Howzat? The Financial Health of English Cricket: Not Out, Yet

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“£200,000 of ticket revenue would have been double the amount derived from any other competition. It was a proper cash cow to those smaller grounds and a life saver. Without Twenty20 at a professional level the domestic game in this country would be in a very precarious state by now.”

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. On Truth and Fairness in Accounting Policies

2.2. The Economic Theory of Professional Team Sport

3. The County Championship

“The beginning of every new cricket season brings with it reports of county cricket in demise, accompanied by pictures of a solitary, cold supporter in a stand, surrounded by rows of empty plastic seats. It is the stereotypical image of county cricket watched by a man and a dog, and of its impending death - killed by public apathy and crippling financial issues. For as long as I can remember, people have been prophesying the death of county cricket”

4. Methods

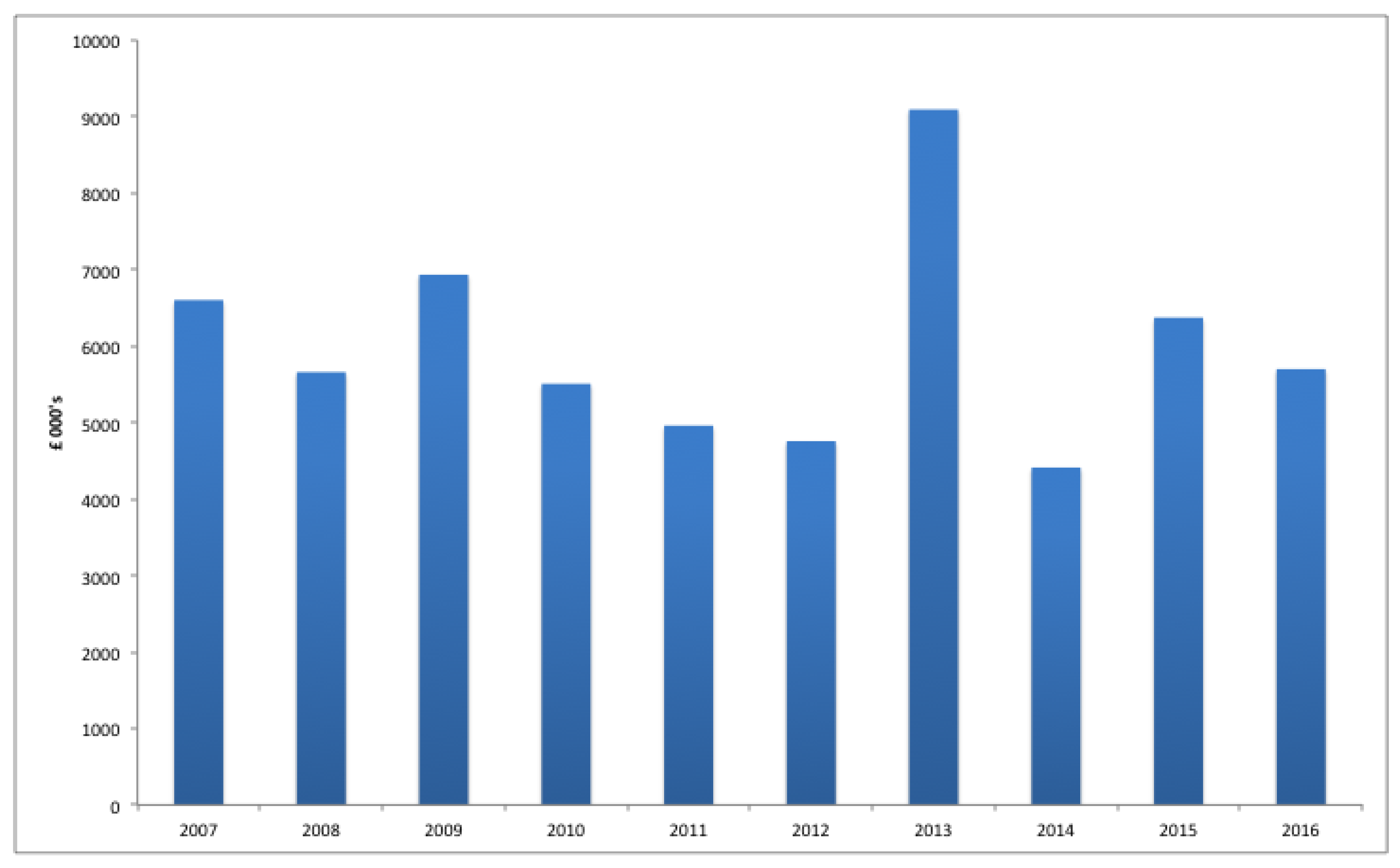

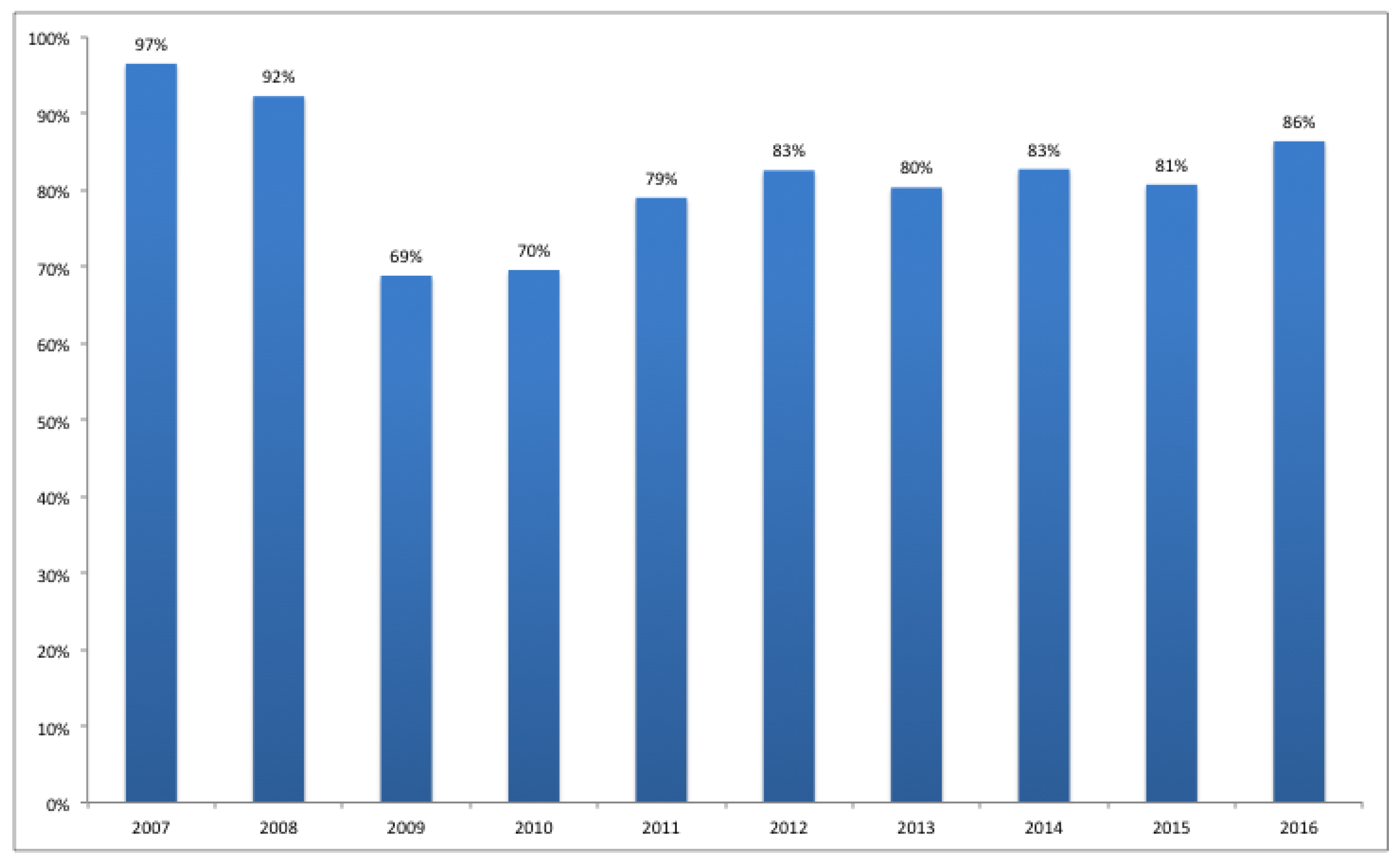

5. Financial Health

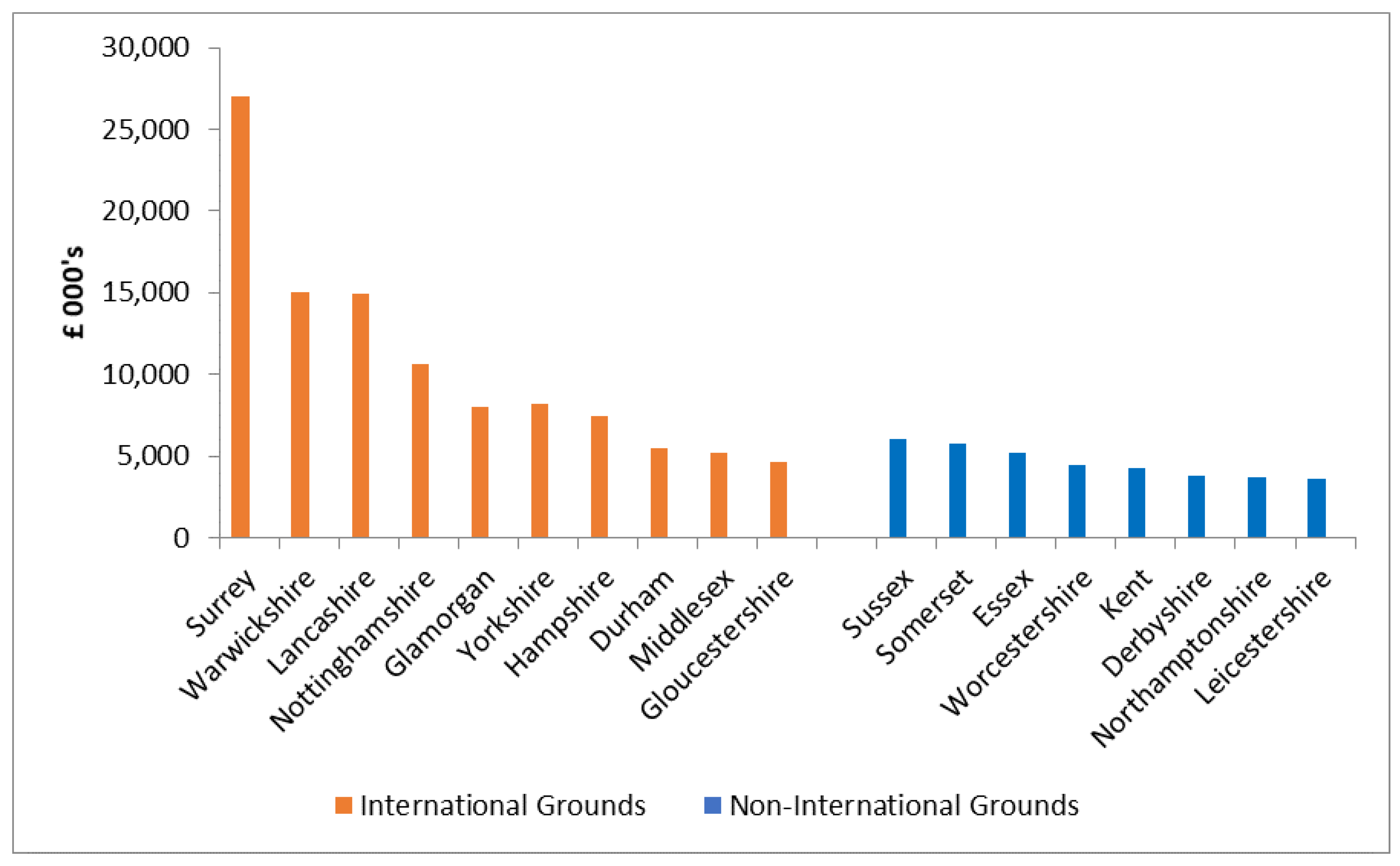

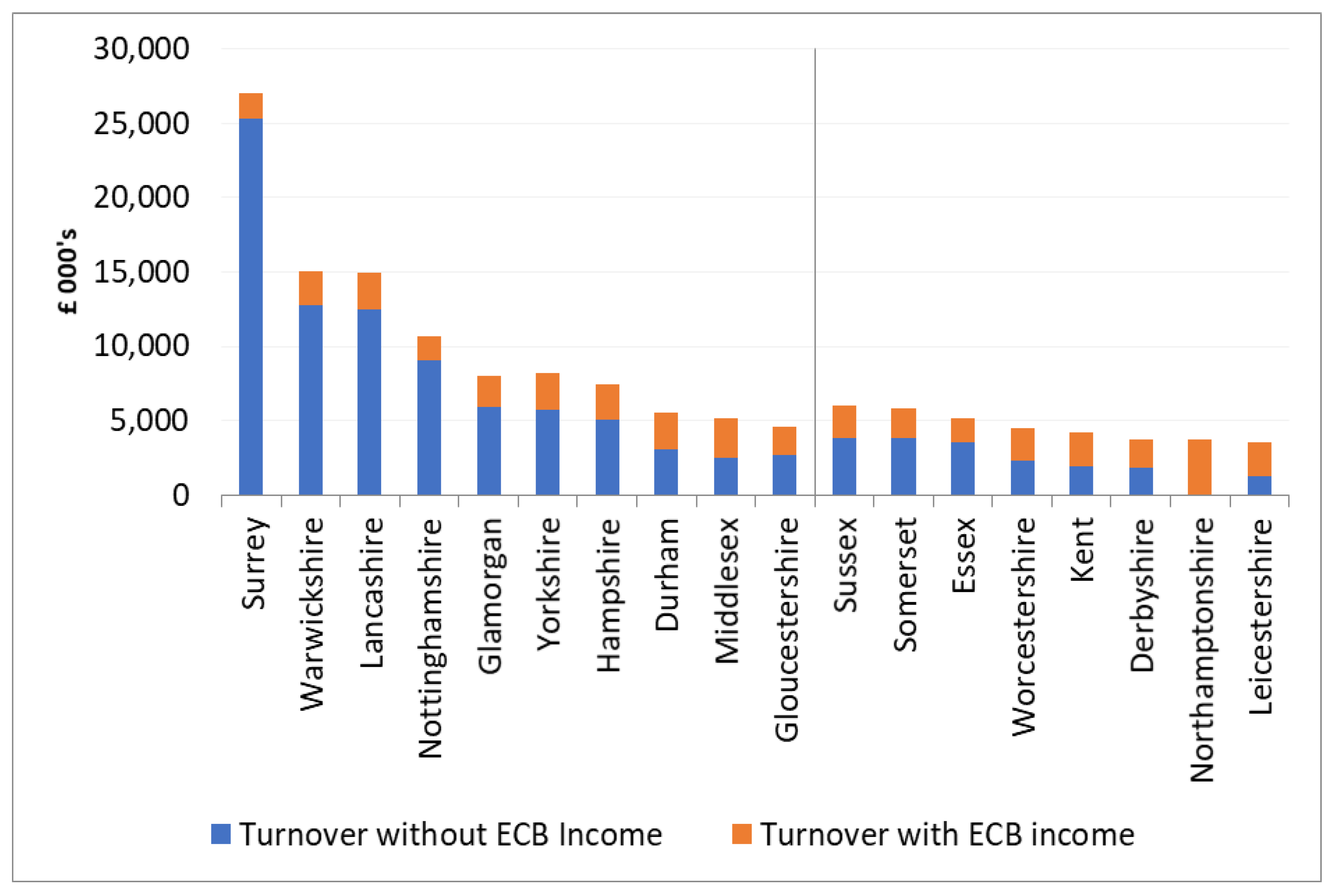

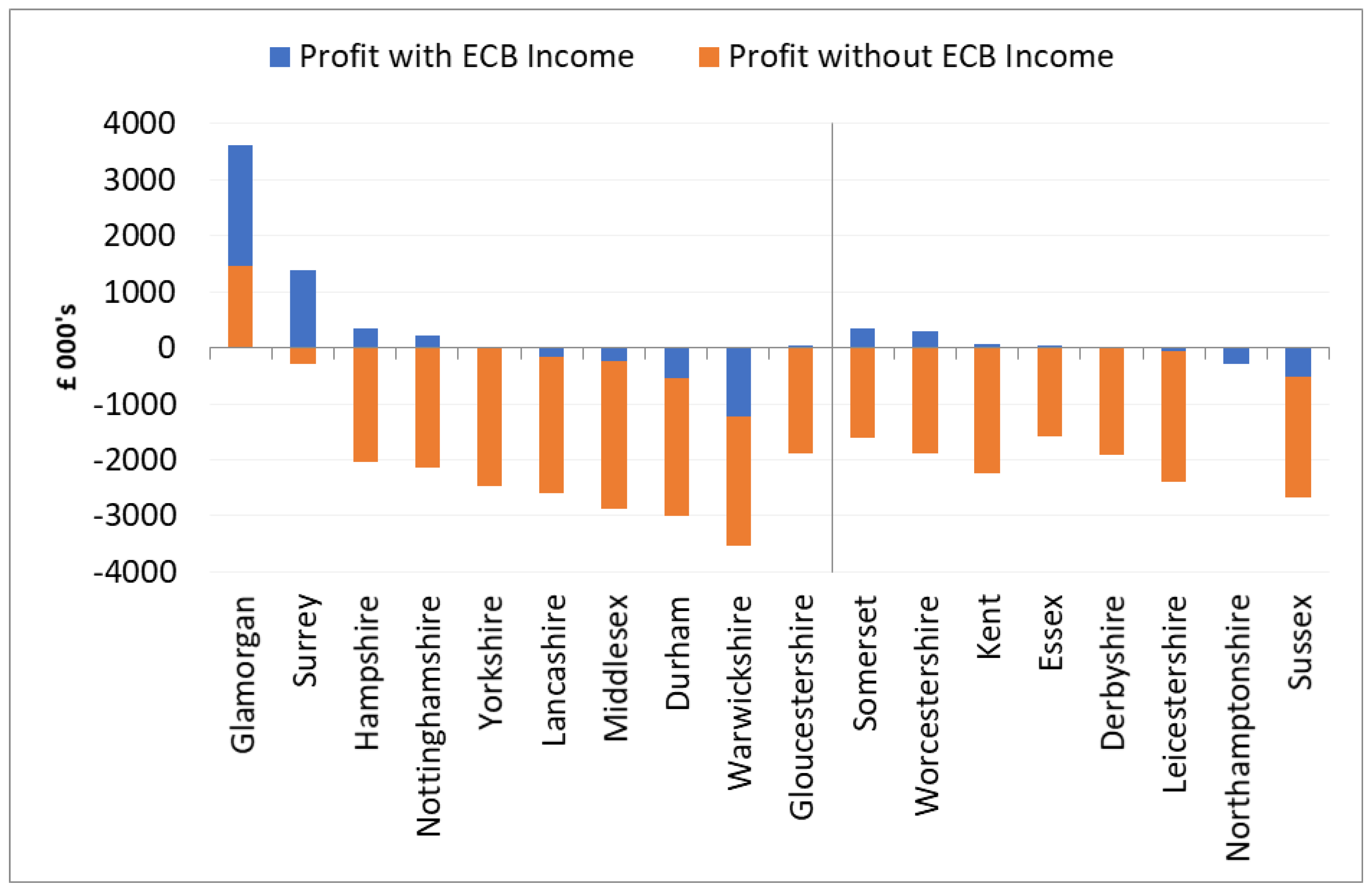

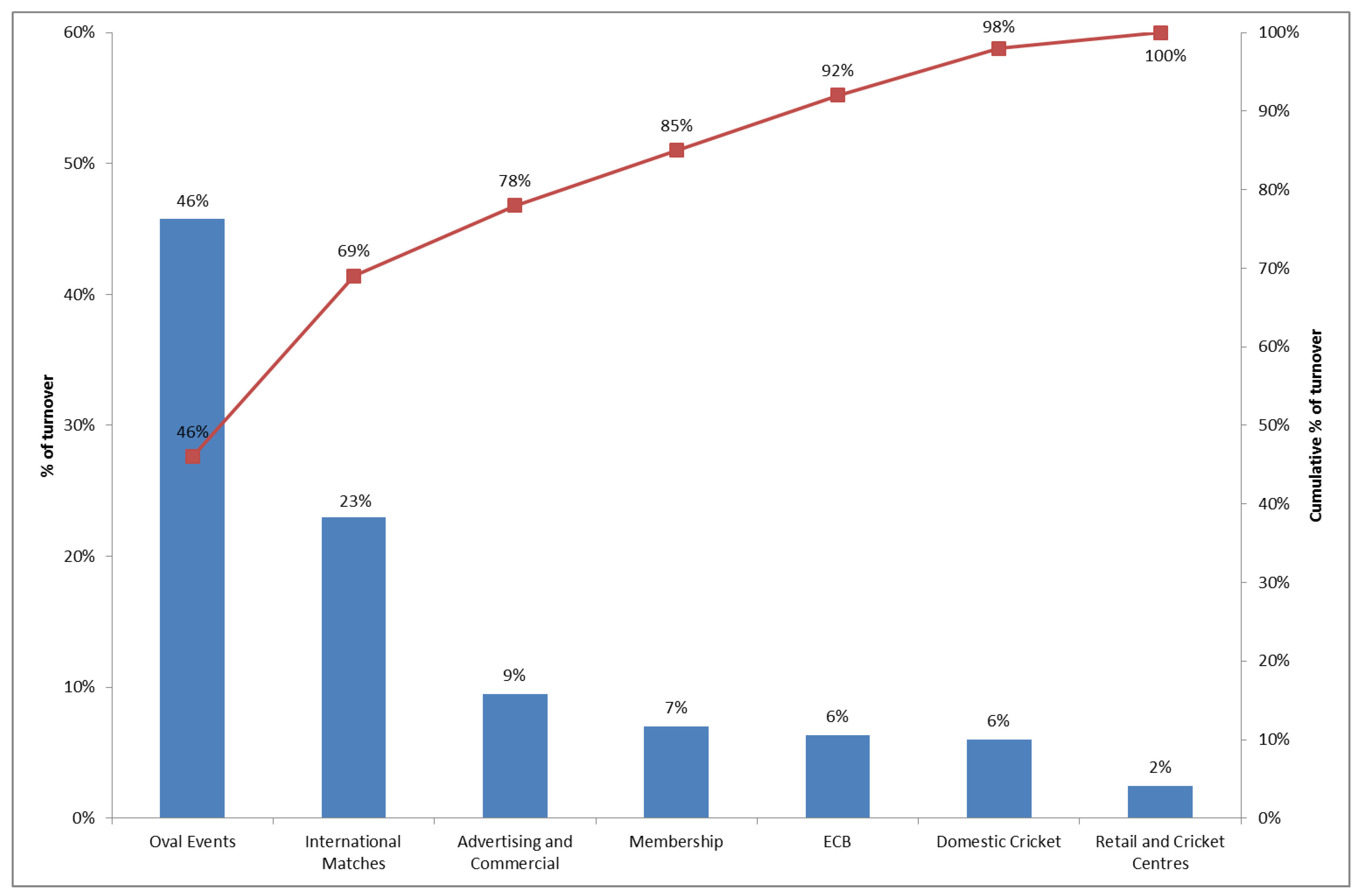

5.1. Dominating the Game

5.2. Contrasting Fortunes

5.3. How Does This Compare with 1997?

5.4. What Can Cricket Do to Improve Its Position?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammon, Elizabeth. 2017. Available online: http://www.espn.co.uk/cricket/story/_/id/19064584/elizabeth-ammonstate-english-county-cricket (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Andreff, Wladimir, and Paul D. Staudohar. 2000. The Evolving Model of Professional Sports Finance. Journal of Sports Economics 1: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreff, Wladimir. 2007. French Football: A Financial Crisis Rooted in Weak Governance. Journal of Sports Economics 8: 652–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlev, Benzion, and Joshua Rene Haddad. 2003. Fair value accounting and the management of the firm. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 14: 383–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Carlos Pestana. 2006. Portuguese Football. Journal of Sports Economics 7: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 2018. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/cricket/43211323 (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Bevis, Herman W. 1965. Corporate Financial Reporting in a Competitive Economy. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, Richard J. 1989. Beyond the objectivist and the subjectivist: Learning to read accounting as text. Accounting, Organizations and Society 14: 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Peter, and Neil Cocks. 1989. Critical research issues in accounting standard setting. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 17: 511–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromwich, Michael. 2007. Fair values: Imaginary prices and mystical markets—A clarificatory review. In The Routledge Companion to Fair Value and Financial Reporting. Edited by Peter Walton. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Buraimo, Babatunde, Bernd Frick, Michael Hickfang, and Rob Simmons. 2015. The economics of long-term contracts in the footballers’ labour market. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraimo, Babatunde, Rob Simmons, and Stefan Szymanski. 2006. English Football. Journal of Sports Economics 7: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, Gibson. 1987. No accounting for sexuality. Accounting, Organizations and Society 12: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Simon. 2009. From outside lane to inside track: sport management research in the twenty-first century. Management Decision 47: 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, Helmut M., and Egon Franck. 2007. Governance Failure and Financial Crisis in German Football. Journal of Sports Economics 8: 662–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, Stephen, and John A. Goddard. 2011. The Economics of Football, 2nd ed. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durham CCC. 2015. Annual Report and Accounts. Durham: Durham CCC. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Cheng-Min, and Rong-Tsu Wang. 2000. Performance evaluation for airlines including the consideration of financial ratios. Journal of Air Transport Management 6: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, Rodney. 2015. Managerial objectives: A retrospective on utility maximization in pro team sports. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-del-Barrio, Pedro, and Stefan Szymanski. 2009. Goal! Profit maximisation versus win maximisation in soccer. Review of Industrial Organisation 34: 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Omiros, and Lisa Jack. 2011. In pursuit of legitimacy: A history behind fair value accounting. The British Accounting Review 43: 311–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Amit. 2004. The globalization of cricket: The rise of the non-West. The International Journal of the History of Sport 21: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, Ruth D. 1991. The FASB’s conceptual framework, financial accounting and the maintenance of the social world. Accounting, Organizations and Society 16: 313–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitz, Joerg-Markus. 2007. The decision usefulness of fair value accounting—A theoretical perspective. European Accounting Review 16: 323–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, Thomas, and Stefan Szymanski. 1999. The Americanization of European Football. Economic Policy 28: 205–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, Vincent, Patrick Massey, and Shane Massey. 2013. Competitive balance and match attendance in European rugby union leagues. The Economic and Social Review 44: 425–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, Anthony G. 1990. Accounting and organization change. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 3: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International GAAP. 2005. Generally Accepted Accounting Practices under International Financial Reporting Standards. London: LexisNexis. [Google Scholar]

- Kesenne, Stefan. 2000. Revenue Sharing and Competitive Balance in Professional Team Sports. Journal of Sports Economics 1: 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesenne, Stefan. 2015. Revenue sharing and absolute league quality: Talent investment and talent allocation. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, Christian, and Christian Leuz. 2009. The crisis of fair value accounting: Making sense of the recent debate. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34: 826–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Stephanie, and Stefan Szymanski. 2015. Making money out of football. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Peter, and Ted O’Leary. 1987. Accounting and the construction of the governable person. Accounting, Organizations and Society 12: 235–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, Walter C. 1964. The peculiar economics of professional sports. Quarterly Journal of Economics 78: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Danny, and Trevor Slack. 1999. Deinstitutionalising the amateur ethic: An empirical examination of change in a rugby union football club. Sport Management Review 2: 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Danny, and Trevor Slack. 2003. An analysis of change in an organizational field: The professionalization of English rugby union. Journal of Sport Management 17: 417–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumley, Daniel, Robert Wilson, and Simon Shibli. 2017. A holistic performance analysis of English professional football clubs 1992–2013. Journal of Applied Sport Management 9: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikvar, Nina, Maks Tajnikar, and Ksenja Pušnik. 2009. Performance ratios for managerial decision-making in a growing firm. Journal of Business Economics and Management 10: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, Adrian. 2016. It’s not just cricket—The portfolios of the English/Welsh cricket teams. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 6: 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Alan J. 1987. Accounting as a legitimating institution. Accounting, Organizations and Society 12: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, Hemanta, Dibyojyoti Bhattacharjee, and Atanu Bhattacharjee. 2013. Performance based market valuation of cricketers in IPL. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 3: 127–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli, S., and G. J. Wilkinson-Riddle. 1997. The financial health of English Cricket—An analysis based upon the 1995 annual reports and financial statements of the 18 first class counties. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 4: 4–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Peter J. 1971. The Economics of Professional Football: The Football Club as a Utility Maximiser. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 17: 121–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, Peter J. 2006. Rottenberg and the economics of sports after 50 years. In Sports Economics after 50 Years. Edited by Placido Rodriguez, Stefan Kesenne and Jaume Garcia. Essays in Honour of Simon Rottenberg. Spain: University of Oviedo, pp. 211–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Peter J. 2015. The economics of professional football revisited. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, Toshiyuki. 2005. Financial Ratio Analysis of the electric power industry. Asia-Pacific Journal of Operational Research 22: 349–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunder, Shyam. 2016. Better financial reporting: meanings and means. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 35: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrey CCC. 2018. Annual Report and Accounts. Surrey: Surrey CCC. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski, Stefan, and Andrew S. Zimbalist. 2005. National Pastime: How Americans Play Baseball and the Rest of the World Plays Soccer. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski, Stefan, and Tim Kuypers. 1999. Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football. London: Viking Books. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski, Stefan. 2003. The Economic Design of Sporting Contests. Journal of Economic Literature 41: 1137–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ECB. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecb.co.uk/news/623583/where-will-major-matches-be-played-from-2020 (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- The Guardian. 2017a. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/feb/20/ipl-auction-ben-stokes-sets-record-tymal-mills-indian-premier-league (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- The Guardian. 2017b. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/jun/30/live-cricket-return-bbc-twenty20-tournament (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- The Independent. 2017. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/cricket/t20-twenty20-new-tournament-natwest-blast-love-it-hate-domestic-game-back-from-brink-a8291796.html (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- The Telegraph. 2018. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/cricket/2017/06/30/game-changing-tv-deal-sky-bbc-will-broaden-crickets-appeal-says/ (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Tinker, Tony. 1988. Panglossian accounting theories: The science of apologising in style. Accounting, Organizations and Society 13: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrooman, John. 2015. Sportsman leagues. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 62: 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Peter. 2012. Any given Saturday: Competitive balance in elite English rugby union. Managing Leisure 17: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, Hugh. 1986. Organising the profession: A theoretical and historical examination of the development of the major accounting bodies in the UK. Accounting, Organizations and Society 11: 555–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Rob, and Daniel Plumley. 2017. Different shaped ball, same financial problems? A holistic performance assessment of English Rugby Union (2006–2015). Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 7: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Rob, Daniel Plumley, and David Barrett. 2015. Staring into the abyss? The state of UK rugby’s Super League. Managing Sport and Leisure 20: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Robert, Daniel Plumley, and Girish Ramchandani. 2013. The relationship between ownership structure and club performance in the English Premier League. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 3: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, April L., and Raymond F. Zammuto. 2013. Creating opportunities for institutional entrepreneurship: The Colonel and the Cup in English County Cricket. Journal of Business Venturing 28: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plumley, D.; Wilson, R.; Millar, R.; Shibli, S. Howzat? The Financial Health of English Cricket: Not Out, Yet. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2019, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7010011

Plumley D, Wilson R, Millar R, Shibli S. Howzat? The Financial Health of English Cricket: Not Out, Yet. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2019; 7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7010011

Chicago/Turabian StylePlumley, Daniel, Rob Wilson, Robbie Millar, and Simon Shibli. 2019. "Howzat? The Financial Health of English Cricket: Not Out, Yet" International Journal of Financial Studies 7, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7010011

APA StylePlumley, D., Wilson, R., Millar, R., & Shibli, S. (2019). Howzat? The Financial Health of English Cricket: Not Out, Yet. International Journal of Financial Studies, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7010011