Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Policy Reform in Unstable States

3. Military Coups in Myanmar

4. Myanmar Education Reforms: 2010–2020

5. Higher Education (HE) and the Reforms

6. Methodology

6.1. Context of the Research

6.2. Participants

6.3. Data Collection and Analysis

- How did COVID affect the Higher Education(HE)/Teacher Education (TE) sector? (ကိုဗစ်ကြောင့် တက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေး သို့မဟုတ် ဆရာအတတ်သင်ပညာရေး ထိခိုက်ရပုံကို ဖြေပါ။)

- How did the coup affect the HE/TE sector? (အာဏာသိမ်းမှုကြောင့် တက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေး သို့မဟုတ် ဆရာအတတ်သင်ပညာရေး ထိခိုက်ရပုံကို ဖြေပါ။)

- What should be the vision of the HE/TE sector for Myanmar’s future? (တက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေး သို့မဟုတ် ဆရာအတတ်သင်ပညာရေး ၌ ထားရှိသင့်သည့် မျှော်မှန်းချက်ပန်းတိုင်ကို ဖော်ပြပါ။)

- How does the ideal vision of the HE/TE sector contrast with what the Tatmadaw leaders see as HE/TE? (ထားရှိသင့်သည့် တက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေး သို့မဟုတ် ဆရာအတတ်သင်ပညာရေး မျှော်မှန်းချက်ပန်းတိုင် နှင့် စစ်တပ်မှ တက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေး သို့မဟုတ် ဆရာအတတ်သင်ပညာရေး အပေါ်မြင်သောအမြင် ခြားနားကွဲပြားပုံကို - ခြားနားသည်ဟုအမြင်ရှိက - ဖော်ပြပါ။)

- What future does CDMers have? How is it different from Non CDMers? (စီဒီအမ်များ တွေ့ကြုံရမည့် အနာဂါတ်ကို မည်သို့မြင်ပါသလဲ။ နန်း စီဒီအမ်များ နှင့် မည်သို့ခြားနားပါသလဲ။).

7. Findings

7.1. COVID-19

Because of COVID, the exams in most universities were postponed. Students who were going to graduate cannot finish their studies. They [students] are distracted from their learning and in the middle of nowhere. (HE-PP)

Initially, in the first wave, it brought positive effects, teachers inevitably learning new things to cope with modern digitalized education, like LMS [Learning Management Systems], virtual classrooms and so on. For the second and third wave + coup, there were more negative ones especially for students. Learning was almost shut down. (HE-YNSN)

COVID seriously affected the HE. No effective countermeasures to COVID have been taken for students not to disconnect their studies such as Online teaching, Hybrid teaching etc. Although some universities were reopened and had students attend the face-to-face classes for two weeks and let all-level of students pass exams, which really affect education quality. (HE-KTDM)

The first is that the Ministry of Education has not properly trained teacher educators for online teaching, so it took longer than necessary to teach online. As a result, student teachers have lost their right to study. Another is that professional development programs for teacher educators are not as effective as face-to-face online switching. Lack of interest, Lack of participation (TE-TT)

The pandemic affected Teacher Education seriously. Education Degree Colleges had to stop their regular system and the teaching-learning process had been totally ended for student-teachers. But that of teacher-educators could continue with online learning (British Council’s Tree Process could proceed with online). In that situation, teacher-educators had to learn the use of the digital platform on learning not only for their professional development but for the preparation of giving online lectures to student-teachers. So, we can say that even the pandemic affected the Teacher Education sector negatively, it could change that issue to the opportunity of learning and using digital platforms for the Teacher-educators. (TE-MP)

Because of the COVID pandemic, to our Teacher Educator sector, we faced the failure of implementing incoming plans. We did not get a chance to keep reforming teacher education. We, teacher educators, lost opportunities to attend programs or projects for continuous professional development. For our student teachers, they also lost opportunities for continuously learning as we could not give and share with them teaching knowledge what they need to know. (TE-AM)

7.2. Coup (The Third Coup d’état in 2021)

7.3. Higher Education’s Reaction to the Coup

First, it stopped all the progress the HE is having both in its management system and in its academic research. Second, students cannot have the continuous education via online programme that was being planned during the COVID before Coup. Third, many good teachers give up their spots as they no longer believe in the education system operated by the Military. (HE-PP)

Disastrous! Over 90% students and almost 40% (initially almost 80%) teachers and staffs joined CDM, boycotting the junta, saying bye to their universities as long as they are under the junta’s control. Some teachers and students try to carry on education in all means possible but the majority cannot. (HE-YNSN)

Coup affected the HE seriously. Many staff have participated in CDM to protest it. As a result, some have been hidden themselves in places where they cannot be known, or some cannot go to international universities to pursue further studies, which has negatively effects not only for themselves but also on the HE. (HE-KTDM)

The coup affected the Teacher Education Sector negatively and seriously because those who are in the middle of the coup and who accepted it keep leading the teacher education sector. There would be no bright future because of those people who could not determine which is right or wrong and would like to encourage the bad people. (TE-AM)

Because of the Coup, CDM has developed. Many teachers and students participated in CDM and were involved in the revolution. So formal learning opportunities for student-teacher had been destroyed by the coup and teacher educators lost their jobs. Before the coup, we were going to implement the four-year new curriculum and upgrading Education Colleges to Education Degree Colleges, and all our plans have been destroyed by the coup. (TE-MP)

The main reason is that student teachers are losing their right to study. Some have given their lives in opposition to the dictator. Some have committed suicide due to mental illness. CDM teacher educators have been wrongfully arrested by the dictatorial military council. There were also killings. The trust between the teacher and the student; Respect and value. Understandings were ruined by a group of dictators. (TE-TT)

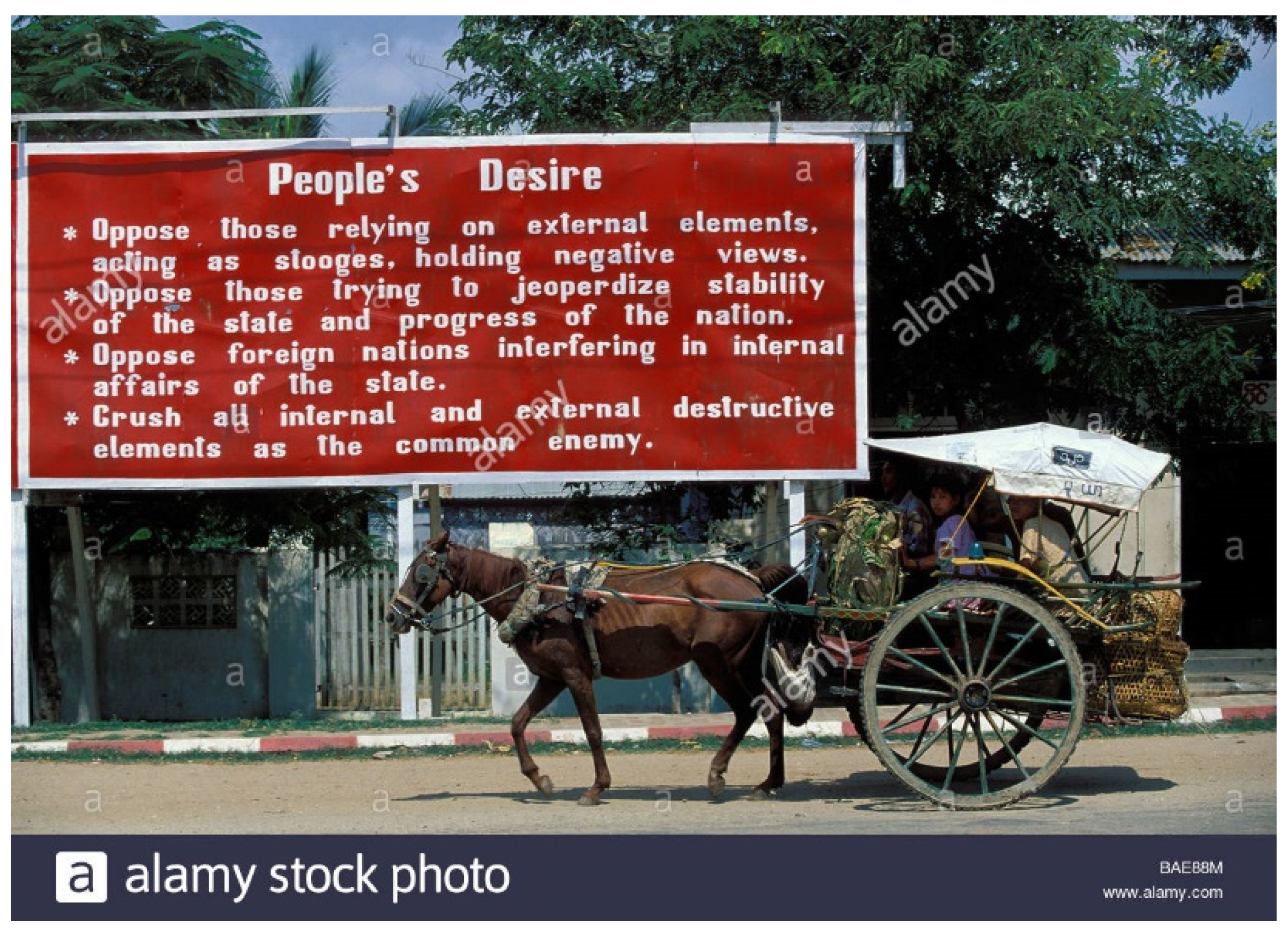

7.4. Conflict: Clash of Ideologies

Tatmadaw does not really have any good-will on the development of Myanmar’s education. For them, it appears people should be lacking thinking skills so that they can control people and exploit country’s resources for their own sake. They might be thinking that the lower the education level, the better for them to take advantage of it. (HE-KTDM)

The junta sees academic freedom, autonomy and international collaboration as their threats. Teachers are just staff to promote a stratocracy state (which they think would be peaceful and developed and in reality not. My ideal vision is the opposite. (HE-YNSN)

We see education as a kind of political affair in a country. A teacher should have a sound knowledge and interest in the political situation of his or her country and wants to participate in its movement. But, the military junta see education separately, not related to the political crisis. We could say it is a kind of being provincial in outlook. (TE-MP)

Although we focus on teacher education to create updated themes for improving and reforming a better teacher education system, the Tatmadaw leaders see as Teacher Education sector that it is not as important as what they do to get authority on Myanmar people. To my mind, the junta has been creating the teacher education system outdated as we have postponed all our upcoming education plans. (TE-AM)

I find that the HE of Myanmar is quite reluctant to collaborate and cooperate with other organizations. The hierarchy system of the organization doesn’t allow people, teaching staffs and administrative staffs, to have autonomy and will to develop themselves. The closed structure of the system make people work in the government since the beginning of their working life till they get pension. (HE-PP)

Teacher education is about thinking, thinking, thinking. Values It is to cultivate teachers who are constantly learning based on skills. The military’s view is that teachers are more likely to give birth to children who will say “yes” than “think” rather than think. Teacher education is seen as the best place to brainwash the people. (TE-TT)

The vision of the HE should be promoting quality of teachers from all levels to produce quality human resources for different sectors by providing Continuous Professional Development activities to teachers, by reviewing the curriculum and updating it accordingly to the fast flowing changes of today’s era. (HE-KTDM)

My expected vision of the future HE is to build up an active and innovative society for the teachers and students which advocates the transparent working system. I hope students who finished their degrees can have the appropriate job opportunities and they can have opportunities to equip themselves with the required skills. (HE-PP)

In my opinion, based on the current political crisis, the vision of the Teacher Education sector should include those facts such as to produce educated teachers with high knowledge of Myanmar Political situation and the role of education in a political affair, federal education system, and respect to equity and inclusion. (to produce educated teachers who can perform the federal education system successfully). (TE-MP)

The vision of the Teacher Education Sector of Myanmar’s future should be with a variety of updated, inclusive, and modernized themes to implement the federal education system because we must lead our sector to be with international standards. To systematically reform our sector, there must be included 21st-century skills and therefore, qualified teachers would be well- produced and it would become an inclusive and comprehensive teacher educator system. (TE-AM)

1. Tear down the decaying systems of hidden academic frauds and deep rooted bureaucracy. (Eliminate all corruptions in it)

2. Build a Higher Education System of REAL autonomy, academic freedom + quality assurance.

3. Adapt in accordance with the needs of a Federal nation, not a single race state. (HE-YNSN)

8. Discussion: Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict

9. Conclusions

CDMers hope to become a democratic nation and have a federal education system. They love the truth and want to leave the military government. They have no wish to stay long with fear under the junta. They want to get freedom from fear and hope to create a better teacher education system with qualified and democratic leaders. Alternatively, non-CDMers are different from CDMers because those who keep working under the military government want to stay their lives with ease and comfort. They do not have the sense to differentiate what is right or wrong. (TE-AM)

Ironically, neither will have real universities to ethically work in, under the junta. CDMers still have students but no secure places to conduct classes. Non-CDMers still get salaries but almost no students accepting them. As long as students can respect them as moral teachers, teachers can be teachers, which will be difficult for Non-CDMers. (HE-YNSN)

CDM teachers can be emotionally and physically insecure. The safety of their family members can also be compromised. They may also lose the right to further education locally. However, with the help of international organizations, CDM students might be able to continue their education. CDM teachers will definitely gain the respect and trust of the people which Non-CDMers can never hope to get again. It is true that some CDM teachers will have to give up their beloved teaching profession to make a living but there will also be others who might still get a job in their same profession. These CDM teachers will lead the way for future federal education and rehabilitation. Some CDMs might not be working as teachers anymore but they will still be very important in carrying out national reconstruction efforts in collaboration with local and foreign organizations. (TE-TT)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiroma, J.A. Democratic Citizenship Education and Its Implications for Kenyan Higher Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, B.; Lockyer, A. Education for Democratic Citizenship: Issues of Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Luescher-Mamashela, T.M. The University in Africa and Democratic Citizenship; Center for Higher Education Transformation: Wynberg, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Metro, R. Students and teachers as agents of democratization and national reconciliation in Burma: Realities and possibilities. In Metamorphosis: Studies in Social and Political Change in Myanmar; Nus Press: Singapore, 2011; pp. 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Houtman, G. Mental Culture in Burmese Crisis Politics: Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy; Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Myint-U, T. The Making of Modern Burma; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lall, M. Myanmar’s Education Reforms–A Pathway to Social Justice? UCL Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiko Howson, C.; Lall, M. Higher Education reform in Myanmar: Neoliberalism versus an inclusive developmental agenda. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2020, 18, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, J. Education and fragile states. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2007, 5, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Agency for International Development (USAID). Youth and Conflict; USAID Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Lerch, J.C.; Buckner, E. From education for peace to education in conflict: Changes in UNESCO discourse, 1945–2015. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2018, 16, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L. Education and Conflict: Complexity and Chaos; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baćević, J. From Class to Identity: The Politics of Education Reforms in Former Yugoslavia; Central European University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kempner, K.; Jurema, A.L. The Global Politics of Education: Brazil and the World Bank. High. Educ. 2002, 43, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R. Higher education as a global commodity: The perils and promises for developing countries. Obs. Bord. High. Educ. 2007, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Balarin, M. Promoting educational reforms in weak states: The case of radical policy discontinuity in Peru. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2008, 6, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, D. The policy reassembly of Afghanistan’s higher education system. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2019, 17, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esson, J.; Wang, K. Reforming a university during political transformation: A case study of Yangon University in Myanmar. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazawi, A.E. Contrasting Perspectives on Higher Education in the Arab States. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Smart, J., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2005; pp. 133–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiek, M. The two decades of privatization in Polish higher education: Cost-sharing, equity, and access. Die Hochsch. 2008, 2, 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Abdesallem, T. Financing Higher Education in Tunisia; Economic Research Forum: Cairo, Egypt, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner, E.; Khuloud, S. Syria’s Next Generation: Youth Unemployment, Education, and Exclusion. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle East. 2010, 3, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. New directions in policy borrowing research. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verger, A.; Clara, F.; Adrián, Z. The Privatization of Education: A Political Economy of Global Education Reform; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- George, J.; Theodore, L. Exploring the Global/Local Boundary in Education in Developing Countries: The Case of the Caribbean. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2011, 41, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A.; Steiner-Khamsi, G.; Lubienski, C. The Emerging Global Education Industry: Analysing Market-Making in Education through Market Sociology. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2017, 15, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.D.; Oliveira, J. Global education policy in African fragile and conflict-affected states: Examining the Global Partnership for Education. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. What is Wrong with the ‘What-Went-Right’ Approach in Educational Policy? Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tierney, W.G. The role of tertiary education in fixing failed states: Globalization and public goods. J. Peace Educ. 2011, 8, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, W. Transformation Research and Comparative Educational Studies. In After Communism and Apartheid, Transformation of Education in Germany and South Africa; Reuter, L.R., Döbert, H., Eds.; Peter Lang: Frankfurt Am Main, Germany, 2002; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki, L.; Fairclough, N. Discourse in Late Modernity; EUP: Edinburgh, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Althusser, L. On Ideology; Verso: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Szkudlarek, T.; Stankiewicz, Ł. Future perfect? Conflict and agency in higher education reform in Poland. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2014, 19, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounko, T.; Smale, W. Modernization of Russian higher education: Exploring paths of influence. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2007, 37, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, S.; Barakat, S. Higher Education as the Catalyst of Recovery in Conflict-Affected Societies. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2016, 14, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.G.; Quaynor, L. Constructing citizenship in post-conflict contexts: The cases of Liberia and Rwanda. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2017, 15, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, A.; Starkey, H. Changing Citizenship: Democracy and Inclusion in Education; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tsur, D. Academic studies amid violent conflict: A study of the impact of ongoing conflict on a student population. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2009, 7, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Cardozo, M.T.; Shah, R. ‘The fruit caught between two stones’: The conflicted position of teachers within Aceh’s independence struggle. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2016, 14, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, E.; Giannini, T. Beyond the Coup in Myanmar: Echoes of the Past, Crises of the Moment, Visions of the Future; Just Security and the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.justsecurity.org/75826/beyond-the-coup-in-myanmar-echoes-of-the-past-crises-of-the-moment-visions-of-the-future/ (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Metro, R. Whose Democracy? The University Student Protests in Burma/Myanmar, 2014–2016. In Universities and Conflict; Millican, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 205–218. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315107578-15/whose-democracy-rosalie-metro (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Lall, M. Understanding Reform in Myanmar; Hurst: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burma Campaign, U.K. About Burma. 2021. Available online: https://burmacampaign.org.uk/about-burma/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- CESR. Comprehensive Education Sector Review: Technical Annex on the Higher Education Subsector, Phase 1; Government of Myanmar: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2013. Available online: http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/Report_CESR_Phase_1_Technical_Annex_on_the_Higher_Education_Subsector_Mar2013.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- CESR. Comprehensive Education Sector Review: Technical Annex of the Higher Education Subsector: Phase 2; Government of Myanmar: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2014.

- Lopes Cardozo, M.T.A.; Maber, E.J.T. (Eds.) Sustainable Peacebuilding and Social Justice in Times of Transition: Findings on the Role of Education in Myanmar; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mid Term Review. Government of Myanmar. Mid Term Review NESP 2016–2021; Ministry of Education: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Presentation by Dr Aung Khin Myint. Available online: http://moe.gov.mm (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Higgins, S.; Paul, N.T.K. Navigating teacher education reform: Priorities, possibilities and pitfalls. In Sustainable Peacebuilding and Social Justice in Times of Transition; Cardozo, M.T.A.L., Maber, E.J.T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop, L. Encountering Internationalisation: Higher Education and Social Justice in Myanmar. Doctoral Thesis, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- May San, Y. Presentation on ‘Upgrading of Education Colleges to Four-Year Degree Colleges’, Higher Education Forum. 2017. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.mm/ (accessed on 9 August 2021)(In Myanmar Language).

- Connecting Higher Education Institutions for a New Leadership on National Education. In [CHINLONE] (2018). Myanmar’s Higher Education Reform: Which Way Forward? University of Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2018. Available online: https://site.unibo.it/chinlone/it/report (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Welch, A.; Hayden, M.; Myanmar Comprehensive Education Sector Review (CESR) Phase 1: Rapid Assessment. Technical Annex on the Higher Education Subsector. CESR. Myanmar. 2013. Available online: http://www.cesrmm.org/assets/home/img/cesr-phase%201_rapid%20assessment_higher%20ed%20subsector_technical%20annex_26mar13_for%20distrib_cln_newlogo.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Kamibeppu, T.; Chao, R.Y., Jr. Higher Education and Myanmar’s Economic and Democratic Development. Int. High. Educ. 2017, 88, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Education. National Education Strategic Plan 2016–2021; Government of Myanmar: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2016. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.mm/en/?q=content/national-education-strategic-plan (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Hong, M.S.; Chun, Y.J. Symbolic habitus and new aspirations of higher education elites in transitional Myanmar. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, Y. Reconsidering the origin of the contemporary Myanmar politics. JPN J. Southeast Asian Stud. 2019, 56, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. 2 March 2021. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/node/378044/printable/print (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Bhattacharya, S. Institutional review board and international field research in conflict zones. PS Political Sci. Politics 2014, 47, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulz, P. Recognizing research participants’ fluid positionalities in (post-) conflict zones. Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Learning and earning losses from COVID-19 school closures in developing Asia; Special Topic of the Asian Development Outlook; Asian Development Outlook: Manila, Philippines, 2021.

- MRTV (2021). Available online: https://www.myanmartvchannels.com/education-channel.html (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL). The 2020 Myanmar General Elections: Democracy Under Attack._ANFREL International Election Observation Mission Report; ANFREL: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Annawitt, P. Myanmar’s junta is in a much weaker position than many realize Nikkei Asia. 2021. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Myanmar-s-junta-is-in-a-much-weaker-position-than-many-realize (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Channel News Asia (4 March 2021). Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/myanmar-coup-activists-vow-more-protests-after-38-killed-14329382 (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- The Lancet. Myanmar’s democracy and health on life support. Lancet 2021, 397, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, M. Myanmar Higher Education in light of the military coup. Int. High. Educ. 2021, 107, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Myanmar Coup: Teachers Join Growing Protests against Military. 5 February 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55944482 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Naw Say Phaw Waa. 2021. Junta Announces a Return to Classes–But Not Normality. University World News, 23 April. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210423115051629 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- DW. 2021. Myanmar: First Protester Dies in Rallies Against Military Takeover. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/myanmar-first-protester-dies-in-rallies-against-military-takeover/a-56622106 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma). 2021. Available online: https://aappb.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Aljazeera. 2021. 75 Children Killed, 1,000 Detained Since Myanmar Coup: UN Experts. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/17/75-children-killed-1000-detained-since-myanmar-coup-un-experts (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Britannica. 2021. Myanmar: The Emergence of Nationalism. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Myanmar/The-emergence-of-nationalism (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Cheesman, N. Legitimising the Union of Myanmar through Primary School Textbooks. Master’s Thesis, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia, 2002. Available online: https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/legitimising-the-union-of-myanmar-through-primary-school-textbook (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Metro, R. History Curricula and the Reconciliation of Ethnic Conflict: A Collaborative Project with Burmese Migrants and Refugees in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baronio, F. Myanmar’s Army Will Do Whatever It Takes to Hold Onto Power. 2021. Available online: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/myanmars-army-will-do-whatever-it-takes-hold-power-31157 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Mullen, M. On Pathways That Changed Myanmar: A Précis. J. Int. Glob. Stud. 2017, 8, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Teacircleoxford. Targets of Oppression and Scrutiny: Being a University Teacher in Military-Ruled Myanmar. 2021. Available online: https://teacircleoxford.com/2021/10/25/targets-of-oppression-and-scrutiny-being-a-university-teacher-in-military-ruled-myanmar (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Reuters. 2021. More than 125,000 Myanmar Teachers Suspended for Opposing Coup. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/more-than-125000-myanmar-teachers-suspended-opposing-coup-2021-05-23/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Saito, E. Ethical challenges for teacher educators in Myanmar due to the February 2021 coup. Power Educ. 2021, 13, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naw Say Phaw Waa. 2021. Military Re-Opens Universities but Few Students Attend. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210506230745241 (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Myanmar Now. 2021. Some 90 Percent of Myanmar Students Refuse to Attend School under Coup Regime, Teachers Say. Available online: https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/some-90-percent-of-myanmar-students-refuse-to-attend-school-under-coup-regime-teachers-say?page=66&width=500&height=500&inline=true (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Irrawaddy. 2021. Myanmar Schools Open, But Classrooms Are Empty as Students Boycott. Available online: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-schools-open-but-classrooms-are-empty-as-students-boycott.html (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Kostovicova, D.; Knott, E. Harm, change and unpredictability: The ethics of interviews in conflict research. Qual. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; DeFronzo, J. A Comparative Framework for the Analysis of International Student Movements. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2009, 8, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, Z. 2007. Iraq’s Universities near Collapse. Chron. High. Educ. 2007, 53, A35. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Htut, K.P.; Lall, M.; Kandiko Howson, C. Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020067

Htut KP, Lall M, Kandiko Howson C. Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms? Education Sciences. 2022; 12(2):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020067

Chicago/Turabian StyleHtut, Khaing Phyu, Marie Lall, and Camille Kandiko Howson. 2022. "Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms?" Education Sciences 12, no. 2: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020067

APA StyleHtut, K. P., Lall, M., & Kandiko Howson, C. (2022). Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms? Education Sciences, 12(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020067