Abstract

Research article abstracts, the second most-read part of research papers after titles, generally follow disciplinary conventions, which are often manifested in their language use. This study analyzed lexical bundles or multi-word sequences in move texts of a one-million-word corpus of English-language medical research article abstracts, with particular attention to vocabulary levels. The most frequent lexical bundles, such as “the primary end point was”, often occurred once per text and predominantly took part in realizing a move. The coverage of the first thousand New General Service List was 63.6% for the entire corpus but was around 80% for bundles in Move 3, describing principal results, and those in Move 4, evaluating the results. Many of the sequences were research-oriented bundles, used to express research contexts. The bundles were made up of relatively accessible word items, but the sequences occurred to realize highly specific research contexts. The findings suggest that becoming familiar with the bundle may need increasing awareness of disciplinary conventions such as guideline adherences and statistical procedures. This study may offer insights on the need for learners to familiarize themselves with these bundles.

1. Introduction

In an era where information floods every aspect of academic and professional life, understanding the conventions of academic writing genres, including textual and vocabulary features, is essential (Swales 1990; Bhatia 2019; Coxhead 2020). Over the past 50 years, the academic landscape has undergone unprecedented changes, marked by a substantial increase in the number of academic papers (Hyland and Jiang 2019). This rapid growth leads to a need for learners, especially medical students, to become proficient in reading and writing research article abstracts because of the specialized nature of their disciplinary texts (Coxhead 2016; Dang 2020; Simpson 2022; Tang and Liu 2019).

Functioning as an academic, especially in English, entails engaging in a sophisticated activity framework of communication practices, particularly when constructing and disseminating scientific claims (Belcher 2016). In this system, language plays a pivotal role in forging consensus and persuading the target discourse community, a group of individuals with shared goals (Swales 1990). Academic discourse is navigated through genre texts, which are types of spoken or written texts used for specific communicative purposes (Hyon 2018, p. 3).

Written communication can be distinguished by differences in audience, purposes, content, form, style, and context (Robinson et al. 2008). Academic written language is known to be differ from academic spoken language, particularly from a vocabulary perspective (Dang et al. 2017; Coxhead and Dang 2019). Students, particularly those learning English as an additional language (EAL) need to learn the genres and conventions commonly used by community members (Brooks et al. 2023; Samraj 2016; Flowerdew 2000). This mastery is the focus of English for academic purposes (EAP) research. EAP research has two main pillars: analyzing genre-specific texts to identify communicative functions and structures (Samraj 2016), and vocabulary studies (Coxhead 2016). Both aim to aid learners’ academic development (Hyland 2016).

EAP research often involves constructing corpora to facilitate these analyses (Handford 2010). One of the central pillars of this research is genre analysis (Swales 1990). The other main pillar of EAP research, vocabulary studies, also employs corpus linguistics techniques (Nation 2005). As Storch et al. (2016) indicated, approaches to EAP are influenced by various factors, including differences in higher education systems across countries. Therefore, research-based instruction integrating multiple approaches is recommended (Hyland 2016; Storch et al. 2016). In this context, linking vocabulary quantification with rhetorical moves has been attempted by several studies (Cortes 2013; Mizumoto et al. 2017; Qi and Pan 2020; Casal and Kessler 2020). These studies illustrate the importance of combining move analysis and vocabulary studies to shed light on the features of disciplinary texts. However, to our knowledge, studies examining the vocabulary levels of word items in lexical bundles within the moves of abstracts have been scarce. Therefore, this study aimed to examine lexical bundles across moves in disciplinary research article abstracts with a focus on the vocabulary levels.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Move Analysis

As a key element of genre analysis framework, move analysis is “a text analytical method developed by Swales in 1981” (Moreno and Swales 2018, p. 40). Moves, as defined by Swales (2004, pp. 228–29), are “discoursal or rhetorical units performing coherent communicative functions in texts”, exhibiting variability in length and other features. The “revised Create a Research Space (CARS) model” (Swales 1990, p. 140), preceded by “a 4-Move Schema” (Swales 1981, p. 15), provides an analytical approach to understanding the structure of research article introductions. Swales (2004) refined the CARS model to include distinct move structures: “Move 1 Establishing a territory”, “Move 2 Establishing a niche”, and “Move 3 Presenting the present work” (pp. 230–32). These moves, denoting their communicative purposes, can be segmented into “Steps” (Swales 2004, p. 230) that realize “functional components” (Tankó 2017, p. 43). The move analysis approach has been applied extensively to examine research articles as a whole (Kanoksilapatham 2005; Maswana et al. 2015; Mizumoto et al. 2017; Nwogu 1997; Stoller and Robinson 2013) and abstracts (Hyland 2000; Kanoksilapatham 2009; Pho 2008; Salager-Meyer 1991, 1992; Tankó 2017) in various disciplines, including medicine.

2.2. Vocabulary Studies

Teaching common words in specific contexts helps learners effectively improve their vocabulary (Nation 2001). In support of learners, various word lists have been developed from collections of specialized texts (Browne 2013; Coxhead 2000; Coxhead and Hirsh 2007; Fraser 2007; Tang and Liu 2019; Wang et al. 2008). An early example is Thorndike’s word book for instructors (Thorndike 1921), which was later updated by Thorndike and Lorge (1944). The General Service List (GSL; West 1953) was subsequently compiled after extensive international discussions before and after World War II (Gilner 2011). Developed from a five-million-word corpus, the GSL is tailored for ESL/EFL learners and is organized into two groups of word families (Coxhead 2000). The GSL has frequently been used as a basis for developing other word lists, including the Academic Word List (AWL) of 570 word families prepared by Coxhead (2000).

Many studies utilize the GSL and AWL to develop specialized word lists. Coxhead and Hirsh (2007) created “the pilot science corpus” (p. 70) from textbooks and discipline-specific reading materials to compile a word list covering items not included in the GSL or AWL. Fraser (2007) quantified the vocabulary required by pharmacology students and compiled the Pharmacology Word List (PWL) from international pharmacology journal articles. Wang et al. (2008) investigated key medical vocabulary to support curriculum design and learning objectives and created a Medical Academic Word List (MAWL). To support medical students, Quero and Coxhead (2018) also compiled word type lists based on their medical corpora, which included texts from medical textbooks. These studies are just a few examples of the many that have used the GSL and AWL to examine the features of their corpora.

While the original GSL has been a foundational tool in language learning over 50 years, it has faced some criticism in recent time (Green and Lambert 2018). The approach of utilizing word families in the GSL and AWL has been the subject of some debate among researchers (Gardner and Davies 2014). In response to these discussions, the New General Service List (NGSL), developed by Browne and his colleagues (Browne 2013), was designed as a modern update of the original GSL. Consisting of 2801 high-frequency words with a clearer definition of a “word” and a higher coverage of general English (Dang and Webb 2016), the NGSL is viewed by some researchers as more suitable for EAL learners (Mizumoto et al. 2021). It has been suggested that EAL undergraduates may find the NGSL to offer a slightly easier learning curve, potentially making it more appropriate for learners compared to the GSL (Culligan 2019). Subsequently, the New Academic Word List (NAWL), consisting of 963 words, was developed to align with the NGSL along with other specific purpose word lists targeting mid-frequency range vocabulary. It is reported that the NGSL and the NAWL combined offer an average of 92% coverage of academic texts and lectures (Browne 2021, p. 4). These updates reflect ongoing efforts to improve vocabulary learning tools for English language learners.

2.3. Lexical Bundles

In vocabulary studies that support learning academic texts, research on multiword units, often referred to as ”lexical bundles”, is also significant (Nation 2022, p. 454). Corpus-based studies have identified these lexical bundles (Samraj 2016). The term lexical bundles is defined as “sequences of word forms” (Biber et al. 1999, p. 990) that occur frequently across texts, characterizing a genre or discipline. This concept has gained prominence in corpus linguistics research (Biber et al. 1999; Cortes 2004, 2013; Hyland 2008a). Lexical bundles have been studied extensively for helping learners develop a repertoire that is sensitive to disciplinary norms (Hyland 2012, p. 17).

A study by Cortes (2013) associated the identification of lexical bundles and rhetorical analysis of moves and steps in research article introductions. This approach has contributed to revealing essential relationships between forms and functions (Gray et al. 2020, p. 139), showing the values of prefabricated word sequences (Biber et al. 2004, p. 376) within the linguistic contexts that constitute “communicative events” (Swales 1990, p. 9).

Following Cortes (2013), several scholars have observed move-specific bundles (Mizumoto et al. 2017; Omidian et al. 2018; Qi and Pan 2020). Mizumoto et al. (2017) observed 25 moves across 1000 research articles as a whole in applied linguistics, identifying frequently occurring lexical bundles in each move. Omidian et al. (2018) identified lexical bundles in each move in research article abstracts from six disciplines such as mechanical engineering, physics, and applied linguistics. Their study has shown a marked difference in the frequency of bundles across disciplines, suggesting that researchers from different fields prioritize different aspects when presenting their work in academic abstracts (Omidian et al. 2018, p. 12). Qi and Pan (2020) performed move analysis according to Hanidar’s (2016) four-move structure and extracted lexical bundles, suggesting the role of lexical bundles in achieving the communicative goals of rhetorical sections.

These bundles, also known as “multi-word sequences” (Biber et al. 2004, p. 373; Mizumoto 2015, p. 30) or “recurrent word combination” (Chen and Baker 2010, p. 31), and synonymous with “n-grams” (Mizumoto 2015, p. 31; Stubbs and Barth 2003, p. 61), play a crucial role in the structure of discourse. These bundles often encapsulate shorter sequences, such as three-word bundles, within their four-word structures (Cortes 2004, p. 401; Hyland 2008a, p. 6). Although Stubbs and Barth (2003) question the status of n-grams as linguistic units and refer to them as “chains of word-forms” (p. 62), they acknowledge that these recurring sequences typify specific text genres. Traditionally, studies have focused on the prevalence of four-grams in academic writing, with phrases like “as a result of” and “in the context of” serving as organizers of specific texts (Cortes 2013, p. 34).

Hyland (2008a, p. 6) has shown that frequency counts “drop dramatically” when quantitating five-grams compared to four-grams, stating that “many four and five word strings” share three-grams. Cortes (2024, pp. 120–21) discusses “potential overlaps” such as the five-gram “as a result of the” extending beyond shorter sequences like “as a result”. Furthermore, Hyland and Jiang (2019, p. 110) have demonstrated that longer strings, such as the five-gram “at the beginning of the” which extend beyond the four-gram “the beginning of the” may offer deeper insights into the pedagogical applications of lexical bundles. Golparvar and Barabadi (2020, p. 6) analyzed “phrase frames” (p-frames; Cortes 2024, p. 105) in the discussion section of research articles and suggested that five-word p-frames could often be “more specific to a particular genre” compared to four-word p-frames. The most frequently occurring five-word p-frame was “are * likely to withdraw”, with fillers such as “less” and “more”, while the leading four-word p-frame was “the * of technology”, with fillers such as “use” and “adoption”. Liu and Chen (2022) have shown that five-word and six-word p-frames in university lectures reveal knowledge-disseminating and content-oriented features. Casal and Kessler (2020), who studied frequent p-frames in grant applications, demonstrated a strong association between the writers’ use of five-word p-frames and their rhetorical intentions. Using a bundle-driven approach, Li et al. (2020) found that five-word bundles contributed to identifying moves of PhD abstracts. These findings indicate that extended sequences such as five-grams may be useful for genre-specific language use and potentially provide linguistic patterns beneficial for learners.

2.4. Medical Research Abstracts

Abstracts are the most-read texts in a research paper, second only to titles, and serve as a vital standalone tool of communication (Hyland 2000). Scientists increasingly rely on abstracts as “short, concise, complete, and accurate sources of information” (Salager-Meyer et al. 2014, p. 222). Research paper abstracts act as “advance indicators of the content and structure of the following text” (Swales 1990, p. 179) and encapsulate the key findings of the research (Huckin and Olsen 1983, p. 359).

Structured abstracts have become the norm in medical literature, largely because of long-standing endorsements by journal editors, such as those from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) since 1993 (Salager-Meyer et al. 2014, p. 223). Salager-Meyer (1991) noted that among 77 medical research article abstracts, half were deemed “poorly structured” in adherence to “the Introduction, the Methods, the Results, and the Discussion (IMRAD) pattern” (p. 528). While Anderson and Maclean (1997) examined “unstructured abstracts” (p. 2) of medical article abstracts and identified a five-move structure, including an optional background, along with the purpose, method, results, and conclusion, Hanidar (2016), analyzing abstracts from various disciplines including medicine, advocated for a four-move structure, comprising “Move 1: Creating a research space, ” “Move 2: Describing research procedure”, “Move 3: Summarizing principal results”, and “Move 4: Evaluating results”. This four-move approach aligns with our corpus texts structured according to the journal’s guidelines. The studies of structured abstracts, notably by James Hartley, highlights the benefits of structured texts over traditional formats (Hartley 1993, p. 90). Hartley (1999, 2003) argued that structured abstracts, already used in medicine, could be “appropriate for applied ergonomics” (1999, p. 535) and could be “introduced into psychology journals” (2003, p. 366). His extensive work on structured abstracts was comprehensively reviewed by Zhang and Liu (2011), who have underscored “the advantages of structured abstracts over traditional ones” (p. 575).

In medical research publications, articles are often categorized by study design and must meet the requirements of specific reporting standards (Millar et al. 2019; Stosic 2022). High-quality reporting is facilitated by over 616 standardized reporting guidelines from the EQUATOR Network (2024), up from around 400 different sets (Millar et al. 2019, p. 150). Failure to adopt the guidelines may cause a manuscript to be regarded as inferior in quality by the ICMJE (Millar et al. 2019, p. 141). The ICMJE (2024) aims to enhance the quality and transparency of medical reporting. Their recommendations are broadly “accepted by biomedical journals” (Luo and Hyland 2019, p. 39) and play a crucial role (Millar et al. 2012, p. 393) in shaping the research writing standards. These initiatives appear to accelerate the standardization of research writing (Swales 2017, p. 249).

While there are no specific guidelines on language use (Stosic 2022), medical abstract conventions have been studied from the perspective of linguistic features. Salager-Meyer (1992) analyzed 84 medical abstracts and revealed the choice of verb tense and modality associated with rhetorical functions. Abdollahpour and Gholami (2018) gathered 1800 medical article abstracts from various journals. They identified four-word lexical bundles and classified them into general and technical groups by two qualified raters (Abdollahpour and Gholami 2018). Nam et al. (2016), who aimed to reformat unstructured abstracts into the IMRAD format, have found that linguistic features such as a five-word sequence “aim of this study was” would improve the effectiveness of abstract sentence classification. These studies have contributed to understanding the textual features of medical research article abstracts.

2.5. Application of Move Analysis and Vocabulary Research

Most recent studies have integrated move analysis and vocabulary research to envisage academic writing instruction (Casal and Kessler 2020; Li et al. 2020; Qi and Pan 2020). As a practical application, Mizumoto et al. (2017) developed an academic writing support tool called the “Academic Word Suggestion Machine (AWSuM)”. AWSuM integrates move analysis with lexical bundle analysis. John Morley’s (2023) “The Academic Phrasebank” serves as a general resource for academic writers. It offers examples of phraseological components organized according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation. This integrated approach is particularly beneficial for EAL learners. For instance, first-year medical students are shown to have difficulties in reading medical research abstracts (Shimizu 2019). It was pointed out that the boundary of methods and results sections is hard to identify when the learners face sentences like “Of the 19,114 persons who were enrolled in the trial, 9525 were assigned to receive aspirin and 9589 to receive placebo” (Shimizu 2019, p. 85). These findings echo Tardy and Jwa’s (2016) observations about the challenges of learning academic writing within a discipline, suggesting the importance of integrating genre and vocabulary research for future instructional practices.

3. The Current Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate the vocabulary levels of medical research article abstracts, especially lexical bundles across moves in disciplinary research article abstracts. This study identified lexical bundles across moves of research article abstracts and used the New General Service List (NGSL; Browne 2013) for examining the vocabulary levels of word items in the move texts and lexical bundles across moves. Our study poses the following research questions:

- Research Question 1: Which lexical bundles occur most frequently in specific moves within medical research abstracts?

- Research Question 2: What are the language features of lexical bundles across moves in medical research abstracts, such as the coverage of the NGSL, forms, and functions?

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Corpus

The data used in this study contain abstracts from the original research articles published in the years 2002–2020 in The New England Journal of Medicine (Table 1). These abstracts were selected for their “representativity, reputation, and accessibility”, according to Nwogu’s (1997, p. 121) criteria. The journal’s articles are also valued for providing regional students with essential insights into evaluating medical literature (Ogawa 2014) and understanding the practical use of language in medical writing (Jego 2012). Additionally, the journal provides official translations in the local language (Nankodo 2024).1

Table 1.

Corpus of research article abstracts.

Each article was segmented into individual sentences. Drawing on the studies by Cortes (2013, p. 36), who identified lexical bundles in research article introductions and mapped them to specific rhetorical moves, and Mizumoto et al. (2017, p. 902), who concentrated on extracting “move-specific lexical bundles”, we segmented our corpus by sections (moves). For move identification, we adopted the methodology of Qi and Pan (2020), dividing our corpus texts “based on their own headings” (p. 112)—Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions—to create subcorpora “Move 1: Creating a research space”, “Move 2: Describing research procedure”, “Move 3: Summarizing principal results”, and “Move 4: Evaluating results” according to Hanidar (2016, p. 14). This four-move approach aligns with our corpus texts structured according to the journal’s guidelines (The New England Journal of Medicine 2024).

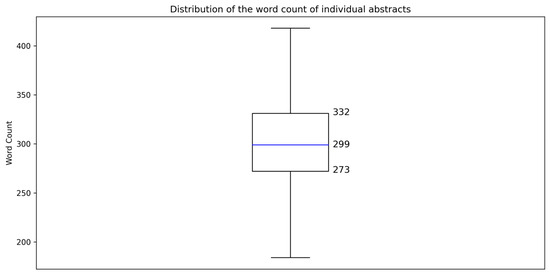

The abstract texts had 1,148,583 words, as determined using AntConc (Version 4.2.4; Anthony 2023).2 The number of words in each text was quantitated using CasualConc (Version 3.0.8; Imao 2024) and was visualized using Google Colaboratory’s Python environment (Version 3.10.12). The average word count of the abstracts was 303 words, with a standard deviation of 44 words. The distribution of abstract word counts showed that 50% of the texts fell between 273 and 332 words, with a median value of 299 words (Figure 1). These findings indicate a relatively consistent length across the corpus texts.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the word count of individual abstracts.

The most frequent words in the medical research abstract corpus included many function words, with the and of ranked the first and second (Table 2). The top 100 words accounted for over 51% of the texts (Table 3). These findings suggest that a limited set of words were quite frequently used for presenting research information. Furthermore, frequent instances of these function words and the scarcity of specialized terms suggest that studies on diverse topics were reported using similar basic vocabulary.

Table 2.

List of the most frequent words in the abstract corpus.

Table 3.

Cumulative coverage of the top 100 words in the abstract corpus.

For the analysis with the NGSL (Version 1.01, Browne 2013) and NAWL (Version 1.01, Browne et al. 2013), we used a corpus tool, CasualConc (Imao 2024). The NGSL comprises a total of 2801 words. Separate lists categorizing the top 1000 words by frequency (first NGSL), the next 1000 words (second NGSL), and the remaining 801 words (third NGSL) were available from the AntWordProfiler website (Anthony 2024) as a resource for vocabulary profiling. In addition, a supplementary list of 174 basic words, which were not included in the aforementioned three lists, and the NAWL, consisting of 963 words, were also downloaded from the same site. By combining these five lists cumulatively, the following four stopword lists were created and imported into CasualConc for coverage analysis.

- First NGSL + Supplement

- First NGSL + Second NGSL + Supplement

- First NGSL + Second NGSL + Third NGSL + Supplement

- First NGSL + Second NGSL + Third NGSL + NAWL + Supplement

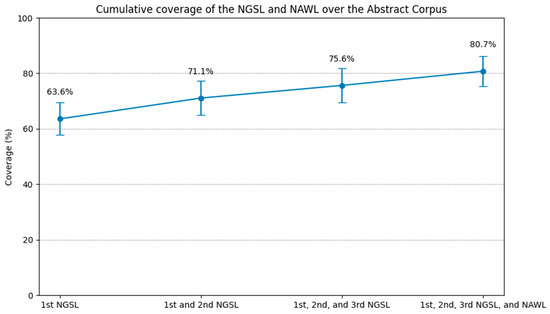

Using the stopword function of CasualConc, the word items in the lists were applied to automatically remove the target items in the preparatory step (Sarica and Luo 2021). To determine the covered word count, the word count after removal was subtracted from the total word count of the texts using Microsoft Excel (Version 2406). This procedure was repeated using the aforementioned stopword lists one by one, and the results were visualized using Python 3.10.12 in the Google Colaboratory environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative coverage of the NGSL and NAWL over the abstract corpus.

The first 1000 words plus the supplementary 172 words covered 63.6% of the entire corpus, 71.1% with the first 2000 words, and 75.6% with the addition of the remaining 801 words. The NAWL yielded an additional 5.1% coverage, reaching a total coverage of 80.7%.

The comparison with previous studies showed that while the NGSL and NAWL provided greater coverage in other texts, they did not cover as much of our medical research article abstract corpus. The 2801 high-frequency words from the NGSL provided between 95% and 97% overall text coverage of English reading passages of Japan’s national university entrance examination from 2015 to 2019 (MacDonald 2019, p. 22). The NGSL and NAWL combined to provide an average coverage of 84.8% of a 7.8-million-word civil engineering research article corpus (Gilmore and Millar 2018). In contrast, the coverage of our medical research abstract corpus was lower, indicating its highly specialized vocabulary level.

4.2. Data Processing

Hyland and Jiang (2019, p. 111), following Cortes (2015, p. 205), argued that while bundle frequencies are often standardized per 10,000 words, this normalization may result in higher instances of bundles in smaller corpora. This potentially raises the frequency of word combinations that are not usually common enough to surpass the threshold. Consequently, phrases that are infrequently used might still be classified as lexical bundles after normalization (Hyland and Jiang 2019, p. 111). To mitigate this issue, we adopted multi-step approach to bundle identification, drawing on methodologies mainly from Cortes (2004), Hyland (2008a), Hyland and Jiang (2019), and Lake and Cortes (2020). Our initial step was to ensure that each abstract in our corpus had broadly similar word count in English and quantitated the abstracts (Figure 1).

Recent studies have shown that five-word bundles are likely to realize rhetorical intentions (Casal and Kessler 2020) and represent a particular genre (Golparvar and Barabadi 2020). Nam et al. (2016) studied several linguistic features for classifying unstructured abstract sentences into the IMRAD format. They found that n-grams produced the best results. However, increasing the value of “n” in n-grams did not necessarily improve classification performance. Better results were obtained with sequences such as five-grams and six-grams (Nam et al. 2016). Therefore, the present study focused on identifying five-word bundles. Initially, following the criteria for five-word p-frames set by Casal and Kessler (2020), five-word bundles appearing in at least five different texts with a raw frequency of five were identified. This was achieved with the N-Gram function of AntConc (Version 4.2.4, Anthony 2023). This process revealed 433 bundles in Move 1, 1901 in Move 2, 3349 in Move 3, and 840 in Move 4. Given the size of the move corpora (Table 1), we followed the idea of Bestgen (2020) to avoid the potential bias of smaller corpora yielding more bundles by using higher frequency thresholds. For further analysis, a threshold of appearing in at least five different texts with a raw frequency of 10 was applied.

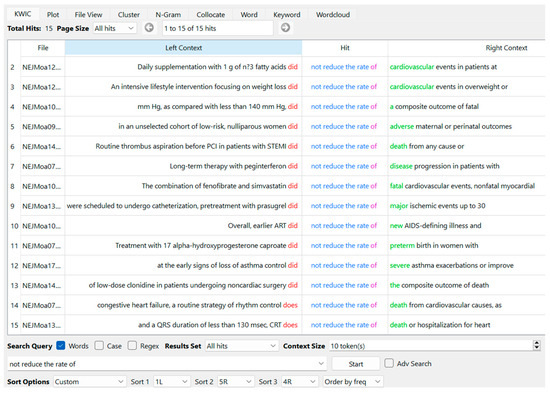

We followed the approach of Hyland and Jiang (2019, p. 109), which involved manually removing bundles containing text-dependent noun phrases, such as “the United States”. However, we retained phrases such as “the primary end point”. This is because primary end points serve as key measures of study outcomes, as noted by Qi and Pan (2020, p. 115), and because of the substantial instructional value of items conforming to disciplinary requirements (Salager-Meyer et al. 2014; Luo and Hyland 2019; Millar et al. 2019). This strategy aimed at extracting bundles while preserving “the observation of language in use” (Sinclair 1991, p. 39) as much as possible. In this process, we followed Durrant’s (2017, p. 170) study for the exclusion of “punctuation and numerals”. We utilized AntConc’s feature for automatically omitting punctuation and digits (Viana and O’Boyle 2022, p. 119). Then, we manually excluded “overlapping word sequences” (Chen and Baker 2010, p. 33) with reference to the procedure outlined by Qi and Pan (2020, p. 113). This was done by placing the extracted bundles on spreadsheets (Microsoft Excel) and examining AntConc’s concordance lines. For example, the bundle “did not reduce the rate” showed 13 times in Move 4; all instances were from the six-word string “did not reduce the rate of”. The five-word string “not reduce the rate of” occurred 15 times, including two instances of a six-word sequence, “does not reduce the rate of” (Figure 3). Therefore, the bundle “not reduce the rate of” was listed.

Figure 3.

Example screen of AntConc showing “not reduce the rate of” as the node word with 13 instances of “did” and 2 instances of “does” at L1 or one word to the left (order by frequency of L1).

The structures of the bundles were examined with reference to Biber et al. (1999, pp. 1014–24). We also referred to the procedure by Hyland (2008a, p. 10) and examples by Qi and Pan (2020, pp. 125–28). Biber et al. (1999) presented taxonomies for lexical bundles in academic prose, providing example bundles embedded in sentences. Hyland (2008a), citing Biber et al. (1999), also gave example bundles in sentences. By comparing our identified bundles to those examples, we classified our bundles accordingly. Bundles that did not fall into the categories based on the examples, such as “than in the group that”, were labeled as others.

The functions of the bundles were analyzed based on Hyland’s (2008a) classification. Hyland (2008a, p. 13) explained that research-oriented bundles “help writers to structure their activities and experiences of the real world”. Accordingly, our observation included both less specific items such as “with a use of the” and highly specific combinations such as “hazard ratio confidence interval ci” in this category. Text-oriented bundles are “concerned with the organisation of the text and its meaning as a message or argument”, and participant-oriented bundles are “focused on the writer or reader of the text” (Hyland 2008a, pp. 13–14). Based on these definitions, bundles such as “associated with an increase in” were differentiated from research-oriented sequences such as “associated with an increased risk” in classification.

5. Results

5.1. Lexical Bundles in Move Texts

5.1.1. Frequencies

We found a total of 1286 five-word lexical bundles in medical research abstracts: 71 in Move 1, 305 in Move 2, 848 in Move 3, and 62 in Move 4. The most frequently occurring bundles are shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, and all 1286 bundles are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A. The most frequent five-word bundle “the efficacy and safety of” appeared 98 times in Move 1 with a range of 96; “the primary end point was” in Move 2 occurred 708 times in 705 texts. The bundle “confidence interval ci to p” occurred 681 times in 681 texts in Move 3. The original sequence was “confidence interval [CI], n# to n#; P<n#” as shown in an example sentence below, after the exclusion of punctuation and digits (Durrant 2017, p. 170; Viana and O’Boyle 2022, p. 119). In Move 4, the most frequently occurring bundle “associated with an increased risk” appeared 59 times in 56 texts. These instances indicate that many high-frequency sequences were used only once per abstract. The raw frequency and range values suggest a consistent use of bundles across the corpus texts.

Table 4.

Most frequent five-word lexical bundles in Move 1.

Table 5.

Most frequent five-word lexical bundles in Move 2.

Table 6.

Most frequent five-word lexical bundles in Move 3.

Table 7.

Most frequent five-word lexical bundles in Move 4.

- 1.

- In total, 457 patients (22.8%) in the surgery group and 539 patients (26.4%) in the control group died (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68 to 0.87; p < 0.001).

While the top bundle in Move 1 did not exceed a raw frequency of 100 (Table 4), the bundle “the primary end point was” in Move 2 was notably prevalent and was found 708 times in 705 texts (Table 5). The prevalence of this bundle indicates common practices in the disciplinary research where the sequence is used to define main variable or parameter to be measured. The combination reflects a highly technical aspect, setting the stage for the methodological framework although the individual lexical items—“the”, “primary”, “end”, “point”, and “was”—have been found to be accessible from a vocabulary perspective (Asano and Fujieda 2024). For instance, the following example illustrates the essential role of such lexical bundles in presenting the main parameters of a study in a succinct manner:

- 2.

- The primary end point was histologic improvement in the 10-mg group as compared with the placebo group.

The bundle “confidence interval ci to p” also occurred as high as 681 times in 681 texts in Move 3, as represented by the fragment “95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68 to 0.87; p < 0.001” in the abovementioned example sentence. This indicates a noticeably consistent appearance in statistical contexts. The abbreviation “CI” indicates multiple occurrences of the term “confidence interval” within the text. The consistent appearance of the five-word bundle “confidence interval ci to p” across various texts suggests its routine use in statistical analyses within medical research. This bundle helps in presenting critical statistical information in a uniform manner, which facilitates clear and comparable interpretations of study results. For instance, the text uses this bundle to report the statistical measures of effect and significance, such as the confidence interval and a p-value. The text illustrates the bundle’s role in showing quantitative aspects of the study findings. This uniform application of statistical terminology ensures that the findings are communicated in a precise and standardized format that can be easily understood and evaluated by others in the scientific community. In Move 4, high-frequency bundles contained word items related to discussing changes or statistical results, such as “associated with an increased risk” and “there was no significant difference”, as described later in Section 5.1.3. Structure and Functions of Lexical Bundles.

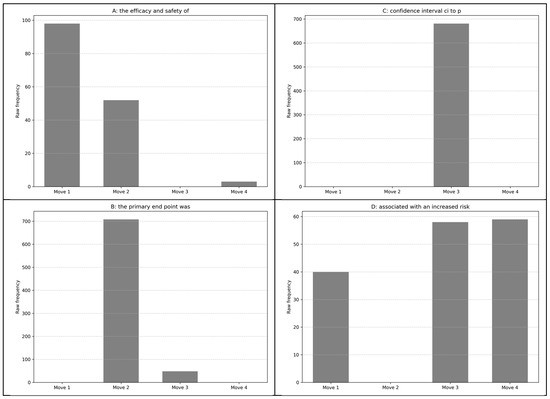

Figure 4 shows the frequency of the leading bundles in each move. This indicates that the individual bundles have unique roles in the texts, as shown by Nam et al. (2016). For example, Panel A in Figure 4 shows that “the efficacy and safety of” occurred most often in Move 1. Example concordance lines indicated that the bundle took the technical part of the sentence for realizing study objectives.

Figure 4.

Frequency of move-specific most frequent five-word bundles. (A): the efficacy and safety of; (B): the primary end point was; (C): confidence interval ci to p; (D): associated with an increased risk.

- 3.

- We assessed the efficacy and safety of a paclitaxel-coated balloon in this setting.

Panel B in Figure 4 indicates that the instances of “the primary end point was” were dominant in Move 2. The bundle “confidence interval ci to p” only occurred in Move 3 (Panel C), indicating its essential function for presenting statistical findings. The sequence “associated with an increased risk” was rather exceptional as it was common in Moves 3 and 4 and also occurred in Move 1. However, the instances in these moves were below 60; therefore, the bundle may have been used only when the bundle fitted appropriately in realizing the authors’ intentions. The findings suggest that these combinations may have pedagogical value. Becoming aware of where these bundles typically appear and their function within the abstracts could greatly enhance learners’ familiarity with disciplinary research article abstracts.

5.1.2. The NSGL Coverage of the Bundles

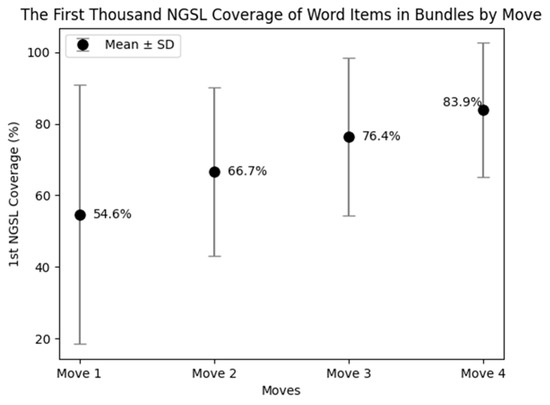

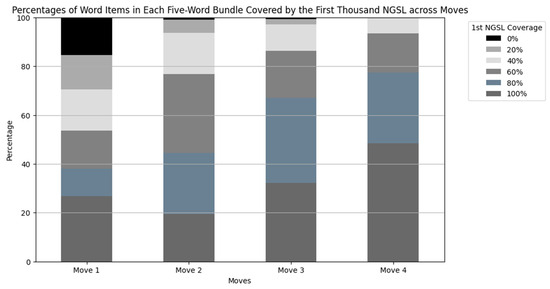

The coverage of the first thousand NGSL varied across the moves (Figure 5). The word list covered up to 83.9% of the word items in bundles occurred in Move 4, followed by 76.4% in Move 3, 66.7% in Move 2, and 54.6% in Move 1. These variations are explicitly depicted in Figure 6. This figure shows the percentages of word items in each five-word bundle covered by the word list. For instance, a five-word bundle was classified as 100% when all five individual word items were covered by the word list. It was marked as 80% when four out of the five word items were covered. When none of the word items were covered by the word list, the bundle was marked as 0%.

Figure 5.

The first thousand NGSL coverage of word items in lexical bundles by move.

Figure 6.

Percentages of word items in each five-word bundle covered by the first thousand NGSL across moves. From the bottom, bars in dark gray represent 100%, those in blue gray represent 80%, those in dim gray represent 60%, those in silver represent 40%, those in light gray represent 20%, and those in black represent 0%.

In Move 4, about a half of the bundles consisted of words in the first NGSL only, such as “with an increased risk of”, “did not result in a”, and “was not associated with a”. The coverage of the word list was 40% or greater in all the bundles in Move 4. These bundles were often used for discussing the changes or statistical results.

On the other hand, 15.5% of the bundles in Move 1 contained no word items covered by the word list, such as “hepatitis c virus hcv infection” (Table 8). Additionally, 14.1% of the sequences had only one word item covered by the word list, such as the fourth most frequently occurring bundle “low density lipoprotein ldl cholesterol” (Table 4). These combinations were used to introduce the research area as described in the following Section 5.1.3.

Table 8.

Concordance lines with the node word of “hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection” in Move 1.

Move 3 also had many bundles comprised of words covered by the word list, but they were different from the bundles in Move 4 in that most of the bundles in Move 3 were used to accurately report results with numerals, such as “percent confidence interval to p”, “of the patients in the”, and “than in the placebo group” (Table 6). Although each word item was rather accessible, the bundles appeared to convey information specific to the research (Table 9).

Table 9.

Concordance lines with the node word of “of the patients in the” in Move 3.

Similar tendencies were seen in Move 2, where many frequent bundles, such as “the primary end point was” and “we randomly assigned patients with”, were embedded in the context of research as shown in the next section. There were 31 instances of the first-person pronoun, and they were generally used to build research-oriented bundles. Here again, while the individual word items seemed accessible, the combined use of the words tended to reflect the disciplinary conventions.

5.1.3. Structure and Functions of Lexical Bundles

The texts showed that main structures of bundles were noun phrases, similar to the findings in academic written discourse such as those by Biber et al. (1999), Hyland (2008a), and Golparvar and Barabadi (2020). Noun phrases most often occurred in Move 1 (Table 10). Many were used for presenting disciplinary content words like “low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol” and “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)” for setting the scene:

Table 10.

Principal structures of bundles across moves (%).

- 4.

- Non–small-cell lung cancer with sensitive mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is highly responsive to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib, but little is known about how its efficacy and safety profile compares with that of standard chemotherapy.

On the other hand, of-phrase fragments such as “a significantly lower rate of” appeared frequently in expressing the conclusions (Move 4). Most sequences were part of descriptions used to indicate comparisons:

- 5.

- In children with chronic hepatitis B, 52 weeks of treatment with lamivudine was associated with a significantly higher rate of virologic response than was placebo.

The results (Move 3) made by far the most use of bundles beginning with a prepositional phrase. Such items included “of the patients in the”, “in the medical therapy group”, and “as compared with the placebo”. These were most likely used to describe classifications and comparisons:

- 6.

- At 3 years, the criterion for the primary end point was met by 5% of the patients in the medical-therapy group, as compared with 38% of those in the gastric-bypass group (p < 0.001) and 24% of those in the sleeve-gastrectomy group (p = 0.01).

Verb phrases were most used for describing methods (Move 2). These included passive bundles preceded by “patients”, such as “patients were randomly assigned to”, and constructions with the presence of the first-person pronoun, such as “we evaluated the efficacy of”. The following is an example with the first-person pronoun:

- 7.

- We conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous remdesivir in adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection.

There were very few usages of the anticipatory it structure among five-word bundles. The only sequence we found was “it is not known whether” in Move 1:

- 8.

- It is not known whether infants conceived with use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection or in vitro fertilization have a higher risk of birth defects than infants conceived naturally.

Many sequences were research-oriented bundles (Table 11). These bundles were used to introduce the research area in Move 1, such as “coronary artery bypass grafting cabg”. The specific word combinations were used and defined to engage readers and direct their focus to the research areas early in the abstracts.

Table 11.

Distribution of bundle functions by move (%).

- 9.

- Some studies suggest that combination antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection increases the risk of premature birth and other adverse outcomes of pregnancy.

Almost all bundles were shown to describe study-related matters in Move 2. They were used to describe “location—indicating time/place” (Hyland 2008a, p. 13) such as “at the time of the”, procedure such as “we randomly assigned to a”, and quantification such as “a scale from to with”. These bundles functioned to contextualize the research processes.

- 10.

- Each videotape was rated in various domains of technical skill on a scale of 1 to 5 (with higher scores indicating more advanced skill) by at least 10 peer surgeons who were unaware of the identity of the operating surgeon.

Although the results section (Move 3) was also predominantly composed of research-oriented bundles, it showed a few participant-oriented bundles like “were more likely to be”. Such bundles were accompanied by specific numbers, or values, and results of statistical analyses. The sequences helped to support the summarized data to describe major findings.

- 11.

- According to univariate analysis, patients with S. marcescens bacteremia stayed in the surgical intensive care unit longer than controls (13.5 vs. 4.0 days, p < 0.001), were more likely to have received fentanyl in the surgical intensive care unit (odds ratio, 31; p < 0.001), and were more likely to have been exposed to two particular respiratory therapists (odds ratios, 13.1 and 5.1; p < 0.001 for both comparisons).

Move 4 showed outstanding differences in that it had various text-oriented bundles. They were related to changes seen in the studies in relation to certain interventions, such as “associated with an increase in” or indicating statistical results, such as “no significant difference in the”. These bundles helped briefly discuss and conclude the study findings in abstract texts.

- 12.

- Knowledge of the fetal oxygen saturation is not associated with a reduction in the rate of cesarean delivery or with improvement in the condition of the newborn.

The instances of “participant-oriented bundles” (Hyland 2008a, p. 14) were fewer than expected, indicating a preference for diverse word combinations to construct participant-oriented discourse. Specifically, the bundle “may reduce the risk of” and “may increase the risk of”, which incorporate the modal “may”, were extracted only in Moves 1 and 4, with more frequent occurrences in Move 1. The bundles such as “more likely to have” and “more likely to be” were found in Moves 3 and 4. These bundles were consistently paired with quantifiers like “more” or “less”, likely reflecting the authors’ intention to contextualize and interpret their results within comparative frameworks.

Despite the simplicity of the individual lexical items such as prepositions, pronouns, and verbs like “know”, their combination into bundles plays significant roles in structuring academically contextualized sequences. This synergy illustrates how domain-specific language is formulated from simple components to convey complex ideas, which is crucial for precise communication in scientific contexts.

6. Discussion

Our main purpose in this study was to examine the lexical bundles across moves in the research article abstracts with a focus on the vocabulary levels. We aimed to address the two research questions. Our findings on the most frequently occurring five-word bundles in each move revealed many sequences similar to the 185 bundles extracted by Qi and Pan (2020) but showed a substantial difference in numbers. We identified 1286 five-word lexical bundles in total; about two-thirds of them occurred in Move 3, one-quarter in Move 2, and the remaining bundles were in either Move 1 or Move 4.

Our findings on the structures and functions of bundles support studies by Biber et al. (1999) and Hyland (2008a), which showed that the main structures of bundles are noun phrases, with the majority of sequences being research-oriented bundles. We have extended these studies by examining the coverage of the first thousand NGSL for bundles in each move. We found fluctuations in the coverage of the first thousand NGSL among bundles in different moves.

Although the word list covered around 80% of the word items in the bundles in Move 3 and Move 4, differences were seen in the forms and functions of the bundles in these moves. In Move 3, noun-phrase bundles accounted for about 50%, and many sequences were used to summarize research findings, describing essential data and presenting statistical information. In Move 4, however, about one-third of the bundles were verb phrases, and text-oriented bundles comprised 40%. The bundles in Move 2 were made up of word items in which the coverage of the word list was slightly lower than in the Move 3 bundles and were predominantly research-oriented. The first-person pronoun used in the Move 2 bundles was mainly part of research-oriented sequences. These pronouns were used to describe the researchers’ adherence to disciplinary requirements (Hyland 2008a). Although many five-word lexical bundles were built with basic word items, the combined sequences often realized the contexts of research. Becoming familiar with these bundles may require learners to raise their awareness of the contextual knowledge of formal and rhetorical features of the genre texts (Tardy 2009). These findings may have implications for teaching specific lexical bundles in educational settings especially for novice learners such as undergraduate medical students.

Our study has several limitations. One is that we identified lexical bundles primarily based on frequency information. Nation (2001) argued that items with higher frequency are used more often and thus have educational value. Biber et al. (2004) suggested that examination of frequently occurring bundles can reveal the real-world use of multi-word sequences. However, there are counterarguments. Flowerdew (2012), citing Widdowson (1991) and Cook (1998), pointed out “the danger of equating frequency with pedagogic relevance” (p. 191). This is pertinent because Simpson-Vlach and Ellis (2010) argued that “sequences such as ‘on the other hand’ and ‘at the same time’ are more psycholinguistically salient than sequences such as ‘to do with the’, or ‘I think it was’” (p. 490). They created an academic formula list by taking into consideration the psycholinguistic salience in addition to frequency count.

A notable finding from Graetz (1982) is that there is a high correlation between the disciplines in which abstracts appear in journals and lecturers’ reliance on abstracts, along with their belief that students should be taught how to read abstracts (p. 26). This perspective is supported by Nation (2022), who emphasized that the characteristics and usage of language items should substantially influence teaching and learning strategies (p. 435). However, our study primarily focused on analyzing the features of lexical bundles in abstract texts, without exploring into classroom applications.

In one of our prior studies, we used a seven-year segment of our corpus to develop the Medical English Education Support System (MEESUS), which was implemented in language courses at a university (Asano et al. 2022a). The complexity of contextual meanings of lexical items in disciplinary discourse has been pointed out, such as the term “clinical” in “clinical trials” and “a clinical decision” (Coxhead 2016, p. 179). To tackle this difficulty, around 100 first-year “genre students” (Hyland 2008a, p. 20), with an average TOEFL ITP score of 475.04, engaged with the MEESUS in our previous study (Asano et al. 2022a). They used its concordance tool to explore language items and reported their insights on terms like “mean” for an average and “case” for a subject, gaining awareness of their their usage in the academic contexts.

In another study, fourth-year medical students, averaging a TOEFL ITP score of 455.9, used disciplinary “guidelines” (Millar et al. 2019, p. 150) to examine and summarize research abstracts (Asano et al. 2022b). Despite different thoughts about “learner-directed corpus projects” (Ballance and Coxhead 2022, p. 412), such activities have been shown to enhance linguistic “awareness” and “tolerance”, preparing learners for real-world applications (Cook 2010, pp. 117–18). Simpson-Vlach and Ellis (2010) suggested that “organization of constructions according to academic needs and purposes is essential” in transforming language resources into effective tools for pedagogy (p. 510).

In the future, it will be necessary to expand upon these prior works by conducting classroom activities. Such activities may include observing lexical bundles and raising learners’ awareness of the form and function of the sequences in context.

Many studies have shown the linguistic features of lexical items in disciplinary texts (Biber et al. 1999; Cortes 2004, 2013; Hyland 2008a, 2008b; Mizumoto et al. 2017; Omidian et al. 2018; Qi and Pan 2020; Li et al. 2020). These studies have aimed to address the challenges faced by “novice and seasoned scientists” (Kanoksilapatham 2005, p. 288). This includes the notion that becoming proficient in a language requires an awareness of the preferred word sequences used by experts (Hyland 2008b, p. 44). Our study found similar results regarding five-word lexical bundles in the moves of research article abstracts (Biber et al. 1999; Hyland 2008a). Our examination revealed that although the bundles identified in our texts consisted of relatively accessible individual vocabulary items, their combined sequences reflected the context of research and adherence to the required academic conventions. Several difficulties in learning multiword items have been pointed out (Boers 2020). Becoming familiar with these patterns could assist students in “learning productive chunks of language” (Reppen and Olson 2020, p. 177). In helping learners succeed in their learning contexts (Tribble 2017), the findings in this study suggest that raising awareness of specific lexical bundles can be beneficial for aiding students in joining their disciplinary communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and M.F.; text processing and corpus compilation K.H.; analyses, M.A., K.H. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., K.H. and M.F.; funding acquisition, M.A. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research awarded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) grant numbers 23K02800 and 18K02966. The APC was funded by the Author Voucher discount code (0736e63e42811a20).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data from our corpus are currently not accessible to the public. However, data used in this study can be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. We also thank the academic editors of Languages for their generous assistance throughout the review process. The authors are especially grateful to Junichiro Taki, a fourth-year medical student at Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University, for his invaluable assistance in data processing and corpus compilation. Any remaining errors are our responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

All lexical bundles identified are listed by move in the order of frequency (Table A1). The abbreviations are as follows: Freq stands for frequency, 1st N for the coverage of the first NGSL, NP for noun phrase, VP for verb phrase, PP or prepositional phrase, Ant it for anticipatory it structure, Res for research-oriented, Text for text-oriented, and Participant for participant-oriented bundles.

Table A1.

All lexical bundles identified by move, frequency, first NGSL coverage, structure, and function.

Table A1.

All lexical bundles identified by move, frequency, first NGSL coverage, structure, and function.

| Move | Bundles | Freq | Range | 1st N | Structure | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | the efficacy and safety of | 98 | 96 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | non small cell lung cancer | 47 | 47 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | the safety and efficacy of | 45 | 45 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | low density lipoprotein ldl cholesterol | 42 | 42 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | with an increased risk of | 42 | 41 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 1 | human immunodeficiency virus type hiv | 40 | 40 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 1 | associated with an increased risk | 40 | 39 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 1 | in patients with type diabetes | 37 | 32 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 1 | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease copd | 31 | 31 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | coronary artery bypass grafting cabg | 31 | 31 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | it is not known whether | 31 | 31 | 100 | Ant it | Text |

| 1 | small cell lung cancer nsclc | 30 | 30 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | human immunodeficiency virus hiv infection | 28 | 28 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | we tested the hypothesis that | 27 | 27 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 1 | little is known about the | 26 | 26 | 100 | VP | Participant |

| 1 | out of hospital cardiac arrest | 23 | 21 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | are at high risk for | 22 | 22 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 1 | human epidermal growth factor receptor | 22 | 22 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | we conducted a study to | 22 | 22 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 1 | years of age or older | 21 | 20 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 1 | we sought to determine whether | 20 | 20 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 1 | hepatitis c virus hcv infection | 19 | 19 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | of human immunodeficiency virus hiv | 19 | 19 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 1 | influenza a h n virus | 18 | 18 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | high density lipoprotein hdl cholesterol | 17 | 17 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | is a major cause of | 17 | 17 | 100 | VP | Participant |

| 1 | the human immunodeficiency virus hiv | 17 | 17 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | acute respiratory distress syndrome ards | 16 | 16 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | hepatitis c virus hcv genotype | 16 | 16 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | in patients with atrial fibrillation | 16 | 15 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 1 | to reduce the risk of | 16 | 16 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 1 | we conducted a randomized trial | 16 | 16 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 1 | are at increased risk for | 15 | 15 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 1 | has been shown to reduce | 15 | 15 | 100 | VP | Text |

| 1 | proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type | 15 | 15 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | transcatheter aortic valve replacement tavr | 15 | 15 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | we evaluated the effect of | 15 | 15 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 1 | with hepatitis c virus hcv | 15 | 15 | 20 | PP | Res |

| 1 | epidermal growth factor receptor egfr | 14 | 14 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | has been shown to be | 14 | 13 | 100 | VP | Text |

| 1 | may reduce the risk of | 14 | 14 | 100 | VP | Participant |

| 1 | we evaluated the efficacy of | 14 | 14 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 1 | we evaluated the safety and | 14 | 14 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 1 | with human immunodeficiency virus hiv | 14 | 14 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 1 | diffuse large b cell lymphoma | 13 | 9 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | st segment elevation myocardial infarction | 13 | 13 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | the treatment of patients with | 13 | 13 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 1 | allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 12 | 12 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | angiotensin converting enzyme ace inhibitors | 12 | 12 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | in patients with heart failure | 12 | 12 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 1 | primary percutaneous coronary intervention pci | 12 | 12 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | the most common cause of | 12 | 12 | 100 | NP | Participant |

| 1 | we assessed the efficacy and | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 1 | cardiovascular events in patients with | 11 | 10 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 1 | continuous positive airway pressure cpap | 11 | 11 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator | 11 | 11 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | has not been well studied | 11 | 11 | 100 | VP | Participant |

| 1 | methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus mrsa | 11 | 11 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | patients with chronic kidney disease | 11 | 9 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | patients with relapsed or refractory | 11 | 10 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | patients with type diabetes mellitus | 11 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 1 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus | 11 | 11 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 1 | the long term effects of | 11 | 11 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 1 | the risk of cardiovascular events | 11 | 11 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 1 | we examined the effect of | 11 | 11 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 1 | with acute myeloid leukemia aml | 11 | 11 | 20 | PP | Res |

| 1 | data are lacking on the | 10 | 10 | 100 | VP | Participant |

| 1 | graft versus host disease gvhd | 10 | 10 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 1 | mutations in the gene encoding | 10 | 10 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 1 | of death from any cause | 10 | 10 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 1 | patients with severe aortic stenosis | 10 | 10 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the primary end point was | 708 | 705 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | at a dose of mg | 325 | 252 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned patients with | 294 | 294 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were randomly assigned to receive | 285 | 278 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | primary end point was the | 278 | 277 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | per kilogram of body weight | 211 | 211 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome was the | 190 | 190 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | in a ratio to receive | 183 | 178 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | randomly assigned in a ratio | 151 | 147 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | patients were randomly assigned to | 149 | 148 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | randomized double blind placebo controlled | 134 | 134 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | assigned in a ratio to | 127 | 123 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | to with higher scores indicating | 125 | 105 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | years of age or older | 125 | 121 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | were randomly assigned in a | 124 | 120 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | double blind placebo controlled trial | 120 | 120 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | was a composite of death | 93 | 88 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome was a | 90 | 90 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | outcome was a composite of | 79 | 77 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned patients to | 79 | 79 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | per square meter of body | 75 | 75 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a randomized double | 72 | 72 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary efficacy end point | 71 | 70 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned patients who | 70 | 70 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | secondary end points included the | 53 | 53 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | with the use of a | 53 | 52 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | with the use of the | 53 | 50 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the efficacy and safety of | 52 | 51 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | scores range from to with | 51 | 42 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | of death from any cause | 50 | 47 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction | 50 | 50 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 2 | with higher scores indicating more | 45 | 43 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | a total of patients with | 44 | 44 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | between the ages of and | 44 | 43 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | to years of age with | 44 | 43 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the primary end points were | 43 | 43 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a double blind | 43 | 43 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | in this randomized double blind | 41 | 41 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | mg per deciliter mmol per | 40 | 29 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome measure was | 39 | 39 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | to years of age who | 39 | 39 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a multicenter randomized | 38 | 38 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | double blind placebo controlled phase | 37 | 37 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | of death from cardiovascular causes | 37 | 33 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the primary efficacy outcome was | 37 | 37 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a double blind placebo controlled | 34 | 33 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | change from baseline in the | 34 | 31 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome was death | 34 | 34 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | was death from any cause | 34 | 34 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were to years of age | 34 | 33 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were randomly assigned to undergo | 33 | 33 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | ml per minute per m | 31 | 23 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | this double blind placebo controlled | 31 | 31 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | at a dose of µg | 30 | 24 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | forced expiratory volume in second | 30 | 30 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in a randomized double blind | 30 | 30 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | on the basis of the | 29 | 29 | 100 | PP | Text |

| 2 | outcome was the rate of | 29 | 27 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were years of age or | 29 | 29 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | assessed with the use of | 28 | 27 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | end point was the percentage | 28 | 28 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the presence or absence of | 28 | 28 | 60 | NP | Text |

| 2 | we randomly assigned patients in | 28 | 28 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | assigned to receive mg of | 27 | 26 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | or death from cardiovascular causes | 26 | 24 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the primary safety end point | 26 | 24 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | trial we assigned patients with | 26 | 26 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | double blind randomized placebo controlled | 25 | 25 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | mg per day or placebo | 25 | 24 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | nonfatal myocardial infarction nonfatal stroke | 25 | 24 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 2 | double blind trial we randomly | 24 | 24 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | placebo controlled trial we randomly | 24 | 24 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | on the modified rankin scale | 23 | 20 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | to receive either mg of | 23 | 23 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a total of patients were | 22 | 22 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | end point was death from | 22 | 22 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | placebo controlled phase trial we | 22 | 22 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the change from baseline to | 22 | 21 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the two primary end points | 22 | 22 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a randomized trial | 22 | 22 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | weight in kilograms divided by | 22 | 22 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | divided by the square of | 21 | 21 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | patients with moderate to severe | 21 | 21 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | performed with the use of | 21 | 21 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | randomized double blind trial we | 21 | 21 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | secondary end points included overall | 21 | 21 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the patients were randomly assigned | 21 | 21 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | was a sustained virologic response | 21 | 21 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | weeks after the end of | 21 | 21 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | assigned patients with type diabetes | 20 | 20 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | at a dose of or | 20 | 17 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | composite of death myocardial infarction | 20 | 19 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | end point was a sustained | 20 | 20 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | health related quality of life | 20 | 20 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in the score on the | 20 | 18 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal | 20 | 20 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | out of hospital cardiac arrest | 20 | 18 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned adults with | 20 | 20 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | children to months of age | 19 | 19 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | end points were overall survival | 19 | 19 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | free survival and overall survival | 19 | 19 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in the intention to treat | 19 | 18 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | on a scale of to | 19 | 17 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | or placebo in addition to | 19 | 19 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | outcome was the composite of | 19 | 18 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | to mg per deciliter to | 19 | 16 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | a time to event analysis | 18 | 15 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | at a dose of to | 18 | 16 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | double blind phase trial we | 18 | 18 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | ejection fraction of or less | 18 | 18 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | randomly assigned to one of | 18 | 18 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary composite end point | 18 | 18 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | was the composite of death | 18 | 17 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | after the end of treatment | 17 | 17 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | at the end of the | 17 | 16 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | end point was the composite | 17 | 15 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | hours after the onset of | 17 | 17 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in this phase trial we | 17 | 17 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | investigator assessed progression free survival | 17 | 17 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | mg per kilogram every weeks | 17 | 10 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | non small cell lung cancer | 17 | 16 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients were assigned to receive | 17 | 15 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | progression free survival and overall | 17 | 17 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a retrospective cohort | 17 | 17 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were randomly assigned to a | 17 | 17 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a left ventricular ejection fraction | 16 | 16 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | a scale from to with | 16 | 15 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | key secondary end point was | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | mg twice daily or placebo | 16 | 15 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | or death from any cause | 16 | 16 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | randomization was stratified according to | 16 | 16 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | randomized placebo controlled double blind | 16 | 16 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | secondary end points were the | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the between group difference in | 16 | 14 | 100 | NP | Text |

| 2 | the coprimary end points were | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the median follow up was | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary end point of | 16 | 16 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the safety and efficacy of | 16 | 16 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the time to the first | 16 | 14 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | to with lower scores indicating | 16 | 14 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted an open label | 16 | 16 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we enrolled patients who had | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | who had not previously received | 16 | 16 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a composite of death myocardial | 15 | 15 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | according to the intention to | 15 | 15 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | analyzed with the use of | 15 | 13 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | during the period from through | 15 | 14 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | end points were progression free | 15 | 15 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | every weeks for up to | 15 | 14 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in this multicenter double blind | 15 | 15 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | of to mg per deciliter | 15 | 13 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | open label phase trial we | 15 | 15 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the composite of death from | 15 | 15 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the percentage of patients with | 15 | 13 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the primary safety outcome was | 15 | 15 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a composite of cardiovascular death | 14 | 12 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | after the end of therapy | 14 | 14 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | as compared with placebo in | 14 | 14 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | at the time of the | 14 | 13 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | death myocardial infarction or stroke | 14 | 14 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | free survival as assessed by | 14 | 14 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | in a ratio to undergo | 14 | 14 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | mg per kilogram per day | 14 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | or hospitalization for heart failure | 14 | 14 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients who had a response | 14 | 13 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | to years of age and | 14 | 14 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | was the percentage of patients | 14 | 14 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we conducted a randomized controlled | 14 | 14 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned women with | 14 | 14 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | a composite of death or | 13 | 13 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | and randomly assigned them to | 13 | 13 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | bmi the weight in kilograms | 13 | 13 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | boundary of the confidence interval | 13 | 13 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | end point was disease free | 13 | 13 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | end point was the first | 13 | 9 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | in a double blind fashion | 13 | 13 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | in this double blind phase | 13 | 13 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | key secondary end points were | 13 | 13 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | of body surface area and | 13 | 13 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | patients with hcv genotype infection | 13 | 10 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients with relapsed or refractory | 13 | 13 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | placebo for weeks the primary | 13 | 12 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | point was investigator assessed progression | 13 | 13 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | primary end point was disease | 13 | 13 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | primary end point was survival | 13 | 13 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | psoriasis area and severity index | 13 | 13 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | randomized trial we assigned patients | 13 | 13 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | sustained virologic response at weeks | 13 | 13 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | time to event analysis was | 13 | 12 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | to years of age to | 13 | 12 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | trial to evaluate the efficacy | 13 | 13 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | we performed a randomized double | 13 | 13 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were followed for up to | 13 | 13 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | who did not have a | 13 | 13 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | years of age or younger | 13 | 13 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | a dose of either mg | 12 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | aspirin at a dose of | 12 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | at a daily dose of | 12 | 11 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | at a dose of iu | 12 | 10 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | between and years of age | 12 | 12 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | body mass index bmi the | 12 | 12 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | determined with the use of | 12 | 12 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | end point was the annualized | 12 | 12 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | estimated with the use of | 12 | 12 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | evaluated with the use of | 12 | 12 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | for a median of years | 12 | 12 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | in this double blind trial | 12 | 12 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | measured with the use of | 12 | 12 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | mg once daily or placebo | 12 | 12 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | of patients who had a | 12 | 12 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | on the basis of a | 12 | 12 | 100 | PP | Text |

| 2 | real time polymerase chain reaction | 12 | 12 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | secondary end point was the | 12 | 12 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | st segment elevation myocardial infarction | 12 | 12 | 0 | NP | Res |

| 2 | than years of age who | 12 | 12 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the percentage of patients who | 12 | 11 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | the primary composite outcome was | 12 | 12 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary objective was to | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome was day | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcome was survival | 12 | 12 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the primary outcomes were the | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the secondary end points were | 12 | 12 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | to years of age in | 12 | 11 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | trial in which patients with | 12 | 12 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | was the time to the | 12 | 11 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we evaluated the effect of | 12 | 12 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we evaluated the efficacy of | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we performed a multicenter randomized | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were at high risk for | 12 | 12 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | were randomly assigned to the | 12 | 12 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | with a by factorial design | 12 | 12 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | a by factorial design we | 11 | 11 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | a noninferiority margin of percentage | 11 | 11 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | an estimated glomerular filtration rate | 11 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | an intention to treat basis | 11 | 11 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | assessed in a time to | 11 | 8 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | assigned to one of three | 11 | 11 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | controlled trial involving patients with | 11 | 11 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | death from coronary heart disease | 11 | 10 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | disease patients were randomly assigned | 11 | 11 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | dose of mg every weeks | 11 | 11 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | dose of to mg per | 11 | 10 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | factorial design we randomly assigned | 11 | 11 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | from no symptoms to death | 11 | 11 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | in the intensive care unit | 11 | 11 | 80 | PP | Res |

| 2 | in this double blind randomized | 11 | 11 | 40 | PP | Res |

| 2 | of less than mm hg | 11 | 7 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | of the confidence interval for | 11 | 11 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | open label randomized controlled trial | 11 | 11 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients at high risk for | 11 | 11 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients were stratified according to | 11 | 11 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | patients who had had a | 11 | 11 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | patients with type diabetes who | 11 | 11 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | peginterferon alfa a and ribavirin | 11 | 7 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | per square meter on day | 11 | 8 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | randomly assigned them to receive | 11 | 11 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | safety outcome was major bleeding | 11 | 11 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | single nucleotide polymorphisms snps in | 11 | 11 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | the principal safety outcome was | 11 | 11 | 40 | VP | Res |

| 2 | the rate of death from | 11 | 10 | 100 | NP | Res |

| 2 | to evaluate the efficacy and | 11 | 11 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | to one of three groups | 11 | 11 | 100 | PP | Res |

| 2 | was a secondary end point | 11 | 11 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | was death from cardiovascular causes | 11 | 11 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | we randomly assigned patients years | 11 | 11 | 60 | VP | Res |

| 2 | who had a response to | 11 | 11 | 100 | VP | Res |

| 2 | who received a diagnosis of | 11 | 10 | 80 | VP | Res |

| 2 | within hours after symptom onset | 11 | 11 | 60 | PP | Res |

| 2 | a glycated hemoglobin level of | 10 | 8 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | a multicenter double blind randomized | 10 | 10 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | a multicenter randomized open label | 10 | 10 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | and the primary end point | 10 | 10 | 80 | NP | Res |

| 2 | area under the curve auc | 10 | 10 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | bone mineral density at the | 10 | 8 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | cardiovascular death myocardial infarction or | 10 | 10 | 40 | NP | Res |

| 2 | cisplatin mg per square meter | 10 | 10 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | clinical trial we randomly assigned | 10 | 10 | 20 | NP | Res |

| 2 | controlled study we randomly assigned | 10 | 10 | 60 | NP | Res |

| 2 | coprimary end points were the | 10 | 10 | 80 | VP | Res |