards Academic Reading in English. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2023, 64, 101265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. EST: Evading Scientific Text. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2001, 20, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnby, M. Exploring Student Agency in Narratives of English Literacy Events across School Subjects. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.T.; Schmitt, N. Toward a Model of Motivated Vocabulary Learning: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Lang. Learn. 2008, 58, 357–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bree, E.; Zee, M. The Unique Role of Verbal Memory, Vocabulary, Concentration and Self-Efficacy in Children’s Listening Comprehension in Upper Elementary Grades. First Lang. 2021, 41, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; King, R.B.; Wang, C. Adaptation and Validation of the Vocabulary Learning Motivation Questionnaire for Chinese Learners: A Construct Validation Approach. System 2022, 108, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Examining EFL Vocabulary Learning Motivation in a Demotivating Learning Environment. System 2017, 65, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y. Validation of an Online Questionnaire of Vocabulary Learning Strategies for ESL Learners. Stud. Second. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, A.; Takeuchi, O. Adaptation and Validation of Self-Regulating Capacity in Vocabulary Learning Scale. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 33, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, N. The Predictive Value of the Self-Regulating Capacity in Vocabulary Learning Scale. Appl. Linguist. 2015, 36, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, P.; Poikkeus, A.-M.; Häkkinen, P.; Vasalampi, K.; Rasku-Puttonen, H.; Tolvanen, A. Students’ Agency Profiles in Relation to Student-Perceived Teaching Practices in University Courses. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, P.; Poikkeus, A.-M.; Vasalampi, K.; Valleala, U.M.; Rasku-Puttonen, H. Assessing Agency of University Students: Validation of the AUS Scale. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 2061–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenalt, M.H.; Lassesen, B. Does Student Agency Benefit Student Learning? A Systematic Review of Higher Education Research. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. Self-Efficacy and Language Learning–What It Is and What It Isn’t. Lang. Learn. J. 2022, 50, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Motivation and Social Cognitive Theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, J.; Nie, Y. Self-Efficacy, Task Values and Growth Mindset: What Has the Most Predictive Power for Primary School Students’ Self-Regulated Learning in English Writing and Writing Competence in an Asian Confucian Cultural Context? Camb. J. Educ. 2020, 51, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Wang, C.; Ahn, H.S.; Bong, M. English Language Learners’ Self-Efficacy Profiles and Relationship with Self-Regulated Learning Strategies. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 38, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardegna, V.G.; Lee, J.; Kusey, C. Self-Efficacy, Attitudes, and Choice of Strategies for English Pronunciation Learning. Lang. Learn. 2018, 68, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lake, J.; Padilla, A.M. Grit and Motivation for Learning English among Japanese University Students. System 2021, 96, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, F.; Adnan, A.; Marlina, L. The Correlation between EFL Students’ Listening Anxieties with Listening Self-Efficacy in Listening Class. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2020, 9, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, T. Relationship Between Self-Efficacy and Language Proficiency: A Meta-Analysis. System 2020, 95, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. Boosting Learners’ Confidence in Learning English: Can Self-Efficacy-Based Intervention Make a Difference? TESOL Q. 2023. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, A. Enhancing Self-Efficacy in Vocabulary Learning: A Self-Regulated Learning Approach. Vocab. Learn. Instr. 2013, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardasheva, Y.; Carbonneau, K.J.; Roo, A.K.; Wang, Z. Relationships Among Prior Learning, Anxiety, Self-Efficacy, and Science Vocabulary Learning of Middle School Students with Varied English Language Proficiency. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.C.; Hwang, M.Y.; Tai, K.H.; Chen, Y.L. Using Calibration to Enhance Students’ Self-Confidence in English Vocabulary Learning Relevant to Their Judgment of Over-Confidence and Predicted by Smartphone Self-Efficacy and English Learning Anxiety. Comput. Educ. 2014, 72, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H.; Mohammaddokht, F.; Fathi, J. Exploring the Effect of Assisted Repeated Reading on Incidental Vocabulary Learning and Vocabulary Learning Self-Efficacy in an EFL Context. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 851812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bong, M.; Cho, C.; Ahn, H.S.; Kim, H.J. Comparison of Self-Beliefs for Predicting Student Motivation and Achievement. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 105, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peura, P.; Aro, T.; Viholainen, H.; Räikkönen, E.; Usher, E.L.; Sorvo, R.; Aro, M. Reading Self-Efficacy and Reading Fluency Development Among Primary School Children: Does Specificity of Self-Efficacy Matter? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2019, 73, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, B.; Schmitt, N. Word Knowledge: Exploring the Relationships and Order of Acquisition of Vocabulary Knowledge Components. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 41, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.F.; Chang, S.C.; Hwang, G.J.; Zou, D. Balancing Cognitive Complexity and Gaming Level: Effects of a Cognitive Complexity-Based Competition Game on EFL Students’ English Vocabulary Learning Performance, Anxiety and Behaviors. Comput. Educ. 2020, 148, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.; Stewart, J.; Batty, A.O. Predicting L2 Reading Proficiency with Modalities of Vocabulary Knowledge: A Bootstrapping Approach. Lang. Test. 2020, 37, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckel, T.; McLean, S.; Nation, P. Limitations of Size and Levels Tests of Written Receptive Vocabulary Knowledge. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2021, 43, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. The Relationship between Vocabulary Knowledge and L2 Reading/Listening Comprehension: A Meta-Analysis. Lang. Teach. Res. 2022, 26, 696–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, C. On Monosemy: A Study in Linguistic Semantics; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, M.; Benson, E.; Ilson, R. The BBI Dictionary of English Word Combinations; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, S. Validity of Psychological Assessment: Validation of Inferences from Persons’ Responses and Performances as Scientific Inquiry into Score Meaning. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Test Validation. In Educational Measurement, 2nd ed.; Thorndike, R.L., Ed.; American Council on Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1971; pp. 443–507. [Google Scholar]

- Fosnacht, K.; Copridge, K.; Sarraf, S.A. How Valid is Grit in the Postsecondary Context? A Construct and Concurrent Validity Analysis. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. Content-Related Validity Evidence in Test Development. Handb. Test Dev. 2006, 1, 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association; American Psychological Association; National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus Version 8.3; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Cleary, T.J. Adolescents’ Development of Personal Agency: The Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs and Self-Regulatory Skill. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; King, R.B. Which Comes First? Modeling Longitudinal Associations Among Self-Efficacy, Motivation, and Academic Achievement. System 2024, 121, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, B. Understanding L2-Derived Words in Context: Is Complete Receptive Morphological Knowledge Necessary? Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2024, 46, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoder, P.; Laufer, B. EFL Learners’ Receptive Knowledge of Derived Words: The Case of Swedish Adolescents. TESOL Q. 2022, 56, 1242–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).