Abstract

Southern Min is generally known for not using classifiers [CL] for expressing definiteness/indefiniteness as it is associated with the bare classifier construction [CL N]. This paper offers evidence from Xiamen Southern Min (XSM) that the use of a specific classifier vs. the general classifier é contributes to referentiality in an alternative way by supporting object identification as it is due to the semantic specificity present in specific classifiers and absent in the general classifier. In a dialogic cognitive experiment adapted from the “Hidden color-chips” task (Enfield and Bohnemeyer 2001), 18 participants had to manipulate their addressees’ attention toward various objects situated in their immediate physical space through language as well as deictic gestures. The objects were associated with different specific classifiers or with the general classifier, and they were arranged according to the factors of (a) distance from speaker, (b) visibility for speaker, and (c) uniqueness (adjacency of similar items). The results show, among other things, that there is a higher tendency to use the specific CL in the [demonstrative CL N] construction if adjacent similar objects [−unique] are too far away from the speaker for clear identification by a demonstrative or a pointing gesture. This is seen as a last-resort strategy for creating contrast. Further corroboration comes from the use of specific classifiers in later mentions after the general CL failed to achieve clear identification. These findings can be situated in the broader context of other languages with classifiers in contrastive function (Thai, Vietnamese, and Ponapean) and they show the relevance of using dialogic texts for modeling classifier selection in contrast to narrative texts. Finally, dialogic contexts may serve as bridging contexts for grammaticalization from numeral classifiers to definiteness markers.

1. Introduction

In the long-standing research on numeral classifiers, it is widely acknowledged that the most common and fundamental functions of numeral classifiers are individuation and classification. The former means classifiers are used to make count nouns enumerable by individuating (Greenberg 1972) or atomizing (Chierchia 1998) them, while the latter refers to the fact that classifiers form a semantic system to classify nouns according to their semantic properties like animacy, shape, consistency, size, etc. (Aikhenvald 2000; Allan 1977; Denny 1976). As demonstrated in (1), in Mandarin Chinese, the classifier fēng ‘seal’ is used in the context of counting letters, given that letters used to be sealed at the time when that classifier was introduced.

| (1) | Mandarin [NUM CL N]: | |||

| a. | sān | fēng | xìn | |

| three | CL: sealed.item | letter | ||

| b. | *sān | xìn | ||

| three | letter | |||

| ‘three letters’ | ||||

It is also well-known that numeral classifiers can go beyond the functions of individuation and classification and obtain additional functions in many languages of East and mainland Southeast Asia (EMSEA). According to Bisang (1999, p. 115), “classification can be employed to compare one particular sensory perception and its properties to the properties of other sensory perceptions in order to identify that particular perception by subsuming it under a certain concept”. This operation is called identification, and identification forms the point of departure for CLs to take on the function of referentialization. Reference, according to Searle’s (1969) definition, is an act of identifying some entity that the speaker intends to talk about. The existing literature shows that numeral classifiers can contribute to the process of referentialization in various ways.

In studies of Sinitic, the referential function of CLs is typically concerned with the marking of (in)definiteness in the bare classifier construction [CL N], which comprises only the CLs and the head noun that follows (for a discussion of the referential functions of CLs in some non-Sinitic languages, cf. Section 4.3). The syntactic position and its semantic interpretation are language-specific, with considerable influence exerted by pragmatic factors and word order. For instance, in Mandarin Chinese (2a), the bare classifier construction [CL N] can exclusively occur in the postverbal position, where it only conveys indefinite interpretation. In contrast, in Wu (2b), the bare classifier construction can be employed on both sides of the verb, with the pre- and postverbal [CL N] exclusively conveying definite and indefinite interpretation, respectively. Cantonese (2c) further complicates the picture as the construction can manifest on both sides of the verb but with different interpretations: the preverbal [CL N] only denotes definiteness, while the postverbal [CL N] can be either definite or indefinite, depending on the context.

| (2) | Some Sinitic languages: [CL N] | |||||||

| a. | (*ge) | laoban | mai | le | liang | che. | (Mandarin) | |

| CL | boss | buy | PFV | CL: vehicle | car | |||

| ‘The boss bought a car.’ | ||||||||

| b. | kɣ | lɔpan | ma | lə | bu | tshotshɿ. | (Wu) | |

| CL | boss | buy | PFV | CL: vehicle | car | |||

| ‘The boss bought a car.’ | ||||||||

| c. | go | louban | maai | zo | ga | ce. | (Cantonese) | |

| CL | boss | buy | PFV | CL: vehicle | car | |||

| ‘The boss bought a/the car.’ | ||||||||

| (Li and Bisang 2012, p. 2) | ||||||||

Wang’s (2015) typology of CL systems based on an analysis of 120 Sinitic languages reveals the existence of seven possible types. These types are established with reference to the specific combination of syntactic position relative to the verb and the semantic interpretation of the bare classifier construction in terms of [±definite] (cf. Table 1). According to Wang’s categorization, Mandarin is a Type VII language, the Wu dialect of Fuyang aligns with Type IV, and Cantonese belongs to Type III.

Table 1.

Seven possible types of bare classifier configurations in Sinitic languages (Wang 2015, p. 115).

Remarkably, the majority of Min languages, including Xiamen Southern Min (XSM)1 as the focus of the present study, are classified as Type VI languages, which prohibit the use of a bare classifier construction, regardless of the position relative to the verb. These languages use [DEM CL N] and [‘one’ CL N] to denote definiteness (3a) and indefiniteness (3b), respectively. In both constructions, if the referent is identifiable from the context (e.g., through a clear pointing gesture or previous mentions), the DEM and the CL can both be omitted, i.e., a bare noun can be used. Like most Sinitic languages, XSM has a two-term demonstrative system with the proximal demonstrative zīt ‘this’ and the distal demonstrative hīt ‘that’, which generally identify items according to their distance from the speaker (Lien and Chiu 2014).

| (3) | Xiamen Southern Min: | ||||||||||

| a. | [DEM CL N] | ||||||||||

| *(hīt) | ziāh | ziăo-ă | bē | kì | lo. | ||||||

| DEM | CL: small.animal | bird-SUF | fly | go | PRT | ||||||

| ‘The bird flew away.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | [‘one’ CL N] | ||||||||||

| yī | gâng | gguă | gǒng | *(zít) | hâng | dâizì. | |||||

| 3SG | with | 1SG | tell | one | CL: matter | thing | |||||

| ‘He told me something.’ | |||||||||||

| (Wang 2015, p. 122)2 | |||||||||||

However, this does not mean that referentiality does not manifest itself in the use of CLs in XSM, because the selection of specific vs. general CLs also contributes to referentiality. Specific CLs are selected according to semantic properties of nouns and are limited to a specific and often small set of nouns, while general CLs can basically co-occur with any count noun and are the only possible CL for many nouns. In XSM, the general CL is é. It is often written with the Chinese character 個, even though its lexical source is still controversial (cf. Chappell 2018; Li 2007). An example of the substitution of a specific CL by the general CL is given in (4a) and (4b).

| (4) | Xiamen Southern Min: | |||

| a. | zít | kiā | cēhbāo | |

| one | CL: bag | schoolbag | ||

| b. | zít | é | cēhbāo | |

| one | CL: gen | schoolbag | ||

| ‘one schoolbag’ | ||||

| (Zhou et al. 2006, p. 236; glossed by us) | ||||

According to the fieldwork data of one of the authors, older speakers (over 69) of XSM are actually rather rigid in the assignment of specific CLs and do not allow the substitution of a specific CL by the general CL with some particular nouns. However, young speakers (under 30) of XSM tend to accept the substitution of a specific CL with the general CL, although this is not absolute. Since the data collected in this experiment show that all of the referents are mentioned with the general CL by many of the speakers, we believe that it is justified to claim that at least among young speakers of XSM, the substitution of a specific CL with the general CL is grammatical.

As for the conditions under which that substitution happens, there has been some research by Erbaugh (2002), Erbaugh and Yang (2006), and Erbaugh (2013), indicating that the selection between specific and general CLs is associated with information structure, syntactic function, and number. To be more specific, specific CLs are assumed to be used with the information focus in the postverbal object position, while higher numbers typically appear with the general CL.

While the association of the postverbal position with the information focus follows a universal tendency (Kiss 1998), Erbaugh’s (2002, 2013) generalization that specific CLs tend to be used at the first mention of an object may be due to the fact that her analysis is based on endophoric (text-internal) reference, as it is found in her narrative texts based on the Pear Story (Chafe 1980). Even if her results are statistically significant, it will be seen in our study that this is not replicated in the case of exophoric (text-external) reference, which is characteristic of dialogic texts. Since the exact use of specific CLs vs. the general CL in exophoric reference is largely unknown, this study will investigate the referential function of CLs in an exophoric context. Exophoric or dialogic contexts are generally characterized by the interaction of the speaker and hearer and, in the context of information structure, the assessment of the identifiability or accessibility of a concept in a concrete discourse situation (e.g., Lambrecht 1994). Thus, an utterance made by the speaker includes the hearer in the sense that the speaker tries to assess the degree to which a concept is referentially activated/accessible to the hearer. Given that dialogue is going on through time and is characterized by role change between the speaker and hearer (for a more detailed explanation, cf. Levinson 2016), the assessment of identifiability/accessibility requires permanent updates (cf. Section 3.3.1).

Based on these explanations, we summarize our research questions as follows:

- How are numeral classifiers in XSM associated with referentiality in exophoric contexts?

- What are the factors that impact the selection of the following options in exophoric situations?

- [DEM CL (N)] or [N];

- if [DEM CL (N)] is used, specific or general classifier

The factors that may affect the selection of the options given in question 2 in the experimental setting for identifying objects in space are as follows:

- (a)

- Distance: the distance of the referent from the speaker.

- (b)

- Visibility: the visibility of the referent from the speaker’s point of view, i.e., whether the speaker’s view of the referent is obstructed by another item, so the speaker cannot see the referent directly from where she/he is.

- (c)

- Uniqueness: the uniqueness of the referent within the speaker’s visual scope, i.e., is there only one object associated with the same noun [+unique] or is there more than one adjacent object of the same kind in the speaker’s scope [−unique]?

The choice of factors (a) distance and (b) visibility is based on Dixon’s (2003) major parameters of reference for demonstratives, as they are common categories encoded in forms which can have a deictic function. As this study will show, such forms include not only DEM, but also CLs. The choice of factor (c) uniqueness is based on the fact that unlike demonstratives, XSM CLs have additional functions of individuation and the marking of singular3. Given that CL use is obligatory with demonstratives, we believe that the different semantics of general vs. specific CLs may affect classifier selection depending on [±uniqueness].

Moreover, to understand to what extent the presence of DEM would influence the result of our investigation on CLs, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis of the potential influence of distance, visibility, and uniqueness on the distribution of the proximal and distal DEM (see Section 3.1 for more information on this type of test). The results show that DEM is sensitive to distance (p < 0.001) in XSM, but to neither visibility (p = 0.659) nor uniqueness (p = 0.469), which further corroborates Lien and Chiu’s (2014) observation.

The present study is based on a cognitive experimental approach and involves both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The results will provide significant evidence for the higher probability to use the [DEM CL N] construction if the referent to be identified is visible. As for the probability to use a specific or general CL, it is associated with distance and uniqueness in an intertwining way.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the research method used for the experiment and is followed by the results and the analysis in Section 3. The discussion is found in Section 4. It presents the cognitive motivations for using the [DEM CL N] construction and the use of a specific CL vs. the general CL in contexts of contrastive focus. In addition, it discusses three other languages in which CLs are used in contrastive contexts (Thai, Vietnamese, and Ponapean). Section 5 will conclude this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

The cognitive experiment used in this study is an adapted version of the “Hidden color-chips” task created by Enfield and Bohnemeyer (2001). Their experiment in the form of a memory test was designed to investigate the use of demonstratives in the exophoric context. It is described as follows by the authors:

“This task is designed to create a situation in which the speaker is genuinely manipulating the addressee’s attention on objects in the immediate physical space in order to solve the task, and without being asked to introspect about which demonstrative they ‘would use’ in the situation.”(p. 21)

We redesigned the experiment by using the factors of distance, visibility, and uniqueness for detecting factors that may affect the selection of the relevant constructions (research question 2a) and the choice between a specific CL and the general CL (research question 2b).

2.1. Participants

The participants are 18 native speakers of XSM, including 9 females and 9 males. All are below the age of 30 and without immigration backgrounds. XSM is one of their family languages, if not the only one. In the questionnaire that the participants filled out before recruitment, they all evaluated their proficiency in XSM as high or relatively high. The participants joined the experiment in pairs, and the study tried to ensure that most participants within each pair were familiar with each other. This facilitated a more natural mode of communication.

2.2. Procedure

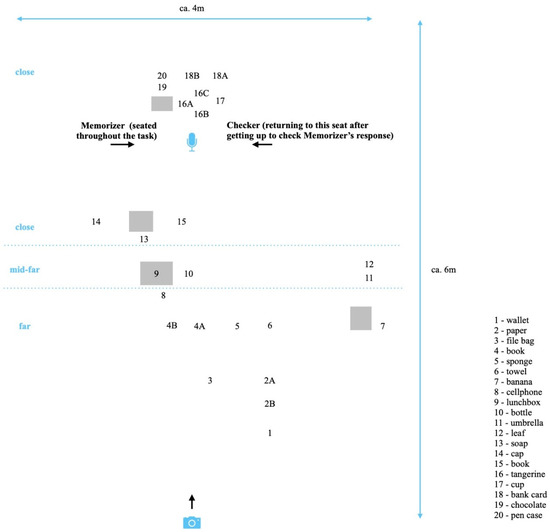

A total of 20 target objects were strategically placed in a room among other irrelevant objects. The nouns denoting the items used in the experiment were anticipated to take different CLs, including specific and general ones. In the arrangement of the items, distinctions were made between different levels of distance (close, mid-far, and far), visibility [±visible], and uniqueness [±uniqueness], as illustrated in Figure 1 (for further details, cf. Section 2.3 and Appendix A). Under each target object were hidden small colored chips in one of the following four colors: red, yellow, blue, or green.

Figure 1.

The setting of the “Hidden color-chips” experiment. Each number is an object, as indicated by the legend on the right. Similar items of the same kind (therefore also with the same CL) are marked with different letters (“A”, “B”, and “C”), among which only “A” is the target object with a colored chip underneath. Gray blocks refer to items that obstruct M’s view of the item behind it. For instance, M’s view of item 8 (cellphone) is obstructed by item 9 (lunch box), so M cannot see item 8 directly from their seat. Therefore, item 8 has [−visible] in the experimental setting. All of the items are placed on platforms and the asymmetric configuration of the items was carried out with the consideration of facilitating easy movement of C.

The experiment was based on the cooperation of two participants, one of them appointed as “memorizer (M in the following mentions)” and the other one as “checker (C in the following mentions)”. M was first brought into the room and was shown where 10 of the colored chips were hidden. M’s task was to memorize the location and the color of the 10 chips. After M finished memorizing this information, C was brought into the room and sat opposite to M. C’s task was to check M’s memory by asking, e.g., ‘Under what objects are there red/yellow/blue/green chips?’ for one color after another (the reason for using this pattern of questioning is explained in Section 2.3). Following each response from M, C was required to pick up the item referred to and to validate the correctness of the answer. Follow-up dialogic exchanges were not only permitted but even encouraged. After all of the 10 target objects were pointed out by M and checked by C, the first round of the experiment was concluded. After that, the two participants were asked to switch roles, i.e., the participant who was M in the first round was designated as C, while C in the first round transitioned into the role of M. In the second round, they used the other 10 target objects in the room with colored chips underneath them to repeat the task.

The aim of the experiment was to check if the demonstrative construction [DEM CL N] was used, and if so, whether the speakers used a specific CL or the general CL. The limitation to 10 items in each round was the result of adjustments made through pilot studies, which showed that having more than 10 target objects in a test was beyond the memorizing capacity of average speakers. This was also the reason for the relatively small set of objects used in “mid-far”.

2.3. Experimental Set-Up: The Variables

The experiment was conducted to observe the impact of the independent variables of distance (close/mid-far/far), visibility (visible/invisible), and uniqueness (unique/non-unique) on the use of CLs. We selected three levels for distance because it is more gradable than visibility and uniqueness, and because we did not want to take for granted that the selection of a specific CL vs. the general CL followed the binary deictic distinction of proximal vs. distal demonstratives in Sinitic. Additionally, to investigate the potential influence of expected CL types on the decision of whether to use the DEM construction, a distinction between expected CL types was made in the experimental setting (see Appendix A for a list of the items used in the experiment and the variables that their arrangements are associated with). The expected CLs were confirmed by native speakers during the preparation of the experimental setting.

The dependent variables of the experiment, i.e., the variables to be observed in the results, are speakers’ selection (a) between [DEM CL (N)] and [N] and (b) between the general CL é and a specific CL if a DEM construction is used.

The control variables kept consistent throughout the experiment are the factors influencing the distribution of specific and general CLs (Erbaugh 2002, 2013; Erbaugh and Yang 2006), i.e., information structure, grammatical relation, and number. These factors are controlled by having C consistently asking questions of this specific pattern:

| (5) | sîmbbníh | bbníhgniâ | êduě | wû | ángsīk | e | gí-ǎ? |

| Q | thing | bottom | have | red | MOD | piece-DIM | |

| ‘Under what objects are there red “pieces (chips)”?’ | |||||||

As in Sinitic languages, interrogative pronouns take the same syntactic position as the corresponding answers, the answers from M would always fall into the slot of the informational focus/subject (sîmbbníh bbníhgniâ ‘what thing’) of the given question. In the quantitative analysis, only M’s first-mentioned nouns are counted, which assures that they only involve new information. Moreover, since all of the referents in the experiment are singular, there is no occurrence of higher numerals. In this quantitative part of the analysis, M’s responses are analyzed through different tests with the software application SPSS (Version 27), and the significance threshold is set to p ≤ 0.05. Moreover, this study also involves a qualitative analysis, where all of the utterances of both participants in the experiments are carefully observed. The experiments were filmed with the speakers’ consent, allowing for the observation of gestures in the process. Table 2 is a summary of the variables in this study.

Table 2.

Independent, dependent, and control variables of this study.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. General Results

In an ideal situation, the experiment should collect 180 noun phrases denoting the referents from M (18 memorizers × 10 items), but due to forgetting and occasional use of the existential construction, which are excluded in the quantitative analysis, the experiment obtained 167 tokens of noun phrases. The frequency of different constructions is demonstrated in Table 3. The [DEM CL (N)] construction is exemplified in (6) and (7), and the bare noun construction in (8). Note that XSM does not allow for the strategy of using the general CL in an extra CL position, as is the case in Vietnamese (cf. Section 4.3.2).

| (6) | [DEM CL N] | |||

| hīt | gī | hoôsnuà. | (Speaker 1) | |

| that | CL: stick-like.item | umbrella | ||

| ‘That umbrella.’ | ||||

Table 3.

The frequency of different constructions used by the memorizers in the first-mentioned noun phrases in their responses.

| (7) | [DEM CL] | ||||||

| zīt | é. | zīt | é. | zīt | bnī. | (Speaker 3) | |

| this | CL: gen | this | CL: gen | this | side | ||

| ‘This. This. This side.’ | |||||||

| (8) | [N] | |||

| zníbāo | êkā | (Speaker 3) | ||

| wallet | under | |||

| ‘Under the wallet.’ | ||||

The head noun is occasionally omitted (7), albeit infrequently. The infrequency is plausible because the noun phrases are mentioned for the first time. Moreover, in one token, the locative demonstrative pronoun ziá ‘here’ is used. A total of 38 nouns were mentioned without a DEM or a CL, but the nouns sometimes occurred with attributes. Moreover, all speakers used either finger gestures or gaze to point at all of their referents.

A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to reveal potential correlations between the independent variables and the dichotomous dependent variables. The regression analysis of the distribution of specific and general CLs was limited to tokens involving nouns anticipated to co-occur with a specific CL (n = 126). Table 4 provides an overview of the results, which will be introduced with more detail in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

Table 4.

The possibility of correlation (p-value) according to the result of the binary logistic regression (bold: statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05)).

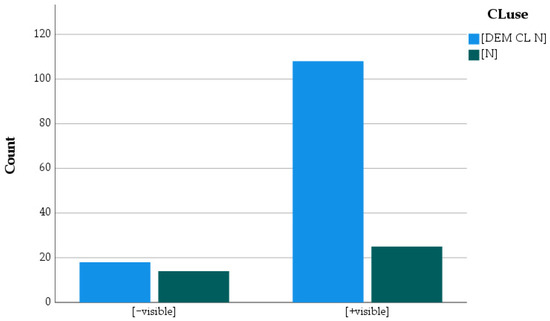

3.2. When Are the Demonstrative Constructions More Likely to Be Used?

As shown in Table 4, the selection between the [DEM CL (N)] construction and the bare noun is significantly associated with visibility (p = 0.030), while distance and uniqueness do not exert a significant influence on this selection. Moreover, the expected CL type does not have any impact on the presence/absence of the DEM construction. Additionally, a Chi-square test of independence further confirms that the use of the [DEM CL (N)] construction differs significantly between different levels of visibility (χ2 (1, 166) = 9.771, p = 0.002), in that the [DEM CL (N)] construction is much more likely to be used if the referent is [+visible] than if it is [−visible], as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of [DEM CL (N)] and [N] according to [±visible].

3.3. When Are Specific/General Classifiers Preferred in the Demonstrative Construction?

While the binary logistic regression analysis did not reveal statistically significant correlations between the selection of specific/general CLs and any of the independent variables, the qualitative analysis (cf. Section 3.3.1) uncovered certain subtle associations between them. This is corroborated later by a quantitative analysis (cf. Section 3.3.2).

3.3.1. Qualitative Analysis

In our qualitative analysis, we included not only the first-mentioned noun phrases, but also the ones mentioned later. It is remarkable that if M used the general CL é in their first (and sometimes in their first two) responses in the context of [−unique], they tended to later repeat their instructions with a specific CL when their previous answers did not have the desired effect, i.e., when M assumed that C felt unsure about the object to be identified as in (9) and (10), or when C was on the verge of selecting a wrong item as in (11). In other words, specific CLs were frequently used in later mentions for further specification. In our study, we found 36 cases with [−unique], out of which 20 responses were repeated. Among these, the nouns were first mentioned with the general CL é in 11 cases, and later, there was a switch from general to specific CL in 8 of them. These tokens were collected from seven different participants. We take this as an indicator of the pervasiveness of such a shift.

| (9) | hīt | é | zuǎ, | táodǐng | hīt | é. | (Speaker 6) | ||

| that | CL: gen | paper | upper | that | CL: gen | ||||

| (C approached the correct paper and asked for confirmation) | |||||||||

| ǹg, | hīt | dniū | zuǎ. | ||||||

| um | that | CL: two.dimensional | paper | ||||||

| ‘That paper… the upper one…’ ‘Um… that paper.’ | |||||||||

| (10) | zīt | é | ggúnhángkǎ… | kò | gguǎ | zīt | bnī | e | |||||||||||

| this | CL: gen | bankcard | close.to | I | this | side | MOD | ||||||||||||

| hīt | é. | (Speaker 13) | |||||||||||||||||

| that | CL: gen | ||||||||||||||||||

| (C couldn’t identify the referent) | |||||||||||||||||||

| kò | gguǎ | zīt | bnī | e | hīt | é, | hīt | ||||||||||||

| close.to | I | this | side | MOD | that | CL: gen | that | ||||||||||||

| dniū. | |||||||||||||||||||

| CL: two.dimension | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘This bank card… The one close to my side.’ ‘That one close to my side, that one.’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| (11) | zīt | é | ggúnhángkǎ. | (Speaker 15) | |||

| this | CL: gen | bankcard | |||||

| (C approached the wrong card) | |||||||

| ěi, | bbó, | zītdniū. | |||||

| eh | NEG | this | CL: two.dimensional | ||||

| ‘This bank card.’ ‘Eh, no, this one.’ | |||||||

Moreover, in the majority of instances where C asked for additional clarification following M’s response with a general CL, a specific CL was employed in C’s subsequent question. This is illustrated by the following two examples:

| (12) | M: | “oò, | oò, | zīt | é, | zīt | é, | zīt | é, | ||||||

| oh | oh | this | CL: gen | this | CL: gen | this | CL: gen | ||||||||

| ciáng, | ciáng, | ciáng.” | (Speaker 4) | ||||||||||||

| tangerine | tangerine | tangerine | |||||||||||||

| ‘Oh, oh, this one, this one, this one, tangerine, tangerine, tangerine.’ | |||||||||||||||

| C: | “dǒ | zít | liáp?” | ||||||||||||

| which | one | CL: round.item | |||||||||||||

| ‘Which one?’ | |||||||||||||||

| M: | “zīt | liáp.” | |||||||||||||

| this | CL: round.item | ||||||||||||||

| ‘This one.’ | |||||||||||||||

| (13) | M: | “āhgōh | zīt | é, | zīt | é | ciáng, | zīt | |||||||||||||||||||||

| and | this | CL: gen | this | CL: gen | tangerine | this | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| é | ciáng | êkā.” | (Speaker 12) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CL: gen | tangerine | under | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘And this one, this tangerine, under this tangerine.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C: | “ciáng | wû | snā | liáp, | dǒ | zít | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| tangerine | there.are | three | CL: round.item | which | one | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| liáp?” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CL: round.item | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘There are three tangerines. Which one?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M: | “ziû | sî | kògûn | lǐ | e | zīt | liáp.” | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| just | COP | be.close.to | you | MOD | this | CL: round.item | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘It is just the one close to you.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This phenomenon is very remarkable because specific CLs do not seem to contribute any semantic clues in contexts of [−unique] that could help C to further narrow down the range of potentially relevant objects. Seen in the light of role change between the speaker and hearer in dialogic exchange (cf. Section 1), one may account for this effect based on the realization of M that C cannot identify the relevant object in (9)–(11), or, in the case of (12) and (13), based on C trying to express their wish for a more specific instruction on which was the intended object and later M trying to specify it more clearly. Given that the grammatically available inventory for identification is exhausted in this situation, an unconventional solution is selected by using the specific CL which, in many situations (but not this one), contributes to the identifiability of an object. Of course, speakers are generally able to just add additional lexical information if needed. But this does not happen in the dialogues in (9) to (13). We take this as an indicator that speakers have a certain “confidence” in the distinctive potential associated with specific CLs and that they try it as a last resort when any other grammatical option fails (also cf. Section 4.2 for additional explanations), which actually looks like a “futile effort”. According to the evidence provided by this study, the motivation of M’s use of a specific CL in later mentions is pragmatic, which will be further discussed in Section 4.2.

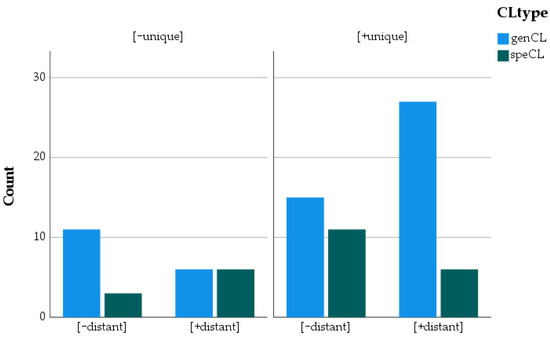

3.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

According to Table 4, in instances where the nouns can co-occur with a specific CL, there is no statistically significant correlation between the variables of distance, visibility, and uniqueness and the selection between a specific CL and the general CL. However, some subtle correlations manifest themselves when stratification is incorporated into the analysis.

To facilitate the stratified Chi-square test of independence with SPSS, which necessitates binary variables, the categories “mid-far” and “far” were conflated into a category labeled as [+distant], contrasting with [−distant] for near referents. This rearrangement was based on the fact that the use ratio of the distal demonstrative in cases with “mid-far” (83.3%) was similar to that in cases with “far” (93.8%), while it was much lower in cases with “close” (24.1%). This indicates that speakers perceive both “mid-far” and “far” in the experimental setting as contrasting to “close”, which further confirms the two-way demonstrative system of XSM.

The results of the stratified Chi-square test of independence show that [±distant] and [±unique] are associated with classifier choice in an intricately intertwined manner.

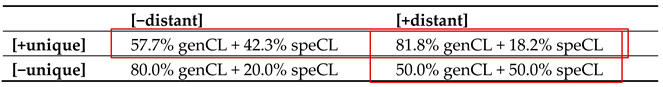

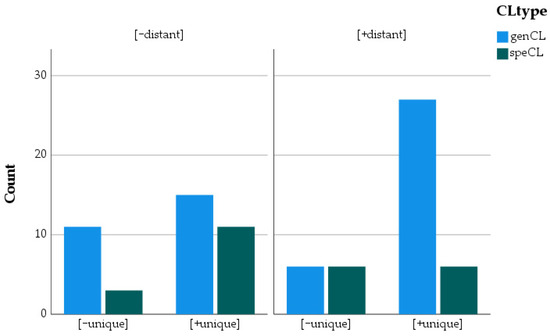

- The stratified Chi-square test of independence also reveals that the CL choice in [±distant] significantly differs between [+unique] and [−unique] (χ2 (1, 86) = 6.367, p = 0.012), and only in the case of [+unique] does the CL choice significantly differ between [+distant] and [−distant] (χ2 (1, 59) = 4.127, p = 0.042). As demonstrated in Figure 3, if the referent is [+unique], speakers are more likely to use a specific CL for the referents with [−distant] over those with [+distant], while they prefer a general CL for the referents with [+distant] over those with [−distant]. If the referent is [−unique], there is no substantial difference in the distribution of specific and general CLs in the contrast between [±distant] (χ2 (1, 27) = 2.700, p = 0.100).

Figure 3. Distribution of specific and general CLs according to [±distant], controlling for [±unique].

Figure 3. Distribution of specific and general CLs according to [±distant], controlling for [±unique]. - The CL choice according to [±unique] significantly differs between [+distant] and [−distant] (χ2 (1, 86) = 6.391, p = 0.011). Only in cases with [+distant] does the classifier choice significantly contrasts between [+unique] and [−unique] (χ2 (1, 45) = 4.556, p = 0.033): speakers are more likely to use the general CL for the referents with [+unique] and a specific CL for those with [−unique], as demonstrated in Figure 4. No notable difference is found in the distribution of specific and general CLs in the contrast between [±unique] (χ2 (1, 41) = 2.105, p = 0.147).

Figure 4. Distribution of specific and general CLs according to [±unique], controlling for [±distant].

Figure 4. Distribution of specific and general CLs according to [±unique], controlling for [±distant]. - A test of homogeneity of the odds ratio was also performed to assess the relationship between [±visible], [±distant], and CL choice. The result shows no remarkable correlation, regardless of whether [±visible] is on the higher layer (χ2 (1, 86) = 1.677, p = 0.195) or on the lower one (χ2 (1, 86) = 1.643, p = 0.200).

3.4. Summary

The main effects shown in the quantitative and qualitative analysis can be summarized in four points. Their motivations will be tentatively discussed in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2.

- Compared with a bare noun, the DEM construction is clearly more likely to be used when the object has [+visible], i.e., the speaker’s view of the object is not blocked by anything.

- In cases with [+unique], speakers are significantly more likely to use a specific CL for objects with [−distant] compared to those with [+distant].

- In cases with [+distant], speakers are significantly more likely to use a specific CL if the referents have [−unique], and a general CL if they have [+unique].

- The qualitative analysis shows that in cases with [−unique], if the [DEM CL (N)] construction uses the general CL é in the first-mentioned noun phrase but fails to identify the relevant object, speakers frequently switch to a specific CL when they repeat the noun phrase.

The percentage of classifier types according to different levels of [±distant] and [±unique] in first-mentioned noun phrases are illustrated in Table 5, with statistically significant contrasts framed in red.

Table 5.

Distribution of specific and general CLs according to [±distant] and [±unique] in first-mentioned noun phrases.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect I and II: Cognitively More Accessible Items Tend to Be Further Specified

Effect I and II arguably reveal that clearly visible and near referents are cognitively more accessible and thus easier and more likely to be further specified. The two effects are discussed below.

The correlation between visibility and the use of the DEM construction as shown in Effect I is not surprising, since the two-term demonstrative system in Southern Min is known for making a distinction in distance, and it is plausible that speakers are more likely to use a DEM only in situations where they can clearly see the objects and easily identify the distance.

Moreover, the higher probability of using a specific CL for a unique and near referent can be explained by a similar motivation: since specific CLs have a classification function, if an item that is usually counted with a specific CL is close to the speaker, it is cognitively easier for the speaker to recognize the item’s properties and thus decide on the specific CL that is associated with the specific property. Otherwise, the specific CL would be cognitively less accessible, which thus makes speakers more inclined to use the general CL é. This observation agrees with Erbaugh’s (1986) claim about CLs in Mandarin Chinese that specific CLs are more likely to be used for near reference. It is also in line with Vittrant and Allassonnière-Tang’s (2021) observation that specific CLs tend to be used when the object is prominent in discourse, because near objects are generally more prominent than far-away objects, all other things being equal.

4.2. Effect III and IV: Contrastive Function of Xiamen Southern Min Specific Classifiers

According to Effect III that specific CLs are more likely to be used in contexts with [−unique] and [+distant], we suggest that specific CLs have a contrastive function in this specific context, and this is motivated by the problem that the distal DEM and the speakers’ pointing gestures are not distinctive enough to clearly identify the referent within a group of far-away referents. In the experimental situation, contrast can in principle be expressed by a DEM, a gesture, and modifiers. Since modifiers are not used in the majority of first mentions in this study, even in situations with [−unique] (7 out of 32 tokens with [−unique] use a modifier), we will not discuss them in this paper. If the objects were different in terms of distance or both had [−distant], the speakers’ gestures and the selection between the proximal vs. the distal DEM would both be effective tools that help the hearer with identification. As illustrated in (14), the referent has [−distant], [−unique], and [+visible]. In the speaker’s (M) first reaction, only a bare noun and a gaze were used, but then from the hearer’s reaction, M quickly realized that the first instruction was not clear enough for C to identify the exact referent. In order to solve the task, M gave a second instruction, but this time making use of a distal demonstrative and a modifier to indicate that the referent is the one closer to C (and further away from themself), and these tools are effective in this case.

| (14) | ciáng | êkā… | kògûn | lĭ | e | hīt | liáp | |

| tangerine | under | be.close.to | you | MOD | that | CL: round.item | ||

| ciáng. | (Speaker 10) | |||||||

| tangerine | ||||||||

| ‘(It’s) under the tangerine… the tangerine close to you.’ | ||||||||

However, in the cases where the object is further away, speakers can only use the distal DEM hīt, which is not a sufficient tool for identifying the relevant object anymore if the referent is among a couple of similar items. This means that both strategies generally available (DEM and gesture) are weakened in such a situation and speakers thus need to seek an alternative strategy for conveying contrast within the [DEM CL (N)] construction. Thus, using a specific CL becomes a “last resort” in this case (cf. Section 3.3.1). While the bleached semantics of the general CL é prevents it from obtaining deictic referential functions, the more specific semantics of specific CLs enables them to take on the function of marking contrastive focus in the sense of selecting the relevant object out of a presupposed set of objects (Chafe 1976), which is defined in the experiment by spatial adjacency. From the point of view of grammaticalization, this would be the exact bridging context (Heine’s (2018) Context Model of Grammaticalization and Traugott and Dasher’s (2002) Invited Inference Theory of Semantic Change) where a contrastive inference of specific CLs occurs.

This hypothesis is further corroborated by the observation of Effect IV. In cases of [−unique], if the first mention with the general CL fails to identify the referent, switching to a specific CL in later mentions is for identifying the relevant object by marking contrast. As a result, the specific object is highlighted in discourse, which leads C to take a closer look at M’s gesture or pick up one of the other similar item(s) (depending on the situational context).

With these results, Effect IV partially contradicts Erbaugh’s (2013) findings that specific CLs tend to be used with first-mentioned nouns and then “downgrade” to the general one in later mentions in Sinitic languages (except for Cantonese). The reason for this contradiction would be the difference in the genre of our research materials: deictic referentiality is much more likely to be attested in exophoric contexts than in endophoric ones. Considering the dialogic situation as highlighted in Section 3.3.1, using a specific CL in later mentions can also be due to permanent updating on the current speaker’s assessment of the identifiability of a concept in the hearer’s mind. More generally, this difference in our findings also points out the importance of using various types of speech materials in linguistic research or using those that fit best with one’s specific research question.

Notably, the DEM construction is not the only environment where XSM specific CLs are used for contrastive purposes. A similar pragmatic function is attested in the [ADJ CL N] construction, as demonstrated in (15), which is taken from an instruction regarding ingredients needed for making rice dumplings.

| (15) | Xiamen Southern Min [ADJ CL N]: | |||||||||||

| a. | duâ | ziāh | hébbì, | ̂m | sî | suè | ziāh | |||||

| big | CL: animal | dried.shrimp | NEG | COP | small | CL: animal | ||||||

| hébbì. | ||||||||||||

| dried.shrimp | ||||||||||||

| b. | *duâ | é | hébbì, | ̂m | sî | suè | é | |||||

| big | CL: gen | dried.shrimp | NEG | COP | small | CL: gen | ||||||

| hébbì. | ||||||||||||

| dried.shrimp | ||||||||||||

| ‘(You will need) big dried shrimps, not small ones.’ | ||||||||||||

| (fieldwork data) | ||||||||||||

As shown in (15b), substituting the specific CL ziāh with the general CL é is ungrammatical in this context. Interestingly, adjectives that are allowed to occur with specific CLs in the attributive adjective construction are limited to duâ ‘big’ and suè ‘small’. The reason for this still requires further investigation.

4.3. Contrastive Function of Numeral Classifiers from a Typological Aspect

Contrastive use of CLs is not cross-linguistically common, but it is not unique to XSM either. It is attested in some other languages. This section will illustrate the contrastive function of CLs in Thai (Tai-Kadai), Vietnamese (Austroasiatic), and Ponapean (Austronesian) and discuss differences and similarities to specific CLs in XSM.

4.3.1. Thai

In Thai, with adjectives (ADJ), CLs can express definiteness and specificity. In addition, they can also be used in situations of contrastive focus (Hundius and Kölver 1983, pp. 176–77; Bisang 1999). Thus, the CL in (16) is employed to correct a previously mentioned wrong assumption about the size of the car that the speaker likes:

| (16) | Thai [N CL ADJ] | ||||||||

| chɔ̂ɔp | rót | khan | lék | mâj | chɔ̂ɔp | rót | khan | ||

| like | car | CL: vehicle | small | NEG | like | car | CL: vehicle | ||

| jàj. | |||||||||

| big | |||||||||

| ‘I like the small car. I do not like the big car.’ | |||||||||

| (Bisang 2008, p. 23) | |||||||||

However, although both XSM and Thai CLs can be used to express contrastive focus with ADJ, there are two notable differences:

First, Thai has very strict lexical rules that assign a CL to a given noun, so it does not have a general CL that can substitute specific CLs, and all Thai CLs can be used for contrastive purposes. In contrast, the boundaries between different noun classes are not absolutely strict in XSM, as one can see from the existence of the general é in XSM, since the CL é is semantically too general to be able to subsume a certain item under a certain concept, as would be needed to identifying it in terms of reference.

Second, Thai CLs only mark contrast in later mentions after a wrong statement is made or implied by context. However, in XSM, specific CLs are used in both first-mentioned and later-mentioned noun phrases to mark contrast, with the latter being more frequent. In other words, Thai CLs can only make already definite or specific nouns contrastive, which is also the case for XSM specific CLs in the DEM construction. However, XSM specific CLs in the ADJ construction do not need to be definite/specific. As exemplified in (15a), the construction can also be generic.

4.3.2. Vietnamese

Classifier use for contrastive purposes is also observed in Vietnamese, but it is only expressed by the general CL cái, which usually occurs with non-living things (Löbel 2011). Cái in its contrastive function bears phonological stress and takes a different syntactic slot from the one taken by CLs, as illustrated in (17). For that reason, cái in its contrastive function is also called “extra CÁI” in the literature.

| (17) | (Num)—CÁI—CL—N—modifier |

The use of “extra CÁI” is illustrated in (18). (18a) is a simple statement with no contrast, while in (18b), “extra CÁI” is used to stress the contrast between “this very book” and any other books that may be potential referents in the discourse situation.

| (18) | Vietnamese: | ||||||||

| a. | [CL N DEM] | ||||||||

| cuốn | sách | này | hay | thật. | |||||

| CL: book | book | this | good | real | |||||

| ‘This book is really good.’ | |||||||||

| b. | [CÁI CL N DEM] | ||||||||

| CÁI | cuốn | sách | này | hay | thật. | ||||

| CÁI | CL: book | book | this | good | real | ||||

| ‘This very book is really good.’ | |||||||||

| (Nguyen 2004, p. 45) | |||||||||

The use of the Vietnamese general CL cái as a contrastive marker indicates that if a classifier language develops a contrastive function in its classifier system, it is not necessarily the specific CLs which will take up that function because of their more specific semantics. Here, the grammaticalization of the CL comes with an extra syntactic position.

4.3.3. Ponapean

Contrast can be marked by CLs in combination with DEMs in Ponapean, an Austronesian language spoken on the Pohnpei island in the Pacific Ocean. According to Rehg (1981), a CL is obligatory in the [N Num-CL] construction in the context of counting, but it is not obligatory in the DEM construction. Ponapean has a DEM system that distinguishes emphatic and non-emphatic DEM determiners. An emphatic DEM is formed in the singular by combining a CL (e.g., men- for animate nouns, as shown in Table 5) with the non-emphatic form of the singular demonstrative. In the case of plural, the non-emphatic plural demonstrative takes the affix pwu-, which does not have a classification function. The paradigm of demonstratives is illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Emphatic and non-emphatic demonstratives in Ponapean (Diessel 1999, p. 53; Rehg 1981, pp. 144, 149).

According to the above table, the unmarked structure of ohlet ‘this man’ takes the form of ohl menet ‘this man here’ if used emphatically. If speakers use an emphatic DEM for selecting the relevant object out of a presupposed set of objects, the CL obtains contrastive function.

Moreover, Ponapean has a general CL u- that can be used to count the majority of nouns. There is also a subtle discrepancy between specific CLs and the general CL when it comes to contrast, in that the occurrence of the general CL in emphatic demonstratives is heavily restricted. Only the singular emphatic form for referents near speakers we(t) is common. Thus, the general CL u- is mostly used with the proximal DEM, while the grammaticality of the emphatic forms for referents near hearers (wen) and away from speakers and hearers (wo) is questionable (Rehg 1981, p. 149). Thus, the distribution of specific vs. general CLs in contrastive contexts in Ponapean looks very much like that of XSM.

4.3.4. Summary

So far, this paper has introduced the contrastive function of CLs in XSM, Thai, Vietnamese, and Ponapean. Table 7 summarizes the different constructions of CL use (both specific and general CLs if the language has both) for individuation, singularity, and contrast marking.

Table 7.

Constructions where CLs express different functions in XSM, Thai, Vietnamese, and Ponapean.

As shown in Table 7, the CLs have developed contrastive function in all four languages in either the DEM construction or the DEM plus the ADJ construction (cf. XSM), even though they are from different families, three of which belong to East and mainland Southeast Asia.

In the languages that have a general CL (XSM, Ponapean, and Vietnamese but not Thai), specific and general CLs develop their contrastive function in separate ways because of their different degrees of semantic specificity or generality. In fact, they follow two different, mutually exclusive pathways.

In languages where specific CLs develop a contrastive function (XSM, Ponapean, and Thai), specific CLs obtain their contrastive function through pragmatic inference, while they still occur in the same syntactic position that they take to express other functions (e.g., singular in the XSM and Thai DEM constructions, and emphasis in the Ponapean emphatic DEM construction). The exact interpretation of the specific CL always depends on the concrete context and the objects involved. Thus, the contrastive use of specific CLs is motivated by the classificational function of specific CLs, i.e., their ability to subsume particular perceptions under a certain concept to identify it (Bisang 2008). In other words, specific CLs intrinsically have the potential to develop a contrastive function, and the trigger of this development is a bridging context, as it is met in the exophoric situation given in our experiment with its features [+distant] and [−unique]. This grammaticalization process does not involve semantic bleaching. On the contrary, it is exactly the semantics of specific CLs that enables them to acquire contrastive function.

In contrast, the Vietnamese general CL cái is semantically so general that it is able to combine with almost any count noun irrespective of its semantics. This clearly contributes to its frequency, which makes it a forerunner in grammaticalization in the CL system. Thus, it has obtained a contrastive function by a path which is not available to specific CLs, i.e., it has entered a new syntactic slot.

Though much research is required to fully understand the exact mechanisms of grammaticalization from CL to contrastive marker in different languages, one can already see at this stage that grammaticalization in the languages discussed in this paper does not necessarily involve continuous semantic bleaching. Instead, the process that a CL undergoes largely depends on whether it is a general or specific CL. Which type of CLs would process further largely depends on the context and the constructions that they are in. In spite of this, the contrastive function of CLs is found in various languages, including three EMSEA languages.

5. Conclusions

This study started out from the question of whether CLs in Xiamen Southern Min can be associated with reference if they have no bare classifier construction [CL N] associated with definiteness/indefiniteness. To test this, we looked at the difference between specific CLs and general CLs and their referential potential in an exophoric context provided by the “Hidden color-chips” task in an environment characterized by the three factors of distance, visibility, and uniqueness. This method contrasts with previous studies based on endophoric contexts as they are found in narratives (Erbaugh 2002, 2013; Erbaugh and Yang 2006). Our quantitative and qualitative analyses showed that the use of specific vs. general CLs is associated with reference in the following specific pragmatic contexts:

- Compared with using a bare noun, speakers are clearly more likely to use the DEM construction when the object is clearly visible to the speaker.

- In cases with [+unique], speakers are significantly more likely to use a specific CL when the object has [−distant] than when it has [+distant].

- In cases with [+distant], speakers are significantly more likely to use a specific CL if the referents have [−unique], and a general CL if they have [+unique].

Additionally, the qualitative analysis shows that if the object has [−unique] and the first reference with a general CL is not sufficient to identify it, a specific CL is much more likely to be used in later mentions (Effect IV).

Effects I and II can be explained by the fact that referents which are cognitively more accessible (i.e., close and visible) tend to be further specified. Effect III and the qualitative analysis reveal that specific CLs can deictically mark contrast in the cases of [−unique] and [+distant]. The functional extension from specific CL to contrastive marker is arguably motivated by the insufficiency of referential clues in the demonstrative construction in the specific context with [+distant] and [−unique].

Moreover, this paper briefly introduced another environment [ADJ CL N] where specific CLs are used for contrast in XSM and illustrated the contrastive use of CLs in three other languages, i.e., Thai, Vietnamese, and Ponapean. This illustration shows that both specific and general CLs are potential sources of contrastive markers, but their grammaticalization follows two mutually exclusive pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.H.; methodology, Q.H.; data collection, Q.H.; data curation, Q.H.; data analysis, Q.H. and W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.H.; writing—review and editing, Q.H. and W.B.; visualization, Q.H.; supervision, W.B.; project administration, W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Department of English and Linguistics of the Univerisity of Mainz and the German Academic Scholarship Foundation at different stages.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Joint Ethics Committee of Departments 05 and 07 of the University of Mainz on 11 April 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all the participants to conduct the experiment and publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to qihuang@uni-mainz.de.

Acknowledgments

We thank Binbin Xu and Mingyi Hu for their help in the participant recruitment for the experiment, and we thank all the participants for their cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items used in the experiment and parameters they are associated with.

Table A1.

Items used in the experiment and parameters they are associated with.

| First Round: | ||||||

| Item Number | Distance | Visibility | Uniqueness | Expected CL Type | Item | Expected CL |

| 1 | close | unblocked | unique | general | pen case | é |

| 2 | close | blocked | unique | specific | soap | dě |

| 3 | close | unblocked | unique | specific | cap | dǐng |

| 4 | close | unblocked | non-unique | specific | card | dniū |

| 5 | mid-far | unblocked | unique | specific | umbrella | gī |

| 6 | mid-far | unblocked | unique | general | box | é |

| 7 | far | blocked | unique | specific | cellphone | dě |

| 8 | far | unblocked | unique | specific | towel | dě |

| 9 | far | unblocked | non-unique | specific | book | bǔn |

| 10 | far | unblocked | unique | general | wallet | é |

| Second Round: | ||||||

| Item Number | Distance | Visibility | Uniqueness | Expected CL Type | Item | Expected CL |

| 1 | close | unblocked | unique | general | cup | é |

| 2 | close | blocked | unique | specific | chocolate | dě |

| 3 | close | unblocked | unique | specific | book | bǔn |

| 4 | close | unblocked | non-unique | specific | tangerine | liáp |

| 5 | mid-far | unblocked | unique | specific | leaf | hióh |

| 6 | mid-far | unblocked | unique | general | flask | é |

| 7 | far | blocked | unique | specific | banana | tiáu |

| 8 | far | unblocked | unique | specific | sponge | dě |

| 9 | far | unblocked | non-unique | specific | paper | dniū |

| 10 | far | unblocked | unique | general | paper bag | é |

Notes

| 1 | Southern Min is a Sinitic language that is mainly spoken in Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan, and Taiwan and generally has 30 to 40 CLs in use (Chappell 2018). |

| 2 | The romanization is adapted by the authors, using the Minnan Dialect Phonetic Alphabet introduced in Lin (2007). |

| 3 | Given that nouns in classifier languages are often interpreted as transnumeral, which need either individuation (Greenberg 1972) or atomization (Chierchia 1998), their use as explicit markers of singular in the context of demonstratives is typologically remarkable. It remains an open question as to what extent this could be seen as another type of singulative (Corbett 2000), which is not based on singling out individuals from collectives but rather individual items from transnumeral nouns. |

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2000. Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Devices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, Keith. 1977. Classifiers. In Language. New York: Linguistic Society of America, vol. 53, pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisang, Walter. 1999. Classifiers in East and Southeast Asian languages Counting and beyond. In Numeral Types and Changes Worldwide. Edited by Jadranka Gvozdanović. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 113–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisang, Walter. 2008. Grammaticalization and the areal factor: The perspective of East and mainland Southeast Asian languages. In Typological Studies in Language. Edited by María José López-Couso and Elena Seoane. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 76, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, Wallace L. 1976. Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In Subject and Topic. New York: Academic Press, pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, Wallace L. 1980. The Pear Stories: Cognitive, Cultural, and Linguistic Aspects of Narrative Production. New York: Ablex Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Hilary. 2018. Southern Min. In The Mainland Southeast Asia Linguistic Area. Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs 134. Edited by Alice Vittrant and Justin Watkins. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 176–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across language. Natural Language Semantics 6: 339–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Greville G. 2000. Number. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, John Peter. 1976. What Are Noun Classifiers Good For? Paper presented at 12th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, IL, USA, April 23–25; London: University of Western Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives: Form, Function and Grammaticalization. Typological Studies in Language 42. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R. M. W. 2003. Demonstratives: A cross-linguistic typology. Studies in Language 27: 61–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfield, N. J., and Jürgen Bohnemeyer. 2001. Hidden colour-chips task: Demonstratives, attention, and interaction. In Manual for the Field Season 2001. Edited by Stephen C. Levinson and N. J. Enfield. Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics 3554441. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, Mary S. 1986. Taking stock: The development of Chinese noun classifiers historically and in young children. In Noun Classes and Categorization (Typological Studies in Language). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 7, pp. 399–437. [Google Scholar]

- Erbaugh, Mary S. 2002. Classifiers are for specification: Complementary functions for sortal and general classifiers in Cantonese and Mandarin. Cahiers de Linguistique-Asie Orientale 31: 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, Mary S. 2013. Classifier choices in discourse across the seven main Chinese dialects. In Studies in Chinese Language and Discourse. Edited by Zhuo Jing-Schmidt. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 2, pp. 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, Mary S., and Bei Yang. 2006. Two general classifiers in the Shangai Wu dialect: A comparison with Mandarin and Cantonese. Cahiers de Linguistique-Asie Orientale 35: 169–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Joseph. 1972. Numeral classifiers and substantival number: Problems in the genesis of a linguistic type. In Working Papers on Language Universals. Stanford: Stanford University, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Bernd. 2018. Grammaticalization in Africa: Two contrasting hypotheses. In Grammaticalization from a Typological Perspective. Edited by Heiko Narrog and Bernd Heine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundius, Harald, and Ulrike Kölver. 1983. Syntax and Semantics of Numeral Classifiers in Thai. Studies in Language 7: 165–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, Katalin. 1998. Identificational Focus and Information Focus. Language 74: 245–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Information Structure and Sentence Form: Topic, Focus, and the Mental Representations of Discourse Referents. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, Stephen C. 2016. Turn-taking in Human Communication—Origins and Implications for Language Processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20: 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, Chinfa, and Liching Livy Chiu. 2014. Nominal Structure in “Li Zhi Ji (荔枝記)” (Wanli 萬曆 Edition). Taiwan Journal of Linguistics 12: 81–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Rulong. 2007. 闽南方言语法研究 [Studies on Southern Min Grammar]. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xuping, and Walter Bisang. 2012. Classifiers in Sinitic languages: From individuation to definiteness-marking. Lingua 122: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Baoqing, ed. 2007. 普通话闽南方言常用词典 [Mandarin-Southern Min Dialect Dictionary], 1st ed. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Löbel, Elisabeth. 2011. Classifiers versus genders and noun classes: A case study in Vietnamese. In Gender in Grammar and Cognition. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 259–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Tuong Hung. 2004. The Structure of the Vietnamese Noun Phrase. Boston: Boston University Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Rehg, Kenneth L. 1981. Ponapean Reference Grammar. In Ponapean Reference Grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, John R. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 97. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vittrant, Alice, and Marc Allassonnière-Tang. 2021. 31 Classifiers in Southeast Asian languages. In The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. Edited by Paul Sidwell and Mathias Jenny. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 733–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jian. 2015. Bare classifier phrases in Sinitic languages: A typological perspective. In Diversity in Sinitic Languages. Edited by Hilary M. Chappell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 110–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Changji, Jianshe Wang, and Ronghan Chen, eds. 2006. 闽南方言大词典 [Dictionary of Southern Min Dialects], 1st ed. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).