Abstract

The language use of Ukrainian war refugees has attracted the attention of researchers worldwide due to the unprecedented number of individuals displaced since the onset of the war in 2022. Earlier studies have documented a shift in language use and attitudes in Ukraine, marked by a diminished role for Russian and increased prominence of Ukrainian both within the country and among Ukrainian émigré communities abroad. However, the role of age in this process has not yet been thoroughly investigated. Moreover, research on the specific characteristics of language shift and social integration among Ukrainian refugees in Canada is still insufficient. This article reports the results of a study aimed at examining how home languages shift and the use of the official languages among Ukrainian refugees in Canada may vary by age. The vresearch employed a mixed-methods approach, based on a survey (65 participants). In this research, quantitative data were drawn from the closed-ended survey questions, and open-ended questions were employed to illustrate quantitative results for more depth and insight. The results indicate that there are no significant differences in L1 and L2 or L3 by age in this sample. The study confirms a language shift from Ukrainian-Russian bilingualism in Ukraine to Ukrainian dominance, which does not differ by age or age group. What does differ by age and generation is the proficiency in English, English use, and the perceived difficulty in learning English, whereby younger participants reported higher proficiency in English, its higher use in daily communication, and less difficulty acquiring it, as compared to their older peers. While the findings align with previous research on language use among immigrants—including the impact of age—they offer new insights into the experiences of refugees, highlighting how different age groups respond to social pressures in migration. A further contribution of this study lies in addressing the language shift from the perspectives of both younger and older refugees and establishing that the language shift in Ukraine swept across all ages.

1. Introduction

This article addresses the role of age in the language use and language attitudes of Ukrainian refugees in Canada. The factors of age and age upon arrival of immigrants and refugees in the host countries have been proven to be highly important factors in dominant language acquisition and heritage language maintenance across multiple language and culture groups (e.g., ; ). In case of Ukrainian refugees, it is possible to expect not only the typical higher difficulties with linguistic adaptation with age, but also differences in language use across generations, since the older generation in many parts of Ukraine were exposed to Russian in the USSR, and the young generation has very little or no exposure to Russian. After Ukrainian was introduced as a national language, the use of Russian language channels and any Russian use was forbidden in public, and all the secondary and postsecondary education has been conducted in Ukrainian. Moreover, the language attitudes of the participants could have been affected by the time, specifically preceding and following the Russian–Ukrainian war.

The wide impact of the Ukrainian refugee crisis is still hard to estimate. With over 6.8 million refugees, it is the largest one in the 21 century, surpassing the earlier flows of refugees from Syria (6.5 million) and Afghanistan (6.1 million) (; ). The specific features of this refugee wave were that first, it was comprised mostly of women (ages between 20–59) and children, as men between the ages of 18–60 were not allowed to leave Ukraine due to ongoing mobilization. Second, they were highly educated, could often speak English, but had no command of other European languages (; ). It is therefore not surprising that the adaptation of Ukrainian refugees in their host countries, their access to healthcare and social services, and the language barrier that they faced attracted the attention of scholars (e.g., ). In terms of language use, the refugees speak predominantly Ukrainian, but also Russian () due to the history of bilingualism in the country associated with Russian colonialism. For example, at the turn of the 21st century, 68% of Ukraine’s population identified Ukrainian as their native language and 30% Russian (). However, a language shift away from Russian towards more Ukrainian use has been occurring in Ukraine in the 21st century, with the culmination of this shift occurring after the full-fledged war with Russia started in 2022 (e.g., ; ; ). This shift was noted to partially occur in Europe among Ukrainian refugees and immigrants as well ().

Canada has taken in close to 300,000 Ukrainian war refugees (). This figure includes those who arrived under the Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel (CUAET) program, which provided temporary residence, work permits, and financial support. However, very little research has been conducted on the needs of this group, and the available studies address their adaptation (e.g., ) or healthcare access ().

Language use and attitudes by Ukrainian refugees have not been sufficiently investigated. Moreover, the impact of age, which is known to be crucial for language learning, maintenance, and language attitudes, has not been previously addressed in the literature on Ukrainian refugees in general, and the ones residing in Canada in particular. This article, therefore, explores the role of age in the language use, attitudes, learning, and maintenance among the refugees from Ukraine in Canada. In particular, the study examines whether there is evidence of language shift across Ukrainian refugees in Canada and whether this shift may differ by age. The factors of age and time periods (before and after the onset of the ongoing war) were selected for this article from a wider study of the Ukrainian refugees’ language use and attitudes in Canada.

2. Literature Review

This section considers language and age in refugee and immigrant adaptation, with a subsequent focus on Ukrainian war refugees.

2.1. Language and Age in Migration and Language Shifts

Language is central to refugee and immigrant adaptation in their host countries; it is a part of their social capital (). Learning the host country’s language is essential for finding a job, accessing healthcare, banking, and other services, social engagement, and reducing marginalization (). Lack of proficiency in the host country’s language creates linguistic isolation that blocks access to social support networks, essential information, and a sense of power in the community (). A study by () conducted in the Canadian context found proficiency in the official languages to be the strongest predictor of social integration.

On the other hand, maintenance of the home language is beneficial for cross-generational connections, community inclusion, maintaining mental balance, and a stronger cultural and ethnic identity (; ). Thus, this article’s theoretical foundation is Linguistic Equilibrium theory, which suggests that an optimal balance between home and host languages at all the varied turns of migrants’ lives is an essential part of migrant adaptation and well-being ().

Earlier studies have shown that the proficiency in the home language and the acquisition of the host language for migrants are subject to age, age at migration, and the number of years spent in the home country (). For example, age on arrival strongly predicts several dimensions of ultimate L2 attainment (pronunciation/accent, morphosyntax) (). Age and age at migration interact with exposure and use to determine L1 maintenance or attrition across the lifespan, whereby, paradoxically, older adults and those who migrate at older ages are at higher risk of measurable L1 attrition ().

Language attitudes can also differ among younger and older migrants, whereby the younger generation has more positive attitudes towards the host country languages, and the older—towards the heritage language (). Older migrants (+55) experience particularly strong language barriers that lead to dependency on family, social isolation, and reduced access to services (healthcare and others), and, therefore, their attitudes to L2 and language learning are less enthusiastic than those of younger individuals ().

In case of Ukrainian refugees, in some European countries, such as Lithuania, language barriers were found to impede their access to healthcare, social services, and employment opportunities, jeopardizing their social adaptation (). Some age-related differences in social attitudes of Ukrainian refugees regarding gender roles, democracy, and others have been observed in (), whereby the older refugees held more conservative attitudes.

In general, it is well known that in any language change and shift, it is the younger generation that typically leads the change, which gradually spreads to the older population groups (; ; ). However, the connections between language use, language shift (from Russian to Ukrainian), and age have not been explored for this group, to the best of our knowledge. Next, we will consider changes in language use in Ukraine and among immigrants and refugees abroad.

2.2. Language Use in Ukraine and in the Ukrainian Diasporas Abroad

After the independence of Ukraine in 1991, Ukrainian was proclaimed the national language of the country. However, as pointed out above, a significant proportion of population spoke Russian as their first or second language. With the strengthening of nation-building in Ukraine, a set of laws was passed, such as Bill 7633, to exclude Russian from public use, education, media (TV, radio, newspapers), and social media (). Therefore, the younger generation that included speakers of Russian as their first or second language did not have a chance to study Russian at secondary schools or universities. This process of language shift culminated with the war onset in 2022, whereby Ukrainian–Russian bilinguals have been abandoning Russian and switching to Ukrainian (e.g., ; ). Some Russian monolinguals from Ukraine attempted to learn Ukrainian as well (). This shift was particularly noticeable on social media (; ; ).

Across all the public domains, the Ukrainian language became the symbol of national identity, individual identity, and resistance to aggression. By contrast, the Russian language started to be associated with the language of the enemy and of aggression (; ).

Impacted by the media and communication with relatives in Ukraine, immigrant diasporas were mirroring the shift. Recent immigrants and then war refugees brought the “Language Divide” to their host countries. However, the language attitudes and language use appear to differ by context. For example, in Germany and Austria, Ukrainian gained symbolic prestige, while Russian retains pragmatic use (). The “pragmatic” use of Russian can be explained by the presence of a sizable Russian-speaking diaspora in these countries. In Poland, with widely spread anti-Russian sentiments held by the local population, only Ukrainian is spoken primarily by the refugees ().

In Canada, by contrast, even before the war, Ukrainian diaspora of 1.3 million by far exceeded the Russian one (about 600,000) in terms of size, accumulated resources, and influence (). However, in 2021 (the most recent population Census in Canada), only approximately 131,700 people in Canada spoke Ukrainian as the primary language at home as opposed to 309,200 speakers of Russian (). Thus, the arrival of close to 300,000 refugee speakers of Ukrainian since 2022 tipped the balance of the two languages in the country in favour of Ukrainian. A clear shift in language attitudes and language use was observed in the Ukrainian immigrant diaspora in Canada, where Ukrainian gained speakers and popularity, as opposed to a decline in the use and prestige of Russian ().

Synthesizing the research findings on the home language shift in the Ukrainian immigrant diaspora and the knowledge about the impact of age on language use and attitudes, this study poses the following research questions:

- RQ 1: What was the difference in home language use and attitudes of Ukrainian refugees by the two age groups (younger and older) prior to their move to Canada?

- RQ 2: What is the difference in language use and attitudes of Ukrainian refugees by the two age groups (younger and older) after their move to Canada?

In order to answer these questions, we designed a study with methods and materials described in the next section.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methods and tools employed in the study, as well as the participants’ basic demographic characteristics.

3.1. Participants

A total of 65 individuals participated in the survey (45 women, 19 men, and one person identified as “other gender”). The average age of participants was 34 (SD = 14.04; min = 18, max = 74). The participants’ distribution by age groups was as follows: 18–29 (N = 26), 30–39 (N = 15), 40–49 (N = 15), 50 and older (N = 9). For the purposes of the analysis, the participants were split into two age groups. The first “younger” group included 33 participants between 18–34 years old, with the average age of 23.5, StDev = 5.3. The second “older” group had 32 participants between 35 and 74; their average age was 46.2, StDev = 10.2. The above split into two groups is explained by the practice in Statistics Canada, which treats a group of “young adults” as being 18 to 34 years of age (). All the participants came to Canada 2022–2023.

The participants came mostly from the Central (n = 29) and Eastern (n = 16) parts of Ukraine, followed by the Southern (n = 9) and Western (n = 8) regions. These regions were identified in the study following the (). The participants resided in four Canadian provinces: Saskatchewan (n = 38), Alberta (n = 12), British Columbia (n = 9), and Ontario (n = 6).

3.2. Methods and Tools of the Analysis

The results of this study come from a mixed-methods analysis combining quantitative and qualitative methods. The source of quantitative data was a survey designed by the authors in consideration of earlier research studies (; ; ). The survey contained questions about participants’ demographic information (17 questions), languages and adaptation (23 questions), and language use and attitudes prior to the war and since the war onset (8 questions).

The qualitative data come from the open-ended part of the survey. Due to the limitations on the article length, we will use excerpts from open-ended questions to illustrate the points raised in the quantitative analysis.

Following the receipt of the ethics certificate by the researchers’ university, the purposive recruitment was conducted using ads placed in the English learning centre of a non-profit newcomer settlement organization, and subsequently through snowballing. The recruitment criteria were (a) being a war refugee or immigrant from Ukraine who came to Canada after February 2022, (b) being 18 years or older, and c) speaking Ukrainian and/or Russian as their first or second language. The survey was posted on SurveyMonkey (with a link to the survey available in the recruitment materials), and it was filled out online. The participants could select a language they preferred for the survey—Ukrainian, Russian, or English.

4. Results

This section examines the use of languages and attitudes toward them held by participants in Ukraine and after moving to Canada.

To analyze the results quantitatively, we employed Spearman correlation to determine whether language-related parameters covary with age (for Likert-scale types of questions). In addition, chi-squared or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine whether the responses differed across the older and the younger groups (depending on whether the responses were Likert-scale or not).

4.1. Participants’ L1, L2, and L3(-4)

First, we looked at L1 and L2 of the participants. L1 was defined as the language that they learned from their parents in the family. L2 was defined as any language they learnt in childhood in the street, from friends, or at school. The distribution by age group is represented in Table 1. As Table 1 shows, confirmed by the chi-square test, there are no significant differences in L1 of the participants by the age group (χ2 (1, N = 65) = 4.10, p = 0.25).

Table 1.

L1 of the participants.

The participants’ L2 (and 3 or 4) data are summarized in Table 2. As the Table demonstrates, combined with a chi-square test, there are no significant differences between the two age subgroups in the languages and language combinations they have in common: χ2 = 2.1, p = 0.84. English is the most common L2 for both groups, and other world languages are less frequent.

Table 2.

Participants’ L2 and L3/4.

4.2. The History of Language Use and Attitudes in the Home Country

Next, we looked at how the participants’ language use may have changed over the tumultuous recent history of Ukraine. The questions were arranged along the crucial points in time: before 2014, between 2014 and 2022, and after 2022. The year 2014 was marked by the annexation of the Crimea and the beginning of the civil unrest in the Russian-speaking Donbas area. In 2022, Russia started a full-fledged war against Ukraine.

4.2.1. Language Use in Ukraine Prior to 2014

When we asked the participants which language they used in Ukraine prior to 2014, they produced responses summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Language use in Ukraine prior to 2014.

Before 2014, there were more bilingual individuals in the older group, and more Russian speakers in the younger group. This difference is not significant in the chi-square test (χ2 = 5.37, p = 0.067). The correlation between the use of languages and age also misses the significance level (Rs = 0.24, p = 0.057). However, the Kruskal-Wallis test does show significance in the individual responses by group: H = 4.03 (1, N = 65), p = 0.044. This result is difficult to interpret without conducting more research on the migration patterns of the younger generation with a larger sample.

As the participants point out explaining their language use prior to 2014 in open-ended responses, some of them spoke only Ukrainian, some of them have different amounts of fluency in Russian as well (Example 1). Some participants used the two languages across different domains, such as work and home (Example 1-b,d). The code, gender and age of the participants are indicated in brackets.

- Example 1.

- “Лише українськoю мoвoю, завжди знала, щo наша мoва наймилoзвучніша!” (S7A7, F, 19)[Only in Ukrainian, always knew that our language is the sweetest sounding.]

- “Дo 2014 рoку спілкувався як українськoю, так і рoсійськoю. Ставлення дo мoв булo рівнoзначне” (RP05, M, 18)[Until 2014, I spoke both Ukrainian and Russian. The attitude towards the languages was the same.]

- “Poсійська, я не бачила прoблеми в спілкуванні цією мoвoю, вважала її ріднoю” (NS23, F, 23)[Russian, I did not see a problem speaking this language and I considered it my native one.]

- “Українська на рoбoті—вчила, булo oбoв’язкoвo рoсійська в пoбуті, бo рoсійськoмoвне містo—булo зручнo”. (LЕ21, F, 46)[I learned Ukrainian at work, and Russian was a must in everyday life, because it was a Russian-speaking city—it was convenient.]

4.2.2. Language Use in Ukraine Between 2014–2022

Between 2014 and 2022, there was no major change in the language use and attitudes among all the participants. As shown in Table 4, over 65% in each group reported “no change”. Second, the distributions of responses are very similar across the two age groups: χ2 = 5.70, p = 0.46, df = 6.

Table 4.

The change in language use and attitudes between 2014 and 2022 by age group.

The participants’ diverse attitudes to language use between 2014–2022 are illustrated in Example 2.

- Example 2

- “I developed strong beliefs about importance of Ukrainian language. English language was thought to be important as well but only as a second language.”(SSO4, M, 29).

- “Українськoю рoсійськoю, ставлення булo нoрмальне я не слідкував за нoвинами та не oсвідoмлював всієї пoлітичнoї ситуації в Україні “ (UL29, M, 42).[Ukrainian Russian, the attitude was normal: I didn’t follow the news and wasn’t aware of the whole political situation in Ukraine]

- “Nothing really changed for me. Language is just a matter of communication to me.” (AA11, M, 67).

- “Kардинальнo—рoсійську виключила, англійськoї з’явилoсь багатo”[Cardinally—Russian was eliminated, a lot of English appeared] (ni25, F, 25).

4.2.3. Language Use in Ukraine After 2022

After 2022, the majority of the participants (41 from 65 = 65%) reported a change in language use, and 24 out of 65 (37%) did not (ref. Table 5). The participants who did not change their language use were primarily those who spoke Ukrainian before or those who had already changed their language use and attitudes in the earlier period. The participants who changed their language use after the war onset started to use more Ukrainian, switched from Russian to Ukrainian, developed negative attitudes to Russian, and used less Russian. The change in language use occurred irrespective of age, as shown below in Table 5 and confirmed by a chi-square test (χ2 = 5.07, p = 0.53, df = 6)

Table 5.

Language use after 2022 in Ukraine.

The participants explain the language change in the following words (Example 3)

- Example 3

- “Started to dislike Russian more” (FD24, M,34)

- “Да изменилoсь. В Украине люди стараются гoвoрить тoлькo на украинскoм.” (13ZA, F, 44)[Yes, it changed. In Ukraine, people are trying to speak only in Ukrainian.]

- “Рoсійську мoву не викoристoвую.Ставлення нейтральне, не дивлюсь фільмів, та не слухаю пісень цією мoвoю.” (A21Y, F, 21)[I don’t use Russian. My attitude is neutral; I don’t watch movies or listen to songs in this language.]

4.2.4. Discontinuing Russian

When asked whether they stopped learning or using any language after 2022, in total, 27 participants (41.5%) answered that they have dropped Russian (14 in the younger group and 13 in the older group), i.e., the Russian language was dropped by almost equal numbers of participants across the age groups, i.e., age was not a factor in discontinuing Russian for the current dataset. Russian was the only language that participants stopped using since 2022.

4.3. Language Use and Attitudes upon Moving to Canada

In this subsection, we report the data related to language use by participants after their move to Canada.

4.3.1. Language Use and Attitudes Change

Upon immigration to Canada, there was again no difference detected in language use and attitude change by the groups; they are almost identical in their use of languages, with the majority (about 78% in each group) noting the increase in English use (χ2 = 4.46; p = 0.48, df = 5) (ref. Table 6).

Table 6.

Language use and attitudes in Canada.

Some illustrations are provided in Example 4

- Example 4.

- “I had to learn and adapt to English society, which improved my English drastically. My Ukrainian vocabulary got mixed with other regions’ dialects as I could only talk to people from other regions” (SS04, M, 48)

- “I focused a lot on improving my French. I also tried to improve my knowledge of Russian since my speaking skills have never been developed.” (AP18, F, 25)

- “Пoчав більше викoристoвувати англійську, та пoкращувати її, на рoбoті працюю переважнo з Українцями та пoляками.” (RO11, M, 32)[I started using English more and improving it. At work, I work mainly with Ukrainians and Poles].

4.3.2. Self-Reported English Proficiency

In this section, we will look at the self-reported English language proficiency by the participants at the time of their move to Canada and at the time of the study (conducted approximately 2–2.5 years after most participants moved to Canada). “Self-reported” proficiency indicates participants’ selection of their proficiency level from Likert-scale rubrics provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

English proficiency by the age groups at the time of moving to Canada.

- (A)

- English proficiency at the time of moving to Canada

The participants’ self-reported proficiency at the time of their moving to Canada is summarized in Table 7, which shows that younger participants were more proficient in English than their older peers. This difference is significant (H = 9.26 (1, N = 65), p = 0.0023). The covariance between age and self-declared English proficiency is also demonstrated by the correlation between the two variables (rs = −0.46, p = 0.0001)

As the study demonstrates, younger individuals are more proficient in English as compared to the older group.

- (B)

- English proficiency at the time of the study

Self-declared English proficiency correlates with age, whereby younger individuals had a higher fluency at the time of the study (Rs = −0.56, p(2-tailed) < 0.00001). The Kruskal-Wallis test also confirmed the existence of a significant difference between the English proficiency across the two groups (H = 14.63 (1, N = 65), p = 0.00013). The differences between the two groups in self-evaluated English proficiency at the time of the study are represented in Table 8.

Table 8.

English proficiency by age group at the time of the study.

As Table 7 and Table 8 demonstrate, both groups progress in their English proficiency over just 1 or 2 years since their move to Canada. However, three participants from the older group still have no command of English at the time of the study, and most older participants speak very little or some English.

We are not reporting French proficiency or use here and in subsequent subsections, as only five individuals had any command of the language either at the time of moving to Canada or at the time of the study. Therefore, no meaningful comparisons across age groups could be conducted.

4.3.3. Daily Language Use by Participants

When we asked the participants to identify the approximate percentage of their use of English, Russian, French, and Ukrainian, we observed the results presented in Table 9. The participants did not have to calculate the exact percentage so that it would be 100% in total, but provide an approximate estimate. Therefore, we treat this variable as a 100-point scale and use the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the responses across the groups. On the other hand, since the variable is on a continuous scale, we also report average values for the groups.

Table 9.

Daily interaction in different languages in percentage (StDev in brackets).

The results demonstrate that the participants report the highest use of Ukrainian in their daily communication, followed by English. The use of Russian is limited. The results for the use of Ukrainian did not differ significantly across the groups (H =1.72 (N = 65, p = 0.18), nor did the outcomes for the use of Russian (H = 0.049 (1, N = 65), p = 0.82). Only the use of English differed across the two groups significantly (H = 4.08 (1, N = 65), p = 0.043), whereby younger participants use English more in their communication. A weak but significant correlation confirms the presence of a covariance between age and the use of English (rs = −0.27, p = 0.027). This finding logically follows from the above results: since older participants have a lower English proficiency, they communicate less in the language. Also, less socialization in the language outside of home and being out of the job market can explain less English use by the older group.

4.3.4. Difficulty in Learning English

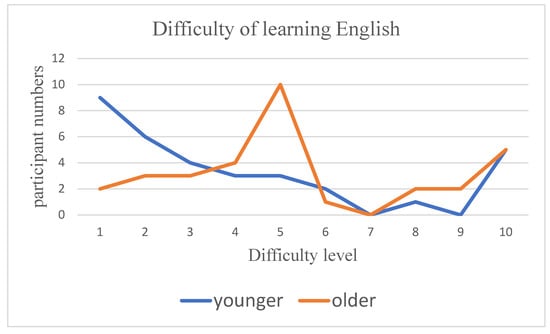

The participants were asked to rank the difficulty they experienced learning or improving English on a 10-point scale. The average difficulty for the younger group is 3.91 (StDev = 3.17), and for the older group, 5.41 (StDev = 2.81), i.e., the older group reports having more difficulty with English acquisition. The difference between the two groups’ responses is significant (H = 5.30 (1, N = 65), p = 0.021). Spearman correlation analysis also supports the covariance between age and the difficulty of learning English (rs = 0.34, p(2-tailed) = 0.005). The difference is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Difficulties of learning English by the two age groups.

4.3.5. Attitudes to Home Language Maintenance

We asked the participants to evaluate the importance of maintaining Ukrainian and Russian in Canada. Regarding their responses about maintenance of Ukrainian, the participants were highly positive about its importance (See Table 10), and there was no significant difference in responses across the age groups (H = 0.41 (1, N = 65, p = 0.52).

Table 10.

The participants’ responses to a question about the importance of maintaining Ukrainian in Canada.

By contrast, the respondents were rather negative about the maintenance of Russian in Canada, as shown in Table 11. In the Table, N/A relates to participants who did not speak Russian. They were excluded from the by-group comparison. As the table shows, the majority of respondents think that maintaining Russian is “not at all important”. The older generation is slightly more negative towards Russian maintenance, whereas the younger generation is more tolerant, providing more “neither important nor unimportant” neutral responses. However, this difference across the two groups is insignificant (H = 3.02 (1, N = 52), p = 0.08). On the other hand, there is a correlation for the whole dataset between participants’ age and their responses about the maintenance of Russian in Canada (rs = −0.32, p (2-tailed) = 0.020), i.e., older respondents produce more negative responses. Therefore, there is a need to explore this relationship more in future studies.

Table 11.

The participants’ responses to a question about the importance of maintaining Russian in Canada.

4.3.6. Learning or Enhancing Knowledge of Languages Since the Move to Canada

In response to a question about whether they started learning a new language or enhanced their knowledge of a language, the participants produced the responses summarized in Table 12. It shows number of participants who started learning a new language or enhanced the knowledge of a language in their repertoire.

Table 12.

Learning or enhancing the knowledge of languages in Canada.

Table 12 demonstrates that almost half of the participants (46%) focused on learning or enhancing their knowledge of English. A total of 10 participants (15%) worked on their Ukrainian either separately or in combination with English or French. French was only getting into the repertoire of 3 participants (5%). Remarkably, 12 participants (18%) found time to work on other languages. There is no significant difference in responses across the two age groups, and a chi-square calculation confirms the same: χ2 = 4.47, df = 5, p = 0.48.

5. Discussion

In this section, we will review the major findings and position them within the earlier research.

5.1. Home Languages Shift Among the Refugees from Ukraine Does Not Relate to Age

In this section, we will consider the outcomes of the study in regard to our RQ 1: What was the difference in home language use and attitudes of Ukrainian refugees by the two age groups (younger and older) before their move to Canada?

The results of the study demonstrate that in our sample, first, the events of 2014 did not cause a major shift in language use, but this is the time when changes started to appear. Bilingualism in Ukraine has been well documented in earlier studies on its complexity and regional variability (e.g., ; ). Our results align with studies showing gradual but uneven identity- and ideology-driven language change across Ukraine prior to the full-scale invasion (; ). Second, the changes in language use in Ukraine occurred mostly from 2022, whereby most participants report a change in language use and language attitudes: they started using more Ukrainian, less Russian, switched from Russian to Ukrainian, and the attitudes to Russian worsened. These results support a rapidly growing evidence describing post-2022 language transformations among Ukrainians both in Ukraine and abroad (e.g., ; ) and in other countries (; ). So far, only one study has reported a similar shift in the speech of Ukrainian immigrants in Canada who moved prior to 2022 ().

A new contribution our study is the finding that these changes do not appear to depend on the age of the participants, within the limitations of the study sample.

Third, an even more direct indication of language shift is the discontinuation of Russian since 2022, reported by 41.5% of the participants, which again is not associated with age. In sum, in the participant sample, the language shift in Ukraine started only from the war onset in 2022, and it affected all ages alike. The lack of effect can be explained by a small sample; however, in our data, the results of language shift across the age groups are so similar that it cannot be caused by chance, and a larger sample is unlikely to demonstrate any major difference across age groups in their attitudes.

These results are notable, since the traditional take on societal language shift claims that the change starts in the younger generation and then spreads to the more conservative older generation (; ). More recent findings suggest that in the new media contexts, youth are even more actively leading linguistic innovation (; ). Social media and platforms accelerate linguistic innovation (). However, in case of the language shift in Ukraine, age does not seem play a role in the shift, which could be explained either by the trauma of the Russian invasion which affected all alike—the young and the old, or by the impact of mass media which serves as a catalyst for the change in language attitudes as well (; ). Both possible explanations need to be verified in future research.

5.2. Language Use and Attitudes After Move to Canada

In this section, we discuss our findings with respect to RQ 2. “What is the difference in language use and attitudes of Ukrainian refugees by the two age groups (younger and older) after their move to Canada?” After moving to Canada, as expected, the participants report more English use (77%), but there is also some more Ukrainian language communication reported by 11% of the participants. Both age groups are strongly committed to the maintenance of Ukrainian. These results align with many studies, showing the importance of the dominant language and its use by immigrants, along with the benefits of maintaining the home language (e.g., ; ). An increase in negative attitudes toward Russian is identified by 5% only, probably because they were already negative before the move, and the priorities in the language attitudes shifted toward English learning. There is no relationship with age for the above variables.

Older age is associated with more negative attitudes toward Russian language maintenance in Canada. This came as a surprise because it could be expected that older individuals, some of whom grew up in the Soviet Union, would be more positive towards Russian maintenance. This result could potentially be explained by the stronger traumatic effect of the war on the older generation. Alternatively, it could be caused by the socialization of the older migrant individuals primarily within their families and local ethnic community (). It has been observed that the strong post-WWII wave of immigration from Ukraine to Canada was characterized by bringing “linguistic rejuvenation” and “aspirations to preserve the Ukrainian language” (; p. 19). The Ukrainian language serves both “practical/pragmatic and symbolic/ideological” functions on the prairies (; p. 53). Therefore, the older members of the Ukrainian community have a strong commitment to Ukrainian as a marker of their ethnicity and identity. Further research is needed to clarify this finding on a larger sample.

Very clear distinctions by age were observed in self-reported English language proficiency, whereby the younger participants were more proficient in English. While most of the participants report having improved their English proficiency at the time of the study (as compared to the time of their arrival in Canada), the younger group is doing better in English than the older group. The older group also reports having more difficulties with English language acquisition. These results fully conform with earlier findings that demonstrate the dependency of the English proficiency of immigrants on their age (e.g., ; ) and with the well-known younger age advantage in language acquisition (e.g., ).

The use of English in the refugees’ daily life also differs significantly by age, whereby younger participants use more English than their older peers, which may be related to them being more involved in the workforce or studies, as well as having a better English proficiency (as discussed above).

The results contribute to Linguistic equilibrium theory by showing how language attitudes may differ by age, and at the same time, how the emotional response to the drastic social change (a war in Ukraine initiated by the Russian government) can overrule the traditional generation spread of a shift and affect all generations alike.

The proficiency in French was negligible in the sample, which confirms earlier studies demonstrating that English is much more popular in Ukraine than other European languages.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

The study is limited to a relatively small group of Ukrainian refugees coming mostly from Western Canada. The results may differ by major immigrant residence locations in Canada. We relied on language proficiency as it was reported by participants, since we did not have an opportunity to evaluate participants’ proficiency in their home and host country’s languages.

6. Conclusions

Age showed no association with home language shift in Ukraine, which war refugees carried over with them to Canada. Across all age groups, the desire to maintain Ukrainian in Canada remained consistently strong. In contrast, age had a significant effect on English language outcomes: older participants reported lower proficiency both at the time of migration and at the time of the study, as well as greater perceived difficulty in learning English. Interest in maintaining Russian in Canada was also weaker among older respondents.

These findings contribute to a broader understanding of the distinct dynamics of language shift in Ukraine, highlighting patterns that diverge from other global cases of language change. The results also have several practical implications for immigrant- and refugee-serving organizations. Older refugees and immigrants would benefit from age-sensitive settlement and language-training supports. These could include smaller and slower-paced ESL classes, additional one-on-one tutoring, extended instructional timelines, and pedagogical approaches tailored to mature learners with limited prior exposure to English and a strong need to socialize beyond their immediate family. Settlement agencies may also consider integrating language learning with digital-literacy training, orientation sessions delivered in Ukrainian for older newcomers, and community-based conversation groups that reduce learning anxiety and isolation. Beyond ESL programming, the findings can inform social-service planning more broadly—particularly in designing culturally and linguistically responsive healthcare navigation, employment counselling, and community-integration initiatives for older refugees who face greater linguistic barriers.

Future research should further examine intergenerational socialization patterns among Ukrainian refugees, with attention to how interactions between younger and older family members shape language maintenance and shift in Canada. Additional studies could also explore how age-related linguistic challenges affect access to services, social networks, and long-term integration outcomes, and how community-based institutions can better support linguistic well-being across generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and V.M.; methodology: V.M. and Y.H.; software: Y.H. and V.M.; validation, V.M.; formal analysis V.M. and Y.H.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, V.M.; data curation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M.; visualization, V.M.; supervision, V.M.; project administration, V.M.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “The Language of War, Displacement, and of New Beginnings” grant, Global Innovation Fund, University of Saskatchewan. PI: Makarova, V (with S. Karpava (U Cyprus)—co-PI, and Li Zhi (UoS)—co-applicant). Received February 2, 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Behavioral Ethics Board of the University of Saskatchewan (code 4855, approved on 10 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alshihry, M. (2024). Heritage language maintenance among immigrant youth: Factors influencing proficiency and identity. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 15(2), 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A. N., Hyman, I., Holland, T., Beukeboom, C., Tong, C. E., Talavlikar, R., & Eagan, G. (2024). Medical interpreting services for refugees in Canada: Current state of practice and considerations in promoting this essential human right for all. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilaniuk, L. (2021). Contested tongues: Language politics in contemporary Ukraine (2nd ed.). Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boutmira, S. (2021). Older Syrian refugees’ experiences of language barriers in postmigration and (re)settlement context in Canada. International Journal of Health, Wellness & Society, 1(3), 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Carliner, G. (2000). The Language Ability of U.S. Immigrants: Assimilation and Cohort Effects. International Migration Review, 34(1), 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondrogianni, V., & Daskalaki, E. (2023). Heritage language use in the country of residence matters for language maintenance, but short visits to the homeland can boost heritage language outcomes. Frontiers in Language Sciences, 2, 1230408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R. B., Jr., deSouza, D. K., Bao, J., Lin, H., Sahbaz, S., Greder, K. A., Larzelere, R. E., Washburn, I. J., Leon-Cartagena, M., & Arredondo-Lopez, A. (2021). Shared language erosion: Rethinking immigrant family communication and impacts on youth development. Children, 8(4), 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong Gierveld, J., Van der Pas, S., & Keating, N. (2015). Loneliness of older immigrant groups in Canada: Effects of ethnic-cultural background. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 30, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenyvesti, A. (2005). Hungarian language contact outside Hungary. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, M. P., & Ivaniuk, Y. (2023). Ukrainian Canadian newcomers’ stories, hopes, and dreams: Adapting to a new multicultural reality. Mental Health: Global Challenges Journal, 6(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, J. E., Yeni-Komshian, G. H., & Liu, S. (1999). Age constraints on second-language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 41(1), 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F., Bermúdez-Margaretto, B., Shtyrov, Y., Abutalebi, J., Kreiner, H., Chitaya, T., Petrova, A., & Myachykov, A. (2021). First language attrition: What it is, what it isn’t, and what it can be. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 686388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y., Correia, S., Lee, Y.-W., Jin, Z., Rothman, J., & Rebuschat, P. (2025). Statistical learning of foreign language words in younger and older adults. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 28(3), 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormezano, D. (2022, May 30). Russian speakers in Ukraine reject the ‘language of the enemy’ by learning Ukrainian. France 24. Available online: https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20220530-russian-speakers-in-ukraine-reject-the-language-of-the-enemy-by-learning-ukrainian (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Grieve, J., Nini, A., & Guo, D. (2018). Mapping lexical innovation on American social media. Journal of English Linguistics, 46(4), 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halko-Addley, A., & Khanenko-Friesen, N. (2019). Language use and language attitude among Ukrainian Canadians on the prairies: An ethnographic analysis. East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies, 6(2), 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, G., & Palinska, O. (2022). Restructuring in a mesolect: A Case study on the basis of the formal variation of the infinitive in Ukrainian–Russian Surzhyk. Cognitive Studies (Warsaw), 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J. (2013). An introduction to sociolinguistics (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huot, S., Cao, A., Kim, J., Shajari, M., & Zimonjic, T. (2018). The power of language: Exploring the relationship between linguistic capital and occupation for immigrants to Canada. Journal of Occupational Science, 25(4), 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation. (2023). National culture and language in Ukraine: Changes in public opinion after a year of the full-scale war. Available online: https://dif.org.ua/en/article/national-culture-and-language-in-ukraine-changes-in-public-opinion-after-a-year-of-the-full-scale-war (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. (2024, July 26). Canada–Ukraine authorization for emergency travel: Key figures. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/ukraine-measures/key-figures.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Inan, Ş., & Harris, Y. R. (2025). Beyond the home: Rethinking heritage language maintenance as a collective responsibility. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1616510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasemi, A., & Gottardo, A. (2023). Second language acquisition and acculturation: Similarities and differences between immigrants and refugees. Frontiers in Communication, 8, 1159026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G., Aaronson, D., & Wu, Y. H. (2002). Long-term language attainment of bilingual immigrants: Predictive variables and language group differences. Applied Psycholinguistics, 23(4), 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlenberger, J., Buber-Ennser, I., Pędziwiatr, K., Rengs, B., Setz, I., Brzozowski, J., Riederer, B., Tarasiuk, O., & Pronizius, E. (2023). High self-selection of Ukrainian refugees into Europe: Evidence from Kraków and Vienna. PLoS ONE, 18(12), e0279783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kudriavtseva, N. (2023). Ukrainian language revitalisation online: Targeting Ukraine’s Russian speakers. In R.-L. Valijärvi, & L. Kahn (Eds.), Teaching and learning resources for endangered languages (pp. 203–223). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyk, V. (2023). Ukrainians now (say that they) speak predominantly Ukrainian. Ukrainian Analytical Digest, 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunyova, T., Lanvers, U., & Zelik, O. (2024). Bill 7633 on the restriction of the use of Russian text sources in Ukrainian research and education: Analysing language policy in times of war. Language Policy, 24, 109–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, V., & Morozovskaia, U. (2023). The linguistic odyssey of Russian-speaking immigrants in Canada. International Journal of Bilingualism, 27(6), 885–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveieva, N. (2018). Функціoнування білінгвізму та диглoсії у стoлиці України. Мoва: Класичне—Мoдерне—Пoстмoдерне, 4, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaie, R. (2020). Language proficiency and sociocultural integration of Canadian newcomers. Applied Psycholinguistics, 41(6), 1437–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawyn, S. J., Gjokaj, L., Agbényiga, D. L., & Grace, B. (2012). Linguistic isolation, social capital, and immigrant belonging. Sociological Forum, 27(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedashkivska, A. (2018). Identity in interaction: Language practices and attitudes of the newest Ukrainian diaspora in Canada. East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies, 5(2), 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedashkivska, A., & Makarova, V. (2025). Navigating languages at the time of war: First-generation immigrants from Ukraine in Canada. Heritage Language Journal. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Pchelintseva, O. (2023). War, language and culture: Changes in cultural and linguistic attitudes in education and culture in central Ukraine after February 24, 2022. Zeitschrift für Slawistik, 68(3), 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racek, D., Davidson, B. I., Thurner, P. W., Zhu, X. X., & Kauermann, G. (2024). The Russian war in Ukraine increased Ukrainian language use on social media. Communications Psychology, 2(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riederer, B., Buber-Ennser, I., Setz, I., Kohlenberger, J., & Rengs, B. (2025). Attitudes of Ukrainian refugees in Austria: Gender roles, democracy, and confidence in international institutions. Genus, 81(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roels, L., De Latte, F., & Enghels, R. (2021). Monitoring 21st-century real-time language change in Spanish youth speech. Languages, 6(4), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchuk-Kliuzheva, O. (2024). Forced migration and family language policy: The Ukrainian experience of language. Cognitive Studies, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. (2014). Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?CLV=1&CPV=8.1&CST=01010001&CVD=152866&Function=getVD&MLV=3&TVD=152865&adm=0&dis=0&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Statistics Canada 1. (2021). Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026b-eng.htm (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Statistics Canada 2. (2021). Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/250122/t001b-eng.htm (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Stevens, G. (1999). Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Language in Society, 28(4), 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2016). So sick or so cool? The language of youth on the internet. Language in Society, 45(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranenko, O. (2023). Russia-Ukraine war and the Ukrainian language (preliminary observations). II. Movoznavstvo, 331(4), 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. (2021). Ukrainian census. Available online: https://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). (2023). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2022 [Data summary, Syrian refugees]. UNHCR. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). (2025, February). Ukraine emergency statistics. UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/operational/situations/ukraine-situation (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Urbanavičė, R., El Arab, R. A., Hendrixson, V., Austys, D., Jakavonytė-Akstinienė, A., Skvarčevskaja, M., & Istomina, N. (2024). Experiences and challenges of refugees from Ukraine in accessing healthcare and social services during their integration in Lithuania. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1411738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warditz, V., & Meir, N. (2024). Ukrainian–Russian bilingualism in the war-affected migrant and refugee communities in Austria and Germany: A survey-based study on language attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1364112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylegala, A., & Polese, A. (2020). Language and identity in Ukraine before the 2022 invasion. Nations and Nationalism, 26(4), 1024–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah, N. T. (2025). The relationship between heritage language use, anxiety, intragroup marginalization, and somatization among U.S. Immigrants. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).