Abstract

Over the past three decades, our understanding of science learning in early childhood has improved exponentially and today we have a strong empirically based understanding of science experiences for children aged three to six years. However, our understanding of science learning as it occurs for children from birth to three years, is limited. We do not know enough about how scientific thinking develops across the first years of life. Identifying what we do know about science experiences for our youngest learners within the birth to three period specifically, is critical. This paper reviews the literature, and for the first time includes children in the birth to three period. The results are contextualised through a broader review of early childhood science education for children aged from birth to six years. Findings illustrated that the empirical research on science concept formation in the early years, has focused primarily, on children aged three to six years. The tendency of research to examine the process of concept formation in the birth to three period is also highlighted. A lack of empirical understanding of science concept formation in children from birth to three is evident. The eminent need for research in science in infancy–toddlerhood is highlighted.

Keywords:

science; early childhood; science education; literature review; concepts; infants; toddlers; preschoolers 1. Introduction

We are living in times characterised by an explosion of scientific knowledge [1] and rapid rates of innovation in technology [2]. Globally, however, there exists a decreasing trend in student interest in science upon school completion [3] and in Australia, students’ performance in science is declining [4]. It is now widely accepted that early science learning experiences are essential for the development of children’s scientific knowledge and inquiry skills [5]. Appropriate scientific work can and should begin as early as possible for all children [5,6,7]. Concerningly, however, research has shown that current early years provisions fail to meet children’s potential [8]; young children’s science learning is not being systematically stimulated [9] and there are significantly fewer opportunities for young children to engage with science activities in comparison to other content areas [10]. In addition, many early childhood teachers feel discomfort when teaching sciences [11], and have expressed concern at the lack of appropriate pedagogical strategies [12,13]. The eminent need to provide more quality and challenging science experiences in early childhood is highlighted [8].

Reflecting increasing recognition of the ability of young children to engage in science learning [14,15,16] and the paramount significance of early science learning to later science outcomes [17], early childhood science education research as a distinct research field, has increased significantly over the past three decades [18]. Within the field, however, studies have focused predominantly on children aged three to six years with only a limited pool addressing science learning in the birth to three period specifically. Consequently, we have a strong, empirically based understanding of science experiences for children aged three to six years. In contrast, however, our understanding of science learning in infancy and toddlerhood, as it occurs for children from birth to three years, is limited.

Seeking to develop our understanding of a crucial yet largely unknown area of science education research, the current study aimed to review the empirical literature on science concept formation in the birth to three period (within the context of the wider early childhood science education literature). An empirical literature search was conducted over the period March 2020 to January 2021. Peer reviewed journal articles examining science concept formation in pre-school settings (birth to six years), from 1990 to date, were included. Findings illustrated that the empirical research on science concept formation in early childhood, has focused primarily on children aged three to six years (50 of 57 studies identified). A lack of empirical understanding of science concept formation as it occurs from birth to three was found.

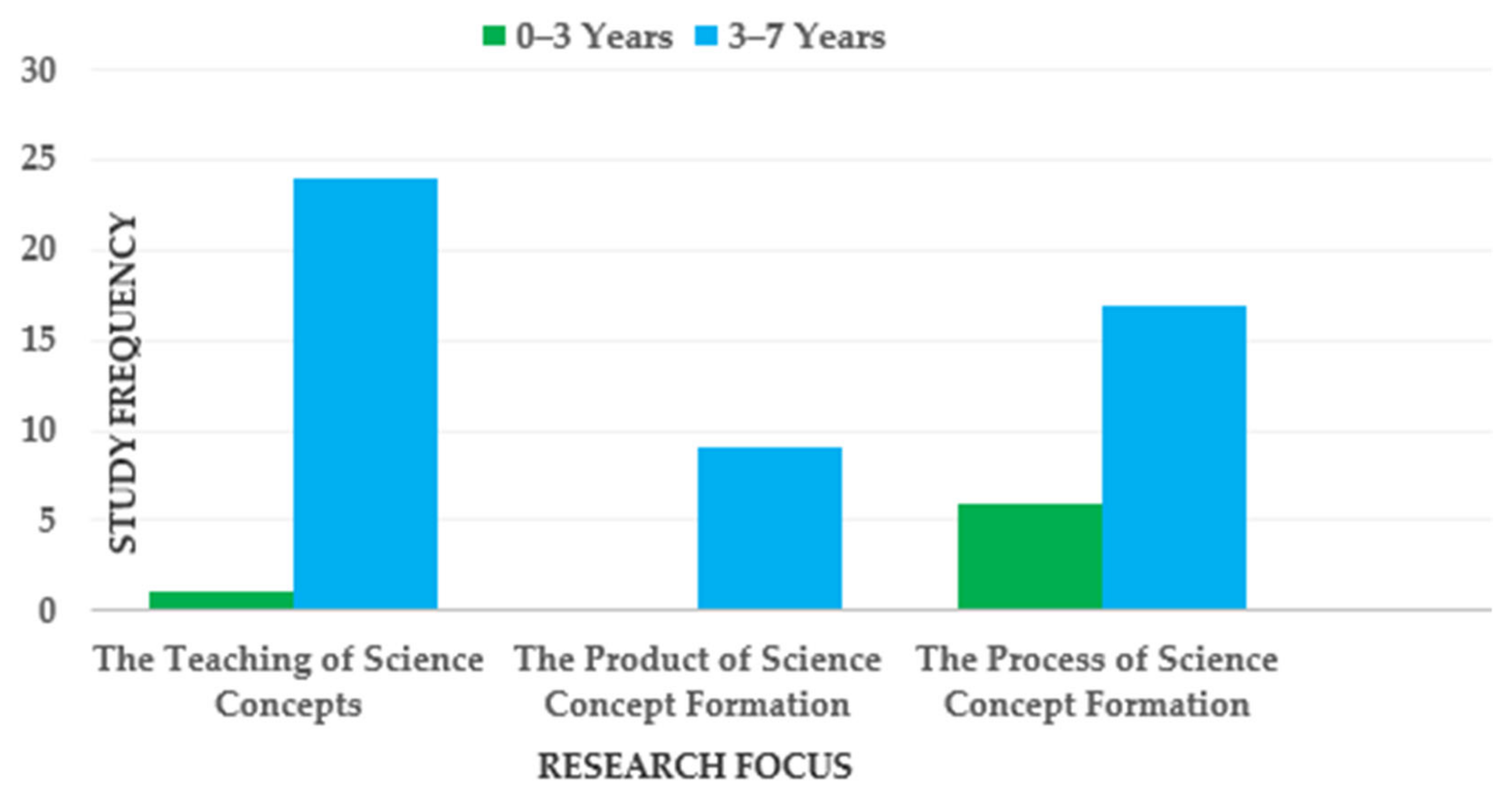

This paper presents the findings of the literature review. An overview of the methodological framework used to conduct the literature review is firstly presented and the categorisation process used to discuss the studies identified, is outlined. Overall findings of the review are then depicted graphically (Figure 1) with individual characteristics of the included studies presented in Tables 3–5. Findings of the review are then discussed in accordance with the identified categories (a detailed explanation of which is later provided). For each category, a brief summary of the literature on children aged three to six years is firstly provided. This is then followed by a more in-depth discussion of the literature on children from birth to three years.

Figure 1.

The Empirical Literature on Science Concept Formation in Early Childhood (Peer Reviewed International Journal Articles From 1990 to Date) by Research Focus and Participant Age.

2. Methodological Framework of the Literature Review

Reviewing to our knowledge, for the first time the empirical literature on science concept formation in the birth to three period specifically, this paper provides critical insight into our current understanding of science experiences of infants and toddlers. Gaps that exist in the literature regarding infant and toddlers’ thinking in science are highlighted and the eminent need for research emphasised. The following subsections describe the methodological framework used to conduct the review.

2.1. Methods

An empirical literature search was conducted over the period March 2020 to January 2021 using the following databases: A+ education, ERIC, ProQuest education journals, PsycINFO and SCOPUS. Peer reviewed journal articles (written in English), examining science concept formation in the early years setting from 1990 to date, were included. Only studies examining science concept formation in pre-school age children were included. This differed in accordance with the age of formal school commencement across countries. Studies examining science concept formation within the broader context of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) or Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics (STEAM), were excluded. Studies in which the overall research focus did not relate to concept formation and/or children’s thinking in science, were also excluded. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature search inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1 provides an understanding of the way in which studies were identified for inclusion in the literature review. The next subsection outlines the way in which the studies included, were categorised for the purpose of analysis.

2.2. Categorisation

The studies identified in the literature search were categorised into three groups according to the overall research focus; The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices) (Category 1), The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities) (Category 2) and The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development Over Time) (Category 3). A description of the categories and further sub-categorisation is now provided.

2.2.1. Category 1: The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices)

Studies examining science concept formation in relation to pedagogical practices were grouped together and categorised; Category 1: The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices). Studies were then further grouped into 2 sub-categories according to the more specific, research aim; studies exploring the effectiveness of specific teaching interventions/educational programs in relation to science concept formation (1A); studies exploring the effect of individual differences amongst educators in relation to science concept formation (1B).

2.2.2. Category 2: The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities)

Studies that explored children’s individual conceptual science understandings were grouped together and categorised; Category 2: The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities). Studies were then further grouped into 2 sub-categories according to the more specific, research aim; studies exploring pre-school age children’s conceptual understandings of science concepts (2A); studies exploring the age (biologically) that children begin developing scientific reasoning skills (2B).

2.2.3. Category 3: The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time)

Studies that focused on examining the process of concept formation were grouped together and categorised; Category 3: The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time). Studies were then further grouped into 2 sub-categories according to the more specific, research aim; studies seeking to explore and understand how children are developing their understandings of science concepts (3A); studies seeking to explore and understand the role the teacher plays in creating conditions for children developing conceptual understandings in science (3B).

Studies in Group 3A examine the process of science concept formation (how children are developing an understanding of science concepts over time). These studies differ to studies in Group 2A where the focus of research is on identifying children’s conceptual understandings and/or ability to engage in science learning at a specific point in time.

Studies in Group 3B explore the way in which elements of the teachers’ role influence the process of concept formation (how early childhood teachers create the conditions for the formation of science concepts). These studies therefore differ to studies in Category 1 (The Teaching of Science Concepts) where the focus of research is on examining the efficacy of specific teaching methods, interventions or instructional strategies in promoting scientific understanding.

Table 2 provides an overview of the categorisation. The frequency of papers by category and age of participants is also presented.

Table 2.

Studies regarding science concept formation in early childhood published from 1990 to date by research aim and participant age.

Table 2 presents the frequency of studies included in the review by categorisation according to the research focus and research aim. Table 2 shows that of the 57 studies identified for inclusion in the review, 50 related to children aged three to six years and 7 related to children in the birth to three period. Table 2 also illustrates that 25 studies examined science concept formation in relation to the teaching of science concepts (Category 1) of which 1 related to children in the birth to three period; 9 studies examined science concept formation in relation to the product of science concept formation (conceptual understandings/demonstrated capabilities) (Category 2), all of which involved children aged three to six years; 23 studies examined the process of science concept formation (Category 3), 6 of which related to children in the birth to three period.

3. Findings and Discussion

3.1. Individual Study Characteristics

A summary of the main characteristics of the studies included in the review are now presented in accordance with the categories discussed. Three different tables are presented. The first table (Table 3) summarises the main characteristics of studies in Category 1 (The Teaching of Science Concepts; Pedagogical Practices). The second table (Table 4) summarises the main characteristics of studies in Category 2 (The Product of Science Concept Formation; Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities). The third table (Table 5) summarises the main characteristics of studies in Category 3 (The Process of Science Concept Formation; Development over Time). Within each table, the studies are presented in alphabetical order of the author’s names.

Table 3.

Characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the teaching of science concepts (pedagogical practices).

Table 4.

Characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the product of science concept formation (conceptual understandings/demonstrated capabilities).

Table 5.

Characteristics of Empirical Studies Examining Science Concept Formation in The Early Years (Birth to Six Years) in Relation to The Process of Concept Formation (development over time).

Table 3 presented the characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the teaching of science concepts (pedagogical practices). Table 4 now follows, presenting characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the product of science concept formation (conceptual understandings/demonstrated capabilities).

Table 4 presented the characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the product of science concept formation (conceptual understandings/demonstrated capabilities). Table 5 now follows, presenting characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the process of concept formation (development over time).

Table 5 presented the characteristics of empirical studies examining science concept formation in the early years (birth to six years) in relation to the process of concept formation (development over time).

Collectively, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 provide an overview of the general characteristics of studies which have examined science concept formation in the early years. A summary of the overall findings and ways in which science concept formation has been examined, from the studies included in the review is now provided.

3.2. Findings

The findings from the literature review of published empirical works on science concept formation in early childhood are illustrated through a bar graph of categories (Figure 1), followed by a discussion of what was determined through an analysis using the categories discussed; 1. The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices); 2. The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities), and 3. The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time).

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the empirical literature on science concept formation in early childhood by research focus and participant age. The extent with which research has involved children aged three to six years (in contrast to children in the birth to three period) is highlighted. 50 studies involved children aged three to six years, 7 studies related to children in the birth to three period. A limited empirical understanding of science experiences of children in the birth to three period (in contrast to that of older pre-school age children) is highlighted.

A discussion of the studies identified in the review is now provided by category. Having been previously reviewed the literature on children aged three to six years are firstly summarised and a more detailed discussion of studies involving children aged birth to three then given.

3.2.1. Category 1. The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices)

At the time of review, 25 of the 57 studies identified, examined science concept formation in the context of its relation to the teaching of science concepts (pedagogical practices); 24 related to children aged three to six years and 1 to children in the birth to three period.

The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices): Three to Six Years

As earlier discussed, studies examining science concept formation in relation to pedagogical practices were further grouped into two sub-categories according to the more specific, research aim; studies exploring the effectiveness of specific teaching interventions/educational programs in relation to science concept formation (1A); studies exploring the effect of individual differences amongst teachers in relation to science concept formation (1B). Findings are now discussed in accordance with these sub-categories; 1A: Teaching Interventions/Programs; 1B: Individual Differences across Early Years Teachers.

- 1A.

- The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices) (three to six years): Teaching Interventions/Programs

The majority of studies examining science concept formation in relation to pedagogical practices, explored the extent with which specific teaching methods and/or instructional strategies commonly used within the early childhood classroom/centre, facilitated children’s learning of science. Teaching approaches examined included the combination of storytelling and drama [37], pictorial story reading [24], the use of electronic prompts built into touchscreen books [34] and the necessity of “physicality” (actual and active touch of concrete material) as a pre-requisite for science experimentation [38]. A cluster of studies have examined the relation between science concept formation and more broader teaching approaches including the use of responsive teaching and explicit instruction [23], narrative and paradigmatic modes of explanation [29] and inquiry based didactic methods [19]. The relation between teaching approaches differing theoretically, and science learning has also been explored including the effect of a socio-cognitive strategy on enhancing children in constructing a “precursor model” for the concept of friction [31] and light [33], Piagetian strategies [32], Cultural Historical Activity Theory [26] and a constructivist pedagogy [30]. Providing insight into the effects of different instructional strategies on science learning in early childhood specifically, the studies identified are pivotal in assisting early childhood teachers to develop appropriate strategies for teaching sciences [37].

Empirical research examining the efficacy of teaching interventions/educational programs is fundamental in providing a strong evidence base upon which emerging early childhood science practices and curricular reforms can be built [38]. A small group of studies identified in the current review examined the efficacy of specific teaching interventions/programs, in promoting scientific understanding, within the early childhood setting. Studies identified examined interventions in relation to the development of conceptual understandings of astronomical concepts [20,36], the construction of “pre-cursor” models to support scientific learning [25], the implementation of interventions designed to increase children’s voluntary exploration of science centres during free choice play [28] and the combining of a museum and classroom intervention project on science learning in low-income children [35]. Positive outcomes in relation to the development of science concepts (in children aged 3–6 years) across all the identified studies was noted. That only 4 studies identified, examined the efficacy of specific teaching interventions is perhaps reflective of concerns within the wider literature, where a lack of outcome studies to support the implementation of innovative early childhood science curricular has been highlighted [76]. The provision of a strong evidence base is fundamental to the delivery of effective programs and best practice. The need for empirical work examining the efficacy of novel curricular and innovative classroom practices for science in early childhood is highlighted.

- 1B.

- The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices) (three to six years): Individual Differences Across Early Years Teachers

A group of studies identified explored individual differences amongst teachers in relation to children’s science learning experiences. Fleer [39] found individual teacher “philosophy” about how young children learn, to be a significant contributing factor to learning in science. Similarly, the level of individual teacher science “awareness” in relation to opportunities available in the environment, was found to be a contributing factor to science learning [42]. Domain specific self-efficacy has also been explored with an association found between teacher self-efficacy for science and the frequency of which children are engaged in science instruction [40].

Highlighting ways in which science opportunities provided in early childhood classrooms/centres can be enhanced (at the level of teacher education and the context of the everyday classroom) the studies on individual differences amongst teachers, have significant implications for teaching practices and child outcomes [40]. For instance, the association found between a lack of self-efficacy and time children are engaged in science instruction [40], supports the need for pre-service and in-service education programs to provide teachers with content and practices for science rather than focusing exclusively on literacy [40]. However, Fleer [39] draws caution to research in which a lack confidence and competence in teaching science is emphasised, suggesting that there is a tendency of such research to “blame the victim” whilst providing little analysis or insight into the reason. Instead, Fleer [39] argues that emphasis should be placed on individual teacher philosophy as this was found to have more of a difference to children’s scientific learning than both teacher confidence in science teaching or science knowledge.

The Teaching of Science Concepts (Pedagogical Practices): Birth to Three

The literature review identified 1 study [27] in which science concept formation was examined in relation to pedagogical practices, in children aged birth to three years. This study is now discussed.

Research conducted by Lloyd et al. [27] represents the only study to empirically examine the teaching of science concepts (pedagogical practices) in relation to science concept formation of children in the birth to three period specifically. Seeking to bridge science learning across institutional practices of home and day care, Lloyd et al. [27] conducted an exploratory study of a “stay and play” service. A programme of activities aimed at encouraging parents’ confidence in their own ability was delivered to support emergent scientific thinking. Findings demonstrated that the program generated children’s engagement and interest and in addition, enhanced parental and practitioner confidence in their ability to promote young children’s natural curiosity at home and in early childhood provision. The study found that parental interaction enhanced the children’s learning at least as much, if not more than practitioner interventions. Based on this finding Lloyd et al. [27] highlight the significance of “familiar” adults in mediating young children’s enjoyment and encouraging natural curiosity.

The significant role of an adult in mediating science learning experiences in infancy specifically, has been highlighted both in the context of the family home [66,67,68] and the educational setting [72]. As a key asset of a rich science learning environment in infancy [72], the significant role of an adult in mediating science learning experience in infancy specifically, illustrates a crucial difference in the science learning of infants in comparison to older pre-school age children. To Fragkiadaki et al. [72] (p. 19), “the introduction of scientific concepts in the infant environment differs from a quick introduction or as something to be discovered without an adult guide”. That an assumption that teaching and learning practices used with older children can be used with infants is highlighted within the literature [77], underscores the imperative need for empirical research examining science learning in infancy period specifically.

3.2.2. Category 2: The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities)

A substantial proportion of empirical research in science education (in general) has centred around identifying children’s individual conceptual understandings at specific points in time. Most commonly, studies have used experimental clinical methods to elicit children’s thinking in order to determine their specific conceptual understandings. At the time of review, 9 of the 57 studies identified, examined science concept formation in the context of its relation to conceptual understandings; all studies related to children aged three to six years.

The Product of Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities): Three to Six Years

Exploration of children’s conceptual understandings in relation to specific concepts identified in the current review included nature of science [43], ecological understandings [44], fossils [45], and electricity [50]. Studies have also examined children’s conceptions and misconceptions [49] their ability to construct operational definitions in magnetism [46] and how and when scientific reasoning skills emerge in the early childhood [51,52]. Collectively this area of research provides us with a strong empirical insight into the conceptual understandings of children aged three to six years in relation to scientific phenomena. It is, however, important to note that reliance on these studies has been cautioned in relation to the (arguably) questionable validity of study methods; many approaches used to determine how children think about science concepts have been deemed suitable to use with young children without any questioning of their reliability when applied to this age group specifically [78]. The extent with which examining science concept formation in the early childhood is associated with methodological challenges are highlighted later in the paper.

The Product of Science Concept Formation (Conceptual Understandings/Demonstrated Capabilities): Birth to Three

No individual study examining conceptual understandings of scientific phenomena in children aged birth to three specifically was identified in the review. However, insight into a more cognitive perspective of science learning in infancy can be gained through discussion of the broader Cognitive literature. In contrast to the Piagetian view of infants as “irrational and pre-causal”, a branch of cognitive research, conceptualises infants as “little scientists” or “theorists,” actively attempting to build theories about the world [79]. Research centres around demonstrating the extent with which young children “think like scientists”, testing hypothesis, making causal inferences and learning from informal experimentation [80]. In a 2011 review, Keil [81] concluded that young children share the cognitive “skills” of scientists, detecting correlations between seemingly unrelated phenomena, inferring causation, uncovering explanatory mechanisms and then sharing and building upon this knowledge with others. Similarly, in an overview of empirical studies in science in infancy, Gopnik [82] argues that infants learn about the world in the same way scientists do, analysing statistical data patterns, conducting experiments, and learning from the data and others. Using findings from an observational study Forman [47] argues that infants think like scientist because they use the same methods of, e.g., sensing the problem, and testing first. The small experiments, inventions, strategies, and pauses in young children’s play captured in observations of toddlers’ play illustrate a legitimate form of scientific thinking [47].

Painting an increasingly positive picture of young children as “active learners” [83] the (cognitive) research discussed, provides valuable insight into the cognitive processes associated with science learning in infancy. However, concerns with the cognitive premise on which the “little scientist” model is based have been highlighted. Nelson [84] (p. 6) argues that what the child brings to any conceptual domain is a built-in structure, fails to acknowledge outside influences on development; it is “imperviousness to influences on basic cognitive processes or cognitive growth from outside the mind…”. Consequently, the complexity of cognitive development, the significance of knowledge in the social and cultural world surrounding the child, are obscured [84].

3.2.3. Category 3: The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time)

In contrast to research in which the primary focus has been to identify conceptual understandings, a number of studies identified examined how young children develop their understandings of science concepts; the “process” of science concept formation. At the time of review, 23 of the 57 studies identified, examined the process of science concept formation; 17 studies related to children aged three to six years and 6 to children in the birth to three period.

The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time): Three to Six Years

Seeking to explore how young children form conceptual understandings in an everyday context, a number of studies have explored the collaborative nature of science learning [56,57,58,60,62,69,70] findings of which highlight the importance of collaborative experiences. Other studies have explored the dialectic interrelations between intellect, affect, and action during science experiences [61], the emotional nature of scientific learning [55] and the reciprocity between everyday thinking and scientific thinking during playful encounters [54]. The differing ways in which children represent natural phenomena have also been explored [53,59]. The way in which elements of the teachers’ role, influence the process of concept formation, has been explored including sustained and shared conversations between children and teachers [71], intersubjective communication (intersubjectivity) [73], contextual and conceptual intersubjectivity [64], conceptually orientated teacher–child interactions [74] and verbal interaction between a child and teacher [75].

Examining the process of science concept formation, studies in this category have primarily been conducted within a Socio-Cultural (SC)/Cultural-Historical (CH) theoretical framework. Focusing on the contexts in which children develop socio-culturally relevant activities, and the interactions with others that support and guide them [85], SC/CH research is suggested to provide a powerful and authentic approach to researching young children’s thinking [6]. That as suggested by Robbins [85], individual thinking does not occur in a “vacuum” separate from activities in which people engage, highlights the value of this group of studies in relation to our understanding of science concept formation in the early years.

The Process of Science Concept Formation (Development over Time): Birth to Three

Representing the largest area of research examining science concept formation in the infancy period specifically, six of the seven studies identified in the review explored “how” children (as infants) are forming science concepts; the process of concept formation. Adopting a Cultural- Historical approach, Sikder and Fleer [66,67,68], examined infant-toddler’s development of science concept formation within the family context. Based on Vygotsky’s theory of concept formation, Sikder and Fleer [67] identified and categorised what they termed “small science”, the toddlers’ engagement and narration accompanying the small moments of their “everyday activities”. They propose that “small science” can help explain how the everyday experiences of young children lay the foundation for the development of concrete “scientific” concepts. In a later paper, Sikder and Fleer [68] examined how these small science concepts become “ideal forms” from “real forms” in everyday life during the infant–toddler age period; findings indicated a conscious collaboration between parents and infants was key for developing small science concepts from rudimentary to mature form.

Providing a similarly cultural-historical examination of science concept formation, a large programmatic study (Fleers Conceptual PlayLab (CPL) in Melbourne, Australia) examined science concept formation in infancy in the context of an educational setting [72]. Using a model of intentional teaching called a Conceptual PlayWorld (CPW) [56], as an Educational Experiment, Fragkiadaki et al. [72], examined how infants in play-based settings, develop scientific understandings about their everyday world. Using visual methods and concepts from Cultural Historical Theory (CHT), 4 key elements for introducing science concepts in infants’ everyday educational reality were identified: (a) making dialectic interrelations between the everyday concept and the science concept, (b) consistently using a science language, (c) using appropriate analogies, and (d) using early forms of a scientific method.

Conducted within a similar cultural-historical framework Larsson [65], explored preschool children’s opportunities for learning about friction focusing on four children and their everyday experiences within a Swedish preschool setting. Using the visual method of “shadowing” (direct observation using a video camera with a focus on a particular person), Larsson [65] found that during everyday situations and during play, a range of activities occur that place children in contact with the phenomenon of friction (e.g., when they shuffle, slide, or push). Children encounter the phenomenon of friction in many everyday situations, without reacting or reflecting upon it [65]. Larsson [65] suggests that such findings highlight the extent with which everyday play situations can be used by teachers to become more knowledgeable about children’s current understandings of the phenomenon and ways of directing their attention toward understanding of friction in a more explicit manner, such as by inspiring children to new forms of play where the phenomenon of friction is prominent.

In similarity to Larsson [65], Klaa and Ohman [63] examined how children, as infants, encounter the phenomena of friction. Focusing on the way in which infants form science concepts through their actions in nature, Klaa and Ohman [63] provide insight into how the process of “meaning making” can be examined in infancy in the context of science. According to Klaa and Ohman [63], the investigation of meaning making should not be restricted to science concepts; analysis must relate to encounters with nature as one aspect among several in young children’s lives. Accordingly, Klaa and Ohman [63] present and illustrate an approach that allows for the analysis of toddlers’ meaning making when they physically encounter and experience nature in everyday practice. Based on Dewey’s philosophy of Pragmatism, Klaa and Ohman [63] argue that their ‘pragmatic action-oriented’ perspective of learning can facilitate the analysis of toddlers’ meaning making processes in early childhood education settings, contributing to a deeper understanding of the basic foundation for children’s meaning making of nature.

Overall, there exists a plethora of methodological challenges associated with research involving children in the infancy period. The studies discussed provide valuable insight into ways in which the complexity of young children’s science learning has and can be captured. The use of visual methodologies and Practical Epistemological Analysis, to gain insight into the child’s everyday context were highlighted in the review and offer promising avenues for future exploration. In addition, this group of studies highlight the extent with which research into science concept formation in infancy specifically, has centred around examining the “process” of concept formation from a predominantly socio-cultural/cultural historical perspective. In contrast, the literature on older preschool age children has tended to adopt a constructivist approach which traditionally, has examined a child’s demonstrated understanding of a particular science concept at a particular point in time; the “product” of concept formation. This difference is perhaps reflective of methodological challenges inherent in research with very young children.

4. Conclusions

Within the context of early childhood science education, we have a strong, empirically based understanding of science experiences for children aged three to six years. In contrast, our understanding of science learning as it occurs for children from birth to three, is extremely limited. We know very little about how and in what way children as infants and toddlers form conceptual understandings in science. Seeking to gain insight into current empirical understandings of science concept formation in the infancy–toddlerhood period, a review of the literature on early childhood science education (birth to six years) was conducted. The literature review focused specifically (and for the first time) on children in the birth to three period.

Findings of the review illustrate a clear gap in the literature regarding science concept formation in the birth to three period; very little is known about infant and toddlers’ thinking in science when considered in the context of birth to six years. Infants can and do engage in science [7] and the assumption that a particular developmental level must be reached before children can be taught science concepts has been challenged [72]. However, only a handful of empirical papers have examined science concept formation in the infancy–toddlerhood period specifically; we do not know enough about how science and scientific thinking can and does begin from birth [72]. The eminent need for empirical research to address this gap is highlighted by this review.

The lack of empirical research examining science concept formation in the birth to three period, identified in this review, can in part, be attributed to the methodological challenges inherent in research involving very young children. Determining how for example, the thinking of an infant with limited verbal skills can be documented, presents the researcher with a profound challenge. The fact that historically, infancy has been viewed as a period of helplessness may also explain the lack of empirical research identified; infants traditionally, have not been conceptualized as active, capable, “scientists”. That infancy is a period in which there is no formal schooling, further complicates the construction of an empirical basis.

5. Science Concept Formation in the Birth to Three Period: Key Points from the Literature

In completing the review, a number of key points regarding the empirical literature on science concept formation in infancy and toddlerhood, were identified.

- Studies examining science concept formation in the birth to three period specifically, have focused primarily on exploring the process of concept formation; 6 of the 7 studies identified examined how young children develop their understandings of science concepts in an everyday context. This is in contrast to the literature on older pre-school age children (three to six years), where the tendency of research has been to focus on the relation between science concept formation and pedagogical practices; 24 of 50 studies (examining science concept formation in children aged three to six years) examined the relationships between teaching practices and children’s conceptual development.

- Studies examining science concept formation in birth to three period, have tended to draw upon socio-cultural/cultural historical theory; 5 of the 7 studies identified, adopted a SC/CH theoretical framework. From a SC/CH perspective, cognitive development is conceptualised as a process whereby people move “through” understanding as opposed to towards it [86]. Concept formation is therefore, conceptualised as a dynamic process that must be examined as it occurs within and across differing contexts [54]. Research examining science learning in the birth to three period specifically, has focused on the “process” of concept formation. Within the broader Early Years Science Education Research (EYSER) literature, the tendency of research, to adopt a constructivist approach has been highlighted [6]. In contrast to SC/CH research, research adopting a constructivist approach has historically, examined children’s demonstrated understandings of a particular science concept at a particular point in time. Thus, in contrast to the literature on science concept formation in infancy–toddlerhood, the literature within EYSER in general, has tended to examine the “product” of concept formation.

The greater emphasis placed on the process (as opposed product) of concept formation, seen in the literature on science in the infancy period, is, perhaps reflective of the difficulties inherent in using clinical methods to ascertain conceptual understandings of infants and toddlers (seen in broader constructivist approaches). Traditionally, EYSER research adopting a constructivist approach, has examined children’s mental representations and understanding of science phenomena [61], findings are therefore based on children’s elicited responses, expressions of their thinking. Such methods, however, rely heavily on a certain level of cognitive awareness/verbal skills. The inherent challenges this presents when research involves very young children is highlighted.

In summary, the overall findings of the review provide clear evidence that a gap exists in the literature regarding infant and toddlers’ thinking in science, very little is known when considered in the context of birth to six years. Urgent research attention is needed to take forward and to provide education systems with more evidence of infant and toddler thinking in science and what kinds of pedagogical approaches can amplify science thinking in the first period of children’s lives. Without research within this early period, we do not have a sense of the continuum of science learning, under what conditions, what kind of methods are needed to study this period, or indeed how teachers can plan for infant-toddler development of science concept formation. This review paper gives the possibility to take stock of the gaps, and to point to new directions in science education research.

Author Contributions

The scope, focus and refinement of the review was conceptualised by M.F., G.F. and P.R., with modeling and mentoring of G.O., who synthesized and prepared tables and accompanying text. Final directions of the narrative and conclusion were jointly undertaken by all authors, but prepared by G.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council [FL180100161].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the research assistance of Sue March and the support of the Conceptual PlayLab PhD community at Monash University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Murray, J. Routes to STEM: Nurturing Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics in early years education. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2019, 27, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenberg, J.M.; Geiken, R. Supporting Young Children’s Spatial Understanding: Examining Toddlers’ Experiences with Contents and Containers. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 49, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, T.J.; Odell, M.R.L. Engaging students in STEM education. Sci. Educ. Int. 2014, 25, 246–258. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, S.; De Bortoli, L.; Underwood, C. PISA 2015: A First Look at Australia’s Results. 2016. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/21/ (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Eshach, H.; Fried, M.N. Should Science be Taught in Early Childhood? J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2005, 14, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M.; Robbins, J. “Hit and Run Research” with “Hit and Miss” Results in Early Childhood Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2003, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M.; Fragkiadaki, G.; Rai, P. STEM begins in infancy: Conceptual PlayWorlds to support new practices for professionals and families. Int. J. Birth Parent Educ. 2020, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, T.; McGuigan, L. An updated perspective on emergent science. Early Child Dev. Care 2016, 187, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellopoulou, A.; Papandreou, M. Investigating the teacher’s roles for the integration of science learning and play in the kindergarten. Educ. J. Univ. Patras UNESCO Chair 2019, 6, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saçkes, M.; Trundle, K.C.; Bell, R.L.; O’Connell, A.A. The influence of early science experience in kindergarten on children’s immediate and later science achievement: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2010, 48, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, E.; Lieberman-Betz, R.G.; Vail, C.O. Attitudes and Beliefs of Prekindergarten Teachers Toward Teaching Science to Young Children. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 45, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Kambouri-Danos, M. Substantive conceptual development in preschool science: Contemporary issues and future directions. Early Child Dev. Care 2017, 187, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallery, M.; Psillos, D.; Tselfes, V. Typical Didactical Activities in the Greek Early-Years Science Classroom: Do they promote science learning? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshach, H. Science Literacy in Primary Schools and Pre-Schools; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- French, L. Science as the center of a coherent, integrated early childhood curriculum. Early Child. Res. Q. 2004, 19, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzicopoulos, P.; Patrick, H. Reading Picture Books and Learning Science: Engaging Young Children with Informational Text. Theory Pract. 2011, 50, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Childhood STEM Working Group. Early STEM Matters: Providing High-Quality STEM Experiences for All Young Learners: A Policy Report by the Early Childhood STEM Working Group. 2017. Available online: http://d3lwefg3pyezlb.cloudfront.net/docs/Early_STEM_Matters_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Ravanis, K. Early Childhood Science Education: State of The Art and Perspectives. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, 284–288. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/early-childhood-science-education-state-art/docview/2343739757/se-2?accountid=12528 (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Dejonckheere, P.; Van de Keere, K.; De Wit, N.; Vervaet, S. Exploring the classroom: Teaching science in early childhood. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2016, 8, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, M.; Seker, F. The Effect of Science Activities on Concept Acquisition of Age 5-6 Children Groups. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 3011–3024. [Google Scholar]

- Hadzigeorgiou, Y. A Study of the Development of the Concept of Mechanical Stability in Preschool Children. Res. Sci. Educ. 2002, 32, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannust, T.; Kikas, E. Children’s knowledge of astronomy and its change in the course of learning. Early Child. Res. Q. 2007, 22, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Diamond, K.E. Two approaches to teaching young children science concepts, vocabulary, and scientific problem-solving skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannakis, M.; Nirgianaki, G.-M.; Papadakis, S. Teaching Magnetism to Preschool Children: The Effectiveness of Picture Story Reading. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 46, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambouri-Danos, M.; Ravanis, K.; Jameau, A.; Boilevin, J.-M. Precursor Models and Early Years Science Learning: A Case Study Related to the Water State Changes. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2019, 47, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokouri, E.; Plakitsi, K. A CHAT Approach of Light and Colors in Science Teaching for the Early Grades. World J. Educ. 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E.; Edmonds, C.; Downs, C.; Crutchley, R.; Paffard, F. Talking everyday science to very young children: A study involving parents and practitioners within an early childhood centre. Early Child Dev. Care 2017, 187, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayfeld, I.; Brenneman, K.; Gelman, R. Science in the Classroom: Finding a Balance between Autonomous Exploration and Teacher-Led Instruction in Preschool Settings. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.M. Narrative and Paradigmatic Explanations in Preschool Science Discourse. Discourse Process. 2009, 46, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanis, K. The discovery of elementary magnetic properties in preschool age. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 1994, 2, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanis, K.; Koliopoulos, D.; Hadzigeorgiou, Y. What factors does friction depend on? A socio-cognitive teaching intervention with young children. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2004, 26, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanis, K.; Pantidos, P. Sciences Activities in Preschool Education: Effective and Ineffective Activities in a Piagetian Theoretical Framework for Research and Development. Int. J. Learn. Annu. Rev. 2008, 15, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanis, K.; Christidou, V.; Hatzinikita, V. Enhancing Conceptual Change in Preschool Children’s Representations of Light: A Sociocognitive Approach. Res. Sci. Educ. 2013, 43, 2257–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, G.A.; Ganea, P.A. Are Prompts Provided by Electronic Books as Effective for Teaching Preschoolers a Biological Concept as Those Provided by Adults? Early Educ. Dev. 2016, 27, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, H.R.; Rappolt-Schlichtmann, G.; Zanger, V.V. Children’s learning about water in a museum and in the classroom. Early Child. Res. Q. 2004, 19, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanides, N.; Gritsi, F.; Kampeza, M.; Ravanis, K. Changing Pre-school Children’s Conceptions of the Day/Night Cycle Changer les Conceptions d’Enfants d’Age Prescolaire sur le Phenomene du Cercle ’Jour-Nuit’ Cambiar las Concepciones de los Ninos Preescolares en el Ciclo Dia/Noche. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2000, 8, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walan, S.; Enochsson, A.-B. The potential of using a combination of storytelling and drama, when teaching young children science. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, Z.C.; Loizou, E.; Papaevripidou, M. Is physicality an important aspect of learning through science experimentation among kindergarten students? Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M. Supporting Scientific Conceptual Consciousness or Learning in ‘a Roundabout Way’ in Play-based Contexts. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H.K.; Pierce, S.J.; Lee, K.; Van Egeren, L.A. Early Childhood Educators’ Self-Efficacy in Science, Math, and Literacy Instruction and Science Practice in the Classroom. Early Educ. Dev. 2018, 29, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M.; Gomes, J.; March, S. Science Learning Affordances in Preschool Environments. Australas. J. Early Child. 2014, 39, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.; Fleer, M. Is Science Really Everywhere? Teachers’ Perspectives on Science Learning Possibilities in the Preschool Environment. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 50, 1961–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerson, V.L.; Gayle, A.B.; Buck, G.A.; Donnelly, L.A.; Nargund-Joshi, V.; Weiland, I.S. The Importance of Teaching and Learning Nature of Science in the Early Childhood Years. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2011, 20, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Early understandings of simple food chains: A learning progression for the preschool years. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 1485–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgerding, L.A.; Raven, S. Children’s ideas about fossils and foundational concepts related to fossils. Sci. Educ. 2018, 102, 414–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.; Spanoudes, G.; Raftopoulos, A.; Natsopoulos, D. Pre-schoolers’ construction of operational definitions in magnetism. J. Emergent Sci. 2013, 5, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, G.E. When 2-year-olds and 3-year-olds think like scientists. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2010, 12. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ910913.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Krnel, D.; Watson, R.; Glažar, S.A. The development of the concept of ‘matter’: A cross-age study of how children describe materials. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolleck, L.; Hershberger, V. Playing with Science: An Investigation of Young Children’s Science Conceptions and Misconceptions. Curr. Issues Educ. 2011, 14. Available online: https://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/324 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Solomonidou, C.; Kakana, D.M. Preschool children’s conceptions about the electric current and the functioning of electric appliances. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 8, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekny, J.; Maehler, C. Scientific reasoning in early and middle childhood: The development of domain-general evidence evaluation, experimentation, and hypothesis generation skills. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 31, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekny, J.; Grube, D.; Maehler, C. The Development of Experimentation and Evidence Evaluation Skills at Preschool Age. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 36, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidou, V.; Hatzinikita, V. Preschool Children’s Explanations of Plant Growth and Rain Formation: A Comparative Analysis. Res. Sci. Educ. 2005, 36, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M. Understanding the Dialectical Relations between Everyday Concepts and Scientific Concepts Within Play-Based Programs. Res. Sci. Educ. 2009, 39, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M. Affective Imagination in Science Education: Determining the Emotional Nature of Scientific and Technological Learning of Young Children. Res. Sci. Educ. 2013, 43, 2085–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M. Scientific Playworlds: A Model of Teaching Science in Play-Based Settings. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Ravanis, K. Mapping the interactions between young children while approaching the natural phenomenon of clouds creation. Educ. J. Univ. Patras UNESCO Chair 2014, 1, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Ravanis, K. Genetic Research Methodology Meets Early Childhood Science Education Research: A Cultural-Historical Study of Child’s Scientific Thinking Development. Cult. Psychol. 2016, 12, 310–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Ravanis, K. Preschool Children’s mental representations of clouds. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2015, 14, 267–274. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/preschool-children-s-mental-representations/docview/2343755233/se-2?accountid=12528 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Fleer, M.; Ravanis, K. A Cultural-Historical Study of the Development of Children’s Scientific Thinking about Clouds in Everyday Life. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 1523–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Fleer, M.; Ravanis, K. Understanding the complexity of young children’s learning and development in science: A twofold methodological model building on constructivist and cultural-historical strengths. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2021, 28, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frejd, J. When Children Do Science: Collaborative Interactions in Preschoolers’ Discussions About Animal Diversity. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaar, S.; Öhman, J. Action with friction: A transactional approach to toddlers’ physical meaning making of natural phenomena and processes in preschool. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 20, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J. Contextual and Conceptual Intersubjectivity and Opportunities for Emergent Science Knowledge about Sound. Int. J. Early Child. 2013, 45, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Larsson, J. Children’s Encounters with Friction as understood as a Phenomenon of Emerging Science and as “Opportunities for Learning”. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2013, 27, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S. Social situation of development: Parents perspectives on infants-toddlers’ concept formation in science. Early Child Dev. Care 2015, 185, 1658–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.; Fleer, M. Small Science: Infants and Toddlers Experiencing Science in Everyday Family Life. Res. Sci. Educ. 2015, 45, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.; Fleer, M. The relations between ideal and real forms of small science: Conscious collaboration among parents and infants–toddlers. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 13, 865–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siry, C.; Ziegler, G.; Max, C. “Doing science” through discourse-in-interaction: Young children’s science investigations at the early childhood level. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siry, C.; Max, C. The Collective Construction of a Science Unit: Framing Curricula as Emergent from Kindergarteners’ Wonderings. Sci. Educ. 2013, 97, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adbo, K.; Carulla, C.V. Learning about Science in Preschool: Play-Based Activities to Support Children’s Understanding of Chemistry Concepts. Int. J. Early Child. 2020, 52, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, G.; Fleer, M.; Rai, P. The hidden and invisible: Science concepts formation in early infancy. Rise 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fridberg, M.; Jonsson, A.; Redfors, A.; Thulin, S. Teaching chemistry and physics in preschool: A matter of establishing intersubjectivity. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 2542–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havu-Nuutinen, S. Examining young children’s conceptual change process in floating and sinking from a social constructivist perspective. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramling, N.; Samuelsson, I.P. “It is Floating ‘Cause there is a Hole’”: A young child’s experience of natural science. Early Years 2001, 21, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, K. Children’s Understanding of Scientific Inquiry: Their Conceptualization of Uncertainty in Investigations of Their Own Design. Cogn. Instr. 2004, 22, 219–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj-Blatchford, J. Emergent Science and Technology in the Early Years. In Proceedings of the XXIII World Congress of OMEP, Santiago, Chile, 31 July–4 August 2001; Available online: http://www.327matters.org/docs/omepabs.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Fleer, M.; Pramling, N. Learning Science in Everyday Life—A Cultural-Historical Framework. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 11, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopnik, A.; Glymour, C.; Sobel, D.M.; Schulz, L.E.; Kushnir, T.; Danks, D. A Theory of Causal Learning in Children: Causal Maps and Bayes Nets. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopnik, A.; Wellman, H.M. Reconstructing constructivism: Causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, F.C. Science Starts Early. Science 2011, 331, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopnik, A.; Zhen, Y.; Aardema, M.L.; Medina, E.M.; Schumer, M.; Andolfatto, P. Scientific Thinking in Young Children: Theoretical Advances, Empirical Research, and Policy Implications. Science 2012, 337, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.L.; Campione, J.C. The development of science learning abilities in children. In Growing up with Science; Harnquvist, K., Burgen, A., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, K. Young minds in social worlds: Experience, meaning, and memory. Choice Rev. Online 2007, 45, 45–0558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J. ‘Brown Paper Packages’? A Sociocultural Perspective on Young Children’s Ideas in Science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2005, 35, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B. Cognition as a collaborative process. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Cognition, Perception and Language; Damon, W., Kuhn, D., Siegler, R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).