Abstract

This paper explores the role of export-oriented firms in shaping regional economic development, with a focus on their operational footprint, strategic orientation, and interaction with institutional and infrastructural environments. Set within the broader context of regional competitiveness and sustainable growth, the study examines how firms in geographically peripheral and structurally challenged areas position themselves within global markets. Emphasis is placed on understanding the internal and external factors that influence export performance, innovation capacity, and the integration of sustainability principles into business practices. The research adopts a survey-based methodology, collecting data from firms located in a cross-border region to assess their perceptions of trade barriers, infrastructure needs, strategic values, and environmental awareness. The analysis draws on established frameworks in regional development, international business, and sustainability transitions, offering a multidimensional perspective on firm behavior. By linking firm-level insights with regional development policy, the study contributes to ongoing discussions around how enterprises in remote regions can overcome structural constraints and engage more fully with global value chains. It also supports the growing call for place-based, context-sensitive strategies that align economic competitiveness with innovation, digital transformation, and environmental responsibility. This integrated approach offers valuable implications for both policymakers and practitioners concerned with fostering inclusive and resilient regional economies.

1. Introduction

Export companies have long been recognized as key drivers of economic development, particularly in regional economies seeking to connect more intensely with the international market. Their capacity to increase production, create jobs, and attract investments has made them a critical element of economic policy and strategic planning (Brambilla et al., 2012; OECD, 2017). Export firms are usually better performers than their non-exporting counterparts in terms of productivity, innovation, and competitiveness, thus not only improving the country’s economic output but also stimulating the local business climate (Zahra & George, 2002). However, the regional impact of these firms is heterogeneous and is shaped by a myriad of factors, ranging from infrastructural conditions and the status of the labor market to institutional dynamics and the peculiarities of regional development.

The assessment of export enterprises, defined by their overall economic, social, and spatial contributions to the regions where they are situated, calls for research that transcends standard macroeconomic indicators. Although measures such as national trade balances, foreign direct investment, and growth in gross domestic product yield useful insight, they tend to hide the particular localized influences that exports have upon employment patterns, income inequality, supply chain relationships, and regional patterns of innovation (García et al., 2012). Export firms interact with regional economies in subtle ways that affect various areas, such as the upgrading of infrastructures, patterns of urbanization, skill building, and labor mobility. As a result, their evaluation demands a holistic and sensitivity-based method.

There has been increased interest over recent years both within the academic and policy arenas concerning the role of export firms in promoting regional resilience and adaptability, especially under economic shocks, digitalization, and climate change (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018; European Commission, 2024). Export firms have the potential to promote regional competitiveness by securing international links and generating foreign exchange inflows, but they also face significant challenges, such as regulatory issues, inadequate infrastructures, and shortages of labor. Such challenges tend to be amplified in regions outside the main cities, where there are deepened regional disparities and regional institutions of governance have limited capacity to effectively encourage export-led development (D. J. Dimitriou et al., 2022).

Despite the growing recognition of the role of export-oriented businesses in regional development, there is still a lack of empirical evidence, particularly in structurally disadvantaged regions where SMEs have to deal with fragmented institutional networks and poor infrastructure. The added complexity of the cross-border dimension presents both European Union and non-European Union regulatory regimes as well as variegated market conditions that these companies have to face. Recent analyses emphasized that digital connectivity, regional innovation capacities, and organizational flexibility have become increasingly critical determinants of SME competitiveness in these environments (European Commission, 2024; D. Dimitriou et al., 2024; Aghazadeh et al., 2023). These new dynamics require a rethinking of the internal and external drivers of export performance from a place-based perspective. This study addresses this gap by conducting a comprehensive assessment of the business footprint of export companies within regional economies, using a survey-based methodological framework. The research captures firm-level insights on a range of issues, including business demographics, export performance, infrastructural dependencies, institutional collaboration, and future growth prospects. It examines both quantitative indicators (such as export-to-turnover ratios, energy costs, and employment figures) and qualitative perceptions (such as satisfaction with government support, barriers to market entry, and the role of innovation).

By focusing on firm-level data, the study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how export-oriented businesses interact with regional contexts, influence economic trajectories, and respond to policy environments. In doing so, it offers practical recommendations for regional development strategies, export promotion policies, and frameworks for innovation and sustainability. The findings also aim to inform future academic inquiry into the interplay between globalization and territorial development, emphasizing the importance of context-specific analysis in export economics.

2. Background

2.1. Export Firms and Regional Development: Theoretical Overview

Export activities and regional development have become a pertinent area of research within international trade theory and economic geography. At its core, the presence of export firms within a regional economy is viewed as a driver of economic growth, productivity improvement, and structural change. This early theory can be traced to neoclassical and classical trade theory, such as Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage and the Heckscher-Ohlin theory. Adherents to such theories believe that trade encourages regions to specialize in areas where regions have comparative efficiency, thus ensuring maximum resource allocation and overall welfare improvement (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Sartzetaki et al., 2025a). However, such theories tend to conceptualize regions in a general sense, without accounting for spatial and institutional factors affecting real regional experiences. The new economic geography (NEG) by Krugman (1991) seeks to redress this by emphasizing the importance of the location of economic activities and the main roles of increasing returns to scale, transport cost, and agglomeration economies. NEG proposes that export firms concentrate in regions that are locationally favored, possessing skilled workers and knowledge spillovers—factors that cumulatively ensure that interdependent growth is encouraged and interregional inequality is increased.

Recent literature has focused on global value chains (GVCs) theory to explain how exporting firms get embedded in complex international production systems. According to Love and Roper (2015), the relative position of a region in a GVC not only affects its trade performance but also determines its capacity to attract investments, upgrade technological capabilities, and develop human resources. Regions that are typified mainly as low-cost manufacturing hubs are more prone to value appropriation problems, while those engaged in design, logistics, or brand management are likely to bring more development benefits. Another important theoretical basis stems from endogenous growth theory, which creates a link between export activity, innovation, and learning. Exposure to export activity subjects firms to competition on a global scale and to global consumer tastes, thus inducing innovations, improving quality, and increasing process efficiency (Tödtling & Trippl, 2005; Chaminade & Plechero, 2012). The process of such innovation often goes beyond the boundaries of an individual firm and has a positive impact on regional systems, especially by inducing inter-firm cooperation, labor mobility, and university-industry partnerships.

The Regional Innovation Systems (RISs) framework deepens export enterprise analysis by situating them in a network of institutions, policies, and norms that shape their innovative capability (Castellani & Zanfei, 2007). This framework highlights the importance of closeness to research institutions, governmental assistance programs, and collective culture practices as essential factors supporting the success of exporting firms. Differences in regional export performance, therefore, cannot be solely explained by market accessibility or price factors but are also dependent upon the resilience of institutions and the cohesiveness of the supporting community. In addition to this, in terms of regional development, export firms are not only seen in economic terms but also in terms of driving spatial change. Trade and transport demand by exporting firms have significant impacts upon urban development, land use, and public investment agendas. This vision harmonizes with a growing body of literature promoting sustainable and just regional development, encouraging a more integrated approach to trade-led growth that takes account of issues of equity and ecological responsibility (D. Dimitriou et al., 2024; Teece, 2007).

Recent academic works have emphasized that the internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the periphery of regions and across borders is more and more determined by access to digital technologies, involvement in multi-partner innovation networks, and a commitment to good environmental standards. Research by Aghazadeh et al. (2023) and Calheiros-Lobo et al. (2023) investigated how smaller businesses leverage strategic alliances, embrace digital innovations, and engage in sustainable environmental marketing to enter into and embed themselves in international markets. Cross-case comparisons in the context of the European Union have shown the difference in the policy needs of urban hubs and regions peripheries and hence recommended smart specialization policies that account for local constraints and the potentialities of regional expertise (European Commission, 2024; Sartzetaki et al., 2025a). These observations underscore the importance of using a region-based analytical framework to review SME export performance and the need for context-related analyses, particularly in the midst of current economic instability and change.

Alongside abstract paradigms such as new economic geography, global value chains, and endogenous growth theory, recent work has underscored the importance of business and industrial agglomerations of the type of clusters, industrial districts, and local production systems as key drivers of the internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These more specific forms of spatial organization of the economy foster synergies amidst shared infrastructure, pooling of labor, transfer of knowledge, and specialization, thereby enhancing the aggregate competitiveness of firms that happen to locate in closer geographic proximity. A growing body of empirical evidence confirms that such agglomeration arrangements ought effectively to counterbalance the disadvantage of the periphery regions’ structure. To mention but a few examples, Parejo et al. (2019) show how Portugal’s local production systems served as drivers of regional development and of export growth even in economically underprivileged regions. Rangel-Preciado et al. (2021) consider the case of Extremadura, one of the least developed regions of Spain, and find that rural industrial districts have become the drivers of SMEs’ access to international markets. These findings highlight the potential of local business milieux as intermediary institutions that empower firms’ absorptive capacity, innovative potentiality, and readiness for cross-border operations. The recognition of these ideas is strongly in line with the objectives of this work in light of the peripheric and structurally handicapped character of Eastern Macedonia and the Region of Thrace. Territorial embeddedness, inter-business firm relations, and institutional coordination assume the primary importance when considering how SMEs cope with internationalization in the given situations.

2.2. Key Dimensions of Business Footprint in Cross-Border Trade

The concept of a business footprint has evolved to be a robust framework for measuring the vast influence of companies within their areas of operations. Traditionally, standard analysis has focused predominantly on economic performance metrics, such as measures of employment, revenue, and the levels of investment; however, new footprint frameworks now include environmental and social measures to provide a better holistic view of corporate presence (OECD, 2017; Barca et al., 2012; D. Dimitriou & Karagkouni, 2022). This evolution is especially pertinent to export-oriented companies, whose operations not only interact with international markets but also yield localized effects in various sectors. Economically speaking, an organization’s footprint is usually measured based on indicators like gross value added (GVA), job creation, tax contributions, and the enablement of supply channels. Export-oriented companies quite often excel over domestically oriented companies in such assessments by achieving better levels of productivity, increasing diversification, and favoring international integration by means of subcontracting and logistic partnerships (Barney, 1991; Dicken, 2015). Input-output analysis, regional multipliers, or the use of computable general equilibrium (CGE) models is usually the approach adopted by economic footprint assessments to quantify the indirect and induced effects of corporate operations within a specific location (Camagni, 2002).

In parallel, the ecological intensity associated with corporate operations has become more influential in policy debates and academic literature, especially concerning climate change and calls for sustainable change. The environmental dimension includes the use of natural resources, the production of emissions, the release of waste, and energy consumption. Export units, especially those in manufacturing sectors and energy-consuming industries, are key drivers of environmental externalities through their production activities, transport arrangements, and packaging protocols (D. Dimitriou et al., 2024). The impacts are estimated by methods like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Environmental Input-Output (EIO) analysis at international and regional levels. Energy and fuel expenses are regularly employed as a measure to evaluate environmental intensity and energy dependence. The social framework widens the inquiry to encompass issues related to workers’ conditions, community engagement, and corporate responsibility. This includes issues like gender parity, labor practices, workers’ wellbeing, and ethical codes that underpin business practices (Batty et al., 2012; D. Dimitriou & Sartzetaki, 2022). Export companies have the capacity to provide positive social results by promoting quality employment and skill development; however, without correct regulations, the same companies can deepen polarization in the labor market, result in displacement, or contribute to dependence upon precarious contractual arrangements. Methods to measure the social footprint tend to use methods like Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA), stakeholder mapping, and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) report criteria to systemically evaluate impacts (Sartzetaki et al., 2025b).

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approach, first conceptualized by Elkington (1997), is a vital integrating paradigm that seeks to underscore the need to make economic sustainability, environmental responsibility, and social equity reconcilable. In this paradigm, corporate performance measurement goes beyond profit measurements to include concerns for the well-being of “people” and the integrity of the “planet.” This holistic approach is increasingly finding acceptance in firm reporting and sustainability assessments, especially by companies operating in international markets where compliance with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices is a basic condition of international competitiveness. In regional economies, regional footprints are also expected to be measured by localized considerations of the availability of infrastructure, institutional quality, and the presence of regional innovation systems. Business actors are not mutually exclusive entities; they are part of wider economic and social systems. Therefore, business footprints are increasingly personalized to factor in geographical differences, thus helping policymakers detect region-based strengths and limitations with respect to exports (D. Dimitriou, 2020).

2.3. Innovation as an Export Performance Key Driver in Europe

Innovation and infrastructure are repeatedly considered key factors that build export competitiveness and promote regional development. Exporting firms that innovate—either by improving processes, designing new products, or reconfiguring their organization—are more likely to penetrate new markets, adopt international standards, and respond to changing consumer tastes (Love & Roper, 2015). In addition, the all-encompassing presence of top-quality infrastructures, covering transportation, energy, digital connectivity, and supply chains, is essential to streamline operations, guarantee deliveries within a reasonable time frame, and enhance international trade efficiency. Whereas the importance of such drivers has been well documented, relationships between innovation, infrastructure, and export performance are inadequately studied, especially at the firm and regional levels. Innovation is measured chiefly with proxies like research and development (R&D) spending, patent activities, or participation in knowledge networks. However, such indicators tend to miss innovations created by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) since these firms are more likely to adopt tacit or incremental innovations instead of practicing a systematic R&D approach (OECD, 2017). This becomes more relevant when export-oriented firms are located in peripheral regions, where there is a lack of institutional backing for innovation and accessibility to universities or research centers. The Regional Innovation System (RIS) theory is relevant here, where cooperation between firms, together with universities and public agencies, is essential to develop innovative capability (Tödtling & Trippl, 2005). But there is a lack of empirical work that considers the composition and intensity of networks from the viewpoint of exporting firms.

Infrastructure is usually analyzed via macro-indicator levels or holistic national development plans. As much as such indicators are informative, they do not capture the territorial complexities and sectoral demands of export firms. For example, the presence of roads and railways, the capacity of ports, the availability of bandwidth, and the dependability of power supply can have wide regional variations, affecting the operational effectiveness and competitiveness of exporting companies (World Bank, 2020; Sartzetaki et al., 2023). Additionally, environmental infrastructure, in terms of the availability of effective disposal of wastewater and renewable energy, has become a centerpiece in export markets where compliance with regulations and sustainability certifications are essential in gaining market footholds. Despite increased policy emphasis on driving innovation and investment in infrastructure as drivers of exports, a wide literature gap exists in addressing firm-level perspectives, especially with regard to the way export firms construe, interface with, and are hindered by local innovation milieus and infrastructures. Dominating research practices are top-down in nature, basing themselves on aggregated data or national indicators that conceal intra-regional variations and special challenges faced by firms located in specific locations (Foray et al., 2012).

The current research bridges a gap that exists by utilizing a survey-based research design to collect data relating to the experiences and strategic orientations of export firms within a regional framework. It investigates the way such firms evaluate the sufficiency of regional infrastructures, such as transport systems, energy supplies, and information technology inputs, and the extent to which they are involved in innovative activities like research and development, digitalization, and partnerships with academia. In addition, the research considers the preparedness of such firms to extend their export activities, their rating of institutional assistance, and their capacity to adopt sustainable practices, thus providing a deep insight into the drivers of export performance. By concentrating at the firm level and emphasizing regional differences, the research contributes to export dynamic knowledge. This research makes it possible to formulate more customized policy interventions that are consistent with the exact demands of export companies and characteristics of successful local innovation systems and infrastructural inputs. As a result, this research not only resolves a pertinent gap within literature but also provides useful conclusions for regional policymakers, development agencies, and academic institutions to strengthen international competitiveness within the economy.

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Questionnaire Survey Research Design

This study employs a quantitative, survey-based research design to assess the business footprint of export-oriented companies operating in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, a remote and cross-border region located in northern Greece. The region, situated at the geopolitical intersection of the Balkans, the Black Sea, and the eastern Mediterranean, presents a distinctive setting for export-driven economic activity. Despite its strategic location, Eastern Macedonia and Thrace face structural challenges such as underdeveloped infrastructure, limited access to capital, and a fragmented industrial base, factors that directly influence the export performance and developmental footprint of local firms.

The research design employed was a cross-sectional descriptive one that seeks to analyze the economic, infrastructural, and innovation-related characteristics of the firms under investigation. The purpose of this study is not to delve into cause-and-effect relationships but rather to capture observable patterns, detect constraints and opportunities, and infer the perspectives and activities of export firms within their regional contexts. The use of a survey-based research methodology allows data to be gathered that is both comparable and standardizable over different firms and industries, entailing both objective quantitative measures (export-to-turnover ratio, employment) and subjective qualitative evaluation scales (levels of satisfaction with infrastructure or institutional assistance). By focusing at the firm level within a defined regional framework, this research seeks to bridge the gap between national trade data and the experiences of everyday regional development. Data collected will be a basis against which to evaluate the export firms’ effects in economic, social, and environmental areas, with profound implications for regional policy development and strategic programming.

The key data collection tool was a rigorously designed questionnaire, tailor-made to capture a wide variety of data related to the operational, economic, and strategic activities of export firms in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. The tool was designed to align with the conceptual framework discussed in the literature, combining the dimensions of the triple-bottom-line concept (economic effectiveness, environmental effects, and accountability to society) with regional infrastructure, innovation, and the institutional framework. The questionnaire consisted of four thematic areas, all of which are elaborated in full in the later Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire Structure and Response Formats.

The questions included in the survey were carefully selected to enable a comprehensive and subtle examination of the economic role of export-oriented firms within the regional economy. Based on time-tested theoretical frameworks related to regional development, international trade, and business sustainability, the survey was designed to include both quantitative measures and qualitative evaluations within economic, infrastructural, and strategic aspects. Consideration of demographic characteristics of firms, such as classification of industries, firm size, and percentage of export revenue, allows segmentation and comparative analysis to suit different business profiles. Questions related to export performance, market issues, and cost structures were incorporated to throw light upon operating constraints and competition dynamics faced by companies operating in export markets. In parallel, questions related to the quality of infrastructures, institutional cooperation, and relocation policies provide insight into the regional environment and spatial processes affecting corporate behaviors. Emphasis upon innovation, digitalization, and sustainability highlights salient priority issues inherent to economic development policy and aligns concepts such as the triple bottom line and circular economy. By integrating both perceptual and empirical information, the survey aims to clarify the extent to which export firms interact with their regional contexts and the way in which such behaviors influence their potential for development, resilience, and sustainable contributions.

The main research interest targets export-oriented enterprises located in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, a peripheral and cross-border region of northern Greece. In the absence of a comprehensive and centralized register of export companies in the area, a purposive non-probability sampling method was adopted. Identification of the companies was supported using institutional sources with specific reference to the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Both of these provided access to firm-level information with rich details on the industries as well as specific destinations of export. The databases used as a primary and reliable source of identifying active companies in the export business have some drawbacks related to the completeness and contemporaneity of the records and specifically with regard to the small- and micro-sized companies. Cross-checking against the regional export records as well as with local umbrella business organizations rectified these problems.

The main research tool used in this research was an internet-based survey questionnaire hosted on the SurveyMonkey platform, carefully crafted to obtain both qualitative and quantitative information on firm attributes, export performance, infrastructure dependency, and innovation activity. Though survey-based methods have the advantage of providing direct feedback from firms immediately, they are beset with issues of self-selection bias, differences in interpretation of scale-based questions, and the possibility of reporting errors in variables. To address content validity of the survey questionnaire, it was designed following existing frameworks used in the field of regional development and sustainability analysis and was reviewed by subject matter experts before it was launched. Despite such quality assurance steps, the findings must be viewed with caution, given the non-random nature of the sample and the inherent weaknesses related to self-reported data.

This method allowed a focus on firms actually involved in exporting activities and ensured a better relevance of data to the study purpose. A total of 145 firms returned complete questionnaires, all via an online survey tool made available by the SurveyMonkey platform. This online platform improved accessibility within the area and allowed respondents to answer at their convenience, regardless of their location. Even if the sample is not designed to be representative of all Greek export companies, it gathers a sufficient and heterogeneous dataset to be suitable for descriptive analysis that is specific to the area. Participating firms are diverse with respect to size, level of export intensity, and level of connection to innovation and institutional networks. This sampling technique can be limited in generalizability but allows a focused and contextualized study of the export dynamics within a region with distinctive development characteristics. The dataset constitutes a useful empirical reference to evaluate the regional dynamics of export firms and to propose targeted policy recommendations. Invitations were extended to each firm with a statement describing the research purpose, a promise of guaranteeing confidentiality, and a provision of voluntary participation, compliant with data protection regulations (in line with GDPR requirements). In each stage of the process, respondents’ anonymity was guaranteed, and no personally identifiable data (such as firm name or contact information) were requested. All ethical obligations were met appropriately, ensuring informed consent and careful handling of all data obtained.

The utilization of a purposive non-probability sampling methodology allowed the study to target establishments that are engaged in export activity; nonetheless, the methodology has inherent limits in relation to the representativeness of the sample. Randomization precludes statistical generalization of the findings to the entire population of SMEs that undertake export activity in Greece. Thus, the outcomes should be taken as context-dependent insights that reflect the establishments operating in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Moreover, the regional focus offers a certain depth and specificity but, of course, limits the transferability of the findings to geographic or institutional contexts different from the one selected. Such limits are taken as an inherent compromise between empirical significance and wider generalizability, particularly in regional analyses that stem from place-based development paradigms.

3.2. Data Processing and Analysis

Upon completion of data collection, all the responses were fetched from SurveyMonkey and exported to a spreadsheet format and subsequently transferred to SPSS Statistics Version 29 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) to be analyzed and processed extensively. Before commencing with any analytics process, the dataset was thoroughly checked to identify any missing values, especially missing data instances, and outlier observations or inconsistent ones. Incomplete replies, in particular with missing entire sections, were not included in the analysis to maintain data integrity and internal validity. Descriptive and exploratory statistical procedures were utilized in the analysis, known to be efficient in revealing patterns and distributions between variables. For categorical and ordinal variables, descriptive measures such as means, medians, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages were computed. Central tendency and dispersion of the Likert items were measured to test the perceived levels of regional variables and business practices.

In cases where cross-variable relationships were explored (e.g., export intensity vs. infrastructure satisfaction), bivariate correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s rho (ρ) for ordinal data, due to the non-parametric nature of the variables. The formula for Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is given by:

where:

di = difference between the ranks of two variables for observation

n = number of observations

To assess variation across groups (e.g., firm size categories or sectors), non-parametric tests such as the Kruskal–Wallis H test were employed:

where:

n = total number of observations

ni = number of observations in group i

Ri = sum of ranks in group i

k = number of groups

Given the wide range of the survey with respect to economic, infrastructural, and innovation factors, the findings were systematically grouped according to the questionnaire framework, thus allowing logical and narrative presentation of findings in Section 4.

The validity and authenticity of both the findings and the research tools formed a basic aspect of the methodology and its execution. Content validity was ensured by mapping the questionnaire items to the conceptual frameworks elicited in literature pertaining to regional development, export performance, and the measurement of business footprints. Survey and organization were screened by subject-matter experts to ensure relevance and understandability. Proof of construct validity was established by grouping items into thematically related components (i.e., infrastructure, innovation, sustainability) and ensuring that each of them was designed to measure distinct dimensions of the export firms’ footprints. Even without the use of confirmatory factor analysis within the research, owing to limitations related to sample size and being descriptive in nature, each thematic component was assessed in terms of internal consistency. To assess internal reliability of the multi-item sections (especially those using Likert-type scales), Cronbach’s alpha () was calculated, as below:

where:

N = number of items

= average covariance between item-pairs

= average variance

A threshold of α ≥ 0.7 was used to indicate acceptable internal consistency, consistent with methodological standards in social sciences (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Where alpha values were slightly below this threshold, item-level diagnostics were reviewed to identify potential inconsistencies. In terms of external validity, the study’s findings are specific to the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace and cannot be generalized to all export firms in Greece. However, the methodology ensures contextual validity by capturing firm-level insights that reflect the structural and institutional characteristics of the selected region.

4. Questionnaire Key Results

4.1. Firm Characteristics and Export Profile

The descriptive analysis of firm-level data presented in Table 2 provides an integrated overview of the export-oriented firms operating within the area of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. A total of 145 export-oriented firms participated in the survey, representing a diverse cross-section of the regional business landscape in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. A considerable percentage of the firms (42.66%) reported their establishment before the year 2000, reflecting a strongly established presence within the economy of the area; at the same time, 39.86% were established after 2010, reflecting a considerable increase in entrepreneurial activities over the past decade. Additionally, considerable growth in export operations has been noted in recent years, with 54.75% of companies starting international operations after 2010. In reference to organizational positions, more than half of the respondents (51.30%) are either members of the Board of Directors or shareholders, reflecting a substantial level of decision-making power within the respondents. The sample illustrates substantial variation with regard to company size, sector affiliation, and export approach. Micro-enterprises, which have fewer than 10 employees, comprise the largest majority of the sample at 66.91%, while small firms, with between 10 and 30 employees, account for another 17.27%. In contrast, medium and large firms, with more than 100 employees, account for a lesser percentage, reflective of the general business environment of the region.

Table 2.

Questionnaire data descriptive analysis.

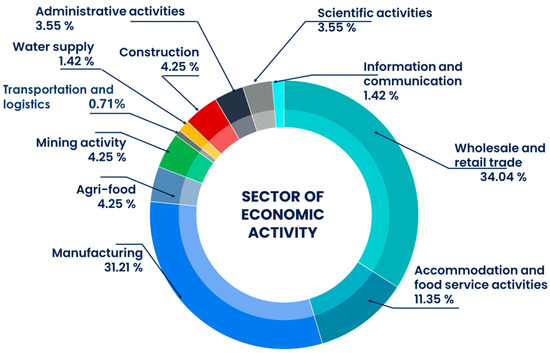

Based on the financial capacity analysis, 51.82% of respondents reported a turnover of less than €500,000 per year, and a mere 10.22% recorded a turnover of more than €10 million per year. This ratio indicates the predominance of small-scale businesses in the regional export structure. From the perspective of export orientation, 27.74% of companies reported more than half of the revenue as stemming from international markets, and 43.80% reported export revenue as less than 10% of the overall turnover. These findings indicate significant variation in the levels of international market involvement among a range of diverse firms, from high-export-oriented businesses to those with little international contact. In terms of classificatory sectors, wholesale and retail trade (34.04%) and manufacturing (31.21%) sectors are the most advanced. Other sectors include accommodation and food services (11.35%) and agri-food industries, construction, and mining, as well as a limited representation of professional and scientific as well as administrative services. This classification indicates a diversified base of exports that is still anchored in the modern economic structures of the area. These variables are presented systematically in Table 2 as a comprehensive classification of the firm’s demographics, sectors represented, turnover categories, and intensity of export. This profile is vital in contextualizing the following findings and adds interpretative rigor that is inherent in the empirical results of the analysis.

The sectoral distribution of export-oriented firms in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, presented in Figure 1, reveals a pronounced concentration in both trading activities (34.04% in retail and wholesale trading) and production (31.21% in manufacturing). This result highlights the area’s dual purpose both as a prime production area and as a leading commercial trading center. Together, the two industries make up over 65% of the firms included here and thereby underscore their overriding influence over the area’s export-led economy. The accommodation and food and beverage industries, respectively, command a sizeable amount (11.35%), reflecting the significance of tourism and hospitality-related exports, especially within cross-border settings. Although small in size, the agri-food (4.25%), mining (4.25%), and construction (4.25%) industries play a crucial role, each supporting resource-based and infrastructure-dependent exports. The administrative (3.55%), science (3.55%), and information and communication sectors (1.42%), respectively, point to an emerging diversification in regional economic life. Contrarily, the transportation and logistics sector (0.71%), although critical to export operations, seems to be underrepresented in the leading sectors of business, possibly due to sectoral overlap and the dominance of subcontracting. The heterogeneity in sectors indicates the complexities involved in the regional export economy and proposes potential avenues of policy intervention and innovative action.

Figure 1.

Sectoral Distribution of Export-Oriented Firms. The majority of firms operate in wholesale and retail trade (34.04%) and manufacturing (31.21%), reflecting the dual commercial and productive character of the regional economy. Notable secondary sectors include accommodation and food services, agri-food, and construction, indicating a diversified but regionally embedded export base.

The analysis of current and target export destinations reveals both the geographical spread and strategic orientation of export firms in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. The most frequently cited current export destinations include Germany, Bulgaria, Romania, Italy, and Cyprus, illustrating a strong reliance on European markets and neighboring countries, particularly within the Balkans. These findings reflect not only geographical proximity and established trade links but also cultural and logistical familiarity. Additionally, countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia also appear as active destinations, indicating some penetration into more distant and economically significant global markets.

In terms of desired future export destinations, firms expressed strong interest in expanding toward more diversified and high-growth markets, including India, China, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, and Japan. This reflects a clear ambition to tap into emerging economies and larger consumer bases while maintaining engagement with traditional European partners such as Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands. Notably, countries such as Australia, South Korea, and various states in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region also featured prominently, underscoring a growing appetite for global market diversification. This shift signals that export firms are increasingly outward-looking and willing to explore high-potential markets beyond the EU, despite the inherent complexities of operating in such environments.

4.2. Export Barriers and Regional Growth Initiatives

This section evaluates two key dimensions affecting export firm performance in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace: the barriers faced in international markets and the regional infrastructure and institutional environment that support or hinder business growth.

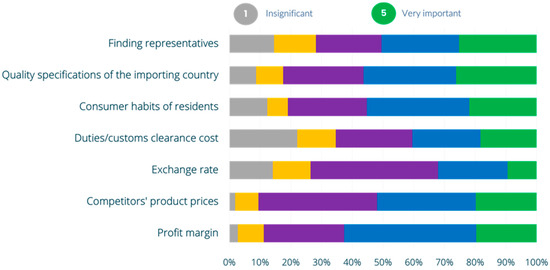

According to Figure 2, the most critical barrier identified was quality specifications of the importing country, with more than 80% of respondents rating it as either 4 or 5. This underscores the persistent burden of regulatory compliance, especially in markets with stringent product standards, and supports previous findings that non-tariff barriers constitute a primary concern for exporters. Following closely were concerns related to profit margins and competitors’ product prices, with approximately 75–80% of firms assigning high importance to these economic pressures. Similarly, customs duties and clearance costs were ranked as a significant burden by over 70% of respondents, highlighting the financial and procedural challenges of cross-border trade. Issues related to consumer preferences and exchange rate volatility were rated slightly lower, though still notable—indicating sensitivity to market behavior and macroeconomic instability. Interestingly, the lowest-rated barrier, though still significant, was the difficulty in finding representatives or distributors abroad.

Figure 2.

Perceived Importance of Key Export Barriers in Primary International Markets. Quality compliance requirements and customs duties are identified as the most significant trade barriers, with over 80% of firms assigning them high importance. These non-tariff constraints appear to negatively affect export intensity, particularly among SMEs in structurally remote regions.

To assess the relationship between these barriers and actual export performance, a Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was conducted. The results indicate a statistically significant negative correlation between perceived compliance barriers and export intensity (measured as export turnover ratio), with ρ = −0.34 (p < 0.05). This implies that firms that perceive higher certification or regulatory burdens tend to exhibit lower engagement in foreign markets. The internal consistency of the barrier items was confirmed by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81, indicating high reliability of the measurement scale.

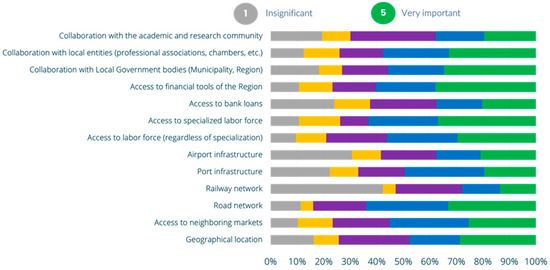

The results depicted in Figure 3 provide a detailed overview of how export-oriented firms in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace perceive the importance of various infrastructure and institutional support factors for business development. Among all categories, access to neighboring markets and geographical location received the highest importance ratings, with more than 80% of firms assigning them a score of 4 or 5. Transport infrastructure, particularly the road network, was also highly rated, with over 75% of respondents considering it important or very important. However, infrastructure elements like the railway network and airport infrastructure received relatively lower scores, possibly reflecting limitations in service quality, coverage, or perceived relevance to the firms’ current logistics models. In terms of human capital, both access to specialized labor and general labor availability were considered highly important (ratings ≥ 4 by approximately 70% of firms), pointing to persistent workforce challenges in regional business environments.

Figure 3.

Perceived Importance of Strategic Initiatives of Export Enhancement. Geographical location and access to neighboring markets are considered major enablers of export activity, followed by the adequacy of transport infrastructure. These responses reflect the region’s dependence on spatial connectivity and logistical accessibility.

Sectoral differences were explored using a Kruskal–Wallis H test, which revealed statistically significant variation in the importance of product development across firm types (H = 6.87, p < 0.01), with manufacturing firms assigning it the highest weight. Moreover, Spearman’s rho indicated a positive correlation between the importance of product development and the proportion of turnover derived from exports (ρ = 0.38, p < 0.05), confirming that innovation-oriented firms tend to exhibit stronger export engagement. The internal reliability of this scale was also high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

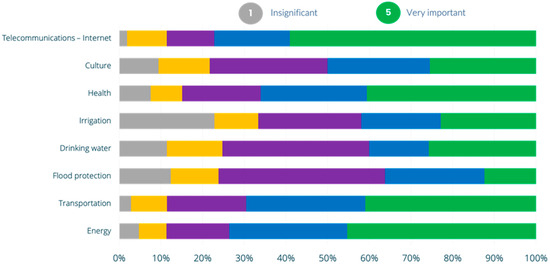

Figure 4 analyzes the perceived importance of public and regional investments in critical infrastructure sectors. The most highly rated infrastructure category was telecommunications—Internet, with nearly 90% of firms assigning a rating of 4 or 5. Energy infrastructure and transportation followed closely, with over 80% of respondents deeming them as “important” or “very important”. These results reaffirm the centrality of reliable and cost-effective energy supply and mobility systems for export-intensive operations. Other infrastructure areas such as potable water, irrigation, and flood protection also received considerable attention (over 70% of respondents rated them 4 or 5), especially among firms in the agri-food and manufacturing sectors. In contrast, health infrastructure and cultural investment were rated slightly lower in direct business relevance, although still significant. These categories received strong support from approximately 60–70% of firms.

Figure 4.

Perceived Importance of Investment in Critical Infrastructures. Digital infrastructure (telecommunications and internet) and energy supply infrastructure received the highest ratings, indicating their strategic value for operational efficiency and export performance.

The distribution of responses across the infrastructure categories showed consistent emphasis on physical and digital foundations over softer infrastructure types. A Kruskal–Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in priority depending on sector, with agricultural firms placing more importance on irrigation and flood protection (H = 7.12, p < 0.01), while service-based firms emphasized telecom and culture. The reliability of the full infrastructure investment scale was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, indicating strong internal consistency. Furthermore, the structure and selection of infrastructure items align with EU cohesion policy objectives and smart specialization strategies, reinforcing the content validity of the measurement instrument.

4.3. Innovation Capacity, Sustainability, and Strategic Orientation

This subsection explores the normative and ethical frameworks that underpin firm strategy, based on firm ratings of business values. Dimensions analyzed include corporate ethics, transparency, gender equality, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and commitment to quality and environmental responsibility.

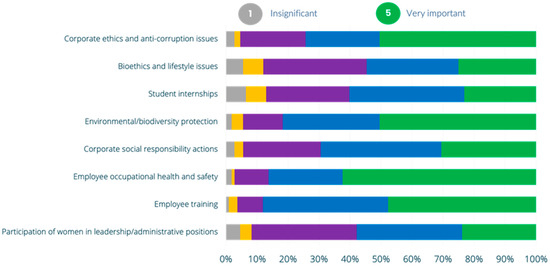

The survey data displayed in Figure 5 offers valuable insight into the ethical and social value framework that guides the operations of export-oriented firms in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Among the most highly rated dimensions was corporate ethics and anti-corruption, with an overwhelming majority of firms (approx. 85–90%) rating this as important or very important. Corporate social responsibility (CSR), environmental and biodiversity protection, and employee training and health and safety also scored prominently, all receiving high importance ratings from over 70% of firms. In addition, participation of women in leadership, student internship opportunities, and bioethics/lifestyle issues received moderate to high levels of support.

Figure 5.

Perceived Importance of Core Business Values and Organizational Culture. Firms placed strong emphasis on corporate ethics, transparency, and corporate social responsibility. Environmental protection and employee well-being were also widely prioritized, suggesting an emerging value-based strategic orientation among regional exporters.

The consistency of responses across this diverse value set supports the internal coherence of the measurement scale. This was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75, indicating reliable internal consistency. Furthermore, the spread of values included in the questionnaire aligns with internationally recognized sustainability and corporate governance frameworks (e.g., SDGs, ESG criteria), reinforcing the content validity of this survey component.

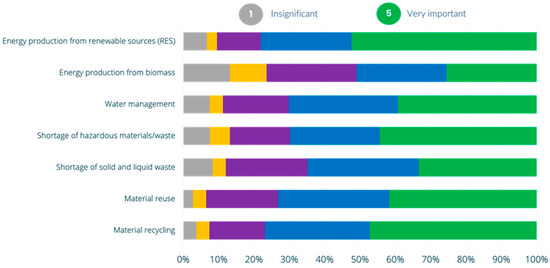

Figure 6 presents the firms’ evaluations of eight key factors relevant to the circular economy. These dimensions capture sustainability practices related to resource efficiency, waste management, and renewable energy, all of which are increasingly recognized as integral to sustainable business development. Among all surveyed items, energy production from renewable sources (RES) and material recycling received the highest importance ratings, with nearly 90% of firms indicating these as either important or very important. Closely following were material reuse and shortage of hazardous materials/waste, with approximately 80–85% of respondents rating them highly. Other categories, including water management, energy from biomass, and the shortage of solid and liquid waste, were also rated as important, though with slightly more variation in perceived significance across firms.

Figure 6.

Perceived Importance of Adoption of Circular Economy and Sustainability Practices. Recycling, material reuse, and the adoption of renewable energy are ranked as highly important by a majority of firms. These practices reflect increasing awareness of environmental concerns and a shift toward sustainability-aligned export strategies.

The overall internal consistency of the circular economy item set was measured via Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.77), confirming high reliability. The broad support for most items and their logical alignment with circular economy frameworks further affirm the content validity of the construct. These findings collectively suggest that firms are not only aware of sustainability imperatives but are increasingly integrating environmental priorities into their strategic planning. However, the differences in intensity across categories also point to the need for sector-sensitive policy incentives and infrastructure support to fully operationalize circular practices in the regional business landscape.

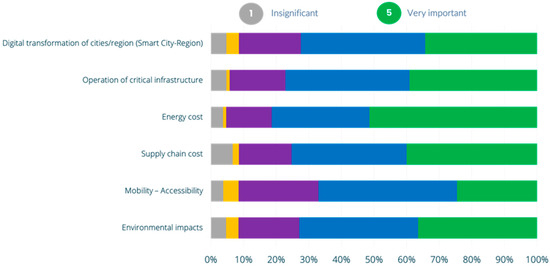

The results depicted in Figure 7 reflect firm-level perceptions of the importance of digital platforms that support monitoring and evaluation in the context of regional transformation, infrastructure, and sustainability. The highest-rated item was energy cost monitoring, with over 85% of firms rating it as “important” or “very important”. Likewise, operation of critical infrastructure and environmental impacts received similarly high levels of support, suggesting that firms are increasingly invested in understanding the systemic conditions that influence their operating environment. Digital transformation of cities and regions (Smart City–Region) and mobility/accessibility indicators were also prioritized by respondents. Meanwhile, supply chain cost tracking emerged as another critical area, with more than 75% of firms viewing it as vital.

Figure 7.

Perceived Importance of Strategic Intelligence and Monitoring Tools. Energy cost monitoring and infrastructure performance tracking are viewed as essential for decision-making. Firms also value tools for monitoring environmental impacts and mobility, indicating a strong interest in digital transformation for competitive positioning.

The overall consistency of these items as a conceptual group was strong, supported by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79, indicating reliable internal cohesion. Additionally, a Spearman’s rank correlation analysis showed that firms placing higher importance on environmental monitoring tools were also more likely to rate renewable energy and recycling practices highly (ρ = 0.41, p < 0.01), demonstrating construct validity through cross-domain alignment.

To further explore structural differences in firm responses, independent-sample t-tests were used to test for differences in firm structure variations in responses based on the views of micro-enterprises (1–10 employees) as compared with small-to-medium-sized enterprises (over 10 employees) on specific Likert-scale statements. A number of statistically significant differences emerged. Small-to-medium-sized enterprises revealed a significantly stronger focus on the importance of logistics cost control (p = 0.0042), the functionality of key infrastructure (p = 0.0124), and the development of mobility and infrastructure monitoring systems (p = 0.0006) when compared with micro-enterprises. These differences infer that small-to-medium-sized enterprises face increased operational complexity and hence greater vulnerability to variation in energy costs, supply chain variability, and the effectiveness of public infrastructure. Moreover, the priority placed on energy cost control was significantly greater among small-to-medium-sized enterprises (p = 0.0008), demonstrating the importance of scale and number with respect to fixed cost vulnerability. Micro-enterprises generally rated most items as being of significance but with less differentiation in responses, possibly reflecting more constrained operational views and limited experience in applying strategic planning tools. Small-to-medium-sized enterprises, however, appeared more responsive to systemic issues and strategic infrastructure control in keeping with greater internationalization orientation and resource capacity. These statistically significant differences infer the argument that firm size is a significant moderator of the way that businesses react to the operating environment and respond to infrastructure priorities in response to policy.

5. Discussion

The findings outlined in this research make a valuable contribution to the understanding of the operational, institutional, and strategic forces that determine the conduct of export-oriented enterprises in the Eastern Macedonia and Thrace Region. This region is defined as geographically peripheral and transnational and with structural development imbalances. Examining the case within the combined frameworks of regional competitiveness (Porter, 1990; Camagni, 2002), export performance theory (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994), and the European Union’s cohesion and smart specialization policies (Foray et al., 2012), the findings reveal systemic limitations and endogenous opportunities that are inherent within this less urbanized economic environment.

The dynamics revealed by this work reflect wider trends apparent in other periphery regions of the European Union. For instance, Rangel-Preciado et al. (2021) found that SMEs in the case of Extremadura, Spain, face similar infrastructure and institutional issues but have used regional networks successfully to facilitate their export activity. Also, Parejo et al. (2019) recorded the role of local production systems in the internationalization of SMEs in the less developed periphery of Portugal. Similarly, in a comparable context, studies within the Baltic setting have emphasized key roles for multi-level governance and European Union structural funds in affecting the export channels of faraway economies (Medve-Bálint & Szabó, 2024). These comparative instances highlight the need for place-based policies and justify the transferability of observations from Eastern Macedonia and Thrace to other situations with similar structural weaknesses.

The initial study of non-tariff barriers, mainly related to product standards, customs measures, and administrative requirements, offers a significant basis for the current debate within academic research concerning the disproportionate effect of regulatory complexity upon small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) located in underdeveloped regions (World Bank, 2020; OECD, 2017). The finding that more than 80% of firms view such barriers to be highly important, and the negative correlation with export performance that has been found, supports the argument that institutional frictions and compliance costs are foremost hindrances to internationalization in disadvantaged regions (Abiad et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2001). Such disincentives are especially discernible in areas like Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, where firms are pushed to navigate the complex regulatory structures of both EU and non-EU markets because of their geospatial location.

Analysis of regional investments and prioritized infrastructures highlights the importance of physical and spatial conditions in connection to export preparedness. High levels of connectivity to proximate markets, transport infrastructures, and ICT infrastructures are consistent with new economic geography theories, where accessibility and network externalities are determinant factors in a region’s export capacity (Krugman, 1991; Rodríguez-Pose, 2018). Additionally, a relatively low level of sectoral diversification with respect to infrastructural demands, especially concerning basic functions like irrigation and protection against floods for agri-food firms, highlights the need to develop place-based policies, a main element of the European Union’s strategy towards the smart specialization policy (Barca et al., 2012). The findings show a re-emphasized relevance of basic infrastructures to firms located within peripheral economies even in a digitalization-focused perspective.

A strategic emphasis on product development innovation, international marketing efforts, and trade show participation strongly underpins the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm and creates a bridge between competitive advantage, internal assets, and an inclination towards innovation (Teece, 2007; Barney, 1991). The confirmed nexus between export intensity and product development also supports this theory and highlights the strategic need to be flexible to penetrate international markets. In contrast, the comparatively lesser focus on digital transformation speaks to a lack of preparedness, especially in more traditional sectors. This finding is aligned with earlier research mapping peripheral areas of the European Union, where there was found to be a lack of proper implementation of Industry 4.0 strategies by SMEs (European Commission, 2024) and, thus, the need to prioritize capacity-building measures.

The study of corporate values reveals the emergence of a holistic strategic culture among regional companies characterized by a high emphasis on ethics, openness, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and employee well-being. This finding is consistent with the increased integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in the corporate structures, especially in companies located outside of the cities (Korhonen et al., 2018; D. Dimitriou et al., 2024). The alignment of the above with international standards like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the EU Green Deal emphasizes the role of ethical governance and social integration in achieving relative performance improvement, above and beyond reputational factors.

This value-based orientation is further reflected in firms’ strong support for circular economy practices, in particular the use of renewable energy, recycling, and the reuse of materials. These findings are consistent with the growing scholarly and policy literature emphasizing circular economy transitions as not just critical from an environmental perspective but also valuable from an economic viewpoint (Korhonen et al., 2018; Kirchherr et al., 2017). While the overall support level was high, the variation in significance across sectors reflects the need for sector-specific policy inducements and infrastructure investments to translate sustainability awareness into consistent practices.

In the end, the significant priority laid upon digital platforms utilized for monitoring and evaluation purposes—specifically energy consumption, ecological impacts, and infrastructural effectiveness—evinces a shift towards evidence-based informed strategic knowledge and decision-making. The proven correlation between environmental management tools and sustainability targets evinces the integration of concepts between heretofore separated disciplines. Such findings enable the development of astute regional contexts, where real-time data systems enhance public governance and strengthen proactive potentiality within the private sector (Batty et al., 2012).

In conclusion, evidence analysis supports that export-oriented firms in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace operate at the nexus of structural constraints and strengthening competencies. The size and extent of their activities are determined by regulatory systems, the character of infrastructure, systems of innovation, strategic targets, and a mounting concern with environmental issues. Such dynamics demonstrate both peripheral areas’ challenges and the latent capability to change within regional business conditions. In terms of policy development and strategic planning, the implication emerges: overcoming barriers and strengthening regional competitiveness calls upon a coherent alignment of context-dependent export development, targeted upgrading of infrastructures, stimulation of innovation, and environmental protection. This work contributes to the empirical literature on export dynamics within underdeveloped areas and calls upon comprehensive territorial development policies with a view to promoting economic development in alignment with current EU policy interests.

6. Conclusions

The research explored the operational, strategic, and institutional characteristics of export companies located in the Eastern Macedonia and Thrace Region of northern Greece, a region marked by its peripheral and cross-border nature. Based on firm-level data collected through an in-depth questionnaire survey, the analysis focused on aspects affecting international competitiveness, such as infrastructural preparedness, regulatory barriers, innovation potential, and the diffusion of sustainable practices. This study emphasizes the complex interaction between local development determinants and the internationalization processes to market, capturing both the dominant limitations as well as the emerging potential of companies operating within these territorial environments. The empirical results show that although some weaknesses remain, namely, regarding transportation and energy infrastructure, institutional fragmentation, and administrative costs related to export compliance, a significant percentage of companies have demonstrated substantial potential for international growth. Importantly, there is a growing tendency for companies to embrace innovation, sustainability, and digital technologies, all of which are increasingly becoming necessary prerequisites for sustaining competitiveness in global markets. These tendencies are of particular significance in areas that have traditionally remained outside the core regions of both Greece and the European Union.

In the policy-making framework, the findings highlight a number of key areas that call for action. The development of physical infrastructure, especially in road connectivity, digital infrastructure, and the provision of energy, is key to decreasing logistical inefficiencies and operational costs incurred by companies. At the same time, the creation of a more integrated innovation ecosystem with better cooperation between companies, research and innovation centers, and government bodies could notably enhance companies’ capacities to develop innovative products and services, absorb high-end technologies, and attain competitiveness in the international markets. It is necessary for chambers of commerce and regional development agencies to advance the coordination of their activities for providing targeted support mechanisms to small and medium-sized enterprises. Moreover, the intense interest expressed by respondents in sustainability, circular economy principles, and ecological responsibility is a considerable opportunity for policymakers. Targeted incentives concerning these challenges can encourage the introduction of environmentally sound practices as well as the international visibility of regional businesses. Finally, efforts focused on the development of regional branding and the support of involvement in international trade missions can increase visibility and market entry, especially for sectors characterized by strong local identities or specialized know-how.

In practical terms, regional administrations should weigh the creation of localized “export facilitation units” or centralized advisory offices that could be housed within chambers of commerce or regional development organizations. These units might become a convenient center of information dissemination, specialized training programs, and administrative support for SMEs considering international market outreach. Simultaneously, public financial tools should focus on value-oriented subsidies that promote the uptake of digital infrastructures (such as supply chain digitization and e-commerce platforms) as well as renewable energy systems by the export companies. In addition, capacity development programs that correspond with the productive specialization of the area—or specifically the sectors of manufacturing and logistics—can more effectively prepare companies with the necessary technical capacities and strategic assets that enable them to undertake internationalization. Integrated into comprehensive place-based development policies, these interventions have the potential to unveil dormant export potential and stimulate long-term growth in structurally disadvantaged regions.

Future research would benefit greatly from a systematic analysis of firms’ participation in industrial or business agglomerations, such as clusters, industrial districts, or local production systems. Spatial agglomerations such as these have long been known to facilitate external economies of scale in a range of ways, such as business interdependence, institutional support, and access to specialized labor markets, that cumulatively increase export orientation and regional competitiveness. The extent to which such agglomeration dynamics work in structurally cross-border regions such as Eastern Macedonia and Thrace is an open question that has far-reaching implications for territorial development and SME internationalization strategy. In short, firm integration into structurally disadvantaged regions requires more than the efforts of individual firms; it requires coordinated, place-based development policies that engage infrastructure, institutional support, innovation, and sustainability. By articulating policy architecture with the distinct needs and resources of the periphery regions and building the international ambitions of local business firms, regions such as Eastern Macedonia and Thrace can exit the periphery of export-oriented activity and become the vanguard of innovative and sustainable growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and D.D.; methodology, D.D.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K. and D.D.; formal analysis, A.K. and D.D.; investigation, D.D.; resources, A.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and D.D.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, D.D.; project administration, D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abiad, A., Furceri, D., & Topalova, P. (2016). The macroeconomic effects of public investment: Evidence from advanced economies. Journal of Macroeconomics, 50, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, H., Zandi, F., Mahdiraji, H., & Sadraei, R. (2023). Digital transformation and SME internationalisation: Unravelling the moderated-mediation role of digital capabilities, digital resilience and digital maturity. Journal of Enterprise Information Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M., Axhausen, K. W., Giannotti, F., Pozdnoukhov, A., Bazzani, A., Wachowicz, M., Ouzounis, G., & Portugali, Y. (2012). Smart cities of the future. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 214(1), 481–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J., McNaughton, R., & Young, S. (2001). ‘Born-again global’ firms: An extension to the ‘born global’ phenomenon. Journal of International Management, 7(3), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, I., Lederman, D., & Porto, G. (2012). Exports, export destinations, and skills. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3406–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros-Lobo, N., Ferreira, J., & Au-Yong Oliveira, M. (2023). SME internationalization and export performance: A systematic review with bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 15, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R. (2002). On the concept of territorial competitiveness: Sound or misleading? Urban Studies, 39(13), 2395–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, D., & Zanfei, A. (2007). Internationalisation, Innovation and Productivity: How Do Firms Differ in Italy? World Economy, 30, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy–performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaminade, C., & Plechero, M. (2012). Do regions make a difference? Exploring the role of different regional innovation systems in global innovation networks in the ICT industry. Papers in Innovation Studies 2012/2. Lund University, CIRCLE—Centre for Innovation Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dicken, P. (2015). Global shift: Mapping the changing contours of the world economy (7th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, D. (2020). Evaluation of corporate social responsibility performance in air transport enterprise. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 10(2), 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D., & Karagkouni, A. (2022). ‘Assortment of airports’ sustainability strategy: A comprehensiveness analysis framework. Sustainability, 14, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D., & Sartzetaki, M. (2022). Modified fuzzy TOPSIS assessment framework for defining large transport enterprises business value. Operational Research, 22, 6037–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D., Sartzetaki, M., & Karagkouni, A. (2024). Managing airport corporate performance: Leveraging business intelligence and sustainable transition. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-29109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D. J., Sartzetaki, M. F., & Dadinidou, S. (2022). Methodology framework to assess regional development plans: A European perspective approach. Economics and Business Quarterly Reviews, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2024). The SME twin transition monitor for the EU. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC137875 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Foray, D., David, P. A., & Hall, B. H. (2012). Smart specialization: From academic idea to political instrument, the surprising career of a concept and the difficulties involved in its implementation. MTEI Working Paper. EPFL. [Google Scholar]

- García, F., Avella, L., & Fernández, E. (2012). Learning from exporting: The moderating effect of technological capabilities. International Business Review, 21(6), 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J., Honkasalo, A., & Seppälä, J. (2018). Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecological Economics, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing returns and economic geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J. H., & Roper, S. (2015). SME innovation, exporting and growth: A review of existing evidence. International Small Business Journal, 33(1), 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medve-Bálint, G., & Szabó, J. (2024). The “EU-Leash”: Growth model resilience and change in the EU’s eastern periphery. Politics and Governance, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2017). Getting infrastructure right. A framework for better governance. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parejo, F., Rangel, J.-F., & Branco, A. (2019). Aglomeración industrial y desarrollo regional. Los sistemas productivos locales en Portugal. Revista EURE—Revista De Estudios Urbano Regionales, 45(134). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Preciado, J. F., Parejo-Moruno, F. M., Cruz-Hidalgo, E., & Castellano-Álvarez, F. J. (2021). Rural districts and business agglomerations in low-density business environments. The case of Extremadura (Spain). Land, 10(3), 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M., Dimitriou, D., & Karagkouni, A. (2025a). Assortment of the regional business ecosystem effects driven by new motorway projects. Transportation Research Procedia, 82, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M., Karagkouni, A., & Dimitriou, D. (2023). A conceptual framework for developing intelligent services (a platform) for transport enterprises: The designation of key drivers for action. Electronics, 12(22), 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M., Karampini, T., Karagkouni, A., Drimpetas, E., & Dimitriou, D. (2025b). Circular economy strategies in supply chain management: An evaluation framework for airport operators. Frontiers in Sustainability, 6, 1558706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2005). One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy, 34(8), 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2020). World development report 2020: Trading for development in the age of global value chains. World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). International entrepreneurship: The current status of the field and future research agenda. In Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset (pp. 255–288). Blackwell Publishers. Available online: http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lkcsb_research/4716 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).