Abstract

Background: Patient adherence to antibiotics is vital to ensure treatment efficiency. Objective: To evaluate the impact of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics. Methods: A systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for systematic review (PRISMA) checklist and flow diagram. Controlled trials were included. Databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, SciELO, and Google Scholar. Quality, risk of bias, and confidence in cumulative evidence were evaluated. Results: Twenty-one trials were selected, with better patient adherence for the intervention than the control group. However, statistically significant differences were only found in two-thirds of these trials. The use of educational leaflets, personalized delivery of antibiotics, follow-up measures, and structured counseling were among the most impactful and significant interventions. The fact that community and/or hospital pharmacists were required to intervene in both groups (e.g., intervention vs. control/usual care) may explain that statistically significant differences were not achieved in all trials. Moderate quality issues and/or risk of bias were detected in some of the evaluated trials. The cumulative evidence was classified as high to moderate, which was considered acceptable. Conclusion: It seems that more intense and structured pharmacist interventions can improve patient adherence to antibiotics.

1. Introduction

Pharmacists should be available daily to patients, at both hospitals and/or community pharmacies. Pharmacists should ensure effective therapy management (e.g., patient adherence, medication-related outcomes, pharmacovigilance, and reconciliation of therapy), in addition to preparing, obtaining, storing, securing, distributing, administering, dispensing, and disposing of medicinal products, among others [1,2].

Particularly, the management of antibiotic therapy by pharmacists seems relevant to ensuring patient adherence to antibiotics. In the European Union, pharmacists are required by law (i) to dispense prescribed antimicrobials, (ii) to ensure the comprehension of patients about the dosage, frequency, and duration of treatment, (iii) to actively participate in the disposal of non-used antibiotics, (iv) to handle notifications of drug-adverse reactions, (v) to provide information and clarify doubts about the precautions, contraindications, and interactions of antimicrobials, and (vi) to participate in public health programs/campaigns about the rational use of antibiotics [2].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) key facts, “the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in humans, animals and plants are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens”, with the possible appearance of antimicrobial resistances (AMRs). AMRs occur “when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines”, and they are estimated to have been directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths at a global level in 2019 [3]. Decreased patient adherence to antibiotics can favor the appearance of AMRs, as well as a reduction in treatment efficacy [2,3].

Patient adherence to antibiotics is related to the completion of an antibiotic course as prescribed (not self-medicating) [4]. Compliance and adherence are interrelated concepts. For instance, compliance can be defined as “the extent to which the patient’s behavior matches the prescriber’s recommendations”, and adherence can refer “to a process, in which the appropriate treatment is decided after a proper discussion with the patient” [5].

The education of patients by pharmacists can support ameliorated patient adherence to antibiotics, symptom assessment, dispensing first-line antibiotics, and decreasing the OTC dispensing of antibiotics, consequently contributing to minimizing the risk of AMRs and ensuring the efficacy of treatment according to findings from some studies [4,6]. However, the systematic review and metanalysis of Lambert et al. (2022) concluded that “adherence to antibiotics did not significantly increase after pharmacist-led interventions”, based on the findings of 9 out of 17 selected studies [6]. Thus, the following research questions were defined:

- What is the impact (positive or negative) of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics in the selected studies?

- What are the types of pharmacist communication-based interventions to improve antibiotic adherence adopted in community and hospital pharmacies in the selected studies?

Additionally, primary and secondary objectives were defined, as follows:

- To evaluate the impact of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics in the selected studies (primary objective).

- To identify different types of pharmacist communication-based interventions to improve antibiotic adherence in the selected studies (secondary objective).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was not required since the present work is a systematic review.

2.2. Type of Study, Previous Registration, and Published Protocol

A systematic review was conducted following the requirements of the JBI guidance [7] and reported according to the PRISMA checklist and flow diagram [8]. The full version of the PRISMA-P checklist applied to the present systematic review can be consulted in a previous publication [9]. The detailed protocol of the present systematic review is registered in OSF Registries (registration number: osf.io/sba2z).

2.3. Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO)

The PICO model was used to support the formulation of objectives and develop the search strategy [10] as follows: population (pharmacists from a community or hospital pharmacy); intervention (any pharmacist communication-based interventions, such as patient counseling/education, interviews, workshops, the provision of written information, or other); comparison (controlled trial: control group vs. group of patients enrolled in a pharmacist communication-based intervention), and outcomes (positive or negative impact on patients’ antibiotic adherence).

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: Controlled trials aimed at evaluating the impact of pharmacist communication-based intervention on patients’ antibiotic adherence in a community or a hospital pharmacy (control group vs. any communication-based pharmacist intervention group). Patients had to take at least one antibiotic. Only original research was included. Exclusion criteria: Published papers not written in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, or Italian. Commentaries, reviews, qualitative studies, letters to editors, and preprints were also excluded.

2.5. Screened Databases/Searched Resources, Keywords, and MeSH Terms

Synonyms, related keywords (e.g., adherence and compliance) and/or MeSH terms (Table 1) were selected to ensure the inclusion of a broader number of studies than those identified in previously published reviews related to the present topic, as well as to identify the most comprehensive findings/studies [6,11]. PubMed was selected because it is an optimal tool in biomedical electronic research. SciELO was selected to ensure the inclusion of papers in Spanish and Portuguese. Cochrane Library was selected to ensure the detection of previous reviews related to the present topic. Google Scholar covers most scientific fields and comprises around 389 million records, i.e., a much higher number of records than other databases/resources [12].

Table 1.

Search strategy per searched resource.

2.6. Dates of Searches per Searched Database/Resource and Covered Timeframe

The searches were conducted without a time limit. Searches were conducted in January 2024. The searches were, respectively, carried out as follows: PubMed (6-1-2024), Cochrane Library (7-1-2024), SciELO (8-1-2024), and Google Scholar (11-1-2024). PDFs of all searches were archived for later consultation (if necessary).

2.7. Screening Process and Data Collection

The screening process and data collection were conducted by just one researcher, as follows (steps 1–4).

Step 1: (i) Search of the strings of keywords per each database/resource; (ii) exclusion of duplicated studies; (iii) titles and abstracts were read; (iv) selected papers based on title/abstract were archived; and (v) consultation of the full version of all studies/trials before validating their exclusion/inclusion. Motives of exclusion were annotated.

Step 2: Reassessment of the selected studies/trials to validate their inclusion/exclusion. Motives of exclusion were annotated.

Step 3: a tabular format was used to register the extracted data.

Step 4: Steps 1 to 3 were repeated because just one researcher carried out the present systematic review; i.e., steps 1 to 3 were repeated through two separate procedures with the aim of identifying eventual discrepancies. Discrepancies were not identified.

2.8. Collected Variables and Data Synthesis

The data collected were registered in a tabular format (see Table 2). The collected data were double-checked. The study findings were synthetized based on a narrative synthesis with reference to the quantitative/qualitative collected data.

Table 2.

Main findings from the selected studies/trials.

2.9. Quality Assessment of the Selected Studies

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) quality assessment tool for Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies was applied [34]. Question 4 of the NHLBI of the quality assessment tool, “4. Were study participants and providers blinded to treatment group assignment?” was excluded because it is impossible to keep community or hospital pharmacists blind regarding a certain intervention. The JCR impact factor of the journal of the selected studies/trials was quantified because papers from journals with a JCR impact factor are peer-reviewed.

2.10. Evaluation of the Risk of Bias and Confidence in Cumulative Evidence

A more simplified methodology based on the original tool (i.e., Rob2 for randomized trials) was adopted in the evaluation of the risk of bias of the selected randomized trials because the detailed protocols of the selected trials were not fully available in the published papers, and the selected trials evaluated a social intervention (i.e., the impact of a pharmacist communication-based intervention on patient adherence to antibiotics) (not the administration of a medicine in a clinical trial). The specifically evaluated variables were as follows [35,36]:

- “Random sequence generation”;

- “Allocation concealment”;

- “Blinding of outcome assessment”;

- “Not incomplete outcome data”;

- “Not selective reporting”;

- “Not other bias”.

Particularly, the option “blinding of participants and/or personnel” was not considered in the present evaluation because it is not applicable in the present social evaluation (i.e., pharmacists are required to know about the intervention).

The evaluation of the risk of bias for the non-randomized selected studies was based on the ROBINS-I tool, with the following evaluations [37]:

- Pre-intervention (bias due to confounding and bias in the selection of participants for the study);

- During the intervention (bias in classification of interventions);

- Post-intervention (bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes, and bias in the selection of the reported result).

2.11. Confidence in Cumulative Evidence: GRADE-CERQual

The GRADE-CERQual for qualitative studies was adopted to evaluate the confidence in cumulative evidence since the adopted statistical methodologies were variable between the selected studies, and the magnitude of the effects was not presented in all cases. Overall, four elements were evaluated: (i) methodological limitations, (ii) coherence, (iii) adequacy of data, and (iv) relevance. The findings were rated for confidence as follows: “Very low”, “Low”, “Moderate”, and “High” [38].

GRADE for quantitative studies was not adopted to evaluate the confidence in cumulative evidence because the study methodologies of the selected trials were too heterogeneous. The selected trials were based on different types of pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., interviews, phone calls, different educational interventions, etc.) and were not clinical trials. For instance, a proper evaluation of inconsistency, indirectness, or imprecision was not considered viable because the adopted methodologies of interventions between the selected trials were different. Thus, the evaluated effect sizes were not comparable, and GRADE for quantitative studies was not applicable.

2.12. Motives for Not Carrying out a Metanalysis

A meta-analysis to support a quantitative analysis was not carried out because the measures of effect were not presented in all the selected studies; the selected trials were not sufficiently homogeneous in terms of their design and comparators, and the adopted statistical methodologies of the selected trials were heterogeneous (for additional information, please see the subsection on limitations) [10].

3. Results

3.1. PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram

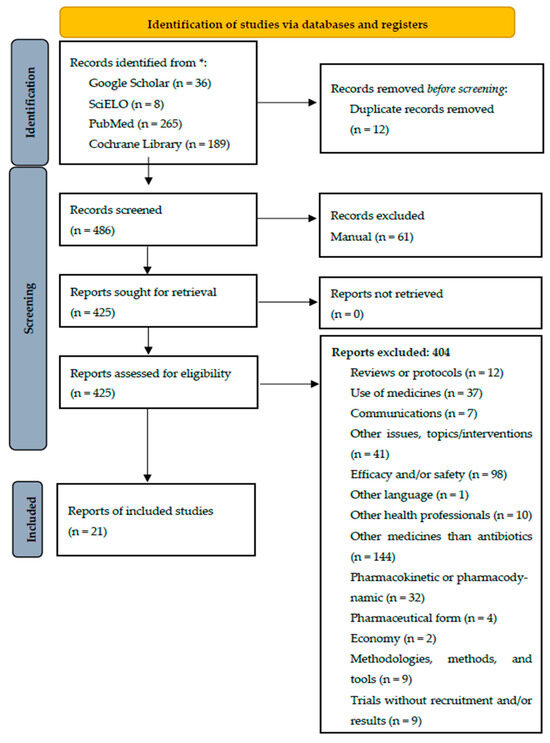

Overall, 21 studies/trials were selected. The identification of studies via databases/resources and registers is represented in Figure 1, which followed the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews [8,39].

Figure 1.

Identification of studies via databases/resources and registers for the present systematic review. * Number of records identified from each database/resource.

3.2. Main Findings: Collected Variables

The main findings of the selected studies/trials are presented in Table 2.

Globally, the impact of pharmacist intervention was positive on patients’ adherence to antibiotics in the analyzed studies. Statistically significant differences between the control and intervention groups were not found in one-third of the selected trials (7; 33.3% of the 21 selected trials) [16,17,18,23,25,26,30]. However, the findings/proportions were quantitatively better in the intervention group than in the control group of these seven trials [16,17,18,23,25,26,30].

3.3. Different Types of Pharmacist Communication-Based Interventions to Improve Antibiotic Adherence

The adopted methodologies for pharmacists to improve patient adherence were conveniently grouped by type of intervention and/or treatment interventions in five groups (i.e., according to five descriptors) as follows: (i) visual aid [13,26]; (ii) the dispensation of a syringe for correct dosing or personalized delivery (per unit) [14,19]; (iii) using both oral and written information in the intervention group [17,20,23,25,32,33]; (iv) oral education-based interventions (excluding counseling in the case of H. pylori treatment) [18,22,24,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]; and (v) counseling in the case of H. pylori treatment [15,16,21] since these therapeutics usually involve multiple medicines, which may complicate patient adherence. These descriptors were used to classify the selected studies (Table 2) and carry out a more comprehensive discussion.

3.4. Quality Assessment of the Selected Studies

Two out of the twenty-one selected studies/trials were not included in the quality assessment: an abstract [28] and a pilot study [33]. Overall, questions 9–11 and 13 from the NHLBI assessment tool were 100% compliant for all the selected studies [34] (Table 3).

Table 3.

% of compliant assessments according to the NHLBI tool [34].

The results from questions 1 and 6–8 (compliance > 80%) of the NHLBI assessment tool were classified as potentially acceptable [34] because these trials were based on social-work interventions (e.g., they were not clinical trials specifically designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a certain medicine). Conversely, the results from questions with <80% compliance (i.e., questions 2–3, 5, 12, and 14 from the NHLBI assessment tool) were classified as potential quality issues. Detailed, full reports of the selected papers were not identified. Moreover, authors from the selected trials were not contacted to check whether the evaluations from these questions (i.e., questions 2–3, 5, 12, and 14) were (or were not) implemented and/or carried out.

3.5. Risk of Bias

Two of the selected trials were not evaluated in the assessment of a risk of bias: an abstract [28] and a pilot study [33]. The only eventually identified bias was related to the selection of participants because the randomization methodology was not reported in these two trials [24,25]. The results of the selected randomized trials (n = 17) were as follows: “Incomplete outcome data” or “elective reporting” were not detected (100% trials were classified as compliant, i.e., no risk of bias) and the % of eventual risk of bias (non-conformities) were as follows: “not reporting blinding of outcome assessment” (76.5%); “not reporting allocation concealment” (70.6%); “not reporting random sequence generation” (47.1%); and risk of “other bias, i.e., not exhaustively describing or not describing at all the routine pharmaceutical intervention” (35.3%).

3.6. Confidence in Cumulative Evidence: GRADE-CERQual

The findings concerning confidence in cumulative evidence through GRADE-CERQual are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

GRADE-CERQual summary.

4. Discussion

In general, positive outcomes were achieved in all the selected studies (n = 21) (i.e., better results in the intervention group than in the control group), with significant differences in two-thirds of the selected studies and non-significant differences in one-third of the selected studies. Statistically significant differences could not have been achieved because of the heterogeneity of the methodologies of the selected studies, differences in patient populations, variability in intervention protocols, limited follow-up durations, different practices between hospital and community pharmacists, the possibility of different practices between different regions, and the fact that pharmacists were required to intervene in both groups (e.g., intervention vs. control or usual care), which may have been due to deontological motives. Overall, usual care was provided in the control group vs. an intervention group (i.e., usual care plus an additional intervention, involving a reinforced pharmacist intervention) (Table 2). It seems that usual care, or routine pharmaceutical practice, can be optimized through a more intense and structured pharmacist intervention.

The present systematic review is the most representative work on the present topic (21 analyzed trials) as far as is known. However, the previous systematic review and metanalysis of Lambert et al. (2022) found that “adherence to antibiotics did not significantly increase after pharmacist-led interventions” through findings that were based on only 9 out of the 17 selected studies [6]. The objectives of the systematic review and metanalysis of Lambert et al. (2022) were “to assess the effects of community pharmacist-led interventions to optimize the use of antibiotics and identify which interventions are most effective” [6], i.e., broader objectives than the objectives of the present systematic review. It is important to note that, of the 9 (out of 17) studies identified by Lambert et al. specifically concerning the impact of pharmacist-led interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics, 8 were also included in the present systematic review [17,20,23,25,26,29,32,33]. One of these nine studies was not included in the present systematic review because it was impossible to retrieve.

4.1. Different Types of Pharmacist Communication-Based Interventions to Improve Antibiotic Adherence

4.1.1. Visual Aid

A visual aid seems to be a simple and accessible methodology to improve patient adherence to antibiotics, such as in the case of nonliterate patients [13]. Health information materials with pictures improved patient knowledge/understanding, and recall can support better patient adherence to medicines (e.g., pictograms or other visual aids) [13,26,40].

4.1.2. Dispensation of a Syringe for Correct Dosing or Personalized Delivery (Per Unit)

Particularly, the use of oral syringes facilitated the measurement and administration of liquid medicines by caregivers, and it minimized the exposure to any potentially unpleasant smell [14,41]. The demonstration on how to carry out correct dosing using a syringe and the confirmation of patients’ understanding of this procedure can reduce dosing mistakes [42].

The personalized delivery of antibiotics vs. standard packaging also produced a strong positive impact on patient adherence [19]. Advantageously, antibiotic waste can be reduced through the personalized delivery of antibiotics [19,43]. These facts were also verified in other studies. For instance, caregivers better adhered to the use of pre-packed tablets than chloroquine syrup, with only 20% of the caregivers using an accurate 5 mL measure for children diagnosed with malaria (aged 0–5 years) [43].

4.1.3. Oral Plus Written Information

The use of both oral and written information, such as a package insert for medicines, by patients may have a positive, statistically significant impact on adherence to medication/antibiotics, according to their perceptions [17,20,23,25,32,33]. It seems that leaflets/written information can be successfully dispensed to support pharmacists’ structured counseling and, consequently, enhance patients’ adherence to antibiotics. However, statistically significant findings were not achieved in all the studies [44], which may be explained by the use of too-complex materials or non-pre-tested written information.

4.1.4. Oral Interventions

Pharmaceutical care is defined as a “patient-centred pharmacist activity to improve medicines management by patients and encompasses a variety of specific services” [45]. Structured interventions (e.g., oral interventions) are known for producing positive patient health outcomes, such as resolving drug-related problems or improving medicine adherence [46]. The oral pharmaceutical interventions of the selected trials adopted very heterogeneous methodologies, as follows: motivational interviews to address negative health behaviors, such as adherence [18]; reinforced education about the correct use of antibiotics [22,25,28,29]; counseling about antibiotics, followed by a phone call [27]; the evaluation of the intention to take a certain antibiotic (e.g., theory of planned behavior) [30]; and the use of a model/tool to support a pharmacist intervention, followed by a follow-up phone call [31]. Phone calls can be used to monitor the safety and efficacy of antibiotic treatment, such as adherence or the eventual occurrence of side effects. It seems that the structured education of patients by a pharmacist is a successful methodology to improve patient adherence to antibiotics. Structured education can be supported through a tool to check and orient a pharmaceutical consultation [31], for example, if integrated in the scope of a pharmaceutical care program.

4.1.5. Counseling in the Case of Helicobacter pylori Treatment

Helicobacter pylori infection is related to diverse upper gastrointestinal diseases, such as chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer. Half of the world population is estimated to carry H. pylori, with the main therapy involving the use of three or four medicines (e.g., amoxicillin, furazolidone, clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, and a proton pump inhibitor). The enhancement of patient medication adherence, reduction in adverse drug reactions, and improvement in H. pylori eradication rates can be advanced with statistical significance through pharmacists’ intervention [15,16,21,47]. The adoption of structured counseling, the implementation of an educational program, a follow-up phone call, or the provision of additional counseling successfully strengthened patient adherence [15,16,21], which may be explained because of the complexity of H. pylori treatment (e.g., the simultaneous use of three or four medicines and different drug regimens).

4.2. Comparison Between Different Types of Pharmacist Communication-Based Interventions to Improve Antibiotic Adherence

All pharmacist interventions ameliorated patient adherence (significant differences in two-thirds of the selected studies and non-significant differences in one-third of the selected studies), although it is not possible to conclude about the best adopted methodology or to compare findings from different research since the study designs, statistical methodologies (e.g., Tukey and Fisher’s LSD multiple-comparison test, Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, etc.) [13,15,18], methods, interventions, settings, etc. were different and very heterogeneous across the selected studies (n = 21) (Table 2). For instance, the concept of adherence and compliance was applied with the same meaning in some of the selected studies, and the methodologies for measuring patient adherence were heterogeneous between the selected studies, such as patient self-assessment (e.g., phone calls or presential interviews at a pharmacy), pill counts, the application of formulas, the Morisky–Green test, or mixtures of these methodologies (Table 2). Ideally, the application of more than one methodology is recommended to evaluate patient adherence since patients’ self-reporting of adherence may be related to imprecisions (e.g., memory issues) or since pill counts per se are not enough to check adherence because patients may not take antibiotic pills correctly (e.g., duplication of pill intake).

4.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias of the Selected Studies

The interpretation of the findings of the present systematic review may have been affected by some potential quality issues and/or the risk of study bias. For instance, the sample size calculation (e.g., with at least 80% power) and/or “an intention-to-treat analysis” were not reported in an expressive number of trials, which may have affected the quality of the study findings. Likewise, not exhaustively describing (or not describing at all) routine pharmaceutical interventions may have been related to a negative impact on study reproducibility, as well as on studies’ comparability with other, similar studies. In contrast, not carrying out “blinding of outcome assessment” may not have produced major quality issues and/or a risk of bias because, in most of the selected studies, pharmacists were required to ask closed or semi-closed questions to assess adherence (i.e., outcome assessment), as well as to collect and record patients’ replies.

In general, “allocation concealment” (researchers do “not know in advance or cannot guess accurately, to what group the next person eligible for randomization will be assigned”) was not reported in the selected studies, although nowadays, computer-generated randomization/random sequence generation is one of the most common randomization methodologies. It is important to note that only the published papers were assessed (not the full protocol studies) for both randomized and non-randomized trials. Thus, some quality evaluations may not have been precise since the full versions of the studies’ protocols were not analyzed. Most trials were published in journals with a JCR impact factor higher than two, which is necessarily related to peer-reviewed journals.

4.4. Limitations

It was not possible to carry out a meta-analysis regarding, some of the selected studies´ use of the following qualities: “different methods to define exposure and/or outcome”; “different study designs were used”; “different analyses and methods were applied to generate the estimates”; or “there were variation in populations included across different studies; studies differ by their quality/risk of bias” [10,48,49]. Additionally, to carry out a meta-analysis, “a summary statistic is calculated for each study, to describe the observed intervention effect in the same way for every study and the summary statistic may be a risk ratio if the data are dichotomous, or a difference between means if the data are continuous” [48], although measures of effect were not reported in all the selected studies. The potentially detected study quality may have affected the accuracy of the findings of the present systematic review. Pharmacists’ practices and regulations, as well as practices and interactions with hospital and community pharmacists, may differ across the selected trials, given that the trials were carried out in different countries.

Limitations of Methods

It is important to notice that applying a clinical studies mindset to a social phenomenon can be epistemologically and ontologically misleading. Thus, the adopted methodologies in the present study, such as the NHLBI Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies, a simplification of Rob2 for randomized trials, or GRADE-CERQual can also be related to some constraints. Positively, the adopted methodology respects all the requirements defined for a narrative summary of evidence as follows: group studies (step 1); following the same synthesis consistently (step 2); reporting findings clearly (step 3); and discussing findings objectively (step 4) [49].

The adopted methodological tools were applied twice by just one researcher. The number of screened databases may have been limited since Scopus and Web of Science (paid databases covering most scientific fields) were not browsed. However, the number of selected studies in the present systematic review was broader than a previous review and meta-analysis about a related topic (21 in the present systematic review vs. 17 in the systematic review and meta-analysis by Lambert et al., with only 9 out 17 specifically covering patients’ adhesion to antibiotics) [6]. CiteScore could have been used instead of the JCR impact factor, although CiteScore and the JCR impact factor metrics seem to be positively correlated [50]. Only published papers were evaluated (not the full protocols), which may have introduced some inconsistencies in the performed evaluations of quality or risk of bias.

4.5. Strengths

As far as is known, this is the first systematic review to have specifically explored the impact of hospital or community pharmacists’ communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics. The selected studies involved an expressive number of participants, which may have contributed to higher research accuracy. The studies were conducted in different regions, which is likely to support an easier extrapolation of data. Systematic reviews with (or without) meta-analyses are likely to provide appropriate and a high-level quality of evidence [51]. The findings of the present systematic review are congruent with data from previous related studies (e.g., improvement in patient adherence, knowledge of medications, quality of life, physical function, and symptoms in patients receiving a medication-adherence intervention or the relationship between the healthcare and patient, such as the provision of patient education, training, and follow-up, and the time availability of consultation, among others, supporting improved patient adherence) [52,53].

5. Conclusions

Patient adherence to antibiotics improved with more intense pharmacist communication-based interventions when compared to the routine/regular practice at hospitals or community pharmacies in the analyzed studies. However, statistically significant findings between usual care vs. intensive care were not achieved in all the selected trials. Thus, a more structured and proactive pharmacist intervention is likely to significantly support and improve patient adherence to antibiotics.

Pharmacists’ interventions to improve antibiotic adherence were very heterogeneous, such as oral and/or written education-based interventions, intensive counseling, interviews, visual aids (e.g., pictograms), follow-up phone calls, or personalized delivery (i.e., the dispensation of an exact number of pills). Finally, reinforced pharmaceutical interventions seem to be especially useful for patients with low literacy and in more complex therapeutic regimes, such as H. pylori treatment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

CBIOS-Universidade Lusófona’s Research Center for Biosciences and Health Technologies.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kusynová, Z.; Ham, H.A.v.D.; Leufkens, H.G.M.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K. Longitudinal study of Good Pharmacy Practice roles covered at the annual world pharmacy congresses 2003–2019. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. EU Guidelines for the Prudent Use of Antimicrobials in Human Health. 2017. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017XC0701(01)&from=ET (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Lee, S.Y.; Shanshan, Y.; Lwin, M.O. Are threat perceptions associated with patient adherence to antibiotics? Insights from a survey regarding antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance among the Singapore public. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, S. What’s in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J. Psychiatry 2014, 4, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M.; Smit, C.C.; De Vos, S.; Benko, R.; Llor, C.; Paget, W.J.; Briant, K.; Pont, L.; Van Dijk, L.; Taxis, K. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of community pharmacist-led interventi3ons to optimise the use of antibiotics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 2617–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Checklist and Flow Diagram. 2024. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Pires, C. Impact of controlled pharmacist communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics: A protocol of a systematic review. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2023, 20, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 350, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMars, M.M.; Perruso, C. MeSH and text-word search strategies: Precision, recall, and their implications for library instruction. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoh, L.N.; Shepherd, M.D. Design, development, and evaluation of visual aids for communicating prescription drug instructions to nonliterate patients in rural Cameroon. Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 31, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.R.; Rimsza, M.E.; Bay, R.C. Parents can dose liquid medication accurately. Pediatrics 1997, 100 Pt 1, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eidan, F.A.; McElnay, J.C.; Scott, M.G.; McConnell, J.B. Management of Helicobacter pylori eradication—The influence of structured counselling and follow-up. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, V.J.; Shneidman, R.J.; Johnson, R.E.; Boles, M.; Steele, P.E.; Lee, N.L. Helicobacter pylori eradication in dyspeptic primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial of a pharmacy intervention. West J. Med. 2002, 176, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beaucage, K.; Lachance-Demers, H.; Ngo, T.T.-T.; Vachon, C.; Lamarre, D.; Guévin, J.-F.; Martineau, A.; Desroches, D.; Brassard, J.; Lalonde, L. Telephone follow-up of patients receiving antibiotic prescriptions from community pharmacies. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2006, 63, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyler, R.; Shvets, K.; Blakely, M.L. Motivational Interviewing to Increase Postdischarge Antibiotic Adherence in Older Adults with Pneumonia. Consult. Pharm. 2016, 31, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treibich, C.; Lescher, S.; Sagaon-Teyssier, L.; Ventelou, B. The expected and unexpected benefits of dispensing the exact number of pills. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, L.M.; Cordina, M. Educational intervention to enhance adherence to short-term use of antibiotics. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoiab, A.A.; Alsarhan, A.; Khashroum, A.O. Effect of pharmacist counseling on patient medication compliance and helicobacter pylori eradication among Jordanian outpatients. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2023, 60, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, B.A.; Hijazi, B.M.; Al-Husein, B.A.; Oqal, M.; Al-Natour, L.M. Adherence and utilization of short-term antibiotics: Randomized controlled study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, J.A.; Pierce, W.; Muhlbaier, L. A randomized, controlled study of an educational intervention to improve recall of auxiliary medication labeling and adherence to antibiotics. SAGE Open Med. 2013, 1, 2050312113490420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marque, P.; Le Moal, G.; Labarre, C.; Delrieu, J.; Pries, P.; Dupuis, A.; Binson, G.; Lazaro, P. Assessment of the impact of pharmacist-led intervention with antibiotics in patients with bone and joint infection. Infect. Dis. Now. 2023, 53, 104671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktay, N.B. The role of patient education in adherence to antibiotic therapy in primary care. Marmara Pharm. J. 2013, 17, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merks, P.; Świeczkowski, D.; Balcerzak, M.; Drelich, E.; Białoszewska, K.; Cwalina, N.; Zdanowski, S.; Krysiński, J.; Gromadzka, G.; Jaguszewski, M. Patients’ Perspective and Usefulness of Pictograms in Short-Term Antibiotic Therapy—Multicenter, Randomized Trial. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paravattil, B.; Zolezzi, M.; Nasr, Z.; Benkhadra, M.; Alasmar, M.; Hussein, S.; Maklad, A. An Interventional Call-Back Service to Improve Appropriate Use of Antibiotics in Community Pharmacies. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormeci, M.; Macit, C.; Kocaagaoglu, O.; Yalcin, S.; Gunaydin, I.; Yoldas, F.; Uygun, A.; Guveneroglu, G. DI-007—Assessment of the effect of patient education on compliance with antibiotic treatment in ambulatory patients. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 22, A77–A78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.B.; Dorado, M.F.; Guerrero, J.E.; Martínez, F.M. The effect of an educational intervention to improve patient antibiotic adherence during dispensing in a community pharmacy. Aten. Primaria 2014, 46, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Lawton, R.J.; Raynor, D.K.; Knapp, P.; Conner, M.T.; Lowe, C.J.; Closs, S.J. Promoting adherence to antibiotics: A test of implementation intentions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 61, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowati, A.R.; Pradnyaparamita, D.D.; Budayanti, N.S.; Diantini, A.; Januraga, P.P. Modified pharmacy counseling improves outpatient short-term antibiotic compliance in Bali Province. Int. J. Public Health Sci. (IJPHS) 2022, 11, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.M.; Espejo, J.S.; Gutiérrez, L.; Machuca, M.P.; Herrera, J. The effect of written information provided by pharmacists on compliance with antibiotherapy. Ars. Pharm. 2003, 44, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gotsch, A.R.; Liguori, S. Knowledge, attitude, and compliance dimensions of antibiotic therapy with PPIs: A community pharmacy-based study. Med. Care 1982, 20, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Quality Assessment Tool for Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; (Updated August 2023); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Cochrane, AB, Canada, 2023; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018, 13 (Suppl. S1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merks, P.; Cameron, J.; Bilmin, K.; Świeczkowski, D.; Chmielewska-Ignatowicz, T.; Harężlak, T.; Białoszewska, K.; Sola, K.F.; Jaguszewski, M.J.; Vaillancourt, R. Medication Adherence and the Role of Pictograms in Medication Counselling of Chronic Patients: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 582200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Rachidi, S.; LaRochelle, J.M.; Morgan, J.A. Pharmacists and Pediatric Medication Adherence: Bridging the Gap. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 52, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younas, E.; Fatima, M.; Alvina, A.; Nawaz, H.A.; Anjum, S.M.; Usman, M.; Pervaiz, M.; Shabbir, A.; Rasheed, H. Correct administration aid for oral liquid medicines: Is a household spoon the right choice? Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1084667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, E.K.; Gyapong, J.O.; Agyepong, I.A.; Evans, D.B. Improving adherence to malaria treatment for children: The use of pre-packed chloroquine tablets vs. chloroquine syrup. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustersic, M.; Tissot, M.; Tyrant, J.; Gauchet, A.; Foote, A.; Vermorel, C.; Bosson, J.L. Impact of patient information leaflets on doctor-patient communication in the context of acute conditions: A prospective, controlled, before-after study in two French emergency departments. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e024184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.A.; Ema, P. Chapter 8: Pharmacist-led interventions to promote cardiovascular health: A review of studies from Portugal. In Zaheer-Ud-Din Babar, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sallom, H.; Abdi, A.; Halboup, A.M.; Başgut, B. Evaluation of pharmaceutical care services in the Middle East Countries: A review of studies of 2013–2020. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Pei, S.; Wang, C.; Han, G.; Kan, L.; Li, L. Treatment strategies and pharmacist-led medication management for Helicobacter pylori infection. Drug Dev. Res. 2023, 84, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; (Updated August 2023); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Cochrane, AB, Canada, 2023; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Glisic, M.; Raguindin, P.F.; Gemperli, A.; Taneri, P.E.; Salvador, D.J.; Voortman, T.; Vidal, P.M.; Papatheodorou, S.I.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Bano, A.; et al. A 7-Step Guideline for Qualitative Synthesis and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Health Sciences. Public Health Rev. 2023, 44, 1605454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okagbue, H.I.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Correlation between the CiteScore and Journal Impact Factor of top-ranked library and information science journals. Scientometrics 2020, 124, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofilos, S.I.; Tsikopoulos, K.; Tsikopoulos, A.; Kitridis, D.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Stoikos, P.N.; Kavarthapu, V. Network meta-analyses: Methodological prerequisites and clinical usefulness. World J. Methodol. 2022, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conn, V.S.; Ruppar, T.M.; Enriquez, M.; Cooper, P.S. Patient-Centered Outcomes of Medication Adherence Interventions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2016, 19, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkvord, F.; Würth, A.R.; van Houten, K.; Liefveld, A.R.; Carlson, J.I.; Bol, N.; Krahmer, E.; Beets, G.; Ollerton, R.D.; Turk, E.; et al. A systematic review on experimental studies about patient adherence to treatment. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2024, 12, e1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).