3. Research

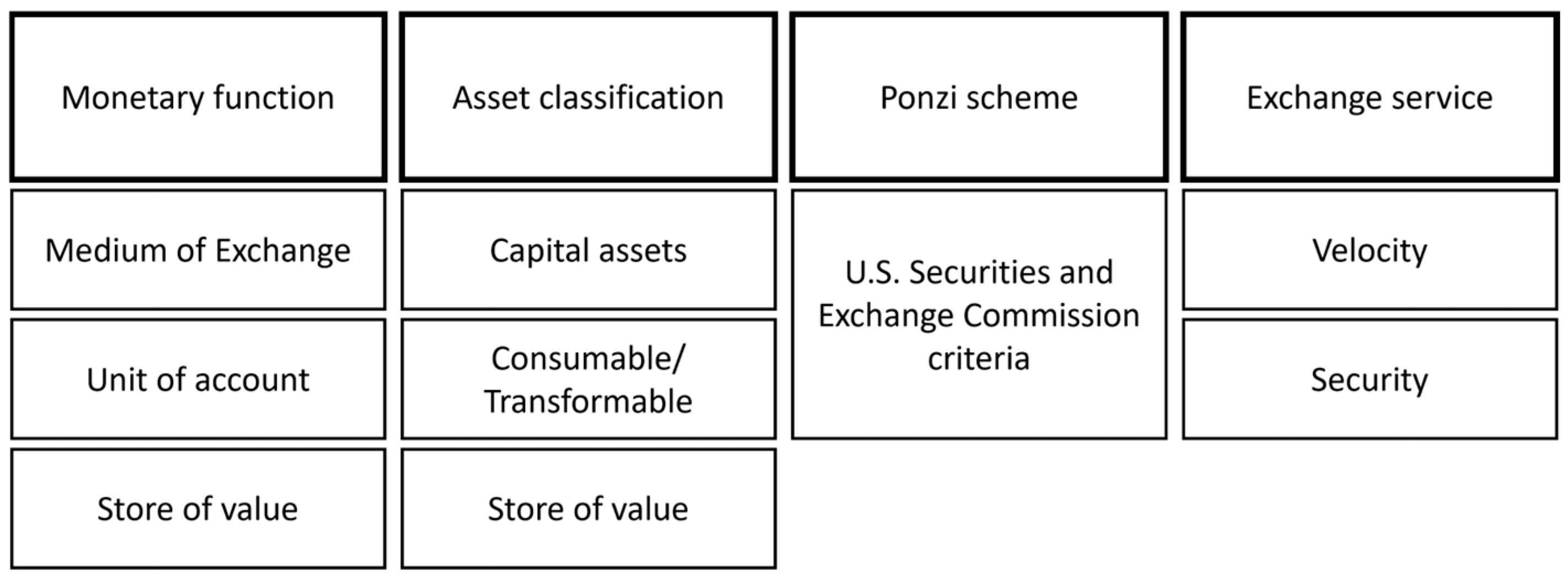

The definition of BTC, its uses, and its classification as an asset are fundamental elements in determining expectations for its future behavior and how institutions should treat it. To this end, this document progressively examines the elements that have formed part of the BTC concept, as shown in

Figure 1. It confirms that cryptocurrencies do not have legal tender status under Spanish law.

Firstly, it analyzes its behavior in relation to the characteristics of a currency, namely price stability, unit of measurement, and store of value. Secondly, it examines BTC’s behavior as an asset, analyzing the various asset types, including capital goods, tradable goods, and store-of-value assets. It compares BTC’s performance at the analytical level and then examines its correlation and statistical behavior relative to other assets.

Additionally, monetary assets and their classification under a Ponzi pyramid investment scheme (

Vasek & Moore, 2019) have been discussed in accordance with the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s definition (

US SEC, 2021;

US SEC, 2025), as applicable to BTC’s performance. Finally, the analysis of BTC as a means of payment has been deepened by its potential to provide an exchange service for the population. Indeed, the study has analyzed the matter across different BTC performance metrics, subsequently offering new solutions based on technological developments.

3.1. Approaching the Monetary Function of the BTC

As previously noted, the functions of a medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value must be addressed for monetary consideration. The present study uses historical series on the price of BTC and on currencies (the dollar, euro, and yen) for empirical comparison (price dynamics, volatility, and relative stability).

To understand BTC’s role as a means of payment, it is imperative to assess the volume of transactions carried out, whether for investment or exchange purposes. First, the evolution of BTC use since 19 September 2014 has been studied, as this is the reference date for the availability of data on Yahoo Finance regarding the BTC exchange rate relative to other cryptocurrencies, as shown in

Table 2. The analysis spans the period from September 2014 to March 2025, depending on the availability of data for each variable. Thus, unlike fiat currencies, BTC’s capped circulating supply limits its capacity to adjust to changes in economic conditions or shifts in demand. This behavior of BTC reflects, at least partially, its relationship with the dollar. Subsequently, the analysis compares BTC’s performance with that of major fiat currencies (the euro, the pound, and the yen) and with the dollar.

As noted earlier, this paper aims to address the central question of whether BTC should be classified as a currency or an asset, examining its purported monetary functions in relation to its market behavior between 2014 and 2025. Indeed, BTC is currently classified as a cryptocurrency. However, not an entirely legal tender because it does not reliably fulfill the classic functions of money: a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value (

Mishkin, 2019;

Mankiw, 2020). According to

Catalini and Gans (

2016), BTC represents a technological innovation in recording and transferring value through blockchain technology. However, its use as a currency is limited by its high volatility and limited acceptance. In this sense, the International Monetary Fund (

IMF, 2021) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS,

Auer & Claessens, 2018) define it as a ‘cryptoasset’: a digital asset based on cryptography that can serve as a medium of exchange but lacks sovereign backing and is not legal tender.

As a limited medium of exchange, while BTC can be used for transactions, its current commercial adoption is marginal and highly concentrated in digital niches (

Baur et al., 2018). As already mentioned, its high volatility limits its usefulness as a stable means of payment because transaction values can fluctuate significantly over short periods (

Yermack, 2015). Furthermore, transaction costs and validation times may affect their efficiency compared to traditional fiat or electronic systems (

Narayanan et al., 2016). On the other hand, transaction costs and validation time can affect its efficiency compared to conventional fiduciary or electronic systems (

Narayanan et al., 2016).

Concerning the inefficient unit of account, companies and corporations do not express their financial statements, balance sheets, or prices in BTC, but rather in fiat currencies (USD, EUR, etc.), which could reinforce the notion that BTC is a speculative asset rather than a monetary one (

Böhme et al., 2015). BTC is not used for pricing or accounting purposes. Consequently, its function as a unit of account could be limited to the crypto ecosystem. In that regard,

Böhme et al. (

2015) pointed out that BTC’s role as a unit of account is negligible, since it is not compromised by its nature with the denomination of goods and services.

In relation to the unstable store of value, as previously discussed, certain factors make BTC less likely to be considered a store of value (

Dyhrberg, 2016) due to its high volatility and lack of institutional support to bring it closer to the category of speculative asset, characterized by recurring price bubbles (

Cheah & Fry, 2015). Apparently, BTC behaves more like a speculative asset than a haven (

Baur & Hoang, 2021) or store of value (

Baur & Dimpfl, 2018). Therefore, BTC should be considered a ‘cryptoasset’, i.e., a crypto-based digital asset serving as a medium of exchange, but it is neither a legal tender nor a sovereign currency (

IMF, 2021). This definition underscores that its value relies on both algorithmic scarcity and decentralized trust, rather than on backing from a monetary authority. Thus, its economic function is closer to that of an alternative investment asset than to that of a currency (

Auer & Claessens, 2018;

Corbet et al., 2019).

3.2. Approaching the Asset Functions of the BTC

The research also explored how far BTC can be regarded as an asset. Indeed, as shown below, although

Greer (

1997) does not explicitly mention BTC, the concept and definition of investment portfolio assets do include it. The classification defines three super asset classes with specific features as indicated in

Table 3. In the case of capital assets, first, they share the generation of returns through dividends or interest, their reliability in forecasting their value, and their durability. Second, there are consumable or transformable assets, generally in the form of raw materials, which can be durable (e.g., minerals) or perishable (e.g., food). Certain assets, such as art and coins, store value because they do not directly generate returns, unlike capital goods, which are not consumed or transformed, unlike commodities. As BTC does not generate returns during periods of high volatility, has an indefinite expected life, and is not a consumer good, it meets the classification criteria for store-of-value assets, which are regarded as a ‘superclass’.

To contrast with the classification above, asset prices or benchmark indices for these classes have been obtained from BTC’s daily price data (see

Table 4) and are available as indicated in the

Supplementary Materials.

The analysis utilized the daily closing prices of each asset from 30 September 2014 to 10 September 2025. When a quotation was unavailable, primarily due to market closures on weekends or public holidays, the study used the previous trading day’s closing value. This procedure ensures temporal consistency across series and reliability in the computation of static and dynamic correlation measures.

3.3. Approaching the Related Ponzi Schema of BTC

A Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud in which existing investors receive income from new investors, who in turn receive income from the original investors. BTC differs in its definition. The idea of presenting the return on investment as income generation is entirely foreign to BTC, whose performance is driven solely by changes in its value. There is no direct payment of income. Consequently, the study examines the implications of the ‘red flag’, or even common characteristics, according to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (US SEC), specifically those related to high returns without risk, consistent growth, unregistered investments, unlicensed sellers, complex strategies, account statement errors, and uncertain payments.

3.4. Approaching the Threat of Service Obsolescence of BTC

Regarding payment methods, BTC speeds up international transactions and facilitates business development and service automation through technological innovation. It offers advantages such as instant international payments, low transaction fees, high security, and transparency. However, these inherent advantages have limitations: compared to a traditional asset with guaranteed value over time, BTC has demonstrated features that have enabled it to initiate and lead a technological revolution under the guise of a currency.

4. Findings

This section analyzed and plotted all the above data using the R software, specifically under the RStudio “Desert Sunflower” release, in addition to the R-related packages ‘ggplot2’, ‘dplyr’, ‘scales’, ‘lubridate’, ‘tseries’, ‘purrr’, ‘quantmod’, and corrplot. The code used in the analysis is available in

Appendix A. BTC’s relationship with each descriptive element is presented below, along with corresponding comparative tables. For data extraction and processing, the R packages “quantmod” and “tidyquant” were used to directly retrieve financial time series from the Yahoo Finance website (

https://finance.yahoo.com/, accessed on 13 October 2025). The comparison of asset classes has been carried out using selected tickers [c(“^GSPC”, “BOND”, “^FNAR”, “GD=F”, “^IRX”, “BTC-USD”)]. Additionally, macroeconomic indicators from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) database were downloaded appropriately from the FRED website (

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DTWEXBGS, accessed on 13 October 2025).

4.1. Approaching the Monetary Function of the BTC

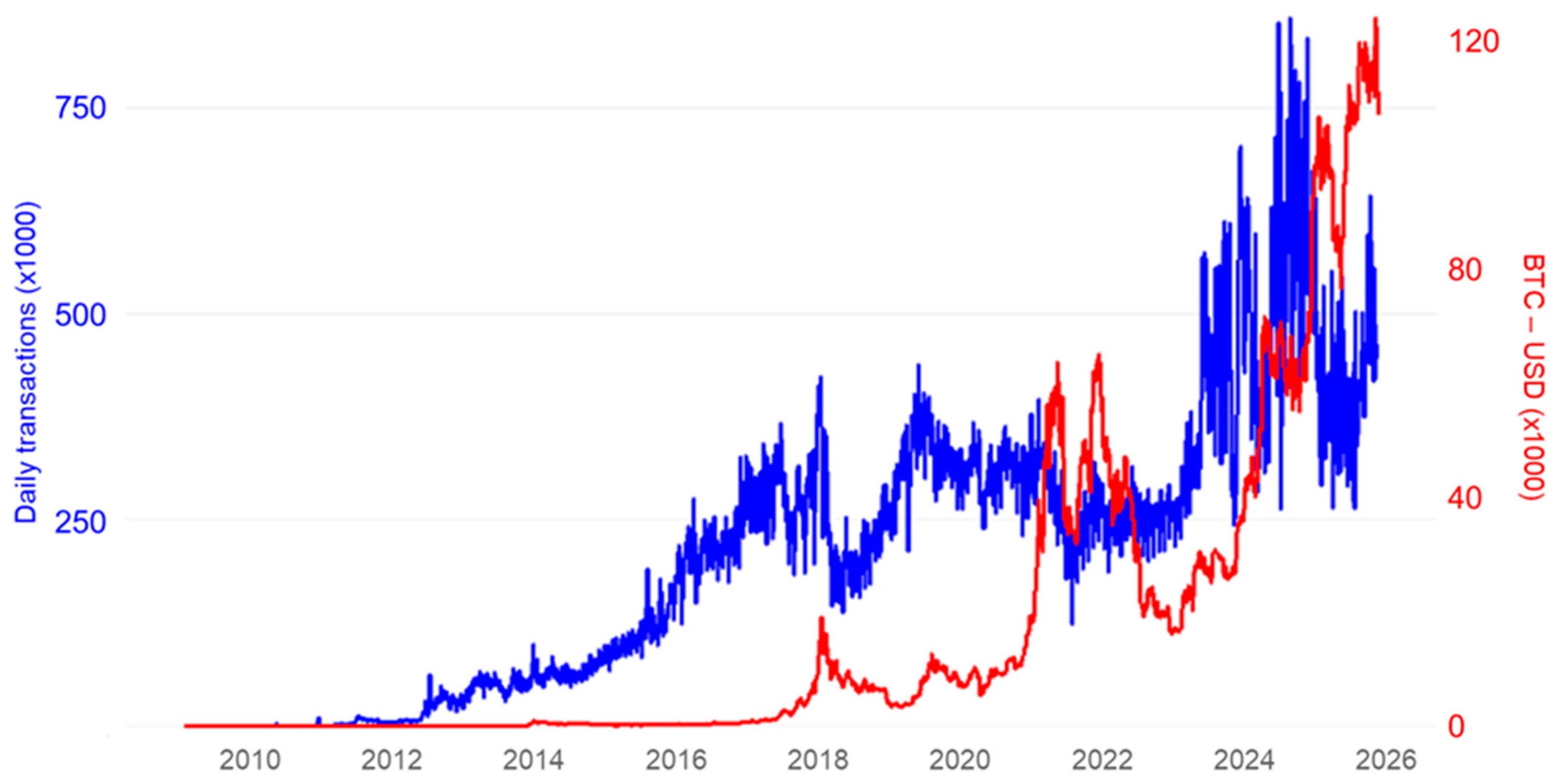

Regarding the monetary function, analyzing its use as a means of payment reveals that growth in its use has increased knowledge of BTC and its price.

Figure 2 shows that, from the end of 2015, BTC’s daily transaction volume exceeded 200,000. From that moment, daily transactions remained almost uninterrupted, ranging from a minimum of 200,000 to a maximum of 400,000, until April 2023. From that point onward, the transaction dynamics changed, and volumes increased within a highly variable range, reaching their peak in mid-2024, when for several consecutive daily transactions exceeded 800,000.

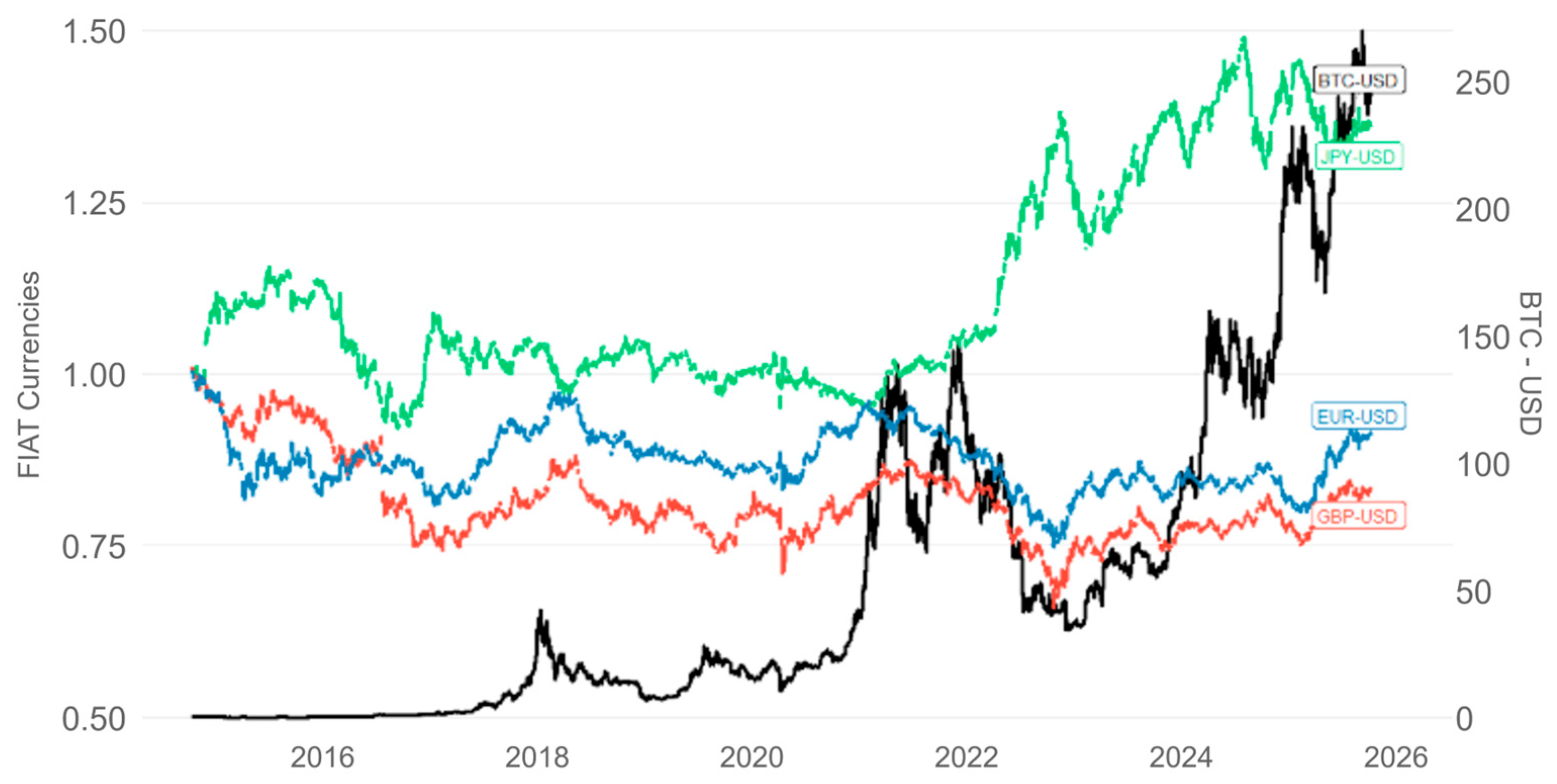

For the unit-of-measure function and given that the world’s major fiat currencies meet that criterion,

Figure 3 shows the ratios against the dollar for BTC, the Euro, the Pound, and the Yen. Fiat money showed similar behavior between 0.65 and 1.50 times the September 2014 value for about 11 years. In opposition to that behavior, the BTC has changed its relationship with the dollar, reaching an increase in its revaluation in September 2025 of more than 250 times the value of 19 September 2014, a situation characterized by significant fluctuations in its price, as exemplified by the peak reached on 8 November 2021, with a revaluation of 147 times the initial value of the study, before retreating a year later to 34.5 times the initial value, which represented a fall to 23.5% of the previously reached level. Underlying this currency appreciation is a deflationary process. In this process, on 8 November 2021, 0.00628 BTC would buy the same product that cost one BTC on 17 September 2014, relative to the dollar. Over the same period, any change in the fiat currencies used would not have resulted in a price change of more than 40%.

The results of this monetary analysis section show BTC’s high market price volatility and limited economic penetration as a medium of exchange. The following section examines BTC as an asset to examine its value-depositing aspect.

The process of retrieving and posting from Finance Yahoo with the R-related packages (“quantmod” and “tidyquant”) has been carried out by using selected tickers for currencies [c(“JPYUSD=X”, “EURUSD=X”, “GBPUSD=X”, “BTC-USD”)].

4.2. Approaching the Asset Functions of the BTC

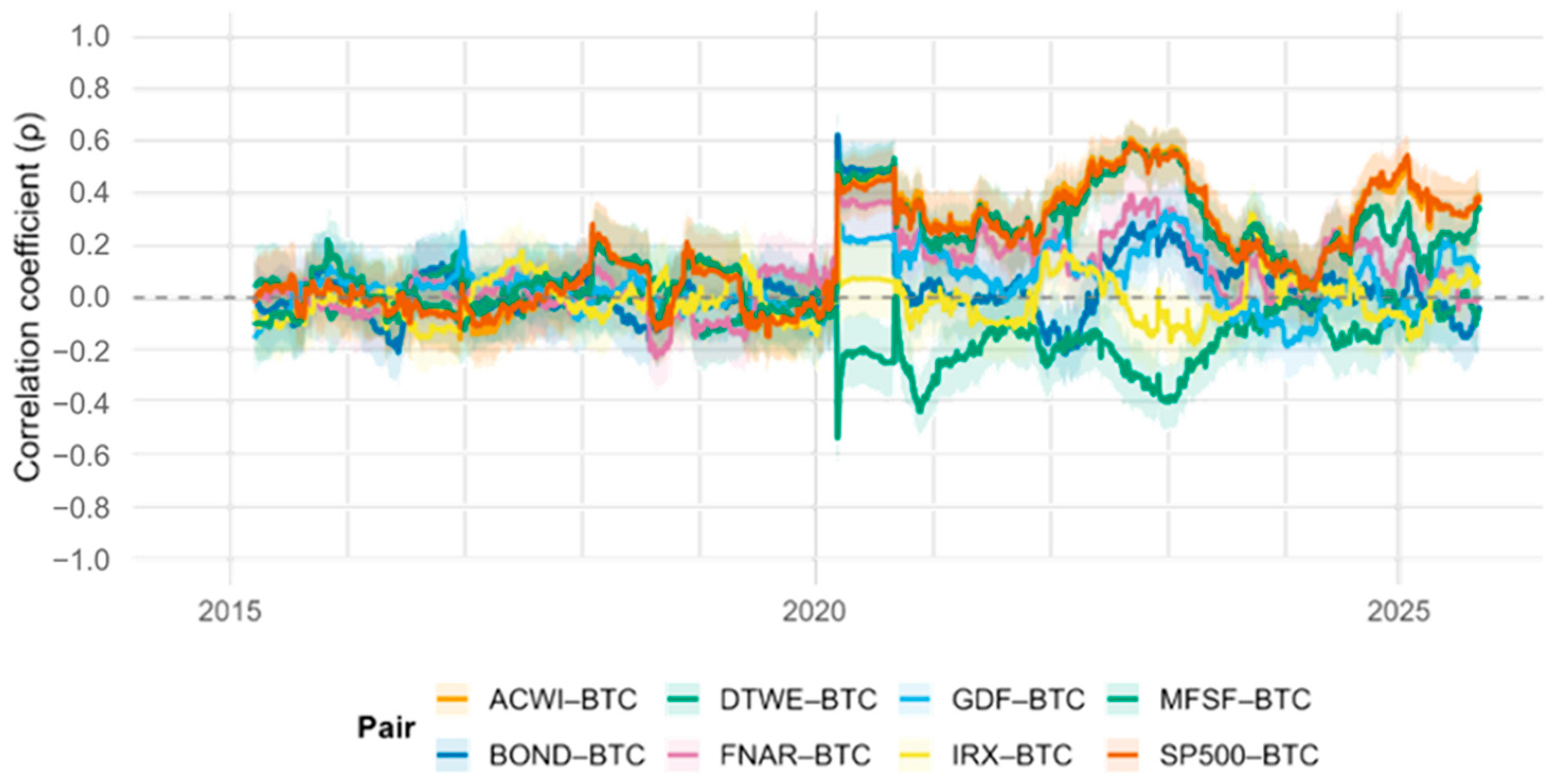

Given their role as assets and based on the identified super asset classes (capital assets, consumption/transformation assets, and value deposit assets), the logarithmic return series of these assets have been analyzed using rolling correlations with a 180-day moving window. To avoid spurious correlations, the stationarity of the series was verified using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP) tests. All series were found to be stationary at the 5% significance level, confirming the validity of the correlation analysis. The models assume conditionally Gaussian innovations under an AR(1)–GARCH(1,1) and DCC(1,1) specification, estimated by quasi-maximum likelihood with standard convergence criteria. An 180-day rolling window was adopted to balance responsiveness and smoothness in the correlation dynamics.

The rolling correlations shown in

Figure 4 indicate that BTC exhibits a time-varying dependence on different asset classes. Between 2020 and 2021, a marked increase in its correlation with equity indices, such as the S&P 500 and ACWI, brought BTC’s behavior closer to that of traditional risk assets. In 2023, these correlations decrease, and by 2024, they become more unstable. Furthermore, correlations with assets such as IRX, considered safe havens, are low or negative, suggesting that BTC does not exhibit stable hedging behavior.

Table 5 presents the mean value, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values of the conditional correlations across the three selected periods. Specifically, it analyzes the 2017 expansion phase, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the institutional adoption period from 2020 to 2021, and the market normalization phase from 2022 to 2024. In contrast to the high correlation with capital assets, the correlation with monetary indexes tends to zero. These share the main technical characteristics mentioned, as well as the term ‘cryptocurrency’. Although BTC has shown periods of higher correlation with equity indices such as the S&P 500, this relationship is neither stable nor linear. The empirical research suggests that BTC exhibits dynamic dependence, with correlations across time and market conditions, and displays unconventional behavior during episodes of financial stress.

As shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7, the study calculated the annual skewness and kurtosis coefficients for the daily logarithmic returns of each asset from 2014 to 2025 to better understand the research approach. With skewness, BTC exhibits a marked negative trend in its early years, characterized by sharp falls more frequently than rises, a typical characteristic of the capital asset superclass, such as stocks and bonds. The positive values observed after the 2020 shock, associated with the COVID-19 crisis, suggest a progressive symmetry in the return distribution, with behavior closer to that of store-of-value assets, especially from 2022 onwards, when it exhibits more moderate kurtosis, consistent with that observed in traditional safe-haven assets. The inception of BTC, from characteristics of capital goods to traits closer to value-preserving assets, suggests a maturation of the BTC market and a gradual reduction in its exposure to systemic risk factors. In statistical terms, the kurtosis coefficient is interpreted using conventional thresholds: a leptokurtic distribution is indicated by values greater than three, reflecting the presence of fat tails and, therefore, a higher probability of extreme events. Conversely, the three platykurtic values shown below appear to be associated with thinner tails and lower tail risk.

Table 7 shows that BTC exhibits leptokurtic behavior, similar to that of most assets. This pattern intensifies during periods of market turbulence, such as 2020 and 2022, both of which are consistent with heavy tails and volatility clustering.

4.3. Approaching the Related Ponzi Schema of BTC

By comparing BTC’s market risks with the structural characteristics of a Ponzi scheme, one can distinguish between a technical and a legal analysis. This study assumes that both may share certain behavioral risks that affect decision-making, such as speculation or herd behavior. This is paramount in clearly presenting the conceptual and structural differences between them.

4.3.1. Formal Market Risks of BTC

It concerns potential financial losses arising from changes in market variables such as prices, volatility, liquidity, or exchange rates, albeit not necessarily implying improper fraud, but rather reflecting the inherent uncertainty of an asset (according to the BIS, ESMA, BaFin, and IMF). Specifically, investor expectations, technological adoption, and global liquidity cycles influence BTC’s price, driving extreme volatility. This scenario also occurs when liquidity risk is observed, due to either a financial crisis or panic, characterized by a decline in trading volume and an increase in spreads, as well as by the difficulty of selling without incurring a substantial loss. Another reason is counterparty and custody risk, where BTC holders lose their funds due to hacking, custody errors, or exchange fraud, specifically those related to operational risk, although not structural in nature. Further reasons concern regulatory, political, or legal risk, such as when changes in national regulations or restrictions affect the price or usability. Finally, technological or technical risk can be another reason why network vulnerability resulting in the loss of private keys may affect holdings or value.

4.3.2. Associated Risks of BTC

This raises the question of whether there are risks associated with decentralized protocols compared to those tied to platforms or operators, and specifies which concerns relate to custodians and exchanges rather than BTC itself. Indeed, this is a key issue in the regulation and economic-financial analysis of the crypto ecosystem: distinguishing between risks inherent to the decentralized protocol, such as BTC, and operational or custody risks arising in centralized platforms or intermediaries, including exchanges, brokers, or custodians.

Regarding the risks associated with decentralized protocols and centralized platforms in the crypto ecosystem, they fall into two broad categories. At one end, the risks associated with decentralized protocols, including those closely related to architecture, governance, and security (e.g., BTC, ETH); at the other end, those relating to intermediation or custody risks derived from entities managing store or intermediate assets on behalf of users (e.g., Binance, FTX, Coinbase). Risks associated with decentralized protocols stem from the absence of direct human or business mediation, reflected in the level of code design and the degree of mediation.

In the case of BTC-related protocols, there are technological and governance risks, including potential software flaws, bugs, or cryptographic vulnerabilities that compromise the system’s integrity. Risks associated with the centralization of mining power can also compromise security through 51% attacks. Nevertheless, BTC has one of the most resilient structures due to its decentralization and the immutability of its consensus mechanism, primarily through ‘Proof of Work’ (

Narayanan et al., 2016). Furthermore, BTC’s consensus mechanism makes it one of the most secure decentralized systems ever developed, despite challenges posed by its governance rigidity (

Narayanan et al., 2016).

Concerning environmental and energy risks from BTC-related protocols, the ‘Proof of Work’ mechanism has been criticized nowadays because of high electricity consumption, raising concerns about its sustainability (

Stoll et al., 2019).

Connected to systemic regulatory risk, the BTC-related protocols themselves lack legal personality. Therefore, governments cannot be held directly responsible for misuse, such as money laundering or tax evasion, thus creating regulatory gray areas (

Auer & Claessens, 2018). While BTC-related protocols themselves are neutral, their pseudonymity indeed creates a regulatory blind spot (

Auer & Claessens, 2018).

Another issue is the risk associated with intermediaries, custodians, and exchanges. Most problems and user losses in the crypto world are not due to the BTC-related protocols themselves but rather to failures and fraud by intermediaries that handle user funds. These risks fall within the operational and custody domains and are the primary areas of concern for regulators, including the SEC, ESMA, and the FATF (

ESMA, 2023). These risks can be seen depending on the matter assessed. This prevents the fact that, in terms of custody risk, centralized custodians (e.g., exchanges that store private keys) can concentrate assets on wallets under their control, directly contradicting BTC’s decentralized philosophy. This means that users do not directly possess their keys, which implies a risk of loss or misappropriation, as occurred with Mt. Gox in 2014 and FTX in 2022 (

Arner et al., 2023).

Additionally, there is a risk of insolvency and fraud, since centralized exchanges can operate without accounting transparency or external audits, making them vulnerable to fraud, embezzlement, or bankruptcy (

Easley et al., 2019). BTC, as a protocol, did not collapse in the cases of FTX, Celsius, or BlockFi; it was the centralized operators who mismanaged the funds. Furthermore, there are cybersecurity risks because custodians and platforms are frequent targets of hacks (e.g.,

Tsuchiya & Hiramoto, 2021), resulting in losses of USD 530 million, as was the case with Mt. Gox, which suffered losses of USD 450 million. In fact, these attacks target custody infrastructure, not the BTC-related blockchain, whose network has not been compromised to date through cryptographic design or the consensus mechanism. Finally, regarding regulatory compliance risk, there are centralized platforms that must comply with policies based on the criteria “Know your Customer/Anti-Money Laundering” (KYC/AML) and investor protection regulations. That is, non-compliance results in penalties and affects overall trust in the ecosystem, though not in the underlying protocol (

IMF, 2021). In that regard,

Table 8 provides a concise legal taxonomy diagram to maintain clarity among the levels of analysis.

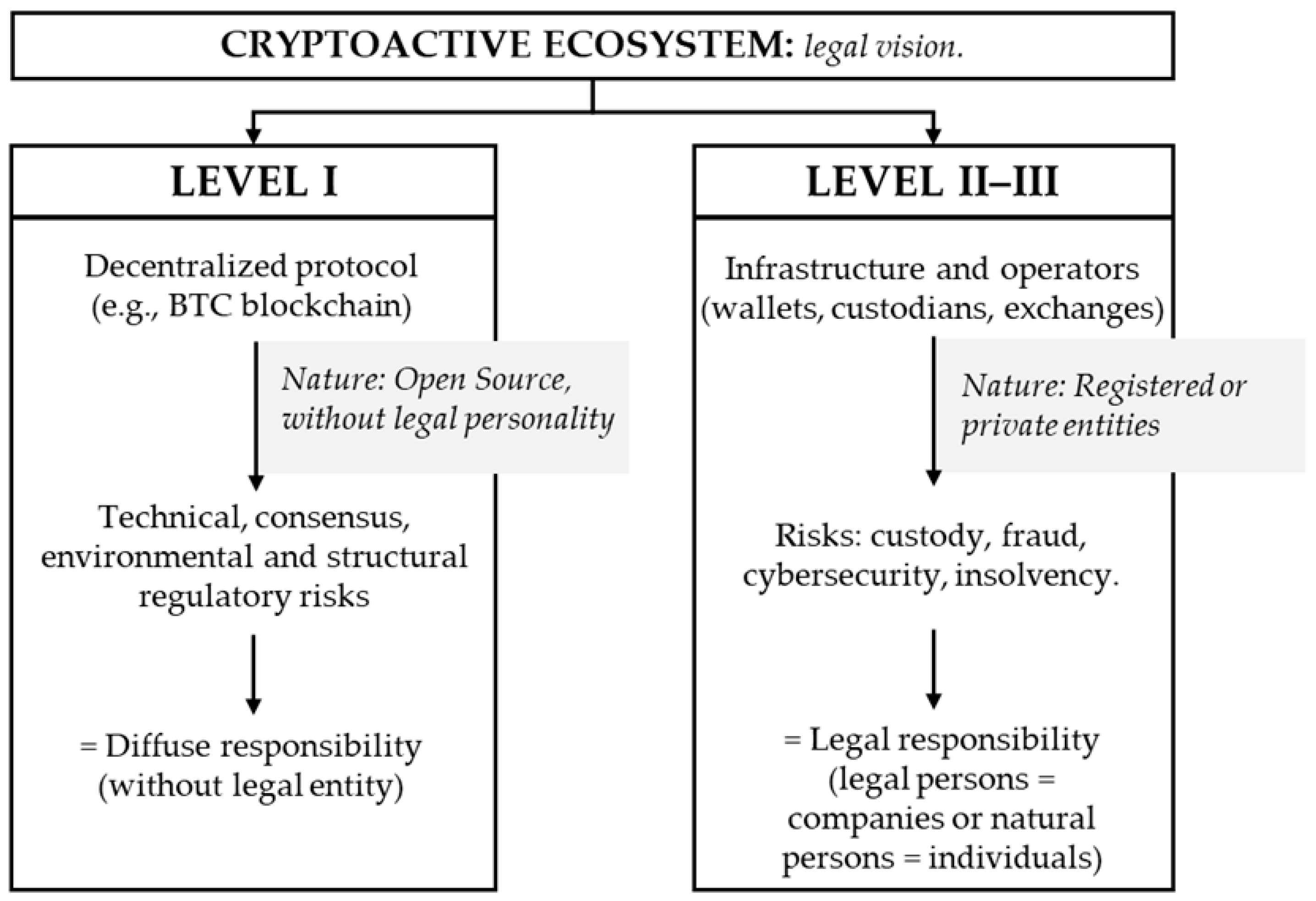

Simultaneously, according to the legal taxonomy shown in

Figure 5, the basis of related features can be regarded at three levels, which means they can differentiate into any cryptoasset. There are those to be encompassed within Level I, as an autonomous and decentralized protocol (i.e., a legal entity responsible for its code or operation is not applicable), on the one hand; and those of Levels II and III, as legal entities subject to regulation, supervision, and sanctions, on the other.

Accordingly, the levels mentioned above are subject to specific risks assigned due to exacting criteria. Level I, namely protocol (i.e., BTC), is related to technological risk, particularly those concerning vulnerabilities in the network or consensus (namely, Proof of Work), but also those relating to environmental risk, such as energy consumption (

Stoll et al., 2019), and even to governance risk, such as conflicts arising from forks. Nonetheless, BTC’s security and transparency have kept it free of critical failures since its inception in 2009 (

Narayanan et al., 2016). Similarly, in relation to level II, namely custodians and services, there are operational risks, such as key loss, hacks, and negligent management. Additionally, there are delegated custody risks, where users lack control over their funds. This is, for example, the case of Mt. Gox in 2014, which suffered a loss of 850,000 BTC due to mismanagement. Finally, regarding level III, namely exchanges and platforms, there is an insolvency (

Khan et al., 2025) or fraud risk, such as the misuse of customer deposits (e.g., the FTX case in 2022). Issues have also been observed in regulatory risk, such as non-compliance with KYC/AML regulations (

Easley et al., 2019), as well as in systemic reputational risk, which affects overall trust in crypto assets, though not the underlying protocol.

Regarding a comparative regulatory perspective, international organizations, such as the IMF, the BIS, and the EU (

European Commission, 2023), recognize this implicit taxonomy by differentiating among them. Consequently, native decentralized cryptoassets (e.g., BTC and ETH) are supported without an identifiable issuer, for two reasons. On the one hand, cryptoassets are issued by identified entities (e.g., tokens, stablecoins); on the other hand, cryptoassets are managed by service providers (CASPs), which require licensing, oversight, and auditing. Thus, regulation does not target the BTC protocol itself, but rather the intermediaries that operate it or facilitate access to it (

European Commission, 2023).

All the above provide clear evidence for assessing that the BTC, as a decentralized protocol, falls outside the traditional legal framework. The risks that threaten users (i.e., loss of funds, hacks, fraud) do not only originate from the code or network, but also from centralized intermediaries operating through custodians or platforms. It could also be assumed that the main regulatory challenges in the joint control of ‘cryptomarkets’ (e.g., BTC) include defining the legal responsibilities of the actors who mediate them.

4.3.3. Formal Risks of a Ponzi Scheme

Since the 1920s, Ponzi schemes have traditionally been a highly effective yet unlawful method of defrauding investors. Behind this, however, is the idea that they cause significant investment losses, in addition to the explicit promise of abnormally high guaranteed returns, even in the absence of an empirical financial basis. This is due to accounting opacity and a lack of auditing, since independent, external verification of transactions or alleged investments is not provided. Another reason relates to the absolute dependence on the entry of new investors, who expect to receive the promised returns (i.e., when new contributions cease, the system collapses). Additionally, centralization of control over funds derives from the common fact that one entity or person controls the flow and distribution of the alleged returns. Finally, there is a lack of underlying value or a secondary market, a direct consequence of which is that it is not based on free supply and demand but on pyramidal recruitment. These elements facilitate an objective comparison across four key dimensions: legal structure, source of performance, transparency and verifiability, and system sustainability.

Similarly, it could establish a structural distinction between BTC and a Ponzi scheme, as shown in

Table 9.

Based on the red flags of fraud outlined by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (

US SEC, 2021),

Table 10 assesses whether the typical warning signs of Ponzi schemes have been identified within the BTC framework, both operationally and structurally. Building on this,

Table 11 further examines these SEC-designated red flags specifically from an operational standpoint, highlighting their applicability to BTC´s decentralized architecture.

For all the above reasons, BTC cannot be classified as a Ponzi scheme, as it does not promise guaranteed returns, its operation is public, and its value depends on transparent market mechanisms. Although it exhibits high volatility, such risks are inherent in speculative assets rather than indicative of fraud. Moreover, independent of its market price fluctuations, BTC’s ability to provide payment-processing services further distances it from the conceptual framework of a Ponzi scheme. In this way, the common point is that the BTC market and Ponzi schemes can generate massive losses and are influenced by biases in decision-making, such as speculation, the bubble effect, and herd-like behavior. In that sense, a Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud in which existing investors receive income from new investors. BTC differs in its definition. The idea of presenting the return on investment as income generation is entirely foreign to BTC, whose performance is driven solely by changes in its value. There is no direct payment of income. Consequently, the study examines the implications of the ‘red flag’ or common characteristics identified by the US SEC, specifically those related to high returns without risk, consistent growth, unregistered investments, unlicensed sellers, complex strategies, account statement errors, and uncertain payments.

4.4. Approaching the Threat of Service Obsolescence of BTC

As already pointed out, BTC’s rapid expansion in the cryptocurrency markets has become a milestone in the field of decentralized currencies, serving as a paradigm for modern economies, as governments and financial institutions cannot regulate its operations, unlike fiat currencies. However, technological development has continued at a pace, and it is now possible to use other cryptocurrencies whose technology improves BTC’s performance as a means of payment. It is reasonable to assume that other cryptocurrencies may gradually replace BTC in this current role. Consequently, this scenario would lead to a conflict between possible developments that improve BTC’s performance (e.g., the Lightning Network) and those outside BTC’s sphere that offer solutions better suited to users’ needs.

In addition to the currencies above, stablecoins and other virtual currencies dependent on central banks are emerging in a so-called ‘cryptoenvironment’ with growing functionality. In the event of obsolescence, the question remains which elements can maintain BTC’s value when users turn to alternative payment services. The analysis results indicate that BTC does not exhibit the typical characteristics of the elements analyzed. It means that it does not meet the set of monetary criteria, is not solvent in any asset category, does not meet the requirements of a traditional pyramid model, and, as a service, has been surpassed by subsequent developments based on the technology created.

Therefore, the research results align with the literature’s expectations, suggesting that BTC should not be considered a currency but rather an investment asset. It has compelled the individual to examine its characteristics, as seen in the present study. Moreover, unlike earlier works suggest, one should not regard BTC as a pyramid scheme or a novel model, because it cannot be separated from the technological advancements in BTC-related trading.

5. Discussion

BTC was introduced in 2009 as a revolutionary technology offering numerous advantages for transactions. It enabled the reduction, and in some cases elimination, of spatial, temporal, and cost barriers, while providing a secure and reliable cryptographic transaction environment through specific security and information elements. The novelty in security lies in its protection through a combination of public and private keys that confer ownership. A private key is required for the user (i.e., the payer) to transfer cryptocurrency anonymously to another user (i.e., the beneficiary) on the network, without the possibility of reversing the operation (

Bonneau et al., 2015).

Under these conditions, it became a revolutionary means of exchange, fulfilling the first criterion of monetary function and even surpassing the performance of other existing monetary options. This situation enabled them to build trust, facilitating their daily exchanges, whether for transactional or investment purposes in BTC.

This paper focuses solely on BTC-related conceptual aspects, assessing its behavior based on the available academic literature and the results obtained. Therefore, this examined its role in society. As can be seen, no mention is made of technical aspects on which BTC is based, such as the reliability of its Blockchain network, its behavior in the face of cyberattacks, or the possibility that agents with large computational capacity could intervene in the network, all aspects in which the BTC network has performed very well to date. In searching for BTC’s place among the elements available in today’s economy, the first element discussed is its monetary behavior.

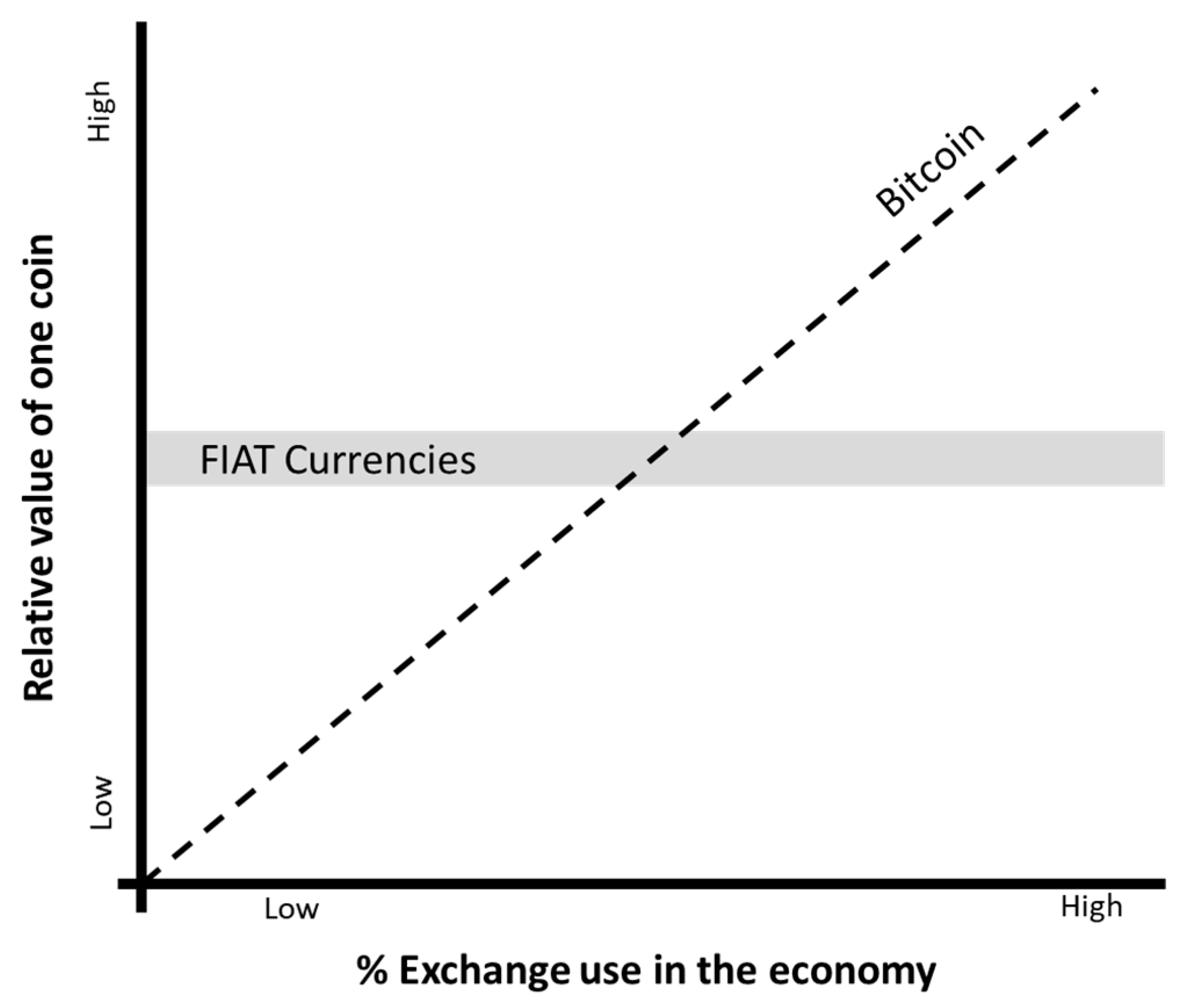

All the analyses concluded that it does not meet the basic criteria for financial consideration. Firstly, as a medium of exchange, the current situation does not show widespread adoption by the population. Even major technology companies have occasionally tried to accept payments using BTCs. However, its level of acceptance is currently minimal. Individuals might adopt it if other monetary issues are resolved, even though they do not currently use it as a payment method. It is also important to note that the limitations associated with BTC’s initial technological capabilities have been overcome, enabling card payments comparable to those offered by commonly used credit or debit cards. Secondly, it has the condition of unit of measure, which, as the data show and the studies analyzed confirm, BTC is currently not satisfied. Given its well-studied volatility, it is unfeasible to measure any economic aspect of BTC with confidence that the measurement will remain valid in the short term. This element also behaves in the opposite way to that of a medium of exchange, because a hypothetical increase in the use of BTC for economic transactions would, if anything, lead to greater demand and deflationary behavior than is currently seen in BTC as a unit of measure. Both elements, units of measure and medium of exchange, are presented in

Figure 6, where the relative value of the BTC increases as its utilization grows, as indicated by the dashed line. However, stability in the use of BTC could correct the situation shown in the figures if it were to gain widespread acceptance as a means of payment. It has also proposed a third level of use as a store of value, an aspect that is also highly controversial given its performance to date. Without guarantees of compliance with the unit of accounts, it is impossible to consider it to meet the criterion of a store of value, because, given the history of cryptocurrency, any amount available in BTCs will be subject to high volatility, and therefore, no reliable expectations can be made about the future value of the cryptocurrency. Similarly, since it does not guarantee compliance with the above criteria, it is impossible to use BTC as a standard for future payments. Considering the initial design of BTC and its use for over ten years, it does not meet the criteria for a currency; therefore, it is not a functional currency under current conditions. The concept of cryptocurrency that BTC emerged from is no longer representative of what BTC is today.

Everything discussed suggests that BTC does not meet the criteria to be considered a currency. However, this cannot be regarded as an insurmountable limitation, as it could meet the requirements set out above if stable conditions of use were to arise in the future. Conditions that could apply to BTC or be incorporated into the design of future monetary solutions, whether they depend on governments or promote the decentralization of economies.

In addition, a fixed and unchangeable issuance volume will constrain the currency if currency stability is achieved. This would mean that, just as fiat currencies are subject to regulated inflation conditions, their monetary use is not neutral with respect to the economy. BTC would be subject to fixed conditions that cannot be adjusted to the economy’s performance, resulting in deflationary conditions during periods of economic growth and inflationary conditions during periods of decline, implying non-neutral monetary conditions in financial behavior. This means that, under conditions of economic development, as expected across different economies, the monetary conditions of BTC promote saving over consumption, driven by the expectation of future increases in purchasing power. Similarly, they would reduce credit’s attractiveness, as their repayments would become progressively more expensive. To illustrate, dividing 21 million BTCs equally among about 8 billion people would give each person 0.0026 BTCs. However, if its use were to spread to an entire society of 10 billion inhabitants, the average would be 0.0021 BTCs per citizen. It implies a 20% drop in the per-unit availability of money. This drop does not account for the impact of the expected increase in economic production needed to meet each person’s needs.

When considering BTC as an asset, the analysis shows behavior that is inconsistent with the classifications of assets available in the economy. Considering BTC as a cryptocurrency could initially place it alongside other monetary assets as a store of value. However, the data shows behavior that is highly correlated with capital goods, with which it does not share the possibility of offering a return on investment in the form of dividends or other forms, but rather through the direct valuation of the asset in the market. In contrast to the above, it presents a distribution of value variations that is more typical of monetary assets than of capital assets. Under these conditions, placing BTC in any asset superclass is impossible, raising the question of whether it should be considered a new asset class.

Under these considerations, the role of gold as a benchmark asset in the conception of BTC stands out once again, as it behaves in two ‘superclasses’ at the same time: on the one hand, as a store of value and, on the other, as an asset subject to transformation. The money market needs this comparison because gold is considered the benchmark asset. Even though BTC and gold share similarities in terms of scarcity and durability, a fundamental difference lies in the fact that modern economies have widely accepted gold as a monetary unit, driven by people’s desire to own it and its inherent scarcity. The desire to own it stems from non-monetary criteria, linked to social status and power, among other factors. Indeed, the secure and stable demand for physical assets allows for their monetary use.

Additionally, BTC is treated as fiat money; its value is determined by the trust placed in its issuer. Its issuer can be determined based on the founding white paper published by Satoshi Nakamoto in November 2008, which established the conditions for BTC issuance. Therefore, considering that its issuer has become a decentralized network of computers that collaborate to record all transactions reliably and predictably, and systematically operate in the issuance of the currency. Under these conditions, the currency’s value rests exclusively on society’s trust in that currency. Considering all the above, the value of BTC depends on its use being of interest to society; that is, it offers a solution that is preferable to others. Among these solutions, two can be considered primary: on the one hand, the monetary function, if it meets the conditions that guarantee compliance with the criteria of unit of measure, medium of exchange, and store of value discussed throughout the document.

On the other hand, considering that it offers a service demanded by society, the main form could be that of a medium of exchange independent of central banks. With this second option, the value would depend on BTC’s ability to offer a service on terms that are more advantageous than those of other services. The exchange service mentioned earlier in this document initially provided advantages over other exchange solutions, including transaction speed, costs, security, anonymity, and order automation, all of which were revolutionary features in 2009 when the first BTC was issued. However, the technological development derived from this innovation has since enabled further advances in services. These developments are likely to continue improving and offering new solutions.

Considering BTC as a service, whose value depends on society’s valuation, means the service can be provided equally regardless of BTC’s value, with the only difference being the number of BTC required to obtain it. In this case, the problem with the service arises when BTC is held for an extended period, at which point the service assumes the risk of BTC volatility. All voluntary exchanges in society occur because people consider the acquired item preferable. Individuals value fiat money for their expected capacity to be exchanged for desired goods and services.

From the perspective of the quantitative theory of money, we find ourselves with a fixed amount of cash, more commonly referred to as “M”, on which it is not possible to make decisions regarding expansion or contraction. This implies that any adjustment in its use in the real market will likely lead to a corresponding adjustment in the P/V ratio. Indeed, this presupposes that the speed of exchange remains relatively constant. In that case, any adjustment in the use of money becomes an adjustment in prices over which there is no remedy due to the absence of an institution responsible for regulating the money supply.

The value of fiat currencies does not depend only on their use in society. When there are variations in its use, central banks can intervene in the currency to prevent inflationary or deflationary episodes, as indicated in their objectives.

Figure 6 illustrates the issue with a gray band, as the effect of central bank decisions on economic lag can lead to deviations. In contrast, BTC’s monetary supply or volume is entirely independent of how citizens use it, meaning that when demand for BTC increases, its price will rise, and vice versa. Consequently, its economic behavior causes deflation; therefore, increased usage means it can buy the same goods with fewer BTCs, which central banks are trying to avoid.

BTC emerged over a decade ago as a new form of currency that conferred freedom of action due to its independence from governments or central banks. It was a novel proposal thanks to its reliability of operation and the search for independence from any actor. Furthermore, the collection of extensive data over the past fifteen years has enabled a reassessment of the proposed monetary model’s outcomes from a distinct analytical perspective, using relevant statistical data.

Although BTC has not managed to obtain the properties of a currency, it has paved the way for decentralized monetary models in which no authority can arbitrarily decide on its behavior, while at the same time opening the door to the development of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) that move in the opposite direction, strengthening the control and decision-making capacity of central banks. BTC has shown how, through technological tools, it is possible to launch an alternative to fiat money that society receives with interest. It has shown how the market is considering its integration into the means of exchange and how different governments are responding, among other things, by incorporating this threat into their tax systems. Thus, this step can be seen as successful in developing an international and independent monetary system. However, the conditions under which it was created have led it to be perceived more as an investment asset than as money itself. The high volatility that has characterized its behavior from the outset has attracted investors seeking profitability more than citizens interested in a new monetary offering.

Beyond the social utility of BTC, which gives it value, a community of investors has invested large sums of money in acquiring such a cryptocurrency and in the significant computing power required for mining. All these people are interested in maintaining BTC’s value. Therefore, they are expected to contribute to this to the extent that they can achieve new gains and avoid further losses. That said, if demand for BTC declines due to a lack of use as a service or a decrease in value expectations, it could continue to maintain a specific value associated with other reasons for its possession. The ‘cryptomarket’ may resemble specific art markets in some respects, but there are also significant differences across cryptocurrencies. The parallel is that, to a certain extent, owning BTC is analogous to owning art, serving as a status symbol or something of that nature. The fact that each BTC is traceable becomes apparent with the value of owning a unique asset after its issuance, even if its value was initially zero. Indeed, the scarcity of BTCs has traditionally been the primary lever to its high demand. It could even reveal details such as the coins’ traceability, issue date, and past owners involved in mining the initial BTC with Satoshi Nakamoto.

5.1. Considerations When Assessing Whether Bitcoin Is a Payment Service

It has been faced with a monetary element whose only real functionality is as a means of exchange. Thanks to the functions described above, transactions can be made quickly, cheaply, securely, and internationally, all in accordance with current standards. This service is also innovative, as physical credit cards and virtual payment terminals have been introduced into the cryptocurrency market. This development, which occurred a generation ago, enabled payments anywhere in the world without carrying cash or needing change. The market has now surpassed these physical cards and has widely adopted cell phones and other wireless devices. Including blockchain technology could technically advance previous payment methods.

Understanding BTC as a service means its use has a beginning and an end, as its users find alternative services to handle the transactions they currently hold with BTC. Those transactions could be performed in other cryptocurrencies or other alternative tools. In addition, companies back credit card services whose business model depends on the quantity and quality of the service they offer, which they will try to maintain. This implies a direct responsibility for service quality, which could result in losses if it fails to meet customers’ expectations.

In contrast, there is the case of BTC, whose operation is supported by a community of miners (whether individuals or companies) whose objective is also to obtain a return on their activity (at the very least, they do not want to suffer losses), but with the difference that the return is based on different foundations than those of the card companies. In this case, they do not depend on the quality of service unique to the blockchain network. They rely on the volume of mining services performed, their costs, and the value of the currency in which they receive BTC rewards, which makes their profitability an element over which they have little scope for action beyond relative cost control.

5.2. Considerations When Assessing Whether Bitcoin Is a Ponzi Model

All the above reasoning leads us to consider that we are faced with a cryptocurrency that does not fulfil monetary functions. This cryptocurrency is, in turn, a non-remunerated financial asset not backed by a central bank. It offers a revolutionary service that is vulnerable to obsolescence as the technology on which it is based evolves. It causes the problem of identifying the proper service to exchange value to fulfill its function. The exchange value depends on its demand, regardless of whether it is based on exchange or investment motives.

According to the present study, BTC appears to be a decentralized service, yet it is regarded as a currency and has behaved more like an investment asset. As a service, it benefits from network effects as more people adopt BTC, thereby expanding opportunities for existing users. For instance, the fact that merchants or chains accept payment in ‘cryptocurrency’ generates value for existing users of ‘cryptocurrency’. Therefore, the question now arises whether BTC behaves like a Ponzi model.

The present study’s findings do not suggest that the value of cryptocurrencies, whether regarded as real or financial assets, depends on the entry of new users or the overall volume of their transactions. If new users trust the currency and conduct more transactions, it will be closer to a monetary model, and therefore, its value can be expected to increase.

This paper has not assessed BTC’s features related to decentralization or technology. However, the study aims to analyze the fundamental aspects, focusing on its economic performance as a currency, asset, or service. In sum, in addition to being an aspiring currency, BTC is an aspiring monetary asset that is currently closer to a capital asset, given the bet on its value increasing as it is recognized as such. Furthermore, it is an international transaction service with distinct advantages over other banking systems in terms of costs, speed, and security.

6. Conclusions

In its classical economic conception, money must fulfill the three functions outlined in

Figure 1. That is, it must be a means of payment, a unit of account, and a store of value to be considered a possible alternative to traditional fiat currencies. Its decentralized design and issuance limit of 21 million units reinforce this. However, the analysis presented here reveals that BTC, as a cryptocurrency, exhibits certain structural deficiencies that may hinder its consolidation as a viable alternative to money. The first criterion for money is its ability to facilitate rapid, large-scale exchanges at low transaction costs. In this regard, the use of BTC as a means of payment has increased awareness and driven up its prices. Although individuals can use it as a payment method, its use could be more widespread in niches such as international transfers or exchanges between digital users, albeit limited in other areas, which reduces BTC’s overall efficiency as a universal payment method. The second function of money is as a stable store of value over time. Until now, BTC has been characterized by extreme volatility, with daily fluctuations reaching double-digit levels, further complicating the preservation of economic wealth for individuals and companies.

Furthermore, unlike fiat currencies, which are backed by national economies and central banks, BTC lacks institutional support to guarantee its stability because its price depends on the expectations of its holders, the market itself, and associated speculative phenomena, which would make it more like a high-risk investment asset than a reliable store of value. The third function of money is to act as a standard measure of value or unit of account. In this regard, the prices of goods and services are expressed in fiat currencies such as the euro or the US dollar. At the time of the transaction, the system converts them into BTC at the current exchange rate. This implies that BTC fails to serve as an account unit because it relies on the reference values of traditional currencies. Consequently, the findings suggest that BTC, in its current state, may not be a fully functional currency, as it can be inefficient as a global means of payment in certain instances. As a store of value, it is unstable due to daily fluctuations. Individuals often refer to it using other fiat currencies; therefore, it is practically nonexistent as a unit of account. Rather than a monetary alternative, BTC could be considered a speculative digital asset or an emerging financial asset, with utility dependent on its technological innovation, but limited capacity to replace fiat money.

Finally, with respect to the second research question and after studying BTC’s performance as an asset and analyzing the different types of assets, capital goods, tradable goods, or store-of-value goods, the study focused on BTC’s behavior, concluding that BTC is not fully represented in any of the three prominent asset families, showing behavioral relationships more consistent with capital goods. However, a growing similarity can be observed in characteristics such as symmetry and kurtosis linked to store-of-value assets.

According to research findings, BTC’s evolution reveals a broader monetary challenge beyond its statistical behavior as an asset. Accordingly, BTC faces the inherent problem of being deflationary in relation to economic growth, implying that its monetary function is not neutral to the economy’s functioning. In the event of widespread adoption, such dynamics could distort intertemporal preferences, discouraging spending and investment. Moreover, in its monetary role, technological innovation poses a structural threat to BTC’s long-term viability, as emerging technologies may render its value proposition obsolete, particularly given the technical constraints of Nakamoto’s original network design.

7. Future Research Directions and Research Limitations

This paper lays the groundwork for future research on the use of BTC within the financial sector. In particular, further studies could validate and expand the comparative analysis presented in this paper to include other essential cryptocurrencies, such as Litecoin (LTC), Chainlink (LINK), Cosmos (ATOM), and Monero (XMR). Additionally, a quantitative modeling approach could be applied to identify the potential risks posed by cryptocurrency mixing services, also known as ‘tumbler’ or ‘fogger’, within the expanding ecosystem of blockchain-based decentralized marketplaces.

As previously stated, the results presented in the paper do not provide absolute certainty that BTC should be considered a circulating currency in a traditional monetary sense. This does not prevent future decentralized cryptocurrencies, under very special circumstances, from being entrusted with three basic functions of money: a store of value, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange. However, without a monetary authority regulating the amount of digital cash in the global market, disruptive technologies such as coin-issuing entities pose a significant obstacle to their being considered truly disruptive.

Although this study analyzes many elements common to other cryptocurrencies, not all analyses agree, and the conclusions are not applicable. In addition, given the large daily volume of stablecoin trading and the threat posed by the issuance of central bank digital currencies, it is crucial to analyze their role as currencies rather than as payment services, as outlined here. The primary objective of future analysis should be to determine the issuance conditions that enable a decentralized currency to meet the price-stability criteria required for its general adoption.

Nonetheless, it is reasonable to believe that other cryptocurrencies, such as ETH or BNB, may exhibit different behaviors, either due to the approaches outlined in their white papers at launch or to technological developments that influence their development. Facts such as their mining and issuance conditions or the services associated with their blockchains may yield very different results, and it may even be the case of creating crypto assets that fulfill all monetary functions. In recent years, interest in this regard has shifted to analyzing Ponzi schemes on the Ethereum blockchain, given the opportunities offered by its smart contracts (

Zhang et al., 2021). In this sense, each selected coin can be analyzed independently to assess its potential as a stable currency option.

This paper’s primary line of research is the definition of an issuing and payment system configuration that would enable a new cryptocurrency to become a stable and reliable alternative for making payments to the population. Moreover, this approach defines the criteria for launching a BTC alternative, including a more solid foundation, as individuals have sought an independent, free, and secure monetary option since the inception of computing technology.

As with cryptocurrencies, stablecoins require a particular analysis and classification, both from a monetary and a business perspective. In their economic role, a study examines their contribution to developing the financial ecosystem through their services. Their business role involves increasing exchange risk by adding to the base currency’s risk, typically USD-based, as well as the risk associated with the company issuing the stablecoin. Additionally, it involves analyzing the issuing companies’ capitalization, investment, and debt ratios. At this point, it would shift towards an independent value based on neutral conditions concerning economic behavior. In either case, although BTC has been around for 15 years, its behavior can still be considered novel and incipient, given that it is the first monetary proposal based on technology with significant international reach in a globalized world. This means that the time horizon for analyzing monetary behavior remains limited.