Robustness Assessment of Cyber-Physical Power Systems Considering Cyber Network Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

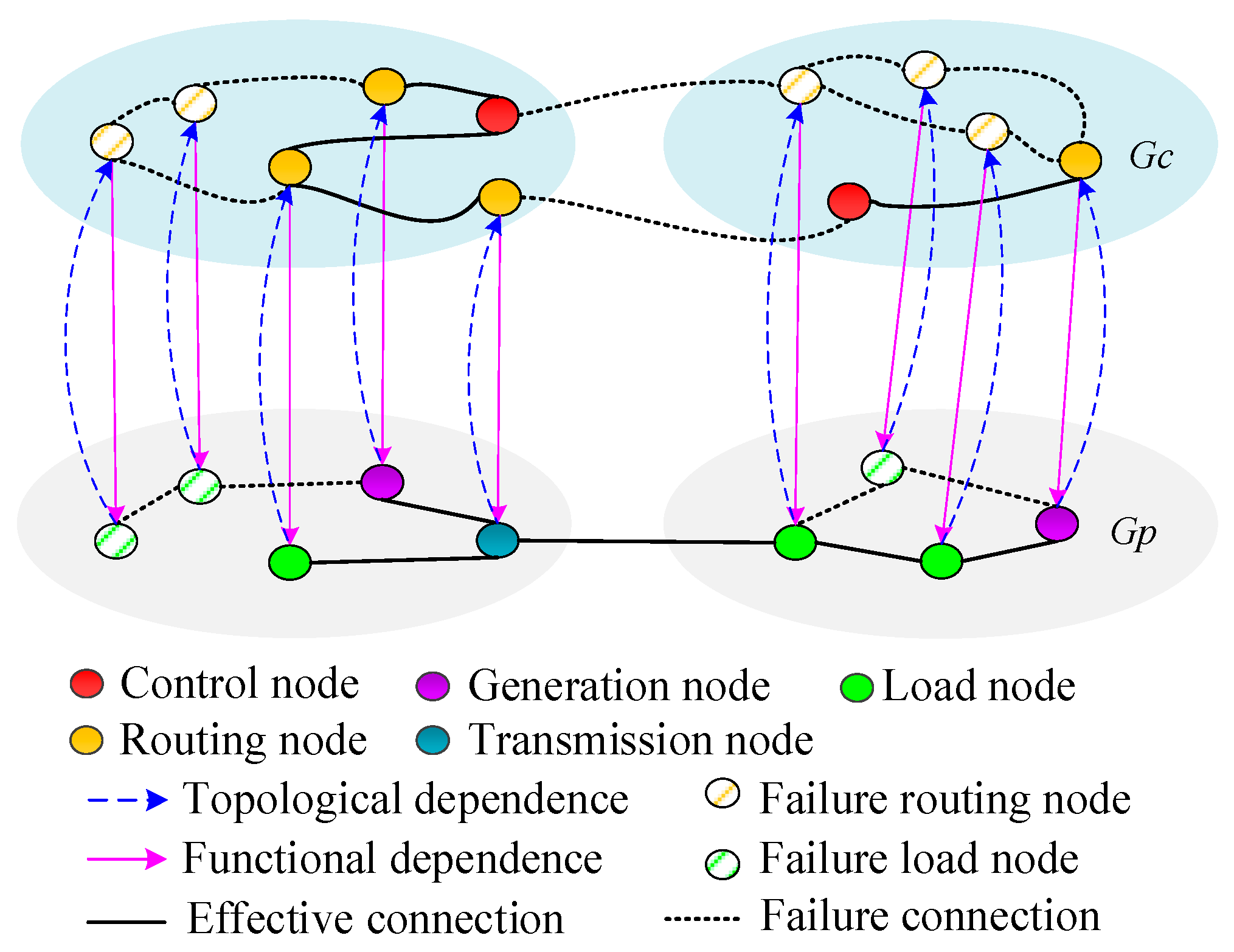

2. Network Model

2.1. Hierarchical Topology Modeling

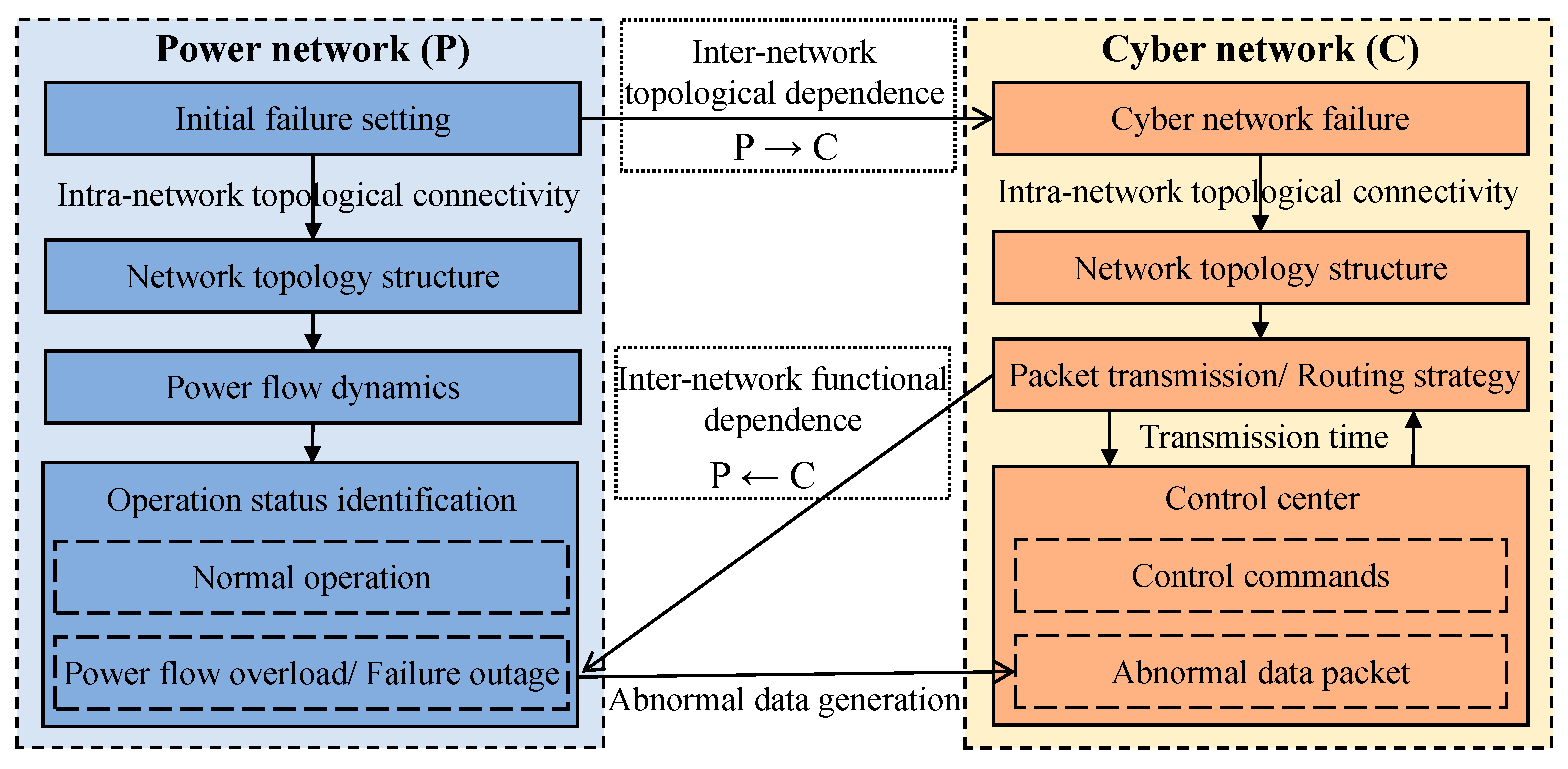

2.2. Dynamic Characteristics of Networks

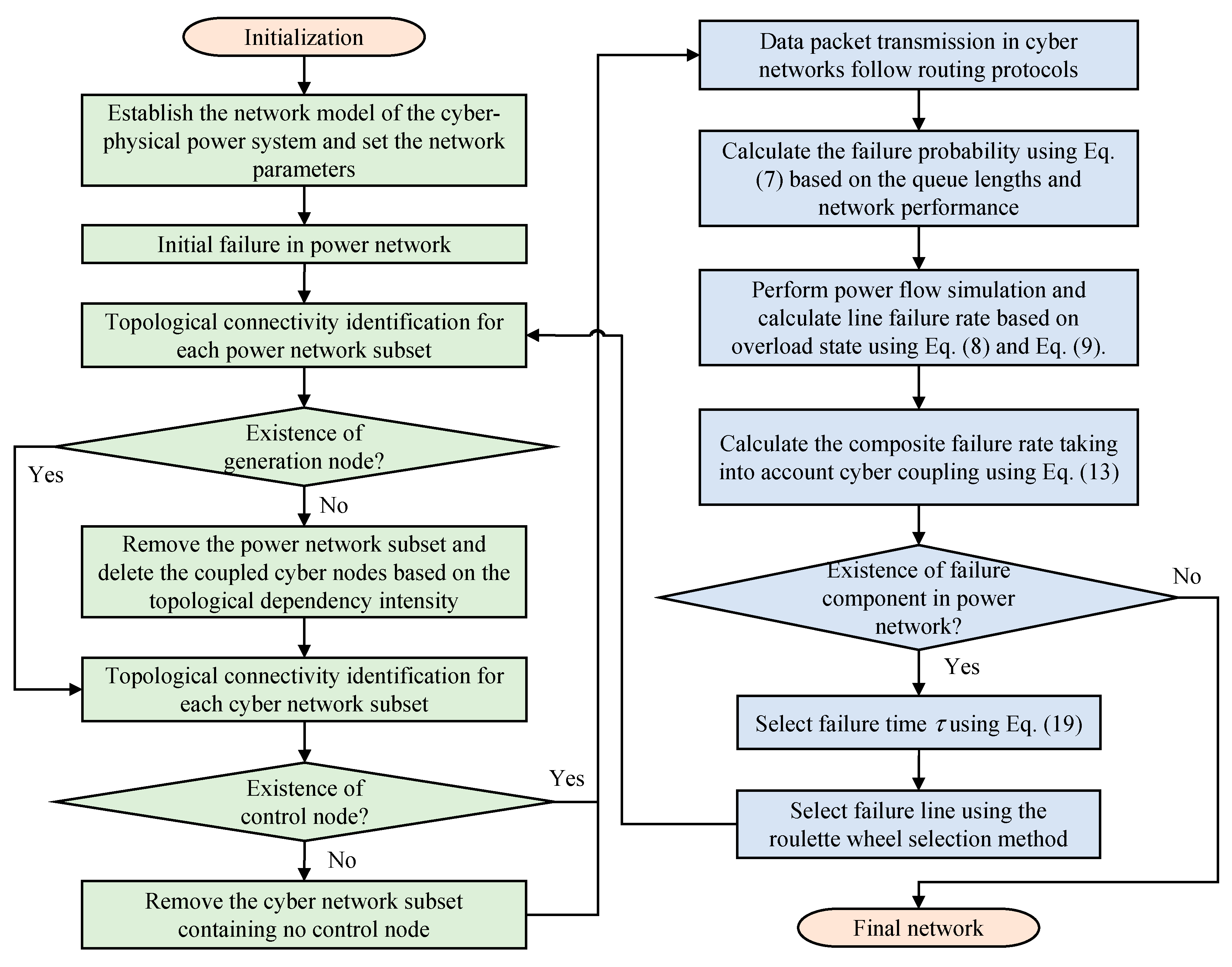

3. Failure Propagation and Robustness Assessment

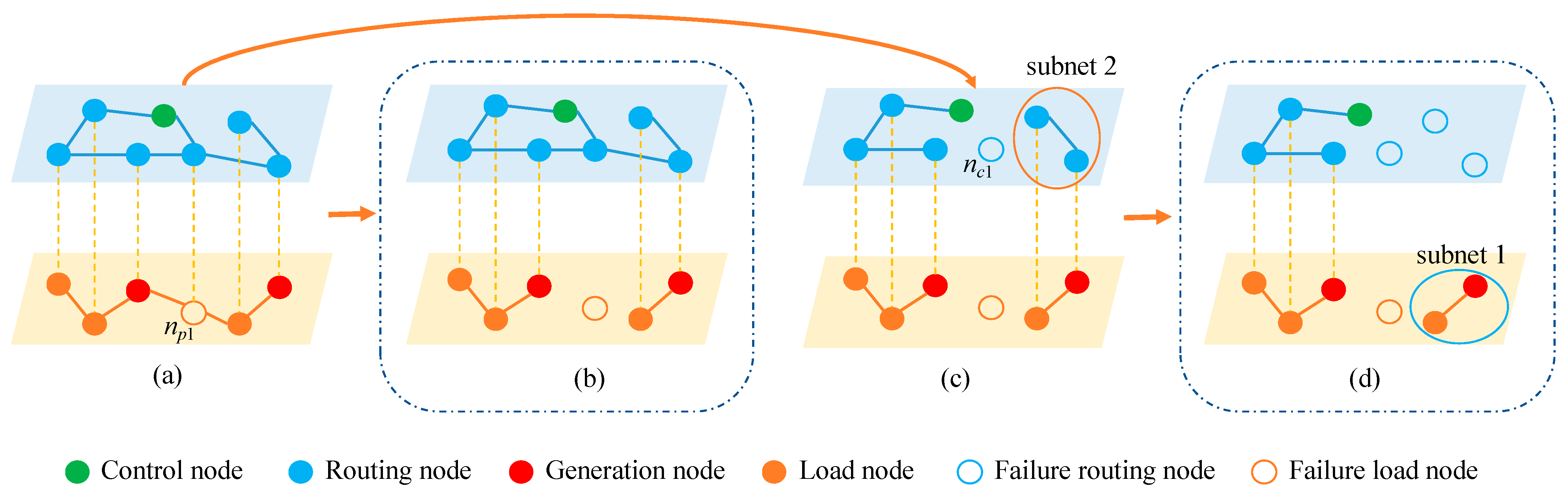

3.1. Failure Triggering Mechanism

3.2. Cascading Failure Process

3.3. Robustness Metrics

4. Results and Discussions

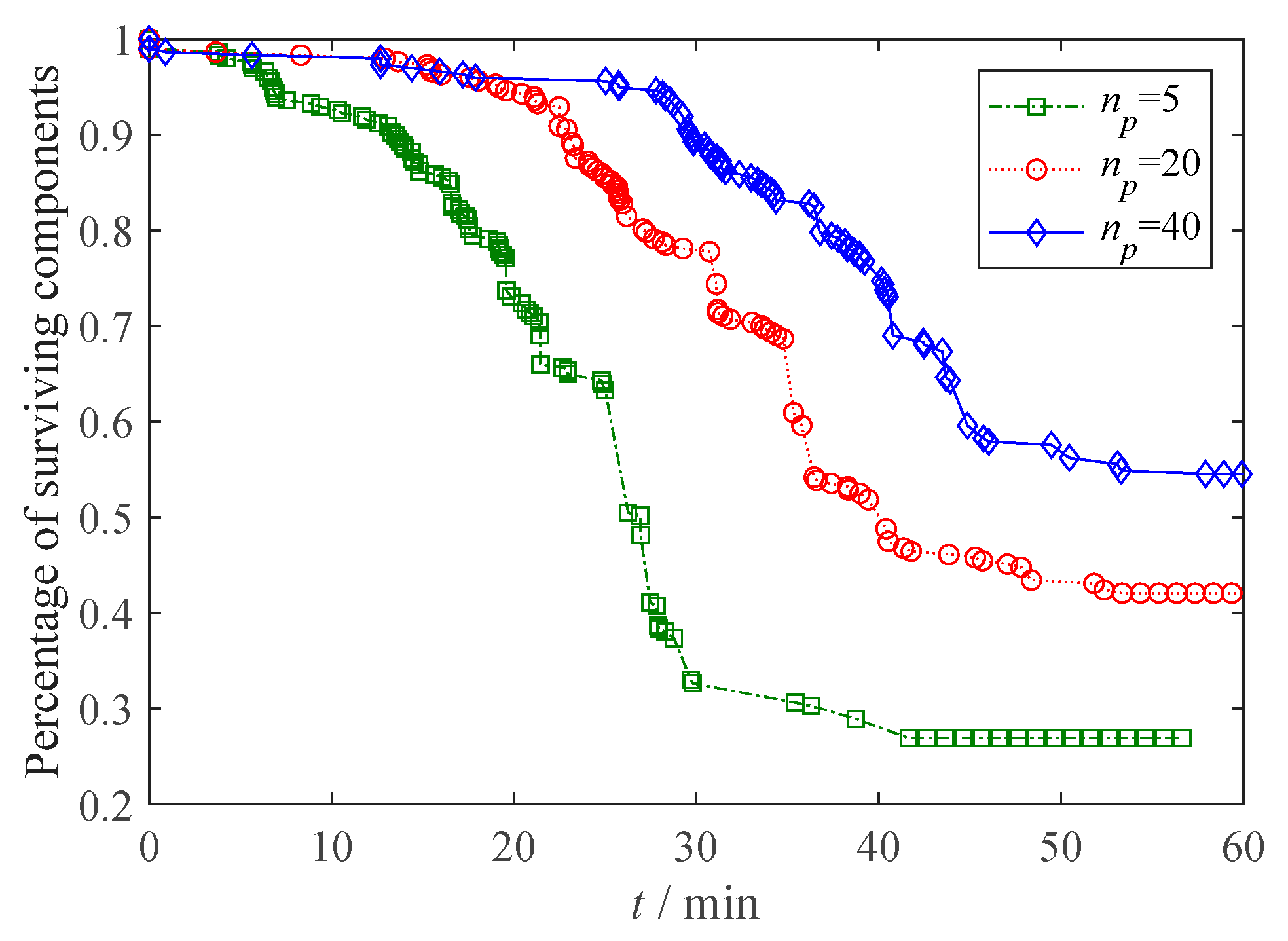

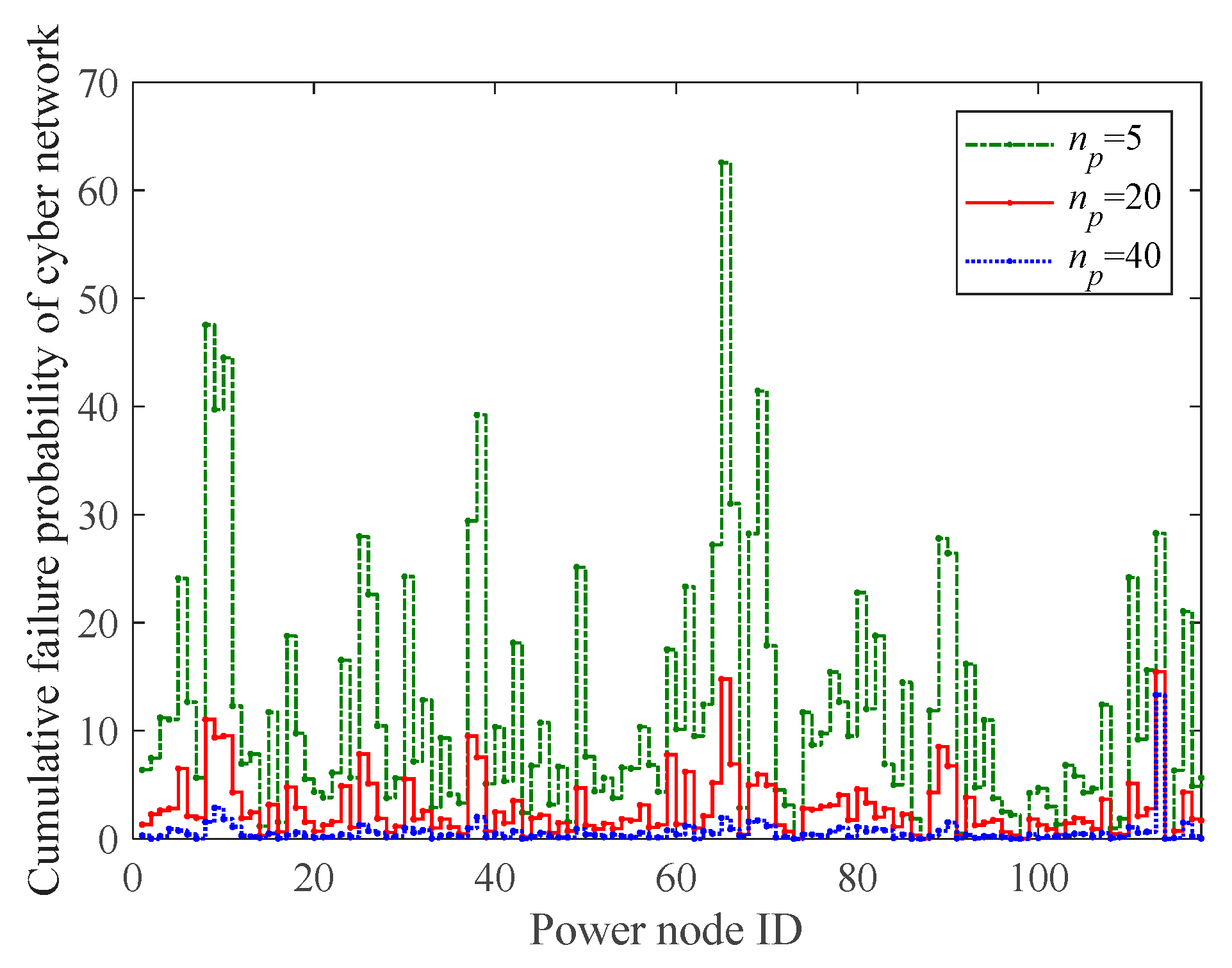

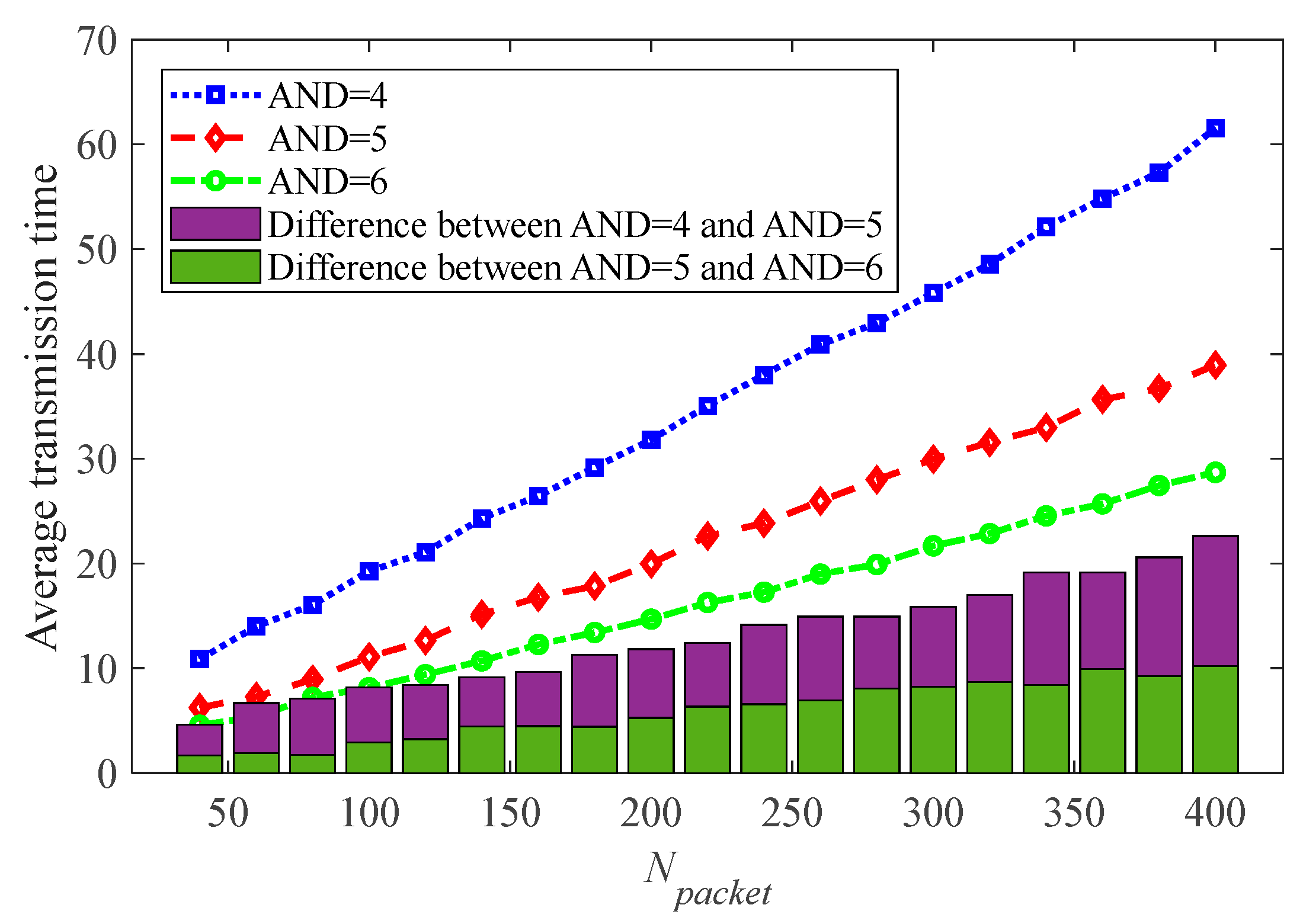

4.1. Impact of Functional Attribute of Cyber Network

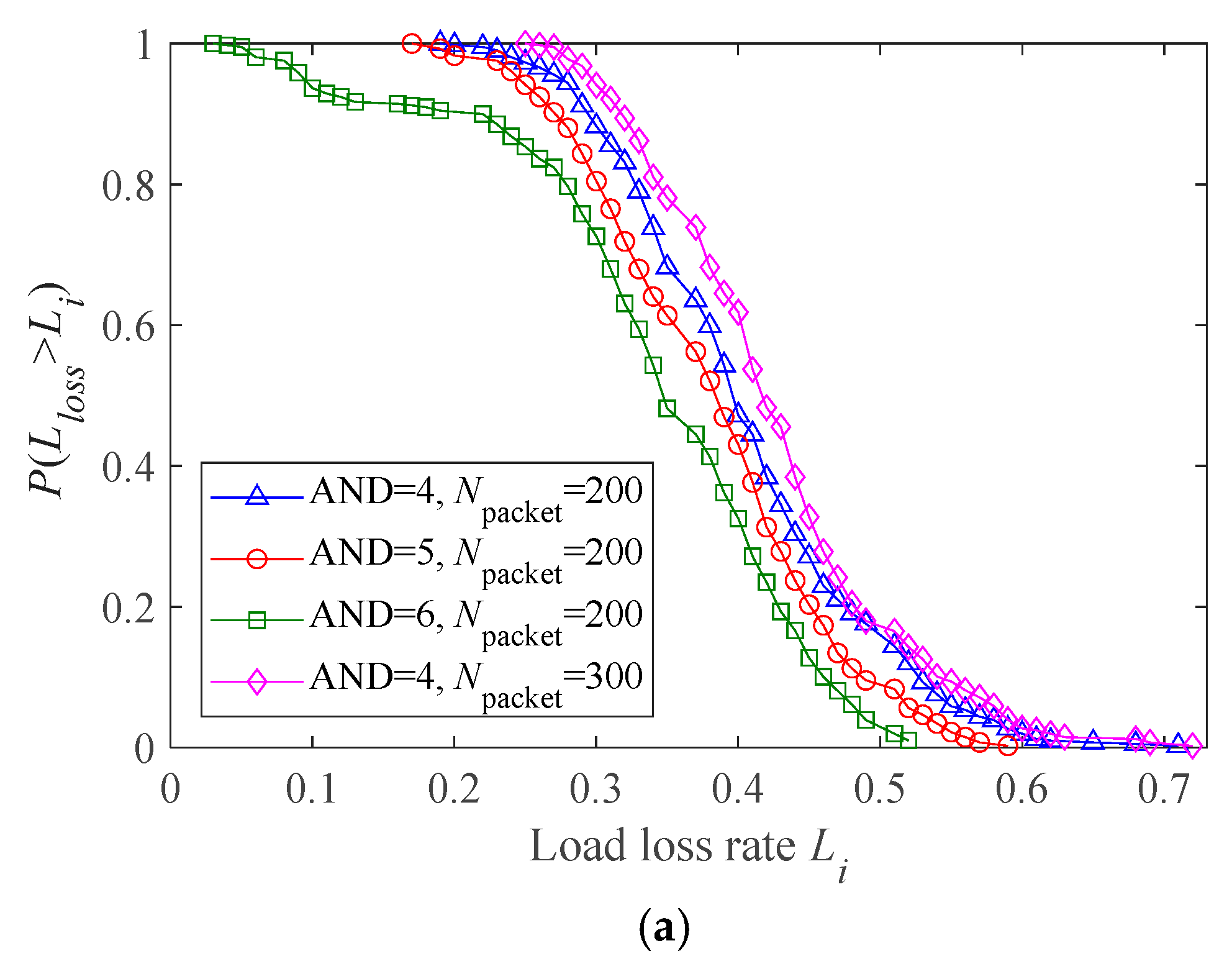

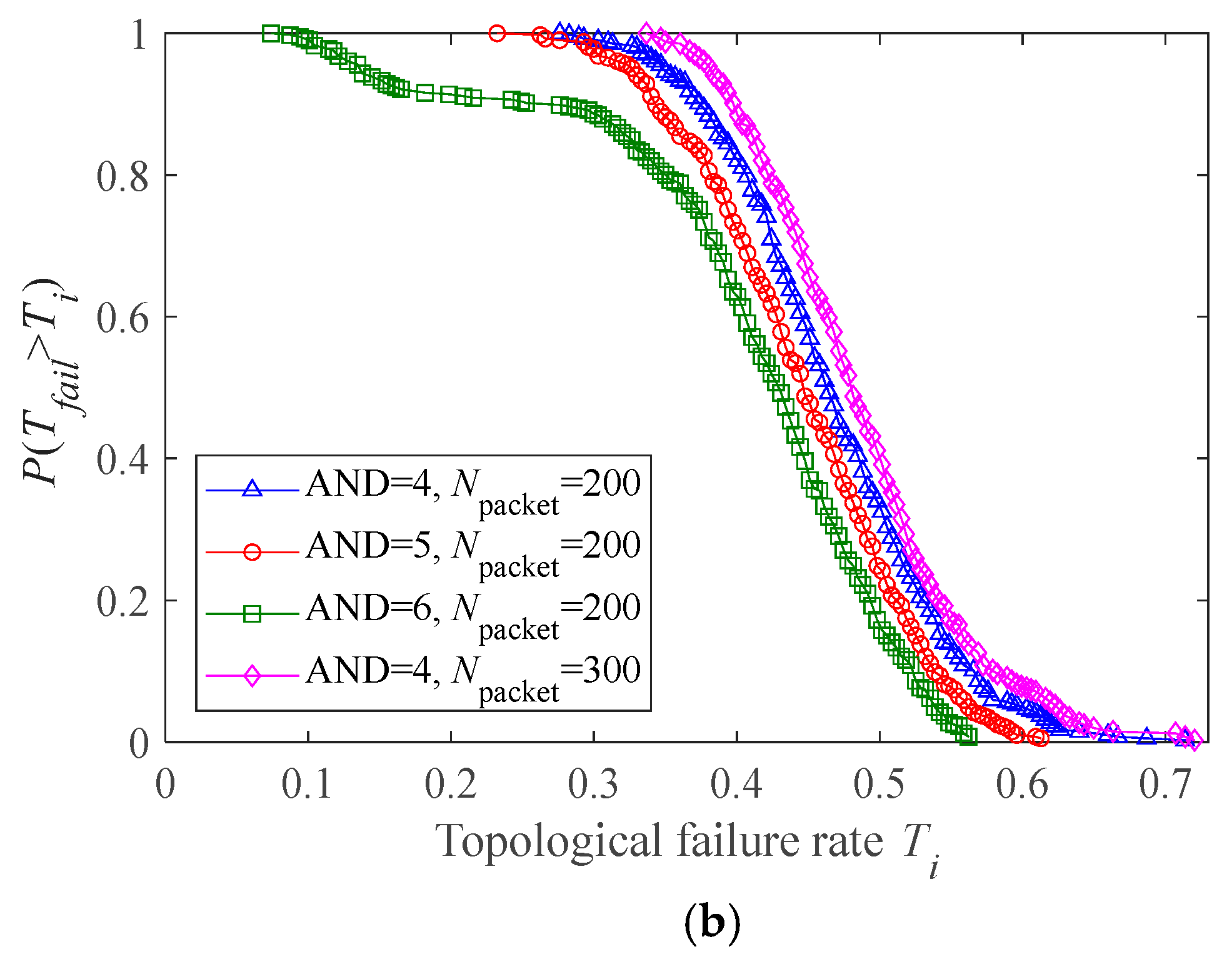

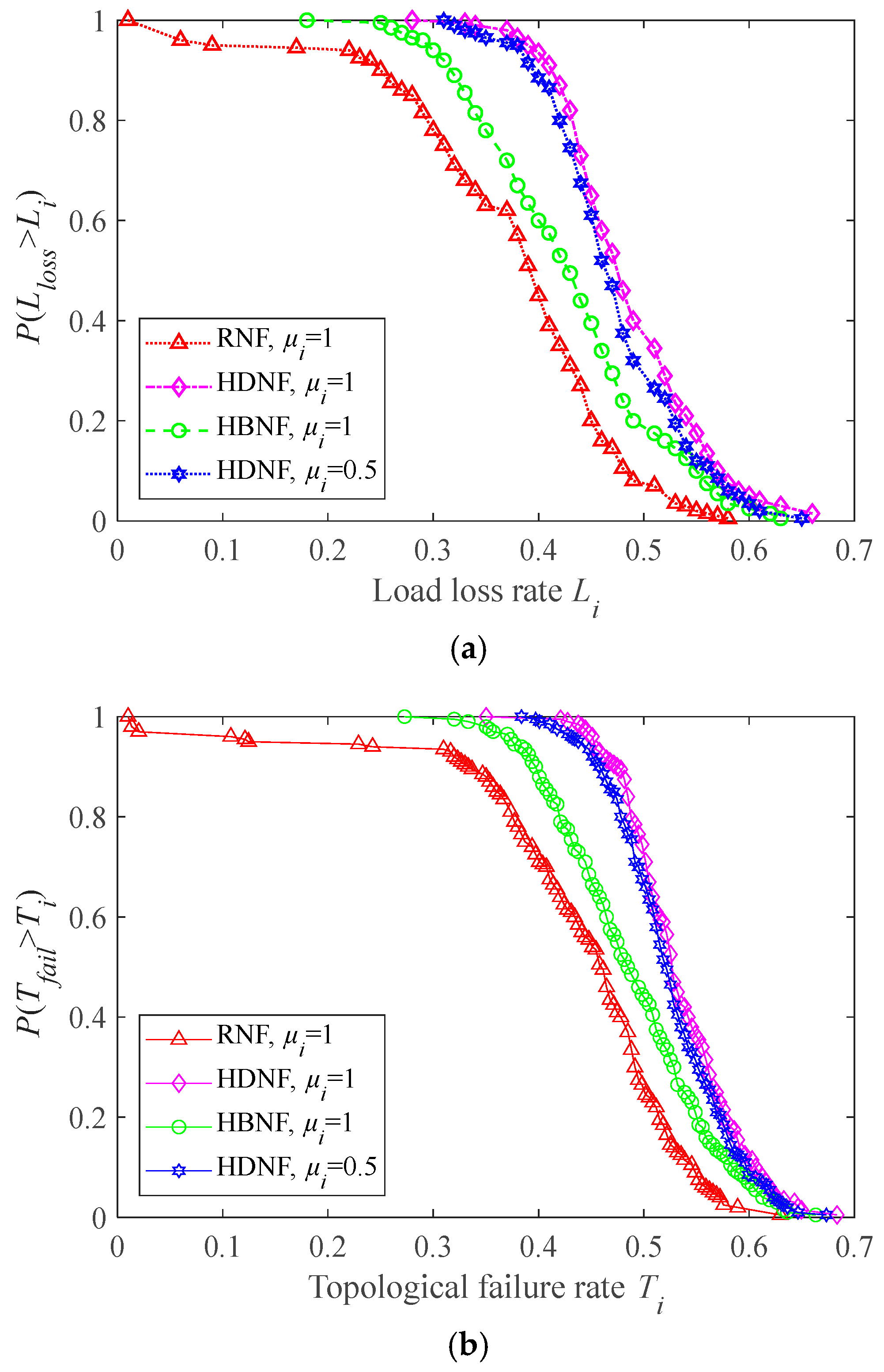

4.2. Impact of Structural Attribute of Cyber Network

4.3. Impact of Initial Failure Mode

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, H.B.; Wan, S.Q.; Li, J.H.; Li, S.Y.; Hou, W.R.; Su, L.Y. Enhancing the robustness of cyber-physical power systems: From the perspective of information flow control. Int. J. Electr. Power 2025, 172, 111082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Teng, Y.; Guerrero, J.M.; Siano, P.; Sun, X. Analysis of failure propagation in cyber-physical power systems based on an epidemic model. Energies 2023, 16, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Ding, F.; Utkarsh, K.; Liu, W.; O’Malley, M.J.; Barnett, J. On vulnerability and resilience of cyber-physical power systems: A review. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 2367–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.S.; Wu, G.Y.; Cassandro, R.; Wang, H.M. A review of resilience metrics and modeling methods for cyber-physical power systems (CPPS). IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2024, 73, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tse, C.K. Cascading failure of cyber-coupled power systems considering interactions between attack and defense. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Papers. 2019, 66, 4323–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Peng, M.F.; Zhang, J.; Shao, H.; Liu, Y.C. A cascading failure model of cyber-coupled power system considering virus propagation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2024, 636, 129549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprabhath Koduru, S.; Machina, V.S.P.; Madichetty, S. Cyber attacks in cyber-physical microgrid systems: A comprehensive review. Energies 2023, 16, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldyrev, S.V.; Parshani, R.; Paul, G.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks. Nature 2010, 464, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Jiang, C.; Qian, J.F. Robustness of interdependent networks with different link patterns against cascading failures. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2014, 393, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Chen, S.M.; Nie, S.; Ma, F.; Guan, J.J. Robustness analysis of interdependent networks under multiple-attacking strategies. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2018, 496, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yue, D.; Dou, C.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, J. Robustness of cyber-physical power systems in cascading failure: Survival of interdependent clusters. Int. J. Electr. Power 2020, 114, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Yağan, O. Robustness of interdependent cyber-physical systems against cascading failures. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Wu, J.J.; Xia, Y.X.; Zhang, X. Robustness of interdependent power grids and communication networks: A complex network perspective. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. II Exp. Briefs. 2018, 65, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, B. Robustness assessment of weakly coupled cyber-physical power systems under multi-stage attacks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 231, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, H.W.; Tse, C.K. Assessing the robustness of cyber-physical power systems by considering wide-area protection functions. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2022, 12, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, W. Decentralized graphical-representation-enabled multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for robust control of cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2024, 73, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimada-Ojuolape, B.; Teh, J.S. Composite reliability impacts of synchrophasor-based DTR and SIPS cyber–physical systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3927–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimada-Ojuolape, B.; Teh, J.S.; Lai, C.M. Enhancing power grid reliability with PMU placement in flexibly rated cyber-physical systems. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.W.; Su, Q.Y.; Li, J. Secure tracking control and attack detection for power cyber-physical systems based on integrated control decision. IEEE Trans. Inf. Foren. Sec. 2025, 20, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.D.; Wu, Z.G. Multi-objective false data injection attacks of cyber–physical power systems. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. II Exp. Briefs. 2022, 69, 3924–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Başar, T. Robust and resilient control design for cyber-physical systems with an application to power systems. In Proceedings of the 2011 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European Control Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–15 December 2011; pp. 4066–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, T.; Abdennebi, M.; Zhu, M. Methods for evaluating critical lines and nodes in cyber-physical power systems from three network perspectives. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, K.S.; Du, W.; Xu, X.Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.X. Resilience assessment for hybrid AC/DC cyber-physical power systems under cascading failures. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2025, 74, 3442–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhou, B.; Yang, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, J. Computing optimal resilience-oriented operation of distribution systems considering heterogenous consumer-side microgrids. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electr. 2025, 71, 5866–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.M.; Jalili, M. Power grids as complex networks: Resilience and reliability analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119010–119031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echenique, P.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Moreno, Y. Improved routing strategies for Internet traffic delivery. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2004, 70, 056105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Peng, M.F.; Tse, C.K. Cascading failure analysis of cyber physical power systems considering routing strategy. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. II Exp. Briefs 2023, 70, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xiahou, K.; Du, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z. Security assessment of cascading failures in cyber-physical power systems with wind power penetration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 4480–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Chen, G.; Tang, F.; Wei, D. Improving interdependent networks robustness by adding connectivity links. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2016, 444, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Du, C.; Sui, W.; Xu, X. Data traffic capability of double-layer network based on coupling strength. Acta Phys. Sin. 2020, 69, 188901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Zhan, C.J.; Tse, C.K. Effects of cyber coupling on cascading failures in power systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circ. Syst. 2017, 7, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.J.; Tse, C.K.; Small, M. A general stochastic model for studying time evolution of transition networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2016, 464, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, M.H.; Wang, Z.F. Stochastic cascading failure model with uncertain generation using unscented transform. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Huang, X. Robustness improvement strategy of cyber-physical systems with weak interdependency. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 2023, 229, 108837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE 118-Bus System. Available online: https://icseg.iti.illinois.edu/ieee-118-bus-system/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Su, Q.Y.; Sun, J.X.; Li, J. Vulnerability analysis of cyber-physical power systems based on failure propagation probability. Int. J. Elec. Power 2024, 157, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Processing Rate np | Robustness Metric R |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 1.4435 |

| 2 | 20 | 1.8492 |

| 3 | 40 | 2.4423 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shao, H. Robustness Assessment of Cyber-Physical Power Systems Considering Cyber Network Performance. Technologies 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010022

Gao X, Liu Y, Zhang X, Shao H. Robustness Assessment of Cyber-Physical Power Systems Considering Cyber Network Performance. Technologies. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Xingle, Yanchen Liu, Xi Zhang, and Hua Shao. 2026. "Robustness Assessment of Cyber-Physical Power Systems Considering Cyber Network Performance" Technologies 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010022

APA StyleGao, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., & Shao, H. (2026). Robustness Assessment of Cyber-Physical Power Systems Considering Cyber Network Performance. Technologies, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010022