Abstract

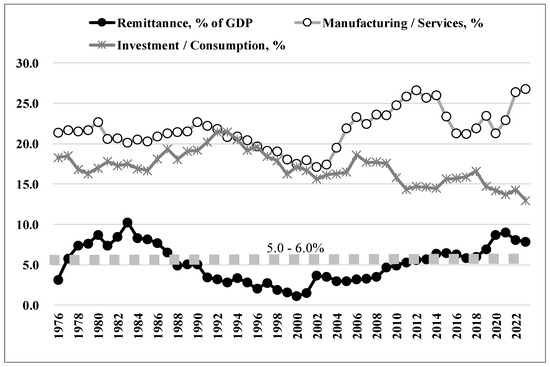

Pakistan is one of the largest recipients of remittances globally and has substantial remittance inflow fluctuations; thus, finding the remittance–gross domestic product (GDP) ratio threshold is expedient. This study examined the macroeconomic impacts of emigrant remittances in Pakistan using a vector autoregressive estimation framework and investigated the threshold of the remittance–GDP ratio that has real effects on the economy in terms of Dutch Disease and capital accumulation. The empirical results showed that, regarding the Dutch Disease effect, a remittance–GDP ratio greater than 6% leads to a decrease in the manufacturing–services ratio, whereas as for the capital accumulation effect, a remittance–GDP ratio greater than 5% leads to a decrease in the investment–consumption ratio. These outcomes suggested that emigrants’ remittance inflows in Pakistan that exceed certain levels relative to the GDP aggravate industrialisation (Dutch Disease effect) and capital accumulation.

1. Introduction

International migrant remittances have greatly impacted foreign currency earnings for many developing and emerging market economies. According to World Bank data, the total remittances received by low- and middle-income economies increased by approximately 190 times, from USD 3.3 billion in 1975 to USD 627.1 billion in 2023, while their gross domestic product (GDP) only grew by 33 times during the same period. Thus, the average remittance–GDP ratio in these economies rose from 0.29% in 1975 to 1.67% in 2023.

These increasing trends in remittance inflows to developing and emerging market economies have micro- and macroeconomic effects on their recipient economies. At the household level, received remittances have positive impacts, such as increased income and standard of living and a reduced poverty incidence. Many empirical studies have revealed the positive impact of remittances on household income, poverty alleviation, educational achievements, and entrepreneurship (Bare et al., 2022; Huay & Bani, 2018; Yang, 2005; etc.). From a macroeconomic perspective, some studies argue that recipient economies boost the momentum of economic growth through capital accumulation from remittance inflows (Azam & Raza, 2016; etc.). Other studies, however, demonstrated negative effects of remittance inflows, typically the “Dutch Disease” effect, where tradable manufacturing sectors were crowded out by non-tradable service sectors through real exchange rate appreciation (Fisera & Workie Tiruneh, 2023; etc.). To date, the empirical outcomes of the macroeconomic effects of remittance inflows have been inconclusive. Thus, the remittance issue has attracted attention from both academics and policymakers who aim to enrich the empirical evidence and formulate appropriate policies for managing received remittances.

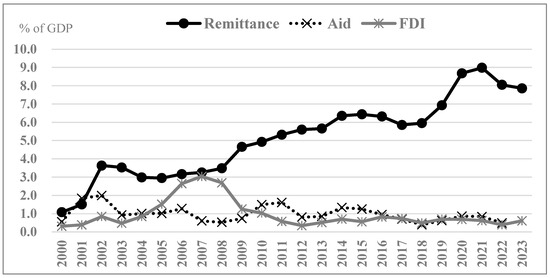

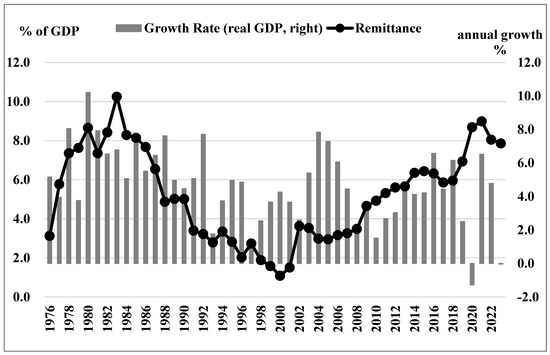

This study examined the macroeconomic impacts of emigrant remittances, with a focus on the Pakistani economy, using a vector auto-regression (VAR) estimation framework. Moreover, the study investigated the threshold of ratio of received remittance relative to gross domestic product (GDP), which has real effects on the economy in terms of Dutch Disease and capital accumulation. Finding this threshold is significant because Pakistan is one of the largest recipients of remittances in the world, and its remittance inflows have experienced substantial long-term fluctuations together with economic growth. Table 1 shows that Pakistan received USD 26.6 billion in remittances in 2023, which accounted for 4.2% of the total remittances received by low- and middle-income economies, and was ranked fifth among these countries. Pakistan has a remittance–GDP ratio of 7.9%, which is higher than the average low- and middle-income economies ratio (1.6%). Figure 1 indicates that the remittance–GDP ratio has exceeded the net foreign aid–GDP ratio and net inward foreign direct investment–GDP ratio in Pakistan since the 2010s. Long-term time-series observations over decades have enabled us to gain insight into the trends in the macroeconomic impacts of remittance inflows in Pakistan. Figure 2 shows the substantial fluctuations of the remittance–GDP ratio from 10.2% in 1983 to 1.1% in 2000, and the Pakistani nexus growth rate with GDP presents some complexity. In some phases, the remittance–GDP ratio was correlated with GDP growth, but not in other phases. These fluctuations and complexities motivated us to investigate the threshold of the remittance–GDP ratio above which, there would be significant impacts on the Pakistani macroeconomy. As there have been few prior studies examining this type of threshold, the main aim of this study was to close this research gap by identifying the remittance threshold, with a focus on the Pakistani economy.

Table 1.

Major recipients of international emigrant remittances in 2023.

Figure 1.

Remittance, Aid, and FDI as a percentage of GDP in Pakistan. Sources: Authors’ estimation. Note: GDP, gross domestic product; FDI, foreign direct investment.

Figure 2.

Trends in remittance–GDP ratio and GDP growth rate in Pakistan. Sources: Authors’ estimation. Note: GDP, gross domestic product.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The next section reviews the literature on the micro- and macroeconomic impacts of remittance inflows, with a focus on Dutch Disease and capital accumulation effects from a macroeconomic perspective. This is followed by an empirical analysis of the remittance impacts in Pakistan, including descriptions of the theoretical framework, data for key variables, and methodologies for VAR estimation. Subsequently, the estimation outcomes are provided, along with their interpretation. The final section summarises the findings and conclusions, and highlights the implications and limitations of the study.

2. Literature Review

The literature on the economic impact of emigrants’ remittance inflows is summarised in Table 2. Most empirical studies have focused on microeconomic aspects, such as poverty alleviation and household income. Specifically, the positive effects of remittances for recipient developing economies were identified based on human capital formation such as school enrolment (Acharya & Leon-Gonzalez, 2014; Azizi, 2018; Bare et al., 2022; Bouoiyour & Miftah, 2016; Gorlich et al., 2007; Hines & Simpson, 2019; Koska et al., 2013; Salas, 2014), improvements in poverty, health, and income distribution (Acosta et al., 2008; Adams & Page, 2005; Berloffa & Giunti, 2019; Huay & Bani, 2018; Khan et al., 2021; Shirazi et al., 2018; Siddiqui & Kemal, 2006), financial development (Aggarwal et al., 2006; Chowdhury, 2011; Pal, 2023), and entrepreneurship of micro-enterprises (Woodruff & Zenteno, 2001; Yang, 2005).

Table 2.

List of reviewed literature.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, theoretical frameworks have demonstrated two contrasting hypotheses: the negative impacts of received remittances due to the Dutch Disease effect and the positive impacts due to the capital accumulation effect. The Dutch Disease hypothesis in terms of “capital inflows” in small open economies has been generally represented by the Salter–Swan–Corden–Dornbusch model, which was initially proposed by Corden and Neary (1982). This model can also be applied to examine the economic impact of emigrant remittances, as they constitute a major component of capital inflows. Sachs (2007) proposed the capital accumulation hypothesis as a counterargument against the long-term Dutch Disease effect through public investment. Bourdet and Falck (2006) combined the Dutch Disease and capital accumulation hypotheses into a theoretical model for explaining the macroeconomic effects of remittance inflows—this study follows the model developed by Bourdet and Falck (2006), as discussed later in text.

There have been fewer empirical studies on macroeconomic impacts than on the microeconomic impacts of remittance inflows. Moreover, the empirical outcomes have been inconclusive, particularly regarding the effects of Dutch Disease or capital accumulation that would be dominant macroeconomic impacts. First, the Dutch Disease effect of received remittances was identified in numerous samples of developing, emerging, and transition countries (e.g., Daway-Ducanes, 2019; Fisera & Workie Tiruneh, 2023; Lartey et al., 2012), in a group of Asian developing countries (e.g., Basnet et al., 2019; Jongwanich & Kohpaiboon, 2019; Phuc et al., 2020; Roy & Dixon, 2016), and in individual countries such as El Salvador (Acosta et al., 2009), Pakistan (Makhlouf & Mughal, 2013), Bangladesh (Chowdhury & Rabbi, 2014), and Nigeria (Periola, 2025). Some studies have argued that the Dutch Disease effect is weakened by factors such as trade openness, the floating exchange rate regime, and financial development (Chowdhury & Rabbi, 2014; Fisera & Workie Tiruneh, 2023; Jongwanich & Kohpaiboon, 2019; Phuc et al., 2020; Roy & Dixon, 2016). Second, the positive remittance effect, including capital accumulation through overcoming Dutch Disease, has been verified in numerous countries (e.g., Azam & Raza, 2016; Borja, 2014; Destrée et al., 2021; Fayad, 2011; Ito, 2019), Sub-Saharan Africa (Baafi & Asiedu, 2025), four African countries (Yiheyis & Woldemariam, 2016), the Caribbean Islands (Ait Benhamou & Cassin, 2021), Cape Verde (Bourdet & Falck, 2006), and Bangladesh (Taguchi & Shammi, 2018).

Thus, an academic contribution of this study is that it enriches the evidence on the macroeconomic impacts of remittance inflows, for which, previous studies have produced mixed results. The case of Pakistan was examined by Makhlouf and Mughal (2013), who argued for the existence of the Dutch Disease effect from received remittances using Bayesian analysis sampling for the period of 1980–2008. However, it is essential to update the analysis and apply a different VAR method to address the endogeneity problem among the variables. Another contribution is the investigation of the threshold of the remittance–GDP ratio that has real effects on macroeconomies. There have been a limited number of previous studies investigating this threshold. Jongwanich and Kohpaiboon (2019) demonstrated that remittances generate negative and significant impacts on economic growth only if they reach 10% of GDP or higher in Asia and Pacific developing countries. Since Pakistan has been one of the largest recipients of remittances and has experienced substantial remittance inflow fluctuations together with its economic growth, this study examined the critical threshold of the remittance–GDP ratio in Pakistan.

3. Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Framework

This subsection describes the theoretical framework based on Bourdet and Falck (2006) for analysing the Dutch Disease and capital accumulation effects of capital inflows (remittance inflows in this study) in small open economies.

The Dutch Disease effects were decomposed into a “spending effect” and “resource movement effect”. When the remittance inflows increase, the spending effect also increases: a remittance gain increases disposable income, thereby causing an increase in spending and demand in the economy, assuming positive income elasticity, which results in excess demands for non-tradables due to limited supplies while tradables can be imported, increasing the relative price of non-tradables compared to tradable goods (appreciation of the real exchange rate). This subsequently causes the resource movement effect: a hike in the relative price of non-tradable goods encourages a move of mobile production factors from tradable sectors to non-tradable sectors due to increased compensation to non-tradable sectors.

In the long term, an increase in remittance inflows will boost capital accumulation through its effect on domestic savings and investments. However, the effect depends on the motivations of the emigrants to remit: if self-interest is the motivator for emigrants, they tend to save their remittances, for instance, in their bank accounts for favourable returns; however, if altruism is the motivator, they remit to support their families and relatives in the country of origin, who are inclined to consume rather than save. Capital accumulation increases the production of both tradable and non-tradable goods.

The subsequent sections test theoretical hypotheses using empirical tests and conduct the VAR model estimation.

3.2. Data for Key Variables

First, this subsection identifies the economic variables for the VAR model estimation in Pakistan. For all variables, we sampled the time-series annual data for the maximum period with available data: 1976–2023. As the purpose of the analysis is to examine the economic impact of remittance inflows based on the theoretical framework discussed above, the estimation considers the following five variables: remittance–GDP ratio (roy), real exchange rate (rer), manufacturing–services ratio (mos), investment–consumption ratio (ioc), and real GDP per capita (pcy). Regarding the data sources, the remittance–GDP ratio and indexes of consumer and wholesale prices (for computing the real exchange rate) were retrieved from World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank.1 The manufacturing–services ratio (dividing “manufacturing in value-added term” by “services in value-added term”), investment–consumption ratio (dividing “gross fixed capital formation” by “final consumption expenditure”), and real GDP per capita were taken from the UNCTAD Stat dataset.2 A list of the variables and data sources is presented in Table 3, and their descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4. The descriptive statistics, including the minimum and maximum values, indicated that the sample data for each variable are devoid of outliers.

Table 3.

List of variables and data sources.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

The real exchange rate and manufacturing service ratios were used to examine the Dutch Disease effect. The real exchange rate in this study was represented as the consumer price index divided by the wholesale price index. This ratio can be a proxy for the real exchange rate because the theoretical framework describes the real exchange rate as the price of non-tradables relative to that of tradables: consumption prices cover tradable (goods) and non-tradable (services) sectors, whereas wholesale prices only target the tradable (goods) sector. The manufacturing–services ratio is a proxy for the tradable to non-tradable production ratio (Lartey et al., 2012). In the combination of the remittance–GDP ratio and real exchange rate, the “spending effect” in the Dutch Disease effect could be identified if the real exchange rate was positively affected by the remittance–GDP ratio. The Dutch Disease effect would be followed by the “resource movement effect” if the manufacturing–services ratio was negatively influenced by the real exchange rate. The investment–consumption ratio was used to examine the capital accumulation effect presented by Bourdet and Falck (2006). If the ratio is positively affected by the remittance–GDP ratio, a capital accumulation effect is suggested. The real GDP per capita is included as a control variable in the estimation since the manufacturing–services ratio may also be affected by the development stage of an economy according to the Petty–Clark law (Clark, 1940).

A dummy variable, attached to the coefficients of the remittance–GDP ratio, is a critical variable that was introduced to indicate the threshold of the ratio for different and asymmetrical impacts on the Pakistani macroeconomy. Thresholds can be established using several methods, including quantiles and data-driven estimations. This study utilised two distinct thresholds due to the constrained time-series data. Specifically, the thresholds were established at two intermediate positions of the remittance–GDP ratio: 5% (dum5) and 6% (dum6), situated between the maximum (1.3% in 2000) and minimum (10.2% in 1983) in Pakistan. Establishing these intermediate points enables the division of the complete sample (48 year points) into manageable segments: 28 (upper) versus 20 (lower) year points at the 5% threshold, and 20 (upper) versus 28 (lower) year points at the 6% threshold. The dummy variable assumes a value of one when the remittance–GDP ratios exceed the thresholds of 5% or 6%.

Figure 3 displays an overview of the three key variables—the remittance–GDP, manufacturing–services, and investment–consumption ratios—in Pakistan for 1976–2023. While the remittance–GDP ratio indicates substantial fluctuations, its relationship with the manufacturing–services and investment–consumption ratios represent complexities and asymmetries. This implies the existence of a threshold for the remittance–GDP ratio that produces different macroeconomic effects. The observation should be statistically tested in a more sophisticated manner, that is, using the VAR model estimation and incorporating the threshold, as discussed below.

Figure 3.

Overview on key variables in Pakistan. Sources: Authors’ estimation. Note: GDP, gross domestic product.

3.3. Data Properties

Before conducting the VAR model estimation, we investigated the data’s stationarity by employing a unit root test for each variable. The unit root test assesses the null hypothesis that each variable, in its level form, possesses a unit root. The test equation is specified to include either an intercept, or both an intercept and a trend. This study initially performed the standard tests: the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP) tests, and furthermore employed the Ng and Perron test (Ng & Perron, 2001) due to its superior size and power compared to the ADF and PP tests. The Ng and Perron test constructs four test statistics: modified forms of the Phillips–Perron statistics (MZa and MZt), Bhargava’s (1986) statistic (MSB), and the point-optimal statistic (MPT). Table 5 reports the test results for the data for all five variables: roy, rer, mos, ioc, and pcy. The Ng and Perron test consistently denied the presence of a unit root in levels under the “trend and intercept” specification at the conventional significance level of over 95%, although the ADF and PP tests did not consistently reject it; hence, the level data did not exhibit any significant issues regarding stationarity. Thus, we used the level data of all five variables for the VAR model estimation.

Table 5.

Ng and Perron unit root tests.

3.4. VAR Model

Our decision to implement a VAR model for the impact analysis of remittances was motivated by the factors discussed below. In this study, the variables of remittances, manufacturing, and capital accumulation were interdependent. As a result, the endogeneities of the variables would result in biased and inconsistent estimators in single-equation regressions. Instead, a VAR model permits endogeneity among the estimation variables and allows the data to establish the causality between the targeted variables. Furthermore, the dynamic responses of variables to exogenous disturbances can be traced over time using a VAR model. The model equation is as follows:

where yt is a column vector of the endogenous variables with year t, that is, yt = (roy, roy × dum5(or 6), mos), which was used to examine the total Dutch Disease effect, and yt = (roy, roy × dum5(or 6), ioc), which was used to examine the capital accumulation effect. The former vector for the Dutch Disease analysis was further decomposed into yt = (roy, roy × dum5(or 6), rer) to examine the “spending effect”, and yt = (rer, rer × dum5(or 6), mos) to examine the “resource movement effect”. For these estimations for the decomposed Dutch Disease effects, the sample period was restricted to 1976–2019 due to the extraordinary price increases that have occurred since 2020 (the onset of COVID-19), which have influenced the real exchange movement in an irregular manner. The other vectors are as follows: zt is the control variable of the real GDP per capita (pcy); μ is a constant vector; V1 and V2 are coefficient matrices; yt-i is a vector of the lagged endogenous variables; and εt is a vector of the random error terms in the system. Regarding the lag interval, the equation takes a one-year lag length (i = 1), following the Akaike and Schwarz information criteria, with three-year maximum lags under a limited number of time-series data points. Based on the specifications above, the analysis estimated the VAR model and then examined the Granger causality and impulse responses among the endogenous variables.

yt = μ + V1 yt-1i + V2 zt + εt

4. Results and Discussion

Table 6 reports the estimation outcomes of the VAR model for examining the Dutch Disease effect, and Table 7 reports the estimation outcomes of the VAR model for examining capital accumulation effects. Both contain two cases where the remittance–GDP ratios are divided using 5% and 6% thresholds. Table 8 presents the Granger causality test results, and Table 9 presents accumulated impulse responses based on the VAR model estimations.

Table 6.

Estimated VAR model for examining Dutch Disease effect.

Table 7.

Estimated VAR model for examining capital accumulation effect.

Table 8.

Granger causality tests.

Table 9.

Accumulated impulse responses to one-precent-point shock.

The Granger causalities on the Dutch Disease effect presented in Table 8, which were based on the estimated VAR model in Table 6—especially concerning the causality from the remittance–GDP ratio (roy) to the manufacturing–services ratio (mos) as the total effect of the Dutch Disease—occurred using the 6% threshold, but not the 5% threshold; a negative causality from the cross-term of roy×dum to mos was identified at the 99% level of significance. This negative causality indicates that an increase in the remittance–GDP ratio leads to a decrease in the manufacturing–services ratio as the total Dutch Disease effect when the remittance–GDP ratio exceeds the 6% threshold. Focusing on the case of the 6% threshold, the total Dutch Disease effect can be further decomposed into the spending and resource movement effects. Both effects were detected as expected because the positive causality from roy×dum6 to the real exchange rate (rer) (representing the spending effect) and the negative causality from rer×dum6 to mos (representing the resource movement effect) were confirmed at the 95% and 90% significance levels, respectively. However, the weak significance levels for the spending and resource-movement effects might result from using the ratio of consumer to wholesale prices ratio as a proxy for the real exchange rate.

The Granger causality on the capital accumulation effect in Table 8 based on the estimated VAR model in Table 7 occurred with the 5% threshold but not with the 6% threshold—a negative causality from the cross-term of the remittance–GDP ratio (roy×dum) to the investment–consumption ratio (ioc) was identified at the 95% level of significance. This indicates that an increase in the remittance–GDP ratio leads to a decrease in the investment–consumption ratio when the remittance–GDP ratio exceeds the 5% threshold.

The impulse response analysis in terms of the accumulated response to a one-percent-point shock over ten-year horizons in Table 9 focused on the two cases where Granger causalities were strongly detected: the negative causality from roy×dum6 to mos and from roy×dum5 to ioc. The Dutch Disease effect for remittance–GDP ratios over the 6% threshold was confirmed by the consecutive negative responses of the manufacturing–services ratio (mos) to the shock of remittance–GDP ratios beyond the 6% threshold (roy×dum6) at a conventional significance level: a one-percent-point increase in the remittance–GDP ratio led to a decrease in the manufacturing–services ratio by 0.2–0.3% points for five years. The negative capital accumulation effect of remittance–GDP ratios over the 5% threshold was also verified by the consecutive negative responses of the investment–consumption ratio (ioc) to the shock of remittance–GDP ratios above the 5% threshold (roy×dum5): a one-percent-point increase in the remittance–GDP ratio led to a decrease in the investment–consumption ratio by 0.2–0.3% points for six years.

Overall, emigrants’ remittance inflows in Pakistan, if they exceed certain levels relative to the GDP, aggravate industrialisation (the Dutch Disease effect) and capital accumulation. These empirical outcomes are consistent with those of Jongwanich and Kohpaiboon (2019), who argued that remittances generate negative and significant impacts on economic growth when they reach or exceed a threshold in Asian and Pacific developing countries. Larger remittance inflows prevent capital accumulation because marginal emigrants have stronger altruistic motivations to support their families and relatives in their country of origin; therefore, their remittances are used for consumption rather than savings, according to Bourdet and Falck’s (2006) theoretical model.

Policy Implication

The policy implication from the above empirical results is that overdependence on emigrants’ remittances has a detrimental effect on economic performance from sectoral and intertemporal perspectives. Economic growth is attainable even without a high dependence on remittance inflows. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that during the 2000s (the era under President Musharraf) in Pakistan, there were high economic and manufacturing and investment growths despite a lower remittance–GDP ratio (under the 5% threshold).

Inward foreign direct investment (FDI) in the industrial sector is a possible alternative external resource for boosting economic growth. Figure 1 shows that the FDI-to-GDP ratio increased from 2000 to 2007 and reached the same level as the remittance–GDP ratio in 2007. Inward FDI may directly lead to economic industrialisation without inducing Dutch Disease. Several empirical studies support the significant positive impact of FDI inflows on Pakistani economic growth (e.g., Ahmad et al., 2012; Liu & Sarfraz, 2015; Raza & Hussain, 2016; Sohail & Li, 2023; Tahir Suleman & Talha Amin, 2015). FDI inflows in Pakistan during the early 2000s were closely related to the policy regime under former President Musharraf from 2001 to 2008. Burki (2007) argued that continuity in policymaking brought foreign capital into the country through increased investor confidence and a series of successful economic policies such as privatisation, induced new foreign capital, and the premise of new management practices in some vital industrial sectors. Gulzar and Salik (2016) also demonstrated that the government under President Musharraf enacted several policies that provided several incentives: the issuance of a negative list of industrial activities for private investment, removal of restrictions on maximum equity holdings by foreigners, cancellation of the State Bank permission requirement for dividends and disinvestment proceeds remittances, and permission for foreign firms to increase equity capital from the domestic market on a reportable basis.

In summary, the estimation outcomes in this study suggest that the Pakistani economy should reduce its excessive dependence on remittance inflows, which prevents industrialisation and capital accumulation.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the macroeconomic impact of emigrant remittances in Pakistan using a VAR estimation framework. This study contributes to the literature by determining the threshold of the remittance–GDP ratio that has real effects on the economy in terms of Dutch Disease and capital accumulation. Finding this threshold is significant because Pakistan is one of the largest recipients of remittances in the world, and its remittance inflows have experienced substantial fluctuations.

The empirical results from the VAR model estimations show that regarding the Dutch Disease effect, an increase in the remittance–GDP ratio above 6% leads to a decrease in the manufacturing–services ratio; for the capital accumulation effect, an increase in the remittance–GDP ratio above 5% leads to a decrease in the investment–consumption ratio. These outcomes suggest that emigrants’ remittance inflows to Pakistan, after exceeding certain levels relative to the GDP, aggravate industrialisation (the Dutch Disease effect) and capital accumulation.

The policy implication from the empirical results is that overdependence on emigrants’ remittances has detrimental economic effects from sectoral and intertemporal perspectives. Thus, the Pakistani economy should reduce its excessive dependence on remittance inflows and invite inward FDIs in the industrial sector as a possible alternative external resource to contribute to its economic growth.

The limitation of this study is the lack of microeconomic analyses of emigrants’ behaviours regarding the use of their remittances—for instance, spending on housing or education—which may produce different economic outcomes. Microeconomic analyses could enable policymakers to devise concrete policy prescriptions to mitigate the Dutch Disease effect caused by remittance inflows and promote the capital accumulation effect. Therefore, microeconomic evaluations, including case studies on the behaviours of emigrants, could be the main focus of future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.T. and B.B.; methodology, H.T. and B.B.; software, H.T. and B.B.; validation, H.T.; formal analysis: H.T. and B.B.; investigation, B.B.; resources, B.B.; data curation, B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.; writing—review and editing, H.T. and B.B.; supervision, H.T.; project administration, H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See the website: http://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2025). |

| 2 | See the website: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/ (accessed on 20 May 2025). |

References

- Acharya, C. P., & Leon-Gonzalez, R. (2014). How do migration and remittances affect human capital investment? The effects of relaxing information and liquidity constraints. The Journal of Development Studies, 50(3), 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P. A., Calderón, C., Fajnzylber, P., & Lopez, H. (2008). What is the impact of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Development, 36(1), 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P. A., Lartey, E. K. K., & Mandelman, F. S. (2009). Remittances and the Dutch disease. Journal of International Economics, 79(1), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. H., Jr., & Page, J. (2005). Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Development, 33(10), 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Martinez Peria, M. S. (2006). Do workers’ remittances promote financial development? World bank policy research working paper No. 3957. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Hayat, M. F., Luqman, M., & Ullah, S. (2012). The causal links between foreign direct investment and economic growth in Pakistan. European Journal of Business and Economics, 6, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Benhamou, Z., & Cassin, L. (2021). The impact of remittances on savings, capital and economic growth in small emerging countries. Economic Modelling, 94, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M., & Raza, S. A. (2016). Do workers’ remittances boost human capital development? The Pakistan Development Review, 55(2), 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S. (2018). The impacts of workers’ remittances on human capital and labor supply in developing countries. Economic Modelling, 75, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baafi, J. A., & Asiedu, M. K. (2025). The synergistic effects of remittances, savings, education and digital financial technology on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics, 4(1), 132–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bare, U. A. A., Bani, Y., Ismail, N. W., & Rosland, A. (2022). Does financial development mediate the impact of remittances on sustainable human capital investment? New insights from SSA countries. Cogent Economics and Finance, 10(1), 2078460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, H. C., Donou-Adonsou, F., & Upadhyaya, K. (2019). Workers’ remittances and the Dutch disease: Evidence from South Asian countries. International Economic Journal, 33(4), 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berloffa, G., & Giunti, S. (2019). Remittances and healthcare expenditure: Human capital investment or responses to shocks? Evidence from Peru. Review of Development Economics, 23(4), 1540–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A. (1986). On the theory of testing for unit roots in observed time series. The Review of Economic Studies, 53(3), 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, K. (2014). Social capital, remittances and growth. The European Journal of Development Research, 26(5), 574–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouoiyour, J., & Miftah, A. (2016). The impact of remittances on children’s human capital accumulation: Evidence from Morocco. Journal of International Development, 28(2), 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdet, Y., & Falck, H. (2006). Emigrants’ remittances and Dutch disease in Cape Verde. International Economic Journal, 20(3), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, S. J. (2007). Changing perceptions altered reality: Pakistan’s economy under Musharraf, 1999–2006. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M. B. (2011). Remittances flow and financial development in Bangladesh. Economic Modelling, 28(6), 2600–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. B., & Rabbi, F. (2014). Workers’ remittances and Dutch disease in Bangladesh. The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 23(4), 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. (1940). The conditions of economic progress. MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Corden, W. M., & Neary, J. P. (1982). Booming sector and de-industrialisation in a small open economy. The Economic Journal, 92(368), 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daway-Ducanes, S. L. S. (2019). Remittances, Dutch disease, and manufacturing growth in developing economies. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 66(3), 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destrée, N., Gente, K., & Nourry, C. (2021). Migration, remittances and accumulation of human capital with endogenous debt constraints. Mathematical Social Sciences, 112, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayad, G. (2011). ‘Remittances: Dutch disease or export-led growth?’ OxCarre (Oxford centre for the analysis of resource rich economies) (Research Papers). University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Fisera, B., & Workie Tiruneh, M. (2023). Beyond the Balassa-Samuelson effect: Do remittances trigger the Dutch disease? Eastern European Economics, 61(1), 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlich, D., Mahmoud, T. O., & Trebesch, C. (2007). Explaining labour market inactivity in migrant-sending families: Housework, hammock, or higher education? (Kiel Working Paper No. 1391). Kiel Institute for the World Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar, S., & Salik, M. A. (2016). Economic policies of Pakistan during military rules an analytical study in Islamic perspective. Al-Idah, 33(2), 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, A. L., & Simpson, N. B. (2019). Migration, remittances and human capital investment in Kenya. Economic Notes, 48(3), e12142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huay, C. S., & Bani, Y. (2018). Remittances, poverty and human capital: Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(8), 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. (2019). Remittances and the Dutch disease: Evidence from Georgia. Post-Communist Economies, 31(4), 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongwanich, J., & Kohpaiboon, A. (2019). Workers’ remittances, capital inflows, and economic growth in developing Asia and the Pacific. Asian Economic Journal, 33(1), 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K., Khan, M., & Hussain, A. (2021). Remittances and healthcare expenditures: Evidence from Pakistan. Pakistan Development Review, 60(2), 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koska, O. A., Saygin, P. Ö., Çağatay, S., & Artal-Tur, A. (2013). International migration, remittances, and the human capital formation of Egyptian children. International Review of Economics and Finance, 28, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, E. K. K., Mandelman, F. S., & Acosta, P. A. (2012). Remittances, exchange rate regimes and the Dutch disease: A panel data analysis. Review of International Economics, 20(2), 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Sarfraz, M. (2015). Influence of foreign direct investment on gross domestic product; an empirical study of Pakistan. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 7(2), 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Makhlouf, F., & Mughal, M. (2013). Remittances, Dutch disease, and competitiveness: A Bayesian analysis. Journal of Economic Development, 38(2), 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S., & Perron, P. (2001). Lag length selection and the construction of unit root tests with good size and power. Econometrica, 69(6), 1519–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. (2023). Does remittance and human capital formation affect financial development? A comparative analysis between India and China. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 30(2), 387–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periola, O. (2025). Sectoral productivity and real exchange rate effects of remittances: Evidence from Nigeria. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuc, H. N., Hong, C. T. H., & Mai, V. T. P. (2020). Remittances, real exchange rate and the Dutch disease in Asian developing countries. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 77, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S. S., & Hussain, A. (2016). The nexus of foreign direct investment, economic growth and environment in Pakistan. Pakistan Development Review, 55(2), 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R., & Dixon, R. (2016). Workers’ remittances and the Dutch disease in South Asian countries. Applied Economics Letters, 23(6), 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D. (2007). How to handle the macroeconomics of oil wealth. In M. Humphreys, J. D. Sachs, & J. E. Stiglitz (Eds.), Escaping the resource curse. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, V. B. (2014). International remittances and human capital formation. World Development, 59, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, N. S., Javed, S. A., & Ashraf, D. (2018). Remittances, economic growth and poverty: A case of African OIC member countries. The Pakistan Development Review, 57(2), 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R., & Kemal, A. R. (2006). Remittances, trade liberalisation, and poverty in Pakistan: The role of excluded variables in poverty change analysis. Pakistan Development Review, 45(3), 383–415. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, H. M., & Li, Z. (2023). Nexus among foreign direct investment, domestic investment, financial development and economic growth: A NARDL approach in Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 25(2), 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H., & Shammi, R. T. (2018). Emigrant’s remittances, Dutch disease and capital accumulation in Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance, 7(1), 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir Suleman, M., & Talha Amin, M. (2015). The impact of sectoral foreign direct investment on industrial economic growth of Pakistan. Journal of Management Sciences, 2(1), 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, C. M., & Zenteno, R. (2001). Remittances and microenterprises in Mexico graduate school of international relations and pacific studies working paper No. 43. University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. (2005). International migration, human capital, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from Philippine migrants’ exchange rate shocks World Bank policy research working paper No. 3578. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiheyis, Z., & Woldemariam, K. (2016). The effect of remittances on domestic capital formation in select African countries: A comparative empirical analysis. Journal of International Development, 28(2), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).