Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Appropriateness Among Heart Failure Patients Attending the Cardiac Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cardiovascular Diseases and Heart Failure

1.2. Medication Adherence and Importance

1.3. Medication Appropriateness

1.4. Assessing Medication Adherence and Appropriateness

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Sample Size

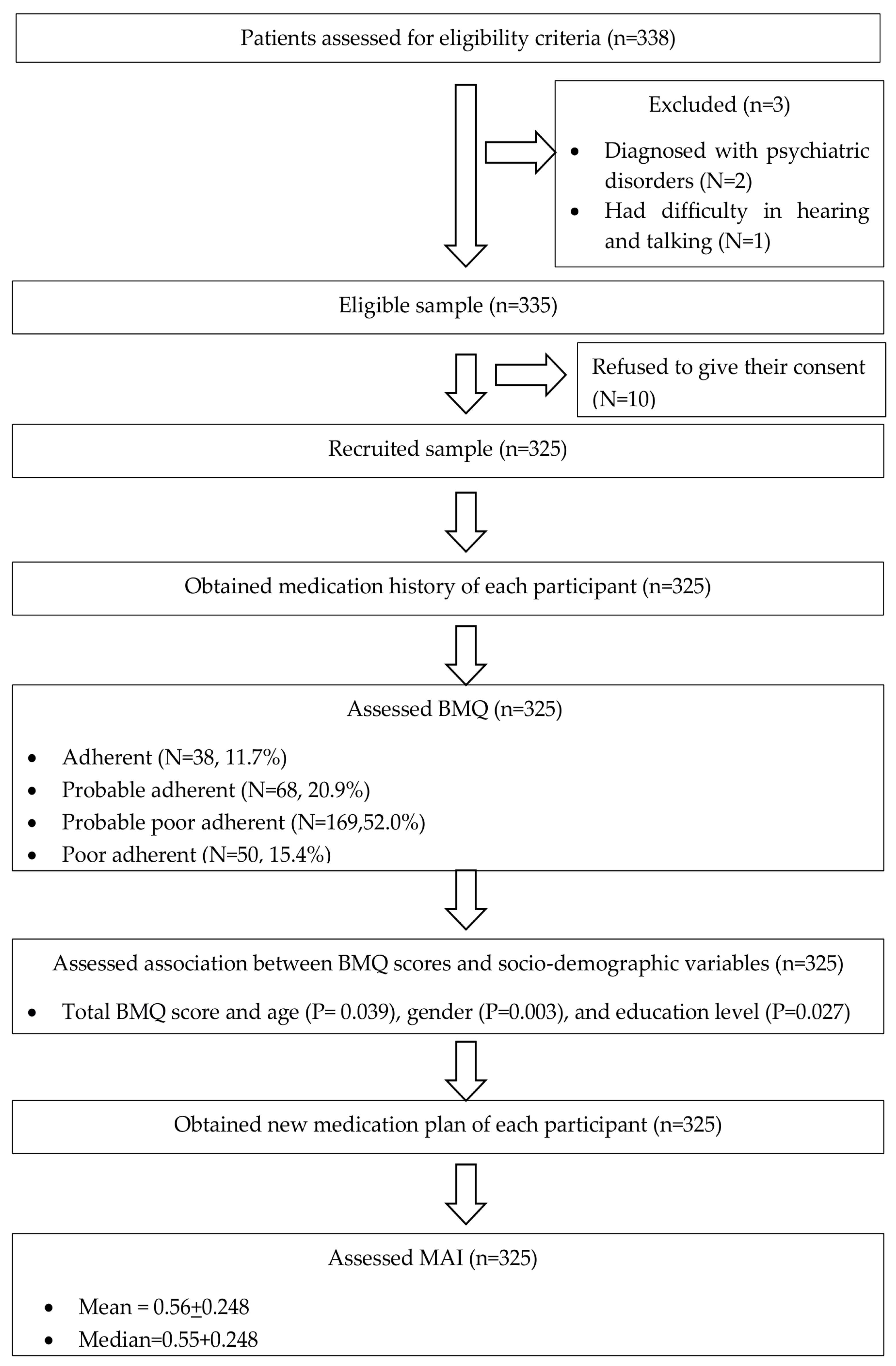

2.5. Recruitment of Participants

2.6. Study Tools

2.7. Study Procedure

2.8. Data Analysis

2.9. Outcomes of the Study

3. Results

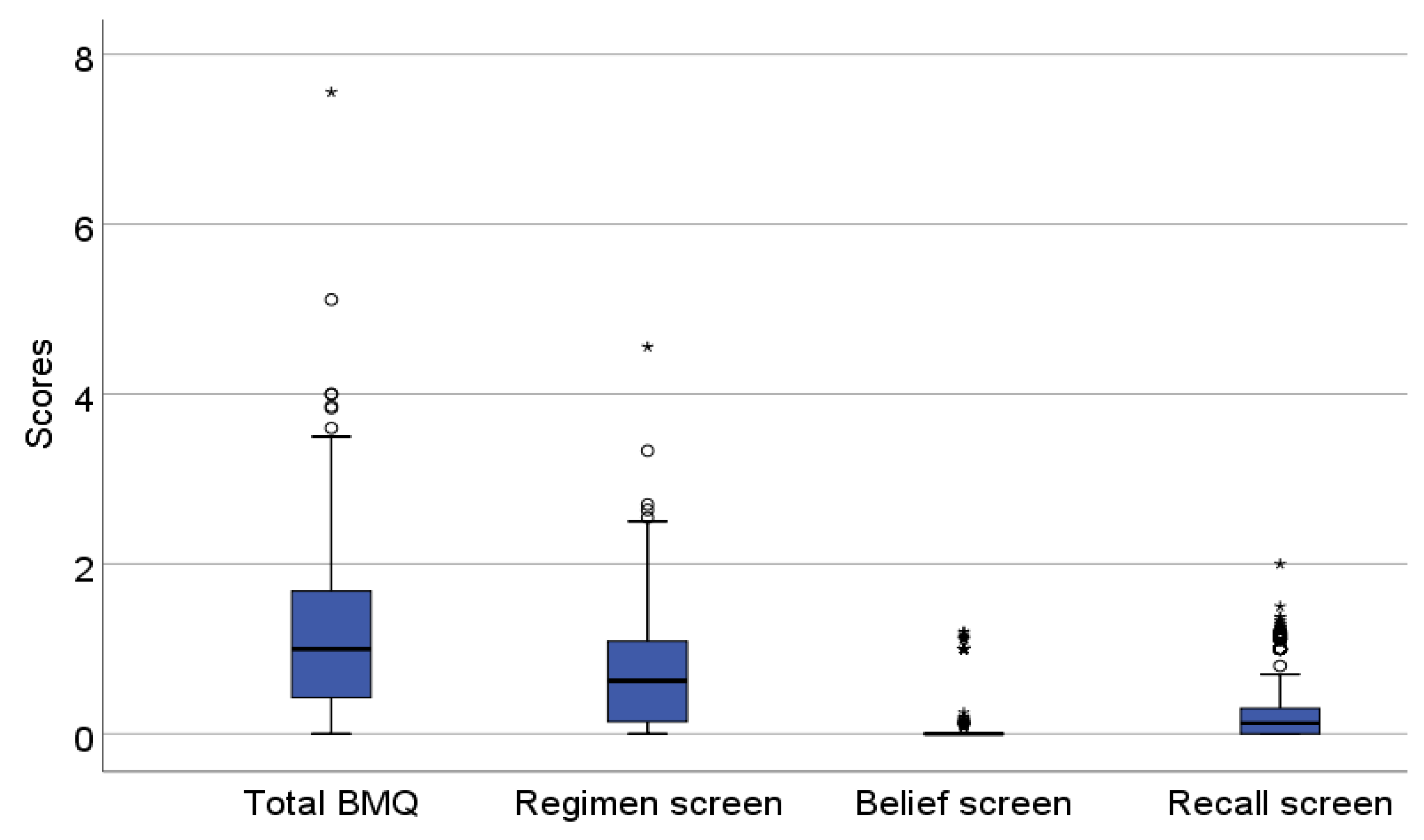

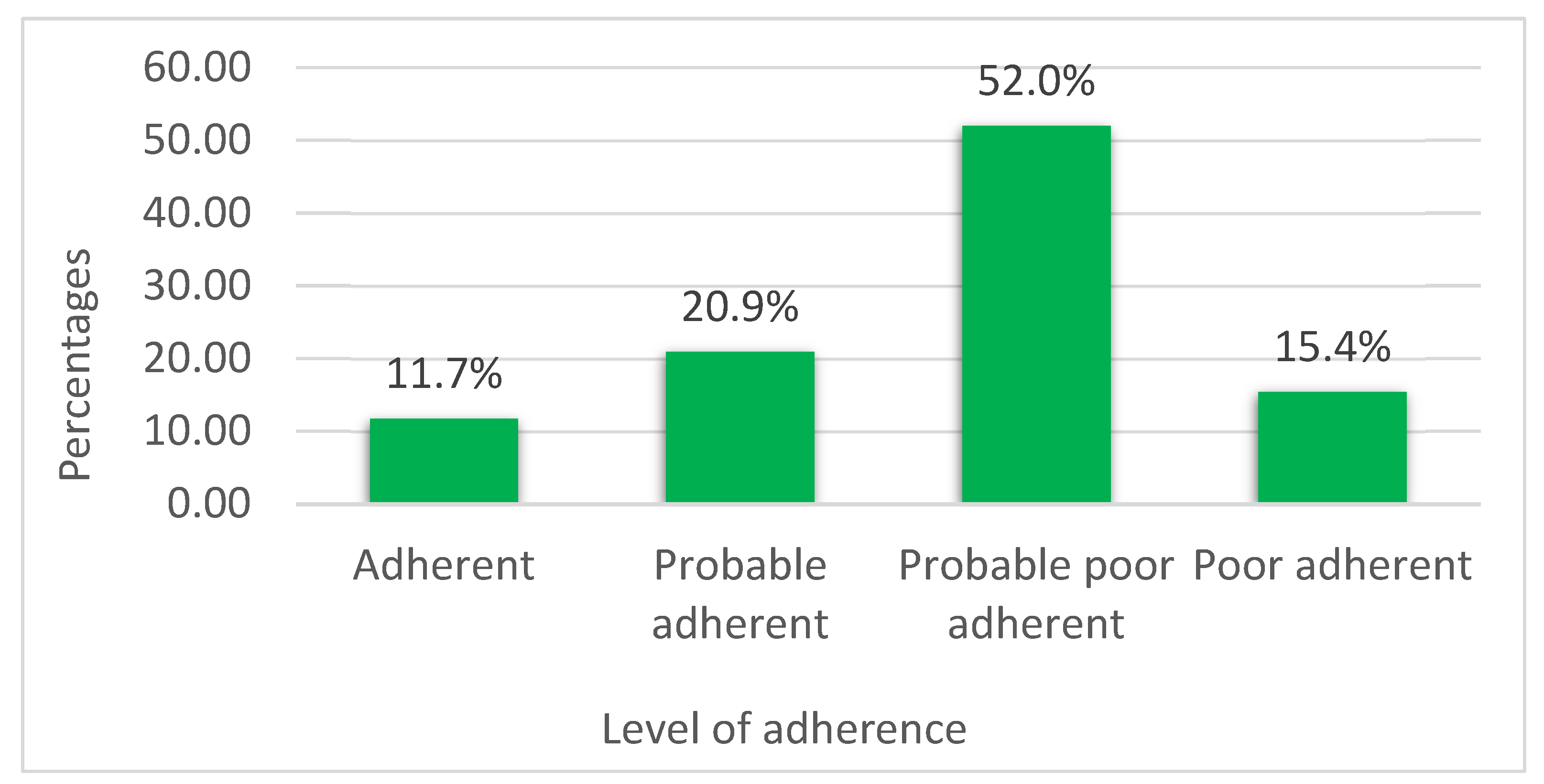

3.1. Baseline Medication Adherence Assessment

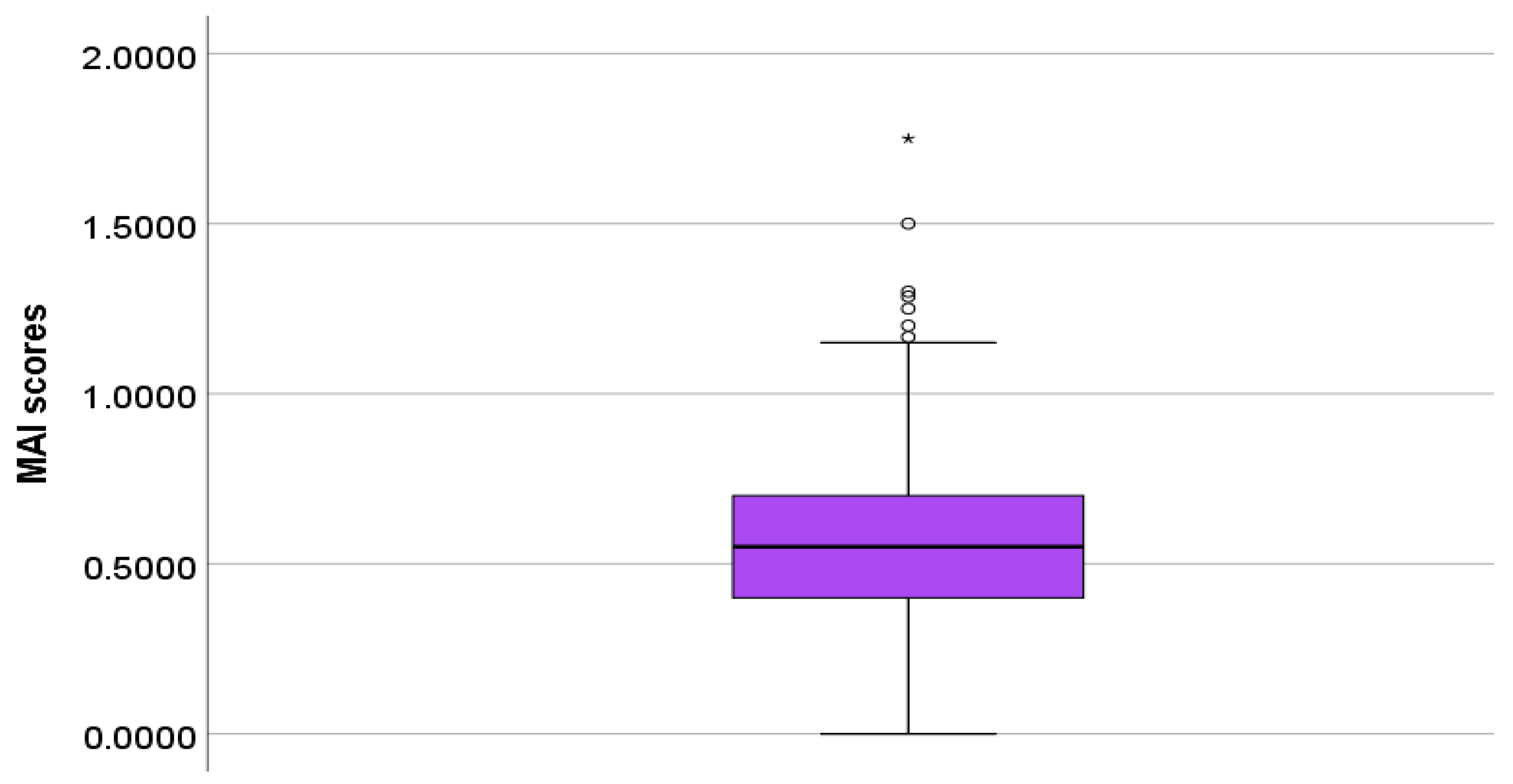

3.2. Outcomes of the Medication Appropriateness Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMH | Australian Medicines Handbook |

| BMQ | Brief Medication Questionnaire |

| BNF | British National Formulary |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| ECHO | Echocardiogram |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| MAI | Medication Appropriateness Index |

| NHK | National Hospital Kandy |

| PIM | Potentially Inappropriate Medicines |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Cardiovascular Disease. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cardiovascular-disease/ (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Akeroyd, J.M.; Chan, W.J.; Kamal, A.K.; Palaniappan, L.; Virani, S.S. Adherence to Cardiovascular Medications in the South Asian Population: A systematic review of current evidence and future directions. World J. Cardiol. 2015, 7, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavudeen, S.S.; Easwaran, V.; Khan, N.A.; Venkatesan, K.; Paulsamy, P.; Mohammed Hussein, A.T.; Imam, M.T.; Almalki, Z.S.; Akhtar, M.S. Cardiovascular Disease-Related Health Promotion and Prevention Services by Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia: How Well Are They Prepared? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardiovascular Disease. In A Nationwide Framework for Surveillance of Cardiovascular and Chronic Lung Diseases; NCBI Bookshelf; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83160/ (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Guan, J.; Xin, A.; Zhang, F.; Ouyang, W.; et al. Global Trends in Heart Failure from 1990 to 2019: An Age-period-cohort Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, E.; Engidawork, E.; Alebachew, M.; Mekonnen, D.; Berha, A.B. Evaluation of Drug Therapy Problems, Medication Adherence and Treatment Satisfaction among Heart Failure Patients on Follow-up at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of Heart Failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahim, B.; Kapelios, C.J.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card Fail Rev 2023, 9, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaté, E.; World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; ISBN 978-92-4-154599-0. [Google Scholar]

- De Geest, S.; Zullig, L.L.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Hughes, D.; Wilson, I.B.; Vrijens, B. Improving Medication Adherence Research Reporting: ESPACOMP Medication Adherence Reporting Guideline (EMERGE). Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. J. Work. Group Cardiovasc. Nurs. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2019, 18, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Non Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Kardas, P.; Bennett, B.; Borah, B.; Burnier, M.; Daly, C.; Hiligsmann, M.; Menditto, E.; Peterson, A.M.; Slejko, J.F.; Tóth, K.; et al. Medication Non-Adherence: Reflecting on Two Decades since WHO Adherence Report and Setting Goals for the Next Twenty Years. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1444012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimmy, B.; Jose, J. Patient Medication Adherence: Measures in Daily Practice. Oman Med. J. 2011, 26, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarekegn, G.Y.; Dagnew, F.N.; Moges, T.A.; Asmare, Z.A.; Tsega, S.S.; Damtie, D.G.; Anberbr, S.S.; Semman, M.F.; Bitew, B.E. Medication Non-Adherence and Its Predictors among Chronic Heart Failure Patients in Northwest Amhara Region. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amininasab, S.; Lolaty, H.; Moosazadeh, M.; Shafipour, V. Medication Adherence and Its Predictors among Patients with Heart Failure. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2018, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, M.; Khader, Y.; Alkouri, O.; Al-Bashaireh, A.; Alhalaiqa, F.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Qaladi, O.A.; Alharbi, A.; Alshahrani, Y.M.; Alqarni, A.S.; et al. Medication Adherence and Its Influencing Factors among Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross Sectional Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, M.A.; Toleha, H.N.; Sema, F.D. Medication Nonadherence and Associated Factors among Heart Failure Patients at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2023, 2023, 1824987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, D.M.; Elders, P.J.M.; Boons, C.C.L.M.; Nijpels, G.; Hugtenburg, J.G. Factors Associated With Nonadherence to Cardiovascular Medications. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almarwani, A.M.; Almarwani, B.M. Factors Predicting Medication Adherence among Coronary Artery Disease Patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2023, 44, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, A.; Yu, J.; Fu, R.; Duan, L.; An, F.; et al. Pharmacist-Led Management Model and Medication Adherence Among Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2453976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehoff, K.M.; Mecca, M.C.; Fried, T.R. Medication Appropriateness Criteria for Older Adults: A Narrative Review of Criteria and Supporting Studies. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2019, 10, 2042098618815431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobretti, M.R.; Robert, L.; Page, I.I.; Linnebur, S.A.; Deininger, K.M.; Ambardekar, A.V.; Lindenfeld, J.; Aquilante, C.L. Medication Regimen Complexity in Ambulatory Older Adults with Heart Failure. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.P.; Birtcher, K.K.; Beavers, C.J.; Baker, W.L.; Brouse, S.D.; Page, R.L.; Bittner, V.; Walsh, M.N. The Role of the Clinical Pharmacist in the Care of Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beezer, J.; Hatrushi, M.A.; Husband, A.; Kurdi, A.; Forsyth, P. Polypharmacy Definition and Prevalence in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 27, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelchu, T.; Abdela, J. Drug Therapy Problems among Patients with Cardiovascular Disease Admitted to the Medical Ward and Had a Follow-up at the Ambulatory Clinic of Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital: The Case of a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312119860401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adem, L.; Tegegne, G.T. Medication Appropriateness, Polypharmacy, and Drug-Drug Interactions in Ambulatory Elderly Patients with Cardiovascular Diseases at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppar, T.M.; Cooper, P.S.; Mehr, D.R.; Delgado, J.M.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M. Medication Adherence Interventions Improve Heart Failure Mortality and Readmission Rates: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 5, e002606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gathright, E.C.; Dolansky, M.A.; Gunstad, J.; Redle, J.D.; Josephson, R.; Moore, S.M.; Hughes, J.W. The Impact of Medication Non-Adherence on the Relationship Between Mortality Risk and Depression in Heart Failure. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2017, 36, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, J.; Abateka, T.; Kebede, O. Patients’ Adherence to Anti-diabetic Medications and Associated Factors in Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Inq. J. Med. Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58, 00469580211067477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Jayawardena, R.; Katulanda, P.; Constantine, G.R.; Ramanayake, V.; Galappatthy, P. Translation and Validation of the Sinhalese Version of the Brief Medication Questionnaire in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 7519462. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2018/7519462 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagyawantha, N.M.Y.; Coombes, I.D.; Gawarammana, I.; Mohamed, F. Impact of a Clinical Pharmacy Intervention on Medication Adherence and the Quality Use of Medicines in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Single Centre Nonrandomised Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2025, 18, 2468782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istilli, P.T.; Pereira, M.A.; Teixeira, C.R.; Zanetti, M.L.; Becker, T.C.; Marques, J.P. Treatment adherence to oral glucose-lowering agents in people with diabetes: Using the Brief Medication Questionnaire. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2015, 19, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Svarstad, B.L.; Chewning, B.A.; Sleath, B.L.; Claesson, C. The Brief Medication Questionnaire: A Tool for Screening Patient Adherence and Barriers to Adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 1999, 37, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, J.T.; Schmader, K.E. The Medication Appropriateness Index: A Clinimetric Measure. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukulska, A.; Garwacka-Czachor, E. Assessment of Adherence to Treatment Recommendations among Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanpour, F.; Rafiei, Z.; Ravanipour, M.; Motamed, N. Assessment of Medication Adherence in Elderly Patients With Cardiovascular Diseases Based on Demographic Factors in Bushehr City in the Year 2013. Jundishapur J. Chronic Dis. Care 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Vaezi, F.; Afzal, G.; Naderi, N.; Mehralian, G. Medication Adherence and Health Literacy in Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Iran. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2022, 6, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-R.; Lennie, T.A.; Chung, M.L.; Frazier, S.K.; Dekker, R.L.; Biddle, M.J.; Moser, D.K. Medication Adherence Mediates the Relationship between Marital Status and Cardiac Event-Free Survival in Patients with Heart Failure. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2012, 41, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.; Hanna, O. otentially Inappropriate Medication Use among Geriatric Patients in Primary Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the Beers, STOPP, FORTA and MAI Criteria. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency (N) and Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Below 45 | 10 (3.1) |

| 45–59 | 80 (24.6) | |

| 60–74 | 195 (60.0) | |

| 75 or above | 40 (12.3) | |

| Gender | Male | 241 (74.2) |

| Female | 84 (25.8) | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 13 (4.0) |

| Married | 272 (83.7) | |

| Widowed/divorced | 40 (12.3) | |

| Education level | No schooling | 10 (3.1) |

| Grades 1 to 11 | 251 77.2) | |

| Up to A/L, graduated or others | 64 (19.7) | |

| Current | Yes | 87 (26.8) |

| employment status | No | 238 (73.2) |

| Living arrangement | Alone | 18 (5.5) |

| With spouse | 69 (21.2) | |

| With spouse and children | 180 (55.4) | |

| Others | 58 (17.9) |

| Characteristics | Category | Mean Total BMQ Score |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Below 45 | 1.62 |

| 45–59 | 1.13 | |

| 60–74 | 1.09 | |

| 75 or above | 1.50 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.10 |

| Female | 1.34 | |

| Education level | No schooling | 1.87 |

| Grades 1 to 11 | 1.17 | |

| Up to A/L, graduated or others | 1.04 |

| Total BMQ Score (n = 325) | MAI Score (n = 325) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.16 | 0.56 |

| Median | 1.00 | 0.55 |

| Quartile (Q1) | 0.43 | 0.40 |

| Quartile (Q2) | 1.00 | 0.55 |

| Quartile (Q3) | 1.70 | 0.71 |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 1.27 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bagyawantha, N.M.Y.K.; Dangahage, I.N.; Mayurathan, G.; Suminda Pushpika, W.M. Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Appropriateness Among Heart Failure Patients Attending the Cardiac Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040101

Bagyawantha NMYK, Dangahage IN, Mayurathan G, Suminda Pushpika WM. Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Appropriateness Among Heart Failure Patients Attending the Cardiac Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleBagyawantha, Nanayakkara Muhandiramalaya Yasa Kalum, Isuri Nilnuwani Dangahage, Ghanamoorthy Mayurathan, and Weerasinghe Mudiyanselage Suminda Pushpika. 2025. "Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Appropriateness Among Heart Failure Patients Attending the Cardiac Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study" Pharmacy 13, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040101

APA StyleBagyawantha, N. M. Y. K., Dangahage, I. N., Mayurathan, G., & Suminda Pushpika, W. M. (2025). Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Appropriateness Among Heart Failure Patients Attending the Cardiac Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Pharmacy, 13(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13040101