Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Self-Medication Among Pharmacy Undergraduates in Penang, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Research Instrument

2.4. Ethical Consideration

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Reliability and Validity of the Study Instrument

3.3. Knowledge of Self-Medication

Factors Associated with Participants’ Knowledge of Self-Medication

3.4. Attitudes Toward Self-Medication

Factors Associated with Participants’ Attitudes Toward Self-Medication

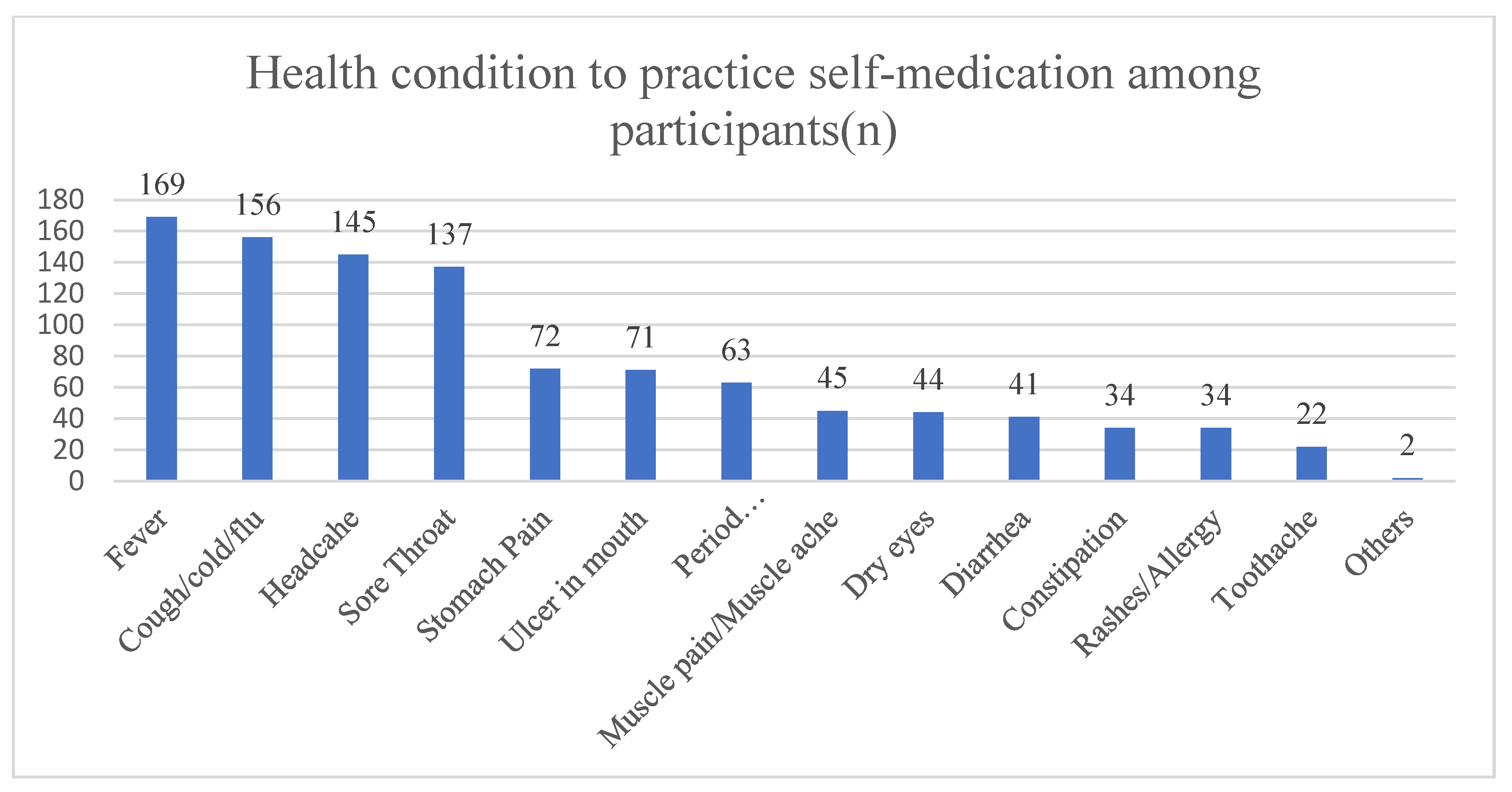

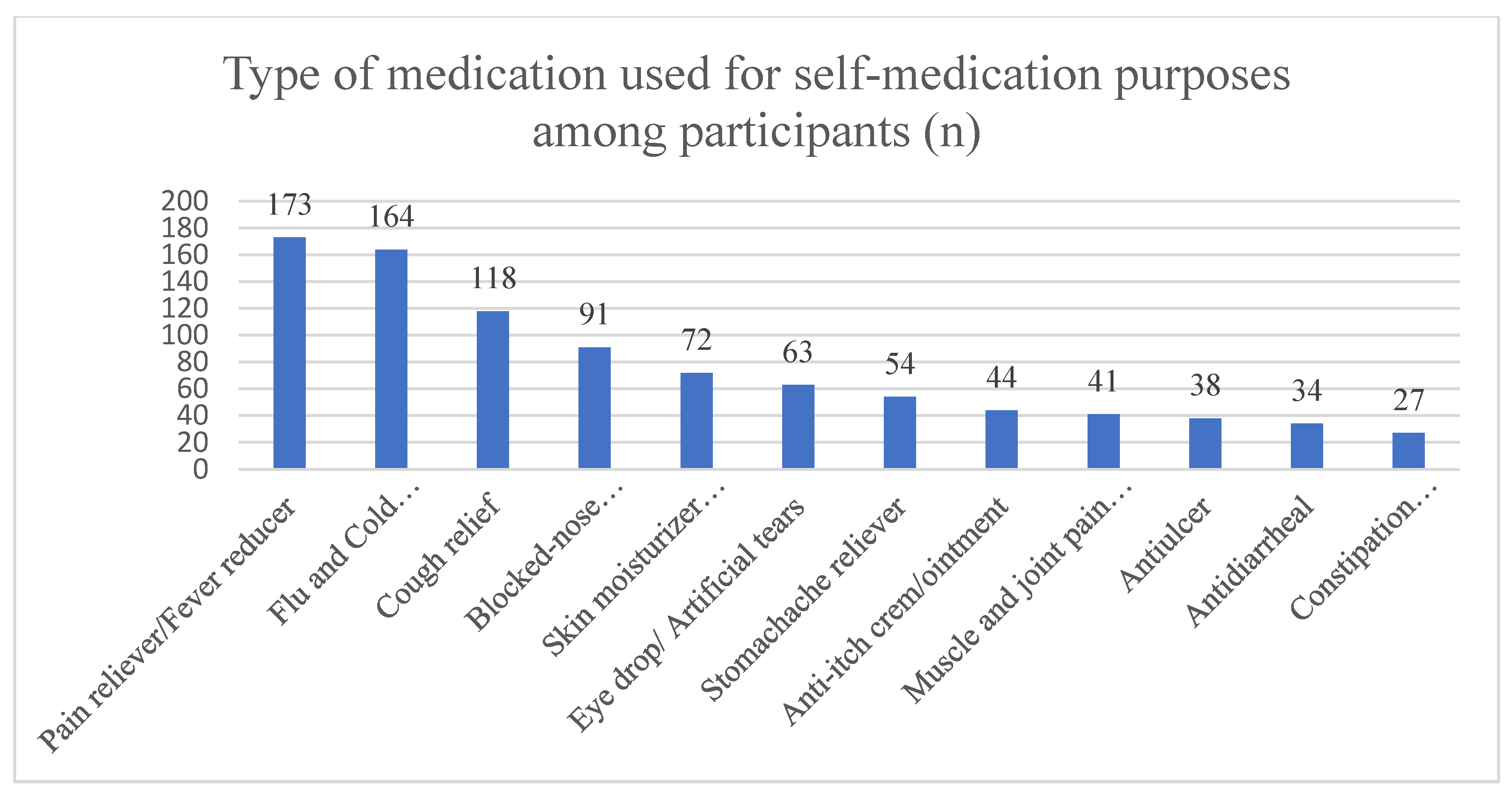

3.5. Practice of Self-Medication

Factors Associated with Participants’ Practices of Self-Medication

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge of Self-Medication

4.2. Attitudes Toward Self-Medication

4.3. Practice of Self-Medication

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Role of the Pharmacist in Self-Care and Self-Medication: Report of the 4th WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist, The Hague, The Netherlands, 26–28 August 1998; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/65860 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Auta, A.; Banwat, S.; Sariem, C.; Shalkur, D.; Nasara, B.; Atuluku, M. Medicines in Pharmacy Students’ Residence and Self-medication Practices. J. Young Pharm. 2012, 4, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Regulatory Assessment of Medicinal Products for Use in Self-Medication; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemyani, S.; Roohravan Benis, M.; Hosseinifard, H.; Jahangiri, R.; Aryankhesal, A.; Shabaninejad, H.; Rafiei, S.; Ghashghaee, A. Global, WHO Regional, and Continental Prevalence of Self-medication from 2000 to 2018: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Public Health 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Khan, S.A.; Ali, S.; Karim, S.; Baseer, A.; Chohan, O.; Hassan, S.M.F.; Khan, K.M.; Murtaza, G. Evaluation of self-medication amongst university students in Abbottabad, Pakistan; prevalence, attitude and causes. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2013, 70, 919–922. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N.K.; Alamoudi, B.M.; Baamer, W.O.; Al-Raddadi, R.M. Self-medication with analgesics among medical students and interns in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stosic, R.; Dunagan, F.; Palmer, H.; Fowler, T.; Adams, I. Responsible self-medication: Perceived risks and benefits of over-the-counter analgesic use. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocan, M.; Obuku, E.A.; Bwanga, F.; Akena, D.; Richard, S.; Ogwal-Okeng, J.; Obua, C. Household antimicrobial self-medication: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the burden, risk factors and outcomes in developing countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M.B. Self-medication practice in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennadi, D. Self-medication: A current challenge. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2013, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawaskar, M.D.; Balkrishnan, R. Switching from prescription to over-the counter medications: A consumer and managed care perspective. Manag. Care Interface 2007, 20, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M. Risks of Self-Medication Practices. Curr. Drug. Saf. 2010, 5, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopf, H.; Grams, D. Medication use of adults in Germany: Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2013, 56, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, L.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Angelillo, I.F. Self-medication practices among parents in Italy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 580650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Parimalakrishnan, S.; Patel, I.; Balkrishnan, R.; Nagar, A. Evaluation of Self-Medication Antibiotics Use Pattern Among Patients Attending Community Pharmacies in Rural India, Uttar Pradesh. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 5, 765–768. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:77570644 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Gyawali, S.; Shankar, P.R.; Poudel, P.P.; Saha, A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication Among Basic Science Undergraduate Medical Students in a Medical School in Western Nepal. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, FC17–FC22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatatbeh, M.J.; Alefan, Q.; Alqudah, M.A.Y. High prevalence of self-medication practices among medical and pharmacy students: A study from Jordan. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 54, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamea, R.; Bossei, A.; Al Zhrani, H. Knowledge: Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication among Undergraduate Medical Students in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. World Fam. Med. J./Middle East. J. Fam. Med. 2020, 18, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kubaisi, K.A.; Hassanein, M.M.; Abduelkarem, A.R. Prevalence and associated risk factors of self-medication with over-the-counter medicines among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 20, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Elkalmi, R.; Elnaem, M.H.; Rayes, I.K.; Alkodmani, R.M.; Elsayed, T.M.; Jamshed, S.Q. Perceptions, Knowledge and Practice of Self-Medication among Undergraduate Pharmacy Students in Malaysia: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Pharm. Pract. Community Med. 2018, 4, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.S.; Mathew, M.; Nazi, M.A.b.M.; Ahmad, N.A.B.; Rosni, A.H.B.M.; Chikkala, S.M. Self-Medication: Its Perception and Practice Among Health Science Students in a Malaysian University College. Acta Sci. Dent. Sci. 2023, 7, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, R.M.; Abou-ElWafa, H.S. Self-Medication in University Students from the City of Mansoura, Egypt. J. Environ. Public. Health 2017, 2017, 9145193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susheela, F.; Goruntla, N.; Bhupalam, P.K.; Veerabhadrappa, K.V.; Sahithi, B.; Ishrar, S.M.G. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward responsible self-medication among students of pharmacy colleges located in Anantapur district, Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas Petrović, A.; Pavlović, N.; Stilinović, N.; Lalović, N.; Paut Kusturica, M.; Dugandžija, T.; Zaklan, D.; Horvat, O. Self-Medication Perceptions and Practice of Medical and Pharmacy Students in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmin, F.; Asghar, M.S.; Naeem, U.; Najeeb, H.; Nauman, H.; Ahsan, M.N.; Khattak, A.K. Self-Medication Practices in Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 803937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albusalih, F.A.; Naqvi, A.A.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, N. Prevalence of Self-Medication among Students of Pharmacy and Medicine Colleges of a Public Sector University in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy 2017, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannasaheb, B.A.; Al-Yamani, M.J.; Alajlan, S.A.; Alqahtani, L.M.; Alsuhimi, S.E.; Almuzaini, R.I.; Albaqawi, A.F.; Alshareef, Z.M. Knowledge, Attitude, Practices and Viewpoints of Undergraduate University Students towards Self-Medication: An Institution-Based Study in Riyadh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduraibi, R.K.; Altowayan, W.M. A cross-sectional survey: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of self-medication in medical and pharmacy students. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Fattah, N.; Abdul Jalil, A.A.; Hadi, N.S.H. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication among Undergraduate Pharmacy Students in University Royal College of Medicine Perak. Asian J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 5, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Charan, J.; Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, F.; Alobaida, A.; Alshammari, A.; Alharbi, A.; Alrashidi, A.; Almansour, A.; Alremal, A.; Khan, K.U. University Students’ Self-Medication Practices and Pharmacists’ Role: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Hail, Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 779107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kanchan, T.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Rekha, T.; Mithra, P.; Kulkarni, V.; Papanna, M.K.; Holla, R.; Uppal, S. Perceptions and practices of self-medication among medical students in coastal South India. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misli, S.B.M.; Ahmad, A.; Yusof, P.; Masri, A.M.; Halimaton, T.; Kunjukunju, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Undergraduate Nursing Students regarding Self-Medication. Int. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.A.; Schattner, P.; Mazza, D. Doing A Pilot Study: Why is It Essential? Malays. Fam. Physician Off. J. Acad. Fam. Physicians Malaysia 2006, 1, 70. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4453116/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.F.; Precioso, J.; Becoña, E. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of self-medication among university students in Portugal: A cross-sectional study. Nordisk Alkohol. Nark. 2021, 38, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.K.; Imtiaz, A.; A Al Ibrahim, Y.; Bulbanat, M.B.; Al Mutairi, M.F.; Al Musaileem, S.F. Factors influencing knowledge and practice of self-medication among college students of health and non-health professions. IMC J. Med. Sci. 2019, 12, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmacharya, A.; Uprety, B.N.; Pathiyil, R.S.; Gyawali, S. Knowledge and Practice of Self-medication among Undergraduate Medical Students. J. Lumbini Med. Coll. 2018, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hashemzaei, M.; Afshari, M.; Koohkan, Z.; Bazi, A.; Rezaee, R.; Tabrizian, K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of pharmacy and medical students regarding self-medication, a study in Zabol University of Medical Sciences; Sistan and Baluchestan province in south-east of Iran. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, H.A.; Almahdi, J.S.; Alsalameen, N.A.; Alomar, F.A.; Islam, M.A. Assessment of self-medication practice and the potential to use a mobile app to ensure safe and effective self-medication among the public in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.; Handu, S.S.; Al Khaja, K.A.J.; Otoom, S.; Sequeira, R.P. Evaluation of the Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication among First-Year Medical Students. Med. Princ. Pract. 2006, 15, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, P.; Pandya, I. Prevalence and patterns of self-medication for skin diseases among medical undergraduate students. Int. J. Res. Dermatol. 2018, 4, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyishimire, J.; Okoya, F.; Adebayo, A.Y.; Humura, F.; Lucero-Prisno Iii, D.E. Assessment of self-medication practices with antibiotics among undergraduate university students in Rwanda. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics (N) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19–21 | 149 (73.4) |

| 22–25 | 54 (26.6) | |

| Sex | Male | 46 (22.7) |

| Female | 157 (77.3) | |

| Academic year | Year 1 | 50 (24.6) |

| Year 2 | 57 (28.1) | |

| Year 3 | 52 (25.6) | |

| Year 4 | 44 (21.7) | |

| Marital status | Single | 203 (100.0) |

| Ethnicity | Malay | 102 (50.2) |

| Chinese | 84 (41.4) | |

| Indian | 9 (4.4) | |

| Other | 8 (4.0) | |

| Study status | Full-time student | 203 (100.0) |

| Current residency | University housing | 150 (73.9) |

| Private housing | 42 (20.7) | |

| With family | 11 (5.4) | |

| Family members working in the healthcare sector | Yes | 64 (31.5) |

| No | 139 (68.5) | |

| Questions | Answered Correctly, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you know that some medications cannot be taken with other medications? | 198 (97.5) |

| Do you know that some medications cannot be taken with alcoholic drinks? | 198 (97.5) |

| Do you know that some medications cannot be taken with certain foods? | 194 (95.6) |

| Do you know that some medications are contraindicated or cannot be given to children? | 198 (97.5) |

| Do you know that some medications are contraindicated or cannot be given when pregnant? | 199 (98.0) |

| Do you know that some medications are contraindicated or cannot be given when breastfeeding? | 198 (97.5) |

| Do you know that some medications are contraindicated or cannot be given to people with chronic illnesses? | 195 (96.1) |

| Did you stop taking your medications without consulting with a healthcare professional for confirmation or guidance? | 105 (51.7) |

| Do you know that certain medications cannot be shared with family members, friends, neighbours, etc.? | 179 (88.2) |

| Do you check the expiry date of the medications before purchasing/before use? | 189 (93.1) |

| Knowledge score, median (IQR) | 9.0 (1.0) |

| Factors | Knowledge Level of Self-Medication | Chi-Square (x2) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good, n (%) | Moderate, n (%) | Poor, n (%) | ||||

| Age | 19–21 | 142 (95.3) | 5 (3.4) | 2 (1.34) | 0.4 | 0.828 |

| 22–25 | 52 (96.3) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | |||

| Sex | Male | 43 (93.5) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0.6 | 0.736 |

| Female | 151 (96.2) | 4 (2.5) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| Academic year | Year 1 | 46 (92.0) | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) | 6.7 | 0.345 |

| Year 2 | 53 (93.0) | 3 (5.3) | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Year 3 | 52 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Year 4 | 43 (97.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | |||

| Ethnicity | Malay | 97 (95.1) | 3 (2.9) | 2 (2.0) | 3.4 | 0.762 |

| Chinese | 81 (96.4) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Indian | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Other | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Current residency | University housing | 143 (95.3) | 6 (4.0) | 1 (0.7) | 7.4 | 0.117 |

| With family | 10 (90.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | |||

| Private housing | 41 (97.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |||

| Family members working in the healthcare sector | Yes | 60 (93.75) | 3 (4.7) | 1 (1.6) | 1.0 | 0.611 |

| No | 134 (96.4) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) | |||

| Statements | Strongly Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe self-medication is a part of self-care. | 83 (40.9) | 73 (36.0) | 32 (15.8) | 12 (5.9) | 3 (1.5) |

| I would like to start/continue my self-medication therapy. | 41 (20.2) | 70 (34.5) | 59 (29.1) | 22 (10.8) | 11 (5.4) |

| I will advise or recommend self-medication to others. | 34 (16.7) | 57 (28.1) | 58 (28.6) | 34 (16.7) | 20 (9.9) |

| I have confidence in my ability to manage my illness. | 29 (14.3) | 55 (27.1) | 69 (34.0) | 35 (17.2) | 15 (7.4) |

| I believe that I can diagnose my health condition. | 9 (4.4) | 24 (11.8) | 58 (28.6) | 64 (31.5) | 48 (23.6) |

| I believe that there is no training needed to start self-medication practice. | 7 (3.4) | 18 (8.9) | 27 (13.3) | 68 (33.5) | 83 (40.9) |

| I believe that easy access to healthcare information and facilities is the main cause of self-medication practice. | 42 (20.7) | 96 (47.3) | 44 (21.7) | 12 (5.9) | 9 (4.4) |

| The availability of OTC medicines and the belief in its safety leads me to practice self-medication | 38 (18.7) | 92 (45.3) | 56 (27.6) | 11 (5.4) | 6 (3.0) |

| I can diagnose different diseases because I am a pharmacy student | 14 (6.9) | 44 (21.7) | 66 (32.5) | 39 (19.2) | 40 (19.7) |

| I can treat different diseases because I am a pharmacy student. | 14 (6.9) | 35 (17.2) | 62 (30.5) | 44 (21.7) | 48 (23.6) |

| Attitude score, median (IQR) | 31.0 (7.1) | ||||

| Factors | Attitude Toward Self-Medication | Chi-Square (x2) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Negative, n (%) | ||||

| Age | 19–21 | 47 (31.5) | 100 (67.1) | 2 (1.3) | 1.4 | 0.492 |

| 22–25 | 14 (25.9) | 40 (74.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.2 | 0.563 | |

| Sex | Male | 16 (34.8) | 30 (65.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Female | 45 (28.7) | 110 (70.1) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| Academic year | Year 1 | 15 (30.0) | 35 (70.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3.9 | 0.696 |

| Year 2 | 21 (36.8) | 35 (61.4) | 1 (1.8) | |||

| Year 3 | 13 (25.0) | 38 (73.1) | 1 (1.9) | |||

| Year 4 | 12 (27.3) | 32 (72.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Ethnicity | Malay | 33 (32.4) | 69 (67.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3.5 | 0.745 |

| Chinese | 24 (28.6) | 58 (69.0) | 2 (2.4) | |||

| Indian | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Other | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Current residency | University housing | 43 (28.7) | 106 (70.7) | 1 (0.7) | 8.8 | 0.069 |

| With family | 3 (27.3) | 7 (63.6) | 1 (9.1) | |||

| Private housing | 15 (35.7) | 27 (64.3) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Family members working in the healthcare sector | No | 24 (37.5) | 40 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3.2 | 0.200 |

| Yes | 37 (26.6) | 100 (71.9) | 2 (1.4) | |||

| Question | Answer Options | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Within the last six [6] months, have you engaged in the practice of self-medication as defined in this survey? | Yes | 133 (65.5) |

| No | 70 (34.5) | |

| You answered “NO” for this question. What was your reason? * | Fear of using the wrong medication | 38 (18.7) |

| Fear of adverse effects of the medication | 31 (15.3) | |

| Lack of knowledge and experience | 39 (19.2) | |

| Lack of confidence to self-medicate | 31 (15.3) | |

| Had a bad experience with past self-medication practice | 3 (1.5) | |

| I had no illness in the specified time | 41 (20.2) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| You answered “YES” for this question. How often do you practice self-medication? | During the last month | 53 (26.1) |

| During the last three [3] months | 47 (23.2) | |

| During the last six [6] months | 33 (16.3) | |

| What was your source of information about the medications? * | Healthcare professionals | 100 (49.3) |

| Experience from previous treatment | 105 (51.7) | |

| Drug Reference Books (MIMS, BNF, Lexicomp, etc.) | 53 (26.1) | |

| Friend/Relatives/Neighbours | 50 (24.6) | |

| Internet | 60 (30.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | |

| Where do you get the medications for self-medication? * | Retail community pharmacy | 132 (65.0) |

| Leftover from previous treatment | 60 (30.0) | |

| From family members/friends/neighbours | 48 (23.7) | |

| Supermarket | 16 (7.9) | |

| Internet/online store | 15 (7.4) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| How do you request the medications if the source of the medications is a retail community pharmacy? * | By mentioning the names of the medications | 167 (82.3) |

| By mentioning the signs and symptoms of illness | 157 (77.4) | |

| By showing the medication container | 79 (38.9) | |

| By showing a piece of paper on which, the names of the medications are written | 44 (21.7) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| Why do you practice/prefer self-medication? * | Time constraint | 106 (52.2) |

| Minor illness treatment | 154 (75.9) | |

| Lack of confidence/trust in available healthcare services | 10 (4.9) | |

| Emergency case | 66 (32.5) | |

| Self-medication is cheaper | 71 (35.0) | |

| I used the medication before | 127 (62.6) | |

| I want to have experience with the medication/self-learning opportunity | 23 (11.3) | |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Factors | Practicing Self-Medication Within the Last Six Months (n, %) | Do not Practice Self-Medication Within the Last Six Months (n, %) | Chi-Square (x2) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 29 (63.0) | 17 (37.0) | 0.16 | 0.688 |

| Female | 104 (66.2) | 53 (33.8) | |||

| Age | 19–21 | 91 (61.6) | 58 (38.9) | 4.9 | 0.027 * |

| 22–25 | 42 (77.8) | 12 (22.2) | |||

| Academic year | Year 1 | 22 (44.0) | 28 (56.0) | 15.8 | 0.001 * |

| Year 2 | 42 (73.7) | 15 (26.3) | |||

| Year 3 | 34 (65.4) | 18 (34.6) | |||

| Year 4 | 35 (79.5) | 9 (20.5) | |||

| Ethnicity | Malay | 70 (68.6) | 32 (31.4) | 1.0 | 0.811 |

| Chinese | 52 (61.9) | 32 (38.1) | |||

| Indian | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | |||

| Other | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |||

| Residency | University housing | 93 (62.0) | 57 (38.0) | 3.2 | 0.203 |

| With family | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |||

| Private housing | 32 (76.2) | 10 (23.8) | |||

| Family members working in the healthcare sector | Yes | 47 (73.4) | 17 (26.6) | 2.6 | 0.107 |

| No | 86 (61.9) | 53 (38.1) | |||

| Variable | Multiple Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| β | OR a (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age | |||

| 19–21 | Reference | ||

| 22–25 | 0.278 | 1.321 (0.400–4.359) | 0.648 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | −0.199 | 0.820 (0.396–1.698) | 0.593 |

| Academic Year | |||

| Year 1 | Reference | ||

| Year 2 | 1.249 | 3.487 (1.543–7.879) | 0.003 |

| Year 3 | 0.817 | 2.263 (0.987–5.190) | 0.054 |

| Year 4 | 1.355 | 3.878 (0.929–16.191) | 0.063 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ababneh, B.F.; Aljamal, H.Z.; Hussain, R. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Self-Medication Among Pharmacy Undergraduates in Penang, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030079

Ababneh BF, Aljamal HZ, Hussain R. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Self-Medication Among Pharmacy Undergraduates in Penang, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(3):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030079

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbabneh, Bayan F., Hisham Z. Aljamal, and Rabia Hussain. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Self-Medication Among Pharmacy Undergraduates in Penang, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Pharmacy 13, no. 3: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030079

APA StyleAbabneh, B. F., Aljamal, H. Z., & Hussain, R. (2025). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Self-Medication Among Pharmacy Undergraduates in Penang, Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharmacy, 13(3), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030079