Abstract

Protected agriculture increasingly requires solutions that reduce energy consumption and environmental impacts while maintaining stable microclimatic conditions. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Deep Learning (DL) with solar technologies has emerged as a pathway toward autonomous and energy-efficient greenhouses and solar dryers. This study analyzes the scientific and technological evolution of this convergence using a mixed review approach bibliometric and systematic, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. From Scopus records (2012–2025), 115 documents were screened and 79 met the inclusion criteria. Bibliometric results reveal accelerated growth since 2019, led by Engineering, Computer Science, and Energy, with China, India, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom as dominant contributors. Thematic analysis identifies four major research fronts: (i) thermal modeling and energy efficiency, (ii) predictive control and microclimate automation, (iii) integration of photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems and phase change materials (PCMs), and (iv) sustainability and agrivoltaics. Systematic evidence shows that AI, ML, and DL based models improve solar forecasting, microclimate regulation, and energy optimization; model predictive control (MPC), deep reinforcement learning (DRL), and energy management systems (EMS) enhance operational efficiency; and PV/T–PCM hybrids strengthen heat recovery and storage. Remaining gaps include long-term validation, metric standardization, and cross-context comparability. Overall, the field is advancing toward near-zero-energy greenhouses powered by Internet of Things (IoT), AI, and solar energy, enabling resilient, efficient, and decarbonized agro-energy systems.

1. Introduction

The accelerated growth of the global population, driven by technological progress, has intensified pressure on natural resources and poses significant challenges to the sustainable provision of food, water, and energy [1,2]. Greenhouses, which play a strategic role in food security, are also intensive consumers of resources and relevant emitters of greenhouse gases (GHG) [3], and their long-term viability depends on economic, technological, and policy factors [4]. The expansion of protected cultivation, stimulated by urbanization and the growing demand for high-quality food, highlights the need for more sustainable agricultural systems. However, the energy consumption of different greenhouse models remains a major challenge [5], revealing persistent gaps in the understanding of how structural design and automation influence efficiency and sustainability [6]. The continued dependence on fossil fuels further increases energy consumption and exacerbates sustainability concerns [7].

In this context, solar energy in its photovoltaic (PV) and solar thermal (ST) forms emerges as one of the most promising renewable sources to achieve energy autonomy in agricultural greenhouses and dryers. The integration of hybrid solar systems with thermal energy storage (TES) technologies has proven effective in reducing dependence on the electrical grid and improving energy stability under variable climatic conditions [8]. Recent studies highlight the relevance of thermal storage, particularly sensible, latent, and thermochemical storage, to buffer diurnal temperature fluctuations and maintain operational stability in solar-assisted systems. Phase change materials (PCMs) provide high energy density and contribute to microclimate stabilization. Evidence shows that PCMs enhanced with nanomaterials can increase thermal conductivity and accelerate charging/discharging processes, while nanofluids used as heat-transfer media improve thermal efficiency and storage capacity in hybrid solar systems [9,10].

In parallel, agrivoltaics approaches have demonstrated that installing photovoltaic modules over agricultural soils or greenhouse structures can successfully combine electricity generation with crop production. Early studies showed that pairing shade-tolerant crops with PV generation can increase the economic value of the system by up to 30% relative to conventional agriculture, without compromising crop yields [11]. More recent experiments have also demonstrated that partial PV shading reduces leaf temperature, decreases evapotranspiration, and improves water-use efficiency, thereby strengthening the microclimatic advantages of agrivoltaics in arid and semi-arid regions [12]. Additional empirical evidence shows that agrivoltaic systems enhance water conservation, thermal buffering, and climate resilience, with reductions of 20–40% in water consumption and measurable increases in biomass under moderate PV shading [12,13]. Recent reviews also indicate that agrivoltaics can mitigate heatwaves and frost events, reducing interannual yield variability and positioning this technology as a key strategy for future food security [14].

Against this background, the convergence of solar energy, the Internet of Things (IoT), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are redefining the concept of intelligent greenhouses. IoT-based monitoring systems allow real-time acquisition of temperature, humidity, radiation, CO2 concentration, PV generation, and electricity consumption, while machine learning models optimize ventilation, shading, irrigation, and thermal storage [15,16]. Recent studies have shown that integrating wireless sensor networks with intelligent control can reduce energy demand and improve water-use efficiency, even in PV-powered greenhouses [17,18]. Deep-learning algorithms applied to solar-agricultural systems have demonstrated high performance in PV energy prediction [19], fault detection, MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) optimization, and microclimate control, supporting the development of autonomous, resilient, and low-carbon protected agriculture [20,21].

However, despite the growing number of studies on AI applied to solar energy, a comprehensive understanding of the field remains fragmented. Most research addresses isolated components such as climate control, energy efficiency, photovoltaic modeling, or autonomous decision making without articulating a unified conceptual and technological framework. Therefore, a combined bibliometric and systematic review is essential to identify global trends, knowledge gaps, and emerging research directions linking AI, solar energy, and protected agriculture [22]. While bibliometrics quantifies the dynamics of knowledge production, collaboration networks, and thematic structures, the systematic review deepens the analysis by synthesizing methodological and technical advances that reveal how AI, ML, and IoT are reshaping agricultural energy systems toward more efficient, autonomous, and sustainable configurations.

The purpose of this study is to analyze the conceptual and technological evolution of AI applied to solar systems in protected agriculture, and to understand how these tools enhance energy efficiency, automation, and sustainability in controlled agricultural environments. Within this framework, four research questions (RQs) guide the review:

- RQ1:

- How has scientific production and collaboration on AI and solar energy in controlled agriculture evolved during 2012–2025, and what bibliometric patterns explain its consolidation?

- RQ2:

- Which technologies and algorithms, such as photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems, IoT-based sensing, and machine learning (ML), have demonstrated the greatest maturity and impact on the energy and climate management of greenhouses and solar dryers?

- RQ3:

- What technical, methodological, and sustainability limitations identified in the literature constrain the adoption of these systems in real production contexts?

- RQ4:

- What future research and development directions emerge from the convergence between AI, renewable energy, and agricultural sustainability toward autonomous, resilient, and low-carbon systems?

These questions reflect an analytical and forward-looking perspective aimed at interpreting the current state of knowledge, identifying critical gaps, and projecting the technological opportunities that will define next-generation intelligent solar agriculture. To address them, this work adopts an integrative approach that combines bibliometric analysis with a systematic review, linking the quantitative evolution of scientific production with the conceptual and technical interpretation of advances in the field. Through the examination of co-authorship networks, keyword co-occurrence, and bibliographic coupling, the main intellectual, thematic, and technological cores shaping global research on AI and solar energy in protected agriculture are identified. In parallel, the synthesis of representative studies highlights key developments such as AI-assisted thermal modeling, predictive microclimate control, energy optimization in PV/T systems, and intelligent maintenance strategies within a sustainability framework. Beyond describing current trends, this review aims to project a strategic vision of the field, demonstrating how the integration of AI and solar energy constitutes a cornerstone for the design of intelligent greenhouses, rural energy transition, and climate adaptation in future agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

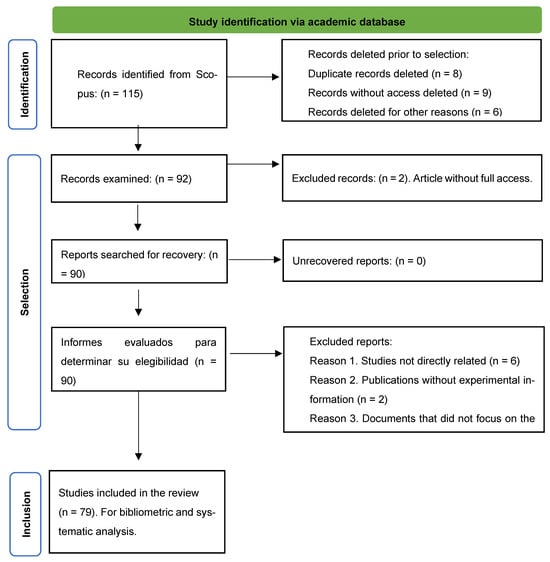

2.1. Methodological Design

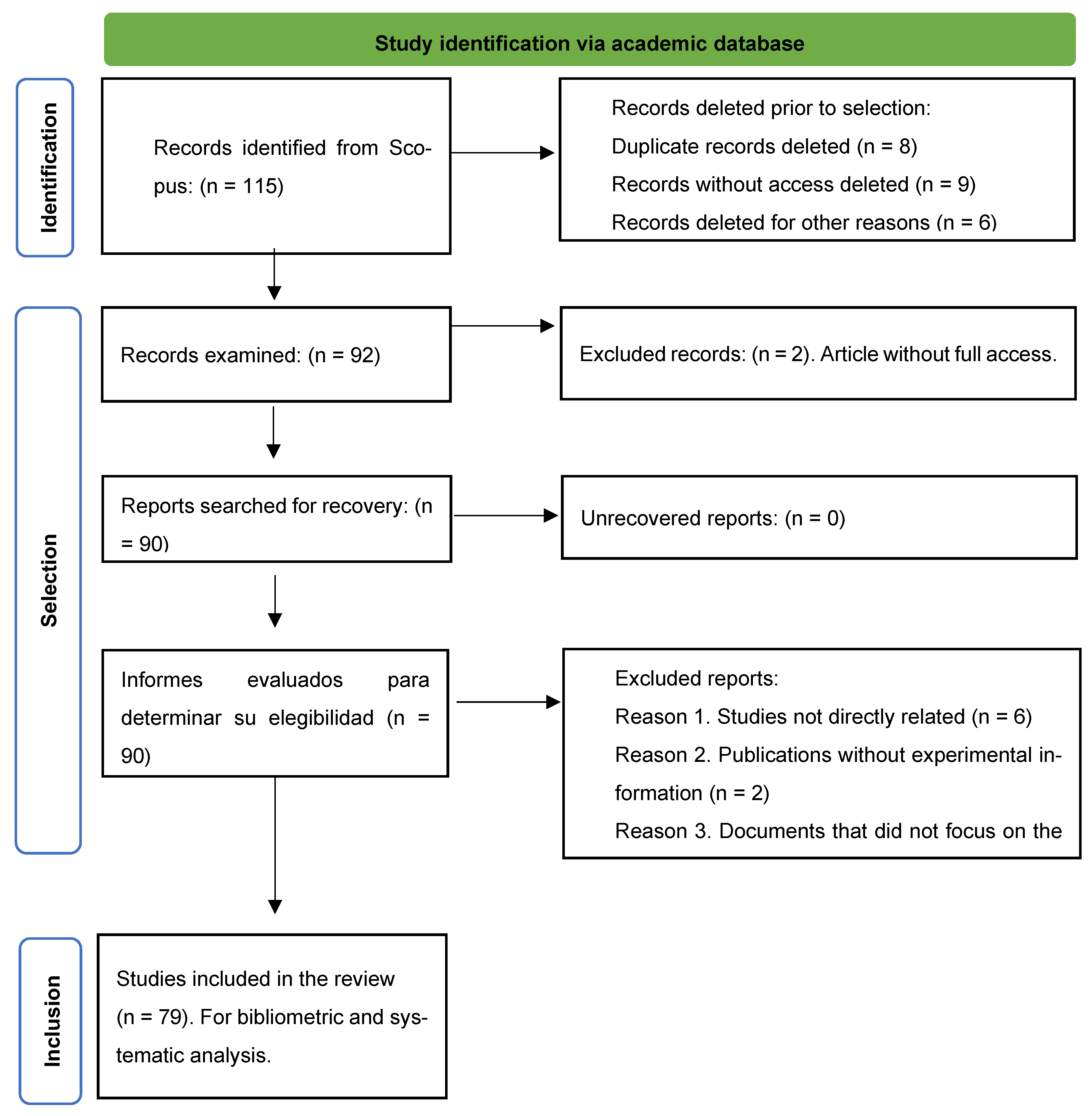

This research combined bibliometric and systematic approaches, following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) to ensure transparency and reproducibility [23,24]. The objective was to integrate the quantitative analysis of scientific production with the qualitative interpretation of technological advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and solar energy applied to protected agriculture. The process comprised four stages: (i) identification of documents, (ii) screening according to predefined criteria, (iii) information extraction, and (iv) joint analysis of trends, networks, and content (Figure 1). In addition, a checklist following the updated PRISMA 2020 guidelines is included in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review.

2.2. Sources and Search Equation

The search was conducted in Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), selected for its interdisciplinary coverage and reliability in peer-reviewed literature. Articles, reviews, conference papers, and book chapters published between 2012 and 2025, with 2025 representing partial year-to-date records obtained at the time of data extraction, in English or Spanish, were considered. The final search equation combined controlled descriptors and free terms related to Artificial Intelligence (AI), solar energy, and protected agriculture:

((“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network”) AND (“solar energy” OR photovoltaic OR “solar thermal” OR “hybrid solar”) AND (“energy efficiency” OR optimization OR “energy management” OR “intelligent control” OR “predictive maintenance”) AND (greenhouse OR “protected agriculture” OR “controlled environment” OR “solar dryer”) AND NOT (“greenhouse gas*” OR “greenhouse effect”)).

The results were exported in CSV and RIS formats for management and processing in Excel and Mendeley. The exclusion clause NOT (“greenhouse gas*” OR “greenhouse effect”) was introduced to filter out studies in which the term “greenhouse” refers to atmospheric greenhouse gases or the planetary greenhouse effect, rather than to protected-crop structures or solar dryers. This prevented the retrieval of many macro-scale climate or energy-policy studies outside the scope of controlled agricultural environments. To ensure that this filter did not bias the dataset against relevant engineering works on emission mitigation, we re-ran the query without this exclusion and manually screened the additional records. The newly retrieved documents mainly addressed economy-wide or power-system-level emission scenarios and did not meet the predefined inclusion criteria; consequently, the final corpus of 79 articles remained unchanged.

2.3. Selection and Eligibility Criteria

The selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and traceability at each stage. A total of 115 records were identified in the Scopus database, from which duplicates (n = 8), documents without full-text access or with incomplete metadata (n = 9), and non-relevant publications (n = 6) were removed. Subsequently, 92 records were screened, and 90 full-text articles were retrieved for detailed evaluation. The review was carried out in two phases: (i) title and abstract screening, and (ii) full-text assessment by two independent reviewers. Only studies meeting the following criteria were included:

(a) application of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), or Internet of Things (IoT) to photovoltaic (PV), solar thermal (ST), or hybrid photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems; (b) focus on energy modeling, climate control, or automation in greenhouses, dryers, or agrivoltaics systems; and (c) presentation of verifiable experimental or empirical data. The final dataset consisted of 79 articles published between 2012 and 2025, all meeting the quality standards, thematic relevance, and methodological rigor required for inclusion (Figure 1).

2.4. Bibliometric and Systematic Analysis

The bibliometric analysis was conducted in R 4.4.2 using Bibliometrix and Biblioshiny [25,26] to generate indicators of productivity, citation impact, co-authorship, international collaboration, and thematic co-occurrence. The resulting networks and clusters were visualized with VOSviewer 1.6.20. In parallel, the systematic review classified the findings into four main axes: (1) Thermal modeling and energy efficiency, (2) Predictive control and automation, (3) Integration of hybrid PV/T systems and advanced materials, and (4) Sustainability and agrivoltaics implementation. This integration made it possible to link bibliometric trends with the conceptual and technological evolution of the field, providing a coherent view of the advances and challenges shaping intelligent solar agriculture.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Number of Published Documents

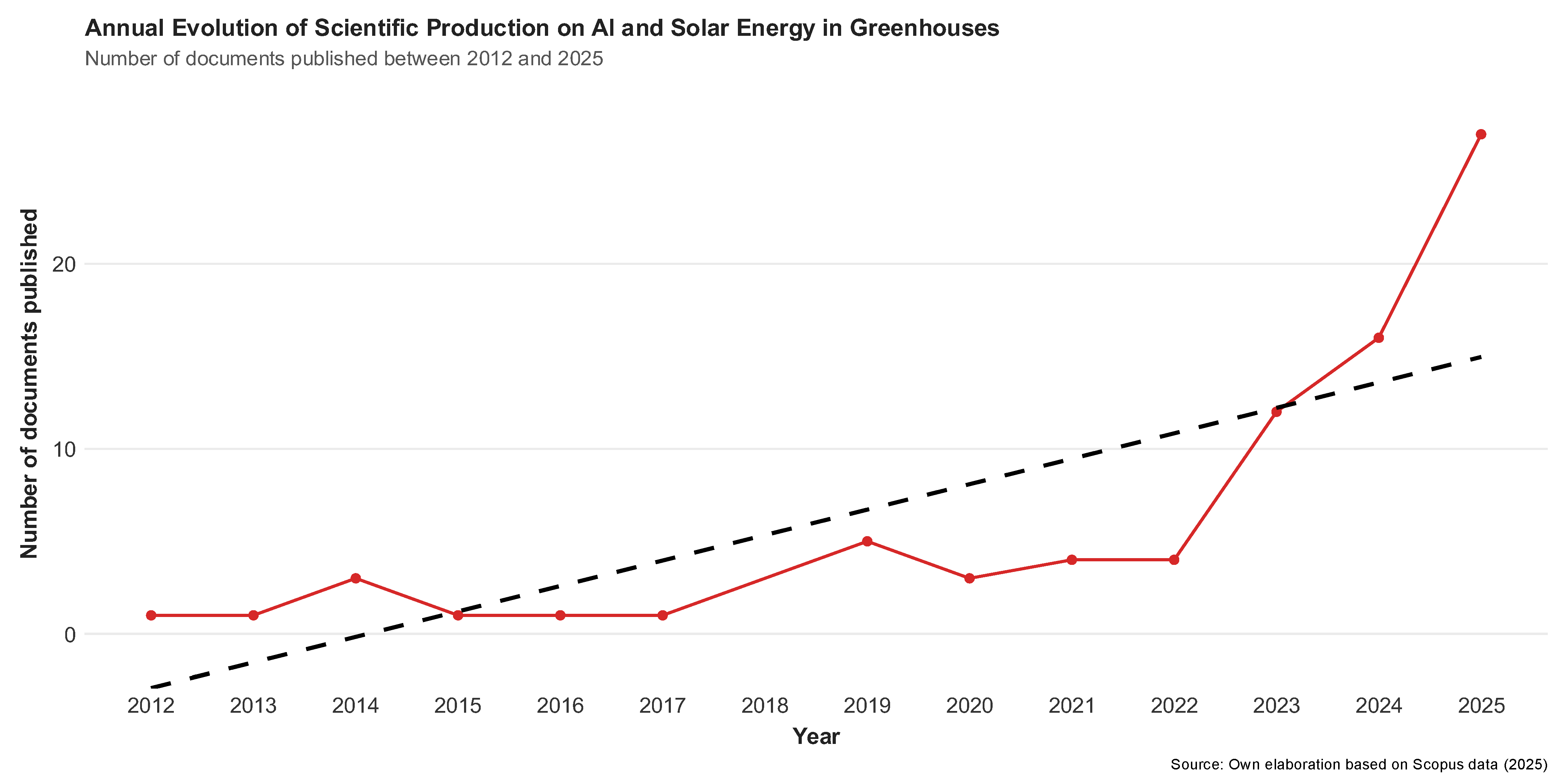

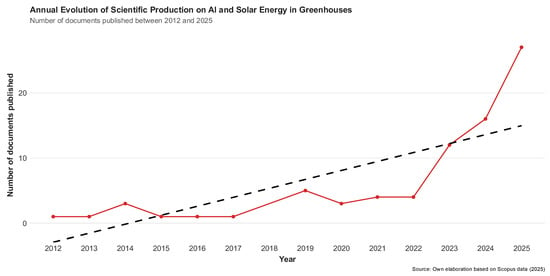

Scientific production on Artificial Intelligence (AI) applied to solar systems in controlled agricultural environments shows a sustained upward trend between 2012 and 2025 (Figure 2). The early years (2012–2016) represent an incipient stage, characterized by isolated studies mainly presented at international conferences on energy or automation focused on the basic modeling of photovoltaic (PV) systems and the first trials with artificial neural networks (ANNs) [27]. Since 2019, research has taken on a more interdisciplinary nature by integrating energy management with protected agriculture, marking the beginning of a more holistic approach to the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in agricultural solar systems. In this context, the development of various solar energy (SE) systems has been consolidated as one of the most relevant solutions to the rapid increase in global energy demand. These advances are directed toward optimizing the performance of solar devices under specific operating conditions, where intelligent system-based techniques, such as Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), play a fundamental role in improving the efficiency, stability, and adaptability of photovoltaic (PV) and thermal (ST) systems in controlled agricultural environments [28].

Figure 2.

Temporal trend of scientific production in the field of knowledge analyzed.

Since 2020, an accelerated growth is evident, reflecting the expansion of agricultural digitalization and the development of intelligent technologies for climate control [29]. Publications increased from three in 2020 to twelve in 2023, reaching twenty-seven in 2025, representing more than a fourfold rise in less than five years. This growth is associated with the application of Machine Learning (ML) algorithms and solar energy prediction models in hybrid photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems, as well as with the design of automation solutions supported by the Internet of Things (IoT) for energy and environmental management in greenhouses and energy generation systems [30].

The thematic analysis of the documents reveals three primary research fronts: (i) optimization and predictive control of photovoltaic (PV) and thermal (ST) systems using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to improve energy efficiency [31]; (ii) integration of renewable energy sources and storage systems aimed at achieving near-zero or positive-energy consumption greenhouses [32]; and (iii) data-driven applications for solar drying, smart irrigation, and microclimate regulation [33,34]. Likewise, recent studies demonstrate the consolidation of this field as a recognized domain within energy engineering and smart agriculture [8,35].

Taken together, the exponential growth of publications after 2021 reflects the convergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), renewable energy integration, and agricultural sustainability. The diversity of applications reviewed, ranging from predictive models for solar irradiance to autonomous microclimate control strategies, shows a shift from theoretical approaches toward implementable solutions. This trend consolidates the concept of the intelligent solar greenhouse as a key technological platform to achieve energy efficiency, sustainable production, and climate resilience in controlled agricultural environments.

3.2. Subject Areas Encompassed by the Scientific Field According to the Published Documents

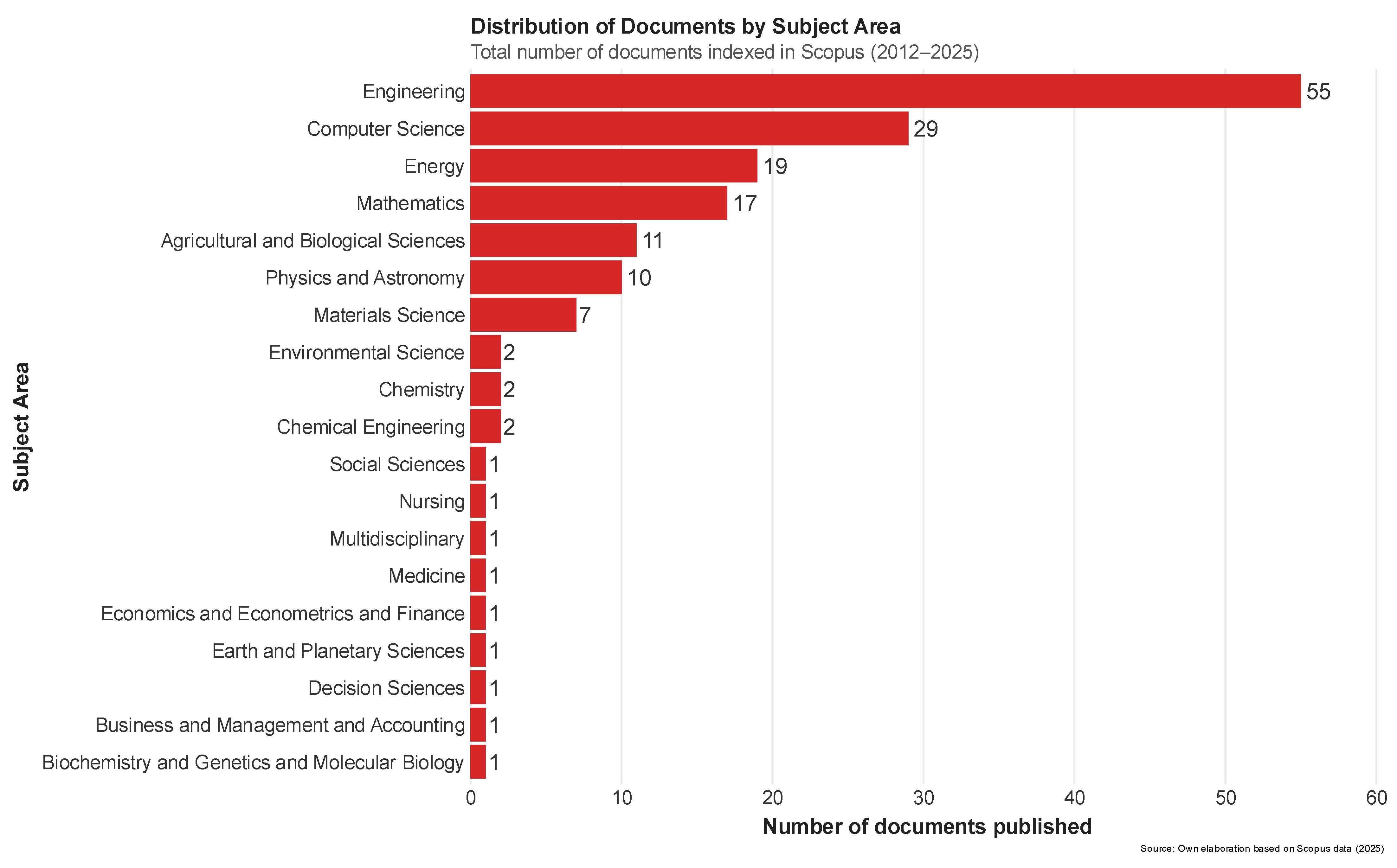

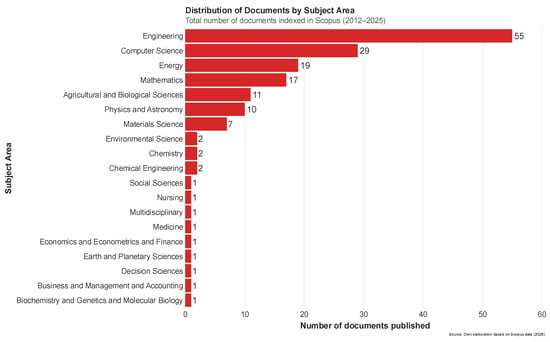

The subject-area analysis shows a clear predominance of the engineering disciplines in research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) applied to solar systems in controlled environments (Figure 3). Engineering leads production with 55 documents, followed by Computer Science (29) and Energy (19), reflecting the field’s technological orientation and its reliance on disciplines that combine modeling, automation, and energy optimization [33,36]. This distribution confirms that the application of AI in photovoltaic (PV) and thermal (ST) systems is firmly anchored in systems engineering, data analytics, and energy efficiency pillars underpinning the ongoing transition toward intelligent, self-sufficient agricultural infrastructures.

Figure 3.

Thematic areas to which the published documents in the analyzed field of knowledge are assigned.

At a second level, the areas of Mathematics (17), Agricultural and Biological Sciences (11), and Physics and Astronomy (10) appear, indicating an interdisciplinary approach that integrates theoretical foundations with practical applications in microclimate management and solar radiation [35,37]. These disciplines contribute quantitative methodologies, predictive models, and essential experimental analyses to improve energy efficiency and thermal stability in greenhouses or hybrid photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems [38,39]. Their growing presence reveals a shift from conceptual studies to empirical approaches, wherein mathematical simulation and radiation physics are integrated with crop biology to develop integrated agro-energy solutions.

Finally, the least represented areas, such as Environmental Sciences, Chemistry, Chemical Engineering, Social Sciences, and Medicine, each with only one or two publications, suggest opportunities to broaden the field’s perspective toward more sustainable and human-centered approaches. These disciplines could contribute through life-cycle assessments, socioeconomic analyses, and evaluations of environmental health associated with the use of renewable energy in protected agriculture. Overall, the observed thematic structure reinforces the emerging and cross-cutting nature of Artificial Intelligence (AI) research in agricultural solar systems, highlighting the need for stronger interdisciplinary collaboration to consolidate a comprehensive research framework that integrates technology, energy, environment, and agricultural productivity. It is also worth noting that a single article may fall within multiple subject areas.

3.3. Types of Published Documents

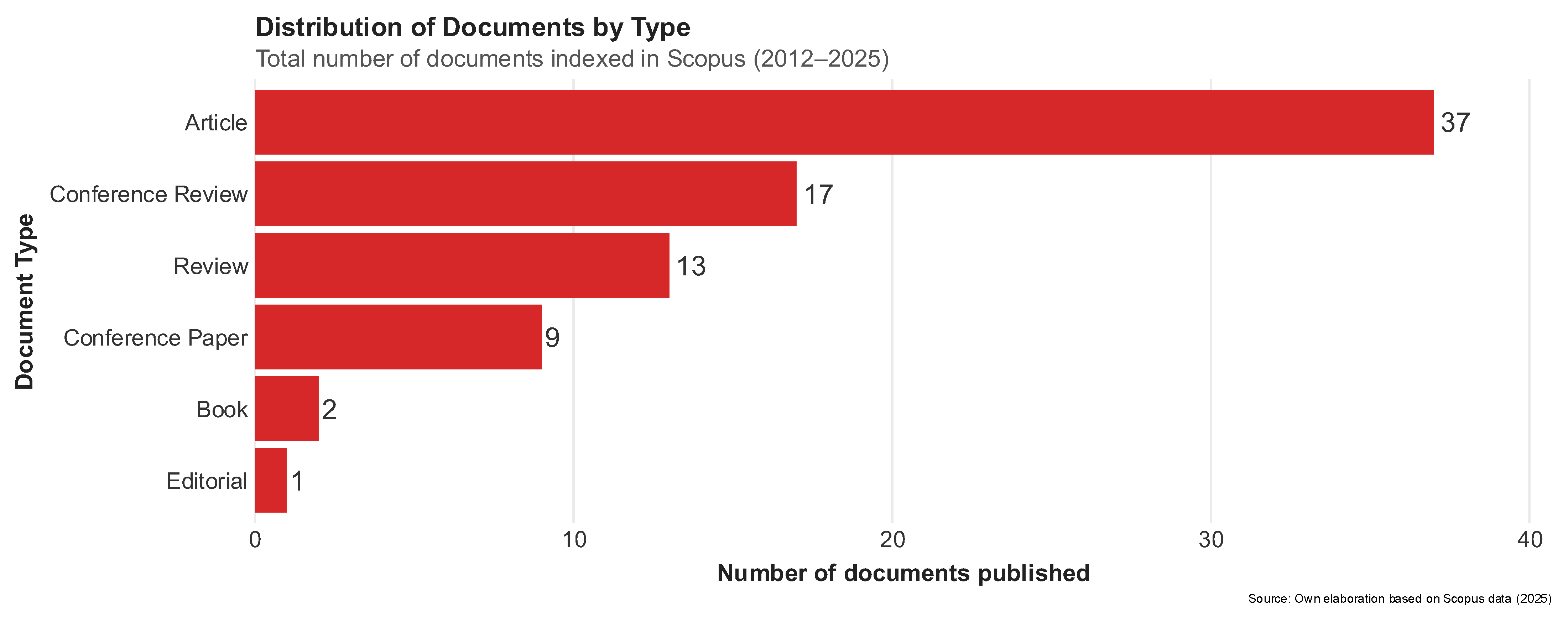

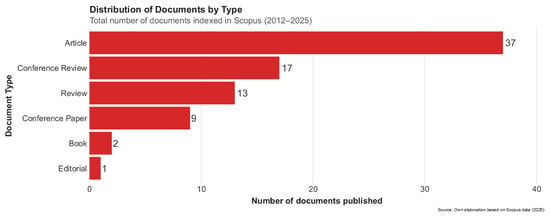

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the types of scientific documents published between 2012 and 2025 on Artificial Intelligence (AI) applied to solar systems in protected agriculture (Figure 4). From a scientific perspective, research articles (37 documents) constitute the main channel for disseminating knowledge, reflecting a field with high productivity and theoretical maturity in consolidation [40]. Secondly, review papers (13) and conference review articles (17) indicate a growing interest in synthesizing and critically analyzing recent advances, a sign of the epistemological structuring of the field. The presence of conference papers (9) reflects the dynamic exchange of preliminary results typical of emerging technological domains, while the few books (2) and editorials (1) suggest that knowledge is still predominantly disseminated through specialized media rather than extensive or outreach-oriented formats [41]. Taken together, this distribution depicts an expanding academic ecosystem oriented toward scientific validation, result replicability, and the construction of theoretical frameworks applied to energy efficiency and smart agriculture.

Figure 4.

Documents published by type of publication.

3.4. Countries Where the Publications Originate

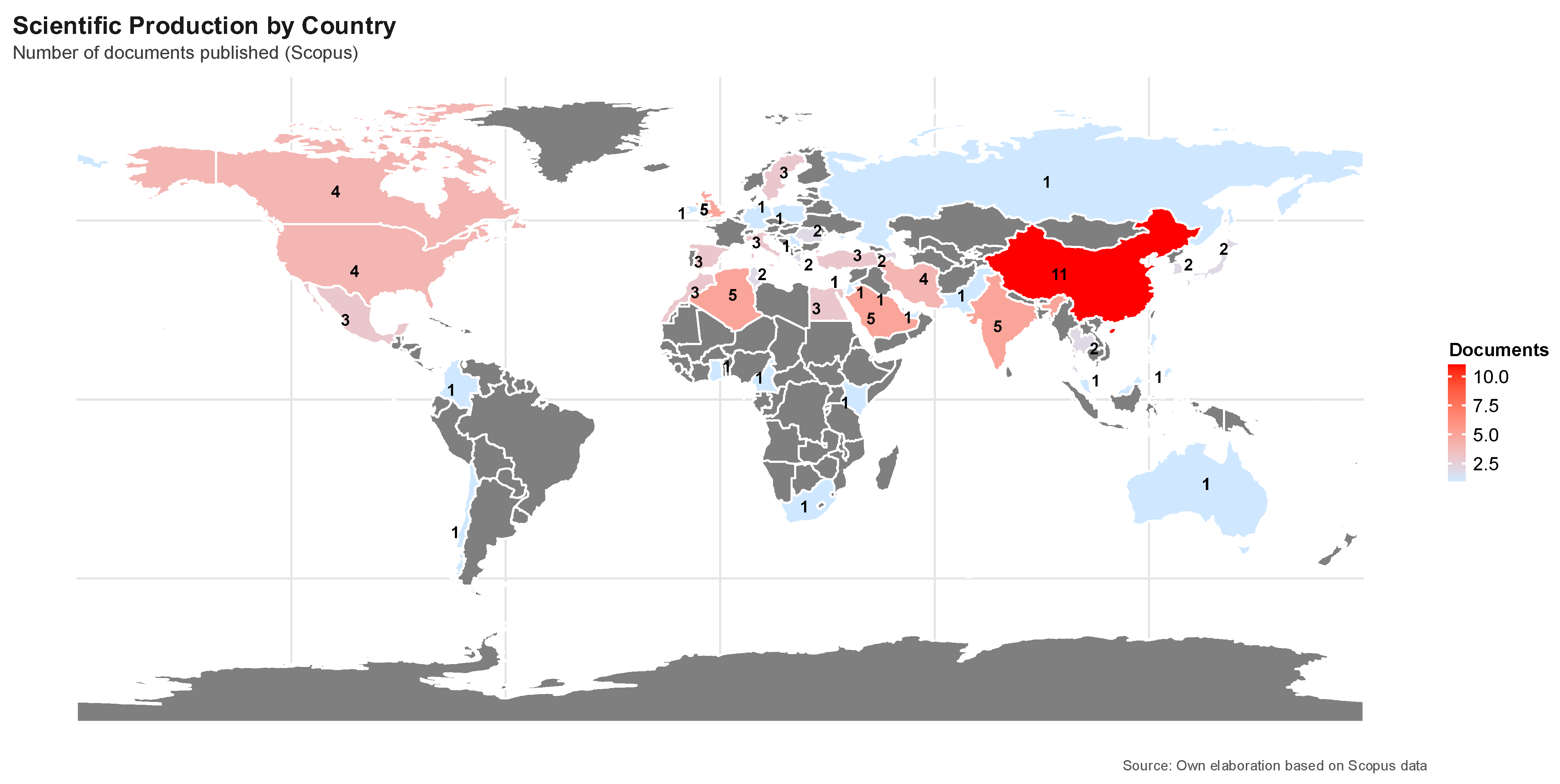

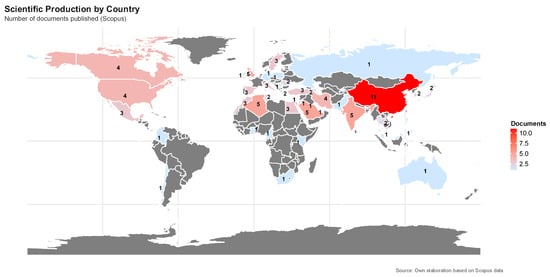

The map (Figure 5) shows the geographical distribution of scientific production related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) applied to solar systems in controlled agricultural environments. A strong concentration of publications is observed in Asia, led by China (11 documents), followed by India (5), Saudi Arabia (5), and Iran (4). This Asian leadership reflects sustained investment in solar energy technologies and AI applied to agriculture, as these countries have promoted policies for energy transition and smart farming [42,43]. China, in particular, stands out for combining innovation in computational intelligence with large-scale national solar agriculture projects developed in recent years [44].

Figure 5.

Geographical distribution of publications.

In Europe, production is more evenly distributed, with consistent contributions from the United Kingdom (5), Sweden (3), Spain (3), Italy (3), and Germany (1). This balanced distribution is strongly influenced by the European Union’s coordinated legislative and funding frameworks, which promote multi-country participation rather than concentrating scientific output in a single nation. Recent bibliometric analyses show that EU-wide policies, such as the Renewable Energy Directive and the 2021 regulation on Renewable Energy Communities (REC) have stimulated parallel research development across Italy, Austria, Germany, Portugal, and the Netherlands, resulting in diversified but complementary scientific contributions [45,46,47]. The rapid expansion of REC-related research, with an annual growth rate of 42.82% and more than 200 publications predominantly from EU countries, further demonstrates how shared policy instruments and coordinated funding mechanisms foster cross-border collaboration and drive a more evenly distributed scientific landscape in Europe. This pattern suggests a more diversified scientific collaboration, where studies focus on modeling, thermal optimization, and sustainable energy policies. Although smaller in volume than Asia’s output, European participation demonstrates a high level of interdisciplinarity and a strong technical-scientific focus on energy efficiency [48], hybrid system integration [49], and greenhouse monitoring and automation [50].

In the American and African contexts, contributions are still incipient but strategically significant. In the Americas, the United States (4), Canada (4), Mexico (3), and Colombia (1) represent focal points for technological transfer toward smart agriculture. In Africa, countries such as Algeria (5), Egypt (3), and South Africa (1) reveal a growing interest in solar energy solutions adapted to arid climatic conditions. Overall, the global distribution shows that research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and solar energy applied to agriculture is in a consolidation phase, with strong Asian and European leadership and significant potential for expansion in Latin America and Africa, where challenges related to energy sustainability and food security are most critical.

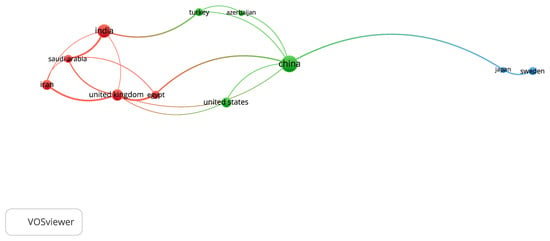

3.5. Co-Authorship Network Among Countries

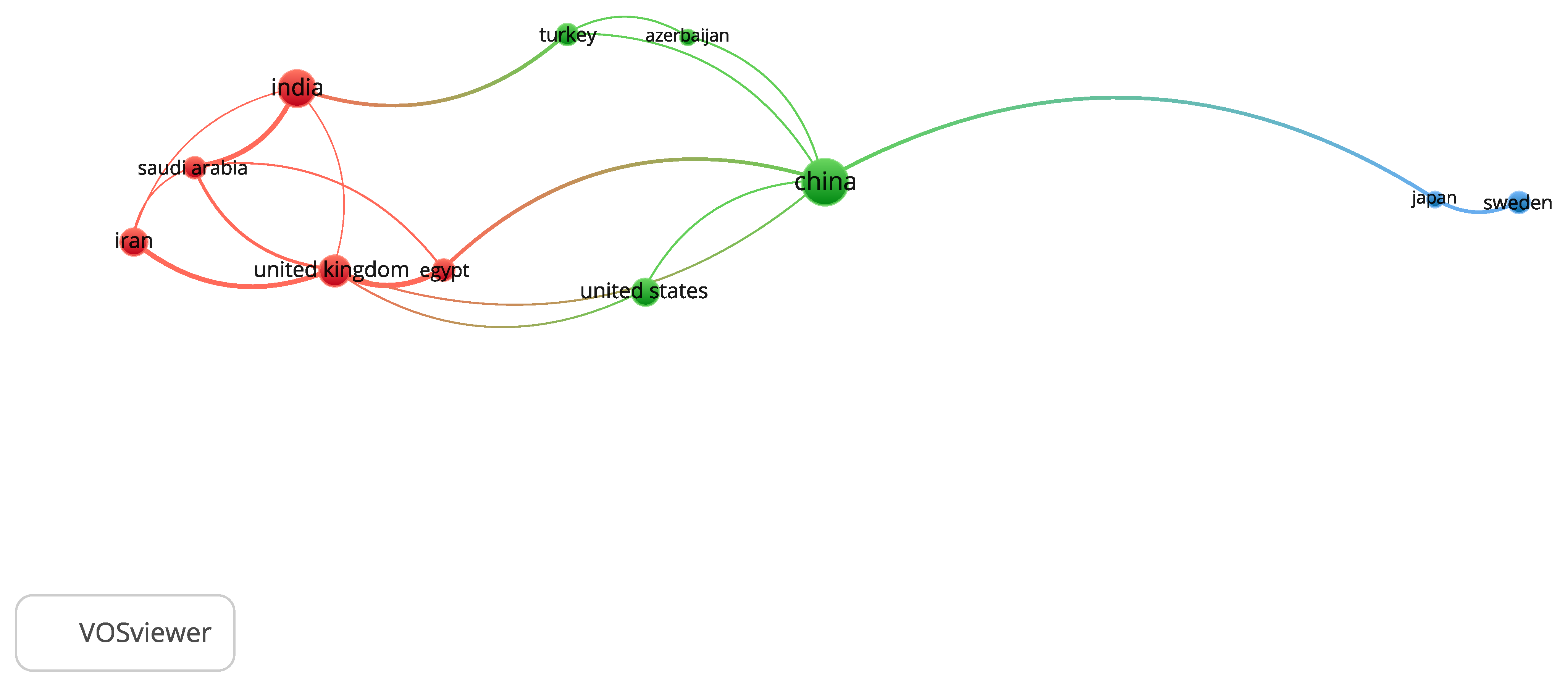

The co-authorship network (Figure 6) among countries represents international collaborations in scientific publications related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and solar energy applied to protected agriculture. Each node corresponds to a country, and its size is proportional to the number of published documents; the lines (links) indicate ties of scientific cooperation through shared co-authorships among institutions from different nations [51]. In this analysis, conducted with VOSviewer, 11 countries were identified and grouped into three collaboration clusters, with a total link strength of 13.5, indicating a moderate degree of global interconnectedness within the field.

Figure 6.

Co-authorship network among countries.

The United Kingdom appears as the country with the highest total link strength (5), followed by China (4) and India (3), suggesting their central role in shaping scientific collaboration networks. China, in addition to leading in the number of publications, acts as a bridging node among regions in Asia, Europe, and North America, establishing connections with the United States, Turkey, and Azerbaijan [52]. The second cluster is dominated by the India–Saudi Arabia–Iran–United Kingdom axis, reflecting regional cooperation driven by shared interests in solar harvesting, novel equipment design for thermal utilization, agricultural automation, and seawater greenhouses [53,54,55]. The smallest cluster connects Japan and Sweden, indicating a more specialized collaboration oriented toward precision technological developments for indoor plant factories (PFALs, Plant Factories with Artificial Lighting) [56].

Overall, the network reveals a still fragmented collaboration structure, where partnerships are concentrated in countries with high technological capacity and advanced energy policy frameworks. Although Africa has only a marginal presence (Egypt, Algeria), its connections with research centers in China and Europe offer opportunities to expand cooperation and strengthen knowledge transfer. This pattern suggests that the scientific field evolves from regional networks toward global strategic alliances, where Artificial Intelligence (AI) and renewable energies are consolidating as central axes of international scientific convergence

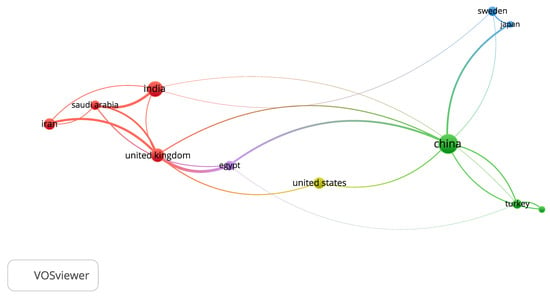

3.6. Bibliographic Coupling Network

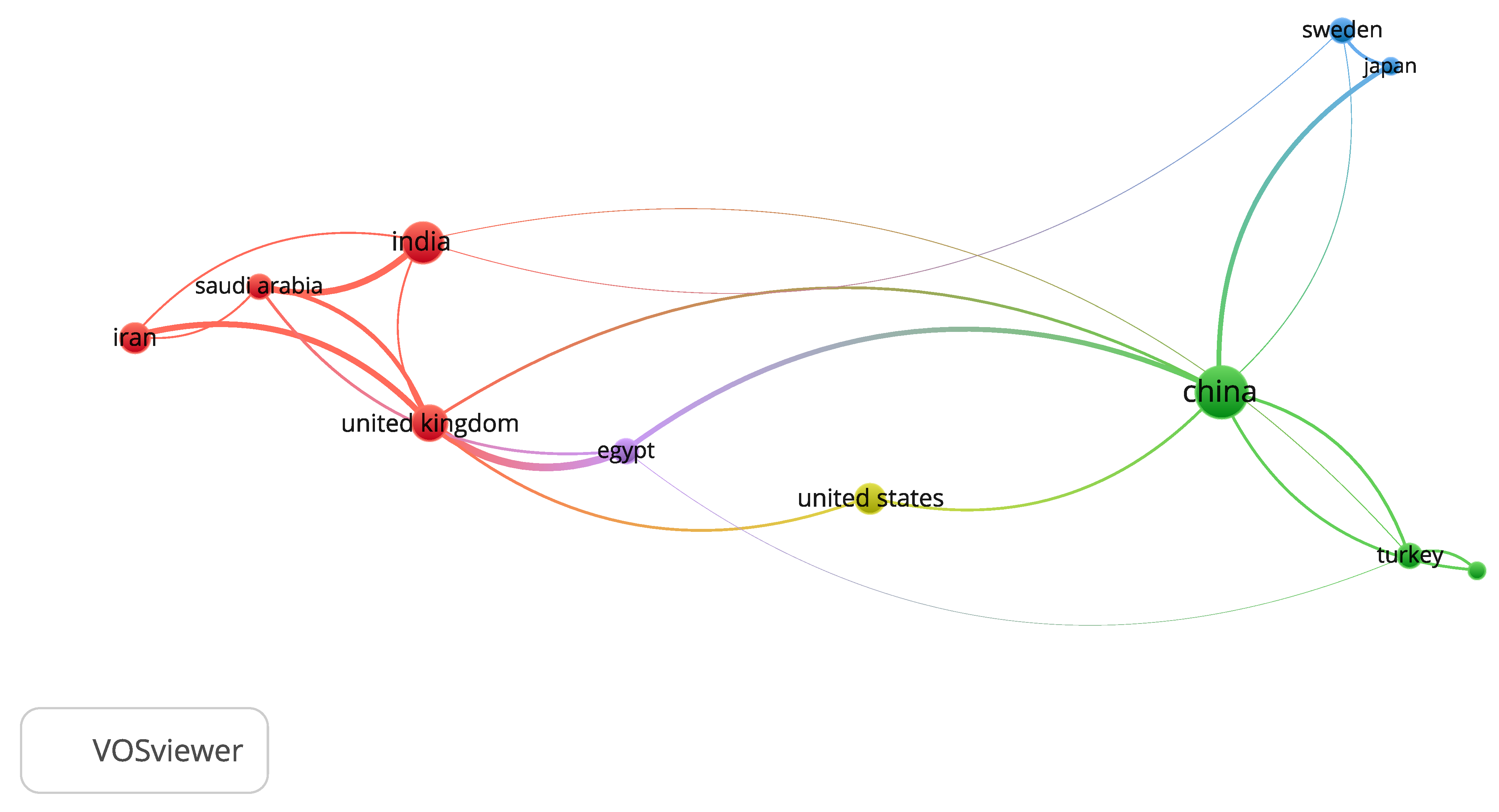

The bibliographic coupling network (Figure 7) among countries represents the degree of relatedness between nations based on the references they share in their scientific publications. In this type of analysis, two countries are connected when their documents cite the same sources, reflecting thematic and methodological alignment rather than direct collaboration. Each node on the map corresponds to a country, whose size is determined by the number of publications, while the thickness of the links indicates the strength of the bibliographic coupling (i.e., the number of shared references between them) [57].

Figure 7.

Bibliographic coupling network between countries.

The United Kingdom (48), China (40), and Egypt (30) stand out as the nodes with the highest link strength, positioning them as intellectual reference points within the field by integrating bibliographies widely cited by other nations. China also acts as a connecting hub with the United States, Turkey, and Japan, consolidating a scientific influence block with a strong focus on solar technologies and agricultural automation. The second cluster includes India, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom, reflecting the adoption of shared knowledge bases in topics such as energy efficiency, thermal modeling, and machine learning. Finally, countries such as Sweden and Japan form a smaller cluster oriented toward experimental approaches and advanced modeling. Overall, the network reveals a research ecosystem in which bibliographic connections transcend geographic boundaries, consolidating a shared sphere of scientific influence around Artificial Intelligence (AI) and energy integration in protected agriculture.

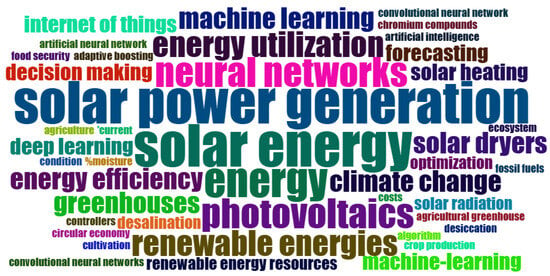

3.7. Most Frequently Used Author Keywords

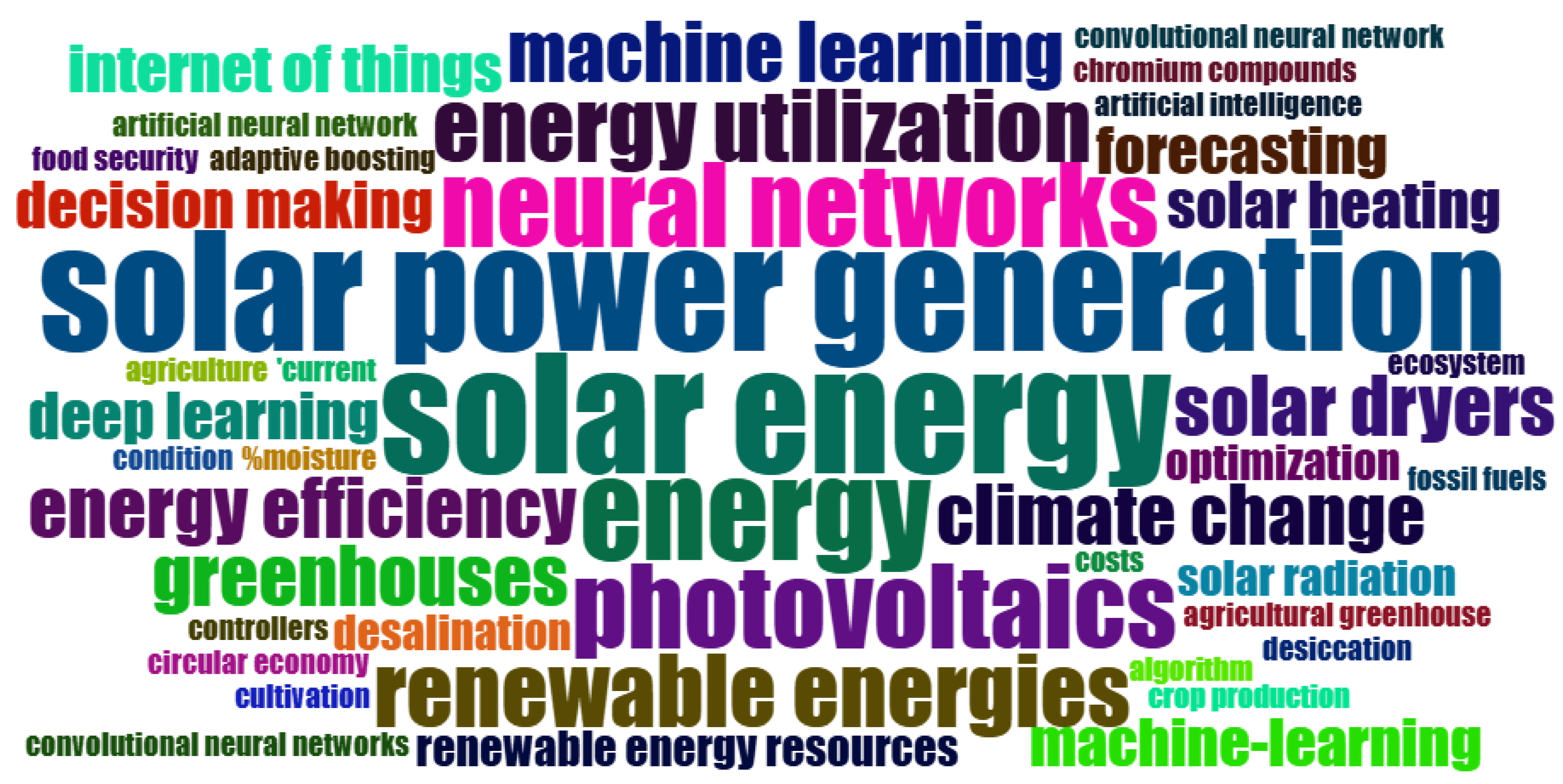

The term co-occurrence analysis (Figure 8) reveals the principal conceptual cores structuring research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and solar energy in protected agriculture. The most frequent terms solar energy (10), solar power generation (10), energy (8), neural networks (7), and photovoltaics (7), underscore the centrality of energy conversion and intelligent modeling as the field’s main axes [58,59]. This group constitutes the methodological core, focused on optimizing the capture and conversion of solar radiation in photovoltaic–thermal (PV/T) systems and solar dryers through machine learning (ML) techniques [34].

Figure 8.

Word cloud of author keywords.

At a second level of relevance, terms associated with energy efficiency and environmental sustainability appear, such as energy utilization (6), renewable energies (6), climate change (5), energy efficiency (5), and greenhouses (5). This set reflects the field’s orientation toward the integration of renewable sources and adaptive energy management in controlled environments, where Artificial Intelligence (AI) serves as a tool for optimizing the thermal and light balance [50,60]. The recurrence of “greenhouses” and solar dryers confirms the applied emphasis on sustainable solar agriculture and on climate change mitigation [48,54].

Finally, the presence of emerging terms such as deep learning, internet of things, machine learning, forecasting, and decision making indicates the expansion of the field toward predictive analytics and integrated automation. These keywords reflect the transition from empirical models to control architectures based on climatic, microclimatic, and energy data [52,55]. Taken together, the terminological network demonstrates that current research is moving toward intelligent, interconnected, and resilient agricultural systems in which Artificial Intelligence (AI) and solar energy constitute a fundamental dyad for the sustainability and self-sufficiency of future agriculture. These conceptual cores interrelate within a complex thematic structure that will be examined in the following section through co-occurrence networks and semantic clustering, where the clusters articulate AI, solar energy, and agricultural sustainability become apparent.

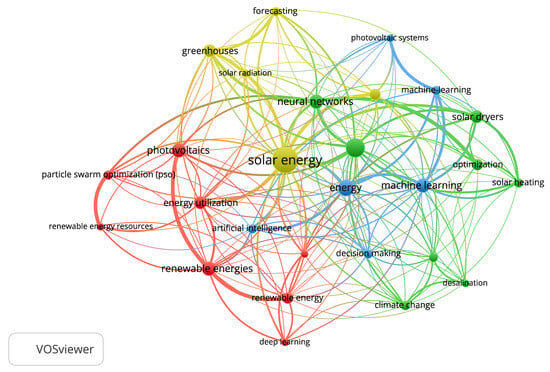

3.8. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

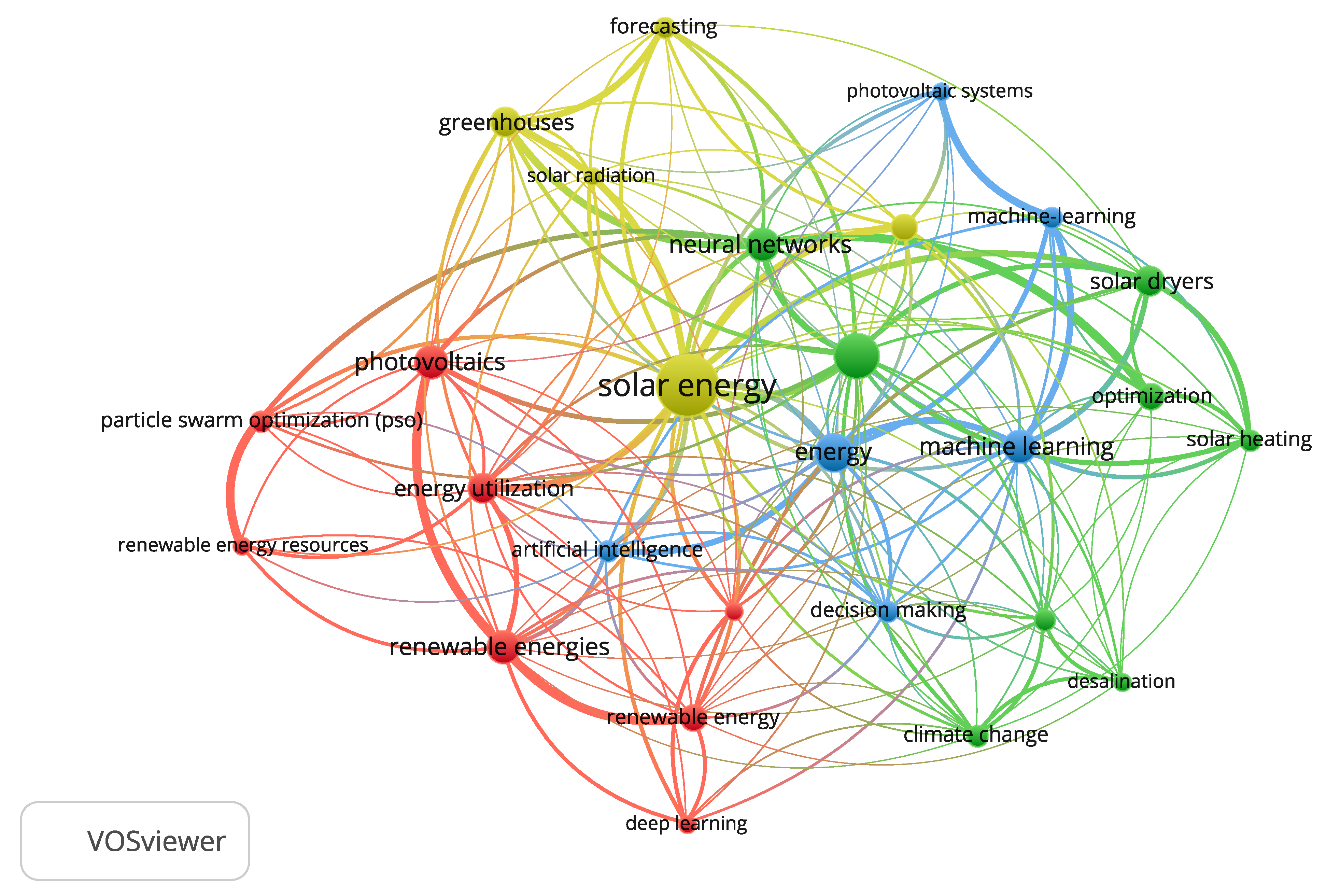

The keyword co-occurrence network (Figure 9) displays the semantic relationships among the terms used in the analyzed documents, revealing the principal thematic axes and the connections between the field’s most representative concepts [61]. Each node represents a keyword, whose size is proportional to its frequency of occurrence, while the lines (links) indicate its co-occurrence within the same articles. The different colors correspond to four thematic clusters that group terms according to their conceptual affinity. This multi-cluster structure highlights the intersection of Artificial Intelligence (AI), solar energy, and protected agriculture as a scientific domain in rapid consolidation.

Figure 9.

Keyword co-occurrence network.

Yellow Cluster—Solar Energy and Agricultural Applications: This cluster is dominated by the term’s solar energy, solar radiation, solar power generation, and greenhouses, which represent the central axis of the research. It focuses on the direct application of solar energy in controlled agricultural systems, such as greenhouses or solar dryers, prioritizing thermal and photovoltaic utilization. The emphasis lies on the capture, conversion, and distribution of heat and solar radiation to maintain or adjust optimal microclimatic conditions (temperature, humidity, CO2, and light), forming the energetic foundation for agricultural automation and emissions reduction. [38,59,60].

Red Cluster—Energy optimization and intelligent renewable resources: This cluster brings together the term’s photovoltaics, energy utilization, renewable energies, renewable energy resources, internet of things, and deep learning. This set reflects the convergence between photovoltaic (PV) technologies and deep Artificial Intelligence (AI) models applied to the utilization of renewable energies in protected or controlled agricultural environments [56]. The studies within this group focus on optimizing the performance of solar systems through deep learning techniques and predictive algorithms that enable the estimation of energy efficiency, fault detection, and improved real-time conversion control [62]. The presence of the Internet of Things (IoT) underscores the transition toward intelligent, connected energy infrastructures, in which sensors, neural networks, and machine learning (ML) algorithms cooperate to integrate photovoltaic production with agricultural and environmental demand [63,64]. In summary, this cluster represents the methodological–technological core of the field, in which deep learning enhances efficiency, automation, and the sustainable management of solar energy resources [50].

Green Cluster—Intelligent Modeling and Energy Sustainability: This cluster includes the terms solar power generation, solar heating, solar dryers, optimization, neural networks, and sustainable development. This group represents the applied and integrative core of the research, where Artificial Intelligence (AI) models converge with thermal and solar generation systems to enhance energy efficiency and sustainability. Neural networks are employed as predictive tools to simulate the thermal and radiative behavior of solar systems, adjusting variables such as heat flux, air temperature, and conversion efficiency [28,36,50]. In parallel, studies on solar heating and solar dryers demonstrate the importance of passive, low-consumption solutions for agricultural drying and greenhouse climate conditioning [34,38,58]. Finally, the inclusion of sustainable development highlights the cluster’s environmental and socioeconomic dimension, wherein energy optimization seeks not only to maximize technical performance but also to promote sustainable transitions toward resilient, low-climate-impact solar agriculture [33,54].

Blue Cluster—Artificial Intelligence and Predictive Modeling: The blue cluster integrates the terms machine learning, neural networks, energy efficiency, decision making, and photovoltaic systems. It represents the methodological link of the field, focused on the use of machine learning (ML) algorithms for the prediction, optimization, and intelligent control of solar systems [49,52,64]. The connection between energy efficiency and decision making reflects progress toward autonomous management models, in which Artificial Intelligence (AI) not only predicts energy performance but also adjusts operational parameters to maximize productivity and sustainability [65,66]. Taken together, these four clusters reveal an interconnected scientific structure: solar energy forms the physical core (yellow), photovoltaic systems and their technological integration (red) provide the instrumental foundation, intelligent systems optimize thermal applications (green), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) (blue) functions as the analytical layer that enables intelligent and energy-efficient solar agriculture.

3.9. Strategic Analysis of the Thematic Structure: Convergence Among Artificial Intelligence, Solar Energy, and Agricultural Sustainability

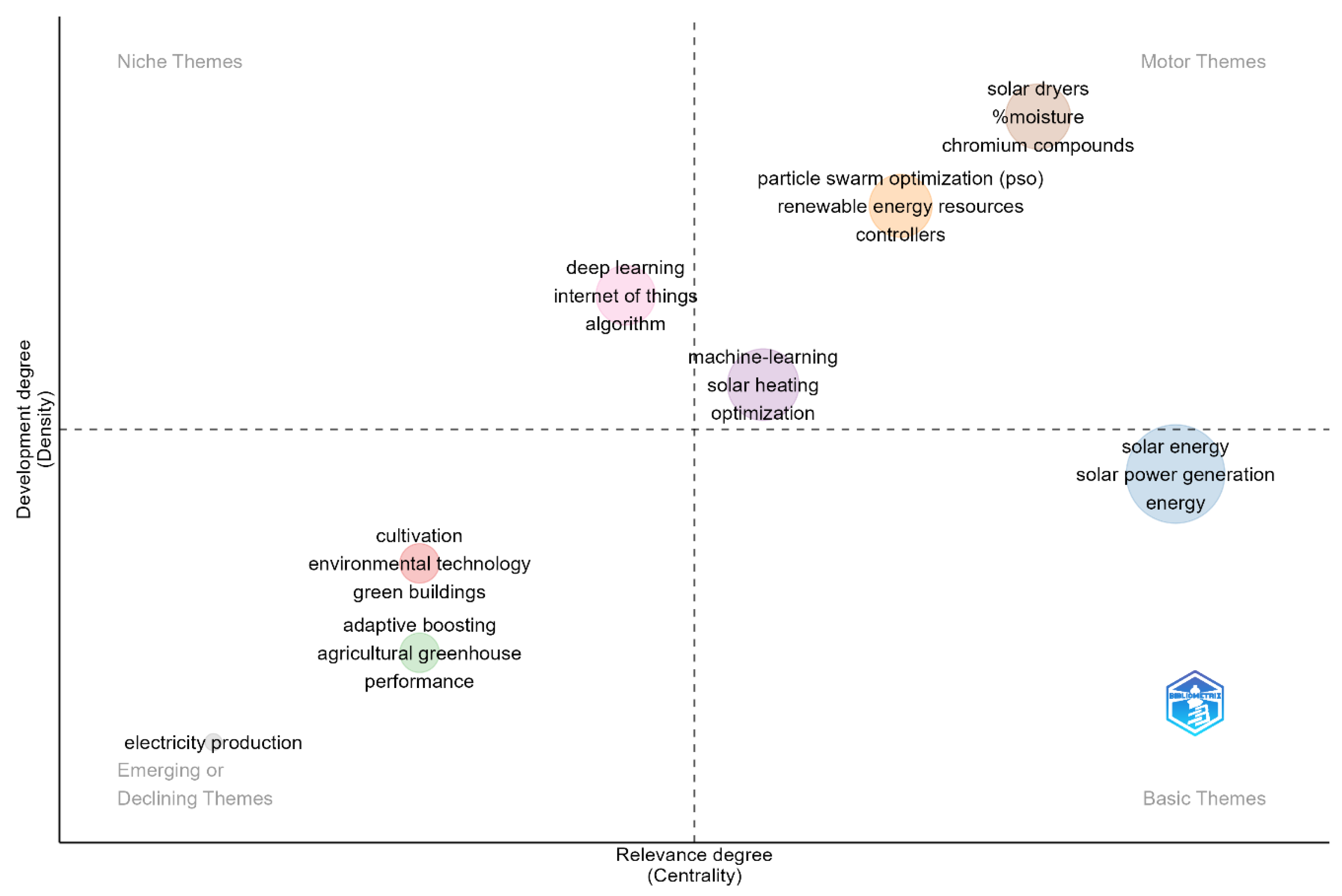

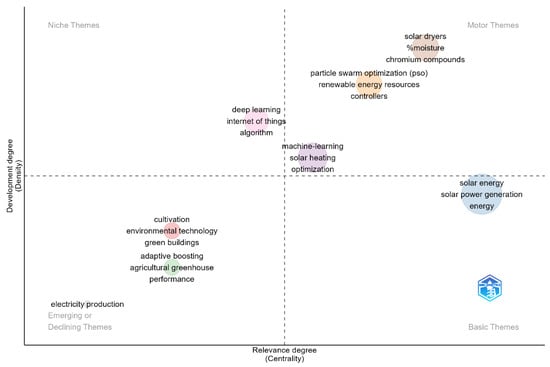

Figure 10 presents a strategic thematic map, which is considered a fundamental tool in bibliometric analysis and in assessing the intellectual structure of a scientific field [67]. This type of representation is based on density (vertical axis), which expresses each theme’s internal development or cohesion, and centrality (horizontal axis), which indicates its level of connection or influence with other research areas [68]. The combination of these two parameters allows thematic clusters to be classified into four categories: motor themes (high density and high centrality), niche themes (high density and low centrality), basic themes (low density and high centrality), and emerging or declining themes (low density and low centrality). This structure helps to understand the dynamics of knowledge evolution, the maturity of research lines, and the potential scientific development trajectories within the studied domain [57].

Figure 10.

Thematic structure of the analyzed field of knowledge.

In the motor themes quadrant, located in the upper-right section, concepts such as solar dryers, renewable energy resources, particle swarm optimization (PSO), chromium compounds, and controllers occupy the most dynamic and advanced core of the field. Their position reflects a high level of methodological and technological consolidation, evidencing the convergence of solar energy, thermal optimization, adaptive control, and Artificial Intelligence (AI). These topics are directly related to the trends identified in the systematic review, where intelligent solar dryers and hybrid control and prediction models based on Machine Learning (ML) represent the main pillars of innovation toward energy-efficient agricultural systems. The integration of phase change materials (PCMs), optimization algorithms such as PSO or deep learning, and predictive maintenance strategies reinforces the role of these themes as drivers of the transition toward autonomous, digital, and low carbon protected agriculture.

Meanwhile, niche themes such as deep learning, internet of things, and algorithm exhibit high density but lower centrality, indicating highly specialized research lines that are still in the process of integration with other areas of the field. These emerging trends align with the recent evolution described in the review, where the use of AI, neural networks, and IoT communication is being consolidated as a transversal development axis for climate management, energy control, and agricultural automation.

In contrast, basic themes such as solar energy, solar power generation, and energy represent the technological foundations upon which the entire knowledge system is built, reflecting their structural relevance in photovoltaic, thermal, and agrivoltaics modeling. Finally, emerging or declining themes including electricity production, environmental technology, and adaptive boosting can be interpreted as conceptually evolving areas that may be redirected toward new applications involving renewable energy integration, fuzzy optimization, and life-cycle analysis. Overall, the map confirms the scientific maturity and technological directionality of the field toward intelligent, hybrid, and sustainable agricultural systems, where AI and solar energy serve as convergence axes for efficiency, decarbonization, and climate resilience in contemporary protected agriculture.

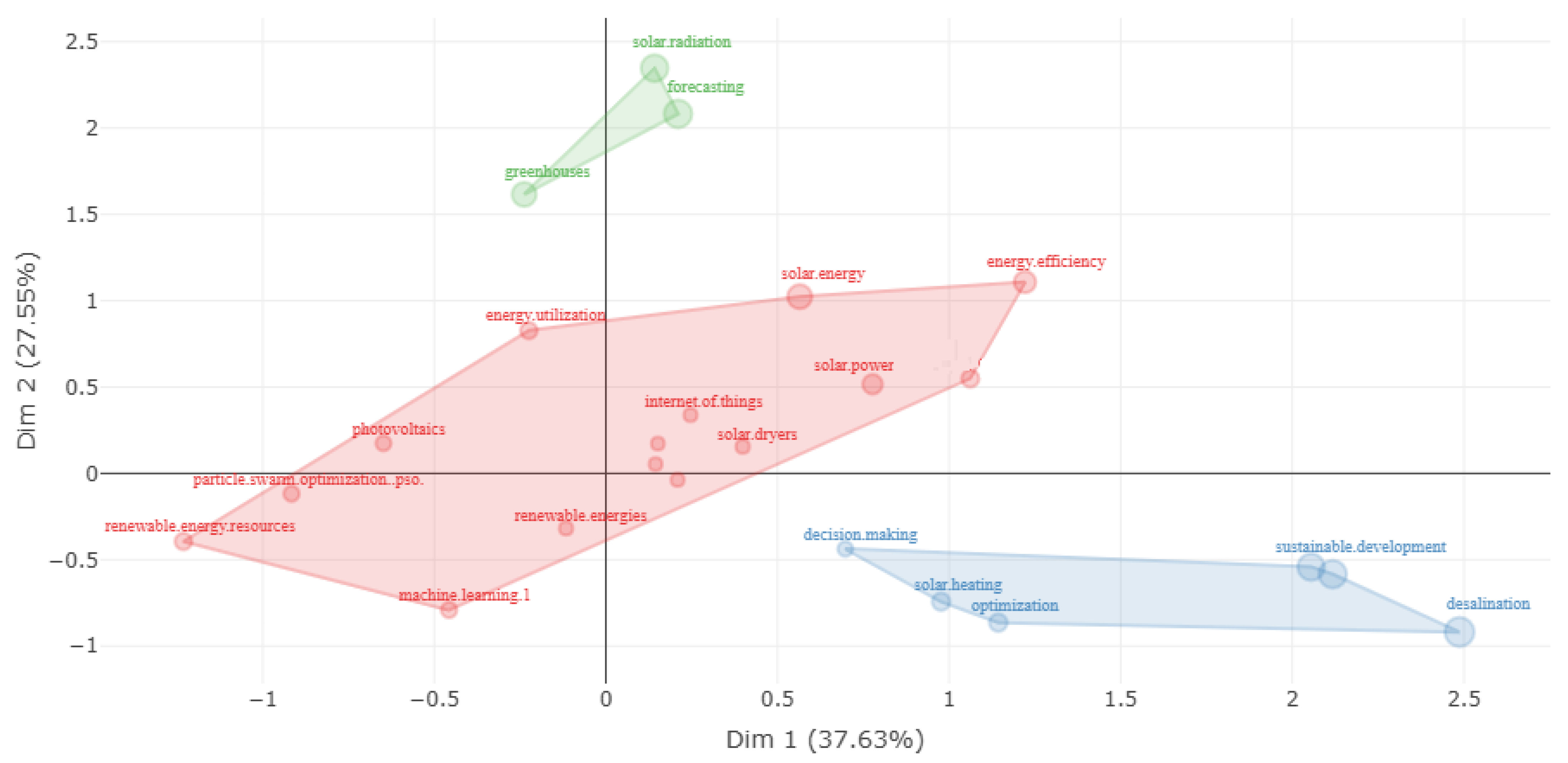

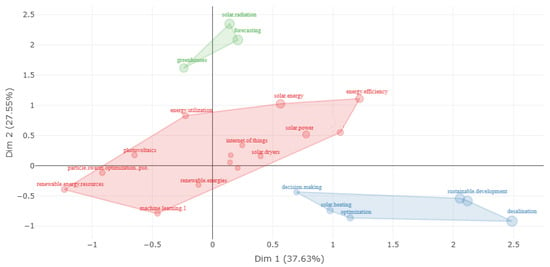

3.10. Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Thematic Convergence: Integration of Artificial Intelligence, Sustainability, and Solar Energy in Protected Agriculture

Figure 11 corresponds to a co-word map (co-occurrence of keywords), a technique used in bibliometric studies to visualize the conceptual relationships among the most frequent terms in the analyzed literature [22]. Each point represents a keyword, and the distances between them reflect their degree of semantic association: the closer they are, the higher their co-occurrence in the articles. The axes Dim 1 (37.63%) and Dim 2 (27.56%) indicate the percentages of explained variance, that is, the proportion of thematic information captured by the two main dimensions of the map. Together, both dimensions explain 65.19% of the semantic structure of the field, demonstrating a high level of consistency in the co-occurrence patterns. The colors represent clusters of interrelated topics identified through similarity-based clustering algorithms, which reveal the conceptual cores of research on solar energy, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and protected agriculture.

Figure 11.

Multiple correspondence analysis of the knowledge area.

The red cluster represents the dominant and most consolidated core, associated with solar energy, energy efficiency, machine learning, energy utilization, photovoltaic systems, and renewable resources. This thematic set demonstrates the scientific maturity of the axis linking energy optimization with the use of AI in photovoltaic and thermal systems. The connections between particle swarm optimization (PSO) and machine learning reinforce the centrality of evolutionary optimization algorithms in the design of intelligent controllers and predictive models, as documented in the systematic review, where the hybridization of AI with PV/T systems and the integration of phase change materials (PCMs) showed significant increases in thermal and energy efficiency. This cluster therefore constitutes the technological innovation core, where automation, thermal modeling, and machine learning converge to enhance agricultural energy management.

Meanwhile, the blue cluster focuses on sustainability and technological governance dimensions, integrating terms such as sustainable development, decision making, and desalination. This group reflects the expansion of the field toward a holistic vision of sustainability, in which AI- and solar-based solutions aim not only for technical efficiency but also for positive environmental and social impact. Finally, the green cluster, formed by solar radiation, greenhouses, and forecasting, represents the emerging line that links solar resource optimization with protected agriculture, indicating a trend toward advanced microclimatic modeling and intelligent control systems. Overall, the map confirms that recent research is moving from a techno-energetic perspective toward an integrated paradigm of sustainability, computational intelligence, and climate resilience consistent with the findings of the systematic review on the evolution of knowledge in intelligent solar greenhouses.

3.11. Subsection Artificial Intelligence and Solar Energy in Smart Greenhouses: Integration, Control, and Sustainability in PV/T Systems

The recent development of protected agriculture has been driven by the convergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), photovoltaic (PV) and thermal (T) solar energy, together with agricultural automation systems, giving rise to a new generation of smart greenhouses. These infrastructures operate as integrated energy ecosystems capable of generating, storing, and managing renewable energy through predictive and adaptive models. Deep learning algorithms, artificial neural networks (ANNs), and intelligent controllers make it possible to address the complexity of microclimatic processes, optimizing energy efficiency and reducing dependence on fossil sources, in line with global sustainability goals.

The study of Zhou et al. [69], constitutes a methodological benchmark in residual heat prediction using AI, combining a heat recovery system with a photovoltaic (PV) pump and a deep residual neural network (ResNet), achieving R2 values between 0.890 and 0.929 and an energy saving of 79%. AI’s capacity to model nonlinear relationships among temperature, radiation, humidity, and wind demonstrates its superiority over traditional physical models, evidencing its potential to establish dynamic strategies for thermal recovery and microclimate regulation in high-efficiency PV greenhouses. Complementarily, Zanol et al. [37], optimized the energy management of controlled lighting using AI in a solar-powered greenhouse with battery storage, achieving a 15.3% reduction in energy cost and maintaining physiological stability in Caprese F1 tomatoes. This work demonstrates the synergy among AI, light management, and photovoltaic efficiency in plant production.

From the perspective of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV), Liao et al. [44] distinguished fully covered configurations, suitable for low-light-demand crops, and partially covered designs (20–80% shading), appropriate for common vegetables. The study highlighted a thermal penalty of approximately 0.48%/°C in PV efficiency and proposed PV/T (photovoltaic–thermal) integration to cool the modules, stabilize the microclimate, and valorize residual heat for heating or drying. This strategy positions the BIPV–PV/T pathway as a key design axis for self-sufficient greenhouses, where shading patterns and thermal recovery are established as critical control variables. In a parallel review, Yao et al. [70] conducted a comprehensive analysis of the interaction among light, temperature, and humidity, identifying seven priorities for the future of solar-protected agriculture: integration of renewable energies, automated microclimate management, consideration of soil as a thermal modulator, use of selective light spectra, regionalization of radiation models, life cycle assessment, and standardization of design criteria.

Recent experimental and modeling studies conducted in Mediterranean and temperate climates further reinforce the potential of BIPV as a high-impact design strategy for solar-assisted agriculture. Evidence from photovoltaic greenhouses shows that semi-transparent or spectrally selective BIPV modules installed on roofs or façade elements can supply a substantial share of the on-site electricity demand often supporting a significant portion of ventilation, heating, and circulation loads while simultaneously reducing solar heat gains and moderating indoor temperature [71,72,73,74,75,76]. Complementarily, recent reviews highlight that emerging tunable-transmittance PV technologies, organic photovoltaics, and perovskite–silicon tandem structures can optimize the trade-off between PAR transmission and energy generation, enabling envelope designs that adapt dynamically to crop requirements throughout the production cycle [77,78,79,80]. Together, these findings underscore that BIPV from conventional crystalline modules to next-generation flexible or semi-transparent devices constitutes one of the most promising pathways for achieving energy-autonomous, climate-resilient greenhouse systems.

In the same vein, Espitia et al. [58], contextualized the scientific evolution of the field of solar energy applied to protected agriculture through a bibliometric analysis that reveals the sustained growth of research on hybrid PV/T systems. The study highlights the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in optimizing climate and energy control, as well as the need to incorporate solar storage and desalination technologies in arid environments, projecting that the combination of AI, solar energy, and water management strategies will be essential for future agricultural resilience. In turn, Tao et al. [63], expanded the scope to the urban realm by integrating the Internet of Things (IoT) and fuzzy control in rooftop greenhouses. Using an STM32 controller and LoRa/NB-IoT communication, the APSO-FUZZY-PID algorithm and the GWO-BP (Gray Wolf Optimizer–Back Propagation) neural network achieved high accuracy and stability, marking progress toward digitized, low-energy urban agriculture. On the other hand, Solis et al. [60], proposed a distributed AI-based solar control architecture capable of estimating energy production and adaptively adjusting artificial lighting, thereby reducing grid dependence and laying the foundation for intelligent agricultural microgrids.

Advances in smart materials and coverings, analyzed by Maraveas et al. [81], consolidate the transition toward autonomous protected agriculture. The new photovoltaic coverings incorporate smart materials, IoT sensors, and optimization algorithms that enhance thermal autonomy and reduce operational costs by 40–60%. The study emphasizes three main axes: automated PV systems integrated with artificial neural networks (ANNs) and IoT; optimization of power conversion efficiency (PCE) and panel generation factor (PGF); and the development of advanced materials such as quantum dots, semitransparent solar cells, and 3D-printed modules. Although commercial limitations persist, technologies such as amorphous tungsten oxide (WO3) electrochromic films allow modulation of solar radiation and improvement of internal thermal stability, defining the concept of a net-zero energy greenhouse, where solar harvesting and AI regulate the productive environment with minimal external intervention.

The work of Olabi et al. [48], expands the discussion toward the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), demonstrating how the integration of solar thermal and PV/T systems with Artificial Intelligence (AI) directly contributes to SDGs 2, 7, 9, and 13. This approach highlights the role of AI as a catalyst for technical, environmental, and social sustainability. In practical application, the implementation of hybrid PV/T systems equipped with intelligent controllers has enabled real-time optimization of heat recovery, irrigation, and lighting, reducing energy losses and enhancing overall system performance in protected agriculture, Torres et al. [32], developed an agricultural energy hub with 48 semitransparent PV panels and battery storage, achieving an average 41% saving and enabling electric vehicle charging, thereby turning the greenhouse into a resilient urban energy node.

Finally Bularka et al. [82] and Vavra et al. [83], they explored the technological frontier of spectral control and efficient lighting. Green and yellow dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC) exhibited superior thermal stability (γ = −0.0004%/°C), lowering the internal temperature by 3 °C and improving the thermal balance. In parallel, replacing high-pressure sodium lamps with white LEDs optimized the photosynthetic photon flux and reduced electrical consumption. These advances consolidate the role of spectral manipulation whether to generate electricity or to tune photosynthetically active radiation as an essential component of smart greenhouses, where energy efficiency and microclimatic comfort are managed through algorithmic precision and advanced materials

3.12. Intelligent IoT-Based Systems for Energy and Environmental Management of Photovoltaic Greenhouses: Advances Toward Near-Zero Energy Consumption

The Internet of Things (IoT) has become a cornerstone of digital and energy-sustainable agriculture by enabling real-time monitoring and control of climatic, energy, and agronomic variables. Its integration with photovoltaic (PV) systems and Artificial Intelligence (AI) has led to the development of smart greenhouses capable of operating with minimal dependence on the electrical grid, aligned with the concept of Near Zero Energy Greenhouses (NZEG). The synergy among IoT, machine learning, and renewable energies drives the creation of climate-resilient agricultural ecosystems, applicable to both arid and temperate regions, where adaptive decision making and autonomous energy management are essential.

Bouarroudj et al. [84], they present an integrated architecture that combines a distributed sensor network with machine learning modules for predictive diagnostics and energy control. Using the Isolation Forest algorithm, the system identifies anomalies in irradiance, electrical voltage, and irrigation flow with high accuracy (R2 > 0.90). It also integrates an autonomous PV subsystem with current and voltage tracking to ensure off-grid operation. The tests confirmed thermal and energy stability even under simulated faults, demonstrating the effectiveness of AI–IoT–solar energy fusion in self-sufficient agricultural platforms.

In a more advanced approach, Gao et al. [85], they applied deep reinforcement learningspecifically Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), to optimize heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and to balance PV generation with energy consumption. The algorithm, which combines physical models with machine learning (ML), minimized thermal losses and energy deviations, with results transferable to industrial greenhouses and plant factories with artificial lighting (PFAL). In contexts where precise regulation of temperature, humidity, and light is critical, this approach defines a new-generation agricultural energy management model based on intelligent control and adaptive efficiency.

In rural environments, Hamied et al. [30], they developed a low-cost IoT system (€73) for monitoring remote greenhouses in southern Algeria. The device measures current, voltage, irradiance, and solar cell temperature, incorporating fault diagnosis and SMS communication. Its energy consumption (13.5 Wh day−1) and autonomy demonstrate the feasibility of economical, open-source solutions for isolated areas, expanding access to solar monitoring technologies in protected agriculture. The review of Soussi et al. [8], offers a synthesis of strategies to reduce energy consumption in smart greenhouses, identifying challenges in heating, cooling, and lighting. The reviewed studies show reductions of 35–60% through the integration of renewable energies, advanced materials, and adaptive management algorithms, highlighting the role of IoT and AI in real-time microclimatic monitoring. This modular and scalable approach provides a solid framework for developing energy-sufficient and climate-resilient agricultural prototypes.

Finally, Benghanem et al. [86], they demonstrated the effectiveness of IoT in autonomous photovoltaic cooling systems in arid regions such as Medina (Saudi Arabia). The prototype, based on direct-current air conditioning, fans, water pumps, and environmental sensors powered by a PV array, maintained optimal microclimatic conditions without relying on fossil sources. This model of energy integration emerges as a viable alternative for the development of sustainable greenhouses in areas characterized by extreme heat and water scarcity, consolidating the vision of Near Zero Energy Greenhouses (NZEG) as a central pillar of future protected agriculture.

To strengthen the conceptual and empirical understanding of the synergy among IoT architectures, machine learning techniques, and renewable energy systems in controlled agriculture, Table 1 synthesizes representative studies that illustrate concrete implementations of climate-resilient, energy-aware smart greenhouse systems. These works provide evidence of how IoT sensing, ML-based decision models, and photovoltaic energy converge to enhance microclimate regulation, energy autonomy, and operational sustainability.

Table 1.

Key Studies Demonstrating Synergy Among IoT, Machine Learning, and Renewable Energy Systems in Controlled Agriculture.

Collectively, these studies highlight the growing technological maturity of intelligent, energy-aware greenhouse systems and reinforce the relevance of IoT-enabled architectures integrated with machine-learning algorithms and renewable energy sources. Empirical evidence confirms that these convergent technologies constitute a foundational pathway toward next-generation climate-resilient, near-zero-energy protected agriculture.

3.13. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Solar and Climate Management in Controlled Agriculture: Optimization, Prediction, and Predictive Sustainability

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its core subset, Machine Learning (ML), are reshaping the management of solar energy and microclimate in smart greenhouses by enabling autonomous optimization of environmental conditions, resource use, and energy efficiency. Through the integration of microclimatic, agronomic, and energy data, AI improves predictive capacity, regulates processes such as irrigation, ventilation, lighting, and solar drying, and strengthens the adaptive capacity of protected agriculture in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). When combined with photovoltaic (PV), thermal, and Internet of Things (IoT) systems, AI and ML support the transition toward low-carbon, resilient, and high-efficiency greenhouse production models.

Shahbaz et al. [52], applied AI-based multicriteria decision models including quantum theory, M-SWARA, MOORA, and pictorial fuzzy sets to prioritize renewable energy investments, identifying hybrid systems and PV greenhouses as the most sustainable alternatives (weights: 0.267 for cost; 0.266 for recycled materials). Similarly, Banluesapy et al. [33] developed a solar-powered smart irrigation system controlled through a Random Forest algorithm with 99.3% accuracy, achieving reductions of 50% in water and energy consumption, a 130% increase in water-use efficiency, and a 50% reduction in CO2 emissions. Yu et al. [66], validated a photoelectric drip irrigation system integrating AI and solar energy, improving both water and energy efficiency under greenhouse conditions.

In advanced monitoring and control, Touhami et al. [90], proposed a hybrid architecture based on wireless sensor networks (WSN), IoT, and renewable energies for hydroponic systems capable of automatically regulating pH, temperature, and water level. Maraveas [91], emphasized that despite notable productivity gains enabled by AI and IoT, barriers persist regarding technological cost, sensor accuracy, and adoption in the Global South. In parallel, commercial implementations from Blue River Technology and John Deere illustrate the growing feasibility of autonomous irrigation, pest control, and energy management systems, although long-term reliability and operational training remain critical challenges.

Relevant advances in solar-energy modeling have also been documented. Harrou et al. [39] synthesized eleven studies and highlighted that hybrid recurrent neural networks (RNN) and multilayer perceptrons (MLP) achieve correlations above 0.95 (RMSE = 0.19) for photovoltaic forecasting. Algorithms such as XGBoost, Random Forest, and Reinforcement Learning demonstrated robust performance in predicting irradiance and correcting partial shading, while the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) outperformed ARIMA and LSTM across multiscale forecasting tasks. Bezari et al. [35], developed an ANN (6–15–1) yielding correlations above 96% for irradiance estimation in greenhouses, offering valuable inputs for calibrating CFD simulations and adaptive solar-control systems.

In solar drying, Hoque et al. [92], demonstrated that the integration of remote sensing and AI reduces drying time by 25–30%, preserves up to 90% of nutritional content, and decreases energy consumption and emissions by 15–20%. IoT-blockchain architectures further improved traceability and reduced operational costs by 10–15%. ML-assisted optimization of materials also shows promise: Ali et al. [53] reported that a graphene-based K-structured solar absorber optimized through ML reached a spectral absorption above 97% (R2 = 0.996; RMSE = 3.2 × 10−5). For predictive maintenance, Iqbal et al. [93] combined electrical impedance spectroscopy with ML, achieving F1-scores of 0.975 for dust and microcrack detection and 0.856 for thermal variation identification.

In the same way, Choubey et al. [94] emphasized that combining phase change materials (PCMs) and nanoparticles increases thermal conductivity and reduces drying time, while algorithms such as RBF, MLP, ANN, and SVM provide accurate predictions of moisture loss and quality metrics (RMSE = 0.99 for temperature; 33.67 for dry mass), tripling the net benefit compared with traditional dryers. Saeidirad et al. [95] and Karaağaç et al. [38] confirmed that integrating AI with multicriteria decision techniques (TOPSIS) optimizes temperature, airflow, and humidity for high-value crops such as saffron and mushrooms. In a CPV/T solar system with nanostructured PCM (Al2O3–paraffin), the ANN–SVM approach achieved R2 > 0.9 and thermal/exergetic efficiencies of 20% and 8%, respectively.

ML and deep learning have also enhanced sensor communication and energy forecasting. Alturif et al. [55] integrated deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN) with Lagrangian optimization to reduce communication energy in climatic sensor networks. Venkatesan & Cho (2024) [96] showed that a Bi-LSTM model surpassed CNN, LSTM, and GRU architectures (R2 = 0.9243; RMSE = 0.0048) in forecasting solar energy consumption up to two weeks ahead. These advancements support dynamic load scheduling and optimized PV production under varying environmental conditions. In the control domain, Hu & You. [62] designed a robust model predictive control framework with AI (RMPC-AI) for photovoltaic-controlled environment agriculture (CEA-PV), improving energy efficiency by 15.4% and reducing water and light pollution by 8.7% and 3.6%, respectively. Venkateswaran & Cho. [59] proposed a hybrid SSA-CNN-LSTM model achieving MAE values of 0.1202 (hourly) and 0.1774 (daily), enhancing energy planning and load distribution in solar greenhouses.

Finally, the integration of energy, water, and emissions is exemplified by the EWMS system of Fiesta & Tria. [64], which uses an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) to forecast photovoltaic production and crop water requirements, increasing solar utilization by 94.3% and reducing grid consumption by 3.49 kWh. Khani et al. [65] optimized a solar polygeneration system with CO2 capture through Genetic Programming and RNA, reducing costs by 11.4% and environmental impact by 34.31%. Alsafasfeh et al. [36], implemented a spatial search neural algorithm that increased PV power output and outperformed conventional optimization methods. Together, these studies delineate the transition toward intelligent, predictive, and highly integrated protected agriculture systems, in which AI and ML constitute fundamental pillars of energy optimization, climate resilience, and sustainability.

3.14. Integration of Computational Intelligence and Solar Energy in Smart Greenhouses: Modeling, Control, and Agrivoltaic Sustainability

The integration of Computational Intelligence (CI) with solar thermal and photovoltaic systems (ST and PV) has redefined greenhouses as intelligent energy ecosystems. Agrivoltaic (Agri-PV) systems and advanced solar dryers are evolving toward self-sufficient infrastructures capable of combining electricity generation, thermal control, and algorithmic optimization from a perspective of sustainability and agro-environmental efficiency.

The work of Sharma et al. [49], constitutes a benchmark in the assessment of solar radiation, thermal conversion, and energy storage (TES), integrating solar thermal technologies (SHS, LHS, TCES) with machine learning (ML) and the Internet of Things (IoT). The study demonstrates that intelligent solar dryers achieve higher thermal efficiency and shorter drying times through gradient-boosted regression algorithms (GBRT), which outperform traditional methods in accuracy (R2, MAE, RMSE). Remote control of temperature, humidity, and airflow ensures the quality of the dried product and reduces electrical consumption, confirming the role of adaptive thermal modeling in postharvest preservation and energy efficiency.

Beniuga et al. [97], they proposed an optical-energy approach in Agri-PV systems using diverging lenses that disperse solar radiation, reducing direct irradiance and soil evaporation by up to 16 times without compromising photosynthesis. Kujawa et al. [98], developed a three-dimensional irradiance model based on ray tracing, with average deviations of 2.88%, capable of predicting the spatial and temporal distribution of light and optimizing the orientation of panels and sensors. This research consolidates high-precision light and energy diagnostic tools applicable to greenhouses with variable PV covers.

Hasan & Lubitz [99], evaluated a comprehensive solar greenhouse using MATLAB simulations, confirming the technical and economic viability of Agri-PV systems capable of balancing crop production and annual electricity generation. Complementarily, Nagarsheth et al. [100] and Jamshidi et al. [101] they applied Energy Management Systems (EMS) and Model Predictive Control (MPC) powered by Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), achieving over 50% reductions in energy consumption, stabilizing battery State of Charge (SOC), and maintaining system robustness under partial shading.

Climate control, Riahi et al. [29] validated a MIMO (Multi-Input Multi-Output) model with fuzzy control and asynchronous motors powered by PV modules, which regulated temperature and humidity with high experimental precision. For its part, Nikolić et al. (2025) [102], they combined PV energy with geothermal heat pumps (GSHP) by optimizing the azimuth angle (−8°) using simulations in EnergyPlus and GenOpt, achieving savings of 6626 kg CO2/year and a payback period of 8.63 years. Padilla et al. [103], they explored photovoltaic materials (silicon, CdTe, organic polymers) and thermochromic coverings with diurnal and nocturnal thermal variations of +20 °C and −5 °C, respectively, confirming their utility for stabilizing temperature and modulating the light spectrum without additional energy consumption.

Xu et al. [104] they reviewed the application of three-dimensional (3D) simulations and combined methodologies of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and Functional–Structural Plant Modeling (FSPM) to analyze, in an integrated way, airflow, thermal dynamics, and crop physiological response, laying the groundwork for agricultural digital twins. In a complementary approach, Yao et al. [70], they proposed a holistic PV–climate–crop model that integrates measurement, simulation, and machine learning, aimed at simultaneously optimizing productivity and energy efficiency.

Steren et al. [105] they introduced an ecosystem-based approach by demonstrating that transparent solar panels (TSP) can convert 1.3% of agricultural land into covered systems, contributing up to 7% of national electricity (case of Israel) and generating an added value of 864 USD/ha/year by combining electricity production with ecosystem services. Finally, Özdemir et al. [106], they experimentally validated a bifacial PV system with 33% roof coverage, achieving yields of 1211–1264 kWh/kWp/year. Although agricultural yields initially decreased by 26–32%, after shading optimization the yield penalty decreased to 15–18%, demonstrating the feasibility of achieving stable synergies between agricultural production and electricity generation

3.15. Limitations and Future Challenges

Despite the methodological robustness and the integration of bibliometric, thematic, and systematic analyses, this study presents inherent limitations associated with the nature of the databases and the search criteria employed. The exclusive reliance on Scopus as the primary source may restrict the inclusion of relevant literature published in regional databases or emerging, non-indexed journals particularly from Global South countries, where innovations in solar agriculture and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are still at early developmental stages. Likewise, dependence on author-provided metadata may introduce biases in keyword identification, partially affecting the accuracy of thematic clustering and co-occurrence analyses.

Another limitation is the temporal and methodological heterogeneity of the analyzed studies. The rapid evolution of photovoltaic, thermal, and AI technologies implies that many findings published over the last decade are now partially outdated relative to recent developments, such as intelligent PV/T hybrid models, deep reinforcement learning controllers, or machine learning–driven predictive diagnostic systems. This rapid technological shift hinders homogeneous comparisons and limits the feasibility of quantitative meta-analyses, as indicators of energy, thermal, and agronomic performance vary widely across studies and experimental conditions.

From a conceptual perspective, the review underscores the need to develop integrative models that simultaneously account for energy, water, and carbon fluxes in controlled agricultural systems. Most studies address only one or two subsystems, such as energy and microclimate, or water and irrigation, without capturing ecological interdependencies or the synergistic dynamics inherent to complex agricultural environments. The absence of standardized metrics for energy, exergy, and economic efficiency further constrains global comparability and hampers the formulation of technical standards applicable across production scales.

Looking ahead, future challenges point toward the consolidation of digital and self-sufficient protected agriculture systems in which AI, the Internet of Things (IoT), and renewable energies operate synergistically. Achieving this vision will require strengthening open-data infrastructures, incorporating cross-validation methodologies between simulations and field measurements, and fostering international collaborations that connect regions of high solar irradiance with those facing significant climate vulnerability. The development of agricultural digital twins, multicriteria predictive models, and adaptive learning–based energy control systems represent the next technological frontier for achieving intelligent, decarbonized, and climate-resilient agriculture.

3.16. Perspectives and Research Trends

The bibliometric and thematic analysis results reveal a transition of the field from fragmented technological approaches toward an interdisciplinary knowledge ecosystem that integrates solar energy, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and agricultural sustainability. The identified motor clusters focused on solar dryers, renewable energy resources, particle swarm optimization (PSO), and controllers indicate that future research will tend to integrate thermal modeling, adaptive control, and evolutionary optimization under intelligent architectures. These lines will not only enhance the energy efficiency of agricultural systems but also promote operational autonomy through predictive maintenance strategies and algorithmic microclimate management. The maturity of these topics suggests that upcoming advances will focus on the complete automation of agricultural processes powered by renewable energy sources.

The multiple correspondence analysis confirmed a convergence trend among the domains of machine learning, energy efficiency, and photovoltaic systems, which are organized around sustainability as a transversal axis. This synergy anticipates a future in which AI models will not only serve as control or prediction tools but as decision-making agents capable of integrally managing energy, water, and plant production. The expansion of the sustainability axis reflected in the terms decision making and desalination, indicates that research will increasingly incorporate circular economy criteria, life cycle assessment (LCA), and energy balance, thereby strengthening the environmental and social dimensions of protected agriculture. This paradigm shift marks the evolution of the field toward intelligent systems that are resilient and low in climate impact.

From a methodological standpoint, research combining advanced simulation, three-dimensional modeling (CFD, BIM, FSPM), and agricultural digital twins is expected to grow. These approaches will enable the dynamic representation of interactions among solar radiation, microclimate, and plant physiology, generating cross-validation models between empirical data and algorithmic predictions. The future design of photovoltaic greenhouses and agrivoltaics systems will be oriented toward climatic customization and the topological optimization of smart covers, using evolutionary algorithms and deep reinforcement learning to adjust energy and mass flows in real time. In this way, AI will be consolidated as the operational core of controlled agriculture platforms, capable of learning, predicting, and adapting to variable environmental conditions.

Finally, the findings suggest that future research should focus on the systemic integration of Artificial Intelligence with emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), satellite remote sensing, and blockchain. The creation of interconnected networks of intelligent solar greenhouses and dryers, capable of sharing energy, climatic, and production data in real time, will shape a new paradigm of networked energy agriculture. This scenario will open opportunities for global scientific cooperation, technological transfer, and the development of green innovation policies. Overall, the field’s outlook points toward intelligent solar agriculture, supported by hybrid AI and renewable energy models that advance simultaneously toward efficiency, decarbonization, and food sovereignty.

4. Conclusions

The bibliometric analysis confirms a rapid consolidation of the field, with scientific output increasing from 3 publications in 2020 to 27 in 2025, and a total corpus of 79 studies included in this review. Engineering (55 documents), Computer Science (29), and Energy (19) emerged as the dominant subject areas, while China (11 publications) and the United Kingdom (5) led global contributions. Keyword co-occurrence revealed “solar energy” and “solar power generation” as the most frequent terms (10 occurrences each), underscoring the centrality of energy optimization and AI-driven modeling. These indicators demonstrate that AI-assisted solar systems in protected agriculture have reached an important stage of scientific maturity and thematic coherence.

From a systematic perspective, the reviewed studies show that the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Internet of Things (IoT) with photovoltaic and thermal technologies enables intelligent greenhouses and solar dryers capable of reducing energy consumption by more than 50%, stabilizing microclimatic conditions, and optimizing water use. Hybrid PV/T systems, predictive control architectures, and phase change materials (PCMs) currently constitute the core technological pathways toward near-zero-energy protected agriculture.

However, the synthesis of evidence reveals several research gaps that must be addressed. First, most studies rely on small-scale prototypes or controlled experimental setups, leaving a limited understanding of system performance under real production conditions. Second, there is a lack of standardized metrics for evaluating energy, water, and carbon efficiency across heterogeneous greenhouse designs. Third, the integration of AI models with physical modeling tools such as CFD simulations, digital twins, and multi-energy management frameworks remains incipient, indicating a methodological gap in harmonizing data-driven and physics-based approaches. Finally, social, economic, and policy dimensions of AI solar technologies in agriculture are still underexplored, particularly in regions of the Global South where adoption barriers persist.

Based on these gaps, several research directions emerge. Future work should prioritize (i) large-scale validation of AI–solar systems in commercial greenhouses, (ii) development of unified performance indicators for energy–water–carbon optimization, (iii) integration of CFD, digital twins, and real-time predictive control into unified operational platforms, and (iv) techno-economic and life-cycle assessments that evaluate long-term sustainability and replicability. Additionally, expanding research in Latin America and Africa is essential to ensure equitable access to climate-resilient and low-carbon production systems.

Overall, this review demonstrates that the convergence of AI, ML, IoT, and solar energy is shaping a new generation of autonomous and sustainable agricultural ecosystems. By articulating global trends, technological advances, and future research needs, this work provides a comprehensive framework that supports the design of next-generation agrivoltaic and solar-assisted systems aimed at improving productivity, resource efficiency, and climate resilience in protected agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/technologies13120574/s1, PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; methodology, E.V.; software E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; validation, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; formal analysis E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; investigation E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; resources, E.V.; data curation, E.V.; writing—original draft preparation, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; writing—review and editing, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; visualization, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; supervision, E.V. and J.R.; project administration, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R.; funding acquisition, E.V., J.J.E., F.A.V., A.S., D.A.S.V. and J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained in the article. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria—AGROSAVIA and for their technical support in carrying out this research. This study is a review article developed by the authors’ own initiative, but its information does not include topics associated with food products specific to any of the corporation’s research projects.

Conflicts of Interest

Author John Javier Espitia, Fabian Velasquez, Diego Alejandro Salinas Velandia, Andres sarmiento, Jader Rodriguez and Edwin Villagran were employed by the company Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| Bi-LSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| TFT | Temporal Fusion Transformer |