Abstract

While a number of studies have analyzed the determinants of economic growth in Asia, the research on the synergistic interplay of the quality of governance and the investments in research and development have not received nuanced attention in the scholarly research. This study fills the research gap by looking at the joint effect of governance and R&D investment on economic growth in Asian nations with varying levels of development. Using the fixed-effects model and the generalized method of moments (GMM) model, this study investigated the individual and combined effect of governance and R&D investment in driving economic growth in the static as well as dynamic panel of 34 Asian nations for the period 2000–2024. The study further undertakes a comparative assessment of the lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income economies on the continent. The findings reveal that the interaction between R&D and governance is negative and significant in lower-middle-income countries such as India, Indonesia, Philippines, and Tajikistan, showing that weak institutions hinder R&D effectiveness. It turns strongly positive in upper-middle-income economies such as China, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and Thailand, as governance strengthens, but becomes insignificant, in high-income nations such as Israel, Korea, Singapore, and Qatar, suggesting diminishing returns. The results under dynamic panel estimation show positive and significant effects of the interaction between R&D and governance upon per capita GDP in all countries’ panels. The findings suggest that the diverse and nonlinear progression from technological adoption to creation in Asian nations requires sustained investments in R&D and deliberate policy alignment with national innovation systems.

1. Introduction

Studies have shown that there are several important determinants of economic growth in Asia, starting from human capital accumulation (Benhabib & Spiegel, 2005; Devassia et al., 2024; Mincer, 1993), trade openness (Gocer, 2013; Eaton & Kortum, 2001; Maskus & Penubarti, 1995; De Groot et al., 2004), demographic advantage (Pradhan & Sanyal, 2011; Akcali & Sismanoglu, 2015), to entrepreneurship (Moore, 1993; Callegati et al., 2005; Huggins & Thompson, 2015) and business innovation (Lerner, 1999; Iansiti & Levien, 2004; Clarysse et al., 2014; L. Kim, 1997). In the last two decades, the region has made strides in technical advancement and innovative potential, which are closely linked with the level of economic development. Given the diversity of the continent, the transition from emulation to creation is a nonlinear process that necessitates deliberate investment in R&D and other activities that increase technical competence (Bilbao-Osorio & Rodríguez-Pose, 2004; Bozkurt, 2015; Coe et al., 2009). While innovation is seen as both a cause and effect of economic advancement, the significance of effective governance cannot be disregarded. As an economy advances through the many phases of technical and economic growth, policies and structures pertinent to technological innovation must also change and adapt in order for technological upgrades to be successful (Han et al., 2014; Zhuang et al., 2010). The long-term sustainability and prosperity of the knowledge and human resources of a nation thus depend on effective governance structures and augment the economic growth by boosting competitiveness through R&D investments.

According to a number of studies, effective governance facilitates venture capital, creative thinking, and organizational resilience, all of which are necessary for economic success (Gompers et al., 2005; Lerner, 1999; Callegati et al., 2005; Aghion & Howitt, 1990). According to Aghion and Howitt (1990), institutions that foster competitiveness, technical advancement, and innovative disruption are essential to innovation-driven growth. In a similar spirit, Yusuf and Evenett (2002) point out that East Asia’s ability to draw in investment and maintain its economic viability was largely dependent on robust governance and open regulatory frameworks. More recent research by Mickiewicz (2023) shows that a country’s ability to draw foreign direct investment (FDI) is enhanced by high-quality institutions that include the rule of law, efficient regulations, and graft controls. This logic is further strengthened by Rodrik’s claim that institutions, which determine future advancement trajectories, financing prerequisites, and benefits, are the true underlying drivers of economic growth. All of these studies highlight governance as a persistent enabler of venture capital, creativity, and long-term economic growth across Asia. However, poor governance, which is typified by corruption, weak institutions, and inadequate policy frameworks, can significantly hinder economic growth and discourage investment, particularly in R&D, which often requires a supportive environment and consistent policy commitment (Song et al., 2023; Grindle, 2004). On the other hand, spending on research and development is a key driver of innovation and technological progress, both of which are essential for economic diversity and competitiveness (Crespi & Pianta, 2008; Romer, 1990). Particularly in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea, where large expenditures in innovation have resulted in impressive breakthroughs in facilities, technology, and goods production, R&D investment has been crucial to the transformation of Asia (Rodríguez-Pose & Zhang, 2019; Hu, 2015). Innovation fueled by R&D expands industrial capacity, raises productivity, and strengthens a nation’s ability to compete internationally. Thus, in addition to yielding immediate financial gains, R&D investment affects the long-term structural transformation of economies (Degong et al., 2021; Shaw, 1973; Reinhart & Rogoff, 2009).

Indeed, there is a reciprocal and mutually advantageous link between good governance practices and R&D investment (Becheikh et al., 2006; Burnside & Dollar, 2000; Minniti & Palubinskas, 2023). Spending on research and development from the government and private sectors is encouraged by stable environments created by strong governance systems (Center for International Development, 2015; Mohammed & Virtanen, 2016). At the same time, R&D investment fosters the development of technology skills, creativity, and human resources, all of which have the potential to enhance governance procedures, increase productivity, and fortify the institutional capacity of governments (Cvetanović et al., 2019; Knack & Keefer, 1995; North, 1990). This chain of feedback is particularly relevant in Asia, where countries with robust governance systems, such as South Korea and Singapore, have effectively employed R&D as a means of advancing their economic objectives (L. Kim, 1997; Hu & Jaffe, 2003). However, countries with weaker governance structures may find it challenging to invest in R&D since graft, waste, and improper allocation of resources might limit the prospects for innovation (Giordano et al., 2020). Economic growth and research and development (R&D) investment have been shown to be strongly correlated by growth theory (Capolupo, 2009; Diebolt & Perrin, 2016), but, in emerging countries, the strength of this relationship is significantly impacted by the quality of governance (Adams & Mengistu, 2008; Fayissa & Nsiah, 2013; Xu et al., 2023). Governance determines whether or not R&D spending leads to real innovation, productivity gains, and ultimately economic advancement (Bichaka & Christian, 2013). Thus, the intersection of technological effort and institutional quality is crucial to the sustainable growth routes of the Global South. Developing Asia provides a unique trial site for this combination due to its diverse governance systems and varying levels of inventive maturity. For instance, certain countries, like South Korea and Singapore, have leveraged innovation and good governance to achieve remarkable economic success, while other countries still struggle with low innovation potential and governance shortcomings. It is crucial to remember that not all research studies indicate that R&D spending significantly boosts growth. Das and Mukherjee (2020), for instance, contend that R&D expenditures do not consistently affect income across the world’s top economies and groups. Das (2020) also notes that the connection between R&D expenditures, patents, and income growth is still complicated and occasionally statistically insignificant. These results highlight the necessity of placing the relationship between innovation and growth within particular frameworks of governance and development, such as those seen in developing Asia. This article investigates the synergistic impact that innovation, research, and governance play in supporting economic advancement throughout developing Asia by analyzing empirical data and highlighting their linked contributions to the region’s development pathway.

The study adds to academic discourse in four ways by illuminating the relationship between government effectiveness and research and development investments. First, the study fills an important research gap by looking at the joint effect of governance and R&D investment on economic growth in Asian nations with varying levels of development. Second, the study helps in ascertaining the level of interaction between governance and R&D expenditure that can be expedient for economic growth. Third, the study brings out the comparison of countries based on income levels to give a nuanced insight into the advantages and limitations faced by nations at different stages of economic development. Fourth, the analytical framework provides both static and dynamic perspectives by complementing the fixed-effects PCSE model with the GMM model. By adjusting for longitudinal dependency as well as controlling for country-specific variation, fixed-effects PCSE improves the baseline estimations, and, in addressing endogeneity and reverse causality, GMM provides more reliable estimations of the combined effects of R&D and governance on economic development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. R&D Investments and Economic Growth

There exists rich economic literature on the effects of R&D expenditure on enhancing productivity and leading long-term growth (Kumar et al., 2024; Guellec & Van Pottelsberghe, 2001; Griliches, 1998; Griliches & Mairesse, 1984; Griffith et al., 2004). Purposive innovation lies at the heart of long-run growth in endogenous growth models. Aghion and Howitt (1992) characterize development through “creative destruction,” in which R&D enhances productivity as older technologies are replaced by better ones, while Romer (1990) illustrates how knowledge investment (a non-rival, partially excludable input) multiplies output through increasing variety. Taken together, these models predict that greater governmental or private R&D activity should raise trend productivity and revenue. Research within and across borders shows that both localized and imported knowledge bases contribute to productivity growth (Wakelin, 2001; D. H. Wang et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2023). Earlier studies showed substantial domestic and international R&D spillover effects (Coe et al., 1997), and there are a number of studies that largely use recent panel techniques to support the original findings (Javorcik, 2004; Ozcan & Ari, 2014; Çeştepe et al., 2024). From the perspective of R&D’s “two faces,” OECD economies’ industry-level panels suggest that, along with producing innovation, R&D also expands the absorptive capacity and speeds catch-up (Kneller et al., 1999; Fadic et al., 2019; E. Li et al., 2022). Newer studies continue to document positive returns to R&D, including public/government R&D (Bucci et al., 2023; Hoang & Yarram, 2024).

2.2. Governance and R&D Investments

Another important body of research demonstrates how institutions such as the rule of law, anti-corruption efforts, and regulations affect the national economic growth (Rigobon & Rodrik, 2005; Jalilian et al., 2007; Shabbir et al., 2025). Groundbreaking studies state that when properly gauged, the quality of institutions exceeds commerce and locational advantage (Méon & Sekkat, 2004; Zhuang et al., 2010). The absence of corruption and bureaucratic quality is seen to affect investments for development (Rodríguez-Pose & Zhang, 2019; Aiello & Bonanno, 2019). Theoretically, endogenous growth models (Romer, 1990; Aghion & Howitt, 1992; Barba-Sánchez et al., 2024) emphasize governance as a driver of knowledge generation and dissemination, while neoclassical perspectives view governance as ensuring efficient resource allocation and reducing uncertainty. Establishing the link between governance and innovative capacity, studies find that secure property rights, enforceable intellectual property (IP) protection, and predictable regulations are necessary for innovative activity, and these depend on the quality of the institution (Aghion & Howitt, 1992; Acemoglu et al., 2001; L. Wang et al., 2025). The lack of these institutional supports lowers firms’ expected returns to innovation, which results in underinvestment in R&D in many developing economies (Tang et al., 2022).

From a theoretical perspective, government effectiveness is considered a prerequisite for building the innovation capacity of a nation, which leads to R&D expenditure as well as economic growth (Gani, 2011; Ndulu & O’Connell, 1999; Smith, 2007; Bai et al., 2025). For Asian nations, governance has also been found to be a precondition for receiving aid and grants for developing the knowledge and human capital through investments in R&D (Burnside & Dollar, 2000; Alesina & Dollar, 2000; Santiso, 2001). Good and effective governments support economic growth both at the national and regional levels (Wilson, 2016; Lee, 2009; Y. Kim, 2024). While non-distortionary taxes and effective government spending and transfers may more precisely reflect consumer choices, they also imply that more or better public goods and services are being allocated at the same level of expenditures (Diamond & Mirrlees, 1971). This extra or higher-quality government output boosts GDP and income in the long run (Anderson et al., 2018).

2.3. Interplay of Governance and R&D Investment for Economic Growth

While the linkages of R&D investments and quality of governance have been independently studied by scholars, creating an extensive body of literature, the effect of governance in the innovation–growth channel has been explored in very few studies (Anokhin & Schulze, 2009; Setayesh & Daryaei, 2017; Celikel, 2007; Wan et al., 2025). Recent studies emphasize that the size of the effect of R&D on growth depends on the quality of governance, including government effectiveness, rule of law, regulatory quality, and control of corruption (Zhu et al., 2024; Danta & Rath, 2024; Kaira & Omoke, 2020). These institutional variables help in making the mechanism through which R&D spending is converted into innovation, productivity improvements, and long-term development more robust (Elfaki & Ahmed, 2024).

Studies have found that government R&D usually makes up a larger share of total innovation investment in emerging countries because private sector innovation is still in its infancy (Zuniga, 2022; Anand et al., 2021). However, poor governance systems, which are marked by low accountability, inefficient bureaucracy, and corruption, reduce the effectiveness of public R&D spending (Cruz et al., 2023). As per the findings of the literature, funds intended for science, technology, and innovation (STI) programs may be embezzled by affluent people, misappropriated, or directed toward politically motivated projects with no developmental value (Boeing, 2021; OECD, 2022). Effective governance, on the other hand, ensures that R&D funds are allocated strategically, transparently monitored, and linked to national development objectives, thereby boosting the productivity of every R&D expenditure unit (Hwang et al., 2021; Dokas et al., 2023).

Businesses are more willing to invest in long-term technology projects when governance systems that uphold contracts, safeguard intellectual property, and encourage competition are in place (Teece, 2020; Fieldhouse & Mertens, 2023). Because of their state capacity and governance reforms, which established credible innovation environments that transformed R&D into productivity gains, economies such as South Korea and Singapore were able to quickly catch up technologically (Rodrik, 2008; Kong et al., 2022). The political environment in which R&D expenditures are made can inhibit creativity due to clientelism, short-termism, and rent-seeking (X. Zhang & Xu, 2022). Many developing countries’ policymakers are persuaded to fund short-term infrastructure projects over long-term R&D projects (Goñi & Maloney, 2017). Strong governance institutions reduce this bias by integrating meritocracy, continuity, and transparency into the creation and implementation of policies (North, 1990; Rodrik, 2008; H. Khan et al., 2022). Therefore, governance not only ensures efficient spending but also stabilizes innovation policy across political cycles.

Studies on the nexus between governance, innovation, and economic growth have utilized a range of methods. There are some that utilize panel data models or case studies to monitor how reforms in governance structures have set off technological upgrading in specific economies (Rahman & Hossain, 2024; Dempere et al., 2023), while others utilize cross-country regressions based on World Bank governance indicators to estimate institutional effects on innovation (Boudreaux, 2017; Donges et al., 2023). The threshold effects of government quality have also been contested in the literature. Some scholars argue that any improvement in institutional integrity fosters innovation, while others argue that it is only when innovation systems achieve a certain level of effectiveness that they become self-sustaining (Arshed, 2022; H. Zhang & Wang, 2019; C. Li et al., 2021).

The following hypotheses are taken to proceed with the examination of the individual and combined effect of government effectiveness and R&D expenditure on economic growth:

H1.

Higher government effectiveness is positively associated with economic growth in Asian economies.

H2.

Higher R&D expenditure is positively associated with economic growth in Asian economies.

H3.

The interaction between government effectiveness and R&D expenditure has a nonlinear effect on economic growth across income groups.

2.4. Research Gap

Although there exists a vast literature on the independent contributions of R&D spending and governance to economic growth, relatively few works have investigated their combined or interactive impacts, especially on developing economies in Asia. R&D and governance are, in most existing studies, treated as distinct determinants or drivers of growth rather than complementary stimulants of growth. This research aims to fill that void by examining how the quality of governance—through channels such as government efficiency, quality of regulation, and corruption control—conditions the effect of R&D expenditures on economic performance. Beyond that, empirical evidence is still limited as to how the relationship holds in different countries that are at varying levels of economic development. By comparing countries on the basis of their income levels, this paper attempts to offer a balanced understanding of institutional quality’s impact on the translation of innovation investment into growth performance. It, therefore, adds to the limited but emerging literature connecting governance, innovation, and economic performance in developing Asia.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Variables

The data for the 34 nations in developing Asia is obtained from the World Bank. The variable of economic growth in the study is measured in terms of the GDP per capita in USD. By displaying average income and productivity per person, GDP per capita allows for cross-country comparisons and serves as an effective indicator of economic well-being than total GDP. The R&D expenditure is measured by the gross domestic expenditure on research and development as a proportion of GDP. This includes both capital and continuing expenditures in the four main sectors: industry, government, higher education, and private non-profit. In addition, it encompasses experimental development, applied research, and basic research.

The estimate of government effectiveness as given in the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) database was measured on a scale ranging from −2.5 (poor governance) and +2.5 (good governance). While the WGI database captures six parameters of governance, viz., Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption, this study utilized the measure of government effectiveness as a an indicator of governance because it captures the quality of institutions that lies at the heart of policy formulation, implementation, and the overall perception of government legitimacy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables used in this study.

To isolate the impact of R&D investment and governance on economic growth, a number of macroeconomic and social indices are employed as control variables (Blank & Blinder, 1985; Jäntti, 1994). As given in Table 1, these include population growth (a gauge of demographic pressures), net foreign direct investment (FDI) flows (a gauge of foreign technology transfers and external economic integration), inflation (a gauge of macroeconomic stability), and tertiary school enrollment ratios (a gauge of the expansion of human capital). Population growth takes into consideration the dynamics of growth, consumption, and labor supply. The net FDI inflows are useful, as they indicate how global integration, technological diffusion, and foreign capital impact growth outcomes. Inflation represents the macroeconomic stability that affects buying power, investment choices, and ultimately overall economic performance. As a key factor in productivity, growth, and the capacity to absorb innovation, enrollment in postsecondary education measures the human capital accumulation.

3.2. Sample

The study employed balanced panel data from the 34 nations in developing Asia, for a period of 25 years (2000–2024). The countries that have been considered for the study are mentioned in Table 2. The countries included in the study were selected for the diversity in geography, economic development, and the availability of data on all variables. In addition, the selected countries covered more than 90 percent of the total GDP of Asia in the year 2024. Encompassing South, Southeast, Central, West, and East Asia, the nations are diverse in institutional quality, cultural norms, and innovation policies, which make it possible to identify more context-specific trends and insights that are pertinent to the study. Most importantly, in line with the objectives of the study, the choice of countries reflects the variety of governance arrangements, capacity for innovation, and income levels found in the region. The sample covers high-income innovation leaders like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Israel; upper- and lower-middle-income economies like China, India, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia; and emerging and resource-based countries like Kazakhstan, Oman, and Saudi Arabia. This heterogeneity allows for the intensive examination of how governance quality conditions R&D spending under varying economic and institutional settings.

Table 2.

List of countries. Source: authors’ compilation using the database of the World Bank.

This study utilizes the World Bank income classification for countries, as it is the most widely used classification based on the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. Lower-middle-income nations have a GNI per capita between 1136 and 4495 USD, upper-middle-income countries have a GNI per capita between 4496 and 13,935 USD, and high-income countries have a GNI per capita of over 13,935 USD, according to the World Bank’s classification system (Table 3).

Table 3.

Classification of countries by income groups. Source: authors’ compilation using the database of the World Bank.

3.3. Theoretical Framework

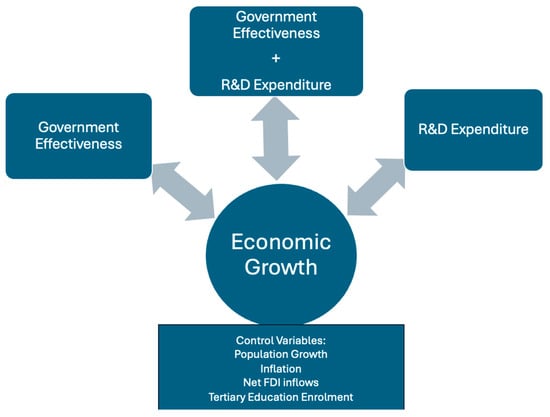

Let us develop a theoretical framework on the linkages of economic growth with R&D expenditure and government effectiveness. Figure 1 displays the synergetic connection between economic growth, R&D spending, and the effectiveness of government. Good governance improves the effectiveness and efficiency of research and development investments by providing favorable policies, institutional stability, and efficient resource allocation. Subsequently, higher R&D spending leads to innovation, productivity, and competitiveness, which propel economic growth. Economic growth subsequently further enhances the ability for additional R&D investment and better governance apparatuses, leading to a virtuous cycle. Therefore, governance quality and innovation capacity interaction is central to maintaining long-term economic development and fortifying a country’s development path.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Sketched by the authors.

Let us consider a general form of the income growth (gdppc) function as dependent on the selected indicators pointed out in Figure 1, with good governance, R&D, and the interaction between governance (goveff) and R&D (goveff ×rd) being the key factors and population growth (popgwth), inflation rate (infltn), net FDI (fdi_net), and enrolment ratio in tertiary education (ser_t) being the control variables. The mathematical form of the function is as follows:

Given the role of the control variables, the above function is reduced to

where Y is gdppc, dY/dgoveff > 0, dY/drd > 0, and dY/d(goveff ×rd) > 0. The rate of growth of Y is written as follows:

The empirical models are framed on the basis of the above theoretical model.

3.4. Empirical Model

To calculate the impact of government effectiveness and R&D expenditure on economic growth, this study has employed the following two empirical models for the panel data regression analysis:

Model I:

Model II:

where Yit is economic growth, as measured by GDP per capita (gdppc); Xit denotes the determinant of governance, viz., effectiveness of the government (goveff); and rd denotes the R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP. The control variables include population growth (popgwth), inflation to GDP (infltn), net FDI flows (fdi_net), tertiary education enrolment ratios (ser_t); αi denotes the country-specific fixed effect, capturing unobserved heterogeneity; and εit is the error term.

For the estimation of Equations (4) and (5), we followed two approaches—the static panel estimation and the dynamic panel estimation. The static panel has two components: one is the fixed-effect model, and the other is the random-effect model. Using the Haussmann test, the fixed-effects PCSE model is preferred because it accounts for unobserved country-specific heterogeneity and corrects for both heteroskedasticity as well as coexistent correlation across countries. This method leads to standard errors that are more robust and coefficient estimates that are less biased, with respect to those obtained from traditional FE or RE models, making it an attractive model for macroeconomic panels featuring common global shocks and heterogeneous country-level patterns.

Further, as the data series has a moderate length, it can have the impacts of the lagged dependent variables on the current value of the per capita GDP, along with the other control variables selected. The static panel estimation technique does not capture the effect of the lagged dependent variable. Thus, we have also estimated both Model I and Model II using the GMM (generalized method of moments). Again, as the number of independent variables is relatively large, the GMM estimation technique is compatible with the panel of all 34 countries, which is not the case in the other panels. Thus, we have derived and displayed the GMM estimation results for the panel of 34 countries only. The results for both the ‘difference approach’ and ‘orthogonal deviation approach’ are shown. The variance inflation factor is also computed to determine whether there is any sort of collinearity among the selected independent variables in the panel of the 34 countries.

The research variables’ descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4. Research spending is relatively low, as shown by the average R&D investment of 0.74% of GDP, though this varies a lot from one country to another. The average GDP per person is about USD 15,294, which creates noticeable differences in income levels. There is also considerable variation between countries in the average tertiary education enrollment rate, which stands at 38.3%, suggesting that participation in higher education is not widespread. While government performance, measured by the average government effectiveness score of 0.13, shows a mixed picture of institutional quality, average net foreign direct investment inflows, at 6.89% of GDP, show a lot of ups and downs. The average population growth rate is 1.55%, which matches a fairly steady rate of population increase. An average inflation rate of 7.28% indicates that macroeconomic stability differs widely across countries. Overall, these figures highlight uneven patterns of development, institutional quality, and macroeconomic performance across the sample nations.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics. Source: authors’ own estimations.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) test was applied to test for the existence of multicollinearity between the explanatory variables. The VIF values are between 1.05 and 1.85, with a mean VIF of 1.33. Because all of the VIF values are much below the generally accepted cut-off of 5, there is no issue of multicollinearity in this model, meaning that the independent variables are not significantly correlated with each other.

The correlation matrix between the variables is shown in Table 5. More affluent economies tend to have more effective governments, increased investment in education, and higher innovation capabilities, as demonstrated by the good positive correlations that GDP per capita exhibits with government effectiveness (0.70), the ratio of tertiary enrollment (0.36), and R&D spending (0.38). The endogenous growth theory (Romer, 1990), which states that economic growth is closely associated with human capital and innovation spending, corroborates this finding. Further, government effectiveness is positively correlated with the ratio of tertiary enrollment (0.45) and R&D (0.55), highlighting the role of high-quality institutions in advancing research and education. New institutional economics, as espoused by North (1990), contends that both formal and informal institutions set the rules of the game and serve as important determinants of economic performance. The majority of factors have negative associations with inflation, especially GDP (−0.21) and governance (−0.35), suggesting that less developed, poorly run nations are more likely to experience macroeconomic instability. Acemoglu et al. (2001) have stated the same argument in their political economy perspective, which maintains that weak governance and extractive institutions lead to fiscal mismanagement and macroeconomic instability. Population growth has a positive correlation with GDP per capita (0.28), which again supports the endogenous growth idea (Lucas, 1988) that population growth can trigger long-term growth in contemporary economies that are knowledge-based by expanding the stock of human capital. According to the Neoclassical viewpoint (Solow, 1956), FDI complements domestic savings and speeds up the process of capital formation, increasing the steady-state level of output per capita. Hence, the positive link between FDI and income levels (0.11) captures both greater capital formation and technology diffusion, which together determine long-run economic performance.

Table 5.

Correlation results. Source: authors’ own estimations.

4. Findings

4.1. Results of Static Panel Estimation

The findings of the panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) model that looked at the connection between R&D spending, government efficacy, and economic development across various income categories are shown in Table 6. Better institutional quality significantly boosts economic growth, as evidenced by the large positive and very significant association between government effectiveness (coefficient = 12,783.47, p < 0.01) and GDP per capita for all income categories combined. However, R&D expenditure has a negative and significant coefficient (−4421.648, p < 0.01), indicating that increased R&D investment may first put a burden on resources before producing benefits in emerging environments. The findings demonstrate that while the impact of R&D spending varies depending on the stage of development, government efficacy has a consistently beneficial and substantial impact on economic development for all income groups. The lack of R&D in lower-middle-income nations supports Nelson and Phelps’ (1966) theory that technological progress would only be profitable if sufficient organizational ability and human resources were available. Cohen and Levinthal’s (1990) absorbent capability hypothesis, which holds that excellent governance enables nations to integrate and commercialize technical knowledge, is in line with the positive and considerable R&D effect in high-middle-income nations. Expanding education promotes growth, as seen by the tertiary enrollment ratio, which is continuously positive and substantial across the majority of groups. While population increase has a negative impact on GDP, reflecting demographic pressures, government effectiveness is still significantly favorable in the lower-middle-income group. Both post-secondary education and R&D spending (both positive and considerable) are powerful growth drivers in upper-middle-income nations, underscoring the significance of innovation and human capital at intermediate stages of development. While population growth and government efficacy have a positive impact on GDP in high-income nations, R&D has a negative coefficient, which may be a reflection of mature economies’ declining marginal returns on research expenditure.

Table 6.

The independent effect of R&D expenditure and government effectiveness on economic growth. (PCSE). Source: authors’ own estimations.

The PCSE model findings examining the combined impact of government effectiveness (rd × goveff) and R&D investment on economic growth across income categories are shown in Table 7. The interaction term is positive and highly significant (4083.426, p < 0.01) for all nations, suggesting that the research spending significantly boosts economic development when it is managed well. This conclusion may also mean that a high R&D backed by good-quality human capital may have impacts on governance performance; thus, there can be a cause-and-effect-type relationship between R&D and governance effectiveness. This demonstrates how innovation and institutional quality work hand in hand—in well-governed contexts, R&D expenditure produces better returns. The interaction term is negative and significant (−3377.413, p < 0.05) in the lower-middle-income group, indicating that inadequate institutions may make it more difficult to use R&D expenditure effectively, which would restrict the growth gains. According to Acemoglu et al. (2001), profit-seeking, policy ambiguity, and bribery reduce the efficacy of R&D allocation in settings with weak structures: public assets are being improperly utilized or neglected. Conversely, the relationship is positive and highly significant (3088.944, p < 0.01) in upper-middle-income economies, reflecting that R&D finally begins to propel development as government becomes tighter. This finding aligns with Lundvall (1992) national innovation systems perspective, whereby good governance facilitates the links between universities, industry, and policy institutions required for growth driven by innovation. The relationship is beneficial but statistically insignificant in high-income economies, possibly a reflection of diminishing returns in instances where innovation and government have highly progressed; as Aghion and Howitt (1992) and Romer (1990) illustrate, developed economies undergo endogenous cycles of innovation in which institutional merit supports, not accelerates, long-term growth. Tertiary enrollment ratios of all groups remain positive and significant, reflecting the key role human capital plays in supporting growth. Overall, the findings underscore the fact that R&D investment alone is not sufficient, and the quality of institutions as well as governance are fundamental for its growth-promoting effect.

Table 7.

The combined effects of R&D expenditure and government effectiveness on economic growth. (PCSE). Source: authors’ own estimations.

4.2. Results of GMM Estimation

We now present the estimated regression results using the GMM technique offered by Arellano & Bond (1991). The Arellano–Bond estimator is designed for datasets with many panels and few periods, and it requires that there be no autocorrelation in the idiosyncratic errors. Since we have a relatively shorter length of time (2000–2024), we used the Arellano & Bond (1991) technique for the GMM estimation. The results are derived using both the ‘first difference method’ and ‘orthogonal deviations’, which are for the panel of all 34 countries only, as we have many instrumental variables compared to the data length. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

The GMM estimation results. Source: authors’ own estimations.

The results from the GMM estimations following Model I, for all the countries’ panels, show that all the independent variables, along with the lagged dependent variable, are statistically significant, like those of the results of the static panel estimation. The results for the specification of ‘orthogonal deviation’ are identical, except for the effect of net FDI, which is insignificant and resembles that of the static panel results. Further, the estimated results of Model II, to categorically find the changes due to the introduction of the interaction term (rdxgoveff), show that all independent variables, including the lagged dependent variable, are significant in determining the per capita GDP of the selected 34 Asian countries. There is a positive and significant impact of the interaction effects between research and development and government effectiveness upon the per capita GDP of the countries. The results are thus robust as they go well with static as well as dynamic panels.

5. Results and Discussion

These findings suggest significant heterogeneities in the impact of government effectiveness and R&D spending on economic growth across different income groups. The findings are in line with the proposition that high institutional quality is the key ingredient of economic success and that the effect of research and development investment on growth is significantly based on the country’s stage of development and the capacity of the country to transform and assimilate innovation into productivity improvement (Fayyaz & Bartha, 2025; Alam et al., 2019). The results go well for both the static panel and dynamic panel estimations. The dynamic panel results are valid for the panel of 34 countries, unlike those of the static panel, because of the specification requirements. The results have important policy implications. Governance determinants are found to be strong and stable drivers of economic growth in the country. Economies with open governance, good public institutions, and efficient bureaucratic machinery are likely to entice investors, expand production, and maintain growth. This corroborates the significance of governance reforms as preconditions for sustainable growth, particularly in the context where corruption and inefficiency of institutions sabotage the efficient utilization of public resources (M. A. Khan et al., 2023; Chang, 2023; Mini et al., 2024). Nevertheless, research and development spending is negatively correlated with growth, and that research investment might initially focus on the economic and human resources of developing and emerging economies before having a concrete economic impact (Ge & Liu, 2022; Chomen, 2022; De Haan & Siermann, 1996; Fawaz et al., 2021). The paper uncovers the imbalance between innovative investments and the uptake of technologies that are dispersed or upgraded in the manufacturing sector.

The capacity of institutions to create a safe, open, and stable environment for economic activity is the key reason they are a pillar of economic performance. Institutions reduce the costs of transactions, protect property rights, and foster trust among the government, investors, and citizens (Bhujabal et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2021). These are typified by effective bureaucracy, rule of law, accountability, and competent governance. These institutional features enhance the legitimacy of public policy, encourage private sector participation, and facilitate the effective allocation of resources (Huang, 2010; De, 2006; Ginsburg, 2011). Markets can operate with lower uncertainty, corruption is controlled, and policy implementation becomes predictable when governments are well-performing (Park & Mercado, 2014; Mehmood et al., 2022). Therefore, both domestic and foreign investors are better positioned to invest long-term resources, encouraging productivity and growth (Nguyen et al., 2018; Asiedu, 2013). Conversely, poor institutions diminish the efficiency of the market by promoting rent-seeking, unstable policy, and misallocation of capital, all of which reduce economic performance (Rodrik et al., 2004; Wei & Wu, 2002). Nevertheless, the relationship between R&D spending and economic growth always stands on the basis of a country’s level of development as well as on the capacity of the country to absorb and utilize new information (Blanco et al., 2013; Tsai & Wang, 2004). Younger economies often do not have the ancillary resources—such as highly educated staff, advanced infrastructure, and robust intellectual property legislation—to turn research input into innovative output (Tullao, 2013; Urata & Baek, 2022). Thus, without delivering quick productivity increases, R&D spending in such cases can strain thin financial and human capital (Ulku, 2004; Minviel & Ben Bouheni, 2022). By contrast, as they move higher along the value chain and enhance their technical capabilities, middle-income countries with more solid institutional systems and education systems begin to realize increasing returns on investment in innovation (J. U. Kim & López-Bazo, 2020; M. S. Khan, 2022). The problem changes once again for advanced economies: as technology matures and becomes saturated, conventional R&D’s marginal benefits may decrease. At this point, the emphasis has to change to maintaining innovation through knowledge dissemination, digitization, and diversity (Zheng, 2024; J. Wang, 2021). Therefore, developmental capability and institutional quality function together; absorptive capacity determines how well innovation converts into long-term economic growth, while governance establishes the enabling environment that allows R&D to be deployed.

Additional information may be gained by breaking down the results by income category. Because lower-middle-income countries frequently struggle with institutional instability and insufficient administrative capacity, governance reforms are still crucial to maintaining growth in these countries (Raballand & Zovighian, 2024; Gonzalez Parrao et al., 2022). The attempts to research and develop human capital are both drivers of growth for high-income nations and reflect a transition toward innovation-driven development (Nelson & Phelps, 1966; Pradhan & Sanyal, 2011). Nevertheless, the diminishing returns on R&D in high-income countries reflect that innovation strategies must shift from the growth of incremental research investment to diversification, sustainability, and digital shift (Bloom et al., 2017). From a policy perspective, the results of individual effects underline the need for a progressively developed strategy, with higher-income nations pursuing advanced and efficiency-focused innovation strategies, middle-income nations developing innovation ecosystems and educational infrastructures, and low-income nations enhancing governance and institutional capacities. Therefore, effective policy coordination between education, innovation investment, and institutional transformation is still essential in order to secure equitable and sustainable economic growth.

The influence of government efficiency and expenditure on research and development on economic development in income groups has been strongly debated to be critical, but the relative role of innovation in relation to governance abilities is important in determining outcomes of growth, though the influence varies immensely with level of development (Fakhimi & Miremadi, 2022). The correlation between spending on R&D and the quality of the government is extremely strong and positive in the entire sample, showing that investment in research can be a strong driver of economic development when placed in an efficient institutional setup (Zhu et al., 2024). This stresses the fact that research and development per se cannot achieve long-term growth unless complemented by an open and functional governance framework that supports intellectual property rights, enables the distribution of technology, and effectively allocates resources (Aghion & Howitt, 1992; Acemoglu et al., 2001; Teece, 2020; Fieldhouse & Mertens, 2023). Without a well-established institutional setting, research and development spending often does not result in innovation or productivity increases due to inefficient bureaucracy, corruption, or poor regulatory coordination (Rigobon & Rodrik, 2005; Jalilian et al., 2007).

Conversely, lower-middle-income groups have negative interaction effects. The section shows that, when institutional effectiveness is matched with scarce funding and human resources, higher research and development spending may slow growth in the first place and lower the full impact of limited financial and human resources, and developing the most urgent needs. These economies tend to lack the infrastructure, information networks, and skilled labor to transform research inputs into valuable products (McGuinness et al., 2019). There are considerable positive effects of interaction between the middle-income and higher-income categories, which verify that institutional maturity enhances the productivity benefits of investment in R&D. In these contexts, effective governance promotes links between universities and industries, guarantees accountability for public research funding, and promotes competitive innovation systems (Rossoni et al., 2024).

5.1. Scientific Contribution of the Study

The findings demonstrate how the broader institutional framework is essential to the operation of innovation policy in both the static panel as well as dynamic panel estimations. To produce meaningful economic outcomes, R&D investments must be supported by robust governance structures that ensure transparency, accountability, and efficient resource allocation. Strong institutions foster trust, protect intellectual property, and facilitate collaboration between public research bodies and the business sector (Tolin, 2025). In emerging and transitional economies, where institutional flaws often impede the diffusion of innovation, strengthening governance capabilities becomes essential to closing the gap between research efforts and economic impact. Thus, through institutional anchoring, innovation policy associated with good governance practices becomes a long-term driver of equitable growth.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study using both the static and dynamic panels for the proposed two models, Model I and Model II, a host of policy recommendations can be made. First, the study suggests that a context-driven approach must be adopted that brings together governance reforms and innovation strategies. Asian nations cannot invest their way to growth in R&D unless it is performed in an institutional setting that supports such investment. Accordingly, innovation-stimulating policies need to be shaped in line with the governance capability of the country, ensuring that advancements in transparency and accountability, regulatory stability, and bureaucratic efficiency are commensurate with investments in research and technological development. Thus, there is a need to give priority to strengthening government effectiveness in lower-middle-income economies. Second, the results also imply that many of the Asian countries lack absorptive capacity. Therefore, reforms need to be aimed at accelerating the coordination between ministries such as education, industry, and science. This entails institutionalizing governance and R&D spending in the national development planning. The interplay between government effectiveness and innovation expenditure requires a policy integration as opposed to being an afterthought. This would involve regular government reviews of the impact that institutional performance is having on R&D funding productivity, in order to diagnose any bottlenecks and make sure investment stays focused on sectors with a high potential for innovation-led growth. Third, the study findings indicate that we must explore the differentiated innovation strategies within Asia across income levels for their desired effects. High-income country development must move beyond incremental R&D intensification and focus on advanced innovation models, such as digital transformation, sustainability, and knowledge spillovers. Countries in the middle-income group should create an innovation climate that will lead to technology upgrading and increased technical education. Lastly, low-income economies simply have to do the basic work of governance strengthening before becoming emboldened with large investments in innovation. Finally, regional cooperation can be reinforced for the symmetrical development of technology in Asia because of differences in income and innovation capabilities across Asia. The developed Asian economies need to ease technology transfer, have more skill development programs, and open innovation collaborations and policy learning platforms for the developing countries in order to mitigate the existing regional imbalances. It will contribute to leapfrogging stages of lower-income technological development and thus accelerate the catch-up trajectory.

6. Conclusions

The economic development of Asian nations has accelerated recently, leading scholars to investigate the connections between economic growth and innovation or between economic growth and governance. However, given the diverse and heterogeneous combination of nations in Asia in terms of the national income levels, the policy and governance matter to a large extent for any kind of innovative capacity to develop and become sustainable. The study thus looked at the joint effect of R&D investments and government effectiveness on economic growth in Asian nations using static, as well as dynamic, panel estimation techniques. As per the findings of the empirical analysis, looking at the broad picture of Asia’s innovation and economic development, the differences in government effectiveness, including the different types of governance structures, lead to different trajectories of economic growth. The synergy between governance and innovation plays a vital role in driving economic growth in nations, but their individual and therefore combined effects vary across income groupings. In less developed Asian nations, the R&D investments may not contribute towards enhanced economic development due to the infant status of innovation learning and application ecosystem. Strong institutional and optimal use of resources that come under effective governance can expedite the impact of innovation for these nations. The economically advanced nations are able to reap more long-term benefits from the R&D investments, owing to their robust and mature technological systems as well as stable and efficient institutional mechanisms. In the final analysis, it can be said that there is no one-size-fits-all blueprint for leveraging innovation for growth. The sustainable development of the economy and innovative capacity in the current knowledge economy requires a judicious mix of governance and R&D investments to suit the stage of development of a nation.

Limitations and Future Scope

Despite the substantial contributions this study offers, it has several limitations. First, the study findings cannot be generalized to other regions due to limited sample coverage. Second, the static model may not capture the dynamic relationships, for both the long run and short run, between growth, governance, and innovation. Third, the income groupings may shroud the intra-group heterogeneities that exist due to diverse socio-political systems. Future research can include additional external and control factors to examine the political, cultural, and historical determinants of economic growth in Asia. An ideal research approach that aids in a thorough examination of the governance and innovation challenges in Asia would entail a segmented examination of the panel data according to their geopolitical dimensions and level of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.; methodology, V.S.; formal analysis, V.S. and R.C.D.; investigation: V.S. and R.C.D.; resources, P.D. and R.C.D.; data curation, P.D. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and R.C.D.; supervision, R.C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

It is declared that this research did not involve humans or any other animals in its course and does not have any conflicts of interest with anybody in society.

Data Availability Statement

The source of the data for population and GDP is the World Bank (www.worldbank.org), it is an open source where no issue on permission appears.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. The American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2677930 (accessed on 10 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Adams, S., & Mengistu, B. (2008). Privatization, governance and economic development in developing countries. Journal of Developing Societies, 24(4), 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1990). A model of growth through creative destruction (No. w3223). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, F., & Bonanno, G. (2019). Explaining differences in efficiency: A meta-study on local government literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcali, B. Y., & Sismanoglu, E. (2015). Innovation and the effect of research and development (R&D) expenditure on growth in some developing and developed countries. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 768–775. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, A., Uddin, M., & Yazdifar, H. (2019). Institutional determinants of R&D investment: Evidence from emerging markets. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 138, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth, 5(1), 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J., McDermott, G., Mudambi, R., & Narula, R. (2021). Innovation in and from emerging economies: New insights and lessons for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(6), 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E., Jalles d’Orey, M., Duvendack, M., & Esposito, L. (2018). Does government spending affect income poverty? A meta-regression analysis. World Development, 103, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, S., & Schulze, W. (2009). Entrepreneurship, innovation, and corruption. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshed, N. (2022). Exploring the potential of institutional quality in determining innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, E. (2013). Foreign direct investment, natural resources and institutions. International Growth Centre Working Paper, 3, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J., Cai, Q., Yao, N., & Guo, Q. (2025). Government industrial priorities, public corporate governance and corporate innovation: A political push perspective. Economic Analysis and Policy, 85, 1885–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Meseguer-Martínez, A., Gouveia-Rodrigues, R., & Raposo, M. L. (2024). Effects of digital transformation on firm performance: The role of IT capabilities and digital orientation. Heliyon, 10(6), e27725. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38509885/. [CrossRef]

- Becheikh, N., Landry, R., & Amara, N. (2006). Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003. Technovation, 26(5–6), 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, J., & Spiegel, M. M. (2005). Human capital and technology diffusion. In Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 1, pp. 935–966). Elsevier North-Holland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujabal, P., Sethi, N., & Padhan, P. C. (2024). Effect of institutional quality on FDI inflows in South Asian and Southeast Asian countries. Heliyon, 10(5), e27060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichaka, F., & Christian, N. (2013). The impact of governance on economic growth: Further evidence for Africa. The Journal of Developing Areas, 47(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao-Osorio, B., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2004). From R&D to innovation and economic growth in the EU. Growth and Change, 35(4), 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L., Prieger, J., & Gu, J. (2013). The impact of research and development on economic growth and productivity in the US states. In (Working Paper No. 48). Pepperdine University, School of Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, R. M., & Blinder, A. S. (1985). Macroeconomics, income distribution, and poverty. (NBER Working Paper No. 1567). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., Jones, C. I., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2017). Are ideas getting harder to find? (NBER Working Paper No. 23782). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Boeing, P. (2021). Estimating treatment effects with one-sided noncompliance: Evidence on mis-appropriation of R&D subsidies. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 14852). Institute of Labor Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux, C. J. (2017). Institutional quality and innovation: Some cross-country evidence. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 6(4), 472–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, C. (2015). R&D expenditures and economic growth relationship in Turkey. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5(1), 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, V., Ferrara, G., & Resce, G. (2023). Local government spending efficiency and fiscal decentralization: Evidence from Italian municipalities. Applied Economics, 55(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, policies, and growth. American Economic Review, 90(4), 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegati, E., Grandi, S., & Napier, G. (2005). Business incubation and venture capital: An international survey on synergies and challenges (Joint IPI/IKED Working Paper). Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2089917 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Capolupo, R. (2009). The new growth theories and their empirics after twenty years. Economics, 3(1), 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celikel, E. F. (2007). The link between innovation performance and governance: Country-level evidence. JRC/European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Center for International Development. (2015). Development and international foreign aid: Governance information bulletin 2015:2. Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. C. (2023). The impact of quality of institutions on firm performance. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 186, 122241. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y., Zhou, X., & Li, Y. (2023). The effect of digital transformation on real economy enterprises’ total factor productivity. International Review of Economics & Finance 85, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomen, M. (2022). Institutions-economic growth nexus in sub-saharan Africa. Heliyon, 8(12), e12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Bruneel, J., & Mahajan, A. (2014). Creating value in ecosystems: Crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Research Policy, 43(7), 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, D. T., Helpman, E., & Hoffmaister, A. W. (1997). North–South R&D spillovers. Economic Journal, 107(440), 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, D. T., Helpman, E., & Hoffmaister, A. W. (2009). International R&D spillovers and institutions. European Economic Review, 53(7), 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, F., & Pianta, M. (2008). Diversity in innovation and productivity in Europe. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18(3–4), 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M. D., Jha, C. K., Kırşanlı, F., & Sedai, A. K. (2023). Corruption and FDI in natural resources: The role of economic downturn and crises. Economic Modelling, 119, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanović, S., Mitrović, U., & Jurakić, M. (2019). Institutions as the driver of economic growth in classical, neoclassical, and endogenous theory. Economic Themes, 57(1), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çeştepe, H., Çetin, M., Avcı, P., & Bahtiyar, B. (2024). The link between technological innovation and financial development: Evidence from selected OECD countries. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 29(2), 1219–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danta, S., & Rath, S. (2024). Do institutional quality and human capital matter for innovation in Asian economies? Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 189, 122349. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R. C. (2020). Interplays among R&D spending, patent and income growth: New empirical evidence from the panel of countries and groups. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R. C., & Mukherjee, S. (2020). Do Spending on R&D Influence Income? An Enquiry on the World’s Leading Economies and Groups. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(4), 1295–1315. [Google Scholar]

- De, P. (2006). Trade, infrastructure and transaction costs: The imperatives for Asian economic cooperation. Journal of Economic Integration, 21(4), 708–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, H. L. F., Linders, G. J., Rietveld, P., & Subramanian, U. (2004). The institutional determinants of bilateral trade patterns. Kyklos, 57(1), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degong, M., Ullah, R., Ullah, F., & Mehmood, S. (2021). Financial liberalization, economic growth, and capital flight: The case of Pakistan economy. In M. Shahbaz, A. Soliman, & S. Ullah (Eds.), Economic growth and financial development: Effects of capital flight in emerging economies (pp. 115–134). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, J., & Siermann, C. (1996). Political instability, freedom and economic growth: Some further evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44(2), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J., de los Santos, J. A., & Ramírez, J. (2023). The impact of innovation on economic growth, foreign direct investment, and self-employment: A global perspective. Economies, 11(7), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devassia, B. P., Karma, E., & Muço, K. (2024). Role of human capital as a driver for sustainable development (SDG) in Western Balkan countries. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review, 4(2), 02051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971). Optimal taxation and public production. I. Production efficiency. American Economic Review, 61(1), 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Diebolt, C., & Perrin, F. (2016). Growth theories. In Handbook of cliometrics (pp. 177–195). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokas, I., Panagiotidis, M., Papadamou, S., & Spyromitros, E. (2023). Does innovation affect the impact of corruption on economic growth? International evidence. Economic Analysis and Policy, 77, 1030–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donges, A., Meier, J., & Silva, R. (2023). The impact of institutions on innovation. Management Science, 69(11), 6421–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2001). Trade in capital goods. European Economic Review, 45(7), 1195–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaki, K. E., & Ahmed, E. M. (2024). Digital technology adoption and globalization innovation implications on Asian pacific green sustainable economic growth. Journal of Open Innovation, Technology, Market, & Complexity, 10(1), 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadic, M., Garda, P., & Pisu, M. (2019). The effect of public sector efficiency on firm-level productivity growth: The Italian case (Volume No. 1573). (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1573). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhimi, M. A., & Miremadi, I. (2022). The impact of technological and social capabilities on innovation performance: A technological-catch-up perspective. Technology in Society, 68, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, F., Mnif, A., & Popiashvili, A. (2021). Impact of governance on economic growth in developing countries: A case of HIDC vs. LIDC. Journal of Social and Economic Development, 23, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2013). The impact of governance on economic growth in Africa. Journal of Developing Areas, 47(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, A., & Bartha, Z. (2025). Research and development as a driver of innovation and economic growth: Case of developing economies. In Journal of Social and Economic Development. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Fieldhouse, A. J., & Mertens, K. (2023). The returns to government R&D: Evidence from U.S. appropriations shocks (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper WP-2305). Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

- Gani, A. (2011). Governance and growth in developing countries. Journal of Economic Issues, 45(1), 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S., & Liu, X. (2022). The role of knowledge creation, absorption and acquisition in determining national competitive advantage. Technovation 112, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, T. (2011). The “China problem” Reconsidered: Property rights and economic development in Northeast Asia (Working paper). University of Chicago. Available online: https://home.uchicago.edu/tginsburg/pdf/workingpapers/TheChinaProblemRevisited.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Giordano, R., Lanau, S., Tommasino, P., & Topalova, P. (2020). Does public sector inefficiency constrain firm productivity? Evidence from Italian provinces. International Tax and Public Finance, 27(4), 1019–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocer, I. (2013). Effects of R&D expenditures on high technology exports, balance of foreign trade and economic growth. Maliye Dergisi, 165, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Gompers, P. A., Kovner, A., Lerner, J., & Scharfstein, D. S. (2005). Venture capital investment cycles: The impact of public markets (NBER Working Paper No. 11385). Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w11385 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gonzalez Parrao, C., Lwamba, E., Khan, L., Nabi, A., Lierl, M., Berretta, M., Hammaker, J., Lane, C., Quant, K., Eyers, J., & Glandon, D. (2022). Strengthening good governance in low- and middle-income countries: An evidence gap map. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). [Google Scholar]

- Goñi, E., & Maloney, W. F. (2017). Why don’t poor countries do R&D? Varying rates of factor returns across the development process. European Economic Review, 94, 126–147. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, R., Redding, S., & Van Reenen, J. V. (2004). Mapping the two faces of R&D: Productivity growth in a panel of OECD industries. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(4), 883–895. [Google Scholar]

- Griliches, Z. (1998). R&D and productivity: The econometric evidence. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griliches, Z., & Mairesse, J. (1984). Productivity and R&D at the firm level. In Z. Griliches (Ed.), R&D, patents, and productivity (pp. 339–374). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grindle, M. (2004). Good enough governance: Poverty reduction and reform in developing countries. Development Policy Review, 22(4), 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellec, D., & Van Pottelsberghe, B. (2001). R&D and productivity growth: Panel data analysis of 16 OECD countries. OECD Economic Studies, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X., Khan, H. A., & Zhuang, J. (2014). Do governance indicators explain development performance? A cross-country analysis. (Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, No. 417). Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N. T., & Yarram, S. R. (2024). The transition from middle-income trap: Role of innovation and economic globalisation. Applied Economics, 56(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. G. Z. (2015). Innovation and economic growth in East Asia. Japan Center for Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. G. Z., & Jaffe, A. B. (2003). Patent citations and international knowledge flow: The cases of Korea and Taiwan. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21(6), 849–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. (2010). Political institutions and financial development: An empirical study. World Development, 38(12), 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2015). Entrepreneurship, innovation and regional growth: A network theory. Small Business Economics, 45, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-Y., Lee, C., & Yang, H.-D. (2021). Efficiency of public R&D management agency and innovation performance: A cross-country empirical analysis. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 171, 120907. [Google Scholar]

- Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82(2), 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jalilian, H., Kirkpatrick, C., & Parker, D. (2007). The impact of regulation on economic growth in developing countries: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 35(1), 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B. S. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäntti, M. (1994). A More Efficient Estimate of the Effects of Macroeconomic Activity on the Distribution of Income. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(2), 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaira, C., & Omoke, P. C. (2020). Institutions, governance and economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 23(1), a1647. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H., Khan, S., & Zuojun, F. (2022). Institutional quality and financial development: Evidence from developing and emerging economies. Global Business Review, 23(4), 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., John, K., & Lemma, T. (2023). Country-level institutional quality and financial system efficiency. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2145793. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. S. (2022). Estimating a panel MSK dataset for comparative analyses of national absorptive capacity systems, economic growth, and development in low and middle income countries. PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0274402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. U., & López-Bazo, E. (2020). Technology diffusion, absorptive capacity, and income convergence: A spatial panel approach for Asian developing countries. Empirical Economics, 59, 1415–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. (1997). Imitation to innovation: The dynamics of Korea’s technological learning. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. (2024). Assessing the economic impact of innovative cities. Policy Studies, 46(4), 603–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1995). Institutions and economic performance: Cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures. Economics and Politics, 7(3), 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneller, R., Bleaney, M. F., & Gemmell, N. (1999). Fiscal policy and growth: Evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 74(2), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y., Pan, D., Liu, Z., Nuo, Z., & Li, D. (2022). The effect of government intervention on self innovation of strategic emerging enterprises based on the role of financial intermediary. Frontiers in Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(11), 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. K., Hoor, A., Jain, S. K., Singh, R., Kumar, K., Kumar, P., & Chamaria, A. (2024). Role of technological innovation and its governance in entrepreneurial evolution. International Journal of Electronic Government Research (IJEGR), 20(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. S. (2009). Balanced development in globalizing regional development? Unpacking the new regional policy of South Korea. Regional Studies, 43(3), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. (1999). The government as venture capitalist: The long-run impact of the SBIR program. Journal of Business, 72(3), 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Wan, J., Xu, Z., & Lin, T. (2021). Impacts of green innovation, institutional constraints and their interactions on high-quality economic development across China. Sustainability, 13(9), 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E., An, Z., Zhang, C., Li, H., & Fan, M. (2022). Impact of economic growth target constraints on enterprise technological innovation: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0272003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.-Å. (1992). National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Maskus, K. E., & Penubarti, M. (1995). How trade-related are intellectual property rights? Journal of International Economics, 39(3–4), 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, S., Gorg, H., & Kurekova, L. (2019). Skills-displacing technological change and its impact on jobs, tasks and skills: Evidence from the European Skills and Jobs Survey. In (IZA discussion paper 12541). IZA. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, W., Mohd-Rashid, R., Khalid, A., Aman-Ullah, A., & Abbas, Y. A. (2022). Empirical analysis of country-level institutional quality and public debt: Perspective of South Asian countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan & Sri Lanka) 2002–2018. Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development, 43(1), 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Méon, P.-G., & Sekkat, K. (2004). Does the quality of institutions limit the MENA’s integration in the world economy? The World Economy, 27(9), 1475–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, T. (2023). Middle-income trap and the evolving role of institutions along the development path. In J. Ricz, & T. Gerőcs (Eds.), The political economy of emerging markets and alternative development paths (pp. 37–60). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J. (1993). Human capital, technology, and the wage structure: What do time series show? In J. Mincer (Ed.), Studies in human capital: Collected essays of Jacob Mincer (Vol. 1, pp. 366–406). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mini, L., Moyo, C., & Phiri, A. (2024). Governance, institutional quality and economic complexity in selected African countries. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 19, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M., & Palubinskas, A. (2023). The influence of regulation on technological innovation and entry. Handbook of Innovation and Regulation. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Minviel, J.-J., & Ben Bouheni, F. (2022). The impact of research and development (R&D) on economic growth: New evidence from kernel-based regularized least squares. The Journal of Risk Finance, 23(5), 583–604. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A., & Virtanen, P. (2016). Governance theories and models. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business. [Google Scholar]

- Ndulu, B. J., & O’Connell, S. A. (1999). Governance and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(3), 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R. R., & Phelps, E. S. (1966). Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 56(1/2), 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C., Su, T., & Nguyen, T. (2018). Institutional quality and economic growth: The case of emerging economies. Theoretical Economics Letters, 8, 1943–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]