Abstract

The article presents the results of theoretical and experimental research into the adhesive properties of flax fiber and their impact on the scientific development of composite material production. The research established that combining natural fibers with a polymer material or matrix increases the complexity of the composite forming process and causes problems in the physicochemical processes of matrix–filler interaction. This is explained by the low wettability of flax bast (13.0–14.5 g). It was found that the presence of cutins on oil flax fibers determines their high degree of hydrophobicity. To improve the adhesive properties of the bast, it was chemically treated to remove cellulose companions and cutins, high-molecular-weight compounds. The bast was chemically treated using the oxidative method. After chemical treatment, a fiber enriched with cellulose and freed from waxy substances was obtained. Thus, the cellulose content increased from 47.67–53.33% to 90.01–97.68%, and the waxy substances were almost completely removed. Their content in the bast was 18.13–18.57%, but after chemical treatment, it decreased to 0.01–0.04%. After chemical treatment, the wettability of the fiber increased to the required levels −104.94–122.78 g, indicating that the adhesive properties were significantly improved. The results of studies on physical and mechanical indicators demonstrate the high quality of the obtained composites. In terms of fluidity, all samples were superior to the control sample reinforced with cotton fiber. The theoretical and experimental research enabled the collection of experimental samples of composite materials.

Keywords:

oil flax; bast; adhesion; property; wettability; chemical treatment; fiber; composite materials 1. Introduction

The global trend of expanding oil flax cultivation area can be explained by the fact that it is a primary source of raw material for technical oil production and is characterized by excellent biological and agronomic properties [1].

Scientific research highlights vegetal composites as a promising sustainable alternative to synthetic materials in industrial construction due to their eco-friendly attributes such as renewability, biodegradability, and low environmental impact [2,3]. A critical factor determining their mechanical performance and efficiency, however, is the textile–matrix interface, which is responsible for effective load transfer [4,5].

The depletion of fossil fuels and increasing environmental concerns are driving the advancement of natural fiber composites (NFCs). These materials offer advantageous mechanical properties, including low density, cost-effectiveness, renewability, and favorable thermal insulation, positioning them as superior alternatives to synthetic composites like glass or carbon fiber. Consequently, NFCs are seeing expanded application in industries such as automotive, construction, and defense, where they contribute significantly to reducing greenhouse gas emissions [6].

Recently, significant attention has been paid to the global utilization of oil flax, but this research is primarily focused on seed processing.

Oil flax is a valuable multi-purpose industrial crop. Flax fibers have been obtained since prehistoric times. Flax fibers can be up to 90 cm in length and approximately 12–16 μm in diameter. In the textile industry, they are used to produce bed linen [7,8,9].

Flax natural fibers stand out due to their high specific stiffness, biodegradability, affordability, and broad availability [10,11].

Only a small number of works have addressed the use of flax fiber for the production of technical textiles and biocomposites. In this regard, the use of flax fiber as a filler in the production of composite materials is particularly relevant.

Scientists in many countries are successfully researching the modification of natural fibers to produce polymer composite materials with natural fibers as fillers [12,13,14,15,16,17].

Valued for their sustainability, low density, and biodegradability, natural fiber composites are considered promising alternatives to conventional synthetics in numerous industries [18,19,20,21].

Flax fibers possess favorable tensile properties, rendering them suitable for reinforcement in matrices [22,23].

The mechanical properties of flax fiber-reinforced composites, specifically the flexural strength, are often compromised by the weak interfacial bonding that exists between the naturally hydrophilic flax fibers and the typically hydrophobic polymer matrices [24,25,26,27].

The study’s findings demonstrate that epoxy composites reinforced with flax fibers and modified with bran filler present a viable, eco-friendly material for secondary structural applications where mechanical strength and thermal stability are required [28].

The use of flax nonwoven fabric-reinforced lime composite may be an effective method for strengthening masonry during construction [29].

Incorporating flax or hemp fibers into polyethylene enhances its mechanical and flammability properties. Compared to the pure polymer’s tensile strength of 24.64 MPa, the reinforced composites achieved a tensile strength of 31.26–34.45 MPa (flax) and 31.41–33.36 MPa (hemp). Furthermore, composites with osmotic degummed fibers exhibited a reduction in peak heat release rate of over 34%, indicating significantly improved fire resistance [30].

A comparative analysis of twelve commercial polymers for flax fiber composites identified polypropylene as the most viable matrix, striking a balance between economic and environmental considerations. However, there is a need for the surface modification of flax fibers to improve their adhesion to the polymer matrix [31,32].

Employing a 1:100 catalyst–resin ratio and a cure cycle of 24 h at 25 °C plus 1 h at 90 °C, the vacuum bagging process produced flax-based laminates with robust mechanical properties. These composites proved to be a competitive and eco-friendly substitute for fiberglass, reaching a stress at break of 77.38 MPa, a Young’s modulus of 6.52 GPa, and an ILSS of 15.56 MPa. Their potential for use in humid conditions is supported by a low water absorption rate of just 3.5% [33].

Currently, the mechanism of interaction between natural fibers and polymer matrices has not been sufficiently studied.

Composite materials are defined as materials consisting of two or more phases bonded together by a binding agent characterized by high adhesive strength. Composites are typically produced by combining two or more components that are insoluble or sparingly soluble in each other and possess distinct functional properties [7].

Composite materials offer high resistance to temperature, corrosion, and loads, and function as excellent electrical insulators. Specific fillers can enhance their resistance to aggressive environments. However, their potential is limited by inconsistent fiber characteristics and hydrophilicity, leading to suboptimal mechanical and thermal properties due to poor fiber–matrix adhesion [34,35].

The global composite materials market is growing, driven by demand from the aerospace, automotive, shipbuilding, and wind energy sectors. The main production capacities for composite materials are concentrated in China, Japan, the USA, and Europe [36].

Composite materials are characterized by their weight and volume filler content. Most composites contain between 50 and 80% filler by weight and between 35 and 70% by volume. Materials are classified as low-, medium-, and high-filled. The filler content of composite materials primarily affects consistency, shrinkage, optical properties, and strength. The higher the filler content, the lower the shrinkage and the higher the strength, while the material will also have a greater density [7].

The main natural fillers are plant-based fibers, including cotton, flax, hemp [7,36].

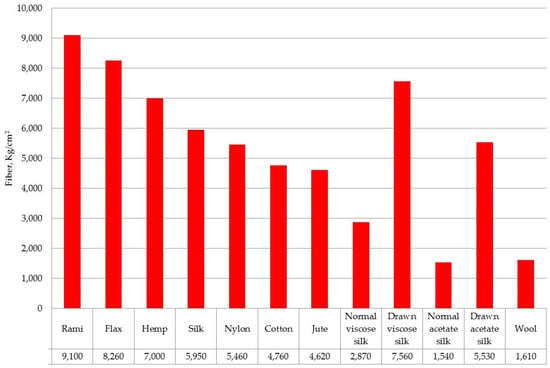

All types of natural fibers are characterized by low density, low moisture, and chemical resistance, and low strength (Figure 1). Textile processing enables the production of a wide range of yarns, fabrics, ribbons, and various layered fillers based on natural fibers.

Figure 1.

Tensile strength of different types of fibers [7].

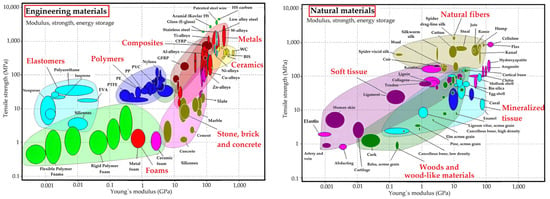

The use of natural materials in production, specifically in the creation of polymer materials, is not inferior to structural materials and even surpasses their characteristics in many aspects. Analysis of Ashby plots (Figure 2) contributes to the preliminary comparison and selection of various material types for subsequent use in biomaterials.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Ashby plots for natural materials and other structural materials (tensile strength and elastic modulus) [8].

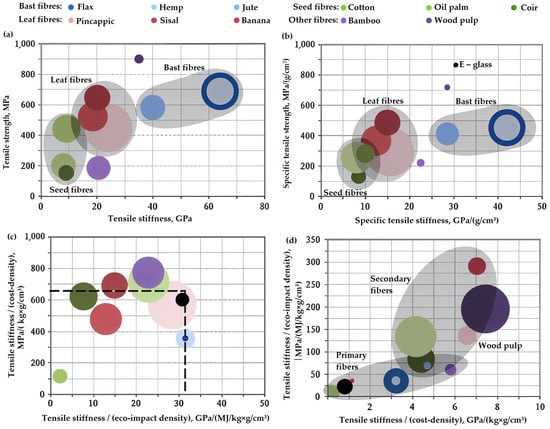

One of the primary indicators of a natural material’s quality is its cellulose content. In fibers with lower cellulose content, cracks propagate through the cells, resulting in an intracellulosic fracture with the pulling out of microfibrils. The maximum elongation of fibers depends on the degree of crystallinity, orientation, and the microfibril angle relative to the fiber axis. The orientation of cellulose microfibrils determines the fiber’s stiffness. Fibers become stiff, inflexible, and possess high tensile strength if the microfibrils are oriented parallel to the fiber axis. Plant fibers are more ductile if the microfibrils are oriented perpendicular to the fiber axis. Figure 3 presents a comparison of absolute tensile properties, tensile properties per unit density, tensile strength properties per unit cost, and tensile properties per unit environmental impact for different categories of plant fibers. Under tension, bast fibers exhibit high strength and hardness, which is particularly relevant for ramie (China grass), flax, and hemp. This occurs due to the high degree of cellulose crystallinity (50–90%) and the small microfibril angles (2–10°) in bast fibers, which provide the structural integrity necessary to support the stem.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Ashby plots for plant fibers: (a) tensile stiffness; (b) specific tensile stiffness; (c) tensile stiffness/(cost-density); (d) tensile stiffness/(eco-impact density) [8].

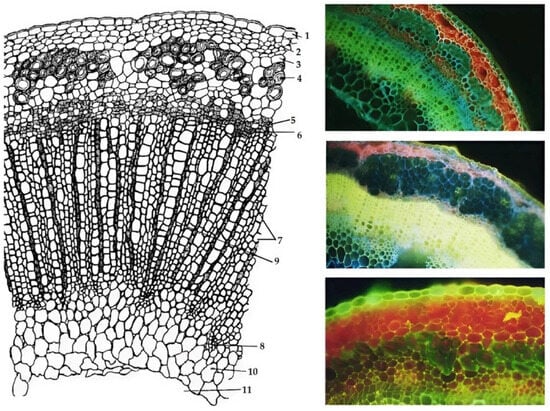

The reason for the lack of adhesion between flax fiber and polymer is the presence of accompanying substances in the composition of flax fiber: lignin, pectins, and waxes. Therefore, the next stage of research aimed to purify cellulose from accompanying substances: lignin, pectins, and waxes. The issue of purifying bast fibers from waxes is quite complex. To determine the influence of waxes on the physico-mechanical properties of bast fibers, it is necessary to consider the anatomical structure of the flax straw stem (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Anatomical structure of the flax stem: 1—epidermis; 2—parenchyma of the primary cortex; 3—starch sheath (endodermis); 4—bast fibers; 5—phloem; 6—cambium; 7—secondary xylem; 8—pith ray; 9—primary xylem; 10—between adjacent pith rays; 11—cavity [37].

Upon full maturity of oil flax straw stalks and after their mechanical processing using a combing process, the bast is completely purified from the woody parts, including phloem, xylem, and parenchyma. Externally, a cuticle remains on the fibers, which imparts hydrophobic properties to them. The cuticle is an integral, structureless, transparent film that extends between the fibers in the form of hairs. The cuticle is composed of substances called cutins. Cutins are high-molecular-weight fatty acids, oxyacids, waxes, and fats. They are resistant to the action of strong chemical reagents, such as concentrated acids and alkalis. Cutins are insoluble in sulfuric acid, chromic acids, and even in a copper-ammonia solution, in which cellulose dissolves.

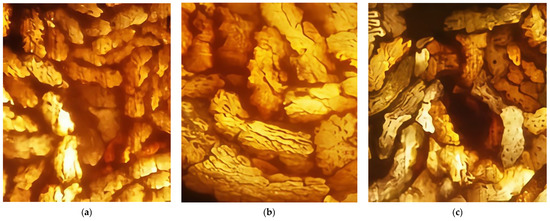

After the mechanical processing of the straw stalks, the cuticle remained on the fiber. This is evidenced by microphotographs of the cross-sections presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Microphotographs of cross-sections of the bast from the studied oil flax varieties: (a) Aisberg (Iceberg); (b) Eureka; (c) Lirina.

Thus, the theoretical and experimental research allowed for establishing that the presence of cutins on oil flax fibers causes a high degree of their hydrophobicity. This is precisely the reason for the very low wettability of the bast −13.0–14.5 g; accordingly, it lacks adhesion to the polymer matrix. Therefore, in subsequent research, the bast was chemically treated to purify the fiber from cellulose companions and cutins—high-molecular-weight fatty acids, oxyacids, waxy substances, and fats.

Therefore, when creating composite materials with natural fillers, it is important to consider the anatomical and morphological structure (Table 1), as well as the chemical and physico-mechanical properties (Table 2) of each part of the stem and fiber. Notably, the variation in the physico-mechanical properties of fibers along the stem length can be quite significant (Table 3). This is related to the soil, climatic, and agrotechnical conditions of plant cultivation. As is known, oil flax seeds are harvested using a grain combine harvester. According to this technology, the stubble remaining after the combine pass is mowed at a height of 5–7 cm from the ground by agricultural machinery equipped with a mower. Thus, the coarse root-based part of the oil flax stems remains in the soil, while the middle part and the top, which contain branched stems of varying diameter, are sent for processing [7,8].

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of some fibrous plants [7,8].

Table 2.

Physico-mechanical properties of natural and synthetic fibers [1,2].

Table 3.

Characteristics of the physico-mechanical properties of composite materials based on flax and glass fiber [38].

Analysis of the data suggests that the use of natural fibers in manufacturing composite materials is fully justified. Major firms, such as Audi, BMW, Opel, Peugeot, Renault, Seat, Volkswagen, Ford, and DaimlerChrysler, successfully utilize these materials in the production of automotive interior trim, various panels, and seats. Various natural fibers can be used for reinforcement in composite materials: flax, hemp, jute, sisal, and coconut. In countries with developed automotive industries, these materials are typically imported. Currently, in modern automobiles, lightweight polymer composites account for 10% of the total vehicle mass, and this share is constantly increasing [38].

Analyzing global experience in using natural fibers for manufacturing composite materials reveals a growing worldwide demand for environmentally friendly, biodegradable, and renewable materials. Therefore, the deep processing of oil flax straw stalks to obtain the bast and, subsequently, fiber with the necessary physico-mechanical properties for producing environmentally friendly organic technical textiles for various functional purposes is highly relevant. The application of natural fibers addresses challenges such as utilizing renewable raw material resources, enabling more complete material utilization, allowing for the cost reduction in goods, and replacing fiberglass in certain manufacturing sectors. Flax fiber, as a natural polymer, is gaining increasing importance in the field of composite materials due to its mechanical properties, low density, and biocompatibility. One of the key parameters for the effective use of flax fiber in composites is its adhesive property to polymer matrices [38,39,40,41,42,43].

The research aimed to investigate the adhesive properties of flax fiber from different varieties and determine their impact on the development of innovative technologies for producing biocomposites. To achieve this aim, the following tasks had to be solved: to analyze the physicochemical characteristics of flax fiber; determine the factors influencing the adhesion of flax fiber to various polymer matrices; investigate the effectiveness of different surface treatment methods for improving adhesion; evaluate the possibility of using flax fiber in manufacturing biocomposites; and determine the potential impact of the research results on the development of innovative technologies.

The scientific novelty of the study lies in establishing the main reasons for the low wettability of the bast and the lack of adhesion to the polymer matrix, which are associated with the peculiarities of the anatomical structure of flax fibers. To remove plaque and incrustations, a new oxidative method of boiling flax bast was employed, which allowed for increasing the adhesion of fibers to thermosetting resins.

2. Materials and Methods

For the experimental research, three oil flax varieties—Eureka, Lirina, and Aisberg (Iceberg), which differ significantly in their technological characteristics, were selected. These varieties were grown in the southern climatic conditions at the State Enterprise “Experimental Farm “Askaniyske”” of the Askania State Agricultural Research Station of the Institute of Irrigated Agriculture of the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine, Kakhovka district, Kherson region (Ukraine) (46°33′25.1″ N 33°48′17.0″ E). Production trials were conducted at the enterprise of SE “Plastmas”, LLC “TD Plastmas-Pryluky” (50°35′27.0″ N 32°21′49.9″ E) and the testing laboratory of LLC “Research Development Control Innovation laboratory” in the city of Pryluky, Chernihiv region (Ukraine) (50°35′26.7″ N 32°21′54.2″ E), where experimental samples of composite materials were manufactured using oil flax fibers as fillers, with cotton fiber used for the control sample.

The agronomic practices for growing oil flax in the experiment were those recommended for the southern zone of Ukraine. The crop was placed in the grain units of the field crop rotation after winter wheat. Primary soil tillage was carried out according to a scheme of combined autumn tillage. Immediately after harvesting the pre-crop, disking was performed to a depth of 8–10 and 10–12 cm. Fertilizers at a rate of N45P30K30 were applied during the primary tillage, which was conducted to a depth of 20–22 cm. Nitroammophoska and ammonium nitrate were used as fertilizers. In autumn, to level the soil surface, continuous cultivation with harrowing was carried out. In spring, upon the soil reaching physical maturity, it was harrowed with heavy tooth harrows, and pre-sowing cultivation was performed. An additional tillage was carried out before sowing. Sowing was conducted using Klen-6 seeders with a 15 cm row spacing. The seeding rate was set at 6 million germinating seeds per hectare. The crops were rolled with ring-spike rollers. In the “Yalynka” phase (early seedling stage), when plant height was up to 10 cm, a tank mixture of the herbicides Agritox 500 (1.0 l/ha) + Loren (8 g/ha) was applied. A self-propelled sprayer, Lazer 3000, was used to apply plant protection products and for desiccation. Harvesting was conducted by direct combining of the experimental plot.

The Eureka variety was developed by the Institute of Irrigated Agriculture of the NAAS (Ukraine) using the hybridization method followed by individual-family selection. The variety’s purpose is to provide oil for food and technical needs, and meal for animal feed. The plant height is 57–62 cm. The stem is round, 3–4 mm thick, with branches in the lower and upper parts. The duration of the vegetative period is 81 days. The inflorescence is umbel-like, 25–32 cm in length. The fruit is a round capsule with 7–10 seeds. The seeds are brown. The weight of 1000 seeds is 7–8 g. It is resistant to lodging, capsule shattering, and seed shedding. The variety is stable in yield. It is moderately resistant to pests and diseases, suitable for cultivation in all zones. Seed yield is 2.88 t/ha. Oil content in the seed is 39.4%.

Chemical treatment was carried out using the developed oxidative method, which employed hydrogen peroxide (100%), sodium hydroxide, soda ash, sodium silicate, sodium tripolyphosphate, and a wetting agent. For this, the crushed flax raw material was boiled in a laboratory cooker using the oxidative method at a temperature of 90 °C for 60 min. After that, it was washed with cold water, acidified with sulfuric acid, rewashed with cold water, squeezed to a humidity of 60% and dried at a temperature of 100 °C.

The Aisberg (Iceberg) variety was developed by the Institute of Oil Crops of the UAAS (Ukraine) using the method of induced mutagenesis by gamma-ray irradiation of seeds from the Tsian cultivar. The plant height ranges from 54 to 57 cm, and the duration of the vegetative period is 86–88 days. The variety is characterized by resistance to drought and lodging. In field experiments at the Institute of Agriculture of the Southern Region of the UAAS since 2004, its seed yield was 2.08–2.18 t/ha.

The Lirina variety was developed by German breeders “Deutsche Saatveredelung AG”. It is an intensive-use variety. It produces high stable yields of 2.5–2.9 t/ha. The vegetative period is 107–128 days. A large number of seed capsules ensures high yields even at low plant density. The plant height is 58–78 cm. The weight of 1000 seeds is 5.6–7.2 g.

The quality of cellulose obtained from oil flax fiber was assessed in accordance with DSTU EN ISO 5270:2023 “Cellulose. Laboratory sheets. Determination of physical properties” [44].

The content of cellulose, lignin, and pectic substances in oil flax fiber was investigated using commonly accepted methodologies. Cellulose content was determined using the TAPPI T203 method “Alpha-, Beta- and Gamma-Cellulose in Pulp”, a widely applied method for determining α-cellulose [45]. The quantity of lignin was determined using the acid hydrolysis method [46]. The amount of pectic substances was determined by quantitative analysis according to ISO 5773:2023 [47].

To determine wettability, 15 g of air-dry cellulose, taken from the average sample, was weighed with an accuracy of no more than 0.1 g. A sample was formed on a table to the size of an aluminum cylinder, which was pre-manufactured according to the drawing. The cellulose was placed into the pre-weighed cylinder and compacted to the internal mark of 50 mm. The samples were compacted by means of vibrational treatment (60 s at 50 Hz), which minimized the variability arising from fiber packing heterogeneity. During the sample formation, any dust that spilled out was collected and placed back into the cylinder with the cellulose. All measurements were performed at a controlled temperature of 20 ± 0.5 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 5%.

Distilled water at a temperature of 20 ± 0.5 °C was poured into a crystallization dish to a level no less than 20 mm from the rim. The aluminum cylinder was then lowered into it until it reached the level of the external lower mark on the cylinder. After 30 s, the aluminum cylinder with the moistened sample mass was removed from the water and weighed with an accuracy of no more than 0.1 g.

Wettability (X), in grams, was calculated using the formula:

where: m is the mass of the air-dry cellulose, g;

X = m1 − (m2 + m),

m1 is the mass of the cylinder with cellulose after testing, g;

m2 is the mass of the empty cylinder, g.

The test result was taken as the arithmetic mean of five parallel tests, rounded to the nearest whole number. The permissible discrepancy between individual tests did not exceed 10% of the mean value.

Composites based on a phenol-formaldehyde matrix with flax fiber were made in the manufacturing conditions at the state enterprise “Plastmas” (Pryluky, Chernihiv region) in accordance with the approved technological regulations.

The prepared mixture of phenol-formaldehyde and preliminarily chemically modified flax fiber was thoroughly mixed until the filler was evenly distributed, and then it was put into a mold. The hot pressing process was based on the following parameters: pressing temperature −150–pressure −5–6 MPa, and pressing duration −25–30 min. After pressing, hardening occurred at a temperature of 100–110 °C for 2 h. After hardening, the samples were cooled under pressure in the mold to room temperature to prevent internal stresses and deformations. The above parameters ensure the optimal degree of the phenol-formaldehyde matrix, proper adhesion to the fiber filler, and stable mechanical characteristics of finished composite materials.

The quality of the obtained phenolic plastics reinforced with flax and cotton fibers was tested in accordance with the requirements of TC U 25.2-32512498-001-2004 “Phenolic pressing mass”. Test conditions: temperature −20 °C, relative humidity −55%. Conditions: temperature −22 °C, relative humidity −55%. Method for manufacturing composite material samples—pressing. When assessing the quality of phenolic plastics reinforced with flax fibers, the following physical and mechanical indicators were determined: color, fluidity, appearance of pressed phenolic samples [48]; Charpy impact strength on samples without a notch [49]; bending stress at failure [50]; volumetric electrical resistivity [51], and electrical strength [52].

The experimental samples were examined using measuring instruments and testing equipment: pendulum copper of the PSW 4 JOULE brand, caliper Shtsots-1-150-0.01; installation for testing plastics for bending and compression type AS-102 (MN-1); ruler; digital thermometer Shch 404-M1; and installation for determining electrical strength [47]. Content of waxy substances was determined by Soxhlet extraction with an organic solvent (ethanol-benzene mixture) followed by gravimetric analysis of the extract, in accordance with TAPPI T 204 cm-97 [53].

The ash content was determined by complete combustion of the organic matter in a muffle furnace at a strictly specified temperature of 525 ± 25 °C, followed by weighing the non-combustible residue [54]; polymer viscosity was measured using a rotational viscometer [55]; the degree of polymerization was calculated via the intrinsic viscosity of the solution [56]; the molecular weight of the polymers was determined by the size-exclusion chromatography method [57].

The test result was taken as the arithmetic mean of five parallel tests for each tested grade, compared to the control sample, where cotton fiber was used as a filler.

Experimental data were organized using Excel 2021 and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA).

3. Results

3.1. Research on the Wettability of Flax Fiber of the Studied Varieties Before Processing

The emergence of cohesion between the filler and the polymer, as well as their interaction is due to a physical phenomenon called adhesion. Polymer adhesion to the filler surface is one of the primary factors determining the physico-mechanical properties of composite materials. The main indicator of adhesion for phenol-formaldehyde resins is wettability. Therefore, this work involved research to determine the wettability of the bast from three studied oil flax varieties—Eureka, Lirina, and Aisberg (Iceberg), which differ significantly in their technological characteristics (Table 4).

Table 4.

Wettability of oil flax bast from different varieties.

Analysis of the data indicated low wettability of the bast from all three studied oil flax varieties. The average values of this indicator ranged from 13.0 to 14.5 g, with the bast of the Lirina variety having the highest wettability and the bast of the Aisberg variety having the lowest wettability. Differences were statistically significant (LSD0.05 0.641 g, p < 0.05). The absolute deviation averaged 0.14–0.36 g, and the relative deviation equaled 2.8–6.3%.

Thus, due to its low wettability, the oil flax bast obtained after the mechanical processing of straw stalks is unsuitable for manufacturing fillers for reinforcing composite materials, despite a high degree of refinement and removal of shives and impurities. To clarify the reason for such low wettability, it is necessary to study the chemical composition of the bast and the anatomical structure of oil flax straw stalks in detail. Table 5 provides a comparative characteristic of the chemical composition of oil flax fiber and other annual plants.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of annual plant fibers.

Analyzing the data (Table 5) shows that in terms of cellulose content, oil flax was inferior to fiber flax, hemp fiber, and cotton. The cellulose content in oil flax fiber ranged from 67.0 to 73.0% (LSD0.05 4.448%, p < 0.05). Cotton had the highest cellulose content, ranging from 92.0 to 98.0% (LSD0.05 4.448%, p < 0.05).

In terms of lignin content, oil flax was most similar to cotton fiber. Unlike other bast crops (fiber flax and hemp), it contained 1.0–2.5% of lignin (LSD0.05 0.643%, p < 0.05). Cotton fiber had the lowest lignin content compared to the aforementioned annual crops. For cotton, this indicator was 0.6–0.7% (LSD0.05 0.643%, p < 0.05).

Hemp fiber contained the least amount of pectin −0.9–1.0% (LSD0.05 0.345%, p < 0.05), while the other studied plants showed almost no difference in this indicator. Thus, the data indicate that oil flax fiber can be successfully used to manufacture cellulose-containing semi-finished products for various target purposes.

A comparative physicochemical characteristic of cellulose obtained from different plants is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Physicochemical quality indicators of different types of cellulose.

Analysis of the data (Table 6) indicates that, in terms of mass fraction of cellulose and other quality indicators, flax was almost on par with cotton and wood. However, despite this, oil flax bast is poorly suited for use in certain branches of industrial production due to its relatively high content of other chemical components.

All known methods for purifying cellulose from accompanying substances and waxes are divided into six groups: acidic, alkaline, neutral, oxidative, stepwise, and combined. A critical analysis of scientific literature indicates that all of the aforementioned methods for obtaining cellulose are labor-intensive, environmentally harmful, and require the expansion or reconstruction of the existing technical production base [58].

This work involved experimental research on the use of oil flax fibers as a cellulose filler for forming composites based on phenol-formaldehyde polymers, as well as the theoretical development of a mechanism for the interaction of oil flax fiber cellulose with the polymer matrix of phenol-formaldehyde resins [6,59,60,61,62,63,64].

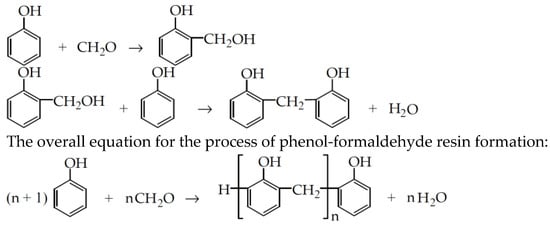

Let us consider the proposed mechanism of interaction between flax cellulose and the polymer matrix. The first stage of the process for obtaining polymer composite materials based on flax fiber cellulose and phenol-formaldehyde resin is the production of the phenol-formaldehyde resin. The mechanism of the chemical polycondensation reaction is shown in Figure 6. The initial products of the condensation of phenol with formaldehyde in an acidic medium are oxybenzyl alcohol and dioxydiphenylmethane, which are unstable under these conditions. Furthermore, analogously, through the sequential addition of formaldehyde and phenol molecules, subsequent polycondensation products are formed.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of the polycondensation chemical reaction [65,66]. Where n is the degree of polycondensation, indicating how many times the elementary unit C6H3(OH)CH2 is repeated in the polymer molecule’s structure (typically n = 4 ÷ 8).

A novolac resin (phenol-formaldehyde) is a mixture of polymer homologs with a wide variation in the molecular weights of individual fractions. Novolac molecules contain active hydrogen atoms in the ortho- and para-positions relative to the phenolic hydroxyl groups. Treating novolacs with formaldehyde in the presence of bases can yield resol oligomers (resols). Novolac oligomers are solid thermoplastic products ranging from light to dark brown in color, soluble in alcohol and acetone, but insoluble in aromatic hydrocarbons [1].

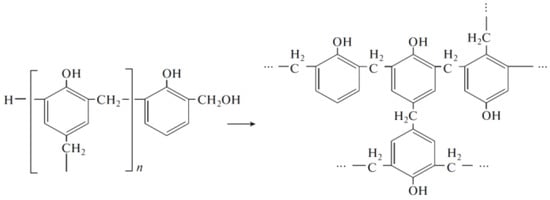

In the second stage, a chemical reaction occurs between flax cellulose and phenol-formaldehyde resin, resulting in the formation of polymer composite materials, as depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Process of forming polymer composite materials.

Previous research established that flax fiber possesses low wettability and is therefore incapable of being pressed into composites. Thus, it was hypothesized that, unlike cotton fiber, which contains almost no impurities and does not require this step, creating adhesion between flax fiber and the polymer matrix during composite formation requires preliminary purification of the flax fiber from accompanying substances. Consequently, in the subsequent work, the fiber was purified from these substances. An oxidative method was used for this purpose.

3.2. Change in the Chemical Composition of Flax Fiber After Chemical Treatment

The content of the main chemical components of unprocessed flax fiber and flax fiber after boiling, as well as the wettability of the flax fiber samples in the studied oilseed flax varieties, were determined using standardized methods [45,46,47,53] (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Chemical composition of oil flax bast from different varieties after mechanical processing (before retting).

Table 8.

Chemical composition of fiber from different varieties of oilseed flax after retting.

Analysis of the data indicates that retting the bast using the specified regime yielded fiber enriched in cellulose and purified it from waxy substances. Thus, the cellulose content increased from 47.67–53.33% to 90.01–97.68% (p < 0.05), and the waxy substances were almost completely removed. Their content in the bast was 18.13–18.57% (p < 0.05), but after chemical treatment, it decreased to 0.01–0.04%.

3.3. Results of Preparation and Testing of Composites Using Modified Flax Fiber

As noted earlier, one of composite material manufacturers’ most critical requirements for cellulose-containing fillers is their high wettability. Therefore, alongside the experimental studies on the chemical composition of the fiber obtained after retting the bast, the wettability indicators of the fiber for the Aisberg, Lirina, and Eureka varieties were determined. The obtained results, along with information on the mass fraction of α-cellulose in the fiber of the three studied oilseed flax varieties, are presented in Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 9.

Physico-chemical quality indicators of oilseed flax fiber (Aisberg variety) obtained after chemical treatment of the bast.

Table 10.

Physico-chemical quality indicators of oilseed flax fiber (Lirina variety) obtained after chemical treatment of the bast.

Table 11.

Physico-chemical quality indicators of oilseed flax fiber (Eureka variety) obtained after chemical treatment of the bast.

Analysis of the data showed that the chemical treatment of the bast allowed us to obtain a fiber that met the wettability requirements for fillers as specified in the normative-technical document TC U 25.2-32512498-001-2004 [48]. During the previous research, it was found that this indicator for oilseed flax bast was only 13.0–14.5 g. However, thanks to the technological operation of its retting, the fiber’s wettability increased to the required levels −104.94–122.78 g.

The obtained results demonstrate a significant increase in wettability after chemical treatment for all varieties. However, the data for the Eureka variety were characterized by higher variability (maximum absolute deviation of 3.08 g, coefficient of variation CV = 1.356%) compared to the Aisberg (CV = 0.258%) and Lirina (CV = 0.432%) varieties. This may indicate a greater sensitivity of the Eureka fiber structure to packing microheterogeneity within the capillary system.

To prepare the composite, the components were mixed in the following proportions: 70–75% of phenol-formaldehyde resin, 25–30% of a modified flax fiber, and 2–3% of a hardener. Following thorough mixing, the composition was shaped in a mold, subjected to hot pressing, and subsequently cooled under pressure to room temperature. The specimens were then machined in accordance with standard requirements for the subsequent determination of physico-mechanical and adhesive properties. Composite materials were made in the manufacturing conditions at the state enterprise “Plastmas” (Pryluky, Chernihiv region). The composite plates were cooled under pressure in the mold to room temperature, and then the samples were mechanically processed in accordance with the requirements of the standards for further research into physico-mechanical and adhesive properties. The recipe and technological parameters for preparing the composite material are protected by a utility model patent [67].

Our research showed that the proposed method enables the effective modification of oil flax fibers, significantly increasing their cellulose content and wettability in phenol-formaldehyde resin. The quality of the resulting composites based on the treated fibers complies with the requirements of technical standards [48]. The conclusions regarding the efficacy of the fibers were confirmed within the scope of this work, specifically for the three studied flax varieties (Eureka, Aisberg, Lirina) and the phenol-formaldehyde matrix. To assert the universality of the method, further studies with other types of polymer systems are required.

Therefore, for further industrial trials, experimental samples of composite materials were manufactured at the testing laboratory of LLC “Research Development Control Innovation laboratory” in Pryluky, Chernihiv region. These samples utilized fibrous bast fillers based on a thermosetting resin to assess their suitability for industrial application. The testing results showed that the composite materials reinforced with oilseed flax fiber met the quality requirements specified in TC U 25.2-32512498-001-2004 [48] for their main quality indicators. The color and appearance of the samples met the requirements of the standard. The results of the studies of the physical and mechanical characteristics of the manufactured composite materials are given in Table 12.

Table 12.

Physical and mechanical characteristics of the composite material.

Analysis of the quality indicators of the obtained composite materials, as presented in Table 12, revealed that when reinforcing phenolic plastics with oil flax using thermosetting resin, all tested samples met the normalized indicators according to TC U 25.2-32512498-001-2004.

All samples met the requirements for appearance—no hollows, cracks, or blisters were found on the surface. The color varied between light brown and dark brown, which is typical for phenoplasts with cellulose fillers. The surface uniformity testifies to proper pressing conditions and good adhesion of phenolic resin to flax fiber. The fluidity values ranged from 110 to 120 mm, which meets the quality standards (40–140 mm). The Iceberg samples (115–120 mm) and the Lirina samples (113–118 mm) exhibited the best results, whereas the Eureka variety had a slightly lower fluidity ranging from 110 to 115 mm. The Charpy impact stress for the samples was 8.2–11.3 kJ/m2, exceeding the minimum standard value of 8.8 kJ/m2. The highest value was recorded in the composition with the Eureka variety −11.3 kJ/m2, which was more than 40% higher than the standard value. The flexural strength was 662–706 kgf/cm2 (the standard, not less than 600 kgf/cm2). The maximum strength of 706 kgf/cm2 was recorded in the composition with the Lirina variety, indicating effective stress transfer in the polymer matrix and a uniform distribution of fibers. The electrical resistivity of all samples considerably exceeded the standard value of 1.0·109 Ohm·cm, ranging from 1.96·109 Ohm·cm (Eureka variety) to 6.9·1013 Ohm·cm (Lirina variety). The dielectric strength was 10.6–12.0 kV/mm, which was almost twice as high as the minimum permissible value of 6.0 kV/mm. This confirmed that the use of natural fibers does not reduce but improves the insulating properties of phenolic materials, provided there is sufficient adhesion between the filler and the matrix. All compositions under study fully met the technical requirements. The sample with the Lirina variety demonstrated the best combination of mechanical strength, electrical resistivity, and dielectric strength, whereas the Eureka variety was characterized by the highest impact stress.

The experimental samples of composite materials reinforced with flax fiber are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Experimental samples of composite materials reinforced with flax fiber.

Experimental samples of oil flax fiber-reinforced composite materials were successfully fabricated using a novel oxidative retting method for removing surface deposits and encrustations from the flax bast. These samples exhibited excellent adhesion to the polymer matrix due to prior chemical treatment and met or exceeded the requirements of the relevant standard in terms of their mechanical and electrical insulation properties.

Based on the research, the main reasons for the low wettability of the bast and the lack of adhesion to the polymer matrix were identified, which are associated with the peculiarities of the anatomical structure of oil flax fibers. A new oxidative method for boiling oil flax bast was developed to remove cutins and incrustations, which allowed increasing the adhesion of fibers to thermosetting resins. As a result of the research, an act of acceptance of completed work was issued, a formulation for a composite material based on thermosetting resins was developed, experimental samples of composite materials were obtained, the main physical and mechanical characteristics of the obtained composite material were determined, and a test protocol for samples of the composite material using oilseed flax fiber based on a thermosetting resin was received. Based on the results of the work, utility model patent No. 152241 was awarded [67].

4. Discussion

Polymer adhesion is one of the primary factors determining the physical and mechanical properties of composite materials. Composite materials are defined as those consisting of two or more phases bonded together by a binder substance characterized by high adhesive strength [1]. Modern trends in scientific development are determined by the utilization of biological products. Consequently, research on modifying natural fibers to produce polymer composite materials with natural fibers as fillers is highly relevant [68,69,70,71]. Using oilseed flax (linseed) is of particular interest [72,73].

A key indicator of adhesion for phenol-formaldehyde resins is wettability. Based on theoretical and experimental studies, the feasibility of manufacturing composite materials reinforced with flax fiber after chemical modification and its subsequent use as a filler in a thermoset resin matrix has been confirmed. An important outcome of the scientific research is that the natural hydrophilicity of flax fibers, as well as the presence of cutins and waxy substances, significantly reduce adhesion to hydrophobic polymers. These conclusions are consistent with literature data, which have identified natural plant impurities as key factors limiting the interaction in the fiber–matrix system of biocomposites [17,29,39,59,63].

Following the chemical treatment, cutins and waxy substances were removed, which resulted in the enrichment of the fiber with cellulose (up to ~97%) and a significant increase in wettability and adhesive properties. The obtained results correlate with other studies where alkaline and oxidative treatments of fibers have contributed to improved adhesion and strength [7,9,74,75]. The experimental samples exhibited high physical and mechanical characteristics, confirming the effectiveness of the applied method and laying a foundation for further optimization.

A comparative analysis of the chemical composition shows that oilseed flax has a lower cellulose content (67.0–73.0%, LSD0.05 4.448%, p < 0.05) compared to long-fiber flax, hemp, and cotton. However, its lignin content (1.0–2.5%, LSD0.05 0.643%, p < 0.05) is closest to that of cotton fiber and, unlike other bast fiber crops (long-fiber flax and hemp), is relatively low. The pectin content is comparable to that of other plants, except for hemp. These data suggest that oilseed flax fiber has potential for polymer production.

Further analysis of the physicochemical characteristics of cellulose revealed that flax cellulose is nearly on par with cotton and wood cellulose in terms of mass fraction and other quality indicators.

The hypothesis that the hydrophobic nature of the bast fiber, imparted by wax-like substances (cutins), is the primary cause of poor wettability and, consequently, poor adhesion to the polymer matrix was confirmed through anatomical study. The cuticle, composed of high-molecular-weight fatty acids, hydroxy acids, waxes, and fats, remains on the fiber after mechanical processing, granting it high hydrophobicity. The resistance of cutins to strong chemical reagents explains the low bast wettability of 13.0–14.5 g (LSD0.05 0.641 g, p < 0.05) and the subsequent lack of adhesion. This understanding necessitated chemical processing to remove cellulose companions and cutins. Although various methods exist (acidic, alkaline, neutral, oxidative, multi-step, combined), they are often labor-intensive, environmentally harmful, and require significant industrial retooling. In this study, an oxidative method was used for purification.

The low adhesion of untreated flax fiber is attributed to its hydrophobicity, which is caused by the presence of cutins. The implemented chemical treatment effectively resolved this issue, drastically increasing the cellulose content and wettability, which allowed for the successful development of composite materials that meet industrial standards and are promising for various applications. An important contribution of this work is the confirmation of the potential of using flax fiber as an environmentally friendly reinforcing material. Unlike synthetic fibers, flax is biodegradable and has a lesser negative environmental impact, while providing high-strength characteristics [63]. Potential application areas for the obtained research results, notably in 3D printing, the automotive and aviation industries, as well as in biomedical products, underscore the relevance of these findings. Similar to other studies that have demonstrated the possibility of producing flax-based biocomposites with properties approaching those of fiberglass, our results indicate significant potential for developing “green” materials [76,77,78].

When reinforcing phenolic plastics with oil flax using thermosetting resin, all tested samples met the normalized indicators according. In terms of fluidity, all samples were superior to the control sample reinforced with cotton fiber. The bending stress at failure was 706 MPa (p < 0.05) for the Lirina variety, exceeding that of the control sample. The research confirmed other scientists’ findings that the type of fiber filler and the degree of its dispersion affect the mobility of melts, but do not worsen the material’s technological properties [28,29,30,31,32,33].

The experimental results demonstrated that flax fiber can be a quality reinforcing component of phenolic compositions, similar to cotton fiber, thereby enhancing their high mechanical strength and brittle fracture resistance and improving the insulating properties of phenolic materials, provided there is sufficient adhesion between the filler and the matrix. The data obtained confirm the feasibility of using flax fibers as environmentally friendly and technologically effective fillers to obtain composite materials that provide a combination of high mechanical and electrical insulating properties.

The research results demonstrate the promise of using modified flax fiber as a reinforcing component in creating high-performance and environmentally safe composite materials. The enhanced adhesion in the fiber–matrix system opens up new opportunities for developing functional composites with additional properties such as thermal insulation, antibacterial effects, and others. This contributes significantly to the development of a “green” economy and stimulates the advancement of the scientific foundations for innovative technologies that aim to reduce harmful environmental impacts.

5. Conclusions

This study established a direct causal link between the natural cutin layer on oilseed flax fibers and their high hydrophobicity (wettability of 13.0–14.5 g), which limits adhesion to polymers. The core achievement was the development of a unique oxidative chemical treatment that fundamentally transforms the fiber’s properties. This process efficiently removes waxy substances (reducing them from 18.13–18.57% to 0.01–0.04%) and enriches cellulose content to 90.01–97.68%.

The composite material based on the Lirina variety flax fiber not only fully complies with regulatory requirements but also surpasses counterparts utilizing other cellulose fillers in its key performance properties, namely bending stress at failure (706 kgf/cm2), volume electrical resistivity (6.9 × 1013 Ohm·cm), and electrical strength (12.0 kV/mm), making it the most promising variety for industrial application.

As a direct result, the fiber’s wettability dramatically increased to 104.94–122.78 g, enabling strong adhesion to a thermosetting resin. The resulting flax–fiber composites demonstrated superior mechanical performance, achieving a flexural strength of up to 706 MPa and outperforming control samples reinforced with cotton fiber.

The research outlined clear and logical directions for future scientific work aimed at deepening the understanding and improvement of natural fiber-based composite materials. A promising direction is the expansion of the range of the investigated natural fibers, such as hemp, coir, or jute, as fillers for hybrid composites. These fibers, which have significant potential due to their strength and environmental friendliness, can provide improved operational characteristics of the materials. An important practical aspect is the study of the rheology of composite materials, which is necessary for optimizing their processing technologies, particularly injection molding or 3D printing. Simultaneously, it is necessary to focus on the development of more environmentally friendly and energy-efficient methods for fiber preparation and cleaning that minimize the use of aggressive chemicals. A priority task is to conduct comprehensive tests for long-term wear resistance and aging under various environmental conditions. These research directions will not only expand the areas of applying natural fiber composites but also significantly enhance their competitiveness with traditional materials, thereby contributing to the development of sustainable and innovative materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.G. and S.L.; methodology, O.G. and S.L.; validation, O.G. and S.L.; formal analysis, O.G. and S.L.; investigation, O.G.; resources, S.L. and N.L.; data curation, O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, O.G., S.L. and N.L.; visualization, O.G., S.L. and N.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. and N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gorach, O.; Dzyundzya, O.; Rezvykh, N. Innovative Technology for the production of gluten-free food products of a new generation. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 20, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Alliyankal Vijayakumar, A.; Jose, T.; George, S.C. A comprehensive review of sustainability in natural-fiber-reinforced polymers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheed, N.K. Advantages of natural fiber composites for biomedical applications: A review of recent advances. Inst. Ion. 2024, 7, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, M.; Kumar, C.A.; Sollapur, S.B.; Bhosale, S.Y.; Kawade, M.M.; Dakhole, M.Y.; Kumar, P. Study on Fabrication and Mechanical Performance of Flax Fibre-Reinforced Aluminium 6082 Laminates. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. D 2024, 105, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agossou, O.G.; Homoro, O.; Amziane, S. Optimising the textile-matrix interface for enhanced mechanical performance in vegetal FRCM composites. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114, 114334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, N.E.; Rusnakova, S.; Ajayi, A.E.; Ogunleye, R.O.; Agu, S.O.; Amenaghawon, A.N. A comprehensive review of natural fiber reinforced Polymer composites as emerging materials for sustainable applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 43, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchuk, P.P.; Kashytsky, V.P.; Melnychuk, M.D.; Sadova, O.L. Composite and Powder Materials: A Textbook; Savchuk, P.P., Ed.; FOP Telitsyn O.V.: Lutsk, Ukraine, 2017; 368p. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, A.; Edwards, K.L.; Bahraminasab, M. Screening of materials. In Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for Supporting the Selection of Engineering Materials in Product Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jarošová, M.; Lorenc, F.; Bedrníček, J.; Petrášková, E.; Bjelková, M.; Bártová, V.; Jarošová, E.; Zdráhal, Z.; Kyselka, J.; Smetana, P.; et al. Comparison of yield characteristics, chemical composition, lignans content and antioxidant potential of experimentally grown six linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) cultivars. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2024, 79, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phunpeng, V.; Boransan, W.; Horpibulsuk, S. Comprehensive analysis of in-plane tensile characteristics of hybrid composite using finite element method. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 1294–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronis, G.; Silva, A.; Ong, M. Comparison of structural performance and environmental impact of epoxy composites modified by glass and flax fabrics. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissar, M.; Chethan, K.N.; Birjerane, Y.A.; Patil, S.; Shetty, S.; Das, A. Coconut Coir Fiber Composites for Sustainable Architecture: A Comprehensive Review of Properties, Processing, and Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoxing, W.; Pierre-Antoine, A.; Guillaume, M. The Effect of Printing Temperature on the Fused Granular Fabrication Property of Flax/PP Agro-Composites at Microscale. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 13989–14000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhsh Mahpour, A.; Claramunt, J.; Ardanuy Raso, M.; Ramon Rosell, J. Fabric-Reinforced Lime Composite as a Strengthening System for Masonry Materials: A Study of Adhesion Using Flexural and Tensile Testing. Rilem Bookser. 2024, 48, 482–492. [Google Scholar]

- Malashin, I.; Martysyuk, D.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A. Data-Driven Optimization of Discontinuous and Continuous Fiber Composite Processes Using Machine Learning: A Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Tian, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X. Thermal conductivity analysis of natural fiber-derived porous thermal insulation materials. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 220, 124941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiyoon, P.; Chongku, Y. Material Properties of Eco-friendly Composite Using Gelatin as an Organic Binder according to the Mix Proposition. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2023, 39, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kir, M.; Boudiaf, M.; Belaadi, A.; Boumaaza, M.; Bourchak, M.; Ghernaout, D. Extracting and characterizing of a new vegetable lignocellulosic fiber producedfrom C. humilis palm trunk for renewable and sustainable applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diharjo, K.; Andoko, A.; Soedarsono, J.W.; Gapsari, F.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Enhanced Composite Performance: Evaluating Silane Treatment on Cordia dichotoma Fibers. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapsari, F.; Andrianto, S.N.K.; Harmayanti, A.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Kartikowati, C.W.; Madurani, K.A.; Wijayanti, W.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Enhancing mechanicaland thermal properties of bio-composites: Synergistic integration of ZnO nanofillersand nanocrystalline cellulose into durian seed starch matrix. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 290, 138571, Erratum in Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: An eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwash, B.; Shivakumar, N.D.; Sachidananda, K.B. A brief review on natural fiber reinforced composite sandwich structures. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, V.S.; Reddy, D.M.; Reddy Mutra, R.; Sanjeev, A.; Dhilipkumar, T.; Naveen, J. Thermal degradation and fire-retardant behaviour of natural fibre reinforced polymeric composites: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 4053–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizu-Montes, A.; Alcivar-Bastidas, S.; Martínez-Echevarría, M.J. Experimental study on the effect of abaca fibers on reinforced concrete: Evaluation of workability, mechanical, and durability-related properties. Fibers 2025, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovuru, R.; Schuster, J. Enhancing mechanical properties of hemp and sisal fiber-reinforced composites through alkali and fungal treatments for sustainable applications. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shettigar, S.; Gowrishankar, M.C.; Shettar, M. Review on aging behavior and durability enhancement of bamboo fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Molecules 2025, 30, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, Z.; Wei, Z.; Ji, C.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, T.; Li, Y.; Fan, J. Improving the interfacial adhesion and mechanical properties of flax fiber reinforced composite through fiber modification and layered structure. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, T.; Yuvarajan, D.; Sundaram, V.; Lakshmi, S.V.; Veeraragavan, V.P. Impact of Bran Filler Amount on Flax Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composite-Mechanical and Thermal Properties for Secondary Structural Applications. SSRG Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 11, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mahpour, A.R.; Claramunt, J.; Ardanuy, M.; Rosell, J.R. Flax Fabric-Reinforcement Lime Composite as a Strengthening System for Masonry Materials: Study of Adhesion. Rilem Bookser. 2023, 43, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Różańska, W.; Rojewski, S. Composites with Flax and Hemp Fibers Obtained Using Osmotic Degumming, Water-Retting, and Dew-Retting Processes. Materials 2025, 18, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, W.; Romanowska, B.; Rojewski, S. The Quantity and Quality of Flax and Hemp Fibers Obtained Using the Osmotic, Water-, and Dew-Retting Processes. Materials 2023, 16, 7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwahar, P.; Prakalathan, K.; Bhuvana, K.P.; Senthilkumar, K. Examining the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of a Novel Hybrid Thermoplastic Rubber Composite Made with Polypropylene, Polybutadiene, S-Glass Fibre, and Flax Fibre. Polymers 2024, 16, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Pont, B.; Aliotta, L.; Tognarelli, E.; Gigante, V.; Lazzeri, A. Toughened Vinyl Ester Resin Reinforced with Natural Flax Fabrics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoui, S.; Belaadi, A.; Chai, B.X.; Abdullah, M.M.S.; Al-Khawlani, A.; Ghernaout, D. Extracting and characterizing novel cellulose fibers from Chamaerops humilisrachis for textiles’ sustainable and cleaner production as reinforcement forpotential applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 134029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheribi, H.; Teyar, S.; Boumaaza, M.; Belaadi, A.; Chai, B.X.; Abdullah, M.M.S.; Gelgelu, A.A.; Klimkina, I. Statistical study of the mechanical behavior of the new Fiber from the Strelitzia Juncea plant fibers: Application in ecological yarns. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2396905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.; Grunden, A.; Dunn, R.R. A review of clothing microbiology: The history of clothing and the role of microbes in textiles. Biol. Lett. 2021, 17, 20200700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datsenko, V.V. Vegetative Organs of Plants. Shoot. Stem. Vseosvita.ua. Available online: https://vseosvita.ua/library/embed/01008vod-1879.docx.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Gorach, O.; Dombrovska, O.; Tikhosova, A. Scientific development of innovative technologies of obtaining composite materials from of oilseed flax fibers. Vlák. Text. 2021, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Indraratna, B. Natural fibre for geotechnical applications: Concepts, achievements and challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusudha, V.; Sunitha, V.; Mathew, S. Performance of coir geotextile reinforced subgrade for low volume roads. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2020, 14, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabay, G.; Sarıçoban, K. Research on Competitiveness in Technical Textiles: Comparison of Countries Having the Lion’s Share of Technical Textile World Exports and Türkiye. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2021, 29, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabaan Shahata Hassan, N.; Ahmed Sadek, M.; Said Shamandy, E. The use of glass technology and technical textiles in the production of printed textile hangings to increase the awareness of the aesthetic side in medical institutions. J. Archit. Arts 2019, 19, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennato, F.; Ianni, A.; Innosa, D.; Grotta, L.; D’Onofrio, A.; Martino, G. Chemical-nutritional characteristics and aromatic profile of milk and related dairy products obtained from goats fed with extruded linseed. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSTU EN ISO 5270:2023; Cellulose. Laboratory Sheets. Determination of Physical Properties (EN ISO 5270:2022, IDT; ISO 5270:2022, IDT). State Enterprise “Ukrainian Research and Training Center for Standardization, Certification and Quality Problems”: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023; 48p.

- TAPPI T 203 cm-22; Alpha-, Beta- and Gamma-Cellulose In Pulp. Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022; 12p.

- ISO 21436:2020; Pulps: Determination of Lignin Content—Acid Hydrolysis Method. International Standard Published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; 12p.

- ISO 5773:2023; Textiles—Determination of Components in Flax Fibres. Standard Published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 12p.

- Technical Conditions U 25.2-32512498-001-2004 with Amendments 1, 2, 3, 4; Phenolic Pressing Mass. Prylutskyizavod: Chernihiv, Ukraine, 2004; 10p.

- ISO 179-1:2023; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties—Part 1: Non-Instrumented Impact Test. International Standard published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 48p.

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. International Standard Published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; 48p.

- IEC 62631-3-1:2023; Dielectric and Resistive Properties of Solid Insulating Materials—Part 3-1: Determination of Resistive Properties (DC Methods)—Volume Resistance and Volume Resistivity—General Method. International Standard published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 28p.

- IEC 60243-1:2013; Electric Strength of Insulating Materials—Test Methods—Part 1: Tests at Power Frequencies. International Standard Published: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; 53p.

- Tappi T 204 cm-97. Solvent extractives of wood and pulp T 204 cm-97. In TAPPI TEST METHODS Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry; Tappi Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–12.

- Tappi T 211 om-02. Ash in wood, pulp, paper and paperboard: Combustion at 525 °C. In Tappi Test Methods Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry; Tappi Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–5.

- ISO 3219-2:2021; Rheology—Part 2: General Principles of Rotational and Oscillatory Rheometry. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; 45p.

- ISO 5351:2010; Pulps—Determination of Limiting Viscosity Number in Cupri-Ethylenediamine (CED) Solution. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; 19p.

- ISO 16014-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Average Molecular Weight and Molecular Weight Distribution of Polymers Using Size-Exclusion Chromatography. Part 1: General Principles. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; 17p.

- Ahrari, M.; Karahan, M.; Karahan, N. Competitiveness Factors in Textiles and Composites Industry and Transformation into Value-Added Products. Recent J. 2023, 24, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, M.; Ahrari, M.; Karahan, N. Composite Materials Market Research and Export Potential Analysis: A Regio-Global Case Study. Recent J. 2023, 24, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, A.; Azam, F.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, T.; Nawab, Y.; Shaker, K. An investigation of Static and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Eco-Friendly Textile PLA Composites Reinforced by Flax Woven Fabrics. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 2024, 821777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Ullah, T.; Nawab, Y. 3D Natural Fiber Reinforced Composites. In Natural Fibers to Composites; Nawab, Y., Saouab, A., Imad, A., Shaker, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nitish, K.; Ramesh, K.K.; Surender, S. Effective utilization of natural fibres (coir and jute) for sustainable low-volume rural road construction—A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128606. [Google Scholar]

- Horach, O.O.; Lavrenko, N.M. Development of scientific foundations for obtaining bast fiber fillers for the production of technical textiles. In Scientific Monograph «Modern Agronomy Trends: Innovation, Sustainable Development and the Future of Agriculture»; Baltija Publishing: Riga, Latvia, 2025; pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Danish, M.; Ahmad, T.; Ayoub, M.; Geremew, B.; Adeloju, S. Conversion of flaxseed oil into biodiesel using KOH catalyst: Optimization and characterization dataset. Data Brief 2020, 29, 105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdnikova, P.V.; Zhizhina, E.G.; Pai, Z.P. Phenol-Formaldehyde Resins: Properties, Fields of Application, and Methods of Synthesis. Catal. Ind. 2021, 13, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnytskyi, A.G.; Snizhko, L.O. Methodical Instructions for Laboratory Work “Production of Phenol-formaldehyde Resin” in the Discipline “General Chemical Technology”; UDCTU: Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, 2004; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Gorach, O.O.; Tikhosova, G.A.; Tikhosov, A.S.; Mykhaylyuchenko, I.V.; Bychkov, M.L. Method for Producing Composite Materials Using Modified Oil Flax Fiber. Utility model patent No. 152241. Application number No. U 2021 06630. Filed 11/23/2021; Publ. 11/01/2023, Bull. 2. Available online: https://sis.nipo.gov.ua/uk/search/detail/1718211/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mohammed, A.; Rao, D.N. Micromechanics and experimental analysis of randomly oriented flax fiber reinforced with recycled EPS waste composites. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivia, H.M.; Hawraa, R.; Yasmine, A.; Abbas, S.M. A multi-scale case study on the variation of flax fiber properties: From single fiber and yarn to woven fabric and bio-based HDPE composites. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107457. [Google Scholar]

- Prapavesis, A.; Fuentes, C.A.; Sarlin, E.; Kallio, P.; Seveno, D.; van Vuure, A.W. Interfacial compatibility and cyclic moisture durability of Flax/Polyamide 6 composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 200, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrenko, S.; Ladychuk, D.; Lavrenko, N.; Ladychuk, V. Strategic Ways of Post-War Restoration of Irrigated Agriculture in the Southern Steppe of Ukraine (Chapter 14). In Sustainable Soil and Water Management Practices for Agricultural Security; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 377–404. [Google Scholar]

- Daget, T.M.; Kassie, B.B.; Tassew, D.F. Extraction and characterization of natural cellulosic stem fiber from Melekuya (Plumbago zeylanicum L.) plant for sustainable reinforcement in polymer composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 141061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudik, O.; Mrynskyi, I. Influence of sowing terms and seeding rate on productivity of oil-bearing flax. Sci. Horiz. 2018, 7–8, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Tao, Y.; Gan, W.; Wang, S.; Nong, G. Preparation of an amphoteric adsorbent from cellulose for wastewater treatment. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 169, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, M.; Nazemi, Z.; Salehi, A.O.M.; Seyfoori, A.; John, J.V.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Akbari, M. Cellulose-based composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and localized drug delivery. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 20, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, W.M.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Franco, M.A.R.; Osório, J.H. Angle-Resolved Hollow-Core Fiber-Based Curvature Sensing Approach. Fibers 2021, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chouw, N.; Jayaraman, K. Flax fibre and its composites—A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzawi, S.; Mahmood, W.A.; Shihab, S.K. Comparative study of natural fiber-Reinforced composites for sustainable thermal insulation in construction. Int. J. Thermofluids 2024, 24, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).