Abstract

Yttrium oxide (Y2O3) has emerged as a key material for advanced solar-blind ultraviolet (SBUV) photodetectors, attributable to its large bandgap energy (~5.5 eV), high dielectric constant, excellent silicon compatibility, and robust thermal stability. To precisely tune its optical bandgap for optimal alignment with the intrinsic solar-blind region, this study prepared Y1.5In0.5O3 ternary alloy films via co-sputtering, achieving an optimized bandgap of 4.70 eV. After optimizing the photosensitive layer, we fabricated a self-powered Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3/p-GaN back-to-back heterojunction SBUV photodetector was fabricated based on the optimized photosensitive layer. Under photovoltaic operation (0 V), the resulting device exhibited impressive performance metrics: a narrow spectral response (FWHM ~50 nm), quick rise/decay times of 30 and 75 ms, respectively, and high operational durability (less than 0.8% photocurrent degradation over 100 cycles). The detector also maintained a low noise current level (2.95 × 10−12 A/Hz1/2 at 1 Hz) and a low noise-equivalent power (NEP) of 4.42 × 10−9 W/Hz1/2, indicating high sensitivity to weak optical signals. These results establish YxIn2−xO3 ternary alloy as a viable material platform for SBUV detection and provide a new design strategy for developing highly sensitive, low-noise and spectrally selective ultraviolet photodetectors.

1. Introduction

Solar-blind ultraviolet (SBUV, 200–280 nm) photodetectors have seen growing interest over the past few years owing to their intrinsic insensitivity to solar radiation and high selectivity toward deep-UV light [1,2,3]. These features are critical for applications in missile tracking, flame detection, secure space communication, and environmental monitoring [4,5,6,7]. Unlike conventional UV detectors that suffer from parasitic visible and near-UV responses, SBUV photodetectors operate without external optical filters, thereby achieving high signal-to-noise ratios and superior detection accuracy under complex illumination environments [7,8,9,10,11]. To realize such devices, the active materials should exhibit wide bandgaps within the solar-blind spectral range (4.4–6.2 eV), together with high responsivity, fast temporal response, exceptional spectral selectivity and high operational durability.

Over the past decade, several wide-bandgap semiconductors have been explored for SBUV detection, including diamond [12,13], AlGaN [14,15], and MgZnO alloys [16,17]. Although these materials have achieved remarkable progress, each suffers from intrinsic limitations. Diamond photodetectors are hindered by high synthesis costs and defect-related issues [18]. AlGaN offers a tunable bandgap but demands high-temperature epitaxial growth and faces lattice mismatch challenges with common substrates, which hinder scalable fabrication [15]. Similarly, MgZnO alloys can extend the absorption edge into the solar-blind region but are prone to phase segregation, poor thermal stability, and limited compositional control [19,20,21]. These challenges underscore the need for alternative material systems that combine bandgap tunability, structural stability, and fabrication compatibility.

Yttrium oxide (Y2O3) has recently emerged as a compelling candidate for SBUV photodetectors due to its wide bandgap (~5.5 eV), high dielectric constant, outstanding thermal stability, and chemical robustness [22,23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, Y2O3 exhibits excellent compatibility with silicon and III-nitride semiconductors, allowing for versatile integration into existing microelectronic and optoelectronic platforms [27,28,29]. Nevertheless, the fixed bandgap of binary Y2O3, while within the solar-blind range, is not optimally aligned with the lower-energy edge of the atmospheric transmission window, potentially limiting photon absorption efficiency and responsivity for the longest usable SBUV wavelengths. Fine-tuning the optical bandgap of Y2O3 while preserving its crystalline stability and favorable dielectric properties is essential for achieving efficient solar-blind detection.

Ternary oxide alloys offer a powerful strategy for bandgap engineering, enabling systematic modulation of electronic structure and optical properties of wide-bandgap materials [30]. By introducing cations with smaller bandgaps into the Y2O3 lattice, one can achieve continuous bandgap tunability, improved carrier transport, and tailored defect states. Indium oxide (In2O3), with a smaller bandgap (~3.6 eV) and a similar cubic structure, is an ideal candidate for alloying with Y2O3 [31,32,33,34,35,36]. The underlying mechanism lies in the band alignment: as the Y/In ratio varies, the conduction band minimum shifts significantly while the valence band maximum remains relatively stable, thereby enabling continuous bandgap modulation. The formation of YxIn2−xO3 ternary alloys can bridge the bandgap between Y2O3 and In2O3, enabling precise tuning within the solar-blind range while retaining excellent crystallinity and stability. Moreover, such ternary oxide systems offer a promising pathway to overcome the limitations of conventional binary semiconductors by combining the merits of both a wide bandgap and improved electrical transport characteristics.

In this work, we report the controllable synthesis of YxIn2−xO3 ternary alloy thin films via a co-sputtering process, achieving precise composition and bandgap modulation. Based on the optimized material, a self-powered Pt/YxIn2−xO3/p-GaN back-to-back heterojunction SBUV photodetector was fabricated. Operating at 0 V bias, the device exhibits rapid response (rise/decay times of 30/75 ms) and excellent stability, with less than 0.8% photocurrent degradation over 100 cycles. Furthermore, the photodetector demonstrates an ultralow noise current of 2.95 × 10−12 A/Hz1/2 at 1 Hz and a low noise-equivalent power (NEP) of 4.42 × 10−9 W/Hz1/2, indicating exceptional sensitivity to weak optical signals. This work validates YxIn2−xO3 as a robust and tunable material platform for high-performance, low-noise SBUV photodetection and introduces a heterojunction design paradigm that synergizes bandgap-engineered absorption, built-in potential-driven charge separation, and intrinsically low dark current.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate Pre-Treatment

To obtain clean substrate surfaces, p-Si, p-GaN, and quartz pieces were ultrasonically cleaned in acetone, ethanol, and ultrapure water for 10 min each, followed by drying with high-purity nitrogen gas.

2.2. YxIn2−xO3 Film Deposition

YxIn2−xO3 ternary alloy thin films were fabricated on cleaned substrates using radio-frequency (RF) magnetron co-sputtering. The source materials were high-purity (99.99%) Y2O3 and In2O3 ceramic targets. To modulate the film stoichiometry, the Y2O3 target power was kept constant at 150 W, whereas the In2O3 power was varied (20 W, 30 W, 40W). The deposition was carried out for 120 min at ambient temperature, under a constant chamber pressure of 0.5 Pa. The working atmosphere was Ar (20 sccm) and O2 (5 sccm).

2.3. Photodetector Fabrication

An ultra-thin Pt layer was first deposited onto the YxIn2−xO3 film surface through a shadow mask by sputtering, serving as the photocarrier collection window (deposition parameters: power 50 W, duration 30 s, working pressure 0.5 Pa, Ar flow rate 30 sccm). Subsequently, a thicker Pt electrode was sputtered onto the ultra-thin Pt layer using a second mask under identical conditions, except for an extended deposition time of 3 min. For the bottom contact, an indium ohmic electrode was bonded to the p-GaN substrate.

2.4. Material and Device Characterization

Surface and cross-sectional morphologies were examined using a ZEISS Sigma 300 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Elemental distribution and quantitative composition analysis were performed via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) attached to the SEM system. The ultraviolet–visible transmission spectra of the films was recorded using a Shimadzu UV-2600i spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), and the optical bandgap was calculated by the Tauc plot method. Three-dimensional surface topography and root-mean-square (RMS) roughness were assessed by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Dimension Icon, Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The spectral responsivity of the fabricated devices was calibrated using a Zolix DSR500 system (Zolix Instruments Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The optoelectronic properties, including current–voltage (I-V) characteristics and photoresponsivity, were measured with a Keithley 4200A-SCS parameter analyzer (Keithley Instruments, Solon, OH, USA). Low-frequency noise measurements were conducted using a PRIMARIUS FS-Pro semiconductor parameter analyzer (Primarius Technologies, Shanghai, China). Steady-state and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectra were acquired using an Edinburgh Instruments FLS1000 spectrophotometer (Edinburgh Instruments, Livingston, UK). Unless otherwise specified, films for structural characterization such as SEM and AFM are deposited on Si substrates, films for UV-Vis characterization are deposited on quartz substrates, and films for constructing SBUV photodetectors and subsequent photoelectric performance tests are fabricated on p-GaN substrates.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Precise Bandgap Engineering and Microstructural Analysis

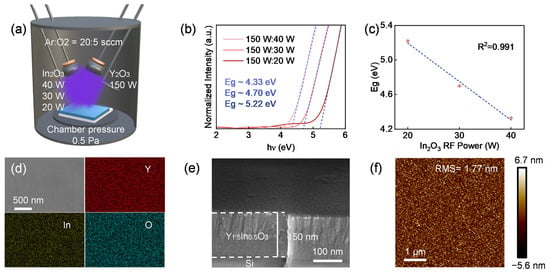

As schematically illustrated in Figure 1a, with the sputtering power of Y2O3 fixed at 150 W, a series of YxIn2−xO3 ternary alloy films with varying compositions was successfully fabricated by regulating the sputtering power of the In2O3 target to 20 W, 30 W and 40 W via RF magnetron co-sputtering. The UV-Vis transmission spectra of all films are presented in Figure S1. The optical bandgap values under each condition were derived from the Tauc plot method with the following equation [37], as summarized in Figure 1b.

where α is the absorption coefficient, hν is photon energy, and A is a material-dependent. The bandgap Eg was obtained by the linear fitting of the curves and extrapolating to (αhν)2 = 0. Notably, as shown in Figure 1c, the optical bandgap of the YxIn2−xO3 films exhibits a clear linear increasing trend with rising In2O3 sputtering power. This trend indicates that incorporating In2O3 effectively modulates the bandgap continuously (the specific mechanism is shown in Figure S2), thereby confirming the feasibility and effectiveness of the co-sputtering technique for precise bandgap tuning in wide-bandgap oxide semiconductors. To achieve efficient detection in the SBUV region, we selected the film deposited with an In2O3 sputtering power of 30 W, which possesses a bandgap value of 4.70 eV and an absorption edge located within the SBUV range, as the photosensitive absorption layer. The transmittance of this film in the 200–280 nm wavelength range is between 10.2% and 77.3%, indicating strong absorption characteristics suitable for SBUV photodetector applications. The surface morphology, elemental distribution, and chemical composition of the selected films were systematically investigated using SEM and EDS mapping. The corresponding results are compiled in Figure 1d. SEM images reveal that the film surface is uniform and dense. EDS elemental mapping confirms the homogeneous spatial distribution of Y, In, and O throughout the film. Combined with the quantitative EDS analysis provided in Figure S3, the atomic ratio of Y to In was determined to be approximately 3:1, suggesting the chemical composition can be accurately represented as Y1.5In0.5O3. The cross-sectional SEM image of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film (Figure 1e) further demonstrates its compactness and structural uniformity. The measured thickness is about 150 nm, sufficient to ensure effective absorption of incident SBUV radiation. Furthermore, AFM measurements (Figure 1f) indicate a RMS roughness of only about 1.77 nm, highlighting the excellent surface flatness of the film, which provides an ideal substrate for subsequent deposition of ultra-thin Pt electrodes.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of the RF magnetron co-sputtering process for fabricating YxIn2−xO3 thin films. (b) Determination of the optical bandgap for YxIn2−xO3 films using Tauc plots. (c) Variation in the optical bandgap of YxIn2−xO3 films as a function of the In2O3 sputtering power. (d) Surface SEM image and corresponding EDS elemental mapping of Y, In, and O for the Y1.5In0.5O3 film. (e) Cross-sectional SEM image of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film deposited on a silicon substrate. (f) AFM topographic image of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film.

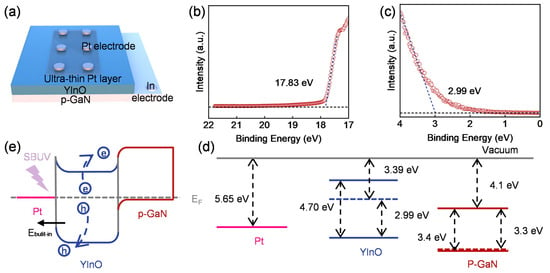

3.2. Heterojunction Design and Self-Powered Operation

We developed and assembled a Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3/p-GaN back-to-back heterojunction SBUV photodetector using the previously prepared Y1.5In0.5O3 film. The overall structure is schematically shown in Figure 2a, where Y1.5In0.5O3 functions as the photosensitive absorption layer, p-GaN serves as the substrate and forms a heterojunction with Y1.5In0.5O3, the ultra-thin Pt layer functions as the photocarrier collection layer, the thick Pt pad serves as the top electrode, and the In ohmic contact electrode serves as the bottom electrode. An optical micrograph of the device is presented in Figure S4a, from which the area of the ultra-thin Pt window is estimated to be approximately 1.125 mm2. Furthermore, the UV-vis transmission spectrum of an identical ultra-thin Pt layer deposited on a quartz substrate is given in Figure S4b, revealing a high transmittance of around 90% over the broad wavelength range of 200–800 nm. These results demonstrate the excellent optical transparency of the Pt layer across the SBUV to visible region, ensuring minimal absorption of light before it reaches the underlying Y1.5In0.5O3 photosensitive layer. Coupled with the intrinsically high electrical conductivity of Pt, the ultra-thin Pt layer not only facilitates efficient transport of photogenerated carriers but also maintains high incident photon flux, thereby synergistically optimizing the detection efficiency. To elucidate the internal energy band alignment and carrier transport mechanism, ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) was employed to characterize the Y1.5In0.5O3 film. The secondary electron cut-off region and the valence band onset region are shown in Figure 2(b) and Figure 2(c), respectively. From the UPS data, the work function of Y1.5In0.5O3 was determined to be 3.39 eV, and the energy difference between the valence band maximum and the Fermi level was found to be 2.99 eV. By combining the optically derived bandgap from Figure 1b, the complete band structure of Y1.5In0.5O3 was unambiguously established. Figure 2d depicts the initial band alignment among isolated Pt, Y1.5In0.5O3, and p-GaN before contact. Figure 2e illustrates the proposed equilibrium band diagram after the formation of the intimate back-to-back heterojunction. Upon junction formation, Fermi-level alignment induces band bending near both the Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3 interface and the Y1.5In0.5O3/p-GaN interface. Consequently, back-to-back potential barriers emerge, substantially suppressing the injection of majority carriers at zero bias and hence markedly reducing the dark current. Under SBUV illumination at 0 V bias, photogenerated electron–hole pairs are generated within the Y1.5In0.5O3 photosensitive layer. Driven by the built-in electric field at the Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3 Schottky interface, these carriers undergo spatial separation. Specifically, holes migrate toward and are collected by the Pt electrode, whereas electrons must overcome the barrier at the Y1.5In0.5O3/p-GaN interface, eventually being received by the bottom In electrode, completing the conversion of optical signals into electrical output.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of the device structure of the Y1.5In0.5O3-based SBUV photodetector; (b) Secondary electron cut-off region of the UPS spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film; (c) Valence band onset region of the UPS spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film; (d) Equilibrium band diagrams of isolated Pt, Y1.5In0.5O3, and p-GaN; (e) Energy band diagram illustrating the back-to-back heterojunction formed by the intimate contact among Pt, Y1.5In0.5O3, and p-GaN.

3.3. Comprehensive Photodetection Performance and Noise Analysis

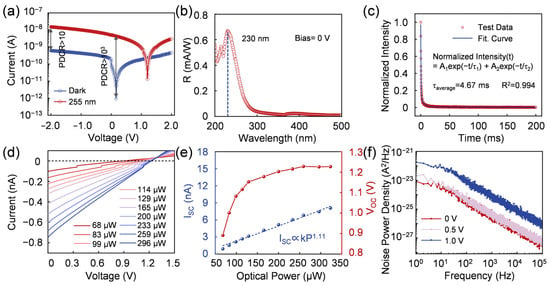

Figure 3a presents the current–voltage (I-V) characteristics of the device based on Y1.5In0.5O3 film under both dark conditions and 255 nm ultraviolet illumination. The results demonstrate that at bias voltages of 0.15 V and −2 V, the dark currents of the device are 9.3 × 10−13 A and 6.2 × 10−10 A, respectively, while the photocurrents are 4.4 × 10−9 A and 6.5 × 10−8 A, respectively. The self-biasing behavior of the device in the dark state can be ascribed to the built-in electric field at the Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3 Schottky interface, as depicted in Figure 2e. Moreover, Figure S5 provides direct evidence supporting the existence of this built-in electric field. The photo-to-dark current ratio (PDCR) is defined by the following equation [38]:

where Iphoto represents the current under SBUV irradiation, and Idark denotes the current in dark conditions. Calculations reveal that at 0.15 V and −2 V bias, the PDCR values are approximately 4.7 × 103 and 2.4 × 101, respectively, yielding a substantial benefit for its use highly sensitive SBUV detection applications. Figure 3b presents the spectral responsivity of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device at 0 V bias, showing a peak responsivity of 0.67 mA/W at 230 nm with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ~50 nm. This indicates its high selectivity towards ultraviolet light around 254 nm, which is essential for accurate identification of SBUV signals. Figure S6a shows the photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film, indicating that within the excitation wavelength (EX) range of 400–800 nm, the emission wavelength (EM) exhibits a peak at 565 nm. Figure S6b displays the photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film, revealing that excitation in the 240–380 nm range effectively induces emission at 565 nm, with EX = 365 nm being the most efficient excitation wavelength. Figure 3c and Figure S6c show the time-resolved PL (TRPL) decay curves plotted in both linear and logarithmic coordinates. By applying Equations (3) and (4) for fitting and analysis, the average decay lifetime of photogenerated carriers in the Y1.5In0.5O3 film is determined to be 4.67 ms. This prolonged lifetime suggests suppressed recombination of photogenerated carriers in the Y1.5In0.5O3 film, thereby laying a foundation for its promising optoelectronic response performance.

Figure 3.

(a) Current–voltage (I-V) characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3-based device measured under dark conditions and under 255 nm (200 μW) ultraviolet illumination; (b) Spectral responsivity of the Y1.5In0.5O3-based device at 0 V bias; (c) Time-resolved photoluminescence spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 film; (d) I-V characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3-based device under 255 nm ultraviolet illumination with varying optical power intensities; (e) Variation in the VOC and ISC of the Y1.5In0.5O3-based device with optical power. (f) Noise power spectral density as a function of frequency at different biases.

Figure 3d compares the current-voltage (I–V) characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device under 255 nm ultraviolet illumination at varying optical power intensities. The results demonstrate a marked increase in photocurrent with rising optical power. The dependence of the open-circuit voltage (VOC) and short-circuit current (ISC) on the optical power, extracted from Figure 3d, is summarized in Figure 3e. It is evident that both VOC and ISC increase with enhanced optical power. As a key indicator of photovoltaic performance [39,40,41], a high VOC is essential for achieving high power conversion efficiency in Y1.5In0.5O3-based devices. Through fitting analysis, the exponent describing the power-law dependence of ISC on optical power is determined to be 1.11, which is close to the ideal value of 1, suggesting highly stable output characteristics under photovoltaic operation [42].

The detection limit of a photodetector is characterized by its NEP, which is defined as the incident optical power required to produce a signal-to-noise ratio of 1 in a 1 Hz bandwidth. This parameter quantifies the sensitivity to weak light signals and is given by:

where Inoise denotes the noise current measured in the dark, and R is the responsivity. The noise current Inoise is given by

As derived from Figure 3b, the Y1.5In0.5O3 device exhibits a responsivity of 0.34 mA/W under 255 nm illumination. Figure 3e presents the noise power spectral density (Si-f) characteristics at different biases. At 0 V bias, the measured noise current (Inoise) and the corresponding NEP are 2.95 × 10−12 A/Hz1/2 and 4.42 × 10−9 W/Hz1/2, respectively, indicating its a low noise floor and superior capability for weak-light detection.

Furthermore, the total noise current (Inoise) is primarily governed by four distinct components: shot noise (Is), thermal noise (It), flicker noise (I1/f), and generation-recombination noise (Ig−r), as given by Equation (7).

As evidenced by the data in Figure 3e and Figure S7, no discernible noise plateau is observed within the measured frequency range. Instead, the logarithmic noise power spectral density, lg(Si), decreases linearly with increasing logarithmic frequency, lg(f), indicating that Si adheres to a power-law relationship with f, expressed as:

The extracted flicker noise exponents (γ) at 0 V, 0.5 V, and 1 V are 0.973, 0.975, and 0.991, respectively, strongly indicating that the device noise is predominantly governed by the flicker noise component (I1/f). Furthermore, as the bias voltage increases from 0 V to 1 V, the overall noise amplitude rises by approximately 1.5 orders of magnitude, suggesting a direct correlation between the noise sources and the carrier transport process.

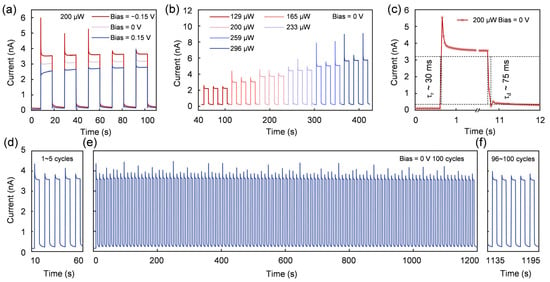

3.4. Dynamic Response and Operational Durability

To further investigate the photodetection performance of the device, this study measured the multi-cycle current-time (I-T) characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device under two sets of conditions: (i) illumination with 255 nm ultraviolet light at 200 μW under bias voltages ranging from −0.15 V to 0.15 V, and (ii) at 0 V bias under 255 nm ultraviolet illumination with optical power densities varying from 129 μW to 233 μW. The results are presented in Figure 4(a) and (b), respectively. The increase in photocurrent with increasingly negative bias can be attributed to the built-in electric field at the Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3 Schottky interface, which is consistent with Figure 3a. Under negative bias, which aligns with the direction of the built-in field, the efficient separation of photogenerated carriers is facilitated, resulting in a higher photocurrent, whereas a positive bias produces the opposite effect. The device exhibited reproducible and stable photoresponse behavior under varying bias and illumination conditions, confirming its excellent stability and repeatability. To quantitatively analyze the influence of optical power on the photocurrent at a fixed 0 V bias, the photocurrent from each response cycle under different light intensities was extracted and plotted in Figure S8a, showing high consistency across cycles, with the photocurrent increasing nearly linearly with rising optical power. Similarly, to evaluate the effect of bias voltage on the photocurrent under fixed ultraviolet illumination, the photocurrent from each cycle under different bias voltages was extracted and summarized in Figure S8c. The results reveal a decreasing trend in photocurrent with increasing bias voltage, a behavior consistent with the I–V characteristics shown in Figure 2a. To verify the critical role of the ultrathin Pt layer in carrier collection, we fabricated and tested a control device without the ultrathin Pt layer. Under identical illumination conditions (255 nm, 200 μW), the photocurrent of the control device is only at the pA level (Figure S9). This pronounced difference directly demonstrates that the ultrathin Pt layer enhances carrier extraction efficiency by providing an effective charge-collection pathway, thereby ensuring the superior photoresponse performance of the device.

Figure 4.

(a) I-T characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device under 255 nm ultraviolet illumination (200 μW) at different bias voltages; (b) Multi-cycle I-T curves of the device measured at 0 V bias under 255 nm ultraviolet illumination with different optical power densities; (c) Single-cycle I-T curve of the device, representing a typical cycle selected from (b), where the response time is defined by the time taken for the photocurrent to decay between 90% and 10% of the peak magnitude; (d–f) Long-term performance of the device.

To further analyze the influence of ultraviolet intensity and bias voltage on the response time of the device, a single-cycle I-T curve was extracted from Figure 4b and is presented in Figure 4c. Under 0 V bias and 200 μW, 255 nm ultraviolet illumination, the device exhibits rise and decay times of approximately 30 ms and 75 ms, respectively. This rapid response is attributed to the pyroelectric effect, wherein the transient current spikes generated upon the initiation and termination of illumination effectively reduce the overall response time [43,44,45]. To systematically evaluate the statistical trends of response time with respect to bias voltage and light intensity, the rise and decay times from each response cycle in Figure 4a,b were extracted and are summarized in Figure S8b,d. The results confirm that the response time remains below 110 ms across all measured conditions.

To quantify the operational durability of the device, the I-T characteristics of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device were measured over 100 consecutive cycles at 0 V bias, as shown in Figure 4e. The photocurrent response exhibits remarkable stability and repeatability throughout the test. Representative cycles, specifically the 1st–5th and the 96th–100th, are displayed in Figure 4(d) and (f), respectively. Remarkably, the device exhibits a minimal photocurrent degradation of only 0.8% after 100 cycles. These results collectively indicate that the Y1.5In0.5O3-based device possesses high response speed, excellent durability and repeatability, thereby rendering it a promising candidate for reliable deployment in practical applications.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully synthesized YxIn2−xO3 bandgap-engineered ternary alloy thin films via a controllable RF magnetron co-sputtering process. By regulating the sputtering power of the In2O3 target, the optical bandgap was precisely engineered, and the Y1.5In0.5O3 film with an optimal bandgap of 4.70 eV was employed as the photoresponse medium for constructing a Pt/Y1.5In0.5O3/p-GaN back-to-back heterojunction SBUV photodetector.

The fabricated device operates efficiently at 0 V bias, demonstrating a combination of high spectral selectivity (FWHM~50 nm), fast response (rise/decay times of 30/75 ms), and excellent operational durability (only 0.8% photocurrent variation over 100 cycles). Moreover, the detector exhibits an ultralow noise current of 2.95 × 10−12 A/Hz1/2 and a low noise-equivalent power (NEP) of 4.42 × 10−9 W/Hz1/2 underscoring its superior sensitivity to weak optical signals.

These results validate YxIn2−xO3 as a highly promising material platform for high-performance, self-powered SBUV photodetection. The proposed heterojunction architecture, which synergistically combines bandgap-engineered absorption, built-in potential-driven carrier separation, and low dark current, offers a viable and effective design strategy for future high-sensitivity, low-noise, and spectrally selective UV photodetectors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/technologies14010023/s1. Figure S1: Ultraviolet-visible transmission spectra of thin films with different compositions; Figure S2: Band alignment diagram of Y2O3 and In2O3; Figure S3: Quantitative EDS analysis results; Figure S4: (a) Optical micrograph of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device, (b) Ultraviolet-visible transmission spectrum of the ultra-thin Pt layer film; Figure S5: I–V curves obtained under the original and the swapped-contact configurations; Figure S6: (a) Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 thin film, (b) Photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 thin film, (c) Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectrum of the Y1.5In0.5O3 thin film presented on a logarithmic scale; Figure S7: Noise power spectral density of the Y1.5In0.5O3 device under different bias voltages and the corresponding fitting results; Figure S8: (a) Relationship between photocurrent and incident optical power at 0 V bias, (b) Extracted response times of the device under different incident optical power densities, (c) Relationship between photocurrent and bias voltage under 200 μW incident optical power, (d) Extracted response times of the device under different bias voltages; Figure S9: Comparison of temporal photoresponse between devices with and without the ultrathin Pt layer under 255 nm illumination (200 μW).

Author Contributions

L.G. and P.J. contributed equally. Conceptualization, L.G. and Y.L.; methodology, Z.J. and Y.X.; investigation, L.G., Z.J. and Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G., P.J. and Z.J.; writing—review and editing, L.G. and Y.L.; visualization, Z.J. and Y.X.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, L.G. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Department of Education of Jiangxi Province, grant number GJJ211924 and in part by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under Grant 2022A1515011272.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| EM | Emission Wavelength |

| EX | excitation wavelength |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| ISC | Short-circuit Current |

| NEP | Noise-equivalent Power |

| PDCR | Photo-to-dark Current Ratio |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| RMS | Root-mean-square |

| SBUV | Solar-blind Ultraviolet |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TRPL | Time-resolved Photoluminescence |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–visible |

| VOC | Open-circuit Voltage |

References

- Xu, Z.; Sadler, B.M. Ultraviolet Communications: Potential and State-of-the-Art. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2008, 46, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Nakagomi, S.; Kokubun, Y.; Arai, N.; Ohira, S. Enhancement of Responsivity in Solar-Blind β-Ga2O3 Photodiodes with a Au Schottky Contact Fabricated on Single Crystal Substrates by Annealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 222102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Huang, F.; Zheng, R.; Wu, H. Low-Dimensional Structure Vacuum-Ultraviolet-Sensitive (λ < 200 nm) Photodetector with Fast-Response Speed Based on High-Quality AlN Micro/Nanowire. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3921–3927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsai, D.-S.; Lien, W.-C.; Lien, D.-H.; Chen, K.-M.; Tsai, M.-L.; Senesky, D.G.; Yu, Y.-C.; Pisano, A.P.; He, J.-H. Solar-Blind Photodetectors for Harsh Electronics. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ouyang, W.; Yang, W.; He, J.-H.; Fang, X. Recent Progress of Heterojunction Ultraviolet Photodetectors: Materials, Integrations, and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tian, R.; Lin, P.; Shi, Z.; Chen, X.; Jia, M.; Tian, Y.; Li, X.; Zeng, L.; Jie, J. Wafer-Scale Synthesis of Wide Bandgap 2D GeSe2 Layers for Self-Powered Ultrasensitive UV Photodetection and Imaging. Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, T.; Fang, X. Low-Dimensional Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors for UV Photodetectors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jia, L.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, W. Vacuum-Ultraviolet (λ < 200 nm) Photodetector Array. PhotoniX 2024, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, M. Short-Wavelength Solar-Blind Detectors-Status, Prospects, and Markets. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tokizono, T.; Liao, M.; Zhong, M.; Koide, Y.; Yamada, I.; Delaunay, J.-J. Efficient Assembly of Bridged β-Ga2O3 Nanowires for Solar-Blind Photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 3972–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-N.; Shan, C.-X. Optoelectronic Diamond: Growth, Properties, and Photodetection Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.Y.; Alvarez, J.; Koide, Y. Thermal Stability of Diamond Photodiodes Using Tungsten Carbide as Schottky Contact. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 7832–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Fu, J.; Fan, S.; Bu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.-X.; et al. UV-Photodetector Based on NiO/Diamond Film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 032103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.W.; Chen, Q.C.; Yang, J.Y.; Asif Khan, M. High Responsitivity Intrinsic Photoconductors Based on AlxGa1−xN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 3761–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Ben, J.; Che, J.; Shi, Z.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lv, W.; et al. Polarization-Enhanced AlGaN Solar-Blind Ultraviolet Detectors. Photon. Res. 2020, 8, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yong, D.; Chen, M.; Ji, X.; Su, Y.; Gui, X.; Pan, B.; Xiang, R.; Tang, Z. Wide Range Bandgap Modulation Based on ZnO-Based Alloys and Fabrication of Solar Blind UV Detectors with High Rejection Ratio. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 14152–14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alema, F.; Hertog, B.; Ledyaev, O.; Volovik, D.; Miller, R.; Osinsky, A.; Bakhshi, S.; Schoenfeld, W.V. High Responsivity Solar Blind Photodetector Based on High Mg Content MgZnO Film Grown via Pulsed Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2016, 249, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Yao, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Zang, X.; Lin, L. A Solar-Blind UV Detector Based on Graphene-Microcrystalline Diamond Heterojunctions. Small 2017, 13, 1701328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segnit, E.R.; Holland, A.E. The System MgO-ZnO-SiO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1965, 48, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hullavarad, S.S.; Nagaraj, B.; Takeuchi, I.; Sharma, R.P.; Venkatesan, T.; Vispute, R.D.; Shen, H. Compositionally-Tuned Epitaxial Cubic MgxZn1−xO on Si(100) for Deep Ultraviolet Photodetectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 3424–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, B.K.; Bhole, M.P.; Patil, D.S. Structural, Optical and Electrical Properties of MgxZn1−xO Ternary Alloy Films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 2009, 12, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.F.; Sisonyuk, A.G.; Himich, E.G. Growth Conditions, Optical and Dielectric Properties of Yttrium Oxide Thin Films. Phys. Stat. Sol. (A) 1994, 145, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboriaud, R.J.; Pailloux, F.; Guerin, P.; Paumier, F. Yttrium Sesquioxide, Y2O3, Thin Films Deposited on Si by Ion Beam Sputtering: Microstructure and Dielectric Properties. Thin Solid Films 2001, 400, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, H.J.; Cheong, K.Y. Deposition and Post-Deposition Annealing of Thin Y2O3 Film on n-Type Si in Argon Ambient. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 130, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, M.; Lisowski, W.; Pisarek, M.; Nikiforow, K.; Jablonski, A. Surface Characterization of Low-Temperature Grown Yttrium Oxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 437, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Chen, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, J. The Tunable Dielectric Properties of Sputtered Yttrium Oxide Films. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, R. Yttrium Oxide Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 3842–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingon, A.I.; Maria, J.-P.; Streiffer, S.K. Alternative Dielectrics to Silicon Dioxide for Memory and Logic Devices. Nature 2000, 406, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilk, G.D.; Wallace, R.M.; Anthony, J.M. High-κ Gate Dielectrics: Current Status and Materials Properties Considerations. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89, 5243–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Miao, L.; Lu, Y.; He, Y. Multi-Component ZnO Alloys: Bandgap Engineering, Hetero-Structures, and Optoelectronic Devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2022, 147, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiher, R.L.; Ley, R.P. Optical Properties of Indium Oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 1966, 37, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.H.; Ryu, S.Y.; Jo, S.J.; Kim, C.S.; Sohn, S.-W.; Rack, P.D.; Kim, D.-J.; Baik, H.K. Indium Oxide Thin-Film Transistors Fabricated by RF Sputtering at Room Temperature. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2010, 31, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurashi, A.; El-Maghraby, E.M.; Yamazaki, T.; Kikuta, T. Catalyst-Free Shape Controlled Synthesis of In2O3 Pyramids and Octahedron: Structural Properties and Growth Mechanism. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, L9–L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinuma, Y.; Gake, T.; Oba, F. Band Alignment at Surfaces and Heterointerfaces of Al2O3, Ga2O3, In2O3, and Related Group-III Oxide Polymorphs: A First-Principles Study. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 084605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Navrotsky, A.; Guo, B.; Kennedy, I.; Clark, A.N.; Lesher, C.; Liu, Q. Energetics of Cubic and Monoclinic Yttrium Oxide Polymorphs: Phase Transitions, Surface Enthalpies, and Stability at the Nanoscale. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Peng, J.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Yin, S.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L. Effect of Temperature on the Preparation of Yttrium Oxide in Microwave Field. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 742, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakuphanoglu, F.; Arslan, M. The Fundamental Absorption Edge and Optical Constants of Some Charge Transfer Compounds. Opt. Mater. 2004, 27, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, W.; Huang, F. Pt/ZnGa2O4/p-Si Back-to-Back Heterojunction for Deep UV Sensitive Photovoltaic Photodetection with Ultralow Dark Current and High Spectral Selectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5653–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, F.; Chen, H.; Zheng, L.; Su, L.; Zhao, D.; Fang, X. An Ultrahigh Responsivity (9.7 mA W−1) Self-Powered Solar-Blind Photodetector Based on Individual ZnO–Ga2O3 Heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lin, R.; Jia, L.; Huang, F. Vacuum-Ultraviolet-Oriented van Der Waals Photovoltaics. ACS Photonics 2019, 6, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jia, L.; Zheng, W.; Huang, F. Fermi-Surface Modulation of Graphene Synergistically Enhances the Open-Circuit Voltage and Quantum Efficiency of Photovoltaic Solar-Blind Ultraviolet Detectors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 11106–11113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiao, P.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, W. A High-Performance Self-Powered Solar-Blind UV Photodetector Based on an Annealed Sc0.74In1.26O3 Ternary Alloy Film. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 13197–13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, R.; Pan, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Yi, F.; Wang, Z.L. Light-Induced Pyroelectric Effect as an Effective Approach for Ultrafast Ultraviolet Nanosensing. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, D.; Hussain, A.A.; Biswasi, S.; Pal, A.R. Crystalline Rubrene via a Novel Process and Realization of a Pyro-Phototronic Device with a Rubrene-Based Film. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 6450–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahare, S.; Ghoderao, P.; Sharma, M.K.; Solovan, M.; Aepuru, R.; Kumar, M.; Chan, Y.; Ziółek, M.; Lee, S.-L.; Lin, Z.-H. Pyro-Phototronic Effect: An Effective Route toward Self-Powered Photodetection. Nano Energy 2023, 107, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.