Abstract

This study shows two parallelisms between (i) the acquisition process of English verb–particle constructions (VPCs) by children in the process of acquiring English as a native language (henceforth ENL children) and (ii) that of Japanese verb–verb compounds (VVCs) by children in the process of acquiring Japanese as a native language (henceforth JNL children) using the CHILDES database. First, both JNL and ENL children produce creative N–N compounds and complex predicates during the same period, in line with the proposal by Snyder that the Compounding Parameter (TCP) is set to positive for both Japanese and English languages. Second, particles or verbs which are used to represent the path of motion in English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are produced before the VPCs and VVCs they are used in because complex predicates are created by the combination of two or more constituents, such as verbs and particles. Thus, our findings corroborate the proposal that Japanese is a [+TCP] language and suggest that Japanese makes use of VVCs instead of VPCs. Furthermore, this parallelism observed among ENL and JNL children in the acquisition process of creative N–N compounds and VPCs/VVCs, respectively, suggests that English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are related expressions in a grammatical sense. This in turn implies that VPCs and VVCs are connected by more than their semantics; indeed, it implies that they are realizational variations of the same abstract linguistic structure.

1. Introduction

When humans verbalize events, there are differences in how verbalization occurs depending on the language used. For instance, a concept representing spatial or locational meaning is expressed as particles in English, as in John lifted the box up, while the same interpretation is obtained with verbs in Japanese, as in Tarō-ga hako-o mochi-age-ta (Taro-NOM box-ACC lift-raise-PST) ‘Taro lifted the box up’.1 In this way, English uses a verb–particle construction to express such concepts, whereas Japanese uses verb–verb compounds.

In this study, we make the following two points. First, the relationship between noun–noun (N–N) compounds and verb–particle constructions (VPCs) in English is equivalent to the relationship between N–N compounds and verb–verb compounds (VVCs) in Japanese. Specifically, compound words and complex predicates are created by combining the concepts represented by each constituent. Taking note of this similarity, Snyder (1995) observed that children in the process of acquiring English as a native language (henceforth ENL children) start to produce N–N compounds and English VPCs in the same period. In this paper, we report that children in the process of acquiring Japanese as a native language (henceforth JNL children) begin to produce N–N compounds and Japanese VVCs in the same period. This study, therefore, suggests that ENL children and JNL children follow the same acquisition process because the concepts represented by the particles and the verbs are the same.

Second, the acquisition processes followed by ENL children and JNL children are qualitatively approximate. Specifically, we show that both JNL and ENL children produce the verb or particle that can function as the functional head of the VVC or VPC before these complex forms. This is because VVCs and VPCs are both created by combining a lexical verb and a more functional head item.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of complex predicate constructions in English and Japanese. Specifically, we illustrate how English VPCs are expressed as VVCs in Japanese. Section 3 reviews acquisition studies on complex predicate constructions in English and Japanese. In Section 4, we present our hypothesis and predictions. Section 5 describes our empirical research using the CHILDES database. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Complex Predicates in English and Japanese

In this section, we show the relationship between English verb–particle constructions (VPCs) and Japanese verb–verb compounds (VVCs) to conduct a comparative study on complex predicates in both languages.

2.1. English Verb–Particle Construction

This section provides an overview of the English VPC, often called a phrasal verb (PV). The VPC is divided into three types (Dehé 2002; Ishikawa 1999). According to Dehé (2002, pp. 5–7), the first type comprises semantically compositional or transparent PV constructions, and the particles in this type are directional or spatial in meaning.

| (1) | a. | Sheila carried {in} the bags {in} (into the house). |

| b. | James carried {up} the suitcase {up} (up the stairs). | |

| c. | Sam took {out} the clothes {out} (out of the suitcase). | |

| d. | Mary threw {out} a box {out} (out of the room). | |

| e. | The lady put the hat on/on her head. | |

| f. | Sheila put the books away/on the shelf/there. | |

| (Dehé 2002, p. 6) | ||

These particles, such as in, up, out, on, and away, represent the direction or space in which the object moves. Furthermore, the expression in the round brackets shown in (1a)–(1d) shows the path through which the object moves. In addition, in (1e) and (1f), the particles on and away can be replaced by an appropriate directional PP, such as on her head and on the shelf or there, respectively.

The second type consists of idiomatic PV constructions. They form a semantic unit whose meaning is not fully predictable from the meaning of its constituents. In addition, this type of PV can be paraphrased by a simplex verb (Dehé 2002).

| (2) | a. | John will turn {down} that job {down}. (“refuse to accept”) |

| b. | You shouldn’t put {off} such tasks {off}. (“postpone”) | |

| c. | The baby threw {up} the meal {up}. (“vomit”) | |

| d. | They ran {off} the pamphlets {off}. (“copy”) | |

| (Dehé 2002, p. 6) | ||

In (2a), for example, the idiom turn down means “refuse to accept”. The verb turn and the particle down in the idiom do not maintain their original meanings: the verb turn does not take an object as its complement, and the particle down does not keep its original concept of “downward movement”.

The third type comprises aspectual PV constructions, in which the particle indicates the aspect of the verb phrase. For example, the particle up in (3a) means “completion”. Additionally, up in the aspectual PV construction eat up demonstrates the telicity of the event (Krifka 1998); therefore, although a simple verb eat can co-occur with the time adverbial with the prepositional phrase for an hour as in (3b), an aspectual PV construction cannot, as in (3c).

| (3) | a. | John ate {up} the cake {up}. |

| b. | John ate the cake for an hour. | |

| c. | *John ate up the cake for an hour. | |

| (Dehé 2002, p. 6) | ||

In addition to the particle up, away, and on are also used as aspectual particles, expressing the continuation of action.2

| (4) | a. | Hilary talked away about her latest project. |

| b. | Hilary talked on about her latest project. | |

| (Jackendoff 2002, p. 78) | ||

As described thus far, the VPCs in (2) are thought to be stored in the lexicon because they are a kind of idiom. In contrast, the VPCs in (1), (3), and (4) are considered to be processed in syntax because of their transparency. In this paper, we focus on the latter as the subject of discussion.

2.2. Japanese Verb–Verb Compounds

Japanese abounds in verb–verb compounds (VVCs) that combine two or more verbs. There are semantic and syntactic criteria that are used to determine whether a word is a compound verb. In this section, we overview the two criteria.

A semantic criterion examines the classification by the semantic relationship between a preceding verb (V1) and a subsequent verb (V2). According to the Compound Verb Lexicon by the NINJAL (2013–2015), which provides classification, definitions, and examples of over 2700 VVCs commonly used in contemporary Japanese, Japanese VVCs are divided into four types.

The first type is the “V + V type”. In this type, each verb has its own lexical meaning and semantic role. If a word is a compound verb of this type, V1 can be changed into a “te” form. Te-form verbs have a combination of two verbs which are concatenated by a linking morpheme, -te. For example, the verb phrase doa-o oshi-ake-ru (door-ACC push-open-PRES) ‘push the door open’ can be paraphrased by doa-o oshi-te-ake-ru (door-ACC push-GER-open-PRES) ‘push the door and open it’ or ‘open the door by pushing it’.3

The second type is the “Verb + Subsidiary verb”. A characteristic of this type is that V2 does not retain its original meaning. Therefore, it is not possible to paraphrase a VVC to a te-form verb in the same way as the V + V type. For example, the sentence Ame-ga furi-shikir-u (Rain-NOM rain-repeat-PRES) ‘Rain falls incessantly’ is grammatical, but the sentence including a te-form verb in the verb + subsidiary verb, *Ame-ga fut-te-shikir-u (Rain-NOM rain-GER-repeat-PRES) is not grammatical.

The third type is “prefix + V”. For example, hip in hip-par-u (pull-stretch-PRES) ‘pull’ and hip-patak-u (pull-slap-PRES) ‘slap’ can be distinguished, the former as a prefix-like verb and the latter as a prefix. Originally, hip was hik, but hik changed to hip due to regressive assimilation, where the k assimilates with the first sound of V2, as in par or patak. In addition, par and patak are used as the V2 in VVCs. When they are used alone, they are represented as har or hatak. First, hip in hip-par-u is interpreted as a prefix-like verb, because hip-par-u passes the -te test, as we saw in the V + V type. For example, the sentence John-ga rōpu-o hii-te hat-ta (John-NOM rope-ACC pull-GER stretch-PST) ‘John stretched a rope by pulling it’ is grammatical. This means that hip in hip-par-u retains the original meaning and has the characteristics of a verb. However, if hik were a pure verb, a conjunctive form marker i would need to be inserted at the end of the stem, and since i does not need to be inserted as in hik-(*i)-par-u, it can be concluded that hik is a prefix-like verb: it retains its original meaning, but it does not need a conjunctive marker, thus behaving as a prefix. On the other hand, hip in hip-patak-u is a prefix that plays a role in emphasizing the meaning of V2. Unlike hip-par-u, it does not pass the -te test: *John-ga Mary-o hii-te hatai-ta (John-NOM Mary-ACC pull-GER slap-PST), so we can conclude that its verbal meaning is absent. Moreover, hip-patak-u does not need a conjunctive form marker i like *hik-(*i)-patak-u. Thus, hip in hip-patak-u is seen as a prefix.

The fourth type of compound verb is “V (simple word)”. For example, ochi-tsuk-u (fall-arrive-PRES) ‘settle down’ and omoi-das-u (think-come.out-PRES) ‘remember’ are no longer recognized as consisting of two verbs by contemporary speakers.

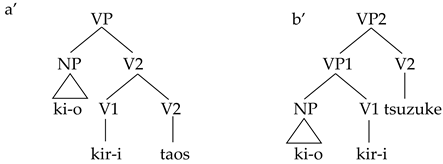

The second criterion is a syntactic criterion. Kageyama (1993, 2016) proposed a dichotomy based on internal structural differences within compound verbs composed of two consecutive verbs: lexical compound verbs and syntactic compound verbs.

| (5) | a. | Lexical Compound Verbs |

| ki-o kiri-taos-u (tree-ACC cut-topple-PRES) ‘cut a tree down’ | ||

| b. | Syntactic Compound Verbs | |

| ki-o kiri-tsuzuke-ru (tree-ACC cut-keep-PRES) ‘keep cutting a tree’ | ||

| ||

According to Kageyama (2013), lexical compound verbs are characterized by the direct attachment of V2 to V1 (kir) with “i”, a conjunctive form marker, in between. In contrast, V2 in syntactic compound verbs takes VP1 as an argument. V2 in syntactic compound verbs expresses an aspectual property of V1. For example, das-u (begin-PRES) ‘begin’, sugi-ru (exceed-PRES) ‘too much’, tsuzuke-ru (keep-PRES) ‘keep’, and kake-ru (hang-PRES) ‘be.about.’

Based on the two criteria above, this study regards the V + V type, V + Subsidiary verb type, and prefix-like verb + V type in the prefix + V type in classification as Japanese compound verbs because these types of compound verbs are classified into lexical compound verbs or syntactic ones. Note that the prefix + V type whose V1 is a prefix-like verb is considered a compound verb because V1 retains the original meaning and has the characteristics of a verb. For example, syntactic compound verbs include kiri-tsuzuke-ru (cut-keep-PRES) ‘keep cutting’ (V + Subsidiary type), while lexical compound verbs include oshi-ake-ru (push-open-PRES) ‘push open’ (V + V type), furi-shikir-u (rain-repeat-PRES) ‘descend’ (V + Subsidiary type), and hip-par-u (pull-stretch-PRES) ‘pull’ (prefix-like verb+V type). On the other hand, the prefix + V type whose V1 is a prefix and the fourth type (V (simple word) type) are excluded from compound verbs because they are no longer considered a compound verb consisting of two words.

2.3. An Issue with Parallelism between English VPCs and Japanese VVCs

This section discusses the parallelism between English VPCs and Japanese VVCs. In particular, the concepts represented by English VPCs shown in (1), (3), and (4) are expressed by VVCs in Japanese. For example, the compositional PV constructions shown in (1a)–(1d) correspond to Japanese lexical compound verbs, as in (6).

| (6) | a. | Sheila-wa | kaban-o | (ie-no-naka-ni) | hakobi-kom-da. |

| Sheila-TOP | bag-ACC | (house-GEN-inside-to) | carry-go.in-PST | ||

| ‘Sheila carried {in} the bags {in} (into the house).’ | |||||

| b. | James-wa | sūtsukēsu-o | (kaidan-o nobot-te) | hakobi-age-ta. | |

| James-TOP | suitcase-ACC | (stairs-ACC climb-GER) | carry-raise-PST | ||

| ‘James carried {up} the suitcase {up} (up the stairs).’ | |||||

| c. | Sam-wa | (sūtsukēsu-kara) | fuku-o | tori-dashi-ta. | |

| Sam-TOP | (suitcase-out.of) | clothes-ACC | take-come.out-PST | ||

| ‘Sam took {out} the clothes {out} (out of the suitcase).’ | |||||

| d. | Mary-wa | (heya-kara) | hako-o | nage-dashi-ta. | |

| Mary-TOP | (room-out.of) | box-ACC | throw-come.out-PST | ||

| ‘Mary threw {out} a box {out} (out of the room).’ | |||||

In addition, the aspectual PV constructions illustrated in (3a) and (4) correspond to Japanese syntactic compound verbs, as in (7).

| (7) | a. | John-wa | kēki-o | tabe-kit-ta. | |

| John-TOP | cake-ACC | eat-cut-PST | |||

| ‘John ate {up} the cake {up}.’ | |||||

| b. | Hilary-wa | zibun-no saikin-no | purojekuto-nitsuite | hanashi-tsuzuke-ta. | |

| Hilary-TOP | self-GEN latest-GEN | project-about | talk-keep-PST | ||

| ‘Hilary talked {away/on} about her latest project.’ | |||||

As shown in (6) and (7), the compositional PV constructions in (1) and the aspectual PV constructions in (3a) and (4) are represented by Japanese lexical/syntactic compound verbs, respectively.

Note that not all Japanese VVCs correspond to English VPCs. Some difference between English and Japanese can be observed in terms of boundedness. Boundedness is a semantic feature associated with the referential limits of lexical items. [+bounded] paths denote starting points or destinations. On the other hand, [−bounded] paths do not indicate them. For example, English motion verbs co-occur with [+bounded] paths, but the direct translation of (8a) into Japanese, as shown in (8b), is unacceptable. To express [+bounded] paths in Japanese in an acceptable way, VVCs are necessary, as shown in (8c).

| (8) | a. | She ran out of the room. | ||

| b. | *Kanojo-wa | heya-no-naka-kara | hashit-ta. | |

| she-TOP | room-GEN-inside-from | run-PST | ||

| c. | Kanojo-wa | heya-no-naka-kara | hashiri-de-ta. | |

| She-TOP | room-GEN-inside-from | run-go.out-PST | ||

| ‘She ran out of the room.’ | ||||

| (Ueno and Kageyama 2001, p. 62) | ||||

In this way, VVCs and VPCs are not in complete one-to-one correspondence. Specifically, VVCs correspond closely to VPCs, as shown in (6) and (7), whereas the VVCs with [+bounded] paths (e.g., (8c)) do not correspond to VPCs but to a Verb + a full PP (e.g., (8a)). The following section provides an overview of the acquisition process of complex predicates in Japanese and English.

3. The Compounding Parameter and Issues Related to VPCs and VVCs

This section provides an overview of the Compounding Parameter. First, Snyder (1995) observed that all languages with a VPC share the property of allowing speakers to invent creative N–N compounds whenever needed. Creative N–N compounds are compound words freely created to suit the situation. In languages where it is possible to create such compound words, native speakers other than the speaker who created the N–N compounds can also automatically interpret the novel compound words to fit the context of the discourse. In other words, Snyder (1995) reported that creative N–N compounds are not observed in languages where VPCs are not observed. For example, there is a VPC in English, whereas there is no VPC in Spanish, as shown in (9).

| (9) | a. | Mary | lifted | the | box | up. | (English) | |

| b. | María | levantó | la | caja | (?*arriba). | (Spanish) | ||

| Mary | lifted | the | box | upwards | ||||

| (Snyder 2007, p. 82) |

As illustrated in (9b), arriba, a Spanish counterpart of the particle up in English, is unnecessary in Spanish, and Spanish does not have VPCs.

In addition, Snyder (1995, 2001) observed differences among English and Spanish in whether these languages can create compounds. For example, the N–N compounds in English and Spanish as shown in (10) have the lexicalized meaning of “underwater diver”. On the other hand, the English N–N compound can also be interpreted differently, such as a “man who does scientific research on frogs” or a “man who collects statues of frogs”, as long as the context allows the listener to see how frogs are relevant, whereas the Spanish N–N compound cannot.

| (10) | a. | frog man | (English) | ||||

| b. | hombre rana | (Spanish) | |||||

| man frog | |||||||

| (Snyder 2007, p. 83) | |||||||

Furthermore, Japanese belongs to the English type in terms of the availability of creative N–N compounds. For example, yuki otoko (snow man) ‘snowman’ is the name of Japanese specters, but it can also be interpreted as a “man who does scientific research on snow” or a “man collects snow crystal specimen” in the same way as English N–N compounds.

As a result of investigating various languages in a cross-linguistic survey, Snyder found the relationship between creative N–N compounds and VPCs, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The relationship between creative N–N compounds and VPCs (adapted from Snyder 2016).

Based on Table 1, Snyder made the prediction shown in (11):

| (11) | Among children acquiring English, any child who knows that English permits | ||||||

| separable verb–particle combinations should also know that English permits | |||||||

| creative compounding. | |||||||

| (Quoted in Snyder 2021, p. 871) | |||||||

To verify the prediction in (11), Snyder (2007) used 19 CHILDES corpora containing speech data from ENL children. As a result, he observed a strong correlation between the first clear use of VPCs and the first clear use of creative N–N compounds.4

Snyder (2007, 2021) suggested that shared prerequisites are necessary to produce creative N–N compounds and VPCs and that, when acquired, they are acquired simultaneously. He refers to the shared grammatical prerequisite as the positive (or “marked”) setting of “the Compounding Parameter”.

| (12) | The Compounding Parameter (TCP): | ||||||

| The grammar {disallows*, allows} formation of endocentric compounds during | |||||||

| the syntactic derivation. [*unmarked value] | |||||||

| (Snyder 2001, p. 328) | |||||||

If TCP is set to positive, the language is represented as [+TCP], otherwise [−TCP]. The languages of [+TCP] are the languages in which creative N–N compounding is classified as Yes in Table 1. In contrast, the languages of [−TCP] are the languages where it is classified as No. Therefore, English and Japanese are [+TCP] languages, while Spanish is [−TCP].

The following section provides a hypothesis to support that Japanese is a [+TCP] language and two predictions.

4. Hypothesis and Prediction

As observed in Section 2.3, English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are similar. Still, a morphosyntactic structure common to them has not been identified, and it can even be said that their correspondence has not been empirically demonstrated. This paper seeks to resolve these outstanding issues by showing that the acquisition data of VPCs and VVCs provide evidence for the grammatical parallelism between these two constructions.

The hypothesis for this study is as follows:

| (13) | Japanese, a [+TCP] language, does not have separable particles (Table 1) because |

| it uses VVCs instead of VPCs. |

If our proposition (or working hypothesis) is correct, two things are predicted:

| (14) | Prediction 1: |

| JNL children will produce creative N–N compounds and VVCs in the same period, just as the ENL children in Snyder’s (2001) study produced creative N–N compounds and VPCs in the same period. | |

| Prediction 2: | |

| Children will utter the particle or verb that can be the functional head of a VPC or VVC before they produce these complex predicates. |

English VPCs and Japanese VVCs correspond, as demonstrated in Section 2.3. If the hypothesis in (13) is correct, it is predicted that creative N–N compounds and VVCs will be produced by JNL children in the same period because Japanese is classified as a [+TCP] language, in the same way that creative N–N compounds and English VPCs have already been observed in the same period (Prediction 1). Furthermore, Prediction 2 is a logical prediction if complex predicates are created by combining already-known constituents. The same point has already been made by Los et al. (2012, pp. 22–23), who draw on the observations by Bennis et al. (1995, p. 76) and show that seven children in the process of acquiring Dutch as a native language acquire particles earlier than separable complex verbs.

The following section examines the utterances of three children using the CHILDES to investigate whether the hypothesis and predictions are valid.

5. Verification

5.1. Subjects

This study investigated two JNL children (Sumihare and Aki) and an ENL child (Sarah) using data from the CHILDES (Child Language Data Exchange System) (MacWhinney 2000; Oshima-Takane et al. 1998), as shown in Table 2. The CHILDES database includes transcripts and media data collected from conversations with adults and children. We also referred to Noji (1973–1977) to confirm Sumihare’s speech record.

Table 2.

Subjects and their corpora.

5.2. Method

CLAN5 was used to analyze speech data. Utterances identified as imitations were excluded from the analysis. In Sarah’s case, following the approach outlined by Snyder (2007), all words used in her speech were extracted, and, from these, all particles were extracted. Subsequently, all relevant utterances were inspected manually. On the other hand, for Sumihare, all verbs were initially extracted. Then, starting with files from a younger age, the place of each verb in terms of order of appearance was manually examined. Furthermore, to verify whether the identified first clear use of verbs was genuine, the files containing these initial verbs were scrutinized. In addition, we manually searched for the first clear use of creative N–N compounds.

Furthermore, to investigate different native speakers’ processes of acquiring complex predicates, the mean length of utterance (MLU) based on research by Brown (1973) was also used in addition to the first clear use. This is because the MLU can be used to show the relationship between the child’s language ability and their first clear use of the complex predicate. We calculated the MLUm (morpheme) for the month in which the first clear use of complex predicates was uttered by using CLAN.6 Regarding MLU stage and MLU value, those for English are based on Brown (1973), and those for Japanese are based on Miyata (2017), as shown in Table 3. Note that Sarah’s and Aki’s speech data were continuous data recorded at a fixed time, while Sumihare’s speech data were diary data (what the recorder wants to record). Due to the qualitative difference between continuous and diary data, diary data tend to have a higher MLU value than continuous data (Kido 2024). Therefore, we should also consider this when analyzing the three children’s data.

Table 3.

MLU stage, MLU value, and their characteristics in English and Japanese.

5.3. Results and Discussion

5.3.1. Result of Prediction 1

To verify Prediction 1, which is restated below, we examined examples of creative N–N compounds and VVCs.

| Prediction 1: | |

| JNL children will produce creative N–N compounds and VVCs in the same period, just as the ENL children in Snyder’s (2001) study produced creative N–N compounds and VPCs in the same period. |

Table 4 is the process by which Sumihare produces creative N–N compounds.

Table 4.

The process by which Sumihare produces creative N–N compounds.7

As shown in Table 4, Sumihare only uttered the creative N–N compound rim mamma when he had reached the age of 1 year and 6 months. He did not, however, use another one until 2 years and 0 months. When he was approximately 2 years and 1 month old, he started to produce creative N–N compounds productively. For this reason, although Sumihare’s first appearance of creative N–N compounds is at 1 year and 6 months old, his first clear use of them is at approximately 2 years and 1 month old.

In addition, Sumihare’s and Aki’s utterances including VVCs were already investigated by Kido (2017, 2020). Kido reported that Sumihare produced the first clear use of VVCs, such as hip-par-u (pull-stretch-PRES) ‘pull’ (2;01:09) and that Aki produced the first clear use of VVCs, such as hit-tsuk-u (pull-attach-PRES) ‘stick’ (2;07:12). Furthermore, as a result of investigating Aki’s first clear use of creative N–N compounds, Aki productively uttered creative N–N compounds, such as awa bū (bubble car) ‘bubble car’ (2;07:12) and awawā jūdō (bubble car) ‘bubble car’ (2;07:12).

On the other hand, Snyder (2007) reported the first clear uses of VPCs and creative N–N compounds produced by Sarah. While Sarah began to productively produce VPCs of the word order V–NP–Particle at the age of 2;06:20, as in (15a)–(15b), she produced her first clear use of a creative N–N compound, ribbon hat, at the age of 2;07:05, as in (15c).

| (15) | a. | FAT: how can he see? what if I took your eyes. SAR: took my eye on. | (2;06:20) |

| b. | FAT: can you see now? SAR: xx my eye. pull my eye out. | (2;06:20) | |

| c. | SAR: a ribbon hat. MOT: huh? SAR: a ribbon. MOT: there’s a ribbon on his hat yeah. | (2;07:05) |

To summarize, Table 5 shows the ages at which the first clear uses of VPCs, creative N–N compounds (CNNCs), and VVCs were uttered and the MLU values at those ages.

Table 5.

MLU value and the first clear use of VPCs, CNNCs, and VVCs.

Discussion of Prediction 1

Prediction 1 is reasonable. Specifically, as mentioned in the previous section, Sarah used VPCs and creative N–N compounds at approximately the same age, 2 years and 6 months and 2 years and 7 months, respectively. In addition, Sumihare began to utter VVCs, such as hip-par-u (pull-stretch-PRES) ‘pull’ at 2 years and 1 month. Also, as summarized in Table 4, he began to utter creative N–N compounds, such as wakame ojichan ‘seaweed man’, at 2 years and 1 month, the same age as the VVCs. Similarly, Aki’s first clear use of creative N–N compounds, such as awawā jūdō (bubble car) ‘bubble car’ and VVCs, such as hit-tsuk-u (pull-attach-PRES) ‘stick’ was at the same age, 2 years and 7 months. In response to the question of why they are produced during the same period, one answer is that there are shared prerequisites necessary to produce them and that, when these are acquired, they are produced simultaneously. If our discussion is on the right track, Sumihare’s acquisition of creative N–N compounds and VVCs suggests that Japanese is a language that sets the Compounding Parameter (TCP) to positive.

Furthermore, we checked what the MLU values were for the months when children produced complex predicates (i.e., VVCs or VPCs) and creative N–N compounds based on Table 3. Sarah produced VPCs and creative N–N compounds during MLU Stage I. Aki also produced creative N–N compounds and VVCs during Stage II. On the other hand, Sumihare produced them during Stage IV. It should be emphasized that both Aki and Sarah, who were observed by the same method (continuous data), had a close MLU value of around 1.8 for both creative N–N compounds and complex predicates (e.g., VPCs and VVCs), as shown in Table 5. Thus, by comparing the MLU values of creative N–N compounds and complex predicates in ENL and JNL children (Sarah and Aki), it is thought that children set TCP to positive when the MLU value reaches around 1.8.8 To verify this, however, it will be necessary to investigate the speech data of other children.

In this way, adopting TCP, we conclude from the results that English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are related expressions in a grammatical sense. In other words, they are not just a paraphrase but a realizational variation of abstract linguistic structures.

5.3.2. Result of Prediction 2

To verify Prediction 2, which is restated below, we examined Sarah’s production and Sumihare’s production.

| Prediction 2: | |

| Children will utter the particle or verb that can be the functional head of a VPC or VVC before they produce these complex predicates. |

Sarah’s Production

This section reports Sarah’s speech. In the first stage of acquiring a VPC, verbs do not appear; only particles are used. In addition, the particle is used as if it were a verb.9 Specifically, up was first produced at 2;03:05. Subsequently, down was produced at 2;06:13.

| (16) | a. | SAR: c(o)me (h)ere. up dere. | (2;03:05) |

| b. | SAR: do(ll)y? MOT: hmm? SAR: he up xx Santa + Claus. | (2;05:30) | |

| c. | SAR: toothpaste up dere. | (2;07:18) | |

| d. | MOT: what? SAR: where lettuce. xx lettuce up dere. | (2;09:14) |

| (17) | MOT: 0 [=! laughs]. GRA: what’s that? SAR: slide down slide. | (2;06:13) |

(16a) shows the first utterance where up is considered to be used as a predicate with the meaning of the verb rise. In (16b), up is also considered to be used as a predicate, such as raise. Both (16c) and (16d) demonstrate the use of up to express spatial orientation, even though the copula is not expressed. Correctly, these are thought to be Toothpaste is up there. and Lettuce is up there. The usage of down in (17) is unclear in terms of whether it is a predicate. If we think that slide down slide is the answer to the question her grandmother asked, it could be construed as [[N slide][Pred down slide]], but it could also be thought of as an expression of the child’s desire to slide down the slide without a direct answer to the grandmother, i.e., [VP [slide down] slide].

In addition, after 2 years and 3 months, location marker particles, such as in and out, are often used from the early stages of the observation period.

| (18) | a. | FAT: what’s it doing there? SAR: raining out. | (2;03:19) |

| b. | MOT: where’s your dog? SAR: my doggie out. | (2;03:19) | |

| c. | FAT: it’s raining out now. SAR: xx out? FAT: hmm? SAR: go out. | (2;03:19) | |

| d. | SAR: carriage here. MOT: where? SAR: in here. | (2;03:22) | |

| e. | SAR: goodbye # goodbye # goodbye. SAR: xx rock. go (a)way. | (2;08:25) | |

| f. | SAR: box. xx. xx go in (th)ere. | (2;08:25) | |

| g. | SAR: let me go in. FAT: what’s a matter? SAR: let me go in. | (2;11:17) | |

| h. | MOT: I want you to tell me a story first. SAR: once upon a time # the three bears <went up the stairs>. Climb up the stairs. | (3;01:03) |

From the age of 2 years and 3 months to 2 years and 8 months, Sarah used directional expressions, such as out, away, and in, in conjunction with the motion verb go, as shown in (18c), (18e), and (18f). Subsequently, at the age of 2 years and 11 months, she employed the causative verb let, as illustrated in (18g). Shown in (18h) is an example of a verb other than go that contains the concept of GO and the first appearance of VPCs of the word order V–Particle–NP. After age 3, as indicated by the utterance in (18h), she frequently produced VPCs of the word order V–Particle–NP.

Furthermore, after 2 years and 4 months, only limited verbs, such as put, co-occur with particles, as shown in (19).

| (19) | a. | SAR: put (i)n (th)ere. MOT: what? SAR: put (i)n (th)ere bag. | (2;04:26) |

| b. | MOT: take Daddy-’s nose off. SAR: put back. | (2;06:20) | |

| c. | SAR: cow. FAT: yeah # the cow is pretty. SAR: he hat on. | (2;07:12) | |

| d. | MOT: oh # c(o)me (h)ere and I’ll fix it. ok? SAR: put yours in. | (2;08:25) | |

| e. | SAR: he eating. MOT: um # what’s he doing here? SAR: xx put feet in. | (2;09:29) | |

| f. | MOT: aunt who? SAR: Esther. I want put dis on (th)ere. | (2;10:05) |

As indicated in (19a), Sarah started producing utterances containing put at the age of 2 years and 4 months. However, the verb put is often not produced, as seen in (19c). The correct use of the verb put begins at 2 years and 8 months, as illustrated in (19d)–(19f).

The utterances seen in (16)–(19) can be expressed with simple verbs in Japanese. For example, up in (16b) is expressed by the verb age-ru (raise-PRES) ‘raise’, down in (17) is described by the verb sube-ru (slide.down-PRES) ‘slide down’, go out in (18c) is expressed by the verb de-ru (go.out-PRES) ‘go out’, and put in in (19a) is shown by the verb ire-ru (put-PRES) ‘put.’ Therefore, next, we will look at VPCs that correspond to VVCs in Japanese. Sarah produced such VPCs at the age of 2 years and 4 months, as shown in (20).

| (20) | a. | MOT: knock at the door. SAR: xx door. peek in. | (2;04:12) |

| b. | SAR: throw (a)way? | (2;04:12) |

The VPCs peek in and throw away in (20) are expressed by the Japanese VVC nozoki-kom-u (peek-go.in-PRES) ‘peek in’ and nage-sute-ru (throw-discard-PRES) ‘throw away’. Like (15a) and (15b) reported by Snyder (2007), at around 2 years and 6 months, Sarah began to productively produce VPCs of the word order V–NP–Particle. Table 6 illustrates examples of VPCs produced by Sarah from the age of 2 years and 7 months onward.

Table 6.

VPCs produced by Sarah and the corresponding Japanese VVCs.

Finally, we see an example of idiomatic VPCs produced by Sarah.

| (21) | MOT: dollie-s # huh. SAR: dollie-s. I go way up. | (2;08:25) |

Sarah uttered an idiom, go way up, at the age of 2 years and 8 months, as in (21). In the next section, we report examples of VVCs produced by a JNL child, Sumihare.

Sumihare’s Production

This section highlights the results of the analysis of Sumihare’s utterances. Here, we describe the simple verbs uttered before the VVCs and the situations in which these VVCs were produced.

As shown in Table 7, tsuk-u (attach-PRES) ‘attach’, which serves as V2, which is the functional head of the VVCs, is produced as a simple verb at 1 year 6 months. The first appearance of a VVC whose V2 was tsuk-u was koge-tsuk-u ‘burn to’, as in (b) in Table 7.

Table 7.

The process by which Sumihare produces VVCs involving tsuk-u (attach-PRES) ‘get/attach’ and the corresponding English VPCs.

Table 8 lists examples in which the V2 is kom-u (go.into-PRES) ‘into’. Since kom-u is not a free morpheme in Japanese, it is not used alone; therefore, Table 8 shows only examples of VVCs.

Table 8.

The process by which Sumihare produces VVCs involving kom-u (go.into-PRES) ‘into’ and the corresponding English VPCs.

Furthermore, let us look at examples in which V2 is der-u (go.out-PRES) ‘go out’ as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

The process by which Sumihare produces VVCs involving der-u (go.out-PRES) ‘out’ and the corresponding English VPCs.

Examples of V2 being das-u (come.out-PRES) ‘come out’ are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

The process by which Sumihare produces VVCs involving das-u (come.out-PRES) ‘come out’ and the corresponding English VPCs.

In addition, examples of V2 being age-ru (raise-PRES) ‘raise’ are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

The process by which Sumihare produces VVCs involving age-ru (raise-PRES) ‘raise’ and the corresponding English VPCs.

The VVCs in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 are classified into lexical compound verbs. In addition, as illustrated in Table 12, Sumihare also produced syntactic compound verbs whose V2 expresses an aspect of V1 after the age of 2 years and 4 months.

Table 12.

Syntactic compound verbs that Sumihare produced.

In this section, we have shown examples of the simple verbs and compound verbs produced by Sumihare. The next section examines whether Prediction 2 is valid based on examples of Sarah’s and Sumihare’s utterances.

Discussion of Prediction 2

Prediction 2 is proven adequate because Sarah’s and Sumihare’s utterances have many similarities in the acquisition process of complex predicates. We highlight the parallelisms between Sarah and Sumihare’s acquisition processes. Specifically, Sarah and Sumihare expressed the constituents that form complex predicates (e.g., particles in English and verbs representing the path in Japanese) before the complex predicates they comprise, i.e., VPCs and VVCs. For example, as evident in Sumihare’s examples in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11, verbs representing a path of motion in Japanese VVCs (excluding kom-u (go.into-PRES) ‘into’) were produced before the VVCs were produced. (Recall that kom-u is excluded from the discussion because it is a bound morpheme.) Similarly, Sarah, as demonstrated in (18), articulated particles representing a path of upward motion, such as up, before VPCs, such as xx pull my pants up, at the age of 2 years, 10 months, and 20 days, as shown in Table 6.

In addition, our findings imply that there is a constant order in the emergence of the “path” concept. In both Sarah and Sumihare’s productions, irrespective of the language (English or Japanese), there is a commonality in the initial observation of verbs functioning as predicates expressing the path. For example, Sarah, as illustrated in (16) and (17), used particles with the [+bounded] property as predicates. Specifically, at 2 years and 3 months, she used up as if it were a predicate, conveying the meaning of rise or raise. Additionally, she used down as if it were a predicate to indicate the VPC slide down or go down at 2 years and 6 months.10

Similarly, as shown in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10, Sumihare began producing VVCs in which V2 corresponds to [+bounded] particles representing a direction, such as to, in, and out, at the beginning of the second year of life. Importantly, Sumihare inevitably produced the verb alone before the VVCs, where V2 is a [+bounded] verb. For example, he produced tsuk-u (attach-PRES) ‘attach’ (1;06) and de-ru (go.out-PRES) ‘go out’ (1;07), comprising V2 in the VVCs koge-tsuk-u (burn-attach-PRES) ‘burn on’ and hai-de-ru (creep-go.out-PRES) ‘creep out’, before the VVCs koge-tsuk-u (2;04) and hai-de-ru (2;10). On the other hand, Sumihare did not produce V2s that were unrelated to boundedness alone before producing VVCs. For example, he did not produce hik-u (pull-PRES) ‘pull’, har-u (stretch-PRES) ‘stretch’, and hōr-u (throw-PRES) ‘throw’ before the VVCs hip-par-u (pull-stretch-PRES) ‘pull’ (2;01) or hōri-das-u (throw-come.out-PRES) ‘throw out’ (2;10).

This is common among both ENL children and JNL children. From this point of view, the concepts related to [+bounded] appear in the same order even though the languages are different. As to why there is a commonality in the different acquisition processes, this is a future research topic, but our findings are expected to make it possible to further pursue the universal properties of human beings.

6. Concluding Remarks and Further Related Issues

In this study, using the CHILDES database, we have shown the acquisition process of complex predicates (i.e., Japanese VVCs and English VPCs). Specifically, verbs or particles representing a path of motion in English VPCs and Japanese VVCs were produced before the VPCs and VVCs. In particular, it was common to use [+bounded] verbs or particles when first acquiring complex predicates (Japanese VVCs and English VPCs)—for example, kom-u (go.into-PRES) ‘into’ and das-u (come.out-PRES) ‘come out’ in Japanese and in and out in English. In this way, a parallelism was observed between the acquisition process of VPCs by ENL children and that of VVCs by JNL children. For these reasons, Prediction 2 was confirmed to be valid.

Nevertheless, there were differences in Sarah and Sumihare’s speech. Sarah used not only [+bounded] particles, such as to, in, into, on, out, and up, but also the [−bounded] particles away, around, and through when producing VPCs, as shown in (20), (21), and Table 6. On the other hand, Sumihare used only verbs corresponding to English [+bounded] particles, such as to, in, into, on, out, and up, when producing VVCs, as shown in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11. It is a mystery why VVCs whose V2 is a verb that corresponds to [−bounded] particles are not observed. This point will be considered as a future research issue.

Furthermore, based on the theoretical classification of complex predicates, as shown in Section 2, Sumihare produced both lexical and syntactic compound verbs. Specifically, lexical compound verbs were produced at 2 years and 1 month, as reported by Kido (2017, 2020), whereas syntactic compound verbs whose V2 represents aspectual meaning, such as start (e.g., das-u (begin-PRES) ‘begin’), were produced at 2 years and 4 months, as shown in Table 12. On the other hand, Sarah produced only VPCs that correspond to the Japanese lexical compound verbs; the VPCs included semantically compositional or transparent phrasal verbs and idiomatic phrasal verbs, as shown in (15a) and (15b) as well as (18)–(21) and Table 6. In other words, she did not produce aspectual phrasal verbs corresponding to Japanese syntactic compound verbs. However, why does such a difference occur even though the events represented are the same in English VPCs and Japanese VVCs? This question should also be considered as a future research topic.

In addition, because of the commonality in that creative N–N compounds and complex predicates (i.e., VPCs and VVCs) were observed in the same period, Prediction 1 was deemed appropriate for this paper. Specifically, Sarah began to productively produce VPCs at around 2 years and 6 months, while she produced a first clear use of the creative N–N compound ribbon hat at the age of 2 years, 7 months, and 5 days. On the other hand, Sumihare produced creative both N–N compounds and VVCs at 2 years and 1 month. In this way, a parallelism was also observed between the acquisition process of creative N–N compounds and VPCs by ENL children and that of creative N–N compounds and VVCs by JNL children. For these reasons, Prediction 1 was confirmed to be valid.

Thus, as shown above, the hypothesis in (13) was supported because the two predictions are considered valid. In other words, our findings suggest that Japanese is correctly classified as a [+TCP] language. In addition, our finding that JNL children produced their first clear uses of creative N–N compounds and of VVCs in the same period, just as the ENL children did for VPCs and creative N–N compounds, suggests that Japanese makes use of VVCs instead of VPCs. Furthermore, this parallelism observed among ENL and JNL children in the acquisition process of creative N–N compounds and VPCs/VVCs, respectively, suggests that English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are related expressions in a grammatical sense. This in turn implies that English VPCs and Japanese VVCs are not connected by more than their semantics; indeed, it implies that they are realizational variations of abstract linguistic structures.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K13161 and JP24K16075.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this paper are included in the CHILDES at https://childes.talkbank.org/, accessed on 28 July 2024. The Compound Verb Lexicon [Software] was created by the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL) (2013–2015). It is available at https://vvlexicon.ninjal.ac.jp/, accessed on 28 July 2024.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers and two academic editors of Languages, for their generous comments and constructive criticism on the draft. Their thoughtful and detailed comments significantly improved this paper’s presentation in terms of structure, logical flow, and the hypothesis. Without their comments and criticism, this paper would not have been completed. I would like to thank them from the bottom of my heart. I would also like to thank Joseph Tabolt for proofreading this paper. Of course, all errors and shortcomings are mine.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The abbreviations used in this paper are as follows: nominative (NOM), accusative (ACC), genitive (GEN), topic marker (TOP), copula (COP), present (PRES), past (PST), discourse marker (DM), imperative (IMP), gerund(ive) (GER), and progressive (PROG). |

| 2 | Jackendoff (2002) argues that through and over are also aspectual particles, such as read/scan/skim the book through, sing/play the aria through, and cook the food over, sing/play the aria over. However, these VPCs are less productive than those with up, away, and on. Therefore, this paper does not categorize them as aspectual particles. See Jackendoff (2002, p. 80) for more detail. |

| 3 | A V + V type is a VVC, but a te-form verb is not because there is no lexical integrity between V1 and V2. For example, oshi-(*mo-)ake-ru (push-(*also-)open-PRES) is not applicable because oshi-ake-ru is regarded as a word. On the other hand, the te-form verb oshi-te-mo-ake-ru (push-GER-also-open-PRES) is applicable because oshi-te-ake-ru is seen as two words: oshi-te and ake-ru. |

| 4 | First clear use is a term used by Stromswold (1996) and Snyder (2007). Snyder (2007) defines the criterion for acquisition as the age of “first clear use, followed soon after by regular use” (p. 71). In this study, we use Snyder’s (2007) definition. |

| 5 | CLAN is an acronym for Computerized Language Analysis and is a generic term for program packages used for analyzing data based on the CHAT format (Sugiura et al. 1997). |

| 6 | Since Japanese is an agglutinative language, the boundary between words and morphemes is unclear. Accordingly, when investigating speech by JNL children, it is desirable to calculate MLUw (word) from 2;00 to 2;06 and calculate MLUm (morpheme) when the MLU value exceeds 1.5 (Miyata 2012, p. 4). We calculated Sumihare’s utterances in terms of MLUm, however, because English is calculated in MLUm; otherwise, we could not compare them on the same basis. |

| 7 | The abbreviations of the speakers as follows: child (CHI), father (FAT), grandmother (GRA), mother (MOT), other (OTH), and Sarah (SAR). |

| 8 | Sumihare’s MLU value was higher than Aki’s and Sarah’s MLU values. The reasons for this result may be that different recording methods were used: continuous and diary data. |

| 9 | Suzuki (2017) also observed that the particles are used like a predicate. |

| 10 | These findings were also observed by Suzuki (2017), showing that the observed VPCs in the first step are [+bounded] particles, such as in, on, and up. |

References

- Bennis, Hans, Marcel den Dikken, Peter Jordens, Susan Powers, and Jürgen Weissenborn. 1995. Picking Up Particles. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Dawn MacLaughlin and Susan McEwan. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger. 1973. A First Language: The Early Stages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dehé, Nicole. 2002. Particle Verbs in English: Syntax, Information Structure, and Intonation. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, Kazuhisa. 1999. English Verb–Particle Constructions and a V0–Internal Structure. English Linguistics 16: 329–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackendoff, Ray. 2002. English Particle Constructions, the Lexicon, and the Autonomy of Syntax. In Verb–Particle Explorations. Edited by Nicole Dehé, Ray Jackendoff, Andrew McIntyre and Silke Urban. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama, Taro. 1993. Bunpō to Gokeisei [Grammar and Word Formation]. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo. [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama, Taro. 2013. Goiteki-Fukugōdōshi no Shin-Taikei [A New System of Lexical Compound Verbs]. In Fukugōdōshi Kenkyū no Saisentan [Frontiers of Research on Compound Verbs]. Edited by Taro Kageyama. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama, Taro. 2016. Verb-Compounding and Verb-Incorporation. In Handbook of Japanese Lexicon and Word Formation. Edited by Taro Kageyama and Hideki Kishimoto. Boston and Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 273–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, Yasuhito. 2017. Nihongo Fukugōdōshi-no Kakutoku: CHILDES-o Shiyō-shita Jissho Kenkyū [Acquisition of Japanese Compound Verbs: An Empirical Study Using CHILDES]. Ph.D. dissertation, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, Yasuhito. 2020. Acquisition of Verb–Verb Compounds in Child English and Japanese: An Empirical Study Using CHILDES. In Tōgo Kōzō to Goi no Takaku-teki Kenkyū. [Multidimensional Studies of Syntactic Structures and the Lexicon]. Edited by Yile Yu, Kiyoko Eguchi, Yasuhito Kido and Miho Mano. Tokyo: Kaitakusha, pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, Yasuhito. 2024. Hatsuwa Dēta Bēsu CHILDES Browsable Database-o Mochiita Chōsa [Investigation Using CHILDES Browsable Database for Language Acquisition]. In Pasokon-ga Areba Dekiru! Kotoba-no Jikken Kenkyū-no Hōhō Dai 2 Han [A Hands-On Guide to Experimental Methods in Linguistic Research, 2nd ed.]. Edited by Kentaro Nakatani. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, pp. 217–56. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 1998. The Origins of Telicity. In Events and Grammar. Edited by Susan Rothstein. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 197–235. [Google Scholar]

- Los, Bettelou, Corrien Blom, Geert Booij, Marion Elenbaas, and Ans van Kemenade. 2012. Morphosyntactic Change: A Comparative Study of Particles and Prefixes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, Susanne. 2004. Japanese: Aki Corpus. Pittsburgh: TalkBank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, Susanne. 2012. Guideline for Japanese MLU: How to Compute MLUw and MLUm. Journal of Health and Medical Science 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, Susanne. 2017. Bunpō Hattatsu Dankai-no Randomāku: Daihyō-tekina Joshi oyobi Dōshi Katsuyō-kei no Kakutoku Junjo-kara Mite [Landmark on the Stage of Grammatical Development: Looking from the Acquisitional Order of Representative Particles and Verb Inflected Forms]. Paper presented at the 43rd Meeting of the Japanese Association of Communication Disorders, Aichi Shukutoku University, Nagakute, Japan, July 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Noji, Junya. 1973–1977. Yōjiki no Gengo Seikatsu no Jittai I–IV [Reality of Early Childhood Language Life]. Hiroshima: Bunka Hyoron Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Noji, Junya, Noriko Naka, and Susanne Miyata. 2004. Japanese: Noji Corpus. Pittsburgh: TalkBank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima-Takane, Yuriko, Brian MacWhinney, Hidenori Sirai, Susanne Miyata, and Noriko Naka, eds. 1998. CHILDES for Japanese, 2nd ed. The JCHAT Project. Nagoya: Chukyo University. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, William. 1995. Language Acquisition and Language Variation: The Role of Morphology. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, William. 2001. On the Nature of Syntactic Variation: Evidence from Complex Predicates and Complex Word-Formation. Language 77: 324–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, William. 2007. Child Language: The Parametric Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, William. 2016. Compound Word Formation. In The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Linguistics. Edited by Jeffrey Lidz, William Snyder and Joseph Pater. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, William. 2021. A Parametric Approach to the Acquisition of Syntax. Journal of Child Language 48: 862–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stromswold, Karin. 1996. Analyzing Children’s Spontaneous Speech. In Methods for Assessing Children’s Syntax. Edited by Dana McDaniel, Cecile McKee and Helen Smith Cairns. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura, Masatoshi, Norio Naka, Susanne Miyata, and Yuriko Oshima. 1997. Gengo Syūtoku Kenkyū-no Tame-no Jōhō Syori Shisutemu CHILDES no Nihongo-ka [Japanese Conversion of Information Processing System CHILDES for Learning Language]. Gengo 26: 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Takeru. 2017. Root PathPP Small Clauses in English: Developmental Origins of Path-Related Constructions. JELS 34: 179–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Seiji, and Taro Kageyama. 2001. Idō to Keiro no Hyōgen [The Expressions for Motion and Path]. In Nichi–Ei Taishō: Dōshi no Imi to Kōbun [The Semantics and Constructions of Verbs: A Comparative Study of English and Japanese]. Edited by Taro Kageyama. Tokyo: Taishukan, pp. 40–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).