A Benchmarking Framework for Cost-Effective Wearables in Oncology: Supporting Remote Monitoring and Scalable Digital Health Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Health and Telemedicine in Oncology

1.2. Devices in Healthcare and Oncology

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective and Device Selection Criteria

- ▪

- Clinical relevance: Devices had to measure core physiological parameters relevant to oncology monitoring, including heart rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure, respiratory indicators and/or physical activity.

- ▪

- Manufacturer reliability: Only devices produced by established vendors offering technical documentation, maintenance, and long-term ecosystem support were retained.

- ▪

- Data protection and GDPR compliance: Devices were included only if they guaranteed secure data collection, encrypted transmission, user consent management, and storage within the European Union or under explicit EU data residency and legal conformity.

- ▪

- Economic sustainability: Devices requiring mandatory subscription plans, recurring licensing fees, or pay-per-use access to APIs or cloud data were excluded. Preference was given to one-time purchase solutions with unrestricted access to collected data.

- ▪

- Wearability and continuous monitoring: Only wearable devices enabling non-invasive, continuous monitoring during daily life and treatment cycles were included. Non-wearable solutions were excluded due to limited usability in home settings and inability to provide uninterrupted data streams.

2.2. Selection Workflow and Data Sources

2.3. Comparative Evaluation and Integration Feasibility

- Medical Certification (0–9): 0 = no certification; 3–5 = device with partial or feature-specific clearance (e.g., CE/FDA approval limited to one function such as ECG-based AF detection, wellness classification for other metrics); 6–8 = CE-MDR Class IIa/IIb or FDA medical device clearance for clinically relevant physiological monitoring, with declared intended use; 9 = full CE/FDA approval covering clinically relevant monitoring functions with clear regulatory class specification and intended medical purpose.

- API Availability (0–8): 0 = no developer access; 8 = fully open, well-documented API with access to raw biometric data.

- GDPR Compliance (0–8): 0 = non-compliant/no data governance; 4 = unclear or unverifiable; 8 = full compliance with EU-based servers and data processing agreements.

- Battery Life (1–5): 1 = ≤1 day; 5 = ≥15 days of continuous use.

- Cost (1–5): 1 = >€500; 5 = <€200.

- Subscription Requirement (1–5): 1 = mandatory subscription to access data; 5 = no subscription required.

3. Results

3.1. Device Performance Overview

3.2. Exploratory Integration Scenario

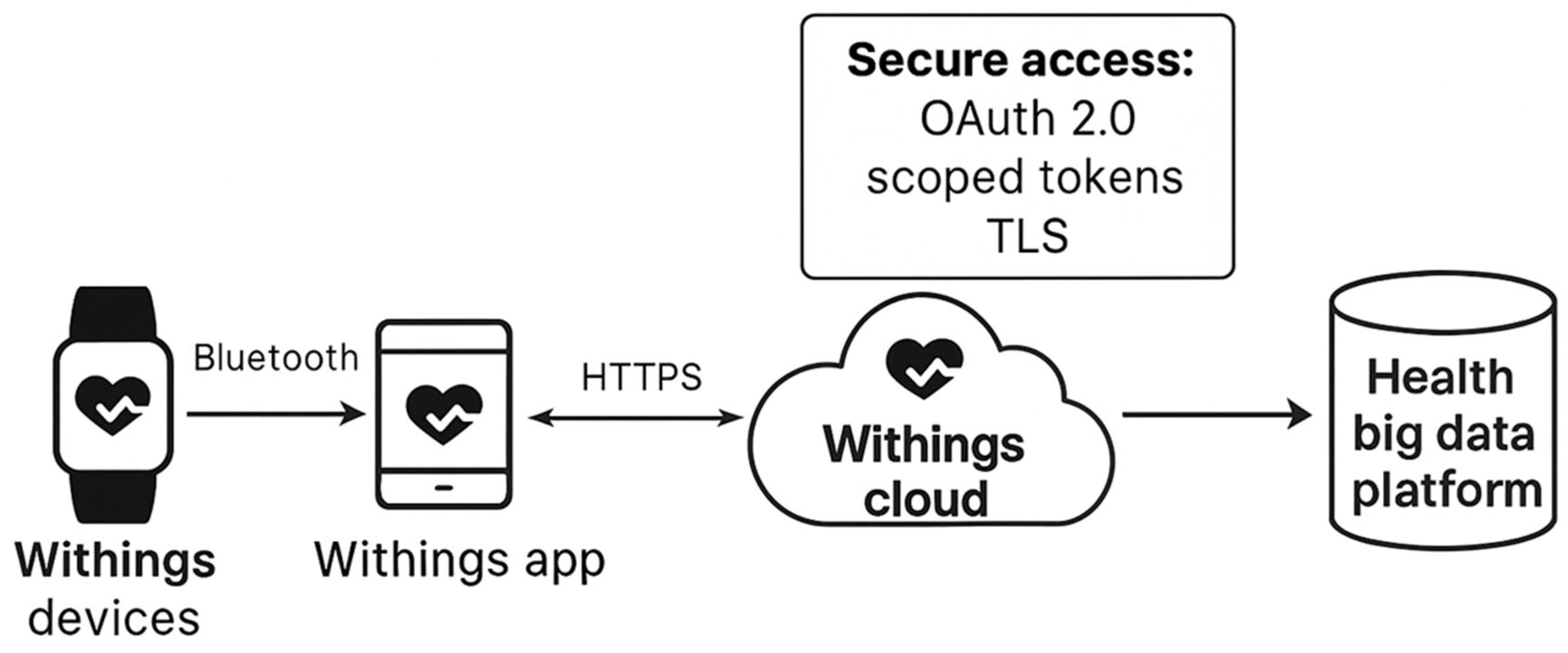

- Open RESTful API access (used in this study): provides JSON-formatted biometric data and supports webhooks for event-based notifications, OAuth 2.0 authentication and GDPR-compliant consent management.

- Proprietary SDK or closed ecosystem (used in other platforms such as Apple HealthKit or Samsung Health): requires vendor-specific developer accounts and does not always allow access to raw physiological data.

- Devices where no API access is available and data remain confined within the vendor’s ecosystem.

4. Discussion

Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.R.; Weaver, K.E.; Aziz, N.M.; Alfano, C.M.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Kent, E.E.; Forsythe, L.P.; Rowland, J.H. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: Prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, G.W.; Braga, S.; Bystricky, B.; Qvortrup, C.; Criscitiello, C.; Esin, E.; Sonke, G.S.; Martínez, G.A.; Frenel, J.S.; Karamouzis, M.; et al. Global cancer control: Responding to the growing burden, rising costs and inequalities in access. ESMO Open 2018, 3, e000285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, K.M.; Turner, K.L.; Siwik, C.; Gonzalez, B.D.; Upasani, R.; Glazer, J.V.; Ferguson, R.J.; Joshua, C.; Low, C.A. Digital health and telehealth in cancer care: A scoping review of reviews. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e316–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, H.; Dillon, B.; Collinson, L.; Powell, H.; Salmon, M.; Oladapo, T.; Ayiku, L.; Shield, G.; Holden, J.; Patel, N.; et al. The NICE Evidence Standards Framework for digital health and care technologies—Developing and maintaining an innovative evidence framework with global impact. Digit Health 2021, 7, 20552076211018617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E.; Trigg, J.; Beatty, L.; Christensen, C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Maeder, A.; Williams, P.A.H.; Koczwara, B. Health literacy, digital health literacy and the implementation of digital health technologies in cancer care: The need for a strategic approach. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2021, 32, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.C.; Wu, X.R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhou, Y.L.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.L.; Yan, Q.Y. Artificial intelligence empowered digital health technologies in cancer survivorship care: A scoping review. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 9, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, R.B.; Basen-Enquist, K.M.; Bradley, C.; Estrin, D.; Levy, M.; Lichtenfeld, J.L.; Malin, B.; McGraw, D.; Meropol, N.J.; Oyer, R.A.; et al. Digital Health Applications in Oncology: An Opportunity to Seize. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Ryals, C.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Byers, E.; Clewett, E. Leveraging Digital Technology to Reduce Cancer Care Inequities. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, B.B.; Rossi, B.; Fuemmeler, B. The role of digital health technology in rural cancer care delivery: A systematic review. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, J.; Ajakaiye, A.; Cooksley, T.; Subbe, C.P. Do mHealth applications improve clinical outcomes of patients with cancer? A critical appraisal of the peer-reviewed literature. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siglen, E.; Vetti, H.H.; Lunde, A.B.F.; Hatlebrekke, T.A.; Strømsvik, N.; Hamang, A.; Hovland, S.T.; Rettberg, J.W.; Steen, V.M.; Bjorvatn, C. Ask Rosa—The making of a digital genetic conversation tool, a chatbot, about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, G.; Spinazze, P.; Matchar, D.; Koh Choon Huat, G.; van der Kleij, R.; Chavannes, N.H.; Car, J. Digital health competencies for primary healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 143, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanian, S.; Nakarada-Kordic, I.; Reay, S.; Chetty, T. Patients’ perspectives on digital health tools. PEC Innov. 2023, 2, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woudstra, K.; Reuzel, R.; Rovers, M.; Tummers, M. An Overview of Stakeholders, Methods, Topics, and Challenges in Participatory Approaches Used in the Development of Medical Devices: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2023, 12, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J.; Runge, R.; Snyder, M. Wearables and the medical revolution. Pers. Med. 2018, 15, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamer, T.; Traulsen, P.; Rieken, J.; Schmahl, T.; Menrath, I.; Steinhäuser, J. Determinants of the implementation of eHealth-based long-term follow-up care for young cancer survivors: A qualitative study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaverdian, N.; Gillespie, E.F.; Cha, E.; Kim, S.Y.; Benvengo, S.; Chino, F.; Kang, J.J.; Li, Y.; Atkinson, T.M.; Lee, N.; et al. Impact of Telemedicine on Patient Satisfaction and Perceptions of Care Quality in Radiation Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2021, 19, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Dievler, A.; Robbins, C.; Sripipatana, A.; Quinn, M.; Nair, S. Telehealth In Health Centers: Key Adoption Factors, Barriers, And Opportunities. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarelli, C.; Colucci, C.; Mitrano, G.; Corallo, A. Business Models in Digital Health: Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Gammarth, Tunisia, 9–12 July 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stavropoulos, T.G.; Lazarou, I.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Georges, J.; Manyakov, N.V.; Pich, E.M.; Hinds, C.; Tsolaki, M.; Nikolopoulos, S.; et al. Wearable Devices for Assessing Function in Alzheimer’s Disease: A European Public Involvement Activity About the Features and Preferences of Patients and Caregivers. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 643135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, S.M.; An, H.S.; Kang, S.K.; Noble, J.M.; Berg, K.E.; Lee, J.M. Concurrent Validity of Wearable Activity Trackers Under Free-Living Conditions. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, U.L.; Pappot, H.; Holländer-Mieritz, C. The Use of Wearables in Clinical Trials During Cancer Treatment: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e22006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, W.; Bloem, R.; Ananth, A.; Kanagasabapathi, T.; Amelink, A.; Bouwman, J.; Gelinck, G.; van Veen, S.; Boorsma, A.; Wopereis, S. Digital Resilience Biomarkers for Personalized Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention. Front. Digit. Health 2020, 2, 614670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.; Drkulec, H.; Im, J.H.B.; Tsai, J.; Nafees, A.; Kumar, S.; Hou, T.; Fazelzad, R.; Leighl, N.B.; Krzyzanowska, M.; et al. The Use of Wearable Devices in Oncology Patients: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2024, 29, e419–e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, E.; Zuberi, S.; Aly, M.; Askari, A.; Iqbal, F.M. Clinical Outcomes of Passive Sensors in Remote Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappot, H.; Steen-Olsen, E.B.; Holländer-Mieritz, C. Experiences with Wearable Sensors in Oncology during Treatment: Lessons Learned from Feasibility Research Projects in Denmark. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Thompson, C.; Peterson, S.; Mandrola, J.; Beg, M.S. The Future of Wearable Technologies and Remote Monitoring in Health Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, M.R.; Yu, X.; Sweeney Magee, M.; Forbes, C.C.; Grandy, S.A.; Sweeney, E.; Dummer, T.J.B. Use of Wearable Activity-Monitoring Technologies to Promote Physical Activity in Cancer Survivors: Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Cancer Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, V.J.; Oliveira, R.A.; da Silva, M.J. Recent trends in wearable computing research: A systematic review. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Colwell, E.; Low, J.; Orychock, K.; Tobin, M.A.; Simango, B.; Buote, R.; Van Heerden, D.; Luan, H.; Cullen, K.; et al. Reliability and Validity of Commercially Available Wearable Devices for Measuring Steps, Energy Expenditure, and Heart Rate: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e18694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloß, K.; Verket, M.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Marx, N.; Schuett, K.; Jost, E.; Crysandt, M.; Beier, F.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Kobbe, G.; et al. Application of wearables for remote monitoring of oncology patients: A scoping review. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241233998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, L.; Grimshaw, S.L.; Stolper, J.; Passmore, E.; Ball, G.; Elliott, D.A.; Conyers, R. Scoping review of the utilization of wearable devices in pediatric and young adult oncology. Npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, W.J.; Hassinger, T.E.; Myers, E.L.; Chu, D.L.; Charles, A.N.; Hoang, S.C.; Friel, C.M.; Thiele, R.H.; Hedrick, T.L. Wearable technology and the association of perioperative activity level with 30-day readmission among patients undergoing major colorectal surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 1584–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birla, M.; Rajan, R.; Roy, P.G.; Gupta, I.; Malik, P.S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence-Driven Wearable Technology in Oncology Decision-Making: A Narrative Review. Oncology 2025, 103, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, C.; Baldwin, M.; Keogh, A.; Caulfield, B.; Argent, R. Keeping Pace with Wearables: A Living Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews Evaluating the Accuracy of Consumer Wearable Technologies in Health Measurement. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2907–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, G.; Gervasi, M.; Angelelli, M.; Corallo, A. A Conceptual Framework for Digital Twin in Healthcare: Evidence from a Systematic Meta-Review. Inf. Syst. Front. 2025, 27, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okegbile, S.D.; Cai, J.; Niyato, D.; Yi, C. Human Digital Twin for Personalized Healthcare: Vision, Architecture and Future Directions. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Inclusion Criterion | Description | Devices Remaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial device pool | Devices identified from market analysis, literature and manufacturer data | 23 |

| 2 | Clinical relevance | Must measure oncology-related biomarkers: HR, SpO2, ECG, BP, respiratory rate or physical activity | 23 → 15 |

| 3 | Manufacturer reliability | Only established vendors with technical support, documentation, and stable ecosystem | 15 → 12 |

| 4 | GDPR-compliant data governance | Secure data handling, encryption, EU data storage or EU data residency guarantees | 12 → 9 |

| 5 | Economic sustainability | Devices with mandatory subscriptions or pay-per-use data access excluded | 9 → 8 |

| 6 | Wearability and continuous monitoring | Only wearable devices retained → non-wearables excluded | 8 → 6 |

| 7 | Final comparative assessment | Evaluation of API integration, battery life, medical certification, interoperability and scalability | 6 → 1 |

| Outcome | Final selected device | Withings ScanWatch 2—best balance of medical-grade certification, battery life, GDPR compliance and open API | 1 |

| Device | Medical Cert. (0–9) | API (0–8) | GDPR (0–8) | Battery (1–5) | Cost (1–5) | Subscription (1–5) | Total (su 40) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withings ScanWatch 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 37 |

| Fitbit Sense 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 23 |

| Apple Watch Series 7 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 22 |

| Samsung Galaxy Watch4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 20 |

| Google Pixel Watch | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| Asus VivoWatch SP | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bindi, B.; Garofano, M.; Parretti, C.; Pascarelli, C.; Arcidiacono, G.; Bandinelli, R.; Corallo, A. A Benchmarking Framework for Cost-Effective Wearables in Oncology: Supporting Remote Monitoring and Scalable Digital Health Integration. Technologies 2026, 14, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010024

Bindi B, Garofano M, Parretti C, Pascarelli C, Arcidiacono G, Bandinelli R, Corallo A. A Benchmarking Framework for Cost-Effective Wearables in Oncology: Supporting Remote Monitoring and Scalable Digital Health Integration. Technologies. 2026; 14(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBindi, Bianca, Marina Garofano, Chiara Parretti, Claudio Pascarelli, Gabriele Arcidiacono, Romeo Bandinelli, and Angelo Corallo. 2026. "A Benchmarking Framework for Cost-Effective Wearables in Oncology: Supporting Remote Monitoring and Scalable Digital Health Integration" Technologies 14, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010024

APA StyleBindi, B., Garofano, M., Parretti, C., Pascarelli, C., Arcidiacono, G., Bandinelli, R., & Corallo, A. (2026). A Benchmarking Framework for Cost-Effective Wearables in Oncology: Supporting Remote Monitoring and Scalable Digital Health Integration. Technologies, 14(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010024