Abstract

This study explores the correlation between social categories and linguistic variables, focusing on the perception of the discourse marker yeah-no in Australian English. Research suggests that these correlations reflect individuals’ recruitment of variables for the purpose of communicating social meaning. However, not all social categories which correlate with a variable in production are recognizable as social meaning. This study investigated how individuals’ positioning to a variable mediates their awareness to its social meaning by examining perceptions of gender and life-stage in yeah-no users and non-users. We found that individuals judged sentences including yeah-no as more likely to be said by a student, and this effect was stronger for individuals who did not self-report as yeah-no users. Furthermore, while there was no significant effect of gender, participants who did not self-report as yeah-no users were more likely to judge yeah-no sentences as said by a male speaker rather than a female speaker. The findings imply that the perception of social meaning is influenced by an individual’s positioning towards a variable. More broadly, the results provide support for using self-report techniques in the investigation of social meaning.

1. Introduction

Across communities of various sizes, correlations can be observed between linguistic variables and social categories. Linguists have sought to understand speakers’ motivations to use one linguistic variant over another, and in recent sociolinguistic investigations, referred to as third wave research (Eckert 2005), a focal point has emerged, whereby social meaning has been investigated as a force that motivates speakers to use certain linguistic variants (Agha 2003, 2007; Campbell-Kibler 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011; Johnstone and Kiesling 2008; Levon 2011; Moore 2004; Moore and Podesva 2009; Podesva 2011a, 2011b; Podesva 2007; Podesva et al. 2015; Zhang 2005, 2007, 2008). Podesva et al. (2015, p. 60) summarize this development succinctly: “third wave studies shift their focus from linguistic change to the social meanings that motivate speakers to use one linguistic variant over another”. In contrast to earlier sociolinguistic paradigms, labeled as first and second wave research, which scrutinize the interplay between linguistic variation and social or demographic categories at both macro and micro scales, respectively, third wave scholars posit that variables serve as resources for speakers in constructing identities, stances, and personas. This proposition builds upon Silverstein’s (1976) work, where it is argued that variables index associated social categories to generate meaning significant to certain speakers, particularly those engaged in communicative events. Consequently, proponents of third wave variation posit that the social meanings of linguistic variables are dynamic and adaptable, with their interpretation contingent on the contextual setting. For instance, the prevalence of the released variant of word-final /t/ among Orthodox Jewish men suggests that stop releases not only index learnedness but, within the cultural context studied, indirectly signify masculinity (Benor 2001, 2004). Consequently, adhering to the third wave expectation, Orthodox Jewish boys would release their word-final /t/s to convey a learned and masculine demeanor. While findings such as Benor’s have been observed across regional dialect labeling experiments (Clopper and Pisoni 2004; Baker et al. 2009; Cramer 2011) and social evaluation studies (Campbell-Kibler 2011; Podesva et al. 2015; Plichta and Preston 2015), it is not always the case that the social categories that correlate with a variable in production are recognizable as social meaning. In the current study, we sought to further this line of inquiry by investigating self-reported use as a factor that mediates the awareness of social meaning. That is, we investigated individuals’ positioning towards yeah-no in Australian English, targeting perceptions of gender and life-stage. Our hypothesis, rooted in two experiments, is that the successful perception of social meaning depends on an individual’s positioning towards a variable.

2. The Dynamics of Socially Indexed Linguistic Variables

The capacity of speakers to employ social meaning in the construction of identities, stances, and personas relies on two fundamental pillars. Firstly, there is the necessity for the linguistic variable to index social meaning, thereby implying the social category along with any other semantic contributions (e.g., context-free truth-conditional meaning). Secondly, individuals must, across a speech community of any given size, possess an awareness of the indexed social meaning for the variable to successfully serve as a tool for identity, persona, or stance construction. If either of these two fundamental pillars is problematic or non-existent, individuals could still produce the form as a result of imitative social conditioning, but the intended social information would be opaque. For instance, consider the English quotative be like. This variable has been shown to correlate with social categories, such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status (Dailey-O’Cain 2000). If these categories are indeed socially indexed onto the variable in addition to its quotative meaning, it implies that individuals possess an awareness of this additional meaning, be it unconscious or conscious knowledge. Explicit and conscious knowledge would suggest that speakers can utilize be like to construct specific identities related to the indexed social meaning. However, such sociolinguistic performance becomes ineffective if individuals lack awareness of the potential indexed meaning. In Buchstaller (2006), British listeners were shown to be able to determine the age and gender of a speaker from quotative be like use, suggesting that individuals in Britain employed be like to construct identities in relation to age and gender. However, while socioeconomic status was also shown to be a correlating social category with the variable in production, listeners were unable to deduce this meaning from quotative be like use, at least not in an overt manner, and were thus unable to employ be like to construct identities in relation to socioeconomic status.

The process of indexicalization is consistent with usage-based approaches to language learning, notably exemplar models. Within this framework, exemplar models propose that individual speech utterances accumulate in memory as exemplar representations, incorporating comprehensive linguistic and non-linguistic information (Bybee 2001; Foulkes and Docherty 2006; Goldinger 1997, 1998; Johnson 1997, 2006; Pierrehumbert 2001, 2002). This aggregation allows for the mapping of relevant social categories onto each exemplar, which has been observed in studies of psychology and, more recently, those in the field of linguistic inquiry (Drager 2005; Foulkes and Docherty 2006; Hay et al. 2006a; Johnson et al. 1999). Exemplar representations are theorized to be stored in an individual’s mind and can be accessed during both speech production and perception, a phenomenon which has also been supported by linguistic research (Hay et al. 2006a, 2006b; Johnson 1997; Pierrehumbert 2001). Thus, according to usage-based approaches to language learning, speakers can produce forms that index corresponding social categories and perceive the associated social categories. Returning to the example given above of Orthodox Jewish men’s released /t/ patterns, exposure to such correlations in speech production creates a mental representation of the released /t/ and its associated social categories: religion, education, and gender. In accordance with exemplar theory, it is expected that speakers could then employ this knowledge as a stylistic device to craft a specific social persona.

Experiments in regional dialect labeling have provided evidence to demonstrate individuals’ overt awareness of social categories that correlate with variables (Baker et al. 2009; Cramer 2011; Fuchs 2015; Kirtley 2011; Purnell et al. 1999; Suárez-Budenbender 2009). Clopper and Pisoni (2004) focused on the ability of Indiana college students to accurately categorize six North American regional dialects. Although general identification accuracy among listeners was relatively low, the participants’ responses surpassed chance levels statistically. Notably, speakers who had lived in at least three different states exhibited higher accuracy compared to those limited to Indiana. Moreover, individuals who had lived in a particular region demonstrated a more precise categorization of talkers from that region than those without such residency experience. Furthermore, social evaluation studies have shown that listeners possess a capacity to recover social meanings from linguistic variables (Campbell-Kibler 2007, 2008, 2011). Campbell-Kibler specifically investigated the impact of the sociolinguistic variable (ING) (e.g., walkin’ vs. walking) on listeners’ attitudes towards speakers by manipulating the realization of the final nasals in (ING). This manipulation influenced listeners’ judgments about the speaker, though results diverged from prior studies on the social stratification of (ING). While Campbell-Kibler identified the associated social categories, including education and intelligence, previous research also linked (ING) to gender, socioeconomic status, dialect, age, and race (Fischer 1958; W. Labov 1966; Shopen 1978; Shuy et al. 1967; Trudgill 1974). In addition to (ING), this inconsistency between production patterns and individuals’ awareness extends to other linguistic variables such as t/d deletion in English (Baugh 1979; Campbell-Kibler 2005; G. R. Guy and Boyd 1990; W. Labov 1972c; Rickford 1986; Staum Casasanto 2010; Wolfram 1969), quotative and focuser like (Buchstaller 2006; Dailey-O’Cain 2000), fundamental frequency (Kirtley 2011; Linville 1998; Smyth et al. 2003), and /ay/ monophthongization (Kirtley 2011; Plichta and Preston 2015; Rahman 2008). It is this inconsistency that prompts questions about why individuals exhibit awareness of the association between some linguistic variants and social categories but not all.

The context of a variable has been investigated as an explanation for individuals’ inability to overtly deduce social meaning that is expected to be indexed onto a variable. Speech, being inherently social, unfolds between speakers and interlocutors, whose interpretations of meaning hinge on their experiences, social positions, and goals. Campbell-Kibler’s research (Campbell-Kibler 2007, 2008, 2011) exemplifies this, demonstrating that listeners rate speakers who use the alveolar variant of (ING) as compassionate when they perceive the speaker to be Southern but condescending when they perceive the speaker to be from elsewhere. Social information about the speaker also influences how listeners perceive the speech of an individual (Hay et al. 2006a, 2006b; Hay and Drager 2010; Koops et al. 2008; Niedzielski 1999; Strand 1999). In Hay and Drager (2010), New Zealand English speakers were exposed to either stuffed toys associated with Australia (kangaroos and koalas) or toys associated with New Zealand (stuffed kiwis) during a vowel perception task. Participants showed a shift in their perception boundaries according to which set of toys they were exposed to, i.e., participants matched natural vowels with more Australian-like synthesized vowels when they were in the Australian “kangaroo” condition. Recently, Sherwood et al. (2023) furthered the examination of context as a factor which influences individuals’ perception of speech and indexed social meaning to the situational context, i.e., the place where the utterance was spoken. While they found evidence to support that individuals form associations between the gender of a speaker and prescriptive variables in Japanese speech communities, knowledge of the context of the variables had no significant effect on individuals’ judgements.

Crucially, however, one of the most striking findings in the Sherwood et al. (2023) study was the ease by which prescriptive forms in the speech community were perceived by participants. This finding is in line with W. Labov’s (1972b) proposed model of social salience which delineates three variable types, demarcated by speakers’ awareness of their existence. The first level are indicators, which show zero degree of social awareness and are therefore difficult to detect for both linguists and native speakers. Markers are usually socially stigmatized forms characterized by sharp social stratification across groups and styles. The highest level of social awareness for variables is the stereotype category. Stereotyped forms display both social and stylistic stratification and are subject to explicit meta-commentary due to their overt level of social awareness in the speech community. The salience of a variable in the speech community therefore offers a clear explanation for why a certain variable’s expected social meaning may not be detectible by listeners. That is, if the variable is non-salient at the indicator level, its associated social meaning(s) may not be learned by the listener. What remains to be investigated along this line of inquiry, and what was not within the scope of Sherwood et al. (2023), is the extent to which stereotyped attitudes and beliefs about a certain variable may influence listeners’ evaluative judgements.

In Levon (2014), stereotyped attitudes and beliefs about groups of speakers were examined as factors that could influence listeners’ evaluative judgements. The attitudinal and cognitive factors targeted in this study were in reference to listener endorsements of normative stereotypes pertaining to male gender roles. Listeners who endorsed normative stereotypes of masculinity and male gender roles used pitch and sibilance as salient cues which signaled ”nonmasculinity” and ”gayness”; however, listeners who did not identify with these stereotypes showed no effect for pitch and sibilance. This finding suggests that when individuals desire to conform to socially accepted norms, they are more likely to interpret linguistic features in ways that align with these norms, thereby reinforcing stereotypes. Individuals have also been shown to be aware of stereotyped linguistic features to the extent that they claim to use these features differently than they actually do in their speech. In W. Labov (1966), speakers from New York showed a tendency to report a higher usage of standardized forms than their actual usage. The opposite effect was observed by Trudgill (1972), where men from Norwich reported a higher use of non-standardized forms than their actual usage. Given the findings pertaining to social stereotyping, both of groups of speakers and of variables themselves, the role of social desirability presents an interesting line of enquiry. Individuals’ endorsement or positioning towards a linguistic variable, where some may identify as users of the variable and others may not, could offer an explanation as to why some correlations between variants and categories are detectable by speaker–listeners, and thus are available for use for the purpose of identity construction, while other correlations are not. Therefore, this study aims to determine how individuals’ positioning to a variable mediates the awareness of social meaning within a language community where not only the correlating social categories are salient but also the linguistic variable itself.

3. Life-Stage, Gender, and Yeah-No

To investigate the role of social positioning on judgements of social meanings, our study design incorporated specific constraints essential for hypothesis testing. The first constraint was that, to gauge an individual’s positioning effectively with respect to a variable, it is imperative that the variable in question holds salience within the community, either as a stereotype or a socially significant marker. Consequently, we opted for the marked and stereotyped discourse marker in Australian English, yeah-no, as our chosen variable for examination. The second constraint pertains to the social categories in focus. While it is acknowledged that linguistic variables can index multiple complex, dynamic, and contextually dependent social categories, we deliberately limited our analysis to two potentially indexed meanings of the Australian English discourse marker: age and gender. This study’s emphasis was on exploring the role of social positioning rather than delving into the subtle nuances of the chosen variable. Thus, we underscore that the chosen design and methods align with the research aim’s scope and subsequently encourage future investigations to delve deeper into this line of inquiry by exploring yeah-no and other variables with consideration for styles and their respective indexical fields.

As continuous variation in the phonetic realization of vowel allophones is the most heavily employed resource for the construction of social meaning in English (Eckert and Labov 2017), it is no surprise that the majority of the research that examines the communication of social identities has largely focused on vowel allophones. There are, of course, many studies which examine variables of different linguistic levels and their correlated social meaning(s), for example, but not limited to, consonant allophones (Benor 2001, 2004; Campbell-Kibler 2007, 2008, 2011; Podesva et al. 2015), quotatives (Buchstaller 2006; Dailey-O’Cain 2000), intensifiers (Bauer and Bauer 2002; Stenström 1999; Stenström et al. 2002; Tagliamonte 2005), and discourse markers (Andersen 2001; Erman 1997, 2001; Macaulay 2002; Tagliamonte 2005). This paper contributes to the investigation of social meaning by examining the understudied discourse marker yeah-no in Australian English.

To date, yeah-no, like other discourse features, has received very little attention in linguistic research, despite its salient reputation in the speech community. Labeled as “speech junk” (Campbell 2004) and a “verbal crutch - an epidemic from which no strata of society is immune” (The Age 2004), yeah-no had a very negative reputation in the early 2000s. More recently, however, it has received more positive attention as the punchline of a road safety campaign in which the advertisements would conclude with “Say ‘Yeah… NAH’ to taking risks” (Kelly 2018), and the variable was considered to be the ABC’s second greatest Aussie slang word or phrase in a 2021 listener poll (Hughes et al. 2021). In studies that have sought to better understand the variable in terms of its linguistic distribution, yeah-no has been shown to serve a number of functions in speech, including discourse cohesion, the pragmatic functions of hedging and face-saving, and assent and dissent (Burridge and Florey 2002). Burridge and Florey performed a corpus analysis of formal conversation and interviews, examining the interplay between intonation and turn-taking, along with the usage of yeah-no in relation to topic, conversational genre, and the age and gender of the speaker. In their study, Burridge and Florey also examined the variant forms of yeah-no which include yep-no, yes-no, and yeah-nah, and occurrences of yeah-no with additional markers of agreement—for example, yeah yeah yep-no. The stratification of their results demonstrated a higher frequency of yeah-no use in speakers between the ages of 18–49 years of age (25% of speakers produced the variable), with a slight preference for the 35–49 age range (25.6%) compared to the 18–34 range (23.5%). In terms of gender, Burridge and Florey speculated that, given the interactive politeness phenomena of yeah-no, a gender difference would be apparent in the distribution of the results. However, no differences were apparent at the conclusion of the study. It is also worth noting here that the size of the corpus in the Burridge and Florey study was limited with respect to investigating a potential age stratification. Specifically, there was a difference in yeah-no use between formal and informal interactions among younger speakers (18–34 years); however, only five tokens of yeah-no were produced and only in a television and film setting.

Moore’s (2007) study, incorporating data from radio and television broadcasts, the Australian International Corpus of English corpus, and the Monash University Australian English Corpus, showed similar findings, particularly regarding the influence of age. Notably, however, a higher frequency of yeah-no usage was observed among male speakers, constituting 85% of tokens, compared to female speakers. While other social categories have not yet been explored in relation to yeah-no, both Burridge and Florey and Moore speculate that a potential socioeconomic and style stratification may be present in the distribution of yeah-no. Ultimately, due to its salience in the speech community, either as a stereotype or a socially significant marker, yeah-no satisfies the first constraint required by this study. The results of Burridge and Florey (2002) and Moore likewise demonstrate that yeah-no has the potential to socially index the categories of age and gender due to their correlations with the variable in natural spoken speech, satisfying the second constraint employed in the study.

Studies that have investigated the role of age in the social stratification of linguistic variables have found that there are strong correlations with sociolinguistic variables. Sound change and slang terms have been among the most frequently studied (Bucholtz 2001; Cheshire 1982; Eble 1996; Eckert 1988; T. Labov 1992), with research extending past the scope of age-related research into a wider range of features including quotatives go and be like (Macaulay 2001; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004), intensifiers (Bauer and Bauer 2002; Stenström 1999; Stenström et al. 2002; Tagliamonte 2005), and discourse markers (Andersen 2001; Erman 1997, 2001; Macaulay 2002; Tagliamonte 2005). While far fewer in number, age has also been explored in evaluation studies. Listeners have been shown to judge the age of speakers according to the linguistic variables used in their speech (Buchstaller 2006; Dailey-O’Cain 2000; Walker 2007). Despite the clear prominence of age in the literature, social category can present methodological issues. Age as a category can be represented along a scale of continuous apparent time, but there are normative hallmarks that can be divided into life stages to represent individuals’ progress through time (Eckert 2018). Community studies (Macaulay 1977; Wolfram 1969) found evidence to suggest a divide between preadolescents and adolescent age groups in the stratification of linguistic variables. Variationists have also examined the significance of life stages with regards to linguistic variation (Eckert 1988; W. Labov 1972a, 1972b).

Wolfram’s study of African American Vernacular English in Detroit, specifically, found that the adolescent age group (14–17 years) in the study used fewer phonological, morphological, and syntactic variables than both the preadolescent group (10–12 years) and the adult group. Across the eleven variables that were examined according to age group and socioeconomic class, word-final t and d, 3rd singular -z, and double negatives were all examples of variables that did not show social stratification in the adolescent group compared to the preadolescent and adult groups. This discrepancy has been attributed to socioeconomic mobility, with Eckert (1988) suggesting that the lack of variables used in the adolescent sample reflects a relatively smaller relevance of parental socioeconomic class to adolescent social identity. Therefore, the use of a continuous analysis could present problems for participants, as they may struggle to distinguish between seemingly arbitrary landmarks according to age in years. Age as a categorical variable, however, offers an interpretive lens that can both aid participants in making their judgements and provide normative landmarks which may contribute towards a better understanding of other social categories indexed by yeah-no, such as the predicted socioeconomic and style stratification correlates proposed by Burridge and Florey (2002) and Moore (2007).

Gender, like age and life-stage, has also been widely researched in the domain of sociolinguistics. We would like to note the distinction here between gender, a constructed ideology that depends on perception, and sex which is a biological category. Both have been examined in the variationist literature; however, while some studies specifically distinguish between biological characteristics and social factors (e.g., Chambers 1992, 1995), the majority often have an overlap between the two. Where possible, we distinguish between ”sex” when discussing research that relies on a simplistic classification of speakers into males and females, and ”gender” when describing research that takes at least some account of relevant social and cultural factors. Gender, unlike sex, abstracts over a range of globally and locally constructed speaker–listener practices (Eckert and Labov 2017) and is claimed to be as impactful to the constructions of identity as the dimensions of region and age (Podesva and Kajino 2014). In one of the foundational studies to examine variations with speaker sex in production, Fischer (1958) found that girls consistently used more of the perceived standard form of the (ING) variable [ɪŋ] than boys, a pattern that was later discussed by W. Labov (2001) as a preference for women to use more standard variants than men. In addition to prestige, a number of sociolinguistic variables have been studied in connection with sex and gender, for example, the Northern Cities Chain Shift (Eckert 1989), high-rising terminals in Australian English (G. Guy et al. 1986) and in New Zealand English (Britain 1992), and glottal stops in British English (Milroy et al. 1994). Sex and gender have also been studied in other languages within a sociolinguistic framework. Some examples include phonological, morphological, and lexical differences between male and female speakers of Koasati (Haas 1944), monophthongs and diphthongs in the speech of women from Tunis (Trabelsi 1991), and patterns of non-palatized [l] in Crete (Mansfield and Trudgill 1994). Listeners’ evaluative judgements of speech with reference to sex and gender have also been investigated (Owren et al. 2007; Traunmüller 1997; Whiteside 1998), as has the perception of sexual orientation (Clopper et al. 2006; Levon 2007; Smyth et al. 2003; Squires 2011). For example, Smyth et al. (2003) examined listener judgements pertaining to gender for varying discourse types and associated stylistic features. The results showed a main effect of discourse type, where more formal speaking styles were judged as more “homosexual” sounding, which had an interaction with the speaker’s sexual orientation. That is, straight speakers were judged to be more homosexual sounding when reading a scientific passage. Ultimately, as with age and life-stage, the category of gender can thus be found as a correlate in the production of linguistic variables, as well as a social meaning that is detectable from exposure to the variable in speech, making it an ideal category of study in the present research.

Therefore, this study investigates how individuals’ positioning to a variable mediates the awareness of social meaning by examining social evaluations of gender and life-stage in yeah-no users and non-users. In two evaluation experiments, we examine whether native Australian speaker–listeners associate life-stage (Experiment A) and gender (Experiment B) with the discourse marker yeah-no in Australian English and the role that positioning plays in these associations. We use individuals’ self-reported use of the variable as evidence of their social positioning towards the variable. It is worth noting here that we do not consider reported use as actual production. As discussed above, speakers have been shown to report higher usage of standardized forms than their actual usage (W. Labov 1966). Given that yeah-no is a stigmatized variable in the speech community, it is expected that it will pattern according to what is considered to be socially desirable in the community, whether that be using (or not using) yeah-no in speech. If speaker–listeners show a difference in their evaluations of the social meaning with regards to their positioning to the linguistic variable, either as a user or a non-user of yeah-no, it would suggest that positioning is a contributing factor to the attitudinal and cognitive factors that mediate the awareness of social meaning.

4. Experiment A

This first experiment was designed to test the hypothesis that there is an effect of life-stage on individuals’ judgements of speakers who use the discourse marker yeah-no. Our expectation was formed on the basis that yeah-no is a marked and stereotyped discourse marker in Australian English which has been previously shown to correlate with age. As age as a category can be represented along a scale of continuous apparent time, we established two normative hallmarks that could be used to represent individuals’ progress through time to allow us access to an interpretive lens that could both aid participants in making their judgements and provide normative landmarks which may contribute towards a better understanding of other social categories indexed by yeah-no, such as the predicted socioeconomic and style stratification. Specifically, we examined if individuals judge speakers who use yeah-no as more likely to be students or employees. Given that younger speakers have a tendency to use yeah-no more often than older speakers (Moore 2007), and that age plays an overall factor in the social stratification of yeah-no (Burridge and Florey 2002), we expected that participants would judge utterances of yeah-no as more likely to be said by a speaker at a younger rather than older life-stage; that is, speakers who are students. To investigate the role of positioning, we conducted an online study that included an evaluation task and a self-report questionnaire to elicit whether the subject was a yeah-no user or a non-yeah-no user.

4.1. Experiment A Materials and Methods

The participants were recruited primarily through word of mouth and online networking sites that were circulated through the researchers’ friend networks, mostly via Facebook and Twitter. A total of 65 native Australian English participants (32 male; 33 female) took part in this experiment, with an age range of 18 to over 75 years at the time of testing (see Table 1). An additional 15 participants completed the study but were not included in the analysis. Of these, 14 were excluded as non-native Australian English speakers. The remaining speaker was excluded as a non-serious attempt, where all answers, including the controls, were answered as neutral. A number of 18 participants were students at the time of testing, and 47 reported that they were employees.

Table 1.

Experiment A: the number of participants according to age and reported gender.

The stimuli included in the evaluation task consisted of a set of 120 sentences comprising three different condition types: YEAH-NO, LEXICAL CONTROL, and FILLER. The complete list of sentences appears in the Appendix A and Appendix B. The YEAH-NO condition was designed to examine if participants varied in their judgement between the linguistic variables yeah-no and yeah. The LEXICAL CONTROL condition tested if participants were able to complete the task appropriately, as the distinction between the two levels was overt through the use of lexical choices. The FILLER condition contained sentences that did not include the discourse markers being tested or the lexical items in the control condition; rather, they contained various lexical and semantic items to distract the participant from the YEAH-NO condition items. This was conducted to achieve the most natural response possible for the YEAH-NO stimuli.

Twenty sentences were used in the YEAH-NO condition and were identical, apart from the sentence-initial discourse marker (10 sentences × 2 variations [yeah-no, yeah]). The sentences were all positive with the variable in the initial position and were followed by content indicative of responding to an interlocutor in order to be consistent with the previous yeah-no literature (Burridge and Florey 2002; Moore 2007). For example, “Yeah no, they’ll love it” was one of the variations from the 10 yeah-no sentences.

Twenty sentences made up the LEXICAL CONTROL condition and varied by one lexical choice that evoked the concept of life-stage (10 sentences × 2 variations [student, employee]). An example of one of the pairs used as stimuli was “I have to go to class tomorrow” for students and “I have to go to work tomorrow” for employees. The LEXICAL CONTROL condition also aided in guiding the participant towards making a distinction between the two life-stages which can involve some overlap; that is, students could be participating in part-time employment, and employees could be undertaking study by correspondence. The remaining 80 sentences made up the FILLER condition. All stimuli items were checked by three native speakers to confirm the sentences reflected natural speech and were grammatically correct.

The participants performed the tasks in the format of an online survey administered by Qualtrics online survey software (Version May, 2015). All instructions, materials, and stimuli were presented in English. Participants were able to choose the device (computer or mobile device), location, and time of day they wanted to perform the task. By providing these freedoms for the participants and removing an interviewer from the procedure, we hoped to avoid complications known to arise from the observer effect (W. Labov 1972c). On average, it took the participants 13 min to complete the online survey.

In the first section of the survey, the task was to judge if the presented sentence was more likely said by a student or an employee. The participants were instructed to use a five-point adjective scale to indicate if the sentence was more likely said by a student, indicated by a (1) on the left of the adjective scale, or by an employee, indicated by a (5) on the right of the scale. The odd number provided participants the opportunity to indicate a neutral judgement of the sentences, an option that would not be possible with a forced choice method. Each sentence was presented in written form to the participant, one at a time, in a pseudo-random order. That is, stimulus items from the same condition type were not paired together. Written speech was used as opposed to audio recordings to ensure that participants made their judgements on the sentences alone, without the use of acoustic characteristics to influence their judgements. For example, vowel formant frequencies are lower, bandwidths are wider, and the fundamental frequency is generally lower for male speakers (Hillenbrand et al. 1995).

The second section of the online survey was a self-report task, in which participants were asked to select from one of four available options to respond to a speaker’s question. The questions and responses are provided in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D. There were 10 questions in total and the four responses included four sentences that were identical apart from the sentence-initial variable. The options included (1) the discourse marker yeah-no, (2) yeah, (3) no, and (4) no sentence-initial variable. The aim of this section was to identify if the participant was someone who self-reports as a yeah-no speaker in order to test the role of positioning in the awareness of social meaning.

The final section of the survey was designed to collect participants’ demographic data, including their age, gender, occupation, birthplace, where they grew up, and whether they were studying at a university. This information was collected in the third and final section of the survey to both allow participants to fully understand the task before asking them to provide their demographic information and avoid the possibility of the participant’s judgements being influenced by the content of these questions.

4.2. Experiment A Results

4.2.1. Mean Judgement Scores for Discourse Markers

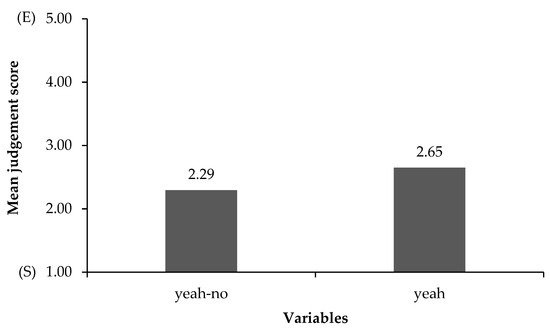

Figure 1 shows the mean adjective scale judgement scores for the discourse markers yeah-no and yeah. Higher mean judgement scores indicate that participants judged the sentences as more likely said by a speaker whose life-stage is an employee, while lower mean judgement scores are more likely judged by the participants as a speaker whose life-stage is a student. A score of 3 suggests that participants do not associate the respective variable with the social category of life-stage. Overall, yeah-no sentences were judged as more likely said by a student (2.29) compared to yeah sentences which were closer to no difference between life-stages (2.65). A Mann–Whitney U Test was conducted to assess the statistical reliability of the differences shown in Figure 1. The test indicated that the dependent measure of mean judgement scores was greater for the yeah condition (Mdn = 2.3) than for the yeah-no condition (Mdn = 2.9): U = 522.5, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.099. This confirms our hypothesis that speaker–listeners can use the discourse marker yeah-no to deduce the life-stage of the interlocutor.

Figure 1.

Mean judgement score by condition. Judgement scores ranged from 1—student (S) to 5—employee (E).

4.2.2. Mean Judgement Scores for Discourse Markers by Self-Reports

In the self-report section of the online study, the participants were asked to select from one of four available options to respond to a speaker’s question. The options included (1) the discourse marker yeah-no, (2) yeah, (3) no, and (4) no sentence-initial variable. We coded participants who selected yeah-no as a response to the speaker’s questions at least once as yeah-no users and those who did not choose yeah-no as non-yeah-no users. In greater detail, participants selected yeah-no responses infrequently, with variability in the number of selections spanning from none to a maximum of four instances. It is also worth noting that the spread of responses among the middle 50% of participants suggests a consistent trend towards limited usage (IQR = 1). As discussed above in Section 3, traditionally, self-reports run the risk of collecting unnatural reflections of speech, as the speaker can respond with their socially desired response, which may not reflect their actual usage. However, for this study, we were specifically interested in speaker–listeners’ positioning, that is, whether they indicated a preference to use the discourse marker yeah-no in their speech as well as their evaluations of marker’s social meaning. In particular, we sought to investigate whether speaker–listeners’ positioning to the variable mediates their evaluations. For this next analysis, we thus separated yeah-no users from non-yeah-no users to compare their mean judgement scores.

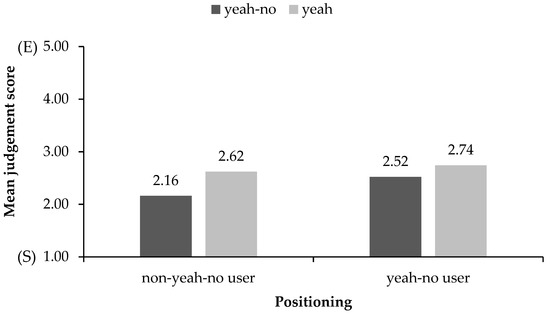

The results presented in Figure 2 show the mean judgement scores for the discourse markers by the self-report status of the participants, yeah-no users and non-yeah-no users. For both groups, yeah-no sentences were judged as more likely said by a student compared to yeah sentences. The difference between the mean judgements varied according to the group. For non-yeah-no users, the difference between the variables was 0.46 and was statistically significant (U = 522.5, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.073). The yeah-no users, on the other hand, had a 0.22 difference between the variables and the difference was not statistically significant (U = 276.5, p > 0.25, η2 = 0.025). These results show that the effect of form on speaker–listeners’ judgements of yeah-no is only present for those who do not self-report as yeah-no users. Yeah-no users, contrastively, only show a slight tendency to judge the variable as being more likely said by a student. Thus, the participants’ positioning to the variable impacted their judgements of its social meaning. The significance of these findings will be evaluated in the Discussion. However, before doing so, we turn to the second experiment in this study which examines individuals’ positioning to yeah-no in terms of their judgements of speaker gender.

Figure 2.

Mean judgement scores for discourse markers by self-report identification. Judgement scores ranged from 1—student (S) to 5—employee (E).

5. Experiment B

Experiment B investigated if there is an effect of gender on speaker–listeners’ judgements of speakers who use the discourse marker yeah-no, and if the participants’ positioning to the variable plays a role in their evaluations. Specifically, we aimed to examine if speaker–listeners’ judge speakers who use yeah-no as more likely to be male or female and whether the participants’ positioning, as a yeah-no-user or a non-yeah-no-user, mediates this judgement. The previous literature has been inconclusive as to whether there is an effect of speaker gender on yeah-no production. While Burridge and Florey (2002) reported that there was no difference between the gender of the speaker and the production of yeah-no, Moore (2007) found that there was an effect. Specifically, males used yeah-no more frequently than females. We therefore expect to find that speaker–listeners judge utterances of yeah-no as more likely to be said by a male speaker, but that this effect will be small. To test this hypothesis, we conducted an online study that was similar to Experiment A with minor revisions to test for the social category of gender.

5.1. Experiment B Materials and Methods

A total of 55 native Australian English participants (25 male; 30 female) took part in this experiment, with an age range of 18 to between 66 and 75 years at the time of testing (see Table 2). A number of 21 participants were students at the time of testing, and 34 volunteered that they were employees. Again, the participants were recruited primarily through word of mouth and online networking sites, such as Facebook and Twitter. An additional 12 participants completed the study but were not included in the analysis. Eight were excluded as non-native Australian English speakers. The other four participants were excluded as non-serious attempts.

Table 2.

Experiment B: the number of participants according to age and reported gender.

The stimuli and design of Experiment B were identical to Experiment A, with only a revision to one stimulus condition to examine the social category of gender rather than life-stage. The complete list of sentences appears in the Appendix C and Appendix D. The yeah-no and filler conditions were identical; however, the lexical control condition was revised to test the social category of gender on two levels, male and female (10 sentences × 2 variations [male, female]). An example of one of the stimulus pairs was “I’m working as a waiter” for male and “I’m working as a waitress” for female. The labels on the adjective scale were also amended to reflect this change, with the poles of the adjective scale labeled for male (1) and female (5).

5.2. Experiment B Results

5.2.1. Mean Judgement Scores for Discourse Markers

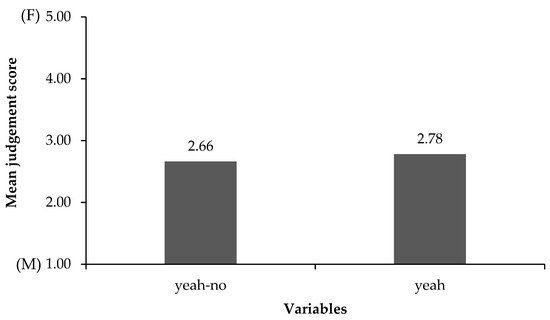

Figure 3 shows the mean judgement scores for the discourse markers yeah-no and yeah. Higher mean judgement scores indicate that participants evaluated the sentences as more likely said by a female speaker. Yeah-no sentences were judged as slightly more likely to be said by a male speaker (2.66) compared to yeah sentences which were closer to no difference between the gender of the speaker (2.78). Both means, however, are close to a neutral score of no difference between genders. This result reflects the findings in Burridge and Florey (2002). That is, there was no overt difference in terms of speaker gender between the discourse markers, despite an effect of gender being found in Moore (2007). A Mann–Whitney U Test reflected the described observation, specifically, that there was no significant difference between the markers, yeah-no and yeah, (U = 1291.5, p > 0.1, η2 = 0.016).

Figure 3.

Mean judgement score by condition. Judgement scores ranged from 1—male (M) to 5—female (F).

5.2.2. Mean Judgement Scores for Discourse Markers by Self-Reports

We again separated yeah-no users from non-yeah-no users to compare mean judgement scores according to the participants’ positioning. As with Experiment A, participants selected yeah-no responses infrequently, with the variability in the number of selections spanning from none to a maximum of five instances. The middle 50% of participants in this experiment, however, suggests a consistent trend towards a slightly higher usage (IQR = 2).

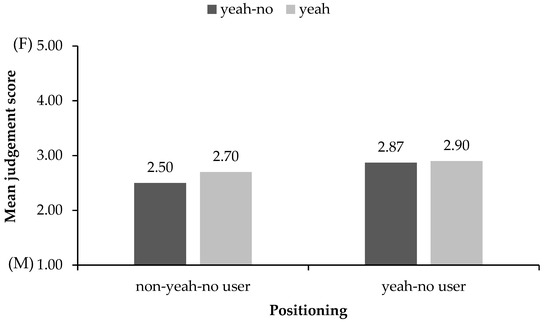

Figure 4 shows the mean judgement scores for the discourse markers by the self-report status of the participants, yeah-no users and non-yeah-no users. There is a very minor difference between the mean judgements of the yeah-no users (0.03), which is reflected in the non-significant result of the Mann–Whitney U Test (U = 238.5, p > 0.5, η2 = 0.007). The pattern was consistent for the non-yeah-no users (U = 434.5, p > 0.2, η2 = 0.017). For both user groups, the judgements were close to the neutral judgement of 3 on the adjective scale, which represents no difference between forms when judging the gender of the speaker. The slight difference between the user groups suggests that speaker–listeners who do not self-report as users of yeah-no may still have a sensitivity to detect the social meaning of gender; however, this sensitivity is very slight.

Figure 4.

Mean judgement scores for discourse markers by self-report identification. Judgement scores ranged from 1—male (M) to 5—female (F).

6. Discussion

In two experiments, we investigated how individuals’ positioning to a variable mediates the awareness of social meaning by examining perceptions of gender and life-stage in yeah-no users and non-users in Australian English. We found that, at least for this paradigm, the positioning of an individual towards a linguistic variable influences their awareness of the variable’s social meanings. In Experiment A, the discourse marker yeah-no in Australian English was judged as more likely to be uttered by a student than an employee, especially among those who did not self-report as yeah-no users. This finding aligns with previous studies on yeah-no (Burridge and Florey 2002; Moore 2007), albeit with a deviation in the age effect, which was more pronounced for the 35–49 age range in Burridge and Florey. Experiment B, interestingly, revealed no overall effect of form, contrary to Moore’s (2007) observation of a higher frequency of variable use among males. Notably, participants who self-reported as non-yeah-no users exhibited a significant form effect, perceiving yeah-no sentences as more likely to be spoken by a male. It is important to consider here the sample demographics when interpreting the results of Experiment B. Our sample included a higher proportion of young participants (18–25 years old) compared to older participants. This age distribution may have influenced the findings, as younger individuals might have different linguistic perceptions and usage patterns compared to older individuals. This was not the case with Experiment A, however, though we recommend that future work using this framework includes a more balanced age distribution to avoid possible conflicts across the different age groups. Ultimately, the outcomes from both experiments in this study suggest that individuals’ positioning mediates the evaluation of social meaning.

Our discovery regarding the role of positioning contributes significantly to ongoing research that seeks to understand speakers’ motivations to use one linguistic variant over another. Context plays a significant role in individuals’ inability to deduce the social meaning expected to be indexed onto a variable. Stereotyping—both of groups of speakers and of variables themselves—also contributes to establishing a connection between individuals’ awareness of social meanings and their use, whether overt or covert, as tools for identity construction. Our study extends this line of inquiry, which investigates the attitudinal and cognitive factors that influence individuals’ awareness of social meaning by demonstrating that not only do an individual’s attitudes toward a speech community and normative stereotypes mediate judgments, but their positioning—how they position themselves through speech choices—also holds substantial significance. Those who self-report as speakers of a linguistic variable within a community appear less sensitive to the social meaning associated with that variable, while non-users exhibit heightened awareness of social meanings. This suggests that linguistic insecurity among non-users may contribute to their increased sensitivity to the social connotations of the linguistic variable. Thus, an individual’s positioning, akin to their beliefs and endorsement of stereotypes, emerges as a factor influencing cognitive processes in the evaluation of social meaning.

Examining the mismatches between the production of linguistic variables and evaluations of their potential social meaning(s), particularly when listeners are unaware of these correlating social meanings, raises questions about individuals’ positioning. For instance, if the listeners in these previous studies on (ING) self-reported as users of the alveolar form of the variable, they may not have been sensitive to the additional social meanings that were not perceived by listeners, such as the social categories of gender, socioeconomic status, dialect, age, and race that were also shown to correlate with (ING) in production (Fischer 1958; W. Labov 1966; Shopen 1978; Shuy et al. 1967; Trudgill 1974). On the other hand, if some listeners did show a sensitivity to the additional social meanings that were indexed onto the variable, they may not have been users of the alveolar form of the variable themselves. Ultimately, the ratio of those who show a sensitivity may be smaller than that of the listeners who do not have a heightened sensitivity, but the effect was unable to be identified without investigating individuals’ positioning to the variable. Approaching this line of reasoning from an alternative angle, it is also possible that speakers who self-report as users of a variable do not create associations between the linguistic variants and social categories of their community. That is, their variable use is natural and automatic, compared to explicitly learned, conscious language choices. Thus, users of a given variant may have implicit knowledge of speech patterns in their community but show no awareness as the relationship between the variant and its social categories is meaningless for the purpose of their communication.

An interesting point pertaining to the discourse marker yeah-no specifically is the overt nature of the variable in the community. The variable is marked, if not stereotyped, and the media attention surrounding the variable suggests it is salient in the speech community. Yeah-no’s status in the community as “speech junk” and a “verbal crutch” could be considered as negative, certainly a vernacular speech variant, and would thus be expected to impact individuals’ positioning. As discussed earlier, W. Labov’s (1966) study, whereby speakers from New York showed a tendency to report higher usage of standardized forms than their actual usage, differed significantly from Trudgill’s (1972) findings in the opposite direction which showed a tendency for speakers to report higher usage of non-standardized forms than their actual usage. Given the status of yeah-no, it appears that individuals are positioning in a similar way to the findings in Trudgill, suggesting that yeah-no has a non-standard social desirability bias. This possibility, however, will require further investigation, as the data used in this study are self-reported and thus cannot be directly compared to W. Labov or Trudgill’s work which investigates actual usage. Additionally, future work comparing variables that have standard or positive connotations compared to vernacular or negative connotations, in line with Trudgill’s distinction between overt and covert prestige, would be a very interesting line of further inquiry for understanding the role of positioning. Since we expect stronger reactions regarding positioning to a variable that has a marked status in the community compared to variables that are considered indicators in a speech community, a study comparing variables with different levels of social salience is highly encouraged to further unpack the investigation of positioning with respect to the awareness and control of social meaning.

Further to the association between yeah-no and its correlating social categories, we have found a production- and evaluation-based match between the stratification of yeah-no and the social category of age. For speakers who did not self-report as users of yeah-no, we also found a match between the stratification of yeah-no and the social category of gender. Both findings suggest that an association exists between the discourse marker and the social categories of age and gender, and this finding can be interpreted as the variable indexing the categories as social meanings. Given that age and gender are the only categories to have been investigated within a sociolinguistic framework on the discourse marker yeah-no, we encourage further investigation of the variable and other potentially relevant categories, especially since it has been demonstrated that variables can index multiple social categories. With respect to the Australian road safety campaign, which uses yeah-no as their punch line, the categories of region and socioeconomic status appear relevant, the latter having been previously noted by both Burridge and Florey (2002) and Moore (2007). These categories have also been discussed in research regarding Australian English, specifically, the divide between Australian English accents (Cox and Palethorpe 2010; Harrington et al. 1997; Mitchell and Delbridge 1965). We advocate for further examination into yeah-no in the hopes of improving our understanding of the current study’s results and, more broadly, our understanding of sociolinguistics in Australian English.

The final point we wish to raise here pertains to the incorporation of self-reports in sociolinguistic research. Researchers, quite rightly, cite the risks of using self-reports in linguistic research, as they do not reflect natural language in use. We do not contest this; however, we can confirm from the results of this study that when examining an individual’s awareness of social meaning, self-reports offer a unique insight into how individuals position themselves toward normative stereotypes. The results showed, through a combined method of evaluation tasks and self-reporting, that the positioning of the individual plays a role in the evaluation and awareness of social meaning. As such, our methodology builds upon research that has found that the association between linguistic variables and social categories can be mediated by both attitudinal and cognitive factors, such as the speaker’s normative endorsements and beliefs. In the future, a more robust examination of self-reports, especially those examined in combination with production-based research methods, would aid this line of research. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations into individuals’ positioning to a variable may offer finer-grained and subtler nuances that could reveal more about how we perceive social meaning and how we manipulate our speech for the purpose of communicating social meaning.

7. Conclusions

The results of this study show that the positioning of an individual towards a variable influences the individual’s awareness of the variable’s social meanings. In the two evaluation experiments, we found that individuals judged sentences including yeah-no as more likely to be said by a student, and this effect was stronger for individuals who did not self-report as yeah-no users. Furthermore, while there was no significant effect of gender, participants who did not self-report as yeah-no users were more likely to judge yeah-no sentences as said by a male speaker rather than a female speaker. The findings imply that the successful perception of social meaning depends on an individual’s positioning towards a variable. This suggests that individual beliefs encompass not only the endorsement of stereotypes but also the voluntary endorsement of the linguistic feature itself. These findings hold significant implications for the current trajectory of sociolinguistic research, indicating that awareness and control of social meaning are intertwined with attitudinal and cognitive factors related to individuals’ identities. Therefore, we strongly endorse the continuation of this line of research, proposing that the methodological techniques employed in the current study serve as a foundation for further investigations into the role of beliefs in social meaning awareness. Specifically, we advocate for a comprehensive approach that combines production, evaluation, and, notably, self-reports to unravel the intricacies surrounding the indexical nature of social meaning and the circular interplay with identity. This multifaceted methodology can provide valuable insights into the nuanced relationships between linguistic variables, social categories, and the beliefs that shape individuals’ perceptions of social meaning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and R.M.; methodology, S.S. and R.M.; software, S.S.; validation, S.S., R.M. and M.A.; formal analysis, S.S. and M.A.; investigation, S.S.; resources, S.S.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, R.M. and M.A.; project administration, S.S., R.M. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research, and the Western Sydney Research Code of Practice. It has been approved by Western Sydney University’s Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval number: H12163.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article may be found in the OSF repository at https://osf.io/q3xsr/?view_only=f8e9e52ea3204c9f9a93d481e02a64d6 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to two summer interns, Adam Anderson and Alicia Poletti, for their help in developing the stimuli and recruiting participants for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Experiment A (life-stage) stimuli.

Table A1.

Experiment A (life-stage) stimuli.

| Yeah-No Condition (Test Items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Code | Sentence | Type |

| yn-1 | Yeah no, it’s good | yeah-no |

| yn-2 | Yeah no, they’ll love it | yeah-no |

| yn-3 | Yeah no, it’s been fantastic | yeah-no |

| yn-4 | Yeah no, it was really hot | yeah-no |

| yn-5 | Yeah no, I think that could work | yeah-no |

| yn-6 | Yeah no, they’re right | yeah-no |

| yn-7 | Yeah no, there’s a lot happening this weekend | yeah-no |

| yn-8 | Yeah no, fair enough. | yeah-no |

| yn-9 | Yeah no, I’m interested | yeah-no |

| yn-10 | Yeah no, that’d be right up there with last week | yeah-no |

| yn-11 | Yeah, it’s good | yeah |

| yn-12 | Yeah, they’ll love it | yeah |

| yn-13 | Yeah, it’s been fantastic | yeah |

| yn-14 | Yeah, it was really hot | yeah |

| yn-15 | Yeah, I think that could work | yeah |

| yn-16 | Yeah, they’re right | yeah |

| yn-17 | Yeah, there’s a lot happening this weekend | yeah |

| yn-18 | Yeah, fair enough. | yeah |

| yn-19 | Yeah, I’m interested | yeah |

| yn-20 | Yeah, that’d be right up there with last week | yeah |

| Lexical Condition (Control Items) | ||

| Code | Sentence | Type |

| lex_control-1 | I have to go to class tomorrow | student |

| lex_control-2 | I was tired from doing my assignment | student |

| lex_control-3 | I am supposed to go on a school trip next week | student |

| lex_control-4 | I was called in by the principal earlier | student |

| lex_control-5 | I think the new teacher will be here soon | student |

| lex_control-6 | I like to go to lunch with my classmates | student |

| lex_control-7 | I don’t graduate until next year | student |

| lex_control-8 | I only had one subject to attend today | student |

| lex_control-9 | That guy was in my class last year | student |

| lex_control-10 | My grandparents come visit me once a month | student |

| lex_control-11 | I have to go to work tomorrow | employee |

| lex_control-12 | I was tired from doing overtime | employee |

| lex_control-13 | I am supposed to go on a business trip next week | employee |

| lex_control-14 | I was called in by the manager earlier | employee |

| lex_control-15 | I think the new boss will be here soon | employee |

| lex_control-16 | I like to go to lunch with my co-workers | employee |

| lex_control-17 | I don’t retire until next year | employee |

| lex_control-18 | I only had one meeting to attend today | employee |

| lex_control-19 | That guy was in my division last year | employee |

| lex_control-20 | My grandkids come visit me once a month | employee |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Experiment B (gender) stimuli.

Table A2.

Experiment B (gender) stimuli.

| Yeah-No Condition (Test Items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Code | Sentence | Type |

| yn-1 | Yeah no, it’s good | yeah-no |

| yn-2 | Yeah no, they’ll love it | yeah-no |

| yn-3 | Yeah no, it’s been fantastic | yeah-no |

| yn-4 | Yeah no, it was really hot | yeah-no |

| yn-5 | Yeah no, I think that could work | yeah-no |

| yn-6 | Yeah no, they’re right | yeah-no |

| yn-7 | Yeah no, there’s a lot happening this weekend | yeah-no |

| yn-8 | Yeah no, fair enough. | yeah-no |

| yn-9 | Yeah no, I’m interested | yeah-no |

| yn-10 | Yeah no, that’d be right up there with last week | yeah-no |

| yn-11 | Yeah, it’s good | yeah |

| yn-12 | Yeah, they’ll love it | yeah |

| yn-13 | Yeah, it’s been fantastic | yeah |

| yn-14 | Yeah, it was really hot | yeah |

| yn-15 | Yeah, I think that could work | yeah |

| yn-16 | Yeah, they’re right | yeah |

| yn-17 | Yeah, there’s a lot happening this weekend | yeah |

| yn-18 | Yeah, fair enough. | yeah |

| yn-19 | Yeah, I’m interested | yeah |

| yn-20 | Yeah, that’d be right up there with last week | yeah |

| Lexical Condition (Control Items) | ||

| Code | Sentence | Type |

| lex_control-1 | I went to the barber | male |

| lex_control-2 | I like soccer | male |

| lex_control-3 | I’m a stay at home dad | male |

| lex_control-4 | I left my necktie at home | male |

| lex_control-5 | The football tryouts went great today | male |

| lex_control-6 | I got a new pair of cufflinks for my birthday | male |

| lex_control-7 | I’ve had this briefcase since I started working here | male |

| lex_control-8 | I use a lot of cologne when I go out to dinner | male |

| lex_control-9 | I’m working as a waiter | male |

| lex_control-10 | I got a stain on my new vest | male |

| lex_control-11 | I went to the hairdresser | female |

| lex_control-12 | I like shopping | female |

| lex_control-13 | I’m a stay at home mum | female |

| lex_control-14 | I left my necklace at home | female |

| lex_control-15 | The netball tryouts went great today | female |

| lex_control-16 | I got a new pair of earrings for my birthday | female |

| lex_control-17 | I’ve had this handbag since I started working here | female |

| lex_control-18 | I use a lot of perfume when I go out to dinner | female |

| lex_control-19 | I’m working as a waitress | female |

| lex_control-20 | I got a stain on my new blouse | female |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Experiment A and Experiment B stimuli fillers.

Table A3.

Experiment A and Experiment B stimuli fillers.

| Fillers (Filler Items) | |

|---|---|

| Code | Sentence |

| mf-1 | The boys have had a good year |

| mf-2 | Where’s my bike? |

| mf-3 | I had a lot of fun on my holiday |

| mf-4 | This box is too heavy to lift |

| mf-5 | The bus is running late |

| mf-6 | I went out for dinner with my family for my birthday |

| mf-7 | I had lots of pets when I was a kid |

| mf-8 | My brother ended up getting grounded |

| mf-9 | I prefer swimming in the summer |

| mf-10 | I like to jog in the morning |

| mf-11 | My dogs are well-trained |

| mf-12 | I heard a lot of thunder last night |

| mf-13 | I going to pick up a parcel this afternoon |

| mf-14 | I think we should start work on our project right away |

| mf-15 | It was cloudy over my house this morning |

| mf-16 | My dad was caught in traffic today |

| mf-17 | I definitely prefer tea over coffee |

| mf-18 | I always oversleep |

| mf-19 | I had a big lunch today |

| mf-20 | That movie was pretty great |

| mf-21 | I still try to keep in touch with my friends |

| mf-22 | I like to make my bed in the mornings |

| mf-23 | I have to meet a friend at the library |

| mf-24 | I always get a chocolate milkshake after practice |

| mf-25 | My favourite meat is steak |

| mf-26 | I don’t drink much alcohol |

| mf-27 | I have a chisel but it’s blunt |

| mf-28 | I like watching comedies |

| mf-29 | I get a lot of headaches |

| mf-30 | I want to paint the lounge room a better colour |

| mf-31 | I’ll be going home for the weekend |

| mf-32 | I didn’t sleep well last night |

| mf-33 | I had bacon and eggs for breakfast |

| mf-34 | I’m saving money so that I can buy a new car |

| mf-35 | I know what I’ll do |

| mf-36 | I can’t read when it’s this noisy |

| mf-37 | The cheesecake was delicious |

| mf-38 | I’ll take you to the station |

| mf-39 | I’ll let you know if its cancelled |

| mf-40 | I just saw her at the bus stop |

| ff-1 | I’ll make the dessert |

| ff-2 | I think I look fat in this |

| ff-3 | I’ll have to start cooking dinner soon |

| ff-4 | Of course I can come to dinner |

| ff-5 | Actually, I’ve never been skiing |

| ff-6 | I know how to get there |

| ff-7 | I prefer aeroplanes because I can sleep easily |

| ff-8 | He said that Thursday is best for the meeting |

| ff-9 | I like the blue sweater the best |

| ff-10 | After that we just went home |

| ff-11 | I had a driving test on Thursday |

| ff-12 | My two cats like to sleep on my bed |

| ff-13 | My commute takes 45 min |

| ff-14 | My son likes basketball. |

| ff-15 | He was sick so we had a substitute teacher. |

| ff-16 | I can’t tell yet which restaurant I like better |

| ff-17 | Dinner is ready |

| ff-18 | I go to the gym every day |

| ff-19 | If you eat too much, you’ll get sick |

| ff-20 | The only thing I need to be happy is free time. |

| ff-21 | My grandmother knitted me a blanket for my birthday |

| ff-22 | I’ll use this one |

| ff-23 | I’ll leave in thirty minutes |

| ff-24 | They sometimes play baseball. |

| ff-25 | I don’t know what to do! |

| ff-26 | Long time no see! |

| ff-27 | You look tired. |

| ff-28 | See you later. |

| ff-29 | We should go to the park |

| ff-30 | I still can’t sleep |

| ff-31 | One should not listen to the opinions of bad friends. |

| ff-32 | I wonder what the population is |

| ff-33 | I feel stupid being forced in to buying expensive things like this |

| ff-34 | His new car is really something |

| ff-35 | She is my girlfriend |

| ff-36 | I’m going to the ballet |

| ff-37 | See you at lunch |

| ff-38 | Don’t worry |

| ff-39 | I’m full |

| ff-40 | This is a recent photo |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Experiment A and Experiment B self-report questions.

Table A4.

Experiment A and Experiment B self-report questions.

| Instruction | Which of These Options Would You Be Most Likely to Use to Reply to the Speaker? |

|---|---|

| Question 1 | “Do you like jogging?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, sometimes during the afternoon. |

| Response B | Yeah, sometimes during the afternoon. |

| Response C | No, sometimes during the afternoon. |

| Response D | Sometimes during the afternoon. |

| Question 2 | “I think we should begin our project right away”. |

| Response A | Yeah no, you’re totally right. |

| Response B | Yeah, you’re totally right. |

| Response C | No, you’re totally right. |

| Response D | You’re totally right. |

| Question 3 | “Do you drink much tea?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, I mostly drink coffee. |

| Response B | Yeah, I mostly drink coffee. |

| Response C | No, I mostly drink coffee. |

| Response D | I mostly drink coffee. |

| Question 4 | “That movie wasn’t very good”. |

| Response A | Yeah no, it was pretty awful. |

| Response B | Yeah, it was pretty awful. |

| Response C | No, it was pretty awful. |

| Response D | It was pretty awful. |

| Question 5 | “How did your tryouts go?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, I think I did pretty good. |

| Response B | Yeah, I think I did pretty good. |

| Response C | No, I think I did pretty good. |

| Response D | I think I did pretty good. |

| Question 6 | “Do you think you’re going to start training soon?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, I’ve been thinking about that for a while now. |

| Response B | Yeah, I’ve been thinking about that for a while now. |

| Response C | No, I’ve been thinking about that for a while now. |

| Response D | I’ve been thinking about that for a while now. |

| Question 7 | “Did you go in today?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, but only for a couple of hours. |

| Response B | Yeah, but only for a couple of hours. |

| Response C | No, but only for a couple of hours. |

| Response D | But only for a couple of hours. |

| Question 8 | “Do you see your friends often?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, they visit me every now and then. |

| Response B | Yeah, they visit me every now and then. |

| Response C | No, they visit me every now and then. |

| Response D | They visit me every now and then. |

| Question 9 | “That was fantastic!” |

| Response A | Yeah no, I was in pretty good form. |

| Response B | Yeah, I was in pretty good form. |

| Response C | No, I was in pretty good form. |

| Response D | I was in pretty good form. |

| Question 10 | “Have you tried the new pizza yet?” |

| Response A | Yeah no, I will next week. |

| Response B | Yeah, I will next week. |

| Response C | No, I will next week. |

| Response D | I will next week. |

References

- Agha, Asif. 2003. The Social Life of Cultural Value. Language & Communication 23: 231–73. [Google Scholar]

- Agha, Asif. 2007. Language and Social Relations. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-139-45928-7. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Gisle. 2001. Pragmatic Markers and Sociolinguistic Variation: A Relevance-Theoretic Approach to the Language of Adolescents. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-9814-9. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Wendy, David Eddington, and Lyndsey Nay. 2009. Dialect Identification: The Effects of Region of Origin and Amount of Experience. American Speech 84: 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Laurie, and Winifred Bauer. 2002. Adjective Boosters in the English of Young New Zealanders. Journal of English Linguistics 30: 244–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, John. 1979. Linguistic Style-Shifting in Black English. Ph.D. dissertation, United States University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Benor, Sarah. 2001. The Learned /t/: Phonological Variation in Orthodox Jewish English. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 7: 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Benor, Sarah. 2004. Talmid Chachams and Tsedeykeses: Language, Learnedness, and Masculinity among Orthodox Jews. Jewish Social Studies 11: 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britain, David. 1992. Linguistic Change in Intonation: The Use of High Rising Terminals in New Zealand English. Language Variation and Change 4: 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, Mary. 2001. The Whiteness of Nerds: Superstandard English and Racial Markedness. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11: 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2006. Social Stereotypes, Personality Traits and Regional Perception Displaced: Attitudes towards the ‘New’Quotatives in the UK 1. Journal of Sociolinguistics 10: 362–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, Kate, and Margaret Florey. 2002. “Yeah-No He’s a Good Kid”: A Discourse Analysis of Yeah-No in Australian English. Australian Journal of Linguistics 22: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2001. Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511612886. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, David. 2004. Too Much Speech-Junk? Yeah-No! Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/too-much-speech-junk-yeah-no-20040619-gdy2ga.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2005. Listener Perceptions of Sociolinguistic Variables: The Case of (ING). Stanford: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2007. Accent, (ING), and the Social Logic of Listener Perceptions. American Speech 82: 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2008. I’ll Be the Judge of That: Diversity in Social Perceptions of (ING). Language in Society 37: 637–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2009. The Nature of Sociolinguistic Perception. Language Variation and Change 21: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2011. The Sociolinguistic Variant as a Carrier of Social Meaning. Language Variation and Change 22: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J. K. 1992. Linguistic correlates of gender and sex. English Worldwide 13: 173–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J. K. 1995. Sociolinguistic Theory. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 9781405152464. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, Jenny. 1982. Variation in an English Dialect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521238021. [Google Scholar]

- Clopper, Cynthia G., and David B. Pisoni. 2004. Some Acoustic Cues for the Perceptual Categorization of American English Regional Dialects. Journal of Phonetics 32: 111–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clopper, Cynthia G., Susannah V. Levi, and David B. Pisoni. 2006. Perceptual Similarity of Regional Dialects of American English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 119: 566–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, Felicity, and Sallyanne Palethorpe. 2010. Broadness Variation in Australian English Speaking Females. Paper presented at the 2th Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology, Melbourne, Australia, December 14–16; Melbourne: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association (ASSTA), pp. 175–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, Jennifer S. 2011. The Effect of Borders on the Linguistic Production and Perception of Regional Identity in Louisville. Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey-O’Cain, Jennifer. 2000. The Sociolinguistic Distribution of and Attitudes toward Focuser like and Quotative Like. Journal of Sociolinguistics 4: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drager, Katie. 2005. Frombad to Bed: The Relationship between Perceived Age and Vowel Perception in New Zealand English. Te Reo 48: 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Eble, Connie. 1996. Slang and Sociability: In-Group Language among College Students. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 1-4696-1057-4. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 1988. Adolescent Social Structure and the Spread of Linguistic Change. Language in Society 17: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 1989. The Whole Woman: Sex and Gender Differences in Variation. Language Variation and Change 1: 245–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2005. Variation, Convention, and Social Meaning. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, Oakland, CA, USA, January 7. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2018. Meaning and Linguistic Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107559899. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope, and William Labov. 2017. Phonetics, Phonology and Social Meaning. Journal of Sociolinguistics 21: 467–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erman, Britt. 1997. ‘Guy’s Just Such a Dickhead’; the Context and Function of Just in Teenage Talk. In Ungdomsspråk i Norden. Edited by Ulla-Britt Kostsinas, Anna-Brita Stenström and Anna-Malin Karlsson. Stockholm: Sweden Institutionen för Nordiska Språk, pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Erman, Britt. 2001. Pragmatic Markers Revisited with a Focus on You Know in Adult and Adolescent Talk. Journal of Pragmatics 33: 1337–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, John L. 1958. Social Influences on the Choice of a Linguistic Variant. Word 14: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, Paul, and Gerard Docherty. 2006. The Social Life of Phonetics and Phonology. Journal of Phonetics 34: 409–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Robert. 2015. You’re Not from Around Here, Are You? In Prosody and Language in Contact. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 123–48. [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger, Stephen D. 1997. Words and Voices: Perception and Production in an Episodic Lexicon. In Talker Variability in Speech Processing. Edited by Keith Johnson and John W. Mullenix. London: Academic, pp. 33–66. [Google Scholar]