Abstract

What happens when recognized and diverse conditioning factors of linguistic variation are omitted from analysis and/or are not analyzed under a single analytical procedure? This paper explores the consequences of such a choice on data interpretation and, consequently, (socio)linguistic theorization. Utilizing Twitter-style English in the Philippines (EngPH) as a case study, I employ the Twitter Corpus of Philippine Englishes (TCOPE) primarily to investigate and elucidate variations in three morphosyntactic variables that have been previously examined using a piecemeal approach. I propose a holistic quantitative approach that incorporates documented linguistic, social, diachronic, and stylistic factors in a unified analysis. The paper illustrates the impacts of adopting this holistic approach through two statistical procedures: Bayesian regression modeling and Boruta feature selection with random forest modeling. In contrast to earlier research findings, my overall results reveal biases in non-unified quantitative analyses, where the confidence in the effects of certain factors diminishes in light of others during analysis. The adoption of a unified analysis or modeling also enhances the resolution at which variations have been examined in EngPH. For instance, it highlights that presumed ‘universals’, such as the hierarchy of linguistic > stylistic > diachronic > social factors in explaining variation in some domains, is contingent on the specific variable under examination. Overall, I argue that unified analyses reduce data distortion and introduce more nuanced interpretations and insights that are critical for establishing a well-grounded empirical theory of EngPH variation and language variation as a whole.

1. Introduction

Many contemporary quantitative studies on English used in the Philippines (EngPH)—particularly those focusing on the dominant variety ‘Philippine English’ or PhE1—have developed a growing interest in studying the different types of variation within EngPH at various linguistic levels. For instance, Samejon’s (2022) study focused on phonological variation in PhE and investigated how linguistic factors like phonological environment and suffixation as well as social factors like sex and profession influence the production of the word-final /z/ sound in acrolectal PhE speakers. Other scholars like Collins et al. (2014) have examined the patterns of morphosyntactic variation using PhE corpus data and found genre to be a robust factor of variation. Gonzales and Hiramoto (2020) also investigated similar types of alternations in Philippine Chinese English or Lannang English data, with an emphasis on the impact of ethnicity and region on variation. And more recently, Gonzales (2023a) used Twitter corpus data to explore morphosyntactic and phrasal variations in EngPH as used in Twitter, considering factors such as city, while Hernandez (2023) analyzed variation in the adoption of the subject–verb agreement rule in PhE and found that the rates of adoption varied depending on the academic register.

Except for a few studies like Samejon’s (2022), these quantitative studies tend to overlook a critical pitfall. They often fail to consider the influence of well-established factors on the variable of focus. For instance, the literature has shown that diachronic as well as stylistic factors like genre and register significantly condition the observed variations. However, subsequent studies, like Gonzales and Hiramoto (2020) on Manila Chinese English (i.e., Lannang English) in the Philippines, frequently neglect or gloss over these variables in their analyses, despite evidence of ongoing generational language shifts in the Lannang community (Gonzales 2023c) and the existence of distinct stylistic variations in English used by Chinese Filipinos and/or Lannangs (e.g., using localized Lannang English for texting or communication with friends, but using standard English for school; author fieldwork notes, 2018). This oversight is problematic because neglecting such robust factors may inadvertently emphasize the role of ethnicity and geographic region in variation when the impact of stylistic and diachronic factors might be more substantial. In essence, the current research often fails to account for well-documented conditioning factors and their relative contributions to variation. This oversight can potentially bias the study’s findings, hindering a more accurate understanding of English variation in the Philippines.

Moreover, most quantitative studies tend to focus on a narrow set of variables, often of a social, diachronic, or stylistic nature, such as ethnicity and region in Gonzales and Hiramoto’s (2020) study, or genre and register in Collins et al. (2014) and Hernandez’s (2023) research. This limited scope can create the illusion that only social, diachronic, and stylistic factors influence internal variation in EngPH when, in reality, the situation can be more intricate. It is known, for example, in sociolinguistic research, that linguistic factors can be more robust predictors of sociolinguistic variation than social factors (Gonzales 2023b, 2024; Grafmiller et al. 2018; Hansen Edwards 2018). For instance, in Gonzales’ work on Lánnang-uè affixes, the influence of affix type and affix language had relatively higher impact on grammaticality judgments compared to social factors like attitudes and age. Bohmann and Babalola (2023), on the other hand, found that verbal–semantic, discourse–contextual, and morpho-phonological—in other words, linguistic—factors had stronger conditioning effects on verbal past inflection use in Nigerian English compared to most social factors such as age and gender. So, excluding linguistic factors, whether deliberate or not, can be problematic, as social, diachronic, and stylistic factors may be mistakenly perceived as exclusive and robust factors, which can distort our understanding of variation in this variety.

In summary, even though there has been a recent increase in variationist research, achieving a thorough comprehension of variation in EngPH remains a challenging task. There remains a need to uncover the spectrum of linguistic, stylistic, diachronic, and social factors that condition these variations and to determine how these variables collectively shape the variations and their respective importance in relation to each other.

The present study will examine three linguistic variables that have previously been noted to display a wide range of variation, with findings potentially distorted due to inadequate consideration of established robust social, diachronic, linguistic, and stylistic factors, as previously discussed (Gonzales 2023a). These variables encompass (1) the utilization of the irregular past tense morpheme -t, (2) double comparatives, and (3) subjunctive were in subordinate counterfactual clauses. Unlike previous studies that only considered a reduced (exclusive) set of factors, this paper seeks to expand on prior research by integrating established social factors, as identified in previous studies, into the analysis. Additionally, it will investigate how stylistic factors, such as formality, as well as diachronic factors, which have been demonstrated to be robust variables (Collins et al. 2014), might impact these three patterns of variation in EngPH. My research contributes to the existing body of work by also taking into account linguistic factors in the analysis, which, as mentioned earlier, have shown to be more effective conditioners of variation compared to social factors (Bohmann and Babalola 2023). It will consider, for each of the three linguistic variables investigated, linguistic factors that prior research has identified to be robust predictors of variation, testing whether the observations made in general English in prior work corroborate the patterns observed in the current EngPH data.

In essence, the paper advocates for a comprehensive four-pronged, ‘holistic’, quantitative approach (encompassing social, stylistic, linguistic, and diachronic aspects) to enhance the understanding of EngPH variation while minimizing potential biases. As will be elaborated later, the results of this study show that linguistic factors generally play a significant role in EngPH variation, underscoring the importance of considering linguistic factors in the analysis of EngPH. However, the results also indicate that the dominance of linguistic factors is not universal, and the relative significance of linguistic, diachronic, social, and stylistic factors varies depending on the specific linguistic variable being examined. This underscores the need for including non-linguistic variables in any analysis of EngPH.

This approach to analyzing variation (i.e., analyzing variables as additive factors that contribute to variation in varying degrees instead of deterministic ones) aligns with the constructionist variationist framework employed in this paper (Eckert 2012; Labov 1972), which views linguistic variables as carriers of multiple social meanings and indices, such as stylistic, age-/generation-related, and gender-related meanings, rather than as factors with a one-to-one correspondence to a social factor (e.g., an exclusively ‘Filipino’ or exclusively ‘feminine’ variable). Embracing a constructionist perspective, this paper offers an alternative outlook on the variability within EngPH, challenging the predominantly deterministic and monolithic approach dominant in the field.

In Section 2, an analysis of the variables under scrutiny is undertaken, with a specific focus on examining existing research findings that might shed light on variations. Section 3 delves into the intricacies of the methodology, encompassing the data source and the various analyses performed. Advancing to Section 4, I present the results based on the variables of interest and endeavor to elucidate the observed variation. Concurrently, I highlight how the holistic approach advocated in this paper serves to alleviate biases and distortions that have afflicted previous research. In the subsequent section, Section 5, I take a broader perspective, offering a comprehensive comparison and discussion of results and delving into the implications of not embracing a holistic approach. This is succeeded by Section 6, where I furnish a summary of the paper, outline some limitations of this study, and conclude with some final remarks.

2. EngPH Variables under Study

2.1. Past Tense Morphology

EngPH is known for its regularization of irregular verb forms. Although some speakers use the irregular -t morpheme (e.g., spoilt) to mark the past/participle for a subset of verbs (i.e., burn, dream, lean, leap, learn, smell, spell, spill, and spoil), most speakers were found to use the regular -ed morpheme (e.g., spoiled). This tendency to regularize was noted in the 1990s (Borlongan 2011) but recent work in the 2020s has shown a slight decrease in regularization tendencies (Gonzales 2023a), that is, the use of -ed/-t morphemes is becoming more variable.

Factors that have been noted to favor the use of irregular morphology in the 2010s and 2020s include geographical region, specifically the island group or city in which the utterances were spoken (Gonzales 2023a). Those in the Visayas island group were observed to exhibit less regularization (e.g., spoilt instead of spoiled) than those in Luzon and Mindanao. Residents of cities like Puerto Princesa and Iligan seem to be more inclined to regularize irregular verbs compared to other cities like the capital city Manila, while speakers in Jolo tend to be more reserved in their use of regular -ed compared to all these cities. However, it should be noted that the differences between regions in prior descriptions appear rather small, leading to the question of whether such differences or effects actually exist when considering other conditioning factors.

Apart from geographical considerations, several linguistic or structural factors have been identified as influential in shaping variations in English past tense morphology, although not in the context of EngPH, specifically. The role of a lexeme’s function emerges as a significant factor: research shows that when lexemes such as burn or dream serve as adjectives, the -t form is more commonly employed, while their use as verbs results in the realization of the past tense as -d (Levin 2009, p. 80; Peters et al. 2022; Quirk et al. 1985). Levin (2009, p. 81) specifically highlights that this contrast depends on the specific verb, with verbs like burn producing significantly more -t forms when used as participial adjectives compared to their usage as past participle verbs. Among lexemes with a verbal function, the form of the verb itself appears to play a notable role in determining past tense morphology realization. Preterite or simple past forms tend to favor the -ed variant, while past participle forms tend to favor the -t variant (Levin 2009; Quirk et al. 1985). Utterances featuring past participles in a passive voice context tend to attract -t variants (e.g., They wanted the lessons to be learnt), whereas those in active voice tend to attract -ed variants (e.g., I have learned in this game) (Levin 2009, p. 73). Lastly, the frequency of words also appears to influence patterns of past tense morphological variation. More frequently used lexemes (e.g., learn) tend to favor the -t form, whereas less common ones (e.g., leap) tend to favor the -ed form (Bybee 2006; Peters et al. 2022).

2.2. Comparative Marking

Scholars often highlight the use of double comparatives (e.g., more flexibler, more happier, more greater) as a noteworthy characteristic of EngPH (Bautista 2000; Borlongan 2011; Dita et al. 2022). Although single comparatives (e.g., more flexible, more happy, greater) are commonly used in EngPH, the double comparative is also sometimes employed (Borlongan 2011). A recent analysis suggests that this tendency to use the innovative construction has recently increased between the 1990s and 2020s (Gonzales 2023a). Like the variation seen with -ed/t, there appears to be a trend towards greater variability in the use of comparison markers. Previous research indicates that the variability in the most recent data appears to be sensitive to the pressures of geographical location, with individuals from the Visayas island group and Butuan and Jolo using the double comparative variant over the single comparative variants slightly more frequently than in other conservative regions such as the Luzon Island group and Manila city (Gonzales 2023a).

Apart from the geographical region, various social factors have been observed to shape the variation in comparative marking. González-Díaz (2005) pointed out that double comparative forms likely lack pragmatic or emphatic value, but have social value. He noted that the usage of double comparative marking indexes non-standardness, lack of education, and lower socioeconomic status (González-Díaz 2005, p. 651).

While the double comparative form is said to be devoid of pragmatic meaning, several studies have found other linguistic factors to impact comparative marking in English. Earlier research has shown that double comparatives occur more frequently with a term of comparison headed by than (e.g., John is more taller than Bill) compared to those without a than comparison (e.g., John is taller) (González-Díaz 2005, p. 634). The presence of two terms of comparison increases the likelihood of the use of the double comparative even further (e.g., John is more taller than Bill than Peter) (Seuren 1973, p. 634). González-Díaz (2005) additionally mentioned that double comparative marking is more prevalent when used with downtoners (e.g., a bit, slightly, somewhat, a lot, much, far) and intensifiers. Other factors known to influence variations in comparatives, as identified by Säily et al. (2018), encompass the presence of complements, proximity to the sentence boundary, syntactic position (whether attributive or predicative), and the number of syllables in the adjective. However, it is worth noting that these factors have primarily been employed to explain the variation in periphrastic and inflectional comparative marking, rather than the distinction between single and double comparative marking. Nevertheless, given that the single–double comparative alternation is a feature of the comparative marking system, I suspect that these factors would also potentially exert an influence on the choice between single and double comparative marking.

2.3. Past Subjunctive and Was/Were

Users of EngPH tend to use the past subjunctive were (e.g., If she were to be invited…) more than was (e.g., …if that was what she fancied) in subordinate clauses with first and third person singular subjects expressing a hypothetical condition (Borlongan and Dita 2015; Collins et al. 2014, p. 275). This preference is most salient in the 1960s, but has been observed to decline over the decades (Collins et al. 2014). Recent studies have identified a crossover effect where speakers of EngPH have started to use the indicative was more frequently than the subjunctive were (Gonzales 2023a). While a preference for was has been noted, it was shown that the choice between was and were is not categorical, i.e., there is still considerable variation in the realization of the subjunctive in subordinate counterfactual clauses.

As the studies in the earlier paragraph show, the was/were alternation in the Philippine context is influenced by diachronic factors, with a higher frequency of were use in the 1960s. The alternation has been claimed not to be sensitive to genre or other stylistic contexts (Collins et al. 2014), but perhaps sensitive to region (Gonzales 2023a). Speakers in the Visayas island group were found to be leaders in the use of indicative was, with Luzon and Mindanao trailing behind. Those in the cities of Jolo, Laoag, and Tagbilaran use the indicative was more frequently than cities like Manila and Masbate.

Variationist research on was/were patterns in English as used in other parts of the world share several fundamental findings, the most important finding being the conditioning effect of clause polarity. The linguistic factor “polarity” seems to be a pivotal factor in determining the choice between was and were, particularly in plural existential contexts (e.g., there was many dogs vs. there were many dogs). It has been observed that was tends to convey a positive tone and is better suited for emphatic use than were, making were the preferred choice in negative statements (Tagliamonte 1998; Waller 2017). Additionally, was has been linked to informality (Skevis 2014; Waller 2017), making it the favored variant in colloquial settings. The effect of polarity on was/were variation is claimed to be present across most varieties of English, but “differs in nature from one variety to the next” (Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012, p. 139).

Adverbial triggers and diachronic factors have also been identified as influential elements in conditioning the usage of subjunctives in English. Subjunctives often appear in constructions starting with words such as if, but if, as if, for if, and even if (Kastronic and Poplack 2021; Vaughan and Mulder 2014). Furthermore, subjunctive forms have exhibited a declining trend over time, particularly in British English, with American English showing a different pattern (Kastronic and Poplack 2021). However, it remains unknown whether the specific type of trigger and diachronic factors have a bearing on the was/were variation in past subjunctives.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

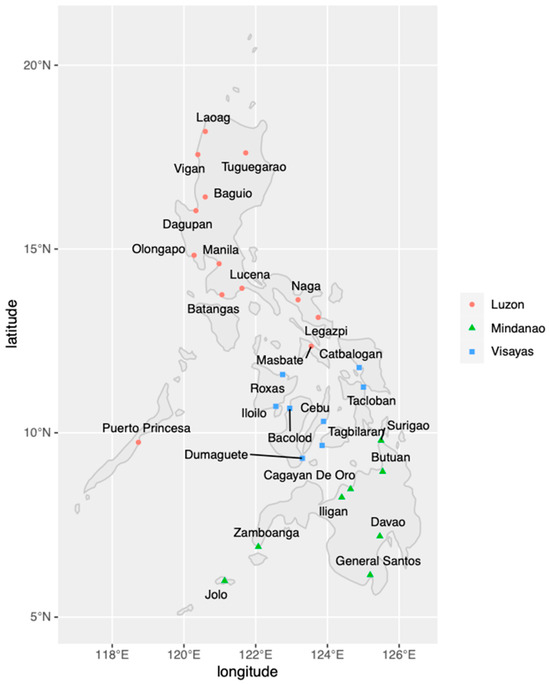

This study analyzes data extracted from the Twitter Corpus of Philippine Englishes (TCOPE), a corpus of 135 million words sourced from 27 million tweets originating in 29 different cities across the Philippines (Figure 1) (Gonzales 2023a). The data span the years from 2010 to 2021. Despite its primary focus on a specific style of EngPH (i.e., Twitter-style PH), which may differ from written and spoken varieties or styles of EngPH, TCOPE was selected over other well-known corpora of Philippine English, such as the Philippine component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-PH). This choice was motivated by several factors, including its extensive size, the availability of sociolinguistic metadata like geographical coordinates and part-of-speech tags, and its potential for making direct comparisons. Analyzing data from TCOPE enables me to test whether the claim that social and diachronic factors are more reliable determinants of variation, as compared to linguistic and stylistic factors, holds true. Using the ICE-PH corpus would not allow me to evaluate whether the comprehensive four-pronged approach I currently advocate for (i.e., considering social, stylistic, linguistic, and diachronic factors) effectively mitigates bias, as prior research relied on TCOPE rather than alternative corpora like ICE-PH. Consequently, TCOPE emerges as the most suitable data source for this study.

Figure 1.

Regions of interest (with cities grouped by island groups).

3.2. Data Pre-Processing and Variable Coding

The current study is interested in analyzing the variation in three variables, that is, past tense morphology, comparative marking, and was/were. As such, three datasets from TCOPE have been extracted to fulfill the research objectives. Each of these only contains tweets relevant to the variable studied. For example, the comparison marking dataset only has utterances with single comparison and those with double comparison marking to investigate comparative marking variation.

In each dataset, every utterance was coded for the linguistic variable of focus (i.e., the dependent variable, e.g., single comparative vs. double comparative) and was also coded for the following factors based on the specific dataset (i.e., the independent variables) (see Table 1). The four macro-types of independent variables were selected because they fulfilled the goals of the study, that is, to assess the benefits of the holistic approach to analyzing variation. The selection of specific independent variables was guided by the identification of established influential factors in the literature review. Some factors mentioned in the review, like profession and sex, were excluded due to their absence in the corpus, as there was no systematic means of obtaining such information. Nonetheless, I made every effort to include as many relevant factors as possible.

Table 1.

Predictors or independent variables coded for each of the three datasets or models.

The diachronic and social coding had already been completed, as TCOPE contained encoded data for the year, island group, and city for each utterance. Additionally, user information, including user IDs, was readily available within TCOPE. However, details regarding linguistic aspects and other stylistic variables related to formality and informationality had to be derived through a combination of manual and computational techniques.

Most of the linguistic factors were initially coded in a semi-automated manner using functions in the R environment. This process relied on regular expressions (RegEx)-based coding, which was applied to the raw, part-of-speech, and dependency-parsed versions of the corpus, all of which were accessible within TCOPE. Manual checking was performed after the semi-automatic coding to reduce noise in the dataset. For instance, in the case of the variable ‘number of comparisons’, the initial step involved coding utterances that included comparison terms. This was achieved by applying a function to count the occurrences of than comparisons if the utterance matched the RegEx expression than. Subsequently, I conducted a manual review of the data in collaboration with a research assistant to verify whether the instances that were coded indeed contained than comparisons.

The frequency index for the past tense morphology variable was determined through a multi-step process. Initially, the relative frequency of the specific lexemes of interest was calculated within three widely used corpora that contain data related to EngPH, namely NOW, GloWbE, and ICE-PH. Raw frequency counts were initially collected for each of these lexemes. Subsequently, a normalization process was applied, involving the transformation of the frequency scores through z-scoring, a process that involves standardizing data by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. This normalization allowed for the assessment of the relative frequency of each lexeme within the respective corpus. To arrive at the frequency index presented in Table 2, the three z-scored values for each lexeme were averaged. This index was linked to the past tense morphology dataset for further analysis.

Table 2.

Raw and normalized frequency of lexemes under study in the NOW, GloWbE, and ICE-PH corpus.

Regarding the stylistic variables, it is important to mention that the three datasets do not contain actual stylistic information, so this information had to be obtained computationally. Two stylistic dimensions—formal–informal and informational–interpersonal—were derived based on the primary linguistic parameters identified by Grafmiller et al. (2018) for English. Following the method described by Grafmiller et al., I initially coded common linguistic features or correlates associated with formality and interpersonality using the RegEx coding procedure outlined above. The correlates identified are as follows:

Informal–formal dimension

- Length of utterance (words)

- Quantity of subordinating conjunctions

- Quantity of passives

- Type-to-token ratio

- Presence of stranded preposition

Informational–interpersonal dimension

- Noun-to-verb ratio

- Mean length per word (character)

- Quantity of nouns

- Quantity of passives

- Length of utterance (words)

- Quantity of personal pronouns

- Presence of stranded preposition

Subsequently, I employed principal components analysis (PCA) (Baayen 2008; Lê et al. 2008), a technique that combines the original linguistic correlates to create new and orthogonal or independent/uncorrelated variables or dimensions. From this set of newly derived factors, I identified one that best represents either formality or informationality, as discussed in the literature, based on the numerical contributions of the initial linguistic features. This continuous variable signifies the degree of formality or informationality and was linked to the corpus for further analysis.

After this, I systematically cleaned and pre-processed my datasets to ensure that no duplicate utterances were analyzed. Exactly 10% of the utterances in all three datasets (i.e., the test data) were set apart to allow for the evaluation of the predictive capabilities of the model, which is necessary to ensure the reliability of the results.

3.3. Data Analysis

In contrast to previous studies that primarily utilize descriptive statistics involving only one or a few variables (Borlongan and Dita 2015; Collins et al. 2014), this study embraces a holistic approach to analyzing variation inspired by the Labovian variationist tradition (Labov 1972), a tradition that emphasizes the incorporation of both linguistic and social factors in the analysis of variation. This makes it distinct from the bulk of prior EngPH investigations. Another distinguishing marker is the study’s integration of established robust variables into a unified analysis. This enables us to determine the relative significance of these variables and, more broadly, to mitigate potential biases and distortions observed in prior research. Additionally, this study adopts less commonly used but highly robust methodologies: it employs the Bayesian framework to draw inferences about the generalizability of the observed effects, offering a probability-based measure of confidence for readers to assess their confidence in extending the results to a broader EngPH context. It also employs the Boruta algorithm for feature selection, which allows one to identify the (relative) importance of standardized social, linguistic, diachronic, and stylistic factors in explaining and predicting EngPH variation. These methodologies, in conjunction, add more nuance to our current understanding of EngPH morphosyntax.

3.3.1. Bayesian Regression Modeling

Using the coded variables explained in Section 2.2, I fitted a logistic regression model on each of the three datasets, utilizing the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm (Franke and Roettger 2019; Makowski et al. 2019; McElreath 2020) with the brms package in the R environment (Bürkner 2017; R Core Team 2015). A total of three models were fitted: one for past tense morphology, one for comparative marking, and one for was/were. Random intercepts were included for both lexeme and user, and, for the comparative marking model, intercepts of part-of-speech of surrounding words were also included. I only considered lexemes, POS, and users with enough tokens (i.e., more than 5) as individual factor levels, following Levshina’s lead (Levshina 2016, p. 253). Lexemes, POS categories, and users with fewer than five utterances or tokens were grouped together under the category ‘other’.

Logistic regression was selected because the study is interesting in accounting for binary dependent variables (e.g., single vs. double comparison marking). I chose not to conduct a frequentist-oriented regression analysis because, while Bayesian procedures are computationally demanding and yield results comparable to frequentist methods (e.g., models with p-values), the Bayesian approach offers a more direct and intuitive quantification of uncertainty by utilizing posterior distributions. Instead of relying on p-values, the highly arbitrary notion of ‘significance’, and sometimes challenging-to-interpret confidence intervals, Bayesian methods provide probability distributions for the model parameters, which offer a clear representation of the researcher’s confidence in various parameter values. Furthermore, Bayesian analysis allows for insights into the absence of an effect, a capability not present in the frequentist framework (McElreath 2020; Vasishth and Nicenboim 2016). Finally, Bayesian methods are better suited for handling complex models with numerous predictors and interactions, making them particularly advantageous in variationist regression analyses, where linguistic variation is often influenced by multiple factors and their interactions. They can provide robust estimates even in highly complex models.

For each of the 3 models, I ran 4 Markov chains. To mitigate any initial sampling bias, I incorporated a warm-up or burn-in period of 10,000 iterations for each chain. Furthermore, I set the thinning parameter to 2. For the models’ intercept and slopes, I employed weakly informative priors, specifically a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 5 (Levshina 2016, p. 252). Notably, my experimentation with various prior choices, including uniform and Cauchy distributions with a range of [0, 5], revealed that these choices did not exert a significant influence on the resulting posterior distributions. In order to achieve convergence, I adhered to the recommendation made by Vehtari et al. (2021, p. 683) by closely monitoring the values of and effective sample size (ESS). In particular, I kept values below 1.01 and ensured that ESS values were consistently above 400.

The results of the Bayesian models is best summarized through posterior draws (Bürkner 2017). From these results, I can determine which predictors condition variation by looking at the pd. According to the literature and related studies (MacKenzie 2020; Makowski et al. 2019), a predictor is said to affect the dependent variable if its median value is far from zero or if the credibility intervals around the median do not include zero. The Bayesian statistical measure ‘probability of direction’ (pd) is associated with effect existence and will be utilized to evaluate the degree of (un)certainty with respect to the existence of the effect. A higher pd (i.e., close to 1) points to a higher confidence that a non-zero effect is present, while a lower pd suggests that the effect may not exist (Makowski et al. 2019). I will be using pd to examine the likelihood of impact of the factors on variation in EngPH. I will also be considering the median, as it indicates the magnitude of the effect, and will be used for the ranking of predictors.

The median values or estimates in any regression model like the Bayesian regression models fitted here tell us the magnitude of the effect. However, since the independent variables in the models are not scaled or put in a similar scale (e.g., year: 2010 to 2021, stylistic formality: −4.45 to 10.9), the coefficients are distorted and cannot be used for comparison of importance or relative feature importance straightforwardly, either for comparison of variables within the model or across the three models. One solution would be to scale and center the variables before running the regression models; however, this presents a problem, as most of the independent variables in the models are not numerical, so scaling procedures such as centering and z-scoring cannot be directly implemented on the variables before the Bayesian regression analysis. Furthermore, if standardization was implemented before the Bayesian analysis, important information regarding the actual effects and the unit of analysis (e.g., how likely a person will use subjunctive was over were from one year to the next) will be lost. As such, this paper adopts another algorithm to determine the degree and, consequently, the ranking of variable importance in explaining and predicting variation: the Boruta algorithm.

3.3.2. Boruta Algorithm with Random Forest Modeling

The Boruta algorithm is a machine learning technique used for the purpose of standardized feature or variable selection (Kursa and Rudnicki 2010). This method was employed to determine the most significant features or variables within a given dataset. The process involves several steps.

Initially, the algorithm generates a shadow dataset, which is essentially a duplicate of the original dataset with the values of one or more features randomly shuffled. This shadow dataset is designed to represent features that lack genuine importance (i.e., nonsense features). Subsequently, the Boruta algorithm combines the original dataset with this shadow dataset, creating a larger dataset that encompasses both the actual features and their corresponding randomly shuffled counterparts. The next step is to utilize a random forest model for training on this merged dataset. The role of this model is to predict the target dependent variable, using information from both the real features and their shuffled counterparts.

Following the training phase, the algorithm assesses the importance of each feature, through a z-scored mean decrease accuracy. It does so by comparing how well the model performs when using the real features in contrast to the shuffled, random features. Specifically, it identifies whether a feature exhibits a higher z-score compared to the maximum z-score of its shadow features. If a feature consistently demonstrates a higher importance score in the real dataset when compared to its shadow counterparts, Boruta categorizes it as significant, referring to it as a ‘hit’. To enhance reliability, in this study, the algorithm was repeated 200 times, thereby mitigating the influence of random variations and bolstering confidence in the identification of important features.

Ultimately, the algorithm furnishes a normalized list of the most important features in the dataset, based on their consistency in outperforming their shadow counterparts. These identified features are deemed relevant and essential for explaining and predicting the variable of interest in the model. Specifically, the results provide statistical measures, including the median, mean, minimum, and maximum z-scores or importance values. Additionally, the algorithm presents normHits, which can be interpreted as the relative frequency of instances in which a feature outperformed its shadow counterpart in random forest runs (i.e., 200 runs), essentially indicating the likelihood of importance. The Boruta algorithm also delivers one of three decisions: confirmed, signifying that the feature in question is predictive; tentative, indicating that the feature is predictive, but the evidence is not yet sufficient; and rejected, implying that the feature does not account for much variability and may even be considered as noise.

In the context of this study’s analysis, which focuses on the relative ranking of variables both within and across the three models of the variables of interest, attention will be directed toward the mean importance index, normHits, and the decision. These values will be analyzed by variable and also by variable type (i.e., social, linguistic, diachronic, and stylistic) to enhance our understanding of EngPH morphosyntactic variation.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Bayesian Models

Statistical models are only as good as the predictions they make, so before delving into the statistical models’ findings, it is imperative to assess their predictive capabilities. To achieve this, I employed these three models to predict variants/outcomes using the ‘test’ datasets that had been set aside earlier, datasets that the models had not been exposed to previously. On average, the models demonstrated a commendable accuracy rate of approximately 70% in predicting outcomes or variants (Table 3 and Table 4). This represents a notable enhancement over the 50% accuracy expected by chance alone. Furthermore, when comparing the accuracy of the models for past tense morphology and past subjunctive to the no information rate (NIR), which signifies the accuracy of a model devoid of the discussed factors, the models significantly outperformed the baseline (McNemar’s test p < 0.0001). The existence of a significant correlation (ρ) between the actual responses and the predicted responses across all three models (Table 4, last column) underscores the adequate explanatory power inherent in the models developed within this study.

Table 3.

Confusion matrices.

Table 4.

Evaluation of models.

4.2. Variation in Past Tense Morphology

What factors influence the choice between -t and -ed use as past tense markers for select verbs (e.g., burn, leap)? The Bayesian model for past tense morphology indicates a high degree of certainty that linguistic factors account for some of the variation. First, the form of the verb lexeme in the utterance can reliably predict of the morphological variant used (pd = 1), as documented in Hundt (2001, p. 742). Second, it was also found that lexemes with adjectival functions (see example 1) showed a higher likelihood of attracting -t forms over -ed forms in comparison to lexemes with verbal functions (see example 2) (pd = 1).

- (1)

- Anybody notice the burnt area in SRP across seaside?

- <COPE-TW-CEB-2018-04:198424>

- (2)

- don’t get burned twice by the same flame.

- <COPE-TW-LUC-2016-03:219598>

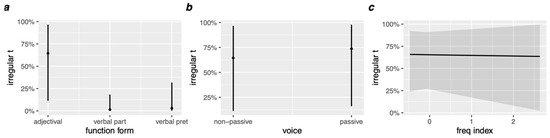

Third, passive constructions in EngPH tend to favor the -t form over the -ed form (pd = 0.96), and fourth, the results provide no evidence to support the notion that the frequency of a lexeme influences past tense morphology in EngPH (Figure 2 and Table 5) (pd = 0.51). Irrespective of a lexeme’s frequency, the proportion of -t to -ed usage remained consistent. Finally, there was strong evidence for the effect of verb lexeme: certain verbs like burn and leap were more likely to attract the -t suffix whereas verbs like spoil attract -ed (pd = 1).

Figure 2.

Marginal effects of intralinguistic factors on likelihood to use irregular verb form -t over -ed for selected verbs ((a) = function of verb, (b) = voice, (c) = frequency index, (d) = lexeme of the verb).

Table 5.

Bayesian model posterior draw estimates for predictors influencing likelihood to use -t over -ed (n = 14,217; post-warm-up draws = 20,000) Reference levels in boldface.

The findings related to linguistic factors provide partial support for the existing literature. While some findings, such as those concerning function and voice, align with the established research, others either partially confirm it or present discrepancies. For instance, the literature typically indicates that preterite or simple past verbs tend to favor the -ed form, but in my dataset, they show a preference for the -t form. Similarly, with participle forms, the literature suggests a preference for the -t form, but in this study, the -ed form is more common for participle forms. Another instance of disparities can be observed in the relationship between word frequency and past tense morphological variation. Existing studies indicate that more frequently used lexemes, such as learn, tend to favor the -t form, while less common ones, like leap, tend to prefer the -ed form (Bybee 2006; Peters et al. 2022). However, our current analysis does not provide evidence for such a pattern.

One potential explanation for these mismatches could be regional differences. The literature’s patterns are primarily derived from “Inner Circle” countries like Australia, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, whereas our data come from the Philippines (Kachru 1990, p. 3). Additionally, differences in time periods and text styles may also contribute to these discrepancies. Our data span from the 2010s and 2020s and consist of Twitter-style texts, while previous studies have sampled text from the 1850s to the 2020s from various corpora. Given the variations in geographical region, historical time frames, and text styles, it is not surprising to observe differences in linguistic patterns.

Nevertheless, despite these differences in datasets, some common patterns have emerged, indicating potential universal tendencies among different English varieties. However, the variability suggests that Filipino innovations and Twitter-specific language patterns may also exist. This is not unexpected, as variations and innovations often occur in computer-mediated communication for various reasons (Bohmann 2016), such as the density and type of social networks and the desire to sound ‘cool’ to a specific audience (Bell 2002; Milroy and Milroy 1985). The presence of English innovations in the Philippines is also understandable, given that this variety has achieved a significant degree of linguistic independence from its English parent, American English.

In addition to linguistic factors, the study also uncovered the influence of social, diachronic, and stylistic factors. Specifically, it revealed that geographical location exerts an influence on the -ed/-t morphological alternation. That is, even after controlling for and accounting for all the variables included in the model (e.g., diachronic, linguistic, and stylistic) factors using a holistic regression approach, the effect of geographical island group remains, suggesting that geographical location may indeed play some role in past tense morphological variation.

There is observable evidence of morphosyntactic variation across different macro-regions, where the Visayas island group exhibits higher rates of -t usage compared to the Luzon and Mindanao groups (pd = 0.93), with Luzon slightly surpassing Mindanao in -t usage (pd = 0.82). When examined from a geospatial perspective, these data demonstrate a central–peripheral pattern, with residents of Central Philippines, such as Cebu or Iloilo, showing a greater preference for the more ‘conservative’ -t suffix, in contrast to residents of Northern regions (e.g., Manila) and Southern Philippines (e.g., Davao), who tend to favor the regular -ed form.

I argue that this central–peripheral pattern is at least partially associated with the belief that those in Central Philippines, particularly the Visayas, use a ‘higher quality’ of English. This sentiment appears to be shared by both Visayans and non-Visayans and is also prominently conveyed and sustained in the media (Birondo 2006). Excerpts can be found below.

- (3)

- There’s one key here which I’m scared to say because Manila will get mad at me. You speak English here [Cebu]. And you speak better English here than any other provinces in the country. Romulo, 2006. The Philippine Star.

- (4)

- Why do some people think Visayas people in the Philippines have more knowledge in English than other Philippines areas? Quora.

- (5)

- Why are Cebuanos good in English? Quora.

- (6)

- I’ve heard of that stereotype… Julius from Cebu, 2020, Quora.

The ideology appears to have multiple underlying reasons. According to comments from the online forum Quora regarding ‘better English’ in the Philippines, Filipino outsiders assert that Visayan/Central speakers exhibit superior English because many Visayans hold professions, such as seamen, that demand a high level of English proficiency.

- (7)

- Pinas merchant marine is controlled by Cebuanos or Ilonggos. And seamanship requires a working knowledge of English… Raul Montino from Caramines Sur, 2020, Quora.

Some argue that the deliberate avoidance of Northern or Tagalog influences, along with negative attitudes toward Northern residents, especially Tagalog speakers, have driven those in the center to favor English. Many consider English a preferable alternative to Tagalog.

- (8)

- Also, Tagalog or Pilipino is internal colonization. So most non-Tagalogs would rather set aside Tagalog or Pilipino and go for English. Raul Montino from Caramines Sur, 2020, Quora.

- (9)

- They preferred to struggle in broken English in talking to me than speak Tagalog. They said it was easier to converse with me because most Manilenos insist on Tagalog, which is just as difficult as English to them. But even if they struggled in English, they felt less insulted because of their past bad experience with arrogant Manilenos who imposed Tagalog on them. Josh 2020, Quora.

- (10)

- most Cebuanos avoid using the national language Filipino (Tagalog-derived) as they prefer speaking in their own native Cebuano dialect, or English. Jason from Davao 2019, Quora.

- (11)

- most of the Cebuano and Bisaya aren’t good at Tagalog because of their accent. … they are more comfortable talking in English than Tagalog especially to non-Visayan people because of their accent and English is much easier to converse for them than Tagalog. Jerseld 2023, Quora.

Another group of outsiders believes that Central Philippines residents have better English because it is associated with the upper class, primarily due to the migration of upper-class, English-speaking individuals from Central Philippines to other parts of the country.

- (12)

- It’s because most Cebuanos in Manila are members of Manila High Society and Spanish Mestizas... A lot of middle class Visayans have migrated to Manila reaching as far as Cavite. They have an upper class … accent and they don’t speak Tagalog. … in Cebu, English is the language of the upper class. And in the past, most Visayans in Manila came from Cebu. Josh 2020, Quora.

On the contrary, those from the Central region argue that they possess better English due to their more amicable relationships with Americans compared to non-Visayans, leading to a more deliberate preservation of English.

- (13)

- Cebuano culture retains a far stronger affinity for … American culture than Tagalog culture, due to various historical reasons, primarily that Cebu was relatively peaceful and stable under…. American administration (as an industrial base, without US military presence), which created far more positive perceptions on … American culture. Thus, we Cebuanos consider … American culture as part of our culture, and we will prefer to speak English, if not in Cebuano… Serena from Cebu, 2020, Quora.

Given that language ideologies significantly shape language behavior, this ‘better English’ ideology can encourage a more conservative or less innovative or regularized use of English. Similar to cases observed worldwide, such as the purist language ideology among Lánnang-uè speakers in Manila (Gonzales 2021, 2022b, 2023b), speakers may strive to maintain the image of being a ‘better English’ speaker and thus incorporate more conservative language features.

With respect to city-level variation, the study found no significant differences in the use of -ed/-t between Manila and other Philippine cities as a whole. The results so far provide some support to what has historically been claimed for EngPH: that the dialectal variation within the variety is minimal (Llamzon 1969). Despite the salient cultural differences between Manila and other Philippine cities, such as the use of Tagalog, increased economic activities and capital, the perception of it being more ‘urban’ and ‘standard’ (as opposed to being ‘rural’, or ‘provincial’), and it being the capital of the nation (see example 14), the rates of past tense morphology use appears to be similar between speakers of Manila versus speakers of other cities. It is impossible to comment on Llamzon’s claim without further evidence, but if this pattern is observed in other variables, then we can indeed say something about dialectal variation being less salient at the Manila vs. non-Manila axis.

- (14)

- Generally speaking, people in the city [Manila] have better jobs and by extension, more money. Because of this, the person from the city is likely to be richer, statistically speaking… the accent in the city is considered the “neutral” accent, while the rest of the accents are considered “regional”…. Unfortunately for the people who are far from Metro Manila, the Big 4 is concentrated in the capital. Many of the most elite high schools are also in Metro Manila… Because of this, someone who is at the very top of the social pyramid is more likely to be from Metro Manila. Steven, 2016, Quora.

From a diachronic perspective, the data show that the -t form has increased in popularity over the span of a decade, confirming observations in previous work on EngPH (Borlongan 2011; Gonzales 2023a).

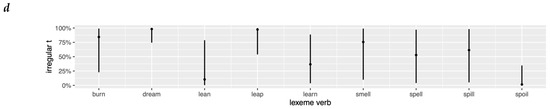

The notion that Philippine English (EngPH) is ‘monostylistic’ (Lee and Borlongan 2022; Llamzon 1969) seems to be unfounded based on the findings of this study, which indicate that stylistic context has an impact on the choice of variant; the -t form is associated with informality and the nature of being interpersonal whereas the -ed form is associated with formality and informationality. From the perspective of social constructionism and third-wave variationism (Eckert 1999, 2012), the effect of the stylistic variables and the variables’ relatively high rates of importance in explaining variation, as indicated in the high levels of importance in Table 6 and Figure 3, suggest that these -t and -ed are potentially being used as stylistic resources in expressing meanings related to formality and informationality.

Table 6.

Feature importance by variable and by variable type, results of the Boruta algorithm (past tense morphology model).

Figure 3.

Feature importance plot (past tense morphology model).

When we compare the magnitude of standardized effects for all the factors using a unified approach, as represented by the Boruta algorithm mean and median scores and normHits in Table 6 and Figure 3, it becomes evident that linguistic factors exert a significantly more substantial influence on variation compared to diachronic, stylistic, and social factors. In the context of social factors, specifically geographical factors, while they do have some impact on variation, as witnessed in the central–periphery pattern discussed earlier, they do not appear to be crucial in determining the variation in past tense morphology. The influence of social factors is relatively minor in comparison to other factors, suggesting that the geographical social meanings associated with geography are perhaps not highly activated in this particular variable. If geographical factors were of paramount importance, we would anticipate more pronounced effects or distinctions between regions, especially if -ed were considered a marker of Luzon and Mindanao identity, given that stylistic variation typically aligns with social variation (Bell 1984).

Furthermore, stylistic factors related to individual communication styles also do not seem to play a substantial role in past tense marking variation, implying a high level of consistency in how individuals within the EngPH speech community use this variable. In a broader context, it can be argued that linguistic factors generally outweigh stylistic factors, which in turn are more influential than diachronic factors, and these, in turn, hold more weight than social factors.

4.3. Variation in the Comparison of Adjectives

The choice of comparative marking is also not immune to the pressures of linguistic, stylistic, diachronic, and social factors (Table 7). Concerning social factors, there appears to be an influence of geographical region on comparative marking in EngPH. The southernmost island cluster of Mindanao exhibited the highest incidence of innovative double comparative usage, followed by Visayas and then Luzon, forming a discernible Mindanao > Visayas > Luzon pattern (Figure 4a) (pd = 0.97). This trend mirrors a previously identified north–south continuum observed in phrasal verb variation research (Gonzales 2023a). The existence of such sociolinguistic patterns suggests potential significance or indexical meaning associated with the concepts of “north” and “south”, indicating that language plays a role in their construction. This proposition is not unfounded, considering the prominent north–south contrast in Filipino consciousness, as reflected in blog posts discussing distinctions in the Philippines. According to Filipino writers (examples 15 and 16), individuals from the north tend to be more conservative, while those from the south are perceived as more “creative” or innovative. Given the intricate connection between language and ideologies (Dong 2009; Irvine and Gal 2000), especially ethnolinguistic ideologies and actual language, it is reasonable to suggest that the observed north–south linguistic continuum may be linked to the prevalent north–south ideology among Filipinos. This relationship could manifest, for instance, in northerners employing more conservative linguistic variants such as single comparatives to embody the conservatism attributed to them, while southerners may use more innovative and playful variants like double comparatives to align with the playful persona associated with them due to strong north–south ideologies.

Table 7.

Bayesian model posterior draw estimates for predictors influencing likelihood to use double comparatives (n = 66,758; post-warm-up draws = 20,000). Reference levels in boldface.

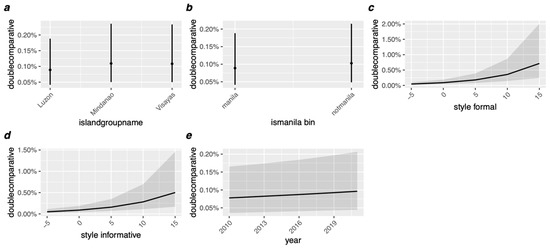

Figure 4.

Marginal effects of stylistic and extralinguistic factors on likelihood to use double comparatives ((a) = island group, (b) = city (Manila vs. non-Manila, (c) = style (informal—formal), (d) = style (interpersonal—informative), (e) = Year).

- (15)

- The “Visayans” of Central Philippines are considered to be more “jolly, straightforward, jokesters, outgoing, talkative and generally friendly towards strangers... However this is not considered to be “normal” in Luzon… and the further north you go, the more “conservative, silent, aloof and serious” people tend to be... We in Metro Manila may not be as “jolly” as the Visayans, but we are also not as “uptight” as those in the far north … Dayang, 2020, Quora

- (16)

- Southern ethnic groups such as Visayans are more pleasant. They’re friendly, creative, and easy to be with.. Warays are laid-back (but can be fierce at times). Northern ethnic groups, on the other hand, are more conservative. Ilocanos are spendthrifts and hardworking. Kapampangans are very fashion and food conscious and resent losing face much more than other Filipino ethnic groups. Tagalogs are viewed by others as being overly concerned with speed, rude, and standoffish (probably connected with their area being the seat of the capital). Bicolanos are natural stoics. Igorots are proud of their culture and won’t easily give way to an outsider. David, 2022, Quora

At levels beyond the macro-region, specifically at the city level, there is a notable likelihood of a non-zero impact of ‘city’ on the selection of comparative marking strategies. Residents of Manila exhibit a preference for the standardized single comparative variant, whereas those residing outside Manila tend to favor the innovative double comparative variant (Figure 4b) (pd = 0.86). The higher prevalence of standardized language usage among Manila residents is to be expected, considering Manila’s role as the perceived standard language bearer and the capital of the Philippines. The national language heavily draws from the Tagalog variety spoken in Manila. Additionally, Manila is home to leading educational institutions that use English as the medium of instruction, and it is perceived as being highly proficient and ‘fluent’ in English (see example 17). Hence, the presence of sociolinguistic variation in the choice of standard/non-standard comparative marking along the Manila/non-Manila axis is unsurprising. What is interesting, however, is the effect of city on comparative marking but not past tense morphology. For the past tense morphology variable, no significant linguistic differences are evident between residents of Manila—the political center of the Philippines—and those living outside it. The discrepancy suggests that, for certain variables, the core–periphery pattern in EngPH may be defined geographically rather than politically, whereas in others it could be defined both geographically and politically.

- (17)

- most people in Manila can speak English… since Manila is the economic capital, many international economic transactions are done here. Most of the airline personnel, bank tellers, entrepreneurs, hotel staff, government employees, office workers, salespeople and students can speak in fluent English, while blue collar workers and the lower classes can still speak decent English, enough to be understood by a native speaker. Currently, Manila ranked second on the most sought after cities for BPO companies according to Tholons International. Thanks to the fluency of Manileños in English. Allan, 2019, Cavite, Quora

The presence of sociolinguistic patterns related to Manila-non-Manila and North-South distinctions, in addition to the center–periphery patterns discussed earlier, suggests a multi-layered portrayal of sociolinguistic dynamics in the Philippines. This indicates that these diverse dynamics can coexist within a single space, giving rise to multiple and intricate interpretations such as ‘proper’, ‘conservative’, ‘Northern’, ‘central’, and ‘Manileño’.

Diachronically, the results show that the use of comparative marking has increased in the past decade (pd = 0.92), but the popular variant continues to be the standardized single comparative. It is also worth mentioning that the changes in the distribution of variants across the 2010s and early 2020s is insignificant (Figure 4e). The finding suggests that there is some degree of stabilization during this time period.

In addition to geographical and diachronic factors, the way in which something is said (i.e., stylistic context) also plays a significant role in shaping the choice of comparative construction. The degree of informationality (pd = 1) and formality (pd = 1) both impact the use of comparative constructions (Figure 4c,d), such that informational and formal tweets are more likely to attract double comparatives. This is at odds with what I expected, (1) because EngPH has often been assumed to be monostylistic (Llamzon 1969; McKaughan 1993), and (2) because although the double comparison construction has been traditionally associated with “high style and formal registers” in some varieties of English (González-Díaz 2004, p. 91), in EngPH, this should not be the case, as an examination of data in prior work (Borlongan 2011) has shown that double comparatives in EngPH are never found in utterances with formal style (examples 3 and 4).

- (18)

- So we’ll just let it simmer for a minute or a minute-and-a-half tapos [‘then’] we ’ll add in our uh one-fourth bar of melt cheese to make it more creamier okay

- <ICE-PHI:S2A-055#98:3:A>

- (19)

- It’s more cheaper … that’s a reality I’m not joking

- <ICE-PHI:S1A-022#111:1:A>

One possible explanation is that there may be changes happening in EngPH, where the double comparative is becoming more formal (as evidenced in a comparison of 1990s and 2020s data) (Borlongan 2011). Another explanation could be that the stylistic meaning of double comparatives varies depending on the platform of communication, with double comparatives being formal on Twitter but informal in other ‘traditional’ contexts. More research is needed to confirm these findings. If the findings are verified, this study may be one of the first to show that the way formality affects language variation in EngPH varies depending on the platform of communication.

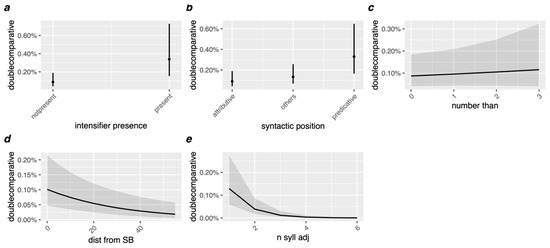

Once again, linguistic factors emerge as influential predictors of variation in comparative constructions (Figure 5). Utterances featuring an adjective preceded by a pre-modifying intensifier tend to favor the usage of double comparative marking (pd = 1), which aligns with findings from previous research (González-Díaz 2004). This study further confirms that syntactic position (pd = 1), proximity to sentence boundaries (pd = 1), and adjective length (pd = 1) indeed impact comparative marking. Moreover, it goes beyond previous research by demonstrating that these factors primarily influence the choice between single and double comparatives. Notably, this research is among the first to reveal that the double comparative is more likely to be favored when it appears after the noun it modifies, in the predicative position (e.g., The apple is more cheaper vs. the more cheaper apple). Additionally, it is the first study to show that the double comparative is preferred when it is in closer proximity to a sentence boundary and when the adjective is shorter in length. These findings contribute to our understanding of the significant structural factors that play a role in explaining and predicting comparative marking strategies.

Figure 5.

Marginal effects of intralinguistic factors on likelihood to use double comparatives ((a) = presence of pre-modifying intensifier, (b) = syntactic position, (c) = number of comparisons, (d) = distance from sentence boundary, (e) = number of syllables in the adjective).

One intriguing discovery is the absence of evidence indicating a positive correlation between the number of comparisons and the likelihood of using a double comparative construction. Irrespective of the quantity of items being compared, the frequency of ‘redundant’ or innovative comparative marking is consistent.

Examining the random effects, it becomes apparent that the part-of-speech of the words preceding and following the adjective, as well as the specific adjective used, exert influence over the choice of comparative marking strategy (pd = 1). For instance, adjectives that are preceded by nouns and pronouns, as well as those followed by conjunctions, tend to attract double comparative marking. Furthermore, the double comparative construction is favored in contexts involving adjectives such as weak, wild, and ugly.

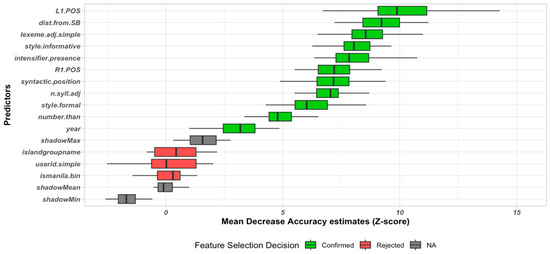

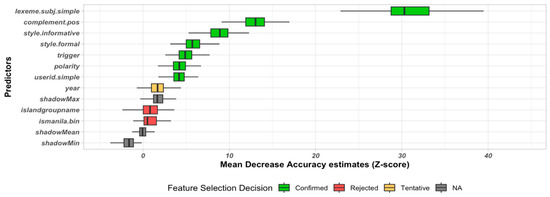

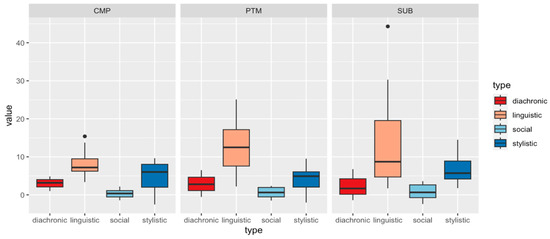

The Boruta analysis reveals that linguistic factors have, yet again, a significantly more substantial impact on variation in comparative marking compared to diachronic, stylistic, and social factors. This is evidenced in the mean and median scores and normHits in Table 8 and Figure 6. While geographical factors, specifically the north–south and Manila vs. non-Manila patterns, do contribute to some variation, their influence appears to be relatively minor in determining comparative marking variation. The findings suggest that social meanings associated with geography might not be highly activated in this specific variable. Moreover, stylistic factors related to individual communication styles show limited influence, indicating a high level of consistency within the EngPH speech community. Generally, similar to what I observed for past tense morphology, linguistic factors outweigh stylistic factors, which, in turn, are more influential than diachronic factors, and these, in turn, hold more weight than social factors, specifically concerning geography.

Table 8.

Feature importance by variable and by variable type, results of the Boruta algorithm (comparison marking model).

Figure 6.

Feature importance plot (comparison marking model).

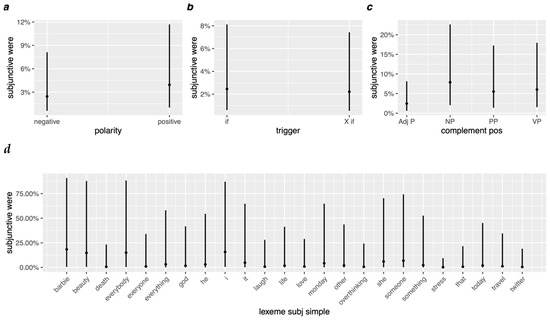

4.4. Variation in the Past Subjunctive

The outcomes of this investigation demonstrate that previously identified linguistic factors do, indeed, impact the variations observed in past subjunctives (Figure 7 and Table 9). These factors include polarity, adverbial triggers, and the specific type of complement within the verb phrase. Instances featuring positive polarity (pd = 0.97) exhibit a tendency to utilize the were variant, while negative polarity tends to evoke the was variant. This discovery appears to challenge the existing literature, which commonly associates the was variant with positive expressions. However, it is crucial to note that prior research has predominantly focused on was/were in specific contexts (e.g., the United States, and the United Kingdom). Therefore, the observed deviation here should not be entirely unexpected, as EngPH diverges from other English varieties, such as its parent American English, due to various sociohistorical factors (Borlongan 2016). These factors include the emergence of a national identity, the ratification and implementation of two inequitable Acts from the Americans designed to aid in the post-war rehabilitation of the Philippines, and several other incidents contributing to the Philippines’ sense of separation from the United States (Borlongan 2016). The Philippines has also independently formulated its language policies without external control. There is a general acceptance of an emerging local norm, although residual linguistic conservatism persists. Given the Philippines’ independence and the growing inclination to orient itself endonormatively rather than exonormatively in relation to the United States, it would not be surprising to observe deviations in the patterns of EngPH was/were usage from the ‘standard’ American norms. If this holds true, the results would also imply that within the context of the Philippine Twitterscape, was/were may take on different activated indexical meanings, where the subjunctive was indexes negative meaning, whereas the subjunctive were indexes positivity. Although social variation appears to be relatively substantial, it remains unclear whether this variable is being employed as a resource for its positive and negative meanings. Further research is necessary to determine if this is indeed the case.

Figure 7.

Marginal effects of intralinguistic factors on likelihood to use subjunctive were ((a) = polarity, (b) = trigger (if vs. X if), (c) = complement, (d) = subject lexeme).

Table 9.

Bayesian model posterior draw estimates for predictors influencing likelihood to use subjunctive were (n = 3488; post-warm-up draws = 30,000); tokens involving existential there (e.g., if there were such losses), pseudo-subjunctives (i.e., if in the ‘whether’ sense), and plural subjects (e.g., if we were) were excluded. Reference levels in boldface.

Furthermore, the choice of adverbial trigger also influences the selection of was or were in past subjunctives (pd = 0.8). Constructions featuring a plain if (e.g., if I were) are more likely to employ the were variant compared to constructions utilizing other if structures (e.g., as if, but if, even if, for if). The study also sheds light on the significance of the complement within the verb phrase when explaining variation. Verb phrases with noun phrase complements (e.g., if I were a boy) tend to favor the were variant the most (pd = 1), followed by verb phrase complements (e.g., if I were going to school), prepositional complements (e.g., if I were on the way) (pd = 0.92), and finally, adjective phrase complements (e.g., if I were beautiful) (pd = 1). In summary, the results affirm the presence of effects related to adverbial triggers and complement types on subjunctives in general. However, this study takes a step further by clarifying the direction of the effect on the was/were variation in past subjunctives. This adds depth to our current understanding of sociolinguistic variation.

An analysis of the variation based on grammatical subjects reveals distinct trends. Utterances with subjects like I, someone, everybody, and beauty tend to favor the use of the were form, while utterances featuring subjects such as stress, death, Twitter, God, and everyone tend to prefer was (pd = 1). Further examination of these utterances and their subjects suggests that the were variant appears to be more common with animate subjects, whereas the was variant tends to be associated with inanimate objects. Additional analyses can be carried out to explore how the animacy of the subject influences was/were variation.

Beyond linguistic considerations, factors such as stylistic context and diachronic factors have also been found to influence variation patterns (Figure 8). Speakers tend to employ the subjunctive were in utterances styled as informational (pd = 1). Furthermore, when comparing speakers from the 2020s to those in the 2010s, it becomes evident that the indicative was is favored more in the former decade (pd = 0.8). These findings only partially align with Collins’ (2014) research on Philippine English, where diachronic factors were the sole significant factors influencing this choice, rather than genre or style.

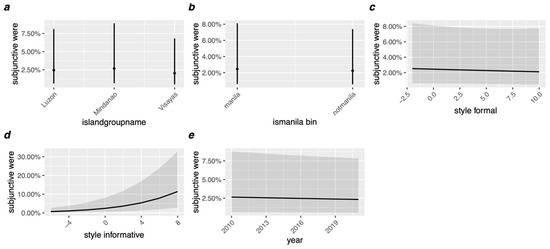

Figure 8.

Marginal effects of extralinguistic factors on likelihood to use subjunctive were ((a) = island group, (b) = city (Manila vs. non-Manila, (c) = style (informal—formal), (d) = style (interpersonal—informative), (e) = Year).

Another significant determinant in the choice between was and were is the geographical region, specifically focusing on the island group and residence in Manila. After factoring in all other considerations, the model outcomes reveal that the Visayas island group is prominent in using was (illustrated in example 20, Bacolod City in Visayas) (pd = 1). In contrast, both Luzon and Mindanao exhibit higher rates of subjunctive were usage compared to Visayas (as seen in example 21, Tuguegarao City in Luzon), confirming earlier observations on this phenomenon (Gonzales 2023a).

- (20)

- If i was u, i wanna be me…, too

- <COPE-TW-BAC-2017-07:163023>

- (21)

- if I were you, I’d be offended din talaga hahaha…

- <COPE-TW-TUG-2016-06:141853>

The findings related to the island group echo the general core–periphery pattern identified in the earlier sections of this paper, where users in the Central Philippines (Visayas) tend to favor the non-standardized was variant more than their counterparts in surrounding islands (Luzon and Mindanao). Notably, this core–periphery pattern aligns with the pattern linked to past tense morphology discussed previously, but with a key distinction in the direction of the effect. Unlike the past tense morphology variable, where speakers at the center prefer the conservative standard variant, in the was/were variable, speakers at the center seem to adopt the innovative variant was, even when the subjunctive mood requires the use of were. I argue that this discrepancy may be attributed to perceived or salient standards, specifically the idea of endonormative standards in EngPH (Borlongan 2016; Schneider 2003).

While standard English dictates the use of the were variant to express the subjunctive mood, regardless of subject plurality, in the Philippines, it appears that the plurality constraint in English (i.e., the use of was for singular subjects) takes precedence over the subjunctive constraint—a norm in EngPH. Interviews with EngPH speakers provide evidence of this, where, for conditional utterances with singular subjects and subjunctive mood, some explicitly state that the was variant is ‘correct’, while the were variant is ‘wrong’, citing the plurality rule (2022, author’s ethnographic notes). From a local perspective, the standard or conservative variant might indeed be was rather than were. If this were the case, it would support the argument that Central Philippines exhibits conservativity through the use of the conservative was, aligning with the ‘better English’ ideology discussed earlier.

In summary, in conjunction with the findings related to comparative markers, these results emphasize the intricate nature of the EngPH sociolinguistic system. In the context of comparative markers, residents of Southern Philippines seem to predominantly use conservative variants, whereas in this analysis and the analysis on past tense morphology, it is argued that residents of Central Philippines (and Manila) are the most conservative. These patterns underscore the layered realities of EngPH, emphasizing the importance of considering regional variables in sociolinguistic analyses, as they shed light on variation in specific EngPH patterns.

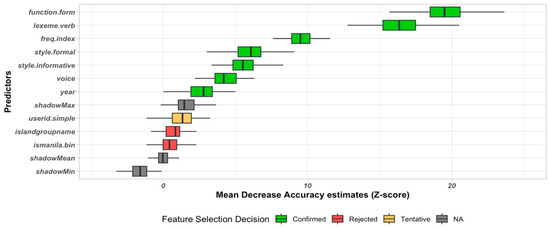

Nevertheless, when these social factors are compared with other considerations, it becomes evident that the effects observed for social factors are overshadowed by the effects observed for linguistic, stylistic, and diachronic factors (Table 10 and Figure 9). Despite indications of social and geographical effects mirroring existing linguistic ideologies, these factors do not seem to be as robust compared to linguistic, stylistic, or diachronic factors when explaining and predicting variation. However, as mentioned earlier, other social factors, aside from geographic factors, such as perceived proficiency in English or socio-economic status, might prove more useful in conditioning the variation between was and were for conditional utterances in the subjunctive mood.

Table 10.

Feature importance by variable and by variable type, results of the Boruta algorithm (was/were model).

Figure 9.

Feature importance plot (was/were model).

5. General Discussion

This current investigation revisits three linguistic variables acknowledged for exhibiting extensive variation, wherein earlier findings might have been distorted due to insufficient consideration of well-established and robust social, diachronic, linguistic, and stylistic factors, as elaborated in prior discussions. These variables include:

- The use of -t and -ed past tense morphology (e.g., burnt vs. burned).

- The use of single or double comparison marking (e.g., happier vs. more happier).

- The selection of was or were in past subjunctives with singular subjects (e.g., If I was/were happy)

Unlike previous studies that only considered a reduced (exclusive) set of factors, I sought to expand on prior research by integrating established social, stylistic, linguistic, and diachronic factors into unified analysis of EngPH morphosyntactic variation, testing the extent to which observations made in prior work corroborate the results here and are empirically grounded and not distorted. For example, I sought to assess whether the stylistic, diachronic, and social factors identified in previous research are trustworthy when considered alongside linguistic factors. The solution proposed was a comprehensive four-pronged ‘holistic’ approach (encompassing social, stylistic, linguistic, and diachronic aspects) to enhance the understanding and emerging theorization of (EngPH) variation while minimizing potential biases and challenging the predominantly deterministic and monolithic approach dominant in the field. I focus on morphosyntactic variation within Twitter-style English as used in the Philippines (EngPH), drawing upon the Twitter Corpus of Philippine Englishes (TCOPE).

Two statistical techniques were deployed to gain a more nuanced and less distorted understanding of EngPH variation: Bayesian regression modeling and Boruta feature selection algorithm with random forests modeling. In contrast with previous work, a holistic range of factors from different dimensions, particularly social, linguistic, diachronic, stylistic dimensions, were simultaneously included in both modeling procedures under a unified analysis that takes into account the effects of all factors in the model during analysis.

Through an examination of predictor pd values across types of variables (e.g., diachronic, social) under the Bayesian framework, it is evident that these factors generally condition variation in EngPH morphosyntax. Most of the effects observed in the prior literature did not disappear even after taking into account the effects of other known and robust variables, illustrating some congruence between a non-unified analysis (see Section 2) and a unified analysis. However, it is important to note that there were also some visible mismatches between the unified regression analysis made in this study, and prior studies that focused exclusively on these variables in isolation. For example, the results show that we actually have very little evidence of the effect of city described in Gonzales’ (2023a) work and frequency effects on past tense morphology in Bybee (2006) and Peters et al.’s (2022) works, and very small evidence of stylistic formality on the was/were alternation for conditional utterances containing singular subjects with subjunctive mood described in Skevis (2014) and Waller’s (2017) works. The observed mismatch between unified and non-unified approaches stresses the importance of including all known variables in a single analysis like the regression analysis conducted here, as the effects of certain variables fall into the background in light of other factors, or rather, our confidence of certain variables having an effect on variation falls in light of other more plausible variables.

The advantages of employing a unified approach are also evident in the Boruta analyses conducted in this study, wherein factors from the four types were incorporated into a singular model for standardized importance ranking and classification. Upon scrutinizing the mean, median z-scores, normHits, and decision values, a consistent pattern emerged across all three variables of interest (past tense morphology, comparison marking, was/were). It was observed that linguistic factors typically take precedence over stylistic factors, and these, in turn, surpass diachronic factors, which hold greater influence than social factors.