Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Burkina Faso

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the persistence of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic periods?

- Do the potential effects vary across households?

- What are the effects of the spread of the pandemic on food insecurity outcomes?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Empirical Review

- Income losses and shocks in demand;

- Food supply chain disruptions;

- Policy responses: hoarding at the country level (food export bans) and fiscal stimulus.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

3. COVID-19 Measures in Burkina Faso

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Description

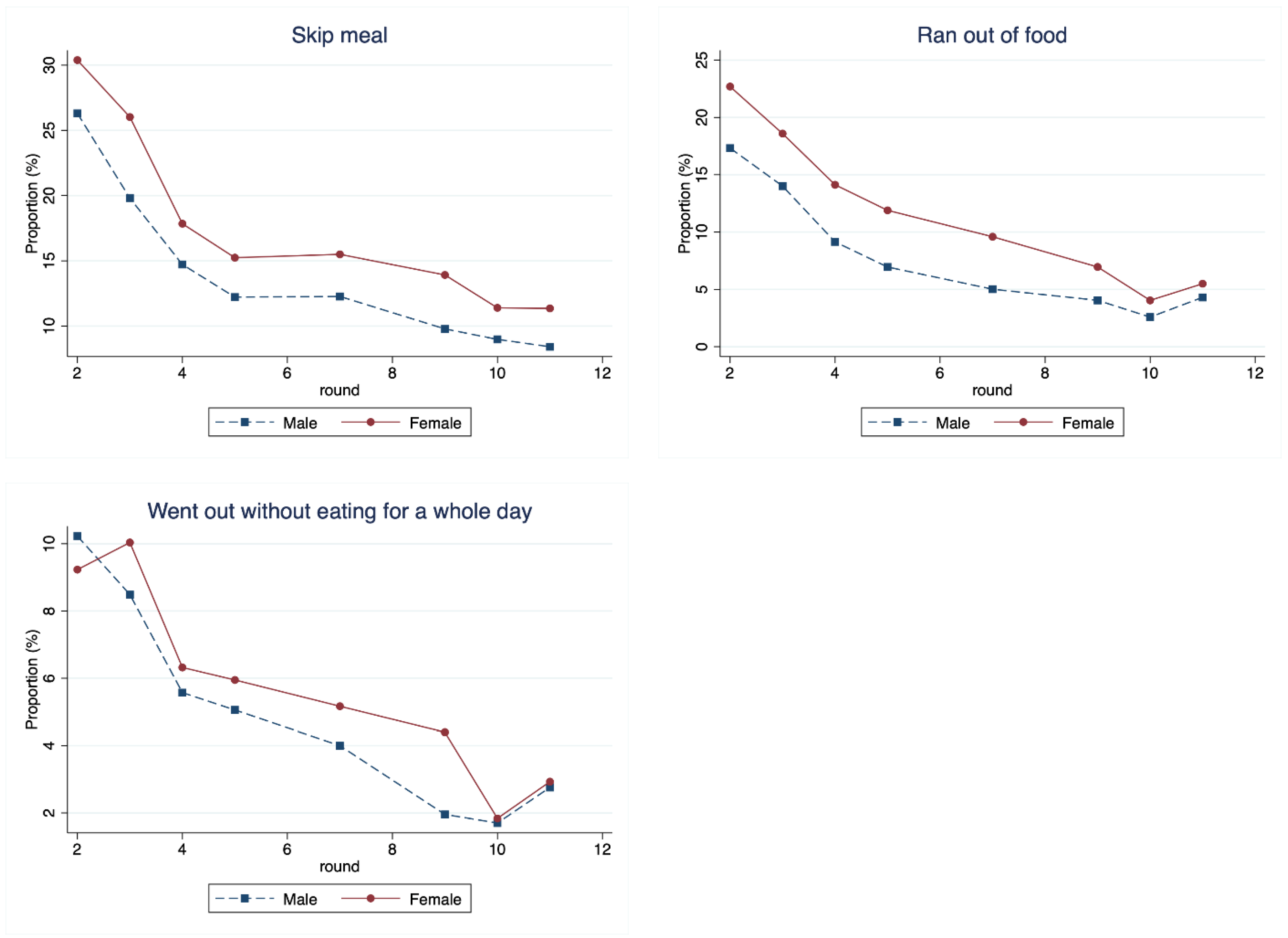

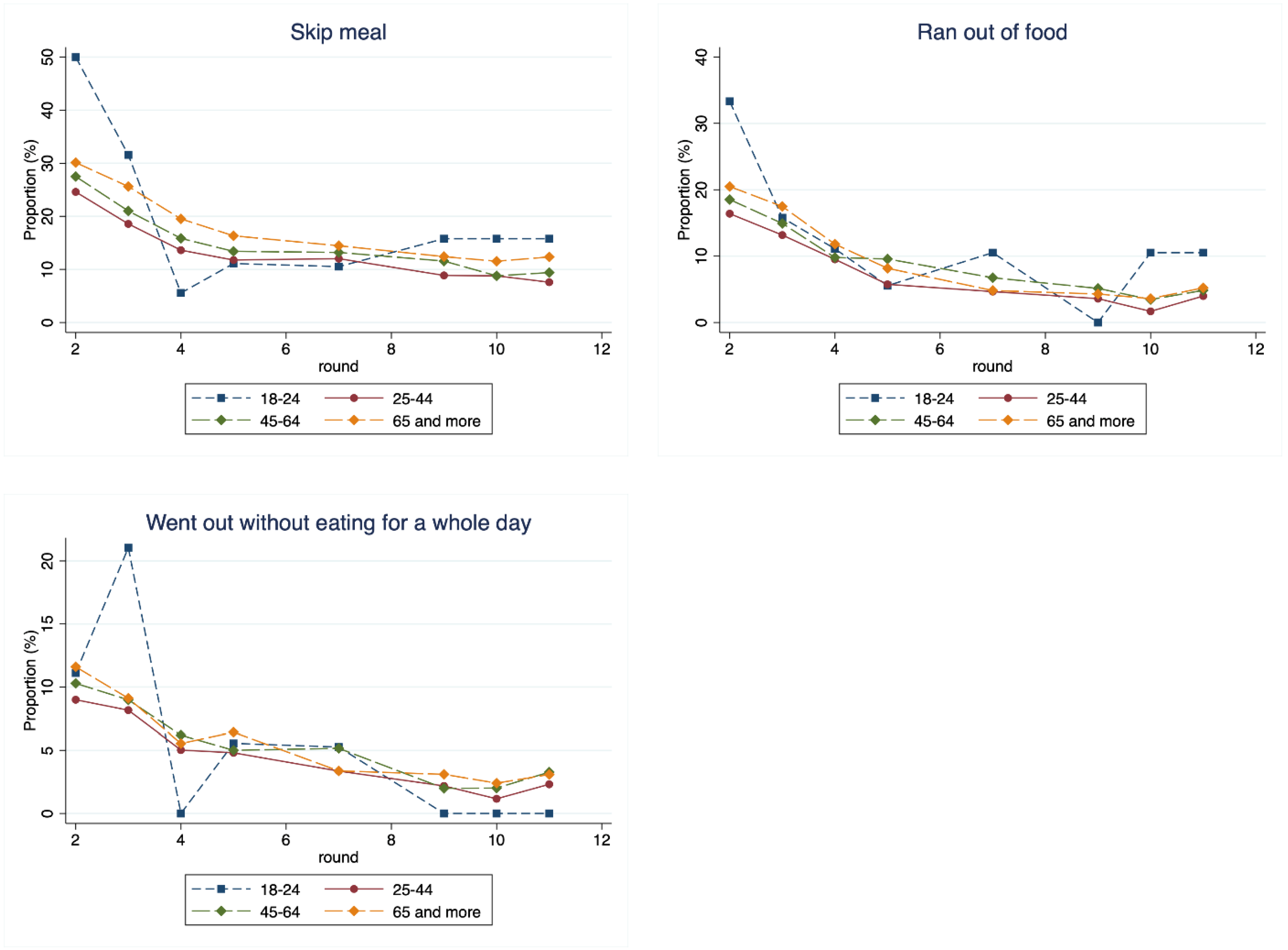

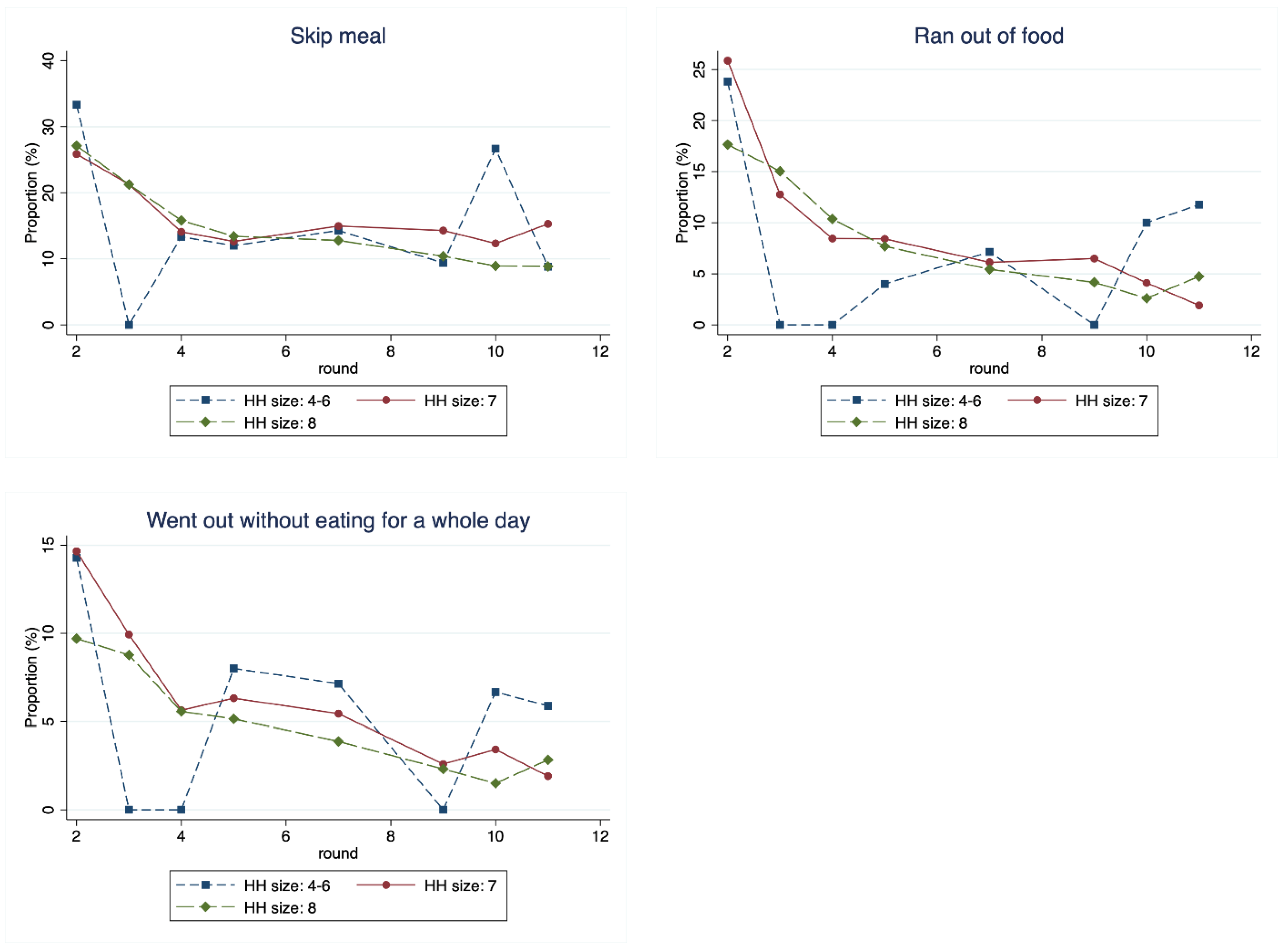

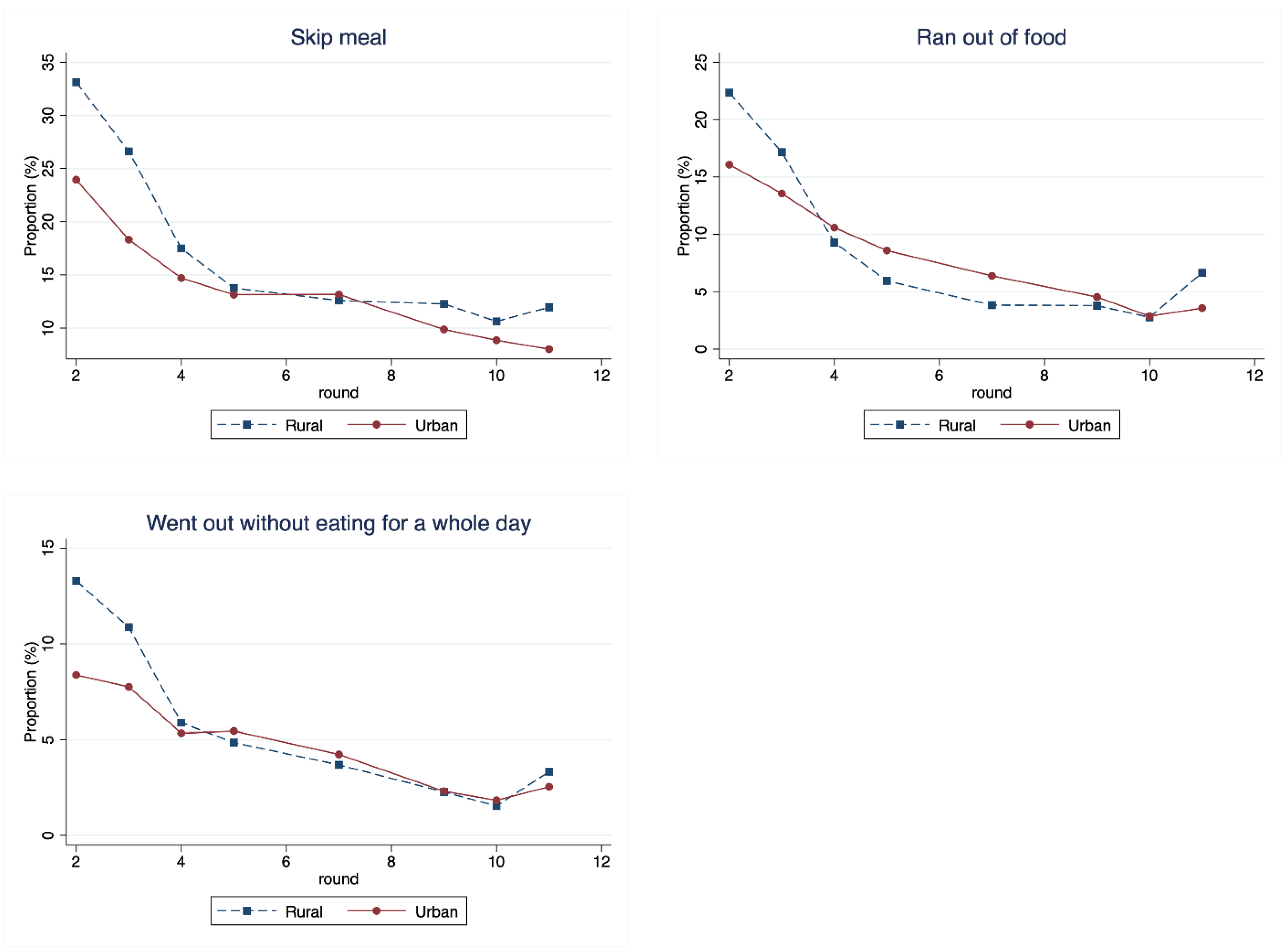

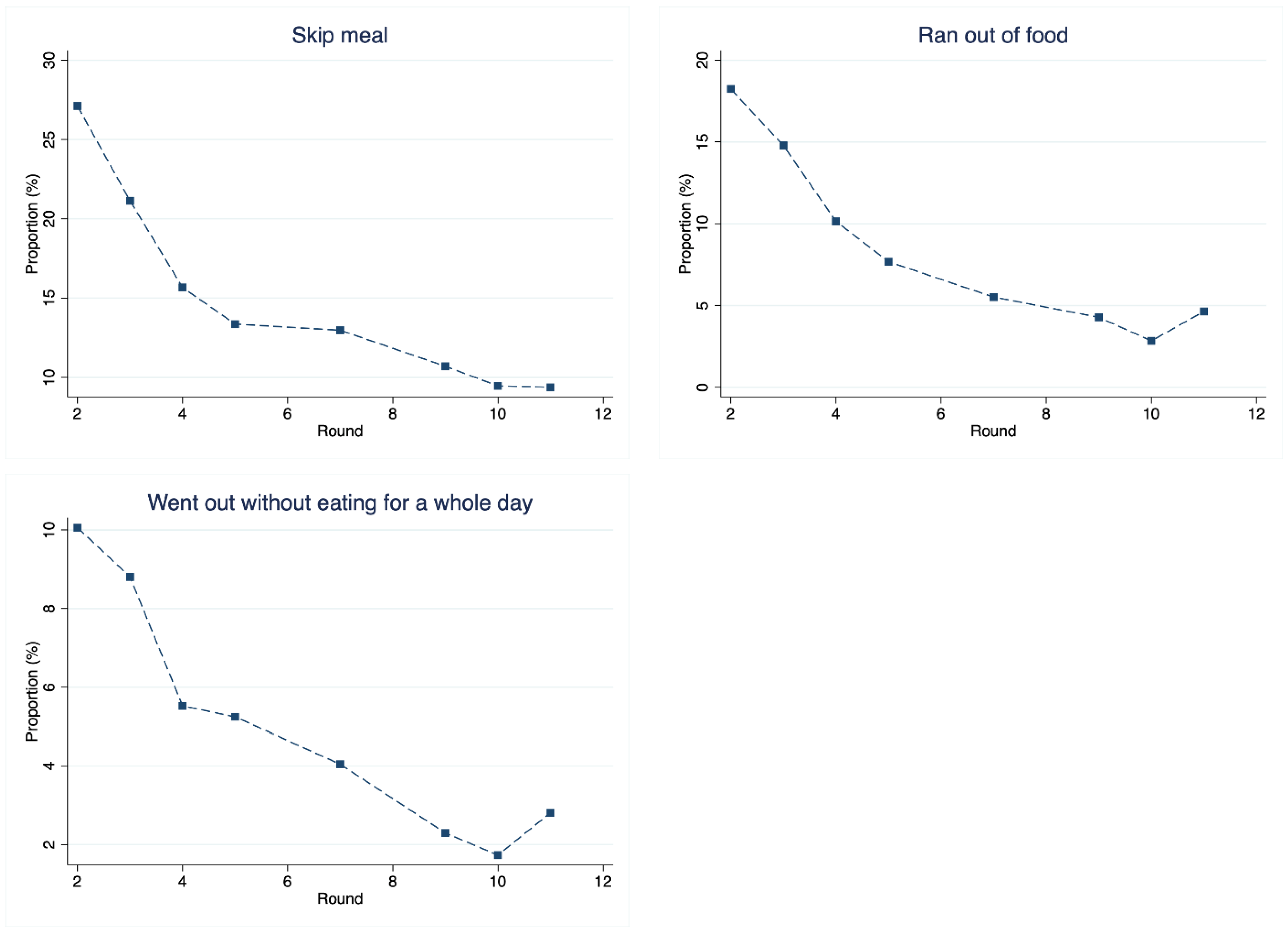

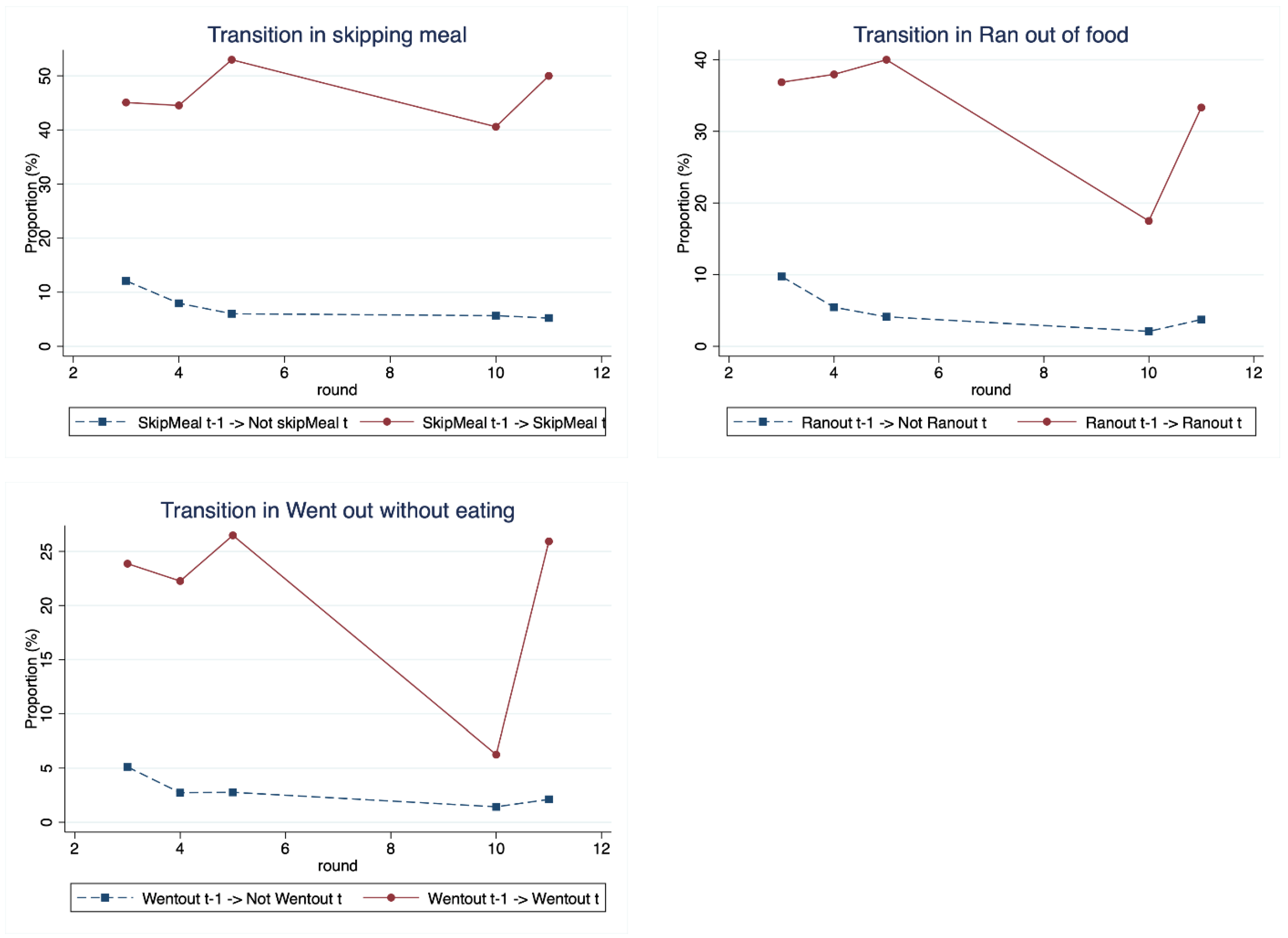

4.2. Food Insecurity Dynamics and Profiles in Burkina Faso

4.3. Empirical Model

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Suggestions for Public Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Please note that respondents in this paper are not household heads, but rather households’ individuals. When surveyed, we asked questions to the respondents’ household members. |

References

- Abay, K. A., Tafere, K., & Woldemichael, A. (2020). Winners and losers from COVID-19: Global evidence from Google Search. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACSS. (2021). Food insecurity crisis mounting in Africa. African Center for Strategic Studies. Available online: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/food-insecurity-crisis-mounting-africa/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Aday, S., & Aday, M. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Quality and Safety, 4(4), 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjognon, G. S., Bloem, J. R., & Sanoh, A. (2021). The coronavirus pandemic and food security: Evidence from Mali. Food Policy, 101, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalu, L. S., & Wang, H. (2023). Does the female-headed household suffer more than the male-headed from Covid-19 impact on food security? Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 12, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akim, Al-mouksit, Ayivodji, F., & Kouton, J. (2024). Food security and the COVID-19 employment shock in Nigeria: Any ex-ante mitigating effects of past remittances. Food Policy, 122, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J., & Khan, W. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural wholesale prices in India: A comparative analysis across the phases of the lockdown. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(4), e2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinsato, A. S. (2021). COVID-19 en Afrique subsaharienne: Analyse des facteurs explicatifs des réponses d’atténuation des effets socioéconomiques. In B. Boudarbat, H. H. Guermazi, & M. B. O. Ndiaye (Eds.), COVID-19: Impacts économiques et sociaux, politiques de riposte et stratégies de résilience (pp. 96–113). Observatoire de la Francophonie Economique (OFE). [Google Scholar]

- Amare, M., Abay, K. A., Tiberti, L., & Chamberlin, J. (2021). COVID-19 and food security: Panel data evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy, 101, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjath-Babu, T. S., Krupnik, T. J., Thilsted, S. H., & McDonald, A. J. (2020). Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Security, 12(4), 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanlade, A., & Radeny, M. (2020). COVID-19 and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of lockdown during agricultural planting seasons. Npj Science of Food, 4(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M. F., & Novak, L. (2017). Contract farming and food security. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 99(2), 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, Z. A., & Korinek, A. (2020). COVID-19 infection externalities: Trading off lives vs. Livelihoods. NBER Working Paper No. 27009. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27009 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Bottan, N., Hoffmann, B., & Vera-Cossio, D. (2020). The unequal impact of the coronavirus pandemic: Evidence from seventeen developing countries. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0239797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiero, C., Viviani, S., & Nord, M. (2018). Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement, 116, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L., Li, T., Wang, R., & Zhu, J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on China’s agricultural trade. China Agricultural Economic Review, 13(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletto, C., Zezza, A., & Banerjee, R. (2013). Towards better measurement of household food security: Harmonizing indicators and the role of household surveys. Global Food Security, 2(1), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, F., Kannan, S., & Kramer, B. (2020). Impacts of a national lockdown on smallholder farmers’ income and food security: Empirical evidence from two states in India. World Development, 136, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J., & Moseley, W. G. (2020). This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(7), 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, S., Béné, C., & Hoddinott, J. (2020). Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security, 12(4), 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenbaum, M. S., Rebelo, S., & Trabandt, M. (2021). The macroeconomics of epidemics. The Review of Financial Studies, 34(11), 5149–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleby, C., Domínguez, I. P., Adenauer, M., & Genovese, G. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global agricultural markets. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, P., Bohle, H.-G., & Stewart, B. (2012). Vulnerability and resilience of food systems. In Food security and global environmental change (pp. 87–97). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo, J. (2020). COVID-19 threatens to starve Africa. BloombergQuint. Available online: https://www.bloombergquint.com/gadfly/covid-19-threatens-to-starve-africa (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- FAO. (2021). Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agriculture, food security and nutrition in Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO. (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world: Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. FAO. [Google Scholar]

- FAO & WFP. (2020). FAO-WFP early warning analysis of acute food insecurity hotspots: July 2020. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Crisis Prevention Network. (2020). Burkina Faso. Available online: https://www.food-security.net/en/datas/burkina-faso/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Fund for Peace. (2020). Fragile states index 2020–Annual report. The Fund for Peace. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, D. (2020). Social safety nets are crucial to the COVID-19 response: Some lessons to boost their effectiveness. In J. Swinnen, & J. McDermott (Eds.), COVID-19 and global food security (pp. 102–105). Chapter 23. Part Seven: Policy responses. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadani, J. D., Hasan, M. I., Baldi, A. J., Hossain, S. J., Shiraji, S., Bhuiyan, M. S. A., Mehrin, S. F., Fisher, J., Tofail, F., & Tipu, S. M. U. (2020). Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: An interrupted time series. The Lancet Global Health, 8(11), e1380–e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K., De Brauw, A., & Abate, G. T. (2021). Food consumption and food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in Addis Ababa. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(3), 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition: Developing effective policy responses to address the hunger and malnutrition pandemic. Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J. (1999). Choosing outcome indicators of household food security. Technical Guide #7. International Food Policy Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- INSD. (2020). COVID-19 impact monitoring at the household level-Burkina Faso. Bulletin n°3. INSD & World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M., Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpman, M., Zuckerman, S., Gonzalez, D., & Kenney, G. M. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is straining families’ abilities to afford basic needs (p. 500). Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Koos, C., Hangoma, P., & Mæstad, O. (2020). Household wellbeing and coping strategies in Africa during COVID-19–Findings from high frequency phone surveys. Chr. Michelsen Institute Report No.4. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P., & Kumar Singh, R. (2022). Strategic framework for developing resilience in Agri-Food Supply Chains during COVID 19 pandemic. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 25(11), 1401–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, D., Martin, W., Swinnen, J., & Vos, R. (2020). COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science, 369(6503), 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, D., Martin, W., & Vos, R. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on global poverty, food security, and diets: Insights from global model scenario analysis. Agricultural Economics, 52(3), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, K., & Tomar, S. (2021). COVID-19 and supply chain disruption: Evidence from food markets in India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(1), 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M., & Riley, E. (2021). Household response to an extreme shock: Evidence on the immediate impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on economic outcomes and well-being in rural Uganda. World Development, 140, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiku, A., Fufa, B., & Tadese, B. (2012). Empirical analysis of the determinants of rural households food security in Southern Ethiopia: The case of Shashemene District. Basic Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Review, 1(6), 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Muche, M., Endalew, B., & Koricho, T. (2014). Determinants of household food security among southwest Ethiopia rural households. Asian Journal of Agricultural Research, 8, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchanji, E. B., Lutomia, C. K., Chirwa, R., Templer, N., Rubyogo, J. C., & Onyango, P. (2021). Immediate impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on bean value chain in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural Systems, 188, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouoba, Y., & Sawadogo, N. (2022). Food security, poverty and household resilience to COVID-19 in Burkina Faso: Evidence from urban small traders’ households. World Development Perspectives, 25, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D., Yang, J., Zhou, G., & Kong, F. (2020). The influence of COVID-19 on agricultural economy and emergency mitigation measures in China: A text mining analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0241167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M., & Zhong, Y. (2020). Rising concerns over agricultural production as COVID-19 spreads: Lessons from China. Global Food Security, 26, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M. (2020). Pandemic policies in poor places. CGD Note (April 24). Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin-Rush, L., Michler, J. D., Josephson, A., & Bloem, J. R. (2022). Food insecurity during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in four African countries. Food Policy, 111, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadogo, N., & Ouoba, Y. (2023). COVID-19, food coping strategies and households resilience: The case of informal sector in Burkina Faso. Food Security, 15, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. D., Kassa, W., & Winters, P. (2017). Assessing food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean using FAO’s food insecurity experience scale. Food Policy, 71, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafiq, A., Fikawati, S., & Gemily, S. C. (2022). Household food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in urban and semi-urban areas in Indonesia. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 41, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsoba, T. A. (2022). Remittances and households’ livelihood in the context of COVID-19: Evidence from Burkina Faso. Journal of International Development, 34(4), 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendall, D. M., Joerin, J., Kopainsky, B., Edwards, P., Shreck, A., Le, Q. B., Krütli, P., Grant, M., & Six, J. (2015). Food system resilience: Defining the concept. Global Food Security, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). (2020). Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/SG-Policy-Brief-on-COVID-Impact-on-Food-Security.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Varshney, D., Roy, D., & Meenakshi, J. V. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on agricultural markets: Assessing the roles of commodity characteristics, disease caseload and market reforms. Indian Economic Review, 55(1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfens, P. J. (2020). Macroeconomic and health care aspects of the coronavirus epidemic: EU, US and global perspectives. International Economics and Economic Policy, 17, 295–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. (2020). COVID-19 will double number of people facing food crises unless swift action is Taken. World Food Program. [Google Scholar]

- Yankey, O., Essah, M., & Amegbor, P. M. (2025). The COVID-19 pandemic and self-reported food insecurity among women in Burkina Faso: Evidence from the performance monitoring for action (PMA) COVID-19 survey data. BMC Women’s Health, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidouemba, P. R., Kinda, S. R., & Ouedraogo, I. M. (2020). Could COVID-19 Worsen Food Insecurity in Burkina Faso? The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1379–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rounds | Start | End |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 June 2020 | 1 July 2020 |

| 2 | 20 July 2020 | 14 August 2020 |

| 3 | 12 September 2020 | 21 October 2020 |

| 4 | 6 November 2020 | 2 December 2020 |

| 5 | 9 December 2020 | 30 December 2020 |

| 6 | 15 January 2021 | 1 February 2021 |

| 7 | 12 February 2021 | 2 March 2021 |

| 8 | 13 March 2021 | 1 April 2021 |

| 9 | 20 April 2021 | 4 May 2021 |

| 10 | 25 May 2021 | 15 June 2021 |

| 11 | 28 June 2021 | 20 July 2021 |

| Variables | Definition and Measure | Mean | St.Dev | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Skipped a meal | 1 if the household skipped a meal; 0 otherwise | 14.92 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Ran out of food | 1 if the household ran out of food; 0 otherwise | 8.46 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Went without eating | 1 if a member of the household went without eating; 0 otherwise | 5.03 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | 1 if individual is a female; 0 otherwise | 15.60 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Age in years | 47.83 | 13.909 | 18 | 102 |

| Age groups | |||||

| 18–24 group | 1 if the individual is aged 18–24 years | 0.97 | - | 0 | 1 |

| 25–44 group | 1 if the individual is aged 25–44 years | 40.56 | - | 0 | 1 |

| 45–64 group | 1 if the individual is aged 45–64 years | 36.59 | - | 0 | 1 |

| 65+ group | 1 if the individual is aged 65 or more | 21.18 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Household size | Number of household members | 7.89 | 0.354 | 4 | 8 |

| Household size classes | |||||

| 4–6 members | 1 if household has between 4 and 6 members in total | 1.29 | - | 0 | 1 |

| 7 members | 1 if household has 7 members in total | 7.26 | - | 0 | 1 |

| 8 members | 1 if household has 8 members in total | 91.43 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Urban | 1 if the household lives in urban area; 0 if the household lives in rural area | 65.80 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Farm activities | 1 if household is involved in farm (agriculture) activities; 0 if involved in non-farm activities | 64.26 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Sample size | 8144 | - | |||

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Groups | Dependent Variable: Food Insecurity Indicator in Period t Given Insecurity in a Previous Period | |||

| Skipped a Meal, Period t − 1 | Ran out of Food, Period t − 1 | Went Without Food, Period t − 1 | ||

| Overall | Constant | 0.224 * (0.127) | −0.074 (0.101) | 0.021 (0.081) |

| 0.368 *** (0.017) | 0.280 *** (0.019) | 0.253 * (0.025) | ||

| R2 | 0.7129 | 0.5497 | 0.4974 | |

| No. observations | 8144 | 8144 | 8144 | |

| Male | Constant | 0.225 * (0.136) | −0.015 (0.113) | 0.051 (0.092) |

| 0.359 *** (0.018) | 0.261 *** (0.022) | 0.240 *** (0.027) | ||

| R2 | 0.7229 | 0.6212 | 0.6243 | |

| No. observations | 6858 | 6858 | 6858 | |

| Female | Constant | 0.280 (0.391) | −0.377 * (0.202) | −0.196 (0.121) |

| 0.407 *** (0.040) | 0.352 *** (0.040) | 0.313 *** (0.064) | ||

| R2 | 0.5545 | 0.6212 | 0.6243 | |

| No. observations | 1286 | 1286 | 0.1286 | |

| (b) | ||||

| Age Group | Dependent Variable: Food Insecurity Indicator in Period t Given Insecurity in a Previous Period | |||

| Skipped Meal, Period t − 1 | Ran out of Food, Period t − 1 | Went Without Food, Period t − 1 | ||

| 18–24 | Constant | −0.945 (0.848) | 0.733 (0.502) | 0.612 (0.696) |

| 0.135 (0.098) | 0.221 (0.150) | 0.005 (0.101) | ||

| R2 | 0.5545 | 0.6807 | 0.3435 | |

| No. observations | 91 | 91 | 91 | |

| 25–44 | Constant | 0.381 ** (0.180) | −0.020 (0.119) | 0.155 (0.122) |

| 0.358 *** (0.027) | 0.220 *** (0.029) | 0.209 *** (0.039) | ||

| R2 | 0.5545 | 0.6807 | 0.3435 | |

| No. observations | 3669 | 3669 | 3669 | |

| 45–64 | Constant | −0.100 (0.164) | −0.174 (0.203) | −0.071 (0.140) |

| 0.362 *** (0.024) | 0.321 *** (0.030) | 0.304 *** (0.041) | ||

| R2 | 0.5545 | 0.6807 | 0.3435 | |

| No. observations | 3341 | 3341 | 3341 | |

| 65+ | Constant | 0.401 (0.443) | 0.075 (0.300) | −0.173 (0.149) |

| 0.391 *** (0.039) | 0.347 *** (0.045) | 0.200 *** (0.043) | ||

| R2 | 0.5545 | 0.6807 | 0.3435 | |

| No. observations | 1194 | 1194 | 1194 | |

| (c) | ||||

| Household Size | Dependent Variable: Food Insecurity Indicator in Period t Given Insecurity in a Previous Period | |||

| Skipped Meal, Period t − 1 | Ran out of Food, Period t − 1 | Went Without Food, Period t − 1 | ||

| 4–6 | Constant | −0.011 (0.438) | 0.117 (0.282) | 0.127 (0.315) |

| −0.407 (0.263) | −0.163 (0.278) | −0.266 (0.351) | ||

| R2 | 0.6861 | 0.5789 | 0.5232 | |

| No. observations | 39 | 39 | 39 | |

| 7 | Constant | 0.440 *** (0.133) | 0.154 (0.173) | 0.305 ** (0.152) |

| 0.377 *** (0.077) | 0.198 *** (0.077) | 0.179 ** (0.084) | ||

| R2 | 0.6861 | 0.5789 | 0.5232 | |

| No. observations | 376 | 376 | 376 | |

| 8 | Constant | 0.017 (0.023) | 0.008 (0.016) | −0.008 (0.012) |

| 0.362 *** (0.017) | 0.282 *** (0.020) | 0.257 *** (0.026) | ||

| R2 | 0.6861 | 0.5789 | 0.5232 | |

| No. observations | 7729 | 7729 | 7729 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikiema, P.R.; Dedewanou, F.A. Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Burkina Faso. Economies 2025, 13, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13060155

Nikiema PR, Dedewanou FA. Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Burkina Faso. Economies. 2025; 13(6):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13060155

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikiema, Pouirkèta Rita, and Finagnon Antoine Dedewanou. 2025. "Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Burkina Faso" Economies 13, no. 6: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13060155

APA StyleNikiema, P. R., & Dedewanou, F. A. (2025). Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Burkina Faso. Economies, 13(6), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13060155