Abstract

Background: Recovery following incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI) remains challenging, with conventional rehabilitation often emphasizing compensation over functional restoration. As most new spinal cord injury cases preserve some motor or sensory pathways, there is increasing interest in therapies that harness neuroplasticity. Robotic exoskeletons provide a promising means to deliver task-specific, repetitive gait training that may promote adaptive neural reorganization. This feasibility study investigates the feasibility, safety, and short-term effects of exoskeleton-assisted walking in individuals with degenerative iSCI. Methods: Two cooperative male patients (patients A and B) with degenerative iSCI (AIS C, neurological level L1) participated in a four-week intervention consisting of one hour of neuromotor physiotherapy followed by one hour of exoskeleton-assisted gait training, three times per week. Functional performance was assessed using the 10-Meter Walk Test, while gait quality was examined through spatiotemporal gait analysis. Vendor-generated surface electromyography (sEMG) plots were available only for qualitative description. Results: Patient A demonstrated a clinically meaningful increase in walking speed (+0.15 m/s). Spatiotemporal parameters showed mixed and non-uniform changes, including longer cycle, stance, and swing times, which reflect a slower stepping pattern rather than improved efficiency or coordination. Patient B showed a stable walking speed (+0.03 m/s) and persistent gait asymmetries. Qualitative sEMG plots are presented descriptively but cannot support interpretations of muscle recruitment patterns or neuromuscular changes. Conclusions: In this exploratory study, exoskeleton-assisted gait training was feasible and well tolerated when combined with conventional physiotherapy. However, observed changes were heterogeneous and do not allow causal or mechanistic interpretation related to neuromuscular control, muscle recruitment, or device-specific effects. These findings highlight substantial inter-individual variability and underscore the need for larger controlled studies to identify predictors of response and optimize rehabilitation protocols.

1. Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious neurological condition associated with substantial reductions in quality of life and high demands on healthcare systems. Globally, an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 new cases occur each year, with approximately 60% classified as incomplete injuries—defined by the partial preservation of motor and/or sensory function below the level of the lesion [1,2]. Incomplete SCIs are clinically heterogeneous, leading to considerable variability in functional impairments and posing complex challenges for rehabilitation planning. Over the past decade, epidemiological trends have shown an increase in the average age at injury and a higher proportion of incomplete cases, further complicating rehabilitation strategies and long-term management [3].

Traditional rehabilitation strategies, such as autonomy training, muscle strengthening above the level of injury, and the use of assistive devices, primarily aim to compensate for functional deficits and improve quality of life [4]. However, emerging evidence highlights the pivotal role of central nervous system (CNS) plasticity—the capacity of the brain and spinal cord to reorganize structurally and functionally in response to injury—in driving recovery [5]. This post-developmental plasticity is underpinned by mechanisms such as synaptic potentiation and depotentiation, which are modifiable through targeted experience and intervention [6]. Importantly, the selection of rehabilitation approaches must be carefully considered, as neuroplastic reorganization following deafferentation may lead to maladaptive outcomes if improperly directed [6]. Functional neuroimaging studies, particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have demonstrated cortical reorganization within motor and premotor regions, underscoring the essential role of neuroplasticity in functional recovery following SCI [7]. While neuroplasticity is essential for functional recovery following SCI, excessive or aberrant reorganization can negatively affect clinical outcomes, such as the development of neuropathic pain. Although conventional rehabilitation approaches remain the standard of care, increasing attention is being directed toward invasive and non-invasive neuromodulation techniques, which aim to modulate neural excitability and enhance motor recovery [8].

Among recent innovations in neurorehabilitation, robotic exoskeletons have emerged as promising tools. These devices are designed to engage spinal locomotor circuits, particularly central pattern generators (CPGs), which may require targeted training to regain function in cases of incomplete injury [9]. Robotic exoskeletons, which mimic human joint movements through powered actuators, enable individuals with neurological impairments to stand and walk with support.

In addition to improving gait efficiency, exoskeleton-assisted training has been associated with neuroplastic adaptations within the CNS, promoting the reorganization of motor pathways essential for long-term recovery [10,11]. These adaptations may facilitate the transfer of functional gains from therapy sessions to daily activities, even in the absence of the device. Furthermore, exoskeleton use has been shown to reduce muscular fatigue by enabling more physiological activation patterns and more balanced load distribution during gait, thereby enhancing patient autonomy [12].

Importantly, personalization of exoskeleton parameters and training protocols according to individual needs appears to optimize outcomes further, accelerating motor recovery and improving functional capacity [13]. Although initial findings are encouraging, the current evidence base is limited by small sample sizes, methodological variability, and the inclusion of heterogeneous patient populations—often differing in injury completeness, chronicity, and baseline functional status. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying exoskeleton-induced neuroplasticity better and to develop standardized training protocols that support their effective integration into clinical rehabilitation. Recognizing the constraints of a two-case design, the present work is therefore positioned as a hypothesis-generating feasibility study that provides a descriptive account of within-subject changes associated with a four-week program of exoskeleton-assisted gait training in adults with degenerative incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI). It asks whether the program can be delivered as intended with acceptable procedural fidelity, whether observable pre- to post-results in functional performance and neuromuscular control emerge within each case, and whether the direction and magnitude of these results are sufficiently consistent to justify a subsequent controlled study. Accordingly, this feasibility study focuses on a very specific subgroup of the SCI population—older males with degenerative, L1-level incomplete spinal cord injury—and findings should be interpreted within this limited clinical context

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size Rationale

This study was conceived as a prospective feasibility multiple-case investigation, with the primary objective of evaluating all patients deemed eligible for exoskeleton-assisted gait training in our unit and characterizing their clinical, gait, and neuromuscular profiles under standardized exoskeleton protocols. The target sample size of two participants was defined a priori, based on (i) the number of patients who had met similar eligibility criteria for exoskeleton-assisted gait training in the previous years in our unit, and (ii) the operational constraints of the service (availability of the device and requirement of two trained therapists per session). Over a fixed 12-month recruitment period, exactly two patients fulfilled all predefined clinical and device-specific criteria, and both were included; thus, the final sample represents the entire consecutive eligible population for this feasibility phase. The design is descriptive and does not involve inferential statistics or causal claims. Its purpose is to generate individual-level results that will refine outcome selection, dosing, and procedures for a subsequent controlled study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the CONSORT reporting guidelines [14], and was approved by the institutional ethics committee for Clinical Experimentation of the Veneto Region (CESC) (No. 171A/CESC, 20 April 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from both participants before data collection. This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03443700).

2.2. Participants

Consecutive admissions with degenerative, iSCI were screened at IRCCS San Camillo Hospital (Venice, Italy) between 1 January and 31 December 2023. During this period, six adults were evaluated for exoskeleton-assisted gait training against predefined device and safety criteria. Four were excluded a priori: two did not meet the Ekso NR femur-length requirement, one experienced clinical deterioration before training could begin, and one had severe lower-limb spasticity (Modified Ashworth Scale score ≥3 in ankle dorsiflexors). The remaining two male patients, aged 77 and 74, fulfilled all eligibility criteria and were included. No other eligible patients were omitted.

In both cases, a degenerative origin of the incomplete spinal cord injury was confirmed by concordant clinical and neuroradiological findings. All patients underwent lumbar and thoracolumbar MRI demonstrating multilevel degenerative lumbar canal stenosis with central narrowing at L1 compressing the conus medullaris/lower thoracolumbar cord, in the absence of traumatic lesions, inflammatory myelopathy, or isolated radiculopathy/cauda equina patterns. MRI scans were reviewed jointly by an experienced neuroradiologist and a spine neurologist. Neurological status was classified using the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) according to the ISNCSCI protocol, performed by the same physician in both participants.

According to the ASIA Impairment Scale, both included patients were classified as AIS C with a neurological level of injury at L1, indicating preservation of motor function below the lesion, with more than half of the key muscles below that level scoring less than 3. MRI demonstrated multilevel lumbar spinal canal stenosis with central narrowing at L1 compressing the conus medullaris and lower thoracolumbar cord, supporting a diagnosis of degenerative iSCI of central origin rather than isolated radiculopathy or cauda equina syndrome.

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of degenerative iSCI (AIS C), lumbar involvement with residual motor function, clinical stability, and suitability for exoskeleton training according to the Ekso Bionics checklist. Exclusion criteria included: severe spasticity (Modified Ashworth Scale > 2), musculoskeletal deformities preventing exoskeleton fitting, severe cardiorespiratory comorbidities, or cognitive deficits interfering with training participation. Detailed clinical and exoskeleton setup characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and Ekso exoskeleton setup parameters.

Patient A had undergone spinal stabilization surgery two years earlier and did not present with spasticity in the lower limbs. He exhibited marked muscle atrophy in the gluteal region, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior of both legs, more pronounced on the left side. Manual muscle testing with the Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS) showed bilateral deficits across L2–S1—hip flexors (iliopsoas, L2) Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 2, knee extensors (quadriceps femoris, L3) Right: LEMS = 3; Left: LEMS = 3, ankle dorsiflexors (tibialis anterior, L4) Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 2, great-toe extensor (extensor hallucis longus, L5) Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 2, and ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius–soleus, S1) Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 2. These values indicate preserved voluntary activation, predominantly at or below antigravity levels, with limited capacity to generate force against resistance. Despite these deficits, the patient was able to perform postural transitions independently and ambulate with a walking frame. His lower back pain was moderate, with a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score of 4/10, and was managed with analgesic medication.

Patient B had not undergone surgery and showed no signs of spasticity. Clinical examination revealed generalized hypotonia in the right lower limb and a marked deficit in weight-bearing capacity, consistent with incomplete spinal cord involvement. LEMS demonstrated asymmetric lower limb strength, i.e., iliopsoas—Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 4, quadriceps femoris—Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 4, tibialis anterior—Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 4, extensor hallucis longus—Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 4, and gastrocnemius–soleus—Right: LEMS = 2; Left: LEMS = 4, indicating preserved voluntary movement bilaterally but reduced resistance to gravity and external force, particularly on the right. Despite these impairments, the patient was able to perform postural transitions and ambulate short distances with the aid of a four-wheeled walker.

The inclusion of only two participants reflects the exploratory nature of this study, rather than aiming for statistical generalization. Furthermore, this study was designed to provide an in-depth description of the feasibility, safety, and adherence to exoskeleton-assisted gait training in a clinically homogeneous subgroup of patients with degenerative incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI) at the thoracolumbar level. This focused approach minimizes variability associated with heterogeneous lesions and anthropometrics, allowing the protocol to be tested under controlled and replicable conditions. Although the small sample does not permit causal inference, the detailed clinical and functional observations gathered offer preliminary insights that can guide future controlled studies with larger cohorts.

2.3. Intervention Protocol

Before initiating exoskeleton-assisted gait training, both patients underwent a comprehensive baseline assessment to determine their eligibility. A physician conducted a clinical examination to confirm medical suitability and completed the ASIA Impairment Scale to evaluate neurological function. Each patient was then assessed by a physiotherapist experienced in using the Ekso NR exoskeleton (Ekso Bionics, Holding Richmond, CA, USA). Anthropometric and functional parameters of the lower limbs were recorded. Spasticity was evaluated using the Modified Ashworth Scale, and muscle strength with the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. All data were cross-referenced with the manufacturer’s eligibility checklist to confirm functional suitability for device-assisted gait.

The Ekso NR is a powered, overground lower-limb exoskeleton that provides motorized assistance at the hip and knee joints, while the ankles are unactuated. Assistance is trajectory controlled, meaning the device drives the hip and knee through predefined joint trajectories while allowing therapist customization of ranges and timing. Timing of assistance is phase-specific: during swing, the motors assist hip and knee flexion to track the programmed swing trajectory; during stance, the device provides stance support to maintain knee and hip extension as configured. Magnitude of assistance is set using device-native parameters. Swing assistance can be set to a maximal mode that fully drives the programmed trajectory, or to adaptive modes that scale the motor contribution relative to patient effort. Stance support can be configured from minimal to high support according to safety and tolerance. The device does not provide absolute joint torque readouts; therefore, assistance is reported using assist modes and qualitative levels rather than newton-meter values.

In this study, exoskeleton parameters were individualized according to quantitative clinical criteria. Initial configuration was set using the manufacturer’s conversion table (hip width, femur and shank length) and then adjusted session by session: hip and knee flexion ranges (0–45°) were increased in 5–10° steps according to improvement in swing-phase flexion, while assist mode (from FirstStep to ProStep+), walking speed (0.2–0.4 m/s), step length and swing time were increased only if knee and trunk stability, adequate weight shift and toe clearance were maintained, with tolerable fatigue and pain and in the absence of cardiorespiratory or autonomic distress.

With the assistance of two physiotherapists, the patients, who were initially able to take only a few steps using a deambulatory, were positioned within the exoskeleton structure. They participated in a structured rehabilitation program consisting of one hour of conventional neuromotor physiotherapy followed by one hour of exoskeleton-assisted gait training. The program spanned four weeks, with three sessions per week, totaling 12 sessions. The first week focused on preparatory activities, including postural transitions for the exoskeleton setting, sit-to-stand exercises, and lateral weight-shifting tasks, performed with and without auditory feedback. From the second week onward, overground gait training in FirstStep mode, and progressed to ProStep+ mode as patient participation increased and safety criteria were met. Assessments were conducted within 3 days before the start of the program and within 3 days after completion to ensure temporal consistency.

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Functional Assessment of Gait Performance

To assess walking speed, the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) was administered at baseline and after the four-week intervention. Both participants were able to ambulate with the aid of a 4-wheels walker before the intervention. The 10MWT measures self-selected walking speed over a short distance: gait speed was calculated by dividing the distance walked (10 m) by the time taken to complete the test and expressed in meters per second (m/s). Testing was performed at the patients’ self-selected speed using their usual assistive devices, which were kept identical across pre- and post-intervention assessments. No orthoses were used.

2.4.2. Instrumented Gait Analysis

Spatiotemporal parameters were recorded using a wearable inertial sensor (G-Sensor; BTS FreeEMG, BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy) positioned over the lower lumbar spine per the manufacturer’s protocol. Signals were processed with the vendor algorithms to derive cycle time, stance and swing times and phases, double-support, opposite-foot contact, cadence, and speed. Each overground trial comprised ~50 steps at a self-selected pace; after artifact rejection, ~20–30 strides per trial were retained for analysis, and parameters were averaged across strides.

A composite Gait Quality Index (GQI) was also computed by the BTS EMG-Analyzer software (BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy) a unitless 0–100 score that summarizes deviation from a normative reference pattern. In brief, GQI combines multiple spatiotemporal features (for example, variability, interlimb symmetry, and coordination metrics) after normalization to a reference dataset, yielding higher values for gait patterns that are more consistent and symmetric and therefore closer to the reference. Minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) have not been established for either the Gait Quality Index or the symmetry ratios used in this study. As a result, numerical changes in these metrics cannot be interpreted as clinically meaningful improvements or deteriorations. GQI and symmetry values must therefore be considered descriptive indicators rather than validated clinical outcomes. Both the GQI and symmetry ratios are sensitive to changes in gait speed and cadence. Variations in walking speed between pre- and post-intervention assessments may influence these composite indices independently of true changes in gait quality. Therefore, observed fluctuations in GQI or symmetry values may partially reflect speed-dependent effects rather than underlying biomechanical or functional adaptations.

Gait recordings were performed during overground walking trials at a self-selected pace. Each measurement was based on an average of multiple gait cycles to improve reliability and reduce variability. Baseline and post-intervention values were compared to determine treatment-related changes in gait quality and functional mobility.

2.5. Surface Electromyography

Surface EMG was recorded exclusively during exoskeleton-assisted walking. No separate maximal voluntary contractions (MVCs) were obtained. For MVCs to be task-relevant in this context, they would have needed to be performed in an upright, weight-bearing position comparable to exoskeleton-assisted gait. In this frail degenerative iSCI cohort, attempting standing MVCs outside the exoskeleton was considered clinically inappropriate because of poor postural control, increased fall risk, and the potential exacerbation of pain and spasticity. Under these conditions, patients are also unlikely to generate a true maximal effort. Therefore, EMG amplitudes for each muscle and limb are expressed relative to the highest value recorded within each walking trial and are used for descriptive visualization only. sEMG was recorded bilaterally using the BTS FreeEMG system from tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius, soleus, hamstrings, quadriceps, and gluteus medius, with electrode placement following SENIAM recommendations [15]. Signals were acquired with the system’s hardware band-pass filter (20–450 Hz), full-wave rectified, and low-pass filtered at 10 Hz to obtain linear envelopes. Gait cycles were segmented using gait events (heel-strike and toe-off) as identified by the instrumented system, time-normalized to 0–100% of the gait cycle and averaged across consecutive strides for descriptive visualization.

2.6. Feasibility and Adherence

Feasibility outcomes included adherence, safety, tolerance, and session-by-session progression. Adherence was defined as the proportion of scheduled sessions completed. Safety was monitored continuously by the treating physiotherapist and included documentation of adverse events (falls, skin injury, hemodynamic instability, autonomic symptoms). Tolerance and fatigue were tracked through session-level clinical notes describing perceived exertion, discomfort, and need for rest breaks.

3. Results

3.1. Gait Speed

Table 2 shows mixed and non-uniform changes in spatiotemporal parameters. For Subject A, cycle time, stance time, and swing time increased bilaterally, reflecting a slower and more cautious stepping pattern rather than increased efficiency or coordination. These changes should not be interpreted as directional improvements but as variations that occurred during the instrumented assessment. Following the four-week exoskeleton-assisted training program, Subject A increased self-selected gait speed from 0.56 m/s to 0.71 m/s (Δ = 0.15 m/s; ~26.8%), exceeding the commonly used “substantial meaningful change” threshold of ~0.10 m/s [16,17,18]. In contrast, Subject B changed from 0.20 m/s to 0.23 m/s (Δ = 0.03 m/s), below the small meaningful change threshold of ~0.05 m/s. Both assessments were conducted with the same assistive device used by each participant.

Table 2.

Spatiotemporal gait parameters for both participants before and after the intervention.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Gait Analysis

Subject A showed mixed and non-uniform changes in spatiotemporal parameters following the intervention. Post-training data demonstrated variations such as reduced swing-time variability on the left side and differences in single-support and opposite-foot-contact values compared with baseline. Double-support time also changed. These findings are presented descriptively and should not be interpreted as evidence of improved symmetry, stability, coordination, or dynamic balance.

In Patient A, GQI showed an asymmetric change, increasing from 81.2 to 85.4 on the right side and decreasing slightly from 88.5 to 84.0 on the left side.

In contrast, Subject B displayed limited changes in spatiotemporal gait parameters. Minor fluctuations in swing and stance phases were observed, with an increase in stance time and double support phase on the right side, possibly indicating a compensatory strategy to enhance stability. GQI values remained relatively stable, with a marginal improvement on the right (76.9 to 78.9) and a decrease on the left (78.9 to 74.6), suggesting persistent gait asymmetry. Detailed parameter values are presented in Table 2.

3.3. sEMG Analysis

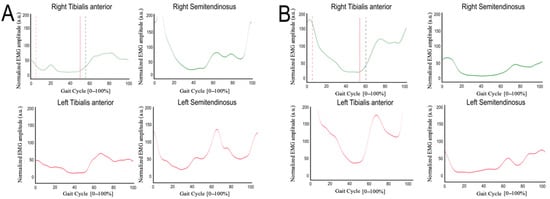

Post-intervention gait analysis and sEMG plots for Subject A revealed visually observable differences in the appearance of the tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius–soleus, quadriceps, and hamstring traces compared with the baseline. However, because raw EMG signals were not archived and amplitudes were arbitrarily scaled, these plots cannot be used to infer phase-specific activation, recruitment patterns, or changes in muscle timing. The observed traces are therefore presented solely for qualitative illustration and should not be interpreted as evidence of neuromuscular or spatiotemporal improvement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Normalized surface EMG (sEMG) profiles averaged across gait cycles during exoskeleton-assisted walking, shown for pre- (A) and post-intervention (B) conditions. The x-axis represents the gait cycle normalized to 0–100%, and the y-axis represents normalized EMG amplitude expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.), scaled to the maximum value recorded within each walking trial. Stance and swing phases are not explicitly indicated in the plots, as the available vendor-generated outputs do not allow reliable phase demarcation. EMG profiles are provided for qualitative visualization and do not support quantitative interpretation of timing or amplitude.

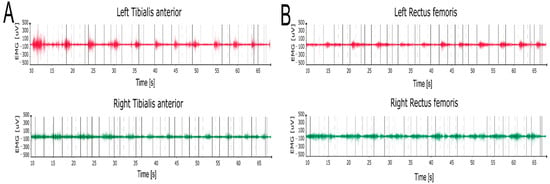

In Subject B, the available sEMG plots showed visual differences in the amplitude and shape of gastrocnemius–soleus, tibialis anterior, and hamstring traces before and after the intervention. However, because raw EMG signals were not archived, amplitudes cannot be normalized, timing metrics cannot be computed, and filtering or artifact-processing parameters cannot be verified. As a result, these qualitative plots cannot be interpreted in terms of muscle effort, postural stability, or motor control. The traces are presented solely for descriptive illustration and cannot be linked to changes in spatiotemporal gait parameters or functional outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

sEMG recordings of the tibialis anterior (A) and rectus femoris (B) muscles during overground walking, recorded post-intervention.

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility, Adherence, and Individual Variability in Response

This study explored the feasibility of a four-week combined program of conventional neuromotor physiotherapy and exoskeleton-assisted gait training in two individuals with degenerative iSCI. Across sessions, both participants demonstrated progressive adaptation to the exoskeleton training, including advancement from FirstStep to ProStep+ assist modes and tolerance of higher programmed walking speeds by the final sessions. Both participants completed all scheduled sessions without adverse events. Session notes indicated good tolerance, with manageable fatigue and no reports of excessive discomfort. However, feasibility data remain limited by the absence of device-derived metrics such as step count, assistance levels, and time spent upright.

Subject A increased self-selected gait speed from 0.56 to 0.71 m/s (Δ 0.15 m/s; 26.8%). It should be noted that the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) thresholds used to contextualize changes in gait speed were derived from populations that differ from individuals with chronic degenerative spinal cord injury. These values are therefore reported as reference benchmarks rather than definitive indicators of clinical significance for this specific population. Because raw EMG signals were not archived, amplitudes could not be normalized, timing metrics could not be computed, and filtering parameters could not be verified. Consequently, EMG plots cannot be linked to spatiotemporal changes or interpreted in terms of recruitment, timing, or neuromuscular adaptation. GQI values changed asymmetrically (+4.2 right, −4.5 left) and are reported descriptively only.

Subject B showed a smaller change in self-selected gait speed (0.20 to 0.23 m/s; Δ 0.03 m/s). Qualitative EMG traces differed visually from baseline, but given the limitations of the available EMG data, no inferences can be made regarding activation timing, recruitment, or relationships with gait parameters. Changes in GQI were minimal and descriptive. Although both participants were classified as AIS C at L1, they differed in lower-limb strength distribution, gait asymmetry, assistive device use, and prior surgical history. These differences illustrate the heterogeneity typical of degenerative iSCI. Given the very small sample size and feasibility design, no conclusions can be drawn about factors that may influence responsiveness to training. The contrasting individual profiles should therefore be interpreted as descriptive, exploratory observations that may help inform the design of future controlled studies, rather than as indications of response patterns or predictors.

4.2. Clinical Implications, Study Limitations, and Future Study Directions

The observed results support the practicality of using a robotic exoskeleton as a complementary component of multimodal rehabilitation in selected patients with residual voluntary control and clinical stability. These findings are preliminary and descriptive, not confirmatory. This is consistent with reports supporting integration of robotic systems into neurorehabilitation for chronic, incomplete SCI [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The contrasting neuromuscular patterns between participants underscore the need for individualized strategies. Subject A showed visually different EMG traces, but these cannot be interpreted as phase-specific activation, whereas Subject B exhibited persistent asymmetries and compensatory recruitment, suggesting that baseline motor profiles should guide protocol tailoring.

The powered exoskeleton may complement conventional neuromotor physiotherapy by enabling (i) high-dose, task-specific stepping (greater time spent upright and more steps per session), (ii) more physiological joint trajectories via trajectory control with phase-specific assistance (stance and swing) and progressive weaning (assistance-as-needed), (iii) controlled weight-shift and load symmetry with real-time feedback, and (iv) progression of step initiation from therapist-triggered to patient-initiated modes, reinforcing active participation. Given the study design and lack of neurophysiological data, no inferences about neural reorganization can be made.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, participants were male, which limits the generalizability of our neuromuscular and functional findings; these results should be regarded as preliminary and not directly extrapolated to female patients, and future controlled studies will adopt sex-balanced recruitment. Second, the feasibility design precludes statistical inference and limits generalizability beyond older adults with degenerative, iSCI. Third, although inclusion was deliberately narrow, the participants still differed in prior surgery, baseline capacity, and asymmetry, which may have influenced responsiveness. Fourth, the program was multimodal, combining one hour of neuromotor physiotherapy with one hour of exoskeleton training per session, and without a physiotherapy-only comparator, the specific contribution of each component cannot be isolated. Fifth, the intervention lasted four weeks with no follow-up, so the durability of change and transfer to unassisted ambulation remain unknown. Sixth, outcome measurement has constraints: 10-Meter Walk Test performance can be influenced by assistive devices, inertial sensor-derived spatiotemporal metrics and the Gait Quality Index are indirect estimates of gait quality. Moreover, EMG information was available exclusively as vendor-generated summary plots, without access to raw time-series data. The absence of raw EMG signals, physiological normalization procedures, and reliable temporal markers precludes independent verification of signal quality, processing steps, and timing. Consequently, the EMG data are presented solely for qualitative visualization and cannot support quantitative, mechanistic, or phase-specific interpretations. In addition, EMG analyses were further limited because only vendor-generated PDF summaries were archived and maximal voluntary contractions were contraindicated in this population.

Consequently, %MVC normalization and phase-specific quantitative metrics such as RMS amplitudes, peak timing, activation duration, and co-contraction indices could not be computed retrospectively, so EMG findings are descriptive and timing-focused. Finally, the single-center context, device-specific eligibility, and the need for two therapists per session constrain scalability and external validity. Another limitation concerns the marked differences in baseline characteristics between the two participants, particularly in lower-limb motor impairment (LEMS 10 vs. 20). These differences reflect the broad heterogeneity typical of degenerative iSCI, underscoring why individual responses should be interpreted descriptively rather than comparatively

Future studies should test individualized protocols that adjust exoskeleton assistance, training intensity, and adjuncts (e.g., biofeedback, functional electrical stimulation) to specific motor deficits. Dosing should target task-specific, higher-intensity stepping delivered several times per week over multiweek blocks, consistent with trial practice, and meta-analytic subgroup data suggest larger effects when programs extend beyond two months [25,26,27]. Protocols should prospectively capture device logs (step count, time spent upright, assistance levels) to quantify dose and progression. A post-training follow-up window (e.g., 4–12 weeks) should be included to assess retention and transfer. Personalized and adequately dosed interventions may better realize the therapeutic potential of exoskeleton-assisted gait training in iSCI. Importantly, this study cannot support mechanistic interpretations. Observed changes cannot be attributed to enhanced neuromuscular control, phase-specific recruitment, neural reorganization, or device-driven mechanisms. The absence of raw EMG signals further precludes physiological normalization, timing analysis, and verification of processing parameters. For these reasons, EMG findings are presented descriptively and should not be interpreted mechanistically.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the feasibility and adherence of a four-week combined program of conventional neuromotor physiotherapy plus exoskeleton-assisted gait training in two individuals with degenerative, incomplete spinal cord injury. Both participants completed all planned sessions, and any pre- to post-changes observed reflect the multimodal program rather than exoskeleton therapy in isolation. Within this context, patient A showed clinically meaningful gains in gait function, while qualitative EMG plots are presented solely as visual illustrations and cannot be meaningfully related to spatiotemporal parameters, whereas patient B showed limited functional change and persistent neuromuscular asymmetries, highlighting variability in responsiveness. These observations are descriptive signals, not causal effects. Larger, controlled studies with a physiotherapy-only comparator, longer interventions, and follow-up are needed to determine the specific contribution of exoskeleton-assisted gait training and its durability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., B.C. and S.F.; methodology, P.K., B.C.; validation, M.Z., G.L., S.V. and A.G.; formal analysis, M.R., G.L.; investigation, M.R., G.L., S.V.; resources, S.F., S.V.; data curation, M.R., G.L. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C., M.R.; writing—review and editing, B.C., P.K.; visualization, P.K., B.C., A.G. and C.L.-M.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Grant No. GR-2018-12367485).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the CONSORT reporting guidelines, approved by the institutional ethics committee for Clinical Experimentation of the Veneto Region (No. 171A/CESC, 20 April 2021). This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03443700).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Clinical data generated in this study are included within the manuscript. sEMG data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization, International Spinal Cord Society. International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/international-perspectives-on-spinal-cord-injury (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Khorasanizadeh, M.; Yousefifard, M.; Eskian, M.; Lu, Y.; Chalangari, M.; Harrop, J.S.; Jazayeri, S.B.; Seyedpour, S.; Khodaei, B.; Hosseini, M.; et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2019, 30, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guízar-Sahagún, G.; Grijalva, I.; Franco-Bourland, R.E.; Madrazo, I. Aging with spinal cord injury: A narrative review of consequences and challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 90, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, A.; Cherry, S.; Fraser, M. Principles of Rehabilitation: Occupational and Physical Therapy. In Orthopedic Care of Patients with Cerebral Palsy: A Clinical Guide to Evaluation and Management Across the Lifespan; Nowicki, P.D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan, P.G.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.-Y. Neuroregeneration and plasticity: A review of the physiological mechanisms for achieving functional recovery postinjury. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudo, R.J. Recovery after brain injury: Mechanisms and principles. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymoniuk, M.; Chin, J.-H.; Domagalski, Ł.; Biszewski, M.; Jóźwik, K.; Kamieniak, P. Brain stimulation for chronic pain management: A narrative review of analgesic mechanisms and clinical evidence. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbow, D.R.; Gorgey, A.S.; Sutor, T.W.; Bochkezanian, V.; Musselman, K. Invasive and Non-Invasive Approaches of Electrical Stimulation to Improve Physical Functioning after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrman, A.L.; Bowden, M.G.; Nair, P.M. Neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury and training: An emerging paradigm shift in rehabilitation and walking recovery. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 1406–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Lobo-Prat, J.; Font-Llagunes, J.M. Systematic review on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait training in neuromuscular impairments. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longatelli, V.; Pedrocchi, A.; Guanziroli, E.; Molteni, F.; Gandolla, M. Robotic Exoskeleton Gait Training in Stroke: An Electromyography-Based Evaluation. Front. Neurorobot. 2021, 15, 733738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, F.; Gasperini, G.; Cannaviello, G.; Guanziroli, E. Exoskeleton and End-Effector Robots for Upper and Lower Limbs Rehabilitation: Narrative Review. PM R. 2018, 10, S174–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, G.S.; Beck, O.N.; Kang, I.; Young, A.J. The exoskeleton expansion: Improving walking and running economy. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, S.; Mody, S.H.; Woodman, R.C.; Studenski, S.A. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Glenney, S.S. Minimal clinically important difference for change in comfortable gait speed of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, D.R.; Eng, J.J.; Lam, T.; Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) Research Team. Gait speed using powered robotic exoskeletons after spinal cord injury: A systematic review and correlational study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hai, M.; Feng, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, Z.; Duan, W. Exoskeleton-Assisted Rehabilitation and Neuroplasticity in Spinal Cord Injury. World Neurosurg. 2024, 185, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G.; Avola, M.; Di Gregorio, T.; Calabrò, R.S.; Onesta, M.P. Gait Recovery in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review with Metanalysis Involving New Rehabilitative Technologies. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Cortes, M.; Rykman, A.; Thickbroom, G.; Boone, K.; Pascual-Leone, A. Walking improvement in chronic incomplete spinal cord injury with exoskeleton robotic training (WISE): A randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, F.; Yin, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, L. Comparative efficacy of robotic exoskeleton and conventional gait training in patients with spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Weinrauch, W.J.; Manente, N.; Huang, V.; Bryce, T.N.; Spungen, A.M. Exoskeletal-Assisted Walking During Acute Inpatient Rehabilitation Enhances Recovery for Persons with Spinal Cord Injury—A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2024, 41, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swank, C.; Gillespie, J.; Arnold, D.; Wynne, L.; Bennett, M.; Meza, F.; Ochoa, C.; Callender, L.; Sikka, S.; Driver, S. Overground Robotic Exoskeleton Gait Training in People with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury During Inpatient Rehabilitation: A Randomized Control Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, S.J.; Shin, J.C. Robot-Assisted Gait Training in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 48, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilha, J.; Meireles, A.; de Freitas, G.R.; do Espírito Santo, C.C.; Machado-Pereira, N.A.M.M.; Swarowsky, A.; Santos, A.R.S. Overground gait training promotes functional recovery and cortical neuroplasticity in an incomplete spinal cord injury model. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, T.G.; Reisman, D.S.; Ward, I.G.; Scheets, P.L.; Miller, A.; Haddad, D.; Fox, E.J.; Fritz, N.E.; Hawkins, K.; Henderson, C.E.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline to Improve Locomotor Function Following Chronic Stroke, Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury, and Brain Injury. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2020, 44, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.