Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in the Post-COVID Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Malta

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic Profile and Vaccine Uptake

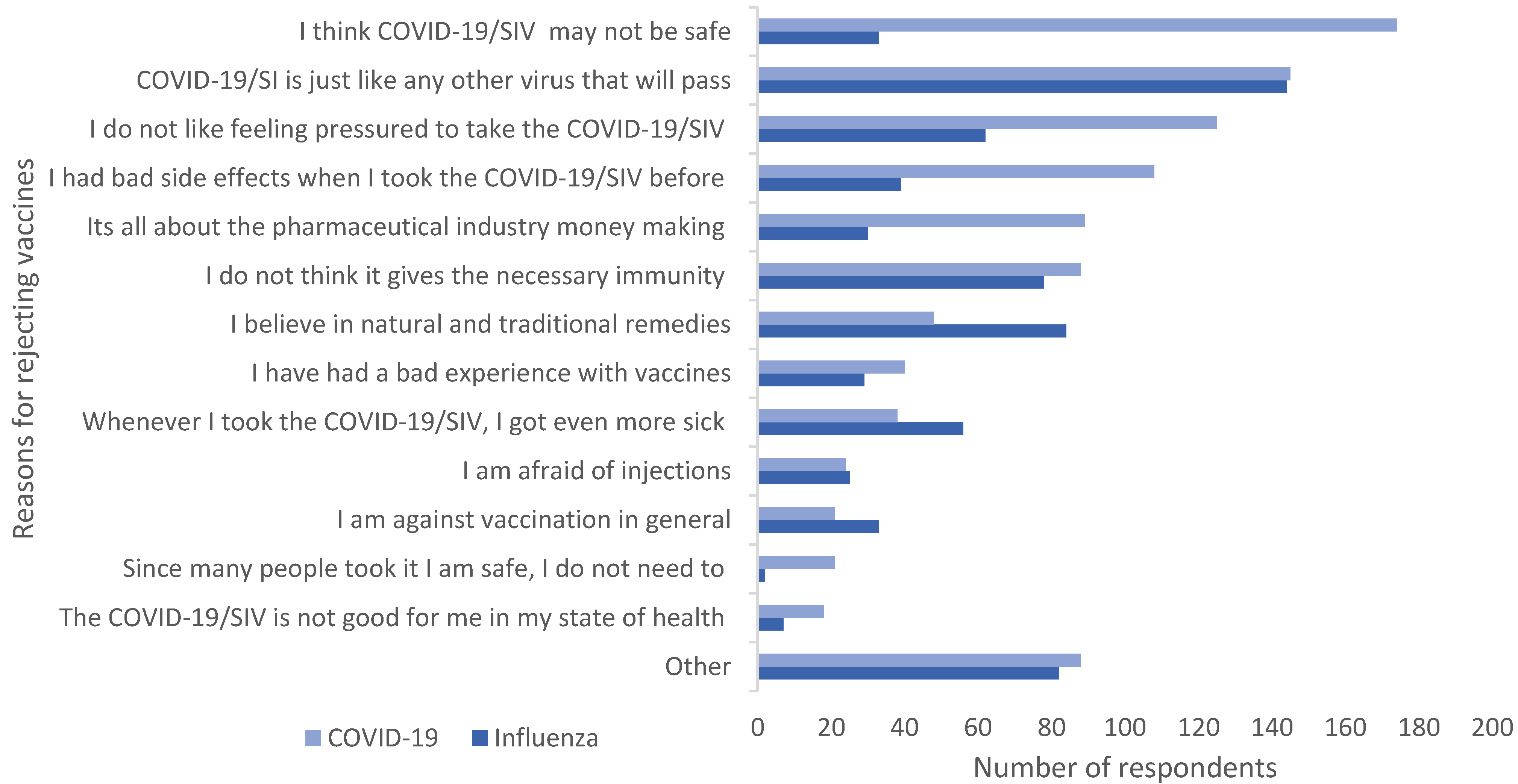

3.2. Reasons for Vaccine Rejection

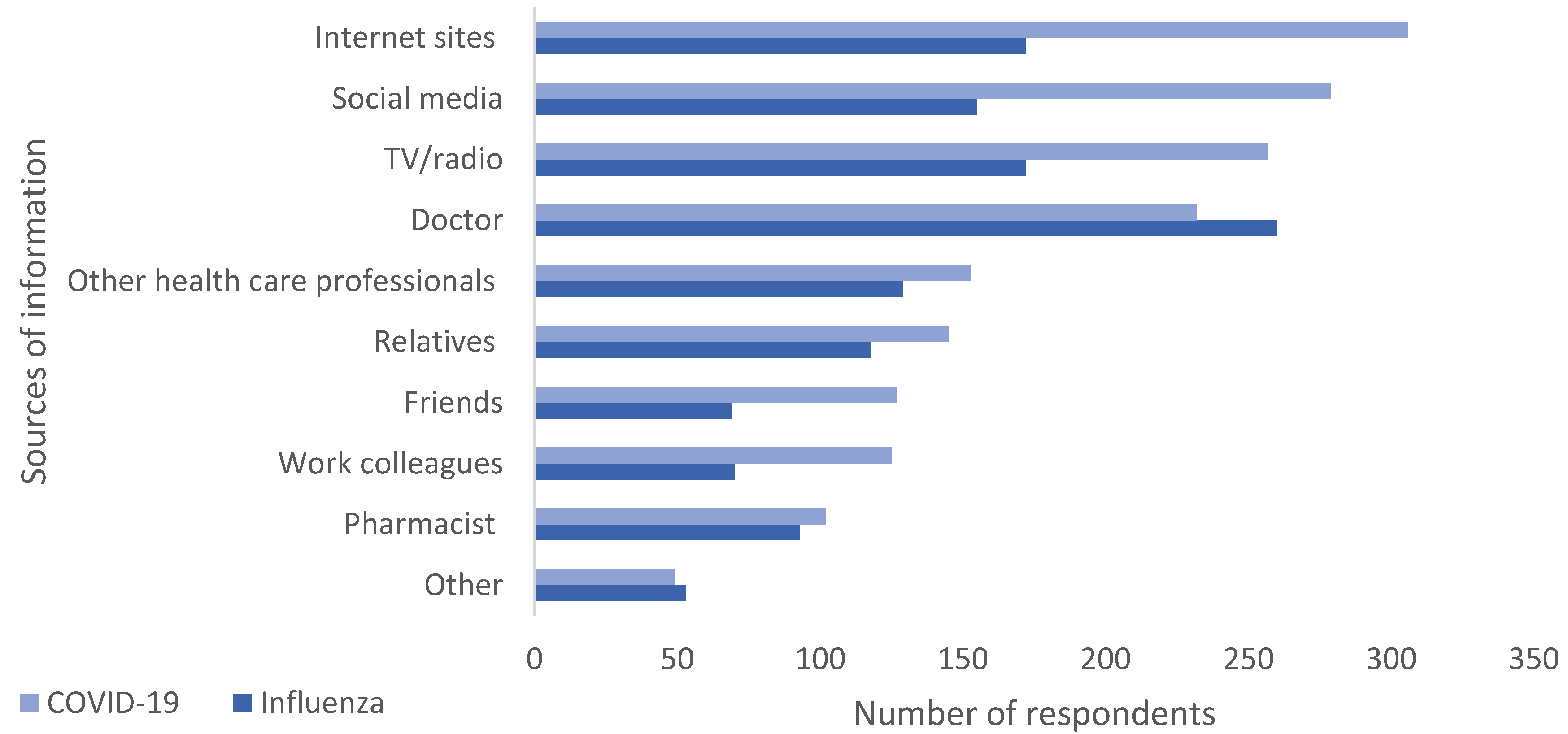

3.3. Participants’ Sources of Information About COVID-19 and SIV Vaccines

3.4. Participants’ Attitudes and Beliefs Toward COVID-19 and SIV Vaccines

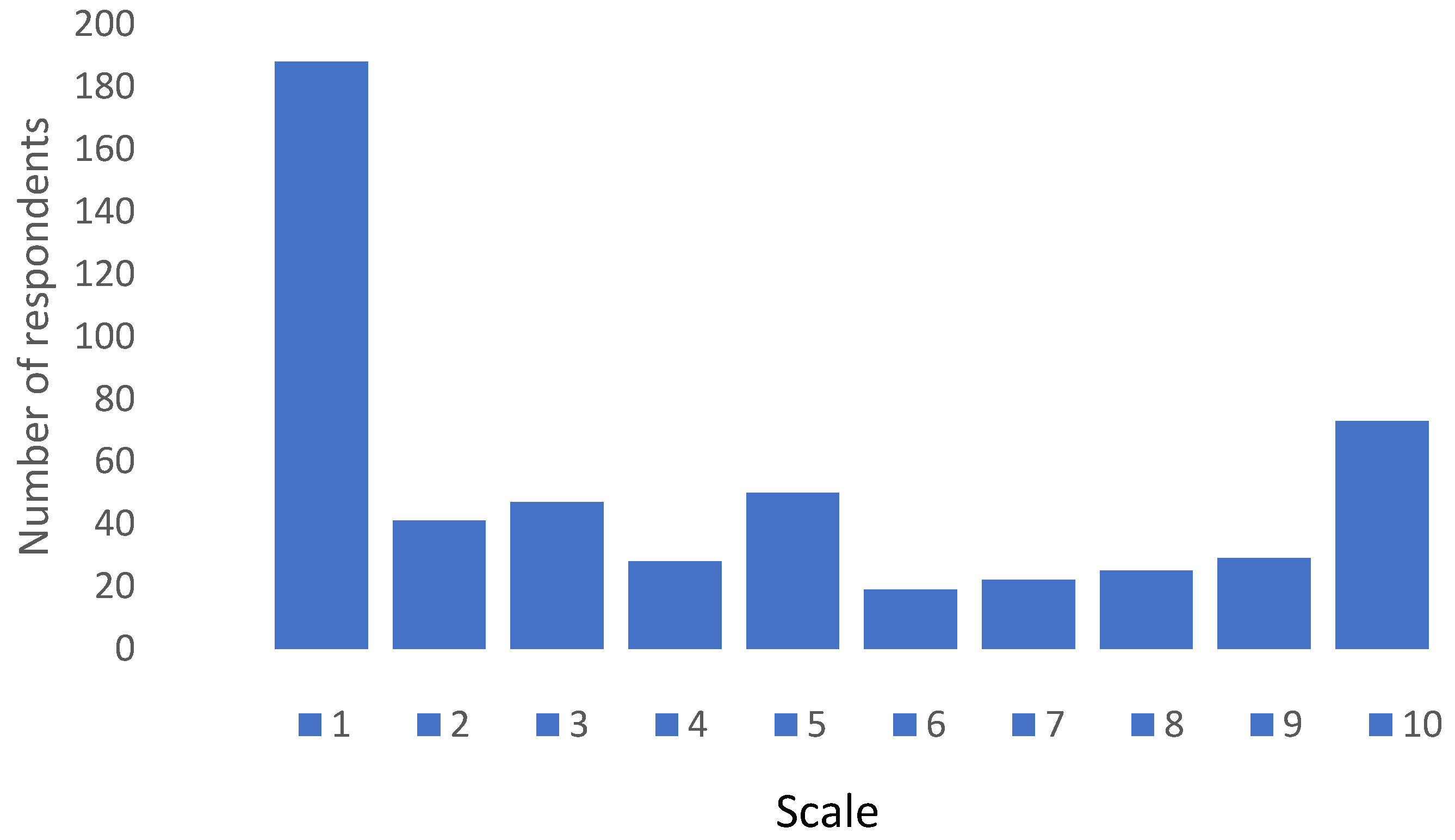

3.5. Willingness to Take a Combined COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccine

3.5.1. Positive Reactions: Confidence Rooted in Experience and Logic

3.5.2. Negative Reactions: Anchored in Fear, Experience, and Distrust

3.5.3. Mixed or Neutral Reactions: Caution and Conditional Acceptance

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. Available online: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/covid-19/vaccine-tracker.html#age-group-tab (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. WHO/Europe, EC and ECDC Urge Eligible Groups to Get Vaccinated or Boosted to Save Lives This Autumn and Winter. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/vulnerable-vaccinate-protecting-unprotected-covid-19-and-influenza (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Du, Z.; Fox, S.J.; Ingle, T.; Pignone, M.P.; Meyers, L.A. Projecting the Combined Health Care Burden of Seasonal Influenza and COVID-19 in the 2020–2021 Season. MDM Policy Pract. 2022, 7, 23814683221084631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meslé, M.M.I.; Brown, J.; Mook, P.; Katz, M.A.; Hagan, J.; Pastore, R. Estimated Number of Lives Directly Saved by COVID-19 Vaccination Programmes in the WHO European Region from December 2020 to March 2023: A Retrospective Surveillance Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fougerolles, T.R.; Baïssas, T.; Perquier, G.; Vitoux, O.; Crépey, P.; Bartelt-Hofer, J.; Bricout, H.; Petitjean, A. Public Health and Economic Benefits of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in Risk Groups in France, Italy, Spain, and the UK: State of Play and Perspectives. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Managing Seasonal Vaccination Policies and Coverage in the European Region. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/activities/managing-seasonal-vaccination-policies-and-coverage-in-the-european-region (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Kluge, H.P.; WHO Regional Office for Europe. No One Knows Your Risk Like You Do: Protect Yourself and Others This Respiratory Virus Season. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/09-10-2024-statement---no-one-knows-your-risk-like-you-do--protect-yourself-and-others-this-respiratory-virus-season (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Matthes, J.; Corbu, N.; Jin, S.; Theocharis, Y.; Schemer, C.; van Aelst, P.; Strömbäck, J.; Koc-Michalska, K.; Esser, F.; Aalberg, T.; et al. Perceived Prevalence of Misinformation Fuels Worries about COVID-19: A Cross-Country, Multi-Method Investigation. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022, 26, 3133–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogara, G.; Pierri, F.; Cresci, S.; Luceri, L.; Giordano, S. Misinformation and Polarization around COVID-19 Vaccines in France, Germany, and Italy. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Science Conference (WEBSCI ‘24), Stuttgart, Germany, 21–24 May 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. A Global Map of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Rates per Country: An Updated Concise Narrative Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerretsen, P.; Kim, J.; Caravaggio, F.; Quilty, L.; Sanches, M.; Wells, S.; Brown, E.E.; Agic, B.; Pollock, B.G.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; et al. Individual Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy, 2021. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshio, T.; Ping, R. Trust, Interaction with Neighbours, and Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Chinese Data. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, G.C.; Engel, E.; Koch, L.; Ranzinger, T.; Shahid, I.B.M.; Head, M.G.; Eitze, S.; Betsch, C. Determinants of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy among Pregnant Women in Europe: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021, 26, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, D.; Sahoo, P.; Larson, H.J.; Karafillakis, E. Factors Influencing Healthcare Professionals’ Confidence in Vaccination in Europe: A Literature Review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2041360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S.; Agius, S.; Souness, J.; Brincat, A.; Grech, V. The Fastest National COVID Vaccination in Europe—Malta’s Strategies. Health Sci. Rev. 2021, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Ji, L.; Bishwajit, G.; Guo, S. Uptake of COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccines in Relation to Preexisting Chronic Conditions in the European Countries. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Influenza Vaccine Coverage. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/influenza-vaccination-coverage?CODE=MLT&ANTIGEN=FLU_ELDERLY&YEAR= (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Survey Report on National Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Recommendations and Coverage Rates in EU/EEA Countries; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordina, M.; Lauri, M.A.; Lauri, J. Attitudes towards COVID-19 Vaccination, Vaccine Hesitancy and Intention to Take the Vaccine. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, M.; Cordina, M.; Lauri, M.A. Playing with Fire—Negative Perceptions towards COVID-19 Vaccination. Xjenza Online 2022, 11, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behaviour. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behaviour; Kuhn, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- National Office of Statistics Malta. National Summary Data Page. Available online: https://nso.gov.mt/special-data-dissemination/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Interim COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in the EU/EEA During the 2023–24 Season Campaigns; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Nardi, A. Vaccine Hesitancy in the Era of COVID-19. Public Health 2021, 194, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafadar, A.H.; Tekeli, G.G.; Jones, K.A.; Stephan, B.; Dening, T. Determinants for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the General Population: A Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Public Health 2022, 31, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Sood, N.; Noc Lam, C.; Unger, J.B. Demographic Characteristics Associated with Intentions to Receive the 2023−2024 COVID-19 Vaccine. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 66, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshkov, D. Explaining the Gender Gap in COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, J.; Lauri, M.A. Navigating the Maltese Landscape; Kite Group: Birkirkara, Malta, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bulusus, A.; Segarra, C.; Khayat, L. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among People with Underlying Chronic Conditions in 2022: A Cross-Sectional Study. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 22, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looi, M.K. The European Health Care Workforce Crisis: How Bad Is It? BMJ 2024, 384, q8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunç, A.M.; Çevirme, A. Attitudes of Healthcare Workers toward the COVID-19 Vaccine and Related Factors: A Systematic Review. Public Health Nurs. 2024, 41, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudouen, H.; Tattevin, P.; Thibault, V.; Ménard, G.; Paris, C.; Saade, A. Determinants of Influenza and COVID Vaccine Uptake in Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey during the Post-Pandemic Era in a Network of Academic Hospitals in France. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Schuh, H.B.; Forr, A.; Shaw, J.; Salmon, D.A. Changes in Vaccine Attitudes and Recommendations among US Healthcare Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2024, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintyne, K.I.; Reilly, C.; Carpenter, C.; McNally, S.; Kearney, J. Attitudes towards COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccination in Healthcare Workers. Ir. Med. J. 2024, 117, 992. [Google Scholar]

- Manby, L.; Dowrick, A.; Karia, A.; Maio, L.; Buck, C.; Singleton, G.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Uddin, I.; Vanderslott, S.; Martin, S.; et al. Healthcare Workers’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards the UK’s COVID-19 Vaccination Programme: A Rapid Qualitative Appraisal. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, T.; Efstathiou, N.; Bailey, C.; Guo, P. Cultural and Social Attitudes towards COVID-19 Vaccination and Factors Associated with Vaccine Acceptance in Adults across the Globe: A Systematic Review. Vaccine 2024, 42, 125993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Mistrust during Pandemic Decline: Findings from 2021 and 2023 Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Vaccines 2024, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. COVID-19 Vaccines Key Facts. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/covid-19-medicines/covid-19-vaccines-key-facts (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Bekir, I.; Doss, F. Status Quo Bias and Attitude towards Risk: An Experimental Investigation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 41, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, T.; Shiroma, K.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Xie, B.; Jia, C.; Verma, N.; Lee, M.K. Misinformation and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine 2023, 41, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Hu, S.; Zhou, X.; Song, S.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Z. The Prevalence, Features, Influencing Factors, and Solutions for COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation: Systematic Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 9, e40201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denniss, E.; Lindberg, R. Social Media and the Spread of Misinformation: Infectious and a Threat to Public Health. Health Promot. Int. 2025, 40, daaf023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, C.; Mosnier, A.; Gavazzi, G.; Combadière, B.; Crépey, P.; Gaillat, J.; Launay, O.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Coadministration of Seasonal Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 18, 2131166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.F.; Elshabrawy, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Abdel-Rahman, S.; Shiba, H.A.A.; Elrewany, E.; Ghazy, R.M. Combining COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines Together to Increase the Acceptance of Newly Developed Vaccines in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2286339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Took or Intended to Take COVID-19 Vaccine in Season 23–24 | Took or Intended to Take Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in Season 23–24 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 126 | 22.7 | 35 | 6.3 | 52 | 9.4 |

| Female | 427 | 76.9 | 81 | 14.6 | 128 | 23.0 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 16–19 | 49 | 8.8 | 10 | 1.8 | 18 | 3.2 |

| 20–29 | 87 | 15.7 | 11 | 2 | 21 | 3.8 |

| 30–39 | 90 | 16.2 | 16 | 2.9 | 21 | 3.8 |

| 40–49 | 118 | 21.3 | 18 | 3.2 | 27 | 4.9 |

| 50–59 | 127 | 22.9 | 30 | 5.4 | 45 | 8.1 |

| 60–69 | 51 | 9.2 | 18 | 3.2 | 24 | 4.3 |

| 70–79 | 26 | 4.7 | 8 | 1.4 | 18 | 3.2 |

| 80 and over | 7 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.1 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 117 | 21.1 | 26 | 4.7 | 38 | 6.8 |

| In a relationship/married | 422 | 76 | 74 | 13.3 | 116 | 21 |

| other | 16 | 2.9 | 15 | 2.7 | 23 | 4.1 |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Primary | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Secondary | 76 | 13.7 | 15 | 2.7 | 27 | 4.7 |

| Post-secondary | 110 | 19.8 | 21 | 3.8 | 41 | 7.4 |

| Tertiary/further education | 367 | 66.1 | 79 | 14.2 | 110 | 19.8 |

| Health care worker (HCW) | ||||||

| Yes | 121 | 21.8 | 22 | 4 | 45 | 8.1 |

| No | 432 | 77.7 | 95 | 17.1 | 134 | 24.14 |

| Chronic/long term condition | ||||||

| Yes | 126 | 22.7 | 40 | 7.2 | 55 | 10 |

| No | 427 | 77.0 | 77 | 13.9 | 125 | 22.5 |

| Taken COVID-19 vaccine this year | ||||||

| Yes | 90 | 18.2 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 447 | 80.5 | - | - | - | - |

| If ‘No’, do you intend to take it | ||||||

| Yes | 27 | 4.8 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 421 | 75.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Taken influenza vaccine this year | ||||||

| Yes | 144 | 25.9 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 399 | 71.9 | - | - | - | - |

| If ‘No’, do you intend to take it | ||||||

| Yes | 36 | 6.4 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 357 | 64.3 | - | - | - | - |

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe that the COVID-19 vaccine helps protect the health of the people who take it | 6.55 (2.90) | 1 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 |

| I believe that people should be encouraged to take the COVID-19 vaccine | 5.72 (3.13) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| The opinion of my family and friends is important in my decision to take the COVID-19 vaccine | 3.98 (2.88) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| I value the advice of health professionals regarding the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine | 7.09 (2.84) | 1 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

| It is easy for me to get the COVID-19 vaccine | 7.5 (2.7) | 1 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe that the seasonal influenza vaccine helps protect the health of the people who take it | 6.76 (2.81) | 1 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| I believe that people should be encouraged to take the seasonal influenza vaccine | 6.36 (2.99) | 1 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 |

| The opinion of my family and friends is important in my decision to take the seasonal influenza vaccine | 3.71 (2.83) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| I value the advice of health professionals regarding the effectiveness of the seasonal influenza vaccine | 7.08 (2.82) | 1 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| It is easy for me to get the seasonal influenza vaccine | 7.77 (2.68) | 1 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Positive reactions rooted in experience and logic | Convenience | ‘More convenient, less needles and only one sore spot on one arm’ (q1) ‘Available in health centres and stocked by pharmacies’ (q2) |

| Practicality | ‘I would recover from any side effects in one go’ (q3) ‘Saves time and money’ (q4) ‘Less time consuming. Only 1 recovery period instead of double’ (q5) ‘Makes sense logistically and public health-wise’ (q6) | |

| Efficacy | ‘Combined vaccines offer better immunity’ (q7) | |

| Negative reactions anchored in fear, experience and distrust | Health complications | ‘I am somewhat prone to allergies, so I would rather take the vaccines one at a time’ (q8) ‘I have to be fit/ healthy to take any vaccine, therefore, since one doesn’t know for sure, I won’t take it’ (q9) ‘Some studies seem to indicate that people who suffer with heart problems have seen their heart problem regress at a faster rate. So, I would never take a combo vaccine.’ (q10) Negative effects on pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes were also a concern. ‘One of my friends, was pregnant and her employer told her that her must take vaccine, her baby had problems, even her. I didn’t get any of vaccines and I had 2 days temperature of 38. And also I was pregnant then, but I refused be vaccinated.’ (q11) |

| Side effects | ‘I am not comfortable taking the COVID vaccine due to the negative effect the last booster dose had on me (sudden rapid fever and extreme shaking) I have however been taking the influenza vaccine for over 10 years and believe that it is more well researched.’ (q12) ‘I got Bigeminy and low blood count after the COVID vaccine, I will not take anymore. The flu vaccine works well with me, I take this annually.’ (q13) ‘From when I took the COVID vaccines, the 3 of them, I got extreme anxiety and weak legs at 28 years old sometimes I feel my heartbeat is going fast and I feel dizzy in an instance and weak and need sleep’ (q14) ‘COVID jab not interested I believe my chronic illness now is due to jabs I took’ (q15) ‘If I experience an adverse event I would like to know exactly which one caused it’ (q16) ‘Too many side effects and possible long-term complications’ (q17) ‘There have been significant adverse effects with both vaccines particularly the influenza vaccine hence a combination of the two might also induce severe adverse effects and furthermore their efficacy is short-lived and would likely require a booster shot a few months after’ (q18) | |

| Effectiveness | ‘Was bad when I took vaccine on 3rd time and in any case it was then I caught the COVID just the same’ (q19) ‘Each time I took the flu vaccine I was always terribly sick with the flu’ (q20) ‘The influenza vaccine—I have taken this occasionally in the past and have not found it to be effective and therefore have avoided taking it’ (q21) | |

| Skepticism/distrust | ‘mRNA vaccines are one big human experiment. We do not yet know the long-term effects. Much has been hidden. Some have died with the vaccine. Others have health problems. The literature shows that they had more side effects than benefits. It’s a money-making business and we can’t rely on the manufacturers to reveal all the effects. Re the influenza vaccine, many who take it report feeling ill after’ (q22) ‘I want to stop being a Guinea pig to pharmaceutical companies that are amplifying fear to help them make money’ (q23) ‘COVID vaccine I think was invented in a very short period of time and we do not know the consequences that it might have on our health’ (q24) ‘The COVID-19 vaccine was never safe and effective to begin with due to a lack of long-term studies on it. As a result, we are seeing an excessive death rate and terminal illnesses caused by the said vaccine’ (q25) ‘After the pandemic I lost trust in the health system as it was clear that all they wanted was to make money’ (q26) ‘Too much information I’ve felt overwhelmed, confused and finally sceptical on the matter of vaccine. I would not opt to get vaccinated anymore’ (q27) ‘Rushed approval at EU level very sceptical about it’s benefits and am afraid in long term will cause more harm than good in healthy individuals who took it. I categorically refuse to take any further doses of it.’ (q28) ‘I’m a little concerned about claims of such vaccines on any ‘reprogramming’ effect or interference with my DNA constitution’ (q29) ‘The realities coming out in scholarly papers regarding COVID-19 are deeply distressing’ (q30) | |

| Loss of Autonomy | ‘I want the flexibility to choose which one or both I need to take.’ (q31) ‘I want to always be able to decide whether I want to take the COVID vaccine or not’ (q32) | |

| Mixed or neutral reactions indicating caution and conditional acceptance | Need for more information | ‘Before it is tested properly, medically approved and licensed with the right amount of research, I would have my doubts about taking a combined vaccine’ (q33) ‘I would need more information on the vaccine’ (q34) ‘I have to educate myself about it. Not very keen on taking COVID 19 vaccine again’ (q35) ‘Would prefer to have more information about such a combination’ (q36) |

| Recommendations from trusted professionals | ‘If the vaccine will be safe with not much side effects, I would take it. It should be approved with doctors’ (q37) ‘I will take it if I am convinced by medics that it is safer to do so for my vulnerable family’ (q38) ‘I did not see much in the local media that assured me that the COVID vaccine is safer and (that) my “side effects” were not caused by the vaccine. One would believe that now that more time has passed, there is much more information available on the safety of the vaccine compared to before. Therefore, I would like to see more information backed by serious scientific studies carried out by reputable organizations that have been verified.’ (q39) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cordina, M.; Lauri, M.A.; Lauri, J. Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in the Post-COVID Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Malta. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040102

Cordina M, Lauri MA, Lauri J. Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in the Post-COVID Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Malta. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(4):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040102

Chicago/Turabian StyleCordina, Maria, Mary Anne Lauri, and Josef Lauri. 2025. "Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in the Post-COVID Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Malta" Pharmacy 13, no. 4: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040102

APA StyleCordina, M., Lauri, M. A., & Lauri, J. (2025). Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in the Post-COVID Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Malta. Pharmacy, 13(4), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040102