Abstract

This study assesses the comparative adequacy the suitability of two types of territorial units—administrative provinces and Local Labor Markets (LLMs)—for socioeconomic analysis and public policy formulation in Chile. Using two labor market indicators (employment and unemployment) and two educational indicators, statistical tests and connectivity matrices are applied to examine the internal and external coherence of these units and determine their spatial autocorrelation. The results show considerable spatial autocorrelation in both types of units, with patterns slightly more pronounced in the LLMs. Furthermore, there is evidence of independence between provinces and LLMs, supporting external coherence and better targeting of policies to specific local characteristics. In conclusion, socioeconomic characteristics show uniform clustering trends throughout the Chilean territory, regardless of the regional scale employed.

1. Introduction

Territorial analysis is essential for the effective formulation of public policies and for rigorous socioeconomic analysis (Abler et al., 1972; Gregory et al., 2011). The efficacy of any intervention—whether in urban planning, fund distribution, or unemployment mitigation—depends directly on whether the spatial units used genuinely capture the economic, social, and environmental dynamics of the communities they represent.

Historically, analyses have relied on political-administrative units (such as municipalities, provinces, or regions). While convenient for governance, this approach often ignores the reality of functional flows, especially labor mobility. This disconnection lies at the core of the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP), which suggests that the choice of territorial boundaries can significantly bias statistical results and the interpretation of spatial phenomena (Openshaw, 1984; Wong, 2004). The academic consensus, which will be detailed in the following section, emphasizes the need to use functional regions, such as Local Labor Markets (LLMs), which are defined by the intensity of internal interactions, primarily commuting flows of the labor force.

In the specific Chilean context, regional policies and socioeconomic inequality analyses continue to rely primarily on administrative provincial divisions. This practice is questionable, as Chile’s extensive geography and the marked disparities between urban centers and peripheral areas suggest that administrative borders are inconsistent with actual labor market boundaries. Despite existing efforts to delineate functional LLMs in the country (Casado-Díaz et al., 2017), a significant gap remains in the Chilean empirical literature: there is a lack of rigorous validation that contrasts the internal and external coherence of these functional units against their administrative counterparts, using key socioeconomic indicators and spatial econometric tools.

Therefore, the central research question guiding this study is: Do Local Labor Markets (LLMs) in Chile exhibit greater internal spatial coherence and lower external interdependence in socioeconomic indicators compared to provincial units, thereby justifying their superior use in public policy design?

To address this question, the present study focuses on comparing Chilean provinces with LLMs defined based on commune divisions, using labor market (employment, unemployment) and educational indicators. Through the application of spatial autocorrelation tools such as Moran’s I and LISA, we examine the spatial homogeneity and heterogeneity of both unit types.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: after introducing the theoretical foundations of functional regions and the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP), we describe the data sources and methodological framework. Subsequently, we present the empirical results of the comparative coherence analysis, followed by a discussion of their implications. The paper concludes with the main findings and final reflections.

2. Literature Review

The efficacy of socioeconomic analysis and the design of public policies have historically been linked to the appropriate selection of territorial units (Abler et al., 1972; Gregory et al., 2011). The literature in economic geography and spatial econometrics agrees that territory is a fundamental explanatory factor, not merely a container of phenomena, but a functional space that shapes social and economic interaction. This consensus has led to a systematic critique of the exclusive use of political-administrative units (such as provinces or regions) in regional analysis, as their boundaries are often arbitrary and do not reflect the true dynamics of flow and dependence.

2.1. Conceptual Foundation and Typology of Regions: Functionality vs. Administration

The delimitation of territorial regions constitutes a crucial and highly researched domain in the spatial sciences. A region is defined as a delimited spatial system, an expression of organizational unity that distinguishes it from others (Abler et al., 1972; Gregory et al., 2011; Klapka & Halás, 2016; Vrišer, 1978). The spatial sciences distinguish between two main types of socioeconomic regions: formal regions (internally homogeneous, defined by the generalization of variables) and functional regions (FRs) (internally heterogeneous) (Abler et al., 1972; Claval, 1998; Bassett & Haggett, 1971; Klapka et al., 2013).

Functional regions are characterized by a high frequency of intra-regional interaction (Karlsson & Olsson, 2006; Vanhove, 2018). Their structure is based on horizontal relationships in space, which manifest as spatial flows or interactions between their basic units (Ullman, 1972). These flows can include population mobility (such as daily commutes to work or school), trade, communications, and financial flows (Vanhove, 2018). The most prevalent functional region concept in the literature is that of local and regional labor systems (Cattan, 2002). Local Labor Markets (LLMs) or Travel-to-Work Areas (TTWAs) represent a fundamental application of functional regions. These are defined geographic areas where working life is concentrated, encompassing job searching, wage collection, and access to social security (Casado et al., 2010; Cattan, 2002). The flow of daily commuters is the most frequent and stable form of population movement, making it the most suitable database for delimiting regional areas for planning and administrative purposes (Beyhan, 2019; Casado-Díaz & Coombes, 2011; Smart, 1974). In contrast, administrative (or regulatory) regions, such as provinces, are often considered insufficient. Their rigid borders are often artificially demarcated (Openshaw, 1984) and may persist for reasons unrelated to current community interaction dynamics (Wirth, 1937). From a regional planning perspective, the delimitation of regions based on functional links is crucial for establishing the geographic unit necessary for effective administration (Beyhan, 2019).

2.2. The Importance of Functional Regions in Socioeconomic and Political Analysis

There is a strong academic consensus that functional regions (FRs) are the most appropriate framework for socioeconomic analysis and the implementation of public policies. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) consistently promotes the use of functional approaches, such as the Functional Urban Areas (FUA) framework, as the standard for international analysis and the formulation of effective urban policies (OECD, 2013, 2016, 2018, 2020). The OECD has consistently argued that administrative boundaries are insufficient to capture real urban dynamics. Functional Regions (FRs) are applied in multiple fields, including:

- -

- Analysis of the labor market and socioeconomic aspects (Karlsson & Olsson, 2006; Patuelli, 2007).

- -

- Delineation of administrative, planning, and statistical regions (Andersen, 2002; Cörvers et al., 2009; Van der Laan & Schalke, 2001).

- -

- Monitoring of economic development and support for housing and transportation policies.

This study follows in the tradition of comparative research between functional and administrative territories (Barkley et al., 1995; Cörvers et al., 2009; Manzanares et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2007). One example of a limitation in this field is the potential bias that arises from focusing on differences between geographically distant areas, which can distort the understanding of labor dynamics, given that workers prefer to work close to their homes (Cörvers et al., 2009). The results for the Chilean case suggest that the functional regionalization of Local Labor Markets (LLMs) could offer a more suitable framework than provinces, thanks to their greater internal coherence and the observed spatial heterogeneity, which is useful for the application of differentiated policies.

2.3. Methodological Challenges and Spatial Econometrics

The evaluation of functional territorial units presents inherent methodological challenges that require specialized tools, primarily due to the spatial nature of the data. Comparative territorial studies frequently must deal with the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) (Fotheringham & Wong, 1991; Openshaw, 1984). The MAUP arises because geographic units often have artificially demarcated boundaries. This problem is divided into two sub-problems: the “scale effect” (incoherence of results when changing the resolution or aggregation of units) and the “zoning effect” (incoherence when changing the boundaries of the zoning system, while maintaining the number of units) (Fotheringham & Wong, 1991; Openshaw & Taylor, 1979; Wong, 2004). One methodological response to MAUP is to report the range of possible results obtained when using multiple datasets or scales (Fotheringham, 1989; Wong, 2004).

Another critical challenge is the bias resulting from spatial autocorrelation, a phenomenon where observed values at one location depend on the values of neighboring observations. This spatial dependence is a crucial aspect of the data used by regional scientists (Anselin, 1988) and, if not addressed, can invalidate standard econometric techniques (Anselin, 1988; LeSage & Pace, 2009). Spatial dependence can be driven by spatial spillover effects (such as technological diffusion or traffic congestion) or by the omission of relevant explanatory variables with spatial structure (LeSage & Pace, 2009). Spatial econometrics is dedicated to building a comprehensive approach to incorporating these spatial effects into econometric models (Anselin, 1988). A key model is the Spatial Autoregressive (SAR) model, which includes a spatial lag of the dependent variable. The presence of this spatial lag has important implications: the traditional interpretation of the coefficients as partial derivatives no longer holds, since a change in an explanatory variable in one region can generate direct, indirect (or spillover), and total effects that reach all other regions through a multiplier matrix (LeSage & Pace, 2009).

To address spatial autocorrelation, the study employs statistical methods and spatial tests such as Moran’s Index (to measure global autocorrelation) (Getis & Ord, 1992) and LISA (Local Indicators of Spatial Association) analysis (to detect local clustering) (Anselin, 1995). A fundamental component of these analyses is the use of spatial weight matrices. These matrices are square and non-stochastic, and their elements reflect the intensity of interdependence between pairs of regions (Moreno & Vayá, 2000). Instead of using traditional physical contiguity (Larraz & Montero, 2003), this study innovates by proposing the use of functional and administrative connectivity matrices (Manzanares & Riquelme, 2017). These matrices define neighboring areas based on belonging to the same province or the same territorial unit. Furthermore, to assess external (inter-regional) coherence, a “complementary adjacency” matrix is used to identify differences in the spatial behavior of a commune with respect to other communes that do not belong to the same territorial unit.

The properties of the connectivity matrices used in the analysis are summarized in Table 1, where the differences in neighborhood structure between provincial and LLM partitions are observed.

Table 1.

Matrix properties.

3. Methodology and Sources of Information

The core of this research is a comparative analysis of two distinct spatial partitions covering the Chilean territory: the provinces (the legally defined second-level administrative units) and the Local Labor Markets (LLMs) (functional units defined based on the optimization of self-containment criteria derived from daily commuting flows between communes). The study employs four key socioeconomic indicators to assess the spatial coherence of both partitions: Employment, Unemployment, Uneducated Population (percentage of the population with incomplete basic education), and Population under Study (population aged 15–24 attending an educational institution). Data for these variables were compiled from official sources, primarily the National Institute of Statistics (INE) and the National Socioeconomic Characterization Survey (CASEN), aggregated to the municipal level for the year.

The analysis of spatial coherence is grounded in the statistical framework of spatial econometrics, utilizing GeoDa software (Anselin, 2003) to test for spatial autocorrelation and identify clustering patterns, which is critical given the inherent challenges of the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) (Openshaw, 1984; Wong, 2004). The coherence of the territorial partitions is tested using the Global Moran’s I Index to assess overall spatial autocorrelation, and the Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) (Anselin, 1995) to decompose this global average and identify specific local clusters (High-High, Low-Low, etc.).

A fundamental part of these analyses involves the use of spatial weight matrices, which describe how geographical elements (such as neighborhoods, cities, etc.) are related to each other. These relationships are determined by proximity or by the shared nature of characteristics. Different types of matrices can be used (Bivand et al., 2008):

- Binary Contiguity: This matrix simply indicates whether two observations are adjacent (with a weight of 1) or not (with a weight of 0).

- Distance-based Contiguity: Assigns weights that reflect the distance between observations, with closer observations receiving a higher weight.

- Kernel: Uses a kernel function to give greater weight to closer observations and less weight to more distant observations.

- Distance matrix: Displays the distances between all observations in the dataset.

- Connectivity matrix: Like a contiguity matrix, but can incorporate specific connections such as road routes, public transport routes, among others.

- k-NN neighborhood matrix: Defines neighborhoods based on the k nearest neighbors, prioritizing these nearest neighbors with a higher weight.

The choice between using provincial matrices or matrices adjusted to Local Labor Markets should be the result of a careful and thoughtful analysis, considering a variety of essential factors. Such an assessment leading to an informed choice will improve the accuracy of spatial autocorrelation analysis, particularly in the field of employment policy, namely (Lloyd, 2010):

- -

- Territorial Coherence (Spatial Homogeneity): It is essential that the different communes within the same territory exhibit symmetries in their socioeconomic dynamics and employment patterns, reflecting a unity in their practices and conditions.

- -

- Regional Uniformity (Spatial Heterogeneity): Ensuring that within the same established geographical area, there are no marked discrepancies in the socioeconomic profile or labor market of its communes, thus guaranteeing cohesion in regional characteristics.

- -

- Sizing of Actions: It is crucial to define whether employment policy strategies are to be implemented at a local level or whether they will have a broader scope, as this will determine whether larger or smaller scale matrices are more appropriate.

- -

- Purpose and Framework for Action: The guiding purpose of the initiative should be considered, whether it is aimed at addressing specifically local issues or whether it seeks to cover a wider territorial spectrum, thus adapting the matrix to the relevant vision and context.

For this comparative study, a first-order Queen contiguity matrix is employed. This choice is methodologically robust as the central aim is to evaluate the integrity of the borders of the two partitions (LLMs vs. provinces). Contiguity is the most direct representation of a shared frontier that could facilitate spatial spillover, making it the most rigorous test for verifying whether the functional units successfully minimize interaction with their neighbors. The resulting matrix is row-standardized to ensure that the weights sum to unity for each unit, which guarantees that the spatial effects are averaged and allows for the standardized interpretation of the coefficients of spatial autocorrelation.

Casado-Díaz et al. (2017) provide the functional regionalization based on LLMs, which is the one adopted in this study for a contextual interpretation of the information (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chilean LLMs by Color-Coded Identification. Source: Own elaboration based on Casado-Díaz et al. (2017).

The data for this study comes from the 2017 Census of the National Institute of Statistics of Chile (2017). Two key labor market indicators—the percentage of employment and the percentage of unemployment—were analyzed, as well as two key educational indicators—the percentage of the population without studies and the population studying—all relative to relevant populations. This approach allows us to address the influence of key variables on the country’s labor and education dynamics.

To identify the existence or not of correlation between the values of the key indicators, the Moran’s Index statistic is applied:

where is the spatial weights matrix,1 N is the sample size and is the mean or expected value of the variable. Instead of physical contiguity (Larraz & Montero, 2003), the use of functional and administrative connectivity matrices is proposed as a way of considering the reciprocal influences between communes without the need for them to be physical neighbors.

This new way of approaching spatial analysis was pointed out by Barkley et al. (1995) and Manzanares and Riquelme (2017) as a way of considering belonging to the same province or to the same Local Labor Market (LLM) as elements that define a neighborhood.

In addition, Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) are used to further examine the behavior of the proposed key indicator values. These association indicators use Moran’s statistic, but not globally, but by subgroups, to determine the degree of concentration of the key indicator values. The estimate of the local Moran’s I is:

where is the matrix of geographical weights and is the mean or expected value of the variable. This indicator measures the spatial association between the key indicator values assumed by a commune and the values assumed by its neighbors, defined through the functional or administrative connectivity matrix. Thus: (a) a commune belonging to an LLM or province with above-average values in its key indicator that is surrounded by other communes with values also above average, will form a “High–High” type cluster; (b) a commune with a below average value, surrounded by communes with below average values, will form a “Low–Low” cluster; (c) a commune with a value above the average, surrounded by communes with values below the average will form a “High–Low” cluster; and (d) a commune with values below the average and communes above will form a “Low–High” cluster. Furthermore, it will be determined whether the clusters are significant at different p-level values. The null hypothesis states the absence of a spatial pattern. In other words, confirming the null hypothesis shows that the key indicator values are randomly distributed. Conversely, rejecting the null hypothesis means the existence of a spatial behavior p. The null hypothesis states the absence of a spatial pattern. That is, confirming the null hypothesis shows that the values of the key indicator are randomly distributed. Conversely, rejecting the null hypothesis means the existence of a spatial behavior. The hypothesis is tested by placing the Moran coefficient within a normal fitted probability curve. For a better understanding of the methodologies and results obtained in this study, a review of the literature concerning spatial autocorrelation and regional analysis is recommended (Anselin, 1995; Getis & Ord, 1992).

The comparative adequacy of LLMs versus Provinces is ultimately evaluated across two key dimensions of coherence, using multiple statistical indices: Internal Coherence (Homogeneity) and External Coherence (Independence). Internal Coherence is assessed by the magnitude of the Global Moran’s I and a dedicated Spatial Similarity Index (also known as the Homogeneity Index). This index quantifies the degree of socioeconomic resemblance between the basic units (provinces) within the larger territorial partition (LLMs):

A complementary Spatial Heterogeneity Similarity Index is used to evaluate the coherence of variation across the units, comparing how well each partition captures regional uniformity against marked discrepancies in the socioeconomic profile (Lloyd, 2010). This assessment is further complemented by the visual evidence from the LISA cluster maps. External Coherence (Independence), which examines the degree of spatial dependence between adjacent units, is measured using a statistical test based on complementarity adjacency matrices:

This test, a key methodological component, assesses whether there are significant spatial spillovers across the borders of the defined units, comparing the degree of independence for both the Provincial and LLM partitions.

The analysis of geographic data through spatial weight matrices is a fundamental tool for understanding spatial dynamics and interactions, resulting in crucial information for strategic decision-making that incorporates the geographic component. GeoDa software is one of the platforms that facilitate this kind of analysis through the manipulation of spatial weight matrices (Anselin, 2005).

By using the proposed matrices, the data is being divided into separate provincial structures or Local Labor Markets (LLMs), where patterns of spatial autocorrelation could be observed within each province or LLM, which could lead to differentiated interpretations according to the specific characteristics of each province or LLM. However, the idea is to analyze everything together at the national level, to obtain an overview covering all provinces or LLMs. This would allow identifying patterns of spatial autocorrelation at a broader level, considering the totality of the observations and how they relate to each other throughout Chile. It is essential to keep in mind that the subdivision by communes may influence the perception of autocorrelation, showing significant differences in spatial patterns within each province, even when analyzing the full Chilean dataset.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the spatial autocorrelation and coherence tests, focusing exclusively on the descriptive comparison between the Provincial and Local Labor Market (LLM) partitions.

4.1. Global Spatial Autocorrelation (Internal Coherence)

The results for the Global Moran’s I statistic for all four socioeconomic indicators (Employment, Unemployment, Uneducated Population, and Population under Study) are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intraregional Coherence: Moran Indices and Similarity Indices.

For every indicator analyzed, the Moran’s I statistic for both the Provincial and LLM partitions is positive and statistically significant at the 99% confidence level (p < 0.01). This result universally confirms the presence of strong positive spatial autocorrelation across the Chilean territory, indicating that the null hypothesis of spatial randomness is rejected for all variables and unit types. Specifically, this means that communes within the same unit (LLM or Province) tend to share similar socioeconomic values. A comparative assessment of Moran’s I values shows that the LLM partition exhibits a higher magnitude of spatial autocorrelation compared to the Provincial partition across all four indicators. This quantitative difference suggests that the LLM delineation captures a slightly greater degree of internal coherence or homogeneity, thereby better aligning the functional units with the spatial patterns of the socioeconomic dynamics under study. This finding provides preliminary evidence supporting the functional delineation of LLMs over administrative provinces based on the concept of internal coherence (Smart, 1974; Van der Laan & Schalke, 2001).

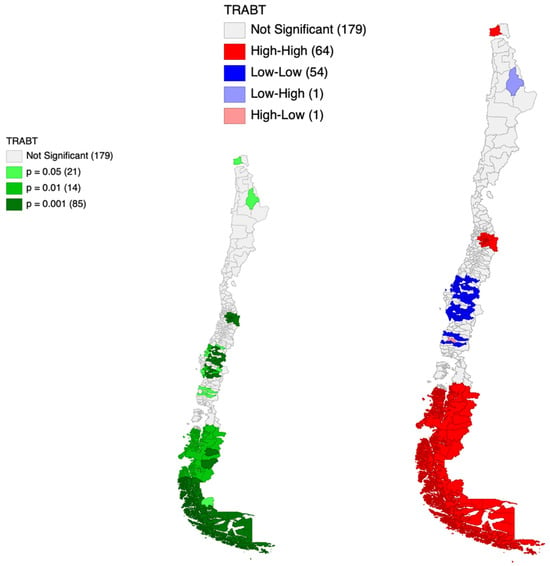

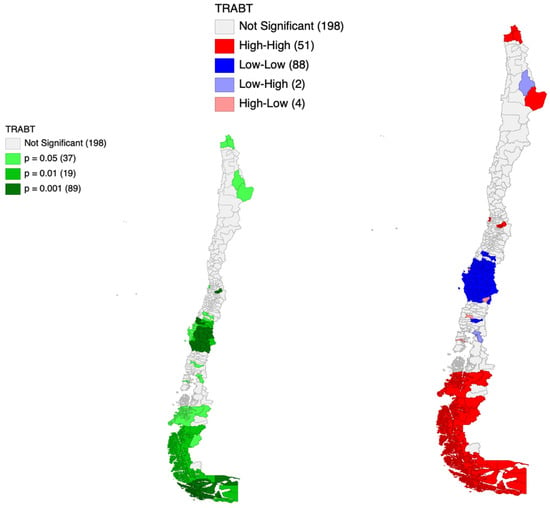

4.2. Local Spatial Autocorrelation (LISA) and Clustering

The Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis was conducted to identify specific spatial clustering patterns at a local level. The cluster maps generated by the LISA statistic for the employed population indicator and both partitions are visually represented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The results of this analysis allow for a granular assessment of the spatial concentration of the socioeconomic indicators.

Figure 2.

Employed population cluster. LLMs’ connectivity matrix. Source: Compilation based on data from the 2017 Census (INE).

Figure 3.

Employed population cluster. Provincial connectivity matrix Source: Own elaboration based on data from the 2017 Census (INE).

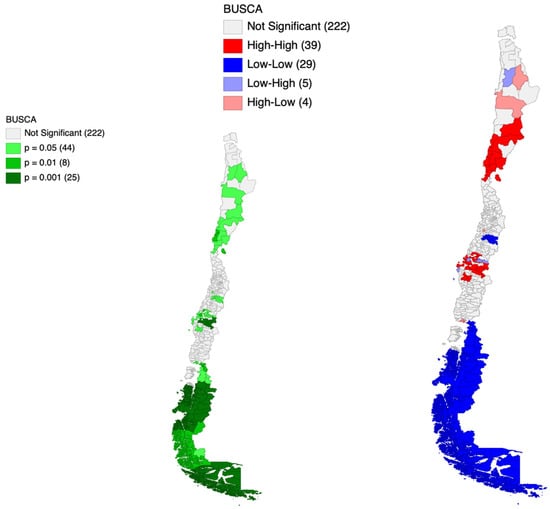

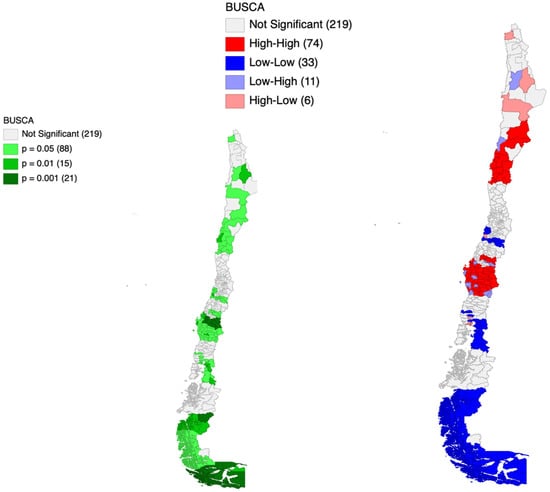

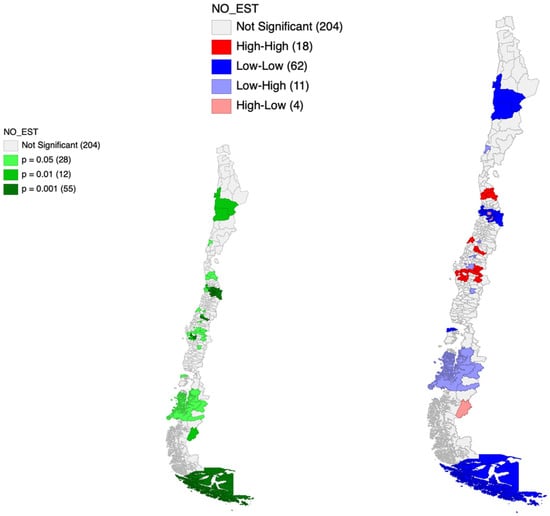

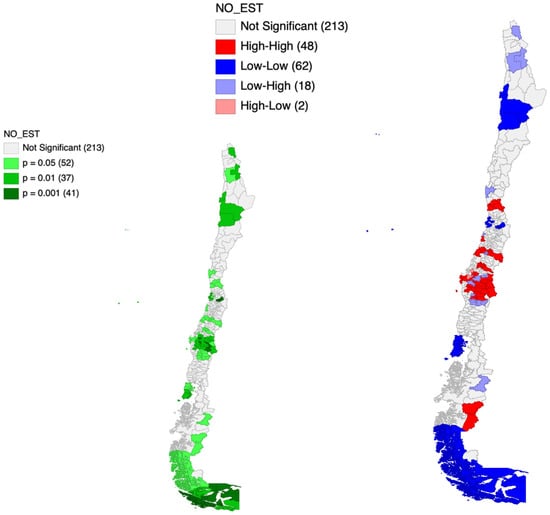

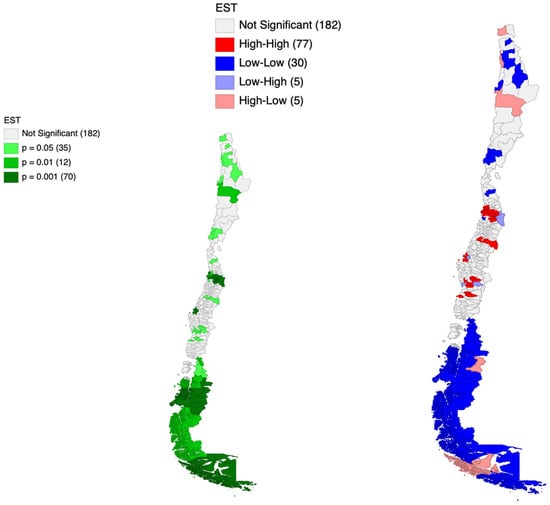

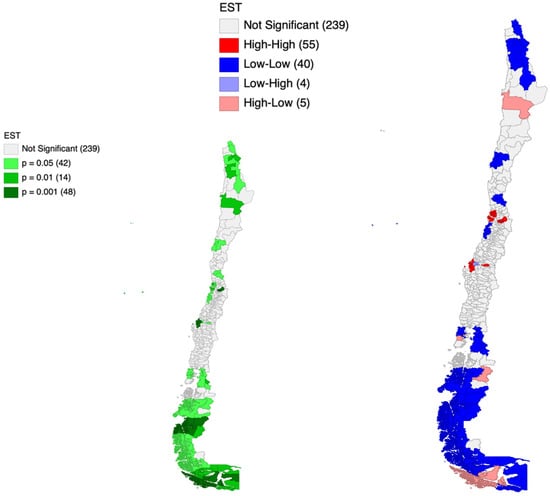

The Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis was finalized by incorporating the full set of key socioeconomic indicators to thoroughly assess spatial clustering patterns. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5 and Figure A6 in Appendix A, which illustrate the geographical distribution of the clusters for the indicators, directly contrasting the LLM connectivity matrix with the Provincial connectivity matrix.

The LISA maps reveal two fundamental findings regarding spatial clustering: first, remarkably uniform High–High (H-H) and Low–Low (L-L) patterns are maintained regardless of whether the Provincial or the LLM spatial unit is employed. Second, there is a consistent geographic polarization of socioeconomic development. The most prominent H-H clusters (high values surrounded by high values, indicating areas of economic and social concentration) are consistently located in the central metropolitan areas of the country, particularly within the Metropolitan Region of Santiago and its immediate surrounding regions. These H-H clusters suggest strong internal coherence of high values at both scales. Conversely, L-L clusters (low values surrounded by low values, indicating areas with low socioeconomic indicators) are systematically observed in the southern and remote northern regions of Chile. The overall geographic distribution of the clusters suggests that the fundamental socioeconomic clustering trend within the Chilean territory is highly robust and largely dictated by underlying geographic and demographic factors, rather than being an exclusive artifact of the administrative boundaries. Importantly, the LLM partition generally shows a more compact and less diffuse spatial definition of these clusters, especially in the metropolitan areas.

4.3. External Coherence Analysis

To evaluate the external coherence (or independence) between neighboring units, the results of the complementary adjacency matrix test are presented in Table 3. The complementary adjacency matrix defines neighboring communes as those located outside the specific LLM or Province to which the commune belongs.

Table 3.

Interregional Coherence: Moran Indices and Similarity Indices.

The test results indicate that the relationship between neighboring units (for both LLMs and Provinces) is characterized by spatial independence for most of the indicators. Specifically, the Global Moran’s I statistic for the complementary adjacency matrix approaches zero and the test fails to reject the null hypothesis of independence in most cases, providing robust statistical evidence that the boundaries drawn—both administrative and functional—are effective in limiting strong inter-unit spillovers. This finding aligns with the criteria for effective functional regionalization, suggesting that internal processes are dominant over external interaction once the unit has been defined, even in the case of the administrative provinces. The resulting near-zero values confirm that external areas do not significantly influence the socioeconomic characteristics of the internal area, validating the external coherence of both partitions.

4.4. Synthesis of Spatial Coherence Results

The analysis of spatial autocorrelation shows distinct regional clustering patterns in the variables studied, both for regions defined by Local Labor Markets (LLMs) and those delimited by provinces. A moderate degree of positive autocorrelation has been identified for all four indicators. This result suggests that the two forms of regionalization—provinces and LLMs—are indeed reflecting spatial autocorrelation, with Moran’s Indices reflecting a tendency towards geographical clustering for all observed variables. The patterns of spatial autocorrelation are quantitatively more pronounced at the level of LLMs compared to provinces, mainly regarding the percentage of the population employed and the percentage of the population studying, indicating that LLMs achieve a stronger internal spatial coherence for these two key indicators. Despite this, the degree of these differences is not substantial, with clustering more evident for the employment rate and to a slightly lesser degree for the rates of job seekers and those in education.

When examining intra-regional similarity using indices of spatial homogeneity and heterogeneity, a high internal coherence is found. This means that there is a significant concentration of communes that share similar values in both provinces and LLMs. That is, there are communes that show similar socioeconomic characteristics grouped geographically, revealing relatively low spatial heterogeneity—little concentration of communes with opposite characteristics.

In particular, the provinces show slightly greater spatial homogeneity in the indicators of percentage of population seeking employment and percentage of population not in education. In contrast, the LLMs show greater uniformity in terms of the percentage of the population currently studying. When it comes to spatial heterogeneity, the values are comparable between LLMs and provinces, with no systematic advantage observed for either partition, suggesting that the variation and disparity within the variables analyzed are similar in both types of regionalization. This indicates that socioeconomic differences within the areas studied are limited or evenly distributed across the geographical space. In conclusion, the evidence points to a coherence in the distribution patterns of the variables across the different regions analyzed, with similar levels of homogeneity and heterogeneity in both LLMs and provinces. This suggests that, regardless of the regional scale employed, socio-economic characteristics tend to be clustered and uniform across geographical space.

To measure inter-regional coherence (External Coherence or independence) between the different LLMs and provinces, an innovative approach was proposed: using a complementary adjacency matrix for both regionalizations. The exploration revealed the absence of global spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I near zero), with very low Moran’s Indices consistently observed for both provinces and LLMs. This result is positive for the analysis, as it indicates a desirable statistical isolation between the geographical units, which favors external coherence by suggesting there are no predictable patterns between communes in different areas.

The study of cluster concentration, carried out through LISA techniques, reinforces these findings, showing low values and thus low spatial homogeneity. This implies that communes rarely share similar characteristics with their neighbors that do not belong to the same province or LLM, and those few that do are dispersed and not representative of a provincial or LLM pattern. For example, the indicators for the percentage of the population seeking employment and the percentage of the population studying in the provinces exhibit somewhat higher values than in the LLMs, which may suggest a more pronounced geographical variation in these aspects when measured against external neighbors. On the other hand, spatial heterogeneity, which reflects how diverse an area is compared to other geographical units, showed higher values. This is particularly noticeable in the provinces for the employed population indicator, and in the LLMs for the job-seeking population. These numbers indicate that there are significant differences between communes in different provinces or LLMs in terms of these indicators, which is a point in favor of the implementation of public policies that can address the specific characteristics of groups of communes. Collectively, this evidence confirms that external coherence is strengthened when communes manifest relevant differences compared to those that do not belong to the same province or LLM, which is consistently observed in both partitions presented here.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Territorial Coherence

The comparative analysis between provinces (administrative regions) and Local Labor Markets (functional regions) in Chile underscores the existence of a strong spatial dependence of socioeconomic characteristics. The results of the Global Moran’s Index test confirm the presence of spatial autocorrelation for the connectivity matrices, indicating patterns of geographic clustering for all the variables analyzed. This finding is consistent with the field of spatial econometrics, which focuses on spatial dependence, a critical aspect of the data used by regional scientists (Anselin, 1988).

In terms of internal (intra-regional) coherence, both types of territorial units (LLMs and provinces) demonstrated a significant clustering of communes with similar socioeconomic characteristics. Specifically, the LLMs exhibited greater uniformity in the rates of the population under study, which aligns with the academic consensus that functional regions, defined by stable daily mobility flows, better reflect spatial systems of interaction than political divisions (Smart, 1974; Vanhove, 2018). However, Chilean provinces showed slightly greater homogeneity for job-seeking rates and the uneducated population.

The analysis of inter-regional (external) coherence, innovatively conducted using complementary adjacency matrices, revealed that communes in Chile operate largely independently of those that do not belong to the same territorial unit (LLM or province). The low Moran’s Index values observed in these complementary matrices and the low inter-regional spatial homogeneity (evidenced by the low cluster concentration values at the LISA level) are crucial. This finding validates the capacity of Chilean functional and administrative boundaries to demarcate communities that are markedly different from their external neighbors, which is a fundamental requirement for any regionalization to be effective in planning (Beyhan, 2019).

5.2. Implications for Chilean Public Policy

The study concludes that functional regionalization, exemplified by Local Labor Markets (LLMs), could offer a more suitable framework for socioeconomic analysis and the implementation of public policies in Chile. This recommendation is based on evidence of the greater internal coherence of LLMs, combined with the high spatial heterogeneity observed between units.

The need to prioritize LLMs over provinces is justified by the demands of a modern regional policy. The OECD (2013, 2016, 2018, 2020) systematically promotes functional frameworks, such as Functional Urban Areas (FUAs), because administrative boundaries are insufficient to capture real-world dynamics. From a policy design perspective, low inter-regional spatial homogeneity is desirable, as it reinforces the idea that policies should be targeted at areas with distinct socioeconomic characteristics. Likewise, the presence of high spatial heterogeneity (diversity) within regions, observed considerably in the LLMs for the job-seeking population, is useful because it reflects internal variations that deserve differentiated attention and not a “one-size-fits-all” approach. The capacity of the LLMs to reflect these significant variations between communes that justify differentiated attention is a point in favor of implementing employment strategies that seek an optimal spatial match between labor supply and demand (Casado et al., 2010).

The nature of spatial dependence, where observations at one location depend on the values of neighboring observations (Anselin, 1988), means that any change in an explanatory variable in one region (e.g., an investment or employment policy) can generate spillover effects that impact all other regions (LeSage & Pace, 2009). The use of spatial econometric models allows for the quantification of these direct and indirect effects, which is fundamental for evaluating the implications of local and national government policies (LeSage & Pace, 2009). Therefore, the use of LLMs as units for flow analysis and econometric modeling (Manzanares & Riquelme, 2017) is crucial for strategic decision-making that incorporates the geographic component.

5.3. Methodological Challenges

Despite the robustness of the exploratory results, it is imperative to recognize the inherent limitations of territorial analysis, the most prominent being the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) (Openshaw, 1984; Fotheringham & Wong, 1991). The MAUP implies that the results obtained, whether due to the scale effect or the zoning effect, can be inconsistent because the boundaries of the geographic units are artificially demarcated. The variation in spatial autocorrelation patterns between different scales and units (provinces and LLMs) already observed in the study is a direct manifestation of this problem. The methodology employed in this study, by comparing results obtained with different partitioning systems (provinces vs. LLMs) and by using functional and administrative connectivity matrices, represents a practical approach to addressing MAUP, recognizing that reporting the range of possible results under multiple data systems is a suggested strategy (Wong, 2004; Fotheringham, 1989).

Future research would benefit from the application of spatial regression models, such as those incorporated in spatial econometrics (Anselin, 1988), including the Spatial Autoregressive (SAR) model, which is designed to capture simultaneous spatial dependence (LeSage & Pace, 2009). These models would allow going beyond exploratory analysis (Moran/LISA) to formally estimate the magnitude of spillover effects and confirm the validity of the proposed functional regionalization.

6. Conclusions

The main conclusion of this research is the empirical validation of functional regionalization, exemplified by Local Labor Markets (LLMs), as a more robust and appropriate territorial framework for socioeconomic analysis and public policy formulation in Chile. This central finding reinforces the academic consensus that advocates for the use of units based on interaction and connectivity.

The results of the study hold direct applied significance, especially for employment and regional development policies. The superiority of LLMs is manifested in their greater internal coherence across most indicators, reflecting that they are delimitations that more effectively capture spatial systems of interaction (Smart, 1974). This conclusion is strongly aligned with the position of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which has systematically promoted the use of functional frameworks, such as Functional Urban Areas (FUAs), arguing that administrative boundaries are insufficient to capture real-world dynamics. Furthermore, the evidence of high spatial heterogeneity within LLMs, particularly notable for the job-seeking population, is crucial for the design of public strategies, as this heterogeneity reflects internal variations that justify differentiated attention, moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Concurrently, the low inter-regional spatial homogeneity, confirmed by the low Moran’s Indices in the complementary adjacency matrices, strongly supports the implementation of policies targeted at specific groups of communes with distinct needs. In terms of spatial dynamics, the confirmation of global and local spatial autocorrelation implies that socioeconomic variables in Chile are not randomly distributed but rather depend on the values of their neighbors (Anselin, 1988). This observed spatial dependence underscores the critical reality that policy decisions in one region can generate indirect or spillover effects that impact neighboring regions. Therefore, local and national governments should move toward employing spatial econometric models that can quantify both the direct and indirect effects of investment or tax policies (LeSage & Pace, 2009).

Methodologically, this research contributes to the field of regional science through its innovative approach. A significant contribution is the introduction of a spatial exploratory model that uses the complementary adjacency matrix, an innovative tool for measuring external or inter-regional coherence and demonstrating that Chilean territorial units meet the fundamental requirement of effective regionalization by exhibiting relevant differences compared to communes outside their unit (Beyhan, 2019). Finally, while joining the tradition of territorial comparisons (e.g., Barkley et al., 1995; Cörvers et al., 2009), the study explicitly acknowledges the influence of the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) (Openshaw, 1984). The methodology, by comparing the results obtained from two partitioning systems (provinces and LLMs), successfully follows the recommended strategy for handling MAUP effects by reporting the range of possible outcomes (Fotheringham, 1989; Wong, 2004). Although the current results are based on exploratory analysis, a solid foundation is established for future work, where the next logical step is to move towards formal spatial regression modeling, such as SAR models, to formally estimate the magnitude of spillovers and confirm the suitability of LLMs as units for econometric modeling (Anselin, 1988; LeSage & Pace, 2009).

Funding

State Investigation Agency. PID2020-114896RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Cluster population seeking employment. LLM Connectivity Matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure A2.

Cluster population seeking employment. Provincial connectivity Matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure A3.

Uneducated population cluster. LLM connectivity matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure A4.

Uneducated population cluster. Provincial connectivity matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure A5.

Cluster population under study. LLM connectivity matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure A6.

Population cluster under study. Provincial connectivity matrix. Source: Own elaboration.

Note

| 1 | The spatial weights matrix, symbolized by W, is a square matrix of N × N (where N is the number of spatial units), non-stochastic, whose elements (wij) reflect the intensity of the interdependence between each pair of regions i,j (Moreno & Vayá, 2000). |

References

- Abler, R., Adams, J. S., & Gould, P. (1972). Spatial organization: The geographer’s view of the world. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A. K. (2002). Are commuting areas relevant for the delimitation of administrative regions in Denmark? Regional Studies, 36(8), 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. (1988). Spatial econometrics: Methods and models. Kluwer Academic Publishers Google Schola, 2, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. (1995). Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geographical Analysis, 27(2), 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. (2003). GeoDa 0.9 user’s guide. Spatial Analysis Laboratory (SAL), Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. (2005). Exploring spatial data with GeoDaTM: A workbook. Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science, 1963, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley, D., Henry, M., Bao, S., & Brooks, K. (1995). How functional are economic áreas? Test for intra-regional spatial association using spatial data analysis. Papers in Regional Science, 74, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, K., & Haggett, P. (1971). Towards short-term forecasting for cyclic behaviour in a regional system of cities. In Regional Forecasting (pp. 389–413). Butterworth. [Google Scholar]

- Beyhan, B. (2019). The delimitation of planning regions on the basis of functional regions: An algorithm and its implementation in Turkey. Moravian Geographical Reports, 27(1), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivand, R. S., Pebesma, E. J., & Gomez-Rubio, V. (2008). Applied spatial data analysis with R. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Casado, J. M., Martínez, L., & Flórez, F. (2010). Los mercados locales de trabajo españoles. Una aplicación del nuevo procedimiento británico. In J. M. Albertos, & J. M. Feria (Eds.), La ciudad metropolitana en España: Procesos urbanos en los inicios del siglo XXI (pp. 275–313). Thomson-Civitas. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Díaz, J. M., & Coombes, M. (2011). The delineation of 21st century local labour market areas: A critical review and a research agenda. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 57, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Díaz, J. M., Martínez-Bernabéu, L., & Rowe, F. (2017). An evolutionary approach to the delimitation of labour market areas: An empirical application for Chile. Spatial Economic Analysis, 12(4), 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, N. (2002). Redefining territories: The functional regions. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Claval, P. (1998). Politics and the university. In The urban university and its identity: Roots, location, roles (pp. 29–46). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cörvers, F., Hensen, M., & Bongaerts, D. (2009). Delimitation and coherence of functional and administrative regions. Regional Studies, 43(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A. S. (1989). Scale-independent spatial analysis. In M. F. Goodchild, & S. Gopal (Eds.), Accuracy of spatial databases (pp. 221–228). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A. S., & Wong, D. W. S. (1991). The modifiable areal unit problem in multivariate statistical analysis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 23(7), 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A., & Ord, J. K. (1992). The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geographical Analysis, 24(3), 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M., & Whatmore, S. (Eds.). (2011). The dictionary of human geography. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, C., & Olsson, M. (2006). The identification of functional regions: Theory, methods, and applications. The Annals of Regional Science, 40(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapka, P., & Halás, M. (2016). Conceptualising patterns of spatial flows: Five decades of advances in the definition and use of functional regions. Moravian Geographical Reports, 24(2), 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapka, P., Halás, M., Tonev, P., & Bednář, M. (2013). Functional regions of the Czech Republic: Comparison of simpler and more advanced methods of regional taxonomy. Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis–Geographica, 44(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Larraz, B., & Montero, J. M. (2003). Estructura espacial de la tasa de desempleo: Una aproximación. In Anales de Economía Aplicada. ASEPELT. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage, J. P., & Pace, R. K. (2009). Introduction to spatial econometrics. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C. (2010). Spatial data analysis: An introduction for GIS users. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manzanares, A., & Riquelme, P. J. (2017). Análisis espacial del desempleo en los mercados locales de trabajo Españoles. Revista Galega de Economía, 26(2), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares, A., Sánchez, C., & Riquelme, P. J. (2016). Análisis de la coherencia en los mercados locales de trabajo de la provincia de Huelva. Revista de Estudios Regionales, 107, 177–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W., Bill, A., & Watts, M. (2007). Identifying functional regions in Australia using hierarchical aggregation techniques. (Working Paper No. 07–06). Centre of Full Employment and Equity, The University of Newcastle, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, R., & Vayá, E. (2000). Técnicas econométricas para el tratamiento de datos espaciales: La econometría espacial. Edicions Universitat de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics of Chile. (2017). Census 2017. [Dataset]. Government of Chile. Available online: http://resultados.censo2017.cl/Home/Download (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- OECD. (2013). OECD regions at a glance 2013. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2016). OECD regions at a glance 2016. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2018). OECD regions and cities at a glance 2018. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). OECD regions and cities at a glance 2020. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw, S. (1984). The modifiable areal unit problema (Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography, 38). Geo Books. Available online: https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/sv/iss/SGO9010/openshaw1983.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Openshaw, S., & Taylor, P. J. (1979). A million or so correlation coefficients: Three experiments on the modifiable areal unit problem. In N. Wrigley (Ed.), Statistical applications in the spatial sciences (pp. 127–144). Pion. [Google Scholar]

- Patuelli, R. (2007). Regional labour markets in Germany: Statistical analysis of spatio-temporal disparities and network structures. Available online: https://www.tesionline.it/tesi/Regional-Labour-Markets-in-Germany:-Statistical-Analysis-of-Spatio-Temporal-Disparities-and-Network-Structures/21201 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Smart, M. W. (1974). Labour market areas: Uses and definition. Progress in Planning, 2(4), 239–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, E. (1972). Geography as spatial interaction. In M. E. Hurst (Ed.), Transportation geography (pp. 29–39). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Laan, L., & Schalke, R. (2001). Reality versus policy: The delineation and testing of local labour market and spatial policy areas. European Planning Studies, 9(2), 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, N. (2018). Regional policy: A European approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vrišer, I. (1978). Slovensko urbano omrežje in policentrični razvoj. Zbornik II. Slovensko-slovaškega geografskega simpozija. Maribor. Available online: https://giam.zrc-sazu.si/sites/default/files/gs_clanki/GS_0701_065-076.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Wirth, L. (1937). Localism, regionalism, and centralization. The American Journal of Sociology, 42(4), 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. W. (2004). The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP). In WorldMinds: Geographical perspectives on 100 problems: Commemorating the 100th anniversary of the association of American geographers 1904–2004 (pp. 571–575). Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).