1. Introduction

The premise that the general education classroom offers the optimal learning opportunity is a central and defining principle of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [

1]. Research shows that students who spend less time in general education experience poorer academic and post-secondary outcomes [

2,

3,

4]. These trends are echoed in the international literature on inclusion. In a synthesis of 280 studies examining the effects of inclusive education in 25 countries, Hehir et al. [

5] found strong evidence that students with disabilities (SWDs) academically outperformed those students who were excluded from general education and positive trends in the social and emotional development of SWDs who were included. The concept of Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) requires that SWDs be educated with typical peers to the maximum extent possible [

1]. However, the need to train and retain highly skilled educators to support SWDs in general education is a historically complex and continually pressing issue. SWDs lag behind their peers in graduation rate, academic outcomes, college attendance, and employment and to address these gaps, teachers are the most critical element [

6]. All teachers are responsible for the education of SWDs once they arrive in the classroom, but many SWDs are taught by teachers who lack licensure or are teaching outside of their certification area [

7].

2. Review of the Literature

Teacher shortages in special education have been significant and persistent over time [

8], driven by a lack of qualified candidates and competent teachers leaving the field [

9,

10]. Special education vacancies can be among the hardest to fill and retain [

11]. Within five years of being hired, six out of ten teachers in the state where this study takes place are still teaching, but only five remain in the same district. Movement across jurisdictions contributes to interruptions in services for SWDs and decreased instructional cohesion leads to lower student achievement [

12]. Although teachers may leave because they feel unprepared for the job [

9], there are often insufficient options for affordable, job-embedded training in special education. Teacher retention and turnover comes at a great cost [

9,

12]. Nationally, the turnover rate for special educators can be 46% higher than that of elementary teachers and nearly double the rate of general educators [

13]. The odds of teacher turnover increase with higher percentages of SWDs, with the greatest risk existing among those teaching students with challenging behaviors [

12]. School districts grappling with special education vacancies are often faced with few options for filling these critical positions, as licensure in special education is required [

14]. Recent data show that pathways to increasing the special education workforce are wrought with challenges related to teacher preparation, workforce entry and recruitment, and retention of these individuals in these positions over time [

15], encouraging many to apply economic interventions, such as financial incentives, to address this shortage of teachers in the field [

11].

Today’s classrooms are diverse and the responsibility of teaching SWDs rests squarely upon all teachers, not just special educators [

16]. However, general educators’ preparation to support SWDs is often limited within traditional teacher preparation programs [

17], as general educators report insufficient capacity and resources to serve SWDs [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This raises important questions about how to ensure general educators employ inclusive practices that provide SWDs access to the general education curriculum and meet annual learning outcomes [

6]. Addressing teacher shortages in special education has focused on how to prepare special educators to step into these roles, but less on preparing existing general educators to serve all students [

6]. Pathways to earning licensure in special education differ across locales. In this study context, one state regulation presented an opportunity designed to address teacher shortage by allowing candidates to combine an earned bachelor’s degree with 15 credits (or the equivalent number of credits) in defined special education areas, applicable to educators who previously completed a teacher preparation program which included only minimal instruction in special education.

This intervention serves as an example of a Grow Your Own (GYO) program. GYO models of teacher preparation and professional learning are community-oriented approaches designed to recruit and train local individuals (e.g., career changers, paraprofessionals, or those already employed within schools) to provide them with teacher credentials [

17]. GYO models address teacher shortage, capacity, and retention issues for many reasons. In many geographic regions, it may be easier to recruit and retain local teachers and those who reside in the area tend to mirror the population of students they serve [

17]. GYO programs can improve retention rates in schools, by developing the competency to better navigate challenges that otherwise could result in turnover [

22]. Community-minded teacher learning fosters an organizational approach, often because participants solve school-based problems and take immediate action with direct and positive impact [

22]. While GYO models are promising, the empirical evidence on the efficacy of GYO models is limited [

17], and there are few published findings addressing how these models can be applied to add special education certification endorsement within existing pools of in-service teachers.

3. Purpose

The purpose of this manuscript is to report the initial findings of the pilot implementation of a competency-based continuing education program in special education; describe the school–university partnership that made the design and delivery of the program possible; and outline initial pilot results. Measurement of the intervention’s impact on participants was guided by the following research questions:

Did participants increase their knowledge of the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) standards over the course of the program?

Were participants knowledgeable in the CEC high-leverage practices (HLPs) at the conclusion of the program?

How did program participants rate their self-efficacy to teach in inclusive classrooms, including their (a) efficacy in using inclusive instructions, (b) efficacy in collaboration, and (c) efficacy in managing behavior, at the conclusion of the program?

To what extent did program participants demonstrate competency in special education practice?

4. Conceptual Framework

Research suggests that teachers leave if they perceive they lack training to effectively teach their students [

6]. Research also shows a knowledge and skills gap in general educators’ ability to effectively support the inclusion of SWDs [

19,

21]. Thus, the conceptual framework of this program is based on the interconnectivity between teacher shortage and the competency of general educators to effectively serve all students.

Grossman et al. [

23] discuss adaptive expertise theory as the complex practice of teaching decomposed into learnable steps and practice activities made visible to teachers. Learning to be an effective teacher is rooted not just in knowledge, but in practice [

24], and in self-efficacy [

25]. It is therefore critical that teachers acquire HLPs: the essential tasks and activities skillful educators understand, take responsibility for, and carry out [

24]. Ball and Forzani [

24] indicate that teacher recruitment and retention initiatives are insufficient without a core focus on practice. In 2017, the CEC developed 22 HLPs that address the skills effective teachers use to deliver intensive, specially designed instruction to support SWDs [

26]. For in-service teachers, practice must be job-embedded because appropriating HLPs is dynamic, contextual, and complex due to the individualized needs of SWDs [

27]. The CEC HLPs serve as a framework on which the intervention is based; and the addition of self-efficacy accounts for the intersections between what teachers learn, practice, and feel confident to carry out in the experiences they encounter with students.

5. Theoretical Framework

The Influencing Mindsets, Practitioner Action, and Competency in Teaching (IMPACT) for Students with Disabilities program was developed based on principles drawn from competency-based education [

28,

29], entrustable professional activities [

30,

31], deliberate practice [

32,

33], and the expert-performance approach [

34] literature. Competency-based education was defined in 2011 at the National Summit for K-12 Competency-Based Education and has been redefined since then with feedback from across the education field. Levine and Patrick ([

29], p. 3) published an updated definition of competency-based education which included seven elements:

Learners are empowered daily to make important decisions about their learning experiences, how they will create and apply knowledge, and how they will demonstrate their learning.

Assessment is a meaningful, positive, and empowering learning experience for learners that yields timely, relevant, and actionable evidence.

Learners receive timely, differentiated support based on their individual learning needs.

Learners’ progress is based on evidence of mastery, not seat time.

Learners learn actively using different pathways and varied pacing.

Strategies to ensure equity for all learners are embedded in the culture, structure, and pedagogy of schools and education systems.

Rigorous, common expectations for learning (knowledge, skills, and dispositions) are explicit, transparent, measurable, and transferable.

Simply put, “…competency-based education is nothing more than flexible pacing, or students advancing at their own pace to achieve mastery” ([

29], p. 3). These principles undergird the approach to teacher education that the IMPACT program represents. Competencies for the program were defined using the CEC initial preparation standards and the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) standards [

35]. Although the CEC HLPs help to solidify these standards through learnable steps, coupling the standards and HLPs with a competency-based education framework enhances how teacher preparation programs can effectively teach for application through practice. The skills, knowledge, and dispositions required to master the application of these standards can be vague, general, or abstract, leading to difficulty in assessing how prepared learners are to effectively teach SWDs and it can be difficult for instructors to know what point participants can be entrusted with independent practice.

Entrustable professional activities (EPAs), an emerging education approach used in medical education, are a means of learning design that enable these entrustment decisions within a competency-based education framework [

31]. EPAs focus competency-based learning into discrete activities or performance tasks that are assessable and reproducible in ways that allow teacher educators to make an entrustment decision about when candidates are competent to practice tasks independently. EPAs do not replace competencies but a mechanism to translate competencies into clinical practice as they “bridge the gap between well-elaborated competency frameworks and clinical practice” ([

30], [

31], p. 2; [

36]) EPAs combine the elements of competency-based training, standards-based performance, and autonomous practice through guided, job-embedded learning activities [

37]. The IMPACT program learning activities were developed to situate knowledge associated with these competencies within the daily classroom practice of participants and training activities and the program’s assessments were designed to build skill and self-efficacy while demonstrating and refining these competencies through deliberate practice in classrooms guided by instructors and mentors. Ericsson and Lehmann [

38] defined deliberate practice as “the individualized training activities specially designed by a coach or teacher to improve aspects of an individual’s performance and successive refinement” (pp. 278–279). The IMPACT participants’ performance was successively refined in the program through instructors’ formative feedback and a revision and resubmit process for all summative assessments. This aligns with an expert-performance approach, as Ericsson [

34] indicates that improved performance requires both goal-directed training and immediate feedback; and that knowledge, skill, and confidence gained prior to active practice do not automatically result in changed teacher behavior in the classroom. Rather, changing practices of in-service teachers requires situated feedback, opportunities to practice, and a clear and defined set of practice-based tasks aligned with standards of performance.

6. District University Partnership

The development of this program and the evaluation of its impact occurs within a district–university partnership. The partnership was established to drive fundamental, sustainable, and systemic change for SWDs and their families, following a longitudinal history of poor outcomes for SWDs in the district. The institute of higher education is a large private institution characterized by high levels of research activity in local, national, and international contexts. Within the institution, the development and implementation of this program were conducted by faculty and staff within one of the university’s academic research centers. The school district resides in a small, mid-Atlantic state on the east coast of the United States. The district includes a diverse population of approximately 6500 students in 13 schools, including nearly 40% of whom qualify as low income, 24% identified as SWDs, and 8% who are English language learners.

Longitudinal performance indicators for SWDs in the district show a need for improvement across areas. During the first year of the partnership, members of the university team applied an implementation science approach, conducting a comprehensive landscape analysis of the district’s current practices in special education. The results of the analysis showed that general educators in the district needed continuing, job-embedded professional learning to better meet the needs of their SWDs. Additional fiscal resources were needed to develop and implement the type of intensive, continuing education program that staff required. Therefore, grant funding was obtained to develop and implement a pilot of a continuing professional learning program for teachers that would serve this purpose. Faculty members within the university’s research team led the design and delivery of the pilot program, ensuring alignment to professional standards and requirements for teaching licensure within the state, while district leaders recruited potential participants, messaged this professional learning opportunity to qualified staff, and collaborated with university faculty to support participants’ implementation of the program requirements in their schools.

7. Intervention Description

7.1. Program Overview and Mission

The IMPACT program was designed to serve as a special education certification program for general educators and those in related roles to gain the knowledge and skills to support the inclusion of SWDs. The program’s mission is to create strong, direct, and positive effects on SWDs and their families through teachers’ competency development. Educators solve existing problems of practice, take action to solve these problems, and show evidence that their actions made a positive difference for students and families. The program is a GYO model of teacher professional development, focused on building the capacity of existing staff to serve SWDs and become credentialed in special education. Elements of the program are designed to foster a growth mindset, to encourage participants to consider inclusive environments for SWDs first, to be changemakers in their schools, and to presume competence for all learners.

7.2. Competency-Based Approach to Learning

Unlike traditional learning approaches in higher education, IMPACT applies a competency-based approach. The goal is to create reflective, responsive educators with the knowledge and skills required to meet the needs of all students and to actively demonstrate this through performance-based demonstrations of competency in their professional role. While typical online teacher preparation and professional learning tend to follow a linear format of content delivery, the competency-based approach gave learners tools to create their own, individualized path toward demonstrating competency. For instance, learning modules may have more resources than a learner needs to meet a goal, but the learner is free to select which of these resources best fits their needs to meet with success in the final module assessment(s), which is referred to as a competency demonstration. In a competency model, actions speak louder than words or clock-hours in training. To exemplify competency, learners demonstrated knowledge through performance assessments and reflective practice aligned with professional standards. Learning was active, rather than passive. Learning experiences were crafted to invite, challenge, strengthen, and transform one’s thinking and actions. In turn, competent educators gain the knowledge and skills that result in positive outcomes for students and families, but they choose a path for learning that contributes to their own personally designed success.

Overall, competency in special education in IMPACT is comprised of four component parts, in alignment with the program’s theoretical framework: (1) knowledge of the CEC initial preparation standards, (2) knowledge of the CEC HLPs, (3) self-efficacy to apply inclusive practices in the classroom, and (4) the application of new knowledge and developed self-efficacy to an authentic context. Therefore, the program’s critical design features and embedded assessments comprehensively address each of these components.

7.3. Scope and Sequence

IMPACT includes a five-module sequence that involves direct instruction and coaching to support learners to demonstrate competency in the following: (1) Introduction to Special Education and Collaborative Teaming, (2) Curriculum and Instruction in Special Education, (3) Diagnosis and Instruction for Reading, (4) Applied Behavior Analysis, and (5) Educational Evaluation and Individualized Education Program (IEP) Development. Each module included 90 clock hours of asynchronous, self-paced instruction, equivalent to nine continuing education units (CEUs) from the institute of higher education. To earn CEUs, participants completed the requirements outlined in each module syllabus and earned the minimum passing score on each of the five competency demonstrations, which served as summative assessments in each topic area. The program was designed to prepare educators for achieving state certification in special education, upon successful completion of program requirements and meeting the minimum required passing score on the Praxis II in Special Education.

Table 1 provides an overview of the scope and sequence of the program, including key module topics.

7.4. Delivery Mode

The IMPACT program was delivered using a cohort model, made up of pairs or teams of coaches and teachers from a school whenever possible. School administrators, deans, and other certificated educators who meet the admission criteria were also admitted. Participants completed the program within one academic year, starting either in September or in January. Coursework was provided during the school year so that participants had daily opportunities for job-embedded practice. Learning within the cohort was an important part of the program experience, designed to provide both an opportunity and a social responsibility to collaborate with colleagues by asking questions, sharing resources, seeking assistance, and offering peer coaching and mentoring. Modules were delivered using a hybrid approach, including both asynchronous learning and three synchronous online cohort meetings during each module.

7.5. Components of a Learning Module

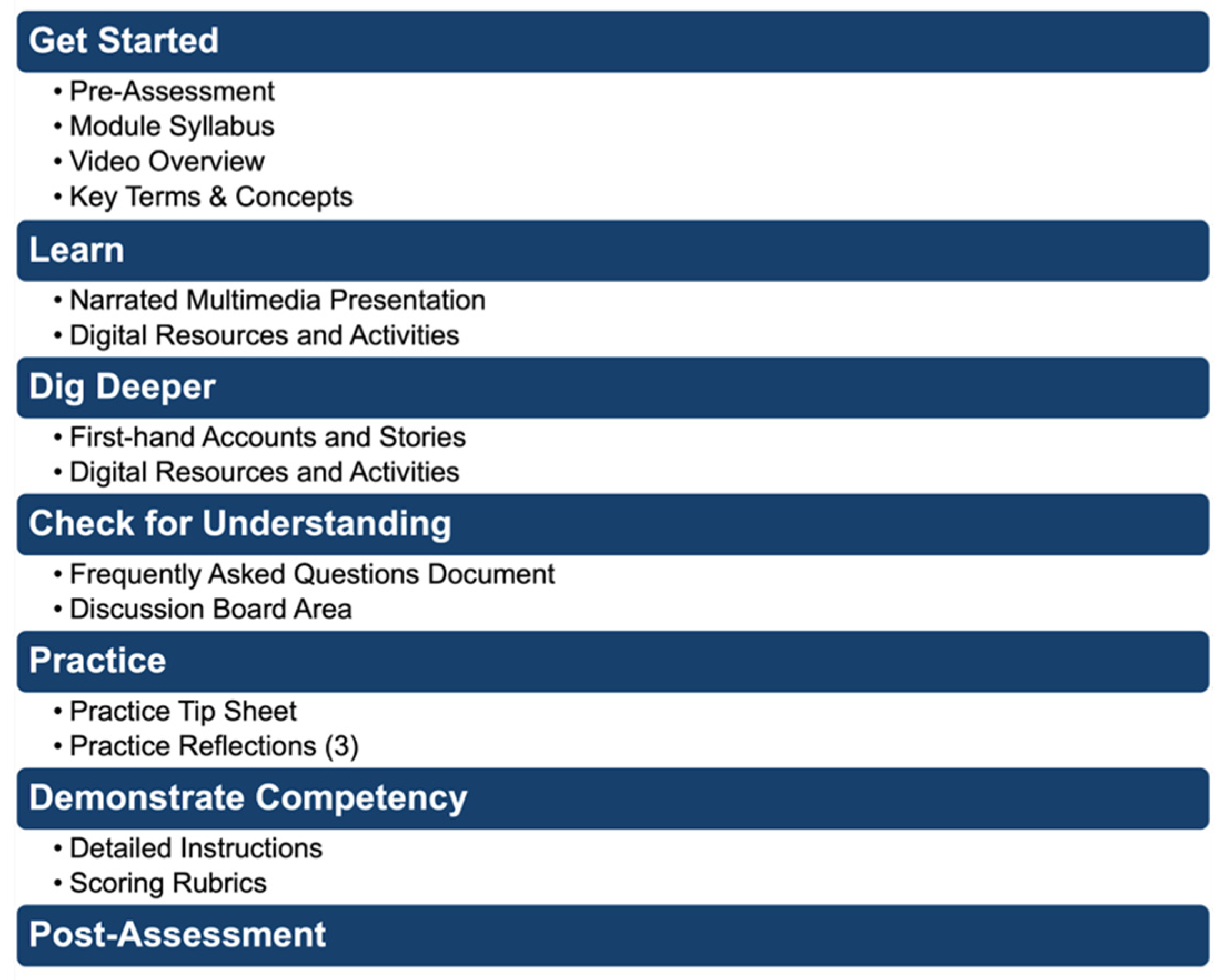

Each learning module was six weeks in length and offered in a learning management system (LMS). Syllabi detailed learning outcomes, alignment to the professional standards, instructions to students, a schedule, and evaluation components.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the learning experience within each six-week segment of instruction.

7.6. Program-Embedded Assessments

At the start of each module, participants completed a pre-assessment to evaluate their current knowledge and skills in the identified topic areas aligned with the CEC standards. At the culmination of the module, learners completed a post-assessment and were asked to evaluate the effectiveness and usability of module content. In each post-assessment, learners provided examples of how their new learning had impacted SWDs and the staff who served them. During pilot implementation, this feedback was critical to make the necessary refinements to improve the program for current and future participants.

Over the course of the program, participants completed five summative assessments, referred to as competency demonstrations. Each competency demonstration presented the participant with a universally applicable problem of practice that they addressed in their classroom, school, or district, depending on their professional role. To address each problem of practice in their specific context, participants completed competency actions, defined as the observable and measurable steps to help solve the problem. Since it was unlikely that problems could be completely solved within the short timeframe, participants were encouraged to consider small, yet meaningful steps that allowed them to make incremental progress toward solving the problem. For example, they were asked to address the literacy or behavioral needs of a student by applying a short-term intervention. Following implementation, the participants reflected and provided evidence that their actions have had a positive and meaningful impact on either the student, their colleagues, or the family members of a student they served. This involved providing supporting documents, such as feedback from members of the IEP Team, student artifacts, or progress monitoring data. Because these assessments were designed to measure both the competency development of the professional and positive impact on students and families, flexibility was afforded to provide participants with multiple attempts to demonstrate competency over time, even after a module had concluded. For instance, if the participant’s model lesson showed that students did not meet the intended learning objectives, the participant was given the opportunity to re-teach the lesson and make iterative changes in response to students’ needs during their first attempt. This growth-oriented mindset to competency demonstration was a defining principle of the IMPACT program, prioritizing not only the growth of the candidate but also of the various stakeholders they serve. Finally, because the program is based on the position that competency develops over time and through strategic intent, participants reflected on their current and future competency growth.

8. Methods

The authors received a grant to conduct a two-year pilot implementation of IMPACT within one district, with funds used to develop the program, deliver it to two cohorts of professionals, and conduct a program evaluation. During this timeframe, the program was approved by the state’s education agency as an alternative pathway to special education certification. In addition to iterative design and implementation feedback with participants, the measures designed and implemented as part of the program evaluation measured participants’ knowledge of the CEC standards and HLPs, self-efficacy to teach in inclusion classrooms, and the extent to which participants demonstrated the minimum levels of competency identified as critical to special education practice. To conduct the study, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained, and human participant protections were followed, as required.

The pilot took place in a small, yet diverse school district that includes both urban and rural areas. More than 50% of the district’s enrolled students are African American and 25% are White, with the remainder of the approximately 6500 students comprised of other or multiple races and ethnicities. At the start of the pilot, the district educated just half of its school-aged SWDs in LRE A; therefore, a focus on inclusive practices was of high priority to district leaders in the development and implementation of the program.

8.1. Participant Demographics

At the onset, 35 pilot participants were enrolled and admitted to the program following an outlined admission process which ensured that individuals were eligible for special education certification in the state. This included 14 professionals originally admitted to Cohort 1 and 2 professionals admitted to Cohort 2. Over the course of the two-year pilot, attrition occurred in both cohorts, with some participants citing their struggle to balance full-time professional obligations with the intensity of a one-year program. Additionally, implementation of the pilot within proximity of the COVID-19 pandemic caused some participants to cite extenuating circumstances that required them to either transition to another school or accept another role that prevented them from implementing competency demonstrations. Overall, 22 participants persisted and successfully completed the program to earn special education certification with the state.

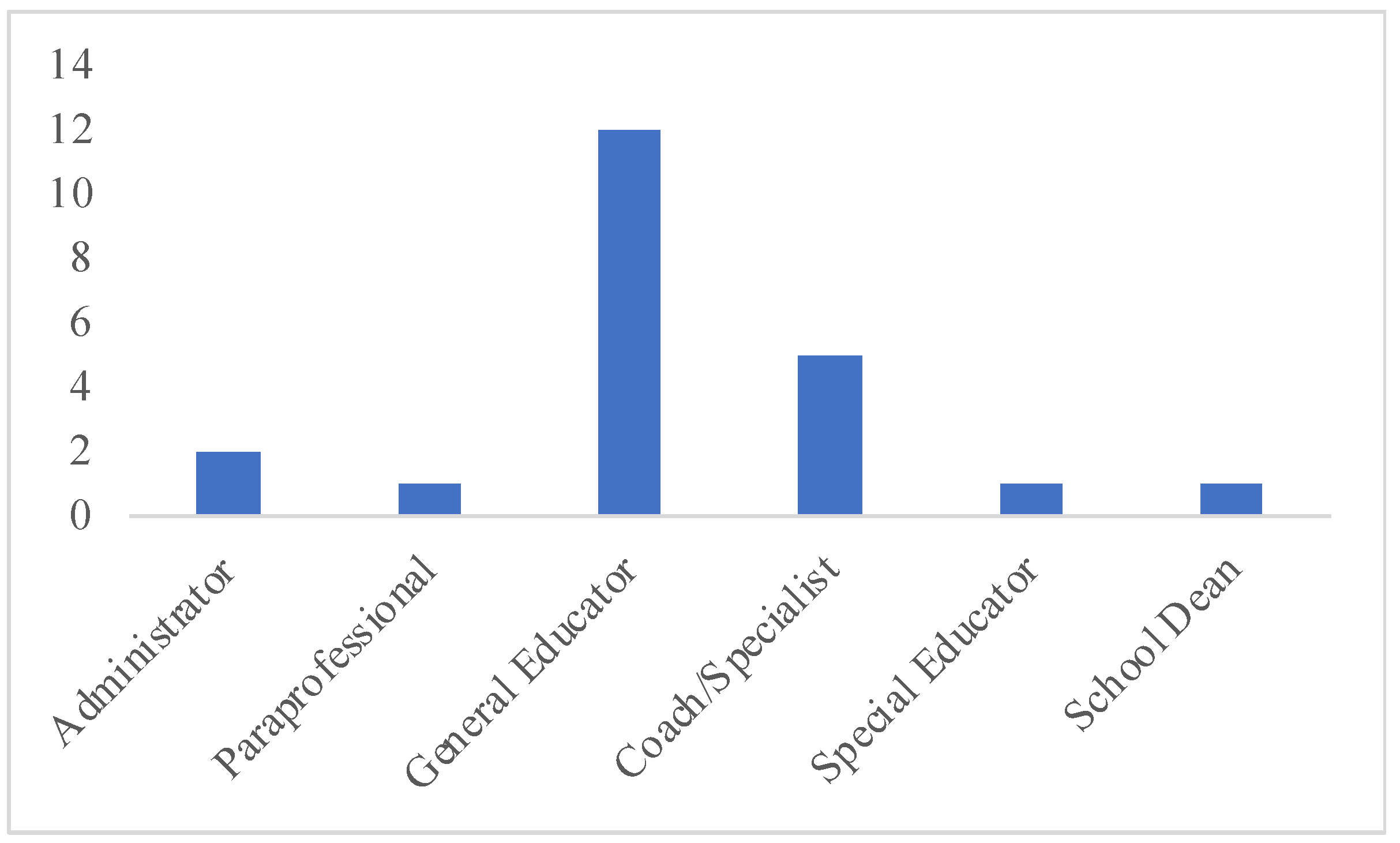

Figure 2 shows the professional roles and years of experience among the 22 participants who completed the program.

Most of the participants were general educators seeking special education certification (

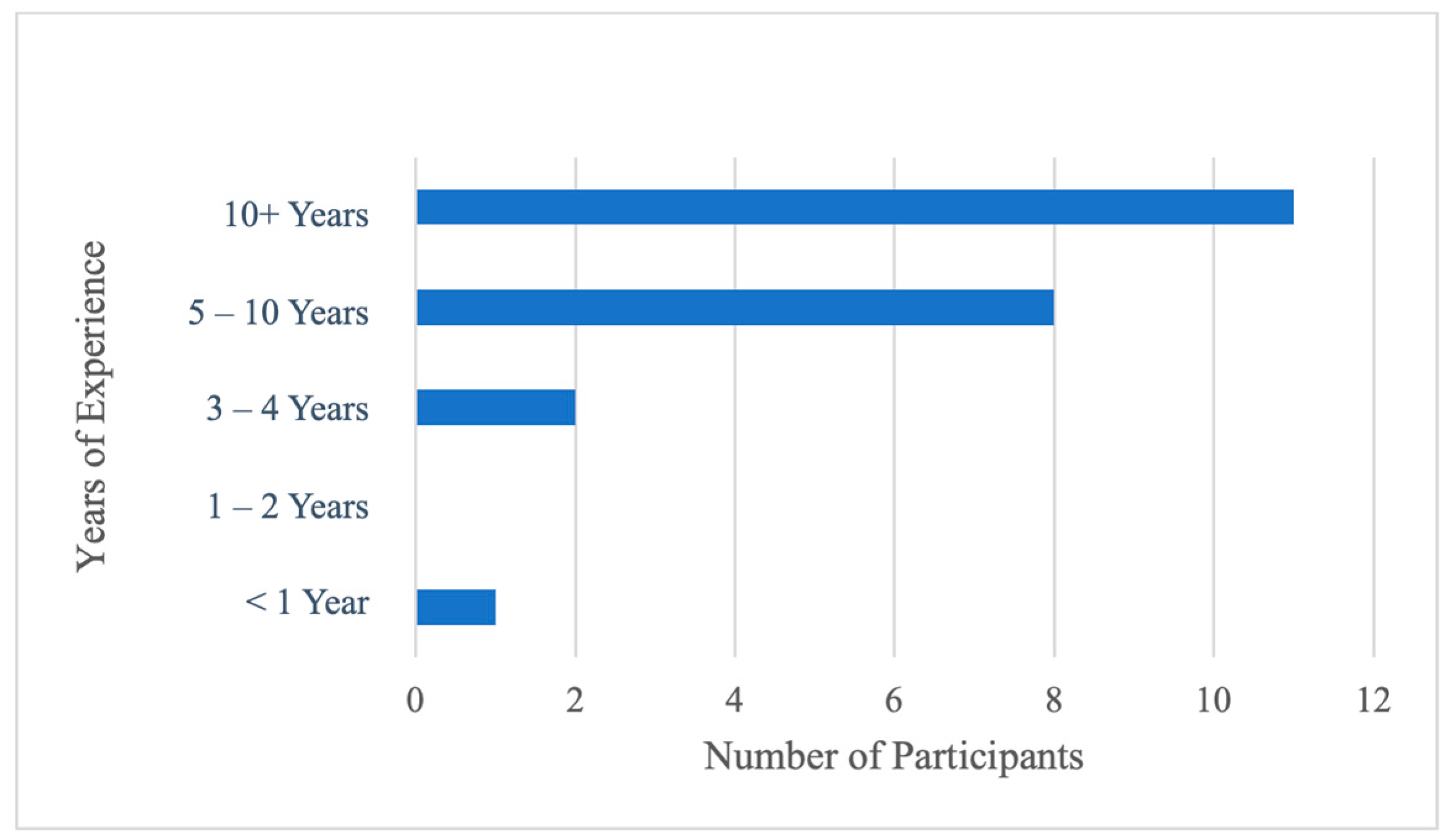

n = 12). Five participants were instructional coaches or content-specific specialists designed to provide instructional support to classroom teachers and other participants served as administrators, paraprofessionals, those working as special educators but were not yet certified, and school deans. The years of experience among pilot participants varied, though most were experienced teachers. Upon entry into the program, eleven participants had more than 10 years of teaching experience and eight participants had between five and 10 years of experience.

Figure 3 shows the range of experience among those who participated in the pilot cohorts.

8.2. Data Collection

Data were collected at various points, using a combination of validated and author-developed instruments. At the onset, participants completed a Beginning of Program Survey which collected demographic information, reasons for applying to the program, perspectives on learning styles and preferences, and current knowledge of the broad topics addressed in the scope and sequence. At the conclusion, participants completed an End of Program Survey which addressed multiple research questions outlined in the program evaluation framework.

To measure the first research question, participants’ knowledge of the CEC initial preparation standards was assessed using author-developed module pre- and post-assessments. These online surveys, delivered to participants in the LMS at the start and conclusion of each module, included multiple-choice and open-ended response items to measure participants’ knowledge of module learning objectives. In addition, the pre-assessment contained additional items which allowed participants to set short-term goals for their competency development and the post-assessment contained items that assessed evidence of impact and user experience within each learning module.

To address the second research question, participants were administered the Teacher Knowledge of High-Leverage Practices [TKHLP; [

39]] within the End of Program Survey. The TKHLP “is an assessment tool designed to measure teachers’ understanding of the 22 HLPs that underlie evidence-based practices for special education teachers” ([

40], p. 1). The TKHLP has excellent content validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) and includes 19 items employing various question types (e.g., multiple choice, single choice, open-ended questions). Each item is scored from 0 (no knowledge) to 3 (extensive knowledge) and the average of all items is used to represent teachers’ collective knowledge of the CEC HLPs [

40].

To address the third research question, participants’ perceived capacity to implement inclusive practices was measured using the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices [TEIP; [

41]]. The TEIP has been widely used with excellent reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha 0.84~0.91) [

41] and validity [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. The TEIP contains 18 items measured using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) with three sub-scales: self-efficacy to use inclusive practices, to collaborate with other professionals, and to manage disruptive behaviors of students. The total score of each subscale can thus be used to represent each self-efficacy construct.

Participants’ competency development, the final research question, was measured using author-developed scoring rubrics designed specifically for the competency demonstration in each learning module. Elements of each demonstration were scored using a 3-point Likert scale (1 = limited competency development, 2 = emerging competency development, 3 = breakthrough competency development), outlined in a detailed scoring rubric designed for both participants and program staff who served on a scoring panel. Each scoring rubric contained the following common elements: (a) competency actions, (b) impact measures, (c) artifacts, (d) evidence of new learning, (e) professionalism, integrity, and confidentiality, and (f) a competency reflection including a summary of their ability to address the problem, personal growth, and plans for continued competency development. To earn CEUs and successfully complete each module, participants were required to earn a score of two in each component of the scoring rubric. Using a panel review process, individual elements of each demonstration were scored and agreement among at least three panel members was required to achieve a final score. Participants who earned a score of 1 in any area were afforded the opportunity to revise and resubmit their demonstration after taking new or additional actions to address the problem of practice more comprehensively.

9. Results

9.1. Teacher Knowledge of CEC Standards

Participants’ knowledge of the CEC standards was measured using a pre- and post-assessment disseminated at the beginning and end of each six-week module. The points possible for each assessment varied between 100 and 220 (Module 1 = 130, Module 2 = 100, Module 3 = 220, Module 4 = 132, Module 5 = 150). For each cohort, we conducted a set of paired t-tests to examine whether the differences in pre- and post-module scores were statistically significant. In Cohort 1, the number of cases used for paired t-tests differed (N = 11 or 12) because there were missing values in three of the module datasets due to non-response from participants. Within Cohort 1, all pre- and post-module differences were statistically significant, indicating that the participants’ improvements in the post-module scores were statistically significant. In Cohort 2, the number of cases used for paired t-tests also differed (

n = 9 or 10) because there were missing scores from three of the datasets. In Cohort 2, the pre- and post-module score differences were statistically significant in Modules 1, 3, 4, and 5, indicating that the participants’ improvements in the post-module scores were statistically significant. The pre- and post-module score difference in Module 2 was not statistically significant. These results are provided in

Table 2.

9.2. Teacher Knowledge of CEC High-Leverage Practices

Participants’ knowledge of the CEC HLPs was measured using the TKHLP, at the conclusion of the IMPACT program. Results are provided in

Table 3. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the main features of this dataset for all participants in the pilot, including participants’ knowledge of all 22 CEC HLPs collectively and for each of the four HLP domains: collaboration, assessment, social/emotional/behavioral, and instruction. Knowledge scores are based on the instrument’s three-point Likert scale, whereby 3 = extensive knowledge, 2 = some knowledge, and 1 = limited knowledge. In aggregate, participants’ knowledge of all 22 CEC HLPs was 2.32, with these data clustered tightly around the mean (SD = 0.25). Individual participants’ mean scores for all items on the TKHLP ranged between 1.53 and 2.63, with only one participant earning a mean score below 2.0.

Participants’ mean scores for each of the CEC HLP domains ranged between 2.21 and 2.52. Standard deviations ranged between 0.38 and 0.58. Participants exhibited the highest mean score in the assessment domain (2.52), closely followed by collaboration (2.51). In the area of assessment, participants scored highest in identifying multiple sources of assessment to identify the strengths and needs of SWDs. In collaboration, participants received the highest scores in identifying the critical elements involved in leading effective IEP Team meetings. The lowest overall domain mean score was in knowledge of social/emotional/behavioral HLPs, at 2.21. The item that received the lowest scores (mean = 1.27) asked participants to identify components of an individualized goal for students.

Results on the TKHLP were disaggregated based on participants’ years of teaching experience and their professional roles. Data for any results representing less than five participants were suppressed, due to the small sample size. The total mean scores for participants between five and 10 years of experience were 2.3 and for those with 10 or more years of experience, mean scores were similar at 2.31. The mean score for the participant with less than one year of teaching experience was suppressed due to sample size; however, a two-tailed t-test indicated that the mean score of this new teacher was not statistically different than the mean scores of those with more years of experience, as there was not a significant

p-value at the 5% level between the variables. This echoes the findings of Firestone et al. [

39], who found no linear relationship between years of teaching and HLP knowledge. Similar results were found when data were disaggregated by professional role. Mean scores of instructional coaches and general educators were evenly matched, ranging from 2.91 to 2.31, respectively. All disaggregated data in HLP knowledge, both by years of experience and professional role, showed standard deviations ranging between 0.24 and 0.28.

9.3. Self-Efficacy for Inclusive Practices

Participants’ perceived capacity to implement inclusive practices was measured using the TEIP at the conclusion of the program. Total scores of each subscale are intended to represent each self-efficacy construct: efficacy to use inclusive practices, to collaborate with other professionals, and to manage disruptive behaviors of students.

As seen in

Table 4, results showed some variation in perceived efficacy between Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 across subscales, though the scores were comparable. Cohort 1 had higher perceived efficacy scores in all three subscales. The use of inclusive practices and collaboration subscales were comparable in terms of average score and variation, though Cohort 1 had slightly higher scores and lower variation in both subscales. Of note, the managing behavior subscale had both the lowest mean scores and the highest variation among participants.

Examining efficacy results within each subscale showed that participants perceived themselves as more effective at a range of practice activities associated with the use of inclusive practices and collaboration than they did at managing disruptive behavior (shown in

Table 5). Among all participants and within the use of the inclusive practices subscale, participants rated themselves as most effective at providing additional examples when students are confused (5.77), gauging comprehension (5.55), providing appropriate challenge (5.50), and getting students to work together (5.50). Within the collaboration subscale, participants rated themselves as most effective at working jointly with other professionals to teach SWDs (5.50), and least effective at getting parents involved in school activities with their SWDs (5.23), the largest within-subscale variation. All items in the managing behavior subscale had lower scores than items within the other two subscales. Among all participants, the highest average score in the managing behavior subscale (5.18) was lower than the participants’ average scores on all other items in the other two subscales.

9.4. Application of Knowledge to the Classroom

Participants’ ability to synthesize the knowledge they had gained and apply new skills in an authentic classroom setting was assessed through the completion of a competency demonstration at the end of each module. Module content was organized around five problems of practice, listed in

Table 6. These demonstrations were constructed to align with the learning outcomes of their corresponding module. Participants received scores of 1, 2, or 3 on rubric components. A score of 1 on any element of the rubric indicated that the participant must revise and resubmit the competency demonstration. Competency demonstrations were designed to provide multiple ways for participants to show their knowledge and skills. Each assessment required participants to establish the need and adequacy of fit for the selected intervention and then demonstrate their learning in action by providing multimedia artifacts of instruction and analysis of student data and/or work samples. Processes were in place to ensure student-identifiable information was not included in any submitted artifacts. As with the content, each competency demonstration built upon the knowledge of the previous module, culminating with the development of a K-12 student’s IEP, the cornerstone of the special education process, as the final assessment in Module 5. Resubmission of an assignment was recorded but did not detract from the participant’s final score. Final scores for participants in Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 are available in

Table 7.

Overall, minimal variability is evident in participant scores within and across cohorts. The ability of participants to resubmit competency demonstrations impacted the range of scores, as a minimum score of 2.0 was required for each element of the rubric, and the highest score value was 3. Participants scored highest in Module 3: Curriculum and Instruction in Special Education, with a combined mean of 2.93. This competency demonstration required participants to identify a student struggling in reading, collect baseline data using multiple and varied sources, design and implement a reading intervention, and analyze outcome data for a student in their classroom or school. Participants scored lowest in Module 4: Applied Behavior Analysis. The culminating activity for this competency demonstration required participants to identify a student struggling with an interfering behavior, collect baseline data, design, and implement an intervention to teach an alternative behavior, and analyze outcome data. A feature of the IMPACT program was the opportunity for candidates to revise competency demonstrations if they scored a 1.0 in any component of the rubric. In each cohort, in each module, there were one to two participants who were required to revise and resubmit their competency demonstration to earn the scores represented in

Table 7.

10. Discussion

10.1. Implications for Teacher Preparation and Special Education

Nationwide, special education teacher shortages are troubling [

47]. Special education teacher vacancy rates have been shown to be as much as four times higher than elementary-level positions [

48] and special education teachers have been shown to leave at much higher rates than general education teachers [

12] leading many districts to hire uncertificated long-term substitutes, or teachers on limited or emergency certificates. Even fully certificated and qualified special education teachers can be unprepared for district expectations [

49,

50,

51]. Multiple, novel ways of preparing and inducting special educators are needed in cooperation with districts; and more than one solution is needed. This GYO program was not intended to take the place of a complete educator preparation program, and this type of program should not be a candidate’s only option. Rather, this intervention was designed to address one potential pathway for recruiting special educators and tailoring job-embedded, competency-based education to certify existing general educators for special education. The results of this pilot provide indications about how GYO preparation programs for certifying general education teachers for special education placements can be designed and supported to be effective.

Participants in this study entered the IMPACT program with previous classroom experience and their own understanding of instructional and classroom management practices in the general education classroom. Initial pilot data indicate that the most difficult essential skill for participants to learn and apply was the effective planning and implementation of social-emotional learning and behavioral interventions for SWDs. Gilmour and Wehby [

12] state that teachers are more likely to leave the field when they have higher numbers of students with challenging behaviors in their classroom, signifying that SEL and behavior management are areas of importance for teacher preparation programs to consider.

Participants’ self-efficacy to implement inclusive practices was typically higher than their demonstrated HLP knowledge. Highly effective educators typically identify skills for improvement, while new special educators (though they have previously been in general education classrooms), may unintentionally overstate their self-efficacy scores. It is difficult for the novice to make a comparison between what they know and what they need to know. Thus, teacher preparation programs may consider providing opportunities for deliberate practice and reflection to improve both knowledge and application of special education skills prior to program completion, as well as opportunities for mastery through summative assessments such as the IMPACT competency demonstrations.

Though participants engaged in asynchronous learning, three synchronous class discussions, and applied new learning within five contextual demonstrations, this level of engagement is merely a start to building teacher competency, especially within complex areas such as SEL and behavior management. Not only did participants score lower in the HLP knowledge SEL domain, but they also rated themselves lower in self-efficacy in the managing behavior subscale of the TEIP. Additionally, participants chose less intense behaviors to address for the competency module assignment than the types of behavior examples listed in the self-efficacy scale. Through these results, we infer that educators deem themselves better able to practice newly acquired SEL and management competencies to behaviors they see as less challenging or complex, but that they need additional opportunities to increase their self-efficacy in addressing disruptive or aggressive behaviors in the classroom.

Self-efficacy can be improved through persistent practice and mastery experiences [

52]. The IMPACT competency demonstrations provided participants with mastery experiences through the cycle of revision, resubmission, and coaching until mastery was achieved. However, this supportive scaffolding may be a reason teachers had elevated levels of self-efficacy for inclusive practices when compared to their knowledge scores. Traditional teacher preparation programs may consider expanding upon the current, end-of-program student teaching experience by providing more frequent, in-school experiences coupled with informal observations and coaching to improve practice until mastery is met for more complex skills such as behavior management. This type of entrustable professional activity takes time, which is one of the primary challenges our profession currently faces. As a community of educators, we must ask ourselves how we can adjust current practices to meet the challenge of the teacher shortage while also holding ambitious standards for competency among new special educators. Learnings from this pilot may be used to contextualize how to train general education teachers in special education best practices.

To promote cohesion, districts may consider developing GYO programs in alignment with already existing systems of teacher induction and coaching support. It is important for districts to consider opportunities to build the capacity of district staff as in-house experts for the sustainability of a GYO model. Ongoing partnerships between institutes of higher education and school districts, even after a program has concluded, are an additional mechanism for providing the intensive support required to initiate and maintain a successful GYO program.

Within these study data, one limitation of participants’ knowledge emerged; that is, although participants significantly improved in their knowledge of CEC standards between pre- and post-measures, the resulting post-assessment cohort mean was lower than we might expect or might be required in a traditional teacher preparation program. However, despite these post-assessment scores, participants routinely demonstrated competency to apply knowledge of the standards through the summative assessments and demonstrated knowledge of the CEC HLPs when measured.

10.2. Implications for Policy and Research

There are questions specific to the IMPACT program that warrant further examination. First, these initial results lead us to evaluate how and to what extent the program’s curriculum and/or post-assessment measures might be refined to improve participants demonstrated rote knowledge of the CEC standards. Additionally, with future participants, there may be value in investigating how the program could be refined to increase the practice opportunities provided to participants in managing students’ behavior, with the intent of increasing teachers’ self-efficacy to manage disruptive behaviors in the general education classroom. Finally, collecting additional, longitudinal data, from these participants would allow us to address whether the program was successful in supporting the retention of teachers in the district or state and how participants continue to apply and develop competency over time.

The results of this study also have implications for research related to teacher preparation and in-service teacher training that lies outside of the scope of the IMPACT program. For instance, additional research is needed on valid means for measuring teachers’ knowledge of the CEC HLPs. This use of the newly developed TKHLP measure adds to this growing body of research, but replication using this measure and others like it is necessary to better understand the results we might expect among general educators new to special education content and coursework. Additionally, further empirical studies are needed to measure the impact of GYO programs in a variety of formats, including how these approaches affect both teacher and student performance over time. Lastly, since this program emphasized the inclusion of SWDs, the goal is to use educational training opportunities to positively influence more professionals to consider less restrictive environments for their SWDs. Research has generally focused on the impact of programs to influence teacher participants’ self-efficacy or their attitudes and beliefs relative to the students they serve, but in addition, we need further interrogation as to whether teacher preparation programs are graduating candidates whose shifting mindsets also result in less restrictive placements for their SWDs. For example, how do the placement decisions or recommendations of participants prior to training compare to the LRE decision-making practices of these participants following their education? How and in what ways do the exit data of teacher program participants yield changes in a district or state’s LRE data, leading to greater levels of inclusion for SWDs?

In this time of teacher shortage, it is critical that state and local policies be developed and implemented in ways that support innovation in recruiting and retaining teachers who are effective and motivated to support diverse populations of students, including those with disabilities. Forward-thinking state policies are those that promote multiple pathways to enter the teacher workforce, including traditional teacher preparation programs, alternative route programs, and other, unique paths to certification since as the one described in this pilot. These varied options support an infrastructure that allows those to enter the field through mechanisms that are personally necessary, timely, and intrinsically motivating based on their professional and personal goals. However, to enact these pathways, both state and local educational agencies must have the resources necessary, including funding, to support partnership programs with tailored in-service teacher professional development. Partnerships and Memoranda of Understanding which establish ways to earn degrees is one pathway, but it is not the only pathway available to actualize innovative programming. State policies should incentivize teachers to pursue additional post-graduate education (such as through salary increases) toward all types of programs, not just those that lead to master’s and doctoral degrees.

11. Conclusions

It is essential that universities and districts continue critical conversations and ongoing partnerships to ascertain how state, district, and school-level administrators can encourage more highly effective general education teachers to become certificated in special education, while simultaneously supporting the retention of the educators who make this investment. When we view the need for general educators and special educators as separate or binary issues, we run the risk of creating division that only exacerbates teacher shortages within a school or district. Collectively, programs like IMPACT are designed to allow leaders to strategize ways to utilize their existing workforce to address such gaps, holding the common vision that the need to support SWDs rests squarely upon all educators. Through this approach, unique and tailored preparation programs can be designed to foster effective workforce mechanisms that jointly address this pressing issue that many districts face.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.H.-B. and N.G.; Methodology, N.G.; Formal Analysis, A.R.H.-B. and N.G.; Investigation, A.R.H.-B. and N.G.; Resources, A.S.; Data Curation, A.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.R.H.-B.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.R.H.-B., N.G. and A.S.; Visualization, N.G.; Supervision, A.R.H.-B.; Project Administration, A.R.H.-B.; Funding Acquisition, A.R.H.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The pilot and development of the IMPACT program was funded by The Longwood Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with all ethical practices and conduct required for research containing human subjects and approved by Johns Hopkins University Homewood Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to the requirement to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of participants in the study, as required by the Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400. 2004. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statuteregulations/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Cole, S.M.; Murphy, H.R.; Frisby, M.B.; Grossi, T.A.; Bolte, H.R. The relationship of special education placement and student academic outcomes. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 54, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.M.; Murphy, H.R.; Frisby, M.B.; Robinson, J. The relationship between special education placement and high school outcomes. J. Spec. Educ. 2022, online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, E.; Sanford, C.; Blackorby, S. A National Profile of the Classroom Experiences and Academic Performance of Students with Learning Disabilities: A Special Topic Report from the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study. 2008. Available online: https://www.seels.net/info_reports/SEELS_LearnDisability_%20SPEC_TOPIC_REPORT.12.19.08ww_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Hehir, T.; Grindal, T.; Freeman, B.; Lamoreau, R.; Borquaye, Y.; Burke, S. A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education; Abt Associates: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.abtassociates.com/sites/default/files/2019-03/A_Summary_of_the_evidence_on_inclusive_education.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Blanton, L.P.; Pugach, M.C.; Boveda, M. Interrogating the intersections between general and special education in the history of teacher education reform. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahan, M.P.; Olivier, D.F.; Wadsworth, D.E. Fostering special education certification through professional development, learning communities and mentorship. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2015, 142, 157. Available online: http://aasep.org/aasep-publications/journal-of-the-american-academy-of-special-education-professionals-jaasep/jaasep-winter-2015/fostering-special-education-certification-through-professional-development-learning-communities-and-mentorship/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do about It; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Carroll, T.G. Policy Brief: The High Cost of Teacher Turnover; National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498001.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- McLeskey, J.; Tyler, N.C.; Flippin, S.S. The supply of and demand for special education teachers: A review of research regarding the chronic shortage of special education teachers. J. Spec. Educ. 2004, 38, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A.F.; Theobald, R.; Nathan, D.J. Economic interventions as policy levers for attracting and retaining special education teachers. In Handbook of Research on Special Education Teacher Preparation, 2nd ed.; McCray, E.D., Bettini, E., Brownell, M.T., Sindelar, P.T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, A.F.; Wehby, J.H. The association between teaching students with disabilities and teacher turnover. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.C.; Jones-Goods, K.M. Identifying and correcting barriers to successful inclusive practices: A literature review. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2016, 64, 71. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1129815 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Kamman, M.; Sindelar, P.; Hayes, L.; Colpo, A. Short-Term Strategies for Dealing with Shortages of Special Education Teachers; United States Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Short-Term-Strategies-for-Dealing-With-Shortages-of-Special-Education-Teachers.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Theobald, R.J.; Goldhaber, D.D.; Naito, N.; Stein, M.L. The special education teacher pipeline: Teacher preparation, workforce entry, and retention. Except. Child. 2021, 88, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, D.R.; Alexander, M. Investigating special education teachers’ knowledge and skills: Preparing general teacher preparation for professional development. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallona, C.; Johnson, A. Approaches to Grow your Own and Dual General and Special Education Certification; Maine Education Policy Research Institute: Gorham, ME, USA, 2019. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596246.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Kaczorowski, T.; Kline, S.M. Teacher perceptions of preparedness to teach students with disabilities. Mid-West. Educ. Res. 2021, 33, 36–58. Available online: https://www.mwera.org/MWER/volumes/v33/issue1/MWER-V33n1-Kaczorowski-FEATURE-ARTICLE.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Koh, M.; Shin, S. Education of students with disabilities in the USA: Is inclusion the answer? Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2017, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, P. Teachers’ knowledge of special education policies and practices. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2015, 207, 234. Available online: http://aasep.org/aasep-publications/journal-of-the-american-academy-of-special-education-professionals-jaasep/jaasep-fall-2015/teachers-knowledge-of-special-education-policies-and-practices/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Stites, M.L.; Rakes, C.R.; Noggle, A.; Shah, S. Preservice teacher perceptions of preparedness to teach in inclusive settings as an indicator of teacher preparation program effectiveness. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2018, 9, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, C.D.; Bianco, M.; Lynn, M. Examining grow your own programs across the teacher development continuum: Mining research on teachers of color and nontraditional educator pipelines. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Hammerness, K.; McDonald, M. Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.L.; Forzani, F.M. The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M.; Koomen, M.Y. Teacher self-efficacy and its effect on classroom processes, student academic achievement, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J.; Barringer, M.D.; Billingsley, B.; Brownell, M.; Jackson, D.; Kennedy, M.; Ziegler, D. News from CEC: High-leverage practices in special education. Teach. Except. Child. 2017, 49, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppar, A.L.; Roberts, C.A.; Olson, A.J. Developing expertise in teaching students with extensive support needs: A roadmap. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 56, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, C.; Patrick, S.; Pittenger, P. It’s Not a Matter of Time: Highlights from the 2011 Competency-Based Learning Summit; International Association for K-12 Online Learning and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO): Vienna, VA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://learningedge.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/iNACOL_Its_Not_A_Matter_of_Time_full_report.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Levine, E.; Patrick, S. What is Competency-Based Education? An Updated Definition; Aurora Institute: Vienna, VA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://aurora-institute.org/resource/what-is-competency-based-education-an-updated-definition/ (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- ten Cate, O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Cate, O. A primer on entrustable professional activities. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2018, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Roring, R.W.; Nandagopal, K. Giftedness and evidence for reproducibly superior performance: An account based on the expert performance framework. High Abil. Stud. 2007, 18, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Tesch-Römer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A. Acquisition and maintenance of medical expertise: A perspective from the expert-performance approach with deliberate practice. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2015, 90, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Chief State School Officers. Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards and Learning Progressions for Teachers 1.0: A Resource for Ongoing Teacher Development. 2013. Available online: https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/2013_INTASC_Learning_Progressions_for_Teachers.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- ten Cate, O.; Scheele, F. Competency-based postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad. Med. 2007, 82, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.; Young, C.J.; Hong, J. Implementing entrustable professional activities: The yellow brick road towards competency-based training? ANZ J. Surg. 2017, 87, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Lehmann, A.C. Expert and exceptional performance: Evidence of maximal adaptation to task constraints. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1996, 47, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, A.R.; Aramburo, C.M.; Cruz, R.A. Special educators’ knowledge of high-leverage practices: Construction of a pedagogical content knowledge measure. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, A.R.; Aramburo, C.M.; Cruz, R.A. Teacher Knowledge of High-Leverage Practices (TKHLP): Assessment Protocol and Soring Guide; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.; Loreman, T.; Forlin, C. Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2012, 12, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, V.L. A Comparative Study of K12 General Education and Special Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Levels towards Inclusion of Students with Special Needs. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/comparative-study-k12-general-education-special/docview/2029208460/se-2?accountid=11752 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Hosford, S.; O‘Sullivan, S. A climate for self-efficacy: The relationship between school climate and teacher efficacy for inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.S. The Impact of Instructional Coaching on Efficacy in General Education Teachers in Inclusion Classrooms. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3330 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Özokcu, O. The relationship between teacher attitude and self-efficacy for inclusive practices in Turkey. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 6–12. Available online: https://redfame.com/journal/index.php/jets/article/view/3034/3243 (accessed on 24 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, H.; Malinen, O.P.; Schwab, S. Teacher efficacy predicts teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, C.; Harwin, A. Shortage of special educators adds to classroom pressures. Educ. Week 2018, 38, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber, D.; Brown, N.; Marcuson, N.; Theobald, R. Challenges throughout the Second School Year during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Working Paper No. 10112022-1; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.cedr.us/working-papers (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Sayman, D.; Chiu, L.C.; Lusk, M. Critical incident reviews of alternatively certified special educators. In J. Natl. Assoc. Altern. Certif.; 2018; 13, p. 1. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1178666.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Sciuchetti, M.B.; Yssel, N. The development of preservice teachers’ self-efficacy for classroom and behavior management across multiple field experiences. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 44, 19–34. Available online: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol44/iss6/2 (accessed on 9 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Connelly, V.; Graham, S. Student teaching and teacher attrition in special education. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2009, 32, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/rev (accessed on 22 November 2022). [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).