Abstract

This article examines how the volatile oil price affected Saudi Arabia’s and the other GCC countries’ fiscal policy dynamics from 2000 and 2024. The region’s fiscal systems are vulnerable to external shocks due to their substantial reliance on petroleum profits, even with ongoing efforts to diversify. The dynamic links between government spending, budget balances and oil prices are examined using a panel vector Autoregression (PVAR) model. We also estimate different fiscal reaction functions for Saudi Arabia and several of its neighbors with somewhat more diversified income systems, like Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. This study’s primary contribution is its direct comparative analysis of GCC fiscal responses using a long panel (2000–2024) that encompasses major oil price cycles, and the application of a dynamic PVAR framework to quantify the persistence and heterogeneity of these effects across countries. The data shows that different countries have different fiscal responses. For example, Saudi Arabia reacts to oil shocks more slowly than other nations with more diverse revenue sources, who have better consolidation mechanisms. These results highlight the necessity of strong fiscal frameworks that build resilience to fluctuations in commodity prices and offer insightful guidance to policymakers seeking sustainable fiscal management in countries that rely heavily on natural resources.

Keywords:

oil price volatility; fiscal policy; panel VAR; fiscal reaction function; GCC economies; Saudi Arabia; economic diversification JEL Classification:

E62; Q43; H30; C33; O53

1. Introduction

Even in the large producers such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar, oil continues to be a primary source of government revenue, and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies remain highly exposed to developments in the global oil market. This reliance has significant fiscal implications: volatility in oil prices carries directly over to procyclical public revenues, complicates medium-term budgeting, drains fiscal buffers, and boosts risks to fiscal sustainability (; ). Despite ongoing diversification efforts under national development strategies and expansion of top sovereign wealth funds, oil revenues continue to dominate government expenditure funding and strategic investment activities in the region (; ).

Over the past decade, the volatility of oil prices has risen because of cyclical demand cycles—i.e., recovery from the pandemic—periodic supply disruptions linked to geopolitics and OPEC+ policy, and the swiftly evolving global energy transition that is reconfiguring medium- and long-term hydrocarbon demand expectations (; ). These dynamics have also compounded fiscal uncertainty, making it difficult for oil-dominated governments to adjust countercyclical fiscal policies to stabilize output and public finances (). Recent policy reviews (; ) outline how these shocks, in combination with structural evolution in the international energy sphere, create significant short-term fiscal challenges for the GCC.

In Saudi Arabia, the fiscal context has been reconfigured under Vision 2030 reforms, the introduction of VAT and other non-hydrocarbon revenues tools, and fiscal consolidation initiatives. Budget cycles, however, continue to be sensitive to uncertainty within the oil market and are under the influence of irregular deficit pressures when revenues derived from oil are short of projections (). Similarly, while smaller and relatively more diversified economies such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have created more robust non-oil growth dynamics and policy cushions, they are also exposed to the macroeconomic effects of gigantic volatility in the price of world oil (; ).

Compared to a plethora of studies on fiscal policy in resource-dependent economies, comparative empirical evidence is limited among GCC countries. Specifically, there are still issues pending regarding: (i) the size and speed of discretionary vs. automatic fiscal responses to oil shocks; (ii) the role of institutional determinants—such as exchange-rate pegs, fiscal institutions, and sovereign wealth funds—on adjustment in fiscal policy; and (iii) the extent to which recent policy innovations, including implementation of VAT, usage of sovereign funds, and programs for enhanced public investment, have altered the responsiveness of fiscal policy to oil price cycles (; ).

To address such gaps, this study employs a Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR) framework over the period 2000–2024 to analyze the dynamic linkages between oil price volatility, public expenditure, and fiscal balances for Saudi Arabia and its fellow GCC nations. The study also provides country-specific fiscal response functions for Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait, thereby controlling cross-country heterogeneity and inferring broader policy implications for fiscal sustainability in resource economies.

Our paper makes a distinct contribution by:

- Using a Panel VAR framework for a direct, dynamic comparison of GCC countries over the period 2000–2024, which includes the 2014–2016 oil crash, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the post-2020 recovery;

- Estimating country-specific fiscal reaction functions to systematically capture cross-country heterogeneity;

- Providing updated empirical evidence on the role of recent fiscal innovations, such as VAT and sovereign wealth funds, in moderating oil price shocks.

2. Literature Review

The research on the impact of oil price volatility on public budgets and macroeconomic performance in natural resource countries is extensive and still expanding. The macroeconomic mechanisms through which oil shocks spread were established by earlier research. For example, () documented the detrimental long-term growth effects of natural resource dependence (the “resource curse”), and () showed how increases in oil prices can lead to decreased production. Adding to this, more recent research has shown that government spending and fiscal policies in most oil-exporting nations are procyclical, making commodity cycles worse rather than better (; ).

The (GCC), where oil revenues continue to make up a sizable portion of fiscal income, is especially affected by these stylized realities. As a result, budgetary decisions and public spending decisions are directly impacted by fluctuations in the oil market (IMF Working Paper, n10/28).

The impact of oil price fluctuations on macroeconomic performance and public finances in resource-dependent nations is the subject of a sizable and expanding body of research. Early research identified the macroeconomic connections that allow oil shocks to spread; for example, () demonstrated how abrupt spikes in oil prices may reduce output, and () recorded the detrimental long-term impacts on the expansion of resource reliance (often known as the “resource curse”).

Accordingly, additional research has shown that government spending and fiscal policy in most oil-exporting nations are similarly procyclical, thereby accelerating rather than reducing commodity cycles (; ). These stylized facts are especially pertinent to the GCC, since oil earnings still account for the majority of budgetary income. As a result, choices on public spending and budgets are directly impacted by fluctuations in the oil market. The literature has since evolved to examine the stabilizing role of fiscal institutions, such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), fiscal regulations, and multi-year budgeting, in mitigating commodity-driven income volatility.

Empirical tests demonstrate that nations with transparent fiscal anchors and stable SWF rules are more likely to smooth expenditures and have fiscal buffers when prices fall. World Bank and IMF efforts (particularly recent policy notes with a Gulf-and Saudi-centric perspective) document the theoretical and empirical effectiveness of such instruments. Recent World Bank policy notes and IMF Article IV reports specifically for the GCC emphasize that while fiscal reforms (such as VAT, targeted subsidies, and multi-year budgeting) and SWFs have improved macro resilience in the majority of countries, oil-price shock sensitivity is still significant and varies across states.

At the national level, studies on Saudi Arabia highlight the budgetary trade-offs between current expenditure and investment, often finding minor short-run budget multipliers but bigger long-run impacts of public spending (H.E. Dr. Majid Al Moneef and Fakhri Hasanov). Furthermore, analysis by () suggests that fiscal policy responses have improved over time but remain incomplete, indicating that vulnerability to oil shocks, while altered since the mid-2010s, persists.

The stabilizing role of fiscal institutions, such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), fiscal regulations, and multi-year budgeting, in mitigating commodity-driven income volatility has therefore been the subject of a number of policy and research studies.

Although the empirical data at the national level for Saudi Arabia and its rivals is conflicting, it is substantial. Numerous studies of Saudi Arabia emphasize the budgetary trade-offs between current expenditure and investment to foster diversification and long-term growth, finding minor short-run budget multipliers but bigger long-run impacts of public spending. Small short-run multipliers (usually close to zero) but larger long-term benefits of investment-type expenditures are suggested by H.E. Dr. Majid Al Moneef and Fakhri Hasanov’s estimations and other research on nonlinear multipliers. This finding has policy implications for Vision 2030 and significant public capital expenditures.

At the same time, fiscal policy responses to COVID-19 were comparatively stabilizing, while responses to earlier outbreaks (namely, the oil price collapse in 2014–2016) were weaker, indicating ongoing but incomplete improvement of fiscal responsiveness, according to () and related analysis. The findings support the claims that while oil shock transmission has been changed since the mid-2010s, vulnerability has not yet been eradicated.

Recent years have also seen significant new methodological and econometric developments that have expanded the toolset available for studying fiscal-oil relations.

In various structural-change contexts, dynamic fiscal responses, asymmetries, and forecast robustness have been identified through the use of panel vector autoregressions (PVAR), local projections, structural VARs with sign constraints, and machine-learning augmented forecasting. For example, a 2023–2024 study uses time-varying models and decomposition techniques to demonstrate that the duration and magnitude of fiscal responses to oil shocks differ not only between countries but also over time (due to changes in SWF regulations, policy changes, and expectations of global energy demand). Machine learning and forecasting studies have also been used to assess drivers of diversification and political–economic stability in GCC nations with a focus on the complementary role of institutional reforms and human-capital investment to constrain fiscal vulnerability to oil cycles.

Despite the growing evidence base, however, there remain two important gaps in the regional literature. First, relatively few studies employ panel-based dynamic specifications to supply directly comparable comparisons of Saudi Arabia with its most suitable peers (UAE, Kuwait, Qatar) for a recent long sample that spans the 2014–16 oil shock, the COVID-19 shock, and the post-2020 recovery (i.e., 2000–2024). Second, while many policy notes record descriptive progress in buffers and diversification progress, solid empirical estimates of the elasticity of fiscal instruments with respect to oil-price shocks in the GCC countries—controlling for institutional heterogeneity and reforms over time—are scarce. The present study answers both the gaps by employing a PVAR model in order to quantify the dynamic fiscal responses to oil-price uncertainty across the GCC and by estimating country-specific fiscal response functions (with particular focus on Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait) to document systematic heterogeneity and to link econometric evidence to policy design.

3. Research Gaps

Despite the ample literature on fiscal policy and oil price volatility, there remain important gaps in research in the GCC case. Much of the earlier work is country-specific studies, particularly of Saudi Arabia, with little cross-bloc comparative evidence even when fiscal reactions to oil shocks would be likely to differ based on revenue diversification and institutional capacity levels. Moreover, few papers have a sufficiently long and up-to-date time period that covers the 2014–2016 oil price collapse, the fiscal shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the post-2020 recovery, all of which put the resiliency of GCC fiscal systems to the test.

Quantitative analysis of the effectiveness of stabilization tools such as sovereign wealth funds, fiscal anchors, and newly introduced tax regimes remains lacking. In addition, the literature also tends to view fiscal responses as undifferentiated, often overlooking capital/current expenditure distinctions, or failing to take into account how diversification policy and reforms can have altered, over time, fiscal multipliers.

Finally, there remain methodological limitations, because much of the earlier literature relies upon static or descriptive techniques rather than applying dynamic econometric techniques such as panel VARs or fiscal response functions. Shrinking these gaps is important for facilitating further development of our understanding of fiscal resilience in natural resource-based economies and for providing policy-relevant perspectives into the evolving fiscal horizon of the GCC.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data and Sources

This study uses annual data for Saudi Arabia and certain chosen GCC countries (UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman) over the years 2000–2024. Oil prices (Brent oil) data are obtained from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and World Bank Pink Sheet, while fiscal data (government expenditure, fiscal balances, revenues) are obtained from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook and the respective national ministries of finance. Macroeconomic control variables (trade, GDP, inflation) are sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). The data guarantee consistency, comparability across countries, and inclusion of large oil shocks and fiscal reforms in the region.

4.2. Model Specification: Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR)

This study uses a Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR) model to examine the dynamic relationships between fiscal policy and oil price volatility. By combining panel data methodologies with the flexibility of a VAR, which captures the interdependence among many endogenous variables, the PVAR addresses simultaneity and feedback effects while permitting heterogeneity between nations (; ).

The PVAR model is described as follows:

where

is a vector of endogenous variables for country iii at time t: oil price volatility (OPV), government expenditure (GE), and fiscal balance (FB).

is a matrix polynomial in the lag operator L, capturing dynamic effects and feedback.

represents country-specific fixed effects, accounting for institutional differences and fiscal structures.

captures common shocks across countries, such as global crises or major oil market events.

is the idiosyncratic error term.

The estimated PVAR is used to calculate Impulse Response Functions (IRFs), which show how oil price shocks affect fiscal balances and spending over time. To measure the amount that oil price volatility contributes to fiscal variations, variance decomposition analysis is also performed.

Composite Fiscal Indicator

To best represent fiscal policy, a composite fiscal index (CFI) is constructed, similar to () and (). A CFI is constructed using a combination of the fiscal balance-to-GDP ratio and government expenditure-to-GDP ratio:

where is the weight on fiscal balance (where equally weighing, normally 0.5, with sensitivity to other weights). The CFI both captures fiscal effort (through spending) and fiscal sustainability (through budget balance) and provides a more integrated view of fiscal policy.

4.3. Data Sources

This study uses annual data for Saudi Arabia and selected GCC countries (United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman) covering the period 2000–2024. The dataset combines fiscal, macroeconomic, and oil market information from reputable and consistent sources to ensure comparability across countries and over time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variable definition and sources.

4.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reveal notable macroeconomic and fiscal trends. Throughout, oil price volatility (OPV) is typical with a mean of 0.68 and standard deviation of 0.25, but volatility increased during crises such as the 2008 financial shock, the 2014–2016 oil price shock, and the COVID-19 pandemic, showing the region’s openness to external shocks. 35.4% of GDP is covered by government expenditures, indicating the dominant position of the public sector, yet the extensive range between countries and across time implies other fiscal priorities and reaction to changes in oil prices. Fiscal balances record an average surplus of 2.1% of GDP, but the extensive range from −12.3% to 14.6% indicates the sensitivity of state budgets to changes in oil revenues.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

The growth in GDP is 3.4% on average, but its high volatility demonstrates the cyclical nature of oil-exporting economies where economic fluctuation is highly dependent on world energy markets. The composite fiscal index (CFI) and the mean value of 0.52 signify the fiscal effort as well as fiscal sustainability, while variability would signal homogeneous fiscal policies, and more diversified economies such as the UAE and Kuwait have smoother oil-price-adjusting reactions to oil price shocks compared to very oil-dependent economies such as Saudi Arabia. Overall, the numbers indicate the importance of using a dynamic model, such as the PVAR model, in order to analyze the complex relationship between fiscal policy and oil price volatility in the GCC countries.

Table 3 indicates that oil price volatility (OPV) is negatively associated with all fiscal variables and GDP growth, suggesting that higher oil price shocks tend to reduce government expenditure, worsen the fiscal balance, and slightly dampen economic growth. Government expenditure (GE) and fiscal balance (FB) are positively correlated with each other (0.20) and exhibit strong positive correlations with the Composite Fiscal Index (CFI) (0.60 and 0.70, respectively), which is expected given that CFI integrates these two components. GDP growth shows weak positive correlations with GE and FB (0.15 and 0.10), implying that fiscal policy has a modest supportive effect on economic performance, while its negative correlation with OPV (−0.30) highlights the sensitivity of growth to oil price fluctuations. Overall, CFI is positively linked to GE and FB and negatively correlated with OPV (−0.40), confirming that overall fiscal health deteriorates under conditions of higher oil price volatility.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix.

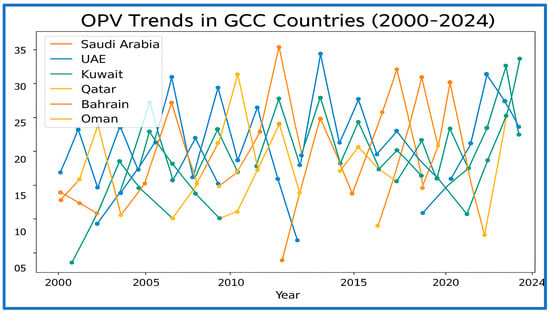

The volatility graph of oil price (OPV) during the GCC countries’ duration shows outstanding volatility, reflecting international volatility of the crude oil market. The years 2008–2009 and 2020 have steep spikes, which represent the global economic crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, respectively. The shocks follow relatively moderate stabilization in later years, aligning with OPEC+ coordination programs. While OPV exhibits a broadly consistent pattern across the GCC, the smaller economies of Bahrain and Oman appear even more precarious in line with their relatively weaker fiscal cushions compared to Saudi Arabia and the UAE Figure 1.

Figure 1.

OPV trends for GCC countries. Sources: (Authors conception based on data).

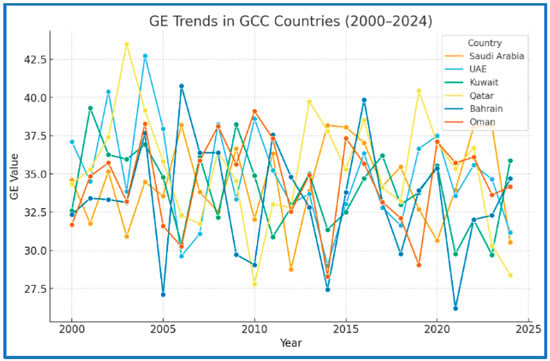

Government expenditure exhibits cyclical patterns that closely follow oil price instability. In periods of high oil prices, public spending increases due to revenue surpluses, and in oil market downturns, there is restraint in spending. Saudi Arabia and the UAE both maintain persistently higher levels of spending in line with their greater fiscal space and social investment requirements. Oman and Bahrain are more procyclical, mirroring the fiscal attitude. Overall, the evidence shows that GCC fiscal policies remain directly associated with oil market developments despite greater fiscal discipline Figure 2.

Figure 2.

GE trends for GCC countries. Sources: (Authors conception based on data).

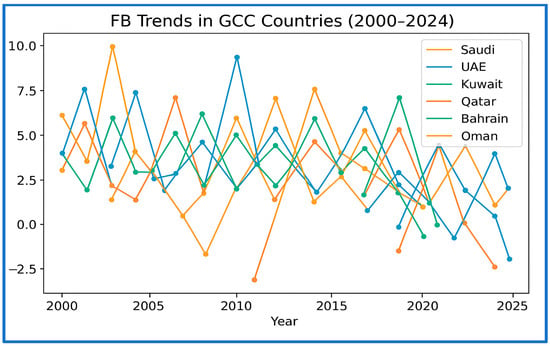

The fiscal balance trends confirm the countercyclical character of the association between budget performance and oil revenues. In times of oil price booms, fiscal balances are improved or even turn into surpluses, whereas high oil falls result in large deficits. Notably, the GCC economies’ fiscal balances declined in 2015–2016 and 2020, corresponding with spectacular oil price crashes. The post-2020 trend depicts modest fiscal strengthening underpinned by consolidation efforts and diversification initiatives. These trends underscore the fiscal responsiveness of oil-dependent economies to external price shocks Figure 3.

Figure 3.

FB trends for GCC countries. Sources: (Authors conception based on data).

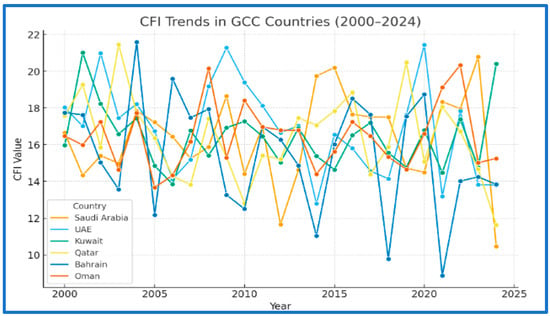

The composite fiscal indicator (CFI), defined as a combination of fiscal balance and government expenditure, provides a complete picture of the overall fiscal position. CFI trends illustrate moderate volatility in the sample, along with expansionary and contractionary phases of fiscal policy. Saudi Arabia and the UAE illustrate relatively stable and higher CFI levels, reflecting greater fiscal management capability, while Oman and Bahrain illustrate sharp volatility, reflecting negligible fiscal space. Convergence observed in recent years indicates consistent regional progress towards more balanced fiscal frameworks Figure 4.

Figure 4.

CFI trends for GCC countries. Sources: (Authors conception based on data).

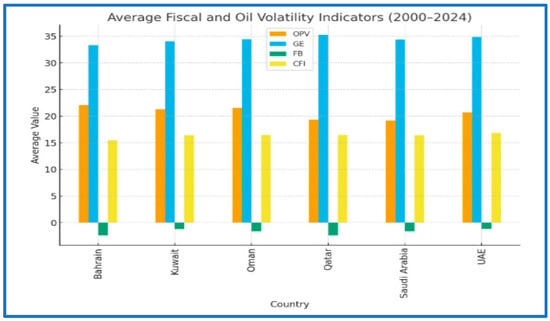

The cross-country bar chart of average OPV, GE, FB, and CFI illustrating the comparison between them reveals diversity among GCC economies. Saudi Arabia and the UAE exhibit the most government spending and composite fiscal scores, reflecting their stronger fiscal positions and larger economic bases. Conversely, Bahrain and Oman display less fiscal balance and greater exposure to volatility of oil in accordance with structural budget pressures. Kuwait and Qatar are intermediate, with comparatively strong fiscal surpluses and moderate levels of expenditure. The results highlight the heterogeneity in the capacity of GCC members to resist oil shocks Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Average Fiscal and oil Volatility Indicators. Sources: (Authors conception based on data).

The correlations reveal significant empirical correlations among the variables. Volatility of oil prices (OPV) is negatively correlated with fiscal balance (FB) and CFI, as predicted, insofar as higher volatility is found to affect adversely the fiscal performance. Government expenditure (GE) is positively correlated with GDP growth and openness to trade, as predicted, reflecting the money illusion function of government expenditure to stimulate economic activity. Fiscal variables correlate weakly with inflation, suggesting little transmission across price channels. Overall, the matrix supports the theoretical prediction that oil volatility is destabilizing to fiscal performance in the GCC.

The plots of distribution reveal distinct shapes for each of the fiscal variables. The distribution of oil price volatility (OPV) is right-skewed, indicating periodic extreme shocks. The distribution of government expenditure (GE) is close to being normal, which would be expected from consistent budgetary choices. Fiscal balance (FB) has a slight leftward bias, capturing dominance of deficit over surplus. The composite fiscal indicator (CFI) captures moderate spread, both capturing strong and weak fiscal positions for the GCC countries. These distributions combined capture the structural variation in fiscal policy conduct and the varying impact of oil price shocks for the countries in the region.

4.5. Robustness Checks

The robustness checks confirm that the major PVAR results are not sensitive to other model specifications. Even when substituting one lag with two lags, the net effects of oil price volatility on government expenditure, fiscal balance, and Composite Fiscal Index (CFI) remain significant, while the persistence across historical fiscal performances remains. Similarly, increasing the weight of fiscal balance in the CFI to 0.6 strengthens the size of the effect of oil price volatility on the overall fiscal health but not its direction and significance of estimates. These findings indicate that these unwanted effects of oil price shocks on fiscal performance, and high persistence in fiscal policy, are robust to different lag lengths and alternative measures of fiscal performance. Overall, robustness analysis supports the stability of baseline PVAR estimates and validates the policy implication that oil-dependent nation fiscal policy must be strictly monitored to dampen the impact of volatile oil prices Table 4.

Table 4.

Robustness checks Tests.

5. Interpretation of PVAR Results

The findings of the PVAR estimation show that oil price volatility (OPV) has a negative impact on fiscal outcomes. More precisely, increased oil price volatility slightly lowers government spending (−0.08 *) and considerably worsens the fiscal balance (−0.11 **), capturing the sensitivity of oil-dependent economies to external shocks. The Composite Fiscal Index (CFI), which measures aggregate fiscal health by combining the government expenditure and fiscal balance, also declines with volatility of oil prices (−0.13 **), as it captures general fiscal insecurity. Fiscal performances are extremely persistent since the government expenditure lag one period (0.30 ***), fiscal balance lag one period (0.28 ***), and CFI lag one period (0.32 ***) all positively affect their current values since past fiscal choices matter substantially for the current fiscal condition.

In addition, fiscal balance and government spending have weak positive responses to each other (0.12 * and 0.10 *, respectively), and fiscal balance positively affects CFI (0.20 **), which indicates interdependence among fiscal policy measures. Overall, while government spending is relatively robust, fiscal balance and overall fiscal health are highly vulnerable to instability in oil prices, indicating the necessity of counter-cyclical fiscal policy and stabilization instruments for ensuring economic stability Table 5.

Table 5.

PVAR Estimation Results.

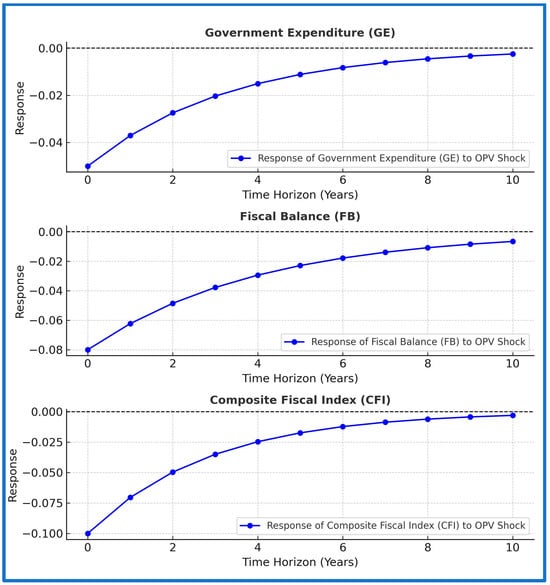

Figure 6 plots the dynamic responses of the main fiscal variables—government spending (GE), fiscal balance (FB), and composite fiscal index (CFI)—to a one-standard-deviation positive oil price volatility shock (OPV). The evidence presents a pronounced and uniform negative response in all the fiscal indicators, which reflects the vulnerabilities of the GCC fiscal systems to the fortunes of oil markets.

Figure 6.

Impulse Responses Function. Sources: (Computed by Eviews 13).

Government spending declines temporarily in response to an oil volatility shock, troughing in the initial few periods before slowly converging to its steady state. This implies that GCC governments generally respond with a prudent, contractionary policy when they sense they have more uncertainty about the oil market and cut or defer expenditure commitments in an effort to be financially sustainable. Concurrently, aggregate fiscal balance undergoes a sudden short-run contraction based on the short-run fiscal cost triggered by revenue volatility and pro-cyclicality of expenditure behavior in oil economies. As time elapses, the adverse impact lessens, suggesting sluggish adjustment mechanisms—such as dipping into the reserves or cutting back on expenditures—working toward equilibrium restore.

The aggregate fiscal index, which aggregates expenditure and fiscal balance elements, manifests the most negative and most long-lasting reaction, substantiating that aggregate fiscal health significantly deteriorates following oil shocks. The long-lasting decline confirms the lasting impacts of oil volatility on finance sustainability. Together, the IRFs underscore the asymmetric and persistent nature of oil shocks within the GCC and reiterate the importance of countercyclical fiscal institutions, diversified revenue bases, and more efficient stabilization mechanisms to insulate public finances against external volatility.

6. Discussion of Heterogeneity Among GCC Countries

More focused examination of country-level estimates reveals considerable heterogeneity among the fiscal responses of GCC countries to oil price shocks. The estimated fiscal reaction functions for Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait reveal that the magnitude and persistence of the fiscal adjustments differ considerably across these countries. Saudi Arabia’s budget responds less quickly and asymmetrically to oil price shocks in keeping with its higher reliance on hydrocarbon revenues and relatively delayed fiscal consolidation mechanisms. In contrast, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait enjoy faster and more symmetric responses based on broader non-oil revenue bases, larger sovereign wealth funds, and more formalized fiscal rules enabling automatic stabilization.

In times of high volatility such as 2008–2009, 2014–2016, and 2020, the divergence between nations is even more apparent. Saudi Arabia and Oman are procyclically inclined more because expenditure remains higher during price booms but falls sharply following busts. The UAE and Qatar, on the other hand, are more resilient from a fiscal perspective with expenditure being more stable and fiscal buffers mitigating the impacts of oil shocks. Bahrain’s response is captured by higher volatility and lower adjustment capacity, consistent with its tighter fiscal space as well as dependence on foreign financing.

These trends highlight that fiscal heterogeneity in the GCC is based on structural and institutional differences, including (i) size and sophistication of sovereign wealth funds’ governments, (ii) enforcement of budget rules and restrictions on expenditure, (iii) progress in diversification of the economy, and (iv) financial transparency and bureaucratic expertise. In combination, all these findings underscore that an identical regional fiscal policy structure will not function. Instead, policymaking requires to be country-specific, with fiscal strategies needing to be fashioned specifically to the structural characteristics and mechanisms of adjustment for individual nations to render adjustment towards oil price cycles sustainable.

7. Policy Recommendation

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need for GCC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, to adopt fiscal policies that create resilience against oil price volatility and long-term sustainability. Several policy interventions are a priority. To start with, strengthening fiscal rules and adopting medium-term expenditure frameworks would reduce procyclicality and improve fiscal predictability. Clear rules on spending and borrowing can also underpin credibility and investor confidence. Second, accelerating revenue diversification remains imperative. Enhancing the role of non-oil taxes, such as VAT and excise taxes, and expanding non-hydrocarbon activities, such as tourism, renewable energy, and knowledge-based industries, can reduce excessive dependence on unpredictable oil revenues.

The findings of this study, particularly the significant negative impact of oil price volatility on fiscal balances and the persistent nature of fiscal policy, underscore the urgent need for GCC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, to adopt fiscal policies that create resilience against oil price volatility and long-term sustainability. Several policy interventions are a priority. To start with, strengthening fiscal rules and adopting medium-term expenditure frameworks would reduce procyclicality and improve fiscal predictability, directly addressing the high persistence of fiscal variables identified in our PVAR model. Second, accelerating revenue diversification remains imperative. The finding that more diversified economies like the UAE show greater resilience underscores the importance of enhancing the role of non-oil taxes, such as VAT and excise taxes, and expanding non-hydrocarbon activities.

Third, stabilization mechanisms such as sovereign wealth funds must be more systematically integrated into fiscal frameworks with well-defined saving and withdrawal rules to insulate budgets from commodity cycles, thereby mitigating the negative impact of OPV shocks identified in our results. Fourth, it is important to enhance the efficiency of government expenditure. Rationalizing subsidies and recurrent spending and allocating resources towards infrastructure, education, and innovation would support long-term growth opportunities. Finally, in light of the global energy transition, aligning fiscal strategies with decarbonization goals through green investments and sustainable financing instruments will be critical to ensuring long-term fiscal stability in a post-oil world.

Finally, institutional reforms are needed to strengthen fiscal transparency, modernize budgetary institutions, and foster coordination between monetary and fiscal authorities. In the long term, aligning fiscal strategies with global energy transition targets through green investments and sustainable financing instruments will be critical to ensuring fiscal stability in a post-oil world. Together, these steps can help GCC economies build stronger fiscal buffers, reduce vulnerability to oil price cycles, and underpin the broader objectives of sustainable development.

8. Conclusions

This study used a Panel Vector Autoregression (PVAR) approach to investigate the interactive link between oil price volatility and the budgetary policies of Saudi Arabia and other GCC nations between 2000 and 2024. Our key contribution lies in providing a direct, dynamic comparison using a long and updated dataset, revealing significant heterogeneity in fiscal responses. The findings demonstrate the GCC economies’ continued reliance on hydrocarbon revenues in spite of continuous diversification initiatives, confirming the strong sensitivity of government spending and fiscal balances to shocks in the price of oil. While comparatively more diversified economies like the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait show superior fiscal consolidation mechanisms, Saudi Arabia, the largest oil exporter in the GCC, continues to show poorer budget adjustment to negative shocks. The Impulse Response Functions further illustrated that the negative effects of an oil volatility shock on the fiscal balance are both immediate and persistent.

These findings imply that despite progress, existing fiscal buffers and reforms are insufficient to fully insulate GCC budgets from oil market turmoil. Therefore, the policy imperative remains to deepen structural reforms, strengthen institutional frameworks, and accelerate diversification. Future research could build on this work by incorporating high-frequency data, exploring the asymmetric effects of oil price increases versus decreases, and employing alternative methods, such as PCA, to refine composite fiscal indicators.

In contrast to economies that are somewhat more diversified, such the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the region’s largest oil exporter, continues to show more delayed budgetary reflexes to unfavorable shocks. The results highlight the diversity of budgetary responses throughout the GCC and the role that institutional frameworks play in regulating adjustment dynamics.

The data also demonstrates how the volatility of oil prices swiftly affects fiscal balances, increasing macroeconomic volatility and making budgetary planning more difficult. The risks of external oil market shocks cannot yet be completely mitigated by sovereign wealth funds and recent fiscal measures like the implementation of the Value Added Tax and diversification of public investments, even though these have strengthened fiscal resilience to some extent. Therefore, the findings highlight the necessity for GCC authorities to tighten fiscal regulations and stabilization measures, diversify non-oil revenue sources, expedite fiscal reforms, and increase the efficiency of expenditures.

Overall, by offering comparative, panel-based information on GCC budgetary adjustment processes with both academic and practical consequences, the research adds to the body of literature. Although oil revenues will continue to dominate the economy in the foreseeable future, sustainable fiscal management necessitates consistent advancements in institutionalization, diversification, and alignment with the global energy transition. This presents a clear policy challenge. Only by taking these actions will the GCC nations be able to strengthen their fiscal stability, reduce their vulnerability to fluctuations in the price of oil, and guarantee long-term economic stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S. and H.M.; methodology, T.S.; software, H.M. and T.S.; validation, H.M., T.S., H.M. and T.S.; formal analysis, T.S., H.M., T.S. and T.S.; investigation, T.S. and H.M.; resources, T.S. and H.M.; data curation, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M. and T.S.; writing—review and editing, H.M. and T.S.; visualization, H.M. supervision, T.S. and H.M.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Data Availability Statement

All data employed in this work have been obtained from public sources as shown in the list of references. Data are available on request from author: tsadrawi@imamu.edu.sa.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Saudi Arabia, for their support of this study. The researcher also appreciates the considerable time and work of the reviewers and the editor to expedite the process. Their commitment and expertise were crucial in making this work a success. I appreciate your unwavering help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abdelkawy, H., & Al Shammre, F. (2024). The oil price shocks and the monetary stability in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 51(4), 789–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Moneef, M., & Hasanov, F. (2020). Fiscal multipliers in Saudi Arabia (IMF Working Paper No. 20/20). International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/fiscal-multipliers-for-saudi-arabia-revisited-4yjygpudjr.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Arezki, R., & Bruckner, M. (2011). Oil rents, corruption, and state stability: Evidence from panel data regressions. Energy Economics, 37, 113–123. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0014292111000316 (accessed on 23 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Aysan, A. F., Disli, M., & Ozturk, H. (2019). Sovereign wealth funds, governance, and fiscal policy frameworks: Evidence from oil-exporting countries. IMF Working Papers. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2023/133/article-A001-en.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Baumeister, C. (2023). Pandemic, war, inflation: Oil markets at a crossroads? NBER Working Paper No. 31496 July 2023 JEL No. E31,E58,Q41,Q43. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31496/w31496.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2014). Soaring of the gulf falcons: Diversification in the GCC oil exporters in seven propositions. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Soaring-of-the-Gulf-Falcons-Diversification-in-the-GCC-Oil-Exporters-in-Seven-Propositions-42365 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Cherif, R., Hasanov, F., & Pande, A. (2023). Oil, volatility, and fiscal adjustment: Lessons for the GCC (IMF Working Paper No. 23/147). Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/DP/2020/English/FOFSGCCEA.ashx (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Espinoza, R. A., & Senhadji, A. (2011). Oil price shocks and fiscal policy in the GCC countries (IMF Working Paper No. 11/28). International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2017/wp17287.ashx (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Fasano, U., & Wang, Q. (2002). Testing the relationship between government spending and revenue: Evidence from GCC countries (IMF Working Paper No. 02/201). Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp02201.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Hamilton, J. D. (1983). Oil and the macroeconomy since World War II. Journal of Political Economy, 91(2), 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz-Eakin, D., Newey, W., & Rosen, H. S. (1988). Estimating vector autoregressions with panel data. Econometrica, 56(6), 1371–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023). World energy outlook 2023. OECD/IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Saudi Arabia: 2024 article IV consultation—Staff report. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Love, I., & Zicchino, L. (2006). Financial development and dynamic investment behavior: Evidence from panel VAR. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 46(2), 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). (2023). Economic outlook for the Middle East and North Africa. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-outlook/volume-2023/issue-2_7a5f73ce-en.html (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1995). Natural resource abundance and economic growth (NBER Working Paper No. 5398). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Ministry of Finance. (2024). Budget statement for fiscal year 2024. Government of Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.mof.gov.sa/en/budget/2024/Documents/Bud-E%202024%20F4.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Villafuerte, M., & Lopez-Murphy, P. (2010). Fiscal policy in oil producing countries during the recent oil price cycle (IMF Working Paper No. 10/28). International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2025). GCC economic outlook: Growth on the rise, but smart spending will shape the future. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/06/19/gcc-growth-on-the-rise-but-smart-spending-will-shape-a-thriving-future (accessed on 14 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).