Abstract

Growing cooling demand and environmental concerns motivate research into alternative technologies capable of converting low-grade heat into useful cooling. This study proposes a regression-assisted multi-objective optimisation framework using the Ant Lion Optimiser and its multi-objective variant to jointly maximise the coefficient of performance (COP), cooling capacity () and waste-heat recovery efficiency (). Pareto-optimal solutions exhibit a one-dimensional ridge in which declines, and COP and increase simultaneously. Within the explored bounds, non-dominated ranges span COP = 0.674–0.716, 18.3–27.5 kW and 0.118–0.127, with a practical compromise near COP ≈ 0.695, ≈ 24 kW and 0.122–0.123. Compared to the typical reported COP band for single-stage silica-gel/water ADCs, the practical compromise solution (COP ≈ 0.695) offers a conservative COP improvement of approximately 16% when benchmarked against COP = 0.6, while the compromise ( ≈ 24 kW) represents a conservative increase of approximately 20% relative to the upper product-class reference (20 kW). A one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis with re-optimisation identifies the hot- and chilled-water inlet temperatures and exchanger conductance as the dominant decision variables and maps diminishing-return regions. This framework can effectively utilise low-grade heat in future low-carbon buildings and processes, supporting the configuration of ADC systems.

1. Introduction

Recent decades have seen the transition of air conditioners from luxury to an integral part of modern standards of well-being and comfort. Aside from extreme heat-related illnesses like heat stroke, exhaustion and syncope, exposure to extremely low temperatures, particularly among infants and the aged, urbanisation, rising temperatures, and incomes are stoking the global demand for space cooling [1,2,3]. Human activities are gradually contributing to global warming and causing dramatic shifts in energy-use patterns [4]. The energy cost of cooling buildings steadily rises relative to other energy uses [5]. Projections show that 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050, implying an expansion of air conditioner ownership and electricity use this decade and beyond [6,7]. This emphasises the need to use modern digital tools and decision-support technologies to configure and optimise efficient, sustainable and low-carbon cooling solutions.

Typically, indoor spaces are cooled by electric fans or air conditioners, with air conditioners being the most energy-intensive choice. The most prevalent refrigeration and air conditioning systems are the mechanical vapour compression (MVC) systems, and they require a substantial amount of high-grade energy to power the compressor and initiate the cooling cycle [8,9]. Additionally, the refrigerants commonly used in MVC systems have been reported to have high ozone depletion potential (ODP) and global warming potential (GWP) and could be very poisonous [10,11].

It has been reported that the cooling of rooms accounts for almost a fifth of the electricity used by buildings. Currently, approximately 135 million air conditioners are sold annually, with projections of even higher sales figures in the coming years [12]. The increased usage of air conditioning has an instantaneous effect on electricity usage. This brings into question the long-term supply and sustainability of electricity resources [13]. Moreover, a 2–3% annual growth in electricity demand by 2030 is anticipated by the projections of the expanding world economy [13].

These drawbacks of mechanical vapour compression (MVC) systems have driven research efforts to explore and identify energy-efficient technological cooling alternatives [9]. The adsorption cooling chiller (ADC) represents a promising alternative to the conventional, high-energy-consuming MVC systems. Notably, multi-bed adsorption chillers have shown significant potential as a feasible solution. A key advantage of ADCs is their ability to operate fully or partially by low-grade energy sources like industrial solar, biomass and waste heat for heating and cooling [14]. In addition, they use environmentally safe refrigerants with further benefits like durability, quiet functioning, lower energy requirements, and simple controls [15,16]. Thus, ADCs are presented as emerging sustainable cooling technologies that can be used for future low-carbon buildings and industrial operations. While adsorption chillers offer potential advantages, they also have notable limitations. These include suboptimal performance indicators like Specific Cooling Power (SCP), Coefficient of Performance (COP), high manufacturing costs, system complexity and sensitivity to operational parameters such as variations in flow rates, temperature, and working fluids. Addressing these limitations requires a robust research approach to optimise long-term dynamic performance, particularly when powered by waste or renewable heat sources [17].

This study optimises the performance of a single-stage dual-bed ADC, allowing the findings to be potentially extended to complex bed ADCs in the future. Specifically, it develops a framework that acts as a computerised decision-support tool for configuring such ADC systems.

Optimisation techniques such as single and multi-objective optimisation, which use advanced algorithms, can be employed to systematically analyse parametric interactions and serve as sub-models to improve the performance metrics and design criteria of ADCs. Optimisation techniques are computational methods used for finding ideal designs, and multi-objective optimisation specifically handles problems with several objectives, where the inherent conflicting nature of these objectives results in multiple solutions. Consequently, the multi-objective nature of most real-world engineering problems makes them appropriate for multi-objective optimisation applications due to the inherent trade-offs between performance metrics [18,19]. When combined with surrogate models, these techniques form useful digital tools for exploring high-dimensional design spaces and supporting engineering decisions.

Our earlier work on algorithmic optimisation of ADC systems [20] provides a detailed comparative summary of optimisation and control studies for silica-gel/water and multi-bed ADCs. This includes three-bed mass-recovery cycles, periodic optimal control, and integrated design and control frameworks. In this present study, we build on previous research by focusing on a single-stage dual-bed silica-gel/water ADC.

This study introduces as a co-equal objective alongside COP and Qcc rather than a derived metric. As a co-equal to COP and , is used consistently through modelling, single and multi-objective optimisation, plotting, validation with external literature and design guidance. This is to explicitly inform design source utilisation choices and quantify how low-grade heat can be effectively converted to useful cooling. In this way, waste heat recovery efficiency is treated as a core design target as opposed to a secondary indicator.

The optimisation of ADC systems objective goes beyond thermodynamic enhancement to financial sustainability in real operations, which can be closely tied to economic engineering principles. Based on this, the proposed Regression-Assisted MOALO framework is best interpreted as an operational decision-support tool that improves how existing capital hardware is utilised by identifying set-points capable of improving the cooling performance delivered within the explored bounds. A fundamental economic barrier hindering the adoption of the ADC technology is the high cost per unit cooling capacity, which is strongly linked to the high volume of adsorbent materials and heat exchangers required, reducing the specific cooling power of the ADC [21,22].

Since the MOALO framework increases cooling output without changing the component sizes in the modelled envelope, it is possible to operationally amortise the same installed hardware investment over a larger cooling output. This can be interpreted as a reduction in “effective” specific cost at the operating point [21,22]. Although the ADC is driven by waste heat, additional costs are still incurred by the auxiliary energy demand for controls, pumps and other equipment, which affect the operational expenditure (OPEX). Improving COP can reduce the auxiliary load per unit of cooling delivered. Moreover, treating as a primary objective allows operators and facility managers to quantify the effective utilisation of thermal resources for useful cooling [23,24,25,26].

While a full cost model (CAPEX/OPEX/payback) remains outside the present study scope, optimising the ADC indirectly supports economic viability.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses the materials and methods; Section 3 covers the adsorption chiller system optimisation details, along with the Antlion optimisation technique and problem mathematical formulation; and Section 4 discusses the optimisation and sensitivity analysis results.

Thus, this research aims to achieve the following objectives:

- To introduce a regression-assisted multi-objective optimisation framework for a single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller using Ant Lion algorithms.

- To maximise the Coefficient of Performance (COP), cooling capacity (), and waste heat recovery efficiency of the adsorption chiller using the Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimisation technique.

- To conduct a sensitivity analysis with re-optimisation to determine the impacts of selected decision variables on COP, and and to identify regions of diminishing returns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Optimisation Framework

This study’s optimisation framework treats the silica-gel/water adsorption chiller as a black-box that maps a set of design and operating variables to three performance indicators: coefficient of performance (COP), cooling capacity () and waste-heat recovery efficiency (). It uses statistically validated regression models as quick substitutes for the complex thermo-physical behaviour, making it possible to extensively explore many design options without having to solve detailed dynamic models repeatedly.

We use a metaheuristic search algorithm to find the best combinations of decision variables that concurrently maximise all three objectives. This process creates a Pareto front, which shows the trade-offs between COP, and use. We then perform a one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis with re-optimisation to measure how key temperatures, mass flow rates, and heat-exchanger conductances affect performance and to identify where returns start to diminish. For a broader overview of metaheuristic optimisation strategies for adsorption chillers, see our previous work [20]. This paper focuses on the multi-objective Ant Lion Optimiser (MOALO) and how we use it to build and analyse the Pareto-optimal operating set.

This study does not model building cooling-load variation; however, the MOALO-generated Pareto set defines an operating envelope for the chiller that can be mapped to any external cooling-load (demand) profile as required.

2.2. Technical Characteristics of the Adsorption Chiller System

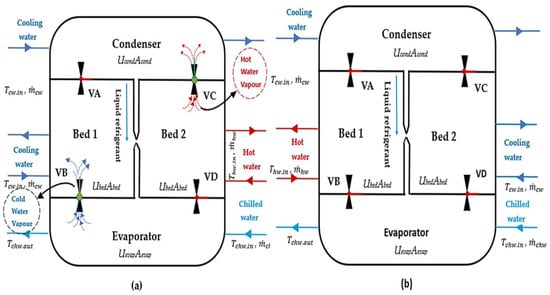

This study considers a single-stage, dual-bed silica-gel and water adsorption chiller that uses low-grade hot water as its energy source. Each bed alternates between adsorption and desorption depending on the pressure variations and the opening and closing of the valves. The system consists of an evaporator that cools the chilled water loop and a condenser to dissipate heat to the cooling water loop. Figure 1 shows the main components and flow paths, with a summary of the operating cycle. The evaporator and condenser connect to the adsorbent bed via four switching valves (V1–V4).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of a single-stage, dual-bed adsorption chiller (adsorption-desorption mode); (b) schematic diagram of a single-stage, dual-bed adsorption chiller (switching mode). Blue arrows represent cooling/chilled-water streams, red arrows indicate hot-water flow, and dashed arrows denote refrigerant-vapour movement.

In Mode A, V1 and V4 are closed, whereas V2 and V3 remain open to connect Adsorbent Bed 1 to the evaporator for the adsorption–evaporation process. The heat supplied by the chilled water reduces the pressure and temperature of the adsorbate (water), causing it to boil in the evaporator, producing vapour that is adsorbed in Bed 1. The cooling water circuit receives the heat rejected during the adsorption process. The desorption-condensation process also happens concurrently in Bed 2 and the condenser. In Bed 2, heat is supplied to desorb the refrigerant in the adsorbent material, and the heat of condensation is sent to the cooling water circuit.

The lumped heat-transfer representation through overall conductance terms (UA) and conditions of the external water hot-, cooling-, and chilled-water inlet temperatures and mass flow rates circuits operating envelopes define the quantitative technical characteristics adopted for the simulations and optimisation. These decision variables constitute the operating envelope of the studied chiller in this work and are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Decision variables and bounds.

2.3. Regression-Based Objective Functions (COP, Qcc, ηe)

Based on the system description in Figure 2 and Section 3.1, the three linear regression equations used as objective functions for the single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller are shown as Equations (2), (4) and (6) as follows:

Figure 2.

(a) Cone-shaped sand pit created by an antlion trap. (b) Antlion larva showing body structure and orientation during hunting.

- 1.

- Maximise COP: For adsorption cycles, COP is a primary indicator of performance calculated by estimating the cooling and heating taking place in the evaporator and condenser, respectively, according to [27]. The expression for the COP of the chiller can be represented as [28] in Equation (1):

= half cycle time

= chilled water mass flow rate

= specific heat capacity of water

= chilled water inlet temperature

= chilled water outlet temperature

= hot water inlet temperature

= hot water outlet temperature

The linear regression equations of COP, and with their adjusted coefficient of determination (R2) values are presented as follows according to Papoutsis et al. [29].

The COP for the single-stage dual-bed ADC is shown in Equation (2) as:

with

- where

= cooling water inlet temperature

= mass flow rate of hot water

= cooling water mass flow rate of the bed

= cooling water mass flow rate of the condenser

= adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance

= evaporator overall thermal conductance

= condenser overall thermal conductance

- 2.

- Maximise Cooling Capacity (): Cooling capacity is another primary indicator of adsorption chiller performance. is defined in Equation (3) by [30] as:

The linear regression representation of for the single-stage dual-bed ADC is defined according to [29] as Equation (4):

with

- 3.

- Maximise waste heat recovery efficiency (): Effective heat recovery strategies are pivotal in enhancing the overall system performance of ADCs. Following Papoutsis et al., is defined as a cycle-averaged ratio of useful cooling to hot-water heat input according to [29] as Equation (5):

Although ηₑ appears similar to COP because both metrics are expressed as a ratio of useful cooling to driving heat input, this study reports ηₑ as a waste-heat utilisation (recovery) metric, describing how effectively the available low-grade heat stream is converted into useful cooling. This follows common practice in waste-heat-driven adsorption literature, where the emphasis is on how to maximise useful cooling extracted from low-grade heat sources [31]. For benchmarking, similar multi-bed adsorption studies show improved waste heat usage under the same source conditions when increasing the number of beds and/or employing recovery schemes [31,32,33].

All quantities are cycle-averaged at quasi-steady operation, and pump work is neglected.

To show how much low-grade heat is converted to useful cooling for a single-stage ADC, , is optimised alongside COP, Equation (2) and , Equation (4). Equation (6) is propagated through all the optimisation processes, visualisations, and validity checks.

The regression expression used for [29] is:

with adjusted

Regression-based surrogate models adopted from Papoutsis et al. [29] as published were used without re-estimating the coefficients to evaluate COP, , and . The primary focus of the study is on multi-objective optimisation and trade-off exploration rather than regression redevelopment, so the reported model-fit metrics reported with the published equations are retained: COP Equation (2), Equation (4), and adjusted Equation (6). Detailed regression diagnostics are not recomputed here and remain as reported by Papoutsis et al. [29] All optimisation and interpretation are bound by the decision variable ranges in Table 1. Based on the objective functions from Equations (2), (4) and (6), the decision variables and bounds are presented in Table 1. Since the study adopts the regression-based surrogate models from Papoutsis et al. [29], the bounds in Table 1 were selected to remain within the operating/calibration envelope, which is treated as the validity domain of those correlations. Thus, all optimisation findings are interpreted solely within this domain, with no extrapolation beyond these limits claimed.

From the regression analysis equations of the selected variables (Equations (2), (4) and (6)), the adjusted R2 values of 0.8041 for COP, 0.9250 for , and 0.8371 for indicate that the chosen equations offer a good fit for the data. The high values of adjusted R2 across all three objective functions (COP, and ) validate the suitability of the selected equations for modelling the relationships between the variables.

The regression equations will serve as the objective functions to be maximised using the Antlion Optimiser (ALO) and Multi-Objective Antlion Optimiser (MOALO) algorithms, with the decision variables bounded as presented in Table 1.

To eliminate occlusions inherent to static three-dimensional (3-D) Pareto fronts and perspective distortion, all Pareto solutions from MOALO are presented as two-dimensional (2-D) pairwise projections with a single marker colour for maximum clarity. It is important to emphasise that the observed trends reflect re-optimised Pareto points and may not correspond to the linear marginal coefficients.

2.4. Ant Lion Optimiser (ALO)

ALO is a single-objective optimiser algorithm. There is just one global optimum solution in single-objective optimisation due to the existence of only a single optimal solution and the unary objective in single-objective problems [19]. Antlions go through two main stages in their life cycle: larvae and adults. Larvae mostly have a natural lifespan of three to five weeks, and the adults up to three years. They typically hunt as larvae and reproduce during their adulthood. To become adults, antlions undergo metamorphosis in a cocoon. Their unique hunting style and their favourite prey gave them their names. An antlion larva travels in a circle and throws out sand with its enormous jaws, digging a cone-shaped pit in the sand [34,35]. Figure 2 depicts multiple cone-shaped pits of varying diameters [36,37]. The antlion larva digs a cone-shaped trap and hides at the bottom, waiting for prey (ants) to be trapped. The cone’s edge is sharp and easily traps the ant at the bottom. Should the prey attempt to flee, the antlion destabilises it by flicking sand. Once captured, the prey is eaten underground, and the pit is cleared for the subsequent capture [38]. Interestingly, the hungrier the antlion, the larger the traps it digs [39] and/or when the moon is full [40]. Thus, the primary source of inspiration for the ALO algorithm comes from the foraging behaviour of antlions’ larvae and emulates the interaction between antlions and ants in the trap [37].

Given that ants randomly travel when searching for food, a random walk is chosen to model the ants’ movement as follows:

Equation (7) shows how the position vector, of antlions is calculated.

- Here:

- cumulative summation operation

- maximum number of epochs or iterations

- r = the prey’s step during a random walk

- is a stochastic function defined as:where:

- a single step within the iteration of the random walk process

- rand = a randomly generated number with uniform distribution in the interval of [0, 1].

The position of the ants is stored in memory and used to guide the optimisation process in a matrix format as shown in Equation (9):

where:

- a matrix for storing the position of each ant

- value of the variable of the ant

- number of ants

- number of variables

Using the objective function F (⋅), each ant’s decision vector is evaluated during optimisation and the resulting fitness values are stored in a column matrix as:

where:

- = matrix for saving the fitness of each ant

- value of the variable of the ant

- number of ants

- number of variables

It is assumed the antlions hid in the search spaces, awaiting their prey. Their hiding positions and fitness values are saved in the matrices as Equations (11) and (12), respectively:

where:

- = matrix holding the positional data for all antlions

- = matrix storing the fitness value of each antlion

- value of the dimension value of the ant

- total number of antlions

- number of variables (dimensions)

- = objective functions

Conditions applied during optimisation are:

- The ants explore the search space by random movements.

- Random movements are applied to all dimensions of the ants

- These random movements influence the traps set by the antlions

- The size of the traps/pits built by the antlions is proportional to their fitness levels.

- Antlions with large pits have a higher likelihood of trapping ants.

- An elite (fittest) or random antlion is likely to catch an ant in each iteration.

- An adaptive decrease in the range of the ants’ random walks simulates the sliding of the ants towards the antlions.

- An ant becoming fitter than the antlion implies that the ant is captured and drawn beneath the sand by the antlion.

- After capturing the prey at each hunt, the antlion updates its position to align with the prey and digs a pit/trap to improve its chances of catching more prey.

2.4.1. Random Walks of Ants

Equation (8) is the basis of the random walks of ants. Ants update their positions at every stage of the optimisation process with random walks. To prevent random walks outside the search spaces, the min–max normalisation scaling technique is used. This is given by:

where:

- = minimum of the random walk of the variable.

- = maximum of the random walk in the variable

- = minimum of the variable at the iteration.

- = maximum of the variable at the iteration.

Equation (13) must be applied in each iteration to prevent random walks outside the search.

2.4.2. Building the Trap

A roulette wheel is used to model the antlion’s hunting capabilities. As seen in Figure 3, the ant is assumed to be trapped by only one selected antlion. Thus, during the optimisation process, the roulette wheel operator in the ALO algorithm selects the antlions according to their fitness. This mechanism increases the fittest antlion’s chance of capturing ants.

Figure 3.

An ant walking randomly inside an antlion’s trap; the blue line shows the ant’s random path and the radial sectors indicate the regions of the trap.

2.4.3. Sliding Ants Towards the Antlion

Using the same roulette wheel mechanism, ants move arbitrarily, and antlions can build traps proportional to their fitness levels. Once the ant is trapped, the antlion throws sand towards the center of the pit, causing the trapped ant to slide down. This behaviour can be modelled mathematically by reducing the radius of the ant’s hypersphere random movement and presented as Equations (14) and (15).

where:

- = minimum variables at iteration.

- = maximum variables at iteration.

- = ratiowhere:

- = current iteration

- = maximum number of iterations

- = constant defined per the current iteration (

2.4.4. Catching the Prey and Rebuilding the Pit

This is the final stage of the hunt. Here, the ant that falls to the bottom of the pit is trapped in the antlion’s jaw and eaten up. From the eighth point in the conditions for optimisation, the prey is only caught when it becomes fitter than the antlion. Thus, the antlion needs to update its latest position to align with the hunted ant to improve its likelihood of catching new prey. In this regard, Equation (17) follows as:

where:

- = current iteration

- = position of the selected antlion at the iteration

- = position of the ant at the iteration

2.4.5. Elitism

Elitism is a fundamental characteristic of evolutionary algorithms that allows the storage of the best solution(s) obtained at every step of the optimisation process. For ALO, an elite refers to the best antlion saved from each iteration. This means the elite is the fittest antlion, so it should influence the movement of every ant during iterations. Therefore, it is assumed that the roulette wheel selects the antlion, and every ant randomly moves around the selected antlion and the elite concurrently, as depicted in Equation (18) as:

where:

- = position of the ant at the iteration

- = random walk around the antlion chosen by the roulette wheel at the iteration

- = random walk around the elite at the iteration

2.5. Single-Objective Optimisation

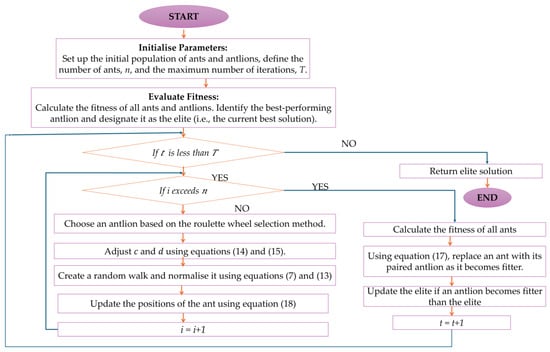

The optimisation flowchart for the ALO for a single objective optimisation is illustrated in Figure 4. After initialising ants and antlions, fitness is evaluated, and the best antlion is set as the elite. For each iteration t = T, the roulette wheel is used to select a guiding antlion, and the search bounds c, d are updated. Generate a normalised random walk around the selected antlion and elite, map it to the bounds c and d and update the ant’s position to advance the loop index, i. Re-evaluate ants, let the fitter ant replace its paired antlion, and the elite if a better antlion is discovered. Repeat until t = T and return the elite solution.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the single-objective Ant Lion Optimiser (ALO).

However, a problem can have multiple conflicting objective functions in energy systems. This will require a multi-objective optimisation approach to simultaneously generate viable solutions. The multi-objective antlion optimisation (MOALO), modelled after the multi-objective particle swarm optimisation (MOPSO), integrates a mechanism for archive management and leader selection. Solutions are selected from a pre-defined archive size to improve solution diversity. Using the niching technique, a specified radius is employed to study the area of each solution and count nearby solutions as a measure of distribution. This ensures well-spread solutions within the archive. MOALO adopts two strategies, like MOPSO, to further enhance the distribution of solutions.

Firstly, the antlion is selected based on the solution with the least crowded neighbourhood. Equation (19) determines the probability of selecting a particular solution from the archive [19].

- = constant value greater than 1

- = number of solutions in the neighbourhood for the ith solution.

The second strategy deletes solutions from the most crowded neighbourhood when the archive is full to make space for new solutions. Equation (20) is used to identify which solution is likely to be deleted from the archive.

Finally, Equation (15) needs to be modified for multi-objective problems. Equation (17) must also be modified to select a non-dominated solution from the archive on the simultaneous selection of antlions and elites.

The flowchart for the resulting mathematical model for multi-objective ALO is shown in Figure 5. From Figure 5, the MOALO variant balances exploitation and exploration while preserving diversity using an external archive. At each iteration, the parent antlion and elites are pulled from the archive by the roulette wheel selection. The ants take normalised walks around the selected antlion and the elite within adaptive bounds, advancing towards non-dominated regions. After each iteration, the newly found non-dominated solutions refresh and update the archive. When the archive is full, Equation (19) is used to prune densely packed members to preserve spread along the Pareto front. The algorithm terminates at t = T and returns the final nondominated archive, Pareto-optimal set.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimiser (MOALO).

2.6. Mathematical Formulation

The Ant Lion Optimiser (ALO) and its multi-objective version (MOALO) are utilised here to optimise the thermodynamic performance of a single-stage dual-bed silica-gel–water ADC. ALO and MOALO are modelled on the hunting techniques of antlions in sand pits. Equations (2), (4) and (6) represent the regression-based models for the Coefficient of Performance (COP), Cooling Capacity (), and Waste Heat Recovery Efficiency () [29]. ALO/MOALO employs a stochastic evolutionary approach that emulates ant–antlion interactions to explore and exploit the design space.

The single-objective formulation of ALO optimises each objective independently.

- COP maximisation:

Similarly, the optimisation of Cooling Capacity () is defined as:

- Cooling capacity maximisation:

- Waste heat recovery efficiency maximisation:

To preserve the diversity among solutions, MOALO extends the ALO framework by using Pareto dominance, elitism, and a crowding distance mechanism to converge toward a diverse and optimal set of non-dominated solutions.

The multi-objective formulation simultaneously combines the three objectives as Equation (24):

subject to the variable bounds:

- [°C]

- [°C]

- [°C]

- [kg s−1]

- [kg s−1]

- [kg s−1]

- [kg s−1]

- [W/K]

- [W/K]

- [W/K]

2.7. Rationale for Selecting MOALO

Since regression-based surrogate models are used to compute the three objectives (COP, , and , the optimisation is treated as a black-box, derivative-free, multi-objective problem. MOALO maintains an external archive of non-dominated solutions and applies density-based roulette wheel selection and deletion to keep the Pareto front well-distributed [19]. In addition, MOALO uses ALO-style random walks around selected antlions and elite solutions to balance exploration and exploitation with relatively few user-defined control parameters [19,41].

MOALO’s archive-driven diversity control differs from widely used optimisers like NSGA-II, which uses crowding distance to maintain diversity after non-dominated sorting [42], MOGWO, which uses a multi-leader hierarchy to update solutions [41] and MOPSO, which uses an external repository of leaders to guide particle flight [43].

Therefore, this study adopts MOALO to integrate directly with the regression-assisted ADC model, providing a diverse set of trade-off solutions along the Pareto front for informed decision-making.

3. Results

3.1. Single Objective Optimisation

The single-objective ALO algorithm implemented in this study was adapted from the original work by Mirjalili et al. [44] which is available online. The algorithm was tailored to the characteristics of the three objective functions, the selected decision variables and implemented on the MATLAB (R2021a, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) platform using a 64-bit operating system, an x64-based processor, 8 GB RAM, and a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-1255u CPU @ 1.70 GHz laptop.

Although the operating envelopes generated by ALO in this study are high, they are plausible given the sink and source temperatures and UA values. Depending on the design conditions, experimental single-stage silica-gel/water units generally report COP between 0.3 to 0.5 [45]. A review study on silica-gel water ADCs reported a COP of approximately 0.5–0.6 and beyond for optimised cases [46]. This validates the results from the SOO ALO of this study. The observed trends need not match the linear marginal coefficients since they reflect re-optimised Pareto set solutions.

The actions are to maximise each of the objectives discussed under setpoints, Loop flow controls, heat exchanger (HX) UA practices, and a prioritised sequence for constrained conditions.

3.1.1. Coefficient of Performance (COP) Maximisation

The ALO algorithm was employed to solve Equation (21) and determine the conditions for maximum COP, utilising the decision variables and values presented in Table 1. Table 2 displays the optimum decision variables to maximise COP, and . Based on the ALO Maximise COP solution from Table 2, the following actions can be adapted to interpret the optimiser’s choices into chiller-operable settings.

Table 2.

ALO single-objective optima for COP, and ; metrics on the right are the values for the same solution.

To achieve the optimal COP of 0.67412, the following control strategies were identified based on the direction of decision variables:

Setpoints to Target (COP Mode)

Moving the three temperature levers in the recommended favourable directions can immediately increase the COP.

- : increase toward 95 °C. Aim for the highest available driving temperature within limits [47].

- minimise as cold as practicable (around 22 °C) using a tower fan or flow [47].

- increase to around 20 °C. A warmer chilled water setpoint can reduce lift [48]

Water-Loop Flows Setpoints (COP Mode)

Driving the four water flow control loops towards the recommendations stated below can increase COP and UA effectiveness with diminishing returns. Flow meters with a Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controller to command the Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) speed can be used to achieve each ALO specified flow rate.

- : increase to around 2.20 kg s−1 for stronger regeneration [49].

- increase to around 2.20 kg s−1 for better bed-side heat transfer [28].

- : increase to around 1.40 kg s−1 for stronger evaporator duty [28].

- increase to approximately 2.20 kg s−1 to ease heat dissipation [49].

Thermal Conductance (UA) Operational Levers (COP Mode)

From Table 3, the ALO optimum shows high UA values. While UA is primarily design-fixed [28], effective UA depends on the following steps:

Table 3.

Trend of Decision Variables under ALO-Based SOO.

- maximise , , or operate closer to high UA values [50].

- Open all HX circuits, balance flows and keep filters clean.

- Defoul evaporator and condenser surfaces on schedule.

- Maintain high tower airflow and adequate cooling water velocity.

Metaheuristic algorithms are stochastic and can therefore yield different outcomes across independent runs. The single-objective ALO (SOO) results in Table 2 report the best solutions obtained from independent runs of the objectives and are included to show how each objective drives the decision variables under the stated run settings [51,52,53]. They should not be interpreted as an absolute bound on achievable performance for each metric. By contrast, the MOALO results form a Pareto set of non-dominated trade-offs, so solutions with higher may appear, typically at the expense of COP and/or , as expected in Pareto-based multi-objective optimisation [54,55].

Priority When Constrained (Most COP per Effort)

When it is impossible to achieve all targets (ambient and equipment limits), leverage the following steps for the biggest COP gain per step.

- : lower to make the sink colder and reduce the tower approach to the wet bulb.

- UA: increase all UA through cleaning HX or balancing flow.

- and Push and further. Although this could reduce , it can increase COP when sink and UA are in good shape.

- : Fine-tune . Too low will starve the evaporator duty, and too high will reduce Logarithmic Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD), so it is better to stay near the ALO target of around 1.4 kg s−1.

3.1.2. Cooling Capacity () Maximization

To identify the conditions for maximum , the ALO algorithm was used to solve Equation (24) with the decision variables and values from Table 1. Table 2 displays the optimum decision variables to maximise . To achieve a maximum of 18.2235 kW, the following variable adjustments depicted in Table 3 are required.

Setpoints to Target ( Mode)

Moving the three temperature levers in the recommended favourable directions can immediately increase the .

- : increase toward 95 °C. Aim for the highest available driving temperature within limits [47,56].

- minimise (around 22 °C) to reduce the condensation/adsorption process and boost [49,56,57].

- increase to around 20 °C. This will reduce the temperature lift to increase to its optimum [48,58].

Water-Loop Flows Setpoints ( Mode)

Driving the flow control loops towards the recommendations stated below can increase COP and UA effectiveness with diminishing returns.

- : increase to around 2.20 kg s−1 for stronger regeneration [49].

- increase to around 2.20 kg s−1 for better bed-side heat transfer [28].

- : increase to around 1.40 kg s−1 increases the evaporator effectiveness to improve up to diminishing returns [28,59].

- Although optima may exist, increasing to approximately 2.20 kg s−1 lowers the condensing temperature to enhance [49].

Thermal Conductance (UA) Operational Levers ( Mode)

From Table 2, the ALO optimum shows high UA values. While UA is primarily design-fixed [28], effective UA depends on the following steps:

- maximise , , or operate closer to high UA values [50].

Priority When Constrained (Most kW per Effort)

When it is impossible to achieve all targets (ambient and equipment limits), leverage the following steps for the biggest gain per step.

- : lower to reduce sink temperature [49,56,57].

- UA: increase all UA through cleaning HX or balancing flow.

- and Increase and within limits to enhance the drive heat and increase [47].

- and : Raise and to increase evaporator throughput and lower condenser temperature, respectively. It is advisable to keep close to the ALO target of around 1.4 kg s−1. This can directly increase [49].

3.1.3. Waste Heat Recovery Efficiency () Maximisation

Applying the ALO algorithm to Equation (23) with the decision variables and values from Table 1 yielded the results in Table 2. To achieve a maximum of 0.11829 requires the following set points.

Setpoints to Target ( Mode)

Moving the three temperature levers in the recommended favourable directions can immediately increase the .

- : reduce toward 65 °C with other favourable settings to increase . However, too low weakens desorption to reduce . This shows that to some extent, “higher is not always better” for and there exists an optimum.

- should be low enough to keep the sink cold and support desorption, but not weaken it (around 22 °C) [60].

- increase to around 20 °C. This will reduce the temperature lift to increase to its optimum [60].

Water-Loop Flows Setpoints ( Mode)

Combining the recommendations stated below with Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) and Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) speed flow meters can achieve each ALO specified flow rate to boost .

- : aim for moderate to high (2.198–2.20 kg s−1) to sustain desorption at the lower without “over-supplying” heat [47].

- aim for a moderate flow rate (around 1.658 kg s−1), just enough to maintain without increasing the drive heat and number of transfer units (NTU), diminishing returns [61].

- : increase to around 1.40 kg s−1 increases the evaporator effectiveness to improve up to diminishing returns [28,59].

- moderate to low (around 1.244 kg s−1) to maintain consistent heat rejection and higher [61].

Thermal Conductance (UA) Operational Levers ( Mode)

From Table 2, the ALO optimum shows high UA values. While UA is primarily design-fixed [28], effective UA depends on the following steps:

- and : Keep and high around 10,000 kW/k. Better HX effectiveness directly relates to increased cooling for the same drive heat, thereby increasing [61].

- : Optimum is just below maximum , so run only enough to increase the condenser NTU. Increasing beyond that will mainly reduce condenser temperature and increase heat dissipation without a commensurate rise in [61,62].

- Cleaning the condenser, adequate tube/channel velocity and balanced circuits can increase the effectiveness of UA without an excessive increment of the operating values.

Priority When Constrained (Most ηₑ per Unit Drive Heat)

When it is impossible to achieve all targets (ambient and equipment limits), leverage the following steps for the biggest gain per step.

- Enable a lower . Reduce the temperature lift by reducing and increasing [60]. Increasing (within process limits) increases evaporating saturation pressure/temperature to reduce lift. The resulting LMTD is enough to maintain or slightly increase evaporator duty without suppressing .

- Aim for between 65–75 °C at a minimum acceptable . Efficiency has been reported to peak at moderate temperature drives [47].

- Set at high, moderate, low to moderate and moderate to high to targets [59,61].

- Increase the effectiveness of UA through good housekeeping practices like opening all HX circuits to improve distribution, cleaning filters, descaling HXs to reduce fouling resistance and maintaining sensible water velocities to lift the Reynolds number [61,62].

3.1.4. Conflicts in Single-Objective Optima (ALO)

From Table 3, the linear surrogate models indicate a monotone direction. Under box constraints, maximising a single objective drives all the positively signed coefficients to their upper bounds while dragging down all the negatively signed variables to their lower bounds.

The SOO optima are mutually incompatible and different. Varying across its admissible bounds (65–95 °C) when holding other variables fixed, increased COP by +0.042 and Qcc by +9.32 kW, while decreasing by −0.009. This model-level antagonism necessitates an MOO approach to show a full Pareto front rather than isolating corner solutions.

Unlike MOALO, which constructs a Pareto front of all objectives [19], ALO conceals the continuous trade-off surface while exposing only the isolated extreme points of the decision variable bounds [37].

Table 3 reports the response model of the linear regression’s directional preferences of each objective at its single-objective optimum in maximisation form. An upward arrow, “↑” indicates that the objective increases when the variable moves towards its upper bound and a downward arrow “↓” implies there is an improvement when the objective moves towards its lower bound. The conflicts column shows consensus, “✓” when all three objectives have the same direction and “≠” indicates conflict when at least one objective goes the opposite direction (e.g., ↑, ↑, ↓). For this model, reduces but increases COP and Qcc, which is a conflict and requires a multi-objective (Pareto) treatment.

Table 3 confirms that the best way to maximise one objective (e.g., ) differs from the optimal direction to maximise another (e.g., COP or ) for certain decision variables like and . This implies that no single set of operating parameters can simultaneously maximise all three performance metrics. This necessitates determining the Pareto optimal solutions through multi-objective optimisation (MOO), such as the Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimiser (MOALO). Using MOALO goes beyond merely finding isolated optimal points for individual objectives; it identifies a set of non-dominated solutions that represent the best trade-offs among these competing performance metrics [19].

3.2. Multi-Objective Optimisation

The multi-objective antlion optimisation algorithm implemented in this study was adapted from the original work by Mirjalili et al. [63], which is available online. The algorithm was tailored to the characteristics of the three objective functions, the selected decision variables and implemented on the MATLAB platform using a 64-bit operating system, an x64-based processor, 8GB RAM, and a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-1255u CPU @ 1.70 GHz laptop.

The MOALO parameters in Table 4 were deliberately chosen according to the standard algorithm configuration of the MOALO/ALO original studies [19,37] and were kept constant throughout the optimisation runs. This was necessary to prevent tuning bias and keep the discussions on the resulting Pareto trade-offs generated from the coupling of MOALO with the regression-based ADC model.

Table 4.

Set values of the hyperparameters.

The set values of the hyperparameters, as proposed by Mirjalili et al. [37] n the original MOALO algorithm, are provided in Table 4.

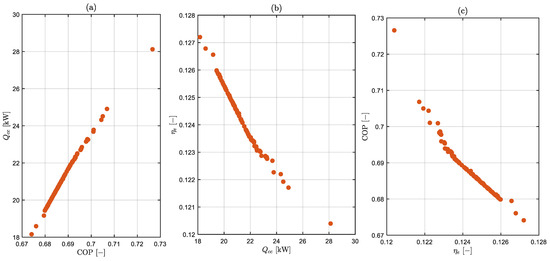

3.2.1. Pairwise Pareto Front Trade-Offs (2-D Projections)

Across the investigated bounds, the front is effectively one-dimensional (1-D) and collapses to form a ridge. Rather than a broad, multi-dimensional surface, the two-dimensional (2-D) plots show the data points as a narrow continuous linear curve. From Figure 6, panel (a) shows COP increases monotonically with , yielding an almost continuous linear curve, whereas is non-correlated with both capacity (panel b) and COP (panel c). Panels (b) and (c) show that reduces as either COP or increases, validating the plot in panel (a) and indicating a consistent trade-off between COP/cooling capacity and . Altogether, the three projections demonstrate that aiming for a higher COP and will be at the cost of and vice versa. A practical design compromise is seen near the intersections of panels (a) to (c), as a balanced region is identified around COP ≈ 0.695, ≈ 24 kW, and ≈ 0.122–0.123.

Figure 6.

Pairwise 2-D projections of the MOALO non-dominated set (N = 100). (a) COP versus ; (b) vs. ; (c) COP vs. .

3.2.2. Validation of Objective Models and Pareto-Front Quality

Within the explored bounds, the COP, , and fronts compress towards an effective 1-D manifold because the objectives co-vary with the same hot-side driving temperature potential and heat-transfer conductance (UA). The performance of classic silica-gel/water systems ADCs is significantly affected by heat and mass flow rates [64], and both the COP and cooling capacity are very sensitive to operating water temperatures [65]. This coupling inherently results in a ridge-shaped front geometry. Nevertheless, a ridge-shaped front is expected because the objectives are correlated and partially redundant due to the degeneration of the Pareto fronts for such regimes [66,67]. This is why the results are presented in 2-D rather than 3-D to ensure the plots are clear and free from occlusion for quantitative comparison [64,66]. The observed trends in the 2-D projections are physically plausible and internally consistent with the working of silica-gel/water systems ADCs. Cooling capacity increases as hot water (desorption) temperature rises until an optimum efficiency, after which COP may decline [47,68,69,70]. As noted earlier, observed trends reflect re-optimised Pareto sets and do not necessarily correspond to linear marginal coefficients; therefore, moving from one Pareto-optimal solution to another indicates a trade-off [71,72].

All reported Pareto data points meet the imposed bound limits (temperatures, mass-flow rates, and UA products) and basic thermodynamics constraints, as the approach temperatures are realistic and there are monotonic responses to driving temperature and heat transfer area. There are no remaining infeasible or dominated points after re-evaluation [47].

Table 5 summarises selected literature benchmarks for ADC performance and compares them with the MOALO Pareto set across COP, , operating temperatures and system scale with the gains and key limitations. The MOALO front yields COP from 0.674–0.716, around 18–27.3 kW, and operating temperature from 65–95 °C for , around 22 °C and 20 °C aligning with reported values [73,74,75,76]. Even though was derived from a prior formulation, it is seldom reported as a performance metric in ADC optimisation. It is therefore reported explicitly for this MOALO Pareto solutions within the explored bounds as 0.118–0.1275 (11.8–12.75%) to provide a direct measure of utilisation of waste heat for design and comparison. The reported ranges of add useful context for future waste-heat integration studies while remaining consistent with the underlying thermodynamics principles. Overall, the reported literature aligns with the results from this study and supports the quality of the generated MOALO Pareto set and the reliability of the objectives.

Table 5.

Comparison of literature benchmarks studies for single-stage silica-gel/water ADCs versus this study’s MOALO compromise with gains and key limitations.

3.2.3. Selecting Pareto-Optimal Solutions and Implementation Considerations

Selecting Pareto-Optimal Solutions for Application Scenarios

Rather than generating a single “best” design, the MOALO results provide a set of non-dominated trade-off solutions. In practice, choosing a specific solution should be guided by the application priorities and constraints. A simple and transparent procedure is as discussed:

- Use practical thresholds to filter the Pareto set. This reduces the many Pareto set points into a manageable subset of feasible candidate solutions.

- Select a preferred solution from the filtered subset based on the stakeholder’s priorities and operating context. That is prioritising higher when cooling demand is dominant, or prioritising higher when waste-heat utilisation is the main objective.

- Select a knee/compromise solution if no clear preference exists, since knee solutions represent an efficient compromise beyond which improving one objective further leads to a disproportionate deterioration in another [79,80].

Feasibility of Optimised Parameters and Engineering Implementation

Interpretation of the optimisation findings should be restricted to the decision variable bounds reported in Table 1. The thermal conductance terms () represents a lumped heat-transfer capacity and maps to design choices to be implemented through , (is the overall heat-transfer coefficient and is the heat-transfer area) [81]. In practice, achievable is limited by exchanger geometry/size, material selection, fouling allowance, flow regime, pressure-drop, as well as maintenance and cost constraints [81] The optimised water mass-flow rate values correspond to pump operating setpoints in the hot-, cooling-, chilled-, and condenser-water loops. There is a need to verify and ensure that pressure drop and parasitic pumping power remain acceptable in detailed component design analysis before deployment [81].

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of the MOALO results, a One-at-a-Time (OAT) approach sensitivity analysis (SA) was conducted to examine the impact of each decision variable on COP, , and . One variable was swept across the lower, midpoint, and upper bounds, while all other variables were held at their baseline values. For each OAT setting, the optimiser was re-run for twenty independent runs using the same hyperparameters to obtain a stable Pareto set [43,82]. After each run, the resulting non-dominated cloud of Pareto-optimal points for the objectives was summarised, with cubic polynomial fits. The trends are reported as three projections: against COP, against COP and against .

Although the OAT protocol provides a transparent robustness check, it does not explicitly quantify the effects of interaction between decision variables. For this reason, the trends reported should be interpreted as compensated design responses obtained by re-optimising the non-focal variables at each lever level, rather than as fixed-point local sensitivities [83,84,85].

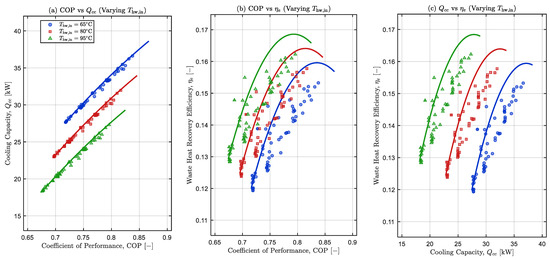

3.3.1. Effects of Varying Hot Water Inlet Temperature

Figure 7 illustrates the effects of on the Pareto set. Three levels are shown as 65 °C (low, blue circles), 80 °C (intermediate, red squares), and 95 °C (highest, green triangles). The markers represent the non-dominated solutions, and smooth curves are cubic fits drawn to guide the eye. In panel (a), COP increases with . across all Thwin. This shows a positive correlation between COP and . within the explored bounds, consistent with prototype and bench tests of silica-gel/water units [77,86].

Figure 7.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to hot-water inlet temperature, . Panels: (a) . versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

For panels (b) and (c), shifts upwards as rises. Higher usually improves the desorption process and increases the useful cooling per unit bed up to an intermediate optimum beyond which gains decline [77,87]. The –COP relation is a concave curve with a maximum occurring at a COP between 0.78 and 0.82, in line with the reported optimum driving temperature behaviour for silica-gel/water systems ADCs [77,88].

Panel (c) suggests diminishing returns in waste heat utilisation as initially increases with higher ., then saturates more prominently at 80–95 °C. Literature confirms that the performance of declines beyond an optimum driving force at larger throughput [25,77]. Practically, datasheet operating windows support the use of 65–95 °C for ADCs and highlights performance flattening at the upper end [89].

Within the MOALO envelope, if maximising waste heat utilisation is the priority, then the ADC should be operated at a higher (80–95 °C) around the intermediate COP region where peaks, as specified by the datasheet operating windows [89]. If cooling capacity is the main requirement, a trade-off is observed in panel (c) for and . Thus, 65 °C can deliver a higher at the expense of . Depending on the available source temperature, this study offers a balanced compromise around a COP of 0.80, with . between 28–34 kW and , 0.150–0.170 at 95 °C.

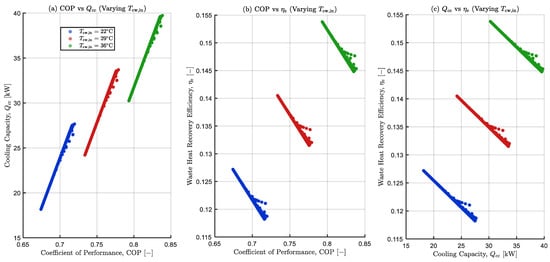

3.3.2. Effects of Varying Cooling Water Inlet Temperature on the Pareto Set

Figure 8 illustrates the effects of on the Pareto set. Three OAT levels are shown as 22 °C (low, blue circles), 29 °C (intermediate, red circles), and 36 °C (highest, green circles). The markers represent the non-dominated solutions from re-optimised runs. In panel (a), . increases alongside COP for every within the explored bounds. clearly separates the Pareto clouds. The MOALO optimiser adjusts the other degrees of freedom to compensate so the highest COP and . are observed at 36 °C, followed by 29 °C and 22 °C. In most fixed envelope silica-gel/water ADCs experimental settings, increasing usually degrades . and COP, so the ordering of here reflects re-optimisation rather than a universal law [73,88,90,91].

Figure 8.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to cooling water inlet temperature,Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

In panel (b), a negative correlation is observed within each level. decreases as COP rises. The MOALO optimiser compensation shifts the entire COP curve upwards across all levels (36 °C > 29 °C > 22 °C). Under fixed conditions, increasing is generally detrimental to the performance of the ADC [73,88,90]. The observed trends are specific to the explored bounds and OAT protocols, where the optimiser reallocates other variables as varies. From panel (c), higher corresponds to higher across all levels, while decreases with .

Again, in these OAT runs, the MOALO optimiser adjusts responses to changes in Thus, fixed-setting studies will report the opposite ordering when other variables are held constant [73,88,90,91]. These trends highlight the practical limitations and sensitivity to sink conditions as indicated in the datasheet windows [74,75,89].

In this MOALO envelope, a balanced design compromise is observed around COP 0.79–0.82, with . between 31 and 38 kW and approximately 0.140–0.155.

3.3.3. Effects of Varying Chilling Water Inlet Temperature on the Pareto Set

Figure 9 illustrates the effects of on the Pareto set. Three OAT levels are shown as 10 °C (low, blue circles), 15 °C (intermediate, red circles), and 20 °C (highest, green circles). The markers represent the non-dominated solutions from re-optimised runs, and no curve fits are shown. In panel (a), . and COP increase together across all levels of . The fronts are ordered by . The highest 20 °C (blue), shows the highest COP–, followed by 15 °C (red) and 10 °C (green). This ordering aligns with the behaviour of silica-gel/water ADC under fixed settings, where both COP and . improve due to a reduction in temperature lift from warmer chilled water law [73,77,90].

Figure 9.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to cooling water inlet temperature,. Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

For panel (b), slightly decreases as COP increases within each level. Across levels, lower temperature lifts improve heat utilisation at the hot side, so higher swings the whole COP band upwards (20 °C > 15 °C > 10 °C) [73,88,90]. In panel (c), warmer chilled water produces higher values, while decreases with COP for each level of . Similar shifts and sensitivity of returning/leaving chilled water temperatures are documented in manufacturer datasheets [74,75,89].

For this MOALO study, the Pareto front is favourable for processes that can accept chilled water at higher temperatures to produce higher COP, . and . However, expect a reduction in the COP and values if the requirement is a strict = 10 °C set point. Within the explored bounds of this study, a practical compromise lies around a COP of 0.80, with 29–35 kW and 0.145–0.158.

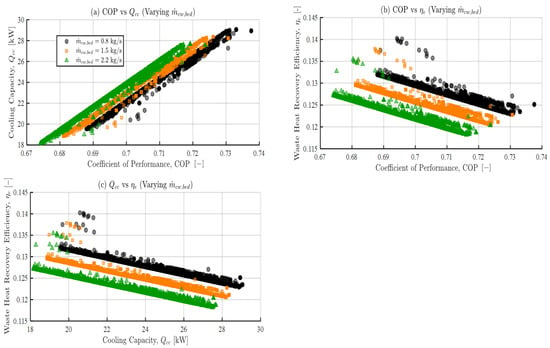

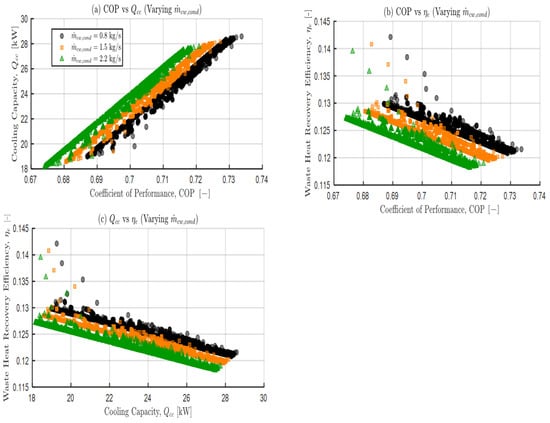

3.3.4. Effects of Varying Hot Water Inlet Mass Flow Rate on the Pareto Set

Figure 10a–c reveals how changing the hot water mass flow rate () at three different levels, 0.8 kg s−1 (black circles), 1.5 kg s−1 (orange squares), and 2.2 kg s−1 (green triangles), affects system performance. Panel (a) shows the COP against . across the tested flow rate range. The upper part of the plot is predominantly occupied by the highest-flow set ( = 2.2 kg s−1, green triangles), suggesting a strong, positive linear correlation between COP and , while the lowest-flow set ( = 0.8 kg s−1, black circles) lies lower. However, the three MOALO clouds are tightly clustered.

Figure 10.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to cooling water inlet temperature, . Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

This indicates that the hot water mass flow rate has weak leverage on the core COP–. performance within the tested envelope. This agrees with Kalawa et al. [92], who found that increasing the mass flow rate marginally improves COP/, albeit improving operational stability.

Theoretically, higher improves heat transfer and desorption rate in silica-gel–water ADC systems [30]. However, these MOALO optimisers likely compensate via other degrees of freedom, resulting in the observed weak sensitivity. Panel (b) shows against COP, and panel (c) against . The plots show clear stratification based on the flow rate. decreases as COP or . increases within each flow rate level. There is a significant monotonic decline in ηₑ as increases across each level (: 0.8 > 1.5 > 2.2 kg s−1). Theoretically, a higher quickens the desorption process, resulting in a faster cooling cycle and potentially better cooling performance [30]. Nevertheless, they can also intensify irreversibilities and increase entropy generation, leading to losses in useful energy that decrease the quality of ηₑ [93]. This results in a trade-off: modest COP or gains at high at the cost of lower . These trends mirror reoptimised solutions and are specific to this envelope. Operate at a lower when waste heat is costly or limited to maintain a high at a smaller . A higher is preferable if is the limiting factor, but expect a lower . A practical compromise for a reasonable . and moderate is to use the mid-flow level (1.5 kg s−1) near the mid-COP region.

3.3.5. Effects of Varying Bed Cooling Water Mass Flow Rate on the Pareto Set

Figure 11a–c show the effects of bed cooling water mass flow on the Pareto set at three levels: 0.8 kg s−1 (black circles), 1.5 kg s−1 (orange squares), and 2.2 kg s−1 (green triangles). Markers represent non-dominated solutions.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to cooling water inlet temperature,. Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) against COP shows an improvement in the ADC’s primary cooling performance as increase. The lowest performance occurs at the lower region ( = 0.8 kg s−1), while the highest-flow band ( = 2.2 kg s−1) occupies the upper region, with a COP up to 0.73 and around 28.5 kW. This is thermodynamically reasonable, as a higher bed cooling water mass flow facilitates effective removal of adsorption heat. This reduces the bed pressure during adsorption and maintains vapour uptake to increase throughput. Consequently, COP increases with but with diminishing returns at higher flow rates [30].

Conversely, panels (b) against COP and (c) against shows a decrease in waste heat efficiency (ηₑ) at higher both within and across all levels. Maximum occurs at the lowest flow rate (0.8 kg s−1), while the highest flow rate (2.2 kg s−1) results in the lowest ηₑ. At higher mass flow rates, the cooling water stream effectively dissipates more heat, but this increases irreversibilities too. Therefore, the quality of waste-heat utilisation falls even if improves [30,93].

For these MOALO settings, increasing or decreasing can maximise or reduce or , respectively. Therefore, choose based on the required design outcome. A balanced compromise occurs at the intermediate flow case ( = 1.5 kg s−1) around mid-COP between 0.70–0.72 for a moderate with only a slight drop in .

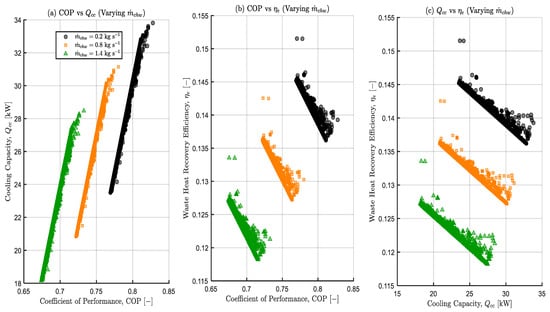

3.3.6. Effects of Varying Chilled Water Inlet Mass Flow Rate on the Pareto Set

Figure 12a–c show the effects of chilled water mass flow on the Pareto set at three levels: 0.2 kg s−1 (black circles), 0.8 kg s−1 (orange squares), and 1.4 kg s−1 (green triangles). Markers are non-dominated solutions.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to chilling water mass flow, . Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) shows against COP. The lowest (0.2 kg s−1) corresponds to the highest COP values (0.78 to 0.83) and the highest (28 to 32 kW). The intermediate (0.8 kg s−1) shows mid-point values for both COP and and the least COP and values are observed at high (1.4 kg s−1). Although increasing generally improves heat transfer, the plots show the existence of a low to mid flow optimum on the evaporator side and going beyond that can have detrimental effects on the off-design operation of the components. Sah et al. reported a near-flat trend of performance metrics at higher chilled water flow rates and improvement at low to moderate flow rates, indicating diminishing returns and an implied optimum [57].

Panels (b) show against COP and (c) against . An inverse relationship is observed between and COP or within each level. decreases as COP or increases. Raising the chilled-water flow from 0.8 to 1.4 kg s−1 produced a lower COP and Qcc. This is due to operating beyond the evaporator-side optimum, where the bedside heat/mass-transfer limits the performance. Beyond the optimal operating conditions, the effective LMTD/residence time reduces, declining evaporative duty per cycle as increasing flow rate causes a marginal rise in thermal conductance. This behaviour is consistent with the finite time module and bed transport limits characteristics of adsorption modules [61,94] and saturation of gains at higher mass flow rates [20].

Within the explored bounds, choosing low to mid when COP and are the priorities that can preserve . However, operating at very pushes the ADC beyond the evaporator-side optimum and penalises both COP and . Practically, a balanced compromise will be to run at 0.8 kg s−1 close to COP of 0.76–0.80.

3.3.7. Effects of Varying Condenser Cooling Water Mass Flow Rate on the Pareto Set

Figure 13a–c show the effects of condenser-cooling mass flow on the Pareto set at three levels: 0.8 kg s−1 (black circles), 1.5 kg s−1 (orange squares), and 2.2 kg s−1 (green triangles). Markers are non-dominated solutions, and other variables are held at baseline and reoptimised.

Figure 13.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to condenser cooling water mass flow, . Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) against COP. A clear positive coupling is observed for and COP. Increasing shifts the entire cloud upwards and increases with COP. An increase in improves heat dissipation from the condenser and reduces the average condensing temperature (smaller lift). This raises the at a given COP. A modest separation is identified with diminishing returns at the highest This is consistent with off-design limits and sink-side improvements characteristics for silica-gel/water ADCs [73,90].

Panel (b) shows against COP, and (c) against . An inverse relationship is seen for and across all levels, while decreases with COP or as increases within each level.

Similar to the case, rejecting more heat in the sink increases entropy generation and thus, the quality of waste heat used falls while COP or improves [57,73,93].

If is the ADC’s priority, then a higher is beneficial, and if is the main requirement, then a lower is most preferable. Within the explored envelope, operating at mid flow (1.5 kg s−1) near the mid COP is a good compromise, which gives higher at a moderate penalty.

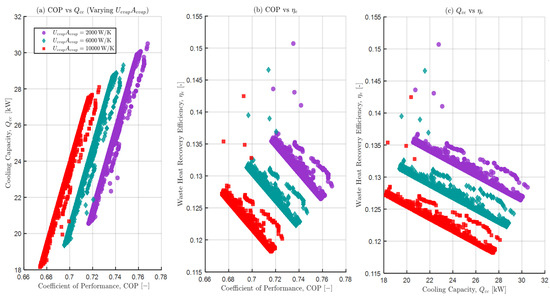

3.3.8. Effects of Varying Bed Overall Conductance on the Pareto Set

Figure 14a–c show the effects of overall bed thermal conductance on the Pareto set at three levels: 2000 W/K (low, purple circles), 6000 W/K (mid, teal diamonds), 10,000 W/K (high, red squares). Markers are non-dominated solutions, and other variables are held at baseline and reoptimised for each level.

Figure 14.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to bed overall conductance, Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) shows against COP. The three bands are almost parallel and increasing shifts the cloud up and to the right to yield a higher COP at a given and a higher at a given COP. Physically, a higher UA increases the effectiveness of removing heat of adsorption.

This improves regeneration and reduces bed temperature during adsorption and temperature swings during desorption to increase the cycles’ and COP [30,69,73,95].

Panel (b) shows against COP, and panel (c) shows against . Within each lever, reduces as COP or rises but increases monotonically with across all levels. Larger UA reduces the temperature approach differences, thereby reducing irreversibilities and improving the quality of heat utilisation [93,95,96].

However, the spacing between each band narrows at high , suggesting internal limitations and diminishing of gains once the external HX resistance reduces [30,97].

Within the explored bounds, increasing raises COP, and until internal limits set in. Practically, a balanced compromise will be at the mid to high range of 6000–10,000 W/K near the mid-COP region, which yields high with a good . Pushing above 10,000 W/K only improves slightly relative to the size and/or cost constraints.

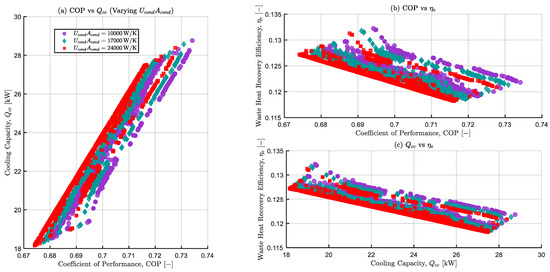

3.3.9. Effects of Varying Condenser Overall Conductance on the Pareto Set

Figure 15a–c illustrate the influence of condenser overall conductance on the Pareto set at three levels: 10,000 W/K (low, purple circles), 17,000 W/K (mid, teal diamonds), 24,000 W/K (high, red squares). Markers represent non-dominated solutions, with other variables held at baseline and reoptimised for each level.

Figure 15.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to the condenser overall conductance, . Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) shows against COP. The plots reveal three nearly parallel bands that shift upward and to the right as increases. COP slightly improves for a given , while significantly increases for a given COP. Higher condenser UA reduces heat rejection, lowers the mean condensing temperature, and raises both and COP [30,69,95]. The narrow spacing between bands at high indicates diminishing returns.

Panel (b) depicts versus COP, and panel (c) shows against . In each band, decreases as COP or rises. An inverse relationship exists between and , because increasing results in more heat being dumped into the sink, raising entropy generation. Therefore, although improves, the quality of waste heat utilisation () declines [93,95].

When cooling capacity is paramount, a higher is the optimal choice. Conversely, if waste heat utilisation is the priority, low to moderate should be preferred to preserve . For this envelope, if the design requires high with a moderate penalty on , around 17,000 W/K near the mid COP region would be a good compromise.

3.3.10. Effects of Varying Evaporator Overall Conductance on the Pareto Set

Figure 16a–c illustrate the influence of evaporator overall conductance on the Pareto set at three levels: 2000 W/K (low, purple circles), 6000 W/K (mid, teal diamonds), 10,000 W/K (high, red squares). Markers are non-dominated solutions, with other variables held at baseline and re-optimised for each level.

Figure 16.

Sensitivity of the Pareto set to evaporator overall conductance Panels: (a) versus COP; (b) versus COP; (c) versus .

Panel (a) shows three nearly parallel bands that shift upward for against COP as decreases from 10,000 W/K to 6000 W/K to 2000 W/K. That is, for a given , there is a moderately higher COP, and for a given COP, there is a noticeably higher at lower . This implies that within this envelope, the evaporator is not the active bottleneck after re-optimisation, but MOALO compensate by reallocating the high-side temperatures and flow rates (other degrees of freedom) for a slightly lower COP and at higher . A higher usually raises the evaporation temperature (reduces lift) to increase [30,69,95].

Panel (b) is against COP. reduces as COP increases within each band in the order of 2000 W/K, 6000 W/K and 10,000 W/K across the band. High increases throughput and total heat dissipated to the sink, but raises irreversibilities, which lowers the quality of waste heat utilisation [93,95].

Panel (c) displays against , following the same pattern as panel (b). decreases as increases within the bands across all levels. This reveals the inherent trade-offs between and . Raising to 10,000 W/K results in diminishing returns on the re-optimised Pareto front due to compensation. Thus, a good compromise for this OAT envelope is lower to mid (2000–6000 W/K) near the mid COP region for a higher at a comparatively higher

3.4. Critical Assessment of the Proposed Technology

3.4.1. Quantitative Advantages

One main advantage of this proposed regression-assisted MOALO framework is that the identified operational envelope considerably exceeds the reported benchmark configurations for similar single-stage silica-gel/water ADCs.

The optimised solutions (COP = 0.675–0.717) imply a performance uplift of roughly 35–139% based on endpoint constraints when compared to experimental baselines for single-stage silica-gel/water chillers (COP ≈ 0.3–0.5) [90,98]. The corresponding efficiency uplift is approximately 13–43% (endpoint bounds) when compared to theoretical review benchmarks (COP ≈ 0.5–0.6) [99,100].

Also, a cooling-capacity envelope of Qcc = 18.3–27.5 kW is produced after optimisation with a viable compromise close to Qcc ≈ 24 kW. Table 5 summarises the modelled framework’s potential to provide higher cooling output, which exceeds the upper bound of the benchmarked product class (≈20 kW) [101].

3.4.2. Disadvantages and Implementation Difficulties

Despite the thermodynamic gains, this technology may face hurdles to be deployed commercially due to the following challenges:

- There is a need for variable-frequency drives (VFDs) and advanced feedback control loops to precisely regulate and maintain flow rates and inlet temperatures near the specified optima to achieve the Pareto-optimal results. This will increase system control complexity and cost compared to operating with a standard on/off valve [102].

- Compared to MVC systems, ADCs have a lower specific cooling power. This means that although the optimised envelope improves the capacity-to-volume ratio for this study, it will be a challenge to apply it to space-constrained applications due to limitations with the physical volume of the silica-gel beds and associated heat exchangers [21].

- Results from the sensitivity analysis show the extreme sensitivity of the proposed framework to cooling water temperature. Performance degrades rapidly if the heat-rejection sink cannot sufficiently sustain low temperatures near the design point (22–30 °C), limiting the applicability of this technology in hot climates where wet bulb temperatures are high or in situations where cooling-tower performance is constrained [103].

3.4.3. Practical Limitations

The key practical limitations and boundary conditions of the proposed regression-assisted MOALO framework, particularly regarding surrogate-model validity and the persistence of multi-objective trade-offs under real operating constraints, are presented under this subsection as follows:

- The validity of this surrogate model is confined to the explored operating bounds used to generate the underlying data. Thus, experiments and physically constrained models are required outside the specified envelope [104].

- Robust instrumentation and multi-loop implementation of the inlet temperature, mass flow rates and other dominant parameters are necessary before implementation [102].

- Some effective conductance terms (UA values) can be design-fixed in hardware and can also be degraded by heat-exchanger fouling. As such, they may require consistent routine maintenance actions rather than changing their set-point [105,106].

- Depending on the selected Pareto solution, improving COP or can reduce due to the nature of multi-objective trade-offs. However, in practice, effective UA levels can be attained and sustained by maintaining a stable inlet temperature and cleaning heat-exchanger surfaces.

4. Conclusions

This study developed a computational framework to improve the performance of a silica-gel–water single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller using Antlion Optimiser (ALO) and Multi-Objective Antlion Optimiser (MOALO). Although and COP have similar mathematical forms, is treated here as a source-oriented waste-heat utilisation (recovery) metric to complement COP and in decision-making for low-grade heat-driven applications.

- MOALO produced a set of non-dominated trade-off solutions and identified key decision variables influencing the performance of a single-stage dual-bed ADC. These included inlet temperatures, heat-exchanger thermal conductance terms () and loop and mass flow rates.

- The non-dominated solutions produced by ALO and MOALO provide actionable trade-offs to enhance performance with COP ranging from 0.674–0.716, from roughly 18.3–27.5 kW, and reaching an approximated maximum range of 0.131.

- Relative to the selected benchmark reference point (COP ≈ 0.695 and ≈ 24 kW), the compromise solution corresponds to approximately 16% higher COP and 20% higher .

- Across objectives, , , and heat exchanger conductance ( and ) emerged as the most influential levers within the studied envelope.

- A brief selection guide was provided as a quick reference on how to use the Pareto set: filter solutions using application constraints, then select a context-appropriate trade-off per design priority or a knee/compromise solution when preferences are not explicit.

- Engineering implementation considerations were also clarified: the optimised terms represent lumped heat-transfer capacity () which needs to be checked against feasible component sizing, pressure-drop limits, fouling allowance, and maintainability, while optimised mass-flow rates require verification of pumping power and allowable pressure drop in detailed component design.

- Overall, treating COP, , and as co-equal objectives explicitly capture the design trade-offs between cooling delivery and waste-heat utilisation within the operating envelope of the surrogate models. Thus, the regression-assisted MOALO framework may serve as a useful and practical digital technology for configuring low-grade heat ADCs and could be extended to other sustainable cooling processes.

Limitations and Future Work