External Shocks, Fiscal Transmission Mechanisms, and Macroeconomic Volatility: Evidence from Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional and Economic Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Structure

3.1.1. Households

3.1.2. Firms

3.1.3. Government and Fiscal Policy

3.1.4. Equilibrium

3.2. Fiscal Transmission Mechanism

3.3. Calibration and Data

3.3.1. Calibration of Parameters

3.3.2. Data Sources and Implementation

4. Results

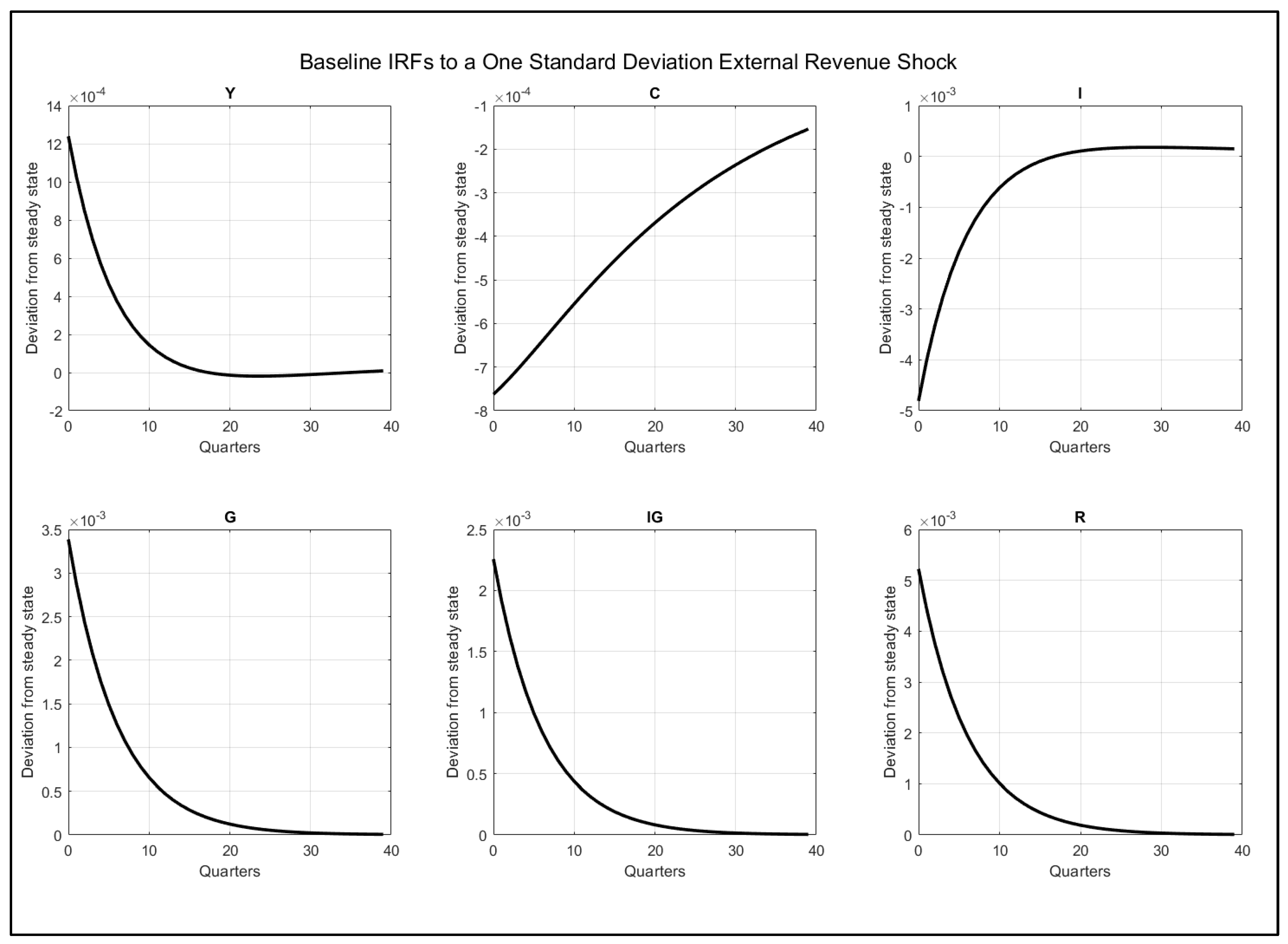

4.1. Baseline Dynamics Under External Revenue Shocks

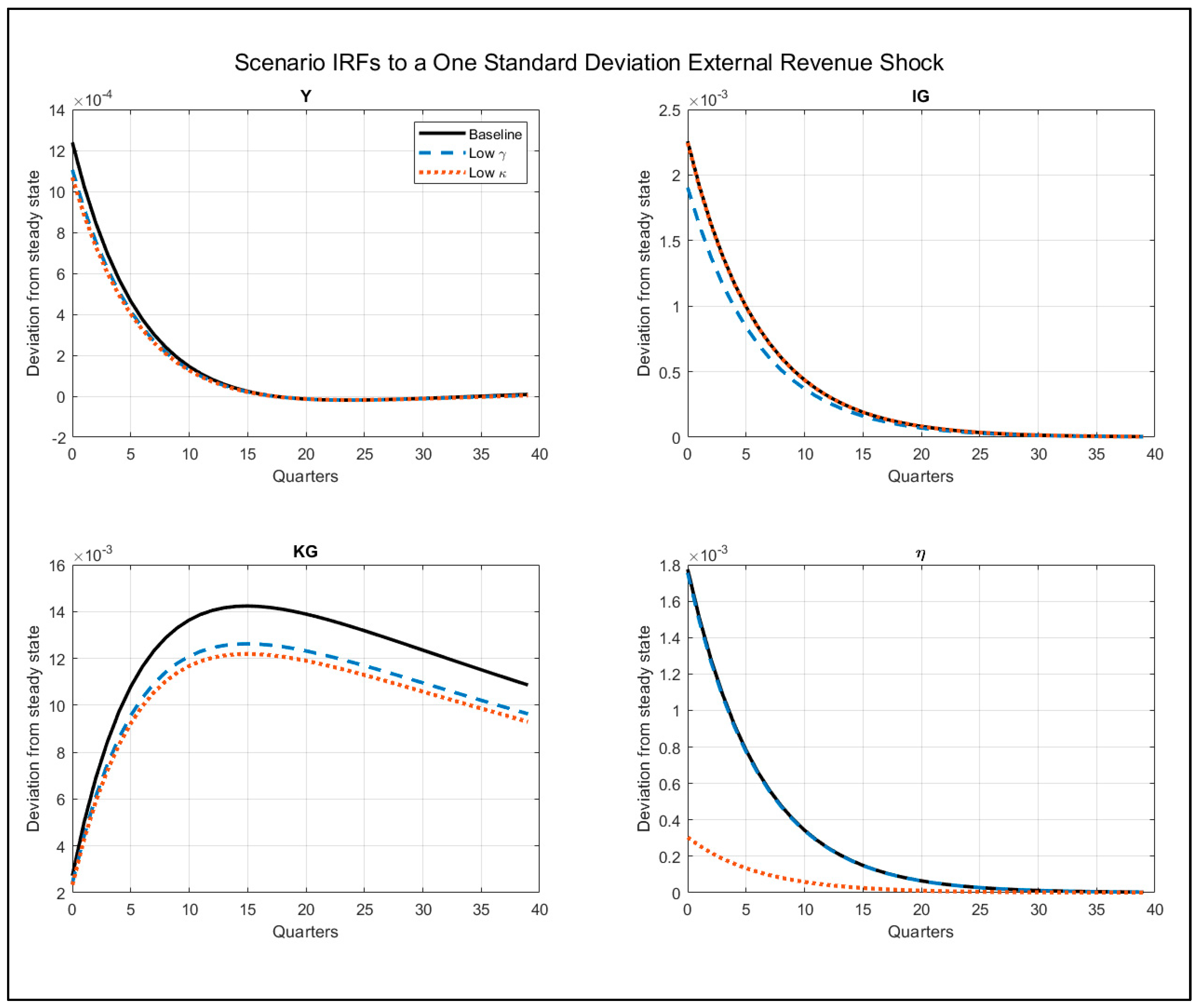

4.2. Scenario Comparison: Lower Fiscal Procyclicality and Lower Institutional Sensitivity

4.3. Simulated Moments and Variance Decomposition

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

5.1. External Shocks, Fiscal Policy, and Business Cycle Amplification

5.2. Public Investment, Capital Accumulation, and Medium-Term Dynamics

5.3. Institutional Constraints and Spending Efficiency

5.4. Policy Implications and Relevance in a Broader Context

5.5. Further Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TFP | Total Factor Productivity |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| DSGE | Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| LAC | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| RBC | Real Business Cycle |

| VAR | Vector Autoregression |

Appendix A. Calibration Strategy and Parameter Justification

Appendix A.1. Preference Parameters

Appendix A.2. Technology and Production Parameters

Appendix A.3. Fiscal Parameters

Appendix A.4. Institutional and Efficiency Parameters

Appendix A.5. Stochastic Processes

Appendix A.6. Summary

References

- Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., Campante, F. R., & Tabellini, G. (2008). Why is fiscal policy often procyclical? Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(5), 1006–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., Roubini, N., & Cohen, G. D. (1997). Political cycles and the macroeconomy. MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A., Buffie, E. F., Pattillo, C., Portillo, R., Presbitero, A. F., & Zanna, L.-F. (2018). Some misconceptions about public investment efficiency and growth. Economica, 86(342), 409–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A., Portillo, R. A., Buffie, E. F., Pattillo, C. A., & Zanna, L.-F. (2012). Public investment, growth, and debt sustainability: Putting together the pieces. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T., Ilzetzki, E., & Persson, T. (2013). Weak states and steady states: The dynamics of fiscal capacity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(4), 205–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2008). How do budget deficits and economic growth affect reelection prospects? Evidence from a large panel of countries. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2203–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrun, X., & Kumar, M. (2007, March 29). Fiscal rules, fiscal councils and all that: Commitment devices, signaling tools or smokescreens? Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2004371 (accessed on 20 December 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Drazen, A. (2000). Political economy in macroeconomics. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, A., & Eslava, M. (2010). Electoral manipulation via expenditure composition: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 92(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). Democracy index 2019: A year of democratic setbacks and popular protest. Economist Intelligence Unit. Available online: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2019/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Eslava, M. (2011). The political economy of fiscal policy: A survey. In Inter-American development bank working paper (No. IDB-WP-211). Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A., Schmitt-Grohé, S., & Uribe, M. (2020). Does the commodity super cycle matter? (No. w27589). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J. A. (2011). A solution to fiscal procyclicality: The structural budget institutions pioneered by Chile (No. w16945). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16945 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Frankel, J. A., Végh, C. A., & Vuletin, G. (2013). On graduation from fiscal procyclicality. Journal of Development Economics, 100(1), 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Albán, F., González-Astudillo, M., & Vera-Avellán, C. (2021). Good policy or good luck? Analyzing the effects of fiscal policy and oil revenue shocks in Ecuador. Energy Economics, 100, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cicco, J., Pancrazi, R., & Uribe, M. (2010). Real business cycles in emerging countries? American Economic Review, 100(5), 2510–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, M., & Perotti, R. (1997). Fiscal policy in Latin America. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 12, 11–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, F. (2000). Political instability and economic growth in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M. D. L. A. (2002). Do changes in democracy affect the political budget cycle? Evidence from Mexico. Review of Development Economics, 6(2), 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1996). Electoral competition and special interest politics. Review of Economic Studies, 63(2), 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., Kangur, A., Papageorgiou, C., & Wane, A. (2014). Efficiency-adjusted public capital and growth. World Development, 57, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilzetzki, E., & Vegh, C. A. (2008, July). Procyclical fiscal policy in developing countries: Truth or fiction? (NBER working paper No. w14191). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1165519 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Klomp, J., & de Haan, J. (2016). Banking risk and regulation: Does one size fit all? Journal of Banking & Finance, 70, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumhof, M., & Laxton, D. (2013). Simple fiscal policy rules for small open economies. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, E. M. (1991). Equilibria under active and passive monetary and fiscal policies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 27(1), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E. G., & Oviedo, P. M. (2006). Fiscal policy and macroeconomic uncertainty in developing countries: The tale of the tormented insurer. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(5), 1029–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 42(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieschacón, A. (2012). The value of fiscal discipline in oil-exporting countries. Journal of Monetary Economics, 59(3), 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, K., & Sibert, A. (1988). Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. Review of Economic Studies, 55(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Grohé, S., & Uribe, M. (2007). Optimal simple and implementable monetary and fiscal rules. Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(6), 1702–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvi, E., & Végh, C. A. (2005). Tax base variability and procyclicality of fiscal policy in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 78(1), 156–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J. L., & Diaz-Kovalenko, I. E. (2022). Oil price shocks, government revenues, and public investment: The case of Ecuador. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4115270 (accessed on 20 December 2025). [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Value | Source/Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discount factor | 0.99 | Long-run real interest rate | |

| Relative risk aversion | 2.0 | Standard DSGE literature | |

| Inverse Frisch elasticity | 1.0 | Standard DSGE literature | |

| Labor disutility parameter | Calibrated | Steady-state labor supply | |

| Capital share | 0.33 | National accounts | |

| Capital depreciation | 0.025 | Quarterly standard | |

| Effective tax rate | 0.18 | Fiscal data (ECB/MEF) | |

| Resource revenue weight | 0.25 | Share of oil revenues | |

| Fiscal procyclicality | 1.1 | Talvi and Végh (2005) | |

| Steady-state efficiency | 1.0 | Normalization | |

| Efficiency elasticity | 0.3 | Drazen and Eslava (2010) | |

| TFP persistence | 0.90 | Output autocorrelation | |

| External shock persistence | 0.85 | Commodity price cycles | |

| TFP shock std. dev. | Calibrated | Output volatility | |

| External shock std. dev. | Calibrated | Revenue volatility |

| Variable | Std. Dev. (A) | AC(1) (A) | Std. Dev. (B) | AC(1) (B) | Std. Dev. (C) | AC(1) (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | 0.105 | 0.905 | 0.106 | 0.905 | 0.106 | 0.905 |

| C | 0.025 | 0.768 | 0.025 | 0.772 | 0.026 | 0.773 |

| I | 0.064 | 0.834 | 0.066 | 0.838 | 0.067 | 0.838 |

| N | 0.009 | 0.331 | 0.009 | 0.277 | 0.009 | 0.263 |

| K | 0.932 | 0.652 | 0.963 | 0.651 | 0.971 | 0.650 |

| W | 0.073 | 0.896 | 0.074 | 0.895 | 0.074 | 0.895 |

| RK | 0.001 | 0.340 | 0.001 | 0.314 | 0.001 | 0.307 |

| R | 0.021 | 0.823 | 0.021 | 0.823 | 0.021 | 0.823 |

| E | 0.023 | 0.823 | 0.019 | 0.823 | 0.023 | 0.823 |

| G | 0.014 | 0.823 | 0.012 | 0.823 | 0.014 | 0.823 |

| IG | 0.009 | 0.823 | 0.008 | 0.823 | 0.009 | 0.823 |

| KG | 0.267 | 0.384 | 0.237 | 0.382 | 0.229 | 0.382 |

| η | 0.007 | 0.823 | 0.007 | 0.823 | 0.001 | 0.823 |

| Variable | eA (%) | eZ (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Y | 99.91 | 0.04 |

| C | 99.37 | 1.08 |

| I | 98.99 | 1.59 |

| N | 99.03 | 2.60 |

| K | 99.36 | 0.87 |

| W | 99.76 | 0.20 |

| RK | 100.07 | 1.27 |

| R | 79.59 | 18.85 |

| E | 79.59 | 18.85 |

| G | 79.59 | 18.85 |

| IG | 79.59 | 18.85 |

| KG | 88.10 | 10.65 |

| η | 79.59 | 18.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diaz-Kovalenko, I.E. External Shocks, Fiscal Transmission Mechanisms, and Macroeconomic Volatility: Evidence from Ecuador. Economies 2026, 14, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies14020036

Diaz-Kovalenko IE. External Shocks, Fiscal Transmission Mechanisms, and Macroeconomic Volatility: Evidence from Ecuador. Economies. 2026; 14(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies14020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaz-Kovalenko, Igor Ernesto. 2026. "External Shocks, Fiscal Transmission Mechanisms, and Macroeconomic Volatility: Evidence from Ecuador" Economies 14, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies14020036

APA StyleDiaz-Kovalenko, I. E. (2026). External Shocks, Fiscal Transmission Mechanisms, and Macroeconomic Volatility: Evidence from Ecuador. Economies, 14(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies14020036