Abstract

This paper airs the experiences of eighteen students with special educational needs completing their studies at a Finnish vocational institution, which has a mandate to provide intensive special support for the students. It contributes to the national and international discussion of education’s purposes and elaborates on students’ descriptions. The study frames a research question: To what extent are Biesta’s domains of good education—qualification, socialization, and subjectification—audible in the narratives of Finland’s VET special educational needs students? The paper adopts a narrative approach and uses narrative positioning analysis as a methodical tool to drill down into the themes produced in deductive content analysis. According to our analysis, subjectification and socialization were the most important domains of VET. The qualification domain of education did not appear as professional self-confidence in students’ narratives, but it served as subjectification and socialization. VET must be an inclusive process that provides all students with the opportunity to become balanced and civilized citizens and assist them in entering the world. To this end, instead of emphasizing measurable outcomes such as qualifications and employment rates, more attention should be paid on the social and subjective domains of VET.

1. Introduction

This paper brings into the spotlight the students graduating from the Finnish Vocational Education and Training (VET) system after providing them with intensive special support. It also reports on their experiences of the education they received. It is relevant to consider the process of VET from the students’ perspective because young people with special educational needs often face difficulties when stepping into the primary labor market and continuing education and training [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, according to Billet [5], it is necessary to understand students’ needs and aspirations and to engage their energy as learners, to moderate unrealistic expectations, but also to assist them to mediate learning experiences in vocational education effectively.

Thus, it is worth considering to what extent schools, who are experiencing tougher and more consequential accountability structures purporting to improve teaching and learning, have a genuine interest in how students with special educational needs feel about schooling [6,7]. In addition, do efforts that have focused on measurements and quality assurance improve educational policy and practice equally [8,9,10,11]? That is, does anyone know what makes education good, rather than what makes it merely effective or efficient [10,12].

Many recent studies on Finnish vocational education have focused either on vocational competence and on work-life skills or on pedagogy and teaching methods [13]. Internationally the topics of the doctoral thesis have addressed a range of issues from policy to institutional change to the lived experience of vocational education [14]. However, little attention has been paid to students’ experiences [15] and even less to those who need intensive special support for their studying [4,16,17]. This study was designed to improve our understanding of Finnish VET, providing intensive special support by interviewing eighteen students who were graduating and proceeding to the next stage in their lives (Appendix A). We discussed with them their experiences of VET studying and their expectations and prospects for the future. Our research goal was to provide a more nuanced understanding of VET’s multiple purposes. By analyzing the students’ narratives, we sought an answer to our research question inspired by Biesta [8,9]:

To what extent are Biesta’s domains for a good education—qualification, socialization and subjectification—audible in the narratives of Finland’s VET special educational needs students?

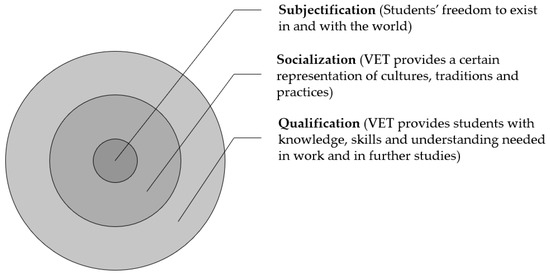

The qualification domain of VET provides students with knowledge, skills and understanding needed in work and in further studies. In Finland, VET has an explicit connection to work, which makes the socialization domain of education specific. VET provides a certain representation of cultures, traditions, and practices, which is its socialization function. The third domain of education is, according to Biesta [8,9], subjectification, which is the most essential for the study. Subjectification is about students’ freedom to exist in and with the world. This study contributes to the discussions about what constitutes good VET and proposes that in order to answer this question, we should acknowledge these three domains of education. We argue that students’ reactions to and perceptions of their educational experiences can provide teachers, policymakers, and employers with valuable insights, as well into teaching and guidance practices, as into the governance, and thus offer opportunities for more attractive VET.

2. Finland’s VET System

Students, teachers, schools, and even entire education systems are currently working under the pressure to “perform”, and the excellence of education is often defined by the measurements of outcomes [8]. In Finland, the education system has remained mainly public, but neo-liberal reasoning is re-shaping ideas about what the desired aims and goals of education are [18,19]. Laukia and Karjalainen [20] assert that this has also had an influence on the implementation of vocational education and training (VET) in Finland. The reform of Finnish VET started at the beginning of 2018 and it harmonized the education provision and placed emphasis on customers and competence [21,22]. This means that students in the VET system are seen as clients, consumers and entrepreneurs of the self [23,24]. The premise of Finnish VET is to respond to the individual skill needs of a broad range of students while considering the needs of the labor market and individual learners [25].

Intensive special support is defined in the Finnish Act on VET 531/2017, 65§ [26]. Students in vocational education and training are entitled to intensive special support if they have severe learning difficulties, serious disabilities, or illnesses, which means they require a customized, broad-based, and diverse form of special needs support. The means to meet the needs of students include the development of individual learning paths, individual pedagogical solutions and special teaching and learning arrangements. Thus, the Act on VET [26] creates a harmonized framework for equal provision of education for all students [25]. In Finland, intensive special support is provided for students in six vocational institutions, which have a mandate for this. Additionally, six vocational institutes have a restricted mandate to provide intensive special support for students. Whilst the number of Finnish vocational students who need intensive special support with their studies is relatively small, at just over one percent [27], it is morally and ethically right for their voices to be listened to and heard by all practitioners and stakeholders interested in what constitutes good VET education in Finland and internationally. Access to VET for all refers not only to education as a good that is free for everyone but also to the opportunity to take advantage of it and to experience personal benefits; that is, acquisition of knowledge of high quality and belonging to a social community [28].

3. VET as an Inclusive Initiation into and Preparation for the Practice of Work

In this study, we considered inclusion as a process wherein all VET students should have an opportunity to enter the education, workforce, and wider society with a sense of ownership of their future. This view elaborates on the perspective that important features of human life are rooted in human activity, not the activity of individuals or system principles central to the phenomena but in practices, in organized activities of multiple people [29]. However, implementation of inclusion in education is currently often understood as mechanisms of the school system, namely as special education and general education practices. We agree with Paju [30] that enhancing collaboration between teaching staff could lead to inclusive practice-related solutions in schools. In addition, we suggest that inclusive practices in work are also created together, in organized activities of multiple people.

The European pillar of social rights [31] defines that everyone has the right to quality and inclusive education, training, and life-long learning in order to maintain and acquire skills that enable them to participate fully in society and manage successful transitions in the labor market. However, according to earlier studies [32,33,34], the labor process, waged labor and its intensification are allied to effective expulsion and marginalization of particular groups of workers from employment. Therefore, it is important to spotlight the experiences of students representing the minority of all vocational students in Finland.

In this study, we based our reflections on Biesta’s view [8,9] of education’s domains and argued that it should be considered as a composite question that should specify its views about qualification, socialization, and subjectification. Biesta [9] proposes that domains of education could be represented as concentric circles with subjectification either as the inner or outer of the circles. In the study, we have positioned subjectification at the center because subjects, students and their experiences compose the core of our research (see Figure 1). However, this does not mean that we disregard vocational qualification, knowledge, skills, and traditions, but we believe that in the domain of education, we are always connected to the practices that are pursued and transformed together with the students [9,29,35,36]. Hence, to understand the world, to construct new ways of doing things, to connect people in new social and political orders necessitates the transformation of practices that exist in intersubjective spaces in society [29,35,36]. Without a strong connection to the subject and subjectification, vocational qualification becomes training which is something we do to others, not with them [9] (p. 102).

Figure 1.

Domains of education paraphrasing [9].

Education reflects either explicitly or implicitly the world and what is considered to be of value, which is the socialization domain of education [8,9]. Finnish vocational education has an explicit connection to work, which makes the socialization domain of education specific. First, training agreements and competence-based approach provide students with opportunities for individual study paths to gain missing skills and knowledge in order to fulfill the work-life needs and to be employed. Secondly, education provides a certain representation of cultures, traditions and practices, which is its socialization function. Students in vocational education are introduced to the work-life’s ground rules, operations models, and expectations and vice versa; employers get acquainted with the future employees and have an opportunity to have an impact on the organization of VET. Eventually, we propose that qualification requirements constitute the frame for Finnish vocational education. Education is implemented through the practical realization of the curriculum through its local variations and individual teachers’ interpretations and emphases.

In this study, we consider upper secondary vocational education to be a period of initiation and preparation during which students learn new orders of the labor market and construct the ideal subjectivity of a worker citizen, which is a social construction that closely connects the economic and social bond created by work [37]. As they study, students internalize the ethos of entrepreneurship and lifelong learning and can accept changes to follow the needs of the labor market [38,39]. Turner [40] claims that citizenship is both an inclusionary process involving some re-allocation of resources and an exclusionary process of building identities based on common or imagined solidarity.

4. Special Needs Students at the Center of the Study

Until now, there has been little discussion about the experiences of the students and even less of those receiving intensive special support during their vocational studying [41]. Earlier studies in Finland have discussed how the reformed VET system prepares young people, how do the young people themselves experience their studying and moving into the workforce and how important paid employment is for them [42,43,44,45]. Bartram and Cavanagh [46] and Cavanagh et al. [1] explored if Australian VET programs are delivering education that enables secure employment and promotes opportunities for individuals with disabilities. Earlier studies have also indicated that schools are mostly helping their students in their academic achievement and not in developing competencies to manage their own careers [42,43,47,48]. Furthermore, previous research has tended to focus on the VET teachers’ position in VET and correspondingly on pedagogical practices [49,50,51,52,53].

This paper presents how special needs students’ experiences echo Biesta’s [8,9] domains of education. In line with Wheelahan and Moodie [54], we suggest that variations in vocational education’s role in preparing graduates for employment and educational pathways lie not in the nature of vocational education nor its qualifications but in the structure of the labor market and the ways employers use qualifications to select graduates to enter and progress in employment. Effective workplace education and training would be critical to support workers with special needs at work [1,55]. This could contribute to bridging the gap that often marginalizes certain groups. People with disabilities also have the right to income support that ensures living in dignity, services that enable them to participate in the labor market and in society and a work environment adapted to their needs [31]. These are examples of practices that might provide individual support to those with special needs at work. Above all, we need to change the practices of all those involved in the project of work to make it more socially just. This requires the assent and commitment of all involved if we are to create an intersubjective agreement about how to understand the world, mutual understanding of others’ positions and perspectives and an unforced consensus about what to do to change it [29,36]. This would call for new semantic spaces and ways to understand one another and the world, to find new ways to use resources and to establish new and more solitary ways that people can live and work together and relate to one another [36].

5. Ethics of Researching with Students Who Have Special Educational Needs

When examining students who represent the marginalized group of students in VET, the questions of the wider implications of the research are relevant. The study followed the guidelines of the Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics [56]. This ethical commitment of the study contains not only the research practice but also what kind of understanding the study promotes and produces of these students and of vocational special schools [57]. Though the participants of this study needed support in their studying, they did not need support in research interviews, but they participated and voiced their experiences independently. Anyhow, the concept of informed consent was approached holistically, which means that voluntary participation and anonymity were repeatedly discussed with the participants [57].

Although opportunities and the position of special needs students in education have improved, their occupation within society seems still fragile and their socio-economic situation weaker than other populations [58,59]. This article contributes to this discussion by promoting and embracing students’ voice, and by increasing the understanding of their experiences and needs. The research is designed for the students, not on students.

6. Methodology

We consider that the underlying value of qualitative educational research is to make schools more equitable and to ensure greater equality of opportunity and outcome [60]. This was fundamental for the study because the research was conducted with students who represent a marginal and often stigmatized group of students and who use their voice in adaptable ways [42,43]. With this premise, the narrative approach became applicable in the study. We argue with Bruner [61] that narratives are the form to organize experiences and our memory of human happenings—stories, excuses, descriptions. Interviewing was central to this research as we wanted to listen and understand the students’ experiences. Interviews created an opportunity to pause and reflect with participants about what they remembered, valued, liked, and disliked about their vocational studying [62]. We opted for semi-structured interviews so that the participants would be able to feel themselves free to express themselves in their own words. The first author conducted the interviews, which unfolded like comfortable conversations of students’ experiences and opinions. Interviews consisted of ten open questions and pictures, the aim of which was to inspire discussion (Appendix A). It was surprising that these pictures did not ease participants’ stories to flow, but they preferred discussion.

6.1. Site and the Participants

The first author interviewed 13 male and 5 female students studying in a special vocational college. This institution was selected because it is one of the largest in Finland and has a long tradition of organizing intensive special support for the students. Each interview took about 15–30 minutes. The ages of the interviewees varied from 19 to 39 years, with most of the students being under 23 years old. At the time of the interviews, the participants were qualifying for their profession and leaving school within a few days. The fields of the 18 interviewed students were cleaning and property services (N = 5), technology (N = 3), media and visual expression (N = 3), ICT (N = 3), business (N = 2) and logistics (N = 2). The fields included in this study represented six of the eight taught on the campus of the institution we examined.

Permission to carry out this research was first sought from the school principal. After that, the class teachers were contacted, and the students expressed their consent to them. Interviews were arranged face to face, and they were recorded. A newsletter giving basic information about the research was addressed to all participants, and signed consent was obtained from the participants prior to completing the interviews. Participation was completely voluntary, which was discussed before starting the interviews and students were entitled to discontinue at any stage of the process.

6.2. Data Analysis

We applied data-driven, deductive content analysis to the research [63]. The transcription of the data was carried out by a research assistant who was acquainted with the practices. The data totaled about 235 pages of transcribed text and were anonymized by making only generic references to participants. After transcription, the data were reviewed multiple times to form an understanding of all the material. After that, the data were analyzed by using ATLAS.fi software for preliminary interpretations of the students’ experiences when qualifying for a profession. For example, one student described feelings as follows “Well, I feel excited at the moment […] I hadn’t thought about it earlier, but now when the summer holiday is about to begin, I hope that the future will bring something along and I could manage all right.” (Student 5). This was a close reading and reduction of data, which aimed at getting an intensive outline of it [64]. This analysis round produced a general view of the students’ spirit when completing their VET studying and taking their first steps towards life in the workforce.

Then, to particularize and itemize students’ perceptions, another analysis round by using ATLAS.ti software again was carried out. We wanted to scrutinize how students’ experiences reflected Biesta’s [8,9] domains of good education and created three codes for conceptualizing qualification, subjectification and socialization. Next, we will describe our analysis process in greater detail. If a student was describing the importance of academic or vocational learning, about school reports, these narratives were coded under the qualification parameter: “At least the diploma which I will receive will soon help me… One can prove that one has some kind of know-how.” (Student 17). If a student’s narrative included a subjectification parameter, meaning that the student was speaking about personal empowerment and growth, these were coded under subjectification: “Well, at least I have got rhythm into my life and my future looks a little bit brighter.” (Student 8). Finally, narratives that included social aspects, such as strengthening one’s position in the school community among peers or in society, were coded under the socialization parameter: “I think that the most important thing that VET has offered to me is the opportunity or the understanding about what it is to start to work […] When I began to study, I did not know anything about life in the workforce. Now I know and understand much better.” (Student 4). Furthermore, we scrutinized five specific interview questions more closely. These questions concerned students’ future prospects after one, five and ten years and their experiences of the most important thing during their VET studying and their opinions on how to improve VET in the future. We analyzed how Biesta’s [8,9] domains for good education and the ethos of a worker citizen were applicable.

As an analytical tool, we applied the narrative positioning analysis [65,66,67,68]. As explained in Bamberg [65] and Bamberg and Georgakopoulou [68], level 1 positioning refers to the way characters are positioned in relation to one another, while level 2 deals with interactional engagement between characters. We focused only on level 3 positioning to investigate how a student positions a sense of self with regard to dominant discourses [69]. That is, we aimed to find out who is a student with special needs in all that.

We argue that the students’ narratives are meaningful not only to reflect the past but to produce, adopt or resist the positions available at that moment and in the future. Narrative positioning analysis pursues examining and interpreting the narratives as a social action in that cultural context in which these have been told. Bamberg [65] argues that subjects are not only actualizing the identities available, but they are positioning themselves in different contexts. The present study analyzes the positions of Biesta’s parameters available in VET students’ narratives and reflects students’ positions in the normative discourse of a worker citizen. Furthermore, in the analysis process, we aimed to reveal the factors affecting the career trajectory of the students.

7. Findings

This section introduces the findings. First, we will present how students’ experiences reflected Biesta’s [8,9] domains—qualification, socialization, and subjectification—of education. After that, we will elaborate on the ethos of being a worker citizen. We will also introduce students’ views on how to improve the VET system, which reconnects us again with the different domains of education. Finally, we will present students’ prospects for the future.

7.1. Qualification Domain

The qualification domain of VET was available in a multifaceted way in this study. Students mentioned that acquiring vocational skills and learning something new was important for them, but they did not portray themselves as professionals in their fields. Participants spoke of their strong anxiety and pressure related to completing their studies. These students seemed to have feelings of both qualitative and social inadequacy. They experienced incapacity and uncertainty of themselves and described themselves as the lucky ones who had accomplished their missions as vocational students and received their diplomas with the help of the school personnel. They had an accommodating attitude with only modest demands for the future.

“I managed to complete my studying although I was uncertain of that earlier. I doubted whether this would be my line of trade at all. So, I am really happy now I’m completing my studying.”(Student 4)

“The most important thing has been the good teaching I received. I have learned new things… and new people, I have got to know new people, yes, that is one of the most important things.”(Student 11)

“I am not like other students. I am so self-critical… I feel that I am not good enough… I’m afraid that I don’t know enough about the workforce… I feel insecure and I am afraid of making mistakes. I don’t want to be wrong. It is terrible if one can’t cope and do what is expected.”(Student 7)

7.2. Socialization Domain

The socialization domain of VET for students with special educational needs was significant. It has provided the students with a certain representation of cultures, traditions and practices closely related to the work-life needs and expectations. Participating students narrated gratefully that they had succeeded in completing their studies and had earned a place in the student community. They set their modest hopes on finding their place in work after completing their studies. They talked about new friends, about the group spirit, about the anticipation of new social relations. The meaning of improved social skills, friends and peers was explicit and overwhelming.

R: “How would you describe the things you have received from school which will help you in work? What is the most important thing that you have learned over here?” S: “Well, to be with other people … social skills.”(Student 5)

7.3. Subjectification Domain

The importance of subjectification, the individual empowering domain of VET, was explicitly interpretable in the participating students’ narratives. It seemed to be the most important domain of VET for the participating students. The subjectification domain was closely related to socialization though it has often been understood as the opposite of the socialization domain of education [8]. Students said that during their VET studying, they had gained the courage, self-confidence and independent thinking needed in social relations and work. They voiced their gratitude that they have had the power to study. Some of them had interrupted their earlier studies, and they narrated the difficulties related to their social interaction. Maybe due to this, their ability to commit to studying VET and to their peers seemed to be consequential elements for them. Students described their opportunities to become individuals through their interaction with the VET culture and work and then again, that they exist as subjects in relation to their individuality, in relation to everything they have gained, learned, acquired and developed during their VET studying. They were overwhelmingly content with their opportunity to belong to the students’ community, to the vocational institution and that they had received a glimpse of work-life. They were grateful to teachers and school personnel for their support and understanding.

“Well, social situations have become easier for me. Earlier, I would have stayed at home alone.”(Student 8)

“My teacher has supported me a lot. I had thought about discontinuing my studying many times. But I am grateful that they did not give up on me.”(Student 14)

R: “If you think about your studying here, what has been the most important thing?” S: “I am not sure if this has anything to do with my studying but to become more independent.”(Student 4)

7.4. The Identity of a Worker Citizen

The participating students who were completing their VET studying have adopted the identity of a worker citizen: they have learned to do, but not to imagine. They were eager to insert themselves into the existing orders and to be a part of the worker citizens’ community. They seemed to be easily contented persons who did not set high expectations for the future. They explained that they had learned to respond to timetables, exercises and responsibilities. Their experiences of belonging to a group had become stronger. They said that individual help and understanding provided by the teachers and other school personnel had helped them significantly, but they still seemed to be unsure of their adequacy for work and for further studying.

“When I started my studying here, I planned to continue to a university of applied sciences. But now even though I know that it might be useful to continue, I doubt if I could concentrate on those studies. I have understood that those would be more self-guiding and there is no clear class structure. That would be hard for me.”(Student 18)

7.5. How to Improve the VET System

When we asked the students what is the most important thing that should be acknowledged when improving the VET system, the answers were surprisingly consistent and explicit. First, students spoke about a need and a wish for stronger, more individual encounters. According to the participants, teachers and other school personnel could identify students’ strengths better and build individual study paths even more consciously than currently has been done. Subjective growth, the subjectification domain of education, was highlighted in their narratives.

“Well, individuals should be recognised better. I am in different position because I am an adult. I can say what I want, but there are many students who can’t. They do what the teachers ask, and they don’t benefit from this education as much as possible if they had the courage to open their mouths and to say that they are interested in this and that and ask if they could invest in that. A more individual approach would be better.”(Student 3)

Participants required subjective empowerment to be more autonomous and independent in their thinking and acting, to enter the workforce and society with a sense of ownership of their future. They enquired for more attentive listening to figure out what practices and learning environments would support their studying at best.

“It should be acknowledged that sometimes one is not capable, one doesn’t have that energy… Young people and students especially are told to work, work and work… Life is not that simple. One must understand that there is much more inside everybody that you can’t recognise from the front.”(Student 14)

Secondly, the students highlighted the significance of establishing contacts with potential employers during their studies. They expressed their wish for closer and longer-lasting collaboration with employers. They explained that the most important thing is to learn and to understand the ground rules of work and of the work community. They did not emphasize their vocational skills or know-how in their stories, but it seemed that a sense of belonging, socialization, would be significant for the participating students.

“Well, because we are students in vocational school it would be useful, as I commented earlier, it would be useful to get used to work in real surroundings, in those which will be actual in your work, in your occupation.”(Student 4)

Participating students said that their families, specifically their mothers, were the most significant people when making plans and preparing for the future after VET study. They had helped students in conducting their personal affairs and studying. Moreover, teachers and other school personnel seemed to have an influence on the development of their plans. Some students also mentioned that their therapists and support people have had a significant role in the student’s trajectory. The socialization domain was also evident in those narratives when a student was not content with their social progress. It seemed that the sense of belonging was the most important factor to the participating students, and they needed help and support to find their place in the world.

“Originally, when I started my studying over here, I wanted to be more social than I was during my earlier studying. I would have loved to have new friends… But I failed, but it was important thing for me when I started my studying.”(Student 7)

7.6. How Students Position Themselves after VET

We asked the participants where they saw themselves after one year, after five years and after ten years after their VET studying if everything went fine. Socialization was the most important factor for the students. This means a sense of belonging, being part of the community and entering the labor market with a permanent job with a reasonable income. Still, their expectations were modest they would be easily contented employees and citizens. They said that income covering necessary expenses would be enough. It seemed that they adopted the identity of a worker citizen even though only one participant had a permanent contract after VET. Secondly, their aspirations included a subjective dimension: They desired increased independence, which appeared as getting their own apartment and looking after their interests and responsibilities independently.

“The most important thing for me would be to have a job, a permanent one, so that I would not have to think about tomorrow every day. […] I would love to stay in the same apartment where I live now. And I also wish that I could have the same friends as now. The only thing would be a permanent job, so that I don’t have to worry about bills and so on. That would be the most important thing for me.”(Student 18)

The students’ prospects five years after finishing VET were quite similar to those after one year. Still, having a job was the most significant element for the participants. However, now their narrations were completed with aspirations of having a partner or family. Even though it seemed that stability was the desired station in life, some students also spoke about career development. Needing more qualifications was only implicitly mentioned by the students.

“Well, I still have that apartment and job. And then, perhaps someday family would be a great addition to my life circle. That would be quite nice, if everything goes fine of course.”(Student 11)

Ten years after completing their VET studies, the students aspired to have a better occupation and better positions in the workforce. Some even considered themselves running a business at that time. Their aspirations were still modest, and they had an accommodating attitude to the future. Belonging to the community, socialization, seemed to be the most relevant of the domains.

“Well, if everything really would go all right, then it would be work and maybe I would live in slightly better apartment.”(Student 7)

8. Discussion

This study involving 18 VET students reports on how Biesta’s [8,9] domains of education—qualification, subjectification, and socialization—were mentioned in the students’ narratives when completing their three years of study at a vocational school that has a mandate to provide intensive special support for the students. Moreover, it describes who is a student in all that, as we reported the students’ perceptions of the aims of VET that they experienced. The study provides a more nuanced understanding of Finnish VET’s multiple purposes.

First, vocational institutions having a mandate to provide intensive special support had offered the participating students an extremely important opportunity to study, to be like any other young person, to belong to a student community and to blaze one’s trail to the labor market. These vocational institutions have worked as an important bridge-builder between the student and the world. VET has empowered them individually and socially. The students had become more independent in their thinking and acting, and they had made new friends. Their appetite for trying to live one’s life in the world with others has increased, which also asks from VET that it makes encounters with the real possible, encounters that enable a “reality check” [9] (pp. 97–98). Students reported being gratified to have had a chance to take advantage of VET, which meant acquiring the knowledge, skills and courage needed in work and life.

Secondly, understanding and the help provided by the school personnel, families and support from other quarters was unquestionably good for them. The students had succeeded with the versatile and long-lasting help of these sources. Anyhow, there is a need for even more attentive listening of VET students with special needs to figure out what practices and solutions would support each student’s studying and life at best [2]. Participation in VET has mostly helped the participating students in their academic and vocational achievement and not in developing their competencies to manage their own career and citizenship, which is in line with the earlier studies [39,40,47,48].

Thirdly, subjectification and socialization were emphasized in the participants’ narratives. Quite the opposite has been raised in earlier studies [28,52], as qualification has often been appraised as one of the major functions of VET, which means preparing students with skills appropriate for both the world of work and for citizenship. It seems that schools are emphasizing academic and vocational achievement instead of developing students’ competencies to manage their careers [42,43,47,48], whereas students with special educational needs emphasize their personal subjective growth. Even though students with special educational needs focused on their subjective empowerment and on their socialization, they perceived the professional qualification as a tool to achieve these. They aspired to be a successful member of society, a balanced and civilized individual and someone who could master the demands of the workforce, even though their expectations for the future were modest: Students in the VET system providing intensive special support for the students are trained to “do” and to “adapt” and not to “think” and to “imagine” what could be possible [70].

Finally, studying at a vocational institution has provided the students with an important turning point, but the strong connection of Finnish VET to qualification requirements and work-life might narrow VET’s scope of actions and impair the social belonging of students with intensive special needs. Work-life seems to be the most important client of VET and the future of its students. It gives justice and direction for VET, but it is de rigueur to also recognize and appreciate other domains of education. In the students’ narratives, work created an economic and social bond, which connects our findings to the socialization domain of education [8,9] and to the social construction of a worker citizen [37,38]. Much of the discussion with the participants was centered around the need for social belonging and for equal opportunities to study and to work and to find one’s own place in the world. This confirms the results in previous studies [44,71] of the importance of the school’s social aspect. It seems that the VET process has provided students with the chance to re-allocate their resources and build their identities based on common solidarity [32,33,34,40]. Paraphrasing Biesta [8] (p. 20), one could say that “through its socializing function VET inserts individuals into existing ways of doing and being.” The recognition of social and subjective domains of VET will open new possibilities also in co-operation with work-life.

This research has a few limitations. The students who volunteered for this research seemed to be positively engaged with the school and with learning. Consequently, they gave positive feedback about their vocational studying and about their future. Those who had a pessimistic attitude about studying and the future might have had a different perspective on VET’s aims and their study. Furthermore, our examination was located in one Finnish vocational institution with a mandate to provide intensive special support for the students, which produces a local and limited but significant impression of students’ opinions.

In conclusion, even though the participants had studied at a vocational school providing intensive special support, they would have appreciated even stronger individual support and teaching arrangements. They needed guidance and encouragement to master their studying, and they still needed to secure their employment or further studies. The participants did not wish for greater independence in planning and realizing a career, but instead they need sensitive, long-term support and guidance during and after their vocational studying in order to fully promote their personality and capabilities. Therefore, our results are not defending decreasing learning in schools, but students with special educational needs benefit from group-form education to strengthen their sense of belonging and self-confidence. The participating students’ request for more individual support could be interpreted as an explicit indication that there should be more time allocated to subjectification within the VET programs.

In line with Flower et al. [55], this study proves that VET providing intensive special support for the students impacts significantly on individuals and empowers them specifically in social settings. Biesta [9] suggests that socialization is about acquiring what Kemmis et al. [36] would call the practice of traditions of a trade/subject. Biesta [9] connects an image of a learning society in which the real encounters of who and what is the other are constant and continuous possibilities with the future of “Bildung”. Central in “Bildung” tradition has been the question of what constitutes an educated and cultivated human being, which has been an individualistic approach. In line with Biesta [9], our findings connect us with the view that “Bildung” is a lifelong task that should focus not only on individuals but on society as well. To that end, though Finnish VET is providing individually personalized study paths, even more attention should be paid to subjective and social growth, which means how schools could support their students individually to find their place in the world. The discussions concern not only individual students, teachers or employers but us all. VET has been an inclusive process wherein students with special educational needs have found an opportunity to enter the education, workforce and wider society, and they have acquired a sense of ownership of their future, but to implement their capabilities and strengths fully, there should be many options available to belong in the world.

The study recommends that VET should engage with the view of a learning society in which the real encounters with who and what is other are constant and continuous possibilities. The discussions of VET’s purposes and excellence should include its multiple dimensions, not only measurable outcomes, such as qualifications and employment rates, but also its social and subjective dimensions. In order to reinforce the work-oriented VET in Finland, closer co-operation between workplaces and schools is needed and better acknowledgment of students’ needs and conditions. Supportive workplace conditions will promote integration into the wider workforce [1]. Furthermore, the current article suggests further research that there might be a need to consider how teachers choose to embrace or reject their role as an activist, as a social agent to struggle for educational and social justice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., A.M., R.P. and E.K.K.; Data curation, S.R.; Formal analysis, S.R.; Investigation, S.R.; Methodology, S.R.; Resources, S.R.; Supervision, R.P. and E.K.K.; Visualization, S.R.; Writing—original draft, S.R.; Writing—review and editing, S.R., A.M., R.P. and E.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In Finland, The Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics [56] has stated, that an ethical review statement is required when the research deviates from the principle of informed consent; intervenes in the physical integrity of research participants; involves participants under the age of 15 being studied without parental consent; exposes participants to exceptionally strong stimuli; risks to cause mental harm that exceeds the limits of normal daily life; or involves a safety threat. Thus, Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the reason that the study did not fulfil the conditions stated by the Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Certain sections of data are available on request from the corresponding author but are not publicly available to ensure the privacy of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Questions

- What are your feelings now that you are finishing your studying?

- Do you think that you are ready for the work life? Could you explain why?

- What are your plans after your studies?

- Does the near future meet your expectations?

- If you think about your studying at this vocational college what has been the most important thing for you?

- What has changed most in your life? Has this change been pleasant one?

- How VET has helped you with your private life/ work life matters?

- What has been the most important thing in your vocational studying? Learning vocational skills or something else?

- How would you continue the following sentences?

- Now, when I am graduating and I look back in time and think about my vocational studies, the most important thing for me has been…

- I think that in future VET providers should consider…

- How do you see your life after 1 year, if all goes well?

- What are you doing, who are you living with, what is your life like?

- How do you see your life after 5 years, if all goes well?

- How do you see your life after 10 years, if all goes well?

- What things you feel you can influence in your own life at this moment? What things you would like to influence?

- In what things your vocational college has helped you most?

- Who has been the most important person in your life when planning your future and getting ready for it?

- Is there something that you would like to add to this interview?

References

- Cavanagh, J.; Meacham, H.; Pariona Cabrera, P.; Bartram, T. Vocational learning for workers with intellectual disability: Interventions at two case study sites. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, A.-M.; Jahnukainen, M. Tuen tarve, työelämäpainotteisuus ja itsenäisyyden vaatimus ammatillisen koulutuksen konteks-tissa. Amm. Aikakauskirja 2018, 20, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schanhorst, U.; Kammermann, M. Who is included in VET, who not? Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Äikäs, A. Toiselta Asteelta Eteenpäin. Narratiivinen Tutkimus Vaikeavammaisen Nuoren Aikuisen Koulutuksesta ja Työllisty-misestä. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland, August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Billet, S. The standing of vocational education: Sources of its societal esteem and implications for its enactment. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2014, 66, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazey, B.L.; Heilig, J.V.; Cole, H.A.; Sumbera, M. The more things change, the more they stay the same: Comparing special education students’ experiences of accountability reform across two decades. Urban Rev. 2015, 47, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlberg, P. Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. J. Educ. Chang. 2008, 11, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Risking ourselves in education: Qualification, socialization and subjectification revisited. Educ. Theory 2020, 70, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, H. Building quality foundations: Indicators and instruments to measure the quality of vocational education and training. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2009, 61, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, S.; Faurschou, K. Implementing the European quality assurance in vocational education and training (EQAVET) at national level: Some insights from the PEN Leonardo Project. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2016, 3, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Education, measurement and the professions: Reclaiming a space for democratic professionality in education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2017, 49, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siirilä, J.; Laukia, J. Mihin Menet Ammattikasvatus? Ammattikasvatuksen Tutkimuksen Suuntaukset Suomessa. eSignals Research. 2021. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2021101450990 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Wheelahan, L. Doctoral thesis abstracts in vocational education. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 73, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niittylahti, S. “Mä Olen Saanut Mahdollisuudet Oppia” Opintoihin Kiinnittyminen Ammatillisessa Koulutuksessa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland, August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanoff, A. Mukava Mennä Iloisella Mielellä. Narratiivinen Tutkimus Kehitysvammaisten Nuorten Toisen Asteen Opinnoista. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland, April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, A.-M. Erityisiä Koulutuspolkuja? Tutkimus Erityisopetuksen Käytännöistä Peruskoulun Jälkeen. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen, K.; Naskali, P.; Korhonen, M.; Keskitalo-Foley, S. Internal entrepreneurship—A Trojan horse of the neoliberal governance of education? Finnish pre- and in-service teachers’ implementation of and resistance towards entrepreneurship education. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 2011, 9, 341–374. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, D. How possible is socially just education under neo-liberal capitalism? Struggling against the tide? Forum Promot. 3-19 Compr. Educ. 2012, 58, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukia, J.; Karjalainen, A. Ammatillinen koulutus ja yhteiskunta. Amm. Aikakauskirja 2019, 21, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland. Vocational Education and Training Reform Approved—The Most Extensive Education Reform in Decades. 2017. Available online: https://minedu.fi/-/ammatillisen-koulutuksen-reformi-hyvaksyttiin-suurin-koulutusuudistus-vuosikymmeniin?_101_INSTANCE_vnXMrwrx9pG9_languageId=en_US (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Cedefop. Vocational Education and Training in Finland: Short Description. Publications Office, 2019. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/841614 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Lahelma, E. Ammatillista koulutusta tutkimaan. In Ammatillinen Koulutus ja Yhteiskunnalliset Eronteot; Brunila, K., Hakala, K., Lahelma, E., Teittinen, A., Eds.; Gaudeamus: Helsinki, Finland, 2013; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, M.; Masschelein, J. The learning society and governmentality: An introduction. Educ. Philos. Theory 2006, 38, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Culture. Proposals of the Group for Developing Intensive Special Support in Vocational Education and Training. Final Report of the Development Group. Publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland 2019:23. Available online: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/161647/OKM%202019%2023%20Ammatillisen%20koulutuksen%20vaativa%20erityinen%20tuki.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Finlex Data Bank. The Law on Vocational Education 531/2017. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2017/20170531 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Special Education. Students of Special Vocational Education by Place of Provision of Teaching, 2004–2018; Statistics Finland: Helsinki, Finland; Available online: http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/2019/erop_2019_2020-06-05_tau_010_en.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Arnesen, A.-L.; Lundahl, L. Still social and democratic? Inclusive education policies in the Nordic welfare states. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 50, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzki, T.R. A primer on practices. In Practice Based Education; Higgs, J., Barnett, R., Billett, S., Hutchings, M., Trede, F., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paju, B. An Expanded Conceptual and Pedagogical Model of Inclusive Collaborative Teaching Activities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Priorities for 2019–2024. The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 Principles. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/priorities/deeper-and-fairer-economic-and-monetary-union/european-pillar-social-rights/european-pillar-social-rights-20-principles_en (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Avis, J. Crossing boundaries: VET, the labour market and social justice. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 5, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, S.R.d.S.; Duarte, M.M.N.P.; Veloso, J.R.P. Paths, misplacements and challenges in Brazilian VET for people with disability. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vornholt, K.; Villotti, P.; Muschalla, B.; Bauer, J.; Colella, A.; Zijlstra, F.; Van Ruitenbeek, G.; Uitdewilligen, S.; Corbière, M. Disability and employment—Overview and highlights. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 27, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. The School and Society; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Edwards-Groves, C.; Hardy, I.; Grootenboer, P.; Bristol, L. Changing Practices, Changing Education; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm, E.; Teittinen, A. Vammaiset nuoret ja työntekijäkansalaisuus. Osallistumisen esteitä ja edellytyksiä. Soc. Insur. Inst. Finl. Stud. Soc. Secur. Health 2014, 133, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Isopahkala-Bouret, U.; Lappalainen, S.; Lahelma, E. Educating worker-citizens: Visions and divisions in curriculum texts. J. Educ. Work. 2014, 27, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, M. The relevance of class in education policy and research. The case of Sweden’s vocational education. Educ. Inq. 2012, 3, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.S. The erosion of citizenship. Br. J. Sociol. 2001, 52, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk-Åman, C.; Holmgren, R.; Pettersson, G.; Ström, K. Nordic research on special needs education in upper secondary vocational education and training: A review. Nord. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 11, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryökkynen, S.; Pirttimaa, R.; Kontu, E. Interaction between students and class teachers in vocational education and training: ‘Safety distance is needed’. Nord. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 9, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryökkynen, S.; Maunu, A.; Pirttimaa, R.; Kontu, E. From the shade into the sun: Exploring pride and shame in students with special needs in Finnish VET. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, A.-M.; Jahnukainen, M. Educating self-governing learners and employees: Studying, learning and pedagogical practices in the context of vocational education and its reform. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 23, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågren, S.; Pietilä, I.; Rättilä, T. Palkkatyökeskeisen ajattelun esiintyminen ammattiin opiskelevien työelämäasenteissa. In Good Work! Youth Barometer 2019; Haikkola, L., Myllyniemi, S., Eds.; Nuorisotutkimusseura: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, T.; Cavanagh, J. Re-thinking vocational education and training: Creating opportunities for workers with disability in open employment. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draaisma, A.; Meijers, F.; Kuijpers, M. The development of strong career learning environments: The project ‘Career orientation and guidance’ in Dutch vocational education. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 70, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorff, K.M. Career Conversations in Senior Secondary Vocational Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, P.; Hellgren, M.; Köpsén, S. Factors influencing the value of CPD activities among VET teachers. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 5, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiríksdóttir, E.; Rosvall, P.-Å. VET teachers’ interpretations of individualisation and teaching of skills and social order in two Nordic countries. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 18, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautz, H. The ‘conduct of conduct’ of VET teachers: Governmentality and teacher professionalism. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, M.; Ledman, K.; Rosvall, P.-Å.; Rönnlund, M. Socialisation and citizenship preparation in vocational education: Pedagogic codes and democratic rights in VET-subjects. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapani, A.; Salonen, A. Identifying teachers’ competencies in Finnish vocational education. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Train. 2019, 6, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wheelahan, L.; Moodie, G. Vocational education qualifications’ roles in pathways to work in liberal market economies. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2017, 69, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, R.L.; Hedley, D.; Spoor, J.R.; Dissanayake, C. An alternative pathway to employment for autistic job-seekers: A case study of a training and assessment program targeted to autistic job candidates. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Advisory Board on Research Ethics [TENK]. Ihmiseen Kohdistuvan Tutkimuksen Eettiset Periaatteet Ja Ihmistieteiden Eettinen Ennakkoarviointi Suomessa. Tutkimuseettisen Toimikunnan Julkaisuja 3. 2019. Available online: https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2021-01/Ihmistieteiden_eettisen_ennakkoarvioinnin_ohje_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Mietola, R.; Miettinen, S.; Vehmas, S. Voiceless subjects? Research ethics and persons with profound intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnukainen, M. Erityisopetus ja oppivelvollisuus. Kansakoulun marginaalista yleisopetuksen yhteyteen. Koulu ja Menneisyys 2021, 58, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, A.; Mietola, R.; Niemi, A.-M. Koulutususkon rajoilla: Koulutuksen julma lupaus kehitys- ja vaikeavammaisille opiskelijoille. In Koulutuksen Lupaukset ja Koulutususko; Kasvatussosiologian vuosikirja 2. Kasvatusalan tutkimuksia 79; Silvennoinen, H., Kalalahti, M., Varjo, J., Eds.; Suomen kasvatustieteellinen seura: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2018; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, A. Qualitative research in education: The origins, debates, and politics of creating knowledge. Educ. Stud. 2013, 49, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1991, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yauch, C.A.; Steudel, H.J. Complementary use of qualitative and quantitative cultural assessment methods. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinchman, K.A.; Moore, D.W. Close reading. A cautionary interpretation. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2013, 56, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M. Positioning between structure and performance. J. Narrat. Life Hist. 1997, 7, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M. Positioning with Davie Hogan. Stories, tellings, and identities. In Narrative Analysis: Studying the Development of Individuals in Society; Daiute, C., Lightfoot, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, M. Form and functions of ‘slut bashing’ in male identity constructions in 15-year-olds. Hum. Dev. 2004, 47, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M.; Georgakopoulou, A. Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text Talk 2008, 28, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A. Positioning level 3: Connecting local identity displays to macro social processes. Narrat. Inq. 2013, 23, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, M.; Rosvall, P.-Å.; Ledman, K. The vocational–academic divide in neoliberal upper secondary curricula: The Swedish case. J. Educ. Policy 2017, 32, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, S. ‘Trying to push things through’: Forms and bounds of agency in transitions of school-age young people. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).