Abstract

Two theories that align with and support Usage-based approaches to language acquisition are Functionalism, which motivates the communicative functions of form-meaning connections produced by grammatical phenomena, and Connectionism, which provides a biologically-plausible framework for understanding language processes. An essential part of the learning process for second language (L2) learners is to understand how the target language differs in the ways it represents similar functionality, as well as functions not represented in learners’ first languages (L1s). In some cases, communicative functions served by the L1(s) are mirrored by similar-enough processes in the L2, so that the L1 processes can be utilized by the L2 system by entrenched L1 pathways. However, other communicative functions must develop their own processing pathways to accommodate differing L2 structures, because certain grammatical features allow for, or force particular ways of processing information. If the L2 learner does not notice and adopt the L2 processes needed for distinct linguistic structures, L1 processes connected to similar meanings will continue to be utilized. As a case in point, this paper outlines why L1 English learners of German as an L2 must change the ways they process syntactic role assignment away from syntactic cues towards ones embedded in morphology and morphosyntax. The goal of this paper is to explain how Functional and Connectionist theories, housed within a larger Usage-Based understanding of Second Language Acquisition, can account for frequently unsuccessfully or only partially acquired L2 German case marking, and why instructional interventions like Concept-Based Language Instruction and Processing Instruction all produce uptake of L2 German case marking to varying degrees.

1. Introduction

Two important theories that align with and support Usage-based approaches to language acquisition are Functionalism and Connections. On the one hand, Functionalism describes the communicative functions of form-meaning connections represented by grammatical phenomena, their communicative motivation, and the ways in which they emerge. On the other hand, Connectionism provides a biologically-plausible framework for understanding language processes as interconnected relations across linguistic phenomena. From a Functionalist perspective (e.g., ; ), grammar exists to create meanings that are relevant and useful for its speakers. An essential part of the learning process for second language (L2) learners is to understand how the target language (TL) differs in the ways it creates similar functionality. Underlying these communicative functions is a neural basis for cognition that can be represented by Connectionist models (e.g., ; ; ). Connectionist models can represent how the processing pathways utilized by these form-function mappings develop and entrench over time via updatable weights between nodes. In some cases, certain communicative functions served by the first language (L1) or languages are mirrored by similar-enough processes in the L2, so that the L1 processes can be utilized by the L2 system, basically overlaying entrenched L1 pathways. For the case of L1 English learners of German as an L2, this could be something like the use of modal verbs. However, other communicative functions, like thematicization and focus, which will be discussed in further detail in this paper, must develop their own processing pathways to accommodate differing L2 structures, because certain grammatical features allow for, or force, particular ways of processing information (). If the L2 learner does not notice and adopt the L2 processes needed for distinct linguistic structures, those of the L1 connected to similar meanings will continue to be utilized. By doing so, the functions encoded in the L2 will neither be processed appropriately, nor will the L2 learner be able to reproduce those functions in meaningful ways for their TL interlocutors. Thus, the relevance of noticing form-function relationships impacts L2 processing directly, as forcing learners into new processing patterns can help them establish appropriate L2 pathways for processing L2 grammar in appropriate ways.

As a focal case, I analyze how L1 English learners of German as an L2 must adapt how they process syntactic role assignment, specifically moving from a syntactically-realized noun-order system to one in which a morphosyntactic application related to article, adjective, and noun forms frequently dictates subjects and objects in utterances. In German, the complex case-gender-number agreement system plays an important functional role of enabling topicalization or thematicization that cannot be done in other languages, like English, which employ (almost solely) syntactic information to assign syntactic roles. German speakers are enabled by the case-marking system to vary word order, and the fact that German speakers must pay attention to morphosyntactic forms acts as a feedback loop from the case-marking system’s function in assigning syntactic roles. In this way, German speakers are continually forced to process case-morphology to correctly interpret syntactic roles. However, German does make use of Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order, which means that L1 English speakers learning German can—and frequently do—make parasitic use of their L1 processes pathways when processing L2 German. From a connectionist account, learners who rely on L1 pathways disregard valuable L2 grammatical components which would allow them to construct an appropriate processing model for German syntactic role disambiguation, leading to errorful interpretation and application of grammatical gender, case, and number agreement. This is a common error for L1 English learners of German as an L2, because when students encounter an accusative or dative object as the first noun, they assign it a subject role based on its syntactic position, rather than the morphological information indicating its non-subject role. For a German speaker, a sentence that begins with “Der Frau…” (“The-DAT woman…”) is indicative that the subject will come later, but learners of German often assume that woman is the subject. The goal of this paper is to explain how Functional and Connectionist theories, housed within a larger Usage-Based understanding of Second Language Acquisition, can account for frequently unsuccessfully or only partially acquired L2 German case marking, and why instructional interventions, like Concept-Based Language Instruction and Processing Instruction, all produce uptake of L2 German case marking to varying degrees.

2. Functionalism as Motivational Foundation for an L2 Usage-Based Paradigm

Functionalism, as defined by (, as cited in ) takes the position that “the forms of natural languages are created, governed, constrained, acquired and used in the service of communicative functions” (p. 137). Within a Usage-based theory of language, Functionalism provides the motivational foundation needed to understand the impetus behind human communication. This motivational foundation is essential to a Usage-based theory of language because it provides an alternative to Generative Linguistics’ Language Acquisition Device (and the belief that language is an instinct ()). From a functionalist perspective, humans’ desire (or instinct, if you like) to communicate with one another can suffice as the catalyst for linguistic communication. Because of our species’ capacity to process complex, symbolic information, the result has been a linguistic system that operates across multiple levels of acoustic and visual information, resulting in a variety of human languages that operate within the same biological constraints.

In the continued refinement and specification of speakers’ needs over time, we can find the dynamic and historical processes that have differentiated various linguistic forms within languages to serve these purposes, or functions (see ). As a new communicative need arises, speakers adapt the linguistic systems that enable communication to fill the gap and these new forms take their place not in isolation from other forms but rather gaining meaning in contrast to and connection with previously established forms. In some instances, novel words or morphemes are created, especially in society’s growing need to keep up with technological advancements. For example, Google, once a search-engine company name, is now readily used as a verb (to google) indicating an internet search, regardless of whether one is actually using Google’s service to perform the search. However, humans are not confined to lexemic creativity in their pursuit of meeting new communicative needs and work within the affordances and constraints of all their linguistic resources to enable new form-function mappings (). Over time, this has led to languages finding different linguistic solutions to similar communicative problems. For example, speakers of all languages have a need to express time. In some cases, like Mandarin, this is done primarily through individual lexemes but is not marked obligatorily. In other cases, like English, German, and French, the marking of time is often done obligatorily through morphology on the verb and can be supplemented optionally through individual lexemes.

For L2 learners, this motivational basis for communication is no longer rooted in the development of their L1(s); they already have a well-enough-established linguistic system for communication. Rather, the communicative functions that an individual can express serve as the foundation upon which a new linguistic system (or systems) is layered. The underlying motivation for the linguistic system, the need to communicate with other speakers, remains the same, but the process for acquiring the necessary forms to complete these functions is complicated, as they build upon an understanding of linguistic form-function mappings from their already acquired linguistic system. Learners need to become aware of discrepancies between the old and new systems in order to learn the target language (see ).

Here we must be cautious, as we cannot assume that the underlying linguistic system for an L2 learner is a single L1. Most people in the world are multilingual, and as such, this should be the basis for our understanding of L2 learning (). A Usage-based approach to understanding L1 acknowledges that the L1 system arises out of use of these multiple languages. It does, however, prompt us to ask how functions, which may be realized in different ways by already established L1s, may be transferred to the L2, and what aspects may impact the initial learning state of the L2 vis-à-vis the processing pathways utilized by the speaker, e.g., the speaker’s perception of which L1 is more similar to the L2, or processing and production pathways that are more or less like one of the L1s than the other(s).

For the L2 learner, regardless of the number of L1s, functionality is a two-fold process of keeping entrenched ways of processing and producing appropriate meanings that overlap with the current linguistic system and developing new ways to do so for functions that are represented in linguistically distinct ways. As () outlines in her functional approach for L2 learning, “The concept-oriented approach begins with a learner’s need to express a certain concept, such as time, space, reference, or modality, or a meaning within a larger concept (such as past or future time, within the more general concept of time), and investigates the means that a learner uses to express that concept,” (p. 55). Thus, the learner must undertake an exploratory process of analyzing prior form-function mappings and contrasting those with the target language’s grammatical and lexical mechanics for those same semantic meanings. Herein lies the major problem for L2 learners: How do they make the distinction between what to keep and what to throw out in favor of alternative form-meaning connections? The wholesale adoption of existing L1 processes could be viewed as the initial state of L2 language learning, recognizing other generalized linguistic, and even non-linguistic, processing mechanisms may be at play. Only through mismatches between speakers’ current linguistic system and that of the target language do changes in the system arise. These mismatches might occur through interactions with other speakers of the target language, or through other encounters with the language, including classroom instruction. Of importance here is that these mismatches between L1/L2 functions and forms are recognized by L2 learners if they are to develop.

3. Connectionism as a Biologically Plausible Mechanism for an L2 Usage-Based Paradigm

As a species, we have been endowed with the capacity for complex, symbolic processing. Through cultural and historical processes this has resulted in the languages we use today, and thus, must be grounded in these endowed capacities. Useful explanations for this come from emergentist accounts of language (; ), which explain how lower-level processes and forms can result in sometimes surprising higher-level processes and forms (). Connectionism has been highly successful at mimicking the appropriate type of interconnectivity we see underlying neural networks in the brain and nervous system generally and can be used to model learning and production processes exhibited in human language (e.g., ).

Within Connectionist modelling, competition between cues has been shown to explain the differences in learning observed in both computational models and language behaviors in humans at all developmental levels (). Within the Competition Model framework (CM) (), cues are seen as information that helps speakers determine the relationship between forms and meaning. These cues compete for activation and their strengths or cue-weights are always intertwined as part of their relationship to other cues. The weight or strength of a particular cue is developed in two ways. First is by its validity, which consists of its availability in the input and its reliability for predicting the appropriate form-meaning connection. And second, by its relative validity to other competing cues. Much of the early work on the CM focused on child-language learning, although from its conception, it was always boldly intended as a way to capture the entirety of language learning, use, and attrition in both comprehension and production.

For SLA specifically, competition within connectionist models can explain a wide range of L2 acquisitional and use patterns (). This includes phenomena such as U-shaped learning, i.e., the pattern of rote learning of irregular forms replaced by overgeneralization of regular patterns onto irregular lexemes and eventual return to correct irregular forms (). For German, U-shaped learning can take many forms. In on specific example, it is visible on the overgeneralization of newly integrated regular verb past-tense marking patterns onto previously known irregular past-tense verb forms and then an eventual return to correct irregular verb production (). Other patterns that can be explained with connectionist patterns include interlanguage transfer, i.e., the adoption of L1 cues and cue-weights in L2 language processes as well as the opposite, where learned L2 cues and cue-weights may affect L1 processes (), and restructuring, i.e., changes to the functions assigned to already learned forms and their integrations of new forms and functions into the linguistic system (; ). The Unified Competition Model (UCM) () specifically shows how both L1 and L2 acquisition and learning result from the same fundamental principles of cue competition and further takes into account the impacts of transfer between linguistic codes. The UCM covers cue competition in the different “arenas” in which competition can play out, including phonology, the lexicon, morpho-syntax, and conceptual knowledge. As () argues, “forms compete to express underlying intentions or functions” (p. 71) in production, but also for interpreting intentions and functions in comprehension. The UCM also considers the effects of chunking, or the size of cues, grammatical forms, and lexical bundles, as well as the necessary storage of these cues for future activation. And finally, the UCM also implicates the importance of code activation, i.e., which linguistic units of the entire linguistic system should be activated based on the language being spoken. In this model, a particular code does not necessarily distinguish between two separate linguistic subsystems, as more than one language may utilize the same parts of the linguistic subsystem, which allows us to understand the mechanism behind transfer effects, as well as the need in L2 learning to build differentiations between linguistic codes where necessary.

By viewing language as an embedded capacity, rather than a modular unit within the brain, the interconnectivity and influence of all brain regions and functional capacities can be accounted for (). Within this framework, Usage-based linguistics offers a window into how language use impacts the organization of these emergent, connected linguistic systems (). For example, we can see the influence of awareness and attentional resources for noticing L2 features in eye movements (), the embodiment of cognitive processes on L2 processing and production (; ), and the impact of language beliefs, values, and motivation on L2 engagement and learning (). Under a broad, Usage-based framework, Connectionism emphasizes the viable hardware, the biological, interconnected system of the brain, on which observed psycholinguistic phenomena like U-shaped learning, transfer, and restructuring operate.

4. A Functional, Connectionist Account of L2 German Case Acquisition

When a new communicative need arises, there are a number of linguistic ways for speakers to meet it. For example, adding emphasis to a particular noun-phrase is a common rhetorical function that cannot be enacted through the creation of novel words, as it is the need to draw attention to an already established word or phrase. In English, emphasis is often achieved through suprasegmental phonological means, i.e., adding stress to a word that would normally not receive it in a similar, unmarked utterance (). When this is not possible in English, for example, in writing, textual enhancements like bolding, italics, or underlining can be used, or left-dislocation (i.e., topicalization) (“It says you can do that in the rules” vs. “In the rules, it says you can do that”) (; ). For the most part, English speakers accomplish emphasis without disturbing SVO word order, as it is the primary cue required to correctly interpret syntactic roles. Other cues, like animacy or context, can assist in syntactic role assignment, but the predominance of first-noun-as-subject in English will almost always be used in ambiguous cases under these linguistic constraints () (see () for other factors that can also play a role in disambiguation and either accepting or overriding this First Noun Principle).

However, for German, word order is much more flexible and topicalization can easily be achieved. For main clauses in German, the conjugated verb is located in the second position and the subject is (almost always) located in either the first (SVX) or third (XVS) position. The reason for this flexibility is a direct result of the case-marking system in German. German speakers do not rely on syntactic position to disambiguate the subject from other potential candidates, but rather nominative morphology for subjects that results from gender-case-number marking agreement patterns. For German speakers, then, if a noun located before the verb is marked as the subject, it is readily identified as such. In other cases, where the morphology indicates that the first noun is not a subject, the speaker must wait for a noun phrase that carries the appropriate subject morphology. In German, it is common for non-subject-marked nouns to appear in the first position because of discursive features like definiteness and newness ().

To illustrate the issue this creates for L1 English L2 German learners, I use the following three sentences:

| 1. | The dog is chasing the cat. | |||||

| 2. | Der | Hund | jagt | der | Katze | nach. |

| The.NOM | dog | chases | the.DAT | cat | after | |

| ‘The dog is chasing the cat.’ | ||||||

| 3. | Dem | Hund | jagt | die | Katze | nach. |

| The.DAT | dog | chases | the.NOM | cat | after | |

| ‘The cat is chasing the dog.’ | ||||||

Item 1 and item 2 above are equivalent translations of each other, both including the phrase the dog as the first noun and both marking the dog as the subject: In item 1 as a result of English’s syntactic cue for subject assignment, and in item 2 as a result of German’s case morphology, where der matches the singular number feature and masculine grammatical gender feature of dog, combined with the nominative form of the word the. For the L1 English L2 German learner, item 2 presents no problems with correctly interpreting Hund as the subject of the sentence through parasitic use of L1 subject role assignment. In other words, the learner is able to correctly assign Hund the subject role through the adoption of the L1 English first-noun-as-subject principle. This first-noun-as-subject principle is not necessarily incorrect as a syntactic-role disambiguation strategy in German either and is sometimes necessary in cases where case marking morphology is ambiguous and context does not provide any further cues. However, this produces a genuine problem for the learner’s continued development with German. First, correct interpretation of the subject via the incorrect cue strengthens an improper L2 processing route. The learner, having encountered no issues utilizing the L1 pathway for subject role assignment, will be more apt to process sentences this way in the future, leading to confusion and incorrect role assignment when they encounter sentences like item 3. Second, it allows the learner to disregard the case, number, and gender information espoused in the definite article der and avoid processing these forms for meaning; essentially chucking out the “grist for the mill” that () have shown to be so important for learning, especially statistical learning that is necessary for the formation of new, implicit L2 processing routes.

Turning to item 3, the subject of the sentence is Katze, not Hund, but is not the first noun encountered in the sentence. The nominative form of the masculine singular definite article der before Hund from items 1 and 2 is replaced by the dative form dem. Likewise, the dative form of the feminine singular dative article der before Katze is replaced by the nominative form die. If L1 English L2 German learners rely on L1 cues and use L1 processing pathways, while disregarding case marking in the process, they will falsely interpret Hund as the subject and Katze as the object. And they will be led down this incorrect pathway from the start, as they build the sentence linearly. Contrarily, the appropriate German processing pathway would utilize the dative marking on the definite article on the first noun to perceive the following noun as distinctively not the subject, leaving the final resolution of the subject open until an appropriately marked nominative construction is found. For this reason, it is vital that L1 English L2 German learners are exposed early and often to non-SVO word order and are positioned to be forced to process non-SVO sentences for the appropriate syntactic role. Effective instructional approaches to force appropriate processing of non-SVO sentences in German have been devised, from various theoretical perspectives, such as Input Processing () and Concept-Based Language Instruction (). Regardless of theoretical background, all of these approaches recognize the need to enable the learner to break with the L1 English processing route and construct an appropriate one for German.

Switching from input and processing to output and production, the problem for L2 users is exacerbated by a lack of knowledge of case function. While one could force learners, from a purely Connectionist perspective, to at least process non-SVO word order in German, learners are unlikely to utilize non-SVO constructions in their own language use. Because SVO word order is a viable construction in German and case marking operations are difficult to process for L1 English speakers, especially initially, there is compelling evidence for L1 English L2 German learners to prefer SVO constructions (, ; ; ). In many instances, without external pressure to produce XVS or OVS word order constructions, these learners deepen the sub-optimal, entrenched pathway and disregard for case information via their parasitic use of L1 processing routes. Frequent production errors include English-style fronting, where a prepositional phrase is placed at the beginning of a clause, followed by a comma (in written production), and then a restart of the sentence in SVO word order. For example, the English sentence:

should be produced in an XVS order in German as follows:

However, L1 English L2 German learners frequently produce sentences in XSV, like

Even in cases where learners are able to process German sentences in XVS order, they often fail to reproduce this syntax, revealing a continued use of L1 production routes.

| 4. | Today, I’m going home. |

| 5. | Heute | gehe | ich | nach | Hause. |

| today | go | I.NOM | to | home |

| 6. | *Heute, | ich | gehe | nach | Hause. |

| today | I.NOM | go | to | home |

In addition, most L2 learners are exposed to simplistic sentences and unlike L1 learners, do not frequently participate in rich target language environments where this word-order variability is displayed in pragmatic, contextualized ways. This means that without instructional intervention, the transfer of the L1 pathway will stabilize and entrench as the preferred L2 pathway, causing confusion when learners encounter more complex language that makes heavier use of XVS and OVS constructions, as well as requiring more effort to get themselves out of these inappropriate processing routines. While only OVS constructions indicate case on the object, other XVS constructions, like time adverbials and prepositional phrases, force learners to process syntactic patterns where the subject appears after the verb, which contrasts with English sentence processing where the subject always appears before the verb. Even when learners are exposed to XVS and OVS structures, the validity of SVO word order in German makes the uptake of case marking difficult, in addition to the fact that English speakers are not used to processing articles for information beyond definiteness and number (see ), although other non-L1 specific processes that prefer certain syntactic acquisitional orders may also be at play (see ).

One reason for L1 English L2 German learners’ continued problems with non-SVO structures is a lack of understanding of the functionality that case marking enables vis-à-vis flexible word order. This is especially true for OVS structures where other cues that could help resolve syntactic roles, like animacy, are ambiguous. As mentioned earlier in this essay, the existence and continued relevance of case marking in German is because of a reciprocal relationship with its functional purposes. The variable word order in German enables speakers to have more control over information structure. They can highlight different pieces of information through topicalization like in item 4. They can front answers to interlocutors’ questions like in item 5. And they can build cohesion across clauses and discourse, like in item 6 (from ’s () Der Schimmelreiter, translation by James Wright () titled The Rider on the White Horse).

| 7. | Den | hab’ | ich | nie | gesehen. |

| him.ACC | have | I.NOM | never | seen | |

| ‘I’ve never seen him.’ | |||||

| 8. | Person A: | Wohin | geht | ihr? | ||

| where-to | go | you.NOM.PL | ||||

| ‘Where y’all going?’ | ||||||

| Person B: | Ins | Theater | gehen | wir. | ||

| in the.ACC | theater | go | we.NOM | |||

| ‘We’re going to the theater.’ | ||||||

| 9. | …das war der Großknecht Ole Peters, ein tüchtiger Arbeiter und ein maulfertiger Geselle. Ihm war der träge, aber dumme und stämmige Kleinknecht von vorhin besser nach seinem Sinn gewesen… |

| Ole Peters.NOM (…) ihm.DAT (antecedent = Ole Peters) | |

| “… that was Ole Peters, the foreman. He was a competent workman, but he talked too much. The previous servant boy had been more to his liking…” |

In items 4, 5, and 6, the functional aspects of German word order that are enabled through case marking are clearly visible. It gives German speakers more control over sequential information structure to fulfill communicative needs. L1 English speakers must learn to pay attention to case cues if they hope to process these meanings and gain control of production of these functions themselves.

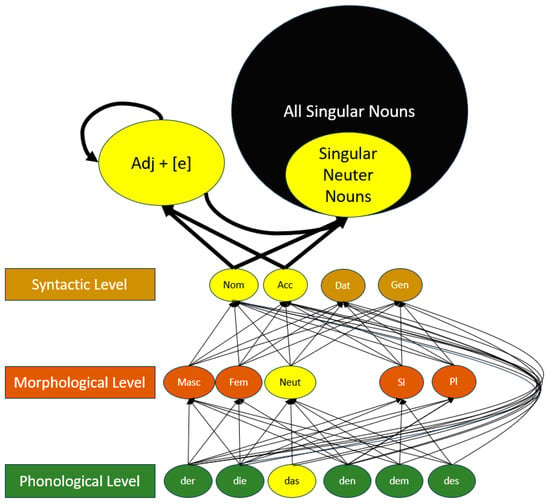

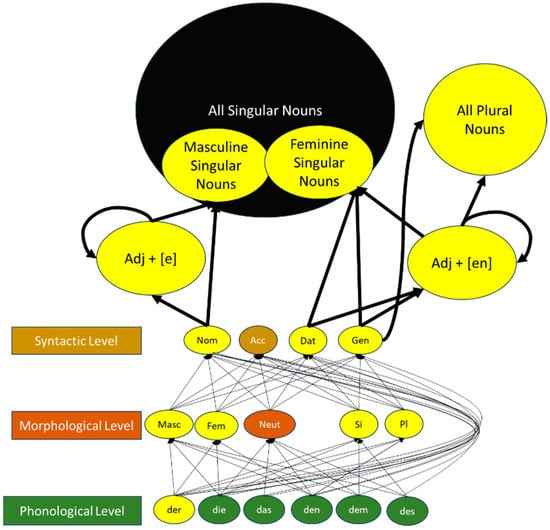

There is a secondary function beyond information structure that case marking plays for German speakers as well, and it has to do with processing efficiency. The case, gender, and number marking visible on determiners (as well as attributive adjectives and some noun forms) enhances predictive processing by delimiting the pool of viable nouns, alongside other contextual cues. In English, any noun can come after the word the, but in German, the morphology on definite articles restricts the pool of possible nouns, allowing for higher predictive accuracy and lower processing costs (for more on the role of morphology in aiding processing, see () and (), and specifically for grammatical gender, see ()). In Figure 1 and Figure 2 below, I present two connectionist models, one for the definite article das and one for the definite article der. The models show all possible case, gender, and number combinations for the definite article and the possible noun pools, with the definite article in question, its relative morphological components, and compliant adjective and noun pools highlighted in yellow.

Figure 1.

Connectionist model for predictive processing through German definite article das.

Figure 2.

Connectionist model for predictive processing through German definite article der.

In Figure 1, it is clear that the determiner das is only associated with the neuter grammatical gender, only with singular nouns, and only with nominative and accusative cases. In contrast, Figure 2 shows that the determiner der can be associated with masculine and feminine and plural nouns depending in the case, making ease of processing and syntactic role disambiguation nigh impossible without knowledge of the noun gender or plural forms. This increase in processing effort is only worth the payout of easier prediction if the case-number-gender paradigm is easily accessible, especially for oral production and comprehension. For L2 German learners, the ease of processing and predictive opportunities that arise through case, gender, and number information only arise when pathways have formed to process that information. Continued parasitic use of L1 English pathways that disregard and fail to track this crucial information results in more effortful processing.

5. Explaining Effective L2 Instructional Methods from a Usage-Based Perspective

A Usage-based approach to language learning that incorporates Functionalist and Connectionist perspectives has extraordinary explanatory potential for why and how various L2 teaching methodologies are (more and less) successful. In this section, I compare findings from two different teaching methodologies, Processing Instruction (PI) and Concept-Based Language Instruction (C-BLI), which were devised according to two very different approaches to second language learning, Input Processing Theory and Sociocultural Theory, respectively.

According to (), “PI is actually a type of focus on form or better yet, a pedagogical intervention. As such it is not a method with an underlying approach but instead an intervention that can be used by any communicative approach that seeks a supplemental or periodic focus on the formal features of language,” (p. 166). From this perspective, PI should be applicable under any number of language theories.1 However, in the same paper, () declares that “Under PI, acquisition consists of three necessary ingredients: input; Universal Grammar (UG) and internal mental architecture; and processing mechanisms that mediate between input and UG/internal architecture,” (p. 167). Here, there is a sharp contrast to the theory-neutral stance of its applicability and a declaration of the need for UG to explain the learning mechanism. The major challenge here is that the definition of UG has changed significantly over the past decades (see () for an overview), and our understanding of human cognition has developed to handle the difficulties that UG hoped to solve in more empirical ways.

Despite the UG foundations of VanPatten’s PI, it has been shown to be effective. Other researchers take up the more theory-neutral side of PI and have investigated it along lines that explore PIs connection to other theories of language, such as (), who describes PI as having two “core tenets […] (a) instructional interventions should promote meaningful or functional aspects of targeted grammatical forms by making them essential to the task, and (b) the task should push learners to overcome default (or nonoptimal) processing strategies” (p. 1432). In German, multiple studies have shown that a combination of PI, along with explicit and implicit instruction, can aid in L2 learners’ processing of German case morphology (see , ; ). The theoretical underpinnings of PI are rooted in Input Processing and align with Interactionist models (e.g., ) and Processability Theory (e.g., ). And while () categorizes each of these three theories as “psycholinguistic”, they are ambivalent in their direct connection to underlying, biologically plausible mechanisms for the learning that occurs in these studies.

Coming from the other side of the SLA theory spectrum, C-BLI focuses on the use of conscious, conceptual resources available to adult L2 learners to frame L2 features in a way that eases functional understanding and use (). For German case marking, this method has been explored to show how the functional concept of topicalization can drive the processing and production of non-SVO structures (see ; ). Similar to PI, this approach also highlights form-meaning/function mappings but does so from a very different theoretical perspective and uses higher-order thinking to connect conceptually relevant information (e.g., SCOBAS or metaphors) to highlight learner agency over language choice, in so doing creating a motivator to raise awareness and eventual internalization of conceptual schemas. Sociocultural Theory in SLA (see ), while historically distinct from the approaches underpinning PI described above, also distances itself to some degree from underlying, biologically plausible mechanisms for L2 learning, and does not necessarily disregard, but does not attend significantly enough to, the properties we see in implicit and statistical learning that are still required for L2 development. The procedures involved in C-BLI are highly effective at helping students understand form-meaning connections, notice forms, apply relevant higher-order thinking, and ultimately apply this information, but they do not help us understand the route between this explicit information and automatization and/or proceduralization of this knowledge into implicit knowledge.

It is here, in this space, that Usage-based approaches, incorporating Functionalism and Connectionism, can bridge the gap between the positive findings coming from disparate theories in SLA and offer a unifying account. And while some recent studies have argued for the integration of C-BLI and Sociocultural/Sociolinguistic (e.g., ; ; ) as well as PI (e.g., , ; ) approaches to SLA with Usage-based theories, further work is needed to articulate the ways in which these theories can be fully aligned. In both PI and C-BLI, functional aspects of language are highlighted, albeit approached from different ways and resulting in slightly different learning outcomes (). Functionality is foundational to Usage-based approaches, as it provides the motivation for linguistic forms and their propagation to fulfill communicative needs (see () for similar arguments), but also a framework to understand speaker agency and choice within a given context. In addition, Connectionist models provide a viable learning mechanism through which learning, processing, and production can all occur. This is true for both statistical learning of specific L2 forms, as can be modelled to exhibit similar patterns to L2 learning outcomes, like U-shaped learning, as well as to provide some explanation for the impact of explicit instruction and conscious knowledge. Usage-based linguistics, as an overarching umbrella for SLA, has significant explanatory power and provides falsifiable theories to test. For example, why do we see typical orders of acquisition for linguistic phenomena (), but are sometimes able to alter those orders through instruction (e.g., )? From a Usage-based perspective, we can make specific hypotheses about the form-function understanding of the learner, interlanguage, parasitic transfer of processes, cue validity and strength, all while maintaining the emergent and non-linear behaviors exhibited in learner data. More studies are needed that combine methods stemming from Functionalist and Connectionist approaches that integrate corpus and analytic methods, eye-tracking, and brain imaging, which can better unify the linguistic and paralinguistic behaviors we see in L2 learners and provide a richer understanding.

In this paper, I outlined how Functionalism and Connectionism are fundamental for explaining what we see in data provided through Usage-based approaches to SLA. For a Usage-based approach to SLA to be successful, researchers need to go beyond using it to describe what we see and link it to cognitively and socially grounded theories about why we see what we do. By integrating work on Functionalism and Connectionism, Usage-based approaches are strengthened in their explanatory capacity. There is still much work to converge multiple historical trajectories within SLA (), and this paper is limited in that it provides a theoretical overview of what to look for, but not empirical evidence. Further studies that focus on Usage-based approaches to SLA would benefit from keeping the motivational and mechanistic foundations provided by Functionalism and Connectionism in mind as they develop more innovative ways to combine data sources and speak more directly to the mechanisms, both cognitive and social, that give rise to the language behaviors we see in L2 learners. With a solid foundation of Functionalism and Connectionism, Usage-based theories of SLA provide a fruitful path forward to understanding the complex and frequently messy nature of second language learning and instruction.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | While VanPatten takes a UG-based approach, he does indicate in his earlier work that, “as I state in various publications, one need not take such a perspective to understand how PI might help language grow in the mind/brain,” (). |

References

- Atkinson, D. (2010). Extended, embodied cognition and second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 31(5), 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2018). Concept-oriented analysis: A reflection on one approach to studying interlanguage development. In A. Edmonds, & A. Gudmestad (Eds.), Critical reflections on data in second language acquisition (pp. 171–195). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2020). One functional approach to L2 acquisition: The concept-oriented approach. In B. VanPatten, G. D. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 40–62). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E., & MacWhinney, B. (1982). A functionalist approach to grammar. In E. Wanner, & L. Gleitman (Eds.), Language acquisition: The state of the art (pp. 173–218). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E., & MacWhinney, B. (1988). What is functionalism? In Papers and reports on child language development (Vol. 27, pp. 136–152). U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E., & MacWhinney, B. (1989). Functionalism and the competition model. In E. Bates, & B. MacWhinney (Eds.), The crosslinguistic study of sentence processing (pp. 73–112). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, H. (2009). Usage-based and emergentist approaches to language acquisition. Linguistics, 47(2), 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, J. L. (1998). A functionalist approach to grammar and its evolution. Evolution of Communication, 2(2), 249–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, C. A. (2009). The relationship between second language acquisition theory and computer-assisted language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 93(s1), 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M. H., & Chater, N. (1999). Toward a connectionist model of recursion in human linguistic performance. Cognitive Science, 23(2), 157–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, H. (1984). The acquisition of German word order: A test case for cognitive approaches to L2 development. In R. Andersen (Ed.), Second languages: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 219–242). Newbury House. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, C. (2008). Age effects on the process of L2 acquisition? Evidence from the acquisition of negation and finiteness in L2 German. Language Learning, 58(1), 117–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. (2015). Stimulation mapping of white matter tracts to study brain functional connectivity. Nature Reviews Neurology, 11(5), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, N. C., & Wulff, S. (2020). Usage-based approaches to L2 acquisition. In B. VanPatten, & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 63–82). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Elman, J. L. (2001). Connectionism and language acquisition. In M. Tomasello, & E. Bates (Eds.), Language development: The essential readings (pp. 295–306). Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, S. W. (2015). What counts as a developmental sequence? Exemplar-based L2 learning of English questions. Language Learning, 65, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrmann, I. (2016). Teaching the form-function mapping of German ‘prefield’ elements using Concept-Based Instruction. Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association, 4(1), 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenck-Mestre, C. (2005). Eye-movement recording as a tool for studying syntactic processing in a second language: A review of methodologies and experimental findings. Second Language Research, 21(2), 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R., Grainger, J., & Rastle, K. (2005). Current issues in morphological processing: An introduction. Language and Cognitive Processes, 20(1–2), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garello, S., Ferroni, F., Gallese, V., Ardizzi, M., & Cuccio, V. (2024). The role of embodied cognition in action language comprehension in L1 and L2. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, S. M. (1986). An interactionist approach to L2 sentence interpretation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 8(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, S. J., Wu, C. H., Hua, X., Dunn, M., Levinson, S. C., & Gray, R. D. (2017). Evolutionary dynamics of language systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(42), E8822–E8829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, F. (2024). On bilinguals and bilingualism. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, M. (2014). On system pressure competing with economic motivation. In B. MacWhinney, A. L. Malchukov, & E. A. Moravcsik (Eds.), Competing motivations in grammar and usage (pp. 197–208). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, N. (2023). The additive use of prosody and morphosyntax in L2 German. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(2), 348–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N. (2025). The effects of Processing Instruction on the acquisition and processing of grammatical gender in German. Language Teaching Research, 29(4), 1426–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., Culman, H., & VanPatten, B. (2009). More on the effects of explicit information in instructed SLA. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31(4), 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., Jackson, C. N., & DiMidio, J. (2017). The role of explicit instruction and prosodic cues in processing instruction. The Modern Language Journal, 101(2), 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, H. (2016). Learning (not) to predict: Grammatical gender processing in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 32(2), 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. N. (2007). The use and non-use of semantic information, word order, and case markings during comprehension by L2 learners of German. The Modern Language Journal, 91(3), 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. N. (2008). Processing strategies and the comprehension of sentence-level input by L2 learners of German. System, 36(3), 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M. (2017). What we gain by combining variationist and concept-oriented approaches: The case of acquiring Spanish future-time expression. Language Learning, 67(2), 461–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M. (2024). Restructuring in L2 Spanish future-time variation: The evolving roles of contextual sensitivity and individual variability in morphological development over time. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 8(1), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, K. (1994). Information structure and sentence form: Topic, focus, and the mental representations of discourse referents (Vol. 71). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Introducing sociocultural theory. Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, J. P., & Zhang, X. (2017). Concept-based language instruction. In The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 146–165). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. (1989). Competition and connectionism. In B. MacWhinney, & E. Bates (Eds.), The crosslinguistic study of sentence processing (pp. 423–457). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. (2005a). Extending the competition model. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, B. (2005b). The emergence of linguistic form in time. Connection Science, 17(3–4), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, B. (2006). Emergentism—Use often and with care. Applied Linguistics, 27(4), 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, B. (2018). A unified model of first and second language learning. In M. Hickmann, E. Veneziano, & H. Jisa (Eds.), Sources of variation in first language acquisition (pp. 287–312). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B., Bates, E., & Kliegl, R. (1984). Cue validity and sentence interpretation in English, German, and Italian. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23(2), 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, B., Leinbach, J., Taraban, R., & McDonald, J. (1989). Language learning: Cues or rules? Journal of Memory and Language, 28(3), 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondorf, B. (2014). Apparently competing motivations in morphosyntactic variation. In B. MacWhinney, A. L. Malchukov, & E. A. Moravcsik (Eds.), Competing motivations in grammar and usage (pp. 209–228). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nordquist, D., & Smith, K. A. (2018). Functionalist and usage-based approaches to the study of language. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, W., Lee, M., & Kwak, H. Y. (2009). Emergentism and second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie, & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), The new handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 69–88). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, M. (2021). Exploring the interface between individual difference variables and the knowledge of second language grammar. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Pienemann, M. (1998a). Developmental dynamics in L1 and L2 acquisition: Processability theory and generative entrenchment. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pienemann, M. (1998b). Language processing and second language development: Processability theory. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. W. Morrow and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett, K. (1998). Language acquisition and connectionism. Language and Cognitive Processes, 13(2–3), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, E. F. (2011). On the functions of left-dislocation in English discourse. In A. Kamio (Ed.), Directions in functional linguistics (pp. 117–144). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, T. (2014). Word order and case in the comprehension of L2 German by L1 English speakers. EuroSLA Yearbook, 14(1), 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N., & Mehlhorn, G. (2006). Focus on contrast and emphasis: Evidence from prosody. The Architecture of Focus, 82, 347–371. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D. E., & McClelland, J. L. (1986). On learning the past tenses of English verbs. In J. L. McClelland, D. E. Rumelhart, & The PDP Research Group (Eds.), Parallel distributed processing: Explorations in the microstructure of cognition. Volume 2: Psychological and biological models (pp. 216–271). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Y. (2018). Connectionism and second language acquisition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, T. (1888). Der schimmelreiter. Deutsche Rundschau, 55, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, T. (2009). The rider on the white horse (J. Wright, Trans.). New York Review Books. [Google Scholar]

- Trettenbrein, P. C. (2015). The “grammar” in Universal Grammar: A biolinguistic clarification. Questions and Answers in Linguistics, 2(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A. (2010). Usage-based approaches to language and their applications to second language learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R. A. (2011). Developing second language sociopragmatic knowledge through concept-based instruction: A microgenetic case study. Journal of pragmatics, 43(13), 3267–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R. A. (2019). Constructing a second language sociolinguistic repertoire: A sociocultural usage-based perspective. Applied Linguistics, 40(6), 871–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B. (2015). Foundations of processing instruction. IRAL: International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53(2), 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B. (2017). Processing instruction. In S. Loewen, & M. Sato (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 166–180). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B. (2020). Input processing in adult L2 acquisition. In B. VanPatten, G. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 105–127). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B., & Borst, S. (2012). The roles of explicit information and grammatical sensitivity in processing instruction: Nominative-accusative case marking and word order in German L2. Foreign Language Annals, 45(1), 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, D. R. (2020). The acquisition of German declension in additive and concept-based approaches to instruction via computer-based cognitive tutors. Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 11(1), 130–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, D. R., & van Compernolle, R. A. (2015). Teaching German declension as meaning: A concept-based approach. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 11(1), 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A., & Müller, K. (2004). Word order variation in German main clauses. A corpus analysis. In S. Hansen-Schirra, S. Oepen, & H. Uszkoreit (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Linguistically Interpreted Corpora (pp. 71–77). ACL Anthology. [Google Scholar]

- Zubin, D. A., & Koepcke, K. (1981). Gender: A less than arbitrary category. Chicago Linguistics Society, 17, 439–449. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).