Abstract

The rotor is a crucial component in rotating machinery, where its stability directly impacts performance and safety. Imbalance-induced vibrations can cause severe component wear, resonance instability, and even catastrophic failures, especially in high-speed systems like aero-engines. While the squeeze film damper (SFD) is widely used for vibration suppression, the effects of imbalance (manifested as SFD eccentricity) on its dynamic performance are not well understood. Additionally, the combined impact of imbalance and acceleration on rotor–SFD system stability has not been systematically investigated. This study uses numerical simulations to explore the influence of SFD eccentricity, caused by imbalance, on its dynamic characteristics. Experimental tests are conducted to examine the effects of imbalance and acceleration on rotor–SFD dynamics. Results show that increasing imbalance raises SFD eccentricity, reducing the effective oil film bearing area. This results in a rapid increase in the oil film’s stiffness and slower growth in damping, enhancing nonlinearity and reducing stability. Under small imbalance conditions, increasing acceleration improves stability by facilitating critical speed crossing and reducing vibration amplitude. However, excessive imbalance renders acceleration control ineffective, exacerbating system instability. This study provides valuable insights into the interaction between imbalance, acceleration, and SFD performance, offering guidance for optimizing rotor–SFD system parameters and ensuring stable operation.

1. Introduction

Rotating machinery, as core equipment in national strategic fields such as aerospace, energy, and rail transportation, has its operational reliability directly influencing the safety and efficiency of the upstream and downstream industries. The rotor, as the power center of rotating machinery, is the key component responsible for energy conversion and motion transmission. From the high-pressure rotors of jet engines to the main shaft rotors of steam turbines, the dynamic performance (vibration characteristics, stability) of these components not only determines the operational precision and service life of the entire system but also directly impacts the equipment’s adaptability to extreme working conditions (such as high temperature, high speed, and heavy load environments). However, the rotor is highly susceptible to imbalance due to factors such as manufacturing errors, operational wear, and external impacts. At high rotational speeds, this imbalance can induce periodic vibrations that coincide with the rotor speed. These vibrations not only accelerate wear on critical components like bearings and seals, but also may lead to catastrophic failures, such as rotor–stator contact, shaft bending, or even system shutdowns and accidents. This issue becomes a core bottleneck in the development of rotating machinery towards higher speeds, lighter structures, and improved efficiency. To suppress imbalance vibrations, the squeeze film damper (SFD) has become one of the most widely used vibration reduction components in high-speed rotor systems, due to its unique working principle of energy dissipation through oil film compression. When the rotor vibrates, the oil film within the damper clearance undergoes compression deformation, converting the vibrational mechanical energy into heat energy dissipated by the oil. This process can reduce vibration amplitude by more than 50% within the rotor’s resonance range, significantly expanding the stable operating speed range of the rotor. Especially in high-end equipment such as aero engines and gas turbines, the SFD has become a critical support for ensuring low vibration operation of rotor systems. The variation in acceleration during the rotor operation directly affects the pressure distribution, dynamic stiffness, and damping characteristics of the SFD, thereby impacting the damping efficiency of the SFD. Additionally, transient fluctuations in acceleration alter the centrifugal force distribution and critical speed characteristics of the rotor, significantly affecting the stability of the rotor system. The academic community has conducted in-depth research on the dynamic characteristics of SFDs, imbalance control, and the rotor–SFD system dynamics.

Research on SFDs mainly focuses on three aspects: vibration damping mechanisms [1,2,3], the influence of various parameters [4,5], and new types of SFDs [6,7]. Lee et al. [8] conducted a study using CFD and theoretical analysis to investigate the effects of piston ring clearances, oil grooves, and oil supply ports on the characteristics of the SFD. They proposed a method to quickly assess the impact of the oil chamber geometry on SFD performance through an equivalent clearance. Koo et al. [9] presented a volume of fluid (VOF) model for a piston-ring sealed-end SFD exposed to ambient air (rather than submerged in lubricant and susceptible to air entrainment). Their model provides predictions that are validated against experimental results obtained from a dedicated test rig. Anchored by the test data, the physical model effectively addresses a critical challenge in SFD design and operation: quantifying the amount of air ingested and its impact on the damper’s forced performance. Gheller et al. [10] examines a large-clearance SFD with two inlet flow rates under both single- and multifrequency excitations. The study suggests that the damping extracted from the secondary frequency excitations is primarily influenced by the large squeeze velocities resulting from combined excitations, rather than by the effects of air ingestion. Zhang et al. [11] consider a flexible rotor system supported by SFDs and propose a novel multi-objective optimal design method for the squirrel cage, taking into account the reliability of the squirrel cage, the stability of the rotor system, the dynamic response of the rotor, and the damping effect of the SFDs. The method is further validated through experimental testing. Heidari et al. [12] proposed a novel SFD that, by adjusting appropriate parameters, reduces rotor vibrations and transmitted forces. Compared to traditional SFDs, it offers better vibration control for the rotor system. Hang et al. [13] propose an innovative hybrid approach that integrates a physical model with machine learning (ML) techniques to diagnose multi-faults, such as imbalances and shaft bowing, in a Jeffcott rotor. Nan et al. [14] investigates the bending–torsion coupled vibrations of a rotor system with imbalance and oil-film bearings, focusing on the effects of rotor speed, eccentricity, and initial eccentric phase difference on nonlinear vibrations. Ment et al. [15] presents a wearable vibration sensing technique for on-shaft monitoring of rotors, including theoretical modeling of imbalance, development of a wirelessly powered MEMS-based sensor, and in-sensor computing for optimized data transmission, with successful validation on a rotor test rig. Salem et al. [16] develops a machine learning-based vibration analysis system using a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network for real-time rotor imbalance detection, integrating MEMS sensors, noise reduction, feature extraction, and optimized MLP architecture, validated with 800 experimental samples under controlled flight conditions.

Research on imbalance is divided into two parts: imbalance diagnosis [17,18] and imbalance suppression [19,20]. Han et al. [21], inspired by transfer learning, proposed a transfer learning method that combines dynamic model simulations and experimental data for flexible rotor imbalance fault localization. This method achieves cross-domain deep transfer recognition of the rotor imbalance position. Wu [22] proposes an imbalance prediction method based on a Genetic Algorithm Back Propagation (GA-BP) neural network and Deep Belief Networks (DBN), which significantly reduces the measurement errors of rotor imbalance. Zhou et al. [23] proposed an online imbalance compensation algorithm using active magnetic bearings (AMBs), based on the Least Mean Squares (LMS) method and the Influence Coefficient Method (ICM). The effectiveness of the algorithm was validated through an online imbalance compensation experiment on a maglev rotor. Zhang et al. [24] proposed an SP-based suppression method for the imbalanced vibration of a rotor with multiple 1X faults. The effectiveness of the proposed method was validated by comparing its balancing effects with those of the traditional method on a rotor test platform. Li et al. [25] combined the fault detection analysis strategy with order tracking analysis and power spectral density methods, detecting imbalance faults by analyzing pneumatic torque. Wu et al. [26] proposed a no-speed order tracking method based on the STFTSC algorithm, which develops the STFTSC algorithm by combining the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and the Seam Carving algorithm. Askari et al. [27] investigated how torsional load affects two vibration-based imbalance fault indicators, demonstrating the load independence of the fundamental rotational harmonic intensity and the validity of the new speed-invariant imbalance feature. Xu et al. [28] proposed a simple and effective rotor imbalance detection and quantification method. They presented a vibration model that describes rotor imbalance under blade cracking conditions. Salah et al. [29] investigated the effectiveness limits of stator current spectrum techniques compared to classical vibration methods for monitoring mechanical imbalance in motors under actual load driving conditions, revealing inherent mechanical imbalances. Suri [30] compared the vibration and motor current signals of induction motors under different levels of torque, imbalance, and misalignment, as well as load-induced air gap eccentricity faults. Experiments were conducted on intentionally faulty motors with varying degrees of static air gap eccentricity. Askari et al. [31] investigated this dependency and proposed a new imbalance diagnostic feature, along with a novel simplified version, both independent of shaft speed. They studied an equivalent mass-spring-damper system to find a closed-form expression describing this dependency. By normalizing the obtained dependency against conventional imbalance diagnostic features, they proposed a new diagnostic characteristic. Askari et al. [32] investigated the impact of torsional load on vibration-based imbalance fault diagnostic techniques under varying speed conditions. They derived coupled bending–torsional nonstationary motion control equations and solved them numerically.

The study on the dynamic characteristics of the rotor–SFD system focuses on the vibration reduction effects of the SFD on the rotor [33,34,35], the coupling interaction between the SFD and the rotor [36,37], as well as the nonlinear characteristics of the rotor system [38,39,40]. Zheng et al. [41] proposed an effective numerical method for calculating the imbalance response of the rotor–SFD system, based on experimental and numerical analysis. This method can effectively predict the imbalance response of the rotor system. Chen et al. [42] studied the dynamic characteristics of the SFD-rotor system considering fluid inertia and developed a flexible method to calculate the dynamic behavior of the SFD-rotor system, taking into account the oil film inertia under base motion. Chen et al. [43] studied the bifurcation behavior of a rigid rotor–SFD system considering the effects of fluid inertia. The theoretical analysis was validated by comparing the simulation results with the theoretical results. Pan et al. [44] developed a general rotor system model that considers strong nonlinear factors and studied the dynamic response of the rotor system under different friction impact stiffness, oil film clearance, and bearing clearance. Dong et al. [45] established a finite element model of the rotor–SFD system and investigated the effects of different oil film clearances and support restoring force coefficients on the rotor response. They revealed that the nonlinear oil film force of the SFD primarily affects the vibration amplitude, while the nonlinear restoring force of the support affects both the vibration amplitude and frequency.

In the fields of rotor dynamics and vibration control technology, there has been extensive research on SFDs, rotor imbalance, and the dynamic response of rotor systems. These studies have established a mature theoretical framework, covering the mechanical models of SFDs, imbalance prediction, suppression methods, and stability analysis of rotor systems, which provide essential technical support for the vibration mitigation design of high-speed rotating machinery such as aircraft engines and gas turbines. However, there are still some aspects that have not been sufficiently explored in existing research: On one hand, the coupled effects of imbalance and the working conditions of SFDs have not been thoroughly analyzed. In particular, the specific mechanisms by which imbalance alters the oil film distribution, thus affecting the stiffness and damping characteristics of the SFD, and ultimately influencing the stability of the rotor system, remain unclear. On the other hand, research on the critical operating parameter of acceleration has been limited. Most studies assume that the rotor operates under stable acceleration or constant speed conditions, failing to fully account for the dynamic variations in acceleration in real-world scenarios. Therefore, the effect of acceleration on the dynamic characteristics of the rotor and its role in regulating the suppression effect of imbalance excitation remain unknown. This study combines numerical simulations and experimental validation: the numerical simulations analyze the impact of eccentricity (which indirectly represents imbalance) on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD, including oil film pressure, stiffness, and damping coefficients. Based on these simulation results, experimental research quantifies the synergistic effects of imbalance and acceleration, revealing their role in regulating the dynamic response and stability of the rotor–SFD system.

2. Establishment and Validation of the Dynamic Model

Classical lubrication theory analyzes the damping characteristics of the SFD based on the Reynolds equation, but it neglects the effects of fluid inertia. With the increase in engine speed and the use of low-viscosity lubricants, the Reynolds number of the oil film increases significantly, making the influence of fluid inertia on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD non-negligible. This paper, based on the method of the Energy Approximations [46], introduces the effect of fluid inertia into the classical Reynolds equation and derives the SFD force model considering inertial forces.

where Re is the Reynolds number, ρ is the lubricating oil density, ω is the journal whirl frequency, c is the damper clearance, and μ is the lubricating oil viscosity.

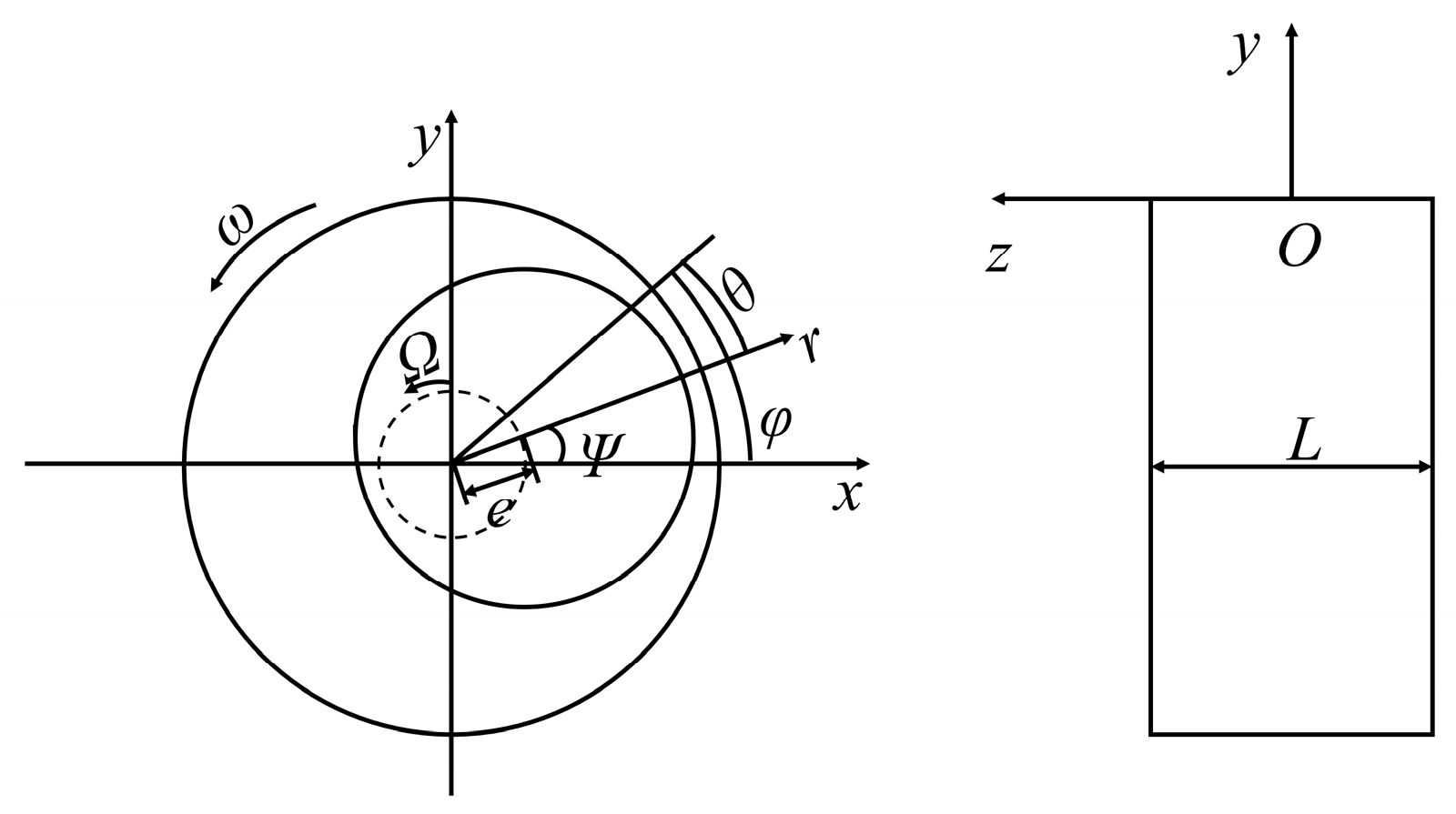

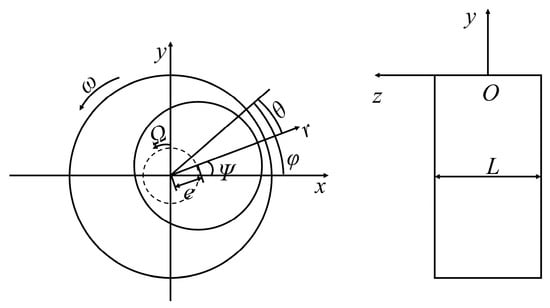

For a rotor system with SFD, the damping properties of the oil film are crucial. Bearing 1 utilizes a combination elastic supporting structure comprising an SFD, a squirrel cage, and a rolling bearing, while bearing 2 adopts a rigid supporting structure with a ball bearing. Figure 1 displays the schematic of the SFD.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the SFD.

The SFD consists of the journal and bearing sleeve, and when the oil film clearance c ≪ journal radius R, the annular oil film can be unwrapped into a plane clearance flow. The expression for the oil film thickness is as follows:

where e is the journal eccentricity and θ is the circumferential angle. The flow assumptions include:

- Laminar flow, incompressible.

- Pressure is uniform along the oil film thickness (Y-direction) (∂p/ ∂Y = 0)

- The velocity variation in the Y-direction is much greater than the variation in the circumferential (X) and axial (Z) directions.

After neglecting the inertial terms, the momentum equations for the fluid in the X and Z directions are simplified to:

where u and w represent the velocities in the X and Z directions, respectively, and p is the pressure in the oil film. Considering the boundary conditions (Y = 0, u = w = 0; Y = h, u = U w = 0, U is the shaft circumference velocity), integrating Equations (3) and (4) yields the velocity distribution:

The continuity equation is

where v is the velocity in the Y-direction. Integrating Equation (7) along Y and applying the boundary conditions for v (Y = 0, v = 0; Y = h, v = h′, h′ is the oil film thickness), we obtain the classical inertial-free Reynolds equation.

Research [47] as shown that even as the Reynolds number increases, the oil film velocity profile differs very little from the classical inertial-free solution. Therefore, the velocity distribution from Equations (5) and (6) is used to calculate the fluid’s inertial effects.

The kinetic coenergy T* is defined as

where V is the volume of the oil film. For short bearings (axial flow dominant, u ≪ w), u and v are neglected. Substituting w from Equation (6) and integrating, combining h = c − ecos θ and the eccentricity ratio ϵ = c/e, the result is

where Ω is the angular velocity of the journal; mrr, mtt, and mrt are the inertia coefficients, and their expressions are

where R is the journal radius, L is the bearing length, and θ1, θ2 represent the range of the oil film.

According to the Lagrange equation, the inertial force is the derivative of the kinetic coenergy with respect to the velocity. The radial inertial force Fi,r and the tangential inertial force Fi,t are, respectively,

Substituting Equation (10),

The damping force is obtained by integrating the classical Reynolds equation.

In the equation, Crr, Ctt and Crt are the damping coefficients (Crt = Ctr). The expression for the damping coefficient is

Combining the inertial force Equations (16) and (17), the total force of SFD is

The equivalent stiffness K and equivalent damping C of the SFD are

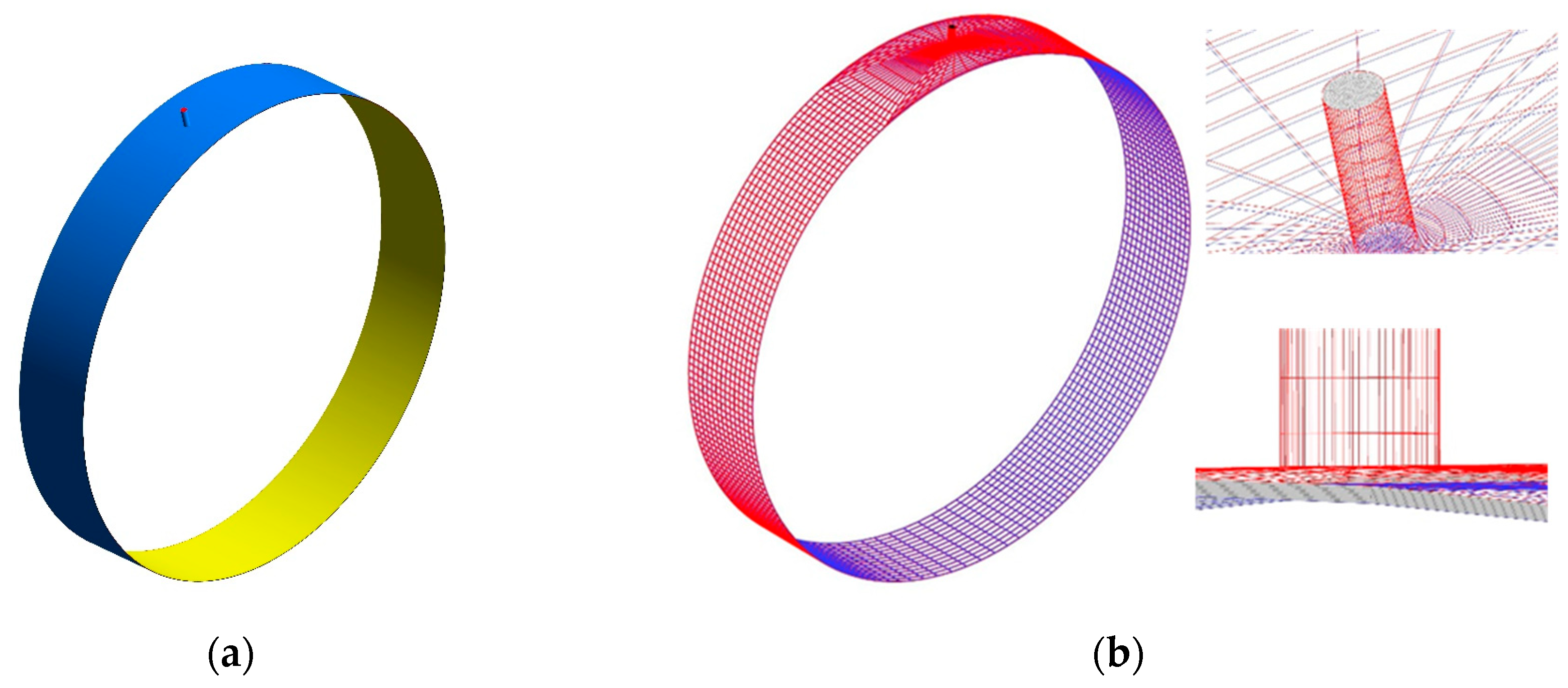

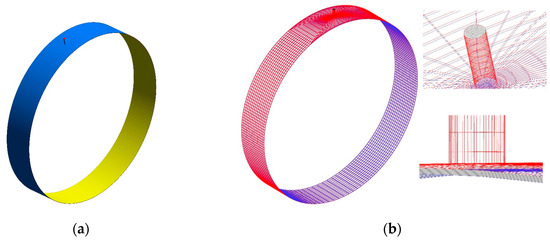

The numerical simulation results are validated based on the experimental data from reference [48]. Table 1 lists the SFD structural parameters. A dynamic model of the SFD was developed, and numerical simulations were conducted to investigate its performance. The geometric model and mesh discretization of the SFD are depicted in Figure 2. Given the relatively low Reynolds number in the SFD, laminar flow conditions were assumed for the analysis. The boundary condition for the SFD surface was specified as a “wall,” while the shaft motion was modeled using a combination of User-Defined Functions and dynamic mesh techniques to simulate vortex dynamics. The gaps on both sides of the SFD were treated as pressure outlet boundary conditions, with the pressure set to atmospheric pressure. The lubrication oil inlet was treated as a pressure inlet boundary condition, with the pressure at the inlet specified based on the actual operating conditions of the system.

Table 1.

SFD structural parameters.

Figure 2.

The geometric model and grid division of the SFD. (a) geometric model; (b) mesh discretization.

Table 2 illustrates the comparison between the numerical simulation and experimental results of the SFD. Since the error is less than 5%, the numerical simulation method proposed in this study is considered to be reliable.

Table 2.

Comparison between the numerical simulation and experimental results.

3. Test Rig Introduction

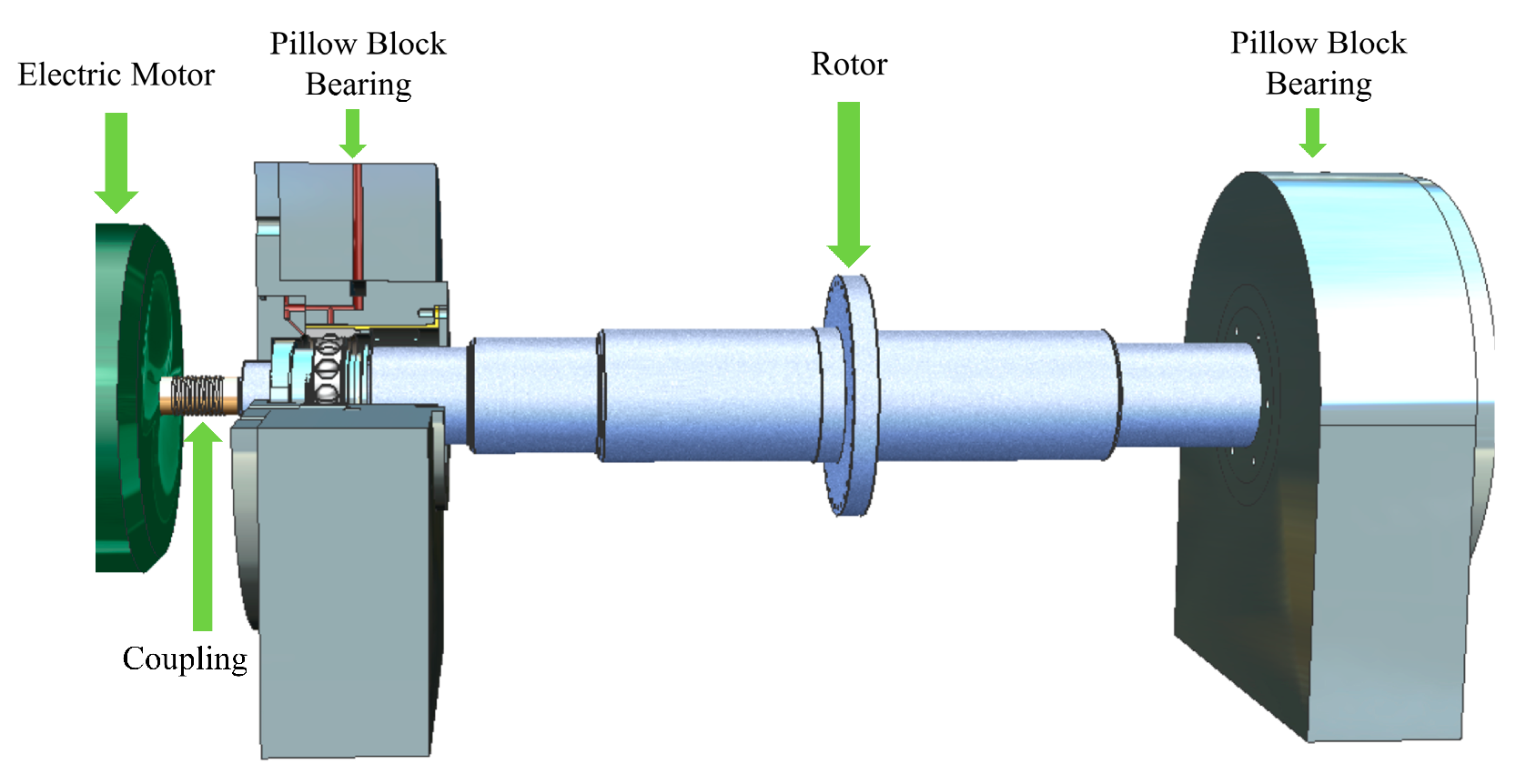

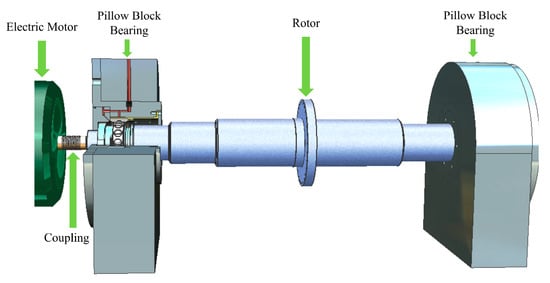

The schematic diagram of the test rig is shown in Figure 3. On the left side, there is an elastic support with the SFD, while the right side is equipped with a rigid support. The total length of the rotor shaft is 800 mm, with the rotor disc positioned at the center, having a diameter of 160 mm.

Figure 3.

Description of the test rig.

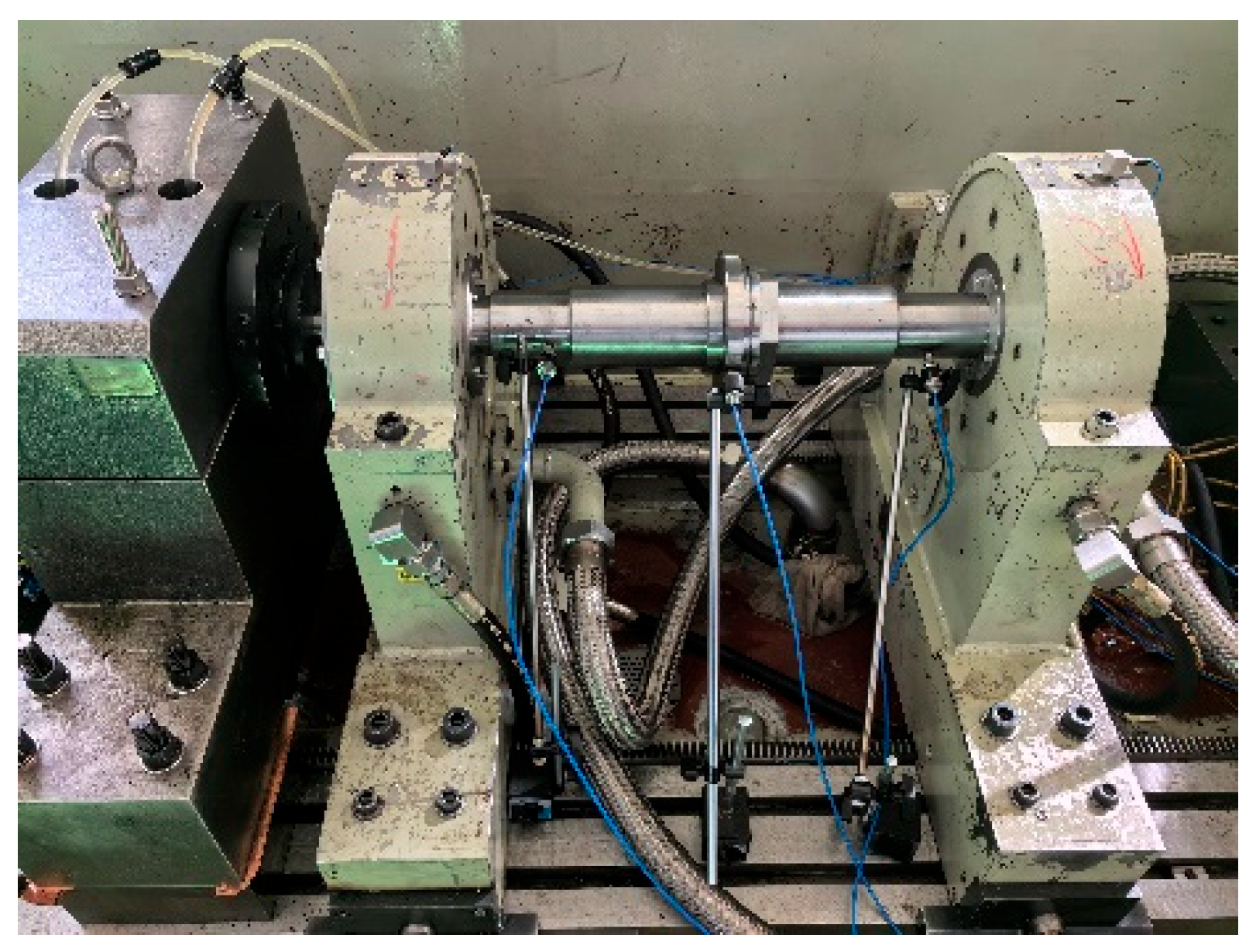

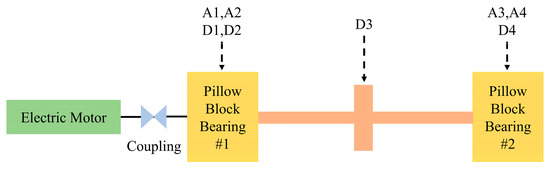

The transient dynamics testing setup includes 4 accelerometers and 4 eddy current sensors for detection. The arrangement of sensor is as shown in Figure 4. A1–A4 are accelerometer sensors utilized for detecting vibration acceleration signals in the horizontal and vertical directions of the two bearing pedestals. D1–D4 are displacement sensors employed to monitor the vibrational displacement of the front and rear bearing pedestals, along with the disc. Where D1 monitors the horizontal displacement of support 1, and D2 monitors the vertical displacement of support 1. Figure 5. depicts the transient dynamics test rig.

Figure 4.

The arrangement of the sensor for the rotor dynamics experiment.

Figure 5.

The transient dynamics test rig.

4. The Critical Speeds

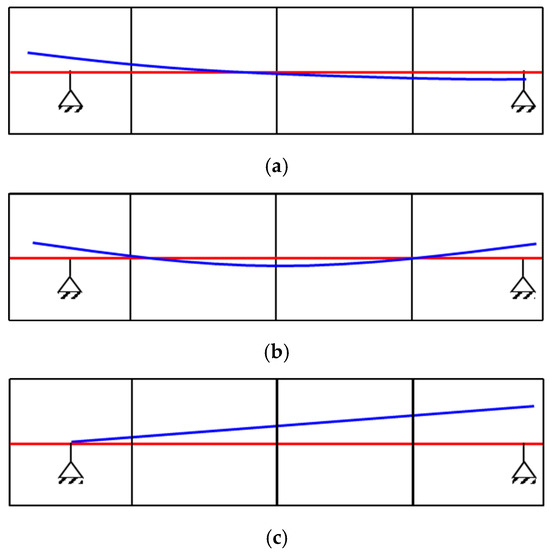

In this model, the shaft has a length of 800 mm and a maximum diameter of 88 mm. The disk has a diameter of 160 mm. Bearing 1 is an elastic support, with a stiffness value of 5 × 106 N·m−1, while Bearing 2 is a rigid support, characterized by a stiffness of 1 × 108 N·m−1. The computed results for the first three critical speeds and mode shapes of the rotor–SFD system are shown in Figure 6. The first critical speed is 109.14 (Hz); the second critical speed is 256 (Hz); and finally, the third critical speed is 1067 (Hz).

Figure 6.

The first three critical speeds and mode shapes of the rotor–SFD system. (a) First order critical speed; (b) Second critical speed; (c) Third order critical speed.

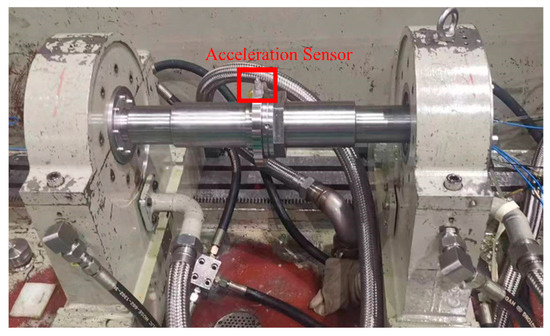

Modal testing was conducted on the rotor system to determine the critical speed, and the experimental setup for the modal dynamics tests is illustrated in Figure 7. An accelerometer was used for measurement, while a modal hammer was employed as the excitation tool.

Figure 7.

Experimental setup of the mounted modal dynamic testing.

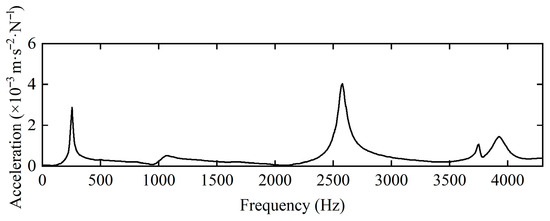

Figure 8 presents the transfer function results from the modal rotor dynamics test. As the modal test results are influenced by the location and direction of excitation, the first critical speed was not excited during the experiment. However, from the modal test data, it is evident that the second critical speed occurs at 252 Hz. The error between the second-order critical speed obtained from numerical calculation and that from the modal test is 1.5%, indicating that the numerical simulation is reasonable.

Figure 8.

Exponential form of the transfer function curves for the modal tests.

5. Effect of Imbalance

5.1. Numerical Simulation of SFD

The centrifugal force generated by the imbalance of the rotor system forces the rotor to deviate from its geometric center, which leads to an increase in the eccentricity of the SFD, the ratio of the center of the SFD to the axis of the bearing journal. At low precession frequencies or under static conditions, the eccentricity is approximately linearly related to the imbalance. Therefore, this paper indirectly investigates the effect of imbalance on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD by studying the influence of eccentricity on its dynamic behavior.

To investigate the effect of eccentricity on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD, this paper establishes dynamic models of the SFD with eccentricities of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 for numerical simulation.

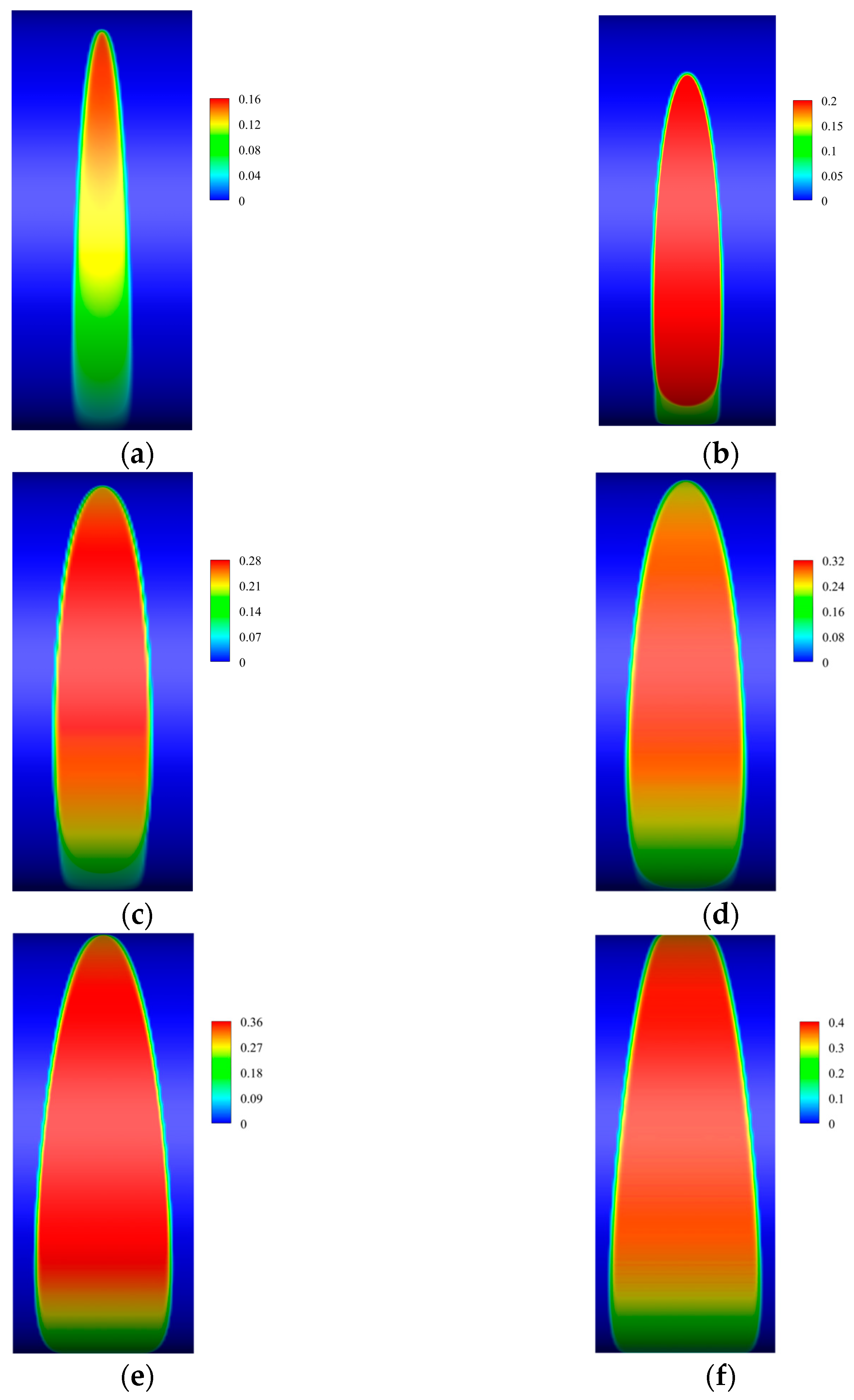

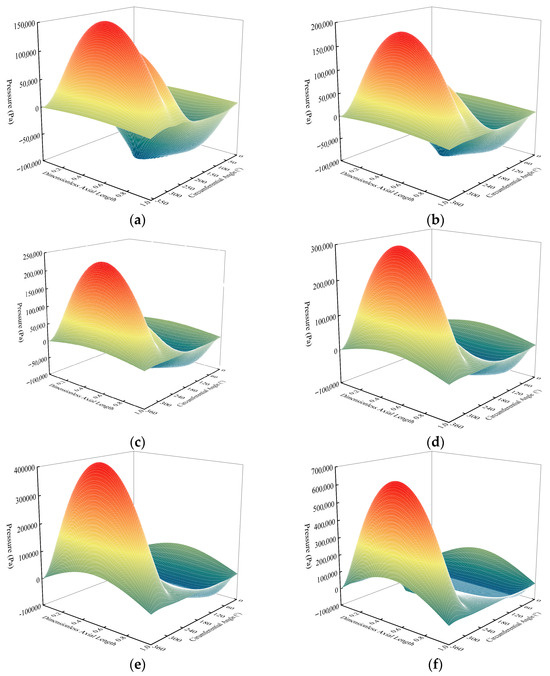

Figure 9 shows the pressure distribution of the oil film under different eccentricities. Due to the presence of the oil supply holes, the continuity of the pressure distribution under ideal conditions is disrupted, causing noticeable fluctuations in the pressure curve in some regions. Due to the constraints of the flow boundary conditions, the negative pressure zone reaches a maximum value of −100,000 Pa.

Figure 9.

The effect of eccentricity on the pressure distribution of the oil film. (a) ε = 0.1; (b) ε = 0.2; (c) ε = 0.3; (d) ε = 0.4; (e) ε = 0.5; (f) ε = 0.6.

As the eccentricity increases, the difference in oil film thickness distribution becomes more pronounced, enhancing the oil squeeze effect. The amplitude of the positive pressure region increases rapidly. When the eccentricity is at a low level, the maximum pressure in the positive pressure region is approximately 150,000 Pa. As the eccentricity continues to increase, the pressure amplitude in the positive pressure region gradually rises, eventually reaching 700,000 Pa. As the eccentricity increases, the effective bearing area of the oil film decreases. Under low eccentricity conditions, the positive pressure region covers a wide angular range, roughly between 180° and 360°. As the eccentricity increases, the positive pressure region gradually contracts toward the high-pressure zone, and ultimately, its coverage angle range shrinks to between 300° and 360°.

The two-phase flow effects of the SFD include cavitation and air ingestion. The cavitation primarily arises from the dynamic variation in the oil film pressure: when the oil film pressure reaches the saturated vapor pressure of the lubricant at the current temperature, it causes the dissolved gases in the lubricant to precipitate or the lubricant to vaporize, forming dispersed bubbles or continuous gas phase regions. These gas-phase substances can disrupt the continuity of the oil film, leading to nonlinear fluctuations in the equivalent stiffness and damping of the oil film. Additionally, when bubbles collapse in the high-pressure region, they may cause microdamage to the inner walls of the damper. Air ingestion is more related to the structural design and sealing performance of the damper: if the damper end cap is poorly sealed, there is a negative pressure area in the oil supply system, or if air in the gaps is not completely expelled during assembly, external air can enter the oil film through sealing gaps, oil supply channels, etc., forming free air bubbles. Although these air bubbles are not generated by the vaporization of the oil like cavitation, they still occupy the effective oil film space, obstructing the normal squeezing and shear flow of the oil. This exacerbates the distortion of the oil film pressure field and further weakens the damping effect of the damper.

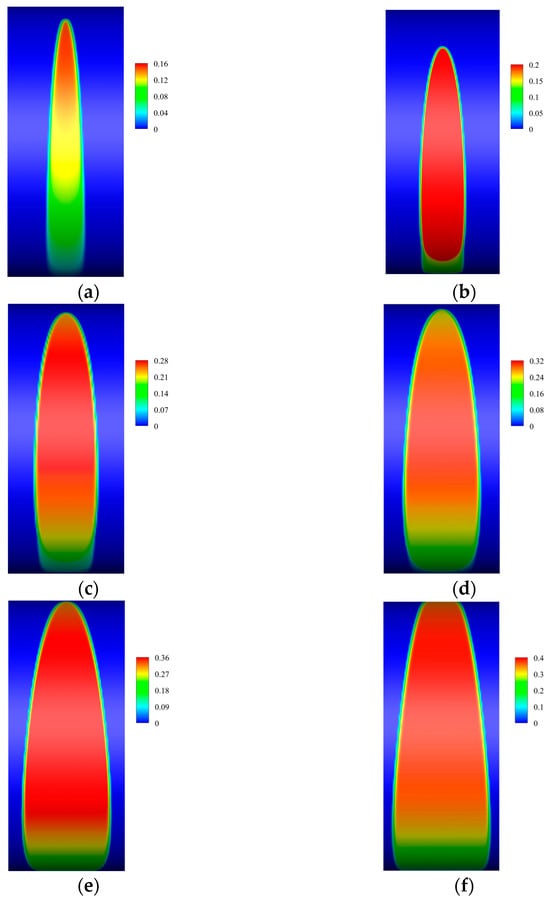

Figure 10 shows the volume ratio of the gas phase in the oil film at different eccentricities. As the eccentricity increases, the amplitude of the oil film pressure increases, the cavitation effect intensifies, and the volume ratio of the gas phase in the oil film increases rapidly. Under conditions with a lower eccentricity, the maximum volume ratio of the gas phase in the oil film is approximately 0.16. However, as the eccentricity continues to increase, the maximum volume ratio of the gas phase gradually rises to 0.4. At the same time, as the eccentricity increases, the uneven distribution of the oil film thickness intensifies. The oil film thickness in certain local areas decreases sharply, and the gas phase range expands rapidly. This is one of the reasons for the reduction in the range of the positive pressure zone.

Figure 10.

The effect of eccentricity on the gas phase volume fraction. (a) ε = 0.1; (b) ε = 0.2; (c) ε = 0.3; (d) ε = 0.4; (e) ε = 0.5; (f) ε = 0.6.

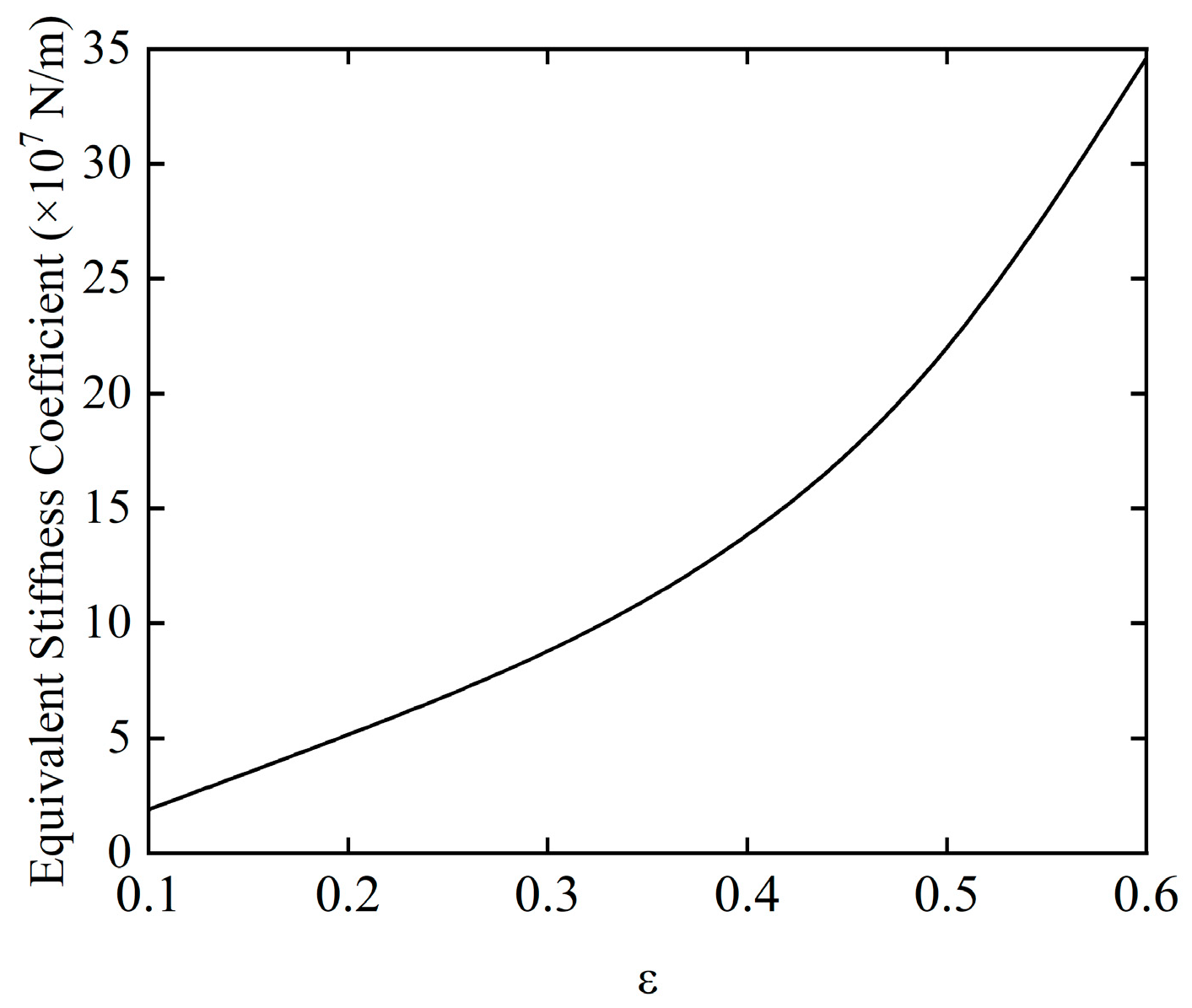

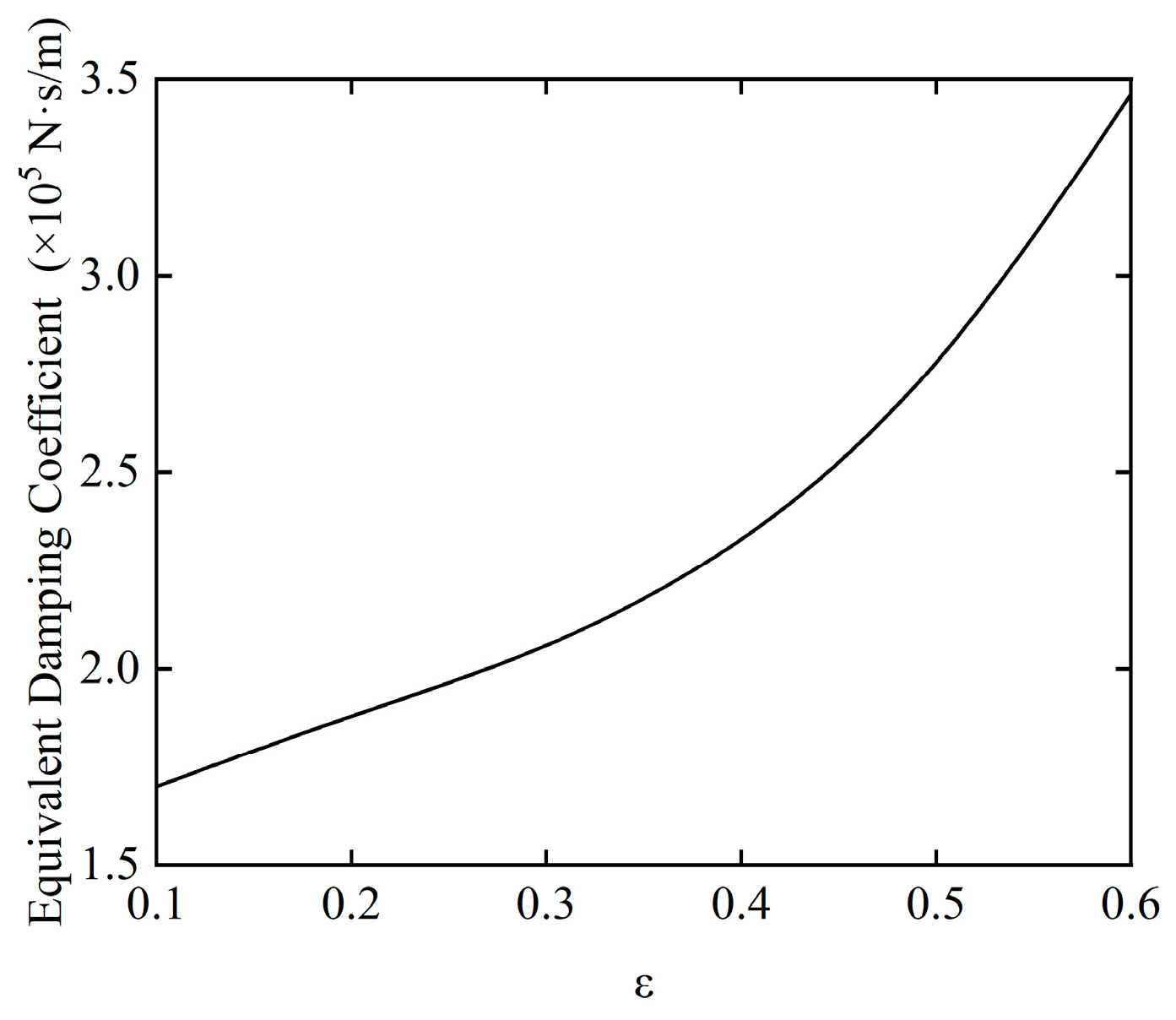

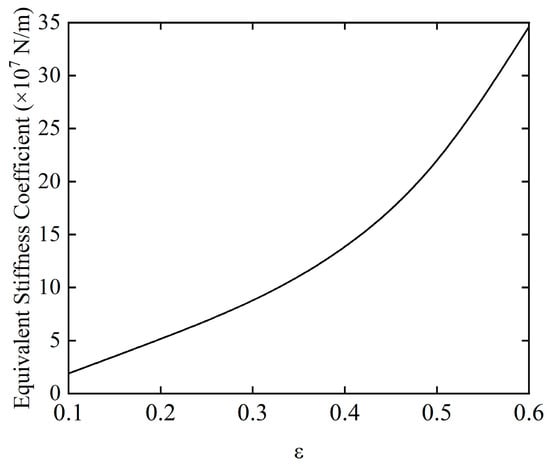

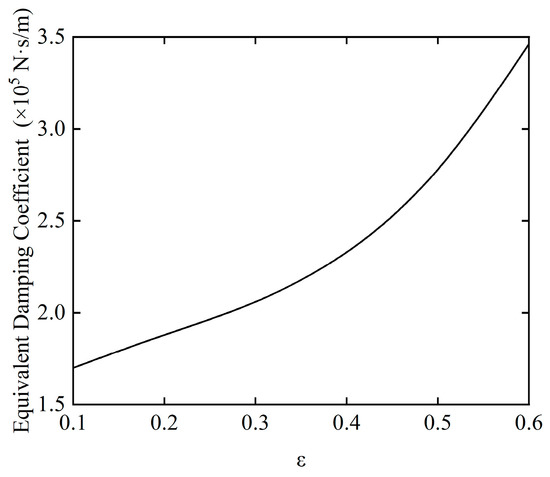

Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the variations in the equivalent stiffness coefficient and equivalent damping coefficient of the SFD at different eccentricities, respectively. The two parameters exhibit significant differential characteristics with the change in eccentricity, and are directly related to the dynamic control effect of the SFD on the rotor system. From the trend of the equivalent stiffness coefficient, as the eccentricity continues to increase, its value rises rapidly. Under low eccentricity conditions, the equivalent stiffness coefficient is approximately 1.9 × 107 N/m. As the eccentricity increases to higher levels, this coefficient gradually increases to 3.4 × 108 N/m, with an increase factor of 1684.21%. The equivalent damping coefficient exhibits a gradual increase within the same eccentricity variation range, rising from an initial value of 1.7 × 105 N·s/m to 3.5 × 105 N·s/m, with an increase of only 105%. The limited growth of the damping coefficient indicates that the ability of the oil film to dissipate vibrational energy through viscosity has not been significantly enhanced, meaning that the vibration reduction damping effect of the SFD core has not been simultaneously improved.

Figure 11.

The effect of imbalance on the equivalent stiffness coefficient.

Figure 12.

The effect of imbalance on the equivalent damping coefficient.

More critically, the substantial increase in the equivalent stiffness coefficient raises two key issues: on one hand, the significant enhancement of the oil film’s equivalent stiffness causes its value to gradually approach or even reach the stiffness level of the elastic supports in the rotor system, disrupting the original design’s dynamic equilibrium where the elastic supports provide the basic stiffness, and the oil film provides the primary damping. On the other hand, the rapid increase in the oil film stiffness is accompanied by a significant enhancement of the oil film’s nonlinear characteristics. When the oil film stiffness reaches a level comparable to that of the elastic supports, the sensitivity of the oil film’s pressure field and flow field to operating parameters such as rotor amplitude and rotational speed increases dramatically, making it more prone to nonlinear phenomena such as stiffness jumps and hysteresis. The enhancement of these nonlinear characteristics significantly alters the inherent vibration characteristics of the rotor system, leading to a broader resonance region and increased difficulty in amplitude control. This ultimately causes a notable decline in the dynamic stability of the rotor system and may even trigger potential risks such as rotor–damper contact and system instability.

5.2. Rotor–SFD System Dynamic Characteristics Test

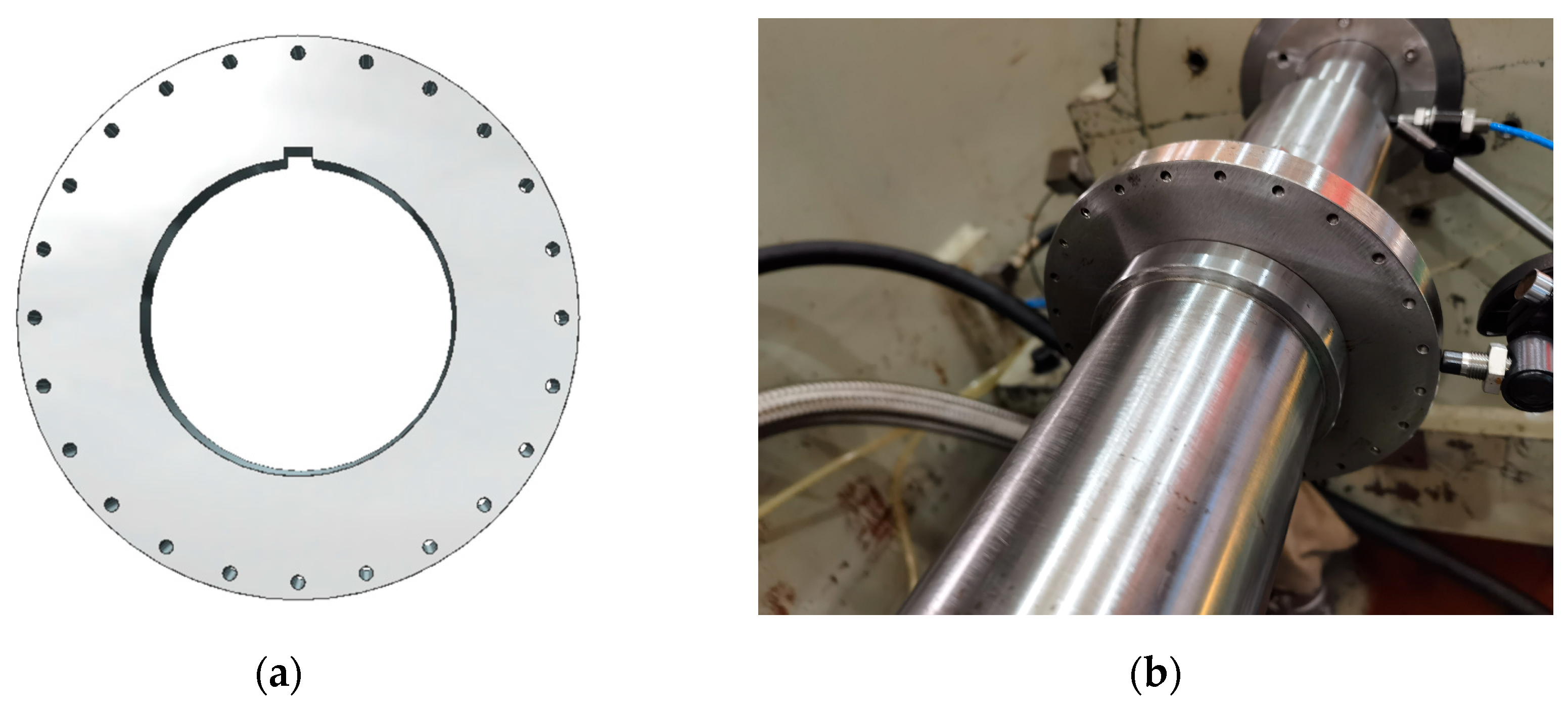

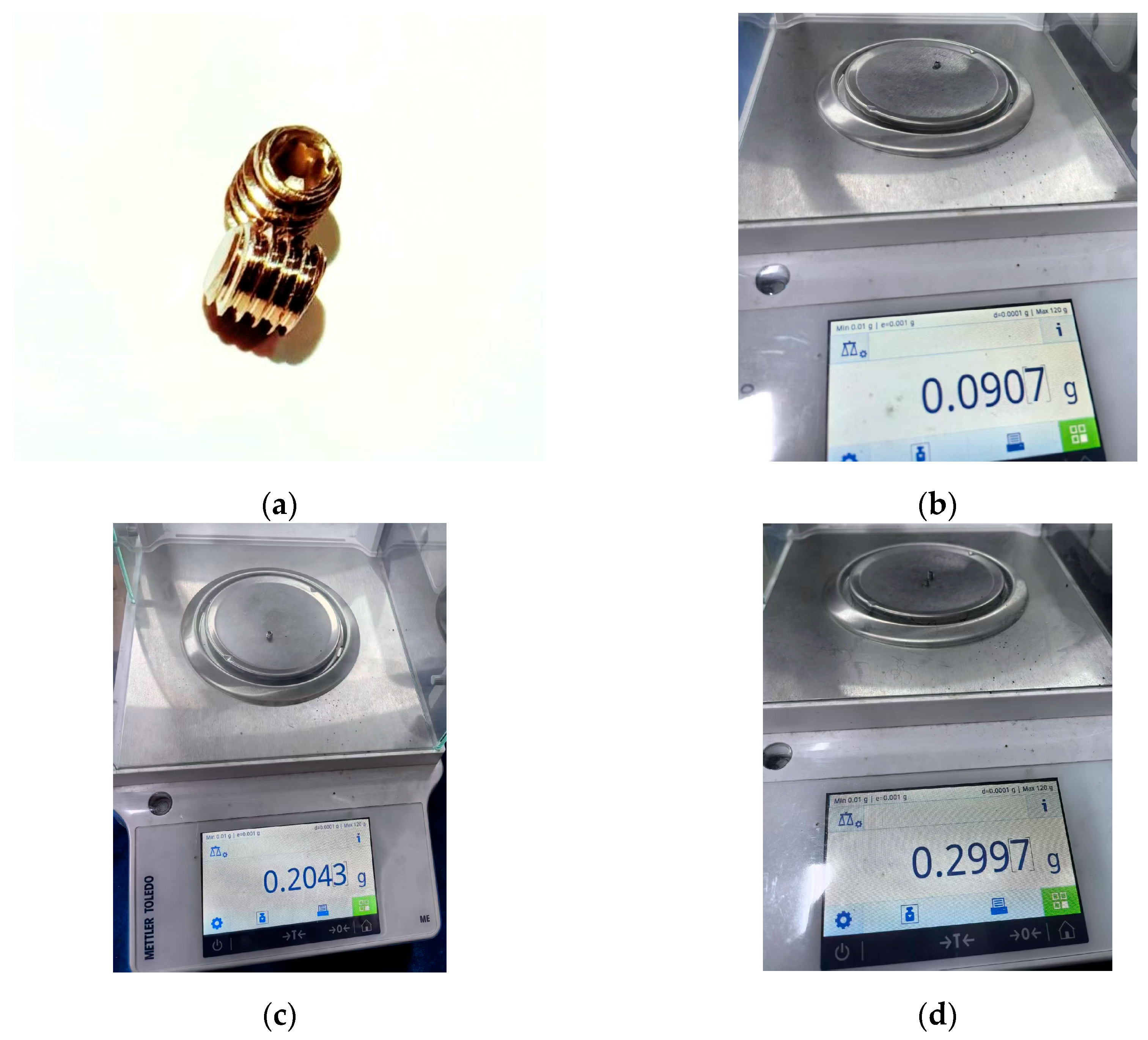

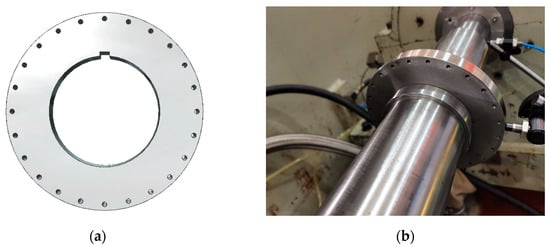

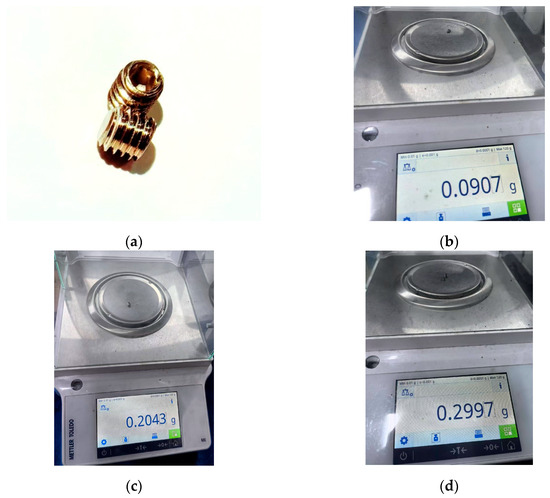

Based on the rotor–SFD system dynamics test rig, this study selects four imbalance levels of 0.0327, 0.0907, 0.2043, and 0.2997 g for rotor dynamics testing. The imbalance is applied by adjusting the balancing holes and bolts around the rotor disc. There are 24 evenly distributed M4 precision bolt holes around the rotor disc, with different lengths of 304 stainless steel bolts used as the standard configuration units. The imbalance is controlled by adjusting the bolt size and angular position. The initial imbalance of the rotor after dynamic balancing is 0.0327 g. Subsequently, the imbalance levels of the rotor system are adjusted by selecting bolts of 0.0907, 0.2043, and 0.2997 g. Figure 13 shows the 3D model and the actual image of the balancing holes around the rotor disc. Figure 14 displays the actual image of the balancing bolts and a schematic diagram for the weight measurement of the balancing bolts (using a microgram-level electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg). By applying the method of controlling variables, the study investigates the evolution of the rotor–SFD system’s axis trajectory and vibration amplitude characteristics under different imbalance excitations.

Figure 13.

Balancing Hole. (a) 3D Model of the Balancing Hole; (b) Actual Image of the Balancing Hole.

Figure 14.

Structural Diagram of the Balancing Bolt. (a) Balancing Bolt; (b) 0.0907 g; (c) 0.2043 g; (d) 0.2997 g.

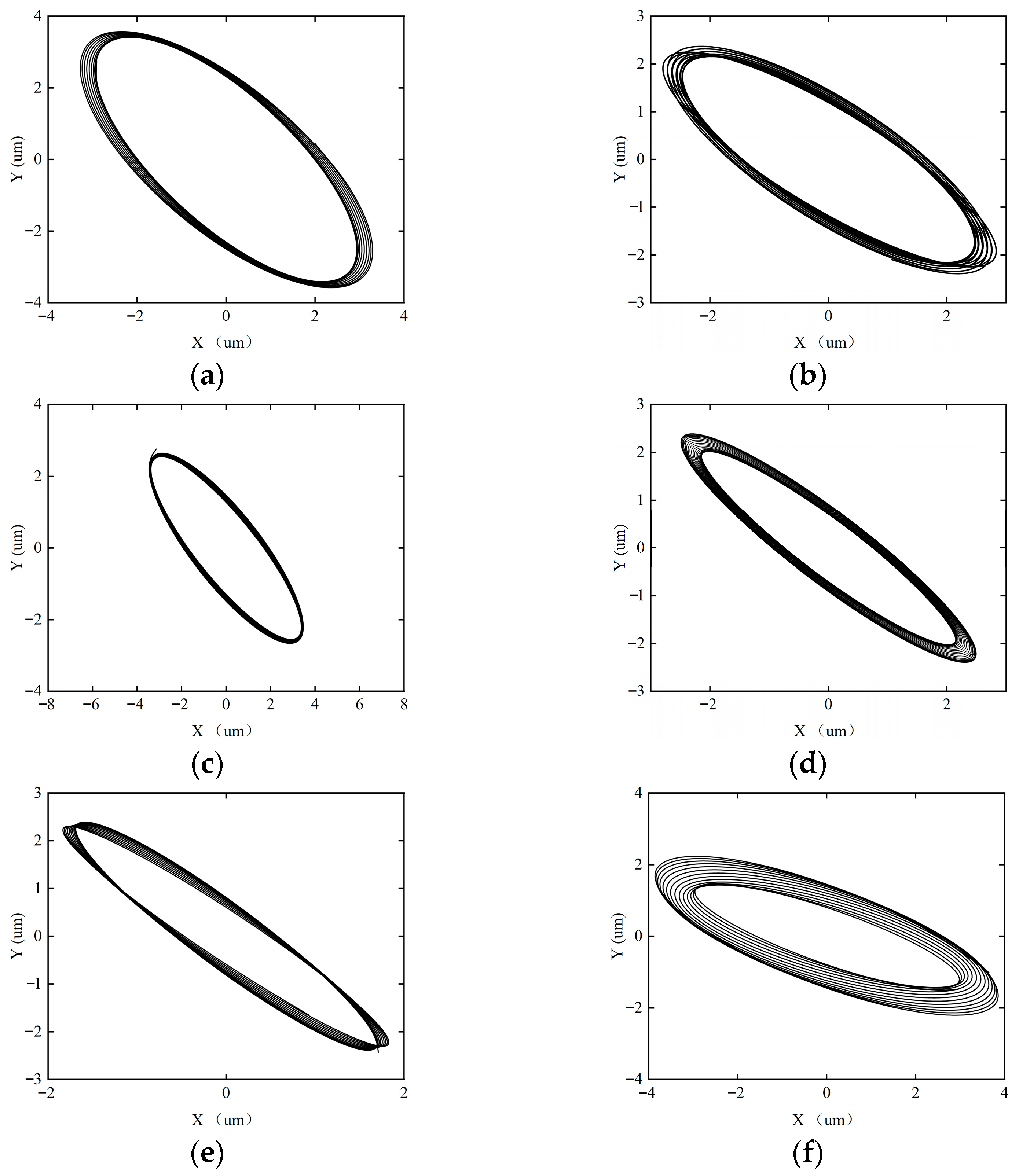

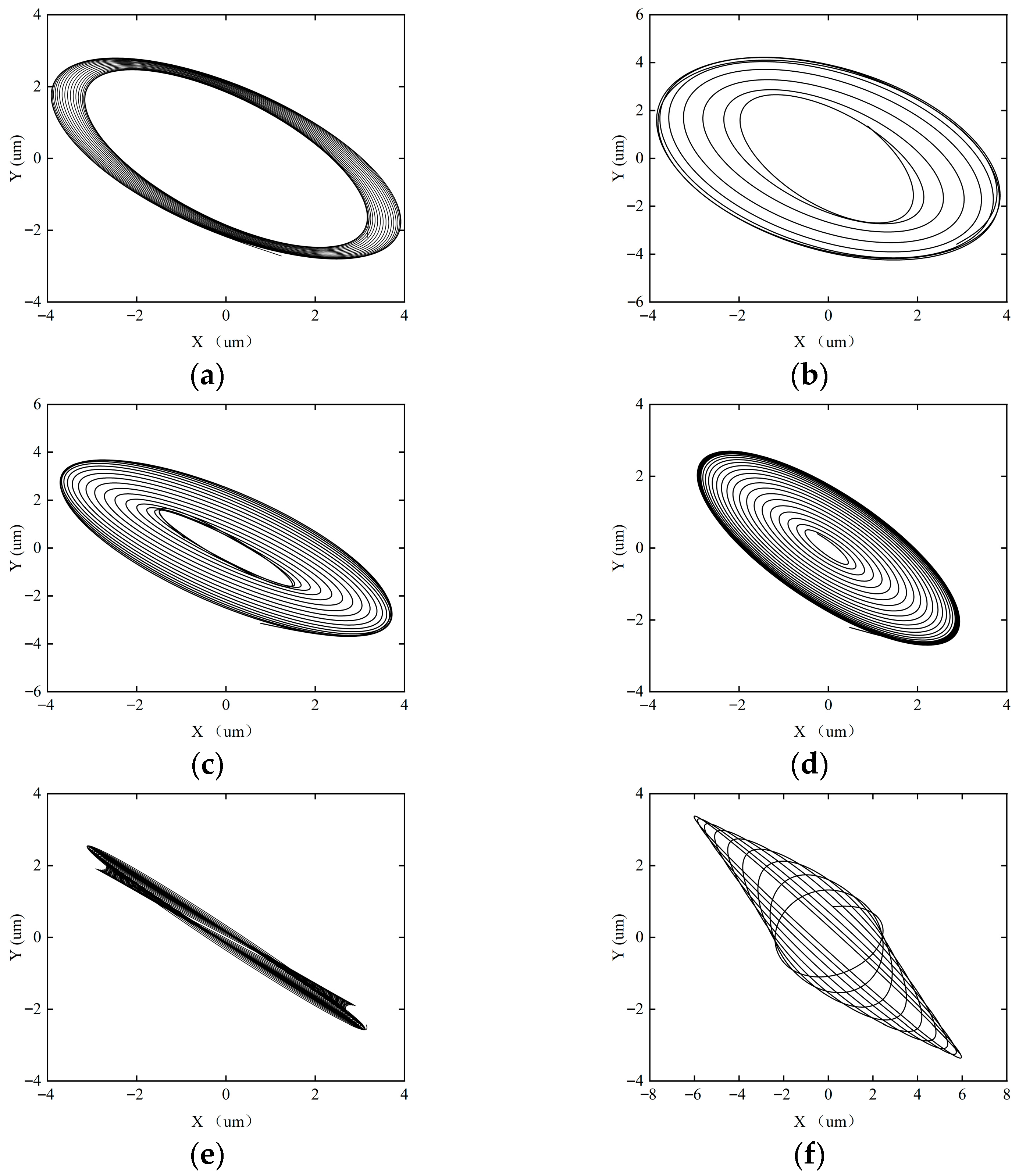

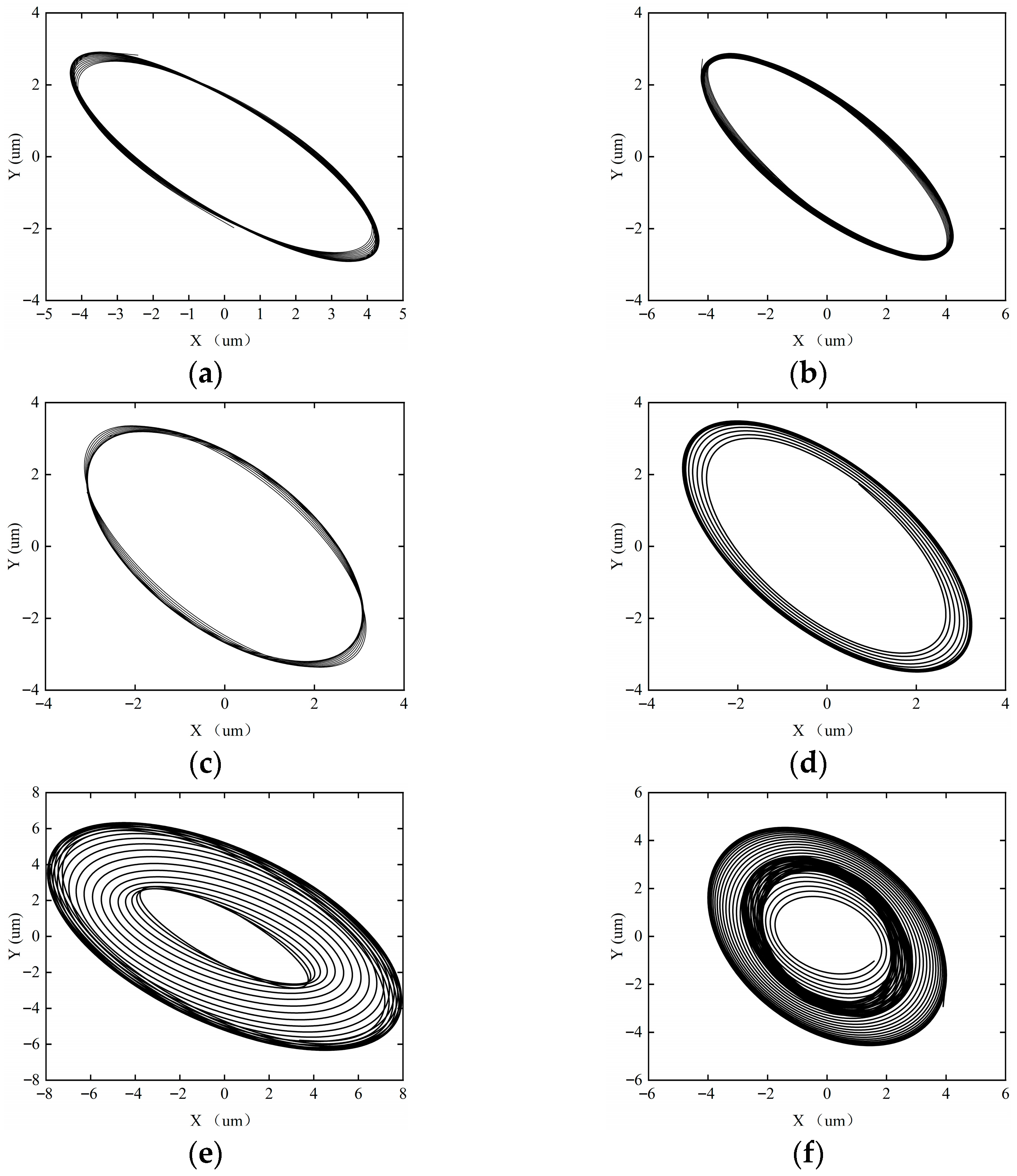

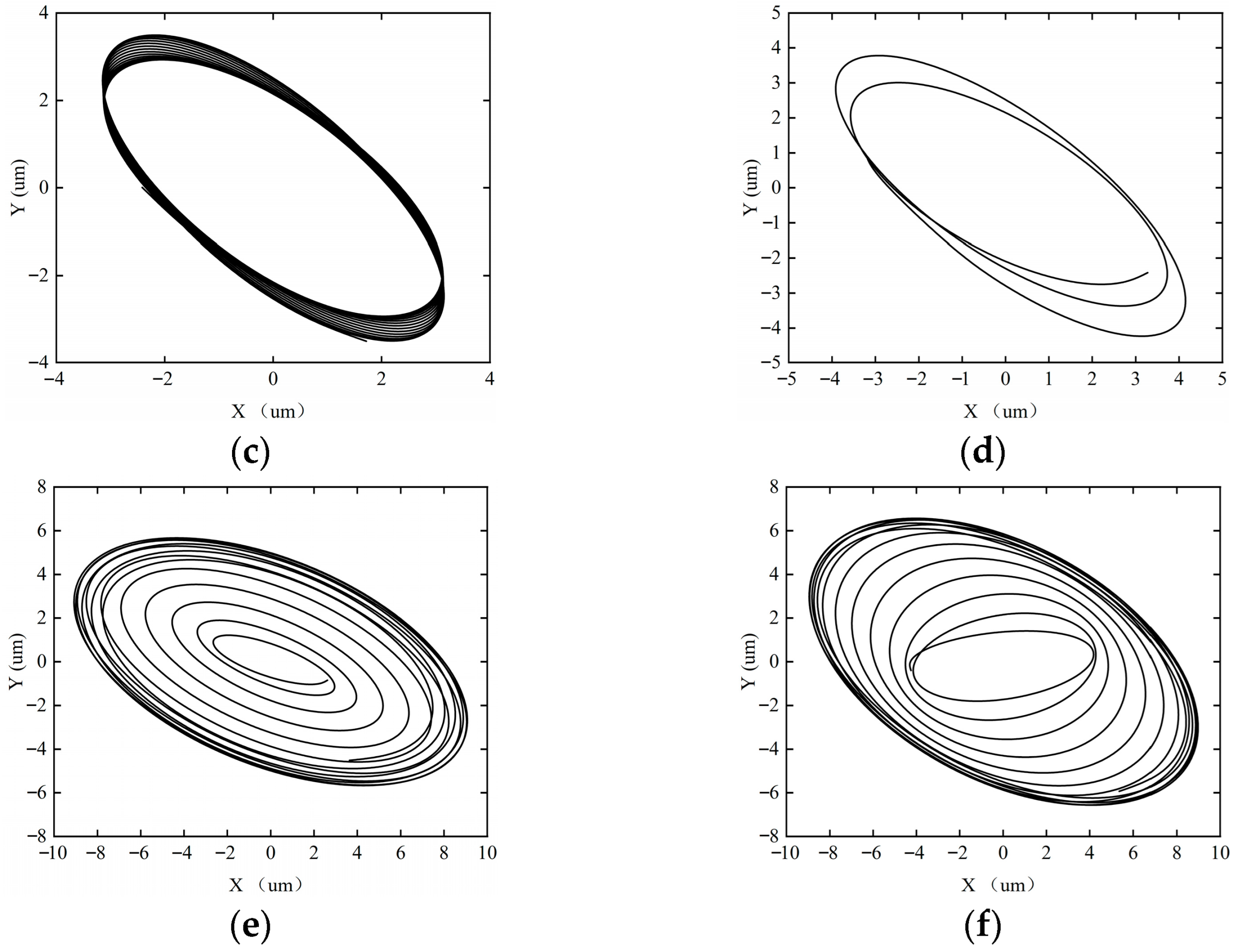

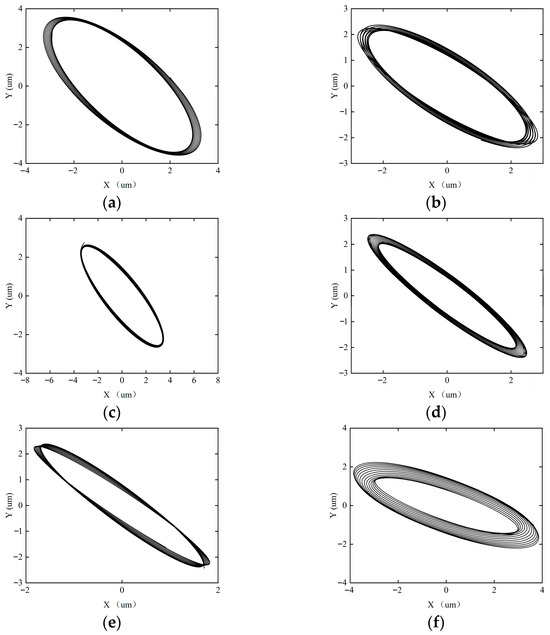

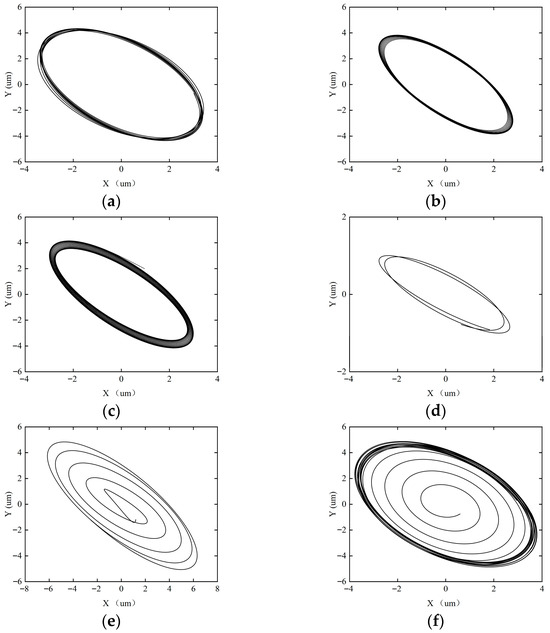

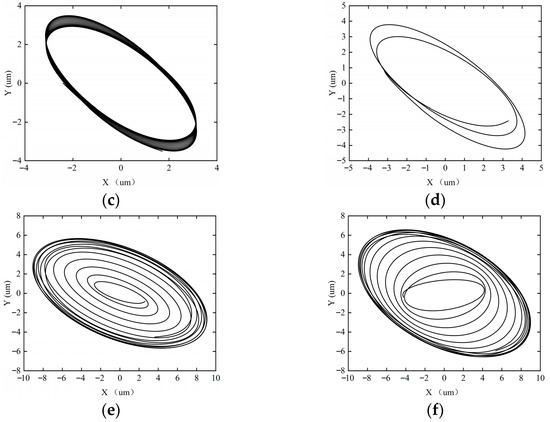

Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 show the axial trajectories of the rotor–SFD system under different imbalanced excitations.

Figure 15.

Axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system when the imbalance is 0.0327 g. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 16.

Axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system when the imbalance is 0.0907 g. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 17.

Axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system when the imbalance is 0.2043 g. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 18.

Axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system when the imbalance is 0.2997 g. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 15 shows the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system when the imbalance is 0.0327 g. When the imbalance is 0.0327 g, the rotor–SFD system experiences weak imbalanced excitation, with a small eccentricity of the SFD, resulting in strong system stability. Under the condition of rotational speed ω < 18,000 rpm, the axial trajectory exhibits a closed single-cycle topological structure, with the system maintaining a periodic-1 motion state. When ω ≥ 18,000 rpm, the axial trajectory bifurcates into a multi-ring nested form, and the system enters a quasi-periodic motion state. This evolutionary process indicates that the system’s stability undergoes a phase transition: periodic-1 motion → quasi-periodic motion.

Figure 16 shows the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system when the imbalance is 0.0907 g. When the imbalance increases to 0.0907 g, the imbalanced excitation of the rotor–SFD system intensifies, and the system gradually tends towards an unstable state. From the axial trajectory, it can be observed that when ω < 10,000 rpm, the axial trajectory maintains a closed single-cycle topological structure, and the system remains in periodic-1 motion. When ω = 12,000 rpm, the trajectory takes a double-ring nested form, and the system enters periodic-2 harmonic motion. When ω = 15,000 rpm, the trajectory further bifurcates into a four-ring structure, representing periodic-4 motion. At ω = 18,000 rpm, the trajectory shows characteristics of a multi-ring chaotic attractor, and the system becomes unstable, entering quasi-periodic motion. This process reveals the degradation path of stability: periodic-1 motion → periodic-2 motion → periodic-4 motion → quasi-periodic motion.

Figure 17 shows the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system when the imbalance is 0.2043 g. When the imbalance increases to 0.2043 g, the imbalanced excitation of the rotor–SFD system becomes stronger, and the system accelerates towards instability. At ω = 18,000 rpm, the system enters chaotic motion. The system’s stability changes as follows: periodic-1 motion → periodic-2 motion → periodic-4 motion → quasi-periodic motion → chaotic motion.

Figure 18 shows the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system when the imbalance is 0.2997 g. When the imbalance reaches 0.2997 g, the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of the SFD dominate the system’s stability, and the system exhibits significant strong nonlinear behavior. Axial trajectory analysis shows that even at low rotational speeds, the system has already deviated from periodic motion and directly enters the quasi-periodic motion mode. As the rotational speed increases to 15,000 rpm, the system enters a chaotic motion state. The system’s stability changes as follows: quasi-periodic → chaotic.

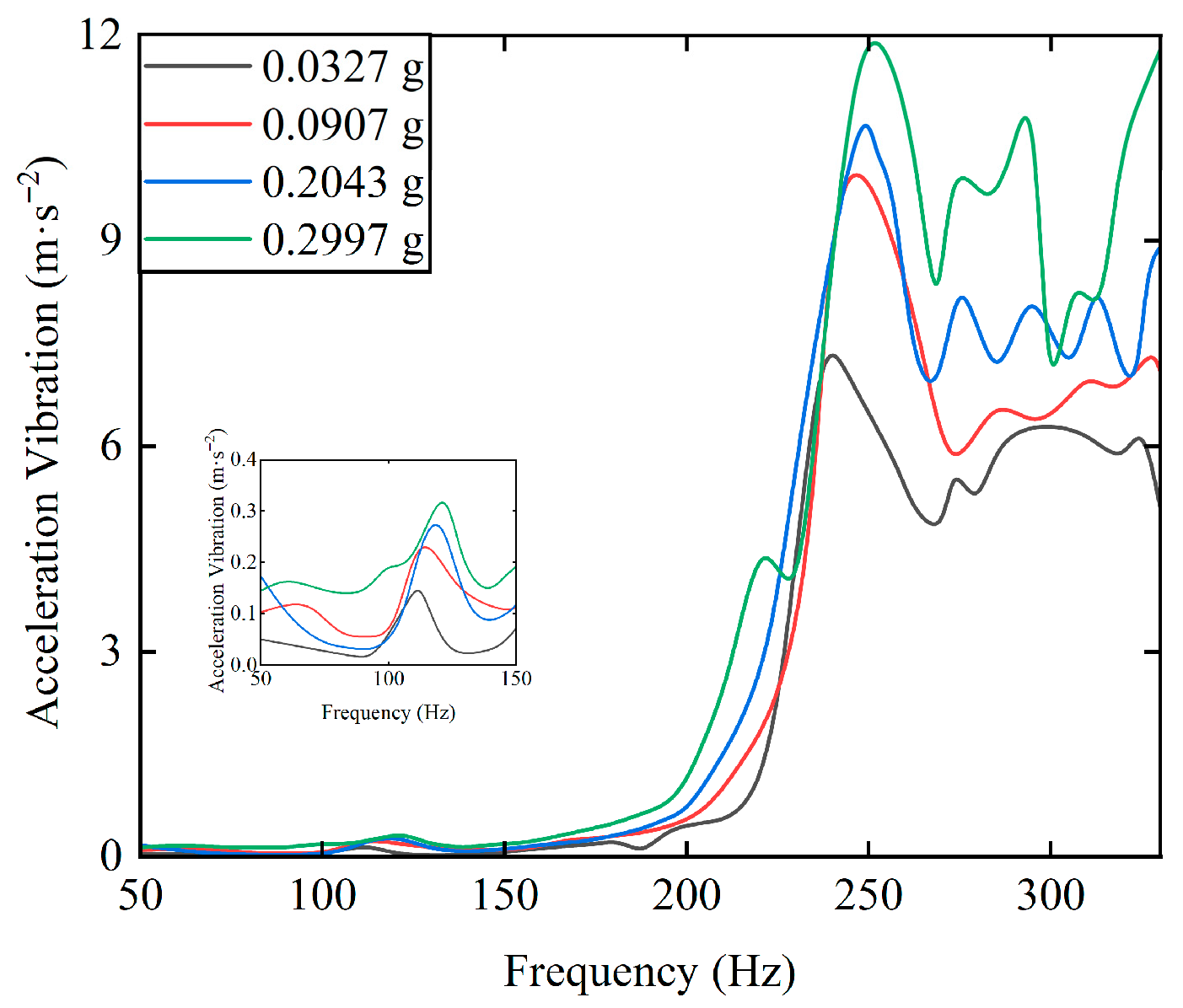

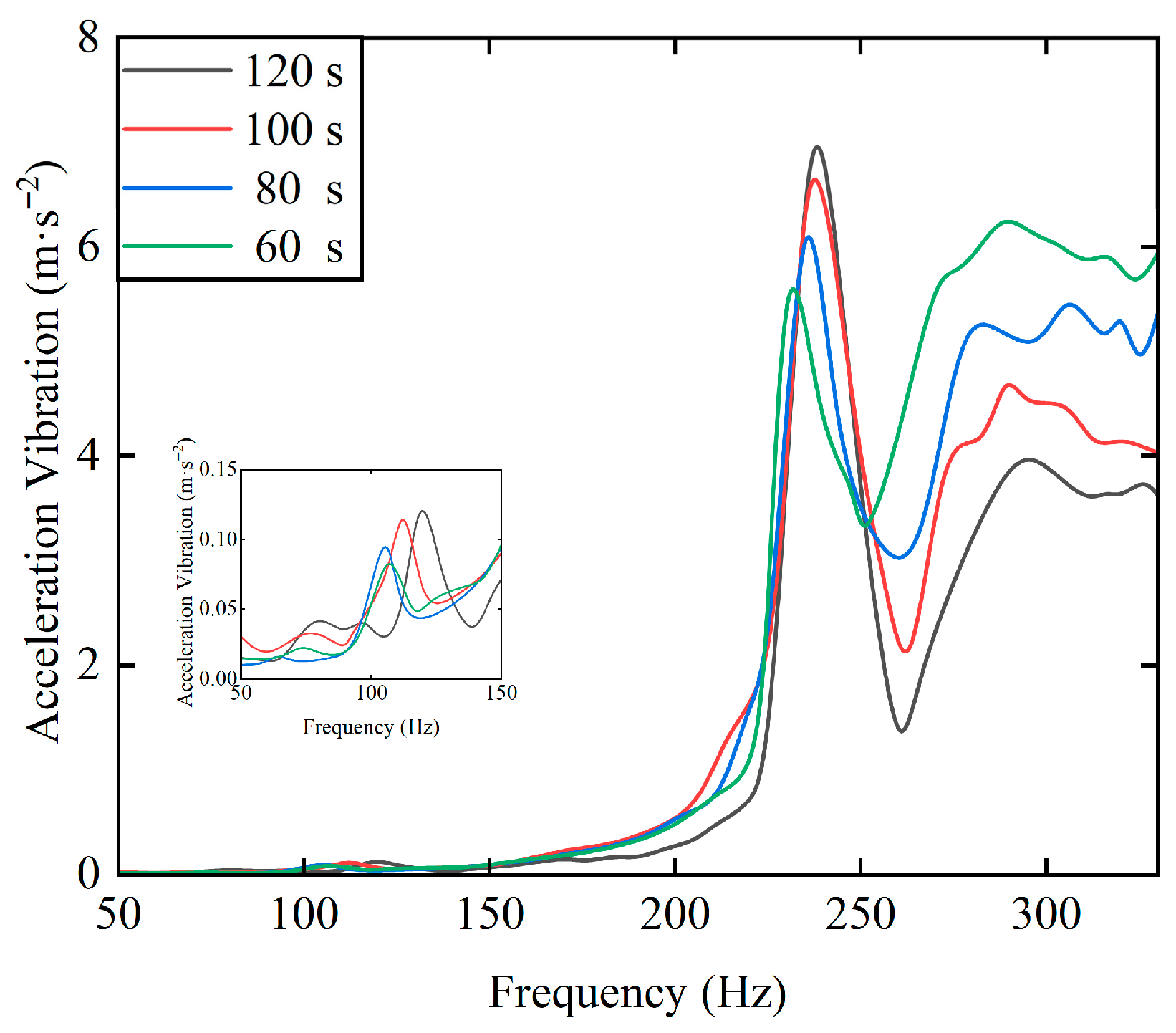

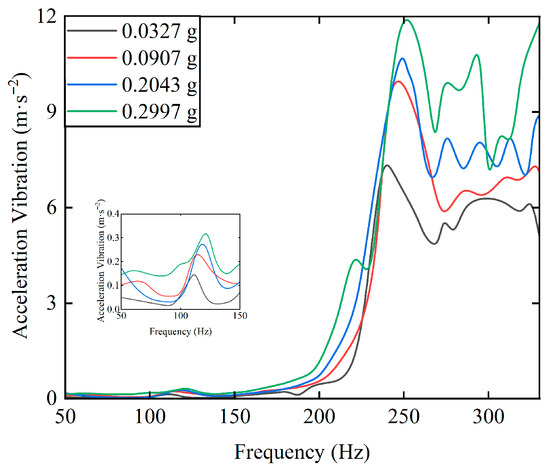

Figure 19 shows the acceleration vibration curves of the rotor system under different imbalance levels. As the imbalance increases, the enhanced centrifugal excitation force and the nonlinear coupling effect with the oil film damping become stronger. That is, the increase in imbalance leads to equivalent stiffness hardening, forcing the system to reach an energy equilibrium state at higher rotational speed ranges. The critical speed threshold shifts to higher precession frequencies, and the critical speed range expands. At the same time, the enhanced centrifugal load strengthens the inertial effects of the oil film, exacerbating the spatiotemporal non-uniformity of the oil film pressure field, and enhancing the cavitation effect. The coupling of multiple physical fields intensifies, leading to an increase in the system’s acceleration vibration amplitude and a decline in system stability.

Figure 19.

The acceleration vibration curves of the rotor–SFD system under different imbalance levels.

6. The Impact of Acceleration

Since the test rig used in this study cannot directly alter the acceleration, the effective acceleration is indirectly adjusted by controlling the duration (T) required for the motor to reach its maximum speed of 32,600 rpm after startup.

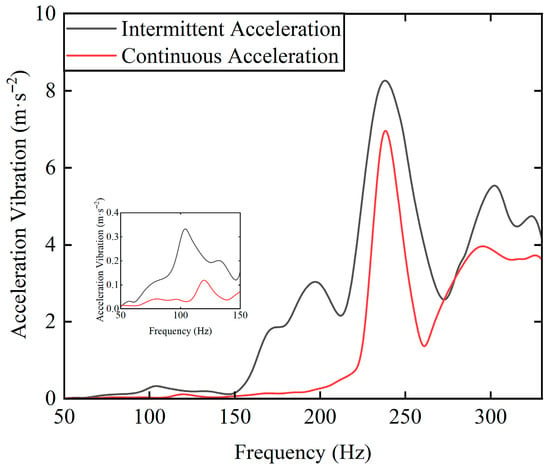

To study the effect of acceleration on the rotor–SFD system, this paper adopts two acceleration modes: continuous acceleration and intermittent acceleration. The continuous acceleration mode is defined as a smooth acceleration from a standstill to 20,000 rpm without interruption. The intermittent acceleration mode adopts a stepwise speed-up strategy (3000 → 8000 → 13,000 → 15,000 → 18,000 → 20,000 rpm), with each speed node maintained for 30 s in a steady-state operation. Figure 20 shows the acceleration vibration curves of the rotor–SFD system under intermittent and continuous acceleration. The comparative analysis indicates that under the intermittent acceleration mode, the system experiences different dynamic equilibrium loads during the steady-state operation phase and the acceleration transient phase, resulting in a significant increase in rotor vibration amplitude. The specific manifestations are as follows: (1) The transient impact load during the switching of each speed node leads to a larger vibration amplitude at the discontinuous points compared to the adjacent speed ranges. (2) The steady-state dwell near the critical speed region (such as the 15,000 rpm node) causes sustained resonance between the external excitation and the rotor’s natural frequency, resulting in continuous energy accumulation, which increases the amplitude in the critical region compared to the continuous acceleration mode. (3) The re-acceleration process after steady-state operation in the high-speed domain (18,000 rpm) shows a cumulative increase in vibration amplitude due to the coupling effects of fluid inertia and cavitation.

Figure 20.

The rotor system acceleration vibration amplitude under intermittent and continuous acceleration conditions.

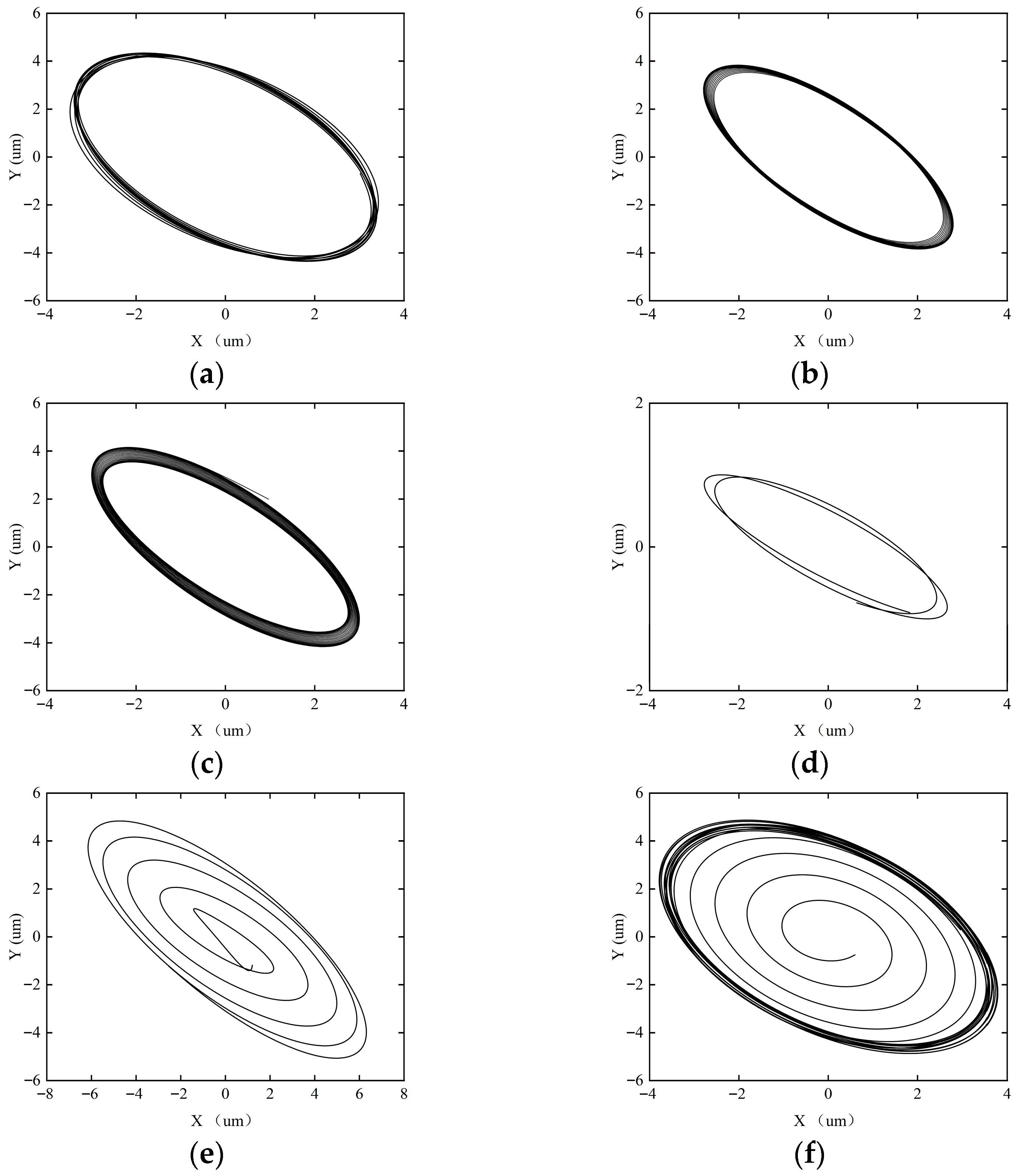

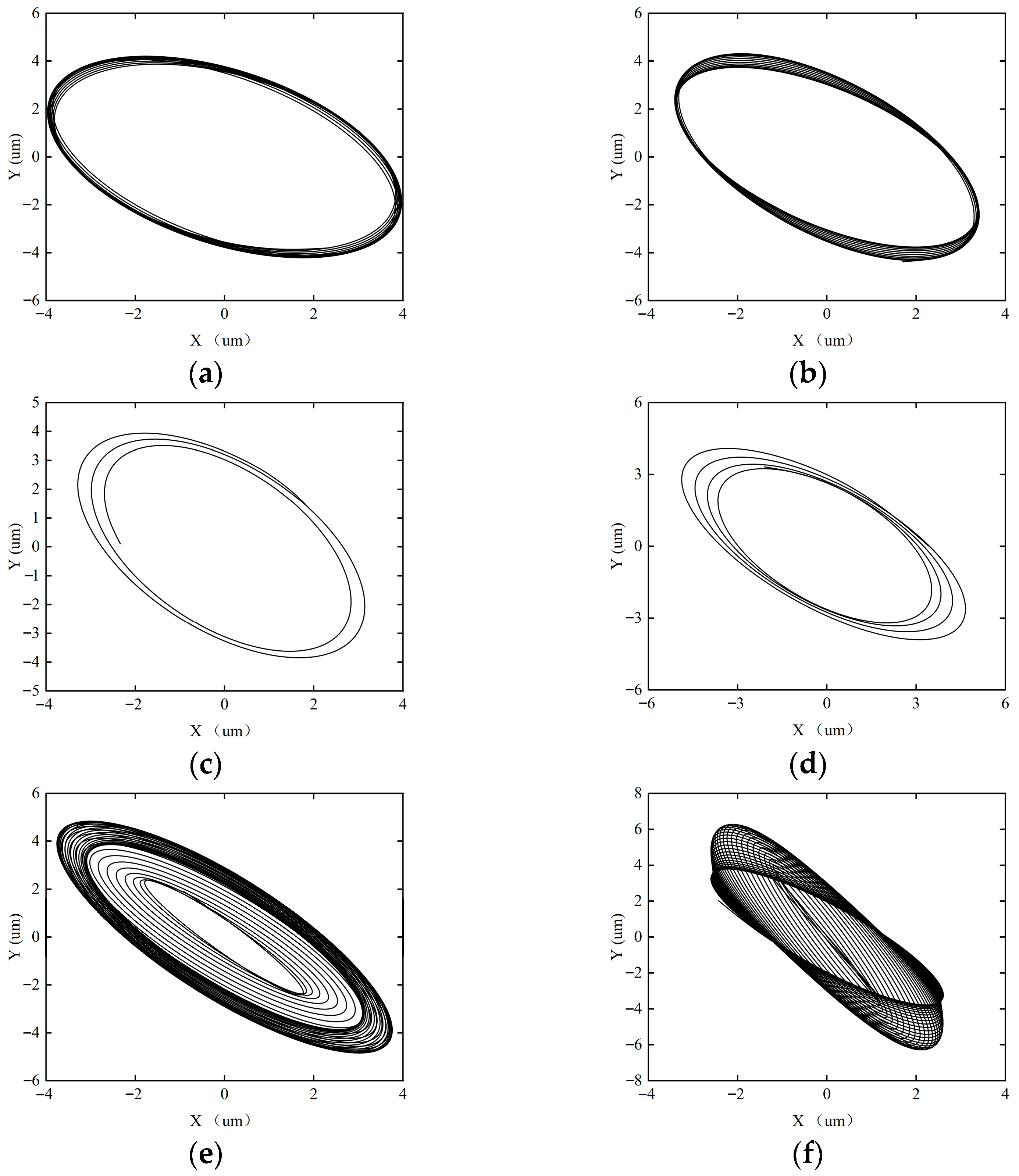

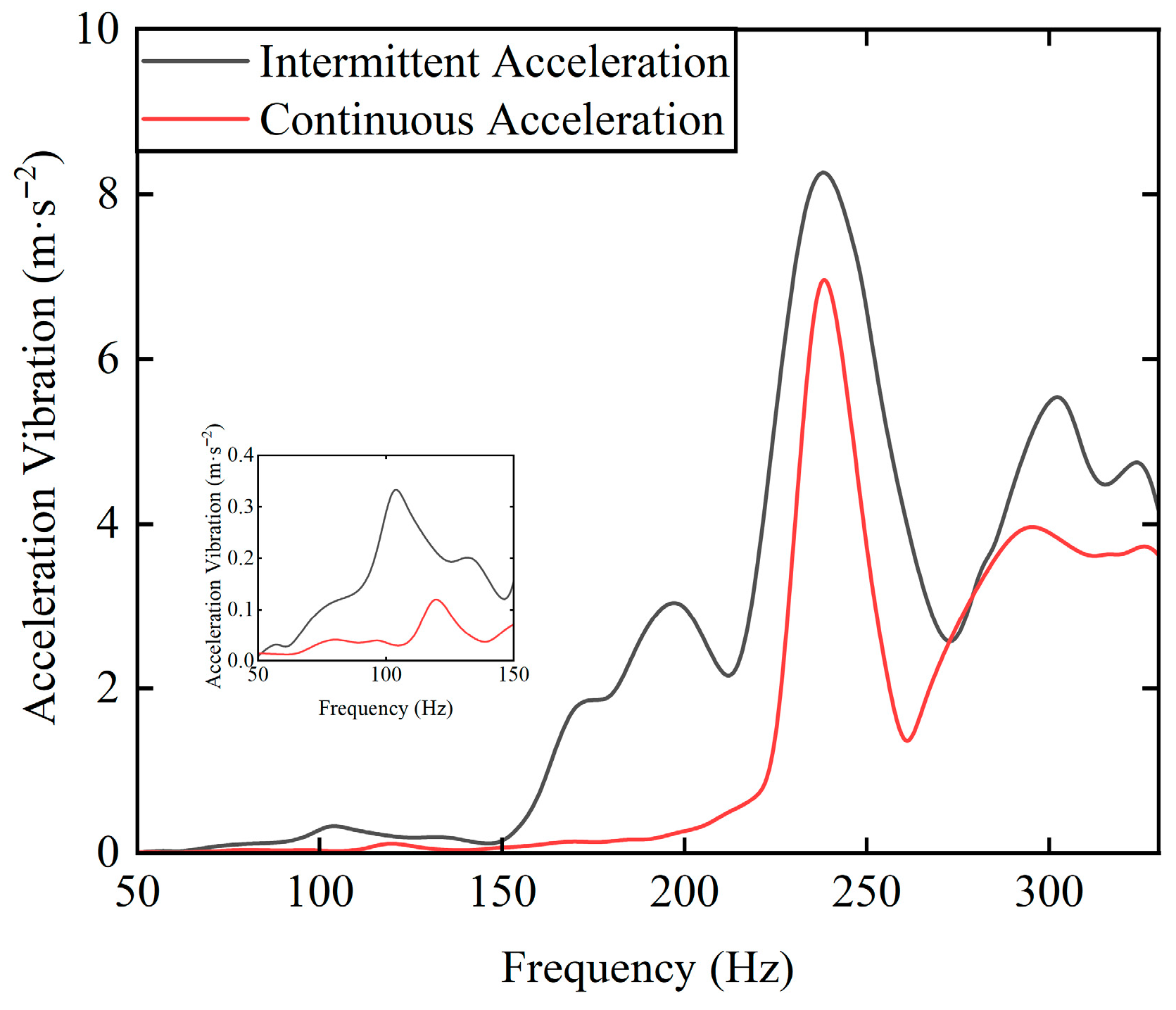

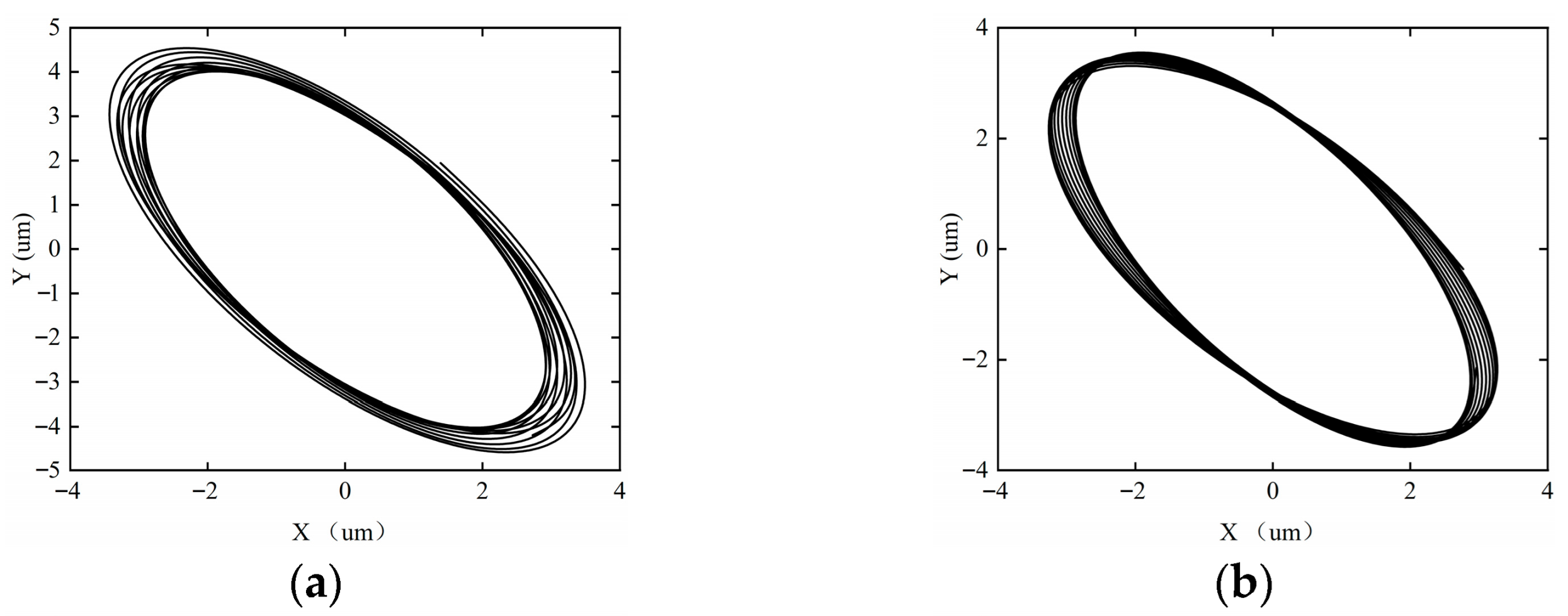

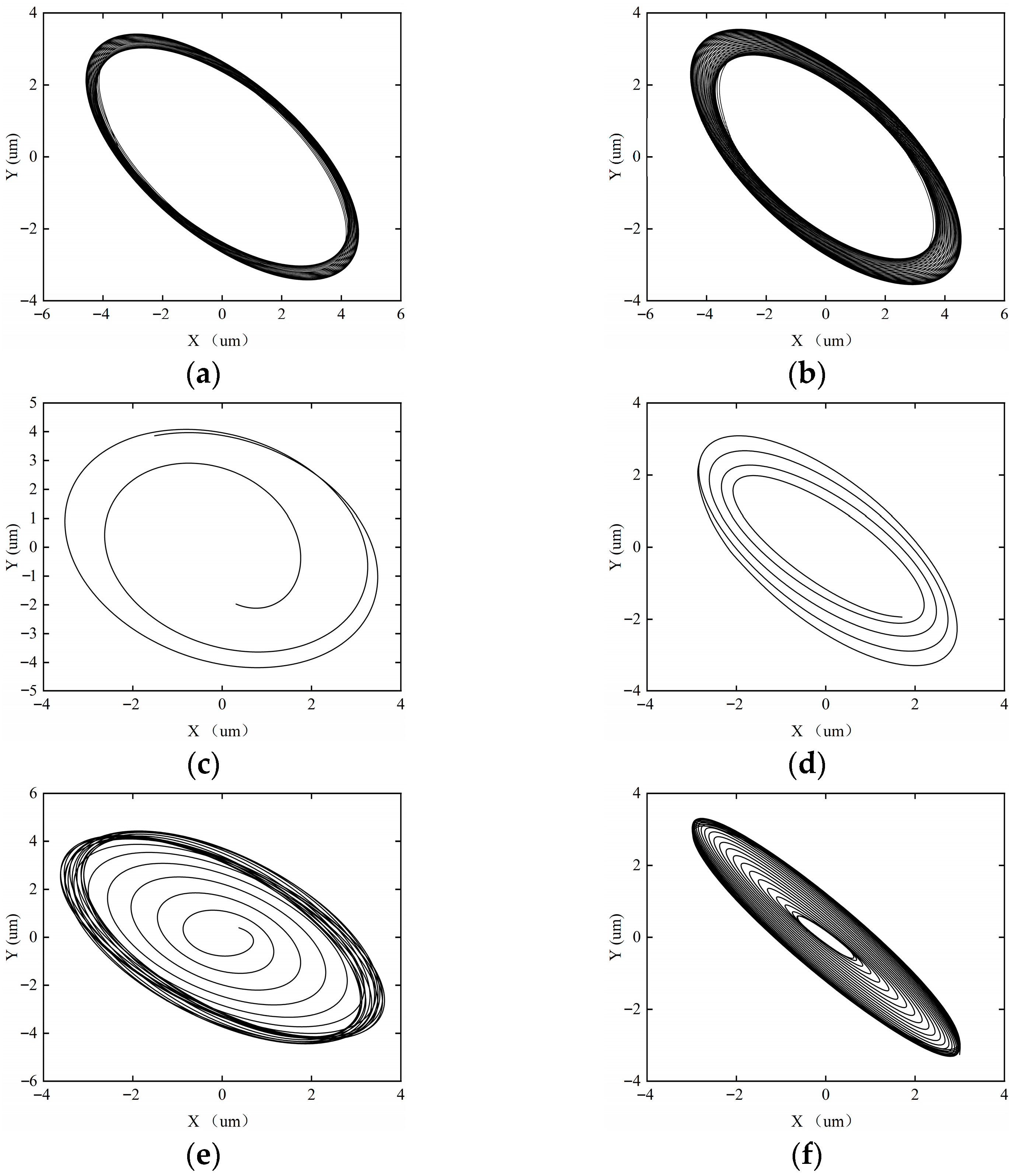

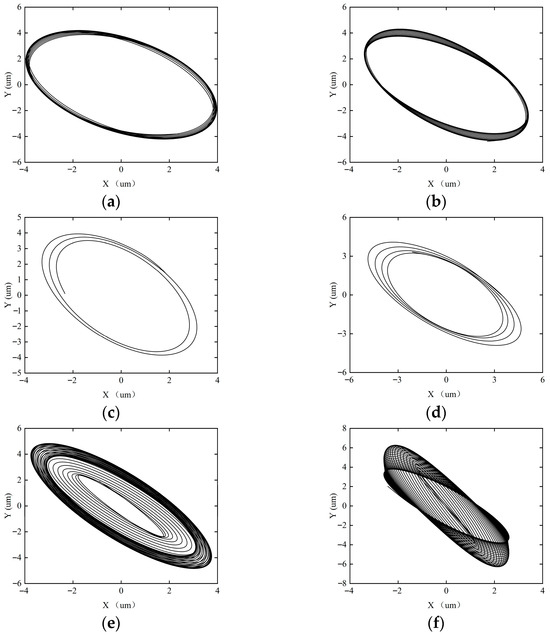

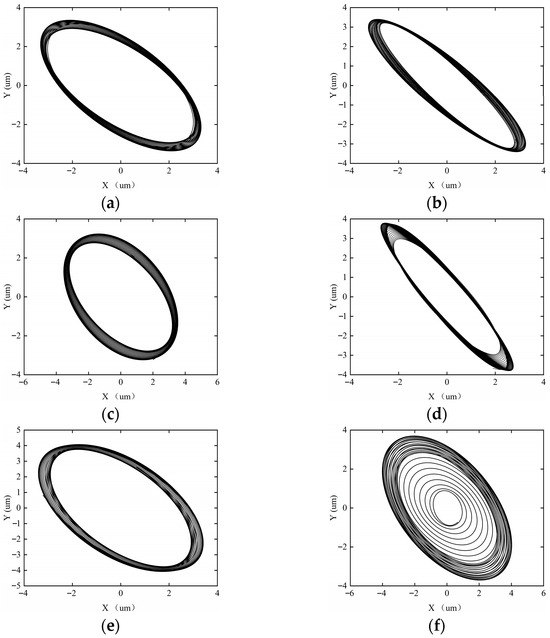

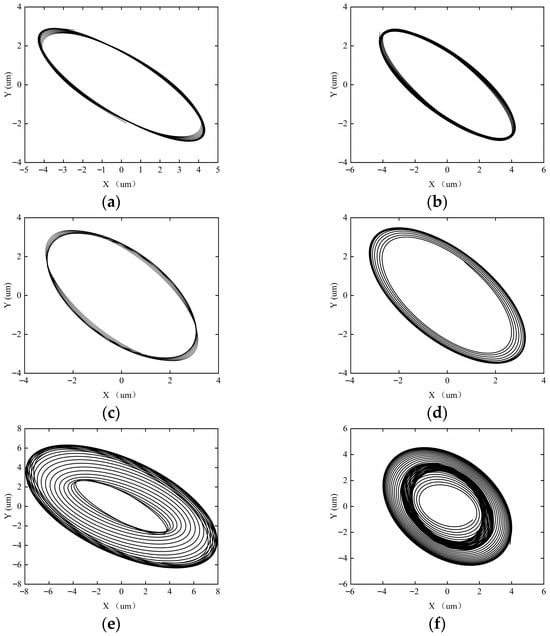

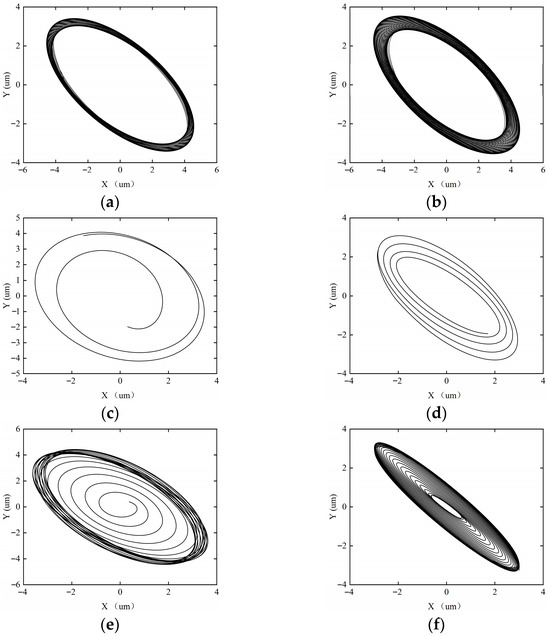

In order to study the effect of acceleration on the dynamic characteristics of the rotor–SFD system, dynamic characteristic tests of the rotor–SFD system were conducted with acceleration times of T = 120, 100, 80, and 60 s. Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23 and Figure 24 show the axial trajectory evolution of the rotor–SFD system under different acceleration times.

Figure 21.

The axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system under the acceleration time of T = 120 s. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 22.

The axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system under the acceleration time of T = 100 s. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 23.

The axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system under the acceleration time of T = 80 s. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 24.

The axial trajectory of the rotor–SFD system under the acceleration time of T = 60 s. (a) ω = 5000 rpm; (b) ω = 8000 rpm; (c) ω = 10,000 rpm; (d) ω = 12,000 rpm; (e) ω = 15,000 rpm; (f) ω = 18,000 rpm.

Figure 21 illustrates the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system at T = 120 s. Under the T = 120 s (low acceleration) condition, the system exhibits higher stability due to the weakening of the inertial force effect caused by the reduced acceleration. The axial trajectory analysis shows that when the rotational speed ω < 18,000 rpm, the trajectory remains a closed single-period topology, and the system stabilizes in a period-1 motion state. However, when the rotational speed increases to ω ≥ 18,000 rpm, the trajectory bifurcates into a multi-ring chaotic attractor, and the system becomes unstable, entering a quasi-periodic motion. The change in system stability is period-1 → quasi-periodic.

Figure 22 illustrates the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system at T = 100 s. When T = 100 s, the system’s acceleration increases, enhancing the effect of inertial forces. The rate of change in the oil film height h’ increases, and the stability of the oil film is compromised. The axial trajectory analysis shows that when ω = 15,000 rpm, the system enters quasi-periodic motion. The change in system stability is period-1 motion → quasi-periodic motion.

Figure 23 illustrates the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system at T = 80 s. When T = 80 s, the system’s acceleration is relatively large, further enhancing the inertial forces, leading to increased instability of the system. When ω = 12,000 rpm, the system exhibits two circular rings, and the system enters period-2 motion. When ω = 15,000 rpm, the system transitions into quasi-periodic motion. The change in system stability is period-1 motion → period-2 motion → quasi-periodic motion.

Figure 24 illustrates the shaft center trajectory of the rotor system at T = 60 s. When T = 60 s, the system’s acceleration is high, resulting in large inertial forces. The transient response of the oil film is enhanced, the oil film thickness changes rapidly, and the nonlinearity of the squeeze film increases, leading to greater system instability. Axial trajectory analysis shows that when ω = 10,000 rpm, the system enters period-2 motion. When ω = 12,000 rpm, the system enters period-4 motion. When ω = 15,000 rpm, the system transitions into quasi-periodic motion. The change in system stability is period-1 motion → period-2 motion → period-4 motion → quasi-periodic motion.

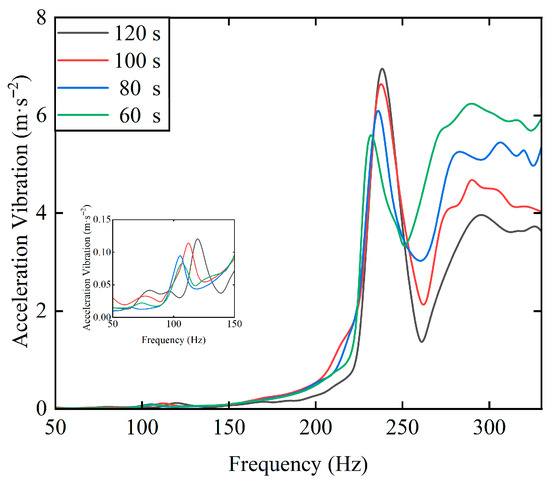

Figure 25 shows the rotor vibration amplitude at different acceleration times. As the acceleration time decreases (acceleration increases), the system’s critical speed corresponding to the amplitude decreases. The rotor quickly passes through the critical speed region, significantly compressing the time-domain effect window of resonance excitation, which effectively reduces the accumulation of vibration energy. The increase in acceleration synchronously strengthens the dynamic coupling between inertial forces and pressure, leading to the reconstruction of the system’s dynamic stiffness matrix characteristics—with the nonlinear enhancement of the cross-coupling terms between the mass matrix and damping matrix. This time-varying reconstruction effect of the stiffness matrix forces the root locus of the system’s characteristic equation to shift towards the high-frequency domain, thereby raising the critical speed threshold.

Figure 25.

The rotor vibration amplitude at different acceleration times.

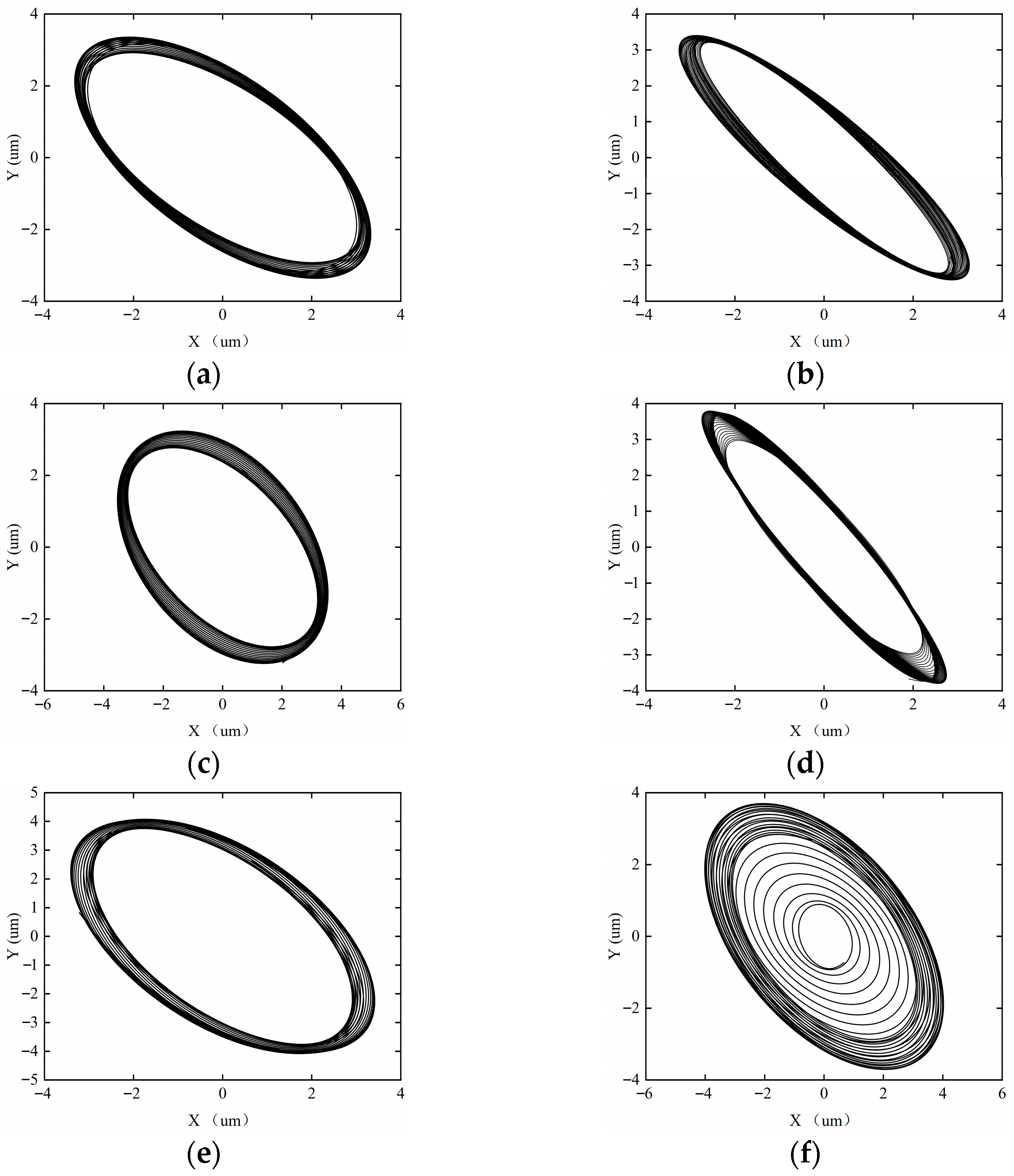

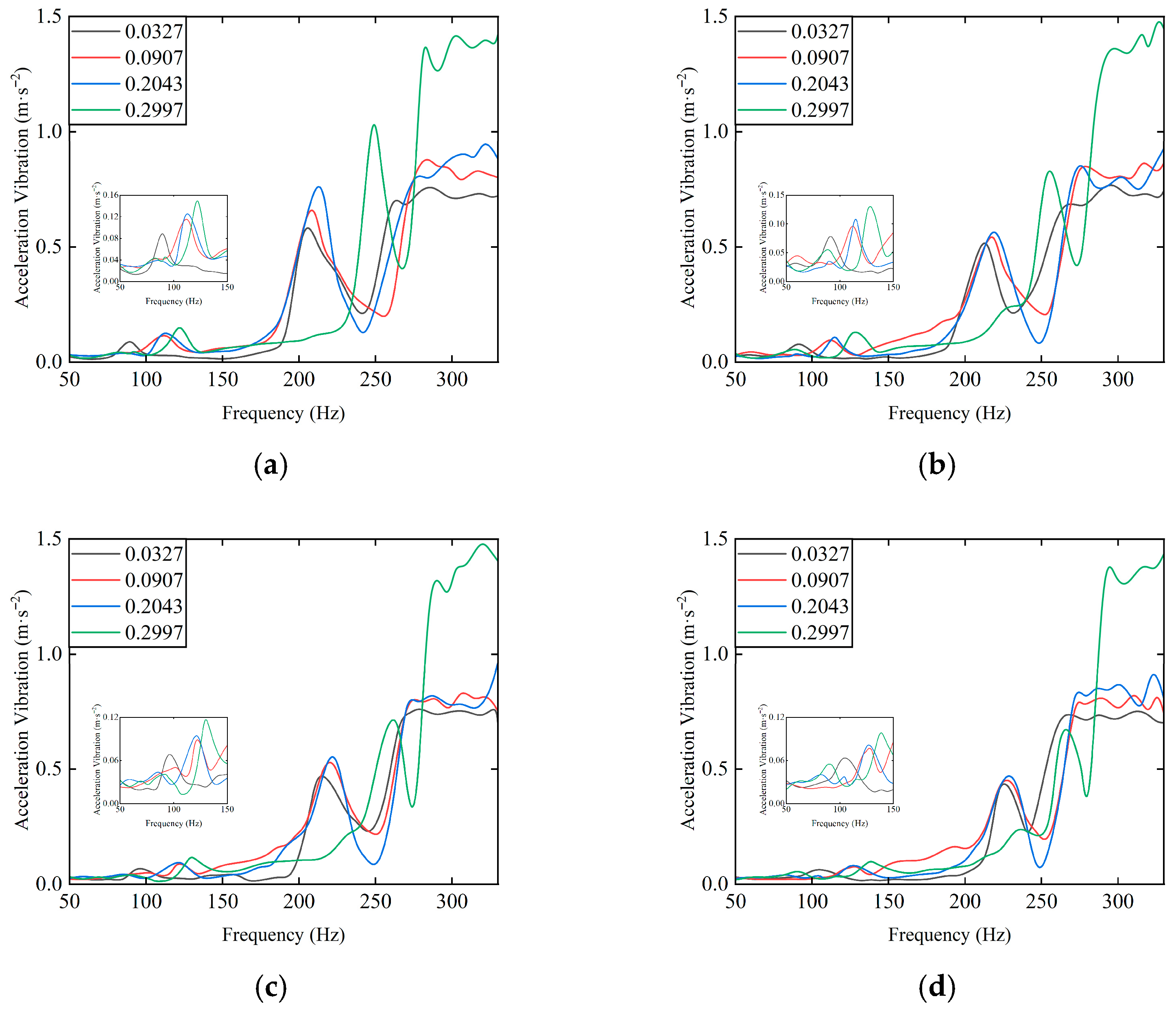

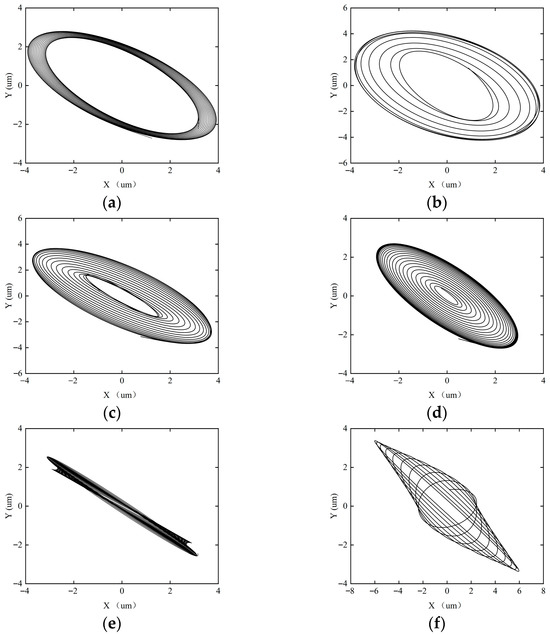

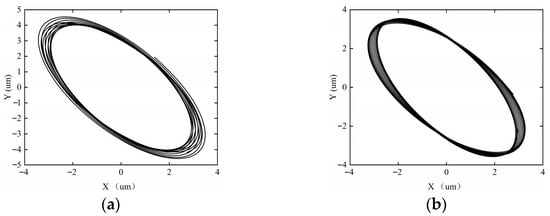

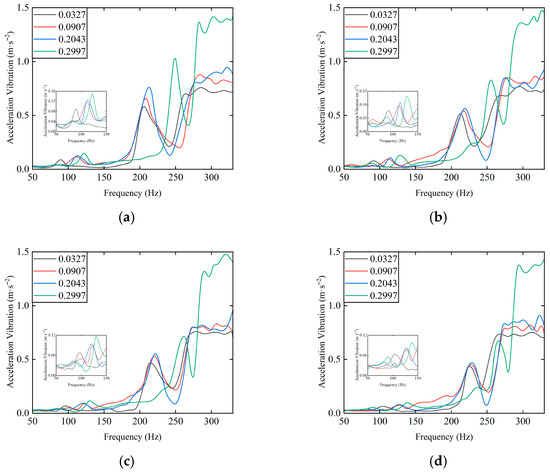

Figure 26 shows the suppression effect of different accelerations on the imbalance. Experimental studies indicate that increasing acceleration can effectively weaken the vibration amplification effect caused by the increase in imbalance in the rotor–SFD system. The amplitude suppression efficiency can reach 27% to 38%. Under small imbalance conditions, increasing acceleration can significantly reduce the impact of increasing imbalance. Under larger imbalance conditions, a noticeable amplitude reduction effect can still be observed. However, under high imbalance conditions, the system enters a strong nonlinear domain, and the vibration reduction effect brought by increasing acceleration is weakened.

Figure 26.

Effect of Different Accelerations on Imbalance. (a) T = 120 s; (b) T = 100 s; (c) T = 80 s; (d) T = 60 s.

7. Discussion

This study investigates the rotor–SFD system through a combination of theoretical simulations and experimental testing.

The key conclusions and innovations are summarized as follows: It reveals the effects of imbalance-induced eccentricity in the SFD on the oil film’s mechanical properties (equivalent stiffness K, equivalent damping C) and the system’s nonlinear behavior. It clarifies the regulatory effect of acceleration on the dynamic response of the rotor system, and elucidates the applicable conditions for using variable acceleration strategies to mitigate the negative effects of imbalance excitation, providing theoretical support for system parameter optimization and stability control.

Key experimental results were obtained: compared to the continuous acceleration mode, in the intermittent acceleration mode, the system experiences different dynamic balance loads during the steady-state and acceleration transient phases, leading to a significant increase in rotor vibration amplitude. As the acceleration increases, the rotor system’s vibration amplitude decreases, allowing it to pass through the critical speed region more quickly, thereby improving system stability. However, when the acceleration is too high, the rapid variation in oil film thickness exacerbates system instability. Furthermore, increasing acceleration can effectively mitigate the vibration amplification effect caused by an increase in imbalance in the rotor–SFD system, with a more pronounced effect observed under low imbalance conditions.

In contrast to previous studies [49,50], the distinctive features and value of this research are reflected in two aspects: First, the theoretical and experimental design is based on practical engineering backgrounds, making the research conclusions more relevant to industrial application scenarios and offering stronger engineering reference value. Second, through a systematic approach combining “theory + experiment,” this study provides an in-depth analysis of the impact mechanism of imbalance on the SFD and rotor system, with a particular focus on validating the suppression effect of acceleration on imbalance excitation. This approach addresses the limitations of existing research that tends to focus solely on either theoretical analysis or experimental validation. Future research will further expand in the following directions, with a focus on exploring the effects of variable acceleration and deceleration processes on the dynamic characteristics of the rotor–SFD system. The goal is to refine the applicable boundaries of acceleration control strategies and provide a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for system design and operation in industrial scenarios.

8. Conclusions

Imbalance is a key hazard that induces excessive vibration in rotor systems and can even lead to structural failure, posing significant threats to the system’s operational safety and reliability. To clarify the influence mechanism of imbalance and explore vibration control pathways, this study combines numerical simulation and experimental research for systematic analysis. Firstly, the effect of eccentricity on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD is studied through numerical simulation, which indirectly reveals the influence mechanism of imbalance on the mechanical performance of the SFD. Based on this, a rotor–SFD system dynamic characteristic test rig is constructed. By altering the counterweight bolts, the influence of imbalance on the overall dynamic characteristics of the rotor system is directly studied. Finally, the regulation effect and mechanism of the acceleration parameters on the vibration response of the rotor system are further explored. Based on the above research, the following main conclusions are drawn:

- The imbalance of the rotor system leads to an increase in the eccentricity of the SFD. As the eccentricity increases, the pressure amplitude of the SFD increases, the range of the positive pressure zone shrinks, while the gas-phase volume and range both increase. As the eccentricity increases, the equivalent stiffness coefficient of the SFD increases significantly, while the increase in the equivalent damping coefficient is relatively small. This results in no significant enhancement of the vibration reduction effect of the SFD, but an enhancement of its nonlinear characteristics, leading to a decrease in the stability of the rotor system.

- The rotor dynamic characteristic tests revealed that as the imbalance increases, the stability of the rotor system decreases, and the vibration amplitude increases.

- Compared to the continuous acceleration mode, under the intermittent acceleration mode, the rotor vibration amplitude significantly increases due to the different dynamic balance loads the system experiences during the steady-state and acceleration transient phases. As the acceleration increases, the rotor system vibration amplitude decreases, allowing the system to pass through the critical speed region more quickly, thereby enhancing system stability. However, when the acceleration is too high, the rapid change in oil film thickness leads to increased system instability.

- Increasing the acceleration can effectively mitigate the vibration amplification effect caused by the increasing imbalance in the rotor–SFD system, especially under conditions of small imbalance.

This study focuses on the dynamic characteristics of the SFD, rotor system vibration response, and acceleration control mechanism under the influence of imbalance. By combining numerical simulation and experimental verification, the effects of imbalance and acceleration on the dynamic characteristics of the rotor system were investigated. The findings provide a reference for the selection of operational parameters for rotor systems, helping to ensure the long-term stability and efficient operation of the rotor system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y. and Y.F.; methodology, Z.Y. and J.L.; software, Z.Y.; validation, Z.Y. and J.L.; formal analysis, Z.Y.; investigation, Z.Y. and Y.S.; resources, Y.F.; data curation, Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y. and Y.S.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, Y.F.; project administration, Y.F.; funding acquisition, Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDC014002.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

| SFD | Squeeze Film Damper |

References

- Rodríguez, B.; San Andrés, L. Dynamic Forced Performance of an O-Rings Sealed Squeeze Film Damper Lubricated with a Low Supply Pressure and a Simple Method to Quantify Air Ingestion. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power Trans. ASME 2023, 246, 021004. [Google Scholar]

- San Andrés, L.; Den, S.; Jeung, S.H. On the Force Coefficients of a Flooded, Open Ends Short Length Squeeze Film Damper: From Theory to Practice (and Back). J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2018, 140, 012502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheller, E.; Chatterton, S.; Vania, A.; Paolo, P. Squeeze Film Damper Modeling: A Comprehensive Approach. Machines 2022, 10, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Singh, R.C. Development and Experimental Investigations of Squeeze Film Damper Setup for High Rotational Speeds and Oil Pressure. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 5475–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, V.; Behdinan, K.; Chan, D.; Beamish, D. Effect of Hole Feed System on the Response of a Squeeze Film Damper Supported Rotor. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Bin, G.F.; Lu, X.L.; Lu, Q.X.; Fang, H.; Pan, Y. Piezoelectric Driven Split Pad Squeeze Film Damper for the Suppression of Sudden Unbalanced Vibrations in Rotor System. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 578, 118331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, M.; Saksena, A.A.; Srivastava, A. Analysis of a Compact Squeeze Film Damper with Magneto-Rheological Fluid. Def. Sci. J. 2020, 70, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J.; Kim, J.; Steen, T. Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation to Squeeze Film Damper Analysis. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power Trans. ASME 2017, 139, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; San Andrés, L. A Model and Experimental Validation for a Piston Rings-Squeeze Film Damper: A Step Toward Quantifying Air Ingestion. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power Trans. ASME 2023, 145, 041012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheller, E.; Grigat, N.; Delgado, A.; Pennacchi, P. Multifrequency Response of a Squeeze Film Damper with Incipient Air Ingestion. Tribol. Trans. 2025, 68, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, B.B.; Li, X.; Sun, J.Q.; Ding, Q. Multiple-Objective Design Optimization of Squirrel Cage for Squeeze Film Damper by Using Cell Mapping Method and Experimental Validation. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 132, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, H.R.; Safarpour, P. Design and Modeling of a Novel Active Squeeze Film Damper. Mech. Mach. Theory 2016, 105, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-C.; Octaviani, S.; Najibullah, M.A. A Novel Hybrid Approach to the Diagnosis of Simultaneous Imbalance and Shaft Bowing Faults in a Jeffcott Rotor-Bearing System. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, G.; Wang, H.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.H. Bending-Torsion Coupling Vibrations of Dual-Disk Rotor System with Imbalance and Oil Film Bearings. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2025, 17, 16878132251330148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Feng, G.J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z.H. Development of an On-Shaft Vibration Sensing Module for Machine Wearable Rotor Imbalance Monitoring. Electronics 2024, 13, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, B.T.S.A.; Abdullah, M.N.; Mustapha, F.; Kanirai, N.S.A.; Mustapha, M. Vibration Analysis Using Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Networks for Rotor Imbalance Detection in Quadrotor UAV. Drones 2025, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q. Fault Detection and Classification of the Rotor Unbalance Based on Dynamics Features and Support Vector Machine. Meas. Control 2023, 56, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.M.; Bi, Y.J.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Cheng, X.H.; Meng, G.Y. Continuous Rotor Dynamics of Multi-Disc and Multi-Span Rotors: A Theoretical and Numerical Investigation of the Identification of Rotor Unbalance from Unbalance Responses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.U.; Aljibori, H.S.S.; Al-Tamimi, A.N.J.; Abdullah, O.I.; Senator, A.; Mohammed, M.N. A New Geometrical Design to Overcome the Asymmetric Pressure Problem and the Resulting Response of Rotor-Bearing System to Unbalance Excitation. Axioms 2023, 12, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Heng, X.; Wang, A.L.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q.S.; Liu, K. Analysis of Unbalance Response and Vibration Reduction of an Aeroengine Gas Generator Rotor System. Lubricants 2025, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, Z.H.M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.Y.; Han, Q.K. Flexible Rotor Unbalance Fault Location Method Based on Transfer Learning from Simulation to Experiment Data. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 125053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.L.; Sun, C.Z.; Lu, Q. Unbalance Prediction Method of Aero-Engine Saddle Rotor Based on Deep Belief Networks and GA-BP Intelligent Learning. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, H.C.; Wang, W.Y. Online Unbalance Compensation of a Maglev Rotor with Two Active Magnetic Bearings Based on the LMS Algorithm and the Influence Coefficient Method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 166, 108460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.L.; Zhai, L.J.; Shao, M.P. Unbalanced Vibration Suppression of a Rotor with Rotating-Frequency faults Using Signal Purification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 190, 110153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Hu, W.; Hu, R.; Chen, Z. Imbalance Fault Detection Based on the Integrated Analysis Strategy for Variable-Speed Wind Turbines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 116, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Hou, L.; Wang, S.; Lian, X. A Tacholess Order Tracking Method Based on the STFTSC Algorithm for Rotor Unbalance Fault Diagnosis Under Variable-Speed Conditions. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 24, 021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, A.R.; Gelman, L.; Ball, A.D. Novel Investigation of Influence of Torsional Load on Unbalance Fault Indicators for Induction Motors. Sensors 2025, 25, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ding, X.; Gong, Y.; Wu, N.; Yan, H. Rotor Imbalance Detection and Quantification in Wind Turbines Via Vibration Analysis. Wind. Eng. 2021, 46, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, M.; Bacha, K.; Chaari, A. Load Torque Effect on Diagnosis Techniques Consistency for Detection of Mechanical Unbalance. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Hammamet, Tunisia, 23 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ganeriwala, S. Loading Experimental Techniques, Rotating Machinery, and Acoustics, 1st ed.; River Publishers: Aalborg, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, A.R.; Gelman, L.; King, R.; Hickey, D.; Ball, A.D. A Novel Diagnostic Feature for a Wind Turbine Imbalance Under Variable Speed Conditions. Sensors 2024, 24, 7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, A.R.; Gelman, L.; King, R.; King, R.; Behzad, M.; Jha, P. Innovative Investigation of the Influence of a Variable Load on Unbalance Fault Diagnosis Technologies. Technologies 2025, 13, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinxing, M.A.; Hui, M.A.; Haiqin, Q.I.N.; Guo, X.; Zhao, C.; Yu, M. Nonlinear Vibration Response Characteristics of a Dual-Rotor-Bearing System with Squeeze Film Damper. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.B.; Zhao, Y.L.; Luo, Z.; Han, Q. Analysis on Influences of Squeeze Film Damper on Vibrations of Rotor System in Aeroengine. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Xiang, F.G.; Ren, G.M.; Gan, X.H. Dynamic Characteristics and Periodic Stability Analysis of Rotor System with squeeze Film Damper under Base Motions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabith, K.; Krishna, I.R.P. Influence of Squeeze Film Damper on the Rub-Impact Response of a Dual-Rotor Model. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 9051–9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CholUk, R.; ZhunHyok, Z.; ChungHyok, C.; Zhao, Q.; Ri, J.Y.; Kim, C.H. Optimization Design Analysis of the Eccentric Rotor System with SFD. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.J.; Yang, X.G.; Tang, G.; Zhang, Q.C.; Wang, G. Effect of Oil Film Radial Clearances on Dynamic Characteristics of Variable Speed Rotor with Non-Concentric SFD. Machines 2024, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Singh, R.C. Dynamic Response Experimental Analysis of High-Speed Rotors Equipped with Squeeze Film Dampers Under Varied Point Loading Conditions. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.F.; Cao, H.R.; Shi, J.H.; Pei, S.Y.; Li, H.X. Vibration Response Analysis of Rotor System Coupled with a Novel 4-DOF SFD Hydrodynamic Model Considering the Influence of Rotational Displacement. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.B.; Aghababaei, R.; Hong, J.; Pei, S.Y. An Efficient Method for Transient Response of Rotor Systems Based on Squeeze Film Damper. Tribol. Int. 2023, 183, 108277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ren, G.M.; Gan, X.H. Dynamic Behavior of a Flexible Rotor System with Squeeze Film Damper Considering oil-Film Inertia under Base Motions. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 3117–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Z.; Chen, Y.S.; Hou, L.; Li, Z.G. Bifurcation Analysis of Rotor-Squeeze Film Damper System with Fluid Inertia. Mech. Mach. Theory 2014, 81, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.J.; Li, X.M.; Ling, L.Y.; Qu, H.Y. Dynamic Modeling and response Analysis of Rub-Impact Rotor System with Squeeze Film Damper under Maneuvering Load. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 114, 544–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Lan, X.F.; Zeng, S.; Feng, Z.C.; Qian, P.H.; Wang, F. The Impact of Squeeze Film Damper and Support Nonlinear Forces on the Dynamic Response of High-Speed Flexible Rotors. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, S.H.; EI-Shafei, A. Momentum and Energy Approximations for Elementary Squeeze-Film Damper Flows. J. Appl. Mech. Trans. ASME 1993, 60, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeri, A.Z.; Raimondi, A.A.; Giron-Durate, A. Linear Force Coefficients of Squeeze Film Dampers. J. Lubr. Technol. Trans. ASME 1983, 105, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Simulation and Experimental Study on Dynamic Characteristics of Squeeze Film Damper; Shenyang Aerospace University: Shenyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.L.; Cang, Y.G.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Guo, C. Analysis of Dynamic Characteristics of A Sealed Ends Squeeze Film Damper Considering the Fluid Inertia Force. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2023, 3, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Luo, Z.; Han, Q.K. Navigating the Dynamics of Squeeze Film Dampers: Unraveling Stiffness and Damping Using a Dual Lens of Reynolds Equation and Neural Network Models for Sensitivity Analysis and Predictive Insights. Mathematics 2024, 12, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).