Abstract

This article contributes the first corpus-based study of possession in Māori, the indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand. Like most Polynesian languages, Māori has a dual possessive system involving a choice between the so-called A and O categories. While Māori grammars describe these categories in terms of the inherent semantic relationship between the possessum and possessor, there have been no large-scale corpus analyses demonstrating their use in natural contexts. Social media provide invaluable opportunities for such linguistic studies, capturing contemporary language use while alleviating the burden of gathering data through traditional means. We operationalise semantic distinctions to investigate possession in Māori-language tweets, focusing on the [possessum a/o possessor] construction (e.g., te tīmatanga o te wiki ‘the beginning of the week’). In our corpus comprising 2500 tweets produced by more than 200 individuals, we find that users leverage a wide array of noun types encompassing many different semantic relationships. We observe not only the expected predominance of the O category, but also a tendency for examples described by Māori grammars as A-marked to instead be O-marked (59%). Although the A category persists in the corpus, our findings suggest that language change could be underway. Our primary dataset can be explored interactively online.

1. Introduction

Like most of its Polynesian cousins, Māori, the indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand, has a complex possessive system involving a choice between the so-called A and O categories. This system encompasses a range of different forms (Harlow 2000; Bauer et al. 1997, pp. 390–407), with A/O alternation having been described as one of the “thorniest” aspects of Māori grammar (Harlow 2007, p. 170). Indeed, the A/O distinction presents a significant challenge for linguists, teachers, and learners alike (Fusi 1985; Bauer et al. 1997; Thornton 1998; Harlow 2000).

This paper presents the first empirical analysis of this phenomenon in Māori by drawing on an existing corpus of Māori-language tweets (Trye et al. 2022), which we believe is representative of the language used by contemporary speakers of Māori. The paper has two main aims. Firstly, we intend to show how possessive markers are used by contemporary Māori speakers, documenting the extent to which this usage conforms with traditional descriptions of A/O alternation in Māori grammars. Secondly, because many corpus linguistic studies involve categorical variables (Levshina 2015; Stefanowitsch 2020), we hope to demonstrate the general applicability of two novel visualisation techniques called MultiCat (Trye et al. 2024) and the Heatmap Matrix Explorer (Trye et al. 2023). Before outlining the details of this study, a general introduction to the topic of possessives is in order, together with some background information about the Māori language.

So important is the notion of possession that all languages have some way of expressing it (Aikhenvald 2013, p. 1). Unsurprisingly, a wealth of accounts of linguistic possession has emerged, documenting the various systems found in the languages of the world. However, since it is neither possible nor desirable to summarise this body of work in only a few paragraphs, we limit our discussion to the most relevant points. The first observation is that, depending on the language, possessives can be expressed by a diverse array of constructions, including verbs, pronouns, case markers, and adpositions.

At its core, linguistic possession concerns relationships between entities. Here, we focus specifically on noun phrases encoding possession, also known as adnominal possessives (Haspelmath 2017, p. 196). Possession involves a semantic relationship between a possessor, an entity that owns or possesses something, and a possessum1 (pl. possessa), the entity owned or possessed. However, the notion of possession is fuzzy, occurring in figurative expressions that do not encompass a strict relationship of ownership, such as part–whole relationships (fingers of the hand, pages of a book), human relationships (my friend’s brother, John’s wife), features (the cruelty of the war, the purpose of those canoes), and cognitive processes (my mother’s thoughts, the boy’s anger), among others.

In considering possessive constructions, it is useful to separate the semantic relationship between the possessum and possessor on the one hand, and the grammatical form used by languages to express this relationship (which we loosely term ‘possession’) on the other. A frequent distinction is made between alienable and inalienable possession.2 At the heart of this distinction lies the observation that certain possessive relationships involve situations in which the possessum and possessor are inextricably linked. For example, the notion of a biological brother implies the existence of at least one sibling, and body parts like hand and mouth are associated with the person to whom they belong. Haspelmath (2017, p. 197; 2021, p. 618) defines inalienable possessives as those involving body parts or kinship relationships. Some scholars have claimed there is a distinction between alienable and inalienable possession in Māori (e.g., Krupa 1964, p. 434), with alienable possessa being marked by the A category and inalienable possessa by the O category; however, this has been superseded by more recent proposals based on the notions of dominance and control (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 390; Harlow 2000, p. 363; 2015, p. 141).

An important dimension when analysing possessive marking systems, and one that is deemed highly relevant for Māori (see Section 2), involves finer distinctions between the various semantic classes of the entities involved. Semantic classes contain lexically specified sets of nouns with particular characteristics, which, in the case of Māori, and, indeed, most other Polynesian languages (Wilson 1982, p. 3), attract different possessive markers. While grouping nouns into semantic classes entails knowledge of various language-internal idiosyncrasies, the vast amount of typological work on possession points to some common semantic classes relevant to possessive marking that recur across languages. For example, Chousou-Polydouri et al. (2023, p. 1382) identify the following classes: animals (sometimes split into wild or domesticated), body, kin (sometimes split into nuclear family, blood relations, or relations of marriage), inanimate natural entities, strict owner relations (owner, master), part–whole relationships, plants, place-related terms (native land, country), intimate property (furniture, tools, ornaments), names of people and places, mass nouns, and a mixed class with no semantic patterning. These categories provide a useful frame of reference for our analysis of Māori possessives (see Section 4.1).

Having introduced the phenomenon investigated in this article, we now provide some context about the language analysed. Our study focuses on possessive constructions in Māori, a Polynesian language spoken in the Pacific, in Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori is spoken by approximately 4% of the total population (Statistics NZ 2018), including roughly one in six Māori adults (Te Kupenga 2018). Most speakers acquire Māori either as compound or coordinate bilinguals, or as adult L2 speakers (King 2018). Unsurprisingly, L1 and L2 speakers’ language use differs considerably (Kelly 2014; Christensen 2003; Lane 2024). Moreover, far from being a single, uniform language, Māori encompasses several distinct dialects (Harlow 2007), including some variations concerning the use of the A/O categories (Biggs 1955, p. 341). As is often the case with indigenous languages, the story of te reo Māori (the Māori language) is characterised by the Māori people’s enduring fight for the survival and revitalisation of their language in the face of intense and ongoing colonisation (Greensill et al. 2017; Higgins et al. 2014; Whaanga and Greensill 2014, and references therein). One consequence of this language acquisition context is that English, as the dominant lingua franca in Aotearoa New Zealand, has had a significant impact on the contemporary usage of Māori (Tawhara 2015; Harlow 2007; Harlow et al. 2011). Today, Māori is considered to be both endangered and low-resourced, though several corpora and digital tools have been developed to aid its revitalisation (for an overview, see Trye et al. 2022, pp. 1234–36).

Scope

Due to limitations of time and space, our analysis focuses on a constrained but salient part of the possessive system, namely A/O alternation, as found in constructions of the type [possessum a/o possessor].3 In this construction, the possessum and possessor are both noun phrases, while the possessive marker functions as a preposition meaning ‘of’. The a/o marker is used to “introduce possessive comments following nouns preceded by any determiner except he” (Harlow 2015, p. 140).

Our rationale for focusing exclusively on the [possessum a/o possessor] construction is that it involves a clear dichotomy between the A/O categories, since there is no available neutral form (see Harlow 2000, p. 365) and we thought it would be relatively straightforward to identify (compared to, say, the pairs nā/nō and mā/mō, which have numerous functions; see Harlow 2015, pp. 72–73).

It is important to emphasise that the [possessum a/o possessor] construction relates to just one of five sets of Māori possessive particles, all of which involve A/O alternation (Harlow 2000, p. 362). Nevertheless, we hope our target construction will serve as a microcosm for the wider possessive system, providing general insights into how Māori-language tweeters use the A and O categories. To the best of our knowledge, this research constitutes the first corpus-based study of possession in Māori, and the first study of any aspect of Māori grammar on social media. Besides the work of Kelly (2015) and Nicholas (2010), we are not aware of any in-depth quantitative research on naturally occurring Māori grammar. Our work aims to help bridge this gap by analysing a sizable Twitter4 corpus of real-world data.

2. A/O Alternation in Māori

Like most Polynesian languages, possession in Māori entails a choice between the A and O categories (Harlow 2000, p. 357). This distinction is the bugbear of many Māori-language learners, with some taking to social media to humorously share their frustrations (“Figuring out A and O is like doing long division in my head”) and console themselves (“at least there’s a 50/50 chance of getting it right”; comments on an Instagram post, 14 March 2024). Bauer et al. (1993, p. 209) note that “the ‘correct’ use of the A/O distinction is regarded as a shibboleth by many Māori speakers”, which still frequently generates discussion as to why one form is preferable over the other.

According to Māori grammars, A/O alternation is contingent on the relationship between the possessor and possessum (Harlow 2015, p. 141; Bauer et al. 1997, p. 390). As a rule of thumb, the A class is best viewed as a ‘special’ (marked) relationship between the two (Clark 1976, pp. 42–44), used in situations where the possessor is dominant (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 390) or the possessum comes under its protection or authority (Head 1989, p. 102). This latter framing places responsibility on the possessor to be a good kaitiaki ‘guardian’. The O class, on the other hand, is the ‘default’ (unmarked) category that applies in all other cases (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 391; Harlow 2007, p. 168).

A wealth of proposals concerning the A/O categories has emerged over the past few decades, reflecting the complexity of this topic. As Fusi (1985, p. 119) puts it, “grammars try in different ways to give a satisfactory explanation … and in the end all of them seem more or less (and each one in its own way) to have achieved an approximate comprehension of the mechanism involved, but without managing to give an exhaustive explanation of it”. This variability applies to both the generalisations used, as well as explanations of individual exceptions. For example, the following labels have been posited by various scholars to succinctly capture the contrast between the A and O classes, respectively:

- alienability vs. inalienability (Krupa 1964, p. 434; 2003, p. 122)

- active vs. passive (Foster 1987)

- dominance vs. subordination (Biggs 1996, p. 42), later revised to dominance vs. non-dominance (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 391; Biggs 2000, as cited in Harlow 2007, p. 168)

- inheritance vs. active production (Ryan 1974, p. 5)

- control vs. non-control (Moorfield 1988, p. 140; Ryan 1980, p. 75; Capell 1949)

- higher vs. lower tapu ‘potentiality for power’ and mana ‘prestige’ (Thornton 1998)

While, on the surface, these labels appear to be quite different, they all boil down to the notion of agency on the part of the possessor (even Krupa perceives the A category as dominant in his explanation of alienability vs. inalienability). Thornton (1998, p. 390) acknowledges that her categorisation with respect to tapu and mana is not robust for certain constructions, like subjects of nominalisations, which are “best described in grammatical terms” (see 3 below).

As mentioned above, our focus in this paper is on constructions of the form [possessum a/o possessor]. We provide three examples by way of introduction.5 Examples (1–2) illustrate a distinction in the possessive system with respect to kinship ties, and constitute typical examples that a learner of Māori might be exposed to in beginner classes. In (1), an a marker is used because children are generationally below their parents; conversely, an o marker is used in (2) because parents are generationally above their children. Example (3) features the subject (Rāwiri ‘David’) of the nominalisation of an active transitive verb (tuhinga ‘writing’), for which an a marker is used.

| (1) | ngā | tamariki | a | te | matua |

| the.PL | children | POSS | the.SG | parent | |

| ‘The children of the parent/the parent’s children’ | |||||

| (2) | te | matua | o | ngā | tamariki |

| the.SG | parent | POSS | the.PL | children | |

| ‘The parent of the children/the children’s parent’ | |||||

| (3) | te | tuhinga | a | Rāwiri | i | tana | reta |

| the.SG | writing | POSS | David | OBJ | his | letter | |

| ‘David’s writing of his letter’ | |||||||

Grammars and other pedagogical texts (e.g., Harlow 2007, pp. 166–67; Harlow 2015, pp. 140–46; Head 1989, pp. 101–16) typically explain A/O alternation by grouping items into semantic classes, such as those detailed in Table 1. While full treatment is normally given to both the A and O classes, since O is unmarked, theoretically, “one need only specify when the a-forms should be used” (Harlow 2007, p. 168).

Table 1.

Summary of categories given in Harlow (2007, pp. 166–67).

Despite this last observation, a popular model used for teaching purposes is Ngā Kawekawe o te Wheke ‘The Tentacles of the Octopus’,6 which inverts this approach by giving primacy to the O class. Developed by Pānia Papa and Leon Heketū Blake, this model specifies eight semantic categories, one for each tentacle, which take O forms rather than A forms. Generally, anything that falls outside of these categories is likely to be A-possessed. To enhance memorability, the categories are all ‘W’ or ‘Wh’ words, which are salient sounds in Māori:

- Whakarākei/Adornments

- Whanaunga/Relations (of same generation or older)

- Waka/Modes of transport

- Wāhanga/Parts of someone/thing

- Whakaruruhau/Shelter7

- Whakaora/Wellbeing

- Wāhi/Places

- Whakaahua/Adjectives or qualities of someone/thing

While these kinds of lists (e.g., Table 1) and more general (e.g., control-based) explanations are helpful because they are practical for learners, as far as linguistic theory is concerned, they “miss what is going on at a more abstract level” (Harlow 2007, p. 167). Unfortunately, exhaustive guidelines are not possible: there will always be cases involving noun phrases that are not explicitly covered by the specified rules (Kārena-Holmes 2021). Some dictionaries list words as being either A-possessed or O-possessed (e.g., Williams and Williams 1971); however, such classifications are not definitive, since many noun phrases can occur in different contexts with a contrast in meaning (Fusi 1985, p. 119). For example, a book or song written by someone takes A, while a book or song about someone takes O (Biggs 1996, p. 42); clothes designed by someone take A, while clothes owned or worn by someone take O (Harlow 2015, p. 141); a photo taken or owned by someone is A-possessed, while a photo of someone takes O (Harlow 2000, p. 363). Unsurprisingly, learners often struggle with these fine-grained semantic distinctions, because they conceptualise the item in question as belonging to a specific category and, hence, having a fixed marker.

Adding to the confusion, lists of items for remembering the A/O categories inevitably contain exceptions or anomalies (Harlow 2015, p. 141). Table 1 accounts for certain lexical exceptions (such as uri, wai, and rongoā) and exclusions (e.g., animals not used for transport), but these are by no means exhaustive. For instance, contrary to Table 1, some intransitive verbs favour A (e.g., noho ‘sit, stay’) or can be used with both A and O forms, depending on what is being emphasised (Harlow 2015, p. 188).

Control-based explanations of the A/O distinction also run into trouble with seemingly asymmetrical cases, such as the use of A for both one’s husband (e.g., te tāne a Mere ‘the husband of Mere’) and one’s wife (e.g., te wahine a Tama ‘the wife of Tama’). While different explanations can be found (Harlow 2007, p. 169), the point is that applying the notion of control (or similar) cannot straightforwardly account for all patterns observed. A further objection raised with such interpretations is that they are often presented from a Western perspective that does not always match the Māori worldview (Thornton 1998; Fusi 1985).

Another issue is speaker variation (Harlow 2007, p. 168). Even proficient first-language speakers sometimes disagree about which marker should be used in a given context, and the same or different speakers may use contrasting markers without any perceptible difference in meaning (Harlow 2015, p. 141; Bauer et al. 1997, pp. 393–94). Biggs (1955, p. 341) notes that A forms are more prevalent in the case of first-person possessors. Anecdotally, some speakers use A for drinking water, while others use O when referring to water used for both drinking and washing (Harlow 2015, p. 143). Similar examples have been noted elsewhere in the literature (e.g., Fusi 1985, p. 122).

A related problem is the ambiguity of classifications. Should a horse that is retired still be O-marked, as Table 1 might suggest, or should it be A-marked like other pets? Does it make a difference whether the horse in question carries (or carried) people or things? There is no unanimous agreement here: both forms have been attested by native Māori speakers (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 393). Similarly, should a hamarara ‘umbrella’ be considered a small portable object (A) or a personal adornment (O), and does this change depending on whether it is in use? According to Te Wheke (the Octopus model), an umbrella that is being used provides a form of shelter (Whakaruruhau), which takes O, while an umbrella not in use is merely a rākau ‘stick’, which does not fit into any of the eight categories and, therefore, takes A. In these sorts of cases, a second-language speaker’s use of A or O will again vary according to their understanding of the categories they are taught.

Furthermore, incoming words and changes in the environment affect the marking patterns used, sometimes also resulting in discrepancies between speakers. Bauer et al. (1997, p. 391) attribute many of the challenges with A/O classification to items introduced after European settlement, which disrupted the existing categories by partially fulfilling properties of each, and, therefore, not clearly fitting into either. For example, waka, being O-marked, was once the only form of transport, and generally belonged to the tribe rather than the individual. Bauer et al. (ibid) speculate that, when horses and cars came along, it was not clear whether they should be considered as items in an individual’s control (and, hence, A-marked) or items that shared the same function as canoes (and, hence, O-marked), though most items of this nature were ultimately subsumed by the unmarked O category. As Krupa (2003, p. 133) notes, “The values valid within a community may undergo modification in time and, besides, conflicts in the classification as well as ambiguity no doubt stimulate changes and further evolution”.

It is no wonder, then, that A/O alternation constitutes “one of the most complex aspects of Māori grammar” (Harlow 2015, p. 140) and appears to have generated “more pages of text … than any other single grammatical topic in Māori” (Bauer et al. 1997, p. 390).

We conclude this section with the personal perspective of one of the authors of the paper, who is an L2 Māori speaker, reflecting on his own experience acquiring possessive markers:

“As a second-language speaker of te reo Māori, I was introduced to the A and O categories early as another example of how reo (language) and tikanga (customs) are intertwined. To have confidence knowing which is the correct marker to use, one has to have a good understanding of the relationships being discussed and where the mana (authority) of the relationship resides. In general, the more authoritative actor has the O category, with the more submissive character being referred to in the A category. But there are lots of nuances, with objects taking the O category in some instances, but then the same object taking the A category in other instances, depending on the different relationships that are in play. I was fortunate that when I learnt te reo Māori I was in the presence of some gifted exponents of Māori language. Once my ear became tuned, I found that I was able to defer to what sounded the best, rather than turning to specific rules about which category should be used. For me, this makes learning and speaking te reo Māori natural and more enjoyable as I am not relying on following rules, but rather I am being guided by a taonga (treasure) that has been handed down to me. Unfortunately, this does not mean I am correct all the time, but it works well enough for me to run with it!”

Research Questions

Given the complexity surrounding this topic, our work aims to investigate how contemporary Māori speakers handle A/O alternation on social media. Thus, our research questions are as follows:

- RQ1: What semantic categories and relationships are most frequently used by Māori-language tweeters in the [possessum a/o possessor] construction?

- RQ2: To what extent do Māori-language tweeters adhere to the rules described in Māori grammars when using the [possessum a/o possessor] construction? By analysing semantic categories and relationships, can patterns of adherence to and/or deviation from these rules be identified?

- RQ3: What are the sociolinguistic profiles of the tweeters in the corpus? If notable patterns arise from RQ2, can these be linked to characteristics such as gender, number of followers, and overall proportion of Māori-language tweets?

While these questions refer specifically to Māori-language tweeters, we believe the data are likely to be representative of everyday speakers of Māori in the current bilingual context, perhaps with a skew towards younger L2 speakers. Therefore, we aim to contribute not only to the understanding of Māori language use on social media, but also contemporary speakers’ use of Māori more generally.

We propose the following hypotheses about each of our research questions. Based on the research cited in Section 1 (e.g., Haspelmath 2017), we hypothesise that constructions involving kinship terms and body parts will be the most frequent in our data (RQ1). Secondly, with respect to RQ2, we anticipate that Māori-language tweeters, and by extension, contemporary speakers of Māori, will display a strong preference towards the O category, even in circumstances where this contravenes the usage described in Māori grammars. In terms of RQ3, we predict that women will deviate from this described usage more often than men, because they are known to be drivers of language change.

3. Data and Methods

The data for this study were sourced from the second release of the Reo Māori Twitter (RMT) Corpus (Trye et al. 2022). This dataset comprises 94,163 tweets posted by 2302 users over a 14-year period (2007–2022). For practical reasons, we focus on only a small subset of these tweets and users within our study (2484 tweets written by 237 users). All users in the RMT Corpus were originally identified through the Indigenous Tweets website (Scannell 2022), and their tweets were obtained using the official Twitter API. To protect the users’ privacy, any links and usernames within each tweet were replaced with the placeholders <link> and <user>, respectively. Since the corpus predates Twitter’s rebranding to X in July 2023, we refer to individual posts as ‘tweets’ throughout the paper.

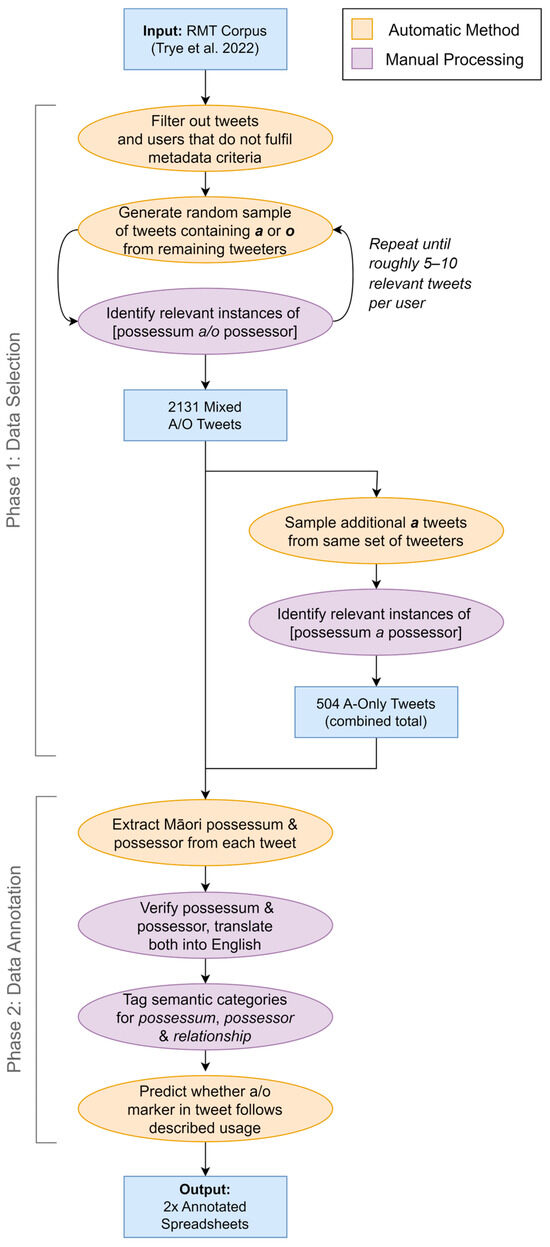

Figure 1 summarises the process that we followed to prepare the data for analysis. Broadly, our approach consisted of two phases: an iterative selection process, aimed at curating a set of tweets that was relatively balanced across users, followed by an annotation procedure for determining whether the possessive marker used conformed with descriptions in Māori grammars. The steps within each phase comprised a mixture of computational and manual methods. Ultimately, we created two datasets for our study: a Mixed Dataset, which aimed to capture the ‘real’ distribution of A/O usage for our target construction, and an A-Only Dataset, whose purpose was to address the under-representation of a markers within the Mixed Dataset.

Figure 1.

A visual overview of our data curation process. Some steps were performed computationally (orange), while others required manual processing (purple).

The first step in preparing the data was to systematically remove a large number of tweets that did not fulfil our requirements. Given the practical constraints associated with the manual identification and annotation of tweets, we decided to focus on a small but meaningful subset of the RMT Corpus. Tweets were initially filtered out according to three criteria. First, we excluded tweets whose timestamp was unknown, as these would not be suitable for diachronic analysis. Furthermore, this helped to reduce the proportion of incomplete metadata, since many tweets that were missing timestamps were also missing other values. Secondly, because we wanted each account to represent a discrete user, we removed tweets belonging to institutional and group accounts. Thirdly, we discarded tweets from users whose gender was unknown, as we wanted this to be the principal variable in our sociolinguistic analysis.8 Overall, this step reduced the number of tweets in our sampling pool to 70,783 (a 25% decrease) and the number of users to 1582 (a 31% decrease).

From the remaining data, we generated a random sample comprising exactly ten tweets per user. We filtered out users whose combined number of tweets containing a and o (without macrons) fell short of this number. At this point, we also automatically removed specific instances of the personal article (Harlow 2015, p. 67) and Cook Islands Māori, which is a separate language, by leveraging patterns in the data. If the same tweet contained multiple instances of a and/or o, we considered only the first instance. We limited the data to ten tweets per user because we did not want to over-represent prolific tweeters, opting instead for a more balanced and diverse user sample. This step reduced our user base by a further 85%, leaving only 241 users and yielding an initial sample of 2410 tweets.

The next step involved manually scanning the tweets to determine whether they constituted relevant instances of the [possessum a/o possessor] construction. In particular, we removed the following irrelevant tweets:

- Non-possessive uses of a and o, including occurrences of the English indefinite article, incorrect word division (e.g., a’s that had become detached from kia), and remaining instances of the personal article;

- Tweets in which (short) a or o were used instead of (long) ā or ō, respectively;

- Formulaic phrases9 in which users did not explicitly choose a possessive marker (e.g., Te Wiki o te Reo Māori ‘Māori Language Week’);

- Tweets where the use of a or o was unclear.

Manual inspection of the 2410 tweets in our first sample revealed that roughly a third of the data (780 tweets) were irrelevant. This included the overwhelming majority of tweets containing a (80%), as well as 20% of tweets containing o. After removing these tweets, most users in our dataset had fewer than ten tweets, and many had fewer than five. An iterative sampling strategy was employed to mitigate this imbalance across users.

Since many users had additional tweets containing a and o that were not part of our first sample, we randomly selected (from the leftover supply) the number of tweets needed to bring each user’s total up to ten, or as close to ten as possible. The relevant tweets from the new sample were then added to those from the previous sample. This process was repeated three times, with each successive sample becoming smaller as we procured more relevant tweets from the necessary users and/or exhausted their leftover supply. To expedite the tagging process, we automatically removed any tweets containing recurrent formulaic phrases that were present in our first sample (e.g., Te Tiriti o Waitangi ‘the Treaty of Waitangi’ and Te Wiki o te Reo Māori ‘Māori Language Week’).

Unfortunately, even after completing our iterative sampling procedure, many users still had fewer than ten relevant instances of our target construction. Consequently, we settled on a final range of between four and ten tweets per user. We removed four users whose final tweet count fell below this threshold.

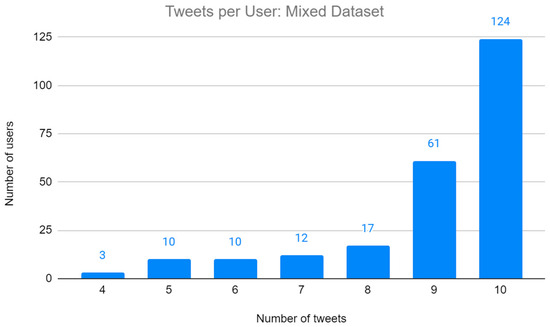

All of this resulted in our final Mixed Dataset, which comprised 151 a-marked tweets and 1980 o-marked tweets. The distribution of tweets per user is shown in Figure 2. Just over half of the 237 users (52%) had a complete set of ten tweets and over three-quarters (78%) had at least nine tweets. Overall, we manually checked 3297 tweets when creating the Mixed Dataset and retained 65% of these. The proportion of discarded tweets for each marker closely matched our first sample (80% for a and 22% for o), which is not surprising, given that the first sample was by far the largest.

Figure 2.

The number of tweets per user in the Mixed Dataset.

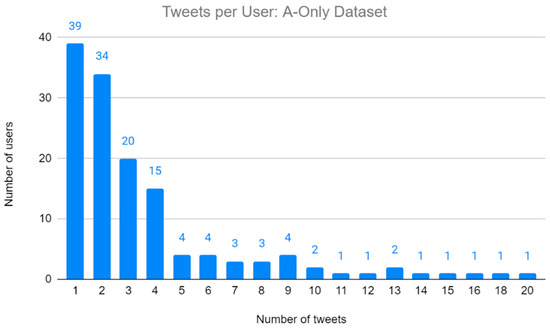

Due to the under-representation of the A category in the Mixed Dataset, we decided to gather additional instances of the a form so that we could more thoroughly examine its use on social media. To this end, we generated a further random sample of 1640 tweets from users in the Mixed Dataset who had leftover tweets containing a. We manually checked this sample and removed irrelevant instances in the same manner as that for the Mixed Dataset. However, when sampling the data, we extended the acceptable range of tweets per user to between 1 and 20, recognising that, because a is relatively infrequent as a possessive marker, we would need to draw more heavily from prolific tweeters in the corpus. Only 353 of the tweets in the sample (22%) were relevant. We combined these with all instances of a from the Mixed Dataset, resulting in 504 a-marked tweets in total. We refer to this as the A-Only Dataset. We chose not to merge our two datasets completely, because we did not want to interfere with the natural distribution of a/o markers in the Mixed Dataset.

The numbers of tweets per user in the A-Only Dataset are shown in Figure 3. The dataset was skewed in the opposite direction to the Mixed Dataset: due to the lack of data, there were more users with fewer tweets. Indeed, most users had fewer than five relevant a tweets. The dataset contains tweets from 58% of users (137 of 237) in the Mixed Dataset, which shows that most users did not disregard a altogether, even if they used it much less frequently than o. However, there is still a large proportion of users (42%) in the Mixed Dataset that did not use a at all.

Figure 3.

The number of tweets per user in the A-Only Dataset.

Having gathered the data for our analysis, we were now in a position to annotate them. We attempted to computationally extract both the possessum and possessor based on their positions. Following this, an L1 Māori-language speaker manually updated any items that had not been correctly identified. The same speaker then translated the possessum and possessor from Māori into English, using the definition they deemed most appropriate within the context of each phrase and consulting the online Māori dictionary (https://maoridictionary.co.nz/, acccessed on 20 November 2023) where necessary. Given that many words are polysemous in Māori (Boyce 2006), this was not a straightforward task. We deleted a handful of tweets where the possessum or possessor were neither familiar to the speaker nor listed in the Māori dictionary (e.g., te rauiwi, te tikene).

One of the authors then tagged each possessive phrase according to three semantic variables (PSSM, PSSR, and RELA), as detailed in Section 4. Briefly, the PSSM and PSSR variables incorporate the same set of 22 semantic categories to classify the possessum and possessor, respectively, while the RELA variable comprises a distinct set of 13 categories for encoding the relationship between the two. The author responsible for assigning the semantic categories flagged any tweets they were unsure about, which were then checked by another author with greater proficiency in Māori. We discarded a small proportion of tweets which, despite initially having been marked as ‘relevant’, were re-evaluated as formulaic or ambiguous.

Since most of the semantic coding was performed by the same person, we sampled 10% of the data for another analyst to code independently. The inter-rater reliability scores for this sample are given in Table 2, showing strong overall agreement for all three semantic variables.

Table 2.

Inter-rater reliability for all three manually coded semantic variables.

Finally, we created a variable called Type, which draws on information from Māori grammars to predict whether each possessive phrase in our data used the described and, therefore, expected marker. Further details are given in Section 4.4.

4. Semantic Classification Scheme

Since our semantic classification scheme is crucial to our analysis, we provide further context about the development of these categories and the main challenges encountered. As mentioned in Section 3, we coded separate variables for the possessum (PSSM), possessor (PSSR), and the relationship (RELA) between the two. The literature on Māori suggests that our RELA variable is the principal factor determining the choice of possessive marker (Harlow 2000, p. 363; Bauer et al. 1997, p. 290; Harlow 2015, p. 141). However, we still wanted to code the other two variables, as we were interested in exploring the most common kinds of nouns used in possessive phrases and uncovering the associations between the three variables (for example, do certain relationships predominantly occur with specific types of possessum or possessor?). We devised our own classification scheme for these variables, drawing on existing Māori grammars and guides, especially Head (1989), Biggs (1996), and Harlow (2015). Our process for fine-tuning the labels was highly collaborative and resulted from several coding sessions where we discussed actual examples from our data.

4.1. PSSM and PSSR Variables

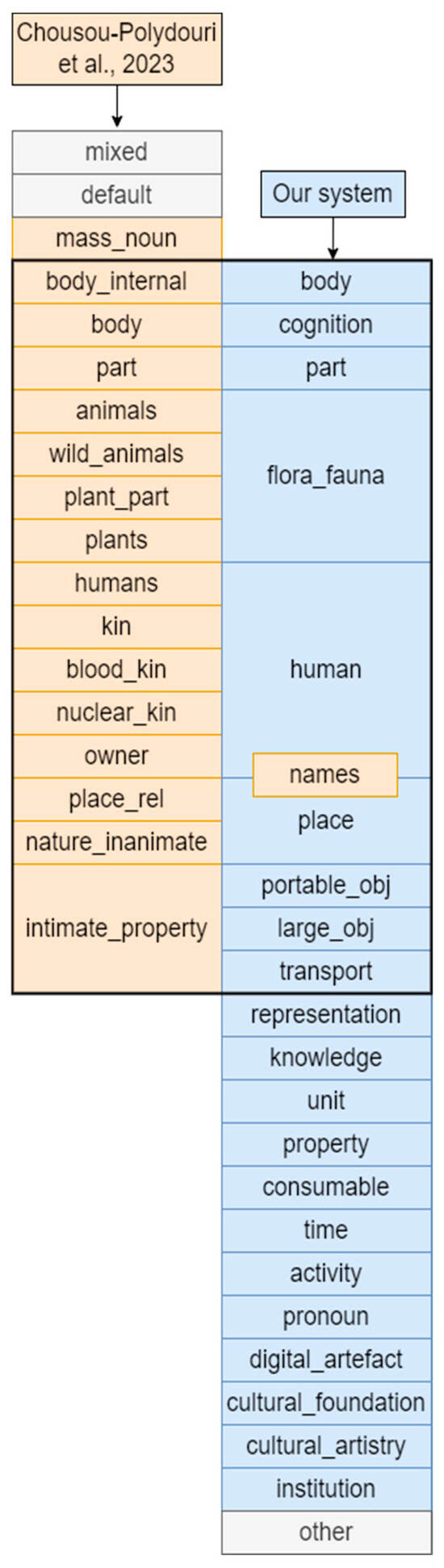

The 22 categories that we devised for the PSSM and PSSR variables are shown on the right side of Figure 4, while full definitions and examples are given in Table S1. One of the difficulties we faced was deciding on an appropriate number of categories. Our goal was to strike a sensible balance by capturing the intricacies of A/O alternation in Māori, without making the categories so specific that they applied to only a handful of noun phrases. To give just one example, we felt that there is an important distinction between intrinsic components of cultural identity, such as language and religion, and deliberate forms of creative expression by groups or individuals, such as music, poetry, and dance. This led us to create two separate categories for cultural artefacts, namely cultural_foundation and cultural_artistry.

Figure 4.

Overview of semantic categories used in existing research and in the present study. Grey boxes denote classes that are not semantically coherent.

As alluded to in Section 1, our semantic categories share obvious similarities with those developed by Chousou-Polydouri et al. (2023, p. 1382) for the purpose of cross-linguistic comparison. Figure 4 provides a visual overview of the similarities and differences between their framework (shown in orange) and our own (shown in blue), which was created independently. Categories that are vertically aligned within the black rectangle exhibit substantial overlap, though they are not necessarily identical. For example, the orange body category, distinct from body_internal, covers mental faculties and feelings, and, therefore, aligns closely with our cognition category. As one might expect, our language-specific system comprises several categories that do not correspond with Chousou-Polydouri et al.’s more general approach, while the reverse is not true. In most cases, these extra categories were incorporated because they were mentioned in Māori grammars and/or occurred multiple times in our data.

4.2. RELA Variable

As noted above, the literature on Māori emphasises that the relationship between the possessum and possessor is of paramount importance. For this reason, we coded a separate variable, called RELA, with 13 kinds of relationships. Detailed definitions and examples are given in Table S2, but we provide a summary here. We created four categories for interpersonal relationships (i.e., possessive phrases where both the possessum and possessor are human): <kin, <non-kin, >=kin, and >=non-kin. As the names suggest, the appropriate category depended on whether the possessum and possessor had a familial connection and on whether the former was senior to, or responsible for, the latter. We distinguished between an ownership category for personal belongings/assets, and a creation category for entities made or produced by the possessor. A creation/ownership category was reserved for cases where there was not enough context to determine which of these relationships applied. We used a partitive category for part–whole relationships, whereby the possessum required a possessor, though possibly implied. For example, one cannot be a mema ‘member’ without being a member of something (e.g., te rōpū ‘the group’). In contrast, in a descriptor relationship, the possessum could occur independently of the possessor, but was specified, limited, or defined by it (e.g., ‘the Queen (of England)’). A feature relationship denoted cases where the possessum was a quality of the possessor, such as an abstract noun, while representation applied when the possessum symbolically, nominally, or visually represented the possessor. Finally, the nom_agentive and nom_other categories were used for nominalisations of different kinds of verbs. They can be seen as grammatical categories that override semantic rules, though the notion of agency still applies. The same verb form could occur in the nom_agentive or nom_other categories, depending, for instance, on whether active or passive voice was used (Biggs 1996, p. 42).

4.3. Semantic Annotation Challenges

As with any semantic classification system, annotating the data involved a certain degree of subjectivity. We encountered four main challenges when coding our semantic variables, which are discussed below. All examples in this section provide the original Māori text, together with the semantic classes assigned and an idiomatic English translation.10

The first challenge we faced concerned the overlapping nature of the semantic categories. Despite our efforts to delineate clear semantic boundaries, we found that certain noun phrases straddled multiple categories. In order to treat these items as consistently as possible, we added stipulations to our category definitions that were not evident from the name of the category alone (see Tables S1 and S2). For example, we consistently classified all types of buildings as place, even though they are also immovable, man-made structures (large_obj). This applied to the noun phrases whare ‘house’, kāinga ‘home’, marae ‘meeting house’, whare tapere ‘theatre’, hōhipera ‘hospital’, and whare pukapuka ‘library’, among others. Similarly, geographical features such as maunga ‘mountain’ and moana ‘sea’ were coded as place rather than as flora_fauna. Items such as kupu ‘word’, rerenga ‘sentence’, and kīanga ‘idiom’ were all coded as a unit, not representation, since they constitute linguistic units of an utterance or piece of text.

Secondly, even after adjusting our category definitions, we found that the labels for many noun phrases and relationships were highly context-dependent. We needed to consider each possessive phrase in its entirety, but in many cases, it was also necessary to examine the wider tweet. Noun phrases that occurred in multiple tweets were sometimes assigned different labels due to subtle differences in meaning. For example, pukapuka ‘book’ was categorised as cultural_artistry when referencing its literary content or author, while a physical copy of a book was labelled portable_obj. (Had it occurred in our data, an electronic copy would have been classified as a digital_artefact.) We wanted our system to reflect these nuances in meaning, in case they proved relevant for determining the appropriate possessive marker.

Moreover, as explained in Section 2, Māori grammars emphasise that the same noun phrase, and even the same possessum–possessor pair, does not guarantee the same kind of relationship (i.e., RELA category). Returning to the example of pukapuka, a book is involved in a creation relationship if the possessor is the person who wrote the book or the company that published it; example (4) references Witi Ihimaera’s book Sleeps Standing Moetū about the Battle of Ōrākau, which was translated into Māori by Hēmi Kelly. In contrast, an ownership relationship is applicable if the possessor owns a copy of the book but did not write or publish it, and a descriptor relationship applies if the possessor is the subject matter of the book. At first glance, example (5) might appear to be about a book owned or produced by a (possibly hypothetical) ‘C Company’. However, the rest of the tweet reveals important context: this particular book is written by New Zealand historian Monty Soutar, who—a quick Google search revealed—is the author of Nga Tama Toa: The Price of Citizenship: C Company 28 (Maori) Battalion 1939–1945. Therefore, (5) almost certainly references this non-fiction book about the Māori Battalion’s C Company, which served during World War II. Following Māori grammars, a creation relationship, such as that in (4), is A-marked (as would be an ownership relationship), while a descriptor relationship, such as that in (5), is O-marked. These examples illustrate how context is crucial in deciphering the precise nature of a possessive relationship.

| (4) | te | pukapuka | a | Hēmi Kelly | rāua | ko | Witi Ihimaera |

| the.SG | book | POSS | Hēmi Kelly | both | with | Witi Ihimaera | |

| <cultural_artistry> | <creation> | <human> | |||||

| ‘the book of (written by) Hēmi Kelly and Witi Ihimaera’ | |||||||

| (5) | te | pukapuka | o | Kamupene C |

| the.SG | book | POSS | C Company | |

| <cultural_artistry> | <descriptor> | <institution> | ||

| ‘the book of (about) C Company’ | ||||

A third challenge involved navigating polysemous words, which are prolific in Māori (Boyce 2006). It was important to determine the correct sense of each word in our possessive phrases in order to identify the appropriate relationship. For instance, tikanga can mean ‘custom; practice; tradition’ (as shown in examples 6–7) or ‘meaning’ (8–9). In example (6), the tweeter discusses customs created by Pākehā (European New Zealanders), with which they are unfamiliar. Example (7) refers to the tikanga ‘customs’ that operate within the kāinga ‘home’ (descriptor), although it could also be argued that kāinga in this context is a personification of the people who created the tikanga, in which case a creation relationship would again be appropriate. When tikanga is used in the sense of ‘meaning’, as in (8), this most obviously fits within our property category and the associated feature relationship: the meaning of something is a property/feature of that thing. Upon reading (9), it is not clear whether the user is asking what the initials “NZTL” stand for or if they are enquiring about NZTL’s practice. However, by viewing the tweet in context,11 we found a reply that indicated it was the former (“New Zealand Twitter League”).

| (6) | ngā | tikanga | a | Te | Pākehā |

| the.PL | customs | POSS | the.SG | European | |

| <cultural_foundation> | <creation> | <human> | |||

| ‘the customs of the European(s)’ | |||||

| (7) | ngā | tikanga | o | te | kāinga |

| the.PL | traditions | POSS | the.SG | home | |

| <cultural_foundation> | <descriptor> | <place> | |||

| ‘the traditions of the home’ | |||||

| (8) | te | tikanga | o | te | kupu |

| the.SG | meaning | POSS | the.SG | word | |

| <property> | <feature> | <unit> | |||

| ‘the meaning of the word’ | |||||

| (9) | BTW | he | aha | te | tikanga | *a | #NZTL? |

| BTW | what is | the.SG | meaning | POSS | #NZTL | ||

| <property> | <feature> | <institution> | |||||

| ‘B(y) T(he) W(ay,) what is the meaning of #NZTL?’ | |||||||

A related difficulty arose from the fact that Māori can mark nominalisations by zero morphs (Harlow 2007, p. 27). In a number of cases, there also occur nouns of the same form meaning the object produced by the particular verb. For example, kōrero can mean ‘to speak’, but also (by zero-derivation) ‘story, speech, discourse’, and waiata can mean ‘to sing’, but also ‘song’ (Harlow 2007, p. 102). Since such nominalisations are indistinguishable from noun forms, it is important to determine whether one is referring to the action itself (a nominalised verb) or the product of the action (a noun). Examples (10) and (11) capture this distinction: (10) refers to the children’s act of speaking, without telling us anything about their conversation (a nom_agentive relationship), whereas (11) comments on the accuracy of what Haimona said, involving the relationship of creation. While example (12) may seem similar to (11), it differs in that the acts of speech that the tweeter says should be celebrated are those about the country, not those created by the country.

| (10) | i oho au waenganui i | te | kōrero | a | āku | tamariki |

| TENSE wake I middle of | the.SG | conversation | POSS | my | children | |

| <activity> | <nom_agentive> | <human> | ||||

| ‘I woke up in the middle of my children’s conversation [lit. the speaking of my children]’ | ||||||

| (11) | E | tika | ana | te | kōrero | a | Haimona | nei! |

| correct | the.SG | speech | POSS | Simon | PARTICLE | |||

| <unit> | <creation> | <human> | ||||||

| ‘What Haimona said [lit. the speech of Haimona] is correct!’ | ||||||||

| (12) | me | whakanui | tatou12 | ngaa | koorero | o | eenei | motu |

| should | celebrate | we | the.PL | speech | POSS | this | country | |

| <unit> | <descriptor> | <place> | ||||||

| ‘We should celebrate the [good] things said about this country’ | ||||||||

A fourth challenge was the lack of sufficient context. Due to the nature of the data analysed, the context of certain possessive constructions was either unfamiliar to us or missing altogether. This problem was exacerbated by the general noisiness of social media data, as well as Twitter’s character constraints. Despite our best efforts, there was sometimes not enough detail in a tweet for us to ascertain its intended meaning. In such cases, we made an educated guess about the most likely interpretation of the tweet.

Fortunately, in cases where the meaning of a tweet was not clear, it was sometimes possible to find additional contextual clues. Some tweets were part of a longer thread or discussion involving multiple tweeters (e.g., example 9), and some contained useful photos or external links. However, not all tweets were still available on Twitter, so this extra context was not always available to us. As we have already seen from examples (4) and (5), in some cases, we could search online to ‘fill in the gaps’. This also proved helpful in determining whether proper nouns that were unfamiliar to us referred to a human, place, institution, or activity.

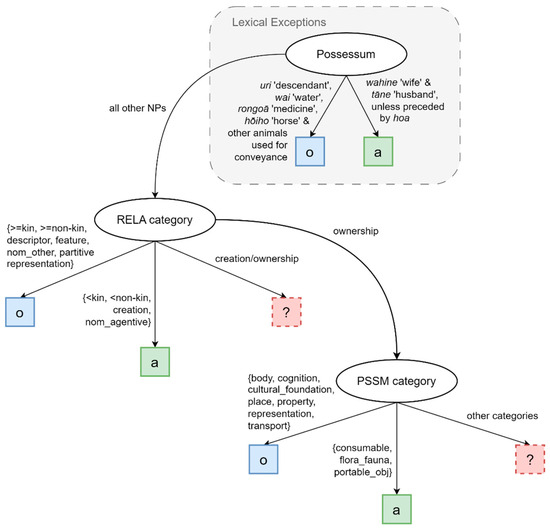

4.4. Type Variable

The final step in preparing the data was to determine whether the possessive marker used in each tweet matched the usage described in Māori grammars; this was encoded in a variable called Type. First, we created an intermediate variable called Predicted to store the expected marker (a or o) for each possessive phrase. The algorithm for computing this value is shown in Figure 5 and consists of three steps:

Figure 5.

Our algorithm for determining the Predicted marker for each possessive phrase.

- Address lexical exceptions, as identified in Harlow (2007) and Head (1989). Of these items, only uri ‘descendant’, wai ‘water’, and wahine ‘wife’ occurred in our data.

- Assign markers based on the RELA variable, but manually check the creation/ownership category and ignore ownership relationships. This is the most crucial step, as it applies to the largest proportion of data.

- For all ownership relationships, assign markers based on ten PSSM categories with fixed A/O forms, and manually check the rest.

We then compared the assigned Predicted value for each possessive phrase against the marker actually used in the tweet, giving rise to our Type variable with the following four categories:

- a_expected, if both the predicted and actual markers were a;

- a_unexpected, if the predicted marker was o but the user chose a;

- o_expected, if both the predicted and actual markers were o;

- o_unexpected, if the predicted marker was a but the user chose o.

5. Results

We will now address each of our three research questions in turn. Our findings are presented using several visualisation methods, including two novel techniques for analysing categorical data: MultiCat (Trye et al. 2024) and the Heatmap Matrix Explorer (Trye et al. 2023). Traditional static plots are useful for showing overall frequency distributions, whereas these novel interactive techniques facilitate the exploration of more complex relationships in the data. Since the figures provided in the paper are necessarily static, we provide a link13 for readers to probe the Mixed Dataset themselves, as detailed in Section 5.1. This interactive capability is, in our view, one of the main benefits of using such techniques. All figures in this section relate to the Mixed Dataset, unless otherwise stated.

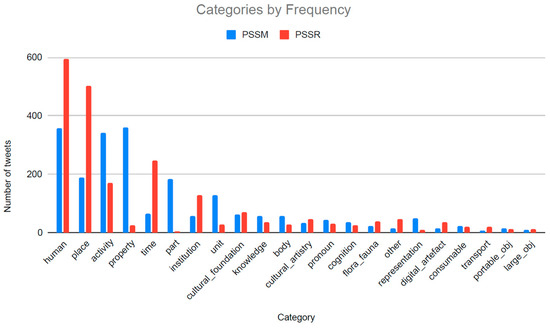

5.1. Semantic Variables by Frequency (RQ1)

We first investigate the frequency of the semantic categories and relationships in the data, examining individual categories before inspecting the patterns that arise when they are cross-tabulated. Our goal here is to shed light on the kinds of things that Māori-language tweeters typically discuss when using possessive phrases, regardless of whether they use the marker that conforms with the usage described in Māori grammars.

Figure 6 shows the frequencies of the semantic categories in the Mixed Dataset for both possessa (PSSM, shown in blue) and possessors (PSSR, shown in red). All 22 categories are represented across both positions, although there are only 4 part possessors and 8 transport possessa. There are very few instances of large_obj or portable_obj in either position, even though they are broader in scope—in terms of candidate noun phrase ‘types’—than several other categories (e.g., transport and cultural_foundation). Looking at the most frequent categories, there are many more human, place, time, and institution possessors than possessa. Conversely, the categories activity, property, part, and unit are more productive as possessa than possessors. The three most common possessum categories are property, human, and activity, which each have similar frequencies (~17%) and together account for 50% of possessa. Human, place, and time are the three most common possessor categories (28%, 24%, and 12%, respectively), constituting 64% of possessors. The presence of the human category in both of these top three rankings, and as the most frequent category overall, provides strong evidence that possessive phrases frequently relate to people.

Figure 6.

Grouped bar chart showing the frequency of each semantic category for both the possessum (blue) and possessor (red).

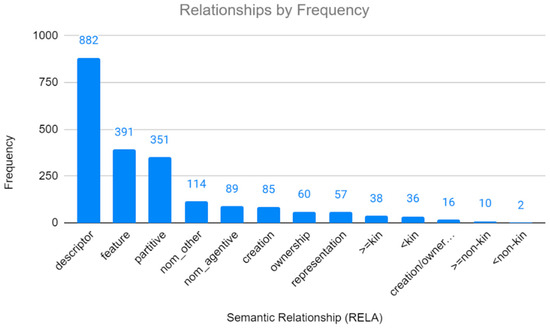

Next, we analyse the frequency of the 13 semantic relationships in our data, as shown in Figure 7. Descriptor relationships are by far the most common, occurring more than twice as often as the next most frequent categories, feature and partitive. Both types of nominalisation (nom_other and nom_agentive) are ranked next—though feature and partitive relationships are more than three times as likely—followed by creation, ownership, and representation relationships. It is interesting that nominalisations are relatively frequent, as they tend to be presented peripherally or not at all in teaching resources and lists that assign the A/O categories to individual words. Kinship relationships (>=kin and <kin) are relatively infrequent, contrary to our hypothesis for RQ1. Finally, the least frequent categories are the two non-kin relationships (>=non-kin and <non-kin), which, together, occur only a dozen times. Therefore, it would appear that, while humans are very frequent as either a possessum or possessor (Figure 6), interpersonal relationships, involving a human in both slots, are much less common.

Figure 7.

All 13 semantic relationships ordered by frequency.

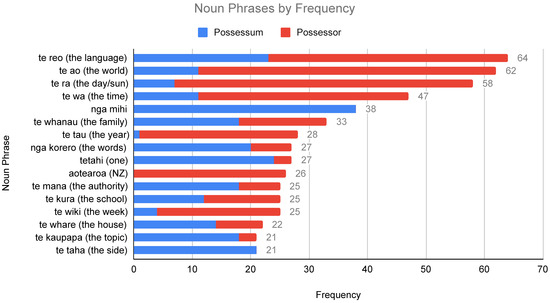

Looking at the noun phrases in our data, there are 1173 distinct possessa and 1227 distinct possessors in the Mixed Dataset. Roughly a quarter (276) of these possessa and a fifth (266) of these possessors occur more than once. Figure 8 shows the noun phrases that appear at least 20 times in the Mixed Dataset, considering their use as both a possessum (blue) and possessor (red). When processing the data, we converted noun phrases to lowercase and removed macrons to consolidate similar items, but the same phrase may still have multiple forms due to spelling errors, dialect variations, and the use of double-vowel orthography. Note that some items are polysemous and, thus, not necessarily used with the same meaning. Most items in Figure 8 comprise a mixture of blue and red, showing that common noun phrases can and do occur in both positions,14 although one particular use may be more common. For example, the four most prolific noun phrases, te reo ‘the language’, te ao ‘the world’, te rā ‘the day/sun’, and te wā ‘the time’, all occur predominantly as possessors. In contrast, the fifth most frequent noun phrase, ngā mihi ‘acknowledgements’, is used exclusively as a possessum, as is te taha ‘the side’, which appears at the bottom of the chart.

Figure 8.

Noun phrases that appear at least 20 times in the Mixed Dataset.

When considering the dataset as a whole, rather than just the most frequent noun phrases, the possessa that occur in the most distinct relationships are ngā mahi ‘the deeds/work’, te tangi ‘the funeral’, te waka ‘the canoe’, and te whare ‘the house’, which each occur in four distinct relationships. The possessors that occur in the most relationships are te whānau ‘the family’ (9 relationships), te reo ‘the language (7 relationships), te atua ‘the god’ (6 relationships), and te tangata ‘the people’ (6 relationships). These statistics suggest that possessors tend to be used in more diverse ways than possessa.

Due to the nature of our classification system, there are some clear associations between the possessum (PSSM) and relationship (RELA) variables. Notably, part and body possessa are usually involved in partitive relationships, since a part cannot exist without a whole. Unsurprisingly, representation possessa are typically part of representation relationships, and property possessa most commonly appear in feature relationships. In addition, activity possessa are frequently associated with descriptor relationships and nominalisations (either nom_agentive or nom_other). Generally, the possessum variable is a stronger predictor for the relationship than the possessor variable.

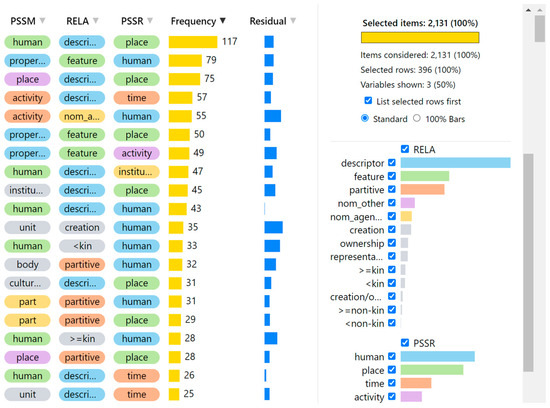

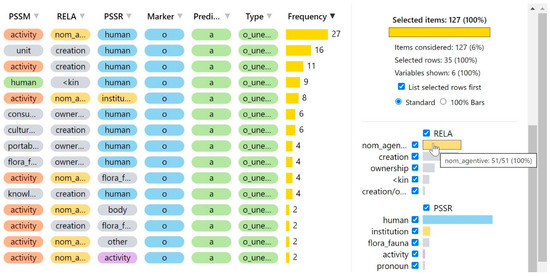

Next, we consider all three semantic variables (PSSR, PSSM, and RELA) at the same time. To achieve this, we employed a novel visualisation technique called MultiCat (Trye et al. 2024), which is designed for exploring several categorical variables simultaneously. Researchers can analyse their own datasets in MultiCat by following the instructions at https://github.com/dgt12/multicat. Figure 9 is a screenshot of the MultiCat interface showing the most frequent combinations of semantic categories in the Mixed Dataset; the full dataset can be explored interactively at https://dgt12.github.io/possession/. Each column in the visualisation represents a different variable and each row represents a distinct combination of categories (in our case, possessive phrases with the same characteristics). The ‘stickers’ within each column are coloured according to the relative ranking of each category within the corresponding variable: blue represents the most frequent category, followed by green, orange, purple, yellow, and then grey for all the remaining categories. Combinations are sorted by frequency, which is visually encoded by the yellow bars. The residuals in the right-most column show the extent to which each combination is over- or under-represented in the data, using blue and red bars, respectively. The sidebar on the right side shows the marginal frequency of each category, though not all data are visible. Users can select which columns to include in the visualisation; the screenshots in this paper show only those that are relevant at each point in the analysis.

Figure 9.

MultiCat visualisation of the 20 most frequent semantic category combinations for the possessum (PSSM), possessor (PSSR), and relationship (RELA) between the two.

The 20 combinations shown in Figure 9 account for 43% of the possessive phrases observed in the Mixed Dataset. There are, in fact, 396 different combinations of the variables PSSM, RELA, and PSSR, half of which occur just once. This means there is huge variation in the types of possessive phrases used in the data. Combinations that occur once or twice account for 63% of distinct configurations, while those that occur three times or fewer account for 71% of distinct configurations. The most frequent combination of the PSSM, RELA, and PSSR categories is human–descriptor–place, which occurs 117 times. Examples include te Kuini o Ingarangi ‘the Queen of England’ and ngā tāngata katoa o te ao ‘all the people of the world’. Yet, while this is the single most common combination, it accounts for only 5.5% of the data overall and roughly 13% of descriptor relationships (117/882). The second most frequent combination, which occurs 79 times, involves property–feature–human relationships, such as te mana o ngā tāne ‘the authority of the men’. Three of the top four combinations involve descriptor relationships, and two of these also have a place possessor. Interestingly, while nom_other relationships are more frequent than nom_agentive relationships, only the latter appear in Figure 9 (in an activity–nom_agentive–human relationship, e.g., te mahi a te tangata ‘the work of the people’), suggesting that nom_agentive relationships exhibit less variation with respect to the possessa and possessors that they take. The residuals in the right-most column are not particularly meaningful in this figure (or any subsequent figures), since all combinations are (seemingly) over-represented. The most over-represented combination is unit–creation–human, due to a proliferation of tweets where the possessum is te/ngā kōrero and the entire possessive phrase refers to speech produced by a specific person or group of people.

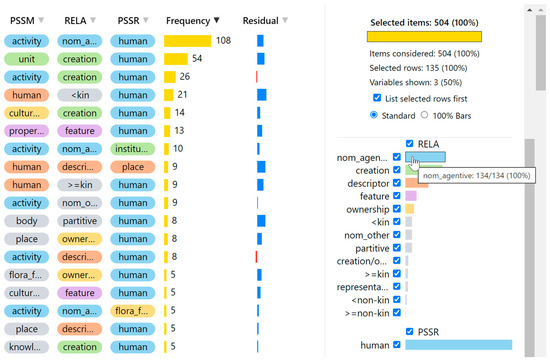

Figure 10 shows an equivalent MultiCat visualisation for the A-Only Dataset. There are 135 combinations attested in this dataset, with Figure 10 accounting for 64% of the tweets where users chose a. Notably, the vast majority of these combinations involve human possessors. Descriptor relationships, which are predicted to take O, are far less common here than in Figure 9, suggesting that people do not repeatedly use a in the same way for these relationships (though they do still unexpectedly use a for this category more than any other). The most common configuration for possessive phrases with an a marker—accounting for one-fifth of such phrases—is nom_agentive relationships involving an activity possessum and a human possessor; this is also the fifth most frequent combination in Figure 9. The second and third most frequent configurations with a markers are both creation relationships with a human possessor (e.g., ngā kōrero a Pāpā Timoti, ‘the words of Father Timothy’), which account for 11% and 5% of the data, respectively. Looking at the entire A-Only Dataset, nom_agentive and creation are the two most common relationships, and collectively make up half of all uses of a. Interestingly, all thirteen semantic relationships are represented at least once, even though most of these are associated with the O category (see Section 5.2).

Figure 10.

MultiCat visualisation of the most frequent semantic category combinations in the A-Only Dataset.

To summarise our main findings for RQ1, while the semantic make-up of possessive phrases varies considerably, they tend to be human-centric, typically involving either a human possessum or possessor (though not both at the same time). Descriptor relationships are prevalent in the Mixed Dataset, and are especially likely when the possessor is a place. Tweeters use a markings most frequently for nom_agentive and creation relationships.

5.2. Conformity with Descriptive Rules (RQ2)

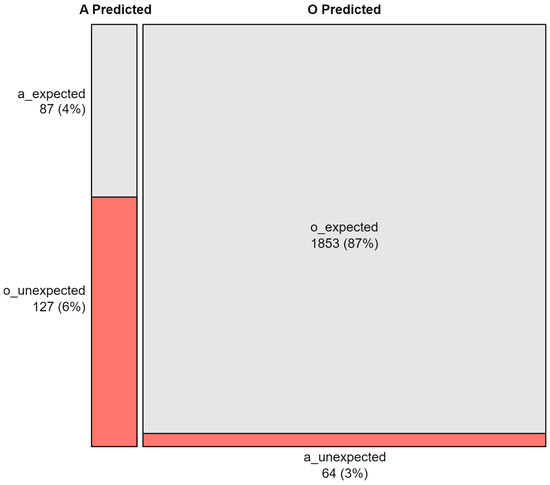

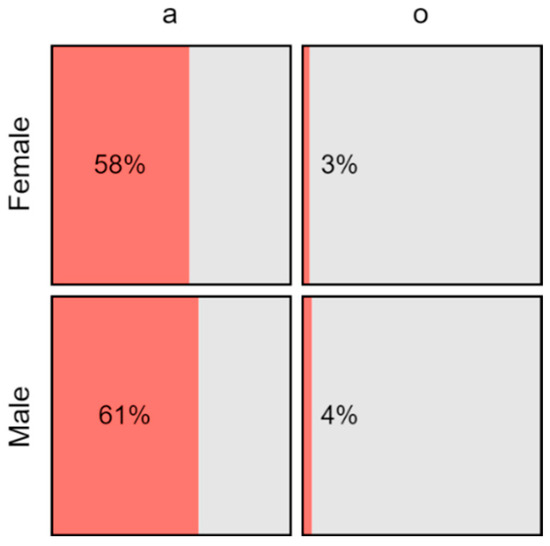

In this section, we analyse the extent to which A/O alternation in our data follows the rules described in Māori grammars, as per RQ2. We begin by considering the distribution of possessive markers in the Mixed Dataset; given our random sampling method, this should provide an indication of the ‘real’ distribution of possessive markers across different users. The dataset contains 2131 tweets, including 1980 instances of o (93%) and 151 instances of a (7%). In other words, there is a huge disparity of roughly 13 o markers for each a marker. Figure 11 displays a spine plot (similar to a mosaic plot) showing the composition of the Mixed Dataset with respect to the expected and actual markers used. The vast majority of tweets fall under the o_expected type (1853 tweets). More generally, tweeters use the expected marker 91% of the time (1940 out of 2131 tweets). However, this is clearly due to the extremely skewed distribution of the markers: O is the predicted category 90% of the time, and (as already mentioned) is used by tweeters 93% of the time. It follows that tweeters use the expected marker for tweets predicted to take O virtually all of the time; this is shown by the abundance of grey on the right side of Figure 11. In stark contrast, users adopt the expected marker for tweets predicted to take A only 41% of the time. In other words, while A-predicted tweets constitute only a small portion of the data (10%), among these tweets, there are more possessive phrases (59%) where o is used instead of a (o_unexpected) than phrases where a is used as expected (a_expected).

Figure 11.

Spine plot showing the proportions of predicted a and o markers, as well as the percentage of unexpected values (red) for each marker type.

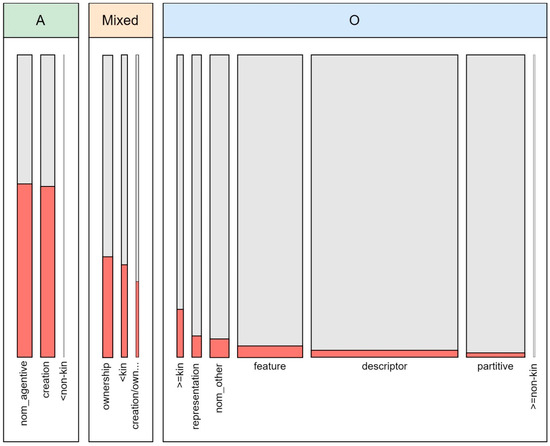

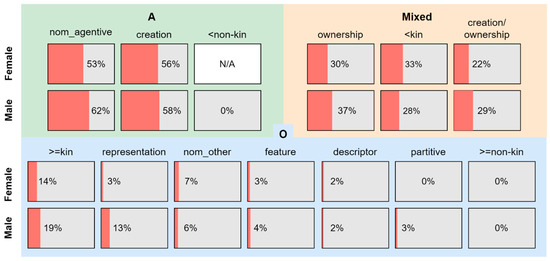

Figure 12 displays another spine plot, this time showing the relative frequency of each semantic relationship (the area of the tiles), together with their corresponding proportions of ‘unexpected’ markers (the proportion of red). The categories are grouped according to their predicted marker (‘A’, ‘O’, or ‘Mixed’), as derived from Figure 5. We placed <kin in the Mixed group, rather than the A group, due to the prevalence of uri ‘descendant’ in our data, which is expected to take O rather than A. The figure shows that the relationships expected to take A tend to have the highest ‘unexpected’ rates. The nom_agentive and creation relationships are, in fact, the only two categories for which people use the ‘unexpected’ marker more often than the ‘expected’ one (with ‘unexpected’ rates of 57% and 56%, respectively). Conversely, relationships that are expected to take (only) O have very low ‘unexpected’ rates, with none exceeding 16% (>kin) and all others being less than half of this value. The Mixed categories fall somewhere in between; unsurprisingly, most (75–82%) of their ‘unexpected’ values come from possessive phrases in which an a marker was predicted but an o marker was used instead. Overall, ignoring the very infrequent non-kin categories, users were most likely to use the expected marker for partitive and descriptor relationships. These findings suggest that people are increasingly using O forms in situations where grammars specify A forms.

Figure 12.

Spine plot showing semantic relationships grouped by predicted marker. Red indicates the proportion of each category with an ‘unexpected’ marker.

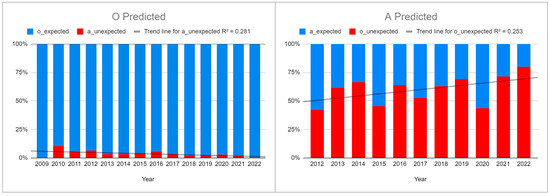

Given that most discrepancies between the usage described in grammars and observed in our data occurred when an o marker was unexpectedly used instead of an a marker (o_unexpected), we now focus on these specific cases. There are 127 such possessive phrases, which we acknowledge is a very small sample size. In line with the previous chart, Figure 13 shows that nom_agentive relationships attract the largest number of unexpected markers, although creation relationships are a close second. The prevalence of unexpected markers for nom_agentive relationships suggests that speakers may prioritise semantic information (i.e., the kinds of entities involved in a possessive relationship) over syntactic criteria (i.e., the type of verb). The most frequent combinations in which an o marker is used instead of an a marker are activity–nom_agentive–human relationships (27 instances, e.g., ngā manaakitanga *o te wāhi ‘the generosity of the place’), followed by unit–creation–human relationships (16 instances, all of which have a possessum associated with ‘words’). Nearly three-quarters of the o_unexpected phrases involve a human possessor (74%), and just under half use an activity possessum (48%), most of which are linked to a nom_agentive relationship.

Figure 13.

Recurrent configurations in which an o marker was used instead of an a marker.

One anonymous reviewer asked whether the patterns observed could be attributed to our characterisation of activity possessa. Looking at every tweet with an activity possessum across the Mixed Dataset, 69% of the data were predicted to take an o marker, and o was used as expected 96% of the time. However, among the tweets with an activity possessum predicted to take a, the a marker was used only 42% of the time. This suggests that tweets involving activities are indeed contributing to (possible) language change in progress regarding the use of the A/O categories.

Figure 14 shows the opposite kind of unexpected markers to Figure 13, whereby an a form was unexpectedly used instead of an o one, this time homing in on the A-Only Dataset. This applies to 40% of tweets in this dataset (n = 202); the other 60% (n = 302) are tweets for which an a marker was expected. The most common use of a instead of o is for property–feature–human relationships (13 occurrences; e.g., te riri *a Tāwhirimātea ‘the anger of Tāwhirimātea [the god of weather]’). The next most common relationships, with 9 occurrences each, are human–descriptor–place and activity–nom_other–human. The most unexpected uses of a occur with activity, property, or human possessa, which are also the three most frequent categories for which o is used, and, as with the inverse kind of unexpected marker, often with a human possessor (53%). Overall, descriptor relationships have the most unexpected a markers, followed by feature, nom_other, and partitive relationships.

Figure 14.

The most common configurations in the A-Only Dataset in which an a marker was used instead of an o marker.

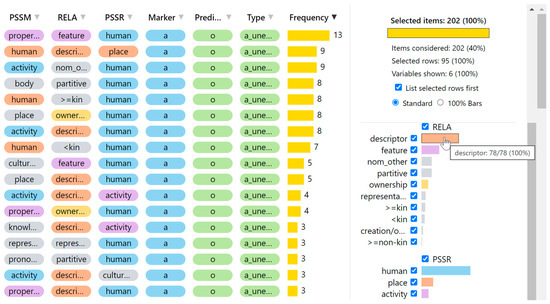

Since we have timestamps for all the tweets in our data, we can check whether there are any trends in the usage of the a/o markers across time. Figure 15 summarises the uses of each form in two panels: o on the left and a on the right. These are expressed as percentage splits between the expected form (in blue), which adheres to grammatical descriptions, and the unexpected form (in red), which deviates from grammatical descriptions. For example, for 2022, we can see that all uses of o were marked by the (expected) o form, whereas 80% of the expected uses of a were instead coded by o. The years 2009–2011 are excluded from the chart on the right, as there were only one to three a-predicted tweets in each of those years. In general, the o-possessives are marked according to the descriptions given in grammars, and increasingly so over time (the amount of red gradually decreases in the left panel), whereas a-possessives appear to be increasingly marked by o. The trend lines in each chart corroborate these findings, although the relationship is weak in both cases, as indicated by the R2 values of 0.281 and 0.253, respectively.

Figure 15.

100% stacked bar charts showing the proportions of expected and unexpected forms for each marker in the Mixed Dataset.

Overall, it would appear that Māori-language tweeters use o in most contexts, regardless of the inherent semantic relationship between the possessum and possessor, with users adopting the expected marker for tweets predicted to take a less than half of the time (41%) according to our Mixed Dataset. These findings support our hypothesis for RQ2.

5.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics of Tweeters (RQ3)

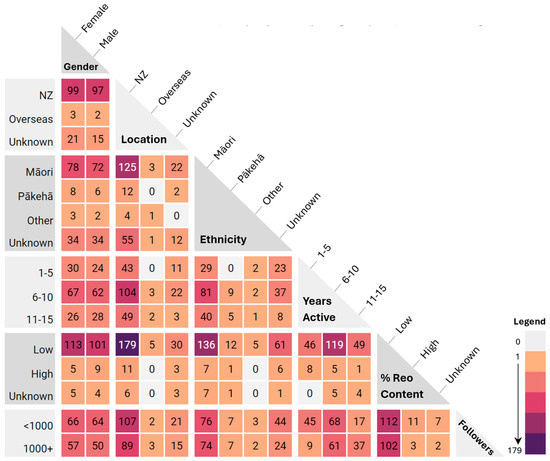

Our third and final research question relates to the social characteristics of Māori-language tweeters and whether there are any trends concerning their usage of a/o alternation. As a first step, it is useful to explore the macro-level patterns concerning all the available demographic variables for the users in our Mixed Dataset. Figure 16 provides such an overview. This visualisation, derived from the Heatmap Matrix Explorer (Trye et al. 2023; cf. Rocha and da Silva 2018), aims to provide a compact summary of a large collection of categorical variables, with darker values indicating higher counts of pairwise category intersections.

Figure 16.

Heatmap Matrix visualisation showing information about tweeters in the Mixed Dataset.

The following variables are included in the heatmap: Gender, Location (New Zealand vs. overseas), Ethnicity, Years Active (the number of distinct years for which the user has at least one tweet in the RMT Corpus), % Reo Content (Low: <40%, High: >=40%), and Followers (<1000, >=1000). Unfortunately, not all tweeters’ location, ethnicity, or percentage of Māori-language tweets were available, as indicated by the presence of the “Unknown” category. The exact age of each tweeter was not available, but we suspect that most users in the corpus fall within 25–55 years of age.

The two left-most columns in Figure 16 reveal a balanced distribution between male and female tweeters, both overall and with respect to each pairwise intersection. In other words, the number of male tweeters from each location, ethnicity, time interval, etc., is similar to the corresponding number of female tweeters. Similarly, there is a relatively even split between the number of tweeters with fewer and more than 1000 followers, though tweeters whose contributions span fewer than six distinct years in the corpus tend to have fewer followers.

It is evident from Figure 16 that most tweeters are based in New Zealand and of Māori descent, with only a small proportion of known Pākehā tweeters (roughly 6%). The location of these tweeters is expected, as New Zealand is the only place in the world where Māori is officially spoken (migrants who speak Māori can be found elsewhere, but only five such tweeters were identified in the Mixed Dataset). However, while most Māori-language tweeters are ethnically Māori, it is interesting to note that some Pākehā are also committed to supporting the language by using it on social media. The majority of tweeters contributed data to the RMT Corpus over a period from six to ten distinct years, demonstrating a sustained commitment to Māori-language tweeting. Notably, however, only 14 users tweet in Māori more than 40% of the time, and among them, only three have more than 1000 followers. Tweeters in the Low % Reo Content category may still tweet in Māori on a regular basis, just not as often as they post in English or other languages.

We now focus specifically on Gender, since we consider it to be the most interesting variable for which all values are known. Figure 17 compares the proportions of unexpected a and o markers produced by males and females. Contrary to our hypothesis, males produced slightly higher rates for both kinds of unexpected marker. Breaking this down further by each relationship (Figure 18), males produced larger proportions of unexpected markers for most relationships. A possible explanation for this is that women are more likely than men to learn Māori through formal education (Te Kupenga 2018), where the importance of the A/O categories is often emphasised. However, the differences are not large enough to be deemed statistically significant, which means that we cannot confidently conclude that males are less likely to use an expected marker than females (or vice versa).

Figure 17.

Proportions of ‘unexpected’ markers (red) for each predicted marker type, broken down by gender.

Figure 18.

Visual comparison of proportions of ‘unexpected’ markers (red) for each relationship, broken down by gender. The same bin size is used for ease of comparison.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

We begin this section with an overview of our findings. Using Twitter data and a combination of manual and automatic methods, we extracted and analysed A/O possessives of the form [possessum a/o possessor], such as te mahi a te tangata ‘the work of the people’ and ngā rangatira o Waikato ‘the chiefs of Waikato’. Our analysis uncovered a wide array of possessive types and tokens: users employ this construction to express possessa encoding humans, places, activities, properties, parts (of entities), and units, as ‘possessed’—either literally or metaphorically—by humans, places, time, institutions, and activities, among others (Figure 6). In other words, we find that users make full use of the varied semantic categories and a wide range of noun phrases. What may be a slight surprise in the range of categories expressed is the comparatively low frequency of kinship relationships mentioned. Given the chief importance that family (whānau) and genealogy (whakapapa) play in Māori culture, it may be unexpected to find so few occurrences of kinship in these data. However, this may be because we considered only a subset of the possessive domain, focusing on just one of several possible constructions. Kinship relationships are perhaps more likely to occur in other forms of possession, such as with possessive pronouns (tōu māmā ‘your mother’; ō māua mātua ‘our parents’).

A second aspect of interest, and, for some, of great concern given some of the negative publicity of the language used on social media (see discussion in Bleaman 2020), relates to the patterns of A/O alternation and their divergence from existing grammars and learner texts. With this being the first quantitative study (to our knowledge) of naturally occurring possessives in Māori, our findings confirm the frequently noted trend that O constitutes the unmarked category and A the marked one (Clark 1976, pp. 42–44; Bauer et al. 1997, p. 391; Harlow 2007, p. 168). Moreover, we find that users nearly always match descriptions in Māori grammars with respect to the use of o (97%), and where differences arise, these mostly concern the use of a (Figure 11 and Figure 12). In total, 42% of users in the Mixed Dataset do not use a at all, which is significant. Peering more deeply at constructions that would be A-marked according to grammars, we find that differences in use (i.e., the use of o instead of the expected a) are most frequent with nominalisations; in other words, in cases where deciding on the appropriate marker involves grammatical criteria rather than semantic notions.