Abstract

The universalization of schooling has triggered issues about the organization and management of more inclusive education systems. Several transnational organizations have produced guidelines that have contributed to the concept of inclusive education being incorporated into national educational policies. To identify the ideas underpinning this concept, we mobilized a policy cycle theoretical–methodological proposal. From a thematic analysis of (inter)national texts, four themes emerged: the recognition of diversity, the struggle for equity, the promotion of school autonomy and the emphasis on the participation of the educational community. In this article, we analyze the ideas underpinning the themes of struggle for equity and promotion of school autonomy to analyze the challenges and opportunities resulting from their articulation. Analysis of the Portuguese case revealed that the legal and normative framework shaped by international documents underlines a tension between these two themes, raising questions regarding the practices enacted by national and institutional actors. The findings suggest that equity is conditional on school autonomy; nevertheless, granted autonomy may not translate into improved equity. The extent to which our analysis of the Portuguese case reflects other national contexts where effective autonomy enhances equity remains to be seen.

1. Introduction

The right to education established in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) [1] has come a long way, to the point where its realization requires the organization of an education system that minimizes the risks of exclusion to the limit [2] and that aims at educational success for all [3]. By maintaining the same access routes to the curriculum for all pupils coming from social groups with different cultural capital, most of whom are distant from school cultural capital and, therefore, from powerful knowledge [4], school has established itself as a legitimized route for the conservation of social structures [5]. With the need for education systems to ensure learning opportunities for all, a predictor of more economically sustainable societies [6,7,8,9] and upward social mobility [10], various international organizations (e.g., the United Nations (UN), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank (WB)) prescribe lines of action through policy texts such as conventions, declarations, recommendations and reports [11] that are reflected at national and local policy levels [12]. These lines of action, on the one hand, disseminate the idea of nationally prescribed curricula and encourage standardized monitoring and evaluation [13,14,15]; on the other hand, they reaffirm the need for a curriculum adapted to the diversity of the school population and the characteristics of local contexts and principles of curricular justice (we mobilize the Santomé’s conception of curricular justice: “curriculum that is designed, put into action, evaluated and researched taking into account the degree to which everything that is decided and done in the classroom respects and meets the needs and urgencies of all social groups” [16] (p. 9)) and recognition [17,18] fundamental to the achievement of a more inclusive education. Hence, analysis of the Portuguese context brings forward the specificities of a national context where the struggle for equity and the promotion of school autonomy back up the idea of inclusive education. In line with this, in Portugal, several national texts (e.g., legal diplomas, recommendations and declarations), especially since the Jomtien Declaration [19], provide guidelines for both the autonomy of schools in the flexibilization of the curriculum and for standardized assessment by external mechanisms—a trend also observed in OECD member countries [20]. This trend reflects the idea that education policies derive from a process of globally established meaning making [21] and develop with influences from different interest groups and their networked governance [12,22].

To capture the ideas supporting inclusive education policies, this paper convenes the policy cycle approach proposed by Stephen Ball and colleagues [23,24]. This is a theoretical and methodological approach that assumes that the policy takes place in different contexts of interconnected action that represent arenas of political action dominated by specific interest groups [22]. In this approach, micropolitical processes and the role of actors involved in politics at the local level assume particular importance [22]. In a first phase, the policy cycle was composed of three contexts: the context of influence, the context of text production and the context of practice [23]; later, it was extended by considering the context of effects (outcomes) and the context of policy strategy [24], both of which can be analyzed within the context of practice [25] insofar as they refer to feedback from this context [22].

To identify the ideas that underpin the concept of inclusive education in the Portuguese context, we analyzed the contexts of influence and text production, are symbiotically linked [26]. The context of influence refers to the space in which certain ideas acquire legitimacy and are presented as solutions through international organizations [25], usually at conferences, where results of studies are disseminated and proposals for action are discussed. The context of textual production refers to texts that influence these debates in which different interest groups are present and that, therefore, represent different versions of policies, such as conventions, declarations, legal diplomas, opinions, recommendations, etc. Sharing the analytical framework of the policy cycle, for which policies are not fixed and immutable [27] but rather dynamic and flexible, Slee [28] argues that inclusive education has no determined starting point, with different ideas coexisting that have contributed to the formation of this field. In this line of thought and considering that educational policy presented in the form of text is an element that can be analyzed, interpreted and contextualized [29], we analyzed international and national texts that guide inclusive education policies in Portugal. We identified four themes: recognizing diversity, struggling for equity, promoting school autonomy and emphasizing the participation of the educational community. In this article, we analyze the themes of struggle for equity and promotion of school autonomy, in which we identify statist, democratic, neoliberal and standardized perspectives that are useful to analyze the challenges and opportunities resulting from their articulation with regard to the development of more inclusive education systems. Therefore, we set out the following research questions: What ideas support the themes of struggle for equity and promotion of school autonomy? What opportunities and challenges are identified in the coordination of these themes for the development of more inclusive education systems?

2. Materials and Methods

To answer these questions, we used international and national texts that the Directorate-General for Education (DGE) identifies on its website as guiding inclusive education policies. The documents selected by the DGE were assumed as those framing the legal and normative framework for inclusive education. This option is justified by the functions of this central state service, such as “ensuring the implementation of policies (...) for pre-school education, basic and secondary education and out-of-school education, providing technical support for their formulation and monitoring and evaluating their implementation” [30] (Article 12). Subsequently, we collected other texts that are referenced in these texts pointed out by the DGE and that we considered relevant to answer the questions posed. The documentary corpus (Table 1) consists of 20 international texts and 13 national texts published between 1948 (UDHR) and 2018 (Legal Framework for Inclusive Education in Portugal, in force until the present). The texts include conventions, declarations, recommendations and legal texts, which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Policy texts analyzed.

We started from the patterns of meaning found in the set of documents listed in Table 1 to identify ideas that converge to form the political process of inclusive education policies. For analysis of the texts, we used NVivo, a qualitative research software, to demarcate the ideas found from open codes, and we linked the ideas through axis coding [31,32]. We then followed the phases of the thematic analysis method defined by Braun and Clarke [33], which are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Phases of thematic analysis (adapted from Braun and Clarke [33]).

Braun and Clarke’s [33] proposed definition of the phases of the thematic analysis method was essential for organizing and identifying the data. The analysis was undertaken by the three authors of this study, believing that bias is mitigated when the same data are observed by more than one investigator [34]. This corresponds to ‘researcher triangulation’, one of the four types of triangulation defined by Denzin [34] that qualitative researchers should use to increase the objectivity, truthfulness and validity of social research. In the phases of researching, reviewing, defining and naming the themes, there was a need for several rereadings and to re-generate initial codes due to the identification of new meanings, and there was a back and forth of reflections between the authors on the data throughout the analysis. Although the themes were formed inductively based on the specificities of the data, when the relationships between the text extracts and each subtheme and, in turn, between the subthemes and the themes were verified in the review of the themes, it was necessary to improve both the naming and description of each theme, as well as some subthemes. This phase was accompanied by concept maps produced in the NVivo program based on the selection of statements that contributed to the identification of each theme, which allowed for a comprehensive perception of how ideas are linked, enabling new connections. The whole analytical process was characterized by moving back and forth between the influences that were discovered, which required a process of continuous thematic refinement to ensure that themes were related to each other but did not overlap in content. This involved a systematic review of all units of analysis to confirm that they collaborated in a pattern of meaning common to the dataset as a whole.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section we seek to answer the research questions previously posed by exploring (i) the influences underpinning the themes of struggling for equity and promoting autonomy and (ii) the opportunities and challenges identified in linking these themes for the development of more inclusive education systems.

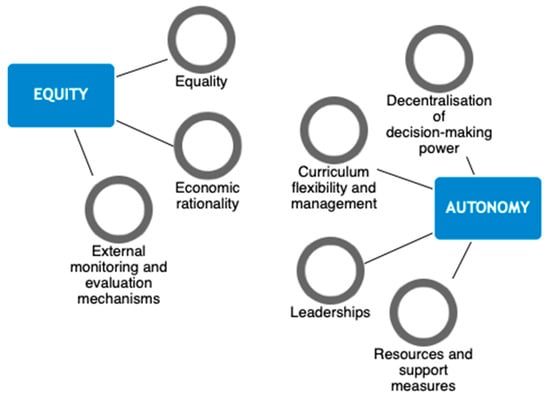

The thematic analysis emphasized the theme of struggling for equity, encompassing the subthemes of promoting equality, considering economic rationality and implementing mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation, as well as the theme of promoting autonomy, supported by the subthemes of decentralization of decision-making power in education systems, greater flexibility and management of the curriculum, access to adequate resources and internal leadership aligned with the principles of inclusive education. The relationship between the subthemes and themes is presented in the conceptual map in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of the struggle for equity and promotion of school autonomy themes and their respective subthemes.

3.1. The Struggle for Equity

The right to education, as enshrined in Article 26 of the UDHR [1], has since been reaffirmed and expanded by various international organizations (e.g., UNESCO; WB; OECD), orienting its realization either towards the promotion of equal opportunities for a just and egalitarian society or towards a neoliberal rationality in which measurement and comparisons have become a central mode of global and national governance towards an equitable society [35,36,37]. Equity continues to be defined on the basis of notions of equal opportunities [38] but does not respond exclusively to an imperative of social justice and democracy. It is also about “using resources more effectively and increasing the supply of skills that fuel economic growth” [39] (p. 1). The thematic analysis allowed us to identify three subthemes that are presented as the backdrop of the struggle for equity theme: (i) equality, (ii) economic rationality, (iii) and monitoring and evaluation.

In Table 3, we present the description of each subtheme and some statements that allowed it to be identified, showing its relationship with the struggle for equity.

Table 3.

Statements that emphasize the struggle for equity theme.

The statements supporting the subtheme of equality reiterate that education should be accessible to all individuals in equal measure, without discrimination. In this vein, the need to address inequalities related to access to education, participation and learning outcomes is emphasized, which implies ensuring that all social groups, especially those at risk of social and school exclusion, have adequate opportunities that guarantee them a quality education. In sum, promoting equality is about ensuring that personal and social circumstances are not an obstacle to realizing educational potential and ensuring a basic level of education for all [59].

Another subtheme related to the struggle for equity is economic rationality. Organizations such as the UN, WB and WHO suggest that education is a key dimension of social, cultural and economic projects, meaning that investing in quality education for all is beneficial not only for the personal development of learners but also for society as a whole. The WB [52] and the OECD [53] justify investing in education on the basis of the impact it has on poverty reduction. UNESCO [49], the WB [52] and the ANDEE [54] point out that it is more efficient to use the same resources to school all students together rather than setting up a complex system of different types of schools specializing in different groups of students, evidencing the cost-effectiveness of the education system. We believe that this perspective of using the same resources for all can legitimize the prioritization of efficiency over quality, i.e., not investing in the most appropriate resources to achieve inclusive education, affecting the most vulnerable groups and widening inequalities.

Orientation for education systems to develop monitoring and evaluation mechanisms is another aspect pointed out to ensure equity. The Maastricht Treaty, for example, encourages the exchange of information and experience on issues common to Member States’ education systems to identify challenges and share good practice. UNESCO [19] even assigns the state a primary role in regulating standards, improving quality and reducing disparities between regions, communities and schools. At the national level [44,46,58], the need for centralized monitoring and evaluation actions is corroborated to ensure educational equity in terms of both access to education and educational outcomes. In these international and national discourses, monitoring and evaluation processes are presented as essential to identify inequalities and adjust educational policies and practices; however, we consider that when framed within a standardized approach, they may not consider the singularities of the contexts, which may hinder the achievement of equal opportunities. In line with this analysis, we invoke Field, Kuczera and Pont [59] and Fullan [60], who point out that achieving equity in education requires a holistic approach involving both public policy measures and decentralized actions within schools and communities. This promotes inclusion and responds to the specific needs of each educational context, which brings us to the next theme: the promotion of school autonomy.

3.2. The Promotion of School Autonomy

Promoting school autonomy has been identified as an essential element for improving education systems [3,17]. In Table 4, we point out some statements that allowed us to identify the subthemes that are grouped in this theme: (i) processes of decentralization of the decision-making power of educational systems, (ii) making the curriculum more flexible and managing it locally, (iii) promoting internal leadership and (iv) making resources and support measures available and profitable. Table 4 presents a description of each subtheme and some statements that allowed it to be identified, showing its relationship with the promotion of school autonomy.

Table 4.

Statements that emphasize the theme of promotion of school autonomy.

The subtheme concerning the transfer of decision-making powers and responsibilities from centralized spheres to schools promotes more inclusive education in the sense that it allows for more immediate adaptation to the needs of contexts and is supported in several international documents. UNESCO [49] proposes establishing decentralized mechanisms for planning, supervision and assessment of children and adults with special educational needs. The CEC [56] positively highlights the efforts undertaken by several Member States, notably Portugal, to improve the efficiency of education systems through decentralization by granting greater autonomy to schools in defining content, allocating budgets and making decisions related to human resource management. In 2014, the OECD [61] emphasized the importance of further expanding school autonomy. The listed national texts also highlight that decentralization processes are key to adapting to local realities. For example, in the Basic Law (1986), it is pointed out that schools need greater autonomy to make decisions that are aligned with the specific needs of the community in which they are inserted. This change in educational administration is affirmed by DL 43/89, which provides greater autonomy to determine curriculum content, allocate financial resources and make decisions regarding teaching and administrative staff. The reorganization of educational structures mentioned in Order 147-B/ME/96 and DL 115-A/98 requires a reconceptualization of the school in the sense of open organization of communities, recognizing them as territorial units essential in the democratization of education. The conclusion of autonomy contracts between schools and the Ministry of Education, as recommended by the CNE [63], extends the responsibility of schools for educational processes and results, which indicates that schools will take on a greater role in defining educational goals and strategies, adapting them to their specific realities. DL 54/2018 also contributes to the idea of decentralization by encouraging schools to develop partnerships with each other, with municipalities and with other institutions in the community, aiming to enhance local resources and promote the coordination of educational responses.

The statements also reveal a clear consensus on the condition of curricular flexibility and management for the production of more inclusive education systems. According to Cosme [3], the possibility of adapting and diversifying curricula allows schools to develop locally relevant content and projects, addressing the specific needs of learners and contexts. This perspective is widely supported in international texts [47,49,64,65,66] that highlight the need to offer flexible learning pathways and recognize acquired competences, i.e., validate and certify learning, extending Young’s [4] powerful knowledge. National legal statutes, such as Order 5908/2017 and DL 55/2018, announce a contextualized adaptation of the curriculum, recognizing that full autonomy is only guaranteed when the object of that autonomy is the curriculum. In short, the idea of curricular flexibility is identified as a central axis for school autonomy, allowing schools to adapt to the needs of students and contexts and enabling a more inclusive education.

Strengthening internal leadership (top and middle) also stands out as a subtheme of promoting school autonomy. UNESCO [4] emphasizes the role of school principals in promoting participation, collaboration and positive attitudes throughout the educational community. According to the literature [71,72,73,74], there is a correlation between leadership and inclusion, with leadership exerting a close influence on the way in which the participation of educational communities develops. This is intended to exemplify how a subtheme (in this case, leadership) collaborates to consolidate several themes (in this case, in addition to autonomy, participation). In the national context, since 2008 (DL 75/2008), the Ministry of Education has concentrated the management of schools in a unipersonal body—the principal—with the justification that the measure aims to improve the effectiveness of the implementation of educational policy measures and that it is therefore necessary to strengthen leadership. Nevertheless, the same legal diploma reinforces the participation of members of the local community and families in school management bodies. In 2012, the CNE [63] recommended greater power for middle management in school decision making—a perspective that seems to be corroborated by DL 54/2018 with the creation of multidisciplinary support teams for inclusive education (DL 54/2018), although the appointment of their members falls to the principal. The DGE [68] recognizes that the success of inclusive education policies depends precisely on leadership guided by the principles of inclusive education. In this context, it is important to understand how the internal leadership, especially the principal (one-person body), conceptualizes inclusive education and whether the practices they describe as inclusive are actually inclusive, i.e., whether they aim to promote equal learning opportunities for all students.

Access to resources and support measures is also a key aspect of promoting school autonomy. Schuelka et al. [75] state that one of the biggest obstacles to inclusive education is precisely the lack of resources: both inadequate school facilities and a lack of specialized school professionals. UNESCO stresses the need for a substantial increase in resources [19], as well as greater autonomy for schools in organizing available resources [49] in order to better meet the individual needs of learners. The WHO and WB [51] point to the need for specialized professionals in schools, such as therapists and psychologists; this is corroborated by the UN [69], which also draws attention to the need to improve school infrastructure. The CEU [70] warns that for flexible learning pathways to be successful, more support needs to be provided to all professionals working in schools. At the national level, the need for increased resources has also been recognized [43,63]. Nevertheless, DL 54/2018 provides guidelines so that measures to support learning and inclusion are operationalized with the resources available in the school according to a cost-effective logic. Although this legal text admits the allocation of additional resources—exceptionally for students whose curriculum is developed with significant curricular adaptations—this is required to be requested and substantiated by the principal to the competent service of the Ministry of Education, which, according to our interpretation, is an indicator of a centralized educational system.

Emerging from our analysis of the relationship between these two themes—struggle for equity and promotion of school autonomy—is the paradox of meanings with respect to standardized assessment processes defined at the macro level, i.e., an executive idea, and the flexibility of the curriculum according to the singularities of the students according to a more humanistic and democratic logic. This is in line with what Ball [12] (p. 122) defines as the “tension that runs through all varieties and analyses of policy, between, on the one hand, the need to attend to the local particularities of the policy-making and implementation process and, on the other, the need to take account of general patterns and apparent convergences between localities or what they have in common”. Thus, we consider that external evaluation processes, with the aim of promoting equity, may end up contributing to the standardization of educational processes and to the legitimization of a single route to achieve powerful knowledge [4] and thus “(...) lead to schools looking more and more like each other rather than becoming more diversified” [76] (p. 259).

This paper underlines how policy documents are shaping the legal and normative framework of inclusive education policies and convenes the Portuguese case to illustrate the tension between equity and autonomy. The research findings address two important issues in inclusive education and provide a sense of context for their interpretation. Focusing on the Portuguese context, external evaluation carried out through final cycle tests (ninth grade) and national exams (in scientific–humanistic secondary education courses), which are the same for all students, with no adaptation of curricular content, expresses a centralized educational system and can therefore be evaluated by parameters determined at the national level. With the exception of school situations where the curriculum is developed through the educational measure of significant curricular adaptations [47] (Article 10, point b), external assessment to complete these levels of education is mandatory for all students, regardless of the flexibilization of the curriculum that may have occurred throughout their school career under the universal [47] (Article 8), selective [47] (Article 9) and additional [47] (Article 10, except for point b) measures.

Therefore, the universality of external assessment seems to contradict the idea that “the main curricular and pedagogical decisions” can be “taken by schools and teachers”, as DL 55/2018 advocates [48] (Preamble). Teachers are understood as curriculum decision makers, and schools are understood to be responsible for adapting the prescribed curriculum to the real situations they face [77]. Nevertheless, in the same legal text, “curricular autonomy and flexibility” is defined as the “faculty conferred on the school to manage the curriculum of basic and secondary education, grounded on the basic curricular matrices, based on the possibility of enriching the curriculum with the knowledge, skills and attitudes that contribute to achieving the competences provided for in the Profile of Students Leaving Compulsory Education” [48] (Article 3, paragraph c). However, this idea of “managing the curriculum” based on “basic curricular matrices” to “achieve the competences provided” at the national level-in the Profile of Students Leaving Compulsory Schooling, defined as a “benchmark for decisions to be adopted by educational decision-makers and actors at the level of education and teaching establishments and the bodies responsible for educational policies” [78]-is far from the idea of deciding on the curriculum that we mentioned earlier. In this vein, in Lima’s [79] analysis of the policy of autonomy and curricular flexibility embodied in DL 55/2018, he argues that the curriculum can indeed be locally managed and “enriched” but continues to be “heteronomously decided” [79] (p. 183).

4. Conclusions

The thematic analysis revealed the presence of a number of influential international organizations in the formulation of inclusive education policies in Portugal. The UN, UNESCO, the WB, the OECD, the WHO and the EU, through conventions, declarations, recommendations, reports and studies, provide guidelines that are identified in national legislation and recommendations, and there is coordination between the international and national levels of inclusive education policymaking. The ideas that underpin each theme influence the development of other themes. For example, the idea of promoting equal opportunities, which is part of the theme of struggle for equity, is closely linked to the idea of decentralization of decision-making power and the ability of schools to adapt their practices to the needs of students and contexts, while the idea of curriculum flexibility, which is part of school autonomy policies, promotes equity by creating conditions for schools to offer adapted and relevant learning pathways for all students.

We also identified weaknesses in the relationship between these ideas that may pose challenges for the democratization of education. For example, the struggle for equity, when underpinned by a logic of economic rationality and standardization, may lead to an overemphasis on comparison and measurement of educational outcomes, disregarding the specificities and diversities of learners and contexts. Therefore, it is desirable for research to analyze the theme of recognition of diversity and to reflect on the challenges and opportunities that derive from combining it with the themes of the struggle for equity and promoting school autonomy.

However, we note some limitations of the research: the thematic analysis presented here was limited to the texts indicated on the DGE website as guiding inclusive education policies, so it would be desirable to expand the scope of the research with other texts named by schools; in addition, the documentary corpus consists of texts published until 2018, suggesting the need for analysis of texts published later. Thus, we recommend that future research update and complement the results presented here, considering that the context of the influence of educational policies is constantly changing.

The promotion of school autonomy may face limitations because it is dependent on both the resources of the territory in which the school is located and the involvement of other local institutions in the development of inclusive education. This means that policies are not finalized at the moment of publication of the legislative text [25] but continue to be elaborated in the context of practice. According to this view, the concepts of given autonomy and effective autonomy are especially important because equity relies on how autonomy is enacted by policymakers, teachers, school leadership, students and the educational community.

This justifies the study of what schools understand as “inclusive education”, how they interpret the texts influencing these policies and how they translate them, agreeing that the enactment of policies depends on “the context of application and its actors” [80] (p. 16), i.e., the context of the practices of the policy cycle. In this vein, Shiroma, Campos and Garcia [81] (p. 431) state that “policy texts give rise to interpretations and reinterpretations, generating, as a consequence, attributions of different meanings and senses in the same term”, that is, the interpretation of the texts defines the practices and therefore also produces the policy, making local actors authors of the policy. Accordingly, it is worth asking how institutional actors (principals and teachers) translate the guidelines of policy texts into more inclusive educational responses for all students.

Therefore, we consider that the main contribution of this article is the comprehensive analysis of the ideas that underpin the themes of the struggle for equity and the promotion of school autonomy at the international and national levels. Analysis of the Portuguese case revealed that the legal and normative framework shaped by international documents underlines a tension between equity and granted and/or effective autonomy, raising questions regarding the practices enacted by national and institutional actors; for instance: the orientation for major curriculum decisions to be made by schools and teachers (DL 55/2018) while the education system continues to co-operate towards a curriculum that is centrally decided and assessed; the guidelines to prioritize the use of the same resources for all students can lead to efficiency, posing the challenge of finding a balance between cost-effectiveness and the mobilization of adequate resources; and external monitoring and evaluation mechanisms enacted by following a standardized approach, which can disregard specificities of the contexts that influence educational experiences and outcomes and, as a result, perpetuate disparities in terms of school success. At the same time, the orientation towards making the core curriculum more flexible through measures to support learning and inclusion is an opportunity to design more inclusive school pathways (than before), and this contributes to recognizing the importance of local autonomy in achieving more inclusive education. The creation of multidisciplinary teams to support inclusive education allows schools to take a plural approach of perspectives and knowledge in planning and implementing the most appropriate practices for each school situation, which seems to be an opportunity to affirm the importance of middle-management leadership in developing more inclusive education. The guidelines for establishing partnerships with local institutions and actors can lead to the coordination of educational responses that help to respond to school situations for which the education system does not yet provide the most appropriate responses, contributing to social cohesion. However, as we have already mentioned, this dependence on the resources of the territory and relations with the territory can also represent a limitation. By pointing out the challenges and opportunities that emerge from the articulation of these themes, this paper informs the process of decision making by teachers, educators, researchers and other actors who collaborate in the development of inclusive education policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V.; methodology, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V.; formal analysis, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V.; investigation, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.C.; writing—review and editing, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V.; supervision, A.C. and A.V.; funding acquisition, A.E.C., A.C. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology IP (FCT) and the European Social Fund [PhD scholarship no. 2020.05522.BD]. It was also supported by FCT under multi-annual funding awarded to CIIE [grants no. UIDB/00167/2020 and UIDP/00167/2020].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations [UN]. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Morgado, J.C. Inclusive education in today’s schools: A contribution to reflection. In Proceedings of the X Galician-Portuguese International Congress of Psychopedagogy; University of Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2009; pp. 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cosme, A. Autonomia e Flexibilidade Curricular. Propostas e Estratégias de Ação; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Conhecimento e Currículo. Do Socioconstrutivismo ao Realismo Social na Sociologia da Educação; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. A Reprodução: Elementos para uma Teoria do Sistema de Ensino, 7th ed.; Petrópolis, R.J., Ed.; Editora Vozes: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. Education Policy Analysis: Overview; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. What is equity in education? In Education at a Glance 2012: Highlights; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank [WB]. What Matters Most for Equity and Inclusion in Education Systems: A Framework Paper. SABER. 2016. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/621711500379564153/pdf/SABER-what-matters-most-for-equity-and-inclusion-in-education-systems-a-framework-paper.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Council of the European Union [CEU]. Recomendação do Conselho, de 22 de maio de 2018, Relativa à Promoção de Valores Comuns, da Educação Inclusiva e da Dimensão Europeia do Ensino. (2018/C 195/01). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0607(01)&from=EN (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- World Bank [WB]. The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/state-of-global-learning-poverty (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Ball, S.J. Politics and Policy Making in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.J. Diretrizes políticas globais e relações políticas locais em educação. Currículo Front. 2001, 1, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Marinho, P.; Leite, C.; Fernandes, P. O Papel dos Órgãos de Gestão da Escola na Avaliação da Aprendizagem: Entre a burocracia e a melhoria. Meta Avaliação 2019, 11, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadfoot, P.; Black, P. Redefining assessment? The first ten years of assessment in education. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2004, 11, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobart, G. Testing Times: The Uses and Abuses of Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santomé, J.T. Currículo Escolar e Justiça Social: O CAVALO DE TROIA DA EDUCAÇÃO; Penso: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M.; Beane, J. Escolas Democráticas; Editora Cortez: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, M.; Leite, C. Mapping social justice perspectives and their relationship with curricular and schools’ evaluation practices: Looking at scientific publications. Educ. Chang. 2018, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs; UNESCO: Jomtien, Thailand, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, E.; Morgado, J. Currículo e avaliação: Os testes estandardizados. Rev. Bras. Política E Adm. Educ. 2016, 32, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P. Standards Deviation: How Schools Misunderstand Education Policy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, A. Bologna 2010. The Moment of Truth? Eur. J. Educ. 2012, 47, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, R.; Ball, S.J.; Gold, A. Reforming Education & Changing Schools: Case Studies in Policy Sociology; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. Educational Reform: A Critical and Post-Structural Approach; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardes, J. Abordagem do ciclo de políticas: Uma contribuição para a análise de políticas educacionais. Educ. Soc. 2006, 27, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J.; Bowe, R. Subject departments and the “implementation” of National Curriculum policy: An overview of the issues. J. Curric. Stud. 1992, 24, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J.; Mainardes, J. Políticas Educacionais: Questões e Dilemas; Cortez: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Slee, R. La Escuela Extraordinaria: Exclusión, Escolarización y Educación Inclusiva; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozga, J. Investigação Sobre Políticas Educacionais: Terreno de Contestação. Coleção Currículo, Políticas e Práticas; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Decrew-Law 266-G/2012, de 31 de Dezembro. Diário da República n.º 252/2012, 3º Suplemento, Série I de 2012-12-31. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2012/12/25202/0024300245.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Zamawe, C. The implication of using NVivo software in qualitative data analysis: Evidence-based reflections. Malawi Med. J. 2015, 27, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsop, D.; Chelladurai, J.; Kimball, E.; Marks, L.; Hendricks, J. Qualitative Methods with Nvivo Software: A Practical Guide for Analyzing Qualitative Data. Psych 2022, 4, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nóvoa, A.; Yariv-Mashal, T. Comparative Research in Education: A mode of governance or historical Journey? Comp. Educ. Rev. 2003, 39, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.D.; Benavot, A. PISA, Power, and Policy: The Emergence of Global Educational Governance; Symposium Books: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.J. Foucault, Power and Education; Routledge: New York, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, B.; Sellar, S.; Savage, G.C. Re-articulating social justice as equity in schooling policy: The effects of testing and data infrastructures. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 35, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. Why equity in education is so elusive. In World Class: How to Build a 21st Century School System; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All. Meeting Our Collective Commitments. World Forum on Education; UNESCO: Dakar, Senegal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law n.º 46/86. Diário da República n.º 237/1986, Série I de 1986-10-14. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/46-1986-222418 (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Order 147-B/ME/96, de 1 de Agosto. Diário da República nº 177, 2.ª Série de 1986-08-01. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/147-b-1996-1863460 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Decrew-Law 115-A/98, de 4 de Maio. Diário da República n.º 102/1998, 1º Suplemento, Série I-A de 1998-05-04. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/1998/05/102a01/00020015.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Decrew-Law 75/2008, de 22 de Abril. Diário da República n.º 79/2008, Série I de 2008-04-22. Available online: https://dre.tretas.org/dre/233009/decreto-lei-75-2008-de-22-de-abril (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Conselho Nacional de Educação [CNE]. Recomendação nº 1/2014. Diário da República, II série—Nº 118—23 de junho de 2014. Available online: https://www.cnedu.pt/content/deliberacoes/recomendacoes/Recomendacao_DR_1.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Decrew-Law n.º 54/2018. Diário da República n.º 129/2018, Série I de 2018-07-06. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/54-2018-115652961 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Decrew-Law n.º 55/2018. Diário da República n.º 129/2018, Série I de 2018-07-06. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/55-2018-115652962 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; UNESCO: Salamanca, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission [EC]. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Disability Strategy 2010–2020: A Renewed Commitment to a Barrier-Free Europe. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM%3A2010%3A0636%3AFIN%3Aen%3APDF (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO); World Bank (WB). World Report on Disability 2011; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575 (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- World Bank [WB]. Learning for All: Investing in People’s Knowledge and Skills to Promote Development. World Bank Group Education Strategy 2020. 2011. Available online: https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/418511491235420712/Education-Strategy-4-12-2011.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Special Education Teachers [ANDEE]. The Lisbon Educational Equity Statement. 2015. Available online: http://isec2015lisbon.weebly.com/the-lisbon-educational-equity-statement.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Maastricht Treaty. 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:1992:191:FULL&from=NL (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Commission of the European Communities [CEC]. Communication from the Commission to the Council and to the European Parliament. Efficiency and Equity in European Education and Training Systems; Commission of the European Communities [CEC]: Brussels, Belgium; Luxembourg, 2006; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2006:0481:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. Incheon Declaration: Education 2030 towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning for All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Order 9726/2018, de 17 de Outubro. Diário da República n.º 200/2018, Série II de 2018-10-17. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/9726-2018-116696215 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Field, S.; Kuczera, M.; Pont, B. Education and Training Policy. No More Failures: Ten Steps to Equity in Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. The Principal: Three Keys to Maximizing Impact; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Education Policy Outlook; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/EDUCATION%20POLICY%20OUTLOOK_PORTUGAL_EN.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Decrew-Law n.º 43/89. Diário da República n.º 29, Série I de 1989-02-03. Available online: https://dre.tretas.org/dre/22784/decreto-lei-43-89-de-3-de-fevereiro (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Conselho Nacional de Educação [CNE]. Estado da Educação 2012. Autonomia e Descentralização. 2012. Available online: https://www.cnedu.pt/content/edicoes/estado_da_educacao/EE_2012_Web3.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- United Nations [UN]. Standard on Equal Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. Education at a Glance. OECD Indicators 2006; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. Education for the Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives (ESDs); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Order n.º 5908/2017. Diário da República n.º 128/2017, Série II de 2017-07-05. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/5908-2017-107636120 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Direção-Geral da Educação [DGE]. Para uma Educação Inclusiva: Manual de Apoio à Prática; Ministério da Educação/Direção-Geral da Educação: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations [UN]. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Council of the European Union [CEU]. Conclusions of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, Meeting within the Council, on Inclusion in Diversity to Achieve a High Quality Education For All. (2017/C 62/02). 2017. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017XG0225(02) (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Gronn, P. Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 13, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J.B. Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrós, M.; Flecha, R. Towards a Conceptualization of Dialogic Leadership. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 2, 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, C.; Almeida, A.P.; Ferreira, M. Headteachers and Inclusion: Setting the Tone for an Inclusive School. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuelka, M.J.; Sherab, K.; Nidup, T.Y. Gross National Happiness, British Values, and non-cognitive skills: The role and perspective of teachers in Bhutan and England. Educ. Rev. 2018, 71, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B. The lessons of international education reform. J. Educ. Policy 1997, 12, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.; Fernandes, P. Challenges for teachers in the construction of educational and curricular changes: What possibilities and what constraints? Rev. Educ. 2010, 33, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Order nº 6478/2017. Diário da República, 2.a série—Nº 143—26 de julho de 2017. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/2s/2017/07/143000000/1548415484.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Lima, L.C. Curriculum autonomy and flexibility: When schools are challenged by the government. Rev. Port. Investig. Educ. 2020, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.C.; Fradique, J. Guia da Autonomia e Flexibilidade Curricular; Raiz Editora: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shiroma, E.O.; Campos, R.F.; Garcia, R.M.C. Decifrar textos para compreender a política: Subsídios teórico-metodológicos para análise de documentos. Perspectiva 2005, 23, 427–446. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).