Abstract

This scoping review investigates the use of fuzzy logic in serious games. Articles were searched in nine databases: ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, IOPscience, MDPI, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Springer, Wiley, and Web of Science. The search retrieved 494 articles published between January 2020 and February 2025, of which 28 met the inclusion criteria. Specifically, four research questions were addressed, focusing on the taxonomy of serious games that use fuzzy logic, the characteristics of game design, the purpose and implementation of the fuzzy logic system within the game, and the experiments conducted in the studies. Results reported that 80% of the studies focused on educational serious games, while 20% addressed health applications. Mouse, keyboard, and smartphone touch screen were the most widely used interaction methods. The adventure genre was the most widely implemented in the studies (35.71%). Fuzzy logic was mainly used for adjusting game difficulty, followed by providing tailored feedback in the game. Mamdani inference was the most widely used inference method in the studies. Although 79% of the studies involved human participants in their experiments, 57% did not perform any statistical analysis of their results.

1. Introduction

Video games belong to a key and growing industry for entertainment in our society. The aim of these games is to amuse people. Nowadays, technology is more accessible to people; consequently, serious games have been implemented with several purposes (e.g., education, training, healthcare). The term serious game was coined by Prof. Clark Abt in 1970. There are several definitions for serious games. For instance, Zyda [1] defined a serious game as “a mental contest, played with a computer in accordance with specific rules, that uses entertainment to further government or corporate training, education, health, public policy, and strategic communication objectives”. According to [2], the goal of serious games is “to engage players in a way that is both enjoyable and effective in achieving the intended learning or behavior change outcomes”. Several studies have highlighted their importance. For instance, studies [3,4] have shown that educational serious games play a key role in increasing student engagement, motivation, cognitive abilities, and learning strategies. Additionally, another study [2] showed that serious games focusing on health could encourage physical activity, rehabilitation, healthy eating, quitting smoking, mental health improvement, and reduction of depression and anxiety.

On the other hand, Zadeh [5] defined fuzzy logic as “an attempt at formalization/mechanization of two human capabilities: the capability to converse, reason, and make rational decisions in an […] environment of imperfect information; and the capability to perform a wide variety of physical and mental tasks without any measurements and any computations”. Based on [6], fuzzy logic describes fuzziness, calibrates vagueness, and allows degrees of membership so that natural language terms can be applied to represent and manipulate fuzzy terms. According to [7,8], a fuzzy inference system consists of four elements: (i) fuzzification, which transforms crisp input values into linguistic variables; (ii) fuzzy rule base, composed of IF (conditions)–THEN (consequences) rules that map fuzzy inputs to fuzzy outputs; (iii) inference engine, which evaluates the rules to compute the overall fuzzy output; and (iv) defuzzification, which converts the fuzzy output into a crisp numerical value.

Several studies have highlighted the importance of fuzzy logic due to its ability to (i) address real-world problems involving uncertainty, ambiguous and incomplete information, providing reliable results [8,9]; and (ii) compute predictions and offer semantic explanations for the reasoning process and the output [10]. Recently, reviews have been published on the use of fuzzy logic in various applications: aerial vehicles and motor drives [11,12], analysis of human movement [13], hydrology [14], manipulator robots [15], opinion mining [16], and sentiment analysis [17]. Nevertheless, none of these has focused on the use of fuzzy logic in serious games.

Similarly, several scoping reviews have been published regarding serious games on health (e.g., mental health [18,19,20], motor rehabilitation [21,22], healthcare [23], cancer control [24], treatment of alcohol and drug consumption [25], diabetes mellitus [26]). Furthermore, reviews on the use of artificial intelligence in serious games for healthcare have been published [27,28]; however, these focused only on serious games for health. Additionally, a scoping review by Tolks et al. [28] did not report any studies using fuzzy logic, while a scoping review by Abd-alrazaq et al. [27] reported only six articles using fuzzy logic between 2014 and 2019. Table 1 presents these reviews, including the year of publication, the type of review, the keywords used for the search, and the aim of the review.

Table 1.

Summary of reviews on fuzzy logic and reviews on serious games.

Contributions of This Study

This scoping review has the following contributions: (i) maps the state-of-the-art from January 2020 to February 2025, focusing on the use of fuzzy logic in serious games; (ii) explains a taxonomy for serious games that employ fuzzy logic, detailing aspects such as the application area (e.g., education, health), types of player activity (i.e., mental, physical, physiological), feedback modalities to players (e.g., visual, auditory, haptic), interaction methods (e.g., keyboard, mouse, touch screen, body movements), environment (e.g., 2D, 3D, virtual reality), and hardware architecture (e.g., desktop, smartphone, tablet); (iii) identifies game genres, narrative, and gameplay rules used in serious games with fuzzy logic; (iv) describes how fuzzy logic was applied in serious games and how fuzzy inference systems were implemented, including membership functions for fuzzification, inference methods, fuzzy rules, and defuzzification methods; and (v) reports whether human participants were involved in the experiments, what instruments and metrics were used to assess the performance of serious games, and what statistical tests were applied to support the findings of the studies. These contributions will be analyzed based on the research questions.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 explains the methodology used to conduct this scoping review, including the identification of research questions, the identification of relevant studies, the study selection criteria, and the data obtained for each research question. Section 3 presents the results related to the four research questions addressed in this scoping review. Section 4 provides a discussion of the key findings and future directions for each research question. Additionally, the risk of bias of the studies and the limitations of this scoping review are explained. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of this study.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted using the framework proposed by [29], which involves five stages: (1) identification of research questions, (2) identification of relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) reporting the results.

2.1. Identification of Research Questions

This scoping review aims to answer the following research questions (RQ): RQ1—What is the taxonomy of serious games using fuzzy logic (i.e., application area, activity, modality, interaction method, environment, and hardware architecture)?; RQ2—What are the game design characteristics (i.e., game genre, narrative, and game rules—how it is played)?; RQ3—What is the aim of using fuzzy logic in serious games, and how is the fuzzy logic system implemented (i.e., fuzzification, fuzzy inference, defuzzification)?; and RQ4—Were experiments conducted in the studies (i.e., participants, instruments and metrics, key results, and statistical analysis)?

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies

Two searches were conducted in nine electronic databases: ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, IOPscience, PubMed, MDPI, ScienceDirect, Springer, Wiley, and Web of Science.

The first search used the keywords “fuzzy logic” and “serious game”, while the second search used “fuzzy logic” and “game”. These keywords were selected based on search terms used in the following reviews [16,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Electronic databases might provide filters and advanced search options, which were used to refine the results. The search period for all the databases included publications from January 2020 to February 2025. Table 2 summarizes the filters applied in each database for both searches. The first search was conducted between 25 February and 27 February 2025, and the second search was conducted between 2 March and 5 March 2025.

Table 2.

Filters and advanced search options applied in the electronic databases.

2.3. Study Selection

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to select the articles that were included in this review.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Articles included in this review must: (i) use or implement a serious game; (ii) use fuzzy logic in the serious game; (iii) be written in English; and (iv) be published between 2020 and 2025. The search was restricted to studies published between 2020 and 2025 to include and analyze the most recent developments in serious games and fuzzy logic, considering the fast evolution of both fields and their technological applications.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they: (i) were reviews, books, or editorial notes; (ii) had a length of fewer than four pages; (iii) had an editorial note regarding a concern on the manuscript; or (iv) referred to fuzzy logic only theoretically without any computational implementation.

2.4. Chart the Data

Data were extracted from each article to address the research questions as follows.

2.4.1. RQ1—What Is the Taxonomy of Serious Games Using Fuzzy Logic?

To respond to this question specifically, criteria from the taxonomies proposed by [30,31] were used. The following criteria were analyzed for each article:

- Application area. This explains the area on which the serious game aims to focus. For example: educational serious games, serious games for health applications, serious games for training, serious games for well-being, etc.

- Activity. This involves the activity that the player uses to play the game (i.e., physical exertion, mental, and physiological).

- Modality. It refers to the feedback given to the player in terms of the game design (i.e., visual, auditory, haptic, and smell aspects of the game).

- Interaction method. This refers to the means used by the player to interact with the game. For example: keyboard, smartphone touch screen, joystick, mouse, brain interface, eye-gaze interface, movement-tracking interface, etc.

- Environment. This involves whether the game’s graphical interface was implemented in 2D, 3D, or as a virtual environment.

- Hardware architecture. This criterion is not considered by [30]; however, it is introduced in [31]. It refers to the platform (arcade, PC, console, smartphone/tablet) on which the game is played.

2.4.2. RQ2—What Are the Game Design Characteristics?

The following aspects were investigated per article to answer this question:

- Game genre. This indicator considers the game genres proposed by [32], which are action, adventure, fight, logic, simulation, sport, and strategy.

- Narrative. It refers to the story of the game.

- Game rules. It explains how the game is played.

2.4.3. RQ3—What Is the Aim of Using Fuzzy Logic in Serious Games and How Is the Fuzzy Logic System Implemented?

This RQ analyzes the following:

- Aim of fuzzy logic. This explains the application of fuzzy logic in the serious game.

- Fuzzy Logic System. This involves the methods used for fuzzification (i.e., membership functions to convert crisp input values to fuzzy input sets), fuzzy inference (i.e., the rules—If (conditions) Then (consequences) statements—to map the fuzzy input sets to the fuzzy output sets), and defuzzification (i.e., the method used to convert the fuzzy output to the crisp output value).

2.4.4. RQ4—Were Experiments Conducted in the Studies?

Four parameters were obtained from the articles to answer this RQ:

- Participants. It indicates the sample of participants involved in the experiments in the study.

- Instruments and metrics. It explains the instruments used to assess the game performance and participants’ feedback (e.g., game score, questionnaires, participants’ emotions).

- Key results. It reports the main findings of the study.

- Statistical analysis. It presents the statistical tests that were applied to the results to support the findings.

3. Results

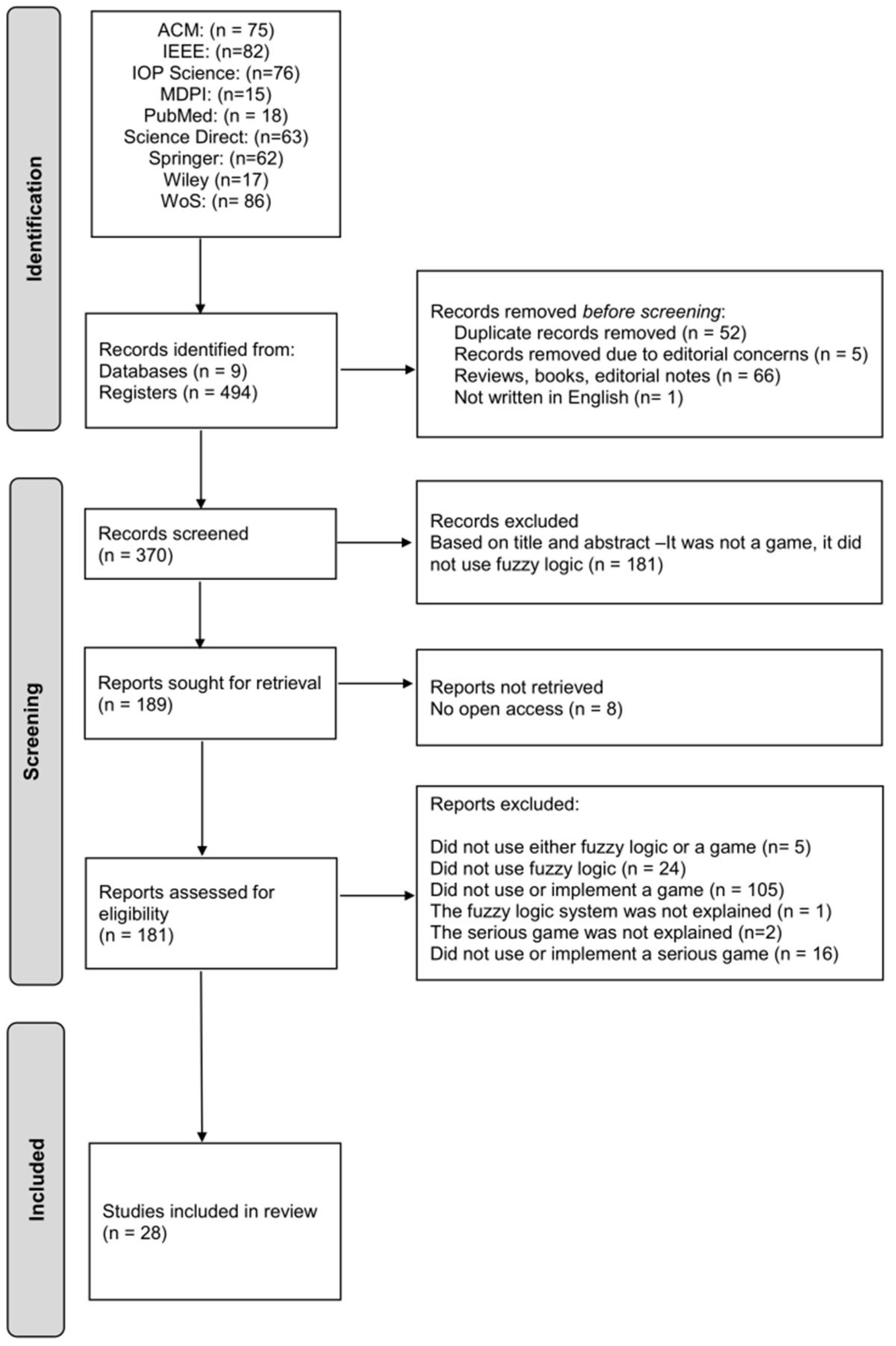

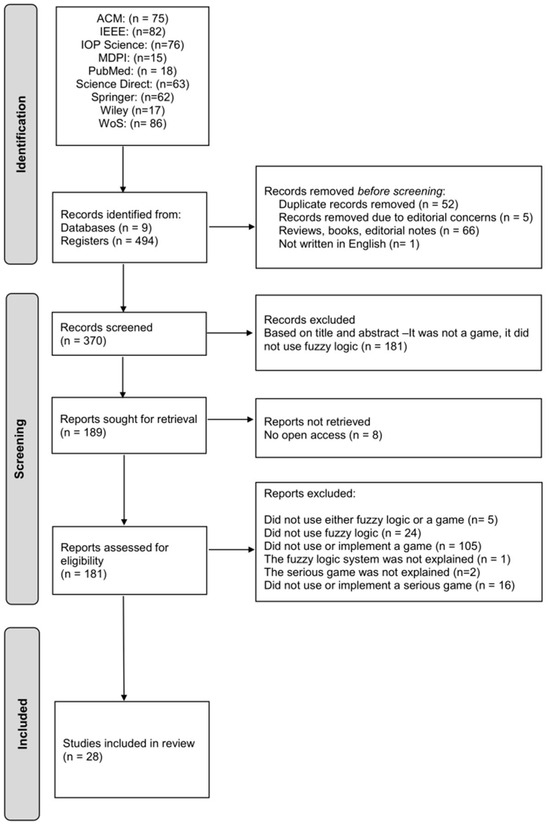

Initially, the searches performed in the nine databases retrieved 494 articles. After deleting duplicated articles, 442 articles were analyzed based on their titles and abstracts. PRISMA protocol [33] was used to include articles (see Figure 1). Articles were excluded in the first screen (i.e., based on their titles and abstracts) because (i) they were reviews, editorial notes, or books (sixty-six articles); (ii) they were not written in English (one article); (iii) they presented editorial concerns (five articles); (iv) they were not accessible (eight articles); and (v) they were out of the scope based on their titles and abstracts (one hundred and eighty-one articles). After reading the 181 articles, 153 articles were excluded because (i) they neither used fuzzy logic nor used or implemented a video game (n = 5); (ii) they used a game; however, they did not use fuzzy logic (n = 105); (iii) they did not use fuzzy logic (n = 24); (iv) the fuzzy logic system was not explained (n = 1); and (v) the serious game was not described (n = 2). As a result, 44 articles were analyzed in depth; however, 16 articles ([34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]) were excluded because, even though they used fuzzy logic and a video game, the video game was not a serious game. Consequently, only 28 articles met all the inclusion criteria and are presented in this scoping review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the searches.

3.1. Results on RQ1—What Is the Taxonomy of Serious Games Using Fuzzy Logic?

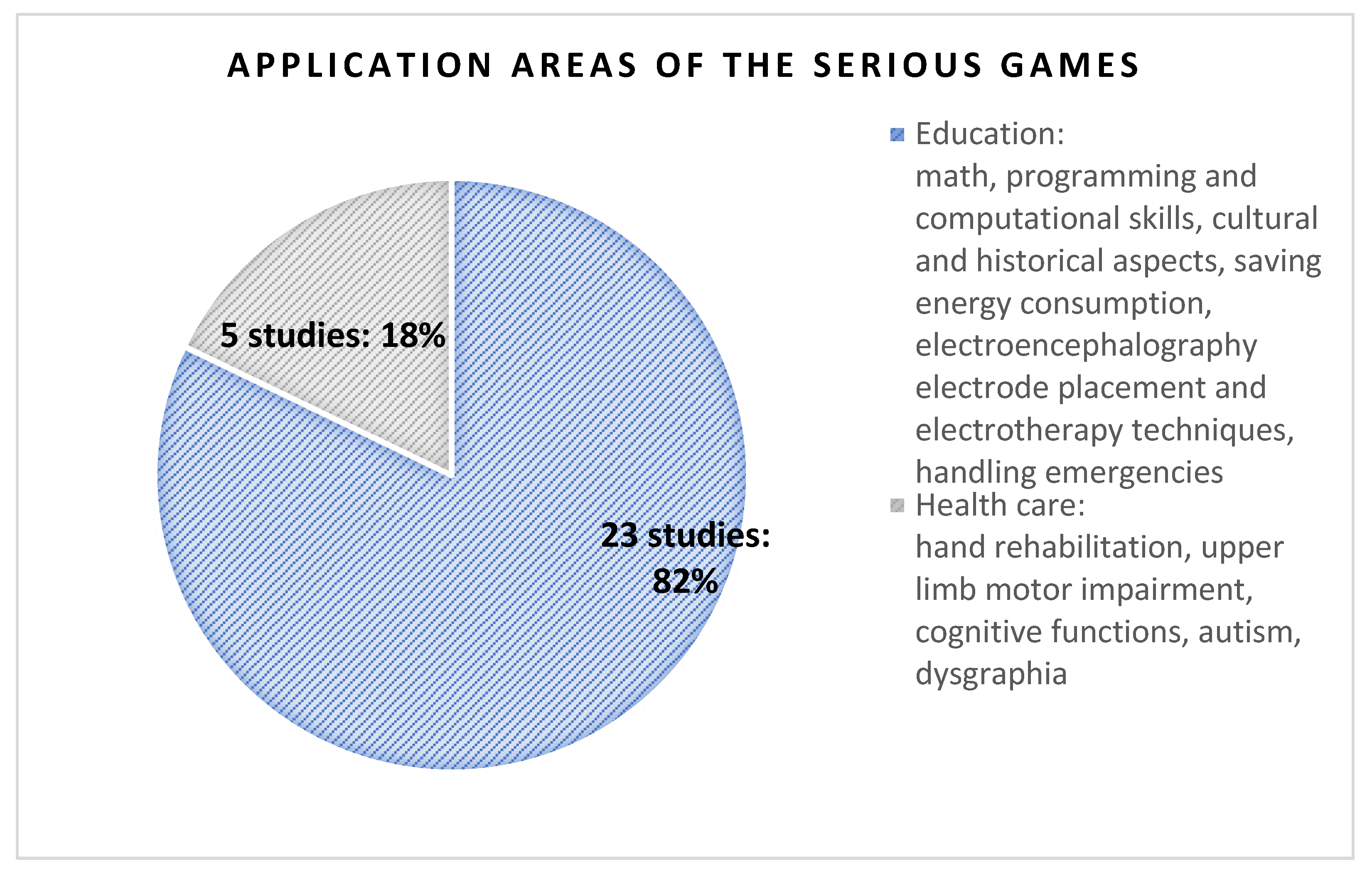

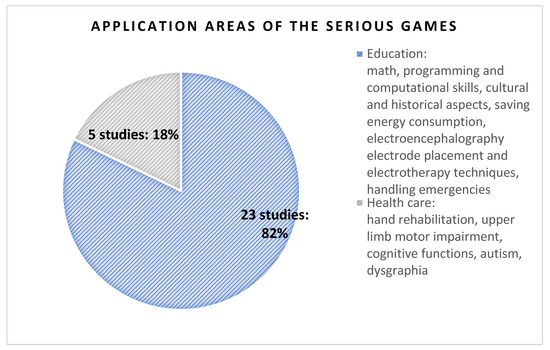

Based on the application area (see Figure 2), most studies implemented or used educational serious games (82.14% of the studies), followed by serious games for healthcare (17.86% of the studies) for (i) hand rehabilitation [49]; (ii) upper limb motor impairment [50]; (iii) cognitive functions in elderly people [51]; (iv) autism in children [52]; and (v) dysgraphia disorder in children [53]. Regarding the educational serious games, they focused on (i) teaching math [54,55]; (ii) teaching programming and computational skills (i.e., HTML [56,57,58], C++ [59], computational skills for controlling a robot via control commands [60], and support for co-learning between students and robots in classroom environments [61]); (iii) teaching cultural and historical aspects (i.e., citizenship behavior [62], historical events in Indonesia [63,64], Javanese letters [65]); (iv) encouraging consumers to reduce energy consumption [66,67]; (v) teaching electroencephalography electrode placement [68] and electrotherapy techniques [69]; (vi) teaching general knowledge on animals, arts, sports, history, and geography [70]; and (vii) handling emergencies (i.e., learning content on disaster mitigation [71], and simulating pre-evacuation human reactions in fire emergencies [72]).

Figure 2.

Application areas of the serious games.

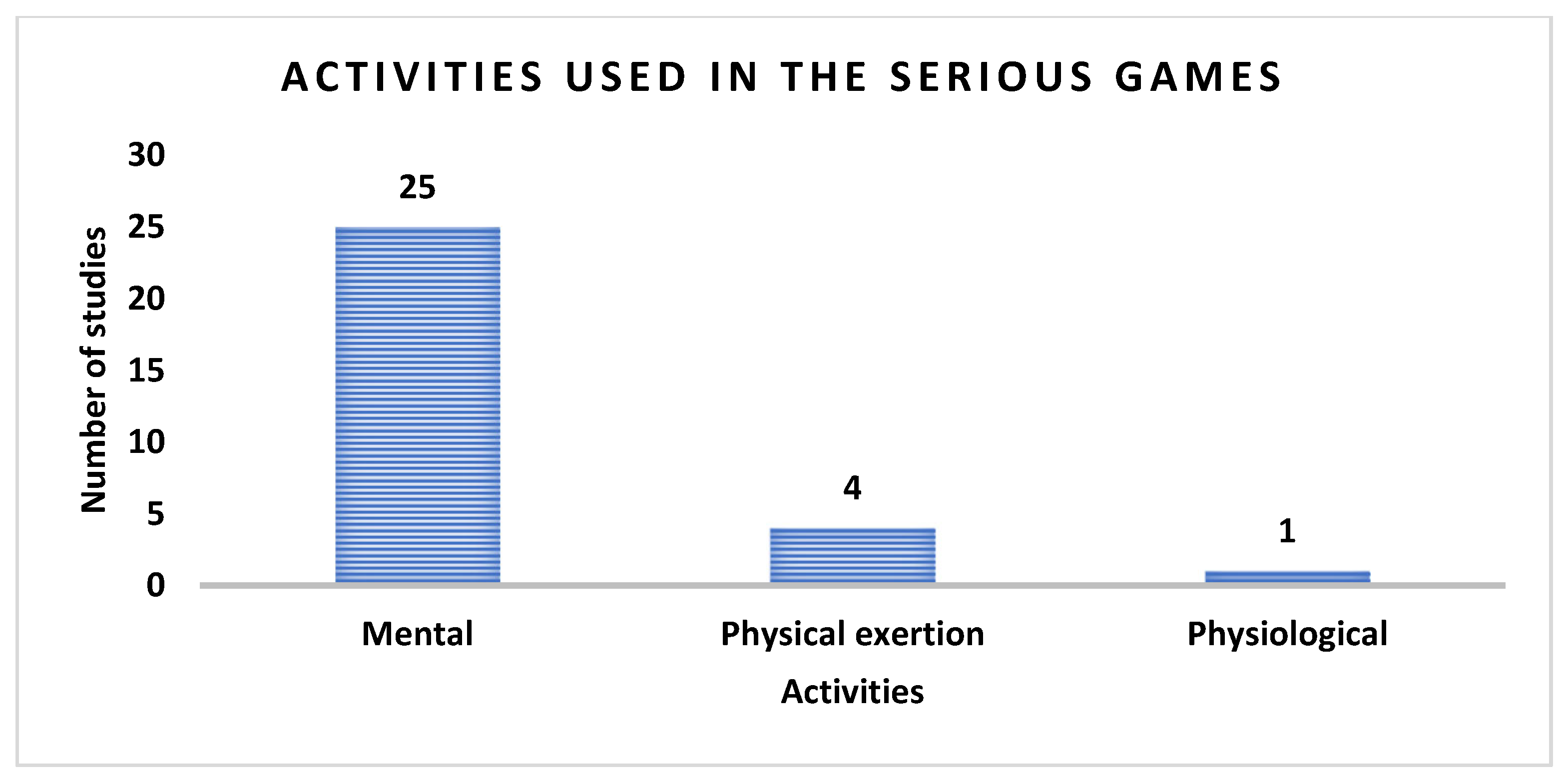

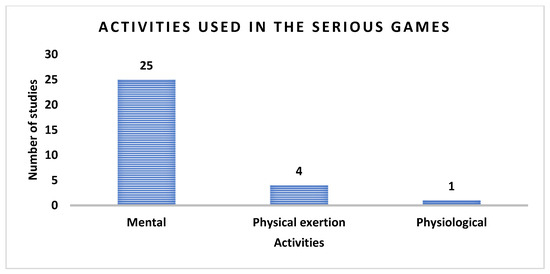

In the context of the activity used in serious games (see Figure 3), most studies employed serious games in which the participants needed to perform mental activities (25 studies: 89.28%). Nevertheless, physical exertion during gameplay was required of participants in only four of the studies [49,50,52,53]. Moreover, in only one study [52], the players performed physiological activity to be able to play the game. It is important to note that few studies required the players to perform two activities to play the games (i.e., physical exertion and physiological [52], mental and physical exertion [53]).

Figure 3.

Activities used in the serious games.

Focusing on the modality provided by the games (i.e., the feedback given to the players), only one study did not present the information, and there was insufficient context to infer the modality. The remaining studies used serious games that provided visual feedback. Over one-third of the studies (35.71%: 10 out of 28 studies [51,52,54,55,61,62,70,72,73,74]) employed serious games that offered visual and auditory feedback to players. It is important to note that none of the studies provided haptic feedback to players.

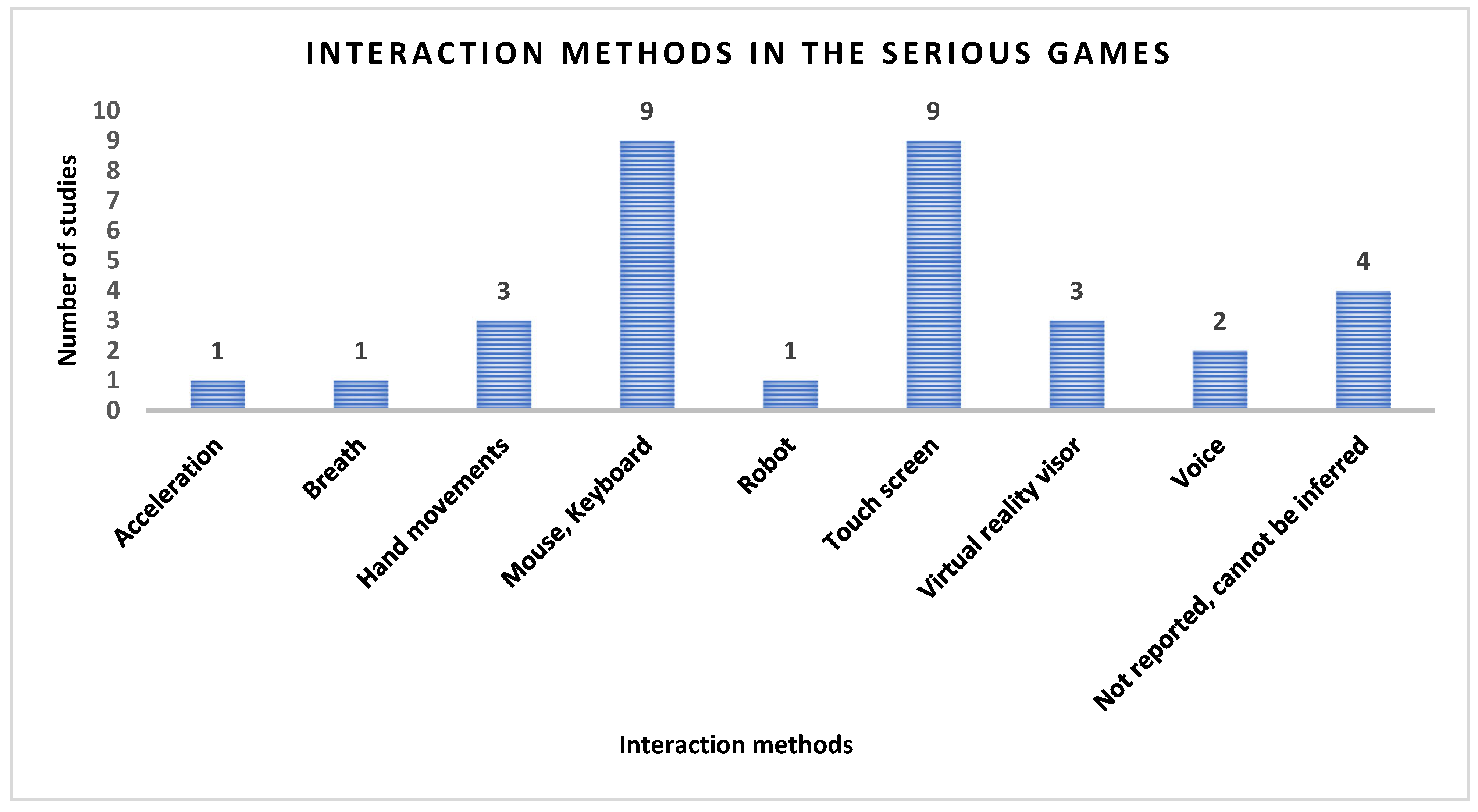

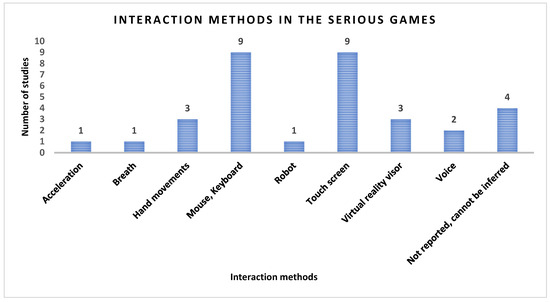

Regarding the interaction method (see Figure 4), four studies did not indicate it, and the information could not be inferred from the articles. The most widely used interaction methods in the serious games were mouse and keyboard (32%: 9 out of 28 studies [54,55,57,58,60,68,73,75,76]) and the touch screen of a smartphone (32%: 9 out of 28 studies [51,58,62,63,65,66,67,69,70]).

Figure 4.

Interaction methods in the serious games.

Other studies have used body movements to play the games. For instance, hand movements detected by a Leap motion controller sensor [49] and by a Kinect depth camera [50,53] were employed to play games for motor rehabilitation and a game for dysgraphia disorder treatment (i.e., a disorder that affects the ability to write in children). Moreover, few studies have integrated virtual reality into their games using head-mounted virtual reality displays as the interaction device [51,72,74].

Few studies [51,54] used the player’s voice to interact with the game. Finally, one study [52] employed breathing and acceleration data collected from a smartwatch as the interaction method to help children with autism practice box breathing techniques.

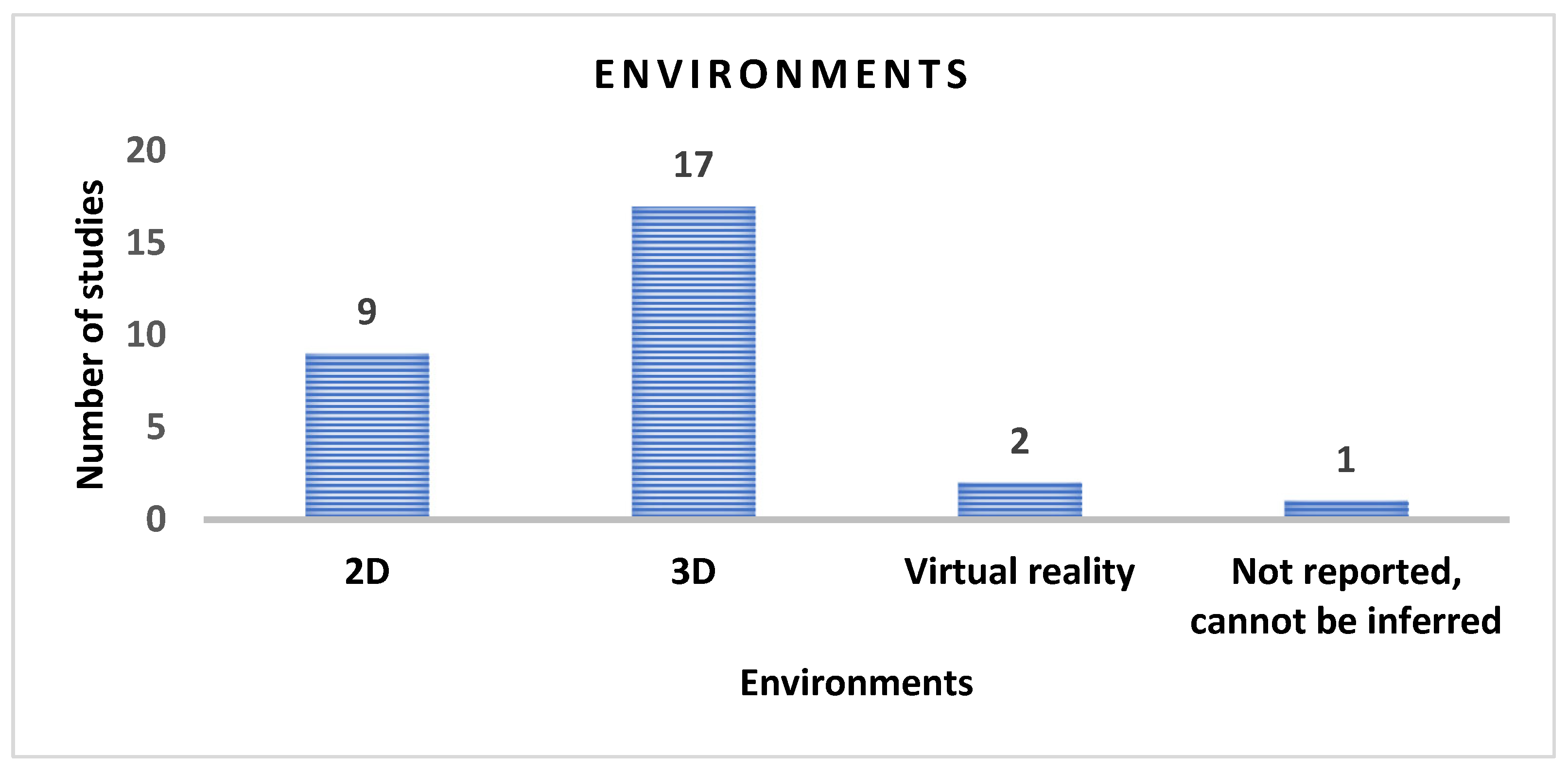

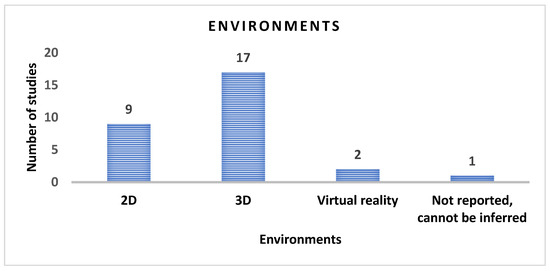

In terms of the environments created in the serious games, it can be seen from Figure 5 that over half of the games were implemented using a 3D environment (61%: 17 out of 28 studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,56,57,58,63,65,66,67,68,73,75,76]), followed by a 2D environment (32%: 9 out of 28 studies [55,60,61,62,63,64,69,70,71]). Few studies [72,74] have implemented virtual reality environments in their games.

Figure 5.

Environments created in the serious games.

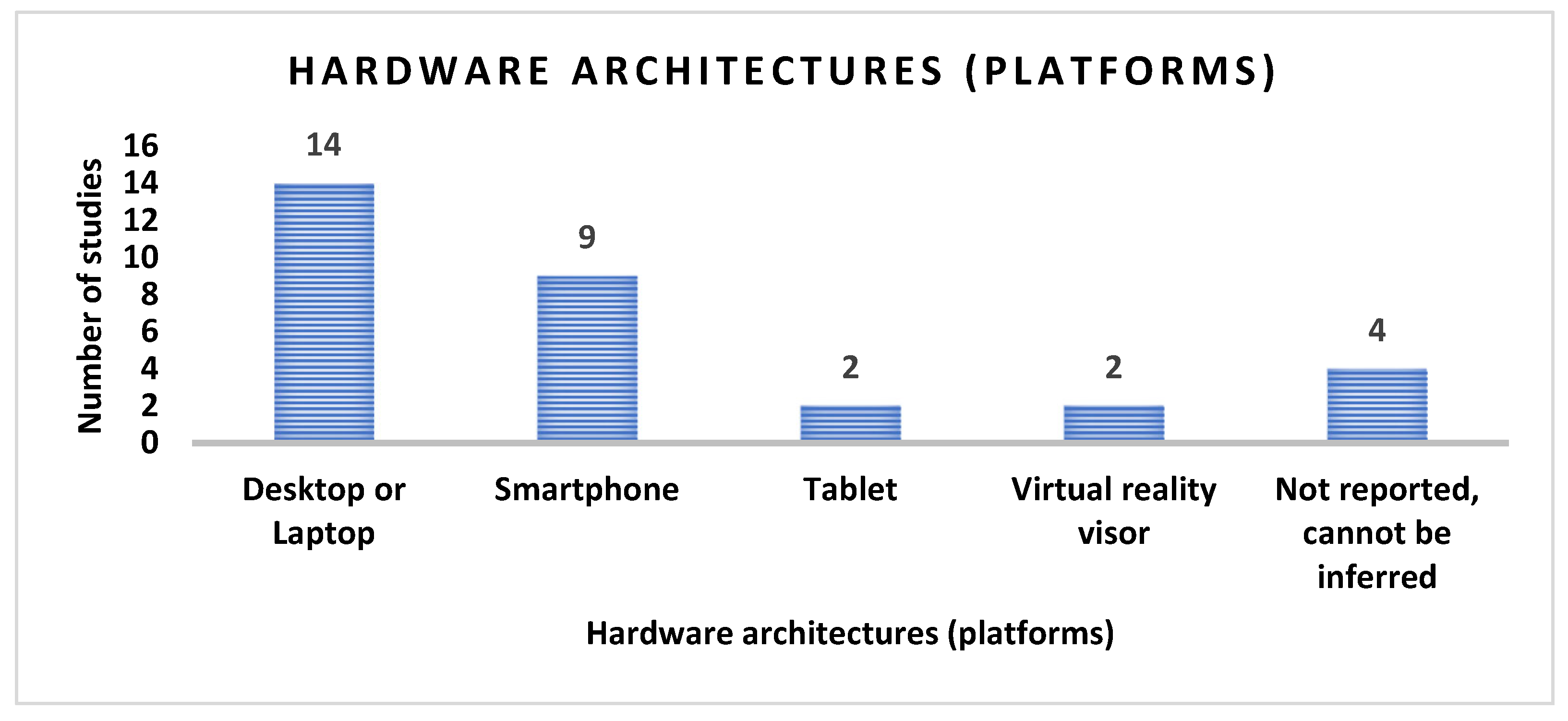

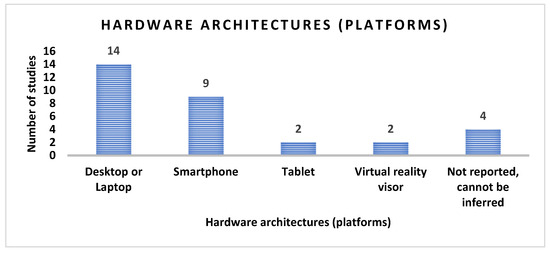

Focusing on the hardware architectures (i.e., platforms) in which the serious games could be played (see Figure 6), the most widely used platforms were desktops and laptops (50%: 14 out of 28 studies [49,50,53,54,55,57,58,60,61,68,72,73,75,76]), followed by smartphones (32%: 9 out of 28 studies [51,58,62,63,65,66,67,70,74]). Few studies employed tablets [52,69] and virtual reality visors [72,74] to play the serious games. Table 3 summarizes the studies in terms of RQ1.

Figure 6.

Hardware architecture (platform) on which the serious games could be played.

Table 3.

Indicators in the taxonomy of serious games using fuzzy logic.

3.2. Results on RQ2—What Are the Game Design Characteristics?

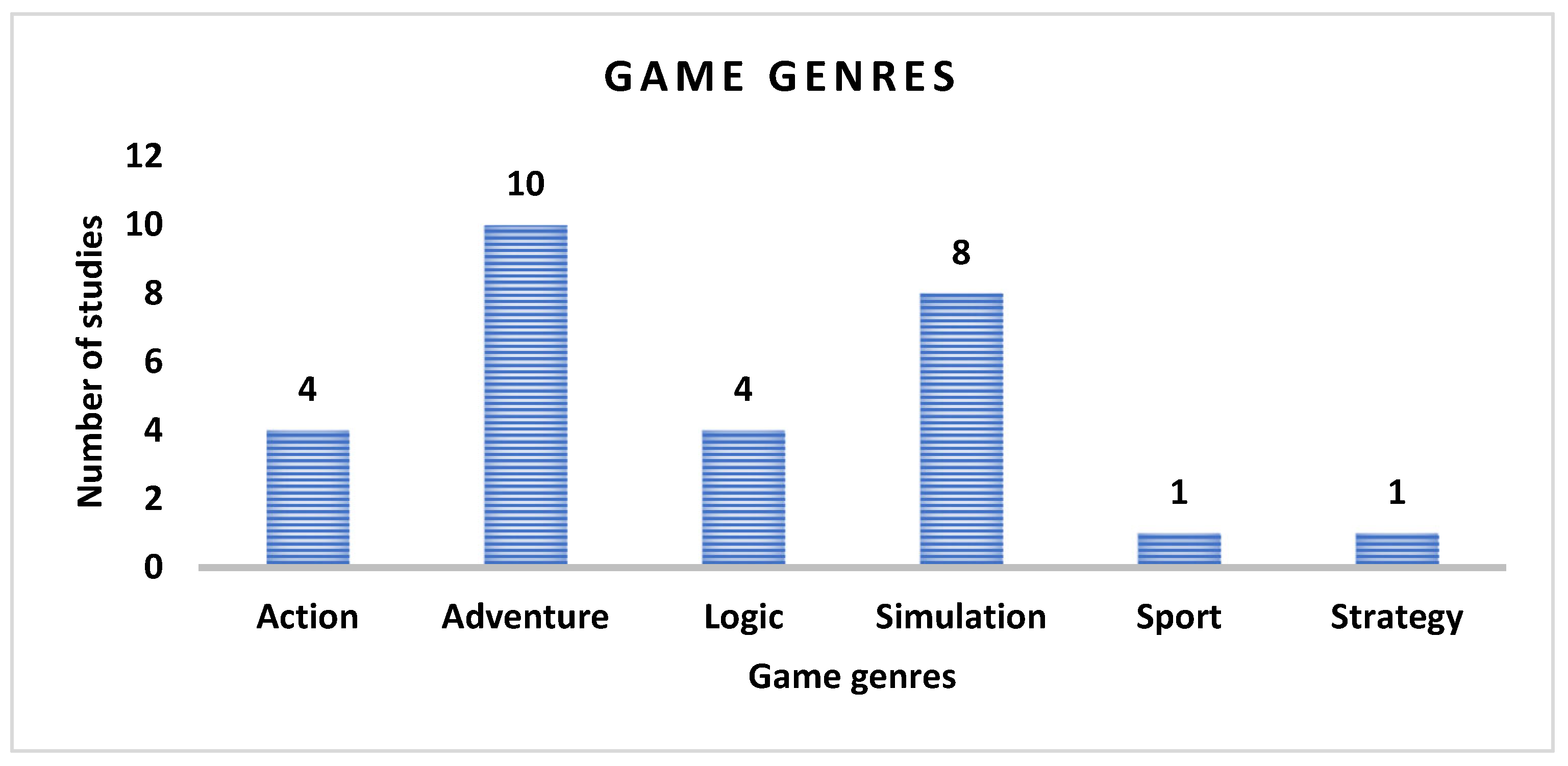

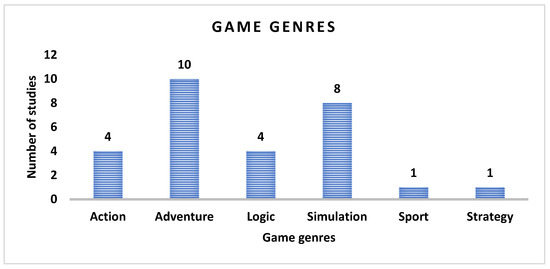

It can be seen from Figure 7 that most studies used the adventure game genre (35.71%: [52,56,57,58,62,63,70,73,74,76]), followed by the simulation genre (33.33%: [51,66,67,68,69,71,72,75]) in their games. Additionally, action games (14.28%: [49,53,54,55]) and logic games—specially puzzles—(14.28%: [59,60,64,65]) were implemented in the studies. Finally, only one study [50] created a sport game, and another study [61] created a strategy game.

Figure 7.

Game genres of the serious games.

Regarding the game narrative, the adventure games involved storytelling elements, such as (i) exploring a water village [73] and an island with castles [56]; (ii) understanding scenarios related to digital citizenship [62] and historical events [63]; (iii) fighting zombies [70]; (iv) following a character through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in search of healthcare support [74] and figures from Balinese culture [76]; (v) escaping from a locked house [57,58]; and (vi) protecting the world by maintaining the balance of water, wind, earth, and fire [52].

Simulation games focused on scenarios such as (i) urban planning [75], energy consumption [66], and a connected thermostat interface [67]; (ii) clinical situations requiring electrotherapy interventions [69] and the placement of electroencephalography electrodes on a 3D human head [68]; (iii) daily living situations related to cognitive functions [51]; and (iv) disaster mitigation [71] and firefighting scenarios [72].

Logic games included puzzles such as guiding robots to light up boxes [60], solving C++ programming challenges [59], identifying historical figures [64], and working with puzzles on Latin characters [65].

In the context of action games, these involved destroying boxes [49], catching falling apples [53], placing falling objects into the correct containers [54], and running races [55]. Finally, the only sport game was a ping-pong match [50], while the only strategy game required placing black or white stones on a grid [61].

Focusing on how the games were played, most studies (64%: 18 out of 28 studies) required players to select options or objects displayed in the game interface [52,54,55,57,58,59,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,74,75,76]. Some games provided control commands, such as move forward, turn right, turn left [49,54,60], and throw [49] or shoot [70]. Additionally, certain games involved navigating through the game environment [56,63,72], while others required players to mimic striking postures [50] or catching movements [53]. Table 4 explains further details on RQ2.

Table 4.

Game design.

3.3. Results on RQ3—What Is the Aim of Using Fuzzy Logic in Serious Games and How Is the Fuzzy Logic System Implemented?

Based on the analysis of the studies, these can be classified into two categories regarding the architecture of the fuzzy logic system:

- Fuzzy inference systems (FIS): These systems involve those that have implemented the three stages in their systems: fuzzification, fuzzy inference, and defuzzification (75%: 21 out of 28 studies).

- Semi-fuzzy systems: These studies correspond to those that have only used fuzzification or fuzzy concepts (e.g., fuzzy sets). However, they did not use the three stages (25% of the studies: [57,58,60,69,72,73,75]).

3.3.1. Fuzzy Inference Systems

Fuzzy logic has been used in the studies for several purposes. Most studies in this category have applied fuzzy logic (i) to adjust game difficulty by modifying non-player character behavior (38%: 8 out of 21 studies [49,52,53,54,56,59,70,71]); (ii) to provide tailored feedback within the game (19%: 4 studies out of 21 [62,63,66,67]); and (iii) to compute the game score (14%: 3 out of 21 studies [64,65,74]).

Additionally, other studies have used fuzzy logic (i) to assess player features (i.e., upper limb motor function [50], player engagement [74]); (ii) to provide feedback on player performance ([55,68]); and (iii) to determine the player character [76].

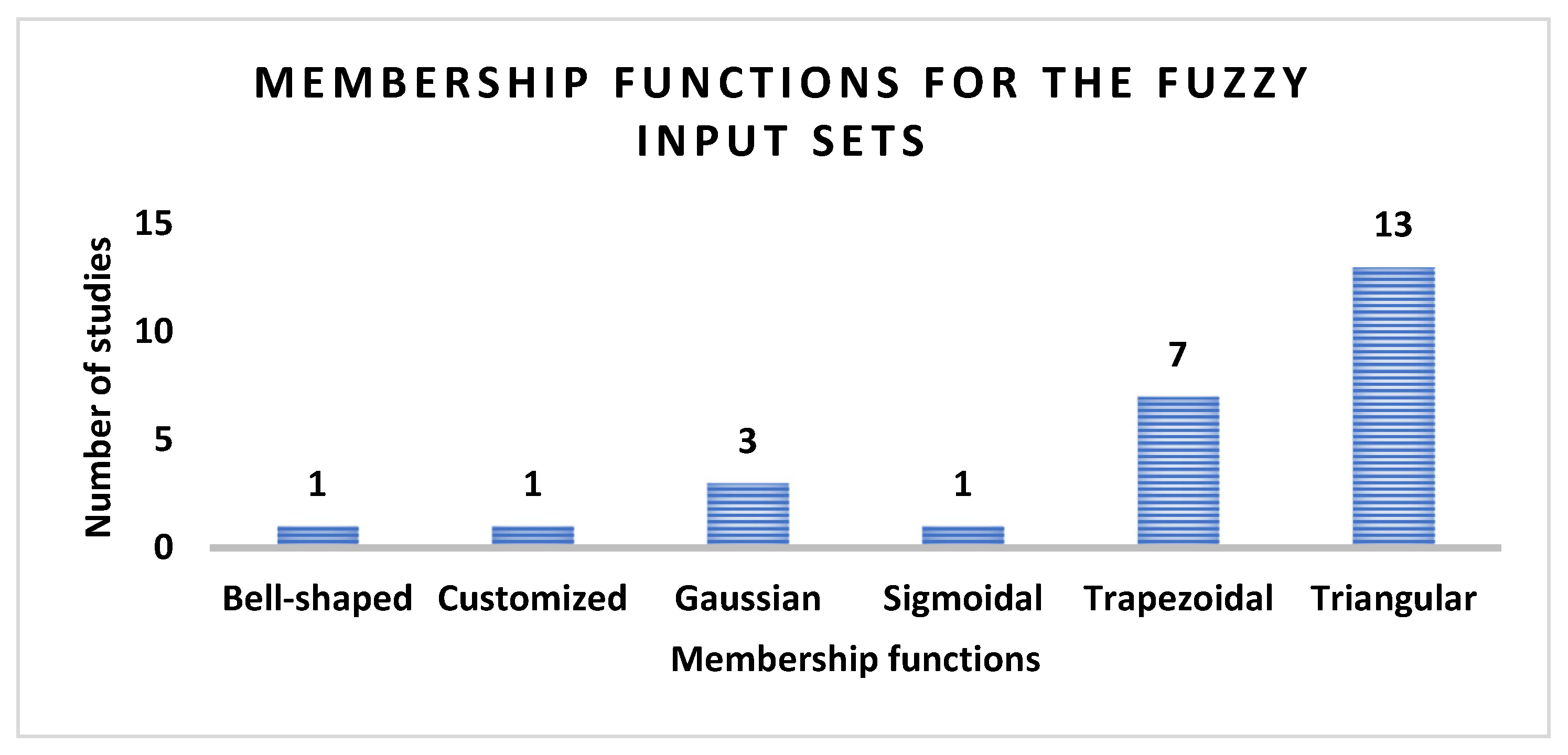

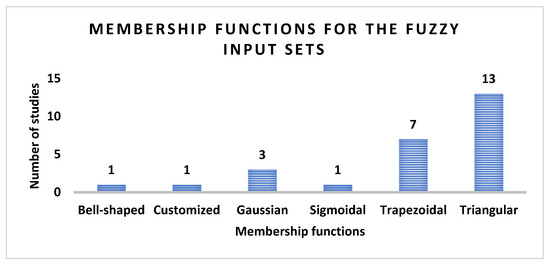

In the context of fuzzification (i.e., mapping crisp values to linguistic variables), the most widely used membership functions for fuzzy input sets in the studies were triangular functions (62%: 13 out of 21 studies [49,52,53,55,59,64,65,66,67,70,71,74,76]), followed by trapezoidal functions (29%: 6 studies out of 21 [50,56,61,68,71,76]) and Gaussian functions (14%: 3 out of 21 studies [51,54,76]) (see Figure 8). Only one study [76] used and compared several membership functions for fuzzy input sets: triangular, trapezoidal, Gaussian, bell-shaped, and sigmoidal functions. Conversely, only one study [62] implemented a customized membership function for the fuzzy input sets.

Figure 8.

Membership functions for the fuzzy input sets.

It is important to note that most studies used as input to the fuzzy logic system information generated in the game, such as (i) player’s skills in the game and error degree (15 out of 21 studies: [50,51,55,56,59,61,62,63,64,65,68,70,71,74,76]) and (ii) game score (6 out of 21 studies: [51,53,54,63,64,70]).

Conversely, few studies employed information obtained from the players as the input to the fuzzy system; for instance: (i) range of motion of hand movements detected via a Leap motion controller sensor [49], (ii) player’s breathing [52], and (iii) player’s emotions detected via player’s voice [54].

Focusing on fuzzy inference, most studies used only one fuzzy inference system (FIS). Nevertheless, a study [50] implemented a hierarchical fuzzy inference system, which was a tree structure with three FIS subsystems. Moreover, the majority of the studies (90%: 19 out of 21 studies) employed Mamdani fuzzy inference [49,50,51,52,54,55,56,59,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,74]. In contrast, only two studies implemented Tsugeno fuzzy systems [53,76].

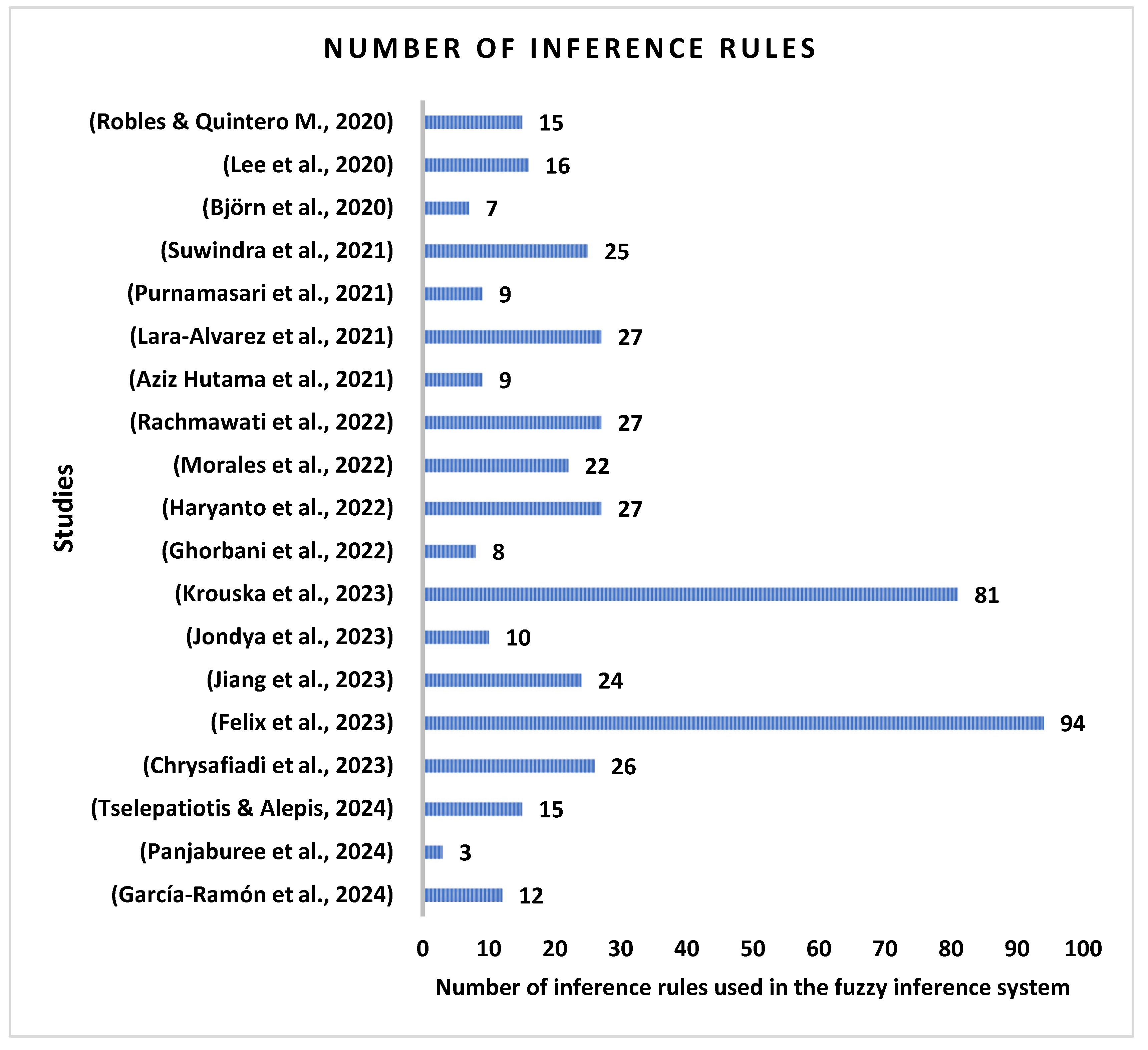

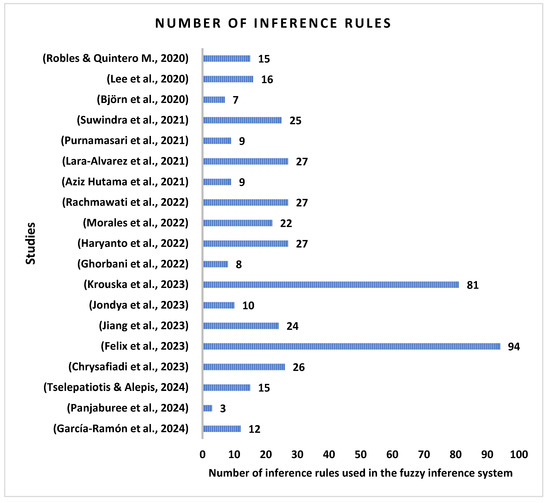

Figure 9 shows that the fewest number of rules used in the FIS in the studies was three rules [62], while the highest was 94 [74], followed by 81 rules [59]. The most widely used number of rules was twenty-seven [54,64,71], followed by fifteen rules [55,70] and nine rules [53,65].

Figure 9.

Number of inference rules used in the fuzzy inference system of the studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,59,61,62,63,64,65,68,70,71,74,76].

In the context of fuzzy logical conjunctions used in the antecedents of rules (e.g., AND, OR, NOT), that is, the “IF (conditions)” part of the rule that relates input fuzzy sets, the AND conjunction was employed in 71% of the studies (15 out of 21 studies: [50,52,53,54,55,59,61,63,64,65,66,70,71,74,76]). Only one study used AND and OR conjunctions in its rules [56]. The remaining studies did not employ conjunctions in the antecedents of the rules [49,51,62,67,68].

Focusing on the defuzzification process (i.e., converting the fuzzy output to a crisp value), most studies did not indicate the defuzzification method (10 out of 21 studies: [51,52,53,56,61,63,64,65,70,74]). The most widely used defuzzification method in the studies was the center of area (38%: 8 out of 21 studies [50,54,55,59,66,67,71,76]). Additionally, the center of sums [49,68] and the maximum membership method [62] have been used to defuzzify. Moreover, triangular (43%: 9 out of 21 studies [50,51,52,55,59,66,67,70,74]), trapezoidal (19%: 4 out of 21 studies [49,61,68,74]), singleton (2 out of 21 studies [51,63]), and Gaussian [54] functions were used for fuzzy output sets. In most studies, fuzzy output sets were modeled using linguistic variables such as non-player character features, game appearance [49,51,52,53,54,56,66,67,70,71], and player performance [59,62,63] to adjust game difficulty. Other studies employed the fuzzy output sets to assess the player’s performance in terms of linguistic variables [50,55,61,65,68,74].

Further details on the fuzzy logic systems in these studies can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Fuzzy inference systems used in serious games.

3.3.2. Semi-Fuzzy Systems

A quarter of the studies included in this review implemented semi-fuzzy systems [57,58,60,69,72,73,75]. Most studies in this category used fuzzy sets. Specifically, a study [60] employed fuzzy sets, fuzzy relations, and fuzzy attribute implications to represent the students’ solution in the light-bot game. Other studies used fuzzy sets: (i) to model the knowledge level of students [57,58]; (ii) to model perception of a non-player character in terms of distance to the player in the game scene [73]; (iii) to assess criteria for virtual environment usability [72]; and (iv) to represent values of electrode placement (well oriented, centered, and well distributed) and electrical parameters for the treatment (i.e., pulse width, frequency, amplitude, rest time, treatment time) [69].

Finally, only one study [75] employed fuzzy AND aggregation to compute scores for urban layouts (spatial configurations) in a 3D urban design space. Further details of these studies can be found in Table 6.

Table 6.

Semi-fuzzy systems used on serious games.

3.4. Results on RQ4—Were Experiments Conducted in the Studies?

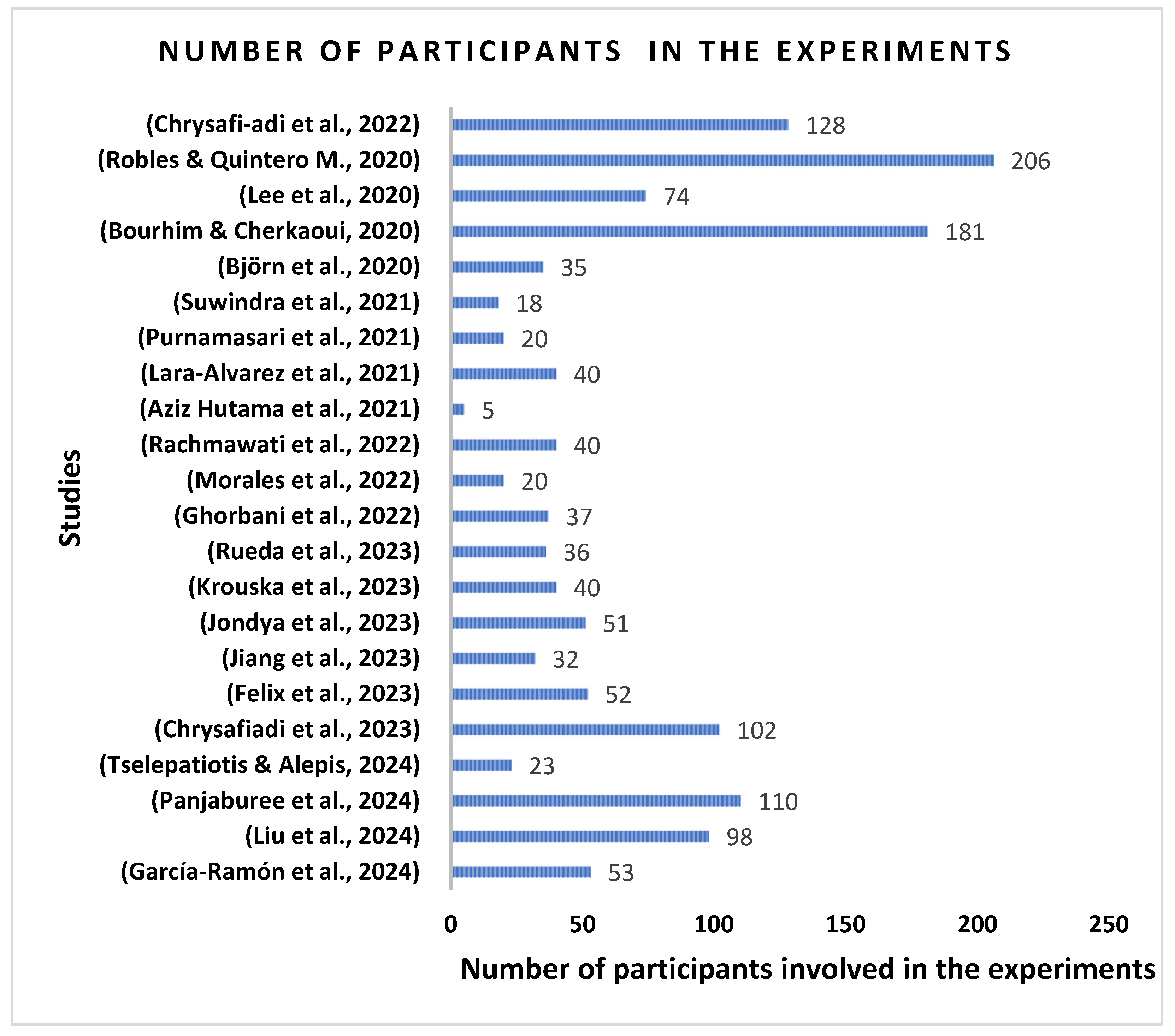

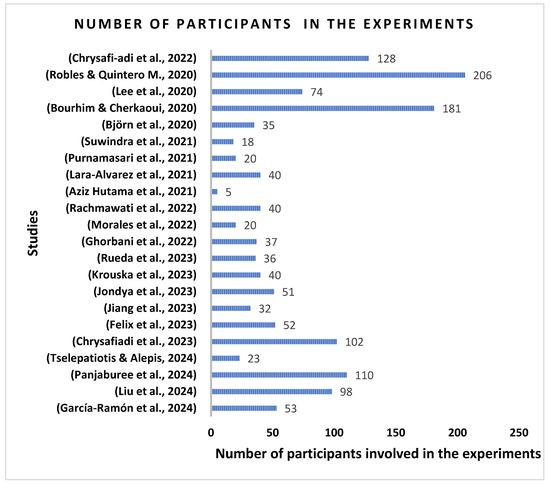

Most studies conducted experiments involving people participation (79%: 22 out of 28 studies). The smallest sample size in the studies was five participants [53], while the largest sample size was 206 participants [55] (see Figure 10). Most studies (77%: 17 out of 22 studies) used samples of more than 30 participants, while only a few studies included fewer than 30 participants [52,53,65,70,76]. Conversely, a few studies did not indicate the number of volunteers who participated in the experiments [60,67,75]. Additionally, a few studies conducted experiments using simulations that did not involve the participation of people [66,71]. Some studies used the game as an assistive tool. Of these, only two conducted experiments with participants who had the medical condition that the game was designed to address (i.e., hemiplegia [50], autism [52]).

Figure 10.

Number of participants involved in the experiments of the studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,61,62,63,64,65,68,69,70,72,73,74,76].

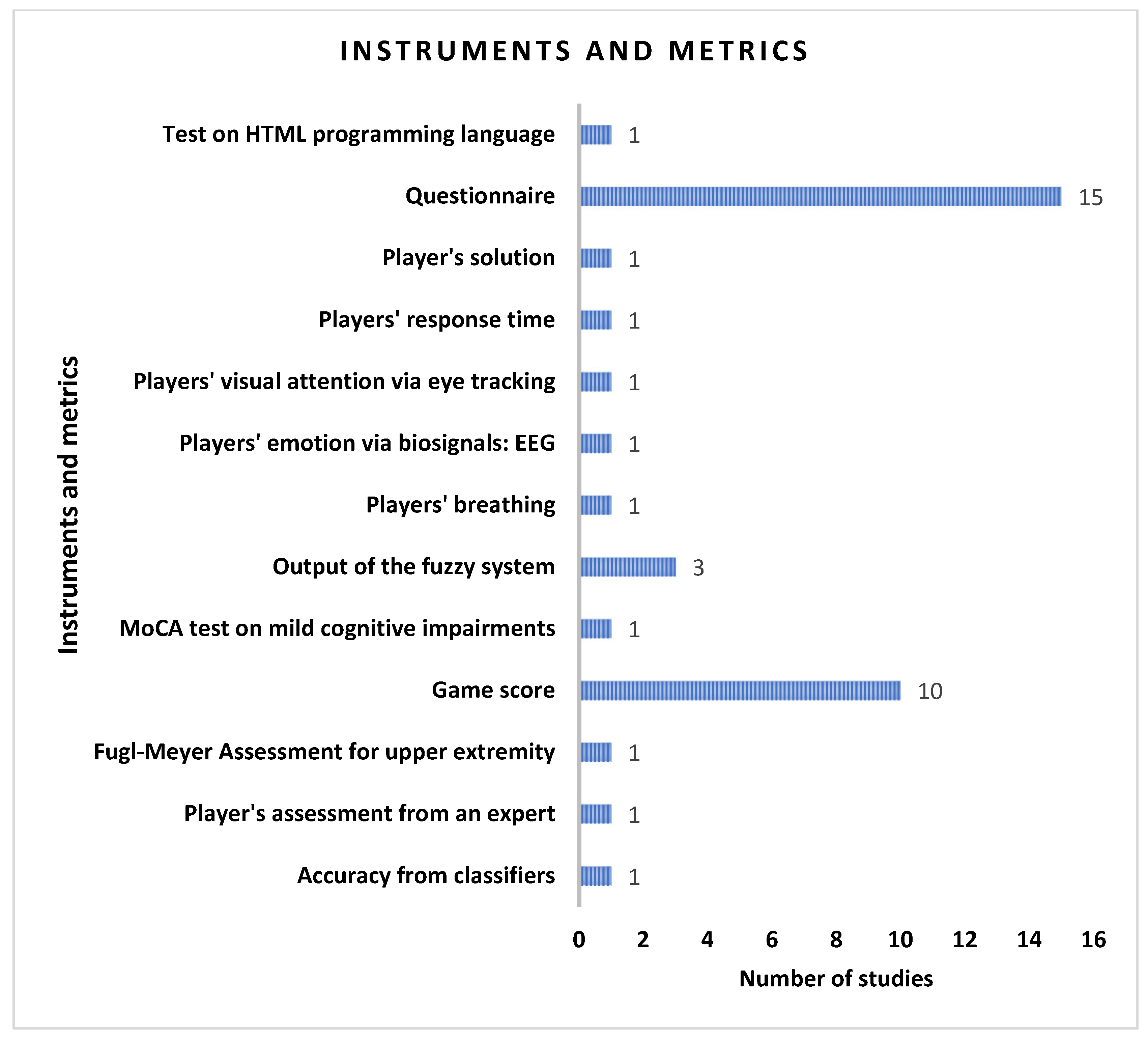

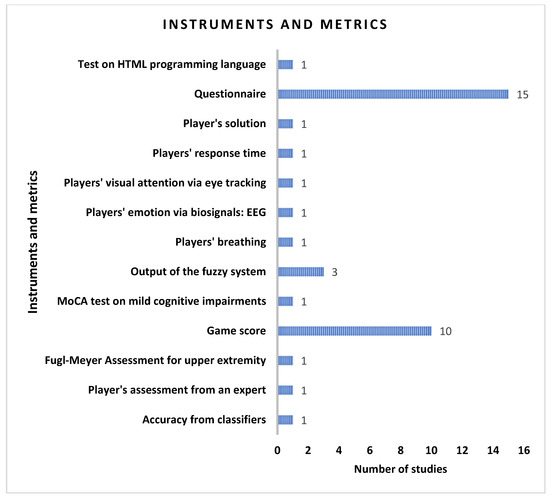

Instruments and metrics were used in most studies to assess their proposals (93%: 26 out of 28 studies). Most of them used questionnaires (58%: 15 out of 26 studies), followed by game score (38%: 10 out of 26 studies) as the instruments and metrics—see Figure 11. Other metrics included players’ aspects such as player’s solution [60], player’s response time [54], player’s emotion computed via electroencephalography signal [49], player’s visual attention computed via an eye tracker [62], player’s breathing [52], player’s assessment from an expert [69], test on the HTML programming language [57], MoCA test for identifying mild cognitive impairments [51], and Fugl–Meyer assessment to measure motor function in the upper extremity [50]. Other studies employed metrics related to the system implemented in the game: output of the fuzzy system [64,66,71] and accuracy from classifiers [50].

Figure 11.

Instruments and metrics used in the studies.

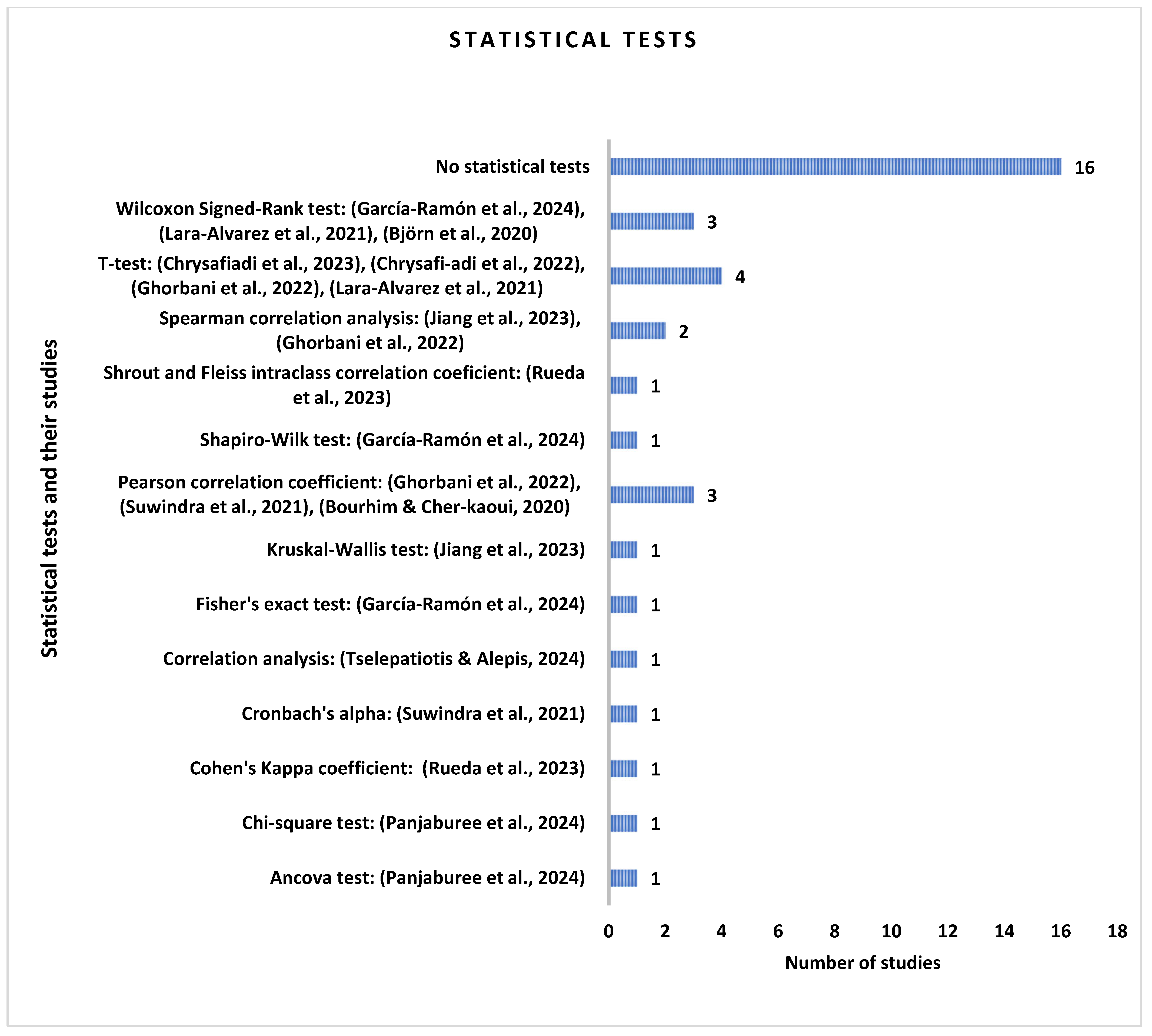

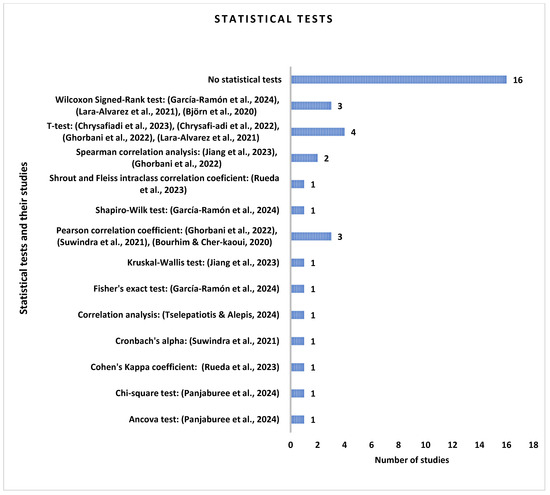

A key aspect of assessing the reliability of the findings in the studies is to conduct statistical analysis, as it helps ensure that results are not due to random variation. In this regard, it can be seen from Figure 12 that over half of the studies did not conduct a statistical analysis (57%: 16 out of 28 studies). Conversely, the most widely used statistical tests were the (i) t-test, which is a parametric statistical method used to assess whether there is a significant difference in a study variable between two treatment groups [51,54,56,57]; (ii) Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which is a non-parametric statistical test that uses ranks to determine whether there is a significant difference in a study variable between two paired treatment groups [49,54,68]; and (iii) Pearson correlation coefficient, which measures how strongly two study variables are related in a linear relationship [51,72,76]. Other statistical tests used to analyze the results were Spearman correlation, Shrout and Fleiss intraclass correlation, Cronbach’s alpha, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, Shapiro–Wilk, Kruskal–Wallis, Fisher’s exact test, Chi-square test, and ANCOVA test.

Figure 12.

Statistical tests used in the studies [49,50,51,54,56,57,62,68,69,70,72,76].

Focusing on the key findings, most studies reported overall positive outcomes related to their proposed approaches in terms of game performance, the effectiveness of the fuzzy logic system implemented in the study, positive player feedback, and improvements in the participants’ abilities developed through the game. Further details can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Experiments conducted in the studies.

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. Discussion on RQ1—What Is the Taxonomy of Serious Games Using Fuzzy Logic?

Over 80% of the studies implemented educational serious games. An unexpected finding was that only 20% of the studies focused on serious games in the health domain using fuzzy logic. Additionally, all the studies provided visual feedback to the players. It is important to note that 35.71% of the studies included auditory feedback as well. In this regard, a study [80] reported that a key aspect of game accessibility is providing feedback through several channels (visual, auditory, and tactile). Nevertheless, none of the studies provided tactile feedback for players.

Regarding the interaction method, the most widely used interaction methods in the serious games were mouse and keyboard (32%) and smartphone touch screens (32%), as expected. The most widely used platforms were desktops and laptops (50%), followed by smartphones (32%). Although virtual reality has become more affordable and accessible, few studies incorporated it into serious games. Similarly, only a few studies played the game using voice or body movements. A study [81] suggested that game design elements (e.g., platform) should be tailored to the player’s profile (e.g., gender, age, culture). For instance, this study reported that people aged 30–35 prefer to play games using consoles, while older adults prefer to play games using tablets and smartphones.

The Entertainment Software Association (ESA) publishes annual statistics on the video game industry in the United States, including aspects such as player perceptions and attitudes, behaviors and preferences, platforms used, motivations for playing, and the top games in the United States. In its 2025 report [82], the ESA presented data for six generations: Gen Alpha (ages 5–12), Gen Z (ages 13–28), Millennials (ages 29–44), Gen X (ages 45–60), Boomers (ages 61–79), and the Silent Generation (ages 80–90). According to the ESA, smartphones were the most widely used platform across all the generations. The second most used platforms were consoles in players aged 5–44 and PC in players aged 45–90.

Based on these findings, future directions for further research in terms of RQ1 could be as follows: (i) to implement serious games focusing on health that use fuzzy logic, so that linguistic variables could be used in the games that are commonly employed in medical environments; (ii) to provide auditory and haptic feedback in game interfaces; (iii) to implement serious games that could be played on various platforms (e.g., console, smartphone, PC, tablet), allowing players to choose their preferred platform; and (iv) to design serious games that allow players to select their preferred interaction method—whether traditional (mouse and keyboard) or alternative (voice, body movements).

4.2. Discussion on RQ2—What Are the Game Design Characteristics?

Regarding the game design, most studies implemented adventure game genres and narratives involving storytelling. However, a study [83] suggested that older adults over the age of 65 prefer casual games (i.e., games with simple interfaces and easy-to-learn game rules). Specifically, this study reported that older people prefer puzzle games, followed by action games. Additionally, player satisfaction is a key aspect of game usability. According to [84], game usability involves four key aspects: (i) learnability—how easy it is to understand the game rules the first time the game is played; (ii) efficiency—the ability of players to perform actions quickly after learning the game; (iii) errors—how easily players can recover from mistakes; and (iv) satisfaction—the degree of approval reported by the player.

Moreover, all the studies implemented games in which the control commands are executed in a fixed way. This reduces usability and accessibility, since players must adapt to predefined interfaces rather than adjusting controls to their own abilities. Based on [80], adaptive controls (i.e., the ability to remap commands and maximize compatibility with various control devices) should be provided to improve game accessibility. According to [85], game accessibility can be defined as “the ability to play a game even when functioning under limiting conditions. Limiting conditions can be functional limitations, or disabilities—such as blindness, deafness, or mobility limitations”. Evidence from accessibility research supports this. A scoping review [86] reported that flexible input methods, including remappable buttons and controls, and multiple interface options (e.g., joysticks, wearable sensors, and eye gaze tracking), can reduce barriers for players with motor or mobility limitations. These adaptive features allow players to adjust control configurations to reduce fatigue and better meet the needs of different players. Furthermore, the review [86] highlights the importance of integrating accessibility early in game production and indicates that flexible interfaces are essential for making games more inclusive. Similarly, a study [87] identified input remapping for game controls, as well as subtitles for spoken language, adjustable difficulty, and visual clarity, as key features to provide game accessibility for players with functional limitations. Based on these findings, opportunity areas for further research considering game usability and accessibility could be as follows: (i) to provide players with options to select their preferred game genre, which may increase satisfaction and overall usability; and (ii) to design tailored adaptive control interfaces, allowing several options to execute the same command. This would enable players to choose how to interact with the game based on their preferences and needs, thereby reducing inaccessibility.

4.3. Discussion on RQ3—What Is the Aim of Using Fuzzy Logic in Serious Games and How Is the Fuzzy Logic System Implemented?

Most studies (75%: 21 out of 28 studies) implemented fuzzy logic systems in the games involving fuzzification, fuzzy inference, and defuzzification. The remaining studies used only fuzzy sets in the games. Additionally, results showed that the triangular membership function was the most widely used function for converting the crisp inputs into linguistic variables during the fuzzification process (62%: 13 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems). In terms of the fuzzy inference, 90% of the studies (19 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems) used the Mamdani inference method. For defuzzification, the most widely used method to convert the fuzzy output into a crisp value was the center of the area, also known as the centroid method (38%: 8 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems).

Fuzzy logic has mainly been used in serious games to adjust game difficulty by modifying non-player character behavior (38% of the studies: 8 out of 21 studies using fuzzy inference systems).

It is worth noting that none of the studies reported the use of deblurring methods, which can influence visual clarity, immersion, and player comfort in gaming. According to [88], image deblurring is an image restoration process aimed at recovering a clear image from one that has been blurred by motion, defocus, or environmental factors. This review explained several deblurring methods used to restore images to a visually clear state (e.g., Wiener filter, Lucy–Richardson algorithm, convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks, and graph convolutional networks).

On the other hand, based on [80], game accessibility can be improved by (i) dynamically adjusting the game difficulty; (ii) maintaining player engagement by modifying the game scene (e.g., providing rewards, adding sensory effects); and (iii) tailoring the game interface to meet the player’s needs—suitable texts and reduced stimuli (e.g., reducing the brightness, adapting the font size, and font type).

Given the results of this study, future directions for further research using fuzzy logic in games could be as follows: (i) to increase player engagement by adjusting game difficulty using fuzzy logic systems that take physiological and behavioral input from the player (i.e., player’s emotions obtained through biosignals—eye gaze, electroencephalography signal, heart activity, electrodermal activity; player’s body movements for serious games focusing on rehabilitation that consider the range-of-motion of the movements based on age and medical condition); (ii) to implement fuzzy logic systems that adapt the game interface to the players’ needs (e.g., adjusting the font type and size, modifying audio levels, or changing colors to customize for visual or sensory preferences); and (iii) to integrate fuzzy logic with deblurring algorithms to improve gaming experiences.

4.4. Discussion on RQ4—Were Experiments Conducted in the Studies?

Approximately 79% of the studies included human participants in their experiments. Additionally, only 23% of these studies used small sample sizes, with fewer than 30 volunteers. Regarding the instruments and metrics, the most widely used instruments and metrics to assess the games were questionnaires (58%: 15 out of 26 studies), followed by game scores (38%: 10 out of 26 studies). It is important to note that only a few studies used physiological data to evaluate the games (i.e., player engagement computed via electroencephalography signals [49], player’s visual attention computed via an eye tracker [62], and player’s breathing [52]). Finally, it is worth noting that over half of the studies (57%: 16 out of 28 studies) did not conduct any statistical analysis on their results.

Based on these findings, opportunity areas in terms of RQ4 could be as follows: (i) to use instruments and metrics in the experiments that analyze physiological data; for instance, bio-signals (e.g., eye gaze, electroencephalography signal, heart activity, electrodermal activity) can provide more accurate insights into players’ emotional responses than relying only on questionnaires; and (ii) to conduct statistical analyses on the results using appropriate tests (e.g., correlation tests to determine associations between study variables, parametric or non-parametric tests to determine whether there is a significant difference in a study variable between study groups), so that the findings of the studies could be more reliable and ensure that results are not due to random chance.

4.5. Risk of Bias of the Studies

The JBI’s critical appraisal tool for Quasi-Experimental studies [89] was employed to assess the risk of bias of the 28 studies included in this review. Specifically, this tool consists of nine questions that analyze bias related to temporal precedence, to selection and allocation, to confounding factors, to administration of intervention/exposure, to assessment, detection, and measurement of the outcome, to participant retention, and to statistical conclusion validity. Each question can be answered using “Yes”, “No”, “Unclear”, and “N/A” (Not applicable). “Yes” was selected when the criterion was explicitly addressed and clearly met in the study. “No” was chosen when the information was available and showed that the criterion was not met, and “Unclear” was selected when the study did not provide enough information to make a judgment. All the studies described the cause-and-effect relationship (question 1: bias related to temporal precedence). Only a few studies (17.86%: 5 out of 28 studies [50,51,57,62,68]) included a control group in the experiments (question 2: bias related to selection and allocation). Regarding bias related to confounding factors (question 3), just over a quarter of the studies (28.57%: 8 out of 28 studies [50,52,55,56,57,68,73,74]) reported that participants in the comparisons were similar. For bias related to administration of intervention/exposure (question 4), almost half of the studies (42.85%: 12 out of 28 studies [49,50,51,52,56,57,59,63,69,70,73,74]) indicated that participants, apart from the intervention of interest, received similar conditions. With respect to bias related to assessment, detection, and measurement of the outcome, few studies (14.28%: 4 out of 28 studies [50,55,68,74]) conducted pre- and post-intervention measurements (question 5), most studies (60.71%: 17 out of 28 studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,63,68,69,70,72,74,76]) indicated that the outcomes of the participants were measured in the same way across the groups (question 6), and most studies (71.43%: 20 out of 28 studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,62,63,65,66,68,69,70,72,74,76]) explained the instruments used to measure the outcome reliably (question 7). In terms of bias related to participant retention, half of the studies (14 out of 28 studies [49,50,52,53,54,57,59,62,65,68,69,70,72,76]) indicated that the follow-up was completed or provided explanations for group differences due to participant dropout (question 8). Finally, almost half of the studies (42.85%: 12 out of 28 studies [49,50,51,54,56,57,62,68,69,70,72,76]) employed appropriate statistical analyses (question 9: statistical conclusion validity). Details on all nine questions of the tool were provided in only two studies [50,68]. Details on the results of this tool for each study are presented in Supplementary Material.

4.6. Limitations

This scoping review presents the following limitations:

- Single-reviewer bias. Only the author (EJRR) screened and assessed the articles; consequently, this might have introduced a risk of bias in the scoping review.

- Limitations associated to a scoping review. For instance, protocols for analyzing article quality (e.g., Qualsyst [90], quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS) [91]) used in systematic reviews were not applied. Therefore, there could be articles with low rates in terms of these protocols.

- Keyword limitations. The search terms were selected based on the most widely used and recognized terminology in the reviews presented in Table 1. Several keywords could be associated with ‘serious games.’ Based on [18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], ‘game’ and ‘serious game’ were included as search terms. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that studies using related terms such as ‘video games’, ‘gamification’, ‘digital games’, ‘computer games’, ‘technology’, ‘human-computer interaction’, or ‘application’ may have been excluded. Similarly, based on [16,27], ‘fuzzy logic’ was used as a search term to include fuzzy systems; consequently, studies referring to ‘fuzzy theory’, ‘fuzzy sets’, ‘neuro-fuzzy’, or ‘ANFIS’ (Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System) may have been excluded as well.

- Database access limitations. Although nine databases were consulted, not all the articles retrieved were accessible. Consequently, articles indexed in other databases or inaccessible were not considered.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review analyzed the state-of-the-art in serious games that use fuzzy logic. A total of 494 articles were retrieved through searches conducted in nine databases (ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, IOPscience, MDPI, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Springer, Wiley, and Web of Science). Of these, only 28 articles met the inclusion criteria. This study addressed four research questions. Regarding “RQ1—What is the taxonomy of serious games using fuzzy logic (i.e., application area, activity, modality, interaction method, environment, and hardware architecture)?”, it can be concluded that most of the serious games focused on education (80% of the studies), while the remaining studies addressed health applications. The majority of the studies used serious games in which the participants performed mental activity (89.28% of the studies). All games provided visual feedback, and only 37.21% of the studies included auditory feedback as well. The most widely used interaction methods were mouse and keyboard (32% of the studies) and smartphone touch screen (32% of the studies). Over half of the studies used 3D games (61%). Desktops and laptops were the most used platforms (50% of the studies) followed by smartphones (32% of the studies). Focusing on the “RQ2—What are the game design characteristics (i.e., game genre, narrative, and game rules—how is it played)?”, the results of this review showed that most of the studies (35.71%) implemented the adventure genre, including different storytelling elements (e.g., exploring a water village and an island with castles, understanding scenarios related to digital citizenship, and historical events), followed by the simulation genre, which involved several scenarios (e.g., urban planning, clinical situations, disaster mitigation) (33.33%). Regarding how the games were played, over half of the studies (64%) required participants to choose options or objects presented in the game interface. In terms of “RQ3—What is the aim of using fuzzy logic in serious games and how is the fuzzy logic system implemented (i.e., fuzzification, fuzzy inference, defuzzification)?”, this review found that most studies (75%) implemented fuzzy logic systems that involved fuzzification, fuzzy inference, and defuzzification processes. The triangular membership function was the most widely used method for fuzzifying data (62%: 13 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems). Mamdani inference was employed in 90% of the studies (19 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems), while the center of area method was the most widely applied technique for defuzzification (38%: 8 out of 21 studies using fuzzy logic systems). Fuzzy logic was applied in serious games for three key purposes: (i) adjusting game difficulty (38% of the studies: 8 out of 21 studies using fuzzy inference systems); (ii) providing tailored feedback within the game (19%: 4 out of 21 studies using fuzzy inference systems); and (iii) calculating game scores (14%: 3 out of 21 studies using fuzzy inference systems). Finally, with respect to “RQ4—Were experiments conducted in the studies (i.e., participants, instruments and metrics, key results, and statistical analysis)?”, this review identified that a total of 79% of the studies involved human participants in their experiments. Most of the studies employed instruments and metrics to assess their proposals (93%: 26 out of 28 studies). Questionnaires (58%: 15 out of 26 studies) and game scores (38%: 10 out of 26 studies) were the most widely used instruments and metrics in the studies. Nevertheless, over half of the studies (57%: 16 out of 28 studies) did not conduct any statistical analysis of their findings.

Several opportunity areas have been identified and discussed for each research question. Future work should focus on developing serious games that provide multimodal feedback—visual, auditory, and haptic channels—to players; designing tailored adaptive control interfaces that offer several choices to execute the same command; and implementing fuzzy logic systems that dynamically adjust game interfaces and game difficulty based on players’ needs and players’ physiological signals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/technologies13100448/s1, Table S1: JBI tool.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zyda, M. From Visual Simulation to Virtual Reality to Games. Computer 2005, 38, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Blažauskas, T. Serious Games and Gamification in Healthcare: A Meta-Review. Information 2023, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Sukjairungwattana, P.; Xu, W. Effects of Serious Games on Student Engagement, Motivation, Learning Strategies, Cognition, and Enjoyment. Int. J. Adult Educ. Technol. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.Y.A.; Huaycho, R.N.N.; Santos, F.I.Y.; Talavera-Mendoza, F.; Paucar, F.H.R. The Impact of Serious Games on Learning in Primary Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2023, 22, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Is There a Need for Fuzzy Logic? Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 2751–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negnevitsky, M. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide to Intelligent Systems, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA; Munich, Germany, 2004; ISBN 978-0-321-20466-0. [Google Scholar]

- Saatchi, R. Fuzzy Logic Concepts, Developments and Implementation. Information 2024, 15, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Han, J.; Shen, Q.; Angelov, P.P. Autonomous Learning for Fuzzy Systems: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 7549–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Garcia, A.J.D.S.; Castro, M.V.D.; Xerfan, S.D.; Ruas, G.; Negri, R.G. Fuzzy Machine Learning Applications in Environmental Engineering: Does the Ability to Deal with Uncertainty Really Matter? Sustainability 2024, 16, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhi, S.; Lam, S.; Ren, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Cai, J. Fuzzy Inference System with Interpretable Fuzzy Rules: Advancing Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Disease Diagnosis—A Comprehensive Review. Inf. Sci. 2024, 662, 120212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbosh, Q.A.; Aydogdu, O.; Farah, N.; Talib, M.H.N.; Salh, A.; Cankaya, N.; Omar, F.A.; Durdu, A. Review and Investigation of Simplified Rules Fuzzy Logic Speed Controller of High Performance Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 49377–49394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaus, M.M.; Anavatti, S.G.; Pratama, M.; Garratt, M.A. Towards the Use of Fuzzy Logic Systems in Rotary Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, B.N.; Balducci, P.; Passos, R.P.; Novelli, C.; Fileni, C.H.P.; Vieira, F.; Camargo, L.B.D.; Vilela Junior, G.D.B. Artificial Intelligence Based on Fuzzy Logic for the Analysis of Human Movement in Healthy People: A Systematic Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambalimath, S.; Deka, P.C. A Basic Review of Fuzzy Logic Applications in Hydrology and Water Resources. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentout, A.; Maoudj, A.; Aouache, M. A Review of the Literature on Fuzzy-Logic Approaches for Collision-Free Path Planning of Manipulator Robots. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 3369–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Guerrero, J.; Romero, F.P.; Olivas, J.A. Fuzzy Logic Applied to Opinion Mining: A Review. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 222, 107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishtha, S.; Gupta, V.; Mittal, M. Sentiment Analysis Using Fuzzy Logic: A Comprehensive Literature Review. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. 2023, 13, e1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Ratcliffe, G. Serious Games, Gamification, and Serious Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, A.; Laugharne, R.; Shankar, R. Therapeutic Use of Serious Games in Mental Health: Scoping Review. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, V.; Wilkey, J.; Opdebeeck, C. Outcome Measurement of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Serious Digital Games: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubin, O.; Alnajjar, F.; Al Mahmud, A.; Jishtu, N.; Alsinglawi, B. Exploring Serious Games for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsiana, E.; Ladakis, I.; Fotopoulos, D.; Chytas, A.; Kilintzis, V.; Chouvarda, I. Serious Gaming Technology in Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e19071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, W.; Kan, X.; et al. Application of Serious Games in Health Care: Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 896974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Wilson, P.; Abraham, O. Investigating the Use of Serious Games for Cancer Control Among Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e58724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Miranda, J.; Espinosa-Curiel, I.E. Serious Games Supporting the Prevention and Treatment of Alcohol and Drug Consumption in Youth: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e39086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, E.F.H.; De Vries, R.; Wouters–Van Poppel, P.C.M.; Van Riel, N.A.W.; Haak, H.R. Serious Digital Games for Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Its Current State, Accessibility, and Functionality for Patients and Healthcare Providers. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 216, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-alrazaq, A.; Abuelezz, I.; Hassan, A.; AlSammarraie, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Irshaidat, S.; Abu Serhan, H.; Ahmed, A.; Alabed Alrazak, S.; Househ, M. Artificial Intelligence–Driven Serious Games in Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e39840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolks, D.; Schmidt, J.J.; Kuhn, S. The Role of AI in Serious Games and Gamification for Health: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e48258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamarti, F.; Eid, M.; El Saddik, A. An Overview of Serious Games. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2014, 2014, 358152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lope, R.P.; Medina-Medina, N. A Comprehensive Taxonomy for Serious Games. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2017, 55, 629–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, J.C. Joystick Nation: How Videogames Ate Our Quarters, Won Our Hearts, and Rewired Our Minds, 1st ed.; Little, Brown, and Co: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-316-36007-4. [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA-P Group; Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, M.Z.-E.-A.; Borst, C.W.; Achour, N. Fuzzy Logic Classifier and Conditional Responses Algorithm for Gestural Input Game. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV), Fez, Morocco, 9–11 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Andrigueto, G.R.; Araujo, E. Fuzzy Aggressive Behavior Assessment of Toxic Players in Multiplayer Online Battle Games. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Beke, A.; Kumbasar, T. Type-2 Fuzzy Logic-Based Linguistic Pursuing Strategy Design and Its Deployment to a Real-World Pursuit Evasion Game. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeppani, A.; Yan Sofiyan, Y. Artificial Intelligence in the Game to Respond Emotion Using Fuzzy Text and Logic. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Pangkal, Indonesia, 23–24 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, I.; Kumbasar, T. Catch Me If You Can: A Pursuit-Evasion Game with Intelligent Agents in the Unity 3D Game Environment. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Istanbul, Turkey, 25–27 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Haryanto, H.; Kardianawati, A.; Rosyidah, U.; Astuti, E.Z.; Dolphina, E. Fuzzy-Based Dynamic Reward for Discovery Activity in Appreciative Serious Game. In Proceedings of the 2021 Sixth International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Jakarta, Indonesia, 3–4 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Killedar, T.; Suriya, G.; Sharma, P.; Rathor, M.; Gupta, A. Fuzzy Logic for Video Game Engagement Analysis Using Facial Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 26–27 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 481–485. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ruiz, M.A.; Santana-Mancilla, P.C.; Gaytan-Lugo, L.S.; Aquino-Santos, R.T. Smelling on the Edge: Using Fuzzy Logic in Edge Computing to Control an Olfactory Display in a Video Game. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG), Beijing, China, 21–24 August 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 508–511. [Google Scholar]

- Arunakumari, B.N.; Ravikumar, S.; Jason, V.; Sarika, T.A.; Adnan, S.; Thippeswamy, G. Use of Propositional Logic in Building AI Logic and Game Development. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Michail, T.; Alepis, E. Design of Real-Time Multiplayer Word Game for the Android Platform Using Firebase and Fuzzy Logic. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), Volos, Greece, 10–12 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Annisa Damastuti, F.; Firmansyah, K.; Miftachul Arif, Y.; Dutono, T.; Barakbah, A.; Hariadi, M. Dynamic Level of Difficulties Using Q-Learning and Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 137775–137789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyr, S.; Tolganay, C. Affective Computing Methods for Simulation of Action Scenarios in Video Games. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 231, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, P.; Akram, A.; Shamoi, P. Fuzzy Approach for Audio-Video Emotion Recognition in Computer Games for Children. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 231, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świechowski, M. Fuzzy Utility AI for Handling Uncertainty in Video Game Bots Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Paraschos, P.D.; Koulouriotis, D.E. Fuzzy Logic-Based Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment for Adaptive Game Environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramón, R.D.; Rechy-Ramirez, E.J.; Alonso-Valerdi, L.M.; Marin-Hernandez, A. Engagement Analysis Using Electroencephalography Signals in Games for Hand Rehabilitation with Dynamic and Random Difficulty Adjustments. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, T.; Ma, M.; Tang, M.; Chai, Y. A Serious Game System for Upper Limb Motor Function Assessment of Hemiparetic Stroke Patients. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 2640–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Farshi Taghavi, M.; Delrobaei, M. Towards an Intelligent Assistive System Based on Augmented Reality and Serious Games. Entertain. Comput. 2022, 40, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Cibrian, F.L.; Castro, L.A.; Tentori, M. An Adaptive Model to Support Biofeedback in AmI Environments: A Case Study in Breathing Training for Autism. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 2022, 26, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz Hutama, B.A.; Sihwi, S.W.; Salamah, U. Kinect Based Therapy Games to Overcome Misperception in People with Dysgraphia Using Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computing (ICOCO), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–19 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Alvarez, C.; Mitre-Hernandez, H.; Flores, J.J.; Perez-Espinosa, H. Induction of Emotional States in Educational Video Games Through a Fuzzy Control System. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 12, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, D.; Quintero M., C. G. Intelligent System for Interactive Teaching through Videogames. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Kamitsios, M.; Virvou, M. Fuzzy-Based Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment of an Educational 3D-Game. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 27525–27549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Papadimitriou, S.; Virvou, M. Cognitive-Based Adaptive Scenarios in Educational Games Using Fuzzy Reasoning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 250, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Papadimitriou, S.; Virvou, M. Fuzzy States for Dynamic Adaptation of the Plot of an Educational Game in Relation to the Learner’s Progress. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Piraeus, Greece, 15–17 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Krouska, A.; Troussas, C.; Voutos, Y.; Mylonas, P.; Sgouropoulou, C. Optimizing Player Engagement in an Educational Virtual Game through Fuzzy Logic-Based Challenge Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Piraeus, Greece, 10–12 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guniš, J.; Šnajder, L.; Antoni, L.; Eliaš, P.; Krídlo, O.; Krajči, S. Formal Concept Analysis of Students’ Solutions on Computational Thinking Game. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2025, 68, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Wang, M.-H.; Kuan, W.-K.; Ciou, Z.-H.; Kubota, N. AI-FML Agent for Robotic Game of Go and AIoT Real-World Co-Learning Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Panjaburee, P.; Hwang, G.-J.; Intarakamhang, U.; Srisawasdi, N.; Chaipidech, P. Effects of a Personalized Game on Students’ Outcomes and Visual Attention during Digital Citizenship Learning. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2351275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jondya, A.G.; Susanto, K.F. Cathleen Utilizing Simple Fuzzy Logic into An Adaptive Storytelling Mobile Game in Learning Historical Event of Indonesia’s Independence Movement. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on New Media Studies (CONMEDIA), Bali, Indonesia, 6–8 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, A.; Susiki, S.M.; Yuniarno, E.M. Implementation of Fuzzy Logic for Determining the Level Score Historical Character Recognition Puzzle Educational Game. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Seminar on Intelligent Technology and Its Applications (ISITIA), Surabaya, Indonesia, 20–21 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Purnamasari, P.O.D.A.; Yuniarno, E.M.; Supeno Mardi, S.N. Score Prediction for Game Aksara Using Fuzzy Mamdani. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (iSemantic), Semarangin, Indonesia, 18–19 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, J.I.; Ponce, P.; Meier, A.; Peffer, T.; Mata, O.; Molina, A. Empower Saving Energy into Smart Communities Using Social Products with a Gamification Structure for Tailored Human–Machine Interfaces within Smart Homes. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 1363–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, P.; Meier, A.; Méndez, J.I.; Peffer, T.; Molina, A.; Mata, O. Tailored Gamification and Serious Game Framework Based on Fuzzy Logic for Saving Energy in Connected Thermostats. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björn, M.H.; Laurila, J.M.; Ravyse, W.; Kukkonen, J.; Leivo, S.; Mäkitalo, K.; Keinonen, T. Learning Impact of a Virtual Brain Electrical Activity Simulator Among Neurophysiology Students: Mixed-Methods Intervention Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e18768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, A.J.; Martínez-Cruz, C.; Díaz-Fernández, Á.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C. Flexible Evaluation of Electrotherapy Treatments for Learning Purposes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 219, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselepatiotis, M.; Alepis, E. Adaptive Learning in Mobile Serious Games: A Personalized Approach Using AI for General Knowledge Quizzes. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), Chania Crete, Greece, 17–19 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Haryanto, H.; Kardianawati, A.; Rosyidah, U.; Mulyanto, E.; Sutojo, T. Fuzzy Adaptive Items in Design Activity of Appreciative Serious Game. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), Bandung, Indonesia, 10–11 August 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhim, E.M.; Cherkaoui, A. Efficacy of Virtual Reality for Studying People’s Pre-Evacuation Behavior under Fire. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 142, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chai, Y. Modeling Quick Autonomous Response for Virtual Characters in Safety Education Games. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2024, 88, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, Z.C.; Machado, L.S.; De Toledo Vianna, R.P.; De Moraes, R.M. A Fuzzy Set-Based Model for Educational Serious Games with 360-Degree Videos. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2023, 2023, 4960452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian, P.; Azadi, S.; Bai, N.; De Andrade, B.; Abu Zaid, N.; Rezvani, S.; Pereira Roders, A. EquiCity Game: A Mathematical Serious Game for Participatory Design of Spatial Configurations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwindra, I.N.P.; Putra, I.K.G.D.; Sudarma, M.; Sastra, N.P. Effectiveness of Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System for Predicting Player Character in the Balinese Serious Game Model. Int. J. Fuzzy Log. Intell. Syst. 2021, 21, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.R.; Machado, L.S.; Medeiros, A.T.; Coelho, H.F.C.; Andrade, J.M.; Moraes, R.M. The Caixa de Pandora Game: Changing Behaviors and Attitudes toward Violence against Women. Comput. Entertain. 2018, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingkavara, T.; Panjaburee, P.; Srisawasdi, N.; Sajjapanroj, S. The Use of a Personalized Learning Approach to Implementing Self-Regulated Online Learning. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorn, M.; Ravyse, W.; Villafruella, D.S.; Luimula, M.; Leivo, S. Higher Education Learner Experience with Fuzzy Feedback in a Digital Learning Environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 000253–000260. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva-Zamora, M.Á.; Mangiron, C. How to Create Video Games with Cognitive Accessibility Features: A Literature Review of Recommendations. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 2805–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, C.S.; Toledo-Delgado, P.A.; Muñoz-Cruz, V.; Arnedo-Moreno, J. Gender and Age Differences in Preferences on Game Elements and Platforms. Sensors 2022, 22, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entertainment Software Association Essential Facts About the U.S. Video Game Industry 2025. Available online: https://www.theesa.com/resources/essential-facts-about-the-us-video-game-industry/2025-data/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Chesham, A.; Wyss, P.; Müri, R.M.; Mosimann, U.P.; Nef, T. What Older People Like to Play: Genre Preferences and Acceptance of Casual Games. JMIR Serious Games 2017, 5, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio, R.R.; Acosta, C.O.; Cortez, J.; Morán, A.L. Usability Perception of Different Video Game Devices in Elderly Users. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 16, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierre, K.; Hinn, M.; Martin, T.; McIntosh, M.; Snider, T.; Stone, K.; Westin, T. IGDA Accessibility in Games: Motivations and Approaches; The International Game Developers Association: 2004. Available online: https://g3ict.org/publication/igda-accessibility-in-games-motivations-and-approaches (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- O’Mara, B.; Harrison, M.; Harley, K.; Dwyer, N. Making Video Games More Inclusive for People Living with Motor Neuron Disease: Scoping Review. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 11, e58828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.L. The Ground Floor Approach to Video Game Accessibility: Identifying Design Features Prioritized by Accessibility Reviews. Games Cult. 2025, 20, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. Image Deblurring: Comparison and Analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2634, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Hasanoff, S.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias Quasi-Experimental Studies. JJBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004; ISBN 978-1-896956-77-0. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardner, P.; Lawton, R. Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS): An Appraisal Tool for Methodological and Reporting Quality in Systematic Reviews of Mixed- or Multi-Method Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).