Abstract

Tax incentives play a crucial role in enhancing firm dynamism and aiding a nation in becoming a significant trade power. Drawing on data from the Annual Survey of Industrial Firms Database and the Chinese Customs Database for the period 2010 to 2013, this study employs a difference-in-differences approach to assess the impact of China’s transition from a business tax to a value-added tax (RBTVAT) on the export diversification of manufacturing firms. The findings indicate that the tax reform significantly decreases the number of export categories, increases export value, and elevates the export unit price for manufacturing firms. Specifically, by promoting specialized production and encouraging the manufacture of products with higher export tax rebate rates, the reforms have led firms to narrow their range of export categories. This effect is particularly pronounced among firms experiencing higher financing constraints, lower profitability, weaker innovation capabilities, and larger size. Furthermore, a consistent negative impact is observed for both state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. These results provide novel insights and empirical evidence for understanding the relationship between tax reform and export diversification.

1. Introduction

In the context of the significant restructuring of the global trade environment and China’s strategic initiatives to construct a novel development framework, export diversification functions as both a stabilizing force for national economic resilience and a catalyst for industrial advancement. By distributing market risks and accessing new markets, export diversification substantially diminishes a country’s susceptibility to global trade disruptions (Ul-Haq et al., 2025), alleviates macroeconomic volatility (Zélity, 2025), and augments the degree of financial openness (Gnangnon, 2023).

As a major global exporter, China plays a pivotal role in the significant restructuring of international trade and the safeguarding of global supply chain security. This paper investigates the relationship between tax reform and firm-level exports, with a particular focus on the effects of the transition from business tax to value-added tax (RBTVAT) on firms’ export diversification (ED). While existing literature has predominantly examined the influence of factors such as capital intensity and technological innovation capability (Brambilla, 2009), trade liberalization measures (Dennis & Shepherd, 2011), market competition intensity (Mayer et al., 2014), foreign direct investment (R. D. Yang & Wu, 2019), and foreign aid (C. R. Sun et al., 2025) on ED, the impact of significant tax reforms, specifically the RBTVAT reform, on export diversification at the firm level remains relatively underexplored.

In practical terms, tax burdens and complexities, such as the cascading effect of the pre-reform business tax, can substantially limit firms’ resources and strategic flexibility. Firms encountering higher effective tax rates or administrative burdens may lack the requisite liquidity or managerial capacity to invest in the development and marketing of new export products (Manova, 2013; Mayer et al., 2014). This situation naturally prompts a critical question: How do firms’ financial constraints, profitability, innovation capabilities, and ownership structure influence their export diversification responses to the RBTVAT reform? Addressing this question is crucial for understanding how tax policy can be utilized to promote more dynamic and resilient export sectors. However, this particular aspect of the RBTVAT reform’s impact, especially on export diversification, has been relatively underexplored in the literature, and empirical evidence at the firm level remains scarce.

In order to examine this issue, we concentrate on China’s Reform of the Business Tax to Value-Added Tax (RBTVAT). This reform, initiated in January 2012 and implemented nationwide by August 2013, sought to eliminate double taxation, alleviate the overall tax burden—particularly for the service sectors and manufacturing firms that procure services—and streamline the tax system to enhance economic efficiency. It marked a significant transformation in China’s tax structure, with substantial implications for firm costs and investment incentives. Notably, the impact of the reform was highly heterogeneous. Firms previously subjected to high business tax rates, those heavily dependent on service inputs, or those operating in newly included sectors were likely to benefit disproportionately from input tax credits and reduced effective tax rates (Y. Fan et al., 2019; Bai & Wu, 2024). This heterogeneity offers a valuable quasi-experimental context. Analyzing how this major tax reform affected firms’ strategic decisions regarding export diversification, and identifying which firms were most impacted, provides critical insights for policymakers in China and other emerging economies considering similar tax reforms.

Utilizing extensive firm-level production data sourced from the Annual Survey of Industrial Firms Database and the Chinese Customs Database, this study leverages the staggered implementation of the RBTVAT reform across various sectors and regions as a quasi-natural experiment, employing the difference-in-differences methodology. This analytical framework allows for precise identification of the causal impact of the tax reform on firms’ ED, while systematically examining the variation of this effect in relation to firm-specific characteristics such as pre-reform financing constraints, ownership structure, profitability, and innovation capabilities. The analysis reveals that the RBTVAT reform leads to a significant reduction in ED, an increase in export value, and a decrease in unit prices among the affected manufacturing firms. Notably, the adverse impact on ED is more pronounced for firms experiencing higher financing constraints, lower profitability, weaker innovation capabilities, and larger firm size. This effect is consistently observed across both state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. The robustness of these findings is confirmed through several rigorous tests, including alternative measures of ED, extended estimation time intervals, and other methodological variations. The RBTVAT reform facilitates a heightened degree of production specialization among firms, thereby encouraging a focus on core product manufacturing and resulting in a reduction in the diversity of exported product categories. This specialization effect also leads firms to decrease the ratio of intermediate inputs to export value and to limit the variety of imported intermediate inputs. As firms narrow their range of exported categories, there is a corresponding decline in the number of destination countries they serve. Nonetheless, the reform enhances export quality. Additionally, the RBTVAT reform substantially increases the total export tax rebates received by enterprises by optimizing the VAT deduction chain, which subsequently alters the relative costs and profitability of different products. This shift incentivizes enterprises to reallocate resources, directing production factors away from low-rebate-rate, low-value-added products towards high-rebate-rate, high-profit core products, thereby diminishing ED. This effect is particularly pronounced among enterprises that produce high-rebate-rate products.

The principal contribution of this paper is articulated across three dimensions. Firstly, it presents the inaugural direct causal evidence connecting a significant domestic tax reform, referred to as RBTVAT, with alterations in firms’ strategic export behaviors, particularly in terms of export diversification. This discovery addresses a crucial gap in the existing literature, which has predominantly concentrated on export scale or intensity and export quality, while largely neglecting the dynamics of diversification. Secondly, the study elucidates the pivotal role of firms’ financial constraints, ownership structures, profitability, innovation capacity, and size disparities in shaping their diversification responses to the RBTVAT reform. It reveals the influential mechanisms through which the reform impacts firms’ export diversification, primarily by encouraging specialization in production and enhancing export rebates for firms within the high-rebate category. Thirdly, this research focuses on China, a leading global exporter undergoing substantial institutional reforms. In the context of the nationwide implementation of China’s RBTVAT reform initiated in 2012, it highlights the critical importance of conducting comprehensive research on this policy at the present juncture. The findings and empirical methodology of this research establish an analytical framework for evaluating analogous reforms in other regions. Furthermore, the study enhances the comprehension of tax policy optimization in China and provides significant insights for international tax reform.

This study substantially contributes to the intricate discourse concerning tax reform policies and export market dynamics in developing countries. Through a comprehensive, context-specific analysis underpinned by rigorous methodological support, this research enhances the understanding of the complex interplay between tax reform policies and ED.

2. Literature Review

This paper examines the effects of the RBTVAT policy on firm exports, with a specific emphasis on export categories, and includes a comprehensive literature review spanning two interconnected domains. The initial area of research addresses the theoretical framework related to the RBTVAT reform and its implications for export diversification. The subsequent section of the study provides a critical synthesis of empirical evidence concerning the RBTVAT reform.

2.1. Theoretical Framework: RBTVAT Reform and Export Diversification

The analysis of firms’ export product diversification is fundamentally grounded in the integrated theoretical framework of Multi-product Firm Theory (Bernard et al., 2011) and Heterogeneous Firm Trade Theory (Melitz, 2003). These models posit that a firm’s decision to export and its choice of product scope are determined by its productivity, the fixed costs of market entry and product development, and the intensity of market competition. Only firms exceeding a certain productivity threshold can profitably bear the fixed costs associated with exporting a broader product range (Helpman et al., 2004; Melitz & Ottaviano, 2008). Concurrently, the welfare models of Krugman (1980), Feenstra and Ma (2008) highlight the gains from increased product variety through trade, establishing diversification as a key channel for economic efficiency.

The RBTVAT reform, as a major supply-side policy, alters firms’ effective tax rates and cash flows (Bai & Wu, 2024). This intervention can be directly mapped onto these structural models: the reform effectively impacts the fixed cost threshold for maintaining and managing product lines by altering the tax burden on intermediate inputs and improving liquidity. Thus, the RBTVAT reform provides a quasi-natural experimental setting to test a core prediction of these classical models: how an exogenous reduction in operational costs influences firms’ optimal product scope decisions.

Furthermore, New New Trade Theory suggests that firms discover their comparative advantage and true production costs through participating in export markets (Hausmann & Rodrik, 2003). The RBTVAT reform, by altering firms’ cost structure and available cash flows, affects both the process and incentives for this cost discovery.

However, the reform’s impact is not uniform. The Resource-Based View (Barney, 1986; Barney, 1991) suggests that firms’ strategic responses to the reform will be heterogeneous, depending on their specific capabilities and constraints. This heterogeneity is further amplified by financing constraints, which directly affect firms’ ability to cover the high fixed costs of developing new products or entering new markets (Manova, 2013; T. Zhang et al., 2021). For the strategic choice of export diversification, firms’ innovation capability is another critical internal condition that determines their ability to develop new products and expand their product scope (Arslanagic-Kalajdzic et al., 2017).

2.2. Empirical Evidence on RBTVAT Reform: A Critical Synthesis

The empirical literature examining the RBTVAT reform in China can be synthesized into three distinct yet interconnected strands, each providing crucial insights for understanding the reform’s potential impact on firm export behavior, particularly export diversification.

The first strand examines tax burden adjustments and their implications for firm export performance. The reform fundamentally operates by altering firms’ effective tax burdens and resource allocation. Research reveals a complex and heterogeneous picture: Y. Cao and Li (2016) found the reform initially increased the turnover tax burden for pilot firms before a slight long-run reduction, while Y. Fan et al. (2019) observed significant declines in effective VAT rates. G. Lin et al. (2024) identified a critical fiscal interaction, where substantial VAT cuts created a tax substitution effect, prompting local governments to intensify corporate income tax enforcement, disproportionately affecting non-state-owned and small enterprises. International evidence, such as from Pinto et al. (2024) in Honduras, confirms that the efficiency of VAT refund mechanisms significantly impacts firms’ cash flows and investment decisions. This heterogeneity in tax burden changes directly reshapes firms’ internal liquidity, which in turn constrains or enables their capacity to invest in developing new product lines and exploring new markets, forming a primary channel through which the reform could influence export diversification.

The second strand investigates the reform’s promotion of specialized production and its consequences for export performance. Grounded in the theory of multi-product firms, which models firms as portfolios of products leveraging core competencies (Bernard et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2014), this line of inquiry posits that tax policy can shift the equilibrium between economies of scope and managerial costs. The pre-reform Business Tax system incentivized vertical integration to avoid repeated taxation, often at the expense of production efficiency and specialization (Z. Lin, 2013; Cui, 2014). By eliminating double taxation, the RBTVAT reform aimed to promote industrial division of labor and specialized production (Z. Chen & Wang, 2016). Empirical studies confirm that the reform reduced the degree of enterprise integration, indicating a move towards greater specialization (X. Sun et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2022). Such specialization, as theorized by Eckel et al. (2015), drives firms to focus resources on their core, most competitive products, potentially narrowing their product scope while enhancing product quality. This provides a key mechanism linking the reform to a strategic reconfiguration of the export product mix, where a reduction in the number of export categories may coincide with an upgrade in the quality and unit value of remaining exports.

The third strand focuses on the reform’s broader impact on export performance and specifically highlights the pivotal role of export tax rebates. Studies have examined its effects on export scale, intensity, and quality, generally finding positive outcomes through channels like credit constraint alleviation and cost reduction (Sheng & Yang, 2020; Pernet, 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Research on the determinants of export product scope indicates that firm-level productivity and profitability are critical (Melitz, 2003; Qiu & Zhou, 2013), with evidence suggesting that while high-productivity firms are more likely to expand their product scope, such expansion may also increase average costs. Furthermore, innovation capability acts as a vital engine for diversification by enabling new product development (Mayer et al., 2014). Building on this foundation and the Heterogeneous Firm Trade Theory (Melitz, 2003), this strand further analyzes how the RBTVAT reform, by optimizing input VAT deduction, interacts with the export rebate system to shape firms’ cost structures and profitability. Studies show that export tax rebates can enhance firm performance metrics like total factor productivity and profitability (D. Zhang, 2021). Crucially, because rebate rates vary across products, the reform can alter the relative profitability of different product lines. This incentivizes firms to reallocate resources from low-rebate, low-value-added products to core products with higher rebate rates, thereby actively adjusting their export product scope (Tan et al., 2015). Thus, the export rebate mechanism serves as a direct policy channel through which the RBTVAT reform can influence firms’ decisions regarding export diversification.

In summary, existing literature has thoroughly explored the RBTVAT reform’s effects on firm tax burdens, its inducement of specialized production, and its interaction with export rebates, highlighting their significant impacts on various dimensions of export performance, from scale and quality to the determinants of product scope. However, a systematic examination of how these mechanisms jointly shape export diversification, which is a critical dimension of firm resilience and strategic restructuring, remains absent. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the reform’s impact on export product scope, specifically through the dual channels of specialized production and export tax rebate incentives.

3. Background and Methodology

3.1. Background

China’s VAT system has gone through more than 40 years of development and reform and has gradually become the main tax in the current national tax system. The historical development of the VAT system can be traced back to 1954 when the first VAT system was introduced in France. China formally introduced VAT in 1979 and carried out pilot projects in some industries and cities, and since 1 January 1994, China has fully implemented production-based VAT nationwide. In order to meet the needs of economic development, between September 2004 and January 2009, China initiated a major tax transition, reforming the production-based VAT to a consumption-based VAT, achieving a historic optimization of the tax system. By continuously expanding the scope of taxation and improving the policy design, VAT eventually developed into the tax with the highest share of fiscal revenue in China.

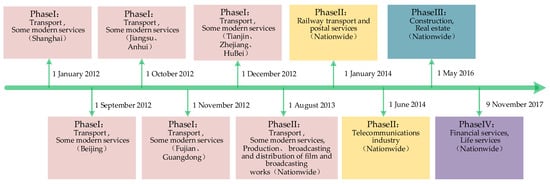

In order to establish a more scientific tax system and support the development of modern service industries, the State Council approved the implementation of a pilot scheme of RBTVAT in Shanghai from 1 January 2012 onwards for transport and some modern service industries. At 1 September 2012, the State Council expanded the pilot of the RBTVAT policy to 9 provinces. As of 1 August 2013, the RBTVAT policy had been extended nationwide on a trial basis.

From 1 January 2014, the RBTVAT policy was extended to include all transportation industries, including railway transportation and postal services. From 1 June 2014, the RBTVAT policy was extended to include tele-communication industries. On 1 May 2016, the RBTVAT policy was extended to the construction and real estate industries. Since 1 July 2017, the four VAT rates have been simplified and consolidated to three, the 13% rate has been abolished, and 23 categories of goods related to residents’ living, cultural propaganda and agricultural production, which were originally taxed at 13%, have been taxed at 11%, so as to build a fairer VAT system. On 19 November 2017, the RBTVAT policy was further extended to cover the financial services and consumer services sectors, marking the official abolition of the business tax system in China. Since then, the business tax, which had been implemented in China for more than 60 years, has officially become history.

The implementation of the RBTVAT policy can be divided into four major phases, and the specific implementation process of RBTVAT is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Implementation process of RBTVAT.

3.2. Methodology

In the context of the RBTVAT reform policy, firms typically did not have a say in determining whether their regions or industries were included. Instead, such decisions were made by the government based on macroeconomic considerations and the policy implementation timeline. In this sense, this process simulates random assignment, thereby making the policy shock relatively exogenous. Given that the RBTVAT reform is implemented by industry and region, it can be regarded as a quasi-natural experiment.

Referring to Xie et al. (2022), this paper mainly uses the difference-in-differences (DID) method to estimate the impact of the RBTVAT policy on manufacturing firms’ export diversification. In terms of policy effectiveness, for export firms, the RBTVAT is an exogenous policy, and the probability of export firms obtaining the benefits of the RBTVAT policy through migration is very low in the short period after the pilot is implemented. Therefore, it is reasonable to use the DID method for analysis.

Therefore, the model setting follows Equation (1):

Among them, subscripts and present the firm and year, respectively, and is a dummy variable representing whether firm is affected by the pilot program of RBTVAT. Following (Xie et al., 2022), when the firm is located in Shanghai, it is set as experimental group and denoted as. When the export firm is located in non-pilot areas,1 they are not affected by the pilot of RBTVAT, and the firms in these areas are set as control groups and denoted as. is a dummy variable that characterizes the years before and after the implementation of the RBTVAT policy. Shanghai started the pilot program of VAT reform on 1 January 2012, so is taken as 0 for years before 2012 and 1 for years after 2012.

The interaction coefficient measures the causal effect of the RBTVAT reform. In addition, represents the dependent variable, which means the number of export categories, export value, export quantity and so on. includes a series of factors that may affect firms’ exports behavior, including firm age, firm age squared, firm size, firm capital labor ratio, firm import tariffs, etc. and represent the fixed effects of the firm and the year, respectively, while represents the residual term.

4. Data and Variable Measurement

4.1. Data Sources

The databases used in this paper primarily draw on three sources: the Annual Survey of Industrial Firms Database (ASIFD), the Chinese Customs Database (CCD), and the Trains Database. Based on data integrity and availability, following Xie et al. (2022), a sample period of 2010–2013 was selected to exclude the confounding effect of China’s VAT transformation policy on the RBTVAT policy in 2009.2 The data cleaning basis for this article is outlined below.

First, the ASIFD, compiled by China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), covers all state-owned and private firms with annual sales revenue exceeding RMB 5 million. It provides detailed financial and operational data, covering key variables such as total assets, capital structure, and profitability. Following Feenstra et al. (2014) and Xie et al. (2022), we removed firms established before 1949, excluded observations from the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and the Tibet Autonomous Region, and dropped observations with negative values for core accounting items. Industry codes were standardized using the 2002 National Economic Industrial Classification (NEIC). Following Zhao and Yu (2012), we use a refined sample of 28 manufacturing industries out of the original 30 industrial sectors.

Second, the CCD records all import and export transactions at the firm level, including firm location, product name, HS codes, origin and destination countries, port, quantity, and value. Tariff data at the HS six-digit level are sourced from the WTO and TRAINS databases (Amiti & Konings, 2007). Finally, we incorporate patent data from the China National Intellectual Property Administration for industrial firms.

The RBTVAT reform was rolled out progressively by industry. During the research timeframe (2010–2013), the reform primarily covered modern service industries and some producer service industries, whereas manufacturing enterprises had generally already been subject to VAT. Therefore, the channels and extent to which they were affected by the reform exhibited systematic differences compared to service industries. Restricting the sample to the manufacturing sector aims to obtain a cleaner experimental group and avoid interference from industry heterogeneity. Export diversification behavior is more typical and observable in the manufacturing industry. Furthermore, since manufacturing is the mainstay of China’s exports, its responses are of critical importance for understanding changes in the trade structure. The industrial enterprise database and the customs database used in this paper have high coverage of the manufacturing sector and good variable matching, enabling a more accurate measurement of firms’ production and export behaviors.

The core explained variable in this study is export diversification. Therefore, this paper retains only firms with at least one year of export records during the sample period, which is an inherent requirement of the research question. Excluding purely domestic firms does not introduce estimation bias, as our analysis focuses on the intensive-margin adjustment of product scope among existing exporters, not on the extensive-margin decision to enter exporting.

After the above steps, we obtain a final sample of 217,544 exporting firms, forming an unbalanced panel over four years. For the baseline regression, the treatment group (Shanghai) contains 12,959 firms, and the control group consists of 32,463 firms.

4.2. Variable Measurement

The key variable in this study is export diversification (ED). We employ the direct count method to measure the degree of a firm’s export diversification. More precisely, following R. D. Yang and Wu (2019), we use the total number of export product categories at the HS 6-digit code level to gauge a firm’s export diversification. The advantage of this approach is that the variety of exported products directly reflects the level of export diversification (Bernard et al., 2010, 2011). Here, HS refers to the Harmonized System, an international standard product classification system. The HS 6-digit product count indicates the number of distinct product categories under the 6-digit HS codes exported by a firm.

Export value (Value) refers to the total annual value of products exported by a firm. Export values are expressed in thousands of RMB, converted at the annual average exchange rate. Export quantity (Quantity) is defined as a firm’s total annual export volume in units. Export unit price (Price) measures the simple average price per unit of a firm’s exports (in RMB) based on HS-6 digit product codes. Treat indicates whether a firm participated in the RBTVAT pilot program (1 = yes, 0 = no). Post is a dummy variable equal to 1 for the post-reform period and 0 for the pre-reform period.

The control variables are included in Equation (1). The age of the firm (Age), measured by its opening time, is used to control the impact of operational experience on the firms’ exports. Firm age squared (Age2), defined as the square of years since establishment, is included to capture the potential nonlinear effect of firm age on exports (Liu & Qiu, 2016). Firm size (Asset) is measured by total assets. Larger firm size typically entails greater fixed asset investment, reflecting the firm’s relative advantages in production and operation (Nie et al., 2009). The capital–labor ratio (K/L), measured as total assets per employee, captures the effect of capital intensity on export behavior (Zou et al., 2019). Firm-level import tariffs (Imp. Tariff), constructed following Yu (2015) and Yu and Yuan (2016), are included to account for export-side effects stemming from import tariff shocks. Following Zou et al. (2019), corporate income tax (Cor. tax) is included to capture its potential effect on export behavior. Per capita sales (Sales) are incorporated to capture the effect of production efficiency on export performance (Nie et al., 2009). The descriptive statistics of the main variables in this article are shown in Table 1.3

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Estimation Results

Table 2 reports the baseline estimation results of the effect of RBTVAT on firms’ export. Column (1) shows a negative and statistically significant effect of the RBTVAT reform on ED at the 1% level. Column (2) shows a positive and statistically significant effect of the RBTVAT reform on export value at the 1% level. Column (3) shows that the RBTVAT reform has a negative impact on the total export quantity of firms, but it is not significant. Column (4) indicates that the RBTVAT reform has a positive impact on the export unit price of firms, which is significant at the 1% level.

Table 2.

The effects of RBTVAT on firm’s export.

Table 2 presents benchmark regression results that reveal a coherent narrative of how the RBTVAT reform reshaped firms’ export strategies. The reform led to a statistically significant reduction in the number of export product categories (coefficient = −0.6428), indicating a strategic narrowing of firms’ product ranges. This coefficient implies that affected firms, on average, reduced their export product categories by approximately 9.26% against the pre-reform sample mean of ED (6.936). Prior to the reform, the average annual growth rate of ED in the pilot city Shanghai during the period 2010–2011 was approximately 19.2%. The estimated policy effect of −0.6428 represents a deviation from this pre-existing trend that is economically substantial. It indicates that the RBTVAT reform not only halted the natural diversification trend but also reversed it, leading to a significant contraction in product scope relative to the industry norm.

This decline in diversification coincided with a significant increase in export unit prices (coefficient = 0.1392), which was the fundamental driver of the growth in total export value (coefficient = 0.1345). The absence of a significant change in export volume suggests that the growth in total value did not stem from an expansion in export scale but rather from a structural upgrade within firms’ product portfolios—shifting from low-value to high-value products. Together, these findings paint a clear picture: following the RBTVAT reform, firms may have transitioned from a diversification strategy to a specialization strategy, concentrating resources on enhancing the value of their core products.

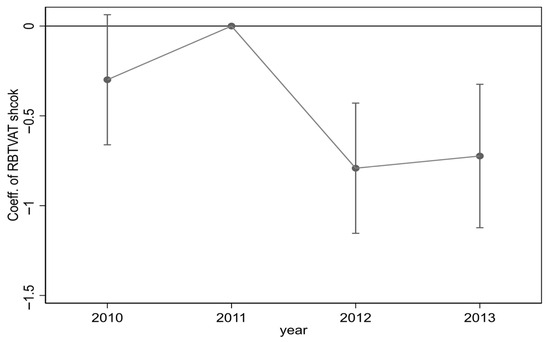

5.2. Parallel Trend Test

The premise for the effectiveness of the DID method is to satisfy the parallel trend assumption, that is, before the implementation of the RBTVAT reform policy, the distribution of export categories of firms in the experimental group and the control group is consistent. Based on this, this paper refers to the methods of Jacobson et al. (1993), Beck et al. (2010) to perform parallel trend test of the baseline estimation results.

According to Equation (2), if the gap between the firms in the treatment group and the control group in terms of export categories does not change significantly every year before the implementation of the RBTVAT reform policy, it can be confirmed that the parallel trend hypothesis is satisfied between the two parties. Among them, represents the number of exported product categories of enterprise in year . represents the intensity of each year before and after the RBTVAT reform, time represents the set of years before and after the implementation of the policy. is a year dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for observations in the current year and 0 for observations in all other years. The regression results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parallel trend test.

The dependent variable in Table 3 is the number of export categories. Column (1) reports the baseline specification without controls, and column (2) adds the full set of control variables. Year 2011 is considered the baseline for comparison. The results of columns (1) and (2) show that the firms in the experimental group and the control group can maintain the same trend in the export categories before the policy occurs, and after the policy of RBTVAT, the tax reform has a significant negative impact on the number of export categories of firms, and the impact intensity weakens year by year. Therefore, the results confirm the validity of the parallel trend assumption. Figure 2 showcases the results of the parallel trend tests.

Figure 2.

Parallel trend test. Notes: Vertical bands represent ±1.96 times the standard error of each point estimate.

5.3. Robustness Checks

This subsection presents a comprehensive set of robustness checks to validate the main findings. The analysis employs alternative measures of ED, varies the estimation time intervals, adjusts clustering levels, controls for diverse fixed effects, uses a balanced panel, applies the PSM-DID method, expands the pilot areas, standardizes variables and placebo test.

5.3.1. Alternative Measure of ED

In this subsection, we further assess whether our results are robust in relation to the alternative measure of ED. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) measures the concentration of exports by calculating the sum of the squares of each HS6-level product’s share in a firm’s total export value. A higher HHI indicates that the firm’s exports are more concentrated in a limited number of products, reflecting a lower degree of ED. For represents the share of product in the firm’s total export value, and is the number of products. The advantage of the proxy variable HHI lies in its high sensitivity to changes in high-share products, allowing it to effectively reflect the export structure. To assess the robustness of our main findings, we employ the 1-HHI as a proxy for ED. A higher value of 1-HHI measure indicates a greater degree of diversification. The results are presented in Table 4 column (1). We find the statistically significant and negative coefficients on interaction terms, which indicates that our estimated results are not in conflict with the measures of ED.

Table 4.

Robustness of RBTVAT reform effects.

5.3.2. Increase Estimated Time Interval

Referring to Tian and Fan (2017), this paper examines the impact of the RBTVAT policy on the exports categories of firms in different time intervals by changing the method of estimating the number of years before and after the introduction of the RBTVAT policy in 2012. Column (2) in Table 4 selects the interval from 2009 to 2013 for testing, and the results in column (2) show that compared with the baseline results, the impact of the RBTVAT reform on export categories is still negative, and it is significant at the 5% level, indicating that the baseline regression result are robust.

5.3.3. Cluster at City or Industry Level

The statistical inference for the baseline estimates in Table 2 relies on accurate standard errors, which are clustered at the firm level in all specifications. Following Bertrand et al. (2004) and Du et al. (2020), we cluster robust standard errors at the city level in column (3) to mitigate potential serial correlation and heteroscedasticity. In column (4), following H. M. Yang and Li (2021), we cluster standard errors at the CIC4 industry level. As shown in Table 4, the estimated coefficient on the key explanatory variable remains consistent with the baseline results under both alternative clustering schemes, and the negative effect of the RBTVAT reform on ED remains significant at the 1% level.

5.3.4. Alternative Fixed Effects Specification

To examine whether our findings are sensitive to the fixed effects specification, we follow D. Chen (2022) and T. Lin (2022) and estimate an extended model that includes firm, year, CIC 3-digit industry, and industry-year (two-digit industry × year) fixed effects simultaneously. Standard errors are clustered at the CIC 3-digit level. Column (5) of Table 4 shows that, compared with the baseline specification, the estimated coefficient on the key explanatory variable remains negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that our main results are robust to a highly demanding set of fixed effects.

5.3.5. Balanced Panel

The RBTVAT reform was first piloted in Shanghai, starting in 2012. While it is unlikely that firms would relocate in the short run solely to benefit from the policy, potential migration could, in principle, introduce selection bias. To address this concern, we follow Zou et al. (2019) and re-estimate the baseline model using a balanced panel constructed from the 2010–2013 period. The results in column (6) of Table 4 show that the negative effect of the RBTVAT reform on export categories remains statistically significant at the 1% level in the balanced panel. This finding supports the robustness of our baseline results and mitigates concerns regarding selection bias due to sample attrition or firm relocation.

5.3.6. PSM-DID Method

A further concern is that the designation of pilot cities may not be random; for instance, cities with a more favorable business environment could be systematically selected for the RBTVAT reform, potentially biasing the estimates. To address this, we apply a Propensity Score Matching-Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) approach following He et al. (2024). This method matches pilot cities and industries with comparable non-pilot units based on observable covariates that may influence both the likelihood of being selected for the reform and subsequent changes in export performance. Column (7) of Table 4 reports the PSM-DID estimate using 1:3 nearest-neighbor matching. The coefficient on ED is −0.5826, indicating that the RBTVAT reform significantly reduces ED.

Because the analysis centers on ED, comparability requires that treated and control firms operate in similar industries. Following Xie et al. (2022), we refine the matching procedure by selecting control firms from the same two-digit industry that exhibit the closest propensity scores to treated firms, thereby ensuring a more comparable product-scope baseline. Regression results based on Equation (1) using this matched sample are reported in column (8) of Table 4. The estimated coefficient remains negative and statistically significant, confirming that the negative effect of the RBTVAT reform on ED is robust to industry-restricted matching.

5.3.7. Replace the Pilot Area

The baseline analysis focused on the Shanghai pilot. Later in 2012, the reform was extended to eight additional provinces. To assess whether our findings hold when the set of pilot regions is expanded, we follow Xie et al. (2022) and re-estimate the model including all eight late-starting pilots except Shanghai. Because these pilots were launched near the end of 2012 and policy effects may exhibit a lag, we treat 2013 as the first effective policy year for these regions. Results in column (9) of Table 4 show that the estimated coefficient remains negative and statistically significant, albeit slightly smaller in magnitude than the Shanghai-only baseline estimate. This confirms that the negative effect of the RBTVAT reform on ED is robust to the inclusion of the broader set of pilot regions.

5.3.8. Standardize the Variables

To mitigate the influence of variable scale and outliers, we standardize all continuous variables (mean zero, unit standard deviation) in column (10) of Table 4. The results show that after standardization, the estimated effect of the RBTVAT reform on ED remains negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, and the coefficient magnitude is close to the baseline estimate. This confirms that our main finding is not driven by differences in measurement scale or extreme values.

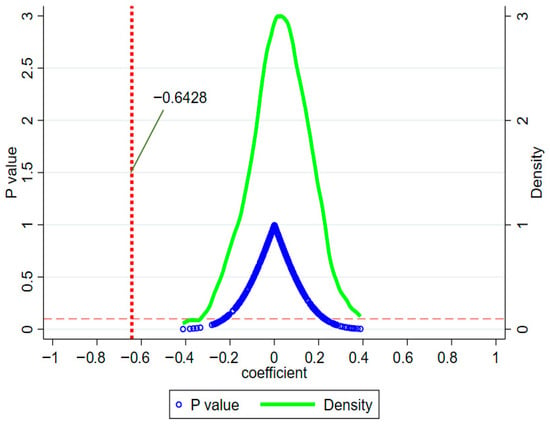

5.3.9. Placebo Test

In this paper, a placebo test is used to solve the problem of non-random selection in Equation (1). The number of firms participating in the RBTVAT reform was randomly assigned in each city. Because in 2012, a total of 6977 export firms participated in the RBTVAT reform, 6977 firms were randomly selected among all firms for regression. This process was repeated 500 times to obtain the coefficients and corresponding p values of 500 export categories of firms under the RBTVAT reform. The kernel density distribution for these coefficients is shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the coefficients of each placebo test fluctuate around the value of 0 and are far from the results of the benchmark regression coefficient −0.6428. Therefore, the placebo test of random allocation of firms affected by the RBTVAT reform also shows that the baseline regression results are reliable.

Figure 3.

City placebo test.

5.4. Heterogeneous Effects

To investigate the differential effects of the RBTVAT reform on ED across various firm types, this chapter undertakes a heterogeneity analysis of the policy’s impact on firms’ ED. The analysis examines variations in financing constraints, ownership structure, profitability, innovation capability, and firm size.

5.4.1. Financing Constraints

This subsection examines how the effect of the RBTVAT reform varies with firms’ financing constraints. Theory suggests that tighter financing constraints limit firms’ ability to bear the fixed costs of developing and exporting multiple products (Manova, 2013; T. Zhang et al., 2021). We measure financing constraints as the ratio of interest expense to fixed assets (Y. J. Cao & Mao, 2019) and split the sample at the median into low-constraint and high-constraint groups. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 report the results. While the coefficient for low-constraint firms is negative but statistically insignificant, the estimate for high-constraint firms is negative and significant at the 1% level. This suggests that the decline in ED resulting from the RBTVAT reform is primarily concentrated among firms facing higher financing constraints.

Table 5.

Financing constraints, Firm ownership, Profitability, Innovation and Firm size heterogeneity.

5.4.2. Ownership

Existing research confirms that non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) face tighter financing constraints than state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Allen et al., 2011; Ge et al., 2020). As shown in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5, the VAT reform significantly reduces ED for both SOEs and non-SOEs at the 1 percent level. In the short run, the reform lowers the export categories of both firm types, but through distinct channels and to varying degrees.

Constrained by tighter financing and high sensitivity to cash flow, non-SOEs saw their liquidity squeezed during the initial phase of the RBTVAT reform, due to upfront input VAT payments and higher compliance costs. This limited their ability to develop new products and explore new markets. Faced with a potential rise in effective tax burden and greater cost uncertainty, they responded in a market-oriented manner: scaling back less profitable, non-core product lines to focus resources on core competitive products. This efficiency-driven adjustment under fiscal pressure likely explains the decline in their export categories.

Subject to stringent policy compliance rather than financing constraints, SOEs responded to the enhanced regulatory standards for tax audits and invoice management under the RBTVAT reform by streamlining their supply chains and business structures. To mitigate compliance risks—such as inadvertently accepting fraudulent invoices—they would reduce engagements with numerous small and irregular service providers. This rationalization of operations led to a narrowing of export categories, especially for non-traditional products dependent on diverse and flexible supply chains.

5.4.3. Profitability

Following Cucculelli and Micucci (2008) and Fu et al. (2021), this subsection uses return on assets (ROA) to measure corporate profitability. Based on their ROA, sample firms are divided into low- and high-profitability groups, with the median profitability as the cutoff. The results in column (5) of Table 5 indicate that the RBTVAT reform exerts a significant negative effect on ED of firms in the low-profitability group at the 1% level. Column (6) shows that the reform also has a negative impact on firms in the high-profitability group, though the effect is not statistically significant.

A possible explanation is that the RBTVAT reform reduces the tax burden for less profitable firms through its export tax rebate effect. Compared to more profitable firms, less profitable firms may be more sensitive to the cash flow changes brought by the RBTVAT reform, enabling them to proactively phase out low-end production and concentrate resources on higher-value-added core products, thereby narrowing the diversification of their export product range.

5.4.4. Innovation

The impact of tax policy may vary significantly across firms with different innovation capabilities (Qi et al., 2025). Following Tan et al. (2015), this subsection uses the number of patents applied for by firms to measure innovation, with classification based on the sample median. The results in Column (7) of Table 5 show that the RBTVAT reform exerts a significant negative effect on the export categories of firms with low innovation ability at the 1% level. In contrast, Column (8) indicates that the reform also has a negative impact on firms with high innovation ability, though the effect is not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the RBTVAT reform significantly reduces the export categories of firms with low innovation ability.

5.4.5. Firm Size

According to the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), firm size serves as a key manifestation of a company’s resource endowment and strategic capabilities. This section explores the heterogeneity of the RBTVAT reform’s effect on ED with respect to firm size. Firms are classified into below- and above-median size groups. As shown in Table 5, column (9) indicates no statistically significant effect of the reform on small firms’ ED. In contrast, column (10) demonstrates that the reform significantly reduces the ED of large firms.

The heterogeneous impact of the RBTVAT reform across firm sizes stems from differences in resource endowments and strategic flexibility. Large firms, with stronger financial and managerial resources, could use the tax-induced liquidity improvement to strategically reallocate resources—shifting from a broad, low-margin product mix toward a focused range of high-value core products to achieve scale and quality upgrading. Small firms, however, often operate with tighter constraints and narrower initial scopes, limiting their ability to strategically consolidate. Their export diversification is typically driven more by survival and niche market exploration than by deliberate optimization. Thus, the significant reduction in export categories among large firms aligns with their greater capacity to leverage the reform for strategic specialization and productivity gains.

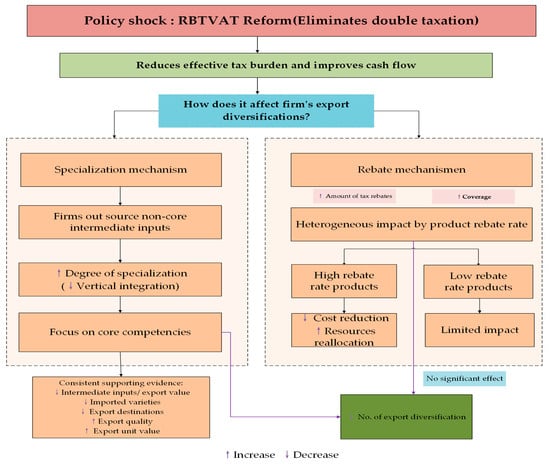

6. Mechanism

We find that the RBTVAT promotes firms to reduce the number of export product categories. In this section, we answer the question of how changes in the external tax environment may affect firms’ export diversification behavior when they experience a RBTVAT policy. We consider two possible channels: a shift towards specialized production and an enlargement of export tax rebates. Figure 4 is the mechanism conceptual diagram.

Figure 4.

Mechanism conceptual diagram.

6.1. Specialized Production Mechanism

In determining their export categories, firms face a trade-off. The theory of Multi-product Firms models a firm as a portfolio of products, emphasizing that its core competencies—such as brand, technology, and managerial know-how—constitute comparative advantages (Bernard et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2014). Firms weigh economies of scope against the managerial costs of a broader product range. Tax policy changes can shift this equilibrium. The RBTVAT reform, by reducing double taxation and intermediate input costs, likely enhances specialization advantages in core products, encouraging firms to shed peripheral lines and thus narrow their export scope—a specialization effect. This subsection examines how the reform influences export categories through this channel.

Prior to the RBTVAT reform, the business tax burden rose with the length of production and distribution chains, incentivizing firms to internalize intermediary activities to lower tax costs (Z. Lin, 2013). While this reduced tax expenses, it also diminished production efficiency (Cui, 2014), often resulting in less specialized, smaller-scale, lower-quality, and cheaper products. The RBTVAT reform, by eliminating double taxation, sought to promote deeper industrial specialization and alleviate corporate tax burdens. As firms no longer face repeated taxation on purchased intermediate goods and services, they can outsource non-core activities, focus on their main operations, and enhance specialized production (Z. Chen & Wang, 2016).

Drawing on the research of X. Sun et al. (2020) and Xie et al. (2022), this study adopts the degree of enterprise integration as an inverse measure of specialization. This indicator is constructed based on the theoretical understanding that integration and specialization represent two ends of the spectrum in enterprise operational models (Xie et al., 2022), where a higher degree of integration typically corresponds to a lower level of specialization. For measurement, we employ the widely used value-added-to-sales ratio (VAS) to gauge the degree of enterprise integration. This metric, calculated as the proportion of a firm’s value added to its sales revenue, reflects the extent of vertical integration within the value chain. A higher VAS ratio indicates that the firm internalizes more production stages, leading to more dispersed resource allocation, a broader product scope, and thus a lower level of specialization. Conversely, a lower VAS ratio suggests greater reliance on external markets for intermediate inputs, enabling the firm to concentrate resources on core activities and achieve a higher level of specialized production.

As Eckel et al. (2015) argue, leaner, more productive firms tend to focus more on core competencies and produce fewer non-core products, reducing product variety. In other words, specialization drives firms toward their most competitive products. Consistent with this, Column (1) of Table 6 shows a significantly negative coefficient for the interaction term, indicating that the RBTVAT reform significantly raised the production specialization level of manufacturing firms. This finding aligns with the conclusions of X. Sun et al. (2020) and Xie et al. (2022) regarding the reform’s effects. Increased specialization allows firms to outsource non-core production, concentrate resources on core products, and thus reduce the number of product categories they handle. As shown in Column (2) of Table 6, the RBTVAT reform significantly reduced the ratio of intermediate inputs to export value.4 This decline indicates an improvement in production efficiency, suggesting that firms generated greater and potentially higher-quality output from the same level of intermediate inputs, thereby increasing total export value. This finding strongly supports the specialized production mechanism, as firms concentrating resources on high value-added core activities naturally reduced their reliance on simple intermediate inputs.

Table 6.

Mechanism: Specialized production.

Table 6 further details the implications of this shift. Column (3) shows that the reform reduced the variety of imported intermediates, consistent with a focus on core production that relies on fewer, more specialized inputs.5 Column (4) indicates a decline in the number of export destination countries, suggesting that as firms specialize, they may exit markets for non-core goods, narrowing their export footprint. Column (5) demonstrates that the reform promoted the upgrading of firms’ export product quality, a finding consistent with Xie et al. (2022).6 A plausible explanation is that specialization induced by the reform enabled firms to concentrate resources on developing and manufacturing higher-quality core products, thereby improving overall export quality.

This quality improvement provides a key link to the broader export performance outcomes. As shown in Column (4) of Table 2, the reform significantly increased firms’ export unit prices—a change partly attributable to the quality upgrading revealed in Table 6. With export quantities showing no significant change (Table 2, Columns 3), the rise in unit values drove the growth in total export value. This pattern aligns with findings such as those of Dong and Chen (2011) on the role of high-quality, technology-intensive products in trade growth.

In summary, the evidence in Table 6 forms a coherent causal chain. The reform significantly reduced the degree of enterprise integration (coefficient = −0.0244, column 1), signaling a move toward outsourcing non-core activities and focusing on core production. This deepening specialization triggered a sequence of adjustments: a reduction in the variety of imported intermediates (coefficient = −2.3385, column 3), a decrease in the number of export destination countries (coefficient = −0.3092, column 4), and a final enhancement in the exported quality (coefficient = 0.2739, column 5). This indicates that firms underwent not a simple reduction in export categories, but a profound reconfiguration of their value chain. By sharpening their focus on core competencies, they achieved product quality upgrading. This mechanism precisely explains the concurrent reduction in export product categories and the increase in export unit prices and total value.

6.2. Export Tax Rebates Mechanism

Heterogeneous Firm Trade Theory posits that only highly productive firms can overcome the fixed costs of exporting and enter foreign markets, while less productive firms serve only domestic markets or exit (Melitz, 2003). As an exogenous policy shock, the RBTVAT reform alters firms’ cost thresholds by changing their effective tax rates and cash flows. Building on this framework and extending it to multi-product firms with heterogeneous financing constraints (Manova, 2013), we argue that the reform’s effect on cash flow and tax burdens varies across firms with different financing constraints, leading to divergent export diversification strategies.

Following the RBTVAT reform, firms became eligible to deduct input taxes, though the benefits are most fully realized with standardized procurement and production processes. As shown in Column (1) of Table 7, the reform significantly increased the total export tax rebates received by firms. Since statutory rebate rates are set by policy, this aggregate increase implies an expansion in the coverage of the rebate scheme; that is, a larger share of firms’ products qualified for and claimed rebates.

Table 7.

Mechanism: Export tax rebates.

To examine heterogeneous effects, firms are grouped based on whether their average export tax rebate value is below or above the sample median. Columns (2) and (3) of Table 7 show that the reform had no significant impact on ED of firms in the low-rebate group but led to a significant reduction on ED for firms in the high-rebate group.

The adjustment effect of the RBTVAT reform on the export product structure primarily stems from differences in cost sensitivity among products with varying tax rebate rates. For products with low tax rebate amounts, the rebate constitutes a small proportion of costs, limiting the reform’s impact on their competitiveness. In contrast, for products with high tax rebate amounts, the rebate represents a larger share of costs. By optimizing RBTVAT deductions, enterprises can significantly reduce their tax burden and increase profits. This incentivizes firms to reallocate resources from low-value-added products with low rebate rates to core products with higher rebate rates.

Table 7 further confirms that the reform overall increased enterprises’ export tax rebates, and the reduction in ED was entirely driven by firms producing high-rebate products. The underlying logic is that high-rebate products gain a more pronounced profit advantage from the reform (see column 4 and column 5), motivating enterprises to proactively adjust their production structure and focus on developing core products with higher rebate rates.7 This reallocation of resources, based on changes in relative profitability, reflects an effective market response to tax policy signals.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that China’s RBTVAT reform, by eliminating double taxation, has fundamentally reshaped the export strategies of manufacturing firms, thereby steering them from breadth-oriented diversification to depth-oriented specialization. Specifically, the reform reduced export categories by 9.26% while raising export unit price by 13.92%, which confirms a reallocation of resources toward higher-productivity products. In terms of theoretical contribution, this research lies in elucidating and validating the dual-channel mechanism through which VAT neutrality operates: namely, fostering a Smithian deepening of the division of labor by lowering outsourcing costs, and creating a profit-signal-guided specialization via enhanced export tax rebates.

Based on these findings, several critical implications emerge. First, they underscore the potent role of relative price signals in guiding micro-level resource allocation. Notably, the reform’s effectiveness hinges not merely on a general tax reduction but on its precise alteration of the cost calculus between in-house production versus outsourcing and between high- and low-rebate products. Thus, this provides strong empirical support for price-based market guidance mechanisms in industrial policy. Second, significant heterogeneity in firm responses necessitates differentiated policy design. For instance, financially constrained, less profitable, and less innovative firms primarily channel freed resources into core product upgrading, suggesting that for such entities, tax incentives should prioritize direct cash flow improvement to alleviate liquidity bottlenecks and foster “learning by doing” within value chains. In contrast, for larger, more responsive firms, policy should leverage their capacity to generate positive spillovers across the industrial ecosystem rather than focusing solely on direct subsidies. Finally, the government must balance the efficiency gains from specialization against the potential systemic risk of reduced resilience. Therefore, supporting innovation incentives and financial safeguards is crucial to maintain adaptive capacity in the face of external shocks.

This research reveals, at a deeper level, a central tension inherent in market-enhancing tax reforms. The RBTVAT successfully prompted an efficiency-driven reallocation consistent with static comparative advantage, which is a positive outcome aligned with New New Trade Theory. However, it may simultaneously narrow the scope for the “cost discovery” of new comparative advantages that a more diversified export structure allows. This tension between productive efficiency and adaptive resilience presents a crucial consideration for policymakers aiming to foster sustainable, high-quality development. It is worth noting that the core mechanism identified—VAT neutrality guiding specialization via price signals—remains robust despite subsequent institutional changes.

Moving forward, future research should build on this tension. For example, extending the analysis to a more recent period could examine the long-term dynamics of firm product portfolios and resilience in the context of a mature VAT system and global value chain restructuring. Furthermore, exploring the general equilibrium effects on industrial linkages and welfare, as well as conducting comparative studies with other VAT transition economies, would illuminate whether the observed reallocation patterns and the efficiency-resilience trade-off are generalizable or context-specific. Such work would further deepen our understanding of how tax policy can be optimized to navigate the dual objectives of static efficiency and dynamic growth exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.F.; methodology, Q.F.; software, Q.F.; validation, Q.F. and D.Z.; formal analysis, Q.F.; investigation, Q.F.; resources, Q.F. and D.Z.; data curation, Q.F. and D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.F.; writing—review and editing, Q.F. and D.Z.; visualization, Q.F.; supervision, D.Z.; project administration, Q.F. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, Q.F. and D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province grant number 2025NSFSC1956. This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China grant number 25&ZD117. This research was funded by Major Project of the Key Research Base for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education grant number 22JJD790022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study are available from the author. However, they are public and retrievable from the sources cited in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Non pilot areas refer to other regions in China except for Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Jiangsu, Anhui, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hubei, and Guangdong. |

| 2 | Given that the ASIF demonstrates relatively high data quality for periods prior to 2014, this paper has also excluded samples from the year 2014 and thereafter. |

| 3 | To mitigate the influence of outliers, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. |

| 4 | The ratio of intermediate inputs to export value equals the total industrial intermediate inputs divided by the export trade value. The data for industrial intermediate inputs comes from the ASIFD. |

| 5 | The number of imported intermediate varieties is the count of imported product types of an enterprise in the current year, based on HS-6 digit product codes. |

| 6 | Product quality is measured at the HS 6-digit level using methods from Khandelwal et al. (2013), Bas and Strauss-Kahn (2014), and H. Fan et al. (2018), aggregated to the firm level using export shares as weights. |

| 7 | Profit refers to the profit margin of an enterprise, which is measured by the ratio of operating profit to operating revenue. |

References

- Allen, F., Carletti, E., & Marquez, R. (2011). Credit market competition and capital regulation. Review of Financial Studies, 24(4), 983–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. The American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M., Balboni, B., Kadic-Maglajlic, S., & Bortzuzzi, G. (2017). Product innovation capability, export scope and export experience: Quadratic and moderating effects in firms from developing countries. European Business Review, 29(6), 680–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., & Wu, M. (2024). Tax reform and investment efficiency: Evidence from China’s replacement of business tax with VAT. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(3), 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32(10), 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2014). Does importing more inputs raise exports? Firm level evidence from France. Review of World Economics, 150(2), 241–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Levine, R., & Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. The Journal of Finance, 65(5), 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. B., Redding, S., & Schott, P. K. (2010). Multiple-product Firms and Product Switching. American Economic Review, 100(1), 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2011). Multiproduct firms and trade liberalization. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3), 1271–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, I. (2009). Multinationals, technology, and the introduction of varieties of goods. Journal of International Economics, 79(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., & Li, J. (2016). Whether the reform to replace the business tax with a value-added tax reduces the turnover tax burden—Evidence from Chinese public companies. Finance and Trade Economics, 11, 62–76. Available online: https://cmjj.ajcass.com/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Cao, Y. J., & Mao, Q. L. (2019). How does human capital affect Chinese manufacturing firms’ markups? Evidence from China’s higher education reform. Journal of Finance and Economics, 45(12), 138–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. (2022). Trade barrier decrease and environmental pollution improvement: New evidence from China’s firm-level pollution data. China Political Economy, 5(1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Wang, Y. (2016). Has the “replacement of business tax with value-added tax” promoted division of labor? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Journal of Management World, 2016(3), 36–45+59. Available online: http://www.mwm.net.cn/web/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Cucculelli, M., & Micucci, C. (2008). Family succession and firm performance: Evidence from Italian family firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W. (2014). China’s business-tax-to-vat reform: An interim assessment. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 5, 617–641. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, A., & Shepherd, B. (2011). Trade facilitation and export diversification. The World Economy, 34(1), 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z. Q., & Chen, R. (2011). High technical product, trade and economie growth: An empirical evidence form Jilin’s economy. Journal of Chengdu University of Technology (Social Sciences), 19(4), 35–42. Available online: https://xbshkx.cdut.edu.cn (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Du, Y., Yang, M., Li, J., & Li, Y. (2020). The stagnant export upgrading in Northeast China: Evidence from value-added tax reform. China and World Economy, 28(4), 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, C., Iacovone, L., Javorcik, B., & Neary, J. P. (2015). Multi-product firms at home and away: Cost-versus quality-based competence. Journal of International Economics, 95(2), 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H., Li, Y. A., & Yeaple, S. R. (2018). On the relationship between quality and productivity: Evidence from China’s accession to the WTO. International Economics, 110, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., Li, H., & Zhu, Q. (2019). Tax burden reduction and tax cuts in China’s VAT reform. Journal of Tax Reform, 5(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R. C., Li, Z., & Yu, M. (2014). Exports and credit constraints under incomplete information: Theory and evidence from China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(4), 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R. C., & Ma, H. (2008). Optimal choice of product scope for multiproduct firms under monopolistic competition. In The organization of firms in a global economy (pp. 173–199). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q. Y., Zhang, T., & Li, Y. L. (2021). Trade liberalization induced profitability enhancement? The impact of intermediate input imports on firm profitability. Journal of Asian Economics, 75, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y., Liu, Y., Qiao, Z., & Shen, Z. (2020). State ownership and the cost of debt: Evidence from corporate bond issuances in China. Research in International Business and Finance, 52, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, S. K. (2023). Real exchange rate and services export diversification. Journal of Economic Studies, 50(6), 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Wen, C., & Yang, X. (2024). Navigating the green transition: The influence of low-carbon city policies on employment in China’s listed firms. Energies, 17(8), 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L. S., Lalonde, R. J., & Sullivan, D. (1993). Earnings losses of displaced workers. The American Economic Review, 83(4), 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, A. K., Schott, P. K., & Wei, S. J. (2013). Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: Evidence from Chinese exporters. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2169–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. R. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. The American Economic Review, 70(5), 950–959. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G., Ma, L., Liao, H., & Li, J. (2024). Nothing comes for free: Evidence from a tax reduction of China. China Economic Review, 83, 102109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. (2022). Cleaner production environment regulation and enterprise environment performance—An empirical test based on pollution discharge data of industrial enterprises. Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 24(3), 43–55. Available online: https://journal.bit.edu.cn/sk/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Lin, Z. (2013). VAT replacing business tax: A major tax reform in China. The International Tax Journal, 39(2), 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q., & Qiu, L. D. (2016). Intermediate input imports and innovations: Evidence from Chinese firms’ patent filings. Journal of International Economics, 103, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 80(2), 711–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T., Melitz, M. J., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2014). Market size, competition, and the product mix of exporters. American Economic Review, 104(2), 495–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, M. J., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. The Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H. H., Fang, M. Y., & Li, T. (2009). The impact of value-added tax transformation on firm behavior and performance: Evidence from Northeast China. Journal of Management World, (5), 17–24+35. Available online: http://www.mwm.net.cn/web/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Pernet, T. (2023). Value-added export tax policy, credit constraints, and quality: Evidence from China. Review of Development Economics, 28(2), 499–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D. P., Bermúdez, J. C., & De Gouvea Scot de Arruda, T. (2024). VAT refunds and firms’ performance: Evidence from a withholding reform in Honduras (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 10996). World Bank Group.

- Qi, R.-K., Xiong, Z., & Bilan, Y. (2025). Tax reform, tax shifting and enterprise innovation. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 31(2), 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L. D., & Zhou, W. (2013). Multiproduct firms and scope adjustment in Globalization. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, D., & Yang, H. M. (2020). China’s value-added tax reform and quality upgrade of export products. Journal of Finance and Economics, 46(6), 79–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C. R., Li, M. M., & Yu, J. P. (2025). China’s foreign aid and firm export product diversification. Journal of Quantitative and Technological Economics, 42(12), 1–22. Available online: http://www.jqte.net (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Sun, X., Zhang, J., & Zheng, H. (2020). Will replacing BT with VAT promote the integrated development of manufacturing and services. China Industrial Economics, (8), 5–23. Available online: https://ciejournal.ajcass.com/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Tan, Y., Han, J., & Ma, Y. (2015). Multi-product firms, product scope, and the policy of export tax rebate. China Economic Review, 35, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tian, B. B., & Fan, Z. Y. (2017). “Replacing business tax with value added tax” and the export of manufacturing enterprises: An empirical study based on the difference-in-differences method. Social Science Front, 12, 52–61. Available online: https://www.shkxzx.cn (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Ul-Haq, J., Visas, H., Krivins, A., Remeikienė, R., & Hye, Q. M. (2025). The drivers of export product diversification in China: Does natural resource endowments matter? Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 31(2), 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Liu, H., & Wang, L. (2024). Foreign competition and export diversification: Evidence from domestic firms in China. The World Economy, 48(2), 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. X., Fan, P. F., & Wang, H. (2022). Replacing business tax with value-added tax and high-quality development of export trade. Modern Economic Science, 44(2), 1–15. Available online: http://czyj.chinajournal.net.cn (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Yang, H. M., & Li, K. W. (2021). Does resource allocation efficiency affect export product quality. Economic Science, 3(3), 31–43. Available online: http://jjkx.pku.edu.cn (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Yang, R. D., & Wu, Q. F. (2019). Outward direct investment and the product mix of exporters. Economic Perspectives, (7), 50–64. Available online: https://jjxdt.ajcass.com (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Yu, M. J. (2015). Processing trade, tariff reductions, and firm productivity: Evidence from Chinese firms. Economic Journal, 125(585), 943–988. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. J., & Yuan, D. (2016). Trade liberalization, processing trade and cost-plusing: Evidence from our country’s manufacturing enterprises. Journal of Management World, 24(3), 43–55. Available online: http://www.mwm.net.cn/web/ (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Zélity, B. (2025). Export diversification and macroeconomic shocks. The World Economy, 48(4), 742–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. (2021). Is export tax rebate a quality signal to determine firms’ capital structure? A financial intermediation perspective. Research in International Business and Finance, 55, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Fu, Q. Y., & Zhu, C. H. (2021). Trade liberalization, credit constraints, and export quality upgrading. Empirical Economics, 63, 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. J., & Yu, J. P. (2012). Trade Openness, FDI and industrial economic growth pattern in China: An empirical study based on the data from 30 industrial sector. Economic Research Journal, 47(8), 18–31. Available online: https://erj.ajcass.com (accessed on 11 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Zou, J. X., Shen, G. J., & Gong, Y. X. (2019). The effect of value-added tax on leverage: Evidence from China’s value-added tax reform. China Economic Review, 54, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.