Abstract

Broadly speaking, binominal and biverbal lexical constructions have been studied independently in different research traditions and frameworks. It is true that the two do not necessarily have overlapping areal distributions, but the fundamental question remains whether Indo-European NN compounds and Transeurasian VV compounds have nothing in common. Against this background, a cross-categorial comparison, not within but across languages, is made of coordinative binominal and biverbal constructions. NN and VV coordinate compounds from English and Japanese are examined in detail using the methodology of contrastive morphology and decompositional lexical semantics. It is shown that dvandva is possible not only in NN but also in VV coordinate compounds and, furthermore, that the dvandva–appositive distinction in NN coordinate compounds recurs in VV coordinate compounds. Cross-categorial formal analyses of the two types, i.e., dvandva and appositive, are presented in the Lexical Semantic Framework.

1. Introduction

Compounding is one of the central topics in the study of word formation. Generally, compounds are classified according to the syntactic category or word class of their components and the entire construction; the internal syntax, semantics, and headedness of the entire construction; and the formal makeup of their components. In the work of Scalise and Bisetto (2009), the three fundamental grammatical relationships, subordination or head-complement relationship, modification, and coordination, constitute a parameter of their classification of Germanic and Romance compound nouns:

Coordinate compounding, the topic of this paper, is the case of compounding in which same-category lexemes are asyndetically coordinated and morphologically realized in an identical form type. In the following English examples (cited from Bauer 2008; Scalise and Bisetto 2009), two nouns occur in a relationship that is connected by the conjunction and in the uncompounded condition:

The division between (2) and (3) has been a topic of considerable interest in recent decades. Thanks to the concerted efforts of morphologists and typologists (ten Hacken 1994; Olsen 2001; Wälchli 2005; Bauer 2008, 2010a, 2017; Renner 2008; Arcodia et al. 2010; Ralli 2013, 2019; Shimada 2013), it is now widely accepted that the internal syntax and semantics of coordinate compounds is not monolithic. Specifically, (2) represents appositive coordination, which coordinates semi-permanent states of a single individual, whereas (3) represents dvandvas, a type of coordinate compound that typically describes a whole composed of the parts named by their components. While English uses the same conjunctive coordinator regardless of the type of conjunctive semantics (Hoeksema 1988), Japanese uses different conjunctions, de ‘and’ for apposition and to ‘and’ for set formation or collectivization. Thus, the phrasal translations of the compounds in (2, 3), if given in Japanese, will contain de and to, respectively, as in (2a) singer-songwriter = ‘singaa de songuraitaa’ vs. (3b) Austria-Hungary = ‘oosutoria to hangarii’.

| (1) | a. | Subordination | e.g., taxi driver, brain death |

| b. | Modification | e.g., ghostwriter, blackboard | |

| c. | Coordination | e.g., singer-songwriter, mind-brain |

| (2) | a. | singer-songwriter |

| ‘someone who is a singer and songwriter’ | ||

| b. | actor-author | |

| ‘someone who is an actor and author’ |

| (3) | a. | mind-brain |

| ‘the philosophical and physiological aspects of cognitive processes considered as a causally interrelated entity’ <Philosophy> | ||

| b. | Austro-Hungary, Austria-Hungary | |

| ‘the dual monarchy established in 1867 by the Austrian emperor Franz Josef, according to which Austria and Hungary became autonomous states under a common sovereign’ |

The headedness of these constructions is another matter of ongoing scholarly debate (the references cited above; also, Scalise et al. 2009; Bauer 2010b, 2022; Bagasheva 2012; Pepper 2016; Nóbrega and Panagiotidis 2020). The authors of Scalise and Bisetto (2009) are of the opinion that the appositive-dvandva division of NN coordinate compounds result from their second compounding parameter defined by headedness. In it, appositives are endocentric in the sense that one component is structurally dependent on the other, while dvandvas are exocentric in the sense that the combined components carry equal weight and neither of them is more prominent. Sanskrit grammar also treats appositive compounds as a type of endocentric compound called karmadhārayas, not as dvandvas. Usually, compounding produces a subcategory of the referent of the head component; thus, ten Hacken (1994, p. 74) defines H(eaded)-compounding as the construction of the structure [XY]Z or [YX]Z and of the following semantics: “the denotation of Z is a subset of the denotation of Y”. Significantly, appositive coordinate compounds are no exception to this definition. Thus, just as ghostwriter denotes a type of writer, singer-songwriter is a type of songwriter; the difference being that while someone called a ghostwriter is never a type of ghost, the latter allows such an alternative reading, i.e., singer-songwriter as denoting a type of singer. This suggests that appositive coordinate compounds and modificational compounds form a continuum.1 In contrast, dvandva coordinate compounds typically name a superordinate concept or superset that is composed of smaller subsets. As a result, the same test shows that this type is exocentric; for example, mind-brain is neither a type of mind nor a type of brain. The notion of double-headedness is avoided because it unnecessarily complicates the discussion. For example, Ceccagno and Basciano (2009) and Niinuma (2015) say that dvandvas are double-headed, while Naya and Ishida (2021) apply the concept to appositive compounds.

The formal aspect of coordinate compounding has not received much attention in the literature to date, but it is conceivable that coordination values not only the categorial and functional, but also the formal parallelism between the coordinates. For example, the components of taxi driver in (1a), a subordinate compound, differ from each other categorially, functionally, and formally. However, appositive coordinate compounds often, though not always, involve components of an identical form, such as the two agentive nominalizations in (2a, b). In English, form sameness in set formation coordination is observed in binomials (Kopaczyk and Sauer 2017); in this multi-word expression containing an overt conjunctive or disjunctive coordinator, the -ing form should coordinate with another -ing form, while an unmarked or citation form should coordinate with another unmarked or citation form: e.g., coming and going, come and go, *coming and go. Similarly, while going up and down and ascending and descending are each observed, their mixed usage is not. In dandva-based set formation coordination, coordinates can have identical inflections. Thus, in Mordvin, the binomial father and mother corresponds to a dvandva, which shows the following multiple plural exponence: t’et’a.t-ava.t (father.pl-mother.pl) ‘parents’ (Wälchli 2005, p. 137). According to Kiparsky (2010, p. 303), “Vedic dvandvas originated as combinations of two dual-inflected nouns”.

The purpose of this article is to introduce VV coordinate compounds into the NN-centered research landscape and to argue that they also divide along the appositive-dvandva distinction. VV coordinate compounds have received much less attention than NN or AA coordinate compounds, but as will be argued in this paper, they too contain dvandvas and appositive-like non-dvandvas. This proposition should not be confused with the broader perspective that VV compounds can be divided into the subordinate, modificational, and coordinate types, along the same lines as observed among NN compounds in (1a–c). For example, Nicholas and Joseph (2009) and Kiparsky (2009) argue for the SUB vs. COORD distinction among Modern Greek VV compounds. Ceccagno and Basciano (2009, pp. 480–82, 486) suggest that the verb + object type, the resultative type, and the serial-verb type of Mandarin Chinese compound verbs belong to the SUB type, while “two-headed” coordinate compounds include instantiations of the structure [V+V] v. In contrast to these previous studies, this article is concerned with the more delicate question of whether dvandvas are possible in VV coordinate compounding.

Since this is an empirical question, the methodology employed is a combination of descriptive and contrastive morphology, using basic morphological and conceptual semantic terms as defined in Bauer et al. (2013, chap. 2) and Cruse (2011), respectively. More specialized or language-specific terms will be defined as they are introduced. As a first hurdle, VV compounds are not good subjects of the “Z is a type of X/Y” headedness test; a conceptual system that is independent of syntactic category is required. To this end, we take advantage of a feature-based morphological theory that is developed in Lieber (2004) and subsequent publications and that is now called the Lexical Semantic Framework (LSF) (Lieber 2016a, 2016b). The data source is authoritative dictionaries and linguistic publications (books or journals); in some parts, sentences produced by introspection are necessary, but they are all double-checked by other native speakers.

The discussion proceeds as follows: in the next section, classic dvandvas are defined semasiologically and onomasiologically, and a prediction regarding VV compounding is advanced. In Section 3, data materials are generated, and two patterns are drawn from VV coordinate compounds using the same descriptive parameters as used in this section. Section 4 puts the prediction to the test by using the data and shows that dvandvas are possible in VV coordinate compounding. Without stopping here, the discussion goes on to observe that the non-dvandva VV compounds behave like appositive NN compounds and propose an entirely novel hypothesis: that the dvandva-appositive distinction is possible among VV coordinate compounds.2 Section 5 concludes the discussion. In short, the goal of this paper is to find a bridge between NN and VV compounds in one of the fundamental types of compounds. While its empirical scope is limited, it is written with the broader goal of contributing to emerging research projects encompassing binominal and biverbal lexical constructions (Lieber and Štekauer 2009; Bagasheva 2012; Bauer 2017).

2. Framework

2.1. Dvandva from a Semasiological Perspective

In Bauer (2008) and Arcodia et al. (2010), dvandvas are defined as a type of coordinate compound in which the components are parts/hyponyms and the entire construction is the whole/hypernym. In Bauer’s (2008) classification, the first type of dvandva is called additive and it refers to the collective set of members that are co-meronyms or converses. Converses are a subtype of opposites.3 Most English dvandvas, including those in (3), belong to this type. Given below are Japanese additive dvandvas cited from Yonekura et al. (2023, chap. 2). Hyphen-connected examples consist of freely occurring morphs, while the unconventional use of the word-internal equal sign captures those connecting bound morphs.

| (4) | a. | oya-ko | Additive |

| parent-child | |||

| ‘parent and child’ | |||

| b. | te-asi | ||

| hand-foot | |||

| ‘hands and feet, the limbs’ | |||

| c. | me-hana | ||

| eye-nose | |||

| ‘eyes and nose’ | |||

| d. | dan=zyo | ||

| man-woman | |||

| ‘man and woman’ | |||

| e. | huu=hu | ||

| husband-wife | |||

| ‘husband and wife’ | |||

| f. | zi=moku | ||

| ear-eye | |||

| ‘eyes and ears; one’s attention or notice’ | |||

As subtypes of the semantic relationship between binary opposites, Cruse (2011) distinguishes complementary, antonymic, reverse, and converse relationships (see note 3). Complementary or antonymic opposites produce the second type of dvandva called exocentric. For example, the Japanese dvandvas in (5a, c) combine pairs of complementary opposites, while those in (5b, d) consist of antonymic opposites:

By the very semantic nature of the connected lexemes, exocentric dvandvas may express disjunctive coordination in addition to conjunctive coordination. Moreover, this type has a third reading that refers to the underlying scale itself, as observed by Scalise et al. (2009) and Shimada (2013).

| (5) | a. | zen-aku | Exocentric |

| virtue-vice | |||

| ‘virtue and vice, good and evil’ | |||

| b. | yosi-asi | ||

| good-bad | |||

| ‘good and/or bad, right and/or wrong, merits and demerits’ | |||

| c. | ze=hi | ||

| right-wrong | |||

| ‘right and/or wrong, pluses and minuses, pros and cons’ | |||

| d. | sin=kyuu | ||

| new-old | |||

| ‘the old and the new, old or new’ | |||

What Bauer (2008) calls the exocentric type is not only semantically but also categorially exocentric. It is a bit odd to have an “exocentric” type within a class whose defining characteristic is exocentricity, but the concept of “exocentric exocentrics” is bound to emerge due to the widely recognized fact that the exocentricity in compounding is not monolithic but determined by several parameters (Namiki 2001; Scalise et al. 2009; Bauer 2010b, 2022; Nóbrega and Panagiotidis 2020). In Section 1, the exocentricity of dvandvas as a class was determined based on the “Z is a type of X/Y” headedness test, that is, semantic exocentricity. In (5), on the other hand, the parameter at work is syntactic category. According to this parameter, the head of a compound is defined as a category determinant. Thus, in (5b), the free-morph components are adjectives, while the entire constructions are nouns; this shows categorial exocentricity. Interestingly, Scalise et al. (2009, p. 65) suggest that while the notion of categorial head may be tied with typological properties of the language, “the semantic requisites of a compound are not parameterized in any language”. These observations indicate that dvandvas lack a semantic head and may also be categorially headless.

The third and fourth types of dvandvas are called co-hyponymic and co-synonymic, respectively. The following Japanese examples suggest that dvandva coordination can function to neutralize the boundary between subtypes named by co-hyponyms or co-synonyms and to synthesize them into a single new type:

In (6a), kusa-ki can literally refer to grasses and trees but is more commonly used to refer indiscriminately to everyday plants. In (7a), sugata and katati are synonyms expressing ‘outer form’, with the former being used for the outer form of someone and the latter for the external form of something. However, this boundary is neutralized in the dvandva, so sugata-katati does not discriminate the animacy of the possessor.

| (6) | a. | kusa-ki | Co-hyponymic |

| grass-tree | |||

| ‘plants, vegetation’ | |||

| b. | gyo=kai | ||

| fish-shellfish | |||

| ‘fish and shellfish’ | |||

| c. | tyoo=zyuu | ||

| bird-beast | |||

| ‘birds and animals, wildlife’ | |||

| (7) | a. | sugata-katati | Co-synonymic |

| figure-shape | |||

| ‘outward appearance’ | |||

| b. | kai=ga | ||

| picture-picture | |||

| ‘a picture; pictorial arts’ | |||

Independently of the semasiological classification, there are two observations to be made with regard to the morphophonological aspect. First, Japanese NN dvandvas retain the accent nucleus of the left component, as in (4) o’yako, te’asi, (6) kusa’ki, (7) su’gatakatati. This is said to deviate from a more dominant accent pattern of Japanese compounding where the right component acts as the determiner (Tsujimura 2014, pp. 86–96). A good example of the latter would be: a’kusento ‘accent’ + ki’soku ‘rule’ → akusentoki’soku ‘accent rule’.

Second, throughout the data in (4–7), dvandva components appear in either the [free morph + free morph] or [bound morph + bound morph] pattern; mixed realizations are not observed. This observation, which was made in Shimada (2013), fits naturally with what we saw in Section 1: the formal parallelism between coordinates. At the same time, Shimada’s observation raises the question of which pattern is more fundamental. The answer seems to be the bound + bound pattern, since many contemporary free + free examples have corresponding bound + bound realizations used in earlier times. For example, the example in (4b) transcribes the so-called kun-reading ‘Japanese reading’ of the word written手足, but this word used to be read as syu=soku in the on-reading ‘Chinese reading’. Significantly, the kun and on-readings of a kanji character are bound and free morphic realizations of the lexeme represented by that kanji (Nagano and Shimada 2014). Presumably, the morphophonological alternation of kanji characters contributed to the gradual emergence of the free + free pattern from the bound + bound pattern. The proposed diachronic relationship between the two realization patterns is also consistent with the emergence of minor exceptions to the rule of the same-morph type realization.4

To summarize this section, classic dvandvas are semantically exocentric compounds that asyndetically coordinate co-meronyms, converse/complementary/antonymic opposites, co-hyponyms, or co-synonyms. Furthermore, the formal parallelism between the coordinates, or a strong propensity toward it, can be observed in a number of languages.

2.2. Dvandva from an Onomasiological Perspective

Dvandva compounds typically name a higher-level concept or superset that includes the referents of its components as smaller subsets. Thus, from an onomasiological perspective, classic dvandvas belong to the catalogue of constructions that have been gathered under the umbrella of lexical plurals (Acquaviva 2008; Lauwers and Lammert 2016; Gardelle 2019).

For example, additive dvandvas are similar to group nouns such as committee, family, herd, nation, etc., and bipartite nouns such as a pair of {shoes/socks/earrings/gloves…} (cf. a shoe) and a pair of {glasses/scissors/trousers…} (cf. *a glass) (Huddleston and Pullum 2002, pp. 340–42). They all name spatially bounded units that are composed of separable similar internal units. In the LSF (Lexical Semantic Framework), where lexical semantics is described as bundles of features (Chomsky 1965), such nouns share the quantity-related semantic features [+B (bounded), +CI (composed of individuals)] defined as follows (Lieber 2004, p. 136):

- [B]: This feature stands for “Bounded.” It signals the relevance of intrinsic spatial or temporal boundaries in a situation or substance/thing/essence. If the feature [B] is absent, the item may be ontologically bounded or not, but its boundaries are conceptually and/or linguistically irrelevant. If the item bears the feature [+B], it is limited spatially or temporally. If it is [−B], it is without intrinsic limits in time or space.

- [CI]: This feature stands for “Composed of Individuals.” The feature [CI] signals the relevance of spatial or temporal units implied in the meaning of a lexical item. If an item is [+CI], it is conceived of as being composed of separable similar internal units. If an item is [−CI], then it denotes something which is spatially or temporally homogeneous or internally undifferentiated.

A brief introduction of the LSF would be appropriate. At the most basic level, lexemic concepts are categorized into either situation (which encompasses event/state) or substance/thing/essence. These categories are then broken down into two-stratum bundles of features: body, which contains encyclopedic information, and skeleton, which is a hierarchically organized structure of functions (F) and their arguments. Skeletons are represented in a format suggested below, with 1 and 2 representative ones.

The F(unction) stands for a grammatically relevant semantic feature, such as [material], [dynamic], [Loc] (location), [IEPS] (inferable eventual position or state), [Scalar], [Animate], [B], and [CI]. For instance, the skeleton of the simplex noun dog is of the first type, as illustrated below, where [+material] refers to its primary functional feature and the inner brackets represent its referential argument. The complex word writer has a more intricate skeleton in which one set of features and arguments is embedded under another:

The second structure reflects the process of word formation, where the higher set corresponds to the affix (-er) skeleton and the embedded set corresponds to the base verb (write) skeleton. The highest arguments of the two componential representations are coindexed through the working of the Principle of Coindexation (Section 4.2.1, (27)).

| 1 | [F1 ([argument])] |

| 2 | [F2 ([argument], [F1 ([argument])])] |

| 1 | dog | [+material ([ ])] |

| 2 | writer | [+material, dynamic ([i ], [+dynamic ([i ], [ ])])] |

As elaborated in Lieber (2004, chap. 5), the quantity-related semantic features [B] and [CI] are given in the skeletons of nouns and verbs and capture the widely recognized parallelism between nouns and verbs in their quantitative semantic properties, namely, number and lexical aspect. Thus, the parallelism between singular count nouns (e.g., person, fact) and non-repetitive punctual verbs (e.g., explode, name) is captured by their possession of the featural complex [+B, −CI]. Mass nouns (e.g., furniture, water) and non-repetitive durative verbs (e.g., descend, walk) are similar because they share the featural complex [−B, −CI]. The feature [+CI], our focus, underlines group nouns (e.g., committee, herd), plural nouns (e.g., cattle, sheep), and repetitive durative verbs (e.g., totter, pummel, wiggle). As summarized in Table 1, group nouns have no verbal counterparts because “[…] for a verb to be intrinsically [+B, +CI] it would have to denote an event that is at the same time instantaneous/punctual and yet made up of replicable individual events, a combination which does not seem possible” (Lieber 2004, p. 139):

Table 1.

Application of quantitative features to nouns and verbs (Lieber 2004, pp. 137, 139).

These features differ from Jackendoff’s (1996) features [b] and [i] (Lieber 2004, pp. 141–44). Because the latter features are aimed to account for the property of telicity, an aspectual property observed at the level of the verb phrase or whole sentence, they are underspecified at the lexical level. On the other hand, the target of the LSF theory is lexemes and morphology, and the features [B] and [CI] belong to nouns, verbs, and derivational affixes.5

The next important point is that LSF features can be manipulated by morphology. In English, for example, the semantic contribution of the progressive suffix -ing is to add the feature [−B] to the base lexeme, while the plural suffix -s contributes the feature complex [−B, +CI]. In derivational morphology, the suffixes -ery and -age produce collective nouns from singular count nouns, as in jewelry from jewel, peasantry from peasant, mileage from mile, wreckage from wreck. This observation is explained if the suffixes “add the features [+B, +CI] to their base, indicating that the derived noun is to be construed as a bounded aggregate or collectivity of individuals related to the base noun” (Lieber 2004, p. 149). In other words, the two derivational suffixes possess the skeleton [+B, +CI ([ ], <base>)], in which <base> represents the skeleton of the base to be embedded. The derivational prefix re-, on the other hand, adds the feature [+CI] to certain types of base verbs to produce repetitive verbs, as in redescend from descend, rebuild from build, rename from name (Lieber 2004, p. 147):

For example, redescend has the composed skeleton in which the <base> slot of the prefix is saturated with the skeleton of descend: [+CI ([ ], [+dynamic ([ ])])]. While Lieber (2004, chap. 5) does not discuss compounding in this context, below, we argue that a similar analysis can be extended to dvandvas; that is, dvandva compounding extrinsically adds the feature [+CI] to the semantic contributions of the component lexemes.

| 3 | -ery/-age | [+B, +CI ([ ], <base>)] |

| 4 | re- | [+CI ([ ], <base>)] |

First, the co-occurrence with the collective classifier kumi ‘group’ shows that additive dvandvas refer to spatially bounded objects; that is, they carry the [+B] feature.

The fact that oya-ko is also associated with the feature [+CI] is confirmed by various tests. For example, compound verbs headed by aw- ‘meet’ require a plural subject (Yumoto 2005, p. 201), as shown by the following minimal pair (atta is the final realization of the combination of aw- and the past-tense suffix -ta):

In this construction, the syndetic coordinative phrase can be replaced by an additive dvandva compound, as follows:

In (10), a singular number or possessive phrase is added to the dvandva subject to ensure that there is only one collective set.

| (8) | a. | hitokumi | no | oya-ko |

| one-group | gen | parent-child | ||

| ‘parents and children as one group’ | ||||

| b. | hutakumi | no | oya-ko | |

| two-group | gen | parent-child | ||

| ‘two groups of parents and children’ | ||||

| c. | hyakkumi | no | oya-ko | |

| one-hundred-group | gen | parent-child | ||

| ‘100 groups of parents and children’ | ||||

| (9) | a. | Taroo | to | Hanako | ga | {hure-atta | / warai-atta} |

| and | nom | touch-meet.pst | smile-meet.pst | ||||

| ‘Taro and Hanako {touched each other/smiled at each other}.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Taroo | ga | {hure-atta | / warai-atta} | |||

| nom | touch-meet.pst | smile-meet.pst | |||||

| (10) | a. | Hitokumi | no | oya-ko | ga | {hure-atta | / warai-atta}. |

| one-group | gen | parent-child | nom | touch-meet.pst | smile-meet.pst | ||

| ‘A parent and her child {touched each other/smiled at each other}.’ | |||||||

| b. | Hanako | no | te-asi | ga | hure-atta. | ||

| gen | hand-foot | nom | touch-meet.pst | ||||

| ‘Hanako’s hand and foot touched each other.’ | |||||||

Next, while the non-additive types of dvandva nouns do not naturally co-occur with a collective classifier such as kumi ‘group’, it is certain that they are conceived of as being composed of separable similar internal units. This suggests that non-additive dvandvas are like lexically plural nouns with the [−B, +CI] features, such as cattle and sheep.

Studies on number-marking languages report that countable dvandvas exhibit lexical plural marking, as illustrated below by (11) Sanskrit examples from Whitney ([1879] 1962, p. 485), (12) Modern Greek examples from Ralli (2019, p. 7), and (13) Mordvin examples from Wälchli (2005, pp. 137, 139).

The number markings in (11–13) are lexical rather than grammatical because they do not count the number of the referent of the whole construction, as is usually observed in countable endocentric NN compounds. That is, the grammatical number marking of prayer books, for example, refers to the plurality of prayer books. In contrast, in (11a), the dual suffix does not mean that there are two elephant-horse sets; rather, it counts the number of homogenized set members: an elephant as one such member + a horse as another such member = two members. Similarly, in (13a), where multiple exponence (Harris 2017) is observed, the plural suffixes are concerned with the plurality of set members, not sets (dual is already lost at this stage of the language (Corbett 2000, p. 203)). In English, Anglo-Saxon presents a similar case; the following paraphrase of this dvandva by Renner (2008, p. 609) suggests that the suffix -s refers to the summation of Angles and Saxons:

| (11) | a. | hastyaśvau | Sanskrit |

| elephant (hastin-)-horse (aśva-).du | |||

| ‘elephant and horse’ | |||

| b. | hastyaśvāḥ | ||

| elephant-horse. pl | |||

| ‘elephants and horses’ |

| (12) | a. | jinek-o-peδa | Modern Greek |

| woman-CM-child.pl | |||

| ‘women and children’ | |||

| b. | maxer-o-piruna | ||

| knife-CM-fork.pl | |||

| ‘cutlery’ | |||

| c. | ader-o-sikota | ||

| intestine-CM-liver.pl | |||

| ‘intestines and livers’ |

| (13) | a. | t’et’a.t-ava.t | Mordvin |

| father.pl-mother.pl | |||

| ‘parents’ | |||

| b. | ponks.t-panar.t | ||

| trousers.pl-short.pl | |||

| ‘clothing, clothes’ |

| (14) | a. | Anglo-Saxons are Angles plus Saxons. |

| b. | *An Anglo-Saxon is an Angle plus a Saxon. |

In conclusion, it seems safe to say that the feature [+CI] is the overarching onomasiological characteristics of dvandvas. This finding can be explained if, as mentioned above, dvandva compounding extrinsically adds the feature [+CI] to the semantic contributions of the component lexemes. For example, the additive dvandva in (4a), oya-ko ‘a parent and child’, would be produced as follows:

The output compound oya-ko is exocentric precisely because there is no overt morph matching with the added feature [+CI] (although the lexical plural markers in (11–14) may be such morphs).

| (15) | [+material ([ ])] | + | [+material ([ ])] | → | [+CI ([ ], [+material ([ ])], [+material ([ ])])] | ||

| oya | ko | oya | ko | ||||

If this analysis is on the right track, the category-neutral nature of the quantity-related features (see the definitions above) and the impossibility of [+B, +CI] in the verbal domain (see Table 1) lead to the following predictions: (i) there should be VV dvandvas that behave like [−B, +CI] words; (ii) there should be no VV dvandvas that behave like [+B, +CI] words.

3. Data

The above prediction can be tested with data from Japanese, a language that is rich in VV compounds. Traditionally, the term “VV compound” is used restrictively to refer to biverbal compounds that inflect as unambiguous verbs (pattern A), but as will be shown presently, this is not the only pattern in which two native verbs are compounded (pattern B).

3.1. Pattern A

In pattern A, the dominant approach identifies lexically and syntactically produced types (Kageyama 1993; Matsumoto 1996; Fukushima 2005; Yumoto 2005; see Kageyama 2009 for an overview). In lexical VV compounds, all grammatical relations are attested, as indicated below with examples from Fukushima (2005) and Yumoto (2005, chap. 3). The parenthesized parts of the linguistic materials are present-tense inflectional suffixes.

| (16) | a. | Subordination (complementation) |

| mi-otos(u) | ||

| look-fail | ||

| ‘to fail to see, to overlook’ | ||

| Subordination (resultative) | ||

| tataki-war(u) | ||

| hit-break | ||

| ‘to break (something) by hitting it’ | ||

| b. | Modification (manner) | |

| tobi-oki(ru) | ||

| jump-get up | ||

| ‘to get up in a jumping motion’ | ||

| moti-yor(u) | ||

| have-approach | ||

| ‘to bring’ | ||

| c. | Coordination | |

| See the examples in (17) |

Yumoto’s (2005) data on coordination is expanded below, with additional examples from Niinuma (2015) and Yonekura et al. (2023, chap. 4). Pattern A coordination combines co-synonyms or (rarely) a pair of reversive opposites. In our judgments, the first and second examples in (17a) differ only in that the latter is somewhat depreciative and can be used of an inanimate, noisy object in addition to a person or animal.

| (17) | a. | naki-sakeb(u) | co-synonymic/nonrepetitive durative |

| cry-scream | |||

| ‘to cry and scream’ | |||

| naki-wamek(u) | |||

| cry-scream | |||

| ‘to cry and scream’ | |||

| ukare-sawag(u) | |||

| be excited-be noisy | |||

| ‘to be noisy’ | |||

| hikari-kagayak(u) | |||

| shine-shine | |||

| ‘to shine’ | |||

| omoi-egak(u) | |||

| think-picture | |||

| ‘to imagine’ | |||

| nageki-kanasim(u) | |||

| lament-be sad | |||

| ‘to mourn’ | |||

| tae-sinob(u) | |||

| bear-endure | |||

| ‘to bear’ | |||

| koi-sitaw | |||

| long for-adore | |||

| ‘to long for, to miss deeply’ | |||

| imi-kiraw | |||

| avoid-hate | |||

| ‘to detest’ | |||

| b. | odoroki-akire(ru) | co-synonymic/punctual | |

| be surprised-be appalled | |||

| ‘to be surprised’ | |||

| nare-sitasim(u) | |||

| get used to-get friendly | |||

| ‘to get used to and like’ | |||

| c. | ake-kure(ru) | reversive | |

| (day) begin-(day) end | |||

| ‘to spend all one’s time doing’ |

Throughout (16) and (17), regardless of the variation of the internal grammatical relationship, all instantiations are morphologically uniform, with the first verb occurring in the infinitive form (called ren’yoo) and the second verb occurring in the basic form for tense inflection. The former ends in either /i/ or /e/, depending on whether the root is consonant-ending or vowel-ending. As expected from the righthand head rule (Williams 1981), the second component of pattern A accommodates an inflectional suffix to mark the tense, aspect, and modality of the entire construction; for example, the present tense forms of (16) are produced by adding the suffix -u, as in mi-otos-u, tataki-war-u, tobi-okir-u, respectively. For verbs ending in /w/, the final sound and the suffix are assimilated. When the verb ends in a vowel, it selects -ru rather than -u, so the example in (17c) will be ake-kure-ru in the present tense. In short, pattern A is composed of different morphological types according to the formal schema [X-i/e Y], where X and Y represent morphophonological materials from the component verbs. In this schema, the constant /i/ or /e/ can overlap with the final front vowel of the first verb stem.

In addition to morphology, the subordinate, modificational, and coordinate types share the garden-variety compound accent pattern (Yumoto 2005, pp. 114–15). Thus, all examples in (16, 17) have an accent nucleus on the second component, as in (16a) mioto’s(u), tatakiwa’r(u), (16b) tobioki’(ru), (17a) nakisake’b(u).

3.2. Pattern B

In the same language, native verbs occur in another coordinative construction, called pattern B here. Pattern B combines a pair of converses, i.e., directional opposites denoting the same situation from different perspectives (such as ur(u) ‘sell’ + kaw ‘buy’, yar(u) ‘give’ + moraw ‘receive’) or a pair of reversives, i.e., directional opposites denoting movement or change (such as ik(u) ‘go’ + kur(u) ‘come’, agar(u) ‘ascend’ + kudar(u) ‘descend’). Pattern B also includes combinations of co-hyponymic verbs such as yom(u) ‘read’ + kak(u) ‘write’, mir(u) ‘see’ + kik(u) ‘hear’, and nom(u) ‘drink’ + kuw ‘eat’). Following Ueno (2016), Yuhara (Yuhara, forthcoming) calls the following constructions non-conjugational verbs and suggests the internal structure of [verb zero-form + verb zero-form]:

As the translations show, these compounds are also asyndetic coordinations of two native verbs. However, they differ from pattern A in the morphological form of the second component. Here, not only the first but also the second verb occurs in the infinitive form, according to the formal schema [X-i/e Y-i/e] (as before, X and Y are variables of verb roots; the choice of -i or -e depends on the root).

| (18) | a. | uri-kai | (*uri-kaw) | converse/repetitive durative |

| sell-buy | ||||

| ‘to sell and buy’ | ||||

| yari-tori | (*yari-tor(u)) | |||

| give-take | ||||

| ‘to exchange (things, information), to talk, to discuss’ | ||||

| yari-morai | (*yari-moraw) | |||

| give-receive | ||||

| ‘to give and take’ | ||||

| uke-kotae | (??uke-kotae(ru)) | |||

| receive-reply | ||||

| ‘to receive and reply’ | ||||

| uke-watasi | (uke-watas(u)) | |||

| receive-give | ||||

| ‘to receive and give’ | ||||

| b. | iki-ki | (*iki-kur(u)) | reversive/repetitive durative | |

| come-go | ||||

| ‘to come and go’ | ||||

| agari-sagari | (*agari-saga(ru)) | |||

| ascend-descend | ||||

| ‘to ascend and descend’ | ||||

| nobori-ori | (*nobori-ori(ru)) | |||

| rise-fall | ||||

| ‘to rise and fall’ | ||||

| de-iri | (*de-ir(u)) | |||

| exit-enter | ||||

| ‘to enter and exit’ | ||||

| dasi-ire | (*dasi-ire(ru)) | |||

| put in-take out | ||||

| ‘to put in and take out’ | ||||

| ake-sime | (*ake-sime(ru)) | |||

| open-close | ||||

| ‘to open and close’ | ||||

| c. | ne-tomari | (*ne-tomar(u)) | co-hyponymic/ repetitive durative | |

| sleep-stay | ||||

| ‘to stay at, stay with’ | ||||

| mi-kiki | (*mi-kik(u)) | |||

| see-hear | ||||

| ‘to experience’ | ||||

| nomi-kui | (*nomi-ku(u)) | |||

| drink-eat | ||||

| ‘to eat and drink’ | ||||

| yomi-kaki | (*yomi-kak(u)) | |||

| read-write | ||||

| ‘to read and write’ | ||||

The parenthesized asterisks indicate that the pattern [X-i/e Y] is not acceptable, except in exceptional cases. This means that the compounds in (18) cannot be word-internally inflected. The absence of a tense-inflectable stem necessitates periphrastic inflection by means of the light verb suru ‘do’.6 The present tense inflection of the double infinitive compound is illustrated in (19).

The morphological behavior shown in (19) indicates that the syntactic category of the whole construction is either a non-conjugational verb (Ueno 2016; Yuhara, forthcoming) or a verbal noun (Miyamoto and Kishimoto 2016). The decision affects whether the whole construction is categorially endocentric or exocentric. If VV compounding produces non-conjugative verbs, the process is categorially endocentric, whereas if it produces verbal nouns, it is categorially exocentric. It should be emphasized, however, that the output category controversy does not affect the characterization of pattern B as a type of VV coordinate compound because the input category is clearly a verb. That is, the components of the items in (18) are not deverbal nominalizations because the data do not show the monosyllabicity avoidance that characterizes such constructions. Specifically, if the items in (18) were produced by NN compounding, combining so-called ren’yoo deverbal nominalizations, iki-ki, de-iri, ne-tomari, and mi-kiki would, contrary to the fact, not exist because monosyllabic nominalizations such as *ki, *ne, and *mi are not attested. In short, the structure of pattern B is either [VV]V or [VV]VN, but it is not [N+N]VN. This conclusion is independently supported by the fact to be discussed below, that there is no [+B, +CI] word in the productions of pattern B. As we have seen in Table 1 (Section 2.2), this particular combination of semantic features is possible in the nominal domain but logically impossible in the verbal domain.

| (19) | Present tense inflection of the double infinitive compound | |||||

| a. | yomi-kaki | → | *yomi-kaku | vs. | yomi-kaki suru | |

| read-write | read-write.pres | read-write do.pres | ||||

| ‘to read and write’ | ||||||

| b. | iki-ki | → | *iki-kuru | vs. | iki-ki suru | |

| come-go | come-go.pres | come-go do.pres | ||||

| ‘to come and go’ | ||||||

| c. | ne-tomari | → | *ne-tomaru | vs. | ne-tomari suru | |

| sleep-stay | sleep-stay.pres | sleep-stay do.pres | ||||

| ‘to sleep and stay’ | ||||||

In (16, 17), it was observed that the formal schema [X-i/e Y] is ubiquitous in the syntactico-semantic division of subordination, modification, and coordination. The same is true of the second schema [X-i/e Y-i/e]; below, (20c) is reproduced from (18c), but (20a, b) are new, indicating the availability of the double infinitival schema for the relations other than coordination.

The component verbs in (20a, b) are connected by the complement+head and modifier+head relations, respectively. As suggested, many subordinative and modificational types have competing inflectable counterparts (Fukushima 2005, pp. 573–74). In contrast, the competition is virtually absent from the coordinative type. This observation is explained as a case of what Aronoff (2023) calls elsewhere distribution, which arises from the operation of the Pānini’s principle—periphrastic inflection is the default rule that is mobilized only when word-internal inflectional rules are unavailable structurally or for some psycholinguistic reasons. The coordinate type uses periphrastic inflection, as indicated in (20c); the default rule is legitimately mobilized because the word-internal inflection rule will produce forms like *yomi-kak(u), that is, forms that violate the formal parallelism of the coordinate components (Section 1 and Section 2.1). On the other hand, the subordinative and modificational types may employ the internal inflection because they are outside the scope of this constraint due to the very nature of the grammatical relationships. In these types, the competition between the two synonymous forms just continues, which is not anything unusual in natural languages (Dukic and Palmer 2024; Bagasheva et al., forthcoming).

| (20) | a. | Subordination | ||

| ii-yodomi | cf. ii-yodom(u) | |||

| say-hesitate | say-hesitate(.pres) | |||

| ‘to hesitate to say’ | ||||

| tori-kesi | cf. tori-kes(u) | |||

| take-remove | take-remove(.pres) | |||

| ‘to take back’ | ||||

| obore-zini | cf. obore-sin(u) | |||

| drown-die | drown-die(.pres) | |||

| ‘to die by drowning’ | ||||

| b. | Modification | |||

| susuri-naki | cf. susuri-nak(u) | |||

| sniffle-cry | sniffle-cry(.pres) | |||

| ‘to sob’ | ||||

| tati-yomi | cf. *tati-yom(u) | |||

| stand-read | stand-read(.pres) | |||

| ‘to read standing up, to browse in a bookstore’ | ||||

| c. | Coordination | |||

| yomi-kaki | cf. *yomi-kak(u) | =(18c) | ||

| read-write | read-write(.pres) | |||

| ‘to read and write’ | ||||

In pattern B, the coordinate type also differs from the subordinative and modificational types in the accent pattern. The latter two types are accentless, while the coordinate type carries an accent on the first component, as in (20a) iiyodomi, (20b) susurinaki vs. (20c) yomi’kaki. As pointed out in Section 2.1, Japanese NN dvandvas also have an accent on the first component (when each component is a free morph).

3.3. Comparison between the Two Patterns

The observations in the previous subsections suggest that Japanese has two patterns of VV coordinate compounding. In the first pattern, the output compounds are conjugational verbs, while the second pattern yields non-conjugational verbs or verbal nouns. For ease of reference, they are referred to as pattern A and pattern B, respectively. Their properties are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of VV coordinate compounding patterns in Japanese.

Table 2.

Comparison of VV coordinate compounding patterns in Japanese.

| Pattern A | Pattern B | |

|---|---|---|

| Formal schema | X-i/e Y 1 | X-i/e Y-i/e |

| Inflection | word internal | periphrastic |

| Structure | [V + V]V | [V + V]V or [V + V]VN |

| Accent pattern | Same as the subordinate and modificational types | Same as the NN dvandva |

| Semantic relation | co-synonymic, reversive | reversive, converse, co-hyponymic |

1 X and Y represent phonological variables to be filled with the materials of component verbs. In this schema, the phonological constant /i/ or /e/ may overlap with the final front vowel of the first root.

In a different strand of research, Bauer (2008, p. 10) cites naki-sakeb(u) (17a) and yomi-kaki (18c) both as VV dvandvas. In his classification (Section 2.1), patterns A and B can be seen as manifestations of different dvandva subtypes in the verbal domain. Indeed, Yonekura et al. (2023, p. 231) take this position, suggesting that pattern A belongs to the co-synonymic type of dvandva. However, in our view, the obvious morphophonological differences between the two patterns cannot be easily ignored. In Modern Greek, another dvandva-rich language, dvandvas and appositive coordinate compounds are distinguished primarily by their formal properties. The dvandva compounds shown in (12) consist of two bound stems connected by the characteristic compound marker (CM) -o-. In contrast, according to Ralli (2013, p. 255), the appositive asyndetic construction consists of two independent words and does not involve -o- in-between (e.g., iθopios-traγuδistis ‘actor-singer’) (see also Manolessou and Tsolakidis 2009 for the classical language).

In the verbal domain, Hungarian has a VV dvandva equivalent to nomi-kui (drink-eat) in (18c), eszik-iszik (eat-drink) ‘eat and drink’. According to Kiefer (2009, p. 540), the past inflection of this compound is realized on both components, as follows: ev.ett-iv.ott (eat.pst-drink.pst) ‘he/she ate and drank’. Similarly, in Japanese, pattern B maintains a robust formal parallelism between the coordinates in the schema X-i/e Y-i/e. According to the minimalist perspective adopted in Yonekura et al. (2023, chap. 4), this type of non-asymmetric merge presents a challenge for the labelling algorithm, which may explain why the derivation results in an exocentric construction. On the other hand, pattern A exhibits formal asymmetry as it shows -i/-e only on the first constituent, revealing its affiliation with “ordinary” endocentric compounding. The question remains: If pattern A is not dvandva, then what is it? If pattern B is a verbal counterpart of the classic dvandva compounding, the most plausible hypothesis would be that pattern A is a verbal counterpart of the appositive coordinate compounding. This hypothesis is natural because, as demonstrated in Section 1, appositives are a type of endocentric coordination that partially overlaps with the modifier + head relationship.

The form-based distinction becomes much more plausible and empirically grounded when attention is paid to a further contrast between pattern A and pattern B. At the end of Section 2.1, it was observed that classic Japanese dvandvas occur in either the [free morph + free morph] or [bound morph + bound morph] pattern, and that many contemporary free + free examples have corresponding older bound + bound realizations. Significantly, this generalization applies to pattern B, but not to pattern A. As suggested in Table 3, pattern B compounds have a bound + bound synonym. In Table 3, the Sino-Japanese pronunciations are used in formal diction, while the native pronunciations have no stylistic restrictions. Syntactically, the Sino-Japanese forms are also non-conjugational verbs (or verbal nouns), as suggested by the parenthesized suru in the first example.

Table 3.

Pattern B compounds with Sino-Japanese forms.

Now, pattern A also uses the native pronunciation, but with it, the alternation with the Sino-Japanese pronunciation is much weaker. In (17), only koi-sitaw- can be matched with ren=bo, and outside the list in (17), oi-motome(ru) (lit. follow-pursue) ‘pursue’ and tui=kyuu (追求) may be mutually related. Historically, pattern A may have been associated with bound + bound synonyms, but the association is much less easily identifiable than with pattern B. This perspective sheds light on why ake-kurer(u) in (17c) behaves as pattern A; semantically, the coordination of reversives is an odd one out in the list of (17), but the item is like the other examples in that it has no living bound + bound synonym.7

In summary, this section has begun to explore the similarities and differences between the two patterns of native verb compounding in Japanese. Both patterns involve combining two native verbs in a coordinative relationship. However, pattern A is characterized by the categorial headedness, while pattern B may not. Additionally, the coordinates of pattern A are formally asymmetrical, while those of pattern B are formally symmetrical or parallel. These results suggest that pattern B is a verbal counterpart of the classic dvandva compounding, while pattern A is a verbal counterpart of appositive coordinative compounding. The next section will test this hypothesis from an onomasiological perspective.

4. LSF Analysis

In her contribution to the Oxford Handbook of Compounding (Lieber and Štekauer 2009), R. Lieber attempts a unified cross-categorial analysis of English NN compounds and Japanese VV compounds. After showing how the LSF (Lexical Semantic Framework) successfully describes English subordinate, modificational, and appositive compound nouns, she goes on to show “that at least some sort of V+V compound that is common in Japanese is amenable within the system developed here with no added machinery” (Lieber 2009, p. 100). In the LSF, the signified lexemes and affixes are represented as two-level representations; the skeleton contains the grammatical-semantic features and argument structure of the lexeme, while the body contains its encyclopedic features. The process of word formation is conceived as a kind of merge, combining the two-stratum semantic representations of the inputs into a meaningful, similarly two-stratum representation, in accordance with the Principle of Coindexation. The three types of endocentric compounds in (1a–c) are all produced by merging and coindexing the skeleton of the head with that of the non-head. Exocentric compounds are also divided into the subordinate, modificational, and coordinate types (Scalise and Bisetto 2009); thus, pickpocket, cutpurse, etc., belong to the subordinate type, airhead, hardhat (‘a reactionary or conservative person’), etc., belong to the modificational type, and dvandvas represent the coordinate type. According to Lieber’s (2016a, pp. 51–52) metonymy-based analysis, exocentric compounding differs from endocentric compounding in that the process involves not only (i) the merge and coindexation between the skeletons (and bodies, if applicable) of the components but also (ii) the external merge of this composite representation with an additional feature.

4.1. The Lexical Aspect of the Output

Before delving into the process of coordinate compounding, we first examine the output semantics of Japanese VV coordinate compounds from the perspective keyed to the quantity-related features [B, CI]. Let us recall the two predictions from the onomasiological definition of classic dvandvas (Section 2.2), according to which (i) there should be VV dvandvas that behave like [−B, +CI] words, and (ii) there should be no VV dvandvas that behave like [+B, +CI] words. Indeed, as will become clear, pattern B behaves as repetitive verbs, i.e., [−B, +CI]. Pattern A, on the other hand, behaves as either non-repetitive durative or punctual verbs, i.e., [±B, −CI].

Our conceptual basis is that of Lieber (2004, chap. 5), as already mentioned in Section 2.2. The quantity-related features [B] and [CI] are used to characterize quantitative or aspectual classes among simplex verbs, not among verb phrases (Lieber 2004, pp. 141–44), in the following way:

I propose that the feature [B] to be used to encode the distinction between temporally punctual situations and temporally durative ones. [+B] items will be those which have no linguistically significant duration, for example explode, jump, flash, name. [−B] items will be those which have linguistically significant duration, for example, descend, walk, draw, eat, build, push.(Lieber 2004, p. 137)

This view nicely captures the output semantics of the two patterns in Table 2: iterativity (pattern B) vs. homogeneity (pattern A).Plural nouns denote multiple individuals of the same kind, non-plural nouns single individuals, or mass substances. I would like to suggest that the corresponding lexical distinction in situations is one of iterativity vs. homogeneity. Some verbs denote events which by their very nature imply repeated actions of the same sort, for example, totter, wiggle, pummel, or giggle. By definition, to totter or to wiggle is to produce repeated motions of a certain sort, to pummel is to produce repeated blows, and to giggle to emit repeated small bursts of laughter. Such verbs, I would say, are lexically [+CI]. The vast majority of other verbs would be [−CI]. Verbs such as walk or laugh or build, although perhaps not implying perfectly homogeneous events, are not composed of multiple, repeated, relatively identical actions.(Lieber 2004, pp. 138–39; footnotes in the original omitted)

First, we examine the [−B] property of pattern B compounds. The sentences below show that even when the component verbs are punctual, pattern B compounds are durative, accepting a time adverbial denoting a relatively long period of time.

The durativity is closely related to the iterativity or multiple occurrences of the same kind of event, i.e., the [+CI] property. Thus, in (21a), the converse verbs of giving and receiving describe a single situation from different perspectives; hence, the two events cannot be performed simultaneously by one agent. While the simultaneous reading becomes possible with a plural subject (Section 4.2.3), sentences such as (21a) express the repeated alternation of giving and receiving by one or more than one agent, as is observed with the English symmetrical predicate exchange or the binomial give and receive. In (21b-d), the component verbs are reversive or co-hyponymic verbs, describing events that cannot be performed simultaneously by one agent; rather, these events are interpreted as repetitive alternates of a similar kind. In (21e), spending the night at the aunt’s house is repeated throughout the summer.

| (21) | a. | Converse | |||||||||

| Taro | wa | sannen kan | Hanako | to | meeru | o | yari-tori | sita | |||

| top | three years for | with | acc | give-take | do.pst | ||||||

| ‘Taro exchanged e-mails with Hanako for three years.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Reversive | ||||||||||

| Taro | wa | sannen kan | ie | to | sono byooin | o | iki-ki | sita | |||

| top | three years for | house | and | the hospital | acc | go-come | do.pst | ||||

| ‘Taro went back and forth between his house and the hospital for three years.’ | |||||||||||

| c. | Reversive | ||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | hito ban zyuu | sono | mado | o | ake-sime | sita | ||||

| top | one night through | the | window | acc | open-close | do.pst | |||||

| ‘Hanako opened and closed the window all through the night.’ | |||||||||||

| d. | Co-hyponymic | ||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | natu zyuu | sore | o | mi-kiki | sita | |||||

| top | summer through | that | acc | see-hear | do.pst | ||||||

| ‘Hanako saw and heard it all through the summer.’ | |||||||||||

| e. | Co-hyponymic | ||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | natu zyuu | oba | no | ie | de | ne-tomari | sita | |||

| top | summer through | aunt | gen | house | at | sleep-stay | do.pst | ||||

| ‘Hanako spent the summer at her aunt’s house.’ | |||||||||||

The verbs in (21) are ambiguous and can also be used to denote a single, non-repeated event in the simple past tense with no indication of its habitual nature. This usage will be explored in Section 4.2.3, but anticipating a little bit, we observe that even when the iterative interpretation is contextually inactivated, the [+CI] property of pattern B compounds manifests itself in other ways. For instance, as an anonymous reviewer correctly points out, the dvandvas below denote a single, non-repeated event.

This fact forces us to think more deeply about the connection between [+CI] and interativity, which would not be one-to-one. However, pattern B is characterized by the skeletal feature [+CI] even when the compound is interpreted non-habitually because in example (22a), it should be observed that what Hanako did was only to “hear” the rumor. One cannot “see” a rumor. In other words, in the suggested reading, the two subevents of mi-kiki (see-hear) are not activated simultaneously, but rather only the “kiki” event is.

| (22) | a. | Co-hyponymic | |||||||

| Hanako | wa | kyoo | henna uwasa | o | mi-kiki | sita | |||

| top | today | queer rumor | acc | see-hear | do.pst | ||||

| ‘Hanako heard a queer rumor today.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Reversive | ||||||||

| Kyoo | sono | zyosidai | ni | dansigakusei | ga | de-iri | sita | ||

| Today | the | women’s college | goal | male student | nom | exit-enter | do.pst | ||

| ‘Today, a male student (or male students) visited the women’s college.’ | |||||||||

In (22b), the componential events “exit” and “enter” can be performed simultaneously only if the sentence is associated with a plural subject, and the members constituting the plural subject are separately associated with one or the other of the coordinated subevents. If the subject referent is singular, with dansigakusei referring to a male student, sentence (22b) conveys that the reversive events are performed separately by that subject, with an appropriate time interval between them.

From this and other observations to be made in Section 4.2.3, we argue that not only in the iterative reading but also in the single-event reading pattern B compounds are semantically conceived of as being composed of separable similar internal units, as stated in the definition of the feature [+CI] (Section 2.2).

Returning to the comparison between patterns A and B, what is crucial at this point is the contrast between the two patterns with respect to the availability of the iterative reading in the simple past tense. Unlike pattern B, pattern A shows no habitual or repeated action interpretation in the simple past tense. In the simple past tense, compounds of this type always describe a single event anchored to a single spatiotemporal stage; aspectually, they divide into non-repetitive durative verbs such as (17a) and punctual verbs such as (17b) depending on the aspectual property of the component synonymous verbs. For example, nak(u) ‘cry’ and wamek(u) ‘scream’ are both non-repetitive durative verbs; their composition naki-wamek(u) is also such a verb, as suggested in (23a). The punctuality of nare-sitasim(u) observed in (23b) is explained in the same way, as an inheritance of the aspectual property of the component verbs.

Clearly, pattern A compounds carry the feature complex [±B, −CI]. Now, the same is true of appositive coordinate compounds. Typical English examples denoting occupations or other human roles, such as those in (2), are [+B, −CI] when functioning as syntactic arguments:

| (23) | a. | Nonrepetitive durative | ||||||

| Taro | wa | nizikan | naki-wameita | |||||

| top | two hours | cry-scream.pst | ||||||

| ‘Taro cried and screamed for two hours.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Punctual | |||||||

| Hanako | wa | (*nizikan) | sono sensei | ni | nare-sitasinda | |||

| top | two hours | the teacher | dat | get used-grow intimate.pst | ||||

| ‘Taro and Hanako got to know and like the teacher.’ | ||||||||

| (24) | a. | I met a singer-songwriter. |

| b. | We hired three singer-songwriters. |

Based on the observations above, it is reasonable to conclude that our hypothesis is empirically sound. Pattern B behaves like classic dvandva compounds, exhibiting the characteristics of [+CI] words. The following subsection will compare pattern A and pattern B in terms of the compounding process.

4.2. The Principle of Coindexation

4.2.1. English VV Coordinate Compounding

In the literature on English VV coordinate compounds such as stir-fry, blow-dry, and slam-dunk (Bagasheva 2012 for a lucid overview), the distinction between simultaneous and sequential readings has been a topic of some importance (Renner 2008; Bauer 2017). In the following example taken from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (Davies 2008; underline added), did the speaker perform the two actions, stirring and frying, simultaneously or sequentially?

Though this is an interesting question, the compound verb invariably describes a single event anchored to a single spatiotemporal point; that is, whether in the simultaneous or sequential reading, the speaker performed the two actions as a single event in a single stage. Therefore, even in the sequential reading, the named actions cannot be temporally separated; for instance, sentence (25) does not allow a reading where the vegetables were stirred in the morning and then fried in the afternoon. Nor can the two actions be associated with different subjects. To see this, we modify the above sentence as follows:

While the subject now contains two agents, the sentence does not allow the distributive reading in which Mary fried a mixture of vegetables and Tom fried it (or vice versa).

| (25) | I am a vegan, so I stir fried a mixture of veggies (cabbage, thinly sliced carrots, broccoli, onions […] |

| (26) | Mary and Tom stir fried a mixture of veggies. |

These observations mean that the process underlying English VV coordinate compounds is complex predicate formation. The two coordinated events are synthesized into a single complex event in accordance with the following principle of compositional word formation:

| (27) | Principle of Coindexation | |

| In a configuration in which semantic skeletons are composed, coindex the highest non-head argument with the highest (preferably unidexed) head argument. Indexing must be consistent with semantic conditions on the head argument, if any. (Lieber 2009, p. 82) |

In the composition of the stir-fry type, the above principle works in a very strict way, as noted by Lieber (2004, p. 131):

This means that in (25, 26), not only the external arguments of stir and fry are coindexed, but also their internal arguments are coindexed.[…] verbal compounding requires not just the identification of the first argument of the head with that of the non-head, but complete identification of all arguments of the head verb with those of the non-head. In other words, when they are compounded, the first and second verbs come to share precisely the same arguments. Typically, both verbs must be transitive, and the resulting compound is transitive.

Below, we show that in the analytical methodology of the LSF framework, the components of appositive compounding and Japanese VV compounding of pattern A also exhibit the complete identification of their argument structures and lexical semantic features. In contrast, this property is absent from Japanese VV compounding of pattern B.

4.2.2. Pattern A, Endocentric Coordinate Compounding

Yonekura et al. (2023, p. 231) suggest that pattern A belongs to the co-synonymic type of dvandva, drawing on the established recognition that pattern A combines semantically and grammatically similar native verbs such as nak(u) ‘cry’ and sakeb(u) ‘scream’ (Yumoto 2005, pp. 111–12). However, for us, this observation indicates that pattern A is like appositive compounding. As observed in (2), the components of singer-songwriter simultaneously refer to a single individual, and the same holds true of actor-author. In other words, the two nouns of appositive compounds are predicated of an identical subject. Let us consider the following copular constructions:

In (28a), John is a singer and a songwriter, and crucially, in (28b), the same predication applies to Sue and Ken, respectively; the reading in which Sue is a singer and Ken is a songwriter is unacceptable. This observation suggests that singer-songwriter and the like are single complex predicates that are predicated of one subject entity. The argument structures of the input predicates are synthesized into one, and in this respect, they are similar to stir-fry, blow-dry, and slam-dunk (Section 4.2.1).

| (28) | a. | John is a singer-songwriter. |

| b. | Sue and Ken are singer-songwriters. |

When merging two nominal predicates such as singer and songwriter, the Principle of Coindexation works as follows: the subject argument of the predicate singer is coindexed with that of the predicate songwriter. At the same time, the so-called body features, which are bundles of semantic features that each represents bits of encyclopedic information about singers and songwriters, are also merged into one. These processes produce the predicative appositive compound shown in (28).

Now, significantly, this point extends to Japanese VV compounds of pattern A because the component verbs of pattern A always share the same subject. When transitive, they share not only the subject but also the object. Thus, in (17a), naki-sakeb(u) describes a single event performed by a single subject; that is, crying and screaming are simultaneously performed by an identical subject. The two subevents cannot take different subjects, such that the entire construction would express the coordination of two subevents performed by different individuals (e.g., Taro crying and Hanako screaming). In the examples omoi-egak(u) and koi-sitaw in (17a) and nare-sitasim(u) in (17b), the component transitive verbs show not just the identification of their subjects but complete identification of their all arguments. As shown by the acceptable and unacceptable (*) readings in (29), the two component events of pattern A cannot be associated with different agents.

The complete absence of the one-to-one distributive reading indicates that pattern A coordinate compounds, whether durative or punctual, denote a single event that is temporally homogeneous or internally undifferentiated. In other words, the two component verbs form a single complex predicate in which the events they describe are semantically synthesized into one.

| (29) | a. | Nonrepetitive durative | |||||||

| Taro | to | Hanako | wa | nizikan | naki-wameita | ||||

| and | top | two hours | cry-scream.pst | ||||||

| (i) | ‘Taro and Hanako cried and screamed for two hours.’ | ||||||||

| (ii) | *‘Taro cried and Hanako screamed for two hours, respectively.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Punctual | ||||||||

| Taro | to | Hanako | wa | (*nizikan) | sono sensei | ni | nare-sitasinda | ||

| and | top | two hours | the teacher | dat | get used-grow intimate.pst | ||||

| (i) | ‘Taro and Hanako got to know and like the teacher.’ | ||||||||

| (ii) | *‘Taro got used to the teacher and Hanako became intimate with her.’ | ||||||||

Concretely, the process combines two synonymous intransitive or transitive verbs, as shown by the following reorganized list of the examples in (17):

| (30) | a. | naki-sakeb(u) | intransitive + intransitive |

| cry-scream | |||

| ‘to cry and scream’ | |||

| naki-wamek(u) | |||

| cry-scream | |||

| ‘to cry and scream’ | |||

| ukare-sawag(u) | |||

| be excited-be noisy | |||

| ‘to be noisy’ | |||

| hikari-kagayak(u) | |||

| shine-shine | |||

| ‘to shine’ | |||

| ake-kure(ru) | |||

| (day) begin-(day) end | |||

| ‘to spend all one’s time doing’ | |||

| b. | omoi-egak(u) | transitive + transitive | |

| think-picture | |||

| ‘to imagine’ | |||

| nageki-kanasim(u) | |||

| lament-be sad | |||

| ‘to mourn’ | |||

| tae-sinob(u) | |||

| bear-endure | |||

| ‘to bear’ | |||

| koi-sitaw | |||

| long for-adore | |||

| ‘to long for, to miss deeply’ | |||

| imi-kiraw | |||

| avoid-hate | |||

| ‘to detest’ | |||

| odoroki-akire(ru) | |||

| be surprised-be appalled | |||

| ‘to be surprised’ | |||

| nare-sitasim(u) | |||

| get used to-get friendly | |||

| ‘to get used to and like’ | |||

In group (30a), the subject argument of the head is identified with that of the non-head. In this respect, the same mechanism underlies the production of predicative appositive compounds and intransitive pattern A compounds. It will proceed as follows:

The bracketed representations in (31) are skeletons; the italicized variables are arguments, while x=i stands for the fact that the two arguments are co-indexed.

| (31a) appositive coordinate compound (for the predicative use)8 | ||

| [+material, +dynamic (x)] | + [+material, +dynamic (i)] | → [+material, +dynamic (x=i)] |

| Body | Body | synthesized Body |

| singer | songwriter | singer-songwriter |

| (31b) intransitive pattern A compound | ||

| [+dynamic (x)] | + [+dynamic (i)] | → [+dynamic (x=i)] |

| Body | Body | synthesized Body |

| naki- | sakeb- | naki-sakeb- |

The verbal compounding for group (30b) shows not only the identification of the subject argument of the head verb with that of the non-head verb (x=i), but also the identification of the object arguments (y=j):

Nevertheless, in all the cases in (31a–c), we observe the complete identification of the arguments of the components. It is also in this respect that these NN/VV coordinate compounds differ minutely from the subordinate and modificational NN/VV compounds.9

| (31c) transitive pattern A compound | ||

| [+dynamic (x, y)] | + [+dynamic (i, j)] | → [+dynamic (x=i, y=j)] |

| Body | Body | synthesized Body |

| omoi- | egak- | omoi-egak- |

In sum, there are empirical and theoretical reasons to believe that pattern A coordinate compounding is a verbal counterpart of the appositive coordinate compounding. The same analysis would encompass certain A+A combinations, including the apparently mysterious English compound old-new in the following passage (Crystal 2019, p. 72; brackets and underline ours):

As Osamu Koma rightly pointed out (personal communication, March 2023), old-new in (32) is puzzling because the antonymic opposites do not constitute an exocentric dvandva such as those in (5). Rather, the underlined expression says that something is old and new at the same time. If so, in this case, the antonyms are compounded by the same mechanism as appositive and intransitive pattern A compounds.

| (32) | Hearing the play in OP [Original Pronunciation], according to Ben, offered a new auditory experience of an old play that neatly complemented the ‘old-new’ interpretation provided by Richter’s reworking of Vivaldi. |

The example in (32) gives us a pause about a fundamental aspect of our topic because it shows that it is not the lexical semantics of the component lexemes that ultimately determines which type, appositive/pattern A or dvandva/pattern B, coordinate compounding produces. If this were the case, the observed use of old-new in (32) would remain unexplained. Rather, it is the process of compounding that matters, and if it occurs according to the Principle of Coindexation, then even a coordination of antonymic opposites will produce the same type as appositives and pattern A compounds. On the other hand, the same inputs will produce the other type of coordinate compound when the underlying process is different from what we have seen in this section.

4.2.3. Pattern B, Exocentric Coordinate Compounding

Pattern B clearly differs from the types discussed above, i.e., the stir-fry type, appositive compounds, and Japanese VV compounds of pattern A, in exhibiting the following semantic ambiguities:

The sentences above contain the adverb ikkai ‘once’, so here, the habitual or repetitive reading characteristic of pattern B is turned off. Instead, these sentences describe a one-time event that is anchored to a particular spatiotemporal point. We observe three readings for each sentence, (i), (ii)(a), and (ii)(b).

| (33) | Taro | to | Hanako | ga | ikkai | agari-sagari | sita | |

| and | nom | once | ascend-descend | do.pst | ||||

| (i) | ‘Taro and Hanako ascended and descended together.’ | |||||||

| (ii) | (a) ‘Taro and Hanako each ascended and descended.’ (b) ‘Taro ascended and Hanako descended (or vice versa).’ | |||||||

| (34) | Yamada huuhu | ga | ikkai | sono omoi mado | o | ake-sime | sita | |

| husband-wife | nom | once | the heavy window | acc | open-close | do.pst | ||

| (i) | ‘Mr. & Mrs. Yamada opened and closed the heavy window together.’ | |||||||

| (ii) | (a) ‘Mr. & Mrs. Yamada each opened the heavy window and closed it.’ (b) ‘Mrs. Yamada opened the heavy window and Mr. Yamada closed it (or vice versa).’ | |||||||

The first reading, (i), emerges when the coordinated subject, either a syntactic coordination (33) or dvandva compound (34), refers to a set. Conjunctive coordinators have the function of group formation (Hoeksema 1988). When this function of the coordinator to ‘and’ is active, the subject phrase Taro to Hanako ‘Taro and Hanako’ refers to a group, just like English group names such as Tom and Jerry and Simon & Garfunkel; hence, the “doing it together” readings arise.

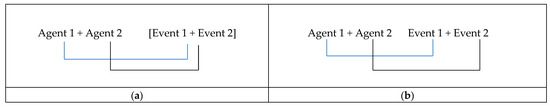

As predicted, when the coordinated subjects are not subject to group formation, “not together” or distributive readings emerge. Indeed, as shown in (33) (ii), the sentence can describe Taro and Hanako separately. Crucially, though, in this case, not only (a) the reading that Taro and Hanako each ascended and descended, but also (b) the reading that Taro ascended while Hanako descended is possible. Figure 1 roughly schematizes the semantic ambiguity in (33) (ii).

Figure 1.

The ambiguity of sentence (33) (ii) when the coordinate subject is not a group. (a) ‘Taro and Hanako each ascended and descended’. (b) ‘Taro ascended while Hanako descended’.

Returning to the comparison between pattern A and pattern B, we emphasize that the one-to-one distributive reading is restricted to the latter type. As we observed in (29), such a reading is systematically absent from pattern A. Moreover, although this is not limited to the coordinated-subject construction, the events described by the component verbs in pattern B need not be temporally adjacent. That is, the sentence in (34), for example, is compatible with situations in which the window in question is opened in the morning and then closed in the evening. These observations support our view that pattern B compounds are composed of separable similar internal units.

How can we explain these observations? In Section 2.2, we saw that dvandva compounding extrinsically adds the feature [+CI] to the semantic contributions of the component lexemes (see (15)). For example, the additive dvandva in (34), huu=hu ‘husband and wife’, has the following complex skeleton:

The dvandva compound huu=hu is exocentric precisely because there is no overt morph matching with the added feature [+CI].

| (35) | [+CI ([ ] | [+material ([ ])] | [+material ([ ])] )] |

| ‘husband’ features | ‘wife’ features | ||

| huu | hu |

The next issue is the Principle of Coindexation (27). As Lieber (2009, p. 91) points out, the referential arguments of dvandva compounds cannot be coindexed because huu ‘husband’ and hu ‘wife’ refer to different individuals. There is nothing that can be simultaneously a husband and a wife, nor is there anything that stands in between the two categories. If so, the obvious conclusion is that the process of coindexation simply does not occur in this type of compound. Rather, the reference of each noun is individually linked to the [+CI] feature; hence the collective reading.

This analysis can be applied to Japanese coordinate compounds of pattern B without any additional stipulations. As argued in Section 4.1, pattern B belongs to dvandva compounding. As a property of this type of compounding, the two coordinated verbs do not undergo the process of coindexation. Rather, their argument structures are individually linked to the [+CI] feature. From this point, several readings emerge, including the habitual/repetitive reading observed in (21), the separate event reading observed in (22a), and the one-to-one distributive readings observed in (33-34) (ii) (b).

As mentioned at the beginning of this section, exocentric compounding is divided into the subordinate, modificational, and coordinate types (Scalise and Bisetto 2009); thus, pickpocket, cutpurse, etc., belong to the subordinate type, airhead, hardhat (‘a reactionary or conservative person’), etc., belong to the modificational type, and dvandvas represent the coordinate type. Drawing on Lieber’s (2016a, pp. 51–52) metonymy-based analysis, it is possible to view the subordinate and modificational exocentric compounding as a multitasking process, in which (i) the usual compounding governed by the Principle of Coindexation and (ii) an extrinsic feature addition process are carried out simultaneously. In this framework, dvandvas, or coordinative exocentrics, are special just in that the first of the two processes is sloppy. We consider dvandva formation to be an exocentric compounding characterized by the addition of the [+CI] feature to the entire representation, but within which N1 and N2 or V1 and V2 are not coindexed with each other. The two components are individually linked to the [+CI] feature. Ultimately, this would be the reason why the two components of dvandvas, including pattern B compounds, are more or less independent of each other phonologically, semantically, and syntactically.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this paper has considered the parallelism between binominal and biverbal constructions in coordinate compounding. On the empirical side, it has been shown that the appositive-dvandva distinction is possible among VV compounds. While this paper has focused on NN and VV, the same seems to hold for AA coordinate compounding, considering examples such as (5) (dvandva) and (32) (non-dvandva). On the methodological side, hurdles in comparing NN and VV compounds that necessarily arise from syntactic-category-specific constraints can be overcome by taking advantage of a set of semantic features and the decomposition method that uses them. On the other hand, this paper remains agnostic about one of the traditional concerns, namely the exact positioning of the constructions under study on the word-phrasal constructional boundary. For example, Japanese coordinate compound nouns in the native lexical stratum phonologically deviate from subordinate and attributive counterparts, and some scholars attribute the deviation to an above-X0 status. Of course, the interaction between syntax and morphology is yet another important issue that spans binominal and biverbal lexical constructions (Kageyama 1993, 2009; Matsumoto 1996; Fukushima 2005; Nicholas and Joseph 2009; Kiparsky 2010; Ralli 2013; Masini and Thornton 2008; Koliopoulou 2014; Spencer 2019; Masini et al. 2023; Yuhara, forthcoming), but the aim and results of the present investigation are independent of this long-standing debate and the final verdict on it.

Author Contributions