Abstract

This study aims to illustrate the complex relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension for Black girl readers. There is an urgent need for research that explicitly centers on the reading motivations of Black girls through a humanizing, asset-oriented lens. Through a Situative Black Girlhood Reading Motivations lens, which integrates a situative perspective on motivation and the tenets of Black Girlhood Studies, this multi-year study focuses on a group of Black girl readers participating in a summer reading program. Qualitative data, including video observations, student work artifacts, and small-group artifact-elicited interviews, were analyzed through a generic inductive approach to answer the research question, “How are relationships between Black girls’ reading motivations and their reading comprehension evident in their reading engagement and enactments?” The findings demonstrate that the participants’ most salient reading motivations in this instructional context (meaning-oriented, collaborative, and liberatory reading motivations) (1) were a precursor to their comprehension, (2) worked in tandem with their comprehension, and (3) stemmed from their comprehension. These findings contribute to models of reading by illustrating the need for additional complexity when describing the relationship between reading motivation and comprehension.

1. Introduction

This study aims to illustrate the complex relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension for Black girl readers. There is an urgent need for research that explicitly centers on the reading motivations of Black girls through a humanizing, asset-oriented lens. Over the past 30 years, there has been limited research investigating the reading motivations of Black girls [1]. When studies have focused on understanding Black readers’ motivations [2,3], it has often been through a deficit lens. For example, these studies focus on Black readers’ motivations as a means of addressing the “achievement gap”, citing students’ persistent underperformance on achievement outcomes and invoking images of Black students falling behind and dropping out of school. This hyper-focus on achievement data has, at times, undermined potentially affirming findings. For example, Baker and Wigfield [4] found that Black readers self-reported higher reading motivation across multiple domains, including self-efficacy and importance. However, they then went on to discuss how Black readers’ motivations did not correlate to their achievement, suggesting that low-achievement expectations in schools might lead students to overestimate their actual competency. Not only are these studies premised on addressing the “achievement gap”, but they also tend to employ a comparative design, where Black readers are compared to their white counterparts. Although a common practice in quantitative psychological research, critical scholars have noted that “studies that simply compare racial groups on key learning outcomes can limit a sophisticated consideration of race, perpetuate perceived deficiencies among disenfranchised people groups, and propagate dangerous cultural superiority assumptions for predominant groups” [5] (p. 1).

This multi-year study focuses on a group of Black girl readers participating in a summer reading program designed to attend to their literacies [6] and support their engagement with complex texts by and about Black girls/women. While reading motivation and reading comprehension have generally been conceptualized as universal constructs applicable across populations of readers, this study demonstrates the affordances of attending to participants’ intersecting racialized and gendered identities as a means of moving towards more equity- and justice-oriented literacy research and teaching.

Defining Reading Comprehension and Reading Motivation

Examining the complex relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension is an endeavor fraught with theoretical, conceptual, and equity-oriented challenges. To begin with, there are varying perspectives on what comprehension is, which inherently informs how models are developed to represent it. A comprehension-as-outcome perspective [7] posits that comprehension is something someone has or does not have because of having read a text. The text contains certain information, and the reader arrives at the “right” understanding of that information. A comprehension-as-procedure perspective [7] views comprehension as a stable, relatively uniform procedure that enables students to arrive at the “right” understanding of texts. A comprehension-as-sense-making perspective [7] argues that comprehension is a purposeful decision-making process about what a text might mean, a process that is characterized by constant textual hypothesizing bound up in social purposes.

Models of reading have often presented an oversimplified view and struggled to encompass the diversity of factors known to influence comprehension [8]. For decades, research has demonstrated the array of characteristics and abilities that enable skilled readers to make meaning with text. However, reading comprehension depends not only on the reader but also on factors beyond the reader, including the text(s) they are reading, the type of reading activity they are engaged in, the context in which they are reading, and their purposes for reading. While some models, such as Freebody and Luke’s four resources model [9] and the RAND Reading Study Group model [10], include these factors, they fall short of explicating how these elements interact or unpacking them to further identify the many factors that contribute to each [8]. There is also a need to explicitly address the ways in which every facet of reading is culturally constructed and thus intricately connected to readers’ intersecting identities (race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, language, etc.). In their review of research and scholarship involving Black girls’ literacies, Muhammad and Haddix [6] found limited research on reading or the reading development of Black girls that maintained an asset-based perspective. Instead, they argue that when Black youth are the focus of reading research, their scores on a single assessment are usually highlighted, suggesting a comprehension-as-outcome perspective [7] rather than their cultural resources, which might be better captured using a comprehension-as-sense-making perspective [7]. This can further marginalize them by creating narratives that focus on struggle or deficit.

Similarly, despite the importance of reading motivation in understanding the development and practices of reading, problems persist in how motivation-related constructs have been defined and investigated [11]. Although many scholars now agree that motivation is multidimensional, comprising several factors, there is a lack of conceptual clarity among these factors. There is a tendency for reading motivation researchers to fail to provide explicit definitions of constructs or use conceptually distinct motivation-related terms interchangeably. Reading motivation research has also been conceptualized and studied in culturally homogenous ways [1], prioritizing perspectives, participants, and measures that assume white middle-class motivations as “normal”. Exploring racially, linguistically, and socioeconomically diverse students’ reading motivations through this framing limits our understanding of how readers are motivated and ignores additional nuance in the relationship between reading motivation and reading comprehension. In previous studies [12,13], Black girl readers have demonstrated distinct reading motivations, including meaning-oriented, collaborative, and liberatory reading motivations, that have not previously been represented in traditional reading motivation constructs.

To mitigate these challenges, this study adopts a comprehension-as-sense-making perspective [7], drawing on a more holistic, comprehensive model of reading to do so. The Deploying Reading in Varied Environments (DRIVE) model [14] of reading, which illustrates reading processes through an extended metaphor comparing reading to driving a car, incorporates a broader array of processes and influences than other popular models. The characteristics of this model that distinguish it from other popular models also make it productive for investigating the relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension for Black girl readers. First, the DRIVE model frames the reader as the purposeful “driver” of the reading and actively engaged with texts. Just as drivers choose to get in the car and go somewhere, readers choose to read. Both readers and drivers manage a complex collection of processes. Through this lens, Black girl readers can be seen as having agency in when and how they engage with reading processes. Second, the DRIVE model includes many contributors to reading, including those typically included in other models, such as decoding and strategy use, and those typically left out, such as the mood of the reader and features of the text. The breadth reflected in the model affords opportunities to acknowledge the multiplicity of Black girls’ literacies [6]. Third, reading purpose and text are critical in the DRIVE model. Readers’ purposes (drivers’ destinations) require different collections of behaviors and the texts readers engage with, including text types (road types), text structure (traffic patterns), organizational signals (road signs), and other text features (other road features), can make reaching that destination more or less challenging. Finally, the DRIVE model integrates cognitive and sociocultural views of reading and allows for interactions among contributing factors. This added complexity, exemplified by including purpose and text, integrating theoretical perspectives, and allowing for interaction among elements, can disrupt deficit narratives of Black girl readers and support more asset-oriented perspectives on their reading development and performance.

The DRIVE model also offers a clear, yet more culturally inclusive, definition of reading motivation. Much like a driver cannot begin without igniting the engine, reading does not begin without the motivation to engage in the process. However, while ignition is typically considered as being turned “on” or “off”, motivation comes in degrees. Readers may be mildly motivated to engage in a reading task, highly motivated, or anywhere in between. Motivation is more than just ignition. Motivation also provides the gas needed to sustain the driving experience. Some driving tasks require little gas, whereas others require multiple tanks; some reading tasks require little motivation to be successful, and others require more sustained motivation. Thus, reading motivation is conceptualized as what gets you started and what keeps you going as a reader. The breadth of this conceptualization is productive for exploring the relationship between reading motivation and reading comprehension for Black girl readers because it allows for Black girl readers to be motivated in a multitude of ways and for a multitude of reasons, disrupting more narrow views of reading motivation that have privileged white cultural norms and perspectives.

2. Background

2.1. Black Girl Readers

Although there is limited research on Black girls’ reading motivations [12,13,15], studies of their literacy practices have more broadly attended to constructs, such as self-efficacy [16] and value [17], that are consistently included as dimensions of reading motivation [11]. Self-efficacy answers the question, “Can I be a good reader?” and reflects students’ beliefs about their abilities. Research with Black girl readers frequently emphasizes the importance of what they are reading by suggesting that texts as mirrors [18], which reflect readers’ identities and lived experiences, are supportive of students’ self-efficacy and motivation. Studies suggest that reading texts with positive representations enriches comprehension, including making connections and thinking critically [19], and fosters positive reading attitudes [20]. Similarly, Ford and colleagues [21] argue that gifted Black girls who engaged in bibliotherapy with texts they culturally identified with developed positive self-efficacy and engagement. Heterogenous textual representations, reflecting the notion that Black girls are not a monolith, are important and offer opportunities for readers to explore their own identities and others’ [15]. Engaging with varied representations of diverse Black girl experiences allows readers to connect with portrayals that reflect their experiences, negotiate those that are different, and challenge those that are negative [6].

Self-efficacy is shaped not only by what Black girls read but also by how they are asked to read. Researchers commonly recommend situating Black girl readers’ experiences within culturally relevant pedagogy, including instruction that values literacy practices built on relationships, communal connectedness, and community support [6,19]. As a component of culturally relevant pedagogy, student choice plays an important role [20]. Instructional contexts such as book clubs promote skill development (e.g., critical discussion, higher-order thinking) while also allowing Black girls to voice issues that are personally meaningful, suggesting that feelings of ownership positively influence readers’ self-efficacy [19].

Even if students feel self-efficacious and believe that they can achieve a reading task, they may disengage if they do not find value in it. Thus, self-efficacy alone cannot guarantee engagement. Value answers the question, “Do I want to be a good reader, and why?” Research on Black girl readers addresses value by describing tensions between “text-centered, teacher-based” instruction [22] and the “subversive literacies” [23] of Black girls. “Text-centered, teacher-based” instruction describes the tendency for instruction to prioritize readers’ ability to acquire information from text over their personal experience of a text. Evaluating students on discreet skills (e.g., knowledge of literary conventions, providing text-based interpretations) reinforces this singular focus. Black girls, on the other hand, often value initiating meaning for themselves [12,19]. When faced with these competing priorities, they may critique pedagogical strategies, including questioning text selection and teacher-approved interpretations [22], or remain silent to navigate classroom literacy structures [23]. Researchers argue that increasing the alignment between the type of reading that is valued in classrooms and by Black girls will better support reading motivation.

2.2. Black Literate Communities

The social context frames the nature of reading, its purpose, and its place in the classroom community. Thus, the development of students’ reading motivations cannot be fully understood without considering the contexts in which that development occurs. Today’s Black girl readers are part of a historical legacy of fugitive literacy practices [24], representing an intergenerational dedication to literacy that resists colonization of the mind and body. Throughout history, in the face of systemic and political obstacles across sociopolitical and geographical contexts, Black communities have persisted in sustaining literacy traditions [25]. When denied access to literacy opportunities, they created their own [26]. Within these contexts, Black readers have maintained intellectual, social, and cultural motivations for reading.

To support literacy development, communities of Black readers created ways for individuals with varying skills to read together in both formal (e.g., community schools, literary societies, reading rooms, etc.) and informal (e.g., homes, churches) contexts [26]. Black readers supported each other’s skill development through the use of holistic practices and collaborative pedagogies that emphasized making meaning with text, including reading aloud, using everyday texts (e.g., newspapers, fliers), modeling literacy skills, engaging in critical feedback, and practicing reading, writing, and oracy as interconnected [25,26]. Skill development was not the end goal; rather, it was intended to support intellectual development. Historically, Black readers viewed literacy as offering a sense of freedom and control over their inner self [26] by improving their mental condition [27]. Together, communities of Black readers supported individual and collective agency, encouraging readers to pursue topics of interest. Reading in Black literacy communities continues to be collaborative, involving a co-construction of knowledge [6,12] through collective engagement with texts [28] in pursuit of deepening and expanding knowledge.

Knowing how to read and knowing about topics have been core pursuits of Black literate communities. However, Black readers have also been motivated to know and advocate for themselves. Literacy was a form of cultural capital and a tool for liberation because “the ability to read was not an end in itself; it was part of a larger process of training individuals to claim the authority of language and effectively use it to participate in reasoned and civil debate” [26] (p. 102). Literacy allows Black readers to give voice to their experiences and see themselves more fully [26,27]. Facing racism and oppression, Black readers have always been motivated by the transformative potential of literacy, reading (and writing) to instill pride, racial solidarity, and racial consciousness. Thus, identity and criticality are essential facets of Black literacy, as engagement affords opportunities to come closer to selfhood and transform society [6].

These historical practices are reflected in Nolen’s [29] concept of “literate communities”, which describes modern classrooms in which literacy serves a central social function, providing opportunities for students to develop literate identities and to experience literacy as a means of self-expression and communication. In these classrooms, literacy activities form a social core that helps establish and maintain relationships among individuals. The context of the “literate community” has implications for students’ motivations because when reading (and writing) are allowed to serve a more communal function, motivations can develop and spread through shared experiences of exploration, communication, and enjoyment [29].

3. Conceptual Framework

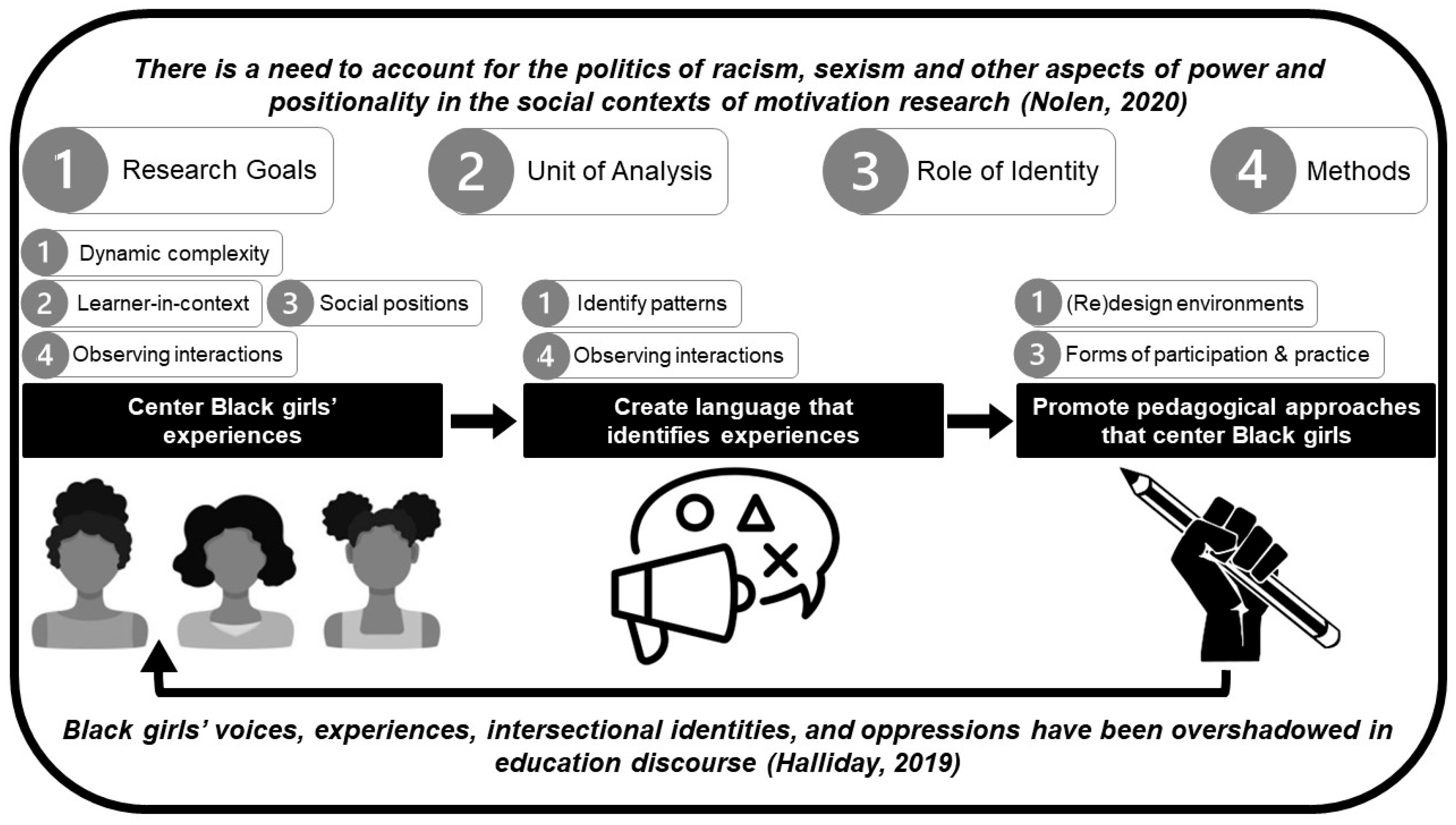

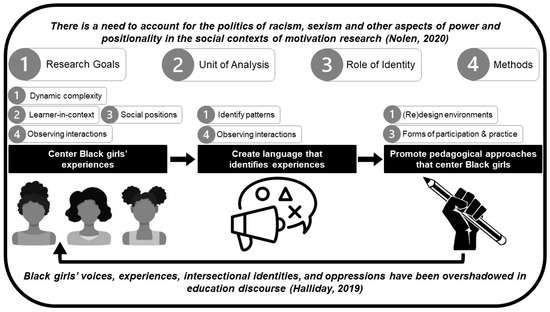

For the purposes of this study, I employed a Situative Black Girlhood Reading Motivations (SBGRM) lens to understand participants’ motivations for reading and how these motivations afforded opportunities to demonstrate text comprehension skills. SBGRM (see Figure 1) integrates a situative perspective on motivation [30] and the tenets of Black Girlhood Studies [31,32]. A situative approach addresses the urgent need to account for the politics of racism, sexism, and other aspects of power and positionality in motivation research [30], while Black Girlhood Studies addresses the ways Black girls’ voices, experiences, intersectional identities, and oppressions have been overshadowed in education discourse [31]. Employing SBGRM as a conceptual lens challenges the pervasive whiteness of motivation research [33] and the predominance of sociocognitive, quantitative approaches [11]. While instruments, such as survey tools and observational protocols, exist to measure reading motivation, they are not designed to consider the centrality of race, culture, and equity [1,6] in how students understand and enact reading motivation.

Figure 1.

Situative shifts for studying motivation and the tenets of Black Girlhood Studies in support of Situative Black Girlhood Reading Motivations [30,31].

3.1. Situative Motivation

Motivation researchers intend to answer the question, “Why do people do what they do?” Unlike sociocognitive approaches, which understand motivation as a property of the individual, situative approaches frame motivation as arising from individuals’ interactions within social systems [34]. Such a shift in framing requires commensurate shifts in (1) the goals of the research, (2) the unit of analysis, (3) the role of identity, and (4) the research methods.

Taking a situative approach to studying motivation alters the goals of the research. While sociocognitive approaches aim to create universally generalizable models, the goal of a situative approach is to account for the dynamic complexity of individuals’ motivations within and across various social contexts and over time [35]. Situative approaches focus on noticing patterns that might generalize beyond specific cases and contexts but, more importantly, remain grounded in the particularities of the given context. These patterns can then inform the design or redesign of learning environments.

In a situative approach, the unit of analysis shifts from the individual learner to the learner-in-context. While sociocognitive approaches may consider how a context influences an individual, the context and the person are interpreted as functioning separately. When the learner-in-context becomes the unit of analysis, the individual is part of the social context (not merely influenced by it) and the individual’s activities, identities, and motivations are co-constructed by the community [35]. Shifting the unit of analysis is consequential because it creates the opportunity to examine power and positionality and moves past deficit explanations, such as an individual or group of individuals “lacking” motivation.

When considering the role of identity, sociocognitive approaches view it as a demographic category (e.g., race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.) whose impact can be statistically controlled or manipulated. For situative researchers, this approach is too simplistic to fully capture the complexity and intersectionality of individuals’ identities. Instead, a situative perspective considers engagement (or disengagement) in a context as inseparable from individuals’ identities [35]. While identities shape motivations, they are also continuously being negotiated within and across contexts. Identities (or aspects of one’s identity) can alter one’s social positions and access to forms of participation and practice, depending on the context. Thus, individuals’ identities cannot be isolated from their motivations.

Since taking a situative approach involves a commitment to understanding individual activity within social settings, a shift in methodology is called for. Sociocognitive researchers tend to privilege quantitative analyses of self-report instruments [11] that measure various pre-determined constructs (e.g., intrinsic motivation, self-concept, value, etc.). Situative researchers, on the other hand, tend to privilege methods that capture in-the-moment activities between people, objects, and spaces [34], such as ethnographic observation and semi-structured interviews. Qualitative analyses allow for the careful examination of people’s activities and provide an opportunity to focus on the affordances of particular contexts for supporting specific kinds of engagement.

These shifts in (1) the goals of the research, (2) the unit of analysis, (3) the role of identity, and (4) the research methods support the tenets of Black Girlhood Studies in the SBGRM framework.

3.2. Black Girlhood

Black Girlhood Studies specifically addresses the multifaceted and complex realities of Black girlhood [31,36] through a celebration of Black girls as “co-creators of knowledge, co-witnesses of their genius, and co-conspirators of freedom” [32] (p. 119). As a theoretical lens, Black Girlhood Studies builds on Black feminism, which considers how Black girls’ experiences are inherently tied to their race, gender, and other intersecting identities, by also centering the nuances of girlhood to resist perpetuating Black girls’ adultification [37,38]. In educational studies, the goal of using Black Girlhood Studies as a theoretical lens is to (1) center Black girls’ experiences in educational settings, (2) create language that identifies those experiences, and (3) promote pedagogical approaches that center Black girls.

These goals are central to the SBGRM framework (see Figure 1). A situative approach to centering Black girls’ experiences as readers allows for exploring the dynamic complexity of their reading motivations within and across contexts, including how they grapple with their Black girlhood as readers in contexts, such as school, that are rooted in anti-Blackness, racism, sexism, and classism. When the unit of analysis is the Black girl reader-in-context, understanding the ways Black girls experience and enact reading motivation is privileged over determining how well they align with constructs that have been developed with and for predominantly white readers [1]. Attending to the complexity of intersecting identities, including those beyond race and gender, and their varying social positions resists homogenized and over-essentialized descriptions of Black girl readers. Observing how Black girl readers interact with their contexts creates opportunities to bring forth their voices as experts of their own experiences.

Creating language that identifies Black girls’ experiences as motivated readers is facilitated through a situative approach. Observational methods and qualitative analyses support the identification of patterns in Black girls’ motivations, activities, and participation within a given context, across contexts and over time. Using an asset-based orientation and privileging how Black girls themselves describe, write, or express what it means to be a motivated reader can combat pervasive deficit narratives and discourse on Black youth [39].

The shifts required by situative perspectives foster the goal of promoting pedagogical approaches that center Black girls. Centering Black girls’ multifaceted and nuanced identities to understand how they, individually and collectively, take up different forms of participation and practice emphasizes their agency, creativity, and resistance within oppressive structures that often frame them as “a problem to solve” [36]. Learning environments can be (re)designed so that they are better able to recognize, value, and capitalize on the ways Black girls are motivated to read.

4. Materials and Methods

This study aims to answer the research question, “How are relationships between Black girls’ reading motivations and their reading comprehension evident in their reading engagement and enactments?” Framing the study through the lens of Situated Black Girlhood Reading Motivations (SBGRM) informed all aspects of the study design. While most motivation research has taken a deductive approach, beginning with a particular theory (with its specific definitions of motivation, achievement, interest, etc.), testing a hypothesis, and then connecting it back to established theory, a generic inductive approach [40,41] is better suited to the context, participants, and goals of this study. Table 1 summarizes the features of the generic inductive approach [40].

Table 1.

Features of a generic inductive approach.

Rather than relying on theories and constructs that have been developed with other groups of readers and are known to center white, middle-class norms [1], I employed qualitative research methods to understand participants’ perspectives and experiences within this specific social context.

4.1. Context

I conducted this study in partnership with Chance to Climb, Inc. (CTC; all names are pseudonyms), a nonprofit organization serving fourth- through sixth-grade students in an “urban emergent” [42] city in the southeast U.S. During the summer, CTC partners with local independent schools to offer a month-long “camp” that includes academic enrichment classes, including reading, writing, math, and science, and extracurricular activities, including art, dance, yoga, swimming, sports, and more. Students choose to participate in CTC. During the school year, the organization shares information about the summer program with schools across the district. While there is an application process to attend due to a limited number of spaces available, there is no associated cost, and transportation is provided. CTC enrolls students from roughly 35 different schools across the metro area, predominantly those serving low-income communities, including public, charter, magnet, and independent schools. In 2018, 2019, and 2021 (programming was canceled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic), I was the reading teacher at one programming site.

Each summer, CTC students were divided into grade-level cohorts (small groups ranging in size from six to ten students each) to rotate through academic classes in the morning, with each class meeting for 40–45 min daily for four weeks. The reading class was generally structured as a book club, where we collaboratively read and discussed a variety of texts, including poetry (e.g., Say Her Name, by Zetta Elliott), short stories (e.g., Black Enough: Stories of Being Young and Black in America, edited by Ibi Zoboi), and novels (e.g., Last Summer with Maison, by Jacqueline Woodson). All the texts were written by Black authors and featured Black girl protagonists. To center Black girls’ literacy practices, I designed the curriculum to attend to the components of the Black Girls’ Literacies Framework [6], which argues that Black girls’ literacies are multiple, tied to identities, historical, collaborative, intellectual, and political/critical (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Curriculum design of CTC summer reading classes aligned to the Black Girls’ Literacies Framework [6].

The students spent the first week each summer studying the history of African American women’s literary societies. Inspired by what they learned, each cohort co-created a mission statement outlining their literacy vision. The remaining three weeks revolved around shared engagement with text. The students chose how to read (independently, with peers, with a teacher reading aloud, or with a high school student serving as a classroom assistant) and respond (sharing questions, reactions, big ideas, or images). The students were responsible for leading discussions about the texts, leveraging their experiences and interpretations. Our discussions followed the trajectory of the students’ contributions, valuing divergent thinking and allowing for multiple perspectives and interpretations. As much as possible, I worked to avoid being seen as the authority on accurate interpretations simply because I was the teacher in the room. Instead, I allowed the girls to negotiate their understandings with each other and work through potential misunderstandings or misconceptions.

In addition to the texts we read together, the students also had the opportunity to borrow books from our own mini-library. All the books in the library featured Black protagonists, predominantly girls, and were written by Black authors. The books in the library spanned a range of text complexities, from beginning chapter books to young adult novels. The students could borrow books to read during their leisure time throughout the CTC day (e.g., during lunch, on the bus to field trips or activities, etc.) and at home. Access to this mini-library allowed the students to engage in a different reading experience than the shared reading in class and also afforded them opportunities to make connections across texts.

It is important to note that given the overall structure of the CTC program, there were minimal outside constraints on the curriculum design. For example, there were no grades or assessments as part of the program. There were no requirements to teach to specific standards or address specific learning goals. As a result, there was an extraordinary amount of flexibility to meet the needs and interests of the students. In-the-moment changes to the curriculum were made as needed throughout the four weeks of instruction and from year to year. The instructional context, designed around Black girls’ literacies, affords opportunities to understand Black girls’ reading motivations and reading comprehension beyond the constraints of instructional settings typically designed to uphold white normative literacy practices [22].

4.2. Participants

Across the three years of data collection (2018, 2019, 2021), a total of 42 girls who attended CTC participated in the study. CTC students often attend for multiple years. Approximately 1/3 of the 2018 study participants had attended CTC the previous year. The following year, nine girls who had participated as 5th graders in 2018 returned as 6th graders in 2019. This subset of participants engaged with the curriculum designed for this study for two consecutive years. As a result of the 2020 program cancellation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all the participants in 2021 were first-time CTC students. Nearly all participants (38) identified as Black/African American. Two students who identified as multiracial during the consenting process also self-identified as Black during academic and social conversations. To maintain my commitment of centering Black girls, only the data from students who identified as Black/African American and multiracial/Black were analyzed (40).

4.3. Data Collection

Since studies on Black girls’ reading motivations are limited, this work was exploratory in nature. I engaged principles of design-based research (DBR), moving through cycles of research design, enactment, analysis, and revision, in pursuit of practical improvement and theoretical refinement [43]. At each iteration, I used conjecture mapping to specify theoretically salient features of the research design, map out how they were predicted to work together to produce desired outcomes, and articulate the methods that would be used to link the embodiment of the design (e.g., tools, structures, practices) to the outcomes [43]. In other words, each summer’s data informed both the research and the curriculum design of the following summers.

During the first summer, in 2018, I collected reading motivation self-report survey data using the Motivations for Reading Questionnaire (MRQ) [44], video recordings of class sessions, ethnographic field notes (including brief in-the-moment notes during each class and extended notes at the end of each day), instructional materials (including lesson plans, presentations, and text selections), and student work artifacts (including individual reading notebooks and group work posters/charts). Findings from this iteration of the study, which have been detailed elsewhere, revealed a misalignment between how reading motivation was captured on the MRQ and how the CTC girls enacted reading motivation in our classroom context [12].

During the second summer, in 2019, I continued to collect observational data (video recordings, field notes, instructional and student work artifacts), but rather than using the MRQ I invited students to participate in small-group artifact-elicited interviews. Artifact-elicited interviews use visual, verbal, or written stimuli to encourage participants to talk about their ideas [45]. In these interviews, I used the motivation survey items as a stimulus to prompt students’ discussions about reading motivation. These tasks are useful for exploring topics that may be difficult to discuss, including those that rely on tacit knowledge or abstract concepts, such as reading motivation. Elicitation techniques can also make the interview setting more comfortable and reduce power imbalances between the interviewer and the respondents, especially with adolescents who may feel that they are being tested on their ability to supply the right answers [45]. This iteration of the study, which is described in detail elsewhere [13], offered evidence that CTC participants were motivated to read to grow in their ability to make meaning with text (meaning-oriented reading motivation), be in community with others (collaborative reading motivation), and understand themselves, others, and society (liberatory reading motivation).

During the third year, 2021, I again continued to collect observational data (video recordings, field notes, instructional and student work artifacts). Consistent with the Situative Black Girlhood Reading Motivations conceptual framework, later iterations of the research design privileged qualitative data collection methods.

4.4. Data Analysis

Immediately following data collection each year, all video data (e.g., class sessions, small group interviews) were transcribed using Rev transcription services, followed by manual verification. I then uploaded all data files (e.g., video data with transcriptions, student work artifacts, etc.) to NVivo for coding. Data analysis was an iterative, ongoing process that occurred throughout the duration of the study. I analyzed each year’s data prior to the next year’s data collection process. The data analysis between cycles focused on describing the participants’ reading motivations [12,13,15]. To answer the research question, “How are relationships between Black girls’ reading motivations and their reading comprehension evident in their reading engagement and enactments?” I engaged in retrospective analysis of the entire corpus of data across all three years, employing a generic inductive approach. The generic inductive approach [41] is a systematic procedure for analyzing qualitative data, where the analysis is guided by specific research objectives. Taking an inductive approach allows research findings to emerge from the frequent, dominant, or significant themes inherent in the data.

The inductive analysis process began with a close reading of the text (transcriptions, artifacts, etc.). The purpose of the close reading was to (re)familiarize myself with the content of the data and gain a general understanding of the themes and events captured in the data. Although the data had previously been analyzed for evidence of participants’ reading motivations, each year’s data had been analyzed in isolation. Reviewing the entire corpus offered the opportunity to notice larger trends across research cycles. By taking a comprehension-as-sense-making perspective [7], the observational data (e.g., video recordings with transcripts, field notes, student work artifacts) were able to capture evidence of students’ textual hypothesizing and sense-making. The questions that guided this phase of data analysis included:

- How do these Black girls enact reading motivations in these classroom contexts?

- What do they do or say that shows their reading motivations?

- How do these Black girls work to make meaning with and comprehend complex text(s)?

- What do they do or say that shows their comprehension of text(s)?

Following a close reading of the data, I began the coding process. Because the data had previously been coded for reading motivation, I began by refining existing codes. Through multiple iterations, I grouped similar codes together and re-labeled them to reduce overlap and redundancy among the categories. For example, “helping” and “tutoring” were initial codes representing how students engaged with “talking with others”. When a succinct category label did not appear in the data, I drew on my interactions with the girls in other contexts (e.g., before and after class, lunch, afternoon extracurricular activities) to create labels that I thought reflected terms they might have used. Finally, the categories were collapsed, and relationships among categories were described to create a model that incorporates the most important categories from the data.

I had not previously coded the data for reading comprehension, so I first identified specific segments of the data related to this facet of the research objective. For transcribed data, the unit of analysis was each participant’s turn taking. In class discussions, multiple students spoke back to back and for various lengths of time. Each turn ranged from a few words to a sentence to a full paragraph of transcribed talk. For artifact data, the unit of analysis was a visual entry, such as a single page in a reader’s notebook or a contribution to a group poster/chart. These could be written text or drawn images. After identifying segments of interest, I labeled them to create and define categories. Labels were used to describe how the segment illustrated comprehension-as-sensemaking. I iteratively grouped similar codes together to create succinct categories, such as “strategy use (e.g., questioning, visualizing, summarizing, etc.)”, “textual decision making”, differences of opinion”, and “evaluation”.

Once the data had been coded for both reading motivation and reading comprehension, I then identified instances of co-occurrences of these codes to determine evidence of relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension. To do this, I identified data segments that had been coded as both one or more reading motivation codes and one or more reading comprehension codes. Upon identifying these co-occurring data segments, I created interpretive descriptions for each. These interpretive descriptions included summaries of the original coding logics (for reading motivation and reading comprehension) and an interpretation of a possible relationship between the two. The findings presented next are grounded in these interpretive descriptions.

Given logistical constraints (e.g., program timing, participant age, participants returning to schools across the city, and the impact of COVID-19), I was not able to conduct member checks for the completed data analyses as intended. However, analysis across the different data sources within a study year and across study years allows for triangulation of emergent findings, thus lending credibility to the study.

5. Findings

Building on the findings from earlier study iterations [13], analysis of the qualitative data from all three years of the study offered evidence of various ways these Black girl readers’ meaning-oriented, collaborative, and liberatory reading motivations related to their reading comprehension. In response to the research question, “How are relationships between Black girls’ reading motivations and their reading comprehension evident in their reading engagement and enactments?” three trends emerged. First, their reading motivations were a precursor to their comprehension of texts, supporting them as they worked through moments when comprehension broke down. Second, their reading motivations worked in tandem with their comprehension of texts, supporting them as they deepened or expanded their understanding. Third, their reading motivations followed their comprehension of texts, allowing them to demonstrate new or different motivations after they had experienced successful comprehension of a complex text. In the sections that follow, I provide illustrative examples from the data to support each of these emergent themes.

5.1. Reading Motivations as a Precursor to Comprehension

The participants’ reading motivations were often expressed as a precursor to their comprehension. They drew on various elements of their motivations to read when faced with moments when their comprehension broke down. They relied on these motivations to navigate these challenges, which supported them in coming to an accurate understanding of the text.

In the interviews, the students often described their meaning-oriented reading motivations as being motivated to read so that they can develop strong reading skills. Jasmine, who said “They [motivated readers] are trying to push themselves to get better”, and Tionna, who said, “If you’re willing to work hard, that means you are trying to get better”, illustrate the concept of being motivated to read so that you can improve as a reader. Eva adds complexity to this idea by saying, “You need to push yourself…you mess up a little and you are right a little, but that means you keep on pushing”. She acknowledges that even motivated readers will face setbacks along the way, but they will continue to engage as readers so that they can overcome those challenges.

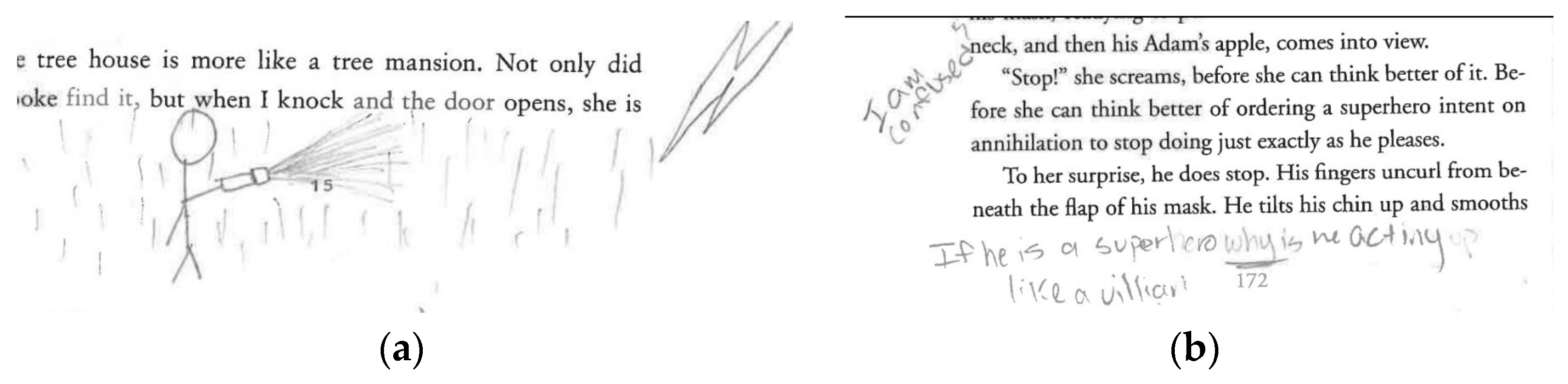

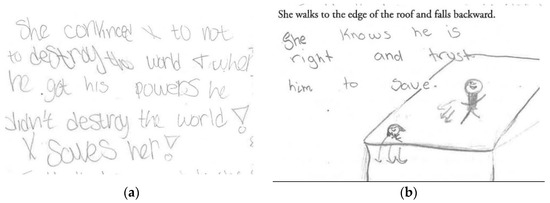

Evidence from student work artifacts and class discussions shows how their meaning-oriented reading motivations allowed them to persist through moments when comprehension broke down (Figure 2). In her text annotations, Amika sketched what was depicted in the text scene. Later, during the group discussion, Amika read the scene aloud and explained to the group how a few key words in the passage confused her. She shared that once she started drawing her picture, she was better able to understand the setting and consider its impact on the character’s actions. Another student, Devin, used her text annotations to ask questions. She first identified that she was confused (“I am confused”), and then articulated the point of her confusion. She wrote, “If he is a superhero why is he acting like a villain?” This question would later become the catalyst for a lengthy group discussion.

Figure 2.

Evidence from students’ text annotations of meaning-oriented motivation as a precursor to comprehension. (a) Amika’s annotation illustrating a scene in the text; (b) Devin’s annotation pointing to an area of confusion and asking a question to clarify.

For these students, leveraging their meaning-oriented reading motivations meant continuing to push through when they were struggling to comprehend parts of a text. Without this specific reason for reading, they may have continued without fully understanding the text or given up on the reading entirely.

The students’ collaborative reading motivations, in which they privileged reading as a collective, community-building endeavor, also preceded comprehension. This was evident when they worked together to fix individual or group errors. During class, the girls often chose to read with a partner, during which time they would take turns reading the text, pausing to talk. These “turn and talk” conversations were often opportunities for students to leverage their collaborative reading motivations to help each other make sense of the text. For example, while reading with her partner one day, Devin was stuck on the word “roster”. At first, she read it as “roaster”, but looked to her partner with a puzzled expression on her face. Her partner re-read the sentence prior, which confirmed for Devin that “roaster” did not make sense in the context of the story. Devin summarized what was read, and her partner offered a possible definition of the unknown word. Devin then said, “oh, roster! Like taking attendance”. Moments later, Devin and her partner used their clarified understanding of this moment in the text to discuss how the characters might be feeling and why it would be relevant to the overall plot. Because this pair of readers was motivated to read and engage with the text together, they were able to support one another’s comprehension.

Selecting rich, complex texts to anchor the curriculum meant that there were many times when students’ comprehension faltered, at either the individual or group level. Our whole-group conversations afforded students opportunities to draw on their collaborative reading motivations to work together to clarify misconceptions or revise inaccurate interpretations. For example, in the short story “Half a Moon” by Renee Watson, there was confusion about whether the two main characters, Raven and Brooke, knew that they were half-sisters. The girls grappled collaboratively with this:

- Alyssa:

- If Brooke doesn’t know that Raven is also her dad’s daughter, then I don’t know if Raven is gonna tell Brooke [that she is her sister].

- Dr. Jones:

- Let’s talk about that, because this came up on Friday, too, this debate about whether Brooke knows. Does Brooke know that Raven is her father’s daughter?

- A’mor:

- I think, yes, because Raven and Brooke are avoiding each other, and you wouldn’t avoid somebody for no reason. And they, I think it says, Brooke is avoiding her and not making eye contact.

- Alyssa:

- But Brooke knows her only as a person and not as her father’s daughter. Because why would you wave at someone who is your half-sister and, like, “Hey, half-sister!”. Wouldn’t it be weird?

- A’mor:

- Well, I think…to not have a connection with your half-sister? Like, you would want to know someone who you’re related to…because at some point you’re gonna want to know and understand.

The conversation continued for some time, with other girls adding in evidence from the text and personal connections that supported the inferences they were drawing. Through this conversation, the girls concluded that while both characters did have knowledge of their relationship, the depth of their understanding and their feelings about it were different.

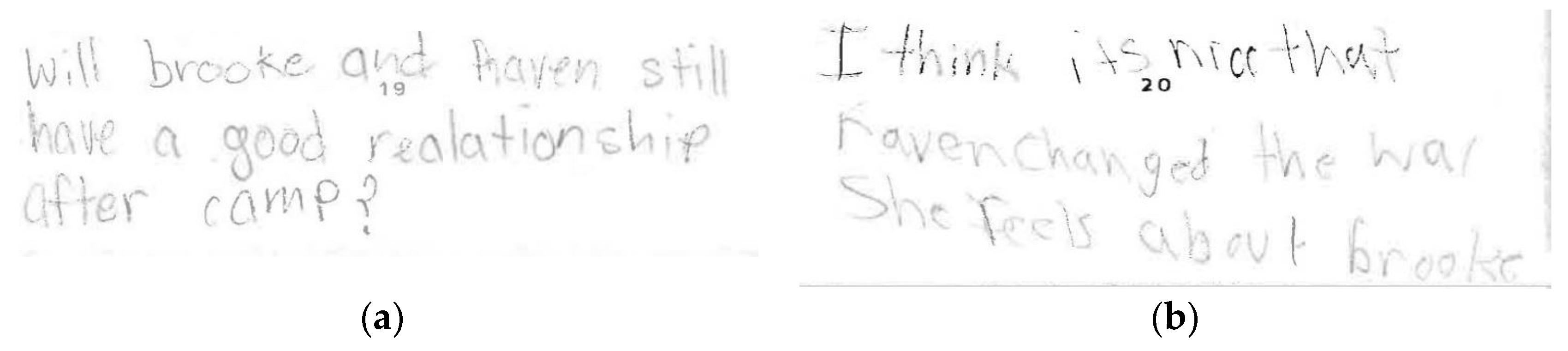

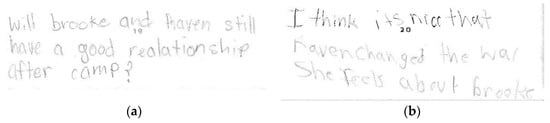

Drawing on their collaborative reading motivations supported them in coming to an accurate and thoughtfully nuanced interpretation of the text, which then allowed the students to better comprehend later events in the text. Evidence from the students’ text annotations shows the comprehension strategies they used later in the same short story that built on the understanding gained during the collaborative discussion (Figure 3). Both Magdalena and Monroe made text annotations at the conclusion of the story that connected back to the relationship between the main characters. Magdalena asked a question (“Will Brooke and Raven still have a good relationship after camp?”) that extended beyond the text, while Monroe drew an inference (“I think it’s nice that Raven changed the way she feels about Brooke”) that demonstrated her comprehension of the characters’ development over the story.

Figure 3.

Evidence from students’ text annotations of collaborative motivation supporting comprehension. (a) Magdalena’s annotation asking a question for discussion; (b) Monroe’s annotation drawing an inference.

Students’ collaborative reading motivations, and their perspective that reading is a collective endeavor to make sense of text, supported them in working together when their individual or group understanding was lacking.

5.2. Reading Motivations Alongside Comprehension

The participants often drew on their reading motivations alongside their developing comprehension. In other words, the students had already demonstrated that they comprehended the text, but they leveraged their collaborative and liberatory reading motivations to deepen and add complexity to how they were making sense of the text. Unlike motivation as a precursor to comprehension, this relationship occurred in a more integrated and simultaneous manner.

In group discussions, the girls often enacted their collaborative reading motivations by adding nuance and complexity to each other’s ideas. As opposed to approaching comprehension as one right way to understand the text, the girls often took a “yes, and…” approach, making space for multiple possible interpretations. In this exchange, Sirona and Mariella are discussing the book Patina, by Jason Reynolds.

- Sirona:

- She’ll do anything for her mom. Like, she’ll make herself feel better. Like, when she says she sends smiley faces to her. And her mom will send them back even though she doesn’t like texting at all or sending the text. It doesn’t help her mom feel better, but it helps her feel better.

- Mariella:

- It makes her and her mom feel better because she said she liked receiving text messages. And also, it makes Patty happy when she sends her mom text messages so her mom knows that she’s thinking about her and caring about her when she does the dialysis.

In this conversation about Patina’s relationship with her mother, Mariella enacts her collaborative reading motivations by adding on to Sirona’s contribution and nuancing their collective understanding of the text. As these interactions continued to occur, the girls were more likely to follow up on their own ideas or the ideas of others with statements such as “but then again…” or “it could also be…”.

The students’ discussion of the short story “Super Human” by Nicola Yoon offers another example of their collaborative reading motivations working in tandem with their text comprehension. This conversation illustrates the motivation to pursue multiple interpretations of a text:

- Brooklyn:

- He saved her from a truck and after that they were only focusing on his race. He stopped saving people after a while, and then the broadcast came.

- Magdalena:

- Well, I think what Brooklyn is trying to say is he’s tired of letting people down. So, he didn’t come in a fire, and then he didn’t stop the people from the train crash, and then he didn’t stop the college student. Like, he started letting people down.

- Brooklyn:

- Yeah, but he did it on purpose.

- Magdalena:

- I think he did it on purpose because he said that he no longer believes in humanity. He did that stuff before, but then he just feels like…maybe he just wanted to tell them that he doesn’t want to save them anymore.

- Alyssa:

- Yeah but, right now I’m wondering why he doesn’t believe in humanity anymore? Is it because they were just talking about his race or they’re just believing things that are maybe not true?

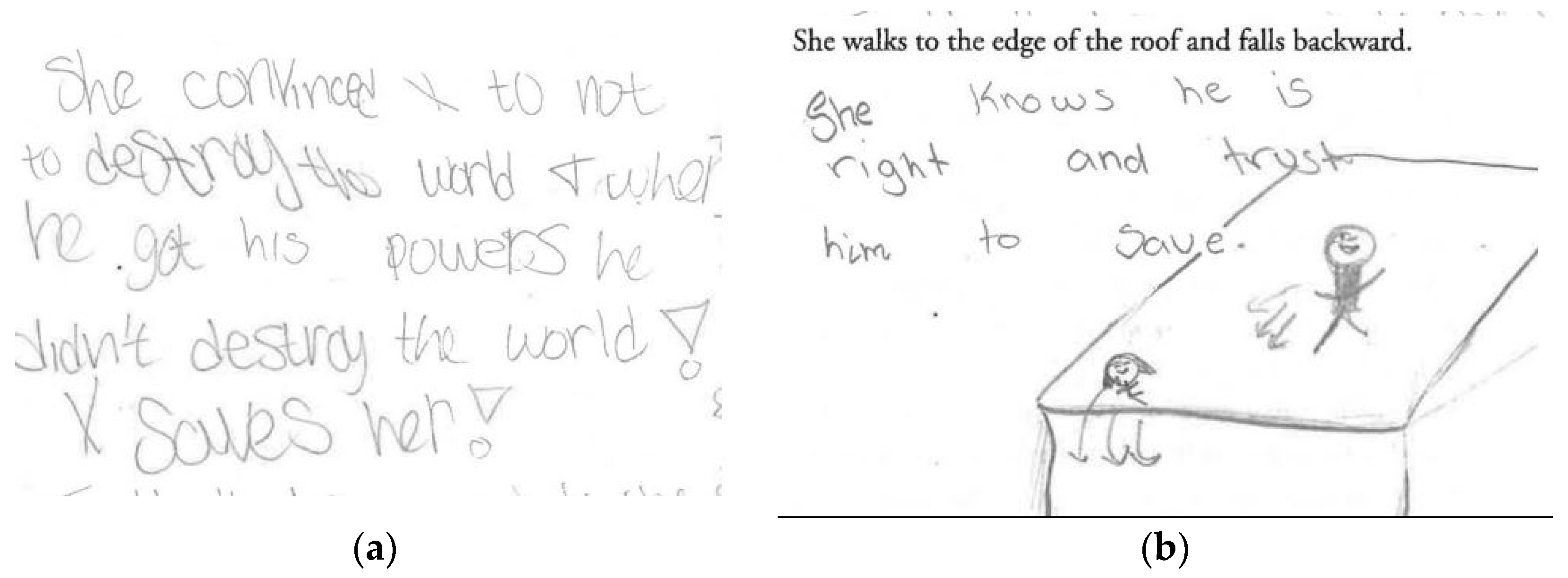

Students continued to hold on to these various interpretations of why the character, X, had decided to not be a superhero anymore as they continued reading and used them to make sense of the cliffhanger ending (Figure 4). Alyssa included a text annotation confirming a prediction she made earlier, based on this initial conversation (“She convinced X to not to destroy the world & when he got his powers he didn’t destroy the world! X saves her!”). Amika used drawing to visualize the final scene and included a written inference explaining why the narrator intentionally fell off the roof (“She knows he is right and trust him to save”).

Figure 4.

Evidence from the students’ text annotations of collaborative motivation deepening comprehension. (a) Alyssa’s annotation confirming a previous prediction; (b) Amika’s visualization of the final scene and inference.

For these students, being motivated to read by collaboration afforded them opportunities to nuance and expand their initial understandings of the texts. Without this reason for reading, they may have been motivated to seek only one “correct” interpretation of the text.

The students’ liberatory reading motivations, in which they were motivated to read to be able to understand themselves, others, and issues in society, also worked alongside their comprehension. I use the word liberatory to represent how the act of self-discovery and criticality can be freeing for Black girl readers whose literacy practices are often not honored or valued in classrooms [6]. When sharing their perspectives about reading motivation in the interviews, the girls discussed making connections between reading, their own lives, and the lives of others. In class, they demonstrated liberatory reading motivation by centering social justice in both the purpose and content of their conversations. As they developed their comprehension of the texts, they often enacted their liberatory reading motivation by using collective pronouns, such as “we”, “our”, “us”, and “you”, in discussions to show how they were connecting to the text, working to understand the perspectives and experiences of others, and grappling with larger social issues. For example, Lily did this when commenting on how Patina often put on a brave face:

By using “you” and “you’re”, Lily shows she is speaking to and about a collective experience of being independent to a fault, which the girls further discussed as being a prevalent stereotype of Black girls and women.“I don’t say that independence is a bad thing, but it’s not necessarily a good thing in my opinion because you’re taking so much work for yourself, but you’re just stressing yourself out even more…it’s just going to come back and overflow and explode…because, again, you’re independent and you’re a leader, so that means that you think you have nowhere to go to since you’re so independent, and you’re pushing everyone away from you.”

In a discussion about the text Last Summer with Maizon, by Jaqueline Woodson, Brooklyn and Ada also utilized their liberatory reading motivations, as evidenced by their use of collective pronouns, as they deepened their understanding of the text. In a conversation about the return of Maizon’s absent father, Brooklyn shared:

Ada continued:“He was always crying and stuff…he can’t forget about her mom and her even though he tried. But…you can’t forget about them just that quick. And especially when that’s your daughter. You can’t just forget about her.”

Reading to understand others, including characters and people who make hard choices that the girls might not fully understand, is a reflection of their liberatory reading motivations. Being motivated to read in this way coincides with their comprehension and supports them in moving past surface-level understanding to explore nuance and complexity.“Why would you forget about your own daughter? But I understand why he’s back now…especially when you are mad, it’s gonna be hard for you. Seeing your daughter, when you ain’t see your daughter in 13 years…that’s gonna be hard for other dads, especially because her dad is who took off on his daughter…that’s your daughter no matter what.”

5.3. Reading Motivation Stemming from Comprehension

The experience of successfully comprehending a complex text afforded opportunities for many of the girls to also enact new or different reading motivations. They were able to try out alternative reasons for reading that they might not have explored previously once they had a baseline understanding of the text to build on. They articulated this notion in their interviews. Eva summarized many of their shared perspectives when she said she was motivated to read “books you can find connections in…to your own life and when you share those with your friends, they might get that book and be interested in it and can, like, share similarities in the book…and y’all can come together and just talk about what y’all thought about it”. Thus, comprehending texts, especially by making connections while reading, can impact readers’ collaborative reading motivations and prompt them to share books and talk about them with others.

The girls often enacted these new reading motivations by engaging in reading practices that they had not before. The exchange below, from a discussion of Jason Reynolds’s Patina, illustrates this:

- Mariella

- I wrote [in my readers’ notebook], “I didn’t need Ghost or Lu or Sunny or anybody to take up for me”. I said Patty is a powerful woman, who doesn’t need the boys taking up for her.

- Sirona:

- Yeah, she is independent. She can handle things herself like she does for her family and her sister. She can also defend herself.

- Keanna:

- To go back to what Mariella said about her being powerful…I agree, because…she’s like, “I don’t need make up, I don’t need any of that to be powerful”. I think that she’s like, “I don’t need any boys to take up for me, I can take up for myself,” and that’s something that a powerful woman would say.

Prior to this conversation, Sirona and Keanna had not been using their readers’ notebooks while reading. However, following this exchange and having heard Mariella say that she wrote her ideas down while reading, they began to do so. Similarly, Sirona and Keanna modeled more inferential thinking in the conversation, and Mariella, who tended to share more literal ideas and summaries of the text, began to do this more often in later conversations. Experiencing this sense-making moment supported all of the girls in utilizing meaning-oriented and collaborative reading motivations in ways they had not yet done.

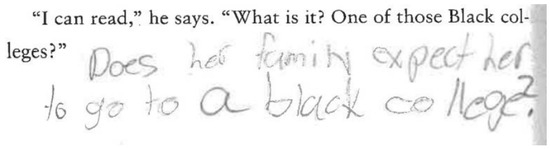

Reading motivations as the result of comprehension were also evident in how students engaged with Brandy Colbert’s short story “Oreo”. In the beginning of the story, Naomi asked a question in her text annotations (Figure 5) and also during the group discussion. She was confused about the moment in the text when the main character admits to her family that she has been admitted to Spelman, a historically Black college.

Figure 5.

Naomi’s text annotation asking a question about the text prior to discussing as a group.

Naomi had anticipated that since the main character was Black, her parents might expect her to go to an HBCU (“Does her family expect her to go to a Black college?”). When she brought this up in the group conversation, the girls returned to the text itself to find evidence explaining the parents’ reaction.

- Monroe:

- I think she has mixed emotions about [getting into Spelman] because…right now she’s not even 100% sure if she wants to go. Even though she got in…because it’s a Black college and her cousins are calling her an Oreo, like saying that she is white…She doesn’t think that she’ll fit in at a Black college.

- Maya:

- Yeah, she has mixed emotions about college because it’s a HBCU and her dad, on page 113 it says ‘Sometimes my father said Black like it’s a bad taste in his mouth’.

- Jasmine:

- Ok, so basically what that means is, sometimes other people think of Black people in a different and bad ways…and I think that she lives in a white neighborhood because she had a lot of white friends and she never really had no Black friends. I think they might live in an all white neighborhood because they’re Black and they want people to see them as good people. So, when her dad says Black like gives a bad taste…that’s what they went in an all white neighborhood.

- Monroe:

- I also think that they live in an all white neighborhood…I think the dad chose where they live because he says ‘Black’ like it’s a bad taste in his mouth, so I think he wanted his kids to be around more white people. And maybe he thinks that Black people are bad? So he’s not like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m Black!’. He’s kind of hiding it.

This conversation continued over multiple days as we continued to read further along in the story.

Although Naomi clarified her initial interpretation, she still grappled with why the characters might be feeling and acting as they did. A few days later, as Naomi was explaining her thinking about one of the characters in the group discussion, we realized that she had read farther ahead in the story than that day’s goal. When she started to give evidence from later in the text, the class immediately responded with a resounding gasp and call-outs of “no spoilers!” Naomi laughed and continued to discuss her ideas without giving away what was yet to come. However, she continued to read ahead each of the remaining days that we worked with “Oreo”. Her shift in reading motivation, which she enacted by choosing to read more than what was expected each day, was facilitated by having successfully comprehended that pivotal moment from the beginning of the text and having more questions and curiosity she wanted to explore. She was able to take on a more liberatory reading motivation because she wanted to better understand the perspectives and experiences of characters she did not immediately relate to.

6. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to illustrate the complex relationship between reading motivation and reading comprehension for Black girl readers. By drawing on a Situative Black Girlhood Reading Motivations (SBGRM) framework, this study addresses the need for reading motivation research that uses a humanizing, asset-oriented lens while centering the experiences of Black girl readers. The findings from this study demonstrate connections between what is known about Black literate communities and Black girl readers, more broadly, and their reading motivations, specifically. The study’s findings also contribute to models of reading by illustrating the need for additional complexity when describing the relationship between reading motivation and comprehension.

6.1. Black Girls’ Reading Motivations

A goal of employing an SBGRM lens in this study of reading motivation and reading comprehension, including centering Black girls’ experiences and creating language that identifies those experiences, is to be able to promote pedagogical approaches in which Black girls are seen, celebrated, and successful [30,31]. The findings from this study illustrate how elements of Black girls’ reading motivations resemble the historical practices and commitments of Black literate communities. These motivations, which have not been attended to in conceptualizations of reading motivation [2,13], suggest the need for expanded notions of reading motivation so that all the ways Black girls are motivated to read can be recognized as valid and productive in research and practice. When these motivations are overlooked, we risk perpetuating deficit views of Black girl readers and misinterpreting how their reading motivations relate to their reading comprehension.

Although skills are central to how we do school [46], Black readers have historically developed skills in service of more ambitious goals [26,46]. The evidence of how students’ meaning-oriented reading motivations related to their reading comprehension supports this notion. The comments offered by Jasmine, Tionna, and Eva regarding the idea of “pushing yourself” and working hard to improve as a reader demonstrate that the pursuit of skills and intellect continues to play a role in motivating Black girls to read. However, like their historical predecessors, the focus was not on developing skills for the sake of having skills. When the girls drew on their meaning-oriented reading motivations, it tended to be a precursor to their comprehension. In other words, they read in order to become better readers so that when faced with a disruption in their comprehension, they could work through challenges and make sense of the text. This focus on meaning making might not be captured in traditional measures of reading motivation [44] that operationalize motivation with constructs such as “recognition” (having others, such as teachers and friends, say you are a good reader) and “grades” (using school grades as a measure of reading success).

Historically, Black readers have engaged in literacy as a collaborative, collective experience. Black readers created spaces and opportunities to read together, in homes, churches, reading rooms, and community schools [26]. They engaged in practices, such as reading aloud and engaging in critical feedback, as a democratic means of sharing texts and expanding opportunities for participation [25,26]. Collective engagement with texts allowed for a deeper and more expansive understanding than what could be achieved independently [28]. Within the “literate community” [29] we co-created in CTC, students demonstrated collaborative reading motivation, which related to their reading comprehension in multiple ways. The students’ conversation about the characters in “Half a Moon” illustrates how being motivated to read to be in community with others functioned as a precursor to comprehension when understanding needed to be repaired. The conversation about “Super Human” shows how collaborative reading motivation works alongside reading comprehension to deepen and expand students’ initial understandings. Finally, the students’ discussion of Patina, which provided Mariella, Sirona, and Keanna with an opportunity to change their reading behaviors, demonstrates one way collaborative reading motivation can follow comprehension of the text. Employing an SBGRM lens in this study, which shifts the unit of analysis from the individual reader to the reader in context, made the students’ collaborative reading motivations visible. This contrasts with standard approaches to studying reading motivation, which tend to take a sociocognitive, quantitative approach [1,11]. Studies tend to focus on the individual, relying on self-report surveys to measure reading motivation and standardized comprehension assessments that seek a singular “accurate” interpretation of texts to measure reading comprehension. In addition, there is a clear tension between collaborative reading motivation and the inclusion of “competition” (outperforming others, being better than others) as a motivation construct [44]. These narrow approaches make it more difficult to capture Black girls’ collaborative reading motivations, contributing to an incomplete picture of why Black girls read.

As Black readers have engaged in literacy throughout history, identity and criticality are essential. They have sought to both understand and express themselves by sharing their experiences and perspectives [26,27]. In the face of racism and oppression, Black readers have always been motivated by the ways that literacy could instill pride, racial solidarity, and racial consciousness. When the students demonstrated their liberatory reading motivations, they were embodying this historical legacy. Using collective pronouns, as exemplified by Lily, Brooklyn, and Ada, was one way in which the students enacted their motivation to read to see themselves and build empathy for others. As their comprehension of the text was developing, they drew on their liberatory reading motivations to deepen and nuance their understandings. As shown by Lily’s reactions to Patina, they brought forth the ways in which they saw themselves reflected in the text to anticipate how a character’s traits might create issues for them later. Brooklyn and Ada’s comments demonstrate how they sought to understand perspectives that did not resonate with their own lived experiences. Attention to social justice and equity was also evident when the students chose to connect developing ideas to societal issues, such as stereotypes of Black women/girls. There has been a lack of attention to the significance of identities, including race and gender, and social contexts in reading motivation research [1,33]. Reading motivation tends to be conceptualized according to the dichotomy of reading for pleasure or reading for academic reasons, which overlooks reasons that might better align with Black girls’ liberatory reading motivations, such as “reading to understand myself”, “reading to understand others”, or even “reading to change the world”.

6.2. Complicating Models of Reading Motivation and Reading Comprehension

In this study, I draw on the DRIVE model of reading [8,14] to conceptualize what it means to read, including reading comprehension and reading motivation. The study findings, however, suggest areas of the model that warrant additional complexity so that it is better equipped to reflect the reading motivations of Black girl readers. While the DRIVE model posits an active reader (the driver), it maintains an individualistic view of reading. The model is constructed around a single driver with a personal destination (individual purpose for reading) and navigating roads (texts) on their own. However, the prevalence of collaboration and the relevance of collaborative reading motivations for the Black girl readers in this study suggest that an exclusive focus on individual readers (drivers) is limiting. Based on the findings of this study, I suggest adding a collaborative element to the DRIVE model.

For some of us, a significant portion of our reading (driving) might be done independently, and thus the model fits well for those experiences. However, as exemplified in this study, for Black girl readers a significant amount of their reading (driving) might be done in collaboration with others. To attend to this, it would be beneficial to add the idea of a carpool to the model. Imagine going on a road trip with a group of your friends. At any given time, one of you is obviously driving, but the others each contribute. Perhaps the front-seat passenger is assisting with navigation, pointing out the exit signs and providing reminders of when to turn. The driver might be able to successfully navigate to their destination without this guidance, but having it alleviates some of the mental load and may make the trip more enjoyable. This is like the interaction between Devin and her reading partner as they worked together to help Devin make sense of the word “roster” in the text.

Perhaps another passenger is responsible for the playlist, adjusting the environment, and setting the tone for the driving experience. With each new song, the vibe in the car shifts, with some songs prompting everyone to sing along and others causing division among the group about whether it should be skipped or not. Students’ collaborative discussions of texts, in which they agreed and disagreed with each other, added nuance and complexity, and worked together to make sense of the text, emulate this notion.

Finally, everyone in the carpool likely contributes logistically and financially to making the trip. When there is a stop to refuel, the costs are shared. Everyone takes turns in the driver’s seat for a stretch of the trip. This shared, collective responsibility for reaching the destination is reflected in Naomi’s experience with the short story “Oreo”. At first, she was a passenger, relying on someone else to do the driving, but coming along for the ride. Once she had a sense of direction, though, and had been shown the way, she was able to jump in the driver’s seat and speed towards the destination. Expanding the model to include options for the reader (driver), including reading independently and reading collaboratively, opens up the possibility of being able to recognize the experiences of a broader group of readers.

In addition to prompting a reimagining of who is in the car in the DRIVE model, the findings from this study also suggest reconsidering the type of car being driven. The DRIVE model [8,14] uses a standard gas-powered car. With this type of car, reading motivation is conceptualized as the ignition, what gets you started, and the gas, what keeps you going. However, in answering the research question, “How are relationships between Black girls’ reading motivations and their reading comprehension evident in their reading engagement and enactments?” the findings of this study add complexity to this conceptualization. To better reflect how Black girl readers’ reading motivations (1) came before comprehension, supporting readers as they worked through moments when comprehension broke down, (2) worked alongside comprehension, supporting readers as they developed deeper understandings, and (3) followed comprehension, supporting readers in demonstrating new or different motivations after comprehending texts, a comparison to a more complex power system is needed.

Replacing the gas-powered car with a hybrid vehicle does not negate the need for ignition or fuel (motivation). It does, however, expand the options for how the vehicle is powered, which reflects the expanded relationships between reading motivation and reading comprehension that emerged in this study. As illustrated in the findings, reading motivation as a precursor to comprehension aligns with the idea of the car ignition and gas as described in the DRIVE model. Although Duke and Cartwright [8] nuance this comparison by stating that motivation is more complex than the “on/off” binary of the ignition, the way these Black girl readers’ motivations supported them in working through breakdowns suggest that more complexity is needed when considering the comparison to gasoline. For example, before and during their drive, drivers need to notice the amount of gas they have in the tank and determine if it is enough to safely get them where they are going. Readers need to pay attention to why they are motivated to read and how that motivation might impact their reading experience. The girls demonstrated this most often in their interviews when asked directly about why they read. For example, when Eva describes motived readers who “mess up a little and…are right a little”, she is suggesting that the road to comprehension is not a linear path but includes bumps and setbacks along the way.

When drivers notice that they are running out of gas, they need to stop and refuel. While refueling, drivers have a choice between the type of fuel they use. They can select regular, mid-grade, premium, or diesel fuel. This relates to the choices readers have in how they repair breakdowns in comprehension. For example, Amika and Devin’s text annotations showed how they utilized their meaning-oriented reading motivation to visualize and ask questions when struggling to comprehend. These decisions may be made based on several factors, including the needs of the vehicle, the cost of each type of fuel, how many more gallons are needed, and so forth. This added complexity to the metaphor of motivation as the ignition and gas in the vehicle, including making choices about when and how to refuel, connects to how the girls leveraged their meaning-oriented and collaborative reading motivations to pause when they noticed their comprehension faltering and used a variety of strategies, depending on the context, to repair it.

Considering a hybrid vehicle adds complexity to the DRIVE model that can better reflect the finding that Black girls’ reading motivations not only preceded their comprehension but also occurred in tandem with their reading comprehension as they worked to add depth and nuance to their understanding of the text. Hybrid vehicles combine a gasoline engine, an electric motor, and a battery pack. At low speeds and under low power demands, the electric motor is the primary power source. However, when you need to accelerate quickly or climb hills, the gas engine kicks in to increase the power. This relationship between the electric motor and the gas engine illustrates the ways Black girl readers in this study leveraged their collaborative and liberatory reading motivations while making sense of the texts. For example, the conversation about the short story “Super Human” offers an example of the “power boost” that a hybrid vehicle experiences. The students had already demonstrated their understanding that X was a superhero who achieved notoriety and fame, but were then faced with the uphill climb of understanding why he no longer wanted to save humanity. Their collaborative reading motivations supported them in climbing this hill and, as evidenced by the students’ annotations later in the text, sustained them so they could reach their destination.