Abstract

Human communication is a multimodal phenomenon that involves the combined use of verbal and non-verbal signs. It is estimated that non-verbal signs, especially paralinguistic and kinesic ones, have a significant impact on message production. Silence in Spanish has been described as a plurifunctional communicative resource whose meanings vary depending on contextual, social, and cultural factors. The pragmatic and sociolinguistic nature of this phenomenon calls for examining each case considering the context, the social variables, and the relationship between participants. The aim of this study is to determine the use of silence in Spanish by young women. To achieve this, a corpus of 9 h of spontaneous conversations among six young Spanish university women (1.5 h per participant) was analyzed. The analysis has allowed identifying, first, a series of communicative functions of silence produced by the participants. A relationship between the duration of silence and its communicative function has also been established. Finally, differences in the use of silence by the participants have been found, determined by the interlocutor (male/female), which confirms that women use silence as a basic interactive strategy differently when talking with women and when they do so with men.

1. Introduction

The communicative value of silence in oral interaction, its interpretative ambiguity, and its plurifunctionality are the three main elements of consensus within the long tradition of linguistic research on silence, as an essential nonverbal element in human interaction. Due to the difficulty involved in its systematization, interpretation, and vast intercultural variability, the notion of silence as absence, as the opposite of eloquence, has been emphasized from different perspectives, often comparing it with the power of logos and associating it with scarcely communicative and even impolite or negative meanings. In this paper, we consider silence not as an omission, but as an action, as a nonverbal sign of a pragmatic character that is consubstantial to conversation and belongs to the paralinguistic system, whose meaning is neither assumed nor taken for granted, but interpreted in the broader context of interaction (Jaworski 1993, 2018; Poyatos 1994, 2002; Kurzon 1997, 2018; Ephratt 2008, 2022; Cestero-Mancera 2000, 2019; Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2014a; Méndez-Guerrero 2014, 2024). Specifically, following Cestero-Mancera’s (2014, p. 142) proposal, we include silence in the group of paralinguistic regulators, along with pauses, and define it as an absence of speech equal to or longer than 1 s that appears in interaction and is used to communicate (Knapp 1980; Poyatos 1994; Cestero-Mancera 1999; Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013a; Méndez-Guerrero and Camargo-Fernández 2015; Méndez-Guerrero 2023).

Since the middle of the last century and from different currents of the analysis of human communication, numerous investigations on silence have highlighted the im-portance of the cultural, contextual, social, political, anthropological, and psychological factors linked to its production and interpretation (Hall 1959; Basso 1970; Bruneau 1973; Jensen 1973; Sacks et al. 1974; Knapp 1980; Tannen and Saville-Troike 1985; Sperber and Wilson 1986; Gal 1989; Castilla del Pino 1992; Gallardo-Paúls 1993; Jaworski 1993; Bilmes 1994; Poyatos 1994; Kurzon 1997; Huckin 2002; Cestero-Mancera 2006; Escandell-Vidal 2006; Nakane 2007; Ephratt 2008; Contreras-Fernández 2008; Wharton 2009; Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013a; Schröter 2013; among others).

In the past decade, research on silence in human communication has greatly di-versified its focus and continues to expand today, to the point that some authors speak of this impulse as “a turn to silence” (Murray and Durrheim 2019). Indeed, the works devoted to silence in the last ten years cover aspects as diverse as the establishment of a taxonomy capable of accounting for its multiplicity of meanings, its perception and use in colloquial and multimodal conversation (Méndez-Guerrero 2013, 2014, 2015a, 2015b, 2016a, 2016b, 2017, 2023, 2024; Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2014a, 2014b); the relationship between absence and silence in public discourse from the perspective of critical discourse analysis (Schröter and Taylor 2018); its representation and interpretation as a sign in political practice and management (Brito-Vieira 2020); its characterization, from bioacoustics and psychoacoustics, as a complex perceptual experience triggered by the sensation of auditory emptiness (Rodríguez-Bravo 2021; Torras i Segura 2023); its impact on communication and media during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mateu-Serra 2021; Poyatos 2021); its appearance and meaning in ethnographic oral narratives of women when they talk about their health (Company-Morales et al. 2022); its function and meaning in oral narratives of a corpus of semi-directed interviews (Reyes-O’Ryan and Guerrero forthcoming); the fruitful and current line on its interpretation in work meetings and the workplace (Saintot and Lehtonen 2023); as well as updates on the role of silence in communication, oral and written, from the perspective of iconicity, semantics, semiotics, pragmatics, phonetics, syntax, grammar, and poetics by classical scholars in the field (Ephratt 2018, 2022; Jaworski 2018; Kurzon 2018).

From the multimodal perspective of language, silence has been understood as a communicative element that appears in discourse in concomitance with other verbal and nonverbal signs, contributing functions, values, or nuances to those already expressed by other discursive resources (Poyatos 2002). All the signs present in the interaction are part of the communicative continuum in which communicative signs and their functions present relations and family airs among themselves (Méndez-Guerrero 2014). According to this positioning, words, gestures, and silences, among others, not only appear together in communication, but are elements that can be chosen among all those that represent a communicative function and, sometimes, are interchangeable once the nuances provided by each of them have been weighed. The decision to use one resource or another will depend on the appropriateness of the sign to the context, its capacity to express all that the speakers wish to communicate, their identity and communicative style, and the reaffirmation or transgression they wish to make of them (Méndez-Guerrero 2024).

The relationship between gender and silence in oral interaction has also been explored from the angles of conversation analysis, ethnography of communication, sociolinguistics, and discourse analysis, highlighting the different meanings and forms of management of turns of speech, interruptions, and silences by men and women, as well as the influence of social and contextual factors on such management (Zimmerman and West 1975; Fishman 1978, 1980; Gal 1989; DeFrancisco 1991; Tannen 1993, 2005; Cestero-Mancera 2000, 2007; Bengoechea-Bartolomé 1993, 2003; García-Mouton 2003; Camargo-Fernández 2010; Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013b; Acuña-Ferreira 2009, 2015; Méndez-Guerrero 2014, 2015b, 2017). In the face of the commonplaces, which are contradictory and variable according to culture, that either women are condemned to silence by men, or that they are incapable of being silent and, therefore, their most valuable attribute is silence, the aforementioned empirical studies have shown a very varied casuistry that is far removed from the clichés regarding the use and functions of silence by women.

Nevertheless, there are still very few studies that systematize the relationship be-tween silence and the gender variable in Spanish using data from corpora of real con-versations that allow us to classify, quantify, and compare its functions when women speak with other women and when they speak with men. The aim of this article is, therefore, to establish a pragmatic taxonomy of the silences recorded in a corpus of spontaneous conversations of 9 h’ duration (1.5 h per informant), the Corpus oral juvenil del español de Mallorca (COJEM) (Méndez-Guerrero 2015a), in which three women talk with other women and another three do so with men. Based on the durations and frequencies obtained in each case, certain functions of silences in the different types of interaction (female vs. mixed conversations) will be proposed. The results will be analyzed using the dynamic approach to the relationship between language and gender (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2003) and the dynamic theory of silence (Méndez-Guerrero 2014, 2023). In this way, it will be possible to ascertain whether silence in conversation is a basic interactional strategy in women that presents functional or duration differences in feminine and mixed exchanges in each context and whether these differences are deter-mined by the type of speaker and by the social relationship.

2. A Dynamic Approach to the Study of Gender and Silence

The relationship between gender and conversational style was studied during the last decades of the twentieth century using the so-called domination theory and difference theory, which constitute the two main approaches to the study of the differences between men’s and women’s ways of speaking. The first is based on the idea that language is a set of structures that support male power—a reflection of a vision resulting from the established patriarchal order—that interpret the masculine as the normative (Lakoff 1975); the second proclaims that women and men learn different behaviors as part of their socialization process and that, as a result, women have a more cooperative and different conversational style than men, who are prone to conflict (Coates [1986] 2016; Tannen 1990; Sheldon 1993; Cameron 2005). On a biological level would be the theories of those who argue that the differences between the ways that men and women talk are due to biological factors that provide better verbal skills to women (Chambers 2003).

The differences between female and male conversational styles have been studied from various perspectives, among which we highlight those that have focused on real interactions between men and women in informal contexts. Such is the case of the work of Pamela Fishman (1977, 1978, 1980), who analyzed the interactions in three white heterosexual couples’ homes. The results of her works indicate that women made more efforts to initiate and maintain conversations, but always with less success than their partners. Often, husbands responded uncooperatively with monosyllabic turns, interruptions or delayed responses, whereas on other occasions, their questions went unanswered (‘no response’ violation), resulting in silence. Overall, male conversational behavior was characterized as uncooperative, focused on maintaining control of the interaction and topics, as well as preserving the conversational floor. Fishman’s (1977) line is that women take care of the ‘interactional shitwork’, which is something that is connected to the household tasks that have traditionally been assigned to them. Likewise, this author suggests that for women to be socially acceptable as women, they cannot exert social control, but rather that they must support male social control.

Other studies have delved deeper into this line of research, indicating that women are more polite than men in conversation (Holmes 1995), both in terms of negative politeness, which recognizes the autonomy of others and avoids intrusive behavior, and in terms of positive politeness, which emphasizes connection and bonding (Brown and Levinson 1987). Women tend to be more facilitative in conversational interaction, with their conversational goals and strategies focusing on establishing an affiliation with their interlocutor, gaining trust, sharing confidence, and building rapport, thus emphasizing solidarity in relationships (Coates [1986] 2016; Holmes 1995). By contrast, they attenuate criticism and avoid reproach, while giving compliments and expressing appreciation (Troemel-Ploetz 1991). By contrast, men tend to use language to mark status and to obtain or convey information (Aries and Johnson 1983; Tannen 1990). Their conversations are organized around mutual activities rather than towards relationship maintenance (Aries and Johnson 1983), and compared to women’s conversations, they are more likely to involve boasting, verbal jousting, and mutual insults (Holmes 1995). Men tend to talk more than women, at least in formal or public situations (Holmes 1995), but they have been found to talk less in intimate relationships (Fishman 1978) and to show a greater tendency toward silence (DeFrancisco 1991). They show delayed minimal responses (Zimmerman and West 1975) and less eye contact with the interlocutor when listening, both of which may be perceived by the speaker as signals of lack of interest in what is being said. In summary, and compared to women, men tend to use less polite forms of speech, do not apologize as readily, and are perceived as less facilitative conversational partners.

Such theories explain the conversational behavior of men and women as opposites, but as equally homogeneous, and were criticized for offering a binary view of women and men as members of different social and symbolic spheres (Bucholtz 2014). As a consequence, they were gradually replaced by other approaches, such as the interactional perspective (Tannen 1993, 2005) and the dynamic approach (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 1992, 2003). The first perspective posits that differences between men’s and women’s discourses must be found within the communicative process and not as the result of established and predetermined categories. The second considers the communicative differences between genders as a complex and fluid social construct that is negotiated in interaction and in the so-called communities of practice (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 1992, 2003). Thus, there would not be a single form of expression (feminine or masculine), but a series of more or less indicative styles of different identities that speakers choose, depending on the sociosituational context, in order to represent the identity they wish to convey.

The shift from binary and biologistic theories to interactional and dynamic approaches in studies of the relationship between language and gender runs parallel to the need to explain the complexity of power relations and solidarity in interaction. Still, as Hal et al. (2021) exposed, the vast majority of contributions from both streams were based on studies of predominantly white, heterosexual, cisgender, middleclass, English-speaking speakers. Moreover, as Susan Gal (1989, 1995) pointed out in her works, previous research in the field did not consider the symbolic dimension that motivates the use of certain linguistic features, such as the conversational silences discussed here, and thus did not study language as a resource for the expression of power and identity. Gal’s (1989) pioneering work on the relationship between silence and gender already emphasized that even seemingly small details, such as systematic differences between American boys’ and girls’ turns of speech in same-sex playgroups, fit into and reinforce the broad cultural logic of gender symbolization in the United States. However, women’s conformity to such cultural expectations is neither passive nor automatic. In fact, as will be demonstrated in this paper, women actively construct their identities, consciously choosing among possible linguistic strategies (Reyes 2002) in response to these cultural conceptions and the unequal gender relations they encode in the different communities in which they interact.

In addition to the dynamic approach of Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (1992, 2003) that contemplates the symbolic and conscious dimension of linguistic choices (Gal 1989, 1995; Reyes 2002), we adopt in this work the dynamic approach to silence (Méndez-Guerrero 2014, 2023). This theory explains silences as part of a connected and changing discourse and considers that each silence alters and is altered by all the linguistic and extralinguistic elements that appear alongside it, which must be considered in order to reach an adequate interpretation of both verbal and nonverbal signs. The key lies in unraveling its potential capacity to condition and be conditioned by the context in which it appears and its ability to connect with other parts of speech. To access the meaning of silent acts, therefore, the listener to silence in a conversation must handle (in addition to the sociosituational context) all the cognitive processes and prior and shared knowledge at his or her disposal. Therefore, achieving a connection between new and already known information leads to success in the inferential process and access to what is implied silently. The fact that the interpretation of silence is considered a dynamic process is also related to the fact that the interpretation of silences is open to diverse meanings that are negotiated in each utterance:

In short, the most appropriate and relevant pragmatic meaning in each context will result from a dynamic process that is not built only from previous assumptions and whose possible pragmatic ambiguity will be resolved using the situation and the environment in which the absence of speech occurs. Hence, a disambiguation exercise (based on the evaluation of the context, the social relationship and the common cognitive environment) is necessary to solve ambiguity and polyvalence, now classic problems of silence in conversation. Misunderstandings, therefore, will arise where the listener has not been able to carry out that mental process or has not wanted to do so.(Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2014b, p. 36)

Adopting this approach to analyze the relationship between silence and gender will allow us to observe how men and women interact not as individuals and in static and predictable ways, but in institutions such as workplaces, families, friendship groups, schools, and political forums, where much of the decision making about resources and social selection for mobility occurs through speech. Additionally, institutions are far from neutral: they are structured along gender lines, to grant authority not only to reigning classes and ethnic groups, but specifically to male linguistic practices to which women of-ten react verbally and nonverbally.

3. Materials and Methods

The corpus used in this sociolinguistic study on women’s silences comprises 9 h of recordings from six conversations held by young Spanish women born in Mallorca, with higher university education and Spanish as their native language. All of them share a very close social relationship and have been friends for years. Specifically, there are six recordings, each lasting 90 min, in which three informants talk with women and three informants talk with men. Sampling was intentional, eliminating the random factor, among members of a compact and specific community of practice (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2003): young female university students under 25 who talk with friends.

The recordings belong to the Corpus oral juvenil del español de Mallorca (COJEM) (Méndez-Guerrero 2015a) and were conducted in Palma during the spring of 2011 using the covert recording technique and participant observation. Once the recordings were collected, all informants were requested to provide their corresponding authorization, stating that these samples would be part of a linguistic study, and the recorded material was made available to them. All gave their consent. On the issues arising from collecting linguistic corpora with a hidden recorder, refer to Milroy and Gordon (2003). At least one of the analysts in this study was present at all recorded communicative encounters and is part of the community of practice under study. The intention was to understand firsthand the norms, values, and linguistic and social patterns of the speakers’ group so as to assign a value, possibly shared by the entire community of practice, to each silence. The aim of selecting speakers with such a close social relationship is to obtain exchanges as informal, natural, and spontaneous as possible.

Data were collected in places frequented by speakers (cafés, homes, and private vehicles). All encounters took place completely freely, naturally, and spontaneously, with no intention of organizing or directing the conversation at any point. The participants’ goal, as often, was to gather for friendly conversation, so the topics recorded in the samples are related to various personal (work, family, academic) or current affairs issues (politics, sexism, economy, society …). The informants analyzed in the study are six women under 25 years of age with university studies. All of them maintained a very close friendship with their interlocutors. Three of them spoke with women and three of them spoke with men. A minimum of two participants and a maximum of four participants participated in the conversations and all of them were informed of the experiment.

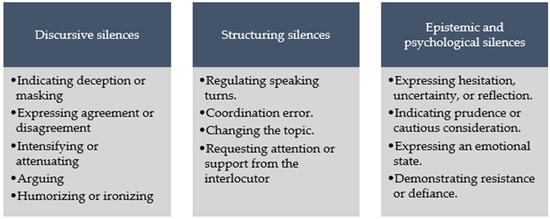

Conversations were fully transcribed following the conventions of the PRESEEA Corpus (Moreno-Fernández 2021), and from these transcriptions, the durations and frequencies of all silences recorded during the 9 h constituting the corpus were coded and measured. For the coding and treatment of silences, a pragmatic taxonomy was developed, based on previous studies that captured the main communicative values assigned to silence in Spanish culture. This taxonomy can be consulted in the Results section, in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of communicative functions of silence in Spanish (Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013a).

This work aims to test this classification through a qualitative analysis that describes the pragmatic categories of silence (Section 4.1) and through a quantitative analysis (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3) that describes its frequencies. With studies of this kind, we believe it is possible to establish, with certainty, a typology of the communicative functions of the most common silent acts in Spanish conversation that can be applied to other groups of speakers. As a preliminary step to the analysis, all silences in the corpus (speech absences of at least 1 s in duration) were isolated. In total, 220 silent acts produced by the six informants in the study were recorded. To separate and assign functions to silences, we relied, as mentioned, on the typology established by the authors in previous studies that assigned different discursive, structuring, or epistemic and psychological values to silences, making them closer to one or another pragmatic function (Figure 1). All these functions were later organized into tables, facilitating the coding of the recorded cases.

For acoustic treatment and data analysis, the PRAAT and SPSS programs were used, respectively. The analysis had two clearly defined phases: (1) the quantitative description, to present and summarize the data and make estimations of significance and reliability (frequency, mean, standard deviation, and variance) and (2) statistical tests, to make estimations about the connection between various variables (chi-square (X2) and p-value), collecting the main communicative values assigned to silence in Spanish culture.

As a control group, a group of young women from the Val.Es.Co. corpus (Pons-Bordería 2023) has been used. This corpus, like COJEM, collects the colloquial and spontaneous speech of Spanish speakers in the city of Valencia. The sampling technique also coincides with that used in our corpus: secret recording and participant observation.

In the following pages, the absolute and relative frequencies (or percentages) of the pragmatic functions of silence produced by the informants when interacting with women and when interacting with men will be described first, along with the durations of silences in conversations between women and in mixed ones. Next, the variance and standard deviation of the collected data will be discussed to understand the dispersion or variation of these regarding the mean frequency and mean duration of silences established at the beginning of the analysis. Finally, a statistical analysis will be carried out based on the hypothesis that there is a correlation between the frequency, pragmatic functions, and durations of silences in the silent acts of young Spanish women in their interactions with men or other women. For this, the chi-square test (X2) will be performed, allowing the discovery of the independence or interdependence of the variables under study, considering the p-value (p ≥ 0.05).

4. Results

In this section, we present the main communicative functions of silence used by the community of practice of young female university students from Mallorca engaging in informal conversations with friends. Subsequently, we discuss the overall results of the analysis of the dependent variable (silences) in relation to the social variable of gender in the COJEM conversation corpus (Méndez-Guerrero 2015a). Additionally, we describe the frequencies, functions, and durations of silence, correlating them with the variable of the gender participation framework: women in mixed-gender conversations and women in conversations with other women. Finally, statistical tests are conducted to measure the level of significance between the studied variables.

4.1. Taxonomy of the Communicative Functions of Silence

The data analysis reveals that Spanish women use at least three types of silences in conversation: discursive silences, structuring silences, and epistemic and psychological silences.

Discursive silences act as discursive indicators guiding speakers’ inferences, giving meaning to the communicative act, and performing pragmatic functions. Within the groups of silences included in this category, there are functions such as indicating deception or concealment, expressing agreement or disagreement, intensifying or attenuating, arguing, humorizing, or ironizing.

- (A)

- Example of an intensifying silence (CE.2.H0;H3) (202–205)1(H0 (woman) and H3 (woman) are friends, they are between 20 and 25 years old. Topic: they talk about how clueless H3 is).H3: ¡madre mía!///(2) ¡Con la de veces que he habré pasado por aquí!///(1) y yo sin fijarme en el garito eseH0: yo alucino contigo/ chica// no puede ser que no lo hayas visto hasta ahora

The silences in (A), with a bold number indicating the duration in seconds of each silence, have a discursive and emphatic character. Their function is intensifying, as they aim to generate greater interest in what is being communicated.

On the other hand, structuring silences adhere to rules or principles that organize or structure the conversation, serving as regulators of speaking turns, intervening when a coordination error occurs, or when requesting attention or support from the interlocutor.

- (B)

- Example of silence used to seek attention and support (CE.3.H0;H4) (400–414)(H0 (woman) and H4 (man) are friends, they are between 20 and 25 years old. Topic: they talk about the difficulties that come with reconciling work life and family life).H0: hombre sí/ madre soltera es complicao el temaH4: ¿vale?/ que lo tengas con alguien// ¿vale?///(1) tu pareja también tendrá que asumir su parte de responsabilidad de hijoH0: sí/ pero reconóceme que casi todo recae en la madreH4: no es verdadH0: venga hombre /H4/ me quieres hacer creer que la mujer no tiene que hacerse cargo del 90% de lo queH4: depende de las circunstanciasH0: además/ yo quiero que mis hijos pasen tiempo conmigoH4: claro claro/ pero depende de las circunstancias// yo que sé///(1) a ver el hijo de Carme Chacón a lo mejor lo cuida más// el padre que Carme ChacónH0: probablementeH4: ¿vale?///(1)H4: o la nani/y yo no quiero tener nani

The silences in (B) serve the purpose of seeking attention or support from the interlocutor. With this, H4 aims to gain or maintain the attention of H0 and solicit their support for the message being communicated.

Finally, epistemic and psychological silences are characterized by a significant psychological, emotional, and cognitive component. Their pragmatic functions include expressing hesitation, uncertainty, prudence, and reflection, and conveying or indicating one’s emotional state.

- (C)

- Example of an epistemic silence (CE.6.H0;H7) (1474–1480)(H0 (woman) and H7 (man) are friends, they are between 20 and 25 years old. Topic: they talk about the price of food abroad).H7: no no/ no/ era otra cosa que era de: España// no sé por qué/ no/ tomates eran de España/ eran baratosH0: ¿qué llamas barato?// ¿un euro y medio?H7: no/ era más barato que aquí/ no me acuerdo/ no sé/ pero yo es que ahora no compro///(1) no los compro yo ahora///(1) no no sé a qué precio están ahora///(1) los de “ramallet” son carísimos/ pero allí no había///(4)H0: qué curioso

In (C), it is evident how H7 hesitates in the message being conveyed because they are unsure, at least partially, about the information they are providing to their interlocutor.

In the following sections, we will proceed to explain the main results of the study.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

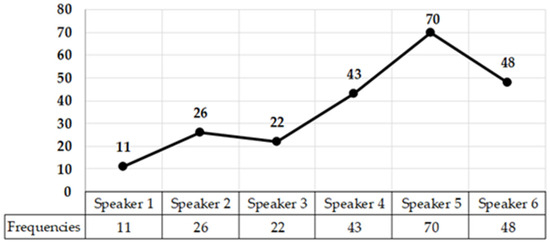

In the conversations of the six informants, a total of 220 silences were observed. The recorded frequencies range from 11 to 70 silences per informant (with a mean of 36.6). The silence within the women’s group exhibits a high variance (377.8) and a standard deviation (453.4) considerably above the mean. This indicates that the frequency of silences among the women of the corpus is very heterogeneous. As will be seen, this apparent disparity is partly related to the gender of the interlocutor. In cases where the women in the study talk with men (speakers 4, 5, and 6), more silences occur than when they talk with other women (speakers 1, 2, and 3) as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Absolute frequencies of the silences in the corpus.

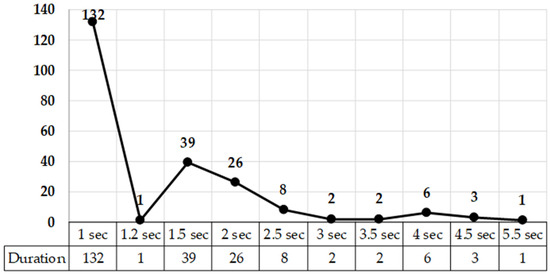

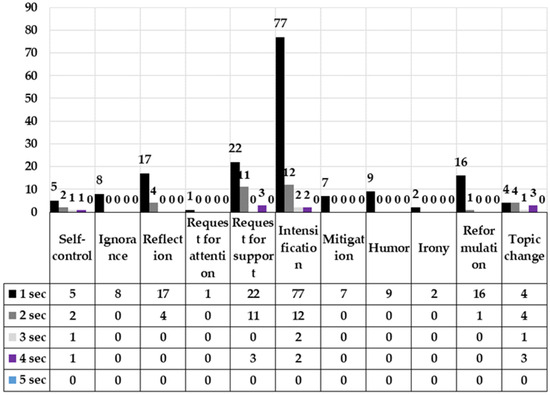

Regarding the duration of the silences, there are speech absences ranging from 1 s to 5.5 s (with a mean of 1.45 s) as seen in Figure 3. However, in these instances, the variance (2.0) and standard deviation (1.5) are very small, indicating that the durations of silences produced by the informants are very consistent. Specifically, of the 220 cases comprising the sample, 132 (60%) last only 1 s, and 40 last between 1.2 and 1.5 s. Therefore, 78.2% of the analyzed silences are shorter than 2 s.

Figure 3.

Absolute frequencies of the duration of silences in the corpus.

The pragmatic functions of silence also exhibit different frequencies and durations. It has been observed that some functions have higher production rates (intensification, seeking support, reflection, reformulation, etc.), while others appear less frequently (request of attention, irony, mitigation, etc.). Additionally, some functions described in previous studies, such as deception and concealment, resistance, and coordination errors, do not appear in this analysis. The lack of representation in the samples of some pragmatic functions of silence proposed in other studies can be attributed to the highly informal nature of conversations among speakers with a high degree of familiarity. In these situations, speakers might choose other verbal or non-verbal communicative strategies to express, for example, disagreement, resistance, or challenges.

Variation is also evident in the durations. On the one hand, there are functions with average durations between 1.0 and 1.5 s, such as silences for irony, mitigation, reformulation, humor, reflection, and intensification. On the other hand, there are functions with average durations ranging from 1.5 to 2.5 s, including silences for expressing ignorance, hesitation or doubt, self-control, seeking support, and changing the topic. These details can be observed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequencies, means, variances, and standard deviations of the pragmatic functions of silence.

From the above table, it is inferred that the women in the analyzed corpus exhibit differences in the frequency or usage of their silences, observed in both the duration of silences, although there is a tendency towards shorter silences, and in the pragmatic functions.

When comparing or grouping conversations by gender (interactions between women and interactions between women and men), the results of the study provide more information (see Table 2). Out of the total 220 silences, only 59 (26.8%) occurred in woman–woman conversations, while 161 (73.2%) were recorded in woman–man conversations. Although it is not the intention of this study to describe men’s silence in conversation, it is noteworthy that the three male interlocutors in mixed-gender conversations exhibited silence rates at least twice as large as those of women. Similarly, differences in duration and functions have also been observed between women and men in the COJEM corpus. Therefore, it will be necessary to revisit the comparison between women and men in future studies.

Table 2.

Frequencies of silences in relation to the gender participation frameworks.

The average frequency of silences produced by women when talking with other women is 19.6, which is much less than the average silences of women when talking with men, which is 53.6. In the case of informants participating in woman–woman conversations, a very low variance (40.2) and standard deviation (7.7) are observed, indicating that they all exhibit a similar recurrence of silent acts. Variance (137) and standard deviation (14.3) indices increase, although they are still low, for participants in woman–man conversations. Given this, it is not surprising to find high variance (260.1) and standard deviation (72.1) indices compared to the means when both gender participation frameworks are analyzed.

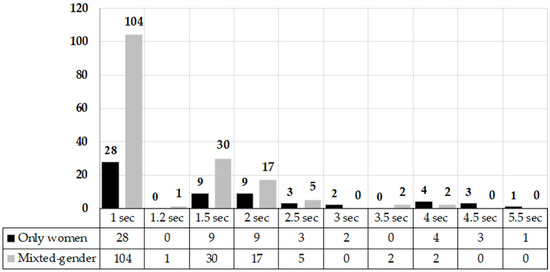

Regarding the duration of silences in different gender participation frameworks, we observe results similar to those described on previous pages. The average duration of silences for informants talking with other women is 1.8 s. The variance (68.7) and standard deviation (8.8) indicate that these are quite homogeneous samples. However, some differences are noticeable between these data and those obtained in mixed-gender conversations. In these cases, the silences of women interacting with men have a slightly shorter average duration (1.3 s), and the variance (119.0) and standard deviation (37.2) indicate that the conversations are, in this respect, very heterogeneous. As mentioned earlier, short silences (between 1 and 2 s) are predominant in both gender participation frameworks. In conversations between women, shorter silences account for 37 cases, equivalent to 62.8% of all those produced by them, while women interacting with men use them in 135 instances, representing 83.8% of the total. The longer duration of silences among women, as will be seen below, is related to the preference in women’s conversations for functions that manifest with longer silences.

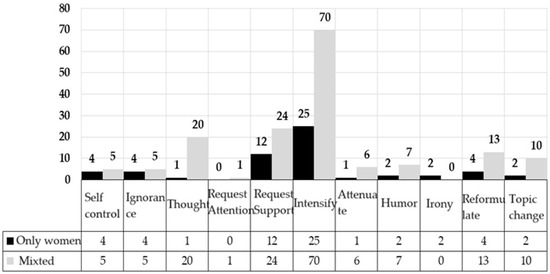

The pragmatic functions of silence In relation to the gender participation framework also reveal important data. The two most common functions of silence in all gender participation frameworks are for intensifying (43.5% in mixed-gender conversations and 42.4% in conversations among women) and for seeking support (26.3% in mixed-gender conversations and 20.3% in conversations among women). However, in conversations with men, functions for reflection (12.4%) or reformulation (8.1%) also prevail, while in conversations with other women, the differences between functions are not as pronounced. Therefore, there seems to be a different performance here when women converse with men and when they converse with other women. As authors like Holmes and Marra (2004) and Holmes (2006) have described, men often make a more transactional use of discourse, oriented toward message transmission rather than toward cooperation and relationship protection between speakers. Also, according to Lozano-Domingo (1995, p. 177), men seem to be more interested in reaffirming or imposing their concepts and conveying a message than women when they are involved in conversation. Hence, they tend to be silent and reflect more on their message to make it clear and understandable. Women, on the other hand, try to fill the gap and avoid silence, using some other element while reflecting on what they are going to say. Thus, following the dynamic theory of silence (Méndez-Guerrero 2014, 2023) presented in the early pages of this work, it could be understood that, in the interaction itself, a set of communicative resources indicative of the identities of the speakers emerges, which the young women in the study decide to use depending on the context of the interlocutor and the identity they wish to convey.

We now compare the analysis that we have just presented with the results obtained with four informants (young women) extracted from the Val.Es.Co. corpus (Pons-Bordería 2023) as a control group. This analysis has been carried out with the intention of reducing the random factor and verifying that the results obtained are not the result of chance and that they are similar to those that can be obtained from another group of young university students in informal conversations with friends. For this, we reviewed a total of 157 fragments in which silences appeared (two complete transcriptions). It is worth noting that the results obtained in this analysis are very similar to those presented in this work. First, we observed that the silences of women are very brief (only 21.6% exceed 2 s). Additionally, among the Val.Es.Co. informants, certain functions can also be more commonly associated with women talking with other women (self-control, attention-seeking, mitigation/softening), and others with women talking with men (ignorance, intensification, reflection, seeking support). This aligns once again with the results of this study.

From the analysis conducted so far, we can conclude that the fact that women in the COJEM corpus talk with men or women influences the frequency of silence’s occurrence, its duration, and the pragmatic functions performed. In mixed-gender conversations, women tend to be more silent, and when they are silent, it is with a more transactional orientation, meaning that their silences are primarily aimed at reinforcing message transmission. On the other hand, when interacting with other women, they are less silent, their intention is more cooperative, and the purpose of their silences is to advance the conversation and protect its well-being. This suggests that there is accommodation on the part of the women in the corpus who talk with men, as in their cooperative and “involving” effort, they adapt to the communicative strategies of their interlocutors. The latter has a series of implications that can be related to the dynamic theory of discourse, according to which the discourse is built on the basis of the context and a constant evaluation occurs in the conversation influenced by the actions of the interlocutor, his or her expectations, and other linguistic and extralinguistic factors.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Based on the described data, significant relationships or associations have been identified among some of the variables under study. First, it should be noted that the gender participation framework (only women or mixed) has an interdependent relationship with the duration of silences: the fact that women talk with other women or with men is linked to the duration of their silent acts (X2 = 19.24 and p = 0.0007) (see Figure 4). However, the aforementioned data cannot be applied to the relationship that the pragmatic functions of silence seem to have with the gender participation framework. In this case, the relationship is one of independence, because it has not been established that the use of silence with certain functions (such as self-control, attention-seeking, or irony) is significantly conditioned by the gender of the interlocutor (X2 = 15.46 and p = 0.07). Nevertheless, some trends are observed that would allow us to speak of a certain interdependent relationship between some of the pragmatic functions and the gender participation framework. This is the case for reflective silences (X2 = 17.19 and p = 0.00003), for seeking support (X2 = 4 and p = 0.04), and for intensifiers (X2 = 21.3 and p = 0.000003) (see Figure 5). The duration and pragmatic functions of silence in the analyzed samples also show a significant interdependent relationship (X2 = 52.68 and p = 0.03) (see Figure 6). Indeed, it has been observed that silent acts tend to have different durations depending on the pragmatic function they perform. The relationships found between some categories and functions with their durations are particularly significant, including silences due to a lack of knowledge (X2 = 27.1 and p = 0.00001), reflection (X2 = 51.6 and p = 0), seeking support (X2 = 49.2 and p = 0), intensification (X2 = 233.92 and p = 0), mitigation (X2 = 28 and p = 0.00001), and reformulation (X2 = 58.5 and p = 0). In other cases, only trends can be discussed, as some of the frequencies used for the analysis are very low and do not allow for definitive conclusions. Therefore, for future studies, it would be advisable to expand the sample to give the analysis greater significance.

Figure 4.

Duration of silence in relation to the gender participation framework (only women or mixed-gender).

Figure 5.

Pragmatic functions in relation to the gender participation framework (only women or mixed-gender).

Figure 6.

Comparison between pragmatic functions of silence and durations.

Finally, a multivariable analysis has been conducted, adding an additional layer to the analysis, aiming to determine if there is a significant relationship between the gender participation framework, duration, and function. Thus, the variables “function,” “duration,” and “gender participation framework” were jointly compared (see Table 3). The results of the variable intersection were as follows: (1) there is an interdependence relationship (X2 = 39.6 and p = 0.05) between the variables, and (2) the highest-frequency indices in the corpus are found in short silences (less than 2 s) produced by young women who talk with men (mixed conversations) that are mainly performed to intensify their discourses, seek support from the interlocutor, or reflect on their message.

Table 3.

Contrastive analysis between gender participation framework–duration–pragmatic function of silence.

For over two decades, the fields of sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, and recent pragmatic studies have been dedicated to studying language as a communicative practice, seeking to understand the social patterns of linguistic activity in different communities of practice (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2003). In this research, we have relied on the idea that the women in the analyzed corpus have their own social conventions—often coinciding with those of other linguistic communities—that are put into practice every day and always with the intention of achieving a goal. In addition to these social conventions, there are also those particular to each conversation (the situational context and the social relationship between participants). In the sample, as just seen, significant differences are observed between when women talk with other women and when they interact with men. This allows us to speak of a distribution of the functions of silence among the women in this corpus in relation to the gender of their interlocutors. In conclusion, it has been observed that grouping conversations by gender (women with women and women with men) and comparing them with the frequencies, durations, and functions of silence allows us to establish trends and some significant differences in the relationship between gender and silent acts. In this way, we have sought to explain, as closely as possible, the functioning of silence in the colloquial conversation of a group of young Spanish women.

5. Discussion

The results of the study show that women strategically use silence differently depending on the interlocutor (male or female). This phenomenon has been explained in the sociolinguistic tradition through the theory of accommodation, which, in the words of Trudgill (1986), involves adjusting linguistic behavior to socially approach or distance oneself from those with whom one is interacting. The Spanish young university women in the study spoke with friends in all cases. Presumably, their goal was to cooperate in the conversation, strengthen bonds, and maintain good relationships with their interlocutors (Holmes and Marra 2004; Holmes 2006). For this reason, they tried to approach their interlocutors, whether men or women, by adopting some of the functions of silence associated with them.

In all analyzed cases, silence was used by Spanish women with short average durations of less than 2 s. This highlights a previously explained fact suggesting that silence in Spanish is typically brief, especially when compared to other Asian or Northern European cultures (Méndez-Guerrero 2023). It has also been demonstrated in this work to have a multifunctional nature, as silence is used in Spanish in informal contexts both to structure conversation and to indicate certain discursive or epistemic and psychological functions. This fact has also been confirmed in the Val.Es.Co. control corpus, which is also informal and was collected through secret recording and participant observation in the city of Valencia, where these functions have also been recorded.

Analyzing a specific community of practice, young university women from Mallorca talking with friends in informal situations, has allowed us to better explain the behavior of the informants. The choice of the sample is based on the fact that recent studies have interpreted speech absences in communicative exchanges among some groups of Spanish young men and women as a habitual communicative resource in their conversations with other young friends, identifying them socially, allowing them to create complicity or affiliations, and strengthening ties with members of their group, as it differentiates them from other groups or communities of practice without harming their social image (Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013b; Méndez-Guerrero 2015b, 2017). The concept of a community of practice has been used in this work as conceived by Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2003), that is, as a group of people who come together around a common commitment for a purpose, and in the course of this common effort, ways of doing things, ways of speaking, beliefs, values, and power relationships emerge, in other words, practices.

In future studies, it will be important to expand the sample studied, since the current one is limited and may not allow generalizations. It will also be important to compare in practice the group of young Spanish university students with similar groups from other regions of Spain to verify possible coincidences. It will also be essential to compare these results with the pragmatic behaviors of men to more accurately define possible similarities and differences between genders. It will be of interest, finally, to determine whether the position of silence in the speaking turn (beginning, middle, or end of the turn) significantly influences the frequency, duration, and pragmatic value or function of silent acts.

6. Conclusions

As demonstrated in this work, silence is a communicative strategy used both to convey information or structure discourse and to express emotions or reflection. It is conditioned by contextual factors and, at least in the context of this study, by the gender of the interlocutors with whom one is talking. We started with the idea that no conversation or communicative act has meaning outside of an interactional framing (Tannen 1993, 2005) and that if differences between the silences of women talking with women and women talking with men occur, they should be found and analyzed within a specific communicative process and not as the result of culturally or biologically established and predetermined categories. However, traditionally, the analysis of women’s speech (and also that of men) has been studied from an impressionistic perspective without a true interpretation of female and male communicative styles. For this study, we focused on a specific community of practice (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2003): young Spanish university women talking with friends in informal contexts.

According to the results of the analysis, it has been observed that, although Spanish culture is not inclined toward silence and predominantly favors speech, this does not prevent silence from appearing in spontaneous daily interactions (Camargo-Fernández and Méndez-Guerrero 2013b). It can also be said that, at least in the analyzed sample, young women resort to silence with different intentions or purposes than men, and the frequency of their silences increases when talking with men. Therefore, it is possible to argue that the uses of silence by the women in our corpus are part of the expression of feminine conversational style. Based on the distinction made between discursive silences, structuring silences, and epistemic and psychological silences, it has been determined that when interacting with men, women in the corpus are quieter, doing so to reflect or reformulate their discourse with a clear purpose of conveying information (more transactional orientation). However, the predominant functions in all cases are for intensification and seeking support. These latter functions are more related to an intention to protect the good state of the conversation and strengthen bonds (more cooperative orientation). This is what Cestero-Mancera (2007) referred to as acts of involvement or “basic structural cooperation strategies in conversation characteristic of women” (Cestero-Mancera 2007, p. 15).

All of the above leads us to conclude, following the idea of the dynamic approach used in this work, that there are a series of communicative resources, including silence as was highlighted by Gal (1989, 1995), related to the construction of one’s identity. Silence, thus, can occur or not in each context depending on the identity that the speaker wishes to convey. In the same line, the results of the analysis also confirm the existence of differences in strategic uses, intentionality, and the duration of silence in women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; methodology, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; validation, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; investigation, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; data curation, B.M.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; writing—review and editing, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; visualization, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F.; funding acquisition, B.M.-G. and L.C.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Comunitat Autonòma de les Illes Balears through the Direcció General de Recerca, Innovació i Transformació Digital, with funds from the Tourist Stay Tax Law (PDR2020/51–-ITS2017-006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that participants in the conversations provided signed consent for the use of anonymized transcripts for linguistic research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The examples are part of the Corpus Oral Juvenil del Español de Mallorca (COJEM) (Méndez-Guerrero 2015a).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | The examples are part of the Corpus Oral Juvenil del Español de Mallorca (COJEM) (Méndez-Guerrero 2015a). In each example, only the silences highlighted in bold will be analyzed. The way in which we will present the silences will be as follows: three bars and a number in parentheses that indicates the seconds that the silence lasts: “///(2)” = silence lasting 2 s. The rest of the silences will be represented in the same way as the text. Finally, pauses (speech absences of less than one second) will be represented with a double slash: //. Additionally, (:) will be used to indicate lengthening, an underline for overlaps, and (?) for uncertain passages of the recording that could not be transcribed. Informants will be represented with “H” followed by a number. |

References

- Acuña-Ferreira, A. Virginia. 2009. Género y discurso: Las mujeres y los hombres en la interacción conversacional. Munich: Lincom Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña-Ferreira, A. Virgina. 2015. El lenguaje y el lugar de la mujer: Sociolingüística feminista y valoración social del habla femenina. Tonos Digital 28: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aries, Elisabeth, and Fern L. Johnson. 1983. Close friendship in adulthood: Conversational content between same-sex friends. Sex Roles 9: 1183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, Keith H. 1970. To give up on words: Silence in Western Apache culture. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 2: 213–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoechea-Bartolomé, Mercedes. 1993. El silencio femenino. REDEN: Revista Española de Estudios Norteamericanos 5: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bengoechea-Bartolomé, Mercedes. 2003. Influencia del uso del lenguaje y los estilos comunicativos en la autoestima y la formación de la identidad personal. Gasteiz: EMAKUNDE. Instituto Vasco de la Mujer. Available online: http://intercambia.educalab.es/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/MERCEDES-BENGOECHEA-Uso-del-lenguaje-y-estilos-comunicativos-en-autoestima-e-identidad-personal.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Bilmes, Jack. 1994. Constituting silence: Life in the world of total meaning. Semiotica 98: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Vieira, Monica. 2020. Representing silence in Politics. American Political Science Review 114: 976–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness. Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, Thomas J. 1973. Communicative Silences: Forms and Functions. Journal of Communication 3: 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, Mary. 2014. The Feminist Foundations of Language, Gender, and Sexuality Research. In The Handbook of Language, Gender, and Sexuality, 2nd ed. Edited by Susan Ehrlich, Miriam Meyerhoff and Janet Holmes. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Fernández, Laura. 2010. Dialogues within oral narratives: Functions and forms. In Dialogue in Spanish: Studies in Functions and Contexts. Edited by Dale A. Koike and Lidia Rodríguez-Alfano. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Fernández, Laura, and Beatriz Méndez-Guerrero. 2013a. Los actos silenciosos en la conversación de los jóvenes españoles: ¿(des)cortesía o ‘anticortesía’? Estudios de Lingüística de la Universidad de Alicante 27: 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Camargo-Fernández, Laura, and Beatriz Méndez-Guerrero. 2013b. Los actos silenciosos en la conversación de las jóvenes españolas. Estudio sociolingüístico. Lingüística en la Red 11: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Fernández, Laura, and Beatriz Méndez-Guerrero. 2014a. La pragmática del silencio en la conversación en español. Propuesta taxonómica a partir de conversaciones coloquiales. Sintagma 26: 103–18. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Fernández, Laura, and Beatriz Méndez-Guerrero. 2014b. Silencio y prototipos: La construcción del significado pragmático de los actos silenciosos en la conversación española. Diálogo de la Lengua 5: 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Deborah. 2005. Language, Gender, and Sexuality: Current Issues and New Directions. Applied Linguistics 26: 482–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla del Pino, Carlos. 1992. El silencio. Madrid: Alianza Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 1999. Comunicación no verbal y enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Madrid: Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 2000. El intercambio de turnos de habla en la conversación. Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 2006. La comunicación no verbal y el estudio de su incidencia en fenómenos discursivos como la ironía. Estudios de Lingüística de la Universidad de Alicante 20: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 2007. Cooperación en la conversación: Estrategias estructurales características de las mujeres. Lingüística en la Red 5: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 2014. Comunicación no verbal y comunicación eficaz. Estudios de Lingüística de la Universidad de Alicante 28: 125–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cestero-Mancera, Ana María. 2019. Comunicación no verbal. In Guía práctica de pragmática del español. Edited by Mª Elena Placencia and Xosé Padilla. London: Routledge, pp. 206–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Jack. 2003. Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic Variation and Its Social Significance. New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, Jeniffer. 2016. Women, Men and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Company-Morales, Miguel, Lina Casadó, Eva Zafra Aparici, Mª Filomena Rubio Jiménez, and Andrés Fontalba-Navas. 2022. The Sound of Silence: Unspoken Meaning in the Discourse of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women on Environmental Risks and Food Safety in Spain. Nutrients 14: 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Fernández, Josefa. 2008. Conversational silence and face in two sociocultural contexts. Pragmatics 18: 707–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFrancisco, Victoria Leto. 1991. The sounds of silence: How men silence women in marital relations. Discourse & Society 2: 413–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 1992. Think practically and look locally: Language and gender as community-based practice. Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 461–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 2003. Language and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ephratt, Michal. 2008. The functions of silence. Journal of Pragmatics 40: 1909–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephratt, Michal. 2018. Iconic silence: A semiotic paradox or a semiotic paragon? Semiotica 18: 239–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephratt, Michal. 2022. Silence as Language. Verbal Silence as a Means of Expression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Escandell-Vidal, Mª Victoria. 2006. Introducción a la pragmática. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Pamela M. 1977. Interactional shitwork. Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts and Politics 2: 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Pamela M. 1978. Interaction: The work women do. Social Problems 25: 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Pamela M. 1980. Conversational insecurity. In Language: Social Psychological Perspectives. Edited by Howard Giles, W. Peter Robinson and Philip M. Smith. Oxford: Pergamon, pp. 127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Susan. 1989. Between speech and silence: The problematics of research on language and gender. iPrA Papers in Pragmatics 3: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Susan. 1995. Language, Gender, and Power: An Anthropological Review. In Gender Articulated: Language and the Socially Constructed Self. Edited by Kira Hall and Mary Bucholtz. New York: Routledge, pp. 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Paúls, Beatriz. 1993. Lingüística Perceptiva y Conversación: Secuencias. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mouton, Pilar. 2003. Así hablan las mujeres. Madrid: La esfera de los libros. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward T. 1959. The Silent Language. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Hal, Kira, Rodrigo Borba, and Mie Hiramoto. 2021. Language and Gender. In The International Encyclopedia of Linguistic Anthropology. Edited by James Stanlaw. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Janet. 1995. Women, Men, and Politeness. Essex: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Janet. 2006. Sharing a laugh: Pragmatic aspects of humor and gender in the workplace. Journal of Pragmatics 38: 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Janet, and Meredith Marra. 2004. Relational practice in the workplace: Women’s talk or gendered discourse? Language in Society 33: 377–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckin, Thomas. 2002. Textual silence and the discourse of homelessness. Discourse & Society 13: 347–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, Adam. 1993. The Power of Silence. Social and Pragmatic Perspectives. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, Adam. 2018. The art of silence in upmarket spaces of commerce. In Expanding the Linguistic Landscape. Linguistic Diversity, Multimodality and the Use of Space as a Semiotic Resource. Edited by Martin Pütz and Neele Mundt. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J. Vernon. 1973. Communicative functions of silence. ETC: A Review of General Semantics 30: 249–57. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Mark L. 1980. Essentials of Nonverbal Communication. Chicago: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzon, Dennis. 1997. Discourse of Silence. Amsterdam and Philadephia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzon, Dennis. 2018. Silence as Speech Action, Silence as Non-speech Action. A Study of Some Silences in Maeterlinck’s ‘Pelléas et Mélisande’. Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities 112: 122–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, Robin. 1975. Language and Woman’s Place. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Domingo, Irene. 1995. Lenguaje femenino, lenguaje masculino. ¿Condiciona nuestro sexo la forma de hablar? Madrid: Minerva. [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Serra, Rosa. 2021. Silencio, prensa y pandemia. Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 4: 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2013. El silencio en la conversación española. Reflexiones teórico-metodológicas. Estudios Interlingüísticos 1: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2014. Los actos silenciosos en la conversación en español. Estudio pragmático y sociolingüístico. Palma: Universitat de les Illes Balears. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2015a. Corpus Oral Juvenil del Español de Mallorca (COJEM). LinRed 13: 1–286. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2015b. El uso estratégico del silencio en conversaciones de mujeres: ¿reafirmación o transgresión del feminolecto? In Estudios de pragmática y traducción. Edited by Silvia Izquierdo Zaragoza. Murcia: Editum. Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia, pp. 230–50. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2016a. Funciones comunicativas del silencio: Variación social y cultural. LinRed 13: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2016b. La interpretación del silencio en la interacción. Pragmalingüística 24: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2017. Silencio, género e identidad: Actitudes de los jóvenes universitarios españoles ante los actos silenciosos en la conversación. Revista de Filología de la Universidad de la Laguna 35: 207–29. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2023. El silencio en la oralidad. In Lingüística de la ausencia. Edited by Fernando López García. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 173–95. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz. 2024. El silencio en la comunicación multimodal en español. Granada: Comares. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Guerrero, Beatriz, and Laura Camargo-Fernández. 2015. Los actos silenciosos en la conversación española: Condicionantes, realizaciones y efectos. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 64: 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, Lesley, and Matthew Gordon. 2003. Sociolinguistics. Method and Interpretation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Fernández, Francisco. 2021. Marcas y etiquetas mínimas obligatorias para materiales de PRESEEA. Available online: https://preseea.uah.es/sites/default/files/2022-02/Marcas%20y%20etiquetas%20m%C3%aDnimas%20obligatorias%20para%20materiales%20de%20PRESEEA_Moreno%20Fern%C3%A1ndez%20%282021%29.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Murray, Amy Jo, and Kevin Durrheim. 2019. Qualitative Studies of Silence. The Unsaid as Social Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, Ikuko. 2007. Silence in the Multicultural Classroom: Perceptions and Performance. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pons-Bordería, Salvador, dir. 2023. Corpus Val.Es.Co. 3.0. Available online: http://www.valesco.es (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Poyatos, Fernando. 1994. La comunicación no verbal II. Paralenguaje, kinésica e interacción. Madrid: Istmo. [Google Scholar]

- Poyatos, Fernando. 2002. Nonverbal Communication Across Disciplines, Volume II: Paralanguage, Kinesics, Silence, Personal and Environmental Interaction. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Poyatos, Fernando. 2021. El discurso oral durante la pandemia del coronavirus. Linguística en la Red 18: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Graciela. 2002. Metapragmática: Lenguaje Sobre Lenguaje, Ficciones, Figuras. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-O’Ryan, Antonia, and Silvana Guerrero. forthcoming. Funciones pragmalingüísticas del silencio en narraciones conversacionales de hablantes chilenos: Una propuesta taxonómica. Onomázein 62. in press.

- Rodríguez-Bravo, Ángel. 2021. ¿El silencio es un sonido?: Diez principios para una teoría expresiva del silencio. Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 4: 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50: 696–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintot, Valérie M., and Miikka J. Lehtonen. 2023. Trascendental and Material Silence. A Multimodal Study on Silence in Team Meetings. Journal of Management Inquiry 33: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Amy. 1993. Pickle fights: Gendered talk in preschool disputes. In Gender and Conversational Interaction. Edited by Deborah Tannen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, Melani. 2013. Silence and Concealment in Political Discourse. Discourse Approaches to Politics, Society and Culture. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, Melani, and Charlotte Taylor. 2018. Exploring Silence and Absence in Discourse: Empirical Approaches. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Harvard: Harvard University Press/Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, Deborah. 1990. You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York: Ballentine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, Deborah. 1993. The relativity of linguistic strategies: Rethinking power and solidarity in gender and dominance. In Gender and Conversational Interaction. Edited by Deborah Tannen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, Deborah. 2005. Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, Deborah, and Muriel Saville-Troike. 1985. Perspectives on Silence. Norwood: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Torras i Segura, Daniel. 2023. Reflexiones sobre la caracterización del silencio como signo. Dificultades, interrogantes y singularidades. Revista Signa 32: 637–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troemel-Ploetz, Senta. 1991. Review essay: Selling the apolitical. Discourse & Society 2: 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1986. Dialects in Contact. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wharton, Tim. 2009. Pragmatics and Non-Verbal Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Don, and Candace West. 1975. Sex roles, interruptions, and silences in conversation. In Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Edited by Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley: Newbury House, pp. 105–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).