Abstract

This study re-evaluates ROC-AUC for binary classification under severe class imbalance (<3% positives). Despite its widespread use, ROC-AUC can mask operationally salient differences among classifiers when the costs of false positives and false negatives are asymmetric. Using three benchmarks, credit-card fraud detection (0.17%), yeast protein localization (1.35%), and ozone level detection (2.9%), we compare ROC-AUC with Matthews Correlation Coefficient, F2-score, H-measure, and PR-AUC. Our empirical analyses span 20 classifier–sampler configurations per dataset, combined with four classifiers (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, and CatBoost) and four oversampling methods plus a no-resampling baseline (no resampling, SMOTE, Borderline-SMOTE, SVM-SMOTE, ADASYN). ROC-AUC exhibits pronounced ceiling effects, yielding high scores even for underperforming models. In contrast, MCC and F2 align more closely with deployment-relevant costs and achieve the highest Kendall’s τ rank concordance across datasets; PR-AUC provides threshold-independent ranking, and H-measure integrates cost sensitivity. We quantify uncertainty and differences using stratified bootstrap confidence intervals, DeLong’s test for ROC-AUC, and Friedman–Nemenyi critical-difference diagrams, which collectively underscore the limited discriminative value of ROC-AUC in rare-event settings. The findings recommend a shift to a multi-metric evaluation framework: ROC-AUC should not be used as the primary metric in ultra-imbalanced settings; instead, MCC and F2 are recommended as primary indicators, supplemented by PR-AUC and H-measure where ranking granularity and principled cost integration are required. This evidence encourages researchers and practitioners to move beyond sole reliance on ROC-AUC when evaluating classifiers in highly imbalanced data.

Keywords:

SMOTE; ADASYN; H-measure; MCC; PR-AUC; ROC-AUC; XGBoost; CatBoost; random forest; logistic regression 1. Introduction

Rare-event binary classification remains a significant challenge across various domains, including but not limited to fraud detection, bioinformatics, environmental monitoring, cybersecurity, medical diagnosis, manufacturing fault detection, and autonomous systems. In these settings, the positive class typically constitutes a small fraction of the data, making accurate detection both technically difficult and operationally critical. Standard tools for model evaluation, particularly Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC), often yield inflated assessments due to their insensitivity to class imbalance and asymmetric error costs. At the same time, several studies argue that ROC-AUC remains statistically robust to class imbalance and provides a stable, threshold-independent ranking measure, motivating ongoing debate rather than a settled consensus. As machine learning systems become integral to decision-making in high-stakes, real-world environments, it is essential to critically evaluate both the data preprocessing methods and performance metrics used in model assessment. This study presents a comprehensive, metric-centered investigation of classifier evaluation under highly imbalanced data conditions, focusing on resampling strategies and the behavior of metrics. Despite extensive discussion of performance metrics for imbalanced classification, existing studies typically focus on advocating individual alternatives to the ROC-AUC or provide conceptual arguments without a unified empirical protocol. As a result, a lack of statistically rigorous, cross-domain evaluation remains, which jointly examines how different metric families behave and potentially disagree under ultra-imbalanced prevalence and realistic resampling pipelines. This unresolved debate regarding whether the ranking robustness of ROC-AUC outweighs the prevalence sensitivity of PR-AUC directly motivates this study. Specifically, we investigate how different metric families behave, diverge, and ultimately influence model selection under ultra-imbalanced conditions. Accordingly, our analysis tests the hypothesis that no single metric is sufficient in rare-event settings, and that complementary, cost-aware metrics are required for reliable evaluation. The subsections below provide background on the methodological foundations that guide our analysis.

1.1. Resampling Strategies in Imbalanced Data

When the minority-class prior satisfies 1,

empirical risk minimization with a symmetric loss favors the majority class [1]. One approach is resampling, i.e., constructing a training set whose posterior prior

is closer to 0.5. Let

,

denote the counts of minority (class 1) and majority (class 0) instances, and let

be an oversampling factor applied to the minority class. After oversampling, the adjusted prior is given by Equation (2):

when

satisfies 2, the resulting training set achieves a target prior

that is closer to 0.5.

A perfectly balanced set, therefore, corresponds to

. The subsections below summarize the major families of resampling and highlight their theoretical motivations. Random undersampling, which involves randomly discarding the majority of instances, reduces

to

≈ 0.5 [2]. While computationally attractive, this approach may eliminate informative majority examples and increase the variance of the estimator. Ensemble variants, such as EasyEnsemble and BalanceCascade [3], mitigate this issue by building multiple classifiers on independently undersampled subsets and aggregating their predictions. Random oversampling, which replicates minority observations to achieve the desired ratio, is unbiased in expectation; however, it can result in exact duplicate rows, leading to overfitting [4]. The expected Bayes risk decreases only if the learner regularizes against memorization. To avoid duplication, synthetic minority over-sampling generates artificial instances according to Equation (3):

where

is a minority point and

one of its k minority nearest neighbors [5]. Extensions refine the neighborhood criterion:

- Borderline-SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) focuses on minority instances whose nearest neighbors are predominantly from the majority class, thereby increasing density near the decision boundary [6].

- SVM-SMOTE, a Support Vector Machine-based extension of SMOTE, generates synthetic samples near the decision boundary using support vectors identified by the classifier [7].

- Safe-Level-SMOTE assigns a safety level defined in Equation (4):and chooses the interpolation factor λ so that the synthetic point lies closer to the parent with a higher safe-level score to avoid generating samples in dangerous regions [8].

- ADASYN (Adaptive Synthetic Sampling) adaptively varies the number of synthetic samples per minority point according to the local imbalance ratio defined in Equation (5):

Combining oversampling with Tomek links deletion [10] or Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN) [11] removes the majority of points lying within the minority manifold, reducing class overlap [12]. Empirically, SMOTE + ENN often yields smoother decision surfaces than either step alone [13].

Density-aware and generative approaches employ information-theoretic or generative criteria. Gaussian-SMOTE (G-SMOTE) replaces linear interpolation with a Gaussian mixture model of the minority class [14], while Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based over-samplers learn

implicitly via adversarial training [15]. Theoretical analyses show that, under a Lipschitz assumption on the Bayes decision boundary, synthetic samples drawn from a contiguous minority manifold can reduce the upper bound on the classification error by tightening the margin [16].

1.2. Performance Metrics in Binary Classification

Let the confusion matrix for a binary classifier at threshold

be as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Confusion matrix for a binary classifier.

Any scalar score reduces this 2 × 2 matrix, or in threshold-free form, the ranking of class scores s(), to a single real number. The following subsections review the principal families of metrics, their mathematical properties, and known limitations.

1.2.1. Threshold-Independent Discrimination

The receiver-operating-characteristic area (ROC-AUC) is defined in Equation (6):

where

,

are the score distributions for positives and negatives [17,18]. ROC-AUC is equivalent to the Mann–Whitney

statistic and is invariant under strictly monotone score transformations. Its major weakness is class-imbalance insensitivity: when

(), significant changes in FP translate into tiny variations in the false-positive rate (FPR) [19]. Consider a binary classifier that assigns each instance a score

and applies a threshold

to decide between positive and negative. The two axes of its ROC curve are defined in Equation (7):

In many practical settings, the number of positive cases

is vanishingly small compared to negatives

. In that extreme imbalance, the false positive rate denominator is effective

, so even a significant absolute change in FP produces only a barely perceptible shift in the ROC curve.

This distortion carries over to the AUC itself. Equivalently expressed as Equation (8):

the statistic is overwhelmed by comparisons among the abundant negative–negative pairs. As long as a model avoids egregious score inversions, moderate numbers of false alarms or misses scarcely register in AUC. The upshot is that, under severe imbalance, nearly any non-degenerate classifier achieves an ROC-AUC in the 0.90–0.99 range, obscuring the errors that drive operational cost. By treating false positives and false negatives (FN) symmetrically, ROC-AUC “wins” without ever “paying” for the mistakes that, in domains like fraud or medical diagnosis, are most consequential. Replacing the x-axis with recall yields the precision–recall (PR) curve; its area, defined in Equation (9), is given by

has a baseline equal to the minority prevalence

. Davis and Goadrich [20] prove that Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve (PR-AUC) is strictly more informative than ROC-AUC when

is small.

In a similar effort, the H-measure [21] is a coherent alternative to the area under the ROC curve that explicitly incorporates the relative cost of false positives and false negatives via a user-specified distribution over misclassification cost-ratios. Rather than treating all operating points equally, the H-measure defines a weighting density

on the cost-ratio

and computes the expected misclassification loss as defined in Equation (10):

where

and

are the class priors, and

is the threshold minimizing the cost for a given

. By default, one chooses

to be the

density, yielding a neutral prior that neither over- nor under-emphasizes extreme cost ratios. The H-measure is then normalized by the worst-possible expected loss under the same density, producing a summary score in [0, 1] as shown in Equation (11):

In contrast to ROC-AUC, which is dominated by the vast number of negative–negative score-pair comparisons under severe imbalance and therefore remains artificially high even when a classifier makes many costly errors, the H-measure penalizes errors proportionally to their operational importance. In highly skewed scenarios (e.g., fraud detection, rare-disease screening), it provides a more discriminating evaluation: classifiers that sacrifice minority-class sensitivity or incur excessive false alarms receive a substantially lower H-measure, whereas the ROC-AUC remains saturated.

1.2.2. Single-Threshold Confusion-Matrix Scores

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and the Fβ score are two widely used scalars. The MCC, defined in Equation (12), is computed as

and ranges within [−1, 1] [22].

MCC is a special case of Pearson’s

between prediction and truth. MCC treats both classes symmetrically and remains well defined even when one row or column is small [23].

The

score, defined in Equation (13), is expressed as

where

and

denote precision and recall, respectively [24].

Unlike MCC,

ignores true negatives; it is therefore sensitive to prevalence and may exaggerate performance in dense negative regions [25]. An alternative that explicitly accounts for prevalence is balanced accuracy, defined in Equation (14):

which has been recently advocated for class-imbalance evaluation [26].

Another related metric, Cohen’s κ (kappa), is a chance-corrected measure of agreement that quantifies how much better a classifier’s predictions agree with the true labels than would be expected by random chance [27]. For a two-category problem, let the observed and expected agreements be defined in Equations (15) and (16), respectively:

and

where

and

are the counts of predicted and true instances in class

. Cohen’s

is then computed as shown in Equation (17):

which ranges from −1 (complete disagreement) through 0 (no better than chance) to 1 (perfect agreement).

Unlike raw accuracy, κ corrects for any agreement that would arise simply from the marginal class frequencies, which is an important feature when classes are highly imbalanced. In such settings, a naive classifier can achieve high accuracy (and thus high

) by always predicting the majority class, yet its κ will remain low because

is large. Interpretive benchmarks [28] suggest that κ < 0.00 indicates “poor” agreement, 0.00–0.20 “slight,” 0.21–0.40 “fair,” 0.41–0.60 “moderate,” 0.61–0.80 “substantial,” and >0.80 “almost perfect.”

Cohen’s κ was deliberately excluded from our evaluation because it offers little independent information beyond existing metrics based on the confusion matrix in the context of extreme class imbalance. Our study employs the F2 score to capture threshold-specific recall-weighted performance, the MCC for chance-corrected balance, ROC-AUC and PR-AUC for threshold-agnostic discrimination, and the H-measure for cost-sensitive integration. Since κ and MCC both correct for class-marginal effects and in practice produce virtually identical classifier rankings on ultra-skewed data, including κ would have been redundant and risked obscuring the clarity of our comparative analysis.

1.2.3. Contribution of the Study

Prior work has highlighted metric pitfalls in imbalanced learning [19,23,29], arguing that PR-AUC is more informative than ROC on skewed data and that MCC is preferable to accuracy and F1; some even propose replacing ROC-AUC outright with MCC. Yet, we still lack a statistically rigorous, cross-domain comparison of ROC-AUC against MCC, F2, PR-AUC, and the H-measure under ultra-imbalanced prevalence and realistic resampling pipelines. Saito and Rehmsmeier [19] focus on PRC vs. ROC in imbalance but do not examine MCC or H-measure or analyze sampler–classifier pipelines. Chicco and Jurman [23] advocate MCC over accuracy and F1 but do not position MCC against ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, and H-measure in rare-event scenarios or under resampling. Chicco and Jurman [29] argue that the MCC vs. ROC-AUC conceptually, without providing an empirical, multi-metric treatment that combines rare-event settings, resampling, and statistical testing. Accordingly, our contribution departs from prior MCC-centered analyses by formalizing a prescriptive, statistically validated multi-metric evaluation protocol rather than advocating a single replacement metric. Meanwhile, Richardson et al. [30] reopen the debate by contending that ROC-AUC remains robust under imbalance while PR-AUC is prevalence-sensitive, an observation that, rather than endorsing a single “best” metric, motivates a multi-metric protocol that separates ranking from cost and thresholding. In response, we present a multi-metric, cost-aligned package that combines MCC and F2 as primary threshold-dependent metrics with PR-AUC for threshold-free ranking and the H-measure for principled cost integration. This framework is evaluated in ultra-imbalanced (<3%) regimes across resampling pipelines and supported by bootstrap confidence intervals, DeLong’s tests, Kendall’s τ, and Friedman–Nemenyi analyses. We also include a prevalence-sensitivity check, showing how shifts in class balance affect PR-AUC and the H-measure on our datasets, which reinforces the need to report complementary metrics rather than relying on ROC-AUC alone.

The proposed multi-metric protocol is a prescriptive evaluation framework rather than an informal guideline. It specifies explicit decision rules: MCC and F2 serve as primary metrics for thresholded, cost-asymmetric deployment; PR-AUC assesses threshold-free ranking; and the H-measure integrates cost assumptions explicitly. Model selection is accepted only when supported by rank concordance (Kendall’s τ) and statistical significance testing, preventing decisions based on isolated metric improvements. Empirically, we demonstrate that this protocol yields distinct and operationally superior model choices compared to conventional ROC-AUC-centric reporting.

Importantly, the novelty of this work lies not in proposing new metrics but in establishing a unified, statistically rigorous evaluation protocol that jointly analyzes metric disagreement, cost alignment, and resampling effects under ultra-imbalanced conditions, an aspect largely absent from prior imbalanced-learning studies.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has combined cross-domain rare-event datasets, multiple resampling strategies, and formal rank- and significance-based comparisons to assess how different metric families can lead to contradictory model-selection conclusions.

To address this gap, we conduct a cross-domain analysis of 20 classifier-sampler configurations per dataset. Specifically, we evaluate four classifiers, Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and CatBoost (CB), combined with five sampling strategies, namely no oversampling, SMOTE, Borderline SMOTE, SVM SMOTE, and ADASYN. The analysis is performed on three rare event benchmarks: credit-card fraud detection with 0.17% positives, yeast protein localization with 1.35% positives, and ozone exceedance with approximately 3% positives.

Our contributions are fourfold:

- Empirical characterization of ROC-AUC in rare-event regimes. We quantify ceiling effects and demonstrate that ROC-AUC can overstate model quality, as it remains relatively insensitive to operationally costly misclassifications when the prevalence is less than 3%, even as false positives and false negatives vary substantially across pipelines.

- A pragmatic, cost-aware multi-metric alternative. Using Kendall’s τ rankings and paired significance testing, we demonstrate that MCC and F2 more accurately reflect asymmetric error costs and deployment priorities. In contrast, PR-AUC (threshold-free ranking) and the H-measure (principled cost weighting) provide complementary views. We distill this into a portable reporting protocol: use MCC and F2 as primary metrics, with PR-AUC and H-measure as complementary metrics; report ROC-AUC only with explicit caveats in ultra-imbalanced settings. Specifically, MCC and F2 are prioritized when deployment involves fixed decision thresholds and asymmetric error costs; candidate models are compared at operationally relevant thresholds using these metrics, with selections accepted only when supported by rank consistency and statistical significance. In practice, metric prioritization within the protocol should reflect domain-specific risk asymmetries: F2 is emphasized when false negatives are substantially more costly than false positives (e.g., safety or fraud detection), whereas MCC provides a balanced summary when both error types matter under constrained review capacity. The deployment context, such as real-time decision-making versus offline triage, should guide threshold selection rather than relying on metric substitution.

- Statistically rigorous, resampling-aware evaluation. We pair model selection with robust inference using stratified bootstrap confidence intervals, DeLong’s tests for ROC-AUC, Kendall’s τ for rank concordance, and Friedman–Nemenyi critical-difference analysis, to reveal practically meaningful differences that ROC-AUC alone can mask.

- Actionable guidance for practitioners and researchers. We provide a replicable framework for evaluating classifiers under extreme class imbalance that integrates threshold-dependent (MCC and F2) and threshold-free (PR-AUC and H-measure) metrics, aligns with stakeholder cost asymmetries, and transfers across domains (finance, bioinformatics, environmental monitoring).

These contributions move beyond single-metric advocacy toward a multi-metric, cost-aligned evaluation protocol empirically validated in ultra-imbalanced, real-world scenarios.

2. Related Work

A quantitative comparison of performance metrics has attracted sustained interest because the choice of metric can significantly alter scientific conclusions and deployment decisions. Early empirical surveys [31,32] cataloged divergences among accuracy, ROC-based, and cost-based criteria, noting that overall accuracy, defined in Equation (18),

is dominated by the majority class when

.

For instance, Hanley and McNeil [17] justified ROC-AUC as the probability that a randomly chosen positive receives a higher score than a randomly chosen negative. However, Hand [21] demonstrated that AUC implicitly assigns unequal, prevalence-dependent misclassification costs, which violates many decision contexts. Building on that critique, Davis and Goadrich [20] derived the monotone transformation that maps any ROC point (FPR, TPR) to (R, P) space and proved that the PR curve dominates ROC when

. Saito and Rehmsmeier [19] confirmed the theoretical claim using biomedical data, where the ROC-AUC varied by less than 0.02, while the PR-AUC varied by more than 0.50 for the same algorithms. Very recent work has reopened the debate. Richardson et al. [30] contend, via simulation and an epitope-prediction case study, that ROC-AUC remains robust to imbalance, whereas PR-AUC “over-penalizes” legitimate classifiers. Their critique hinges on the fact that precision is a function of both TPR and prevalence, making PR-AUC sensitive to the sampling of the evaluation set. Conversely, Zhang and Geng [33] demonstrate that PR-AUC’s prevalence sensitivity is a feature, not a bug, when the deployment environment shares the same class skew. The persisting disagreement underscores the need for multi-metric reporting.

The MCC was initially proposed for protein secondary-structure prediction [22]. Chicco and Jurman [23] provided simulations and genomics case studies where MCC ranked classifiers more consistently with domain utility than F1 or balanced accuracy. In 2023, these authors argued that MCC should replace ROC-AUC as the “standard statistic” for binary classification, citing ROC’s hidden cost bias and MCC’s symmetry. Itaya et al. [34] derived asymptotic confidence intervals for single and paired MCC estimates, enabling formal hypothesis testing between classifiers.

Elkan [1] formalized expected cost (EC) as shown in Equation (19):

arguing that threshold choice must minimize EC under a user-supplied cost matrix. Hernández-Orallo [35] extended ROC analysis to dominance curves, constructing the convex hull of cost points to identify potentially optimal classifiers under all cost/prevalence pairs. Hand [36] proposed the H-measure, which integrates EC over a beta-distributed cost parameter to mitigate the AUC’s hidden-cost flaw. While discrimination metrics assess ranking, Niculescu-Mizil and Caruana [37] compared log-loss, defined in Equation (20), with the Brier score and AUC, showing that well-calibrated probabilities can be critical for cost-sensitive decisions even when AUC values are identical:

Flach and Kull [38] further decomposed log-loss into calibration and refinement components, providing diagnostic insight complementary to ROC analysis. He and Garcia [39] reviewed algorithmic and evaluation issues in imbalanced learning, recommending PR-AUC and G-mean. More recently, Blagus and Lusa [40] demonstrated that

with β > 1 is preferable to F1 for rare disease prediction, and Imani et al. [41,42] examined how varying class-imbalance ratios affect classifier performance and the apparent efficacy of resampling (e.g., SMOTE and its variants), evaluating both threshold-dependent and threshold-free metrics, including ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, MCC, F1-score, and Cohen’s κ. Complementing these findings, a comprehensive review of churn prediction reports that the ROC-AUC remains one of the most commonly reported metrics in practice, reflecting established reporting conventions in the literature [43]. This persistence motivates providing clearer guidance on metric selection in the context of class imbalance.

3. Datasets

This study evaluates classifier performance on three publicly available benchmark datasets that exhibit extreme class imbalance (see Table 2). The datasets are all real-world operational datasets commonly used as benchmarks in imbalanced learning research. Importantly, they span three orders of magnitude in minority-class prevalence (0.17%, 1.35%, and approximately 3%), enabling a controlled examination of metric behavior across varying degrees of extreme imbalance. Before modeling, all features were standardized to have a zero mean and unit variance. As is common in many operational settings, no instance-level cost annotations were available. Details of each dataset are provided in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

Table 2.

Overview of datasets used in the study.

- European Credit-card Fraud Detection: This widely studied dataset comprises 284,807 card-transaction records, of which 492 are confirmed frauds (imbalance rate ≈ 0.17%). Each observation is represented by 28 principal components derived from the original monetary attributes.

- UCI Yeast Protein Localization (“POX”): The UCI Yeast benchmark contains 1484 protein sequences described by eight physicochemical descriptors. The minority class “POX” (indicating peroxisomal localization) appears in only 20 instances (≈1.35%).

- UCI Ozone Level Detection: This dataset consists of 2536 hourly measurements of atmospheric conditions, each with 73 features, and 57 recorded ozone-exceedance events (≈3%).

3.1. Fraud Dataset (Credit-Card Fraud Detection)

The Credit-Card Fraud Detection dataset comprises 284,807 credit-card transactions made by European cardholders over a two-day period in September 2013 [43]. Only 492 transactions are labeled as fraudulent, representing approximately 0.17% of the data. Each record consists of 31 features: 28 anonymized principal components (V1–V28), obtained via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to preserve confidentiality, a “Time” feature (seconds elapsed since the first transaction), and an “Amount” feature (transaction value in Euros). The target column “Class” takes the value 0 for legitimate transactions and 1 for fraud. Because PCA was used to mask the original feature identities, V1–V28 do not have explicit semantic meaning; nevertheless, they capture the essential structure that distinguishes fraudulent from legitimate activity [44]. The extreme rarity of fraud events underscores why this dataset is a standard benchmark in imbalanced-learning research [19].

3.2. Yeast Dataset (UCI Version; POX Subset)

The Yeast dataset is available from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [45]. Initially, each of the 1484 instances and 11 features describes characteristics of proteins via eight continuous features and a single “Localization” label that can take one of ten categories (CYT, NUC, MIT, ME1, ME2, ME3, EXC, VAC, POX, ERL). Of particular interest is the POX class, which appears only 20 times (≈1.35%) out of 1484 instances [45]. Since the UCI version encodes localization as a single categorical field, we extract the POX cases and recode them as the positive class (1), with all other localizations merged into a single negative class (0). This one-versus-all transformation yields a binary problem with POX representing 1.35% of instances and therefore serving as a rare-class benchmark in line with prior literature [47].

3.3. Ozone Dataset

The one-hour ozone exceedance dataset originates from the UCI Machine Learning Repository’s Air Quality Evaluation collection [46], which captures 2536 timed atmospheric chemistry and meteorology observations recorded at an urban monitoring station in California across multiple summer seasons. Each record includes a suite of 73 continuous features, such as temperature, barometric pressure, wind speed, relative humidity, and concentrations of nitrogen oxides (NOx), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and volatile organic compounds, paired with a binary target indicating whether the one-hour average ozone (O3) concentration exceeded the regulatory threshold of 0.08 ppm.

Following preprocessing, entries with missing values are discarded, and the original timestamp column is removed to focus purely on predictive measurements. To conform with prevalent imbalance-learning benchmarks, a literature-standard split retains all 57 confirmed class 1 instances and randomly selects the corresponding 1791 class 0 instances, producing an extreme imbalance ratio of 31.4:1. Before model training, all features are standardized to zero mean and unit variance, and the data are partitioned into stratified training and testing subsets that preserve the native class proportions. The pronounced skew toward non-exceedance cases highlights the challenges of predicting rare events. This dataset is particularly suitable for evaluating sampling techniques, ensemble methods, and cost-sensitive learning algorithms.

3.4. Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing was conducted uniformly across all three datasets to facilitate fair comparison under severe class imbalance. To prevent label leakage, the target label was excluded from the test set’s feature matrix for each dataset. All preprocessing and resampling steps were fitted on the training split only, and the resulting fitted preprocessors (e.g., scalers, encoders) were then applied to the test features; no statistics were re-estimated on the test data, and the test labels were used solely for final evaluation. In the Credit-Card Fraud dataset, the “Time” feature was excluded to avoid confounding with temporal dependence under static resampling. Transaction amounts exhibited extreme right skew and were log-transformed as shown in Equation (21) [48]:

Subsequently, all 29 features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance [49]. A stratified train–test split (70%/30%) preserved the original 0.17 % fraud ratio, with oversampling techniques applied exclusively to the training subset [44].

The multi-class localization labels were recoded into a binary target in the UCI Yeast dataset, as defined in Equation (22), assigning label 1 to the “POX” class and 0 to all other localizations:

This yielded 20 positive and 1464 negative instances (≈1.35%). The eight continuous features were standardized via z-score normalization to ensure equal weighting in distance-based sampling. A stratified train–test split (70%/30%) was performed, maintaining the class ratio in both sets, with oversampling restricted to the training partition [45].

The UCI Ozone Level Detection dataset underwent complete-case analysis, where any record containing missing values was removed, resulting in a sample size reduction from 2536 to 1848 observations. The timestamp column was dropped to prevent non-numeric data from affecting subsequent analyses. A literature-standard subset was constructed by retaining all 57 positive instances and randomly sampling 1791 negatives to achieve an imbalance ratio of 31.4:1. All 73 features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance. Finally, a stratified split (70% training, 30% testing) preserved the class distribution, with oversampling applied solely to the training set.

4. Methods

Our goal was to examine how alternative evaluation metrics behave when the minority class is vanishingly rare and to test whether a small, theory-driven set of metrics can remain intact across disparate application areas. We therefore built a deliberately symmetrical experimental protocol: one script, three datasets, twenty classifier–sampler variants, one set of metrics, and one statistical lens. This section walks through each step. We used ChatGPT (GPT 5.1) solely for improving clarity and grammar during manuscript preparation. No part of the scientific content, data analysis, or conclusions was generated by AI.

4.1. Classifier-Sampling Framework

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.11 using scikit-learn 1.5, imbalanced-learn 0.12, CatBoost 1.3, and XGBoost 2.0. We evaluated four classifiers, logistic regression with L2 regularization, Random Forest with 300 trees, XGBoost with depth = 6 and learning rate η = 0.1, and CatBoost with 500 iterations, each under one baseline (no oversampling) and four oversampling techniques (SMOTE, Borderline-SMOTE, SVM-SMOTE, and ADASYN). This yields

unique classifier–sampler configurations per dataset. We applied these 20 configurations independently to each of the three datasets, for a total of 60 model evaluations.

Performance for each configuration was estimated via stratified 10-fold cross-validation. Oversampling was applied only to the training set within each fold to avoid information leakage. No resampling or parameter fitting was performed on test data. We recorded ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, the H-measure, MCC, F2-score, and the raw confusion-matrix counts from every run.

For threshold-dependent metrics (MCC and F2), predictions are evaluated at fixed, operationally relevant decision thresholds that are held constant across models and folds, rather than optimized per metric or per fold, to reflect realistic deployment conditions. The H-measure is computed using the standard Beta (2, 2) cost distribution, which represents a neutral prior over relative misclassification costs and is commonly used when domain-specific cost information is unavailable. This choice allows cost-aware comparison without imposing asymmetric assumptions that would vary across application domains.

To ensure reproducibility and to avoid implicit optimization bias, all classifiers and resampling methods were configured using standard, literature-consistent hyperparameters, without dataset-specific tuning. The objective of this study is to analyze metric behavior rather than maximize predictive performance.

Logistic Regression employed L2 regularization with the default inverse regularization strength (C = 1.0) and the liblinear solver. Random Forest models were trained using 300 trees, Gini impurity, and the default feature subsampling method. XGBoost used a maximum tree depth of 6, learning rate η = 0.1, and 300 boosting rounds. CatBoost models were trained for 500 iterations with default regularization and symmetric trees.

All resampling techniques were implemented using the imbalanced-learn library with standard parameter settings. SMOTE-based methods employed k = 5 nearest neighbors. Borderline-SMOTE used the “borderline-1” strategy. SVM-SMOTE generated samples near support vectors identified by a linear SVM. ADASYN adaptively generated synthetic samples based on local class imbalance using its default neighborhood size.

4.2. Rank-Correlation Analysis Between Metrics

To quantify how consistently the candidate metrics rank the 20 classifier-sampler configurations, we computed the pair-wise Kendall rank correlation coefficient τ ([50]) for every metric pair

. Let

and

denote the values of metrics

and

for configuration

.

Kendall’s statistic is defined in Equation (23):

and the sign function is given in Equation (24):

The numerator in Equation (23) counts concordant minus discordant configuration pairs, while the denominator represents the total number of unordered pairs. For illustration, when N = 20, Kendall’s statistic reduces to 25:

Kendall’s rank-correlation coefficient (τ) is preferred to the Pearson product-moment coefficient () for assessing agreement among evaluation metrics in highly imbalanced learning because it aligns with the methodological aim, which is comparing metric-induced rankings rather than raw magnitudes. Kendall τ is a non-parametric statistic that depends only on the ordering of observations; it remains invariant under any strictly monotone transformation of the metric scores and is therefore insensitive to the heterogeneous, bounded scales of MCC (−1 … 1), PR-AUC (0 … 1), and ROC-AUC (0 … 1) [51]. Unlike

, which assumes joint normality and homoscedasticity, τ makes no distributional assumptions and is robust to the heavy skew, ceiling effects, and frequent ties (e.g., TP = 0, FP = 0 → identical MCC) that characterize rare-event experiments. Furthermore, τ admits an intuitive probabilistic interpretation (τ = 0.60 implies 80% concordant versus 20% discordant pairs), facilitating substantive discussion of metric concordance. These properties render Kendall’s coefficient a statistically reliable and conceptually faithful measure for ranking-consistency studies under extreme class imbalance [50,52].

4.3. Statistical Testing and Confidence Intervals

We generated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each metric using a stratified bootstrap (2000 replicates per test fold, preserving class prevalence). ROC-AUC differences between any two classifier-sampler configurations were evaluated with the paired-sample DeLong test ([53]), and p-values are reported. When comparing more than two methods, we applied the Friedman aligned-ranks test followed by the Nemenyi Critical-Difference (CD) procedure (α = 0.05).

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents a detailed empirical investigation into the performance of twenty classifier–sampler configurations across three highly imbalanced datasets: credit-card fraud detection, Yeast protein localization, and Ozone level detection. Under extreme class imbalance, the primary objective is to examine the sensitivity and reliability of five evaluation metrics: ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, F2-score, MCC, and H-measure. Rather than comparing classifiers per se, the focus lies on understanding how each metric responds to variations in false positives and false negatives induced by different sampling techniques. Results highlight notable inconsistencies in ROC-AUC’s ability to reflect practical performance costs, whereas alternative metrics demonstrate more substantial alignment with operational realities and domain expert expectations.

5.1. Detailed Per-Dataset Results (Fraud Dataset)

This section compares the behavior of twenty classifier–sampler configurations on three datasets that are thematically unrelated yet similarly skewed: the credit-card fraud dataset, the Yeast protein localization dataset, and the Ozone Level Detection dataset.

5.1.1. Fraud Dataset Results

Table 3 presents the results of 20 distinct classifier–sampler configurations, including the corresponding confusion matrix components and five evaluation metrics. All evaluations were conducted on the test set (unseen data) of the Fraud dataset. Since the study’s objective is metric evaluation, not model comparison, we examine how each metric responds to the dramatic swings in FP and FN counts that arise under extreme class-imbalance. The empirical evaluation conducted on the Fraud dataset demonstrates clearly the limitations inherent in relying on ROC-AUC as an evaluation metric for rare-event binary classification tasks. Although ROC-AUC scores across various classifiers and sampling methods remain consistently high, a deeper inspection of the performance using alternative metrics reveals significant shortcomings in ROC-AUC’s reliability for highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 3.

The results on the credit-card fraud dataset.

Taking the Logistic Regression classifier with ADASYN sampling as a notable example, the ROC-AUC score is observed to be impressively high at 0.968. However, this apparently robust performance contrasts with extremely poor values for other critical metrics: an F2-score of just 0.09, MCC of 0.126, and an H-measure of 0.638. Further exacerbating this discrepancy is the notably large number of false positives (FP = 6595), which clearly illustrates that the ROC-AUC cannot adequately penalize the misclassification of negative class instances. Similarly, another striking contradiction is observed when examining Logistic Regression with SMOTE sampling. Despite achieving a high ROC-AUC score of 0.968, this combination demonstrates poor F2 (0.237), MCC (0.227), and H-measure (0.651) scores, which are further compounded by an extremely high false positive rate (FP = 2019). This trend persists across multiple combinations, highlighting ROC-AUC’s inability to reflect meaningful performance deficiencies in classifiers when dealing with highly imbalanced datasets.

The inconsistency in performance, as indicated by the ROC-AUC compared to more practically relevant metrics, is further exemplified by the Logistic Regression classifier combined with Borderline-SMOTE sampling, which achieves an acceptable ROC-AUC score of 0.935. Nonetheless, substantial performance issues arise, as clearly evidenced by an F2-score of 0.448, an MCC of 0.360, and an H-measure of 0.558, coupled with a high false positive count (FP = 647). These results underscore the critical failure of ROC-AUC in accurately capturing and penalizing the actual misclassification costs associated with rare-event classes. We emphasize that the behavior observed for logistic regression under aggressive oversampling is not a failure of the classifier per se, but an expected consequence of training a linear model on heavily resampled data at extreme prevalence; the key finding is that ROC-AUC remains insensitive to the resulting explosion in false positives, whereas MCC, F2, PR-AUC, and the H-measure appropriately penalize such configurations.

Conversely, metrics such as MCC, F2, and H-measure exhibit greater consistency in identifying performance inadequacies, effectively distinguishing between well-performing and poorly performing models. For instance, the baseline Random Forest classifier achieves strong, stable performance across MCC (0.855), F2 (0.796), and H-measure (0.761) with low FP (5), clearly indicative of genuine classification effectiveness.

In summary, the empirical evidence firmly establishes that, despite its widespread use, ROC-AUC often provides an overly optimistic and misleading assessment of classifier performance in highly imbalanced contexts. Alternative metrics, specifically MCC, F2, and H-measure, are more effective and accurate indicators of genuine predictive performance and should be preferred in evaluation methodologies involving rare-event classification.

Table 4 summarizes the analysis conducted on the Fraud dataset, encapsulating the observed performance ranges, sensitivity to variations in false positives and false negatives, and key observations for ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, F2-score, MCC, and H-measure. This comparative overview highlights significant discrepancies between ROC-AUC and alternative metrics, underscoring ROC-AUC’s limited sensitivity to misclassification costs in highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 4.

The summary of the analysis on the fraud dataset.

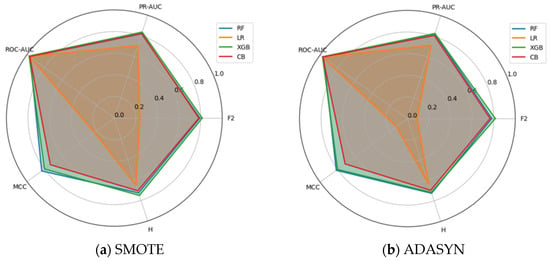

Complementing the scalar summaries in Table 4, a concise cross-metric visualization aids interpretation. Figure 1a–e provide small-multiples radar plots that compare five evaluation criteria, including F2, H-measure, MCC, ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC, for Random Forest, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and CatBoost under each resampling strategy. Axes are fixed across panels and scaled to [0, 1]; polygons report fold-wise means. The purpose is illustrative: to visualize pattern and separation across metrics, complementing the confidence-interval and rank-based analyses reported later.

Figure 1.

(a–e) Multi-metric radar plots for the Fraud dataset across five resampling strategies. Axes are scaled to [0, 1]; polygons show mean performance across cross-validation folds, with larger and more uniformly shaped polygons indicating stronger overall performance across the metric bundle.

Two consistent regularities are apparent across all samplers. First, ROC-AUC exhibits a ceiling effect: for every classifier and sampler, the ROC-AUC spoke lies close to the outer ring, producing minimal model separation. Second, the threshold-dependent/cost-aligned metrics (MCC and F2) reveal substantial differences that the ROC-AUC curve masks. In particular, Logistic Regression deteriorates sharply under synthetic minority schemes: under SMOTE and ADASYN, the Logistic Regression polygon collapses on the MCC and F2 axes, while remaining near-maximal on ROC-AUC, indicating a severe precision loss (inflated false positives) that does not materially affect rank-based AUC. The tree/boosted models (Random Forest, XGBoost, CatBoost) remain comparatively stable in terms of MCC and F2 across samplers, with XGBoost and Random Forest typically forming the largest polygons (i.e., the strongest across the bundle).

The Baseline panel serves as a reference: ensembles dominate on MCC and F2, while Logistic Regression exhibits weaker performance but does not collapse. Moving to SMOTE and ADASYN, the Logistic Regression degradation intensifies (MCC and F2 shrink markedly) even though PR-AUC and H-measure decline only moderately, and ROC-AUC stays saturated. This pattern is consistent with decision-boundary distortion and score miscalibration induced by aggressive oversampling at a prevalence of 0.17%, which disproportionately inflates false positives at practically relevant thresholds. Borderline-SMOTE and SVM-SMOTE exhibit the same qualitative behavior, albeit with milder Logistic Regression degradation; ensembles, however, retain broad, well-rounded polygons, reflecting their robustness to these resampling variants.

Taken together, the radars visualize the complementarity within the proposed metric bundle. PR-AUC and H-measure track the MCC and F2 separations (though less dramatically), reinforcing their role as threshold-free and cost-sensitive companions, respectively. Conversely, the near-constant ROC-AUC across panels underscores its limited diagnostic value in this ultra-imbalanced setting. These visual regularities align with our Kendall-τ concordance results (strong agreement among MCC, F2, H-measure, and PR-AUC; weak with ROC-AUC) and the critical-difference rankings that favor tree/boosted models. We therefore use the radars as an intuitive summary of sampler–classifier interactions and as corroborating evidence for the central claim: relying solely on ROC-AUC can misrepresent practical performance, whereas a multi-metric, cost-aligned protocol reveals operationally meaningful differences.

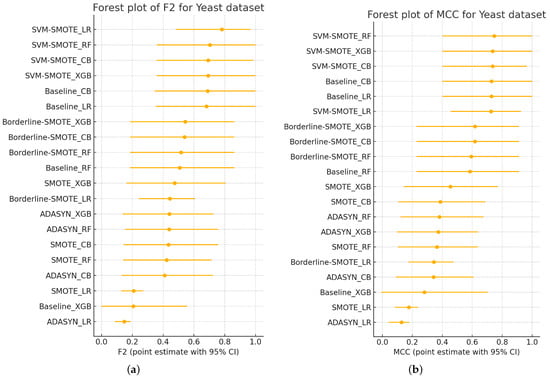

5.1.2. Yeast Dataset Results

Table 5 presents the results of 20 distinct classifier–sampler configurations, including the corresponding confusion matrix components and five evaluation metrics. All evaluations were conducted on the test set (unseen data) of the Yeast dataset. The empirical evaluation conducted on the Yeast dataset clearly demonstrates the limitations inherent in relying on ROC-AUC as an evaluation metric for rare-event binary classification tasks. Although ROC-AUC scores across various classifiers and sampling methods frequently appear stable or relatively high, a deeper analysis using alternative metrics reveals significant shortcomings in the reliability of ROC-AUC for highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 5.

The results on the Yeast dataset.

For instance, the Logistic Regression classifier combined with SMOTE sampling yields an apparently high ROC-AUC score of 0.908. However, this performance is sharply contradicted by considerably lower scores in crucial alternative metrics, such as F2 (0.207), MCC (0.174), and H-measure (0.677). The substantial false positive rate observed in this scenario (FP = 92) further highlights the inability of ROC-AUC to reflect the practical costs associated with increased false alarms effectively. Similarly, the XGBoost classifier combined with SMOTE sampling yields a ROC-AUC score of 0.884, which initially appears moderate. However, detailed metrics, including F2 (0.484), MCC (0.455), and H-measure (0.353), reveal critical weaknesses in performance, particularly when considering that even a relatively modest increase in false positives (FP = 4) can negatively impact the model’s practical effectiveness.

Additionally, analysis of the Logistic Regression classifier with ADASYN sampling provides further evidence of ROC-AUC’s limitations. Despite maintaining a high ROC-AUC score (0.908), this combination demonstrates poor performance in alternative metrics: F2 at 0.146, MCC at 0.125, and H-measure at 0.677. Moreover, this classifier configuration suffers from an extremely high false positive count (FP = 142), further underscoring the ROC-AUC’s inadequate sensitivity to misclassification costs.

Conversely, metrics such as MCC, F2, and H-measure consistently provide a more accurate representation of classifier performance, effectively distinguishing between models that perform well and those that do not. For example, the baseline Random Forest classifier achieves stable and relatively high scores across MCC (0.608), F2 (0.536), and H-measure (0.577), while maintaining a low false positive count (FP = 1), clearly signaling robust classification capability.

In summary, the empirical evidence from the Yeast dataset clearly demonstrates that ROC-AUC often presents a misleadingly optimistic view of classifier performance in highly imbalanced scenarios. Alternative metrics, such as MCC, F2, and H-measure, emerge as more reliable and practically meaningful indicators of model performance in rare-event classification problems. Table 6 summarizes the detailed analysis conducted on the Yeast dataset, presenting the performance range, sensitivity to false positives and false negatives, and key observations for ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, F2-score, MCC, and H-measure. This summary clearly highlights the inadequacy of ROC-AUC and supports the practical relevance and greater accuracy of alternative metrics for highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 6.

The summary of the analysis on the Yeast dataset.

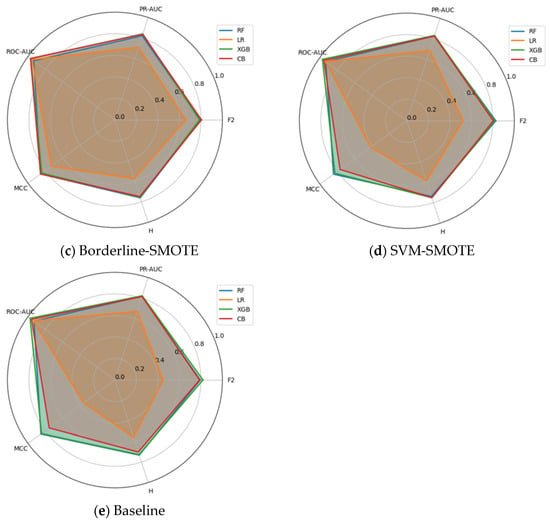

In addition to the scalar results in Table 6, a compact cross-metric perspective provides an integrated view. Figure 2a–e present small-multiples radar plots for the Yeast dataset (1.35% positives), comparing F2, H-measure, MCC, ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC for Random Forest, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and CatBoost under each resampling strategy. Axes are fixed across panels, scaled to [0, 1], and polygons report fold-wise means. As with the Fraud radars, the goal is illustrative: to visualize patterns and separation across metrics, complementing the following confidence-interval and rank-based analyses.

Figure 2.

(a–e) Multi-metric radar plots for the Yeast dataset across five resampling strategies. Axes are scaled to [0, 1]; polygons show mean performance across cross-validation folds, with larger and more uniformly shaped polygons indicating stronger overall performance across the metric bundle.

Two regularities again emerge. First, ROC-AUC remains near the outer ring for all models and samplers, yielding limited separation. Second, threshold-dependent/cost-aligned metrics (MCC and F2) reveal material differences that ROC-AUC alone obscures, with PR-AUC and H-measure generally moving in the same direction, albeit less sharply.

Dataset-specific nuances are notable. In the Baseline panel, XGBoost exhibits a pronounced collapse on F2, MCC, PR-AUC, and H, despite a high ROC-AUC score, an archetypal instance of AUC saturation masking practically relevant errors. CatBoost and Logistic Regression form larger, more rounded polygons, and Random Forest sits in between. Under SMOTE and ADASYN, Logistic Regression exhibits a mixed profile: PR-AUC and H increase substantially, whereas MCC (and at times F2) decreases, indicating that oversampling improves ranking and cost-weighted separation while simultaneously inflating false positives at decision-useful thresholds (score–threshold miscalibration). Borderline-SMOTE mitigates this tension, with milder degradation in Logistic Regression on MCC and F2, and stable ensemble performance. SVM-SMOTE yields the most balanced polygons overall (especially for Logistic Regression and CatBoost), suggesting that margin-aware synthesis can enhance both ranking-based and threshold-dependent metrics on the Yeast dataset.

Taken together, these radars (i) make the ROC-AUC ceiling effect visually explicit; (ii) highlight sampler–classifier interactions that matter operationally (e.g., Baseline XGBoost collapse; Logistic Regression oversampling trade-offs); and (iii) show PR-AUC and H-measure qualitatively tracking the MCC and F2 separations. The visual patterns are consistent with the Kendall-τ concordance and critical-difference rankings reported for Yeast, reinforcing the central claim that relying solely on ROC-AUC is insufficient. In contrast, a multi-metric, cost-aligned protocol reveals differences in practical consequence.

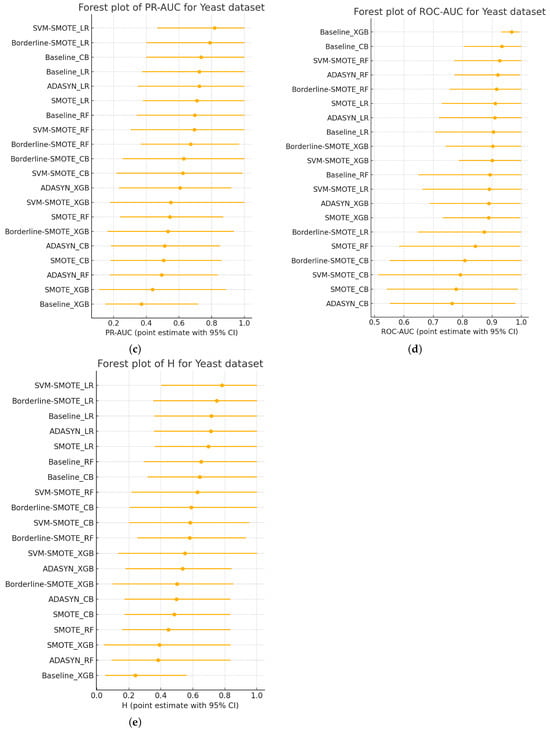

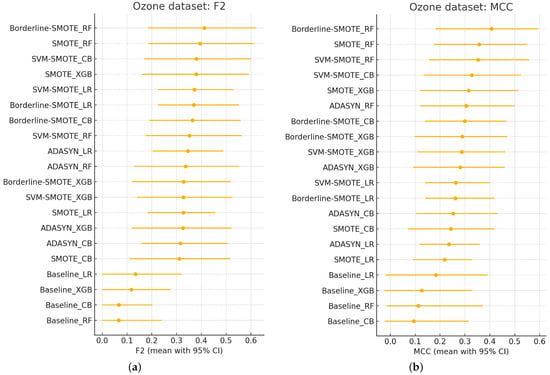

5.1.3. Ozone Dataset Results

Table 7 presents the results of 20 distinct classifier–sampler configurations, including the corresponding confusion matrix components and five evaluation metrics. All evaluations were conducted on the Ozone dataset’s test set (unseen data). The empirical evaluation conducted on the Ozone dataset provides further compelling evidence of the limitations inherent in using ROC-AUC as an evaluation metric for rare-event binary classification tasks. Despite ROC-AUC scores consistently appearing moderate to high across multiple classifiers and sampling methods, a detailed examination using alternative metrics reveals substantial shortcomings in the reliability of ROC-AUC for highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 7.

The results on the Ozone dataset.

For example, the Logistic Regression classifier combined with SMOTE sampling achieves an ROC-AUC of 0.860, which initially might suggest acceptable model performance. However, this apparent performance contrasts sharply with notably weaker results in critical alternative metrics: F2-score at 0.336, MCC at 0.225, and H-measure at 0.105. This combination also yields a substantial false positive rate (FP = 57), highlighting the ROC-AUC’s failure to capture the practical implications of increased false alarms adequately.

Similarly, XGBoost with Borderline-SMOTE achieves a relatively moderate ROC-AUC of 0.874; however, a deeper inspection through alternative metrics reveals significant shortcomings. Despite its ROC-AUC score, the combination yields a relatively low F2-score (0.337), MCC (0.294), and H-measure (0.095), alongside an elevated false positive count (FP = 15). These findings further underscore ROC-AUC’s inability to reflect misclassification costs sensitively. Another illustrative case is observed with Logistic Regression using ADASYN sampling. The ROC-AUC score of 0.860 might initially seem satisfactory; however, alternative metrics such as F2 (0.338), MCC (0.228), and H-measure (0.105) clearly indicate substantial deficiencies in performance. Moreover, the high false positive count (FP = 56) strongly emphasizes ROC-AUC’s limited sensitivity to the actual cost of misclassification.

In contrast, metrics such as MCC, F2, and H-measure consistently provide a more precise representation of classifier performance by distinguishing between models that perform genuinely well and those that perform inadequately. For instance, the Random Forest classifier combined with Borderline-SMOTE sampling exhibits relatively strong and balanced performance across MCC (0.407), F2 (0.417), and H-measure (0.215), with a comparatively low false positive rate (FP = 9), clearly indicating effective classification performance. In summary, empirical evidence from the Ozone dataset strongly reinforces that ROC-AUC is often misleadingly optimistic when assessing classifier performance in highly imbalanced scenarios. Alternative metrics, particularly MCC, F2, and H-measure, provide a more reliable and practical assessment of classifier effectiveness in rare-event classification tasks.

Table 8 summarizes the comprehensive analysis of the Ozone dataset, capturing the observed performance ranges, sensitivity to variations in false positives and false negatives, and key observations for ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, F2-score, MCC, and H-measure. This comparative overview highlights the inadequacies of ROC-AUC and underscores the greater practical relevance and accuracy of MCC, F2, and H-measure in assessing classifier performance on highly imbalanced datasets.

Table 8.

The summary of the analysis on the Ozone dataset.

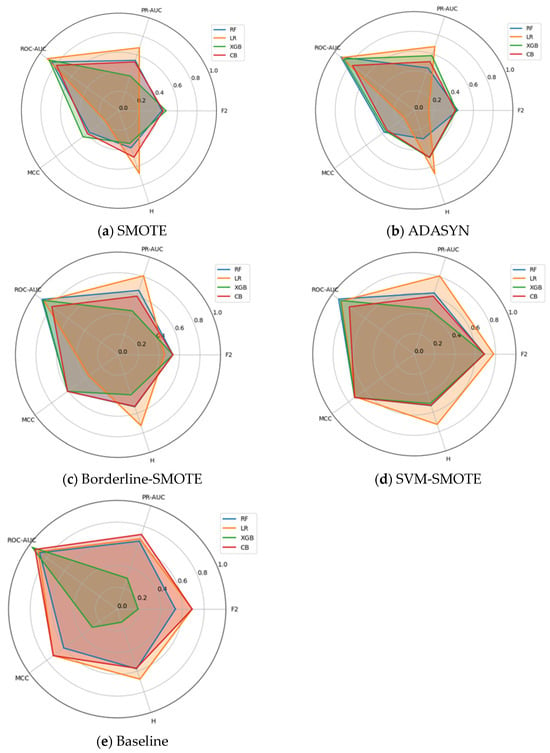

Beyond the scalar summaries in Table 8, a compact cross-metric view is useful. Figure 3a–e show small-multiples radar plots for the Ozone dataset (≈3% positives), comparing F2, H-measure, MCC, ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC for Random Forest, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and CatBoost under each resampling strategy. Axes are fixed across panels, scaled to [0, 1], and polygons report fold-wise means. As in the prior datasets, these plots are illustrative and provide a compact view of pattern and separation across metrics that complements the subsequent confidence-interval and rank-based analyses.

Figure 3.

(a–e) Multi-metric radar plots for the Ozone dataset across five resampling strategies. Axes are scaled to [0, 1]; polygons show mean performance across cross-validation folds, with larger and more uniformly shaped polygons indicating stronger overall performance across the metric bundle.

Two regularities recur. First, ROC-AUC lies close to the outer ring for all models and samplers, yielding limited discriminatory power among classifiers. Second, the threshold-dependent/cost-aligned metrics (MCC and F2) exhibit meaningful spread, with PR-AUC and H-measure generally moving in the same qualitative direction (though less sharply), thereby visualizing the complementarity within the proposed metric bundle.

Dataset-specific nuances are evident. In the Baseline panel, Random Forest forms the broadest and most balanced polygon, leading on MCC, F2, and PR-AUC, while CatBoost is competitive, and Logistic Regression and XGBoost exhibit weaker performance, despite uniformly high ROC-AUC for all four models. Under SMOTE, polygons contract on MCC and F2 across models (with only modest changes in PR-AUC and H-measure), indicating that naive oversampling degrades performance at decision-relevant thresholds even as rank-based AUC remains high. Borderline-SMOTE and SVM-SMOTE partially recover this loss: Random Forest again dominates on MCC and F2, and CatBoost closes the gap, whereas Logistic Regression and XGBoost improve mainly on PR-AUC and H-measure with smaller gains on MCC and F2. The most pronounced divergence occurs under ADASYN: Logistic Regression exhibits a marked increase in PR-AUC (and occasionally H-measure) while collapsing on MCC and F2, a signature of oversampling-induced score/threshold miscalibration that inflates false positives at practical operating points. In contrast, the ensemble methods maintain relatively rounded polygons across samplers, reflecting greater robustness to resampling variance.

Overall, the Ozone radars in Figure 3a–e, (i) make the ROC-AUC ceiling effect visually explicit, (ii) reveal consequential sampler–classifier interactions (e.g., ADASYN’s trade-off for Logistic Regression), and (iii) show PR-AUC and H-measure qualitatively tracking the separations exposed by MCC and F2. These visual regularities align with the Kendall-τ concordance and critical-difference rankings reported for Ozone, reinforcing the central conclusion that relying solely on ROC-AUC is insufficient. In contrast, a multi-metric, cost-aligned protocol surfaces operationally meaningful differences among models.

5.2. Cross-Domain Kendall Rank Correlations

5.2.1. Kendall Rank Correlations Between Metrics (Fraud Dataset)

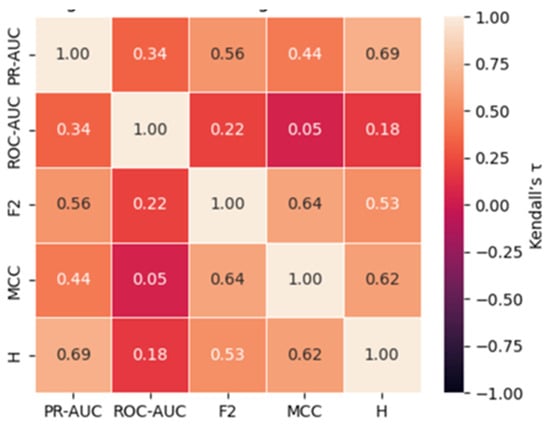

Having analyzed each dataset independently, we now synthesize results across datasets to assess the consistency of metric rankings and statistically significant differences between evaluation metrics. The pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients, summarized in Table 9 and illustrated in Figure 4, reveal a statistically coherent structure in how the five-evaluation metrics rank the 20 classifier–sampler configurations evaluated on the Fraud dataset, exhibiting a minority class prevalence of approximately 0.17%. Throughout the analysis, τ denotes Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient, and p-values refer to the two-sided significance level derived from the exact null distribution, as formulated by Kendall [50].

Table 9.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) and p-values between metrics on the Fraud dataset.

Figure 4.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) heatmap between metrics on the Fraud dataset.

An additional layer of analysis was conducted on the Fraud dataset using pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients (τ), accompanied by two-sided significance levels (p-values) calculated from the exact null distribution [50]. This analysis aimed to evaluate the degree of concordance between different performance metrics and further highlight the relative alignment or divergence of ROC-AUC with metrics more sensitive to rare-event classification.

Low Kendall’s τ values indicate that different metrics rank identical classifier–sampler pipelines inconsistently, implying that model selection is highly sensitive to metric choice in ultra-imbalanced settings; conversely, high concordance suggests that metric choice is less consequential for deployment decisions.

The results reveal a relatively weak positive correlation between PR-AUC and ROC-AUC (τ = 0.337, p = 0.0398), suggesting that although some concordance exists, it is neither strong nor robust. This weak association supports the notion that ROC-AUC may fail to reliably track changes in precision-recall performance under highly imbalanced conditions. More notably, ROC-AUC exhibits very low and statistically insignificant correlations with F2 (τ = 0.216, p = 0.183), MCC (τ = 0.047, p = 0.770), and H-measure (τ = 0.179, p = 0.288). These findings emphasize that ROC-AUC rankings are largely disconnected from metrics that prioritize misclassification costs and the effectiveness of detecting rare events.

In contrast, strong and statistically significant correlations are observed among the alternative metrics. PR-AUC shows moderate-to-strong correlations with F2 (τ = 0.565, p = 0.0005), MCC (τ = 0.438, p = 0.0071), and H-measure (τ = 0.695, p = 0.000003), indicating that these metrics capture similar aspects of classifier performance. Similarly, F2 correlates strongly with MCC (τ = 0.640, p = 0.000085) and H-measure (τ = 0.533, p = 0.0010), while MCC and H-measure themselves exhibit a strong concordance (τ = 0.617, p = 0.0001).

These results highlight two critical insights: first, the ROC-AUC is weakly aligned with metrics that account for precision, recall, and misclassification asymmetry; second, alternative metrics, such as F2, MCC, and H-measure, display substantial agreement, reinforcing their utility as complementary and reliable indicators for performance evaluation in highly imbalanced datasets.

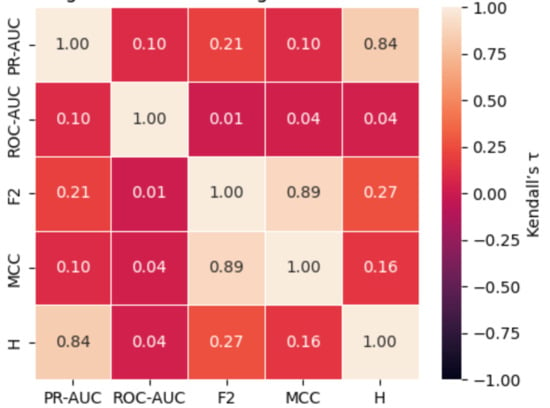

5.2.2. Kendall Rank Correlations Between Metrics (Yeast Dataset)

The pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients, summarized in Table 10 and illustrated in Figure 5, reveal a statistically coherent structure in how the five-evaluation metrics rank the 20 classifier–sampler configurations evaluated on the Yeast dataset, exhibiting a minority class prevalence of approximately 1.35%. Throughout the analysis, τ denotes Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient, and p-values refer to the two-sided significance level derived from the exact null distribution, as formulated by Kendall [50].

Table 10.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) and p-values between metrics on the Yeast dataset.

Figure 5.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) heatmap between metrics on the Yeast dataset.

An additional layer of analysis was conducted on the Yeast dataset using pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients (τ), accompanied by two-sided significance levels (p-values) calculated from the exact null distribution [50]. This analysis aimed to assess the degree of concordance between different performance metrics and further investigate the alignment of ROC-AUC with alternative measures sensitive to rare-event classification.

The results reveal an extremely weak and statistically insignificant correlation between PR-AUC and ROC-AUC (τ = 0.105, p = 0.5424), indicating a lack of meaningful concordance between these metrics. Furthermore, ROC-AUC exhibits negligible and non-significant correlations with F2 (τ = 0.011, p = 0.9475), MCC (τ = 0.039, p = 0.8178), and H-measure (τ = 0.043, p = 0.7947). These findings highlight the discrepancy between ROC-AUC and metrics that prioritize detecting rare events and penalize misclassification costs. In contrast, notable correlations are observed among alternative metrics. PR-AUC shows a strong and statistically significant correlation with H-measure (τ = 0.840, p < 0.0001), suggesting a high degree of agreement in how these metrics rank classifier performance. F2 and MCC demonstrate a robust concordance (τ = 0.893, p < 0.0001), highlighting their mutual sensitivity to class imbalances. However, F2 and H-measure (τ = 0.268, p = 0.1132) and MCC and H-measure (τ = 0.162, p = 0.3389) show weaker and statistically non-significant associations.

Overall, these results highlight two key insights: ROC-AUC exhibits minimal alignment with alternative metrics, underscoring its inadequacy in highly imbalanced scenarios; and strong correlations among specific pairs of alternative metrics (particularly F2 and MCC) indicate that they are particularly relevant in rare-event classification tasks.

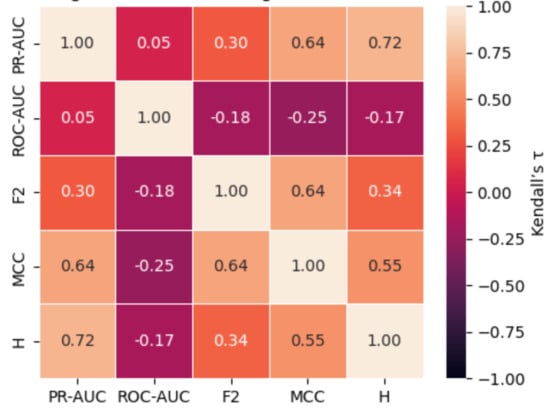

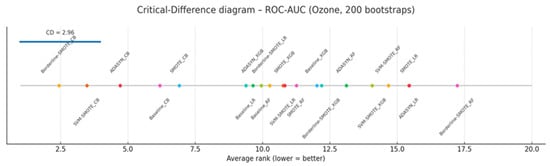

5.2.3. Kendall Rank Correlations Between Metrics (Ozone Dataset)

The pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients, summarized in Table 11 and illustrated in Figure 6, reveal a statistically coherent structure in how the five-evaluation metrics rank the 20 classifier–sampler configurations evaluated on the Ozone dataset, exhibiting a minority class prevalence of approximately 3.1%. Throughout the analysis, τ denotes Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient, and p-values refer to the two-sided significance level derived from the exact null distribution, as formulated by [50]. An additional layer of analysis was conducted on the Ozone dataset using pairwise Kendall rank correlation coefficients (τ), accompanied by two-sided significance levels (p-values) calculated from the exact null distribution [50]. This analysis aimed to evaluate the degree of concordance between different performance metrics and to assess ROC-AUC’s alignment with alternative measures sensitive to rare-event classification.

Table 11.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) and p-values between metrics on the Ozone dataset.

Figure 6.

Kendall rank correlations (τ) heatmap between metrics on the Ozone dataset.

The results show an extremely weak and statistically insignificant correlation between PR-AUC and ROC-AUC (τ = 0.053, p = 0.7732), suggesting almost no concordance between these metrics. More concerningly, ROC-AUC demonstrates negative correlations with F2 (τ = −0.185, p = 0.2559), MCC (τ = −0.248, p = 0.1271), and H-measure (τ = −0.168, p = 0.3189), though these associations are not statistically significant. These findings suggest that ROC-AUC may not align with alternative metrics and can even rank classifier performance inversely in some instances, further underscoring its limitations for evaluating imbalanced data. In contrast, strong and statistically significant positive correlations are observed among the alternative metrics. PR-AUC exhibits substantial concordance with MCC (τ = 0.639, p = 0.000086) and H-measure (τ = 0.716, p < 0.0001), highlighting shared sensitivity to precision-recall trade-offs and misclassification costs. Similarly, F2 correlates strongly with MCC (τ = 0.640, p = 0.000085) and moderately with H-measure (τ = 0.343, p = 0.0349), while MCC and H-measure also display a robust association (τ = 0.554, p = 0.0007).

These findings reinforce two critical insights: ROC-AUC is poorly aligned with alternative metrics and may produce misleading performance rankings in highly imbalanced contexts; meanwhile, the strong concordance among PR-AUC, F2, MCC, and H-measure underscores their suitability as reliable and complementary metrics for evaluating rare-event classification performance.

5.3. Cross-Metric Synthesis and Evaluation Strategy

The synthesis of results across the Fraud, Yeast, and Ozone datasets reinforces a clear hierarchy among the evaluated metrics. Kendall’s rank correlation analyses consistently demonstrate that τ(MCC, F2) ≫ τ(PR-AUC, MCC or F2) ≫ τ(ROC-AUC, any other metric). This ordering highlights MCC and F2 as capturing similar operational trade-offs, PR-AUC as offering a compatible but threshold-free perspective, and ROC-AUC as providing minimal practical guidance in ultra-imbalanced settings. Consequently, we recommend a reporting bundle of MCC + PR-AUC, with F2 included when high recall is mission-critical, while ROC-AUC should be reported only with explicit caution regarding its limitations in ultra-imbalanced settings. Table 12 shows that the cross-domain analysis of the three datasets yields consistent conclusions.

Table 12.

The cross-domain analysis of the three datasets.

The findings reinforce that MCC and F2-score capture complementary aspects of model performance, reflecting trade-offs between false positives and false negatives at a fixed decision threshold. While MCC offers a symmetric, prevalence-agnostic summary, F2 is more sensitive to recall and proves particularly useful when the cost of false negatives outweighs that of false positives. PR-AUC, although threshold-independent, aligns reasonably well with these metrics, providing a global view of ranking quality that remains valuable when decision thresholds are not yet defined. ROC-AUC, by contrast, consistently fails to align with operational needs in ultra-imbalanced settings. Its scores remain artificially high even when models exhibit severe false-positive inflation, thus obscuring practical deficiencies that MCC, F2, and PR-AUC readily expose.

These observations point to a clear recommendation: PR-AUC and MCC should form the core of any evaluation framework for rare-event classification. Where high recall is critical (for instance, in fraud detection or medical screening), the inclusion of F2 offers additional insight aligned with stakeholder priorities. ROC-AUC may only be reported for completeness or legacy comparisons if accompanied by a clear disclaimer outlining its insensitivity to class imbalance and misalignment with operational costs. These conclusions are not merely theoretical; they translate into actionable strategies for practitioners working with datasets where the minority class comprises less than 3% of the population. The primary recommendation is to adopt PR-AUC to evaluate global ranking ability and MCC as a threshold-specific measure of balanced performance. In domains where false negatives carry disproportionate risk, such as missed fraud cases or undiagnosed patients, the F2-score serves as a vital complement, emphasizing recall without compromising the need for precision.

The consistent misbehavior of ROC-AUC in our study warrants caution. In multiple cases, ROC-AUC ranked models favorably even when both MCC and PR-AUC indicated poor discriminative performance. For example, the combination of Logistic Regression with SMOTE in the fraud dataset achieved a ROC-AUC score well above 0.90, despite a significant increase in false positives (FP = 2019, MCC = 0.23), effectively masking operational failure. Such discordance between ROC and MCC rankings (especially when discrepancies exceed 10 percentile points) should be treated as a red flag in model validation pipelines.

Oversampling methods, too, must be evaluated in a contextual manner. While techniques like SMOTE can offer measurable gains in certain domains (e.g., the Yeast dataset), they may introduce detrimental artifacts in other contexts. It is therefore critical that researchers assess the impact of oversampling not only on headline metrics but also on the raw components of the confusion matrix. Finally, in settings where the economic or human cost of misclassification is asymmetric, the flexible Fβ family offers tailored sensitivity. Selecting β between 2 and 4 allows evaluators to reflect real-world stakes by emphasizing recall where it matters most, while retaining the interpretability of a single scalar score.

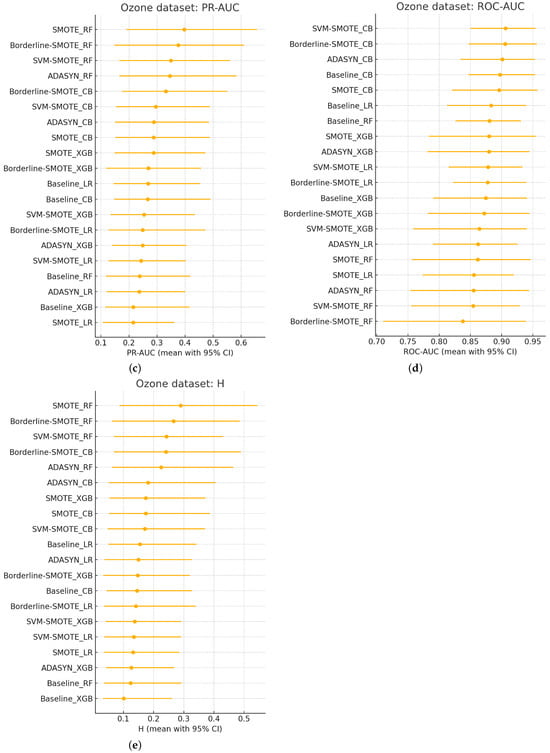

5.4. Statistical Testing and Confidence Intervals

To assess the statistical reliability of performance estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed for each evaluation metric using a stratified bootstrap procedure. This involved generating 2000 resampled replicates per test fold while maintaining the original class distribution to preserve the inherent imbalance structure. Pairwise comparisons of ROC-AUC values between classifier–sampler configurations were conducted using the DeLong test for correlated receiver operating characteristic curves [53], with corresponding p-values reported. We employed the Friedman aligned-ranks test for comparisons involving more than two configurations, followed by the Nemenyi post hoc procedure to identify statistically significant differences at a family-wise significance level of α = 0.05.

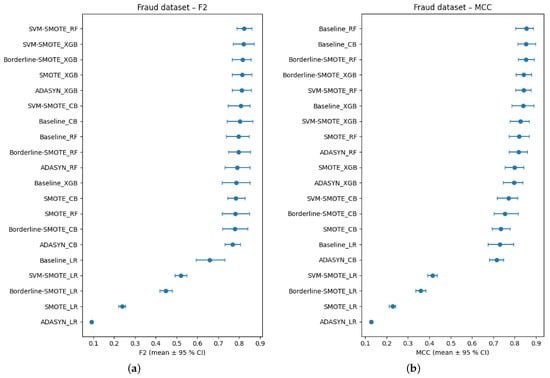

5.4.1. Bootstrap CIs and DeLong Test (Fraud Dataset)

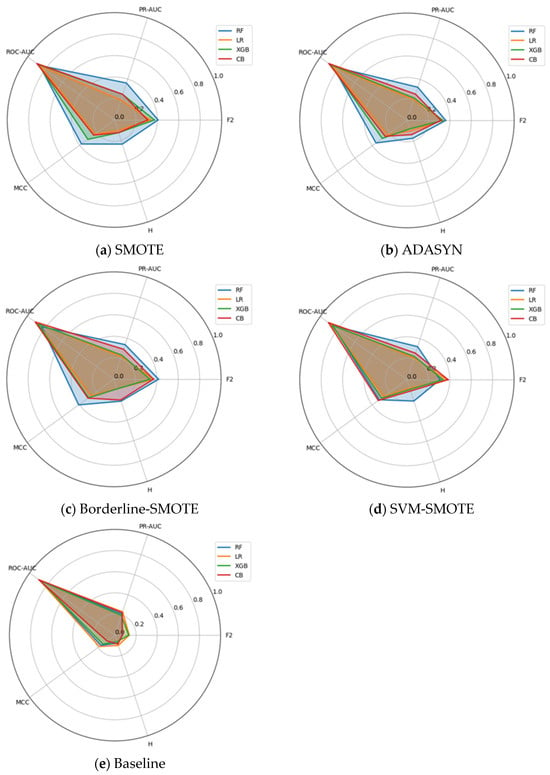

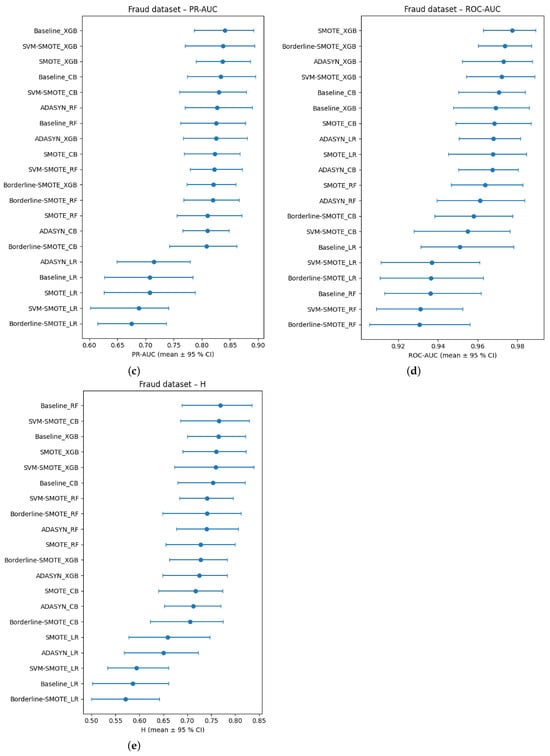

Figure 7a–e display stratified-bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the Fraud data, while Figure 8 gives the ROC-AUC critical-difference (CD) diagram computed from 200 bootstrap resamples.

Figure 7.

(a–e) Bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals for each evaluation metric on the Fraud dataset.

Figure 8.

Nemenyi critical-difference diagram derived from 200 stratified bootstrap resamples of the test fold on the Fraud dataset.

The ROC-AUC scores reported in Figure 7a exhibit a strong ceiling effect across all classifier–sampler configurations evaluated on the Ozone dataset. Every method achieves an ROC-AUC of at least 0.92, with fifteen out of twenty configurations densely concentrated within the narrow 0.94–0.97 interval. These overlaps in confidence intervals reflect the saturation of ROC-AUC under conditions of extreme class imbalance. This observation is quantitatively confirmed by the critical difference diagram in Figure 8, where only the top-ranked Borderline-SMOTE + CB and the lowest-ranked Borderline-SMOTE + RF are distinguishable beyond the Nemenyi threshold (CD ≈ 2.96). All remaining methods fall within the critical band, rendering ROC-AUC largely ineffective in resolving meaningful differences among most classifiers, an outcome consistent with its known limitations in highly imbalanced domains [54].

By contrast, other evaluation metrics provide a more precise and discriminative perspective. Figure 7b shows the PR-AUC results distribute the same twenty methods across a substantially broader interval (0.62–0.88). Baseline XGBoost and SVM-SMOTE + XGB emerge as top performers (mean PR-AUC ≈ 0.87; CI: 0.83–0.90), while SMOTE + LR and ADASYN + LR are positioned at the bottom (≈0.65; CI: 0.61–0.69). Metrics based on confusion-matrix outcomes further support this stratification: MCC and F2 (β = 2), presented in Figure 7c,d, respectively, rank SVM-SMOTE + RF and Borderline-SMOTE + XGB among the highest (MCC ≈ 0.88; F2 ≈ 0.82), while all logistic-regression variants remain under MCC = 0.30, indicating inferior performance.

Further refinement is provided by the H-measure in Figure 7e, which incorporates cost sensitivity and penalizes excessive false positives. Here, Baseline Random Forest and SVM-SMOTE + CB occupy the top positions (H ≈ 0.78), despite not being among the leaders in terms of ROC-AUC. Compared to the bottom six, the top eight H-measure configurations present non-overlapping CIs, confirming a statistically and practically significant separation that ROC-AUC fails to detect. Rank-correlation analyses reinforce these discrepancies. As reported in Table 9, Kendall’s τ coefficients reveal strong concordance between PR-AUC and the H-measure, and between F2 and MCC (0.64 ≤ τ ≤ 0.70), but substantially weaker alignment between ROC-AUC and any other metric (τ ≈ 0.04–0.33). The CD diagram in Figure 8 visually supports this conclusion, as configurations clustered centrally under ROC-AUC rankings are widely dispersed in the rankings of other metrics. These results underscore the persistent misalignment of ROC-AUC with metrics that better reflect the trade-offs relevant in rare-event binary classification.

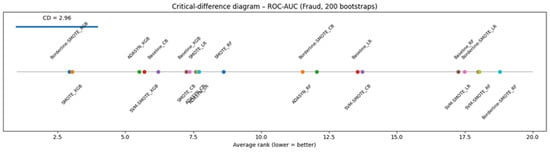

5.4.2. Bootstrap CIs and DeLong Test (Yeast Dataset)

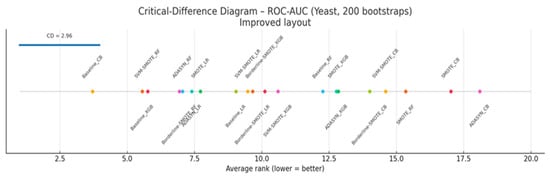

Figure 9a–e show bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals for each evaluation metric, while Figure 10 reports a Nemenyi critical-difference diagram derived from 200 stratified bootstrap resamples of the test fold. Figure 9a illustrates the distribution of ROC-AUC scores across all classifier–sampler combinations evaluated on the Yeast dataset. Despite underlying architectural and sampling differences, nearly all configurations attain ROC-AUC values exceeding 0.75, with nine methods clustering within the narrow 0.85–0.90 interval and displaying substantially overlapping bootstrap confidence intervals. The critical difference diagram in Figure 10 highlights this finding: no method pair exceeds the Nemenyi threshold (CD ≈ 2.96) in terms of average rank. This inability of ROC-AUC to distinguish between models is consistent with its known ceiling effect in highly imbalanced settings, where the abundance of negative-class samples artificially inflates the curve’s area—even for classifiers with limited discriminative ability [54].

Figure 9.

(a–e) Bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals for each evaluation metric on the Yeast dataset.

Figure 10.

Nemenyi critical-difference diagram derived from 200 stratified bootstrap resamples of the test fold on the Yeast dataset.