Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2), the primary anthropogenic greenhouse gas, drives significant and potentially irreversible impacts on ecosystems, biodiversity, and human health. Achieving the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to well below 2 °C, ideally 1.5 °C, requires rapid and substantial global emission reductions. While recent decades have seen advances in clean energy technologies, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) remain essential for deep decarbonization. Despite proven technical readiness, large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) deployment has lagged initial targets. This review evaluates CCS technologies and their contributions to net-zero objectives, with emphasis on sector-specific applications. We found that, in the iron and steel industry, post-combustion CCS and oxy-combustion demonstrate potential to achieve the highest CO2 capture efficiencies, whereas cement decarbonization is best supported by oxy-fuel combustion, calcium looping, and emerging direct capture methods. For petrochemical and refining operations, oxy-combustion, post-combustion, and chemical looping offer effective process integration and energy efficiency gains. Direct air capture (DAC) stands out for its siting flexibility, low land-use conflict, and ability to remove atmospheric CO2, but it’s hindered by high costs (~$100–1000/t CO2). Conversely, post-combustion capture is more cost-effective (~$47–76/t CO2) and compatible with existing infrastructure. CCUS could deliver ~8% of required emission reductions for net-zero by 2050, equivalent to ~6 Gt CO2 annually. Scaling deployment will require overcoming challenges through material innovations aided by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, improving capture efficiency, integrating CCS with renewable hybrid systems, and establishing strong, coordinated policy frameworks.

1. Introduction

The growing global population continuously drives higher energy demand and consumption. In 2024, global energy demand increased by 2.2%, surpassing the annual average of 1.3% observed between 2013 and 2023 [1]. This uptick was partly due to extreme weather events, which added 0.3 percentage points to the growth rate. Electricity demand grew even more rapidly, rising by 4.3% in 2024, the largest increase ever recorded, reflecting structural trends such as growing access to electricity-intensive appliances, a shift towards electricity-intensive manufacturing, and increasing power demand from digitalization, data centers, artificial intelligence, and the electrification of end-uses. The power sector accounted for three-fifths of the total increase in global energy demand [1].

Global Energy Consumption, CO2 Emissions and CCS Technologies

Global energy consumption is strongly influenced by developments in Asia, with China and India serving as major contributors to the rising demand. China alone accounted for 50% of the global electricity demand growth in 2024, and, while its demand growth is expected to moderate in 2025, it remains a dominant force in the energy landscape [2]. Similarly, India is experiencing rapid urbanization and industrialization, leading to increased energy consumption (Resources for the Future) [3].

Despite the accelerating shift towards renewable energy sources, fossil fuels: oil, gas, and coal are projected to continue dominating global energy consumption beyond 2050. A recent report from McKinsey forecasts that fossil fuels will comprise 41–55% of the energy mix in 2050, down from the current 64%, but still higher than earlier predictions. This persistence of fossil fuels poses significant challenges for achieving net-zero emissions targets [4].

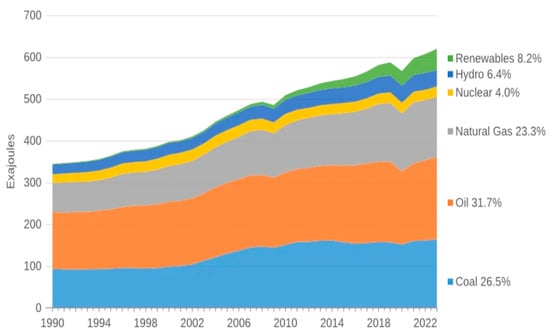

The 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy by the Energy Institute in Figure 1 [5] indicates that fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, still dominate energy production and use worldwide. Global consumption of fossil fuels hit a new peak of 505 exajoules (EJ), increasing by 1.5%, with coal rising by 1.6%, oil growing by 2% surpassing 100 million barrels per day for the first time, while natural gas consumption remained steady. Fossil fuels accounted for 81.5% of total primary energy supply, a slight decline from 81.9% in the previous year. Meanwhile, energy-related emissions grew by 2%, surpassing 40 gigatonnes of CO2 for the first time. CO2, a principal greenhouse gas mainly emitted from burning fossil fuels, has increased sixfold since 1950 due to human activities [6].

Figure 1.

The Energy Institute’s 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy global energy consumption [5].

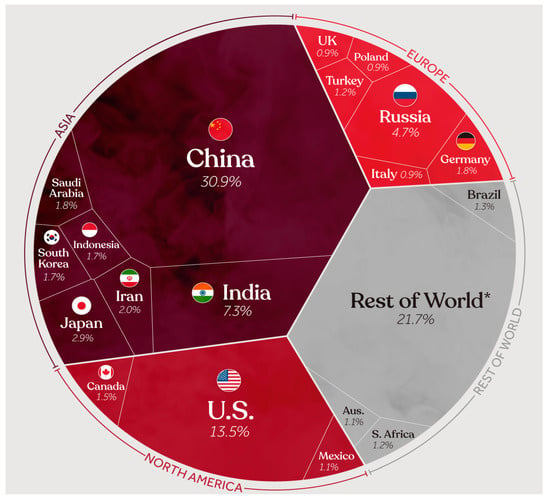

The continuous burning of fossil fuels has led to significant increases in CO2 emissions in the atmosphere, as illustrated in Figure 2. As of 2024, atmospheric CO2 concentrations have reached approximately 430 parts per million (ppm), the highest in human history, underscoring the urgency of implementing carbon mitigation strategies such as Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) [7].

Elevated CO2 concentrations contribute to serious environmental issues, including global warming, acid rain, degradation of ecosystems, and deforestation. According to projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), if greenhouse gas emissions such as CO2 are not actively reduced, the average global surface temperature could rise between 1.8 °C and 4.0 °C this century, potentially reaching as high as 6.4 °C under the most severe scenario [8].

Figure 2.

World’s carbon emissions 2021 [9]. The * refers to 175 countries.

Climate change represents one of the most significant anthropogenic threats faced globally, profoundly impacting political, social, and economic systems. The challenges posed are multifaceted and severe, involving substantial risks, economic uncertainties, contested scientific findings, complex governance issues, and profound psychological and societal effects. These impacts extend beyond environmental domains, influencing various interconnected sectors. Effective public health strategies and policy interventions are essential to address current and future pollution and climate-related challenges. The critical question remains whether responses should prioritize mitigation by reducing carbon emissions from economic activities or adaptation to the inevitable consequences of climate change [10].

The influence of climate change on meteorological patterns and environmental phenomena is extensively documented [10]. It disrupts established climate regimes, leading to more frequent and intense extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, rising sea levels, altered precipitation cycles, cold spells, heavy rainfall, floods, storms, droughts, snowstorms, tropical cyclones and changes in oceanic patterns including sea level rise and freshwater inflows [11,12]. These extreme events produce severe, interconnected consequences, contributing to increased mortality, injuries, and outbreaks of infectious diseases [10]. Climate change impacts manifest both directly, through events like heatwaves and storms, and indirectly, via ecosystem alterations that reduce agricultural productivity, exacerbate food insecurity and malnutrition, degrade air quality, and modify disease transmission patterns. Socioeconomic repercussions include population displacement, migration, mental health disorders, and conflicts [13]. Additional consequences include rising ocean temperatures and acidification, pollution of air and water resources, and increased incidence of wildfires [14].

Robust scientific evidence attributes numerous changes in the Earth’s climate system to human-induced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Since the onset of the Industrial Revolution in 1760, atmospheric GHG concentrations have steadily increased, primarily due to fossil fuel combustion, industrial activities, deforestation, and agriculture [15]. Elevated levels of CO2 and other GHGs have already triggered higher global temperatures, intensified floods and droughts, and increased the frequency and severity of tornadoes and tropical storms. If the persistent rise in atmospheric CO2 is not curtailed, it risks crossing critical thresholds leading to catastrophic events such as drastic changes in ocean circulation, accelerated sea-level rise, and the melting of glaciers and polar ice caps, with dire consequences for humanity [15].

Therefore, reducing CO2 emissions alongside the implementation of carbon capture and sequestration technologies is essential for climate change mitigation. Such efforts can limit detrimental effects like sea-level rise, extreme weather events, and ecological disruptions. Moreover, decreasing carbon emissions improves air quality, thereby enhancing public health outcomes and contributing to socio-economic stability.

Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) encompasses the process of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from large stationary sources like power generation plants and industrial installations. The captured CO2 is then transported commonly through pipelines, ships, or trucks to specific storage locations, where it is securely injected into deep geological formations underground, ensuring long-term containment and preventing atmospheric release. The fundamental concept behind CCS is to intercept CO2 produced during fossil fuel combustion before atmospheric emission occurs. A key challenge is the management of the captured CO2, with prevailing strategies focusing on deep geological injection, effectively creating a “closed carbon loop” where carbon extracted as fossil fuels is ultimately returned underground in gaseous form. Currently, CCS operations sequester approximately 45 million tonnes of CO2 annually, equivalent to emissions from around 10 million passenger vehicles. Capture predominantly occurs at large, fixed emission sources such as power generation plants and industrial producers of cement, steel, and chemicals. Most existing CCS projects employ liquid solvents to chemically absorb CO2 prior to its release from smokestacks, although novel capture technologies are under active development [16].

CCS technologies facilitate substantial reductions in gross CO2 emissions and form a critical basis for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods. These methods enable the compensation of both historic and residual emissions by achieving net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. Natural carbon sinks alone are insufficient to offset residual emissions, necessitating engineered solutions such as bioenergy combined with CCS (BECCS), which captures CO2 from biomass-derived processes, and direct air capture (DAC) or ocean-based direct capture technologies. CDR approaches are frequently characterized as “negative emissions” or “climate-positive” strategies. Robust analyses of pathways toward net-zero emissions underscore the importance of deploying a diverse suite of technologies. Both CCS and CDR are integral to achieving net-zero targets, complementing other sustainable measures within a coordinated global decarbonization framework by mid-century [17].

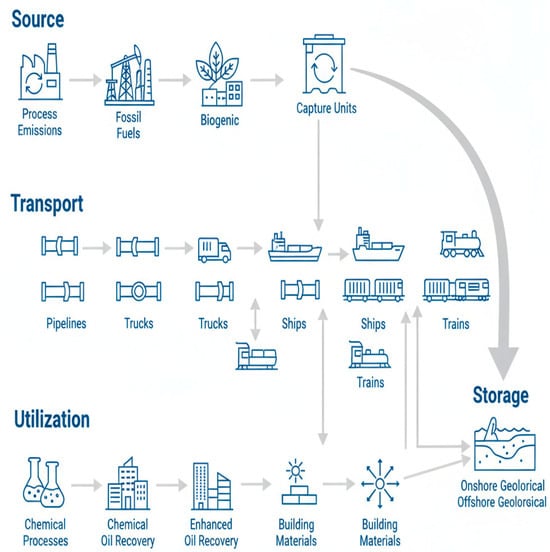

Figure 3 presents a simplified depiction of the Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) process, outlining the entire sequence of CO2 handling from its initial release at emission points to its secure, long-term sequestration in subterranean geological formations.

Figure 3.

An overview of the CCS value chain.

The CCS process begins with the generation of CO2 from diverse sources such as industrial process emissions, fossil fuel combustion, and biogenic origins like biomass. These sources constitute significant contributors to human-induced CO2 emissions and are primary targets for capture within climate mitigation frameworks.

CO2 capture occurs at industrial or power generation facilities using various technologies, including membrane separation, chemical absorption and cryogenic techniques. The objective is to separate and compress CO2 to enable efficient transportation to storage sites. Chemical absorption, often employing aqueous amine solvents, has been extensively used for CO2 removal from natural gas and forms the basis for commercial post-combustion capture plants such as the Boundary Dam [18,19] and Petra Nova facilities [20,21]. Commercially available membrane technologies, like the Polaris membrane, have been successfully applied to CO2 separation from syngas [22]. Additionally, Air Products licenses a polymeric membrane developed at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), applicable to coal-fired plants and other combustion sources [23].

Captured CO2 is transported through pipelines, ships, trucks, or trains. Pipelines are the preferred transport mode for large-scale operations due to their cost efficiency and reliability, while shipping and other land transport methods are employed where pipelines are impractical or for smaller projects. Globally, there are over 6500 km of CO2 pipelines, mainly supporting CO2-enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations in the United States [24]. Ship-based CO2 transport technologies are also well developed and operational in commercial settings [25].

The final stage involves injecting CO2 into geological formations onshore or offshore for long-term sequestration. Suitable storage reservoirs include depleted oil and gas fields and deep saline aquifers, capable of securely retaining CO2 for millennia and preventing atmospheric release. CCS thus plays a crucial role in reducing emissions from sectors that are challenging to decarbonize. Presently, CO2-EOR is integrated into 13 of the 17 active commercial CCS projects. Saline aquifers are also utilized for storage in notable projects such as Sleipner, Snohvit, and Quest. Conversely, enhanced gas recovery (EGR) [26] and CO2 storage in depleted oil and gas fields have yet to be demonstrated at commercial scale. Alternative storage methods, including oceanic and mineral storage, remain in early development phases.

Several facilities currently utilize captured CO2 for various industrial applications, primarily within the food and beverage sector, as well as in chemical manufacturing processes such as urea and methanol production [27]. For example, mineral carbonation is being pursued at the Searles Valley facility in the United States, while in Saga City, Japan, CO2 recovered from waste incineration is repurposed to enhance the growth of crops and algae [28]. Most of the CO2 used in these projects originates from industrial sources including fertilizer, ammonia, and ethylene glycol plants, though some initiatives also capture CO2 directly from power plant flue gases [27].

Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 is one of the most promising carbon utilization pathways within Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) systems, offering a viable route to synthesize sustainable fuels and value-added chemicals while contributing to a circular carbon economy. This process not only mitigates atmospheric CO2 emissions but also transforms CO2 from an environmental liability into a chemical feedstock for industrial use. Recent reviews have highlighted that CO2 hydrogenation enables the direct conversion of captured CO2 into high-value products such as methanol, hydrocarbons, and olefins using renewable hydrogen, thereby closing the anthropogenic carbon loop and reducing reliance on fossil resources [29]. As renewable energy capacity expands globally, green hydrogen derived from water electrolysis using solar or wind power provides a clean reducing agent for CO2 conversion, further enhancing the sustainability of this pathway.

Two mechanistic pathways dominate the reaction process depending on catalyst design and operating conditions. The first involves the reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) pathway, which converts CO2 to CO, followed by Fischer–Tropsch synthesis to form long-chain hydrocarbons suitable for synthetic fuels [30]. This pathway is particularly attractive for producing drop-in fuels compatible with existing transportation infrastructure. The second pathway is direct CO2 hydrogenation via surface-bound formate or methoxy intermediates to generate methanol, commonly using Cu-, In-, or Ga-based catalytic systems known for their high selectivity and industrial relevance [31]. Methanol serves as a versatile platform molecule that can be converted to gasoline, dimethyl ether (DME), and olefins, making it central to CO2 valorization chemistry.

Advances in catalyst design, particularly the development of alloyed, interfacial, and bifunctional catalysts, have significantly enhanced CO2 activation, intermediate stability, and product selectivity by modifying metal support interactions and introducing oxygen vacancies that promote adsorption and dissociation of CO2 molecules [32]. The incorporation of reducible oxide supports such as CeO2 and ZrO2 has been shown to improve catalytic performance by facilitating hydrogen spillover and stabilizing active metal nanoparticles. Moreover, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have recently been applied to accelerate catalyst discovery and optimize reaction conditions by enabling high-throughput screening of catalyst descriptors, predicting active site properties, and guiding microkinetic modeling [33].

Beyond methanol synthesis, emerging research explores CO2 hydrogenation to complex fuels and chemicals such as aviation kerosene, aromatics, and ethanol using zeolite-integrated catalytic systems, tandem catalysis, and multifunctional reactor designs that enhance carbon–carbon coupling efficiency [34]. These advances open new pathways for producing carbon-neutral fuels for hard-to-abate sectors like aviation and shipping. Despite this progress, major challenges remain, including catalyst deactivation due to sintering and carbon deposition, thermodynamic limitations at low reaction temperatures, and the large energy demand associated with renewable hydrogen production. Recent studies highlight the growing importance of reactor engineering and process intensification strategies such as sorption-enhanced hydrogenation, structured catalysts, microchannel reactors, and membrane-assisted hydrogenation—to overcome equilibrium constraints and enhance CO2 conversion efficiencies [35,36]. Overall, CO2 hydrogenation is a cornerstone of carbon utilization strategies and represents a crucial technology for net-zero transition when integrated with CCUS infrastructure, renewable hydrogen production, and AI-driven catalytic innovation.

Despite extensive research on CCS technologies, there remains a significant gap in comprehensive analyses that combine techno-economic assessments with sector-specific applications to optimize CCS deployment across diverse industries. Furthermore, challenges associated with integrating CCS alongside renewable energy and negative emissions technologies such as BECCS are underexplored, particularly regarding cost, scalability, and supportive policy frameworks. Additionally, more in-depth investigations are needed into real-world case studies that assess the long-term performance, safety, and economic viability of CCS projects across various geographic and industrial contexts. Key research gaps in AI-enhanced CCUS include limited real-time data integration, insufficient predictive models for complex CO2 capture and storage processes, and challenges in optimizing multi-scale system performance. There is also a need for standardized frameworks to evaluate AI-driven CCUS solutions. Integrating AI is crucial as it can enhance process efficiency, reduce operational costs, improve monitoring and risk management, and enable data-driven decision making across capture, utilization, and storage operations.

Nevertheless, CCS represents a complex but essential suite of technologies that, when effectively integrated, can play a pivotal role in achieving global net-zero emission targets and mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change.

This manuscript seeks to explore advances, assess implementation challenges, and envision future perspectives synergizing CCUS and AI. It presents a thorough analysis of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies, emphasizing their critical contribution to global decarbonization initiatives. It reviews recent technological advancements spanning the entire CCS value chain, from CO2 capture at various emission sources to transportation logistics and secure long-term geological storage. Through detailed case studies, the manuscript evaluates real-world applications, highlighting cost estimates and economic feasibility across different CCS technologies. It also addresses the technical, financial, and policy challenges limiting widespread adoption while showcasing innovative approaches and emerging trends aimed at improving CCS efficiency, safety, and scalability. Additionally, the integration of CCS with complementary low-carbon hydrogen and renewables such as wind, solar, geothermal biofuel production and negative emissions technologies like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is examined to assess CCS’s potential role in achieving net-zero emissions and mitigating climate change.

This manuscript contributes to the growing body of literature on climate change mitigation by providing a comprehensive and interdisciplinary analysis of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies, with a particular emphasis on cost evaluation, performance, and deployment feasibility. It systematically compares various CCS approaches, including post-combustion, pre-combustion, oxy-fuel combustion, and direct air capture (DAC), highlighting their cost ranges, technological maturity, energy requirements, and integration potential. The manuscript further discusses the role of CCS within specific industrial sectors: post-combustion CCS and oxy-combustion exhibit the highest CO2 capture efficiency in the iron and steel industry, while cement production can be best decarbonized by oxy-fuel combustion, calcium looping and emerging direct capture technologies to address process-related emissions. In the petrochemical and refining sectors, oxy-combustion, post-combustion, and chemical looping combustion could provide effective pathways for process integration and improved energy efficiency, illustrating the need for tailored CCS applications to sector-specific decarbonization challenges.

Through detailed case studies, the economic viability of each method is critically assessed, identifying post-combustion capture as a relatively cost-effective solution for retrofitting existing power plants, while acknowledging that DAC, despite currently higher costs, shows potential for cost reduction through innovation and scaling. The analysis also evaluates technical advantages and limitations, such as the operational complexity associated with oxy-fuel combustion and the infrastructural demands of pre-combustion systems. Additionally, the study explores synergies between CCS and low-carbon energy systems, including renewables and negative emissions technologies like BECCS, offering a holistic view of CCS’s potential role within broader decarbonization pathways. The manuscript also outlines the technological, policy, and investment challenges that must be addressed to accelerate widespread CCS adoption. By integrating techno-economic assessments with policy and system-level considerations, it provides actionable insights to inform strategic decision making for large-scale CCS deployment and long-term climate policy development.

2. Technological Advances in Carbon Capture Technologies

2.1. Pre-Combustion Capture

Pre-combustion carbon capture primarily targets removing CO2 from fossil or biomass fuels before they are combusted for energy production. This approach is commonly utilized during the gasification of coal, natural gas, or biomass to generate synthesis gas (syngas), as well as in natural gas-fired power plants [37]. In a standard pre-combustion capture process, the fuel is gasified to produce syngas composed primarily of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. The CO2 is then separated from the syngas prior to its use in driving turbine generators for electricity generation [38]. Applications of pre-combustion capture extend beyond power generation to hydrogen production for clean energy and chemical feedstock production.

The overall sequence is illustrated in Figure 4. Post-combustion capture technologies generally fall into four categories: solvent-based, sorbent-based, membrane-based, and emerging novel methods [37].

Pre-combustion CO2 capture is a core component of Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) plants, which support low-carbon electricity and hydrogen production (as depicted in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Process diagram carbon capture and compression for an IGCC power plant [37].

This method offers advantages such as easier, less energy-intensive CO2 separation due to its high concentration and pressure but tends to be more complex and costly, usually implemented in new plant constructions or specialized facilities [39]. Captured CO2 from pre-combustion processes follows various utilization and storage paths. Utilization includes converting CO2 into chemical feedstocks such as methanol and synthetic fuels, enhanced oil recovery (EOR), where CO2 is injected to boost oil extraction with AI optimizing injection and risk prediction, and permanent mineralization by converting CO2 into stable carbonates aided by machine learning for material optimization [40].

Storage primarily involves injecting CO2 into deep geological formations like depleted oil and gas reservoirs or saline aquifers with high porosity and impermeable cap rocks for long-term containment [41]. Continuous AI-empowered monitoring using seismic surveys, pressure sensors, and satellite imaging ensures early leak detection [40]. Innovations accelerating this field include AI-designed advanced solvents and sorbents for better capture efficiency, AI-driven process optimization, modular scalable plant designs, machine-learning-enhanced gas separation membranes, and lifecycle economic modeling to improve cost-effectiveness [38,40]. The co-production of hydrogen further enhances the economic viability of pre-combustion carbon capture systems [42].

Pre-combustion capture faces challenges in scaling down to modular applications while keeping costs low. Improvements are needed in solvents, sorbents, and membranes to enhance capacity, selectivity, and durability. Integrated and hybrid processes combining different capture methods show promise for efficiency gains. Thermodynamic and economic optimizations are essential for practical deployment. Focus on modular design, advanced materials, and hybrid systems and AI-optimized operations can drive future advancements.

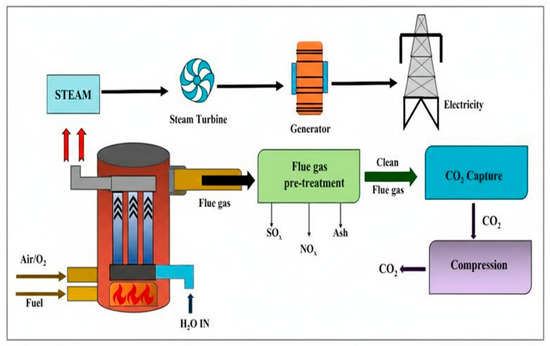

2.2. Post-Combustion Capture

Post-combustion CO2 capture is a well-established method widely employed in power plants that generate electricity or heat by burning fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, or oil, while simultaneously reducing CO2 emissions. During combustion, hot flue gas is produced containing approximately 3–20% CO2 by volume (partial pressure ~0.03–0.20 bar) at temperatures exceeding 400 °C [43]. This flue gas is initially cooled using heat exchangers or cooling towers to create optimal conditions for efficient CO2 capture. As illustrated in Figure 5, the removal of CO2 from the flue gas predominantly involves adsorption, absorption, and membrane separation techniques [44]. The captured CO2 is subsequently compressed and conveyed through pipelines, ships, or trucks to specific storage locations. Meanwhile, the steam produced during the process is utilized to power turbines for electricity generation. Coal combustion also generates multiple pollutants, including fly ash, hazardous gases, trace elements like mercury (Hg), sulfur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and non-condensable gases such as oxygen (O2). Effective removal of these pollutants is essential before releasing the flue gas into the atmosphere to comply with environmental protection standards [45].

The primary distinctions between pre-combustion and post-combustion capture lie in the separation technologies employed and the composition of the flue gas. The selection of either method depends largely on implementation costs and the specific characteristics of the power plant or industrial process [46].

Recent reviews highlight advancements in developing novel solvents and sorbents with higher CO2 capacity and lower energy requirements, enhanced membrane materials for improved selectivity and permeability, and hybrid techniques combining these methods for optimized capture [47,48]. Additionally, chemical looping technologies that separate CO2 via solid oxygen carriers are emerging as promising alternatives with potentially lower energy consumption [42,49]. The utilization pathways for captured CO2 include transforming it into valuable chemical feedstocks such as methanol, urea, and polymers, where AI-driven catalyst development is accelerating process efficiency [47,49]. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) remains a significant commercial use, injecting CO2 into oil reservoirs to boost production while permanently storing CO2 underground, with AI optimizing injection parameters and monitoring reservoir dynamics to mitigate risks [42,49]. Mineralization processes convert CO2 into stable carbonate minerals for permanent storage, aided by machine learning models predicting material properties and reaction kinetics [48]. Geological storage involves injecting CO2 into deep underground formations like depleted oil and gas fields, saline aquifers, and coal seams, with site selection based on geological stability, storage capacity, and impermeable caprock presence [42,50]. Continuous monitoring and verification use seismic surveys, pressure and chemical sensors, satellite imaging, and increasingly AI-based anomaly detection to ensure storage integrity and early leak detection [47,48,51]. Current innovations include AI-assisted solvent and sorbent design for increased capture efficiency and decreased regeneration energy demand, process optimization and predictive maintenance to reduce operational costs, modular and scalable system designs enhanced through AI-driven modeling, and lifecycle economic assessments integrating AI to optimize deployment strategies [49,52]. These advancements collectively improve the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of post-combustion carbon capture as a critical component in decarbonization efforts [47,51].

Post-combustion capture is valued for its operational flexibility and simplicity, as it can be retrofitted to existing power plants at the stack without disrupting upstream processes, which is one of its key advantages [53]. However, challenges include developing adsorbents with high CO2 capacity, selectivity, and long-term cyclic stability, lower capture efficiency and energy-intensive capture and regeneration steps, leading to limited overall performance and increased operational costs. Consequently, achieving higher-purity CO2 streams necessitates larger-scale equipment and infrastructure, which further raises costs [54,55]. Energy-intensive sorbent regeneration and maintaining sorbent integrity are major hurdles. Optimization of gas–solid contacting systems (e.g., fixed and fluidized beds) is needed to improve capture efficiency. Innovative regeneration strategies to reduce energy consumption are crucial. Advancements in advanced adsorbent materials, system design, and process optimization, and AI-optimized operations can enhance economic and operational viability of post-combustion capture.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of various steps involved in post-combustion capture [55].

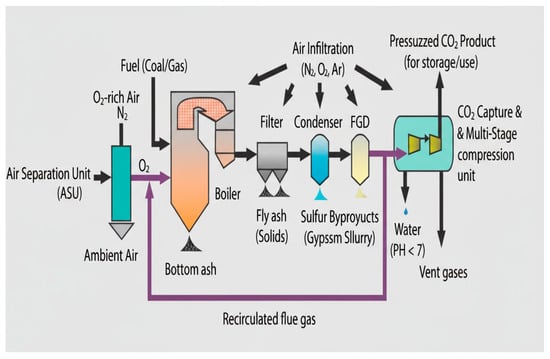

2.3. Oxy-Fuel Combustion

Among the various carbon capture technologies, oxy-fuel combustion is considered highly promising due to its potential for integration with existing power plants with minimal modifications, as well as its applicability in new plant designs. Two primary methods for implementing oxy-fuel combustion are the air separation unit (ASU) and the ion transport membrane reactor (ITMR) approaches [56]. In the ASU method, oxygen is separated from air and subsequently used to oxidize fuel within conventional combustion systems, as illustrated in Figure 6. Flue Gas Desulfurization (FDG) is employed to remove sulfur oxides (SOx) from flue gas prior to CO2 capture, preventing equipment corrosion, minimizing environmental pollution, and ensuring high CO2 purity. The process typically uses sorbents like limestone or lime, producing byproducts such as gypsum that can be safely utilized. HG (Heavy Gas or fly ash) represents the solid particulate matter filtered from the flue gas, which can be reused in materials like cement or safely disposed of. After condensation, the resulting HG++ (Highly Concentrated Heavy Gas Fraction) stream contains residual particulates and sulfur compounds, effectively separating heavy components from the CO2-rich gas and facilitating more efficient capture, compression, and storage. This oxygen separation via cryogenic or membrane techniques, however, requires additional energy input.

In contrast, the ITMR method integrates oxygen separation and combustion processes within a single unit. Oxygen transport membrane reactors (OTMRs) utilize ion transport membranes (ITMs) that enable oxygen to permeate at high temperatures ranging from 650 to 950 °C.

Oxygen transport through an ion transport membrane (ITM), also called a mixed ionic–electronic conducting (MIEC) membrane, occurs through a selective high-temperature diffusion process driven by an oxygen partial pressure gradient. The membrane is made of dense ceramic oxides (often perovskites) that conduct both oxygen ions (O2−) and electrons. On the feed side of the membrane, oxygen molecules from air first adsorb onto the membrane surface, dissociate into atoms, and then each atom gains electrons to form oxygen ions (O2−). These ions migrate through the membrane crystal lattice via oxygen vacancies, while electrons move in the opposite direction through the electronic conduction pathway to maintain charge balance. When the ions reach the permeate side, they release electrons, recombine into oxygen molecules, and are delivered as pure oxygen or used directly for oxy-fuel combustion. The process is driven entirely by the difference in oxygen partial pressure, eliminating the need for an external power source for separation, unlike cryogenic air separation. ITMs operate efficiently at temperatures between 700–1000 °C, and when integrated into oxy-fuel combustion systems, they enable nitrogen-free combustion, producing a flue gas rich in CO2 and H2O that is easier to capture for carbon sequestration. However, challenges such as membrane material degradation in CO2-rich environments, sealing at high temperatures, and mechanical stability remain active research areas [57,58].

A variety of membrane materials have been investigated for oxy-fuel combustion applications, including lanthanum cobaltite-based perovskite ceramics, modified perovskite ceramics [57], and ceramics with a brownmillerite structure [58]. Furthermore, advanced thin dual-phase membranes, such as chemically stable yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), metal-carbonate dual-phase membranes, and ceramic-metal dual-phase membranes, have also been developed to enhance performance [59].

Future oxy-fuel combustion technologies under investigation encompass syngas production via ITMs, integration of oxy-combustion with oxygen transport reactors (OTRs) for power generation, utilization of liquid fuels during combustion, and the development of third-generation technologies aimed at enhancing CO2 capture efficiency [60,61].

Figure 6.

Oxy-fuel combustion [61].

This technology is gaining traction in industries like cement production (e.g., Holcim’s Obourg plant in Belgium) and power generation, where it offers higher combustion efficiency and easier CO2 capture compared to conventional combustion [62].

Captured CO2 from oxy-fuel combustion can be utilized in chemical feedstocks, enhanced oil recovery (EOR), or permanently stored through mineralization [52]. Geological storage involves injecting CO2 into deep formations like depleted oil and gas reservoirs, saline aquifers, and coal seams with suitable porosity and impermeable cap rocks [63]. Site selection and risk assessments consider storage capacity, geological stability, and potential leakage pathways. State-of-the-art projects incorporate continuous monitoring with seismic surveys, pressure sensors, and increasingly AI-enabled anomaly detection to ensure safe long-term storage [52]. Recent innovations accelerating efficiency and cost-effectiveness include advanced burner designs, improved oxygen generation technologies, heat recovery improvements, modular system configurations, and AI-driven process optimization and maintenance. Regulatory support and growing market demand further foster the adoption of oxy-fuel combustion combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS), promising near-zero emissions for industrial sectors [62].

Oxy-fuel combustion carbon capture faces challenges of high energy use, material degradation, combustion inefficiencies, high costs, and scale-up issues, which can be addressed through advanced oxygen production, durable materials, optimized design, process integration, and AI-enhanced operations.

A major limitation of oxy-fuel combustion is the high cost associated with producing pure oxygen to replace air in the combustion process. Industrial oxygen is primarily produced through cryogenic air separation, a process characterized by high energy consumption and capital costs. This oxygen production can represent as much as 50–70% of the total incremental cost of an oxy-fuel system. Yuan et al. (2024) report that the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for oxy-fuel combustion systems is substantially higher than conventional systems, with CO2 avoidance costs potentially exceeding USD 40 per tonne, reducing economic viability in markets lacking carbon pricing mechanisms [64].

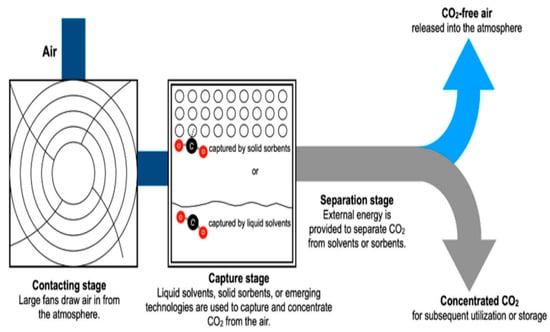

2.4. Direct Air Capture (DAC)

Direct air capture (DAC) is a process that extracts CO2 directly from ambient air using chemical means. Large volumes of air are passed through a DAC system containing a sorbent material designed to selectively bind CO2 molecules, as illustrated in Figure 7. In a subsequent stage, the captured CO2 is released from the sorbent and collected for either utilization or long-term storage. Currently, two primary DAC technologies dominate the field: systems utilizing solid sorbents and those employing liquid sorbents [65]. Solid sorbent DAC employs highly porous materials with extensive surface area to adsorb CO2, whereas liquid sorbent DAC uses chemical solutions to absorb CO2.

While existing DAC systems require both heat and electricity to operate components such as rotating equipment, solid sorbent DAC (S-DAC) can potentially run entirely on electricity, which may be sourced from renewables. In contrast, liquid sorbent DAC (L-DAC) typically requires an external heat source, commonly natural gas, to reach the high temperatures (approximately 900 °C) necessary in the regeneration calciner. Without the availability of a low-carbon heat source, which is not yet commercially viable, reliance on natural gas would necessitate capturing and storing its associated CO2 emissions along with the CO2 extracted from the air to ensure maximal net carbon removal [66].

DAC technology, originally developed in the late 1950s for applications such as submarines and spacecraft, has matured significantly. Presently, about 130 DAC plants are operational or under construction globally, with leading developers including Global Thermostat (Atlanta, GA, USA), Carbon Engineering (Squamish, BC, Canada), and Climeworks (Zurich, Switzerland). Recent progress has focused on optimizing sorbent materials to enhance CO2 capture efficiency [67].

Figure 7.

Direct Air Capture [68].

DAC is distinguished by its ability to offset diffuse historical and industrial emissions not captured at their sources, making it essential for net-zero carbon targets [69]. Modular plant designs and low-temperature heat regeneration processes are advancing the technology, enhancing operational flexibility and reducing energy consumption [70]. DAC systems increasingly integrate AI for process optimization, material discovery, and real-time monitoring to improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness [71]. Commercial-scale projects like 1PointFive’s facility in Texas are expected to significantly expand capacity in the near term, underscoring the scaling potential of DAC [72].

Utilization pathways for captured CO2 include converting it into chemicals and synthetic fuels, while geological storage primarily relies on underground injection with careful site selection based on geological stability and cap rock integrity. Enhanced monitoring with AI-enabled anomaly detection and satellite technologies improves storage security [71]. Recent innovations accelerating the field include advanced absorbent materials, integration of renewable energy to reduce DAC’s carbon footprint, modular plant architectures for scalable deployment, and AI-driven lifecycle and economic modeling [69]. Despite current challenges such as high energy intensity and costs, ongoing technological improvements and supportive policy frameworks are expected to make DAC a critical tool for large-scale carbon removal, capable of contributing several gigatons of CO2 removal annually by 2050 to meet climate goals [73].

Direct air carbon capture is limited by low CO2 levels, high energy use, sorbent degradation, high costs, and lack of large-scale validation, which can be addressed through advanced materials, energy-efficient designs, modular systems, and AI-optimized operations.

Direct air capture (DAC) technology offers flexible deployment options, functioning effectively in diverse environments including deserts, urban settings, and proximity to renewable energy or storage sites, without dependence on emission sources or competition for agricultural land. DAC systems are highly scalable, ranging from small, decentralized units to large, centralized facilities capable of capturing millions of tonnes of CO2 annually [74].

Electrochemical redox-based methods for Direct Air Capture (DAC) of CO2 have emerged as a promising alternative to conventional thermochemical or sorbent-regeneration approaches, particularly because they offer potential for lower energy consumption, modularity, and coupling with renewable electricity. In these systems, a redox-active material or electrode undergoes a reversible electron-transfer (and often proton-transfer) process that changes its affinity for CO2 (or (bi)carbonate) under ambient conditions: for example, a material in its oxidized state captures CO2 (or promotes CO2 uptake) and upon electrochemical reduction (or oxidation) it releases the CO2, thereby closing the cycle [75]. Some configurations operate via a pH-swing mechanism where electrochemistry is used to shift pH in a capture solution, thereby converting bicarbonate/carbonate into dissolved CO2, which can then be released. Others use direct redox-mediated absorption/desorption: redox-active molecules (such as quinones, phenazines, or bipyridines) change oxidation state and bind CO2 in one state and release it in the other. The process is powered by electricity (preferably renewable), functioning at ambient pressure and often near ambient temperature, and thereby avoids the large thermal regeneration penalty of traditional DAC.

One example is the electrochemical DAC process using the redox couple neutral red, achieving CO2 capture energy as low as ~65 kJ mol−1 CO2 [76]. Another recent analysis evaluated the sustainability and cost of several fully electrified DAC technologies including electrolysis-driven regeneration, bipolar membrane electrodialysis (BPMED), electro-swing adsorption (ESA), and proton-coupled electron-transfer (PCET) systems and found that ESA and PCET routes showed significantly lower estimated costs and environmental burdens compared to electrolysis/BPMED for large-scale deployment [77]. Moreover, a recent review specifically on electrochemical steps in DAC found that redox-mediated pH swings, stackable bipolar cells and electrode material optimization are key research-frontier areas [78].

In practical terms, the major benefits of redox-electrochemical DAC methods include direct use of renewable electricity, the possibility of decentralized or modular units, operation at lower temperatures, and elimination of large heat-exchangers and high-temperature regeneration. However, challenges remain such as redox material durability and cyclic stability, cost and scalability of electrodes and sorbents, integration of ambient-air handling (which is extremely dilute ~420 ppm CO2), energy required for air contact and CO2 compression or transport, and realistic cost per tonne CO2 captured. Techno-economic studies show that, depending on scale, region and energy source, the cost estimates vary widely; for example, one study projected costs as low as ~$50–100/t CO2 for PCET systems in favorable conditions by 2040-2050, while electrolysis-based systems remain well above $400–1000/t in earlier deployment phases [77].

In summary, redox-electrochemical DAC methods represent an important new class of carbon-removal technology that aligns well with a decarbonizing energy system powered by renewables. Their integration with other systems (such as renewable generation, storage, or CO2 utilization) may further enhance their viability. Continued advances in redox materials, electrode design, system integration and cost reduction will determine how quickly this pathway can scale.

Despite its promise for climate mitigation, DAC faces several significant challenges. The process is energy-intensive due to the inherently low concentration of CO2 in ambient air, leading to high operational costs currently estimated between $100 and $1000 per tonne of CO2 captured [79,80]. Its large-scale implementation is constrained, particularly because DAC must be powered by low-carbon energy to ensure net climate benefits. Furthermore, the development of robust infrastructure for CO2 transport and secure long-term storage remains a critical logistical challenge. The gradual degradation of capture materials over time also increases maintenance requirements. Crucially, DAC should complement, rather than replace, direct emission reduction efforts as part of comprehensive climate mitigation strategies [81].

Table 1 summarizes key carbon capture technologies, their applications, advantages, disadvantages, and overall feasibility. Pre-combustion capture offers flexible deployment and the ability to capture low-concentration CO2, with the added benefit of integration with renewable energy systems. However, it remains limited by high capital and operational costs, as well as technological complexity, making it moderately feasible mostly in settings with appropriate infrastructure [82].

Table 1.

Comparison of different carbon capture storage technologies [68].

Post-combustion capture is a mature and widely adopted technology, especially suited for retrofitting existing power plants such as IGCC systems. Its ease of separation and high capture efficiency contribute to its high feasibility. Nonetheless, its application can be limited by the specific plant configuration and often requires energy-intensive solvent regeneration processes [50].

Oxy-fuel combustion, applicable to pulverized coal and natural gas combined cycle plants, enables high-purity CO2 streams that facilitate easier capture. Despite its technical maturity and retrofit potential, this method experiences generation inefficiencies and energy penalties, affecting overall plant efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Recent advances have focused on optimizing oxygen production methods to reduce energy consumption [64].

Direct Air Capture (DAC) represents a promising long-term approach capable of capturing CO2 directly from ambient air, enabling negative emissions. DAC technologies offer high-purity CO2 and modular deployment options, but current high investment and operational energy costs limit widespread feasibility. Recent innovations in sorbent materials and process integration with renewable energy are improving DAC economics and energy efficiency [83]

Overall, while post-combustion capture remains the most feasible for near-term deployment, advances in oxy-fuel combustion and DAC technologies are progressively addressing their respective challenges, improving the prospects of broader carbon capture adoption.

2.5. Case Studies and Real-World Application of CCS Technologies

A range of carbon capture technologies has been developed and demonstrated at various scales across the globe, with each offering unique benefits and challenges based on their design and application as presented in Table 2. Direct Air Capture (DAC), a technology designed to remove CO2 directly from ambient air, has seen significant advancements through facilities like Climeworks’ Mammoth plant in Iceland, which began operations in 2024. This facility can capture approximately 36,000 tons of CO2 per year using geothermal energy and modular solid sorbent units, demonstrating scalability and integration with renewable energy sources [84]. Its predecessor, Climeworks Orca, launched in 2021, was the first large-scale DAC plant and has a capacity of around 4000 tons of CO2 annually, storing captured CO2 underground via mineralization in basaltic rock formations, an innovative and permanent sequestration pathway [85]. While DAC offers a pathway to negative emissions, its energy intensity and operational costs remain significant challenges.

Table 2.

Summary of key case studies demonstrating real-world deployment of CCS technologies.

Post-combustion capture, in contrast, is more mature and has been deployed in operational power plants. The Mikawa Post-Combustion Capture Plant in Japan exemplifies this, achieving a capture rate of 180,000 tons of CO2 per year by retrofitting an existing power plant to include chemical absorption units [86]. This approach is especially attractive for decarbonizing current fossil-based infrastructure, though efficiency losses and solvent degradation must be managed.

Pre-combustion capture is used in projects like the GreenGen IGCC facility in Tianjin, China, which was designed to capture up to 1 million tons of CO2 per year as part of an integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) power generation process. In this method, CO2 is removed before combustion by converting fuel into syngas and separating the CO2 at high pressures, enabling greater efficiency in capture and storage [87]. Although promising, pre-combustion systems typically require greenfield development, limiting their retrofit potential.

Another promising approach is oxy-fuel combustion, which involves burning fuel in pure oxygen instead of air, resulting in a CO2-rich flue gas that simplifies separation. The Callide Oxy-fuel Project in Australia, a demonstration facility, successfully captured approximately 27,300 tons of CO2 per year, achieving an impressive 80% CO2 concentration in the flue gas stream [88]. However, high costs related to oxygen production and plant redesign remain obstacles to commercial deployment.

These diverse projects highlight both the progress and remaining hurdles in deploying carbon capture technologies. While post-combustion systems offer near-term feasibility, DAC and pre-combustion approaches hold transformative potential for deep decarbonization, particularly when aligned with renewable energy systems and geological storage solutions.

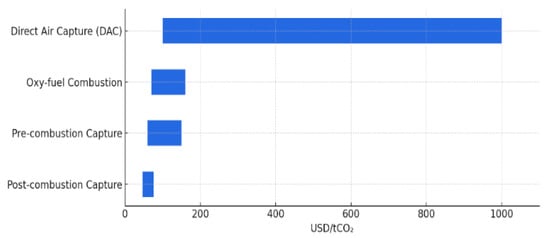

2.6. Cost Estimates for Carbon Capture and Storage Systems

The estimated cost for CCS technologies is presented in Table 3 for various carbon capture technologies highlighting significant differences in their economic viability and technological readiness. Direct Air Capture (DAC) presents the broadest and highest cost range, between $100 and $1000 per ton of CO2 as presented in Figure 8, with pilot projects potentially exceeding these figures. This high cost is primarily due to the technical challenge of extracting CO2 from ambient air, where its concentration is extremely low. Despite its cost, DAC is highly valued for its ability to remove legacy emissions and its flexibility in deployment without location constraints. In contrast, post-combustion capture emerges as the most economically feasible option, with costs ranging from $47 to $76 per ton. This technology is well-established and suitable for retrofitting existing power plants and industrial facilities, particularly where flue gases contain high CO2 concentrations.

Table 3.

Estimated costs of CCS Technologies.

Figure 8.

Estimated cost of CO2 capture technologies.

Pre-combustion capture, with a cost range of $60 to $150 per ton, involves converting fuel into a mixture of hydrogen and CO2 before combustion. While efficient in new plant designs, it is less suitable for retrofitting existing infrastructure due to its complexity and capital requirements. Oxy-fuel combustion costs between $70 and $160 per ton and involves burning fossil fuels in pure oxygen, producing a CO2-rich exhaust that simplifies capture. However, the energy demands of producing pure oxygen and redesigning combustion systems pose economic and operational challenges. Overall, while post-combustion capture currently offers the most practical and cost-effective solution, DAC represents a promising long-term pathway for achieving negative emissions. Future developments must focus on reducing the cost and improving the scalability of all technologies to meet global decarbonization goals.

3. The Role of Carbon Capture Technologies in Mitigating Emissions

Meeting the Paris Agreement target of keeping global temperature rise “well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels” and striving to limit it to 1.5 °C requires swift and substantial reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Numerous emissions pathways have been modelled that align with these climate goals, and in most cases, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) emerges as a pivotal component. CCS contributes in two key ways: (1) it mitigates direct CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use in power generation and industrial operations, and (2) when combined with bioenergy, direct air capture, or similar technologies, it enables large-scale atmospheric CO2 removal, achieving net negative emissions. Without deploying CCS in both capacities, modelled scenarios indicate that achieving sufficient and timely CO2 reductions to meet the “well below 2 °C” target becomes extremely challenging [92].

According to the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 roadmap, Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage (CCUS) is expected to contribute about 8% of the total emissions reductions required, equivalent to approximately 6 Gt of CO2 annually by 2050. Likewise, hundreds of climate scenarios assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscore CCS as a critical factor in nearly all projections that successfully meet the Paris Agreement objectives [93].

The strategic role of CCS within the green transition is most evident for emissions that are not easily eliminated through other measures such as energy efficiency improvements, electrification, hydrogen deployment, or expanded renewable energy production. Specifically, CCS is essential for:

- Retrofitting existing industrial facilities or power plants to continue operation while capturing their CO2 emissions.

- Substantially lowering emissions from energy-intensive sectors that are difficult to decarbonize, including cement, steel, and chemicals.

- Supporting the low-carbon hydrogen economy, which can facilitate decarbonization across industry, heavy transport, and shipping.

- Removing CO2 from the atmosphere to offset unavoidable or hard-to-abate emissions, for instance, through Bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) or Direct Air Capture (DAC).

3.1. CCS Role in Decarbonizing the Industrial Sector

Industrial processes are a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, accounting for about 25% of global CO2 output [94]. Achieving the emission reduction targets set by the IPCC therefore requires substantial decarbonization of this sector. Carbon capture technologies play a critical role in reducing emissions from hard-to-abate industries, including iron and steel production, cement manufacturing, petroleum refining, and power generation. Collectively, these sectors contribute a considerable share of global CO2 emissions, with cement production alone responsible for nearly 8%. According to the International Energy Agency, carbon capture could deliver up to 15% of the total emission reductions required by 2050, reinforcing its importance as a complementary measure to renewable energy expansion and energy efficiency improvements [95,96].

3.1.1. Decarbonizing the Iron and Steel Industry

The iron and steel industry is the largest emitter of CO2 within the industrial sector, responsible for approximately 31% of total industrial CO2 emissions [97]. This high emission intensity arises from the sector’s substantial energy requirements, reliance on coal, and the vast scale of global steel production [98]. Steel manufacturing is primarily carried out via two routes: integrated steel mills and mini mills. Large integrated steel mills are the dominant emission sources, producing on average 3.5 Mt of CO2 per year, while smaller mini-mills typically emit around 200 kt annually. On a per-production basis, a conventional steel mill releases about 1.8 t CO2 for every tonne of crude steel, with the majority originating from coal and coke combustion (1.7 t CO2) and a smaller fraction from limestone use (0.1 t CO2) [99].

The adoption of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) could substantially reduce these emissions. In integrated mills, potential capture points include flue gases from the sinter plant, lime kiln, coke blast furnace, oven plant, basic oxygen furnace and stove. For mini mills, the primary capture source is the electric arc furnace. Post-combustion capture systems can be applied to these streams without disrupting steelmaking operations. Alternatively, “in-process” capture strategies can integrate steel production with CO2 capture, such as employing oxy-combustion in blast furnaces to generate flue gases with a higher CO2 concentration, improving capture efficiency [99].

Several commercial iron and steel facilities have incorporated CO2 capture within their operations; however, the captured carbon dioxide is frequently vented through flaring instead of being stored. Notable examples of such integration include specific Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) plants [98], the Saldanha steelworks in South Africa [100], the Finex process facility in South Korea [101], and the HIsarna process plants located in Germany and Australia [102].

3.1.2. Decarbonizing from the Cement Industry

Concrete is the second most produced material globally after clean water [103]. Cement, a key ingredient of concrete, generates approximately 880 kg of CO2 per tonne produced, with emissions varying between 600 and 1000 kg depending on the manufacturing process. Consequently, cement production contributes to more than 5% of global CO2 emissions. Approximately 60% of these emissions arise from the calcination of limestone (CaCO3) to form calcium oxide (CaO), which is the primary raw material in cement production [104], while the remainder results from the combustion of fuels used to heat kilns and facilitate clinker formation.

A range of CCS technologies can be adapted for the cement sector, including several post-combustion approaches such as solid sorbents, solvent-based scrubbing, oxy-fuel combustion, calcium looping and “direct capture” [105]. Unlike in power generation, pre-combustion capture methods are unsuitable for cement manufacturing due to the significant share of process emissions released during limestone calcination, which pre-combustion systems cannot address. Most applicable CCS options except direct capture are conceptually similar to those in the power sector. Notably, calcium looping offers process synergies because it uses CaO, a feedstock already integral to cement production, as the primary sorbent. Direct capture, which has no direct equivalent in power generation, involves indirect radiative heating of the raw meal containing limestone to directly produce a pure CO2 stream. Both direct capture and oxy-fuel systems offer potential efficiency advantages—either from thermodynamic improvements (direct capture) or by reducing thermal ballast through the elimination of nitrogen from the combustion air [82].

3.1.3. Decarbonizing the Petrochemical and Oil Refining Industries

The petroleum industry is responsible for approximately 6% of global CO2 emissions [106], with emissions generated across the entire value chain, from exploration and extraction to refining and downstream petrochemical production. Importantly, the use of petroleum-derived products in electricity generation, heating, and transportation accounts for about 50% of worldwide emissions. Various carbon capture technologies have been explored for refinery applications, including traditional post-combustion capture. Andersson et al. [107] investigated the utilization of excess waste heat for carbon capture, while Escudero et al. [108] evaluated the economic feasibility of oxy combustion in utility boilers under specific conditions. Additionally, chemical looping combustion (CLC) has shown significant potential, as refinery light gases are suitable fuels for CLC, and refineries already have substantial expertise in engineering and controlling hot solids looping processes, such as those used in fluid catalytic cracking [109].

Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage (CCUS) can play a pivotal role in global decarbonization strategies through several pathways: (i) lowering emissions in sectors that are difficult to decarbonize; (ii) generating low-carbon electricity and hydrogen to facilitate the transition to cleaner fuels across various industries; and (iii) extracting CO2 already present in the atmosphere. By fulfilling these roles, CCUS can also diversify and enhance energy system flexibility, strengthening energy security, a growing priority for many governments. In numerous regions, CCUS offers the most cost-effective pathway for achieving deep decarbonization in industries such as iron, steel, and chemicals. For cement production responsible for nearly 7% of global CO2 emissions, CCUS is currently the only viable large-scale option for significant emissions reduction. Furthermore, integrating CCUS into coal-, gas-, biomass-, or waste-fired power plants enables the generation of low-carbon electricity, which can displace fossil fuel use across applications including transport, residential heating, and industrial low- to medium-temperature heat. Low-carbon hydrogen produced via CCUS can serve as a direct fossil fuel substitute for combustion, as a feedstock in industrial processes, and as a fuel for long-haul transport [110].

There are three main reasons why Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is likely essential for achieving the Paris Agreement’s target of keeping global warming “well below 2 °C.” First, because CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere over time, achieving net-zero emissions is necessary to halt further temperature increases. Without CCS, whether applied to eliminate direct emissions or to remove CO2 from the air, it may be impossible to reach net-zero quickly enough. Second, cost-effective alternatives to fully decarbonize certain hard-to-abate sectors are currently unavailable and may never emerge. In such cases, CCS offers a more viable option, either through direct application in sectors like steel and cement or via CO2 removal to compensate for residual emissions from areas such as long-distance shipping and aviation. Third, in some industries, CCS or CO2 removal may provide a lower-cost pathway to emissions reduction, allowing the financial savings to be redirected toward other societal needs [92].

At present, over 50 commercial-scale CCS facilities are in operation worldwide, with an additional 44 under construction and more than 500 projects in various stages of development [111,112]. Technological advancements including improvements in solvent- and membrane-based capture systems, solid sorbents, and direct air capture are increasing both the efficiency and scalability of CCS solutions [113]. This positions CCS as a critical transitional technology, enabling continued operation of existing infrastructure while substantially mitigating its climate impact.

Although notable progress has been made, recent studies highlight that the pace of carbon capture deployment must accelerate significantly to align with international climate objectives. Without substantial scaling, current implementation rates will fall short of limiting global warming to 2 °C and even further from the 1.5 °C ambition outlined in the Paris Agreement [114]. Pioneering initiatives, such as Norway’s large-scale CCS infrastructure and advances in materials science for CO2 adsorption and recycling, indicate promising pathways for broader adoption [96,113]. Nevertheless, persistent barriers remain, including high costs, substantial energy requirements, storage infrastructure complexities, insufficient regulatory frameworks, and challenges in integrating CCS within broader decarbonization strategies. End-to-end CCS systems encompassing capture, CO2 transport, and geological storage remain both capital- and energy-intensive, restricting widespread uptake [95]. Furthermore, ensuring the long-term integrity and capacity of geological reservoirs demands rigorous monitoring and regulation to mitigate leakage risks and guarantee storage permanence. Unlocking the full mitigation potential of CCS will require sustained investment and coordinated action across industries and governments [95,112,114].

Recent innovations are transforming CCS capabilities, particularly through the development of advanced materials and integration with renewable energy systems. For example, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) can achieve up to 99% CO2 removal in laboratory trials, offering higher efficiency than conventional technologies and reducing energy consumption and operational costs by approximately 17% and 19%, respectively [95]. Flexible integration of CCS with renewable-dominated power grids enhances both resilience and cost-effectiveness, enabling fossil-based assets to provide essential grid stability while delivering substantial emissions reductions as renewable capacity expands [96,111,112]. These advances position CCS not merely as an emissions mitigation tool, but as a fundamental component in maintaining balanced, low-carbon energy systems worldwide.

While CCS has faced criticism for being costly, unproven, or unsafe, operational evidence demonstrates that the technology is both reliable and secure. The primary challenge lies not in its feasibility but in scaling the industry to achieve the multi-gigatonne levels of permanent CO2 storage needed in the coming decades.

4. AI Integration in Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS): Categories, Applications, and Evaluation Metrics

4.1. Taxonomy: Classification of CCUS and AI Integration

Table 4 summarizes the integration of AI across carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies. In carbon capture, AI enhances post-combustion, pre-combustion, oxy-fuel combustion, and direct air capture processes by optimizing operations, controlling reactions, monitoring emissions, and enabling predictive maintenance. For carbon utilization, AI supports the conversion of CO2 into chemicals, fuels, and stable carbonates, as well as optimizing CO2 injection in enhanced oil recovery. In carbon storage, AI facilitates geological storage and continuous monitoring by analyzing sensor data, detecting anomalies, and enabling digital twin modeling to predict leaks and faults.

Overall, AI improves the efficiency, reliability, and safety of CCUS processes, providing data-driven insights that accelerate CO2 management and support sustainable climate solutions.

Table 4.

Overview of AI applications and performance indicators within CCUS system.

Table 4.

Overview of AI applications and performance indicators within CCUS system.

| Category | Subcategory | Description | Examples of AI Application | Key Metrics for Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Capture | Post-Combustion | CO2 separation from flue gases after combustion | AI for process optimization, real-time emission monitoring, predictive maintenance [115,116,117,118] | CO2 capture efficiency, energy penalty operational stability. |

| Pre-Combustion | CO2 capture from syngas before combustion | Machine learning for system design, optimizing shift reaction, solvent regeneration [40,114,115] | Capture rate, solvent consumption, energy requirement, retrofitting ease | |

| Oxy-Fuel Combustion | Combustion with oxygen for easier CO2 separation | AI in oxygen generation control, combustion optimization, leak detection [115,119,120] | Flue gas purity, energy consumption, system reliability, cost-effectiveness | |

| Direct Air Capture | CO2 removal directly from ambient air | AI-driven absorbent material discovery, process optimization, modular control systems [116,119,120,121] | Capture efficiency, energy consumption per ton CO2, scalability, sorbent lifetime | |

| Carbon Utilization | Chemical Feedstocks | CO2 conversion into chemicals and fuels | AI for catalyst discovery, process parameter optimization [115,116,122] | |

| Enhanced Oil Recovery | CO2 injection to improve oil extraction | AI for injection strategy optimization, reservoir simulation and risk prediction [115,116,123] | ||

| Mineralization | CO2 conversion into stable carbonate minerals | AI models predicting mineralization kinetics and optimizing conditions [116,124,125] | ||

| Carbon Storage | Geological Storage | Injection of CO2 into underground reservoirs | AI for seismic monitoring, anomaly detection, digital twin modeling [115,116,117,126] | |

| Monitoring & Verification | Continuous surveillance of stored CO2 | AI-powered sensor data analysis, predictive leakage and fault detection [115,116,117,127] |

4.2. Framework for CCUS Technology Selection with AI Enhancement

Table 5 highlights how AI can enhance CCUS projects across technical, economic, environmental, and social dimensions. AI improves technical performance by optimizing process parameters, predicting maintenance needs, and increasing operational uptime, as demonstrated in CCSNet simulations and AI-based maintenance in CCUS facilities. Economically, AI supports cost modeling, scenario analysis, and modular system design, reducing the cost per ton of CO2 captured and enabling optimized supply chains for scalable deployments.

From an environmental perspective, AI predicts leakage risks, integrates lifecycle emissions assessments, and ensures safer and more sustainable operations, such as real-time monitoring in geological storage. Additionally, AI strengthens regulatory and social readiness by streamlining compliance, facilitating permit management, and enhancing public engagement through transparent communication platforms. Overall, AI serves as a powerful enabler that increases efficiency, reduces risks, and promotes societal acceptance of CCUS technologies.

Table 5.

AI-Enhanced Evaluation Framework for Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) Technologies.

Table 5.

AI-Enhanced Evaluation Framework for Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) Technologies.

| Criteria | Metrics/Indicators | Role of AI | Example Benchmarks/Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Performance | Capture efficiency (%) | AI-driven process parameter tuning, predictive maintenance | CCSNet AI simulation optimizing capture rates [115,117,128] |

| Operational uptime | Predictive analytics minimizing downtime | AI-based maintenance in oil & gas CCUS facilities [116,118,129] | |

| Economic Viability | Cost per ton CO2 captured ($/t) | AI-cost modeling and scenario analysis | AI-supported cost reduction analysis for DAC and post-combustion carbon capture plants [116,130,131] |

| Scalability | — | AI-enabled modular design and supply chain optimization | Modular CCUS system deployments optimized by AI supply chain tools [116,132] |

| Environmental Impact | Leakage risk (%) | AI predictive leakage risk models and anomaly detection | Real-time AI monitoring for leak prevention in geological storage [116,133,134] |

| Lifecycle emissions | AI lifecycle assessment integrating energy use and supply chain factors | AI-driven carbon footprint modeling for CCUS processes [116,117,133,135,136] | |

| Regulatory & Social Readiness | Compliance complexity | AI-facilitated regulatory document preparation and permit monitoring | Faster permit turnaround via AI applications in regulatory processes [119,120] |

| Public acceptance | AI-powered stakeholder engagement and transparency platforms | Enhanced community trust through AI-enabled communication strategies [119,137,138] |

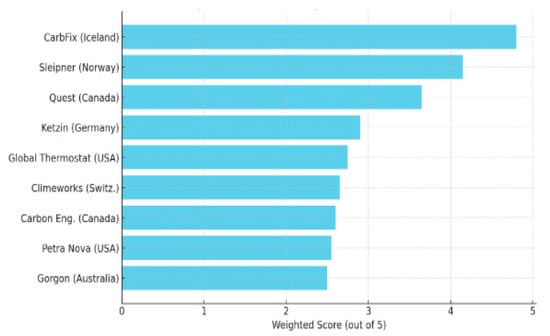

Table 6 compares major CCS and DAC projects worldwide, showing wide variation in performance, costs, and acceptance. Established projects like Sleipner (Norway) and Quest (Canada) demonstrate high capture efficiency, reliable operation, low costs, and strong public trust. CarbFix (Iceland) also stands out with its mineralization method, offering very high efficiency, low costs, and broad community support. In contrast, Petra Nova (USA) and Gorgon (Australia) faced challenges of high costs, downtime, or underperformance, limiting climate benefits and public confidence. Pilot-scale and DAC projects such as Climeworks, Carbon Engineering, and Global Thermostat show promise but remain expensive and energy-intensive, raising scalability concerns. Overall, successful projects combine operational stability, low leakage risk, cost-effectiveness, and community acceptance, while newer technologies still face financial and technical hurdles.

Table 6.

CCUS evaluation framework for nine case studies.

Applying the full Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) framework to the nine CCUS projects provides a structured comparison across multiple performance, economic, and social dimensions. Weights were assigned to each criterion reflecting their relative importance: Capture efficiency (20%), Operational uptime (15%), Cost per ton of CO2 captured (20%), Leakage risk (15%), Lifecycle emissions (10%), Compliance complexity (10%), and Public acceptance (10%). Each project was then scored on a 1–5 scale, where 1 represents poor performance and 5 indicates excellent performance, based on the qualitative metrics in the table. This scoring approach allows for a transparent, weighted aggregation of performance, yielding a ranked comparison matrix that highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of each project.

From the results, CarbFix emerges as the top performer as shown in Table 7 and Figure 9. Its very high capture efficiency and operational uptime, combined with low costs, permanent mineralization of CO2 (reflected in maximum scores for leakage and lifecycle criteria), and excellent public acceptance make it a clear leader across multiple dimensions. Sleipner, a long-established and proven project, ranks second, benefiting from excellent uptime and cost performance, though its capture efficiency is slightly below that of CarbFix. Quest shows solid overall performance, representing a balanced, successful project, but it does not achieve the top scores on cost metrics compared to Sleipner and CarbFix.

Table 7.

Ranked comparison matrix (scores per criterion + weighted score).

Figure 9.

Comparison of CCUS projects using the evaluation framework.

Projects such as Petra Nova and Gorgon occupy lower ranks in the matrix due to their relatively high costs, operational underperformance or downtime, and lifecycle uncertainties, including CO2 offset considerations in enhanced oil recovery. Meanwhile, the Direct Air Capture (DAC) projects; Climeworks, Carbon Engineering, and Global Thermostat cluster in the mid-to-lower range. Their current high costs and energy-intensive lifecycle penalize their overall scores, despite promising capture metrics and strong public interest. Overall, the MCDA framework clearly differentiates projects not only on technical and economic performance but also on long-term sustainability and social acceptance, providing a comprehensive tool for CCUS evaluation and decision making.

4.3. Benchmark for AI Integration in CCUS

Material Discovery: Generative AI reduces time for new solvent/sorbent development by up to 50%, improving capture efficiency and lowering regeneration energy [116,121,122,144].

Process Optimization: AI-enabled process control has demonstrated 10–20% energy savings in amine-based capture at commercial CCS operations like Boundary Dam [145].

Safety and Monitoring: AI-powered seismic anomaly detection improves early leak identification accuracy by 15% in geological storage, enhancing environmental safety [115,116].

Decision Support: AI-enhanced multi-criteria decision analysis has accelerated CCUS project selection efficiency, reducing evaluation time and improving balanced outcomes [146].

Regulatory Streamlining: AI-assisted document automation has shortened permitting cycles by up to 30% in some pilot projects, enabling faster deployment [145].

4.4. Integration Roadmap for AI-Enhanced CCUS Deployment

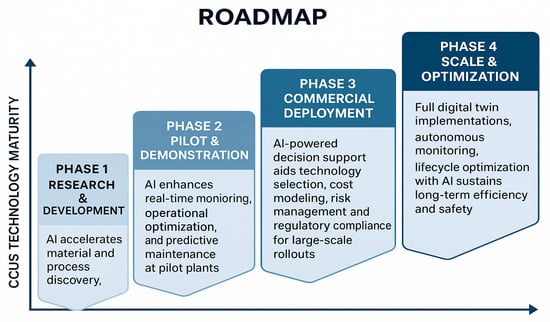

Figure 10 presents a four-phase roadmap linking the maturity of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) technologies with progressive levels of AI integration.

Figure 10.

Roadmap for CCUS and AI Deployment.

Phase 1—Research & Development: Focuses on AI-driven material and process discovery, modeling, and simulation, laying the scientific foundation.

Phase 2—Pilot & Demonstration: AI supports real-time monitoring, operational optimization, and predictive maintenance during small-scale pilot operations.

Phase 3—Commercial Deployment: AI enhances decision making for technology selection, cost modeling, risk management, and regulatory compliance in large-scale rollouts.

Phase 4—Scale & Optimization: Full AI-enabled digital twins, autonomous monitoring, and lifecycle optimization ensure long-term efficiency and safety.

Overall, the roadmap shows a clear progression from research to large-scale optimization, highlighting how AI capabilities expand alongside CCUS technological maturity.

5. Integration of CCUS with Renewable Energy Systems

5.1. Solar and Wind Energy-Powered CCUS